Louis Arata's Blog, page 11

March 22, 2016

Is There a Problem Here, or Is It Just Me?

Right now I’m reading a novel that isn’t grabbing me. I feel like it should, because it’s an interesting premise, and the writing itself is serviceable.

Some of my apathy is due to the fact that I initially had trouble grabbing hold of the story’s central conceit, and even now after catching on to what the author is doing, I keep expecting to be pulled in to the story, yet I’m not.

Which leaves me with the question: is the book failing, or is it just me?

Back in college, on my own initiative, I read Oliver Twist. I hated it. Ten years later I decided to give it another go. Still hated it. Fifteen years after that, I gave the big-eyed, pale-faced orphan one more shot. And this time I was thoroughly charmed. Excuse me, sir, may I have some more plot?

Excuse me, sir, may I have some more plot?

What happened? Dickens hadn’t come along and updated the plot. There weren’t suddenly superheroes involved or abandoned kittens. The book hadn’t changed one bit, so it must have been me.

All I can figure is that my baggage was getting in the way. I come to books with certain expectations, and if the author satisfies them or exceeds them, then I am thoroughly caught up.

But that must not always be the case. Typically I read on my commute to work. But lately I have been too restless to read for very long. And this current book has been difficult to pick up. Is that due to the book’s shortcomings or my own distractibility?

In other words, if I were to approach this book in another ten years, would I have a different reaction to it?

This morning I feel like I cheated because I checked out some reviews on GoodReads. Many were very favorable, and lots of 4 and 5 star reviews. But those who gave lower ratings mentioned the very issues I have been struggling with – that despite an intriguing premise, the characters weren’t terribly engaging.

So, now I’m wondering if it’s the book, or maybe I’m just not a fan. Even if I have a limited capacity as an engaged reader, I definitely want to give the book a fair chance.

But the more I ponder these questions, the more I recognize that, bottom line, I’m bored, and it’s only tenacity that will get me to the end.

I’m glad the author has other fans. Right now I guess I’m not one.

Some of my apathy is due to the fact that I initially had trouble grabbing hold of the story’s central conceit, and even now after catching on to what the author is doing, I keep expecting to be pulled in to the story, yet I’m not.

Which leaves me with the question: is the book failing, or is it just me?

Back in college, on my own initiative, I read Oliver Twist. I hated it. Ten years later I decided to give it another go. Still hated it. Fifteen years after that, I gave the big-eyed, pale-faced orphan one more shot. And this time I was thoroughly charmed.

Excuse me, sir, may I have some more plot?

Excuse me, sir, may I have some more plot?What happened? Dickens hadn’t come along and updated the plot. There weren’t suddenly superheroes involved or abandoned kittens. The book hadn’t changed one bit, so it must have been me.

All I can figure is that my baggage was getting in the way. I come to books with certain expectations, and if the author satisfies them or exceeds them, then I am thoroughly caught up.

But that must not always be the case. Typically I read on my commute to work. But lately I have been too restless to read for very long. And this current book has been difficult to pick up. Is that due to the book’s shortcomings or my own distractibility?

In other words, if I were to approach this book in another ten years, would I have a different reaction to it?

This morning I feel like I cheated because I checked out some reviews on GoodReads. Many were very favorable, and lots of 4 and 5 star reviews. But those who gave lower ratings mentioned the very issues I have been struggling with – that despite an intriguing premise, the characters weren’t terribly engaging.

So, now I’m wondering if it’s the book, or maybe I’m just not a fan. Even if I have a limited capacity as an engaged reader, I definitely want to give the book a fair chance.

But the more I ponder these questions, the more I recognize that, bottom line, I’m bored, and it’s only tenacity that will get me to the end.

I’m glad the author has other fans. Right now I guess I’m not one.

Published on March 22, 2016 07:44

March 13, 2016

Book Review: How Fiction Works

When the student is ready, the teacher arrives.

That’s how I feel about James Wood’s How Fiction Works. I was looking for some writing guidance – a fresh perspective on plot, story-craft, and language. When I googled books on writing, several books popped up:

On Writing, Stephen KingThe Elements of Style, Strunk and WhiteBird by Bird, Anne LamottThe Art of Fiction, Henry JamesAspects of the Novel, E.M. Forster

All very helpful books, but I’ve read them, so I kept digging and came up with Wood’s 2008 work. His approach is to ask a series of questions on realism, character, imaginative sympathy, and the capacity of fiction to move us. His larger argument is “that fiction is both artifice and verisimilitude, and that there is nothing difficult in holding together these two possibilities.”

Wood offers up insight into narrative techniques that I have been trying to comprehend. For example, first person narration is very compelling because it elicits a level of sympathy in the reader. But not all stories will benefit from first-person. Other choices include multiple narrators or third-person limited perspective.

Wood offers up insight into narrative techniques that I have been trying to comprehend. For example, first person narration is very compelling because it elicits a level of sympathy in the reader. But not all stories will benefit from first-person. Other choices include multiple narrators or third-person limited perspective.

But then Wood proposes the sentence, “Ted watched the orchestra through stupid tears.” He explains the significance that solitary word “stupid” as something that touches on Ted’s response to the music while still retaining the authorial voice.

It appears to be a simple technique, but Wood then explores the carefully balanced blending of authorial voice and character voice through free indirect style:

First your start with words ...“[We] see things through the character’s eyes and language but also through the author’s eyes and language. We inhabit omniscience and partiality at once. A gap opens between author and character, and the bridge – which is free indirect style itself – between them simultaneously closes that gap and draws attention to its distance.”

First your start with words ...“[We] see things through the character’s eyes and language but also through the author’s eyes and language. We inhabit omniscience and partiality at once. A gap opens between author and character, and the bridge – which is free indirect style itself – between them simultaneously closes that gap and draws attention to its distance.”

Mining further examples from the literary canon, Wood also addresses detail, character, language and dialogue. So often I feel like he is giving me answers to questions that I have been wrangling with. For example, when I am describing a location, how do I determine the salient details? How do writers select the telling images so that the reader can fill in the edges? After all, that is the magic of fiction: the selective, evocative detail in setting, character, plot that conjures up the bigger picture.

My only complaint about How Fiction Works is that it predominately sticks to the white male canon of literature. I realize that Wood chooses examples from familiar authors, but it leaves me wondering how other voices (female authors, non-white writers, non-English-speaking cultures) may have different tactics.

Still, Wood has gotten me thinking about the writing craft, and that is what I wanted.

That’s how I feel about James Wood’s How Fiction Works. I was looking for some writing guidance – a fresh perspective on plot, story-craft, and language. When I googled books on writing, several books popped up:

On Writing, Stephen KingThe Elements of Style, Strunk and WhiteBird by Bird, Anne LamottThe Art of Fiction, Henry JamesAspects of the Novel, E.M. Forster

All very helpful books, but I’ve read them, so I kept digging and came up with Wood’s 2008 work. His approach is to ask a series of questions on realism, character, imaginative sympathy, and the capacity of fiction to move us. His larger argument is “that fiction is both artifice and verisimilitude, and that there is nothing difficult in holding together these two possibilities.”

Wood offers up insight into narrative techniques that I have been trying to comprehend. For example, first person narration is very compelling because it elicits a level of sympathy in the reader. But not all stories will benefit from first-person. Other choices include multiple narrators or third-person limited perspective.

Wood offers up insight into narrative techniques that I have been trying to comprehend. For example, first person narration is very compelling because it elicits a level of sympathy in the reader. But not all stories will benefit from first-person. Other choices include multiple narrators or third-person limited perspective.But then Wood proposes the sentence, “Ted watched the orchestra through stupid tears.” He explains the significance that solitary word “stupid” as something that touches on Ted’s response to the music while still retaining the authorial voice.

It appears to be a simple technique, but Wood then explores the carefully balanced blending of authorial voice and character voice through free indirect style:

First your start with words ...“[We] see things through the character’s eyes and language but also through the author’s eyes and language. We inhabit omniscience and partiality at once. A gap opens between author and character, and the bridge – which is free indirect style itself – between them simultaneously closes that gap and draws attention to its distance.”

First your start with words ...“[We] see things through the character’s eyes and language but also through the author’s eyes and language. We inhabit omniscience and partiality at once. A gap opens between author and character, and the bridge – which is free indirect style itself – between them simultaneously closes that gap and draws attention to its distance.”Mining further examples from the literary canon, Wood also addresses detail, character, language and dialogue. So often I feel like he is giving me answers to questions that I have been wrangling with. For example, when I am describing a location, how do I determine the salient details? How do writers select the telling images so that the reader can fill in the edges? After all, that is the magic of fiction: the selective, evocative detail in setting, character, plot that conjures up the bigger picture.

My only complaint about How Fiction Works is that it predominately sticks to the white male canon of literature. I realize that Wood chooses examples from familiar authors, but it leaves me wondering how other voices (female authors, non-white writers, non-English-speaking cultures) may have different tactics.

Still, Wood has gotten me thinking about the writing craft, and that is what I wanted.

Published on March 13, 2016 12:17

March 8, 2016

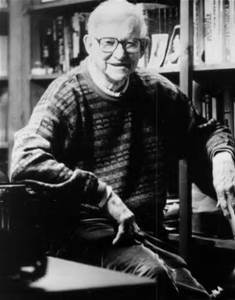

Book Review: The Chocolate War

I’ve been taking the 2016 Reading Challenge, which includes reading a book published this year, a book you can finish in a day, and a book recommended by a teacher or librarian.

For a book that was banned at some point, I’ve chosen Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War. It’s one I’ve been intending to read for a while but I’ve had a hard time tracking down a copy.

Set against a fundraiser for a Catholic high school for boys, The Chocolate War focuses on how a secret society (The Vigils) manipulates and influences individual behavior of students and teachers. The fundraiser – selling boxes of chocolates to raise capital for the school – appears fairly straight forward, except one boy, freshman Jerry Renault, who inexplicably refuses to sell any. It turns out that as a prank, Archie, a leader of The Vigils, convinces Jerry to refuse for ten days. But at the end of ten days, Jerry continues to not sell, which disrupts the school’s social equilibrium.

"The beautiful part of writing is that

"The beautiful part of writing is that

you don't have to get it right

the first time, unlike, say

brain surgery."

Robert CormierCornier moves easily through the ranks of students and teachers, citing their separate reactions that eventually will make up the growing mob mentality. Jerry is not a traditional rebel. Rather, he has stumbled into this role, and as he faces public censure, he also discovers his own integrity. What does it mean to fly in the face of public opinion? What are the risks to making individual choices that do not follow the norm?

No one is in control here, not even the diabolical Archie. He may have thought up the scheme, but he watches as it slips out of his grasp. To retain his control over The Vigils, as well as the student body and the teachers, he must twist the reins and drive everyone into acts of cruelty and sadism. What hope does Jerry have against the world?

Written in 1974, The Chocolate War has a distinctive tone as compared to today’s teen literature. There are no supernatural elements or intense romances. Instead, this is about the individual versus society. Certainly there are current dystopian novels that take on these themes (The Hunger Games and Divergent come to mind), but these are set in the future. Cormier’s novel is grounded in the everyday.

The Chocolate War is third on the ALA’s “Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books in 2000-2009,” ostensibly for its strong language, sexual content, and violence. My reaction is that the language is not particularly strong when compared to other works, and the sexual content is limited to thoughts or fantasies the teenage boys have.

Probably the reason the book is so often challenged is that it addresses mob mentality – the sadism that arises against a nonconformist. My guess is that the adults who have challenged this book are more distressed by what Cormier is showing about the cruelty in our society than they are about a few bad words and random sexual thoughts. They want cleaner books with clear cut villains and little wrangling of heavy moral issues, and certainly not a novel that ends with the hero in despair.

For a book that was banned at some point, I’ve chosen Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War. It’s one I’ve been intending to read for a while but I’ve had a hard time tracking down a copy.

Set against a fundraiser for a Catholic high school for boys, The Chocolate War focuses on how a secret society (The Vigils) manipulates and influences individual behavior of students and teachers. The fundraiser – selling boxes of chocolates to raise capital for the school – appears fairly straight forward, except one boy, freshman Jerry Renault, who inexplicably refuses to sell any. It turns out that as a prank, Archie, a leader of The Vigils, convinces Jerry to refuse for ten days. But at the end of ten days, Jerry continues to not sell, which disrupts the school’s social equilibrium.

"The beautiful part of writing is that

"The beautiful part of writing is thatyou don't have to get it right

the first time, unlike, say

brain surgery."

Robert CormierCornier moves easily through the ranks of students and teachers, citing their separate reactions that eventually will make up the growing mob mentality. Jerry is not a traditional rebel. Rather, he has stumbled into this role, and as he faces public censure, he also discovers his own integrity. What does it mean to fly in the face of public opinion? What are the risks to making individual choices that do not follow the norm?

No one is in control here, not even the diabolical Archie. He may have thought up the scheme, but he watches as it slips out of his grasp. To retain his control over The Vigils, as well as the student body and the teachers, he must twist the reins and drive everyone into acts of cruelty and sadism. What hope does Jerry have against the world?

Written in 1974, The Chocolate War has a distinctive tone as compared to today’s teen literature. There are no supernatural elements or intense romances. Instead, this is about the individual versus society. Certainly there are current dystopian novels that take on these themes (The Hunger Games and Divergent come to mind), but these are set in the future. Cormier’s novel is grounded in the everyday.

The Chocolate War is third on the ALA’s “Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books in 2000-2009,” ostensibly for its strong language, sexual content, and violence. My reaction is that the language is not particularly strong when compared to other works, and the sexual content is limited to thoughts or fantasies the teenage boys have.

Probably the reason the book is so often challenged is that it addresses mob mentality – the sadism that arises against a nonconformist. My guess is that the adults who have challenged this book are more distressed by what Cormier is showing about the cruelty in our society than they are about a few bad words and random sexual thoughts. They want cleaner books with clear cut villains and little wrangling of heavy moral issues, and certainly not a novel that ends with the hero in despair.

Published on March 08, 2016 05:39

March 1, 2016

Book Review: Descent

One of my beta readers for Reston Peace had some keen observations about multiple POVs in novels, and she recommended I read Tim Johnston’s Descent. I’m glad I did.

Descentfollows the Courtland family on their trip to Colorado. One morning, Caitlin goes for a jog up the mountain, with her younger brother Sean on his bike. When he is struck by a vehicle and suffers severe damage to his leg, Caitlin is abducted by the driver.

What follows is the dissolution of the family. Grant remains in Colorado to keep the search for his daughter in motion. Angela returns to Wisconsin and struggles to hold it together. And Sean runs away from home.

Johnston switches perspectives across the characters, each with heavy questions about how good and evil operate in the world. There is not much baring of souls here; the characters privately struggle and keep their questions to themselves. Instead of endless internal monologues, the author exploits the environment as representative of the mysteries they face:

Johnston switches perspectives across the characters, each with heavy questions about how good and evil operate in the world. There is not much baring of souls here; the characters privately struggle and keep their questions to themselves. Instead of endless internal monologues, the author exploits the environment as representative of the mysteries they face:

“Before them lay a broad glade of aspens, white and spare; the pinewood rising beyond, and in the far distance above the highest pines stood the snowy crags of the Rockies, fantastic in scale and burning in the light of their own immensity.”

You can almost imagine Frost’s “The woods are lovely, dark and deep” as each character’s private mantra.

Johnston takes great care in describing every day actions that are undertaken as a form of normalcy against the great dread that hangs over father and son. Sean restlessly travels across the U.S. in search of absolution or at least appeasement for his sense of guilt for his sister’s disappearance. When he is arrested, Grant comes to pick him up and return him to Colorado so together they can continue their search for Caitlin. But even their coming together again is not a sign of bonding; there is always the danger that Sean will run off again: "Whose woods these are,

"Whose woods these are,

I think I know ..."

“When [Grant] returned, the sun was low in the west behind the clouds and the room was nearly dark. The duvet had been thrown aside, and at the sight of the empty bed his heart dropped for a disbelieving instant before he saw that the bathroom door was shut, before he saw the seam of light at the floor and heard the exhaust fan groaning away on the other side.”

One interesting aspect about Sean's story is that Johnston refers to him as "the boy" throughout. It is as though he loses his identity with his sister's disappearance and only regains it at the end.

The ending is satisfyingly thrilling as well as poignantly crafted. Johnston is careful not to rush to the conclusion after the big climax; he gives the reader time to adjust to the new reality for the Courtland family.

My only complaint is that the book is very male dominated. There is a lot of cigarette smoking and a lot of brooding. The few female characters pretty much keep to the perimeter of the story. The mother, Angela, is more of a bookends character, and Caitlin is kept off-screen (albeit effectively) for much of the book.

Overall, a finely crafted novel that gave me some great lessons in POV.

Descentfollows the Courtland family on their trip to Colorado. One morning, Caitlin goes for a jog up the mountain, with her younger brother Sean on his bike. When he is struck by a vehicle and suffers severe damage to his leg, Caitlin is abducted by the driver.

What follows is the dissolution of the family. Grant remains in Colorado to keep the search for his daughter in motion. Angela returns to Wisconsin and struggles to hold it together. And Sean runs away from home.

Johnston switches perspectives across the characters, each with heavy questions about how good and evil operate in the world. There is not much baring of souls here; the characters privately struggle and keep their questions to themselves. Instead of endless internal monologues, the author exploits the environment as representative of the mysteries they face:

Johnston switches perspectives across the characters, each with heavy questions about how good and evil operate in the world. There is not much baring of souls here; the characters privately struggle and keep their questions to themselves. Instead of endless internal monologues, the author exploits the environment as representative of the mysteries they face:“Before them lay a broad glade of aspens, white and spare; the pinewood rising beyond, and in the far distance above the highest pines stood the snowy crags of the Rockies, fantastic in scale and burning in the light of their own immensity.”

You can almost imagine Frost’s “The woods are lovely, dark and deep” as each character’s private mantra.

Johnston takes great care in describing every day actions that are undertaken as a form of normalcy against the great dread that hangs over father and son. Sean restlessly travels across the U.S. in search of absolution or at least appeasement for his sense of guilt for his sister’s disappearance. When he is arrested, Grant comes to pick him up and return him to Colorado so together they can continue their search for Caitlin. But even their coming together again is not a sign of bonding; there is always the danger that Sean will run off again:

"Whose woods these are,

"Whose woods these are,I think I know ..."

“When [Grant] returned, the sun was low in the west behind the clouds and the room was nearly dark. The duvet had been thrown aside, and at the sight of the empty bed his heart dropped for a disbelieving instant before he saw that the bathroom door was shut, before he saw the seam of light at the floor and heard the exhaust fan groaning away on the other side.”

One interesting aspect about Sean's story is that Johnston refers to him as "the boy" throughout. It is as though he loses his identity with his sister's disappearance and only regains it at the end.

The ending is satisfyingly thrilling as well as poignantly crafted. Johnston is careful not to rush to the conclusion after the big climax; he gives the reader time to adjust to the new reality for the Courtland family.

My only complaint is that the book is very male dominated. There is a lot of cigarette smoking and a lot of brooding. The few female characters pretty much keep to the perimeter of the story. The mother, Angela, is more of a bookends character, and Caitlin is kept off-screen (albeit effectively) for much of the book.

Overall, a finely crafted novel that gave me some great lessons in POV.

Published on March 01, 2016 08:30

February 16, 2016

Book Review: Girl with a Pearl Earring

There is so much that is good in Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with a Pearl Earring: an independent heroine, an intriguing historical premise, and beautifully precise writing.

The sixteen year old Griet is the daughter of a tile maker in 17th Century Holland. When her family falls on hard times after their father is blinded in an accident, Griet takes work as a maid. She is hired into the household of the painter Johannes Vermeer and quickly learns how to navigate the family politics.

The only other servant in the household is Tanneke, who lords her seniority over Griet, and one of Vermeer’s daughters, Cordelia, takes cruel delight in antagonizing the new maid. The perpetually pregnant Catharina (Vermeer’s wife) is at turns suspicious and deliberately short-sighted when it comes to Griet’s growing relationship with the painter.

I'm not Scarlett Johannson

I'm not Scarlett Johannson

but I play her in the movieVermeer recognizes that Griet has an artist’s eye for colors and details, and soon he is enlisting her assistance in his studio. This must be done discreetly, but of course everyone knows what is going on even as no one speaks of it. As the relationship develops, as the attraction deepens, eventually Vermeer wants to paint Griet’s portrait, but this is a fatal step for either of them. The painter, obsessed with his artistic vision, refuses to consider the consequences, while Griet herself knows exactly how disastrous this will be. Yet she cannot say no.

Chevalier makes certain that this is no bodice-ripper of a novel. Instead, she focuses on the sexual attraction through symbolism of colors, shapes, textures. Even as she cannot withstand her fascination with Vermeer, Griet is too smart to fall into the trap of an affair. The painter becomes such the focus of her attention that he is never referred to by name. Instead, Vermeer is the perpetual “he” – the pronoun underscoring how there are no other males of such significance for Griet. Other characters may have names and personalities, but Vermeer is set above them, the master of more than the household. The idealized artist. The author also focuses on women’s roles in society, in particular the lowly status of maids, which seems only a step above a prostitute. Despite the societal limitations, Griet is savvy enough to know how to survive. There is great strength in her practicality. Even as she can long for love and romance, she knows precisely how the world works.

The author also focuses on women’s roles in society, in particular the lowly status of maids, which seems only a step above a prostitute. Despite the societal limitations, Griet is savvy enough to know how to survive. There is great strength in her practicality. Even as she can long for love and romance, she knows precisely how the world works.

My only complaint of the novel is the pacing. It runs like a driver who unwaveringly abides by the speed limit. While Chevalier develops the dramatic tension through the subtext, the story never picks up speed. It is certainly realistic that the inevitable explosion at the climax is about what is not said rather than about soul-exposing confessions. Still, I expected a bit more drive toward that ending.

The sixteen year old Griet is the daughter of a tile maker in 17th Century Holland. When her family falls on hard times after their father is blinded in an accident, Griet takes work as a maid. She is hired into the household of the painter Johannes Vermeer and quickly learns how to navigate the family politics.

The only other servant in the household is Tanneke, who lords her seniority over Griet, and one of Vermeer’s daughters, Cordelia, takes cruel delight in antagonizing the new maid. The perpetually pregnant Catharina (Vermeer’s wife) is at turns suspicious and deliberately short-sighted when it comes to Griet’s growing relationship with the painter.

I'm not Scarlett Johannson

I'm not Scarlett Johannsonbut I play her in the movieVermeer recognizes that Griet has an artist’s eye for colors and details, and soon he is enlisting her assistance in his studio. This must be done discreetly, but of course everyone knows what is going on even as no one speaks of it. As the relationship develops, as the attraction deepens, eventually Vermeer wants to paint Griet’s portrait, but this is a fatal step for either of them. The painter, obsessed with his artistic vision, refuses to consider the consequences, while Griet herself knows exactly how disastrous this will be. Yet she cannot say no.

Chevalier makes certain that this is no bodice-ripper of a novel. Instead, she focuses on the sexual attraction through symbolism of colors, shapes, textures. Even as she cannot withstand her fascination with Vermeer, Griet is too smart to fall into the trap of an affair. The painter becomes such the focus of her attention that he is never referred to by name. Instead, Vermeer is the perpetual “he” – the pronoun underscoring how there are no other males of such significance for Griet. Other characters may have names and personalities, but Vermeer is set above them, the master of more than the household. The idealized artist.

The author also focuses on women’s roles in society, in particular the lowly status of maids, which seems only a step above a prostitute. Despite the societal limitations, Griet is savvy enough to know how to survive. There is great strength in her practicality. Even as she can long for love and romance, she knows precisely how the world works.

The author also focuses on women’s roles in society, in particular the lowly status of maids, which seems only a step above a prostitute. Despite the societal limitations, Griet is savvy enough to know how to survive. There is great strength in her practicality. Even as she can long for love and romance, she knows precisely how the world works.My only complaint of the novel is the pacing. It runs like a driver who unwaveringly abides by the speed limit. While Chevalier develops the dramatic tension through the subtext, the story never picks up speed. It is certainly realistic that the inevitable explosion at the climax is about what is not said rather than about soul-exposing confessions. Still, I expected a bit more drive toward that ending.

Published on February 16, 2016 07:19

February 5, 2016

Book Review: CivilWarLand in Bad Decline

We live in a rundown Disneyland, at least according to George Saunders.

The American landscape is little more than a pasteboard-and-glitter amusement park, where the powerful and entitled come to play. And those who run the parks … Well, they’re the marginalized, forced into pathetic labor with no thought of reward or riches. This is their lot in life to serve others. In the short story collection CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, George Saunders creates satire that is at turns funny, scathing, and sad. Very sad. His narrators have all been beaten down by life to the point where self-respect is barely an option. From a 400 lb man who longs for love to a Flawed man with claws on his feet and his sister with a vestigial tail. Wounded people who are brutalized by the Normals who feel it is their god-given right to oppress, who see the sty in your eyes but not the log in their own.

In the short story collection CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, George Saunders creates satire that is at turns funny, scathing, and sad. Very sad. His narrators have all been beaten down by life to the point where self-respect is barely an option. From a 400 lb man who longs for love to a Flawed man with claws on his feet and his sister with a vestigial tail. Wounded people who are brutalized by the Normals who feel it is their god-given right to oppress, who see the sty in your eyes but not the log in their own.

In the title story, Mr. Alsuga cashes in on his love of history by creating CivilWarLand, an amusement park that gives visitors the chance to experience the past without all the inconveniences of verisimilitude. History is glossed over for more appealing tidbits – the quaint and cute side of the Civil War. But when a gang of youths begins terrorizing the park, Mr. Alsuga employs a sniper to take them out. The only problem is that the sniper is psychopathic, and there is collateral damage.

Other stories focus on characters struggling for dignity and love, but who are shamed into submission. This doesn’t sound particularly funny, but this is where Saunders knows how to employ his quirky, unexpected humor:

You'd better laugh

You'd better laugh

because otherwise

you'll cry“Halfway up the mountain it’s the Center for Wayward Nuns, full of sisters and other religious personnel who’ve become doubtful. Once a few of them came down to our facility in stern suits and swam cautiously. The singing from up there never exactly knocks your socks off. It’s very conditional singing, probably because of all the doubt.” (“The Wavemaker Falters”)

In the novella, “Bounty,” Saunders creates his most scathing landscape in which the American population is now divided into the Normal and the Flawed. The Flawed are forced to wear bracelets identifying them as such, and there are severe restrictions against interactions between the groups. Many of the Flawed live in a freak circus. For Cole and his sister Connie, this circus is supposed to provide them with a safety and security, but it’s all about providing amusement for the Normals. When Connie is purchased and taken away, Cole escapes from the circus and proceeds on a cross-country odyssey to rescue her. On the way, he encounters Normals with rather wretched lives who still feel superior to the Flawed.

Saunders’ critique of modern life is never more harsh than in “The 400-Pound CEO”:

“I have a sense that God is unfair and preferentially punishes his weak, his dumb, his fat, his lazy. I believe he takes more pleasure in his perfect creatures, and cheers them on like a brainless dad as they run roughshod over the rest of us. He gives us a need for love, and no way to get it. He gives us a desire to be liked, and personal attributes that make us utterly unlikable.”

But just when you’re at your most despairing, Saunders gives you a measure of hope:

“Maybe the God we see, the God who calls the daily shots, is merely a subGod. Maybe there’s a God above this subGod, who’s busy for a few Godminutes with something else, and will be right back, and when he gets back … will sweep me up in his arms, saying: My sincere apologies, a mistake has been made. Accept a new birth, as token of my esteem.”

The American landscape is little more than a pasteboard-and-glitter amusement park, where the powerful and entitled come to play. And those who run the parks … Well, they’re the marginalized, forced into pathetic labor with no thought of reward or riches. This is their lot in life to serve others.

In the short story collection CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, George Saunders creates satire that is at turns funny, scathing, and sad. Very sad. His narrators have all been beaten down by life to the point where self-respect is barely an option. From a 400 lb man who longs for love to a Flawed man with claws on his feet and his sister with a vestigial tail. Wounded people who are brutalized by the Normals who feel it is their god-given right to oppress, who see the sty in your eyes but not the log in their own.

In the short story collection CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, George Saunders creates satire that is at turns funny, scathing, and sad. Very sad. His narrators have all been beaten down by life to the point where self-respect is barely an option. From a 400 lb man who longs for love to a Flawed man with claws on his feet and his sister with a vestigial tail. Wounded people who are brutalized by the Normals who feel it is their god-given right to oppress, who see the sty in your eyes but not the log in their own.In the title story, Mr. Alsuga cashes in on his love of history by creating CivilWarLand, an amusement park that gives visitors the chance to experience the past without all the inconveniences of verisimilitude. History is glossed over for more appealing tidbits – the quaint and cute side of the Civil War. But when a gang of youths begins terrorizing the park, Mr. Alsuga employs a sniper to take them out. The only problem is that the sniper is psychopathic, and there is collateral damage.

Other stories focus on characters struggling for dignity and love, but who are shamed into submission. This doesn’t sound particularly funny, but this is where Saunders knows how to employ his quirky, unexpected humor:

You'd better laugh

You'd better laughbecause otherwise

you'll cry“Halfway up the mountain it’s the Center for Wayward Nuns, full of sisters and other religious personnel who’ve become doubtful. Once a few of them came down to our facility in stern suits and swam cautiously. The singing from up there never exactly knocks your socks off. It’s very conditional singing, probably because of all the doubt.” (“The Wavemaker Falters”)

In the novella, “Bounty,” Saunders creates his most scathing landscape in which the American population is now divided into the Normal and the Flawed. The Flawed are forced to wear bracelets identifying them as such, and there are severe restrictions against interactions between the groups. Many of the Flawed live in a freak circus. For Cole and his sister Connie, this circus is supposed to provide them with a safety and security, but it’s all about providing amusement for the Normals. When Connie is purchased and taken away, Cole escapes from the circus and proceeds on a cross-country odyssey to rescue her. On the way, he encounters Normals with rather wretched lives who still feel superior to the Flawed.

Saunders’ critique of modern life is never more harsh than in “The 400-Pound CEO”:

“I have a sense that God is unfair and preferentially punishes his weak, his dumb, his fat, his lazy. I believe he takes more pleasure in his perfect creatures, and cheers them on like a brainless dad as they run roughshod over the rest of us. He gives us a need for love, and no way to get it. He gives us a desire to be liked, and personal attributes that make us utterly unlikable.”

But just when you’re at your most despairing, Saunders gives you a measure of hope:

“Maybe the God we see, the God who calls the daily shots, is merely a subGod. Maybe there’s a God above this subGod, who’s busy for a few Godminutes with something else, and will be right back, and when he gets back … will sweep me up in his arms, saying: My sincere apologies, a mistake has been made. Accept a new birth, as token of my esteem.”

Published on February 05, 2016 08:02

January 18, 2016

Book Review: The Circle

Mae gets a job at the Circle, a mega-technological firm that has its hands in everything from the internet to social media and is gobbling up starts-up like so much plankton. The Circle rewards its employees with fantastic health care, access to new gadgets, and endless scores of products to test and review. Its business goal is to make its products ubiquitous in every aspect of daily life. A sort of benevolent dictatorship of all things technological.

At first Mae is overwhelmed by the business campus, with its vast lunchrooms, fitness centers, swimming pools, and even studio apartments for employees too busy to go home. She also discovers that the work pace requires the dexterity of an octopus as more and more computer screens are placed on her desk. Social media is as much a part of the work environment as responding to customer queries. Not only does Mae have to keep up a 98% approval rating in her work, she also has to participate in commenting on and responding to postings and reviews by her co-workers. And her co-workers are an enthusiastic lot with hypersensitive egos, quick to be hurt if they think Mae is slighting them by not interacting with their running commentaries. After a rough learning curve, Mae starts getting the hang of the Circle’s expectations, and soon she is participating in everything.

At first Mae is overwhelmed by the business campus, with its vast lunchrooms, fitness centers, swimming pools, and even studio apartments for employees too busy to go home. She also discovers that the work pace requires the dexterity of an octopus as more and more computer screens are placed on her desk. Social media is as much a part of the work environment as responding to customer queries. Not only does Mae have to keep up a 98% approval rating in her work, she also has to participate in commenting on and responding to postings and reviews by her co-workers. And her co-workers are an enthusiastic lot with hypersensitive egos, quick to be hurt if they think Mae is slighting them by not interacting with their running commentaries. After a rough learning curve, Mae starts getting the hang of the Circle’s expectations, and soon she is participating in everything.

Dave Eggars’ novel The Circle tackles the subsuming of human interaction into shallow connections through the internet. There is no such thing as close friends or deep dialogue; every form of communication is reduced to emoji and sharing. And at the rate the Circle is tapping into every aspect of a person’s life, people’s identities are nothing more than their TruSelf, their on-line avatar.

Be true to your

Be true to your

TruSelfEggars is unnervingly perceptive in his social critique, carrying ideas to their inevitable conclusions. The Circle is probably the most accurately predictive dystopian novel out there. By blending together Google, FaceBook, Twitter, and other forms of social media, he creates a chillingly recognizable world.

But here’s my problem with the book: do I praise Eggars’ concept or do I address how tedious the writing can be?

I don’t skim books, but I confess that once or twice I was speed-reading through some redundant scenes. A character discusses how some technology will change the world, and it gets launched, then another character describes another tech gadget and how it will be the next big thing. I realize Eggars is building a world based closely on our own, so he takes his time to make everything seem plausible and familiar. But after a while I kept thinking, “Okay, I get it. Let’s move on.”

As a main character, Mae is not terribly interesting. She has no personality and isn’t particularly likable. So, is this Eggars’ critique that people don’t feel they exist as individuals until they connect through social media? Or would it have worked better if Mae had been her own person at the beginning of the novel and eventually got devoured by the Circle?

The novel takes a compelling turn once Mae chooses to go transparent. This is one of the primary topics of the story: the assumption that if everything is known and nothing hidden, then humans will learn to behave better. If we are always under surveillance, we will not commit crimes. If we are always performing before an audience, we will be our best selves.

Mae starts wearing a camera that broadcasts her life 24/7 and soon discovers how addictive it is to have millions of followers commenting and praising her choices in life. However, the pressure to please all of them creates a psychic fissure until her neediness for their approval starts determining all her actions. She is no longer an individual but an avatar for her legion of fans.

Eggars’ ideas are compelling and will definitely stay with me. They have even made me reconsider how I interact over social media. But the biggest drawback to The Circle is the quality of the writing. I am definitely a fan of Eggars, but I expected something more from his pacing and storytelling.

At first Mae is overwhelmed by the business campus, with its vast lunchrooms, fitness centers, swimming pools, and even studio apartments for employees too busy to go home. She also discovers that the work pace requires the dexterity of an octopus as more and more computer screens are placed on her desk. Social media is as much a part of the work environment as responding to customer queries. Not only does Mae have to keep up a 98% approval rating in her work, she also has to participate in commenting on and responding to postings and reviews by her co-workers. And her co-workers are an enthusiastic lot with hypersensitive egos, quick to be hurt if they think Mae is slighting them by not interacting with their running commentaries. After a rough learning curve, Mae starts getting the hang of the Circle’s expectations, and soon she is participating in everything.

At first Mae is overwhelmed by the business campus, with its vast lunchrooms, fitness centers, swimming pools, and even studio apartments for employees too busy to go home. She also discovers that the work pace requires the dexterity of an octopus as more and more computer screens are placed on her desk. Social media is as much a part of the work environment as responding to customer queries. Not only does Mae have to keep up a 98% approval rating in her work, she also has to participate in commenting on and responding to postings and reviews by her co-workers. And her co-workers are an enthusiastic lot with hypersensitive egos, quick to be hurt if they think Mae is slighting them by not interacting with their running commentaries. After a rough learning curve, Mae starts getting the hang of the Circle’s expectations, and soon she is participating in everything.Dave Eggars’ novel The Circle tackles the subsuming of human interaction into shallow connections through the internet. There is no such thing as close friends or deep dialogue; every form of communication is reduced to emoji and sharing. And at the rate the Circle is tapping into every aspect of a person’s life, people’s identities are nothing more than their TruSelf, their on-line avatar.

Be true to your

Be true to yourTruSelfEggars is unnervingly perceptive in his social critique, carrying ideas to their inevitable conclusions. The Circle is probably the most accurately predictive dystopian novel out there. By blending together Google, FaceBook, Twitter, and other forms of social media, he creates a chillingly recognizable world.

But here’s my problem with the book: do I praise Eggars’ concept or do I address how tedious the writing can be?

I don’t skim books, but I confess that once or twice I was speed-reading through some redundant scenes. A character discusses how some technology will change the world, and it gets launched, then another character describes another tech gadget and how it will be the next big thing. I realize Eggars is building a world based closely on our own, so he takes his time to make everything seem plausible and familiar. But after a while I kept thinking, “Okay, I get it. Let’s move on.”

As a main character, Mae is not terribly interesting. She has no personality and isn’t particularly likable. So, is this Eggars’ critique that people don’t feel they exist as individuals until they connect through social media? Or would it have worked better if Mae had been her own person at the beginning of the novel and eventually got devoured by the Circle?

The novel takes a compelling turn once Mae chooses to go transparent. This is one of the primary topics of the story: the assumption that if everything is known and nothing hidden, then humans will learn to behave better. If we are always under surveillance, we will not commit crimes. If we are always performing before an audience, we will be our best selves.

Mae starts wearing a camera that broadcasts her life 24/7 and soon discovers how addictive it is to have millions of followers commenting and praising her choices in life. However, the pressure to please all of them creates a psychic fissure until her neediness for their approval starts determining all her actions. She is no longer an individual but an avatar for her legion of fans.

Eggars’ ideas are compelling and will definitely stay with me. They have even made me reconsider how I interact over social media. But the biggest drawback to The Circle is the quality of the writing. I am definitely a fan of Eggars, but I expected something more from his pacing and storytelling.

Published on January 18, 2016 06:40

January 3, 2016

The Top Ten Books (I've Read) of 2015

It’s time for another subjective list of Best of … Out of the 50 books I’ve read this year, these are my top ten.

Going back over the list, I had to make some judicious choices on which books to include, because many were very close to making the cut. On the other hand, there are only two books that stood out as definite Best of winners: Olive Kitteredge and A Raisin in the Sun. At the end, I will include the titles of all the books I read this year.

So, in no particular order, here are my favorites:

Nick and Norah’s Infinite PlaylistRachel Cohn and David Levithan

Nick and Norah’s Infinite PlaylistRachel Cohn and David Levithan

Nick needs a girlfriend for five minutes, just so he can survive an encounter with his ex. Who is standing next to him? Norah. So begins a funny, chaotic, thrilling tumble of a night as Nick and Norah hang out together and struggle to comprehend their instant attraction to each other. Both are disentangling themselves from toxic exes, and though neither feels ready to plunge into a new romance. But how can you say no to someone who intrigues you? This book had me grinning all the way through, and I left it feeling light and happy.

Troubled Daughters, Twisted WivesSarah Weinman (editor)

Troubled Daughters, Twisted WivesSarah Weinman (editor)

Okay, I’m actually still reading this one, but I’m about two-thirds of the way through, so unless the last few stories crash and burn, this one certainly makes the list. It’s a collection of short stories by female authors, primarily from pulp magazines Ellery Queen and Alfred Hitchcock. Every story is well-written and engaging, with great plotting and great characterization. These writers are phenomenal storytellers and deserve to remain forever in the spotlight: Patricia Highsmith, Shirley Jackson, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Vera Caspery, and many others.

A Raisin in the SunLorraine Hansberry

A Raisin in the SunLorraine Hansberry

Everything I love about theatre: every character bursting with life, every interaction rich in dimensions, a beautiful blending of struggle and hope. This play is vying with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? as my all-time favorite play.

The Secret History of Wonder WomanJill Lepore

The Secret History of Wonder WomanJill Lepore

Who knew? Who knew that Wonder Woman was created by a psychologist/lawyer who lived an unconventional life with his wife and a former grad-student? Who knew that Wonder Woman/Diana Prince grew directly out of suffragism and the early women’s movement? A fascinating history that was deliberately kept secret for years to protect the reputation of some notable women of the day.

The RedbreastJo Nesbo

The RedbreastJo Nesbo

I didn’t review this book earlier but I should have. Detective Harry Hole investigates a series of neo-Nazi crimes that ultimately link back to a Norwegian soldier in WWII who fought for the Nazis. A gripping adventure story that straddles two time periods and multiple stories that drives toward a thrilling conclusion. The Redbreast is the third in the Harry Hole series but the first that was translated into English. Currently there are ten books in the series.

Boy ToyBarry Lyga

Boy ToyBarry Lyga

Don’t let the title fool you: this is not a charming coming-of-age story. This is about sexual abuse. Author Barry Lyga tackles a topic that is typically sugarcoated as a young boy is initiated into the wonders of sex by an older, more experienced woman. But this book is about how a sexual predator can manipulate the thoughts and behaviors of a youth, so much so that the boy can’t quite believe that he is being abused because, for him, he is in love.

BruiserNeal Shusterman

BruiserNeal Shusterman

Bruiser Rawlins isn’t simply a hulking teen; he is a true empath, able to literally take on the pains and illness of those he loves. He is able to drain off every cut, bruise, and broken heart, but the accumulation of suffering is physically killing him. How do you allow yourself to love someone if it could cost you your life? Author Neal Shusterman examines both the debilitating and healing aspects of being human.

Olive KitteredgeElizabeth Strout

Olive KitteredgeElizabeth Strout

A Pulitzer Prize winner, and well-deserving. A collection of thirteen tales, each self-contained yet also part of the larger whole. Across these tales moves Olive Kitteredge, abrasive, opinionated, aloof. She is like a single-masted cutter cutting across people’s lives. She is difficult to get to know, yet her presence is pervasive and compelling; you feel her enter the room. Some people like her, others do not, but everyone has a grudging respect for her. As a writer, I soaked up every bit of author Elizabeth Strout’s language as a masterclass in prose. It is that good.

Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar ChildrenRansom Riggs

Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar ChildrenRansom Riggs

Damn! I wish I’d thought of it first: a novel about children with peculiar abilities: a little girl capable of levitating, a boy with bees living in his chest, a girl able to conjure fire in her hands. What gives this novel a fascinating edge is that the author uses actual vintage photos to depict the characters. You get to see that levitating girl, and you’re left wondering what the back-story of the photo might be. Author Ransom Riggs gives his own explanations, as it were, in constructing a story against the backdrop of WWII. Great writing, great adventure. There are two more books in the series. I’ve just finished Hollow City and now need to get my hands on Library of Souls.

BonkMary Roach

BonkMary Roach

Mary Roach is one of my favorites. She takes the most unusual subjects and delves into their peculiar histories. Bonktackles the intersection of science and sex. I may have suffered a bit of squeamishness and (yes) prudery in reading the details of the various researches, but Roach knows exactly when to be scientific in her terminology and when to plop in the perfect analogy, all with her customary wit.

The rest of the 50 books:

Compulsion, Heidi AyarbeWaiting for Godot, Samnuel BeckettMcSweeeney’s Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories, Michael Chabon, ed.Charles Dickens: The Last of the Great Men, G.K. ChesteronRunaway Ralph, Beverly ClearyGreat Short Works, Stephen CraneDombey and Son, Charles DickensHarlan Ellison’s Watching, Harlan EllisonShadow & Act Ralph EllisonThe Great Gatsby, F. Scott FitzgeraldThe Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor DostoyevskyMurder Boogies with Elvis, Anne GeorgeOld Yeller, Fred GipsonBlood Work, L.J. HaywardI’m with Stupid, Geoff HerbachNothing Special, Geoff HerbachSiddhartha, Herman HesseTilt, Ellen HopkinsThe Buried Giant, Kazuo IshiguroThe Jungle Books, Rudyard KiplingAn End to the Thrill, Varun KumarCreed, Trisha Leaver and Lindsay CurrieLet the Old Dreams Die, John Ajvide LindqvistA Game of Thrones, George R.R. MartinSomebody, Tell Me Who I Am, Harry MazerBilly Budd, Sailor, Herman MelvilleSchulz and Peanuts: A Biography, David MichaelisThe Book of Dragons, E. NesbitHollow City, Ransom RiggsDivergent, Veronica RothSt. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, Karen RussellBait, Alex SanchezA Journey to Matecumbe, Robert Lewis TaylorWalden, Henry David ThoreauNight, Elie WieselThe Midwich Cuckoos, John Wyndham

Going back over the list, I had to make some judicious choices on which books to include, because many were very close to making the cut. On the other hand, there are only two books that stood out as definite Best of winners: Olive Kitteredge and A Raisin in the Sun. At the end, I will include the titles of all the books I read this year.

So, in no particular order, here are my favorites:

Nick and Norah’s Infinite PlaylistRachel Cohn and David Levithan

Nick and Norah’s Infinite PlaylistRachel Cohn and David LevithanNick needs a girlfriend for five minutes, just so he can survive an encounter with his ex. Who is standing next to him? Norah. So begins a funny, chaotic, thrilling tumble of a night as Nick and Norah hang out together and struggle to comprehend their instant attraction to each other. Both are disentangling themselves from toxic exes, and though neither feels ready to plunge into a new romance. But how can you say no to someone who intrigues you? This book had me grinning all the way through, and I left it feeling light and happy.

Troubled Daughters, Twisted WivesSarah Weinman (editor)

Troubled Daughters, Twisted WivesSarah Weinman (editor)Okay, I’m actually still reading this one, but I’m about two-thirds of the way through, so unless the last few stories crash and burn, this one certainly makes the list. It’s a collection of short stories by female authors, primarily from pulp magazines Ellery Queen and Alfred Hitchcock. Every story is well-written and engaging, with great plotting and great characterization. These writers are phenomenal storytellers and deserve to remain forever in the spotlight: Patricia Highsmith, Shirley Jackson, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Vera Caspery, and many others.

A Raisin in the SunLorraine Hansberry

A Raisin in the SunLorraine HansberryEverything I love about theatre: every character bursting with life, every interaction rich in dimensions, a beautiful blending of struggle and hope. This play is vying with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? as my all-time favorite play.

The Secret History of Wonder WomanJill Lepore

The Secret History of Wonder WomanJill LeporeWho knew? Who knew that Wonder Woman was created by a psychologist/lawyer who lived an unconventional life with his wife and a former grad-student? Who knew that Wonder Woman/Diana Prince grew directly out of suffragism and the early women’s movement? A fascinating history that was deliberately kept secret for years to protect the reputation of some notable women of the day.

The RedbreastJo Nesbo

The RedbreastJo NesboI didn’t review this book earlier but I should have. Detective Harry Hole investigates a series of neo-Nazi crimes that ultimately link back to a Norwegian soldier in WWII who fought for the Nazis. A gripping adventure story that straddles two time periods and multiple stories that drives toward a thrilling conclusion. The Redbreast is the third in the Harry Hole series but the first that was translated into English. Currently there are ten books in the series.

Boy ToyBarry Lyga

Boy ToyBarry LygaDon’t let the title fool you: this is not a charming coming-of-age story. This is about sexual abuse. Author Barry Lyga tackles a topic that is typically sugarcoated as a young boy is initiated into the wonders of sex by an older, more experienced woman. But this book is about how a sexual predator can manipulate the thoughts and behaviors of a youth, so much so that the boy can’t quite believe that he is being abused because, for him, he is in love.

BruiserNeal Shusterman

BruiserNeal ShustermanBruiser Rawlins isn’t simply a hulking teen; he is a true empath, able to literally take on the pains and illness of those he loves. He is able to drain off every cut, bruise, and broken heart, but the accumulation of suffering is physically killing him. How do you allow yourself to love someone if it could cost you your life? Author Neal Shusterman examines both the debilitating and healing aspects of being human.

Olive KitteredgeElizabeth Strout

Olive KitteredgeElizabeth StroutA Pulitzer Prize winner, and well-deserving. A collection of thirteen tales, each self-contained yet also part of the larger whole. Across these tales moves Olive Kitteredge, abrasive, opinionated, aloof. She is like a single-masted cutter cutting across people’s lives. She is difficult to get to know, yet her presence is pervasive and compelling; you feel her enter the room. Some people like her, others do not, but everyone has a grudging respect for her. As a writer, I soaked up every bit of author Elizabeth Strout’s language as a masterclass in prose. It is that good.

Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar ChildrenRansom Riggs

Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar ChildrenRansom RiggsDamn! I wish I’d thought of it first: a novel about children with peculiar abilities: a little girl capable of levitating, a boy with bees living in his chest, a girl able to conjure fire in her hands. What gives this novel a fascinating edge is that the author uses actual vintage photos to depict the characters. You get to see that levitating girl, and you’re left wondering what the back-story of the photo might be. Author Ransom Riggs gives his own explanations, as it were, in constructing a story against the backdrop of WWII. Great writing, great adventure. There are two more books in the series. I’ve just finished Hollow City and now need to get my hands on Library of Souls.

BonkMary Roach

BonkMary RoachMary Roach is one of my favorites. She takes the most unusual subjects and delves into their peculiar histories. Bonktackles the intersection of science and sex. I may have suffered a bit of squeamishness and (yes) prudery in reading the details of the various researches, but Roach knows exactly when to be scientific in her terminology and when to plop in the perfect analogy, all with her customary wit.

The rest of the 50 books:

Compulsion, Heidi AyarbeWaiting for Godot, Samnuel BeckettMcSweeeney’s Enchanted Chamber of Astonishing Stories, Michael Chabon, ed.Charles Dickens: The Last of the Great Men, G.K. ChesteronRunaway Ralph, Beverly ClearyGreat Short Works, Stephen CraneDombey and Son, Charles DickensHarlan Ellison’s Watching, Harlan EllisonShadow & Act Ralph EllisonThe Great Gatsby, F. Scott FitzgeraldThe Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor DostoyevskyMurder Boogies with Elvis, Anne GeorgeOld Yeller, Fred GipsonBlood Work, L.J. HaywardI’m with Stupid, Geoff HerbachNothing Special, Geoff HerbachSiddhartha, Herman HesseTilt, Ellen HopkinsThe Buried Giant, Kazuo IshiguroThe Jungle Books, Rudyard KiplingAn End to the Thrill, Varun KumarCreed, Trisha Leaver and Lindsay CurrieLet the Old Dreams Die, John Ajvide LindqvistA Game of Thrones, George R.R. MartinSomebody, Tell Me Who I Am, Harry MazerBilly Budd, Sailor, Herman MelvilleSchulz and Peanuts: A Biography, David MichaelisThe Book of Dragons, E. NesbitHollow City, Ransom RiggsDivergent, Veronica RothSt. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, Karen RussellBait, Alex SanchezA Journey to Matecumbe, Robert Lewis TaylorWalden, Henry David ThoreauNight, Elie WieselThe Midwich Cuckoos, John Wyndham

Published on January 03, 2016 10:14

December 30, 2015

First Draft, First Brain

For the last year I have been busy revising Reston Peace and finally feel that I have solid manuscript to shop around. Revising is my favorite part of writing; it can be both exhilarating and exasperating, combing through the text, unknotting tangles in the language, determining which scenes are tight and which are simply redundant. This is where the story truly takes shape, now that you have the whole in front of you, and you can figure out where there are gaps in the storytelling and where the characters burn with living passion.

Coming down off the revising phase and turning to face a new project, I always am flummoxed by the prospect of beginning a first draft. I forget how it’s done. I know it’s a messy process, and it requires an uncensored brain, but for the last twelve months I have been training my brain in a different direction. Revising is more analytical, while writing a first draft is more experimental.

Coming down off the revising phase and turning to face a new project, I always am flummoxed by the prospect of beginning a first draft. I forget how it’s done. I know it’s a messy process, and it requires an uncensored brain, but for the last twelve months I have been training my brain in a different direction. Revising is more analytical, while writing a first draft is more experimental.

Every writer has her own approach to writing, and though writers can come up with some inspirational quote to get you motivated, the sad, unhappy truth is that no one else is going to write your first draft for you. It is not a communal project. You don’t have a cheering crowd behind you, and you don’t get a gold star at the end of the day. Maybe if there were some accolades along the way, it wouldn’t feel quite so lonely, but I doubt anyone else’s praises are going to motivate me more than my own inner drive to create. Writing a first draft is like splattering paint on a canvas. That’s one of two images that often come to mind. I imagine dipping a brush into oil paint, getting the tip so saturated that by the time I bring it up to the canvas, a trail of droplets have already sprayed across the surface. I dip the brush into another color, then another, adding to the mess, until I’m ready for a break, and I can step back to see what forms and shapes are usable, and what is simply extraneous. I keep doing this for days and weeks, until eventually I get into a groove, and the paint tends to go where it needs to and less dribbles outside the margins. Subsequent drafts are about cleaning up those edges.

Writing a first draft is like splattering paint on a canvas. That’s one of two images that often come to mind. I imagine dipping a brush into oil paint, getting the tip so saturated that by the time I bring it up to the canvas, a trail of droplets have already sprayed across the surface. I dip the brush into another color, then another, adding to the mess, until I’m ready for a break, and I can step back to see what forms and shapes are usable, and what is simply extraneous. I keep doing this for days and weeks, until eventually I get into a groove, and the paint tends to go where it needs to and less dribbles outside the margins. Subsequent drafts are about cleaning up those edges.

The other image is the blunderbuss. I load a bunch of vocabulary, punctuation, concepts, images, a ephemera into the muzzle and let it blast at the page, and again I see what hits closest to the target and which pieces fly too wide.

Every project ends up requiring a slightly different approach. While there are certain things I always do, I do have to figure out what this draft specifically needs. Sometimes it takes pages and pages of writing to discover the narrator’s voice, even if it is a third-person narrator. Sometimes it takes careful planning of every last detail and loads of outlining before I can begin. Sometimes I simply have an image in my head and start there to see where it will lead. Always a story idea percolates for a very long time before I begin to write.

Every project ends up requiring a slightly different approach. While there are certain things I always do, I do have to figure out what this draft specifically needs. Sometimes it takes pages and pages of writing to discover the narrator’s voice, even if it is a third-person narrator. Sometimes it takes careful planning of every last detail and loads of outlining before I can begin. Sometimes I simply have an image in my head and start there to see where it will lead. Always a story idea percolates for a very long time before I begin to write.

For Dead Hungry, I had lots of scenarios but figuring out how they fitted together took some work. But it was always clear to me that the book would start with Freddie ranting about a really bad horror movie. I could see him hopping about in the traffic outside the movie theater like some latter-day Kevin McCarthy warning people that “They’re here, they’re here, you’re next!”

For Reston Peace, I wrote a very angry first draft twenty years ago. It started with Kenny’s car breaking down and rolling onto some railroad tracks, and he has to push it to safety. Then he is forced to walk home, and he gets a rock in his shoe, and he walks for miles before he bothers to take it out (symbolic of putting up with the pain in his life).

When I decided to rework the book, I decided to use a frame tale of Kenny as a forty-year-old looking back on the events of his younger self. It took a while to get his voice right because now he was no longer a twenty-year-old telling the story but someone with more insight. More than anything else, I had to reconsider the story I wanted to tell. The scenes from that original version eventually got whittled away until a completely new story took place. Overall, it still tells how Kenny deals with a history of sexual abuse, but the incidents are completely different.

When I decided to rework the book, I decided to use a frame tale of Kenny as a forty-year-old looking back on the events of his younger self. It took a while to get his voice right because now he was no longer a twenty-year-old telling the story but someone with more insight. More than anything else, I had to reconsider the story I wanted to tell. The scenes from that original version eventually got whittled away until a completely new story took place. Overall, it still tells how Kenny deals with a history of sexual abuse, but the incidents are completely different.

The one approach I always use is the quick review. I always reread what I wrote the day before and do a little tweaking of the language. I try not to get bogged down in revising or polishing, but rather I want to get back into the same frame of mind I was yesterday, but now I have a little more insight into what I’d written, and I can make it a smidge better, and that propels me into today’s writing. I also use word count goals for the day. It keeps me moving forward, even if every sentence seems like crap. Usually there is some nugget amidst the dross that is salvageable.

I’ve been working about a month on the first draft of a new novel, and yesterday was the first time I felt like I had made the shift back to first-draft mind. I didn’t care so much about the quality of the writing; I was more interested in the story I was telling. It was amazing how freeing it felt to reach this point, as though I had quieted the analytical revision-brain to tap into the more reptilian first-brain of creation. Let the lizard loose!

Okay, here’s an inspirational quote I can definitely get behind, from Stephen King:

Tell it, Stephen!“Writing isn’t about making money, getting famous, getting paid, getting laid, or making friends. In the end it’s about enriching the lives of those who will read your work, and enriching your own life as well. It’s about getting up, getting well, and getting over. Getting happy, okay? Getting happy … this book … is a permission slip: you can, you should, and if you’re brave enough to start, you will. Writing is magic, so much the water of life as any other creative art. The water is free. So drink. Drink and be filled up.” (Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Draft)

Tell it, Stephen!“Writing isn’t about making money, getting famous, getting paid, getting laid, or making friends. In the end it’s about enriching the lives of those who will read your work, and enriching your own life as well. It’s about getting up, getting well, and getting over. Getting happy, okay? Getting happy … this book … is a permission slip: you can, you should, and if you’re brave enough to start, you will. Writing is magic, so much the water of life as any other creative art. The water is free. So drink. Drink and be filled up.” (Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Draft)

Coming down off the revising phase and turning to face a new project, I always am flummoxed by the prospect of beginning a first draft. I forget how it’s done. I know it’s a messy process, and it requires an uncensored brain, but for the last twelve months I have been training my brain in a different direction. Revising is more analytical, while writing a first draft is more experimental.

Coming down off the revising phase and turning to face a new project, I always am flummoxed by the prospect of beginning a first draft. I forget how it’s done. I know it’s a messy process, and it requires an uncensored brain, but for the last twelve months I have been training my brain in a different direction. Revising is more analytical, while writing a first draft is more experimental.Every writer has her own approach to writing, and though writers can come up with some inspirational quote to get you motivated, the sad, unhappy truth is that no one else is going to write your first draft for you. It is not a communal project. You don’t have a cheering crowd behind you, and you don’t get a gold star at the end of the day. Maybe if there were some accolades along the way, it wouldn’t feel quite so lonely, but I doubt anyone else’s praises are going to motivate me more than my own inner drive to create.

Writing a first draft is like splattering paint on a canvas. That’s one of two images that often come to mind. I imagine dipping a brush into oil paint, getting the tip so saturated that by the time I bring it up to the canvas, a trail of droplets have already sprayed across the surface. I dip the brush into another color, then another, adding to the mess, until I’m ready for a break, and I can step back to see what forms and shapes are usable, and what is simply extraneous. I keep doing this for days and weeks, until eventually I get into a groove, and the paint tends to go where it needs to and less dribbles outside the margins. Subsequent drafts are about cleaning up those edges.

Writing a first draft is like splattering paint on a canvas. That’s one of two images that often come to mind. I imagine dipping a brush into oil paint, getting the tip so saturated that by the time I bring it up to the canvas, a trail of droplets have already sprayed across the surface. I dip the brush into another color, then another, adding to the mess, until I’m ready for a break, and I can step back to see what forms and shapes are usable, and what is simply extraneous. I keep doing this for days and weeks, until eventually I get into a groove, and the paint tends to go where it needs to and less dribbles outside the margins. Subsequent drafts are about cleaning up those edges.The other image is the blunderbuss. I load a bunch of vocabulary, punctuation, concepts, images, a ephemera into the muzzle and let it blast at the page, and again I see what hits closest to the target and which pieces fly too wide.

Every project ends up requiring a slightly different approach. While there are certain things I always do, I do have to figure out what this draft specifically needs. Sometimes it takes pages and pages of writing to discover the narrator’s voice, even if it is a third-person narrator. Sometimes it takes careful planning of every last detail and loads of outlining before I can begin. Sometimes I simply have an image in my head and start there to see where it will lead. Always a story idea percolates for a very long time before I begin to write.

Every project ends up requiring a slightly different approach. While there are certain things I always do, I do have to figure out what this draft specifically needs. Sometimes it takes pages and pages of writing to discover the narrator’s voice, even if it is a third-person narrator. Sometimes it takes careful planning of every last detail and loads of outlining before I can begin. Sometimes I simply have an image in my head and start there to see where it will lead. Always a story idea percolates for a very long time before I begin to write.For Dead Hungry, I had lots of scenarios but figuring out how they fitted together took some work. But it was always clear to me that the book would start with Freddie ranting about a really bad horror movie. I could see him hopping about in the traffic outside the movie theater like some latter-day Kevin McCarthy warning people that “They’re here, they’re here, you’re next!”

For Reston Peace, I wrote a very angry first draft twenty years ago. It started with Kenny’s car breaking down and rolling onto some railroad tracks, and he has to push it to safety. Then he is forced to walk home, and he gets a rock in his shoe, and he walks for miles before he bothers to take it out (symbolic of putting up with the pain in his life).

When I decided to rework the book, I decided to use a frame tale of Kenny as a forty-year-old looking back on the events of his younger self. It took a while to get his voice right because now he was no longer a twenty-year-old telling the story but someone with more insight. More than anything else, I had to reconsider the story I wanted to tell. The scenes from that original version eventually got whittled away until a completely new story took place. Overall, it still tells how Kenny deals with a history of sexual abuse, but the incidents are completely different.

When I decided to rework the book, I decided to use a frame tale of Kenny as a forty-year-old looking back on the events of his younger self. It took a while to get his voice right because now he was no longer a twenty-year-old telling the story but someone with more insight. More than anything else, I had to reconsider the story I wanted to tell. The scenes from that original version eventually got whittled away until a completely new story took place. Overall, it still tells how Kenny deals with a history of sexual abuse, but the incidents are completely different.The one approach I always use is the quick review. I always reread what I wrote the day before and do a little tweaking of the language. I try not to get bogged down in revising or polishing, but rather I want to get back into the same frame of mind I was yesterday, but now I have a little more insight into what I’d written, and I can make it a smidge better, and that propels me into today’s writing. I also use word count goals for the day. It keeps me moving forward, even if every sentence seems like crap. Usually there is some nugget amidst the dross that is salvageable.