The Paris Review's Blog, page 755

December 13, 2013

Animating the Diary, and Other News

“Elmore was the coolest guy I knew,” says Leonard’s son Peter.

The Diary of Anne Frank is being turned into an animated film for children.

The tenth annual Tournament of Books longlist!

Margaret Wrinkle is the winner of the Center for Fiction’s 2013 Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize, for Wash.

December 12, 2013

“Something Has Brought Me Here”

For years now, whenever I read a novel, narrative has been impressing itself more and more visually in my mind. Or maybe it’s that my mind has gone more and more toward these fictional visions. Even though I’m a writer, it’s not always language I’m drawn to. When I start writing a new story, I often begin with setting. Before plot, before dialogue, before anything else, I begin to see where a story will take place, and then I hear the narrative voice, which means that character is not far behind. Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about landscape painting and literature, and perhaps as an extension of this I have started to think through the idea of character and landscape as similar things, or at least as intimates, codependent.

In I Await the Devil’s Coming, Mary MacLane writes, “We three go out on the sand and barrenness: my wooden heart, my good young woman’s-body, my soul … this sand and barrenness forms the setting for the personality of me.” This is a gentle Mary MacLane, not a caustic one, going sadly out into her Montana landscape (she would rather be in the city). Again and again. Taking the reader there too. Taking the reader to her personality. For where are we when we read Mary MacLane? We are in the three things that form her, and we are in the sand. I would like to visit MacLane’s Montana in the same way I would like to visit the wasted, spectral landscape in Paul Delvaux’s painting The Lamps (those gray, crumbling hills), partly so I might meet the female figures who haunt it—doppelgängers—except there are five of them trudging across that land.

It’s Anna Karenina that Orhan Pamuk returns to again and again in his book The Naïve and the Sentimental Novelist, as a character formed by her surroundings, as a “perfect” novel. Pamuk believes that

Anna Karenina is memorable not because of the fluctuations of her soul or the cluster of attributes we call “character,” but because of the broad, rich landscape that she is so deeply immersed in and that, in turn, reveals itself through her in all its sumptuous detail. Reading the novel, we both see the landscape through the heroine’s eyes and know that the heroine is part of the wealth of that landscape. Later on, she will be transformed into an unforgettable sign, a kind of emblem that reminds us of the landscape she is part of.

To look out of the train window while Anna looks out of it too. To see Anna as the train and the snowy landscape, or at least made of the same cloth. I think this is what excites me about narrative. Outside the body and inside the mind, a novel can be like a landscape painting with a character moving through it, all of her violences and joys playing themselves out in only this setting, only this narrative, for in another it would not be so.

In Renee Gladman’s Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge, it’s the sentence that is alive and that is also a kind of architecture or landscape. “The story wasn’t given to me as most are, as some kind of choreography beaten against the body rather it was laid on top of my voice.” I am reading Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge, not watching it, but I see this so clearly: invisible words laid on top of a voice. A kind of drawing; drawn lightly, perhaps. One thing beaten against another. We get to this image, this way of being alive, through narrative. Like we get to the territory of Mary MacLane.

Recently, while working on a short story, I kept seeing its setting in the same way its narrator sees setting in the paintings she looks at when she visits a museum. It was natural then to write them in the same way, and also that they would, in some sense, join. The narrator of this story is always gazing at landscape (in paintings) and she is always in landscape (her own). She takes pleasure in each and sometimes they give her trouble but still she seems to live in both. When she looks at the paintings, they allow her to emerge into another kind of place, even though the physical space around her hasn’t actually changed.

What does a reader do with these literary landscapes? Is it enough just to see them? Going back to The Naïve and the Sentimental Novelist reminds me that to link them creates more than an aesthetic experience, that there is something to be gained in that linking. “To go beyond the limits of our selves, to perceive everyone and everything as a great whole, to identify with as many people as possible, to see as much as possible: in this way, the novelist comes to resemble those ancient Chinese painters who climbed mountain peaks in order to capture the poetry of vast landscapes.” But also, what if you are a short story writer or a novelist interested in something other than story? What if when you look at a piece of art there is something in it you want to try in writing, because to you it seems as if a story should be able to hold something like that—hold possibilities, not exclude them.

The novel Burial by Claire Donato makes visible a world of disorientation the death of a father must bring. It’s a mind made into a place, not unlike a setting, but it’s more than that. Remarkably, this life of the mind is sometimes sensual. How is it that a death place could in any way be inviting? “It is not snowing so heavily now, though what is not seen is always meant to break. Human beings are made of ice, crystals that fall through the body, freeze until they melt, discharge, and then detach atop the ice atop the lake. The crystals are frozen. The lake is crystal. A body becomes frozen crystal at the moment of its death.” Is the body a lake? Here, they are made of the same thing. One of them falls through to the other. It is easy to see this passage of the narrative as a landscape painting, one that has the potential to be comforting, even if you think it shouldn’t.

I remember the first time I encountered the work of Bill Viola, at a retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago. I walked through the dark galleries, video installations everywhere, and it was like I was in a haunted house, large screens with their larger-than-life projections. Afterward I went home and immediately wanted to write. It’s not that I wanted to write a story about Viola’s work, or even based on it. I wanted to write to something in the work, or I wanted to reproduce in writing some quality I had seen there. More recently, someone posted a video by Viola on Facebook, I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like (1986), the one of the owl to which the camera gets closer and closer, until the cameraperson (Viola?) is reflected in the owl’s eyes. The video is very short, barely three minutes, and it is not a story, or even story-like, and yet there is something in it I’d like to do too, in a story.

What is it that happens when a narrative allows us to look at an image longer than we are “supposed” to, when it is just as interesting as the story being told? Can a performance of character rest there? I think about Anna Karenina and the train, superimposed on top of each other, all the humanity present in that image, racing through the snow; the three things that make Mary MacLane in her empty Montana sandscape; a crystal lake and a frozen body; one thing laid on top of another. Together, not separate. Relaxing into each other with their outlines intact.

Amina Cain is the author of two collections of short stories: Creature (Dorothy, a publishing project, 2013) and I Go To Some Hollow (Les Figues Press, 2009). Her writing has appeared in BOMB, Denver Quarterly, n+1, Two Serious Ladies, and other places. She lives in Los Angeles.

Drinking with the Factotum

This morning, we mentioned a new bar opening tomorrow in Los Angeles: Barkowski. Writing at LAist, Matthew Bramlett opines,

There are so many things wrong with this place that can be seen almost immediately. Barkowski looks like a bar for bougie people who claim to have read “Ham on Rye” once and go out of their way to tell everyone that it “changed their life.” It’s the bar equivalent of buying a Misfits shirt at Urban Outfitters. Also, doesn’t King Eddy already exist, and didn’t Mr. Bukowski actually patronize that place?

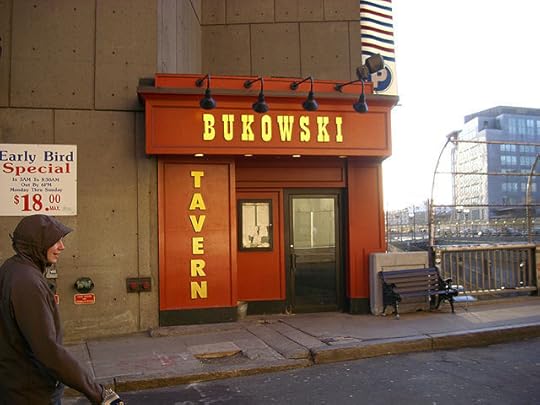

We can’t speak to the lameness of the new watering hole, but it did remind us that Bukowski-themed bars are (appropriately, or worryingly) hardly a new phenomenon, and our readers have informed us of still more.

Post Office, a whiskey bar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is named after Bukowski’s semi-autobiographical 1971 novel “dedicated to nobody.”

Cambridge, Massachusetts, boasts the fittingly divey Bukowski Tavern of Inman Square (there is also a location in Back Bay), where service is appropriately surly.

Neither of which is to be confused with Bukowski’s, in Prague, where one can smoke, probably rendering it most Bukowski-esque of all.

Chinaski’s of Glasgow seems kind of gastropub for the actual gent’s tastes, but can’t fault naming it after his longtime alter ego.

That’s five right there. Got any more?

Cecil Frances Alexander’s “Once in Royal David’s City”

Mine is not a family given to ritual. We are too chaotic, too scatter-brained, too disorganized. Because my parents’ marriage is “interfaith” (a word I have never once heard them use, and which seems to imply more faith than was in fact mingled), religious holidays were sketchy affairs and, beyond the six-foot hero that graced our Halloween open house and the Teeny-Bean jelly beans we ate at Easter, our year was not marked by a series of traditions.

The one exception was, and is, the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols at Saint Thomas, the gray stone Episcopal bastion on Fifth Avenue. It has been many years since anyone but me has agreed to accompany my mother to the service (my brother never fails to voice scorn based on a long-ago middle school soccer game against the Saint Thomas Boys’ Choir School) but maybe that is as it should be: she likes to claim that I, in fetus form, first kicked during the service. The New York iteration takes place the Sunday before Christmas, but it is of course based on the King’s College Choir service which the BBC has broadcast on Christmas Eve from Cambridge since 1928.

Lessons and Carols as we know it today—which is to say, in the King’s College mold, an alternating series of readings and corresponding carols—was created in 1918. If you are familiar with the program you know that, whatever else might be included (and there is generally some Benjamin Britten arrangement or something that causes my mother to whisper loudly, “I didn’t care for that”), the service kicks off with “Once in Royal David’s City.”

One can only imagine the status associated with being the chosen soloist. Because the first verse is only the voice of one boy soprano, ethereal and pure, echoing through the church. At Saint Thomas, as in other churches, the choir starts in the back and processes forward; the rest of the choir joins in on the second verse. On the third, the whole congregation is singing, which is always a bit of a letdown, and then by the end the organist is completely out of control and the spell is well and truly broken. At least in my experience. But that first moment, and the collective hush of shared expectation, is undeniably magical. You can feel the same magic listening to the BBC broadcast.

Mrs. Cecil Alexander, who wrote the poem “Once in Royal David’s City” in 1848, was a big deal in her day, the author not merely of this carol but “All Things Bright and Beautiful” and “There Is a Green Hill Far Away.” Anyone in Victorian England would have heard of her Hymns for Little Children. (Lyrics like “Christian children all must be / Mild, obedient, good as He” are a none-too-subtle tipoff to the didactic intention.) It must be said that, while this is a lovely carol, the final lyric has got to be amongst the most anticlimactic in the English language:

Not in that poor lowly stable,

With the oxen standing by,

We shall see Him; but in heaven,

Set at God’s right hand on high;

Where like stars His children crowned

All in white shall wait around.

After the service, my mother and I rush to La Bonne Soupe to beat the crowds and order fondue. Fellow congregants are recognizable by their programs and the occasional tie emblazoned with the seal of the Episcopal Church. For several years we ended up seated next to a table of WASPs in from Greenwich who, with the exception of one surly teenager, were all extremely jolly. Then one year he wasn’t there and we were told he had gone to West Point. That was ten years ago now.

My mother always assumed that I kicked because I was so moved by the music, which strikes me as a fairly optimistic interpretation. But next Sunday, we will go and once again know that thrill of communal longing. It is a beautiful carol, but I don’t listen to it other than during that service. Wikipedia informs us that Mrs. Alexander’s words have been recorded by, among others, Mary Chapin Carpenter, the Chieftains, Petula Clark, and Jethro Tull. I don’t imagine my mother would care for that at all.

Once in royal David’s city

Stood a lowly cattle shed,

Where a mother laid her Baby

In a manger for His bed:

Mary was that mother mild,

Jesus Christ her little Child.

He came down to earth from heaven,

Who is God and Lord of all,

And His shelter was a stable,

And His cradle was a stall;

With the poor, and mean, and lowly,

Lived on earth our Savior holy.

And through all His wondrous childhood

He would honor and obey,

Love and watch the lowly maiden,

In whose gentle arms He lay:

Christian children all must be

Mild, obedient, good as He.

For he is our childhood’s pattern;

Day by day, like us He grew;

He was little, weak and helpless,

Tears and smiles like us He knew;

And He feeleth for our sadness,

And He shareth in our gladness.

And our eyes at last shall see Him,

Through His own redeeming love;

For that Child so dear and gentle

Is our Lord in heaven above,

And He leads His children on

To the place where He is gone.

6. Not in that poor lowly stable,

With the oxen standing by,

We shall see Him; but in heaven,

Set at God’s right hand on high;

Where like stars His children crowned

All in white shall wait around.

Map of the World

I do realize it must feel like map week around here, but how could we not share this literary street map, loosely based on Victorian London? To quote the Dorothy studio, the map

is made up from the titles of over six hundred books from the history of English Literature (and a few favourites from further afield). The map includes classics such as Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, Bleak House, Vanity Fair, and Wuthering Heights as well as twentieth and twenty-first century works such as The Waste Land, To the Lighthouse, Animal Farm, Slaughterhouse 5, The Catcher in the Rye, The Wasp Factory, Norwegian Wood, and The Road.

Playing DFW, and Other News

Jason Segel will play David Foster Wallace in The End of the Tour . Jesse Eisenberg plays reporter David Lipsky.

Speaking of LA, a Charles Bukowski-themed bar is opening in Santa Monica. It is called Barkowski. (It should be noted that Brooklyn’s Post Office takes its name from a Bukowski novel, and is a good bar, so.)

The National Library of Norway plans to digitize every book in the Norwegian language.

If in New York, join Jonathan Ames, Sheila Heti, and Lawrence Weschler at the 92nd Street Y to discuss and celebrate The Best of McSweeney’s.

December 11, 2013

The Joyce Lee Method of Scientific Facial Exercises

Best of the “Best”

2013 might well be called the year of the best-of list. If you don’t have the time or energy to read through the hundreds of them, here is a handy-dandy infographic (a cheat sheet of sorts) that collects those titles most often cited by critics on said lists.

Hell on Wheels

During one of the most lucrative Thanksgiving weekends in Hollywood history, moviegoers hooked on the Hunger Games franchise once again embraced the vision of a populace preoccupied by blood sports. Millions more Americans stayed home and skirted family small talk while zoning out in the flat-screen glow of football coverage. Before NFL collisions in HD and murderous YA fiction in IMAX colonized our culture, a short story published in Esquire in 1973 anticipated the blitz on both fronts. William Harrison’s “Roller Ball Murder” forecasted a future where corporations have replaced all governments and world armies, and nationalism is exorcised at ultraviolent roller derbies. The games keep the people in line, so long as they’re tuned into what Harrison presciently dubbed “multivision.”

When I came across Harrison’s obituary in the October 30 edition of the New York Times—he passed away in Arkansas, at age seventy-nine—it was printed just below the obituary for the late Toronto Maple Leafs defenseman Allan Stanley. Seeing the two notices printed in such proximity, the name that leapt to mind was Ontario’s own Norman Jewison, a lifelong Leafs fan and the Oscar-winning director of In the Heat of the Night and Fiddler on the Roof. In 1975, Jewison adapted Harrison’s story for the screen and encouraged him to write the screenplay. The result was Rollerball, an underappreciated seventies curio that was revived briefly in the wake of a regrettable remake in 2002. The overlooked original still packs a punch.

Along with his production designer, John Box, a veteran of such classics as Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, Jewison faced the challenge of visualizing a sport that had previously resided solely in Harrison’s imagination. After months of experimentation, down to the creation of an ersatz Rollerball rulebook and a new typeface for uniforms and related regalia, Jewison’s crew managed to bring the game to life. The stadium, which was anchored by a massive, hardwood oval track, was modeled after architectural remnants from the Munich Olympics, an international competition haunted by terrorist infiltration. The Rollerball game itself, as depicted in the screen adaptation (there are slight modifications from the original story), revolves around brawlers decked out in spiked leather gloves who dodge gasoline fires and crashed motorcycles along the racetrack, all while protecting a steel ball and avoiding James Caan’s pterodactyl shoulders. Presiding over the carnage is the dispassionate CEO of ENERGY, the Houston-based behemoth at the center of the story, portrayed by the great John Houseman—an owl with skybox seats.

Though Jewison instantly recognized the cinematic potential of Harrison’s piece in Esquire, it was his experience as a hockey spectator that solidified his vision. “Around the time I read Bill’s story, I went to a hockey game at Chicago Stadium,” he told me over the phone last month. “It was a violent game, one filled with passion. All of a sudden, one of the players was hit and there was blood on the ice. The red blood against the white ice was so dramatic and compelling. The audience went crazy, like they were being fed by the violence. At that moment, I noticed all the police walked to the bottom of the aisle to keep watch.”

For Harrison, the impetus of the story was the belligerence he’d noticed taking place at international soccer matches, both on the field and off. As a Canadian, ice hockey was naturally Jewison’s analogue. “Hockey is probably one of the most violent games we have,” he said. “It used to be a game based on skill and wonderful skating, almost balletic, and now it’s based on violence. And it’s the same with American football.”

True to form, the NFL Roundup column in the November 19 Times, published the morning after Jewison and I spoke, read like Rollerball outtakes: a player suspended for ripping an opponent’s helmet off and head-butting him; league-appointed lawyers questioning the entire Miami Dolphins team to root out internal locker-room threats; charges being leveled against an unruly fan who slid from the third deck of Ralph Wilson Stadium in Buffalo and landed on an unsuspecting man below; a former linebacker crashing into an oncoming car on an Oakland highway while driving a hundred miles per hour, killing them both.

As potent as Jewison’s critique of competitive sports remains, it was not his primary target. “I was more interested in the political aspect of Rollerball,” he explained, adding that he bristled when a sportswriter at a major New York daily newspaper was assigned to review Rollerball upon its release instead of the resident film or culture critic. “I was interested in how political systems had failed—communism had failed, democracy had failed—and the world was taken over by corporate entities. The assumption was multinationals could solve all problems. So Bill and I broke down what society really needs—solvent energy sources, food, water—and we divided those needs into corporations. Each would have a Rollerball team, and that’s where the violent urges of the populace would be expelled.”

For all its thrilling depictions of centrifugal battle, where motorcycle stuntmen risked life and limb (only one was significantly injured during production, a broken leg—“Poor Brubaker,” Jewison winced), the most lasting images in the film unfold during a black-tie after-party, in which the rollerballers and their hangers-on pop pills and scroll through highlights of their most crushing body checks on wall-sized screens. “I had this feeling that privilege was given to the athletes, like in the days of Rome,” Jewison said. “Whether it’s Circus Maximus or the Stanley Cup, they’re like gladiators leaving the arena. The players are so exalted for their skill and for surviving. So we decided, well, there’s this kind of class society,” where the players enjoy the spoils of celebrity.

At the climax of the party, women in evening gowns slip away from the confines of the hillside palace and shoot trees with lasers at dawn, giggling and gritting their teeth as the trunks smolder. While laser blasts are the most sci-fi addition to Harrison’s original story, the situation feels vaguely plausible. Watching the scene again recently, I was reminded of the Australian tycoon fined by Canadian authorities last year for driving his yacht through the Northwest Passage during an alcohol-fueled party and allowing guests to hop off the boat and taunt native wildlife. According to the National Post, the drunken interlopers took photographs alongside muskox “in mock disco poses” while passengers on the deck shot paintballs and illegal fireworks into the pristine waters of the high Arctic.

And with the eyelash-singeing pyrotechnics of the Super Bowl only intensifying, I’m not sure I’d flinch if this year’s half-time show featured laser-assisted deforestation. Similarly, a debate has sparked regarding the location of the festivities, which will be centered at the taxpayer-funded MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey. Expecting a boon to the local economy, due in large part to the pageantry and nightlife surrounding the big game, townspeople and business owners in neighboring communities have objected to the sheer number of glitzy parties being hosted across the river, in the chic corridors of Manhattan. When the warriors and their charged-up fans tire of the velvet ropes that night, perhaps some will drift across the bridge to small-town New Jersey and torch the Pine Barrens. The nearby ticker-tape celebration could hide the evidence.

James Hughes is a writer and editor in Chicago.

Jane Austen Sells, and Other News

A portrait of Jane Austen—you know, the portrait, based on her sister’s sketch—has sold at auction for £135,000, which is actually somewhat below the estimate.

“I started to write books in 1982 because I thought I was everywoman,” (all evidence to the contrary) Martha Stewart says at Art Basel.

“Colin Wilson, the writer, who has died at eighty-two, suspected he was a genius; and there were some who agreed with him when in 1956, aged twenty-four, he published The Outsider, a somewhat portentous overview of existentialism and alienation.” Because no one does an obit like the Brits.

John Waters on Christmas shopping: “I always give books. And I always ask for books. I think you should reward people sexually for getting you books. Don’t send a thank-you note, repay them with sexual activity. If the book is rare or by your favorite author or one you didn’t know about, reward them with the most perverted sex act you can think of. Otherwise, you can just make out.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers