The Paris Review's Blog, page 762

November 20, 2013

Twiggy and the Gang

My mother was not a regular reader of Vogue when I was girl in the 1960s, but my friend Diane’s mother—a cool, soignée blonde with an alluring French twist and a lily of the valley–infused cloud of Diorissimo hovering perpetually about her—was, and whenever I visited, Diane and I would pore over the magazine’s slick, bright pages together in a companionable reverie that needed no words. Veruschka’s Slavic exoticism held us deeply in thrall; the preternatural perfection of Jean Shrimpton’s full, exquisitely lipsticked mouth was like a valentine. We longed to look like them, but we knew these girls—and they were, after all, girls—would always remain at some poignant and unattainable remove from us, or anything we could ever aspire to be. With their sinuously lined eyelids, thick manes of hair, and aloof, worldly posturing, Shrimpton, Veruschka, and their ilk had already assumed the lacquered and impermeable gloss of fully grown women, and had left us far, far behind.

So you can imagine our mutual astonishment on the day in 1967 when we turned the page and found ourselves locking eyes with the vulnerable, unvarnished, and most astonishing of all: the impossibly young face of Twiggy. From the moment I saw her boyishly cropped hair, faint spray of freckles, tremulous mouth and huge, wide-open eyes, I felt a visceral shock of recognition. Although she was not one of us—neither Diane nor I were so deluded as to imagine that—we could discern that she was nonetheless only a few baby steps ahead, and onto her fey, coltish image, we could project that of an adored babysitter or someone’s cool older sister. The vestigial childishness of her narrow hips and her pipe-stem legs only confirmed our immediate sense identification. Twiggy was the first model appearing in a women’s magazine who was not precisely a woman; instead, she embraced and exalted her at moments awkward—yet always adorable—girlishness. And since it was clear that Twiggy loved being a girl, not a woman, she gave us the heady permission to love what was still girlish in ourselves.

Quickly, Diane and I spread the word, and the fifth and sixth graders who comprised our little pack were eager to climb on board. We formed our own Twiggy fan club, and at the weekly meetings quizzed each other on tidbits gleaned from teen magazines. Real name? Leslie Hornby. Birthday: September 19, 1949. Soon we could recite the complete catechism: she attended Kilburn High School for Girls and began modeling at fifteen. Her nickname—first Sticks, then Twigs—soon morphed into Twiggy; that was the one that stuck.

Those magazines yielded pictures too, and we jostled each other for the chance to see images of her riding her bicycle, sipping hot chocolate with her boyfriend-turned-manager Justin de Villeneuve or romping with a litter of puppies; clearly those dogs were as besotted as we were. Pages were roughly torn out, taped to our walls, doors, and book covers; we wanted to be Twiggy, each of us vying furiously for the right to inhabit the Cockney cutie’s persona for the duration of our “let’s pretend” games.

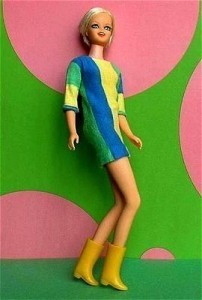

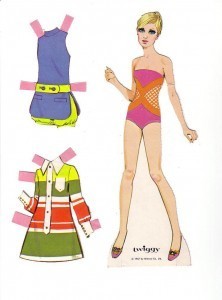

When the meetings were over and we went back home, we pestered our mothers for the Twiggy lunch boxes, tights, sweaters, tote bags, and paper dolls flooding the market. Diane’s mother, more indulgent than mine, was willing to purchase the Milton Bradley Twiggy board game, the Twiggy Barbie made by Mattel, a Twiggy lunch box, binder, pen, and tote. I had to settle for the paper dolls.

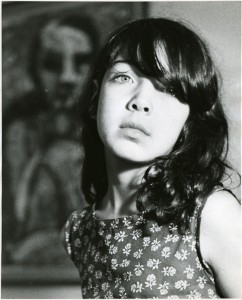

The author, desperately growing out bangs to achieve the coveted Twiggy crop.

Then there was the memorable occasion when we all saved our money and descended, en masse, upon a local beauty parlor (the word salon had not yet come into common parlance) begging for Twiggy crops. One by one, we stepped up to the chair, submitted to the long, floral-print smock and the flashing scissor blades. Diane’s smooth blonde hair—very much like her mother’s—was the perfect raw material for the coif; once shorn, her face, newly revealed, displayed an angular grace none of us had noticed before. Nancy and Betty fared a little less well; Nancy’s hair was too thick, resulting in a style that looked puffy rather than sleek, and though raven-haired Betty looked cute—she always looked cute—she was nothing like Twiggy. Still, I would have traded their experience, gladly, for mine.

During the interminable wait for my turn, I fairly pulsated with excitement. How would the cut look on me? Would I be transformed? What secrets of my soul would it reveal? Would the haircut bring me one step closer to feeling like Twiggy might have felt? I never had the chance to find out. The beautician (re: stylist, see note above) told me that my shortly cropped, uneven bangs would need to grow several more inches before they could be coaxed into anything like an approximation of my idol’s. I stepped down from the chair, crushed. By the time my bangs did grow long enough, the cut seemed like an afterthought and I never ended up getting one. And although our collective Twiggy love continued through the 1960s, she was eventually replaced in our affections by the new crop of American beauties—Cheryl Tiegs, Cybil Shepherd, Christy Brinkley—that bloomed in her wake.

In the decades to come, Twiggy went on to become a singer, an actress (both stage and screen), a television personality, and, most recently, a judge on America’s Next Top Model. She’s been highly successful in these various pursuits, but for those of us who remember her back in the day, her most resonant incarnation, both culturally and psychologically, occurred somewhere in that midsixties, Carnaby-incubated madness. I began to ponder why this was so; what made her different from the girls who had come before her, and what made her image, even all these years later, such a powerful symbol—maybe even talisman—of that era?

Unlike her predecessors, who were largely silent in the public realm, Twiggy talked. She also giggled, guffawed, and was occasionally—and charmingly—tongue-tied. The gamine girl from Twickenham, Middlesex—a town about twelve miles southwest of London—was possessed of a lower-class accent that both spoke of the times and directly to them. And, to quote Bob Dylan, another sixties icon, the times they were a-changin’. Cheeky, underclass interlopers like Twiggy were upending the old, deeply entrenched supremacies of class and money. She could easily have been the girl Beatle: she had both the background and the street cred. And like a true Beatle, she made no attempt to hide her own unvarnished roots; quite to the contrary, she, like the lads from Liverpool, made a virtue of them. During the years my friends and I had swooned for Twiggy, we swooned for the Beatles too: Paul’s cherubic cheeks and sweet voice, John’s surprising, low-key irony, George’s soulful silences, and Ringo’s sad-clown charm. I didn’t realize the connection back then, but now the link seems so apparent. Twiggy, like the Beatles, was part of the new order in which the past, and all it represented, was going to be less important than the future.

Unlike her predecessors, who were largely silent in the public realm, Twiggy talked. She also giggled, guffawed, and was occasionally—and charmingly—tongue-tied. The gamine girl from Twickenham, Middlesex—a town about twelve miles southwest of London—was possessed of a lower-class accent that both spoke of the times and directly to them. And, to quote Bob Dylan, another sixties icon, the times they were a-changin’. Cheeky, underclass interlopers like Twiggy were upending the old, deeply entrenched supremacies of class and money. She could easily have been the girl Beatle: she had both the background and the street cred. And like a true Beatle, she made no attempt to hide her own unvarnished roots; quite to the contrary, she, like the lads from Liverpool, made a virtue of them. During the years my friends and I had swooned for Twiggy, we swooned for the Beatles too: Paul’s cherubic cheeks and sweet voice, John’s surprising, low-key irony, George’s soulful silences, and Ringo’s sad-clown charm. I didn’t realize the connection back then, but now the link seems so apparent. Twiggy, like the Beatles, was part of the new order in which the past, and all it represented, was going to be less important than the future.

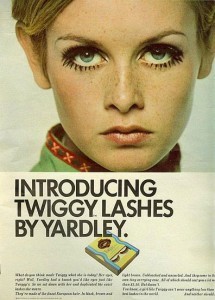

Twiggy was also considered the world’s first supermodel, and it seems telling, in retrospect, that it was her very rawness that allowed her to assume the role. For she had a certain self-consciousness that was both unique and touching; until she came along, models were not generally thought to have selves about which to feel conscious. And they were supposed to hide any self-consciousness—now in the sense of discomfort or awkwardness—under the veneer of their sophistication and grace. Twiggy blew these precepts to smithereens. Her unpolished—and at moments downright gawky—demeanor both heralded the youth culture that was storming the barricades, and announced, loudly, that the spoils belonged not so much to the strongest but to the youngest. She was the proverbial breath of fresh air, the clean sweep, the very face of change in a pair of two-inch false, feathered, eyelashes.

Image via Fanpop.

When visiting The Model as Muse, the much-touted show mounted some years ago at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, I saw—for the first time in decades—the face I remembered staring out at me from the pages of decades-old magazines. There she was with the flower painted round one eye; here she was with the spiky, drawn-on lower lashes that gave her a doll-like mien. There is something both deeply shocking and supremely comforting about looking at photographs remembered, vividly, from the past. The intervening years become nothing but a mist, a skein of smoke, easily dispersed as you confront not only the photos, but the person you were when you first saw them. Then I came upon an image from Harper’s Bazaar I did not remember seeing: Twiggy standing in front of the window of FAO Schwarz, when the store was on Fifty-Eighth Street and Fifth Avenue; across the avenue, the north corner of Bergdorf Goodman’s can be glimpsed, along with the somewhat obscured entrance and awning to the old Plaza Hotel.

In the photo, Twiggy wears a short, citron-green suit with a pointed collar and patch pockets. On her head is a matching beret; on her famous, often–knock-kneed legs, a pair of patterned tights. In one arm, she holds a large stuffed owl brandishing a Steiff tag; Steiff was known for producing the ne plus ultra of stuffed animals, and the owl, which looks to be a good twenty-four inches high, is a splendid example of their stunning craft. Was there some witty juxtaposition being drawn? A visual contrast between innocence and experience? Youth and wisdom?

Most remarkable of all is the group of people flanking Twiggy. Like the model, they are all on the outside, peering into an unseen window display, and each and every one in the crowd wears a flat, two-dimensional paper mask. While I did not see the photo back in 1967 when it was taken, I suddenly recalled the masks, which my friends and I all wore, one Halloween, along with our striped, turtle-neck minidresses (mine was a giddy medley of hot pink, turquoise, yellow, and black) and our white, Courrèges-inspired go-go boots. Talk about a madeleine moment.

We walked the streets of our Brooklyn neighborhood, masks firmly in place, ardent in our collective hope that they would … what? Protect us from harm? Launch us into a bright, hope-filled future? Sprinkle some of Twiggy’s magic girlpower upon our untried young shoulders? Even all these years later, I still cannot say for sure. But it is worth mentioning that not long ago, I told my stylist to crop me closely, like a lamb in spring, and I’ve been sporting the super-short coif proudly ever since. Without my being fully aware of it, Twiggy was right there, in whispering in my ear.

Yona Zeldis McDonough’s fifth and most recent novel, Two of a Kind, was just released from New American Library.

In the Darkroom with W. Eugene Smith

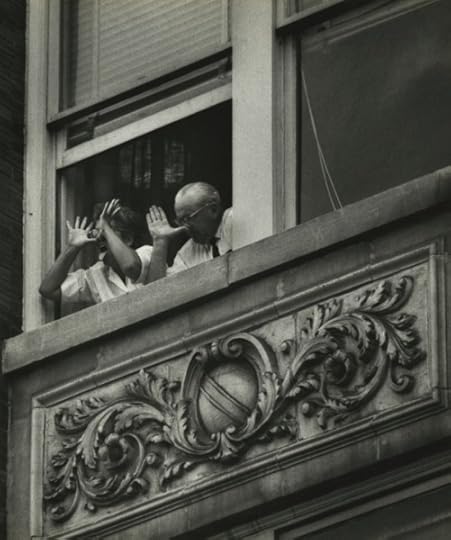

James Karales, Lower East Side, New York, 1969, black-and-white photograph, 13 1/2 X 16 5/8 inches.

In early March of 1955, W. Eugene Smith steered his overstuffed station wagon into the steel city of Pittsburgh. He’d been on the road all day, leaving that morning from Croton-on-Hudson, New York, where he lived in a large, comfortable house with his wife and four children, plus a live-in housekeeper and her daughter. He was thirty-six, and a fuse was burning inside him. He had recently quit Life, after a successful but troubled twelve years, and joined Magnum, and this was his first freelance assignment. He had been hired by renowned filmmaker and editor Stefan Lorant to shoot a hundred scripted photographs for a book commemorating Pittsburgh’s bicentennial, a job Lorant expected to take three weeks. On Smith’s horizon, however, was one of the most ambitious projects in the history of photography: he wanted to create a photo story to end all photo stories. His station wagon was packed with some twenty pieces of luggage, a phonograph, and hundreds of books and vinyl records—he was prepared for an eruption.

A hundred and eighty miles southwest of Pittsburgh, in Athens, Ohio, James Karales was finishing up a degree in photography at Ohio University. He had studied Smith’s work in class; Smith was a hero. While Smith was crawling all over Pittsburgh, day and night, several cameras wrapped around his neck, fueled by amphetamines, alcohol, and quixotic fevers, Karales was getting his diploma. Little did Karales know, his path and Smith’s were about to become one, and he would get an education no college could provide.

Smith returned to Croton in late August with about eleven thousand negatives. Lorant was livid. Where were the hundred scripted photos he had hired Smith to make? Lorant pressured Magnum’s executive editor, John Morris, but Smith wouldn’t release anything. He was paranoid Lorant would try to take ownership of his intended masterwork. (Smith eventually sought and received a copyright from the Library of Congress to protect himself.)

Meanwhile, Karales, fresh out of school, had moved to New York to seek work as a professional photographer. He knocked on Magnum’s door and asked Morris whether there was any work for a young photographer. “Do you want to be Gene Smith’s darkroom assistant?” Morris replied.

Karales took a train to Croton that same day. He moved into one of the Smith family’s guest bedrooms. There were now four adults and five children living under one roof, and one of the adults was a man possessed. It was like asking a new film-school graduate to help Francis Ford Coppola complete Apocalypse Now, a project that almost killed the director and alienated everybody around him.

Forty years later I visited Karales, who was still living in Croton with his wife, Monica. (He died in 2002.) In the interim years he had become a world-class photojournalist in his own right, a staff photographer for Look magazine, producing some of the most iconic photographs of the civil-rights era and the Vietnam War as well as powerful portraits of a small town in Ohio, Rendville, and of the Lower East Side, among others. Karales drove me around town and showed me the Smith house on Old Post Road, musing on the experience while my tape recorder ran.

“Gene thought I was an idiot when I first met him,” said Karales, chuckling. “I told him I’d just graduated from Ohio University. He thought I hadn’t gone through the sixth grade! But I was pretty naïve. I came from an immigrant family, and I didn’t read much. And here I am, up there with this bloody genius. It just opened my life up completely. The reason he was nice to me is he needed me. Thank God that relationship existed, because otherwise, shit, I’d have been living down on the street someplace.”

Smith went back to Pittsburgh and exposed another ten thousand negatives, bringing the total to twenty-one thousand. Karales stayed in Croton and made prints. Smith considered two thousand negatives to be valid for his opus, an impossible number given his idiosyncratic printing technique. Certain prints required a few days to make, said Karales. The pair made dozens of 5 x 7 work prints for each negative, testing and experimenting until Smith was satisfied. Then they would make an 11 x 14 master print. This process lasted three years.

“We went through a lot of [emulsion] paper,” Karales remembered, “because Gene didn’t do what you’d call a script. A script didn’t mean anything to him, not when he was shooting or when he was printing. He wanted to see the whole thing, and see what areas needed to be worked on as he was going along. We went through boxes of paper, believe me. We bought two hundred and fifty sheets at a time. Before this, I never knew what you could do in a darkroom. At least fifty percent of the image is done in the darkroom—I think Gene would say ninety percent. The negative has the image, but it can’t produce the image completely, as the photographer saw it—not as Gene saw it. You have to work it over and over with the enlarger, you have to burn it in, you have to hold back areas—this detail down here or over there.”

Karales continued, getting more specific about the technique: “Gene always liked to get separations around people, figures, and that was always done with potassium ferrocyanide. It was the contrast that made the prints difficult. Gene saw the contrast with his eyes, but the negative wouldn’t capture it the same way. So he would have to bring the lamp down and burn, and then if that spilled too much exposure and made it too dark, you would lighten it with the ferrocyanide. You had to be careful not to get the ferrocyanide too strong, and yet you couldn’t have it too weak, either. If it took too long, it would spread. So I would blow the fixer off of the paper so ferrocyanide would stay in an area, and then dunk the paper right away to kill the action. Or if you wanted something to go smoother, then you left the fixer there. It was extremely delicate and complicated, but we got it down pat.”

Smith received two successive Guggenheim fellowships to help pay for the work, but he had given up a much larger salary and expense account at Life. The family was destitute; tensions in the house grew. Smith and Karales worked while the family slept. “We’d usually get up around two, three o’clock in the afternoon,” said Karales, “have lunch, and start printing. Then the family would go to bed, and when they got up, we went to bed.”

Once enough prints were made, Smith began arranging them in layouts all over the house. “He first started in the dining area, and when he ran out of room, we had to go into the living room area. He bought eight-foot-by-five-foot panels—bulletin boards that stood on legs, so you got both sides. And then all these 7 x 7s would be pinned up there, and he would look at them and study them and make sure which ones he wanted in his essay. And then we would make the prints, the final 11 x 14 prints.

“Gene believed you can have a picture that’s really powerful, but if it doesn’t fit within the layout, in the storytelling situation, then you don’t use that picture. One time, after I got the job at Look, he laid one of my stories out for me, the Selma March stuff, before I showed it to the magazine. In Look, the art director used my iconic Selma picture first. Gene used it in the middle somewhere, which would have made more sense. It was amazing what he did with the pictures, with their sequential situation. Gene got me that job at Look, by the way. I think that was my payment for helping him. He never paid me in money.”

Smith finally answered his obligation to Lorant, but his Pittsburgh magnum opus fizzled in an erratic layout he published in Popular Photography’s Photography Annual in late 1958. In a letter to Ansel Adams, he called it a “debacle” and a “failure.”

“Desperate,” as Karales described him, Smith retreated to a Manhattan flower-district loft. Karales lived for another two years in the Smith house before finding his own place in Croton.

A significant legacy of Smith’s Pittsburgh project was the apprenticeship of the young Karales. He came from the last generation of photographers whose childhood and youth were not informed by the takeover of television, when printed pictures served as culture’s primary visual imagery. A modest, unassuming man until his passing, Karales never climbed the ladder of fame, didn’t seem to care about it. He just did his job. His ethic and personality seemed more like that of a carpenter or refrigerator repairman than a gallery-hopping artist, making him perfect for the job with Smith—just put your head down and make prints, pal, and make them like this. For the rest of his career, Karales displayed a profound, velvety darkroom printing technique reminiscent of Smith’s. Karales, though, wasn’t trying to change the world. Maybe Smith could have learned a little something from him.

James Karales, Untitled (child by table and chair), date unknown, black-and-white photograph, 9 1/8 X 13 5/8 inches.

James Karales, Logging, Oregon, 1959, black-and-white photograph, 13 5/8 X 7 3/4 inches.

James Karales, Vietnam, 1963, black-and-white photograph, 10 3/4 X 13 1/8 inches.

James Karales, Lower East Side, New York, 1969, black-and-white photograph, 12 1/2 X 19 3/4 inches.

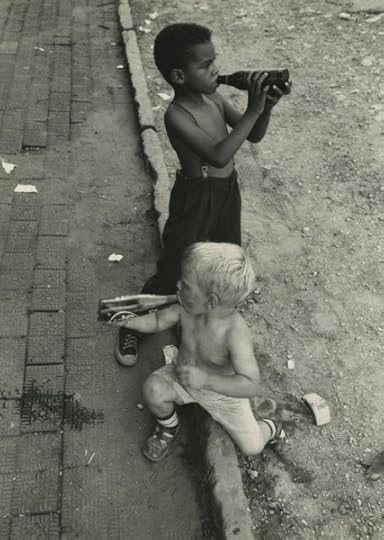

James Karales, Rendville, Ohio, 1953–55, black-and-white photograph, 8 7/8 X 13 1/4 inches.

James Karales, Vietnam, 1963, black-and-white photograph, 7 1/8 X 13 5/8 inches.

James Karales, Vietnam, 1963, black-and-white photograph, 9 7/8 X 13 1/2 inches.

James Karales, Rendville, Ohio, 1953–55, black-and-white photograph, 7 7/8 X 13 1/2 inches.

James Karales, Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, 1965, black-and-white photograph, 12 3/4 X 10 3/4 inches.

James Karales, Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, 1965, black-and-white photograph, 13 1/8 X 19 3/8 inches.

James Karales, Rendville, Ohio, 1953–55, black-and-white photograph, 9 5/8 X 7 inches.

Sam Stephenson is at work on a biography of W. Eugene Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux. His 2009 book, The Jazz Loft Project , won an ASCAP Deems Taylor award.

Karales’s work is on view at Howard Greenberg Gallery, in New York, through December 14. Steidl will publish a career-spanning monograph later this year.

All photographs copyright Estate of James Karales, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

Fourth Wall

“When my head is in the typewriter the last thing on my mind is some imaginary reader. I don’t have an audience; I have a set of standards. But when I think of my work out in the world, written and published, I like to imagine it’s being read by some stranger somewhere who doesn’t have anyone around him to talk to about books and writing—maybe a would-be writer, maybe a little lonely, who depends on a certain kind of writing to make him feel more comfortable in the world.” —Don DeLillo, the Art of Fiction No. 135

RIP Charlotte Zolotow, and Other News

Charlotte Zolotow has died, at ninety-eight.

So, what would Aldous Huxley do?

C. S. Lewis has been inducted into the famed Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey.

Sales of hardcover books are surprisingly brisk.

November 19, 2013

Actual Size

The miniature book The Infant’s Library. Part of the British Library’s current exhibition “Georgians Revealed: Life, Style and the Making of Modern Britain.”

It Was Too Strong: An Interview with Todd Hido

She had a black mohawk, edged in green. Sometimes red. I believe there was a brief blue phase. She wore Doc Martens long before they were cool, and she only ever wore baggy, black clothing. I never once saw her smile. When she hung out with the other punks in the unofficial outdoor smoking section of our neighborhood, she inhaled her cigarettes slowly, gently. She wasn’t pretty or even conventionally attractive, but boys always surrounded her. Perhaps it was the heavy eyeliner, speaking of a life populated with interesting and equally enigmatic people and filled with rarefied events that neither I nor her admirers would ever experience, couldn’t even fathom. Part of her mystique, of course, was that she didn’t seem to engage with her entourage, but, eyes down, quietly murmur something once in a while that would galvanize everyone.

She lived just ten houses down from me, but in an older, separate subdivision. On my nightly walks with Maggie, our Rastafarian family dog, I’d hope for a glimpse inside her rundown house. Though lights often flickered through the drawn curtains, that entire winter I never saw a thing. Her home was as inscrutable as was she. Invariably Maggie would pull at the leash to go back home where it was warm and she could go to sleep and where my life, boring and uneventful, waited.

Many years later, I came across this photograph on Todd Hido’s Web site.

For a brief moment, I thought it was her house. Then I saw the dissimilarities; it wasn’t. But the effect on me was profound: my emotional response to the photo, the swoosh of nostalgia, became a portal. Suddenly I was once again in the midst of painful adolescence, projecting a narrative onto a girl I had never met.

It’s no coincidence that Vintage Books recognized the power of Hido’s work and put photos of his homes on the covers of Raymond Carver’s anniversary editions. The pairing is perfect. For inside Carver’s homes, life is hard, often complicated by alcoholism and disintegrating relationships. The same could be happening inside Hido’s homes.

In Hido’s newest work, Excerpts from Silver Meadows, that is exactly the effect he intends. Photos are carefully structured into loose chapters, small narratives that lead the viewer back in time to our youth, one in which traditional notions of adolescence are turned upside down. “This book is a dark book,” Hido admits. “It’s not exactly uplifting. And it gets darker as it goes on.” Hido’s previous works focused on one subject: houses at night, landscapes, portraiture. Excerpts weaves all of these subjects together to create a far more complex narrative. What that story is, exactly, is entirely up to the viewer.

It’s the middle of the night; we are at a very modern, very chic apartment in Chelsea. Hido’s flight into New York was delayed, and my interview with him over wine, takeout, and cigarettes on the glass balcony is like hanging out with an old friend (partially true; I once modeled for him). Hido is friendly, amiable, and possesses a rare charisma that immediately puts one at ease. It’s strange to connect the darkness of the book with the artist. But, as Hido tellingly admits, “I believe you can use photographs to meditate on and work through things in your life.” Thus, it is the main foldout autobiographical section of the book in which much can be deduced, but nothing is certain.

As we looked through his autobiographical section, Hido abstained from giving any specific facts about his childhood, saying instead, “Picasso said, ‘Art is a lie that tells the truth.’ Yes, it is fictitious, but only to a certain point.” The facts of his upbringing remain hazy, and the images are vague enough that they might mean different things, but it feels like a childhood of possible alcoholism, neglect, and violence. Images include a wall punctuated by fist-size holes; a boy’s bike deserted at the edge of a creek; a phone off the hook in a filthy, empty room; a lonely stuffed animal in the corner of a barren room.

There are also two small images of a blond woman (presumably his mother). In the first she appears beautifully innocent, but the focus is blurry—implying that this innocence is an apparition, a faint trace from of past. What happened? A found photo of a book depicts a salacious blonde under the banner: “She was the campus tramp. All a boy had to do was … Say When.”

On the same page is a news clipping of his father, proud and happy, a football hero, the heading Action is What Hido Gives the Fans next to a photograph of the same man: older, balding, disheveled, and slumped over, barely managing to hold up his diploma with one hand and grab his son’s arm in the other. Another image is similarly composed: with one hand, he proudly lifts up his son; with the other, a keg of beer. He stands with his chest pumped out, ignorant of the stains on his clothing and that his son seems to be both pushing the keg away and attempting to release himself from his father. Empties scatter the foreground.

In the second and last photo of the blonde, she’s smiling, but her eyes are cut out of the frame; perhaps it’s a passive-aggressive assault on his mother for refusing to see what was happening around her. Worse, for smiling her way through it all.

The smaller stories that both encircle and inform this personal and seemingly violent narrative tie everything together. They imply a man searching for other stories like his own, wanting to suggest the truth of his childhood, or to sublimate it.

There are exterior shots of houses, taken mostly in the Midwest (often in and around his hometown of Silver Meadows, for which the book is named) and usually from his car; devoid of life, they feel haunted. Lights might shine brilliantly through windows, doors gape open, and cars sit in driveways; there are no inhabitants in sight. The homes feel abandoned, forsaken. Interior images depict what seem to be dark and subversive acts; the where and when of these activities are entirely subjective. Portraits and landscapes often have their own page.

Who are these people? What have they done? What are they about to do? Why is this image of an object even here? These phantoms of our collective past suggest significantly dark events about real people doing, having done, or about to do questionable actions both disarm and reinterpret our ideas of childhood and innocence. An idea that is far more disturbing than that of literal ghosts or ghouls haunting a home.

There are also some stunningly beautiful photos in the book; landscapes that have a painterly, almost William Turner feel to them. As Hido says, “I’m not afraid to use beauty to draw people in.”

A beautiful, self-possessed woman lures the viewer into her world: shot from behind, her graceful neck, pearl necklace, and an alluring, off-the-shoulder dress connote a poised and confident woman. But it’s the subtle details of the portrait that punctuate the series of images that follow: as she holds her right hand up near her ear, she’s also turned her head away to the left, as if to say, stop. Turn the page and there she is: in a car, drunk; pretending to take off her clothes; making sexy poses for the camera; bent over a bed, naked but for shoes and panties.

In a different chapter, the very first photo is of a decrepit home. Apparently abandoned, save for the fact that snow has been removed from the roof, but not the gutters, leading the viewer to surmise that the owner did the bare minimum to prevent yet more damage to the house. It’s not a home anyone particularly cares about. Then there’s a very small, close-up image of a baby in a bed. Is it asleep? Dead? No other person is in the photo. Perhaps whoever lives there is as neglectful of the baby as s/he is of the house. The third and last image in the chapter is of a trailer home. Taken from a distance through a wet window, sections of the image are murky, like a memory, while others are crystal clear. The viewer is forced to wonder why two different homes border the image of the baby. Was the trailer home where the occupant ran to after a horrifying incident with the baby? Is the recollection indistinct because the events leading to this new, even more decrepit-looking home are too painful to remember? The answer is purposefully ambiguous, as Hido readily admits, “I’ve always implied the lives of other people … Robert Adams said to Dorothea Lange that ‘A photographer’s job is to photograph what exists and prevails.’ There’s an impulse to have a document. But I’ve never been able to call myself a documentarian because I play with fiction … It might not have happened to that person in this house, but it does happen. So it does exist and prevail.”

Each chapter’s narrative ambiguity is integral to the montage, as are the individual photos Hido choses and the order in which he displays them. “In the background I’m always stringing images together to imply a narrative,” explains Hido. Of a photo of a young girl half naked on a seedy bed, frightened and scared, but looking directly at the camera, he says he kept the photo in his “closet” for years. “I didn’t like what it said. It was too strong. I wasn’t ready for this before. [Sometimes] you have to grow into something you’ve made.” Because who’s to say what is really happening? Is this girl about to be raped? Was she just assaulted? Or could the story be something very different, the reality of which, given just that one photo on the page, the viewer will never know.

The last three photos of the book (a street sign, a woman looking scared to death, a phone) imply that “Something has happened—you don’t know what. She saw something, but you don’t know what.” The final image, a close-up from the autobiographical section: the phone off the hook. What has happened that was so sudden that a phone, on the ground in a dirty and apparently abandoned room, would be left off the hook?

Much in the way I idolized a girl who seemed so sure of herself, Hido’s Excerpts allows for a similar emotional, visual, and visceral context of my youth. Looking at her house and wondering: Who they were, what they did, did they love each other? Fight? Play? Eat together? How did their daily lives play out within those four walls? What did that mean? Hido delves into the past in a way I can’t; it’s all memory, but none of it is documented and none of it seems real anymore. But it did happen.

A viewer of Excerpts has much the same experience with Hido’s photos as I had as a youth with this girl’s house. Except that the voyeuristic and participatory component is there for the world to see—it’s not a private memory. More questions are raised than are answered, and it is up to the viewer to answer them with a combination of fact (the photo itself) and of personal experience. Hido understands this ambiguity. Everyday it tugs at us, shapes us. An e-mail or text misunderstood, an unheard request; we interpret and judge with facts and information, but also with our memory and experience of past events, which are not always reliable, and with the omnipresent and sometimes overriding interference of our imagination.

Emily Farache is a writer living in New York.

Happy Birthday, Sharon Olds

“There’s no method. There’s no formula. If you really proceed a sentence at a time, if you pay attention to the sentence you just wrote and look to it for the clue for what to do to the next sentence, you can inch your way along to what may be a story. This wouldn’t have occurred to me starting out, for example, when I thought you wrote one sentence, then just looked out to the world trying to snag the next one. That’s not how it works. You look back at what you gave yourself to work with. Sharon Olds said something beautiful about sometimes thinking of her poems as instructions for how to put the world back together if it were destroyed.” —Amy Hempel, the Art of Fiction No. 176

C. S. Lewis Reviews The Hobbit, 1937

A world for children: J. R. R. Tolkien,

The Hobbit: or There and Back Again

(London: Allen and Unwin, 1937)

The publishers claim that The Hobbit, though very unlike Alice, resembles it in being the work of a professor at play. A more important truth is that both belong to a very small class of books which have nothing in common save that each admits us to a world of its own—a world that seems to have been going on long before we stumbled into it but which, once found by the right reader, becomes indispensable to him. Its place is with Alice, Flatland, Phantastes, The Wind in the Willows. [1]

To define the world of The Hobbit is, of course, impossible, because it is new. You cannot anticipate it before you go there, as you cannot forget it once you have gone. The author’s admirable illustrations and maps of Mirkwood and Goblingate and Esgaroth give one an inkling—and so do the names of the dwarf and dragon that catch our eyes as we first ruffle the pages. But there are dwarfs and dwarfs, and no common recipe for children’s stories will give you creatures so rooted in their own soil and history as those of Professor Tolkien—who obviously knows much more about them than he needs for this tale. Still less will the common recipe prepare us for the curious shift from the matter-of-fact beginnings of his story (“hobbits are small people, smaller than dwarfs—and they have no beards—but very much larger than Lilliputians”) [2] to the saga-like tone of the later chapters (“It is in my mind to ask what share of their inheritance you would have paid to our kindred had you found the hoard unguarded and us slain”). [3] You must read for yourself to find out how inevitable the change is and how it keeps pace with the hero’s journey. Though all is marvellous, nothing is arbitrary: all the inhabitants of Wilderland seem to have the same unquestionable right to their existence as those of our own world, though the fortunate child who meets them will have no notion—and his unlearned elders not much more—of the deep sources in our blood and tradition from which they spring.

For it must be understood that this is a children’s book only in the sense that the first of many readings can be undertaken in the nursery. Alice is read gravely by children and with laughter by grown ups; The Hobbit, on the other hand, will be funnier to its youngest readers, and only years later, at a tenth or a twentieth reading, will they begin to realise what deft scholarship and profound reflection have gone to make everything in it so ripe, so friendly, and in its own way so true. Prediction is dangerous: but The Hobbit may well prove a classic.

Review published in the Times Literary Supplement (2 October 1937), 714.

1. Flatland (1884) is by Edwin A. Abbott, Phantastes by George MacDonald (1858).

2. The Hobbit: or There and Back Again (1937), chapter 1.

3. Ibid., chapter 15.

Image and Imagination: Essays and Reviews, by C. S. Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper. Copyright © 2013 C. S. Lewis Pte Ltd. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

Well, This Is Depressing, and Other News

The Oxford Word of the Year is … selfie .

Here is a series of cowboy poets, looking very authentically cowboy-ish indeed.

Well, swell. Right-wing extremists destroyed a statue of the poet Radnóti Miklós, who died during the Holocaust, and are burning his books.

“Wonderful Doris Lessing has died. You never expect such rock-solid features of the literary landscape to simply vanish. It’s a shock.” Margaret Atwood salutes the late laureate.

November 18, 2013

Incest Taboo

Presented without comment: the trailer for the (appropriately lurid) Lifetime adaptation of Flowers in the Attic.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers