Louis Arata's Blog, page 8

July 25, 2017

New Orleans Writers' Residency

What is the one thing that writers crave the most? Time to work on their writing.

What is the one thing that writers crave the most? Time to work on their writing.A quick search on Poets & Writers website pulled up a list of 83 residencies: Yaddo, James Merrill, Kenyon Review, as wells as retreats that also focus on yoga, ecology, and visual arts. You can travel to Colorado, California, Wisconsin, Mexico, Frances, Ireland and Germany.

This month, I have been lucky enough to be selected as one of six writers in the inaugural New Orleans Writers’ Residency, from July 10 to August 8. The founders of the residency are Katherine Elliott, Shawn Drost, and Tim Raveling. You can read about them here: New Orleans Writers Residency

Over the last three years, they have been renovating a shotgun house, with one side devoted to the residency. In case you’re wondering, a shotgun house features a connected series of rooms that open onto one another without the benefit of a corridor. In other words, you walk directly from the living room into the library into the bedroom into the kitchen.

Over the last three years, they have been renovating a shotgun house, with one side devoted to the residency. In case you’re wondering, a shotgun house features a connected series of rooms that open onto one another without the benefit of a corridor. In other words, you walk directly from the living room into the library into the bedroom into the kitchen.  They have done up the house beautifully, with walls of dark green or red, exposed brick, antique plumbing fixtures, and restored hardwood floors. The writers live dormitory style and share common rooms. In the front of the house is the writing room, which contains four antique desks and a long table. It didn’t take long for the six writers to claim a space and make it their own.

They have done up the house beautifully, with walls of dark green or red, exposed brick, antique plumbing fixtures, and restored hardwood floors. The writers live dormitory style and share common rooms. In the front of the house is the writing room, which contains four antique desks and a long table. It didn’t take long for the six writers to claim a space and make it their own.

The greatest benefit, of course, is the opportunity to write. Days are generally unstructured, though the resident hosts Kat and Tim have scheduled several fun outings, including a swamp tour, a ghost tour, and a literary pub crawl. Each morning they provide an ample continental breakfast, and a few times Kat has spoiled us with gourmet dinners (e.g., rack of lamb, blackberry compote, and scalloped potatoes; homemade ravioli, squab – we’re not hurting for good food).

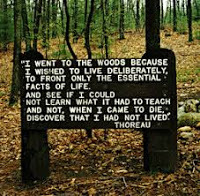

The greatest benefit, of course, is the opportunity to write. Days are generally unstructured, though the resident hosts Kat and Tim have scheduled several fun outings, including a swamp tour, a ghost tour, and a literary pub crawl. Each morning they provide an ample continental breakfast, and a few times Kat has spoiled us with gourmet dinners (e.g., rack of lamb, blackberry compote, and scalloped potatoes; homemade ravioli, squab – we’re not hurting for good food).My project for the four weeks is to work on the first draft of Walled In, a modern-day comic take on Thoreau’s Walden. In the first two weeks, I have written a first draft of chapters one through five, and today I started on chapter six. Also, I have been busy reading Walden (I’ve lost track of how many times), The Thoreau You Don’t Know by Robert Sullivan, and Walden Pond: A History by W. Barksdale Maynard.

When I’m not busy writing, I’m exploring New Orleans, which deserves several posts of its own. Stay tuned.

Published on July 25, 2017 15:34

July 17, 2017

Reading Slowly

Recently I was juggling four books at once: How Green Was My Valley, The King in Yellow, Leverage, and Being Henry David.

While all of them were engaging, I found myself taking my time reading them. Particularly Valley, which I had read twenty years ago. Coming back to Richard Llewellyn’s novel, I had the same experience as the first time. I was fascinated by the lyrical cadence of the Welsh language which needed to seep into my thoughts. It was not a novel I could plow through quickly, no matter how hard I tried.

While all of them were engaging, I found myself taking my time reading them. Particularly Valley, which I had read twenty years ago. Coming back to Richard Llewellyn’s novel, I had the same experience as the first time. I was fascinated by the lyrical cadence of the Welsh language which needed to seep into my thoughts. It was not a novel I could plow through quickly, no matter how hard I tried.

The other three novels also languished on my bedside table (that’s not actually true. All of them were e-books, so they were languishing on my iPhone). Still, in each case, I would read a chapter or two, set it aside as I picked up the next, and over many weeks, I cycled through the stories.

The other three novels also languished on my bedside table (that’s not actually true. All of them were e-books, so they were languishing on my iPhone). Still, in each case, I would read a chapter or two, set it aside as I picked up the next, and over many weeks, I cycled through the stories.

Since I set myself the task of reading 50 books a year, I tend to stay focused on my reading. Yet, every year I hit a stretch where it takes me longer than expected to get through a book. Rarely is the book boring or slow-going; I’m simply not in the mood to read more quickly.

The benefit to reading slowly is that the stories sink into deep pools, until they permeate the subconscious. When I was away from the novels, I found myself thinking about Huw or Henry, Kurt or Danny, or the collection of artists/painters who inhabit the surreal world of The King in Yellow. I wound up building a relationship with these characters, thinking about the trajectory of their lives, praying that events would turn out fine. Honestly, I worried about them, particularly in Leverage which kept escalating the tension until the very end.

As a result, reading slowly allows a deep form of engagement. When I read a book quickly, I certainly get immersed in the experience, but it’s different. Maybe fast reading is like Twitter, getting you right to the point of the story, and slow reading is like handwritten correspondence, like something Jane Austen might write.

Taking your time has its benefits.

While all of them were engaging, I found myself taking my time reading them. Particularly Valley, which I had read twenty years ago. Coming back to Richard Llewellyn’s novel, I had the same experience as the first time. I was fascinated by the lyrical cadence of the Welsh language which needed to seep into my thoughts. It was not a novel I could plow through quickly, no matter how hard I tried.

While all of them were engaging, I found myself taking my time reading them. Particularly Valley, which I had read twenty years ago. Coming back to Richard Llewellyn’s novel, I had the same experience as the first time. I was fascinated by the lyrical cadence of the Welsh language which needed to seep into my thoughts. It was not a novel I could plow through quickly, no matter how hard I tried. The other three novels also languished on my bedside table (that’s not actually true. All of them were e-books, so they were languishing on my iPhone). Still, in each case, I would read a chapter or two, set it aside as I picked up the next, and over many weeks, I cycled through the stories.

The other three novels also languished on my bedside table (that’s not actually true. All of them were e-books, so they were languishing on my iPhone). Still, in each case, I would read a chapter or two, set it aside as I picked up the next, and over many weeks, I cycled through the stories.Since I set myself the task of reading 50 books a year, I tend to stay focused on my reading. Yet, every year I hit a stretch where it takes me longer than expected to get through a book. Rarely is the book boring or slow-going; I’m simply not in the mood to read more quickly.

The benefit to reading slowly is that the stories sink into deep pools, until they permeate the subconscious. When I was away from the novels, I found myself thinking about Huw or Henry, Kurt or Danny, or the collection of artists/painters who inhabit the surreal world of The King in Yellow. I wound up building a relationship with these characters, thinking about the trajectory of their lives, praying that events would turn out fine. Honestly, I worried about them, particularly in Leverage which kept escalating the tension until the very end.

As a result, reading slowly allows a deep form of engagement. When I read a book quickly, I certainly get immersed in the experience, but it’s different. Maybe fast reading is like Twitter, getting you right to the point of the story, and slow reading is like handwritten correspondence, like something Jane Austen might write.

Taking your time has its benefits.

Published on July 17, 2017 17:02

May 18, 2017

Book Review: Philomena

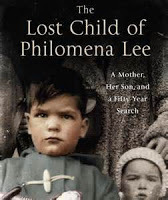

Marketing really interfered with my enjoyment of Martin Sixsmith’s Philomena.

About a month ago, I’d watched the movie version, starring Judi Dench and Steve Coogan. The story follows Philomena Lee on her search for the son she had given up for adoption. In 1950s Ireland, the Catholic Church wielded immense political power over the lives of women and their children born out of wedlock. For years, the Church effectively sold the children to American couples, and the birth mothers were forced to surrender their rights to ever having contact with their children.

The movie was a poignant and funny road movie that takes Philomena and the journalist Martin Sixsmith to America, where they discover the fate of her son, Anthony, who has been raised as Michael Hess.

After seeing the movie, I decided to read Sixsmith’s book, which focuses on the son, Michael Hess, rather than Philomena. It follows his adoption by Margie and Doc Hess and how he grows up looking for a sense of belonging in the world. As an orphan, he feels displaced and at odds with his new family. At first, he endeavors to fit in as the good child, but then as he gains his independence, he is soon at war with his controlling father. Later, in college, he learns how to embrace his homosexuality. After graduation, he ends up working for the Republican Party – ideologically different than his own liberal viewpoints. Michael is forced to straddle two worlds – the GOP and gay culture – never at ease in either one.

Or maybe it

Or maybe it

was this one This is the

This is the

version I readNow, I’m used to books and movies telling different stories, but in this case I kept expecting Philomena to have more prominence, given that it is her name in the title, Philomena: A Mother, Her Son, and a Fifty-Year Search. I eventually discovered that the book was originally The Lost Child of Philomena Lee: A Mother, Her Son, and a Fifty Year Search, which is a marginally more accurate representation of the story within. In reissuing the book as part of the movie tie-in, the marketers no doubt wanted to emphasize Philomena over Michael. They even had Judi Dench write the introduction.

But given that Philomena’s name is part of the title, it raises the expectation that she will play a significant role.

That aside, I still came away from the book with a sense of disappointment and frustration. Sixsmith’s book purports to be nonfiction, but it lacks the objective viewpoint of journalism. Rather, it indulges in scenes and dialogue that feel fabricated. While Sixsmith apparently interviewed Michael’s friends and business associates, he elects to present the story as though it were a novel. And not a terribly well written novel, at that.

Dialogue is contrived. Scenes are formulaic. I kept asking myself how does the author know this was what was said. Is he taking dramatic license? If so, doesn’t that undermine the veracity of the story? I can handle speculation about what occurred if the writer is upfront about it, but when it is presented as fact, I end up suspicious of everything. Sixsmith and Philomena,

Sixsmith and Philomena,

Coogan and Dench.

You decideIt doesn’t help Sixsmith’s case that Susan Kavanagh, who knew Michael and was interviewed by Sixsmith, has publicly stated that the book should be categorized as fiction. In her GoodReads review, Kavanagh writes:

No doubt, the movie is fictional as well, but it is more upfront about it. It is not presented as a documentary, so I can accept that this is an interpretation of the story. That isn’t the case with the book.

In the end, I have to choose the movie over the book as the more entertaining of the two.

About a month ago, I’d watched the movie version, starring Judi Dench and Steve Coogan. The story follows Philomena Lee on her search for the son she had given up for adoption. In 1950s Ireland, the Catholic Church wielded immense political power over the lives of women and their children born out of wedlock. For years, the Church effectively sold the children to American couples, and the birth mothers were forced to surrender their rights to ever having contact with their children.

The movie was a poignant and funny road movie that takes Philomena and the journalist Martin Sixsmith to America, where they discover the fate of her son, Anthony, who has been raised as Michael Hess.

After seeing the movie, I decided to read Sixsmith’s book, which focuses on the son, Michael Hess, rather than Philomena. It follows his adoption by Margie and Doc Hess and how he grows up looking for a sense of belonging in the world. As an orphan, he feels displaced and at odds with his new family. At first, he endeavors to fit in as the good child, but then as he gains his independence, he is soon at war with his controlling father. Later, in college, he learns how to embrace his homosexuality. After graduation, he ends up working for the Republican Party – ideologically different than his own liberal viewpoints. Michael is forced to straddle two worlds – the GOP and gay culture – never at ease in either one.

Or maybe it

Or maybe itwas this one

This is the

This is theversion I readNow, I’m used to books and movies telling different stories, but in this case I kept expecting Philomena to have more prominence, given that it is her name in the title, Philomena: A Mother, Her Son, and a Fifty-Year Search. I eventually discovered that the book was originally The Lost Child of Philomena Lee: A Mother, Her Son, and a Fifty Year Search, which is a marginally more accurate representation of the story within. In reissuing the book as part of the movie tie-in, the marketers no doubt wanted to emphasize Philomena over Michael. They even had Judi Dench write the introduction.

But given that Philomena’s name is part of the title, it raises the expectation that she will play a significant role.

That aside, I still came away from the book with a sense of disappointment and frustration. Sixsmith’s book purports to be nonfiction, but it lacks the objective viewpoint of journalism. Rather, it indulges in scenes and dialogue that feel fabricated. While Sixsmith apparently interviewed Michael’s friends and business associates, he elects to present the story as though it were a novel. And not a terribly well written novel, at that.

Dialogue is contrived. Scenes are formulaic. I kept asking myself how does the author know this was what was said. Is he taking dramatic license? If so, doesn’t that undermine the veracity of the story? I can handle speculation about what occurred if the writer is upfront about it, but when it is presented as fact, I end up suspicious of everything.

Sixsmith and Philomena,

Sixsmith and Philomena,Coogan and Dench.

You decideIt doesn’t help Sixsmith’s case that Susan Kavanagh, who knew Michael and was interviewed by Sixsmith, has publicly stated that the book should be categorized as fiction. In her GoodReads review, Kavanagh writes:

“… I cringed when I read my ‘character’ engaging in fictional dialogue with Michael. Things only went downhill from there. The dialogue that Sixsmith invented for the conversations Michael and I supposedly had were not quotes from the interview I gave, and I did not agree to my interview being turned into scenes with made-up dialogue.”

No doubt, the movie is fictional as well, but it is more upfront about it. It is not presented as a documentary, so I can accept that this is an interpretation of the story. That isn’t the case with the book.

In the end, I have to choose the movie over the book as the more entertaining of the two.

Published on May 18, 2017 08:01

May 15, 2017

Book Review: Ombria in Shadow

There are two worlds as close together as the reflection in a mirror: the present world we live in, and underneath that, a mere sidestep away, an enchanted place fraught with power and mystery. And those who can straddle the two worlds eventually discover how emotions can cause them to converge.

In Ombria in Shadow, Patricia A. McKillip sculpts a declining city overcome by grief at the loss of its prince. The city seems to be sinking into its own shadow. Political machinations come into play as Domina Pearl, a mysterious woman as ancient as history, sets herself as regent to the heir, Kyel. She wields cunning authority over the royal house with no intention of ever relinquishing her power over the throne.

In Ombria in Shadow, Patricia A. McKillip sculpts a declining city overcome by grief at the loss of its prince. The city seems to be sinking into its own shadow. Political machinations come into play as Domina Pearl, a mysterious woman as ancient as history, sets herself as regent to the heir, Kyel. She wields cunning authority over the royal house with no intention of ever relinquishing her power over the throne.

Those that oppose her are Ducon, a bastard nephew of the dead prince, and Lydea, the prince’s mistress. Ducon has no political aspirations; he would rather be an artist, but soon he is being pushed by nobles to oppose Domina and to seize the throne. Lydea, who has been banished from the castle by Domina, fears for the safety of the young Prince Kyel and contrives a way to return to him in disguise.

In the shadow world beneath Ombria there lives a sorceress, Faey, who literally hides her face behind the mask of other faces. She brews potions for those above, sometimes supplying both sides of a conflict. She has no apparent loyalty to anyone or anything, except (as she discovers) her apprentice, Mag, a foundling.

McKillip excels at creating worlds that have tangled histories. Her characters often sense that another existence presses up against their own, and through legends, stories, and riddles, they come to know of the shadow realms.

McKillip’s prose is lyrical and subtle, reading like a fairytale or at times a gothic novel, but at the center of everything is the emotional discovery of her characters. The world is a physical manifestation of the uncertainty and change that evolves within us. Her characters go on quests to uncover the riddles of the past, only to discover that the truth is more complex than they anticipated.

McKillip’s prose is lyrical and subtle, reading like a fairytale or at times a gothic novel, but at the center of everything is the emotional discovery of her characters. The world is a physical manifestation of the uncertainty and change that evolves within us. Her characters go on quests to uncover the riddles of the past, only to discover that the truth is more complex than they anticipated.

I am a huge fan of McKillip. Her Riddlemaster of Hed trilogy is my favorite fantasy series, and her Forgotten Beasts of Eld fascinates me. Her more recent work sometimes can be a bit more challenging in the way that she wields her prose. I have had to read the language carefully to determine if what is happening is literal or symbolic. And to read slowly is not necessarily a bad thing. It keeps me in touch with the beauty of her language and the mysteries that lie underneath the meaning of words. This, of course, suggests to me that language is the portal between the present world and the shadow world underneath – the meaning of words is the magic that transport us from our world to the other realm, one step away.

In Ombria in Shadow, Patricia A. McKillip sculpts a declining city overcome by grief at the loss of its prince. The city seems to be sinking into its own shadow. Political machinations come into play as Domina Pearl, a mysterious woman as ancient as history, sets herself as regent to the heir, Kyel. She wields cunning authority over the royal house with no intention of ever relinquishing her power over the throne.

In Ombria in Shadow, Patricia A. McKillip sculpts a declining city overcome by grief at the loss of its prince. The city seems to be sinking into its own shadow. Political machinations come into play as Domina Pearl, a mysterious woman as ancient as history, sets herself as regent to the heir, Kyel. She wields cunning authority over the royal house with no intention of ever relinquishing her power over the throne.Those that oppose her are Ducon, a bastard nephew of the dead prince, and Lydea, the prince’s mistress. Ducon has no political aspirations; he would rather be an artist, but soon he is being pushed by nobles to oppose Domina and to seize the throne. Lydea, who has been banished from the castle by Domina, fears for the safety of the young Prince Kyel and contrives a way to return to him in disguise.

In the shadow world beneath Ombria there lives a sorceress, Faey, who literally hides her face behind the mask of other faces. She brews potions for those above, sometimes supplying both sides of a conflict. She has no apparent loyalty to anyone or anything, except (as she discovers) her apprentice, Mag, a foundling.

McKillip excels at creating worlds that have tangled histories. Her characters often sense that another existence presses up against their own, and through legends, stories, and riddles, they come to know of the shadow realms.

McKillip’s prose is lyrical and subtle, reading like a fairytale or at times a gothic novel, but at the center of everything is the emotional discovery of her characters. The world is a physical manifestation of the uncertainty and change that evolves within us. Her characters go on quests to uncover the riddles of the past, only to discover that the truth is more complex than they anticipated.

McKillip’s prose is lyrical and subtle, reading like a fairytale or at times a gothic novel, but at the center of everything is the emotional discovery of her characters. The world is a physical manifestation of the uncertainty and change that evolves within us. Her characters go on quests to uncover the riddles of the past, only to discover that the truth is more complex than they anticipated. I am a huge fan of McKillip. Her Riddlemaster of Hed trilogy is my favorite fantasy series, and her Forgotten Beasts of Eld fascinates me. Her more recent work sometimes can be a bit more challenging in the way that she wields her prose. I have had to read the language carefully to determine if what is happening is literal or symbolic. And to read slowly is not necessarily a bad thing. It keeps me in touch with the beauty of her language and the mysteries that lie underneath the meaning of words. This, of course, suggests to me that language is the portal between the present world and the shadow world underneath – the meaning of words is the magic that transport us from our world to the other realm, one step away.

Published on May 15, 2017 06:53

March 14, 2017

Book Review: Inside Inside

James Lipton certainly has lived a colorful life: actor, lyricist, writer, producer (both Broadway and TV), choreographer, and pimp. Yes, pimp.

In Inside “Inside”, Lipton blends personal memoir with professional anecdotes to relate a life rich with experience. By focusing on the development of his signature show, Inside the Actors Studio, he relates the history of the Stanislavski method of acting and how it has nurtured the talents of many of our most famous actors, directors, dancers, and singers. When I started reading Inside, I knew absolutely nothing of Lipton’s past, so it came as quite a surprise that this apparently staid gentleman has had such a varied career. With his trim beard and cerebral brow, he looks like the last person to be securing clients for French prostitutes, but evidently in his younger days, that is exactly what he did.

In Inside “Inside”, Lipton blends personal memoir with professional anecdotes to relate a life rich with experience. By focusing on the development of his signature show, Inside the Actors Studio, he relates the history of the Stanislavski method of acting and how it has nurtured the talents of many of our most famous actors, directors, dancers, and singers. When I started reading Inside, I knew absolutely nothing of Lipton’s past, so it came as quite a surprise that this apparently staid gentleman has had such a varied career. With his trim beard and cerebral brow, he looks like the last person to be securing clients for French prostitutes, but evidently in his younger days, that is exactly what he did.

There is also his early acting days when he bounced from acting class to ballet class to live radio (on The Lone Ranger).

Actor, writer, producer, raconteurThen there are the Broadway days, adapting The Man Who Came to Dinnerinto a musical, which apparently showed much promise, but had an unfortunately abbreviated run due to personal tragedy in the lead actor’s life. It wasn’t until decades later that the musical was performed as it was originally written.

Actor, writer, producer, raconteurThen there are the Broadway days, adapting The Man Who Came to Dinnerinto a musical, which apparently showed much promise, but had an unfortunately abbreviated run due to personal tragedy in the lead actor’s life. It wasn’t until decades later that the musical was performed as it was originally written.

Then in the 1970s and 80s, he plunged into TV producing, including the first broadcast of the presidential inauguration celebration for Jimmy Carter. That led to many years producing Bob Hope specials.

Then there is his involvement with The Actors Studio, helping to create a degree program for actors, writers, and directors. From there he launched Inside the Actors Studio on the Bravo network to feature interviews with famous alumni of the Studio, along with other performers. Apparently the show has so much clout that it has influenced Oscar nominations and wins.

So, Lipton’s memoir is packed full of curious episodes, but what holds it together is the thread of the Actors Studio. He weaves together themes of talent, personal history, and professionalism, not only his own but that of his many guests. He lovingly writes of each guest, sharing periodic anecdotes to illustrate his point about talent and craft.

Overall, the memoir is entertaining, but at times his erudite language could use a bit of pruning. A little judicious editing could have corrected some of the hyperbole (e.g., every actor who appeared on Inside seems to have been a professional coup). Also, at times it seemed as though Lipton was single-handedly responsible for every great advancement in each project. Certainly, he holds up many, many people as his heroes – he wouldn’t be where he is without them – yet frequently he relates running into a snag of a problem then picking up a phone and calling in a favor from some important personage, and everything gets resolved. How much clout does he actually have?

Evidently, a lot. Despite his low-key intellectualism, he is a high-powered player. I’ve learned that appearances can be very deceiving.

In Inside “Inside”, Lipton blends personal memoir with professional anecdotes to relate a life rich with experience. By focusing on the development of his signature show, Inside the Actors Studio, he relates the history of the Stanislavski method of acting and how it has nurtured the talents of many of our most famous actors, directors, dancers, and singers. When I started reading Inside, I knew absolutely nothing of Lipton’s past, so it came as quite a surprise that this apparently staid gentleman has had such a varied career. With his trim beard and cerebral brow, he looks like the last person to be securing clients for French prostitutes, but evidently in his younger days, that is exactly what he did.

In Inside “Inside”, Lipton blends personal memoir with professional anecdotes to relate a life rich with experience. By focusing on the development of his signature show, Inside the Actors Studio, he relates the history of the Stanislavski method of acting and how it has nurtured the talents of many of our most famous actors, directors, dancers, and singers. When I started reading Inside, I knew absolutely nothing of Lipton’s past, so it came as quite a surprise that this apparently staid gentleman has had such a varied career. With his trim beard and cerebral brow, he looks like the last person to be securing clients for French prostitutes, but evidently in his younger days, that is exactly what he did. There is also his early acting days when he bounced from acting class to ballet class to live radio (on The Lone Ranger).

Actor, writer, producer, raconteurThen there are the Broadway days, adapting The Man Who Came to Dinnerinto a musical, which apparently showed much promise, but had an unfortunately abbreviated run due to personal tragedy in the lead actor’s life. It wasn’t until decades later that the musical was performed as it was originally written.

Actor, writer, producer, raconteurThen there are the Broadway days, adapting The Man Who Came to Dinnerinto a musical, which apparently showed much promise, but had an unfortunately abbreviated run due to personal tragedy in the lead actor’s life. It wasn’t until decades later that the musical was performed as it was originally written.Then in the 1970s and 80s, he plunged into TV producing, including the first broadcast of the presidential inauguration celebration for Jimmy Carter. That led to many years producing Bob Hope specials.

Then there is his involvement with The Actors Studio, helping to create a degree program for actors, writers, and directors. From there he launched Inside the Actors Studio on the Bravo network to feature interviews with famous alumni of the Studio, along with other performers. Apparently the show has so much clout that it has influenced Oscar nominations and wins.

So, Lipton’s memoir is packed full of curious episodes, but what holds it together is the thread of the Actors Studio. He weaves together themes of talent, personal history, and professionalism, not only his own but that of his many guests. He lovingly writes of each guest, sharing periodic anecdotes to illustrate his point about talent and craft.

Overall, the memoir is entertaining, but at times his erudite language could use a bit of pruning. A little judicious editing could have corrected some of the hyperbole (e.g., every actor who appeared on Inside seems to have been a professional coup). Also, at times it seemed as though Lipton was single-handedly responsible for every great advancement in each project. Certainly, he holds up many, many people as his heroes – he wouldn’t be where he is without them – yet frequently he relates running into a snag of a problem then picking up a phone and calling in a favor from some important personage, and everything gets resolved. How much clout does he actually have?

Evidently, a lot. Despite his low-key intellectualism, he is a high-powered player. I’ve learned that appearances can be very deceiving.

Published on March 14, 2017 07:38

March 9, 2017

Book Review: Harry Potter and the Cursed Child

Evidently Harry Potter doesn’t get to take it easy after the death of Voldemort. That pesky scar is going to start hurting again. And of course, there are the cryptic nightmares …

The play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child picks up at the epilogue to The Deathly Hollows: Harry is sending his son, Albus, off for his first year at Hogwarts. Being the offspring of a famous wizard, Albus suffers the curious stares of his classmates, and as a result keeps to himself. But he’s not alone in this. Scorpius Malfoy has to live down his father’s legacy, too. So, the two boys bond over being outsiders in the wizarding world.

The play, which is divided into two parts, covers five years at Hogwarts. There are the familiar antics of the Sorting Hat, the awkward initial classes in spells, and the early attempts at broom-craft. But nothing every runs smoothly when Harry Potter is around. Soon there is evidence that someone has been manufacturing powerful time-turners. In an effort to fix the heartache of the past, Albus and Scorpius get swept up in changing how history has unfolded.

Harry – along with Ginny, Hermione, Ron, and Draco – goes after them to prevent their undoing their victory over Voldemort. Along the way, we get glimpses into multiple alternate timelines. What if Cedric Diggory hadn’t died at the end of the Triwizard Tournament? What if Hermione and Ron hadn’t gotten together? What if Voldemort had lived? What if Harry had died?

At first, it’s fun to be back in the Harry Potter world. We get to discover what the characters have been up to. There are plenty of cameos along the way: Madame Hooch, the Sorting Hat, and even the portrait of Dumbledore. In a dream sequence, we get to revisit Hagrid’s arrival in Harry’s life. And we get the poignant tension between Harry and Albus where harsh words get said.

"I just dreamt that I was a psychologist in Chicago

"I just dreamt that I was a psychologist in Chicago

who dreams he's an inn-keeper in Vermont.

And you were Suzanne Pleshette,"The script keeps events moving swiftly. Stage directions are evocatively vague, so there’s a bit of a thrill trying to imagine how magic will be portrayed. Apart from wire-work to make wizards fly, there are bookcases that attack, and a time-turner that emits a “giant whoosh of light. A smash of noise. And time stops. And then it turns over, thinks a bit, and begins spooling backwards, slow at first … And then it speeds up.” I definitely want to see how that looks.

And I’d definitely go see the play for the spectacle. But the story? Meh. It reads like fan fiction that wants to speculate on various ideas but doesn’t really advance the overall story at all. On the surface, the story poses potentially intriguing interactions, such as the fact that Harry and Draco are forced to band together to save their respective sons. But in the end, the relationship feels either gimmicky or contrived.

Also, the ubiquitous spectre of Voldemort, in my opinion, is lazy storytelling. Are there no other potential threats in the wizarding world? Do we have to keep covering the same ground? Or are fans supposed to grateful for endless reiterations of ideas already explored in the novels?

In some ways, the play’s greatest appeal may be giving actors the chance to perform their favorite characters, like an elaborate cosplay. It should be noted, however, that the two most intriguing characters of the play are Albus and Scorpius, the ones we haven’t really gotten to know yet. Maybe if the play hadn’t spent so much time trying to reimagine what has already occurred and instead have explored fresh ideas, the story would have been more compelling.

The play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child picks up at the epilogue to The Deathly Hollows: Harry is sending his son, Albus, off for his first year at Hogwarts. Being the offspring of a famous wizard, Albus suffers the curious stares of his classmates, and as a result keeps to himself. But he’s not alone in this. Scorpius Malfoy has to live down his father’s legacy, too. So, the two boys bond over being outsiders in the wizarding world.

The play, which is divided into two parts, covers five years at Hogwarts. There are the familiar antics of the Sorting Hat, the awkward initial classes in spells, and the early attempts at broom-craft. But nothing every runs smoothly when Harry Potter is around. Soon there is evidence that someone has been manufacturing powerful time-turners. In an effort to fix the heartache of the past, Albus and Scorpius get swept up in changing how history has unfolded.

Harry – along with Ginny, Hermione, Ron, and Draco – goes after them to prevent their undoing their victory over Voldemort. Along the way, we get glimpses into multiple alternate timelines. What if Cedric Diggory hadn’t died at the end of the Triwizard Tournament? What if Hermione and Ron hadn’t gotten together? What if Voldemort had lived? What if Harry had died?

At first, it’s fun to be back in the Harry Potter world. We get to discover what the characters have been up to. There are plenty of cameos along the way: Madame Hooch, the Sorting Hat, and even the portrait of Dumbledore. In a dream sequence, we get to revisit Hagrid’s arrival in Harry’s life. And we get the poignant tension between Harry and Albus where harsh words get said.

"I just dreamt that I was a psychologist in Chicago

"I just dreamt that I was a psychologist in Chicagowho dreams he's an inn-keeper in Vermont.

And you were Suzanne Pleshette,"The script keeps events moving swiftly. Stage directions are evocatively vague, so there’s a bit of a thrill trying to imagine how magic will be portrayed. Apart from wire-work to make wizards fly, there are bookcases that attack, and a time-turner that emits a “giant whoosh of light. A smash of noise. And time stops. And then it turns over, thinks a bit, and begins spooling backwards, slow at first … And then it speeds up.” I definitely want to see how that looks.

And I’d definitely go see the play for the spectacle. But the story? Meh. It reads like fan fiction that wants to speculate on various ideas but doesn’t really advance the overall story at all. On the surface, the story poses potentially intriguing interactions, such as the fact that Harry and Draco are forced to band together to save their respective sons. But in the end, the relationship feels either gimmicky or contrived.

Also, the ubiquitous spectre of Voldemort, in my opinion, is lazy storytelling. Are there no other potential threats in the wizarding world? Do we have to keep covering the same ground? Or are fans supposed to grateful for endless reiterations of ideas already explored in the novels?

In some ways, the play’s greatest appeal may be giving actors the chance to perform their favorite characters, like an elaborate cosplay. It should be noted, however, that the two most intriguing characters of the play are Albus and Scorpius, the ones we haven’t really gotten to know yet. Maybe if the play hadn’t spent so much time trying to reimagine what has already occurred and instead have explored fresh ideas, the story would have been more compelling.

Published on March 09, 2017 08:41

March 6, 2017

Book Review: A Tale of Two Cities

The very first Dickens’ novel I read was A Tale of Two Cities – high school freshman English class. The novel was handed to us with the instruction to read it. No historical context, no instruction on how to read a Victorian novel. The assumption was that the novel would impress us with what an important work it was. After all, how many novels can you quote both the first and last lines?

So, the novel definitely made an impression on me. I got that Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton, similar in appearance, are distorted reflections of one another. I got that Lucie’s sweetness saves Carton. I got that Carton performs the ultimate sacrifice to save Lucie and her family.

The problem is that, as a freshman, I didn’t understand why Dickens was so challenging to read. He has a distinctive storytelling method. No other writers really write like him. His use of language and imagery are unique.

"It was the best chocolate;

"It was the best chocolate;

it was the worst chocolate."After I graduated college, I started tackling Dickens more systematically, and eventually learned how to read him. Since then, I’ve made it through all of his novels, many of them multiple times. A Tale of Two Cities I’ve read probably four times.

But that doesn’t mean it’s one of my favorites. In fact, I think it’s the most un-Dickensian novel he ever produced. Much more historical in scope, the novel follows Darnay, Lucie, Dr Manette, and Carton through the rising storm of the French Revolution. They are decidedly small chess pieces against the vast scope of events. As a result, you really can’t cozy up to them. Even Miss Pross, whose distinctly English toughness has a mildly endearing quality, remains at arm’s length.

So, why have I read it four times? Because Dickens took such care in constructing the story. He focuses attention on the rise and crash of the Revolution. The characters are inexorably swept forward. You can’t escape your own past, nor can you avoid the trampling feet of history. But quiet acts of heroism do preserve humanity in the midst of the worst carnage.

I always thought that London and Paris are set against each other as civilization versus brutality. Yet this time around, I paid more attention to the criminal court scenes in London. If Darnay were convicted of treason, he would have been executed in no less a brutal fashion (i.e., drawn-and-quartered) than the guillotine in Paris. So, London is at least as cruel and deadly as the uprising Jacquerie of the Paris revolution. Bloodshed can occur in the most apparently civilized societies.

I will always be impressed by the craft of A Tale of Two Cities, at Dickens’ focus on the essential rise and crash of the Revolution. And that’s probably why I’ve come back to the novel multiple times, a curious desire to wrestle with the least Dickensian of novels.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times …”Certain scenes stuck in my head: the imprisoned Dr Manette quietly making a lady’s shoe. Jerry Cruncher digging in the graveyard. Miss Pross wrestling a gun out of Madam Defarge’s hands.

“It is a far, far better thing that I do than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest I go to than I have ever known.”

So, the novel definitely made an impression on me. I got that Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton, similar in appearance, are distorted reflections of one another. I got that Lucie’s sweetness saves Carton. I got that Carton performs the ultimate sacrifice to save Lucie and her family.

The problem is that, as a freshman, I didn’t understand why Dickens was so challenging to read. He has a distinctive storytelling method. No other writers really write like him. His use of language and imagery are unique.

“Monseigneur was about to take his chocolate. Monseigneur could swallow a great many things with ease, and was by some few sullen minds supposed to be rather rapidly swallowing France; but, his morning’s chocolate could not so much as get into the throat of Monseigneur, without the aid of four strong men besides the Cook.I’m sure my teacher explained Dickens’ comic style, but I probably had a lot of trouble getting my head around the imagery in this scene. Plus, since this was a classic novel, that meant it was heavy, so I didn’t dare laugh at it.

Yes. It took four men, all four ablaze with gorgeous decoration, and the Chief of them unable to exist with fewer than two gold watches in his pocket, emulative of the noble and chaste fashion set by Monseigneur, to conduct the happy chocolate to Monseigneur’s lips. One lacquey carried the chocolate-pot into the sacred presence; a second, milled and frothed the chocolate with the little instrument he bore for that function; a third, presented the favoured napkin; a fourth (he of the two gold watches), poured the chocolate out. It was impossible for Monseigneur to dispense with one of these attendants on the chocolate and hold his high place under the admiring Heavens. Deep would have been the blot upon his escutcheon if his chocolate had bene ignobly waited on by only three men; he must have died of two.”

"It was the best chocolate;

"It was the best chocolate;it was the worst chocolate."After I graduated college, I started tackling Dickens more systematically, and eventually learned how to read him. Since then, I’ve made it through all of his novels, many of them multiple times. A Tale of Two Cities I’ve read probably four times.

But that doesn’t mean it’s one of my favorites. In fact, I think it’s the most un-Dickensian novel he ever produced. Much more historical in scope, the novel follows Darnay, Lucie, Dr Manette, and Carton through the rising storm of the French Revolution. They are decidedly small chess pieces against the vast scope of events. As a result, you really can’t cozy up to them. Even Miss Pross, whose distinctly English toughness has a mildly endearing quality, remains at arm’s length.

So, why have I read it four times? Because Dickens took such care in constructing the story. He focuses attention on the rise and crash of the Revolution. The characters are inexorably swept forward. You can’t escape your own past, nor can you avoid the trampling feet of history. But quiet acts of heroism do preserve humanity in the midst of the worst carnage.

I always thought that London and Paris are set against each other as civilization versus brutality. Yet this time around, I paid more attention to the criminal court scenes in London. If Darnay were convicted of treason, he would have been executed in no less a brutal fashion (i.e., drawn-and-quartered) than the guillotine in Paris. So, London is at least as cruel and deadly as the uprising Jacquerie of the Paris revolution. Bloodshed can occur in the most apparently civilized societies.

I will always be impressed by the craft of A Tale of Two Cities, at Dickens’ focus on the essential rise and crash of the Revolution. And that’s probably why I’ve come back to the novel multiple times, a curious desire to wrestle with the least Dickensian of novels.

Published on March 06, 2017 08:19

February 28, 2017

Book Review: The Art of Racing in the Rain

In one of his columns, Dave Barry proposed a new TV show entitled Adventure Dog. It follows such exciting exploits as “Adventure Dog Wakes Up and Goes Outside”:

That’s pretty much how humans tend to view a dog’s life. Everything is big, everything is glorious, everything must be sniffed and explored and played with.

Author Garth Stein goes in a different direction with The Art of Racing in the Rain. His narrator, Enzo, is a philosophical dog, having gleaned much of his perspective from watching television. His owner, Denny, is a race car driver who models for Enzo the mental acuity required for racing, in particular that life is about being prepared for the turn beyond the next one. Also, that the body goes where the eye goes.

Author Garth Stein goes in a different direction with The Art of Racing in the Rain. His narrator, Enzo, is a philosophical dog, having gleaned much of his perspective from watching television. His owner, Denny, is a race car driver who models for Enzo the mental acuity required for racing, in particular that life is about being prepared for the turn beyond the next one. Also, that the body goes where the eye goes.

As a narrator, Enzo certainly has his dog-like qualities: he loves playing, going on walks, and being close to his family. He knows that his role is companion and caretaker, and he possesses the canine skills of picking up on emotion, tension, and interpersonal dynamics. He is even sensitive enough to detect disease. What he lacks is the ability to communicate his insights.

"A ball is fun, but

"A ball is fun, but

I want a race car!"The novel follows Denny and Eve through their relationship, the birth of their daughter, the tragedy of Eve’s illness and death, and eventually the custody battle between Denny and his in-laws for his daughter, Zoë. But it is Enzo’s perspective as a marginalized participant that teaches the lessons of how to navigate the challenges.

If Stein had limited Enzo’s intelligence to that of Adventure Dog, the novel would have been cute but it would have lacked insight. By endowing Enzo with a philosophical nature, the reader experiences a comfortable form of empathy. Life may be viewed through a dog’s perspective, yet it lifts the day-to-day events and the highs-and-lows to greater poignancy. Stein does not give in to maudlin sentimentality, but rather emphasizes the emotional connection we have with our pets. This is why we tend to anthropomorphize them; we already recognize the intelligence there.

Like a race course, the novel pretty much goes where you expect it to go, and the beginning of the novel forecasts the ending. But those are small complaints. It’s navigating the turns that unfold before us that make the race worth it.

“And now Adventure Dog is through the door, looking left, looking right, her finely honed senses absorbing every detail of the environment, every nuance and subtlety, looking for … Holy Smoke! There it is! The YARD! Right in the exact same place where it was yesterday! This is turning into an UNBELIEVABLE adventure!”

That’s pretty much how humans tend to view a dog’s life. Everything is big, everything is glorious, everything must be sniffed and explored and played with.

Author Garth Stein goes in a different direction with The Art of Racing in the Rain. His narrator, Enzo, is a philosophical dog, having gleaned much of his perspective from watching television. His owner, Denny, is a race car driver who models for Enzo the mental acuity required for racing, in particular that life is about being prepared for the turn beyond the next one. Also, that the body goes where the eye goes.

Author Garth Stein goes in a different direction with The Art of Racing in the Rain. His narrator, Enzo, is a philosophical dog, having gleaned much of his perspective from watching television. His owner, Denny, is a race car driver who models for Enzo the mental acuity required for racing, in particular that life is about being prepared for the turn beyond the next one. Also, that the body goes where the eye goes.As a narrator, Enzo certainly has his dog-like qualities: he loves playing, going on walks, and being close to his family. He knows that his role is companion and caretaker, and he possesses the canine skills of picking up on emotion, tension, and interpersonal dynamics. He is even sensitive enough to detect disease. What he lacks is the ability to communicate his insights.

"A ball is fun, but

"A ball is fun, butI want a race car!"The novel follows Denny and Eve through their relationship, the birth of their daughter, the tragedy of Eve’s illness and death, and eventually the custody battle between Denny and his in-laws for his daughter, Zoë. But it is Enzo’s perspective as a marginalized participant that teaches the lessons of how to navigate the challenges.

If Stein had limited Enzo’s intelligence to that of Adventure Dog, the novel would have been cute but it would have lacked insight. By endowing Enzo with a philosophical nature, the reader experiences a comfortable form of empathy. Life may be viewed through a dog’s perspective, yet it lifts the day-to-day events and the highs-and-lows to greater poignancy. Stein does not give in to maudlin sentimentality, but rather emphasizes the emotional connection we have with our pets. This is why we tend to anthropomorphize them; we already recognize the intelligence there.

Like a race course, the novel pretty much goes where you expect it to go, and the beginning of the novel forecasts the ending. But those are small complaints. It’s navigating the turns that unfold before us that make the race worth it.

Published on February 28, 2017 07:43

February 20, 2017

Book Review: The Testament of Mary

I’m intrigued when a novelist tackles a story from the Bible, imbuing it with the immediacy of life. Some favorites include Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ, Jose Saramago’s The Gospel According to Jesus Christ, and Philip Pullman’s The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ. A personal favorite is Sholem Asch’s Mary, which reimagines the story through the lens of parental sacrifice: Mary is Abraham to Jesus’s Isaac.

The familiar theme across these, I suppose, is a certain degree of irreverence, not for the sake of discrediting the stories of the gospels, but rather that the authors insist on tackling important intersections of faith and humanity. Faith in God is messy, even when someone holds it dear. There is the familiar arc of belief and commitment to God that is then tested in the worst possible manner, and when the hero or heroine comes out the other side, he or she is transformed (and not always in a positive manner).

The familiar theme across these, I suppose, is a certain degree of irreverence, not for the sake of discrediting the stories of the gospels, but rather that the authors insist on tackling important intersections of faith and humanity. Faith in God is messy, even when someone holds it dear. There is the familiar arc of belief and commitment to God that is then tested in the worst possible manner, and when the hero or heroine comes out the other side, he or she is transformed (and not always in a positive manner).

Colm Toibin’s The Testament of Mary makes the promise of a radical reinterpretation of Mary, the mother of Jesus. According to the jacket blurb, the novel presents “a solitary older woman still seeking to understand the events that become the narrative of the New Testament and the foundation of Christianity.”

Toibin’s Mary is an angry, bitter woman who is all but captive to two of the apostles. Living a predominantly solitary life, she is frequently visited by the apostles who want her version of Christ’s life and crucifixion. Mary will have none of it. She suspects how they intend to augment and fabricate the story and to turn it to their own purposes. Colm Toibin

Colm Toibin

For her, the life and death of her son has nothing to do with salvation. The early promise of Jesus’ faith provides Mary with her happiest memories, yet once she sees the man he becomes, she is no longer sure she recognizes him. On hearing that Roman authorities are keeping an eye on him, she pleads with him to give up his preaching. Jesus, of course, will have nothing to do with that.

The premise is intriguing, yet there are times when the language did not work for me. Toibin’s use of understatement keeps the story at arm’s length at times, as though to speak too openly about events would make them concrete. Interestingly, the piece originated as a monologue for the 2011 Dublin Theatre Festival. Hearing an actor perform the piece would probably bring some needed emotional depth to certain passages.

In an interesting reversal of patriarchal language, Mary never refers to the two apostles by name, though one is clearly John. The only characters with given names are Miriam and Mary, Lazarus, and Marcus. Even Jesus is never called by name.

The strongest section of the novel is the trial and crucifixion. Here Toibin brings anguishing energy to the prose:

While I found the work interesting, for me it's understatement left me wanting more. For all her justifiable bitterness and personal regrets, Mary doesn’t appear to reconcile herself to her actions. Maybe that’s the point: Mary is often presented as the ideal mother, and here she is having doubts and fears, like anyone might have.

The familiar theme across these, I suppose, is a certain degree of irreverence, not for the sake of discrediting the stories of the gospels, but rather that the authors insist on tackling important intersections of faith and humanity. Faith in God is messy, even when someone holds it dear. There is the familiar arc of belief and commitment to God that is then tested in the worst possible manner, and when the hero or heroine comes out the other side, he or she is transformed (and not always in a positive manner).

The familiar theme across these, I suppose, is a certain degree of irreverence, not for the sake of discrediting the stories of the gospels, but rather that the authors insist on tackling important intersections of faith and humanity. Faith in God is messy, even when someone holds it dear. There is the familiar arc of belief and commitment to God that is then tested in the worst possible manner, and when the hero or heroine comes out the other side, he or she is transformed (and not always in a positive manner).Colm Toibin’s The Testament of Mary makes the promise of a radical reinterpretation of Mary, the mother of Jesus. According to the jacket blurb, the novel presents “a solitary older woman still seeking to understand the events that become the narrative of the New Testament and the foundation of Christianity.”

Toibin’s Mary is an angry, bitter woman who is all but captive to two of the apostles. Living a predominantly solitary life, she is frequently visited by the apostles who want her version of Christ’s life and crucifixion. Mary will have none of it. She suspects how they intend to augment and fabricate the story and to turn it to their own purposes.

Colm Toibin

Colm ToibinFor her, the life and death of her son has nothing to do with salvation. The early promise of Jesus’ faith provides Mary with her happiest memories, yet once she sees the man he becomes, she is no longer sure she recognizes him. On hearing that Roman authorities are keeping an eye on him, she pleads with him to give up his preaching. Jesus, of course, will have nothing to do with that.

The premise is intriguing, yet there are times when the language did not work for me. Toibin’s use of understatement keeps the story at arm’s length at times, as though to speak too openly about events would make them concrete. Interestingly, the piece originated as a monologue for the 2011 Dublin Theatre Festival. Hearing an actor perform the piece would probably bring some needed emotional depth to certain passages.

In an interesting reversal of patriarchal language, Mary never refers to the two apostles by name, though one is clearly John. The only characters with given names are Miriam and Mary, Lazarus, and Marcus. Even Jesus is never called by name.

The strongest section of the novel is the trial and crucifixion. Here Toibin brings anguishing energy to the prose:

“He was the boy I had given birth to and he was more defenceless now than he had been then. And in those days after he was born, when I held him and watched him, my thoughts included the thought that I would have someone now to watch over me when I was dying, to look after my body when I had died. In those days if I had even dreamed that I would see him bloody, and the crowd around filled with zeal that he should be bloodied more, I would have cried out as I cried out that day and the cry would have come from a part of me that is the core of me. The rest of me is merely flesh and blood and bone.”

While I found the work interesting, for me it's understatement left me wanting more. For all her justifiable bitterness and personal regrets, Mary doesn’t appear to reconcile herself to her actions. Maybe that’s the point: Mary is often presented as the ideal mother, and here she is having doubts and fears, like anyone might have.

Published on February 20, 2017 06:49

February 2, 2017

Book Review: All That Man Is

Instead of the seven ages of Man, David Szalay goes two better than Shakespeare and gives us nine. In All That Man Is, he presents a prototypical male – in this case, white European – at various stages of life. Each chapter features a self-contained story of a man floundering in a world he doesn’t quite understand. We follow the progress across the ages, from a 17-year-old student on a trip across Europe to a 73-year-old man on retreat in Italy.

Each story follows the same structure: the main character is traveling away from home and is outside his comfort zone. He has no close friends, merely associates. There is a longing for love, even if the man is already in a significant relationship.

In the first tale, 17-year-old Simon is traveling with his friend Ferdinand, but his thoughts are on Karen Fielding, a girl he knows from school. It is unrequited love, and that’s what makes it so poignantly romantic to Simon. All he wants is to return home to explore this new relationship, yet he hesitates because dreams are safer than possible failure. When he and Ferdinand rent a spare room in an apartment, the landlady boldly flirts with Simon. Even when she becomes practically brazen, he ignores the suggestions – out of shyness, innocence, or fear – he needs to maintain the purity of his fantasy love rather than succumb to sordid reality.

In the first tale, 17-year-old Simon is traveling with his friend Ferdinand, but his thoughts are on Karen Fielding, a girl he knows from school. It is unrequited love, and that’s what makes it so poignantly romantic to Simon. All he wants is to return home to explore this new relationship, yet he hesitates because dreams are safer than possible failure. When he and Ferdinand rent a spare room in an apartment, the landlady boldly flirts with Simon. Even when she becomes practically brazen, he ignores the suggestions – out of shyness, innocence, or fear – he needs to maintain the purity of his fantasy love rather than succumb to sordid reality.

In the fourth story, Szalay channels Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” when Karel learns that his girlfriend Waleria is pregnant. Because a child would disrupt his professional plans, he pressures her to have an abortion. Karel exhibits the worst characteristics of male dominance – questioning whether the child is his, using emotional blackmail to get his way. Waleria calls him on his selfishness, but that is not something he can fathom about himself.

Szalay’s male characters feel like they don’t know how to fit into the world. They are ill at ease, even when they are good at the game of appearing confident. There is a sense that time is running out on them. At the end of the sixth story, James is walking with his son Tom, who keeps running ahead. For all his plans to build a successful future, James is deeply aware that youth is getting out of reach, so he practices his current mantra: Life is not a joke.

The female characters have a marginal presence in the stories, since the men simply don’t know how to relate. Men are more focused on their careers, on beating out their rivals, on achieving professional success. Even in the stories in which the main character is attracted to a woman, there is never a sense of emotional attachment. Women are something to be attained. Instead, the men succumb to a sort of existential longing for love but lack the ability to define what that need is.

There is a certain presumptuousness to the title: All That Man Is, while it covers broad themes, keeps to a very white male perspective. The characters come from a variety of European nations, yet there is a thematic connectedness across the stories, even to the point that they tangentially touch one another. For example, in the last chapter, you learn that Tony is the grandfather of Simon from the first chapter. Does it matter? Only as a way to stress the threadbare connections that men feel. "Men need to grow up already!"

"Men need to grow up already!"

By chance, I read this novel on my way to the Women’s March in DC. I would say that it was an ironic choice on my part, but the truth is that the novel was a perfect example of the patriarchy that women are protesting. Feminism, for me, promotes a sense that everyone has a story, and that one narrative thread doesn’t fit all.

Szalay suggests that part of the troubling limitations that men feel is that they remain isolated from one another. They forgo deeper connection because they are uncertain of their place in the world. Perhaps if the characters in All That Man Is were to open themselves to a Feminist viewpoint, there wouldn’t be such a pervasive atmosphere of displacement and loss. In other words, if all that man is is that he doesn’t know where he fits in, perhaps he’d better start evolving and learning how to live in the real world.

Each story follows the same structure: the main character is traveling away from home and is outside his comfort zone. He has no close friends, merely associates. There is a longing for love, even if the man is already in a significant relationship.

In the first tale, 17-year-old Simon is traveling with his friend Ferdinand, but his thoughts are on Karen Fielding, a girl he knows from school. It is unrequited love, and that’s what makes it so poignantly romantic to Simon. All he wants is to return home to explore this new relationship, yet he hesitates because dreams are safer than possible failure. When he and Ferdinand rent a spare room in an apartment, the landlady boldly flirts with Simon. Even when she becomes practically brazen, he ignores the suggestions – out of shyness, innocence, or fear – he needs to maintain the purity of his fantasy love rather than succumb to sordid reality.

In the first tale, 17-year-old Simon is traveling with his friend Ferdinand, but his thoughts are on Karen Fielding, a girl he knows from school. It is unrequited love, and that’s what makes it so poignantly romantic to Simon. All he wants is to return home to explore this new relationship, yet he hesitates because dreams are safer than possible failure. When he and Ferdinand rent a spare room in an apartment, the landlady boldly flirts with Simon. Even when she becomes practically brazen, he ignores the suggestions – out of shyness, innocence, or fear – he needs to maintain the purity of his fantasy love rather than succumb to sordid reality.In the fourth story, Szalay channels Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” when Karel learns that his girlfriend Waleria is pregnant. Because a child would disrupt his professional plans, he pressures her to have an abortion. Karel exhibits the worst characteristics of male dominance – questioning whether the child is his, using emotional blackmail to get his way. Waleria calls him on his selfishness, but that is not something he can fathom about himself.

Szalay’s male characters feel like they don’t know how to fit into the world. They are ill at ease, even when they are good at the game of appearing confident. There is a sense that time is running out on them. At the end of the sixth story, James is walking with his son Tom, who keeps running ahead. For all his plans to build a successful future, James is deeply aware that youth is getting out of reach, so he practices his current mantra: Life is not a joke.

The female characters have a marginal presence in the stories, since the men simply don’t know how to relate. Men are more focused on their careers, on beating out their rivals, on achieving professional success. Even in the stories in which the main character is attracted to a woman, there is never a sense of emotional attachment. Women are something to be attained. Instead, the men succumb to a sort of existential longing for love but lack the ability to define what that need is.

There is a certain presumptuousness to the title: All That Man Is, while it covers broad themes, keeps to a very white male perspective. The characters come from a variety of European nations, yet there is a thematic connectedness across the stories, even to the point that they tangentially touch one another. For example, in the last chapter, you learn that Tony is the grandfather of Simon from the first chapter. Does it matter? Only as a way to stress the threadbare connections that men feel.

"Men need to grow up already!"

"Men need to grow up already!"By chance, I read this novel on my way to the Women’s March in DC. I would say that it was an ironic choice on my part, but the truth is that the novel was a perfect example of the patriarchy that women are protesting. Feminism, for me, promotes a sense that everyone has a story, and that one narrative thread doesn’t fit all.

Szalay suggests that part of the troubling limitations that men feel is that they remain isolated from one another. They forgo deeper connection because they are uncertain of their place in the world. Perhaps if the characters in All That Man Is were to open themselves to a Feminist viewpoint, there wouldn’t be such a pervasive atmosphere of displacement and loss. In other words, if all that man is is that he doesn’t know where he fits in, perhaps he’d better start evolving and learning how to live in the real world.

Published on February 02, 2017 06:54