The Paris Review's Blog, page 757

December 6, 2013

My First Book(s)

There’s nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and open a vein. —Red Smith

I

I wrote my first first book over the course of three months, from July 23 to October 23, 1979. Four weeks in, I turned eighteen. This was a novel, and not the first I’d attempted; in fifth grade, I had written forty pages of a saga called Gangwar in Chicago, inspired by The Godfather and taking place in a city where I’d never been. Setting the story in Chicago meant scouring the map in World Book for locations: Canal Street, I recall, was one. I chose it because I knew Canal Street in New York, and it seemed the sort of landscape in which a gang war could take place. To this day, I have never seen Chicago’s Canal Street, despite the twenty years I spent visiting my wife’s family in a suburb on the North Shore.

The other novel, the one I finished, was motivated almost entirely by a specific case of envy—of my friend Fred, who had spent the same summer working on a novel of his own. Fred and I were high school writing buddies, confiding to each other, as we wandered the grounds of our New England boarding school, that we both wanted to win the Nobel Prize. Now, he’d written a campus novel, tracing his difficulties as a one-year senior, parsing the school’s social hierarchy in a way that seemed enlightening and true. Fred was more serious, more focused; he not only knew what symbolism was but also how to use it. It made sense that he would write a novel, and that it would be good. A year later, he would write another one, and then we lost track of each other, until six or seven years later, when his short stories started to appear in magazines.

For me, Fred’s novel represented something of a provocation—not on his part, but on mine. I was jealous of his talent, of his motivation; I was jealous that he had the discipline to write. I’d wanted to be a writer since the age of seven, but my body of work, such as it was, consisted largely of misfires: stories, plays, novel fragments, essays, almost all of them undone. My problem was follow-through; I’d begin with great excitement, only to grow bored. Even when I finished something, I couldn’t say how I had done it, and my writing was full of political and social pieties, soapbox sentiments that, even to me, rang false. I liked (and why not?) the idea of being a writer better than I liked writing, which to this day remains an unsteady process, a balancing act between expectation and an almost willful lack of expectation, between my aspiration and my failure, between what I want and what I cannot do. I’m familiar with this now, this ongoing frustration, but then, it used to drive me crazy, the imperfection that sets in with the first written word.

I began my first first book the same way I’d begun nearly every piece of writing I had, until then, yet attempted: longhand, in a spiral notebook. Inside the front cover, I inscribed, as epigraph, a lyric from Lynyrd Skynyrd: “I’ve seen a lot of people who thought they were cool / But then again, Lord, I’ve seen a lot of fools.” Skynyrd wasn’t my favorite band, but the lines felt redolent, reflective of an idea, a message I wanted to express. This was a trick, of course, a way to push myself; then, as now, I was a sucker for a good quote, keeping notebooks full of them, taken from books and movies and records and other corners of the culture, as if together these artifacts might add up to a collage of who I wished to be. I wrote an opening scene, about returning to school for my senior year, after eight weeks at Harvard Summer School, sitting in a dorm on the Yard, smoking dope from the moment I woke up in the morning until the moment my eyes drooped closed at night. That would be the story of my senior year also, or at least part of the story of my senior year, albeit the part I was least equipped to tell. I was enamored, then, of drug literature—The Doors of Perception, The Teachings of Don Juan, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test—seeing such books as reports from the front lines of consciousness, a territory I meant to inhabit, as well. I wanted to do something similar with my own book, to articulate my self-indulgence, my (say it) self-destruction, as self-exploration, although it’s difficult, I would learn, to frame getting stoned as a reason to be. This is the first lesson: don’t write to serve an agenda, but rather to serve a story, the novel as instrument of narrative, steeped in character, conflict, interiority. I worked sporadically for a month or so, presenting myself as epic antihero; like Jack Kerouac, I aspired to make myth of autobiography. Yet unlike Kerouac, who wrote The Subterraneans in three days and Big Sur in ten, I wasn’t producing—just bits and pieces here and there. By late August, I had composed maybe fifteen pages, barely a beginning. Fred’s novel loomed in the imagination. I needed a different strategy.

I don’t remember where I got the idea to use a tape recorder, only that once I did, it felt as though I’d found a key. Starting in September, I embarked on a new routine, staying up all night, fortifying myself with bong hits, talking, talking, talking in a series of eight hour jags, midnight to eight A.M., evening after evening until the story had been told. I was in the first few months of a year off—a decision reached, at first, by choice, then rendered necessary by the crash-and-burn of my senior year, a crash-and-burn I meant to evoke in the novel, even as I sought to recover from it (reapplying to college, trying to build a new relationship with my parents) in my life outside the book. I lived, that fall, in my childhood room, redecorated as disaffected teenage lair: stereo, shelves full of paperbacks, batik tapestries hanging from the ceiling, low light in the corners, closed and cloistered, a safe space in which to incubate a world. Thinking about it, I see a link between the book I was dictating (how I got here) and the narrative I was trying to create for college (how I will move on from here), two sides of a legend about reinvention, in which my mistakes could only make me stronger, inoculating me against myself. And yet, I understand now, both were fantasies, bits of bravado, stories I wanted to believe so badly I convinced myself that they were true.

Such was the case also with my first first book, which was never a novel in any real sense of the word. Once I stopped talking, my father paid to have my tapes transcribed, and I was left with 434 typed pages of testimony loosely dressed as fiction, devoid, for the most part, of punctuation, paragraphs, proper spellings—any of the hallmarks of polished prose. My intent had been to circumvent my laziness, or fear, or lack of commitment—my inability to see a project through from start to finish—by short-shrifting the process, by dictating a draft so I could jump straight into revision, where, I liked to tell myself (correctly, as it turned out), the real writing would be done. But what did I know of real writing? Only that it was too hard. As for the manuscript, I sat down with it a time or two, but it was impenetrable. Blocks of text, phonetic misspellings, not to mention all those endless sentences, digressions, and other conversational misdirections. The trouble with dictation, I had no choice but to acknowledge, was that talking wasn’t writing, that the former was discursive while the latter was—had to be—more controlled. The key to writing, in other words, was writing, which was the second lesson, and it was a one that I’d remember when I began my second first book.

II

I wrote my second first book over the course of twenty months, from June 18, 1982 to February 26, 1984. This was a novel also, the first I’d attempted since my experiment with spoken prose. I wrote in longhand in a succession of spiral notebooks, inspired by an epigraph from Goethe: “Know thyself? If I knew myself, I’d run away.” Later, during revisions, I appended a second epigraph, borrowed from the Sex Pistols: “I don’t believe illusion because too much is for real.”

Here, too, I was motivated (initially, at least) by jealousy. I started the book during the summer between my sophomore and junior years in college, which I spent in Cambridge, Massachusetts, working in a pizza joint soon to be named worst in greater Boston by Boston Magazine. My best friend Steve had transferred to NYU film school, where he was making his first short movies, and in our almost daily phone conversations, I would listen as he laid out creative issues: script, shots, story, the challenges of collaborating with a loose crew of fellow students, all of whom were caught up in projects of their own. From two hundred miles away, it sounded like a slice of heaven, although film was not then (nor is it now) my thing. What stirred me, rather, was that Steve was doing it, whatever that meant, pursuing something that seemed like destiny. I was twenty that summer, turning twenty-one in August, and I felt a growing pressure to be (how do I put this without reservation or irony?) great. I still recall those three months in Cambridge through the filter of what I was reading: Camus, Walker Percy, Frederick Exley, and, perhaps most importantly, Henry Miller, whose stirring admonition in the early pages of Tropic of Cancer—“We have evolved a new cosmogony of literature. It is to be a new Bible—The Last Book. All those who have anything to say will say it here—anonymously. After us not another book—not for a generation, at least”—I took as a call to arms. That was what I wanted also: to produce my own Last Book, to get everything I’d ever thought or felt on paper, to connect with the core of not just literature but also being, and in so doing to write my way out of circumstance and into fate. I had begun writing long fiction again that year: an eleven-thousand-word short story on which I worked mostly in the back of college classrooms, writing feverishly while my professors talked about whatever, under the illusion (if they were paying attention at all) that I was taking notes.

The novel started as a monologue, the novel started as a conceit. The idea was to do something short and striking, something like The Stranger, one hundred fifty pages in and out. Like Meursault, my protagonist was alienated, a first-person narrator alone in a room. Early on, I decided that the novel should unfold in six chapters, since the classic structure of the epic involved twelve; what I was writing was half an epic, the story of a boy not unlike myself but utterly adrift. Eventually, those six chapters grew to twelve, then to twenty-four: not half but twice an epic, in length if nothing else. This was in the late 1980s, after I blew up my 250-page draft into a 564-page revision, a manuscript so bloated that it literally could not be read. That’s a part of this story, although maybe not the most important part of this story; I have not looked at that set of pages in a very long time.

But here’s what is important: I sabotaged my own book. I did this in two ways, first by overthinking and then by overtalking, by telling everyone I knew everything about the work. Again, I was driven by theme, by concept. My first chapter was a thirty-page ode to masturbation, a metaphor (much too obvious) for the disconnection at the novel’s heart. It took me that whole first summer to complete it, and when I was done, I had no idea where to go. I wrote a second chapter in third person, experimented with past and present tenses; two-thirds of the way through the first draft, I was so lost, so hopelessly unmoored, that I decided to start again. That second draft became the book, or a version of it: I wrote my way through in nine months, start to finish, turning it in as my senior thesis, the story of a boy who could not deal with death and, in trying to run from it, wreaked havoc on everyone he’d ever known.

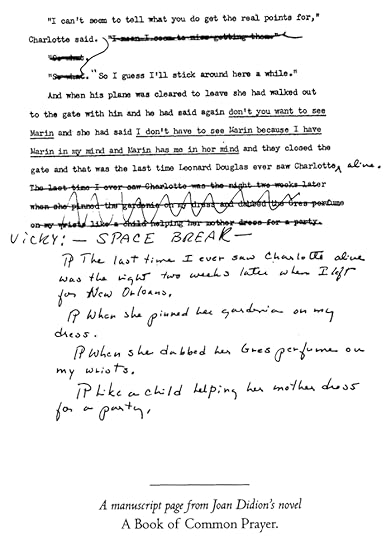

What did I understand of this? Nothing, it turned out, although that was not the difficulty. All these years later, I’ve learned that writing is an art of the unknown, that we write what we don’t know, rather than what we do. “I write,” Joan Didion tells us, “entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.” Implicit in such a statement is how little she grasps when she begins. What I didn’t know—what I wouldn’t know for decades—was how to sit with my uncertainty, how to let a narrative develop, how to let it be uncontrolled. I wanted to write not just a novel but a landmark novel, one that made big statements about what it meant to live in the world. Because of this, perhaps, the draft I finished felt thin to me: It was just the story of a boy, after all. I set it aside for two years, trying to figure out how to rework it; I talked and talked about its aesthetics, about what I wanted it to say. By the time I picked it up again, in late 1986, I felt straight-jacketed, defined by it: every conversation, no matter how trivial, seemed to cycle back to the subject of the book. The pressure was enormous, overwhelming, as if I were being watched. I spent two years on a third draft, another twelve months on a fourth … and then the novel petered out, over-written, over-discussed, picked at like the desiccated corpse of something I had killed by giving it too much attention, or the wrong sort of attention, something I should have abandoned years before.

Or no, not abandoned—not necessarily. This is complicated, and it’s a lesson I feel as if I’m just now learning, the great lesson, maybe, of this book. This past winter, nearly thirty years after I completed it, I read the novel in its shorter, senior-thesis form. It’s an apprentice work, no doubt about it, a boy writing about the difficulty of being a certain kind of boy. And yet, there’s also something compelling, a sense I get of myself as a young writer struggling to find a voice. I keep getting in my own way, loading up the narrative with frills, stylistic and otherwise, but there are places where the writing starts to sing. I remember the finest moments of its creation: when, deep in the middle of the book, I would go for a walk, have a conversation, read something in the newspaper, and all of it, every last whisper, would have some necessary link to what I was trying to construct. “Once you’re into a story,” Eudora Welty once observed, “everything seems to apply: what you overhear on a city bus is exactly what your character would say on the page you’re writing. Wherever you go, you meet part of your story.” I had not experienced this during my last attempt at novel-making because in that case I had not really been writing, although here I absolutely was. Reading my old manuscript, I was drawn back to those moments, that sense of connection, the idea of being so present in the book, in the world, that it felt as if all my boundaries had dissolved. This is what writing requires, and it’s a message I have carried with me … this and one other, which is never to talk about what I’m working on. An obvious point, perhaps, and not unrelated to my first first book. But then, I’m a slow learner, especially when it comes to recognizing that there is talking and there is writing, and for me, no way for them to coexist.

III

I wrote my third first book over the course of five years, from January 9, 1998 to January 3, 2003. It was a work of nonfiction that began with an elaborate lie, and even here, in telling you about it, I am lying also, for this was not my first book but my fourth. By the time I finished writing it, I had published three other books: a chapbook of poetry and two edited anthologies. It’s a lie, also, that I began the book in 1998, since it grew out of a long article I had written for LA Weekly, published in April 1999; it was this I started the year before.

Why all this emphasis on lying? At the risk of confusing matters, I didn’t—still don’t—see it that way. The lie that opened the book was not a willful falsehood but a misperception, a conflation of memory, a way of getting at what let’s call (yes) emotional truth. In the decade or so between abandoning my second first book and starting this one, I had grown engaged, enthralled, consumed with nonfiction, even though I wasn’t, then or now, exactly certain what that meant. For me, the key, as in fiction, was narrative: we were telling stories, not transmitting facts. I had, by this time, spent a long while, a decade or more, working as a journalist and I understood (or thought I did) the limitations of this way of thought. That summer, as I gathered material for my Weekly piece, I cut two photos out of newspapers, one from the Los Angeles Times and the other from the New York Times. Both had appeared on the same morning, and both featured Bill and Hillary Clinton, on the dais of some event together, interacting in very different ways. This was the summer of the impeachment, or, as Philip Roth would acidly describe it, “the summer of an enormous piety binge, a purity binge, when terrorism—which had replaced communism as the prevailing threat to the country’s security—was succeeded by cocksucking.” In the image from the Los Angeles Times, the Clintons were scowling, backs turned and glaring off into the middle distance as if on opposite sides of an unbridgeable divide. In the New York Times, they were facing each other and smiling broadly, as if sharing a private joke. What stories were these pictures telling? Which was accurate—or (if this is even relevant) true? That is the conundrum stirred by nonfiction, the question raised whenever we sit down and try to craft a narrative out of the chaos of our experience, whether that narrative is personal, or reported, or some combination of the two.

Did I mention that my book was about earthquakes? Or that it was a book I hadn’t necessarily meant to write? These are facts too, although what truths they reveal, I’m not sure I know. Earthquakes had been a fascination since before I came to California; I delayed moving west because I worried over living in a seismic zone. Eventually, I realized that a quake could hit while I was visiting just as easily as if I were a resident; what mattered was where you were standing when the shaking started, not where you made your home. It was random—or if not random, then expressive of a different order, one too vast, too sprawling, to be understood on our terms. Call it geologic as opposed to human time: that’s how the seismologists described it, although I preferred to see it as a strategy, a way to read time, even deep time, not as an abstraction but as concrete. This, for me, had always been the issue—evanescence, loss, the ephemerality of everything. It had been a driving concern of my second first book, and I was unsurprised to see it reemerge, albeit with a sharper focus, a newfound sense (if not quite acceptance) that the only possible response to anything was to remain present, to worry not about what might happen or what had already happened, but what was happening now. The idea, I recognized as I was writing, was that seismicity could root us, that in its unpredictable predictability, it offered an unlikely sort of faith. That was not what I had meant to write, but I’d learned by now to be responsive to the text—to give up, in other words, the desire for control that had waylaid me in those first two first books, the need to know from the outset what the point was, what the themes were, to tell the story from the top down rather than the bottom up.

The book scared the shit out of me; can I say that now? I didn’t know how to write it, even how to start. I sold it off the piece in the Weekly, spent six months watching the deadline ticking ever closer while I wrote sporadically, if at all. I made a couple of research trips, went through my notes and interviews. I’d hoped the article might offer a starting point, but the more I considered it, the more I realized that I would have to disassemble everything I had written, everything I was thinking, that I would have to approach it all anew. Unlike my first two first books, this one was not inspired by envy but by opportunity: in writing the initial story, I had gathered so much material—so much unused material—that I’d had the fantasy the book would write itself. I knew how I wanted it to open, the lie of a misremembered earthquake, but after that, I had no idea of where to go. Then, one afternoon, returning from a visit to the United States Geological Survey field office in Pasadena, I had a moment when I saw the structure whole. I was on the 110, just north of downtown, and I remember pulling onto the shoulder so I could write it down. And yet, this can’t be true; I drive that road now and can’t imagine where I might have stopped, even though I still have the sheet of yellow legal paper breaking down the book, scrawl nearly illegible. The book would be written in nine chapters, a nod to the Richter Scale, and these would function as a palindrome, with a hinge in the middle, like a peak. There would be echoes, reflections; the first and last chapters would start in the same way. I see now that I was building a frame that would be both solid enough and flexible enough to enfold the elements I wanted: research, personal narrative, meditation, science, commentary. But in that instant, I had the sense that I was inventing a form, and what astonished me when I finished two years later was just how closely I had adhered to the plan.

Of course, opportunity is a double-edged sword, which I came to realize as I worked. The book did not write itself, even with my chapter notes, and I often felt as if I was pressing up against the edges of my competence, as if I had bitten off too much. “Every book,” Annie Dillard has written, “has an intrinsic impossibility, which its writer discovers as soon as his first excitement dwindles. The problem … is insoluble … [a] prohibitive structural defect the writer wishes he had never noticed. He writes in spite of that.” For me, this defect was not in the book but in myself. I was not smart enough, not adept enough, not a good enough writer or thinker to live up to my premise, which felt, at times, as if it had been bestowed on me by someone else. Here’s Dillard again: “I do not so much write a book as sit up with it, as with a dying friend. During visiting hours, I enter its room with dread and sympathy for its many disorders. I hold its hand and hope it will get better.” This had been the case with my first two first books, and it was the case with this one too. The difference was … what? That I was older? Under contract? Certainly, yes, this was part of it. But even more, in blundering through those projects, I had learned something about how expectations can derail us, that the only remedy for fear (or, let’s be honest, ambition) is to sit down and work.

In the end, I wrote most of the book in a six-month push before my third deadline, the one my editor warned me not to miss. (What he said was: “The only way you should miss this deadline is if your car goes off a cliff and you are in it,” an admonition I often repeat to myself.) It seemed as if I’d been working on it forever, which in a sense I had. First first book, second first book, third first book … all components of a process, growing one out of the other in a way I’m still not sure I can explain. I’ve never felt this raw, this out of my element, this drive to expiate my insufficiencies by completing not just a draft but a final manuscript. I’ve written other books, each of which a different story, fraught with its own frustrations, failures, fears. Yet in those initial moments—initial moments? initial months, initial years—after finishing this book, all I knew was the numbness of relief. Thank God, I thought. That’s done with. Now I never have to do it again.

A version of this essay appears in the anthology My First Novel, which benefits PEN Center USA’s Emerging Voices program, and is published by Writers Tribe Books.

David L. Ulin is the author, most recently, of the novella Labyrinth. His other books include The Lost Art of Reading: Why Books Matter in a Distracted Time and Writing Los Angeles: A Literary Anthology, which received a 2002 California Book Award. He is book critic of the Los Angeles Times.

What We’re Loving: Screwball, Gothic, and Southern, To Name a Few

“We all find we cannot take on any more patients. We are all waiting for calls from superiors, pick up the phones each time hoping it is one of them, then find it is only another patient. The superiors of course think of us as patients and dread our calls.” Last Sunday I spent the hours between five and eleven A.M. finishing Renata Adler’s 1983 novel Pitch Dark, and they were the best four solid hours of my week. Thanks to NYRB Classics, which recently reissued Pitch Dark and Adler’s earlier novel, Speedboat, Adler is coming to be recognized as one of the great novelists of our time, on the strength of two slim books. Until now I had avoided Pitch Dark because it has the lesser reputation, and because Speedboat seemed to me so perfect, I couldn’t imagine lightning striking twice. But Pitch Dark—the story of a breakup, and of a solitary vacation gone awry—has all the suspense of a mystery, all the wit and companionability of an essay, and all the satirical worldliness I loved in Speedboat. Adler should be required reading for M.F.A students, at the considerable risk of shutting young writers down for lack of anything to say. The rest of us can read her for pleasure. —Lorin Stein

When you think about it, there really are a startling number of remarriages in screwball comedies: His Girl Friday, My Favorite Wife, The Philadelphia Story, The Awful Truth—and those are just the films in which Cary Grant ends up with an ex-wife. The philosopher Stanley Cavell takes on this phenomenon in 1981’s Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage, and argues that the plot device was more than just a way to flirt with the Hays Code. As he writes, “Can human beings change? The humor, and the sadness, of remarriage comedies can be said to result from the fact that we have no good answer to that question.” —Sadie O. Stein

The Fargo Moorhead Observer reports that a Fargo man has been arrested for clearing snow with a flamethrower. The man stated that he was simply “fed up with battling the elements” and that he did not possess the willpower necessary to “move four billion tons of whitebullsh-t.” —John Jeremiah Sullivan

Rarely do I read a magazines from cover to cover in one sitting. However, I couldn’t tear myself away from the Oxford American’s Southern Music Issue. Dedicated to the music of Tennessee, issue 83 gives you plenty of history: our own Southern editor John Jeremiah Sullivan on Junior Braithwaite, Rosco Gordon, and the birth of ska; an epic, posthumous memoir from Memphis blues guru Jim Dickinson; and a Christmas tale by Beasts of the Southern Wild scribe Lucy Alibar. One word of advice: clear your schedule and read near a computer, because every essay will result in a rabbit hole of song searches and obscure musicians. As Sullivan writes, “I wanted to be able to hold the evolution of [the music] in my head, just for a minute, to say how it happened, session by session. You can’t really do it. Even when you know everything.” But you can still try. —Justin Alvarez

Up until this week, I thought it was obvious that epithets, especially negative ones, invariably improve names. (Case in point—no one remembers Tsars Ivan “The Money Bag” and “The Fair.”) But through its poetic inventiveness, War Music, Christopher Logue’s teeming, modern, cinematic take on the Iliad, demonstrates how an epithet might become a bit of a monkey on your back: Achilles doesn’t want to become known as “Wondersulk” in years to come; “Mouse God Apollo” is also hard-done-by, legacy-wise. To counter, Zachary Mason’s project in The Lost Books of the Odyssey is to retouch forty-four episodes from Odysseus’s homecoming, untethering the characters, so that they develop beyond the remit set up by Homer’s fate-sealing descriptors. War Music is a classic, whereas Mason’s stories are self-consciously disposable. In tandem, reimagining in the true sense. —Lucie Elven

After reading Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle, I wasn’t too surprised to learn that the author had once received a letter from Freud, who wrote that he’d been avoiding Schnitzler for fear of running into his own doppelgänger. Just look at the subject matter of this short, hallucinatory narrative: sexual jealousy, adulterous dreams, an erotic encounter with a young woman in the presence of her dead father … it’s all there. Traumnovelle was the inspiration for Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, which means that one of the central challenges of reading this book is suppressing the mental image of Tom Cruise’s face, leering at you from fifteen years ago, or from the more sinister realms of your subconscious. —Fritz Huber

Some readers do the Gothic, some don’t. Poe never gave me chills. I never got doubles or ghosts. But I confess that certain pages of The Spectre of Alexander Wolf, the 1948 novella by the Ossetian Gaito Gazdanov, were scary enough that I skimmed them—then made myself go back and take them in. The story of a veteran of the Russian Civil War, forced to confront the man he left for dead, is truly troubling, a weird meditation on death, war, and sex, with an ending I don’t understand, and don’t want to. I can’t read Russian, but Bryan Karetnyk’s new translation makes you believe in the power of the original, not least when it’s most obscure. —L.S.

If you are in Manhattan before February 23, check out “The Armory Show at 100: Modern Art and Revolution” at the New York Historical Society. It’s a comprehensive and well-organized précis on the landmark art show that introduced New York to the European avant-garde, scandalizing and delighting critics in equal measure. The exhibit reunites now-classic works by Duchamp, Matisse, Picasso, Cézanne, and Gauguin with many names art history has forgotten, but just as interesting is the selection of parodies and writings the Armory Show spawned. As one contemporary New York Times critic wrote, the Cubism and Fauvism on display represented “a general movement to disrupt and degrade, if not to destroy, not only art, but literature and society, too.” —S.O.S.

And the Pantone Color of the Year Is…

My colleagues here at The Paris Review all know that I harbor an irrational aversion to any shade of purple, which reminds me of Lisa Frank stickers, aging hippies, and wizards. (All very well in their own ways, I suppose.) So it is with some reluctance that I report Pantone’s Color of the Year 2014: Radiant Orchid. Quoth the color-choosing powers,

Radiant Orchid blooms with confidence and magical warmth that intrigues the eye and sparks the imagination. It is an expressive, creative and embracing purple—one that draws you in with its beguiling charm. A captivating harmony of fuchsia, purple and pink undertones, Radiant Orchid emanates great joy, love and health.

And wizards. They forgot wizards.

Remembering Mandela, and Other News

“To have lived one’s life at the same time, and in the same natal country, as Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was a guidance and a privilege we South Africans shared.” Nadine Gordimer pays tribute.

In depressing news: the thirty-five-year-old National Poetry Series is in danger of closing, due to monetary issues.

Word is details of Morrissey’s relationship with Jake Owen Walters have been bowdlerized from the U.S. edition of his autobiography.

Pixies frontman Black Francis is writing a graphic novel. (Cue failure to come up with non-lame pun relating to any Pixies lyric.)

December 5, 2013

Blow Out Your Candles: An Elegy for Rose Williams

Celia Keenan-Bolger as Laura Wingfield in the current revival of The Glass Menagerie.

Some memory of Rose Williams underpins all of Tennessee Williams’s plays, but it was with the 1944 premiere of The Glass Menagerie that he both immortalized his sister and launched his Broadway career. Rose is the basis for Laura Wingfield, the withdrawn high school dropout who passes her days listening to old phonograph records and caring for her collection of glass animals while the world closes in around her. Williams based Tom Wingfield, Laura’s brother, on himself. The play depicts real events, up to a point; years before he wrote Menagerie, now in a successful run on Broadway, Williams left home to pursue his own writing ambitions. During that time, Rose descended into violent insanity. “To escape from a trap,” Williams wrote in Menagerie’s production notes about Tom Wingfield, “he has to act without pity.”

The Williams family moved from Clarksdale, Mississippi, to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1918. Prior to that, Rose and Tom lived “agreeable children’s lives under garden hoses in the hot summer,” according to Williams’s 1975 Memoirs. Nine-year-old Rose and seven-year-old Tom danced in the living room to music playing on the Victrola. The records were gifts from Cornelius Williams, their itinerant father, who was, like Laura and Tom’s father in Menagerie, a traveling salesman.

When Edwina Williams, Tennessee’s mother, became pregnant with her third child, Dakin, Cornelius accepted an office job at International Shoe’s St. Louis branch. The family moved into a small house, not nearly as squalid as the tenement apartment the Wingfields occupy onstage, but the tension between Williams’ parents made the atmosphere even more explosive. Cornelius, like the character of Tom and Laura’s father, was restless, alcoholic, and abusive. After the family moved to St. Louis, he was, however, not absent. Edwina and Cornelius’s marriage reeked of dysfunction; she withheld sex to punish his infidelity and abrasive presence. Williams recalled hearing his mother’s screams, futile protestations as his father cornered her in their bedroom. Tom, Rose, and Dakin would run out of the house and to the neighbors’ to escape.

As a teenager in St. Louis, Rose fought constantly with her parents and her life seemed constantly under cloud cover. Williams writes in Memoirs that Rose was a popular girl in high school, “but only for a brief while.” Her beauty was “mainly in her expressive green-gray eyes and in her curly auburn hair.” But her narrow shoulders and “state of anxiety when in male company inclined her to hunch them so they looked even narrower,” and her “strong-featured, very Williams head” looked too large for her small body. When on a date, Rose “would talk with an almost hysterical animation which few young men knew how to take.” The family moved so Rose could enter Soldan High, which is the name of the school Laura Wingfield attends in the play. But Rose dropped out, and Edwina enrolled her daughter in boarding school in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Her diagnosis of schizophrenia was still ten years off, but around this time Rose began to experience difficulty with life’s daily expectations. In a 1926 letter to her grandmother from boarding school, stored in Williams’s archive at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Rose writes, “I don’t know what was the matter with me except that I was so nervous that I couldn’t hold the glass to take my medicine in. I stayed in bed all day long and had a big dose of calomel and I feel better but still weak. I just had finished a music lesson, and Miss Butell nearly drove me wild. It makes me nervous as a cat.” It was a letter Blanche Dubois in A Streetcar Named Desire could have written.

After several months of erratic behavior and poor academic performance, Rose returned home in 1927. Cornelius sent her to Knoxville for several weeks, where his two sisters lived. “With a few inexpensive party dresses,” one which Williams describes in his memoirs as “just as green as the cat’s eyes,” Rose made her debut at a series of thrown-together social gatherings. In Knoxville, her brother remembered, Rose fell in love with “a young man who did not altogether respond in kind,” not unlike what happens to Laura Wingfield in Menagerie.

Rose made increasingly frequent trips to the doctor’s office, seeking relief from chronic stomach pain. The Williams family would not face their daughter’s underlying psychiatric disorder; a family friend and physician finally made a connection between her behavior and her apparent digestive ailments. “It’s not very pleasant to look back on that year and to know Rose knew she was going mad and to know, also that I was not too kind to my sister,” Williams would recall. “You see, for the first time in my life, I had become accepted by a group of young friends and my delighted relations with them preoccupied me to such an extent that I failed to properly observe the shadow falling on Rose.”

One night, when their parents took a weekend trip to the Ozarks, Williams threw a party. Rose, shocked by the drinking and prank phone calls, told their parents what happened. Williams recalled passing her on the staircase, “turning on her like a wildcat” and hissing, “I hate the sight of your ugly old face.”

By this point Williams had published his first story in The Smart Set, and had begun his drawn-out college career. He spent nine years a student, enrolled at the University of Missouri, the University of Washington, and the University of Iowa, with gap years in between. All the while, he wrote short stories, poems, and plays. In 1932, after he failed ROTC, Cornelius, who sharply favored Williams’s more conventional younger brother Dakin, removed his oldest from school and installed him as a clerk typist and errand boy at his shoe company’s downtown warehouse. Williams based Tom Wingfield’s story on those three years, before suffering his own nervous breakdown. Days after he returned home from the hospital, Williams remembers Rose walked into his bedroom “like a sonambulist” and announced, “We must all die together,” days after he returned from the hospital. “God damn it I was in no mood to consider group suicide with the family, not even at Rose’s suggestion—however appropriate the suggestion may have been,” Williams wrote in his memoirs.

Williams became aware of changes in Rose’s behavior, “little eccentricities” she had developed. Rose was now very quiet and would set a pitcher of ice water on the floor outside her door each night before bed. She would clutch the family dog, a Boston terrier named Jiggs, and Edwina would snap, “Rose, put Jiggs down, he wants to run about.” One time, driving her brother and his friends, Rose blanched when they began to make fun of a person they knew who was losing his mind. “You must never make fun of insanity,” Rose said, “it’s worse than death.”

Into the 1930s, when Tennessee Williams was still writing letters to agents and struggling to publish his short stories and produce his plays in university theaters, Rose’s hospital stays grew in number and length. In a 1937 letter to her own parents, Edwina Williams described visiting her daughter in the hospital: “Rose looked so yellow and bloated and she was so full of delusions, the visit made Tom ill so I can’t take him to see her again. I can’t have two of them there.”

In June, doctors finally diagnosed Rose with schizophrenia. In late July, she became violent, insinuating that her father tried to rape her and threatening to kill him, and the Williams installed their only daughter in St. Vincent’s Catholic Sanitarium in St. Louis, though shortly after she was transferred to the state hospital in Farmington.

By then, Williams had moved to California, where he landed work as an MGM scriptwriter. He lived at the Hotel Bel-Air “in great luxury at the expense of Warner Brothers,” he reports in a letter home, now in his archive at Columbia University. In Los Angeles, Williams began “a beautiful new story” that became Menagerie.

In 1943, Rose’s fitful, hysterical fantasies grew worse. In one of the first surgeries of its kind, doctors performed a frontal lobotomy. “I’m trying not to die, making every effort possible not to do so,” Rose wrote to Williams from the hospital bed after her lobotomy. “If I die you will know that I miss you twenty-four hours a day.” She added, “I want some black coffee, ice-cream on a chocolate bar, a good picture of you, Your devoted sister, Xxx Rose. P.S. Send me one 1 dollar for ice cream.”

The Glass Menagerie previewed in Chicago one year after Rose’s surgery; at the time she was still a ward of the state. The play ran for thirteen weeks before opening in New York to great critical acclaim. Williams wrote in a 1947 essay about fame’s corrupting influence; it was an event, he wrote, “which terminated one part of my life and began another as different in all external circumstances as could well be imagined.”

In the ensuing years, from Paris, Havana, Key West, Rome, and London, while navigating his own difficulties, Williams sent money and letters inquiring about Rose’s health and finances. At one point he brought her to New York to visit with his famous friends. In interviews, he made frequent references to his intentions to move his sister out of an institutional existence and into a Key West house he purchased for her in Coconut Grove. In an interview at the end of his life, before he choked fatally on a medicine bottle cap while alone in the Hotel Elysée in New York, Williams described driving Rose to Stoney Lodge in Ossining. “A lovely retreat where she has a pleasant room to herself with flowered wallpaper.” About his efforts on Rose’s behalf he said in an interview, “This is probably the best thing I’ve done with my life, besides a few bits of work.”

Privately, he acknowledged his debt to Rose. In 1942, writing to his agent Audrey Wood about a character who he hoped to yet again enliven with his sister’s mental paralysis, Williams wrote that “The great psychological trauma of my life was my sister’s tragedy, who had the same precarious balance of nerves that I have to live with, and who found it too much and escaped.”

Williams created indelible female characters by quoting directly from his mother and sister. “They talked with great charm. In most of my writings I try to recapture the charm of the way they talked,” he said in a 1965 interview. But it was Rose’s “charm,” shared by her mother, that led to her irreversible detachment from reality. The discrepancy between their fortunes caused him lifelong guilt. In the summer of 1938, when Rose went intractably insane, Williams wrote in his diary, “God must remember and have pity some day on one who loved as much as her little heart could hold—& more! Who should be there, little Rose? And me, here.”

Smut

By now, you will have heard that Manil Suri has won the coveted twenty-first Literary Review Bad Sex in Fiction Award, for a passage from his novel The City of Devi. The award-winning purple prose includes:

Surely supernovas explode that instant, somewhere, in some galaxy. The hut vanishes, and with it the sea and the sands—only Karun’s body, locked with mine, remains. We streak like superheroes past suns and solar systems, we dive through shoals of quarks and atomic nuclei. In celebration of our breakthrough fourth star, statisticians the world over rejoice.

Our vote may have been for The Victoria System, but hearty congratulations all around!

The Black Album

Vahap Avşar’s “Black Album,” currently on view at Istanbul’s lovely Rampa Gallery, is a marvelous show. Its quiet, metaphorical registers are a departure from Avşar’s previous style, which found its strength in more overtly political statements and deft manipulation of popular iconography. On the other hand, “Black Album,” curated by Esra Sagiredik, has the subtle touch of great poetry. As one walks through the three rooms, spread across two separate but adjacent sites, the accumulative effect of Avşar’s vision is powerful: the artworks peak between each other in rich rhymes and deeply felt themes and variations, fusing into a moving vision full of quiet but firm political engagement and profound metaphysical thought.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is the eponymous Black Album (2013), a series of twelve 76" x 40" paintings of metallic silver paint on tar felt. The silver paint spreads and folds freely over the tar, creating different studies of chiaroscuro, texture, and perspective. Their inspiration was the vast and dangerous mountainous landscape of eastern Turkey that Avşar traveled through by bus at night as a young man. The rich visual complexity of these paintings, however, challenges the primacy of the artist’s personal perspective, as they distinctly resemble the primordial tumbling of lava down cliffs and the roiling rivers of the Earth during its creation. The fact that the paintings simultaneously are both things is the point and the root of the poignancy of the works.

Meanwhile, Disguise Paintings (2013), an oil and print on canvas diptych, presents two separately framed works of isolated men seated, completely by happenstance, in almost identical postures, their faces pixelated and those pixels painted over in thick layers of paint. One man is dressed army fatigues and sitting on the bottom bunk of an army installation. The other is in a Bob Marley T-shirt, preparing tea in a colorful apartment walled with numerous portraits of Abraham Lincoln. The details of the paintings reveal much about these men, and their erased faces infuse the two paintings with a hard-earned allegorical mood.

The 20th Century As We Knew It (2011–2012), composed of four bronze busts on wooden pedestals, is a clever variation on the idea of artistic idolatry and influence. The busts—of Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Beuys, Cengiz Çekil, and Avşar himself—form a circle of admiration and are arranged in circular fashion, their gazes trained on each other, standing on their heads, the base of the pedestals occupying the positions where their faces would be. That viewers must stoop—or, if they’re up to it, stand on their heads—to take in the details is a marvelously playful and intelligent statement on how we admire and are admired.

Other standouts include The Road to Arguvan (2013), a short, single-channel video shot in the artist’s native Malatya Province. It follows a road devastated by an unknown force, leaving a long jagged chasm and rendering the road—once a major artery to the east—useless. The camera is handheld and jumpy. Near the end of the video a discarded television monitor appears nestled deep in the crack in the road, and stares back at the now-still camera. Another is the looped four-channel HD video, two-channel audio Shoot Out (2011), which surrounds you in a room: on opposite walls a man with a high-powered assault rifle lies on the floor, his focus trained on his gun’s sight; projected on each of the other two walls is a can of Coca-Cola on a stump of wood. The men load, aim, and fire at the cans; the viewer, deciding where to stand, is uncomfortably stuck in the middle.

While “Black Album” is not a retrospective, the exhibition includes earlier work such as the prints Night Shift (1988) and Negatives (1990), as well as the site-specific installation piece Final Warning, all perfect additions as they unearth and recontextualize some of the roots of Avşar’s newer work.

Dream Weaver

INTERVIEWER

You have said that writing is a hostile act; I have always wanted to ask you why.

JOAN DIDION

It’s hostile in that you’re trying to make somebody see something the way you see it, trying to impose your idea, your picture. It’s hostile to try to wrench around someone else’s mind that way. Quite often you want to tell somebody your dream, your nightmare. Well, nobody wants to hear about someone else’s dream, good or bad; nobody wants to walk around with it. The writer is always tricking the reader into listening to the dream.

—Joan Didion, the Art of Fiction No. 71

Underthings, and Other News

Busboys & Poets, the amazingly-named D.C. bookstore/cafe/performance space, is opening a sixth location!

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America has named Samuel R. Delany the 2013 science fiction and fantasy Grand Master. (Which is a great honor.)

“There’s never much mention of male underwear.” An ode to the great unmentionables of lit.

Remember! The St. Mark’s Bookshop auction is happening now! Visit the site (or the store) to help them relocate!

December 4, 2013

Pharmacopornography: An Interview with Beatriz Preciado

Photography credit: Internaz.

The student worker guarding the doors to Beatriz’s (B.’s) roundtable discussion at NYU meant business. I had been late leaving a class several blocks over at the less austere New School, and for that he was sorry, but I wouldn’t be able to fit in the room with B., José Muñoz, Avital Ronell, their cumulative brilliance, and about a hundred students who may or may have not been aware of the cultural master class that lay in store for them. “If someone leaves, you’re next in,” he assured me. I sat outside the lacquered double doors, deflated. Attending this discussion was my only chance to unpack, and from the horse’s mouth, this dense theoretical/narrative text I had been reading in a silo all summer. My interview with B. was scheduled for the next day.

Last July, when I first picked up the manuscript for what, in its final iteration, would be Beatriz Preciado’s Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, I was in the hills of Ecuador at a straight friend’s wedding, far from anything remotely related to queer theory, pharmacological engineering, Foucaultian lineage, or writing, for that matter. B. toggles between a personal account of using topical testosterone, Testogel, as a kind of performative homage to a fallen queer friend, and a cultural analysis that investigates how pharmaceutical companies politicize the body– down to the molecule. The idea is that Testo Junkie picks up where Foucault’s The History of Sexuality left off, a chronicle of sex in an ever increasingly consumerist and pornographically identified modernity. Its mix of personal narrative and theory softened my point of entry, but still, it was a lot to consider on my own.

So, I waited outside of those doors at NYU hoping to get in, and if I did, I prayed that the complexity of the pharmacopornographic dilemma would magically break down into a series of alphabet blocks: pointing to big business as the culprit and queer individuals taking hormones as the politicized bodies. Of course it was not so simple; when the student going to class or dinner or whatever left the auditorium, making room for me, I found through a series of revelatory slides and discussions that this issue is wide-reaching but fundamentally inherent in everything we do—all of us. And that was just the panel discussion.

When I sat down the next day with the calming but intellectually compelling B., B. laid out for me the universality of the pharmacopornographic regime, how all bodies have become biopolitical archives for the powers that be, but also how taking testosterone effects one’s cognitive experience, how we romanticize substances like opium and writing, and how the pill is just a blip on the blueprint that is you.

What was the beginning of your academic research?

I went to the New School, for philosophy. I had come from Spain on a Fulbright scholarship, which was very different then. Continental philosophy was more of what I studied at the New School. But what was great for me was that in this context, I had the great chance of meeting Derrida, who became for me a mentor. He was my teacher in a seminar with Ágnes Heller, and I spoke French, so it was fantastic. He was the most generous professor I ever had. He invited me to teach a seminar. I then ended up living in Paris, and now I’ve been there for the last ten years.

He was teaching a seminar on forgiveness and the gift, but at that time, he was studying Saint Augustine’s transformation in relationship to faith and becoming Catholic while at a point of personal transitioning. It was kind of like a story of transexuality. So, I went to France to speak about this. This was just before coming back to the states to do a Ph.D. in architecture.

Last night, you compared the case for the pill to the architecture of a building.

I was trying to give you an idea of how I traced a larger cartography, basically where the book would be inscribed. I finished the book in 2007–2008, so it’s been a while for me, but there is so much important information.

Did you want to add new chapters to Testo Junkie because of the amount of information you found after the fact?

Well, now I’m working on another book. It’s a political history of the body. Some of the images you saw last night come from the same research. This book goes a bit beyond Testo Junkie, but for me, it stands in the same area. It is not only about a personal experience of taking testosterone. There is more political theory behind it.

Formally, why did you move between the two in Testo Junkie?

It wasn’t an easy choice. Basically, I realized that, having been trained both in the European university and in the American university, there is this academic writing that is really dry, and for me, I knew from the very beginning that I didn’t want to continue doing that. I couldn’t do that. It’s interesting that you come from a writing background, because for me philosophy is basically a writing discipline.

In terms of writing as a research tool, academic writing was not what I wanted to do. So, I brought some of my academic background to another place, which was much more toward activism and art—those are my fields. I was using activism as a research methodology. I put activism into some of my questioning from being a feminist in the gay and lesbian movement, in the AIDS movement, and then in the transgender movement. I put those questions right on the table in the beginning as ways of producing knowledge.

The narrative of your Testogel rituals is very performative. Have you ever done performance art?

No, but it’s interesting—more and more people think I do performance, but it’s really not what I do. It’s writing for me that is the performative device. My refusal to engage in performance art is also in part because sexuality and gender are reduced to representation and translated into visual objects. I refuse the theatricality of that. Though, in Europe, people are using the book to create performances.

Do you mind?

I don’t mind if people choose to do that. Before this book, I wrote another called Countersexual Manifesto that is full of power contracts, sexual contracts that can be done like a score. It’s almost a performance. Definitely, the writing that I do has a performative dimension.

What was it like taking testosterone during this time?

I actually continue taking it. What I think is interesting about any molecule, not just testosterone, is that everything is a question of dosage. With this same molecule, some of my friends have become something very close to what looks like a cis male. In my case, I take very low doses, so that I may continue the way that I am for a little bit, maybe not much longer. I don’t know exactly what I’ll do next. Some people ask me, Do you want a gender reassignment? I don’t know—probably, if I keep taking testosterone, there will be a point where I will probably say yes, but that’s not exactly my aim. I also thought about the project as a kind of collective adventure, in a sense, because I’m thinking about the body, not even just my own, as this kind of a living political fiction.

That’s how I see the body, as a living political archive. You already have this archive. It’s not like you choose things that are more or less outside of yourself to add onto it. You realize that your body is really dense, stratified, and huge. There are connections and relationships that are already there. If you carefully look at it, you realize that your body archive is connected to the history of the city, the history of design, technologies, and goes back to the invention of agriculture like eighty thousand years ago. Your body is the body of the planet. When I add a few molecules of testosterone, in a huge living archive, well that’s just a minor detail. It’s a way of intensification in terms of a cognitive experience—suddenly you are intensifying processes that are already going on in your body.

How much of this added cognition is the testosterone, and how much of it is the experiment itself?

Once you refuse the legal and medical protocol and you decide to take testosterone, you immediately have to set up your own protocol for use. You have to decide on how much and when—then a whole discipline or counterdiscipline appears. This makes you become more aware of things that you are taking, not only on a psychological level, but you also immediately start asking yourself questions like, What is this testosterone that I am taking, where is this coming from, how is this being made, how has this been fabricated both in terms of molecules and in terms of signifiers? Suddenly you see this moment of self-intoxication, and not only with testosterone—suddenly everything else appears. You become resistant to the body techniques that are being constructed constantly around you. Every other technique has to be rearranged. With this perspective applied to too many things at once, you can end up with this kind of paranoid image of the world. It’s interesting. You are then forced to produce your own knowledge, a knowledge that is not given to you. Any girl today who is around fourteen years old might go to the doctor and the doctor might immediately say, The pill, as if the female body would automatically be a reproductive body without any medical arrangements, without even knowing anything about the economy of fluids and organs in this person. They assume you are a cis female, so you are going to be taking the pill, or you’re a gay Latino guy between twenty-one and thirty-five and you’ll be taking these anti-AIDS molecules. This knowledge production cannot be done alone.

There is an allure to the testosterone use in the book that feels a bit like an homage to opium.

Yes, there’s always a temptation when reading Testo Junkie to think of me as a very romantic individual. But this could be the relationship we have with any one object, technology, image, and when I say any technologies it includes writing, which is the oldest technology of all. By collectively, I mean that of course you are always in relationships, whether institutionally or with doctors. Somebody has to give you the substance. You end up creating a new network in order to produce that knowledge. As soon as I started taking testosterone, I found tons of people around the world who are doing the same thing. I was able to ask them how much they were taking and how it is for them. There is no scientific knowledge about it, really—nobody knows what can really happen.

When I was researching testosterone, I found that testosterone hasn’t been available for very long as a substance. It became available probably after the beginning of the twentieth century. Now in the U.S., if you are a cis male, you can buy it if you have a “deficiency,” but there is always a potential deficiency of testosterone.

Right, because who is the one male who actually has the perfect amount of testosterone in him?

Exactly. It’s very interesting, because it then means that testosterone is defined by masculinity and masculinity by testosterone, and we don’t know exactly what either means.

I was surprised to see how not only testosterone was this marketed but unknown molecule, but also the pill, which is one of the most used substances in the history of humanity. Everybody is taking it and we don’t know much about it.

Your research shows that the pill produces technical periods.

Honestly, when I was doing my research on the pill and read this, I couldn’t believe it. We’ve been working with all of these theories of gender performativity for so long, the last ten years, and we have a lot of weird ideas, but when you see what was happening in the 1950s, you find that it was even worse than anything we ever imagined. It’s what I refer to in the book as “biocamp,” this kind of theatricality or mimesis being taken to the level of the production of the organic. In the 1950s, if you took the first pill consistently, you would stop because you wouldn’t produce monthly bleedings any longer; your period would stop. The first pill was equally efficient in terms of preventing pregnancy, but the Food and Drug Administration entered into a type of epistemological crisis. Women wouldn’t be women anymore if they were not being marked by the difference of bleeding every month. I started speaking about it last night—sometimes I like to present a blow down of information and then run away. But basically, the invention of the pill implies the end of disciplinary heterosexuality. Of course, we continue using that notion as if it isn’t the end, but the heterosexuality we live with today is different. They decided at that point that it was necessary to go into research and find a way of reproducing the bleedings. You have to imagine—between 1960 and 1965, Enovid gained ten million consumers. It was a mass consumption.

I have these conversations with feminists from the seventies who of course see the pill as this instrument of sexual liberation—I’m not saying that it’s not or that it can’t be used as an emancipating technique, but I think we have to acknowledge the history behind it. It’s a history that has to do with colonialism and racism, and technically reproducing gender differences. As soon as we acknowledge that, we might think that it’s good to actually look for new techniques.

Do you think that the pill then is more politically charged than, say, the condom?

No, I think the condom is very charged. I think all technologies that actually interfere with the management of reproduction of sexuality are very politically charged. On the one side, the management of masculinity and sperm by the condom has basically been used for millions of years. That information was amazing to me when I was working on AIDS projects. There were all these discussions going on in the eighties and nineties about condoms that reproduce the discussions that were going on in the seventeenth century. This was at the same time that new reproductive technologies were occurring—the possibility of in vitro fertilization and so on. The condom is a very interesting object and technique. The French called it “second skin.” I refer to it as the necropolitical body, the body that has been marked by its relationship to power techniques of giving death. That body, up until the beginning of anatomy as a technique to make the inner body visible, was mostly a plain surface or a skin. You have this masculine body that is at the center of political power for all these years, as a skin that contains a soul, and this soul is producing sperm. It was a kind of transcendental power. The skin thing is also interesting in relation to writing. All of these ancient technologies that function as necropolitical techniques of giving death work like writing technologies on the body. Preventing the circulation of sperm prevents in a way the expansion of male virility, divine power. I still see this sometimes in the debate about AIDS.

Can you talk about the AIDS preventative medication PEP and its relation to your pharmacopornographic theory?

For the very first time, pharmacological technologies will be addressed to the male body. It started with Viagra. If the pill was inventing these technical bleedings, Viagra was inventing technical virility. If you are male and not able to have an erection and ejaculate properly, then of course your core virility is being diminished. It’s a pharmacological, theatrical fiction of virility. But what interested me about the question from last night was that I saw how drugs are being invented now around AIDS in relation to the pill. It is the same industry, the pharmacological industry and research groups. The pill is a preventive technique, preventative of something that could eventually happen. You take it and you haven’t even done anything yet. It’s funny, sometimes I’m talking to my straight friends who take the pill and they say, How useless is my life. I’ve taken the pill for five months, and I’m not even having any sex. The pill is like a prosthetic machine to produce the future. You are taking it as a way of constructing time and a relationship to time. This also defines subjectivity and how temporality is being structured. The pill became a lifetime drug for women. What is happening with AIDS research is that they are also thinking of consumers who can become lifetime consumers. This is how the pharmacopornographic regime works. The disciplinary regime would basically tell you not to have sex outside of reproduction. They would say, Do not go out and have sex in that back room. The pharmacopornographic regime says, No, no, you can fuck as much as you want, but be sure you take your pill. The management of subjectivity and identity is not so related to the body and the movements of the body, but much more to the very materiality of the body. The level of control has been downgraded to a molecular level. Not having sex on the pill doesn’t matter because the pill is also given to improve the quality of your skin, so it becomes cosmetic. Because of the disciplinary regime, in order for you to be properly subjectified, you had to go through these architectures. From the fifteenth century up until the mid-twentieth century, normalization processes of gender and race had to do with special segmentation—separate toilets, schools, even within the city there was a special type of segregation. It all had to do with placing the body within a space or an architecture. Now it is much more complex—the segregation is going on within the body itself. This implies that the identity politics we’ve been practicing the last few years might not be enough of a way of resisting the new technologies of producing subjectivity that are building us right now.

Do you think tools like Testogel and estrogen create more of a democracy in the hands of the marginalized?

We don’t have to be afraid of questioning democracy, but I’m also very interested in disability, nonfunctional bodies, other forms of functionality and cognitive experiences. Democracy and the model of democracy is still too much about able bodies, masculine able bodies that have control over the body and the individual’s choices, and have dialogues and communications in a type of parliament. We have to imagine politics that go beyond the parliament, otherwise how are we going to imagine politics with nonhumans, or the planet? I am interested in the model of the body as subjectivity that is working within democracy, and then goes beyond that. Also, the global situation that we are in requires a revolution. There is no other option. We must manage to actually create some political alliance of minority bodies, to create a revolution together. Otherwise these necropolitical techniques will take the planet over. In this sense, I have a very utopian way of thinking, of rethinking new technologies of government and the body, creating new regimes of knowledge. The domain of politics has to be taken over by artists. Politics and philosophy both are our domains. The problem is that they have been expropriated and taken by other entities for the production of capital or just for the sake of power itself. That’s the definition of revolution, when the political domain becomes art. We desperately need it.

What was the benefit to designing your own protocol, of being the lab rat in your experiments with testosterone?

It’s interesting that you mention design. Design is at the center of the pharmacopornographic more than anything else, because design invents techniques of the body. Chairs and buildings are designed relative to the body, and body techniques define relationships between body, space and time, and the spaces that you can or cannot use. It’s crucial that activists with the right questions permeate these fields. Designers are typically driven by the commercial. In terms of becoming a rat in your own laboratory, that’s what happens when you write. Writing is becoming the rat in your own laboratory. Writing is the main technology of production of subjectivity that we invented a really long time ago. What I do in the book is underlying this, making it hyperbolic through the invention of the protocol. There are moments when you go beyond what is traditionally done, in research and within the academy, that you think you are losing your mind, but you have to give yourself a kind of reference of heroes, whoever it is, be it Freud or Foucault.

How did Freud influence Testo Junkie?

I was looking through all of these books for research when I was building up my protocol for testosterone. Freud learned that cocaine was being produced by pharmacological companies in Germany because of the war. At the end of the nineteenth century it was being used for barbarian soldiers. They would go to war exhausted, and were able to take these cocaine pills for energy. What was very funny was reading this text by Freud called About Cocaine. He wrote a letter to the company saying he was a psychologist and would like 500 grams of pure cocaine that would eventually be delivered to his house. As soon as he got the cocaine, he tried it and began his protocol. He immediately knew that this would change the psychological/psychiatric field. He thought it would be the substance of the century. He actually wrote letters to his future wife saying, “Dear Martha, I bought five hundred grams of cocaine. I have a project.” So, when I was there with my testosterone, I realized that this was the relationship I had to the book. I had this testosterone and I had a project. Nietzsche, Freud, and Benjamin used self-experimentation as a form of knowledge production. It does not only happen with molecules and substances, but it can also happen in other areas. Every crucial book—piece of literature—in a way, somehow, has a certain technique or technology attached to it.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers