The Paris Review's Blog, page 754

December 17, 2013

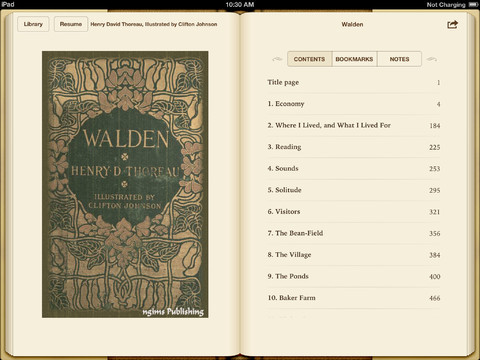

Thoreau and the iPad

Recently I took my iPad to a park across a lake, sat under a tree facing the water, and started reading the e-book version of Walden, Henry David Thoreau’s classic avowal of the possibility of, as well as the necessity for, simplicity amid modern life’s profusion and superfluity. Cognitive dissonance doesn’t get much more dissonant than this.

“Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys … improved means to an unimproved end,” wrote the handyman sage in the book’s first chapter, titled “Economy.” Few toys are prettier than the iPad, and its prettiness is by no means a feat of economy. Its minimalism, for one, belies the complexity of thought that went into its design, while its ease of use obscures the intricacy of the industry behind its manufacture. That there’s nothing new and improved about its ends should be evident from the resemblance between the categories of apps in the App Store and those of stores listed on the touchscreen directory at the entrance of shopping malls—that harried shopper’s guide to the nonvirtual versions of apps for games, books, sports, lifestyle, and even social networking. Or especially social networking, come to think of it, when you consider that the din from the food court or the theater lobby is nothing more than the noise from so many short messages being broadcast on an unmetered network with unlimited bandwidth.

But what does it matter if my iPad is merely a prettier means to pedestrian ends that are, in Thoreau’s words, “already but too easy to arrive at”? Does that make it one more toy to be transcended or tucked out of sight when meditating on sufficiency? I also own a paperback edition of Walden, its pages worn yellow with age and marred with the fervent notes of my much younger self. It has none of the iPad’s high-precision electronics; the letter m is smudged in several places, and yet it’s lost none of its functionality. And apart from enlightenment, it has only one other app, as a paperweight. Is this nonmultitasking relic the authentic medium for the all-in-one manifesto and proof-of-concept of the uncluttered life?

Thoreau would presumably have thought so. Although he did not list books among the necessities of life, he ranked them highly enough, next to the knife and the wheelbarrow, in fact, as one of the few articles that can be obtained at such little cost that they can be brought along on any wilderness retreat without disrupting its sense of freedom from urban encumbrance. If simplicity were a mere matter of thrift, then my copy of Walden, bought for the price of a tall latte, and certainly cheaper than a wheelbarrow, is indeed more fitting than my iPad as a companion on a furlough from the copious cares of networked living.

And that is exactly where these deliberations would have ended if my love of gadgets had capitulated to the logic of tools and coffee. But I’m the kind of person that Thoreau’s friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson had in mind when he wrote of creatures of a given temperament who “resist the conclusion in the morning, but adopt it as the evening wears on.” I made some hasty conclusions about the iPad’s worth when I decided to buy one, and my conscience demands that the facts fit them.

The facts, as I’ve culled them, don’t come any fitter. My paperback copy of Walden is not just a vehicle for transcendental philosophy: it is also the result of a tightly orchestrated chain of industrial events spanning the globe—from the cultivation of trees and their distillation into pulp, to the pressing of ink to paper by machines run by arrays of circuit boards not too different from those found on the assembly lines of electronic gadgets like, um, the iPad. It is, like the rest of its log-begotten kind, the product of a world of toil no less taxing than Thoreau’s favorite spiritless enterprise, the laying of railroad tracks in nineteenth-century America.

I will be generous here and not make much of the toll that book publishing exacts on the environment, except to observe the irony of contemplating the grace of life in the woods by reading Walden in its pulp form. What to me is a darker stain on the moral prestige of books in general and their right as bearers of transcendentalist doctrine in particular is their thick ledger of human resource. The million Irishmen who Thoreau posited as asking, “Is not this railroad which we have built a good thing?” have been replaced by a truly multicultural mix of people tending pulpwood in far-flung countries with varied climates and literary tastes. If these people were to look up from the furrows they’ve made in the ground to ask if this book they’re building is a good thing, the avid reader of Thoreau would be tempted to dole out his original response: “Yes, I answer, comparatively good, that is, you might have done worse, but I wish, as you are brothers of mine, that you could have spent your time better than digging in this dirt.”

I will be generous here and not make much of the toll that book publishing exacts on the environment, except to observe the irony of contemplating the grace of life in the woods by reading Walden in its pulp form. What to me is a darker stain on the moral prestige of books in general and their right as bearers of transcendentalist doctrine in particular is their thick ledger of human resource. The million Irishmen who Thoreau posited as asking, “Is not this railroad which we have built a good thing?” have been replaced by a truly multicultural mix of people tending pulpwood in far-flung countries with varied climates and literary tastes. If these people were to look up from the furrows they’ve made in the ground to ask if this book they’re building is a good thing, the avid reader of Thoreau would be tempted to dole out his original response: “Yes, I answer, comparatively good, that is, you might have done worse, but I wish, as you are brothers of mine, that you could have spent your time better than digging in this dirt.”

The same innuendos can be made about my iPad, of course, with the Chinese factory worker standing in for the Irish tracklayer or the Brazilian logger. In fact, just about any modern product is susceptible to such insinuations, which could be made against pretty much anything produced in factories or farms manned by people whose waking hours could be better spent on non–product-related pursuits. Thoreau conceded as much. “It certainly is better,” he wrote, “to accept the advantages, though so dearly bought, which the invention and industry of mankind offer.” It was a hard pill to swallow, and one can almost hear him struggling to regurgitate it as he built his cabin, singing

Men say they know many things;

But lo! they have taken wings –

The arts and sciences,

And a thousand appliances;

The wind that blows

Is all that any body knows.

But swallow it he did, and we have, as a result, one of the most eloquent examples of specious exposition ever set to prose—a demonstration of the Spartan life corroborated with the records of goods he’d acquired dirt cheap from people whose un-Spartan lifestyles often made such trade the exigent means of supporting their own extraneous pursuits and acquisitions. Thoreau’s retreat was, remarked the late John Updike, a luxury “financed by the surplus that an interwoven, slave-driving economy generates.”

My iPad is arguably the epitome of such luxury, one subsidized besides by a surplus of able minds and bodies from the world’s most populous assembly-line job agency. By all accounts, Thoreau, a Harvard graduate who used his own money to publish his first book, belonged to the class of people who, though not rock-star rich, could well afford such frill. If he had somehow been transplanted into our own time, perhaps by some mischievous time traveler out to show him that his admonitions have gone largely unheeded, his attention would undoubtedly be drawn to the iPad as one of the many unimproved means he can purchase with the money he’s sure to make simply by selling facsimiles of his journals and manuscripts. If I could play one role in this fantasy, I’d write myself in as the Apple store clerk faced with the formidable task of showing him the iPad and explaining exactly what the device is good for.

I’d have to tread carefully, of course, for here is the man who called it his greatest skill to want but little and whose writings exhorted me and other aspiring drifters in our youths to keep our accounts on our thumbnails even as we spent our parents’ money. I’d start by telling him that the iPad serves different ends for different people, but a person of his inclination will find in it a journal and a portable library. A quick scribble on the notepad app and a skim through the digital version of works by Montaigne, Voltaire, and his own spiritual kin, Walt Whitman, should make for more than ample exhibits. Then, just as his eyes start to glaze over, I’d draw his attention to the iPad’s unique advantage as the literary implement of choice to take along on a retreat to a secluded, electricity-deprived cabin—that advantage being its transient and virtually ephemeral battery life.

To understand this, one must first remember that Thoreau’s sojourn at Walden was by no means a withdrawal from society, a point he made clear by recounting some of his nearly daily strolls to town and conversations with the friends he made and often sought in the neighborhood of his cabin. Nor was it an abstinence from technology as it stood during his time. One of his first acts at Walden was to avail himself of a modest yet enduring piece of technology, one that felled entire forests long before the chainsaw: the ax. And despite his dismissal of news as gossip read by “old women over their tea,” he wasn’t above perusing the newspaper that served as wrapping for his dinner. If anything, Thoreau proved Spinoza’s axiom that “we can never bring it about that we need nothing outside ourselves for preservation.”

Temperance, not abnegation, therefore, is the real lesson, partly written and largely mimed, of the sermon that is Walden. The transcendentalist in the woods needs his journal and his books—they preserve his humanity no less than clothing or shelter—but they, too, need to be reined in. And what better rein on bookishness than the iPad’s battery, which lets him read and write only so much and then no more. No more, that is, until his next trip to town, where he can charge it as he eats his dinner, perhaps while browsing the news over a cup of tea. The roughly three hours it takes to restore it to full charge should give him enough time, moreover, to check in with a friend or, if he can find a safe place to leave it, wander through the shops or even see a movie. Enough time, in other words, to reconnect, in both the old and the new sense of the word.

The iPad’s battery meter itself has a significance that Thoreau, a born bookkeeper, should find especially apt. When the device is removed from a power source, the meter becomes a virtual tally, crude yet irrefutable, of its owner’s outlay of attention, that most profitable and most squandered of capitals. One full charge on the iPad is worth about ten hours of use as an e-book reader or a journal, but someone with more eclectic interests can go for days without recharging. Longer, even, if he takes short fasts from all literary work, as Thoreau did one summer, when he spent whole mornings sitting still, “rapt in a reverie,” unable or unwilling to “sacrifice the bloom of the present moment to any work, whether of the head or hands.” Walden’s revelations may well have been the harvests of those mornings, and the iPad-toting Thoreauvian should be mindful that every tick of its battery is so many minutes spent on what may be mere preparation for, if not diversion from, such moments.

A century and a half after Thoreau’s death, Walden has become, like Thoreau’s beloved classics, a “treasured wealth of the world and the fit inheritance of generations.” It is also poised, well into the e-book era, to outlive its original medium. If our fantasies come to fruition, someday we’ll be transmitting it directly into our brains, to be recalled rather than read, like a gospel learned by heart. It will no doubt outlast the iPad, too, and its many inevitable iterations, shedding them one after the other, like so much outdated apparel. In this succession of hosts, each device in its turn will carry Thoreau’s words with little loss of resonance, for their prescription of discipline and moderation is, fortunately enough, compatible with technology in all of its incompatible variety.

Dannie Zarate lives in Australia with his wife and is an ardent student of the Indonesian culinary arts.

Many Happy Returns, Penelope Fitzgerald

Image via the Guardian.

“Everyone in Penelope Fitzgerald’s family called her Mops, no one ever called her Penelope unless they met her later in life. And she didn’t like the name Penelope. But it would seem very peculiar for me to call her Mops all the way through.” —Hermione Lee, the Art of Biography No. 4

Apollinaire on Trial, and Other News

Apollinaire (or, at any rate, his Turkish publisher) is on trial in Istanbul.

Sofia Coppola is set to adapt Alysia Abbott’s 1970s San Francisco-set Fairyland: A Memoir of My Father.

The American Library Association has named ten librarians from across the United States to be winners of the I Love My Librarian award. Each honoree will receive $5,000.

Buzzfeed brings us fourteen places to talk to a stranger about books. Elevators and playgrounds feel potentially problematic, but what do we know?

December 16, 2013

A Corner of Paradise

The opening to Betsy Karel’s new book of photography, Conjuring Paradise, is a poem by Kay Ryan titled “Slant.” It wonders at the randomness of loss, suspecting that its arbitrariness may be otherwise:

Does a skew

insinuate into the visual plane; do

the avenues begin to

strain for the diagonal?

Maybe there is always

this lean, this slight

slant …

Her imagining of a plan behind loss has a theatrical cant—the man behind the curtain—but the poet’s conclusion that it’s perhaps wiser to let this observation go unnamed is a subtle riff on Emily Dickinson’s “tell all the truth but tell it slant.” Both poems imply that the truth of the matter is always set obliquely, and thus never fully seen. What, then, do we really understand of it?

Karel’s images follow the same principle, looking at paradise through the lens of loss. She visited Waikiki, on the island of Oʻahu, in 2004 with her husband, who was dying of cancer; he found solace and pleasure in the tropical resorts, his symptoms temporarily alleviated. After his death, Karel returned to the area to make the photographs in this book, and the images she captured reflect this uneasy enterprise. Torpid and tanned beachgoers, ocean-themed decor, gifts shops and bars, the aqua splendor of swimming pools—each scene feels caught between a facile, picturesque serenity and a jarring sense of unreality. Ryan’s impression of a “skew” in the “visual plane” is rendered literal in Karel’s photographs: the strange angle of a balcony set against the sea, of painted waves rolling over a hallway, of a flashy sports car parked, as though forgotten, in the blank corner of an entryway.

Tropical splendor is just out of reach, as when plumes of sea spray block access to the ocean or the rich Hawaiian landscape is supplanted by a painted backdrop (can those smiling tourists discern the difference?). In one image, a giant screen, partially unfurled, hangs between Karel’s camera and the promise of palm trees and blue sky. If you can only see paradise out of the corner of your eye or through a squint, Karel seems to ask, is it real?

Recapping Dante: Canto 11, or Foul Smells and Boring Theological Discussions Ahead

Detail of a miniature of Dante and Virgil looking into the tomb of Pope Anastasius.

As Dante and Virgil make their way through the City of Dis (and see the tomb of yet another pope), Dante has a moment very much like the one where you open the bathroom door at work and are assaulted by the fumes of a previous occupant’s abomination. Of course, in this case, it’s the smell of lower hell. Virgil gives Dante a few minutes to compose himself and assures him that he’ll find a way to make the time pass while Virgil describes the rest of hell. In many ways, canto 11 is a lot like canto 2—it’s a way of briefly making everything clear to both Dante and to the reader. It’s Virgil’s way of saying, I know what you’re thinking; did we go through six circles of hell, or only five? Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement, I kind of lost track myself. Let’s briefly recap!

And to be fair, Dante the poet couldn’t have picked a better moment to pause and explain what’s going on, because it’s starting to get very confusing.

Virgil explains that the next circles of hell will be reserved for the violent, with sinners ranked by the severity of their sins: violence against others, violence against oneself or one’s property, and then the worst—violence against God (things like sodomy and eating lobster rolls). The next circle is for the fraudulent—those who committed fraud against the mistrusting (robbery), and the following circle is reserved for the worst kind of sinners—those who committed fraud against people who trusted them. Virgil explains that human beings are meant to have a natural love for one another; to commit any kind of fraud is to betray this. But treacherous fraud against the trusting is even worse because it betrays an even greater bond: natural love supplemented by a bond of faith. It is so abhorrent that, as Virgil says, “In the tightest circle, the center of the universe and seat of Dis, all traitors are consumed eternally.”

At this point, Dante basically says, I don’t really get it, and asks why the other sinners they saw in the earlier parts of hell were not confined to the city of Dis as well. Virgil’s response is appropriately frustrated: Dante, just when I thought you couldn’t get any stupider you ask a stupid Florentine question like that. Use your head for a minute. Outside of Dis, Virgil explains, though the sins are damnable, they are not sins of malice. For instance, Francesca didn’t sleep with Paolo because she was trying to hurt her husband. The prodigal may have been horrible people, but their sins weren’t committed with the intentions of causing harm to others. Then Virgil asks Dante if he’s even read Aristotle, because if he had, he would understand that incontinence offends God less than malice. God, Dante, read a book.

This canto is one of the shortest in the entire poem. In a strange way, we can see here a Dante we don’t know very well—Dante the comedian. He follows up a canto like canto 10 with a short joke about how hell reeks, and a preemptive, indirect apology to the reader for the upcoming pedantic lecture, and later in the canto he allows himself to be berated and called an idiot by his mentor. It’s not to say that canto 11 puts the comedy back in Divine Comedy, but indeed in canto 11 a good-natured, sardonic facet of the great poet’s character slips through for a second. Even Neil Simon couldn’t write this stuff.

Alexander Aciman is the author of Twitterature. He has written for the New York Times, Tablet, the Wall Street Journal, and TIME. Follow him on Twitter at @acimania.

Holidays, via The Paris Review

Richard Anuszkiewicz, Untitled.

We have already reminded you about the wonderful gift that is a full year—or even two, or three!—of the best in prose, poetry, interviews, and art. But don’t forget, there is also the Paris Review print series, allowing you to share an archive of nearly fifty years of contemporary masterworks.

Subscribe now! And see our print series here.

Darcy vs. Knightley, and Other News

Elif Batuman defends the end-of-year list, in a list.

Here are all the best books of 2013 lists.

Celebrity death match, Austen style: favorite Mr. Darcy versus dark horse Mr. Knightley.

Geek, “a person who is very knowledgeable and enthusiastic about a specific subject,” has been named the word of the year by the Collins online dictionary.

December 13, 2013

What We’re Loving: Twain, Gilbert, Visconti

Late at night for the last few weeks I’ve been rereading The Innocents Abroad. I think Mark Twain will always be my favorite writer, or at least the one I enjoy most easily, even when he’s not being great. The Innocents Abroad—his magazine account of a tour through Europe and the Holy Land—is not great Twain. He knows nothing about art. (Mainly he hates it.) He’s bigoted toward Muslims and Catholics, in his grumpy unserious way. He spends most of the trip tired, skeptical, and bored, at times you can almost see him counting the words in a sunset, but for me this is all part of his charm. Twain wears his shtick so easily; a book like The Innocents Abroad reminds you that he was not only our first great allegorist of race, or our first great master of dialect, or the one who first understood American prose as such, or the perpetrator of several extremely weird book-length satires—he also happened to be the David Sedaris of his time. Which is to say, a humorist, an easy writer, who speaks to what is ordinary and irredeemably podunk in us all. —Lorin Stein

I was lucky enough to catch the new print of Sandra at New York’s Film Forum last week, but it is well worth seeking out on your own: Luchino Visconti’s lush 1965 retelling of the Electra myth is gorgeous, campy, and lurid beyond measure. Claudia Cardinale and Jean Sorel are undressed for absolutely no reason far more often than they need to be; there’s Italian palazzos, stunning scenery, and just a pinch of “Blood of the Walsungs”-style incest. Need I say more? —Sadie O. Stein

Following the sage advice of my Paris Review Facebook feed, I read Jack Gilbert’s Art of Poetry interview from issue 175. Two things, in particular, felt essential to his work: his romantic distain for “clever” poetry—i.e., poems that are “extraordinarily deft” when it comes to technique, but hollow at their core; and his unabashed admission that of course his poems are taken directly from experience—“why would I invent them?” One need only pick up his collection The Great Fires. In “Finding Something,” we see Gilbert caring for his wife Michiko as she is dying of cancer. He describes a scene both unbearably sad and totally mundane: she has become so weak that she cannot go to the bathroom without leaning against her husband’s legs. There’s nothing even remotely clever about the final lines:

How strange and fine to get so near to it.

The arches of her feet are like voices

of children calling in the grove of lemon trees,

where my heart is as helpless as crushed birds.

—Fritz Huber

Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays is only 214 quick pages, yet in these eighty-four brief chapters she to leave us with a nightmare that we can neither explain nor get enough of. It’s a relatively sparse novel, but still a hypnotizing, morbid story of a wounded woman incarcerated by the misfortunes of her own making. Every word is laden with Maria’s torment, heavy with cafard; yet there’s a peculiar pleasure derived from Didion’s control over language. “All day she was faint with vertigo, sunk in a world where great power grids converged, throbbing lines plunged finally into the shallow canyon below the dam’s face, elevators like coffins dropped into the bowels of the earth itself.” —Caitlin Youngquist

This morning, Lorin, Edan Lepucki of the Millions, and Square Books’ Richard Howarth discussed their favorite titles of 2013. Check out the audio here. —S.O.S.

Life Sentence

INTERVIEWER

You’ve said you can’t bear to have a bad sentence in front of you.

HEMPEL

Yes. I still can’t. Makes me ill.

—Amy Hempel, the Art of Fiction No. 176

Interviewing Dame Iris

Photography credit Nancy Crampton.

The other day we shared recordings of Garrison Keillor, William Styron, and Iris Murdoch as part of an ongoing collaboration with 92Y’s Unterberg Poetry Center. Since 1985, the Poetry Center and The Paris Review have copresented an occasional series of onstage conversations—many of which have ended up as part of our published Writers-at-Work interviews—and we’ll be sharing more of these recordings in the months to come. Meanwhile, here is James Atlas on what it was like to interview Iris Murdoch on February 22, 1990. This essay is also part of 75 at 75, a special project for the Poetry Center’s seventy-fifth anniversary that invites contemporary authors to listen to a recording from the Poetry Center’s archive and write a personal response.

I have known three charismatic writers in my life: Philip Roth, Robert Lowell, and Iris Murdoch. (A fourth, Saul Bellow, was what might be called anticharismatic, by his own choice; he didn’t mind attention, but he liked to keep his self to himself.) And there is one venue that I would describe as charismatic if an auditorium can be defined that way: the 92nd Street Y. Every major writer in the English-speaking (or I should say -writing) world has spoken there. I myself have seen—and, more importantly, heard—Joseph Brodsky, Joyce Carol Oates, John Irving, Gore Vidal, Bellow (on several occasions), and many others I can’t remember. So when I was invited to interview Dame Iris on the occasion of a visit in the winter of 1990, it wasn’t exactly a hard sell. In fact, it would turn out to be one of the great literary experiences of my own life.

I use her title with great reluctance because I did know Iris Murdoch, having spent time with her in Oxford a few years earlier for a Vanity Fair profile. This was no doubt the reason why the Y had thought of me in the first place for a live Writers-at-Work interview cosponsored by The Paris Review. As famous as she was, Murdoch did not have a large following in America, and there may have been a limited pool of interlocutors capable of introducing her before the kind of sophisticated New York audience that tended to show up at the Y.

She was a gentle soul, soft-spoken, and almost willfully self-effacing. When I first met her at Oxford, at a friend’s Sunday brunch, she had grilled me about my own life—my family, my children, my education, books written, books not written, before she had even figured out that I was the man from America who had come all that way to interview her. I was nervous about the very public forum of the Y anyway; how was I supposed to sit there on stage in front of nine hundred people and ask—for instance—about her forbidding work of philosophy, Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals? I hit upon a rather craven solution: “I’m just going to ask you one question, Iris, and then you speak for an hour.”

As I listen to this recording now, I discover with relief that she was anything but forbidding. She was modest. When I asked her what she thought she had achieved—remember, she was over seventy at this point and had long been considered one of the most important writers in England—she answered, with complete sincerity, “I haven’t achieved anything yet.” She was profound without sounding that way, or, I suspect, even knowing that she was: “Live in the present. It’s what you think you can do next that matters.” And she was funny: “The thing about the theater is, why do people stay there? Why don’t they just get up and go?” But the most valuable thing I learned from Dame Iris Murdoch that evening was about the relationship between art and humility. “One is always discontented with what one has done,” she said. “One always hopes to do better.” To be satisfied with one’s work was to misunderstand the very nature of creativity.

Toward the end of our hour, she gave the audience—or was it just me this was intended for?—a piece of advice: “It’s a good idea to know about something.” “I’ll keep that I mind,” I quipped. There was laughter in the auditorium, and I realize now that knowing about Iris Murdoch—even the little I knew—had been a good idea.

James Atlas is the founding editor of the Lipper/Viking Penguin Lives Series. A longtime contributor to The New Yorker, he was an editor at The New York Times Magazine for many years. His work has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, The London Review of Books, Vanity Fair, and many other journals. He is the author of Delmore Schwartz: The Life of an American Poet, which was nominated for the National Book Award.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers