Louis Arata's Blog, page 10

August 29, 2016

Book Review: Animal, Vegetable, Miracle

Bins of apples in a Chicago grocery store: Golden Delicious, Granny Smith, Jonagold. One bin contains apples all the way from New Zealand.

That’s an awfully long way for produce to travel, particularly when there are apple groves in Michigan, not that far from Chicago.

Though I’ve seen signs like this for years – produce from Brazil, Australia, California – I see them through a completely different lens since reading Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle.

For a year, Barbara Kingsolver and her husband and two daughters became locavores – eating food that is either grown on their own farm or is locally produced (the only exceptions are grains and oils). They also raised chickens primarily for eggs and an heirloom breed of turkey.

For a year, Barbara Kingsolver and her husband and two daughters became locavores – eating food that is either grown on their own farm or is locally produced (the only exceptions are grains and oils). They also raised chickens primarily for eggs and an heirloom breed of turkey.

One reason for their experiment was a growing consciousness of the many accepted norms in the food industry: animals pumped full of chemicals, genetically-modified plants sprayed with pesticides, and the fossil fuel cost for transporting to markets halfway round the world. Kingsolver and her family desired a closer association with the food they eat. They want to support local farmers, and by reducing their carbon footprint, they gradually learn to adjust to a new norm in their own lives. By spending more time together as a family in preparing food, they learn to enjoy the products of their hard work.

One of the largest obstacles is a shift in the mind-set that all food is readily available. We are a consumer culture that is losing its consciousness of where our meals come from. Several months ago I read an article about how apples are available all year round because they are kept in special storage units and treated with wax to reduce moisture loss. What eventually arrives in the market is an apple with minimal flavor and drastically reduced nutritional value.

Kingsolver starts off her paean with asparagus, which flowers early in spring. For two weeks, that is the family’s primary food source. So goes the seasons – tomatoes, peppers, and the overly enthusiastic zucchini. Kingsolver posits that if a vegetable is only available for a limited time each year, you will appreciate eating it all the more.

Trust me, don't name your food.Animal, Vegetable, Miracle reminds me a lot of Thoreau’s Walden. Kingsolver writes lovingly of every tender plant and fruit, the hard work that goes into growing it, but most of all the exquisite reward in experiencing the entire life cycle of the plant. So too with raising the turkeys, who need to learn and thing or two about the birds and the bees. Like Walden, Kingsolver covers all the seasons, finding beauty and magic in each one. There is the bounty of the fall harvest, but that doesn’t minimize the journey to get there.

Trust me, don't name your food.Animal, Vegetable, Miracle reminds me a lot of Thoreau’s Walden. Kingsolver writes lovingly of every tender plant and fruit, the hard work that goes into growing it, but most of all the exquisite reward in experiencing the entire life cycle of the plant. So too with raising the turkeys, who need to learn and thing or two about the birds and the bees. Like Walden, Kingsolver covers all the seasons, finding beauty and magic in each one. There is the bounty of the fall harvest, but that doesn’t minimize the journey to get there.

Throughout the book, Kingsolver’s husband, Steven L. Hopp, writes informative sidebars on local versus commercial produce, the cost of big business agriculture, and a variety of options for incorporating more local options into your diet. Their daughter Camille offers insights from a young adult’s perspective as well as many of the recipes they tried over the year.

I read the book over a two month period because I found that gave me time to absorb the wonders it offered. There is so much information here that it requires an open mind, and to rush through the work may have minimized its impact on me. When describing produce, a few times Kingsolver’s prose got a little too glorious – a shade short of purple. She is at her best when she tells personal stories, such as helping the turkeys learn how to mate. My favorite chapter covers Kingsolver and Hopp’s trip to Italy. My mouth was watering all the way through it.

That’s an awfully long way for produce to travel, particularly when there are apple groves in Michigan, not that far from Chicago.

Though I’ve seen signs like this for years – produce from Brazil, Australia, California – I see them through a completely different lens since reading Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle.

For a year, Barbara Kingsolver and her husband and two daughters became locavores – eating food that is either grown on their own farm or is locally produced (the only exceptions are grains and oils). They also raised chickens primarily for eggs and an heirloom breed of turkey.

For a year, Barbara Kingsolver and her husband and two daughters became locavores – eating food that is either grown on their own farm or is locally produced (the only exceptions are grains and oils). They also raised chickens primarily for eggs and an heirloom breed of turkey. One reason for their experiment was a growing consciousness of the many accepted norms in the food industry: animals pumped full of chemicals, genetically-modified plants sprayed with pesticides, and the fossil fuel cost for transporting to markets halfway round the world. Kingsolver and her family desired a closer association with the food they eat. They want to support local farmers, and by reducing their carbon footprint, they gradually learn to adjust to a new norm in their own lives. By spending more time together as a family in preparing food, they learn to enjoy the products of their hard work.

One of the largest obstacles is a shift in the mind-set that all food is readily available. We are a consumer culture that is losing its consciousness of where our meals come from. Several months ago I read an article about how apples are available all year round because they are kept in special storage units and treated with wax to reduce moisture loss. What eventually arrives in the market is an apple with minimal flavor and drastically reduced nutritional value.

Kingsolver starts off her paean with asparagus, which flowers early in spring. For two weeks, that is the family’s primary food source. So goes the seasons – tomatoes, peppers, and the overly enthusiastic zucchini. Kingsolver posits that if a vegetable is only available for a limited time each year, you will appreciate eating it all the more.

Trust me, don't name your food.Animal, Vegetable, Miracle reminds me a lot of Thoreau’s Walden. Kingsolver writes lovingly of every tender plant and fruit, the hard work that goes into growing it, but most of all the exquisite reward in experiencing the entire life cycle of the plant. So too with raising the turkeys, who need to learn and thing or two about the birds and the bees. Like Walden, Kingsolver covers all the seasons, finding beauty and magic in each one. There is the bounty of the fall harvest, but that doesn’t minimize the journey to get there.

Trust me, don't name your food.Animal, Vegetable, Miracle reminds me a lot of Thoreau’s Walden. Kingsolver writes lovingly of every tender plant and fruit, the hard work that goes into growing it, but most of all the exquisite reward in experiencing the entire life cycle of the plant. So too with raising the turkeys, who need to learn and thing or two about the birds and the bees. Like Walden, Kingsolver covers all the seasons, finding beauty and magic in each one. There is the bounty of the fall harvest, but that doesn’t minimize the journey to get there.Throughout the book, Kingsolver’s husband, Steven L. Hopp, writes informative sidebars on local versus commercial produce, the cost of big business agriculture, and a variety of options for incorporating more local options into your diet. Their daughter Camille offers insights from a young adult’s perspective as well as many of the recipes they tried over the year.

I read the book over a two month period because I found that gave me time to absorb the wonders it offered. There is so much information here that it requires an open mind, and to rush through the work may have minimized its impact on me. When describing produce, a few times Kingsolver’s prose got a little too glorious – a shade short of purple. She is at her best when she tells personal stories, such as helping the turkeys learn how to mate. My favorite chapter covers Kingsolver and Hopp’s trip to Italy. My mouth was watering all the way through it.

Published on August 29, 2016 07:33

August 17, 2016

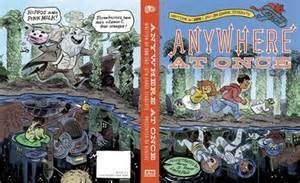

Book Review: Anywhere At Once

A girl who builds robots. A boy who grows Brussels sprouts. A lizard who invents technology. And a crabby villain whose superpower is useless facts and a penchant for throwing cakes.

That is the cast assembled by 106 Chicago students, 2nd through 8th grade. Under the guidance of volunteers from 826CHI, these writers have created a series of adventures and misadventures ranging across unusual islands, outer space, and a cardboard factory.

826CHI is the Chicago branch of Dave Eggers’ 826 National, a non-profit tutoring, writing, and publishing organization. The volunteers visited classrooms across Chicago to elicit stories, characters, and plot from more than 700 students. Then they honed down the stories to the collection in Anywhere At Once.

The adventures are full of kid logic. When Ophelia needs to make spaghetti for her brothers and sisters, she builds a spaghetti-making robot. When Sam wants to dodge his chores tending fields of Brussels sprouts, he finds a circus-filled island. When Dr Stephen Scalious wants to escape his aquarium in a Wisconsin zoo (he’s a lizard), he builds a tunnel-digging machine. The wonderful beauty of kid logic is that if a story needs something, it’s there. No need to explain where a lizard finds the parts to build his marvelous machines; he simply has them. It’s amazing how much impressive technology can be built from cardboard.

There isn’t an overall plot to Anywhere At Once. It’s more of a series of escapades ranging from visiting outer space, discovering an island made of chocolate, and time-traveling. The villain of the piece – the crabby William Harold James Boogledorf III – isn’t terribly villainous either. He doesn’t hatch any nefarious plans, other than to irritate the three heroes.

To compose the novel, each student writes a separate chapter, so they must build on what’s come before. If one writer describes how Sam hates Brussels sprouts, then all subsequent chapters must include that. If one chapter addresses how Dr Stephen Scalious doesn’t like strawberries, then another must have that Boogledorf clobbers him with a strawberry cake.

These authors have a flare for storytelling. There is energy, creativity, and playfulness in the individual styles, as well as moments of poignancy, and lots on the power of friendship. There is both a cohesive quality to the story as well as a looseness that makes it feel like anything can happen, and it often does.

The communal effort in storytelling doesn’t end with the last chapter. The novel ends with blank pages to encourage readers to come up with the next episode in Ophelia, Sam, and Stephen’s adventures.

The greatest lesson I learned from Anywhere At Once is that storytelling allows for anything to happen. Sometimes I get tied up in knots trying to prove the logic of a situation in a story, but these young authors show me how it’s done. You don’t have to get bogged down in the details. If your story needs a spaghetti-making robot, you just make it so. Readers are willing to fill in the gaps so long as the writing engages them. And these 700+ Chicago students who contributed to this 826CHI project definitely know how to keep things engaging.

That is the cast assembled by 106 Chicago students, 2nd through 8th grade. Under the guidance of volunteers from 826CHI, these writers have created a series of adventures and misadventures ranging across unusual islands, outer space, and a cardboard factory.

826CHI is the Chicago branch of Dave Eggers’ 826 National, a non-profit tutoring, writing, and publishing organization. The volunteers visited classrooms across Chicago to elicit stories, characters, and plot from more than 700 students. Then they honed down the stories to the collection in Anywhere At Once.

The adventures are full of kid logic. When Ophelia needs to make spaghetti for her brothers and sisters, she builds a spaghetti-making robot. When Sam wants to dodge his chores tending fields of Brussels sprouts, he finds a circus-filled island. When Dr Stephen Scalious wants to escape his aquarium in a Wisconsin zoo (he’s a lizard), he builds a tunnel-digging machine. The wonderful beauty of kid logic is that if a story needs something, it’s there. No need to explain where a lizard finds the parts to build his marvelous machines; he simply has them. It’s amazing how much impressive technology can be built from cardboard.

There isn’t an overall plot to Anywhere At Once. It’s more of a series of escapades ranging from visiting outer space, discovering an island made of chocolate, and time-traveling. The villain of the piece – the crabby William Harold James Boogledorf III – isn’t terribly villainous either. He doesn’t hatch any nefarious plans, other than to irritate the three heroes.

To compose the novel, each student writes a separate chapter, so they must build on what’s come before. If one writer describes how Sam hates Brussels sprouts, then all subsequent chapters must include that. If one chapter addresses how Dr Stephen Scalious doesn’t like strawberries, then another must have that Boogledorf clobbers him with a strawberry cake.

These authors have a flare for storytelling. There is energy, creativity, and playfulness in the individual styles, as well as moments of poignancy, and lots on the power of friendship. There is both a cohesive quality to the story as well as a looseness that makes it feel like anything can happen, and it often does.

The communal effort in storytelling doesn’t end with the last chapter. The novel ends with blank pages to encourage readers to come up with the next episode in Ophelia, Sam, and Stephen’s adventures.

The greatest lesson I learned from Anywhere At Once is that storytelling allows for anything to happen. Sometimes I get tied up in knots trying to prove the logic of a situation in a story, but these young authors show me how it’s done. You don’t have to get bogged down in the details. If your story needs a spaghetti-making robot, you just make it so. Readers are willing to fill in the gaps so long as the writing engages them. And these 700+ Chicago students who contributed to this 826CHI project definitely know how to keep things engaging.

Published on August 17, 2016 06:13

July 22, 2016

Book Review: The Memory Keeper's Daughter

“A moment might be a thousand different things.”

In The Memory Keeper’s Daughter, every present moment is composed of layers of the past, like a gauze veil that obstructs sight. A moment is composed of infinite perspectives, not only of those involved, but even for an individual who sees all the preceding events that have led to this place and time.

Kim Edwards’ novel has an intriguing premise. On a snowy night, Dr. David Henry delivers his own twins – a boy and a girl. He quickly realizes that while his son Paul is healthy, Phoebe exhibits signs of Down syndrome. Fearing that his daughter doesn’t stand a chance of a normal life, and endeavoring to protect his wife Norah from future heartache, he impulsively hands over Phoebe to his nurse Caroline with instructions to take her to a nearby institution. To his wife, he fabricates a story that Phoebe has died in birth. But his nurse Caroline cannot abide leaving the child at the home, so she flees into the night, determining to raise the child as her own. Over the course of the novel, the consequences of this single act unfold. While David and Norah raise Paul, Caroline builds a home for Phoebe.

Kim Edwards’ novel has an intriguing premise. On a snowy night, Dr. David Henry delivers his own twins – a boy and a girl. He quickly realizes that while his son Paul is healthy, Phoebe exhibits signs of Down syndrome. Fearing that his daughter doesn’t stand a chance of a normal life, and endeavoring to protect his wife Norah from future heartache, he impulsively hands over Phoebe to his nurse Caroline with instructions to take her to a nearby institution. To his wife, he fabricates a story that Phoebe has died in birth. But his nurse Caroline cannot abide leaving the child at the home, so she flees into the night, determining to raise the child as her own. Over the course of the novel, the consequences of this single act unfold. While David and Norah raise Paul, Caroline builds a home for Phoebe.

I love novels that examine the repercussions of decisions – how a single act can impact so many separate lives. It reminds me that life is sometimes composed of chaotic and coincidental threads that keep us connected.

Unfortunately, The Memory Keeper’s Daughter rarely lives up to its potential. The plot relies on a predictable series of events – marital discontent, affairs, troubled youth – so that the characters can spend plenty of time ruminating about the past. These events are supposed to be symptoms of a deeper problem, but they often feel like convenient shorthand rather than actual consequences of David’s decision. There’s trouble in a marriage, so of course one of the partners turns to an affair. There’s trouble between a father and son, so of course the son tries drugs.

Edwards examines the internal lives of her characters in careful detail, but to do so she relies on convenient solutions to plot problems. Despite the emotional turmoil they endure, somehow things sort of work themselves out.

For example, Caroline is a single mother raising a daughter with Down syndrome. She manages to get a job as a home caretaker to a crotchety old man and his more benevolent daughter. After the old man dies, Caroline continues to live with the daughter, and when the daughter eventually retires, she signs over the deed of the house. In other words, the daughter is a benefactor because that conveniently allows Caroline to get a home.

In another sequence, Dr David Henry returns to his childhood home, only to find a pregnant teenager squatting on the premises. He takes her home, helps her raise her son, and even though this is the final straw in his fracturing marriage, somehow Norah never manages to press him on his reasons for doing this. The marriage falls apart, and David is free to be the benefactor to this young girl, and somehow there are no explosions, no real repercussions. The characters go on with their lives without ever challenging the status quo.

In another sequence, Dr David Henry returns to his childhood home, only to find a pregnant teenager squatting on the premises. He takes her home, helps her raise her son, and even though this is the final straw in his fracturing marriage, somehow Norah never manages to press him on his reasons for doing this. The marriage falls apart, and David is free to be the benefactor to this young girl, and somehow there are no explosions, no real repercussions. The characters go on with their lives without ever challenging the status quo.

The theme of the novel, of course, is the pervasive nature of memory. The author chooses to examine in minute detail what the characters are feeling, without ever giving them the freedom to bridge the gaps in their lives. It’s like life is one long flashback sequence. In one scene at his son’s birthday party, David indulges in a memory:

“I suppose this is it, his father had said, slamming the truck door and standing on the curb by the bus stop on the day David left for Pittsburgh. I suppose this is the last we can expect to hear from you, moving up in the world and all. You won’t have time for the likes of us anymore. And David, standing on the curb with early leaves falling down around him, had felt a deep sense of desperation, because even then he sensed the truth of his father’s words: whatever his own intentions were, however much he loved them, his life would carry him away.”

In the next sentence, someone pulls David back to the present: ‘Are you all right, David?’ Kay Marshall asked. She was walking by, carrying a vase of pale pink tulips, each petal as delicate as the edge of a lung. ‘You look a million miles away.’” (p. 148)

This happens an awful lot throughout the book: a character disappears into a memory, and it’s like the whole story comes to a halt while the flashback unfolds. When Paul is examining his father’s boxes of photographs, one of his friends interrupt him: “’You ever coming out, or what?’” I felt like asking that a lot.

Ultimately, I was pretty frustrated with the book. Maybe it was because my expectations were not met. Given that the title refers to the daughter, I figured Phoebe would be more of a central character, but she is kept mostly to the sidelines. She comes across as a symbol rather than a fully realized character.

Clearly there was a lot of potential there, and certainly plenty of beautifully composed scenes of grief and loss. But the contrived nature of the plot left me wishing that more unexpected chances had been taken. Maybe the author wants to suggest that certain actions call forth specific ends, but I think that a little variety in the choices that were made could still have resulted in the ending that she constructed.

Maybe a moment is a thousand different things, but this novel focuses predominantly on one thing: memory, rather than the present, is where we live.

In The Memory Keeper’s Daughter, every present moment is composed of layers of the past, like a gauze veil that obstructs sight. A moment is composed of infinite perspectives, not only of those involved, but even for an individual who sees all the preceding events that have led to this place and time.

Kim Edwards’ novel has an intriguing premise. On a snowy night, Dr. David Henry delivers his own twins – a boy and a girl. He quickly realizes that while his son Paul is healthy, Phoebe exhibits signs of Down syndrome. Fearing that his daughter doesn’t stand a chance of a normal life, and endeavoring to protect his wife Norah from future heartache, he impulsively hands over Phoebe to his nurse Caroline with instructions to take her to a nearby institution. To his wife, he fabricates a story that Phoebe has died in birth. But his nurse Caroline cannot abide leaving the child at the home, so she flees into the night, determining to raise the child as her own. Over the course of the novel, the consequences of this single act unfold. While David and Norah raise Paul, Caroline builds a home for Phoebe.

Kim Edwards’ novel has an intriguing premise. On a snowy night, Dr. David Henry delivers his own twins – a boy and a girl. He quickly realizes that while his son Paul is healthy, Phoebe exhibits signs of Down syndrome. Fearing that his daughter doesn’t stand a chance of a normal life, and endeavoring to protect his wife Norah from future heartache, he impulsively hands over Phoebe to his nurse Caroline with instructions to take her to a nearby institution. To his wife, he fabricates a story that Phoebe has died in birth. But his nurse Caroline cannot abide leaving the child at the home, so she flees into the night, determining to raise the child as her own. Over the course of the novel, the consequences of this single act unfold. While David and Norah raise Paul, Caroline builds a home for Phoebe.I love novels that examine the repercussions of decisions – how a single act can impact so many separate lives. It reminds me that life is sometimes composed of chaotic and coincidental threads that keep us connected.

Unfortunately, The Memory Keeper’s Daughter rarely lives up to its potential. The plot relies on a predictable series of events – marital discontent, affairs, troubled youth – so that the characters can spend plenty of time ruminating about the past. These events are supposed to be symptoms of a deeper problem, but they often feel like convenient shorthand rather than actual consequences of David’s decision. There’s trouble in a marriage, so of course one of the partners turns to an affair. There’s trouble between a father and son, so of course the son tries drugs.

Edwards examines the internal lives of her characters in careful detail, but to do so she relies on convenient solutions to plot problems. Despite the emotional turmoil they endure, somehow things sort of work themselves out.

For example, Caroline is a single mother raising a daughter with Down syndrome. She manages to get a job as a home caretaker to a crotchety old man and his more benevolent daughter. After the old man dies, Caroline continues to live with the daughter, and when the daughter eventually retires, she signs over the deed of the house. In other words, the daughter is a benefactor because that conveniently allows Caroline to get a home.

In another sequence, Dr David Henry returns to his childhood home, only to find a pregnant teenager squatting on the premises. He takes her home, helps her raise her son, and even though this is the final straw in his fracturing marriage, somehow Norah never manages to press him on his reasons for doing this. The marriage falls apart, and David is free to be the benefactor to this young girl, and somehow there are no explosions, no real repercussions. The characters go on with their lives without ever challenging the status quo.

In another sequence, Dr David Henry returns to his childhood home, only to find a pregnant teenager squatting on the premises. He takes her home, helps her raise her son, and even though this is the final straw in his fracturing marriage, somehow Norah never manages to press him on his reasons for doing this. The marriage falls apart, and David is free to be the benefactor to this young girl, and somehow there are no explosions, no real repercussions. The characters go on with their lives without ever challenging the status quo.The theme of the novel, of course, is the pervasive nature of memory. The author chooses to examine in minute detail what the characters are feeling, without ever giving them the freedom to bridge the gaps in their lives. It’s like life is one long flashback sequence. In one scene at his son’s birthday party, David indulges in a memory:

“I suppose this is it, his father had said, slamming the truck door and standing on the curb by the bus stop on the day David left for Pittsburgh. I suppose this is the last we can expect to hear from you, moving up in the world and all. You won’t have time for the likes of us anymore. And David, standing on the curb with early leaves falling down around him, had felt a deep sense of desperation, because even then he sensed the truth of his father’s words: whatever his own intentions were, however much he loved them, his life would carry him away.”

In the next sentence, someone pulls David back to the present: ‘Are you all right, David?’ Kay Marshall asked. She was walking by, carrying a vase of pale pink tulips, each petal as delicate as the edge of a lung. ‘You look a million miles away.’” (p. 148)

This happens an awful lot throughout the book: a character disappears into a memory, and it’s like the whole story comes to a halt while the flashback unfolds. When Paul is examining his father’s boxes of photographs, one of his friends interrupt him: “’You ever coming out, or what?’” I felt like asking that a lot.

Ultimately, I was pretty frustrated with the book. Maybe it was because my expectations were not met. Given that the title refers to the daughter, I figured Phoebe would be more of a central character, but she is kept mostly to the sidelines. She comes across as a symbol rather than a fully realized character.

Clearly there was a lot of potential there, and certainly plenty of beautifully composed scenes of grief and loss. But the contrived nature of the plot left me wishing that more unexpected chances had been taken. Maybe the author wants to suggest that certain actions call forth specific ends, but I think that a little variety in the choices that were made could still have resulted in the ending that she constructed.

Maybe a moment is a thousand different things, but this novel focuses predominantly on one thing: memory, rather than the present, is where we live.

Published on July 22, 2016 09:38

July 4, 2016

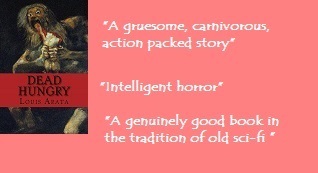

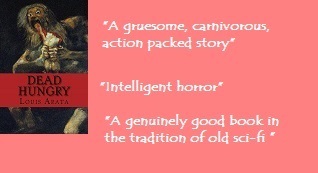

Smashwords July Sale: Dead Hungry

Ghouls don't come anymore free than this!

Dead Hungry is free at Smashwords.

July Summer/Winter Sale

Click on the link: DEAD HUNGRY

Use Promo Code SFREE at checkout

Dead Hungry is free at Smashwords.

July Summer/Winter Sale

Click on the link: DEAD HUNGRY

Use Promo Code SFREE at checkout

Published on July 04, 2016 13:50

June 21, 2016

Book Review: Private Life

Reading Jane Smiley is always a cause for anticipation. I never know quite what to expect when I pick up one of her books, other than that I will be enriched. The thing is each of her novels is distinctive. A Thousand Acres feels vastly different than Horse Heaven, which is radically different than Barn Blind or The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton.

And that is a remarkable feat for a writer: to develop a recognizable voice and yet to perpetually surprise the reader with fresh storylines and undiscovered territories.

I’m gearing up for her recent trilogy: The Last Hundred Years, which includes Some Luck (2014), Early Warning (2015), and Golden Age(2015). So, as an hors d’oeuvre, I picked up Private Life, her 2010 novel about a turn of the 20th century woman whose comprehension for how the world and the universe works expands through the trials of her marriage.

Private Life is a historical novel, only in the sense that it takes place from the 1880s through the 1940s, so historical events are part of the backdrop (the San Francisco earthquake, the stock market crash, World Wars I and II). There is also a scrim of scientific history, with questions on the nature of the universe, how the moon came into being, and whether Einstein’s Theory of Relativity should be challenged or accepted.

Private Life is a historical novel, only in the sense that it takes place from the 1880s through the 1940s, so historical events are part of the backdrop (the San Francisco earthquake, the stock market crash, World Wars I and II). There is also a scrim of scientific history, with questions on the nature of the universe, how the moon came into being, and whether Einstein’s Theory of Relativity should be challenged or accepted.

It is through this scrim that we witness the cognitive birth of Margaret Mayfield. The eldest of three sisters, she is the last to marry and the first to ponder what it all means. Her marriage to Andrew Jackson Jefferson Early, a naval officer and astronomer, is certainly not made of passion. Rather, it happens because society expects it to.

What is the center of

What is the center of

your universe?For years, Margaret remains the dutiful wife, typing Andrew’s manuscripts and supporting his questionable scientific conclusions. She wants him to succeed because it’s what he desperately needs. Yet as Margaret’s circle of friends expands, she begins to recognize that Andrew may not be the center of her universe. She watches her friend Dora tramp off to Europe to cover the war. She befriends a Japanese midwife and her artist husband. She wrangles with the dubious past of a disposed Russian.

As Andrew wrestles with how and why the universe operates the way that it does, his theories come apart. He becomes increasingly controlling of Margaret’s freedoms, not in a tyrannical manner but rather through an oppressively rationalistic authority that smothers Margaret’s sense of identity. She is witness to a shifting and changing world, while Andrew demands that there be one answer to the ultimate question of the universe, even if he can’t articulate what that might be. In many ways, there relationship is reminiscent of Dorothea and Casaubon in George Eliot's Middlemarch.

Smiley’s novel is fascinating and heartbreaking. Its core is Margaret’s internal life: her observations are keen and curious and often unspoken, so that she remains sheltered from her family and friends. She doesn’t allow much emotional connection, even with those she is closest to, yet you can sense how important these people are to her world.

When I started reading Private Life, I wasn’t quite sure what to make of it. The plot unfolds as though it is slowly coming awake. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; Smiley’s prose is rich and should be savored. Yet I can’t say that I found it compelling enough to race through. Still, I remained curious to find where Margaret’s life was heading. Once I caught on that this was a novel of slow discovery, I allowed myself to sink into it, and in some ways I dreaded reaching the end when the story (and Margaret) would be fully awake. Not surprisingly, Smiley pulls off a realistically nuanced conclusion that leaves a sense of bitter anticipation in Margaret’s future.

Private Life is not my favorite Smiley (Horse Heaven holds that position), yet it is a masterclass in writing by a fine novelist.

And that is a remarkable feat for a writer: to develop a recognizable voice and yet to perpetually surprise the reader with fresh storylines and undiscovered territories.

I’m gearing up for her recent trilogy: The Last Hundred Years, which includes Some Luck (2014), Early Warning (2015), and Golden Age(2015). So, as an hors d’oeuvre, I picked up Private Life, her 2010 novel about a turn of the 20th century woman whose comprehension for how the world and the universe works expands through the trials of her marriage.

Private Life is a historical novel, only in the sense that it takes place from the 1880s through the 1940s, so historical events are part of the backdrop (the San Francisco earthquake, the stock market crash, World Wars I and II). There is also a scrim of scientific history, with questions on the nature of the universe, how the moon came into being, and whether Einstein’s Theory of Relativity should be challenged or accepted.

Private Life is a historical novel, only in the sense that it takes place from the 1880s through the 1940s, so historical events are part of the backdrop (the San Francisco earthquake, the stock market crash, World Wars I and II). There is also a scrim of scientific history, with questions on the nature of the universe, how the moon came into being, and whether Einstein’s Theory of Relativity should be challenged or accepted.It is through this scrim that we witness the cognitive birth of Margaret Mayfield. The eldest of three sisters, she is the last to marry and the first to ponder what it all means. Her marriage to Andrew Jackson Jefferson Early, a naval officer and astronomer, is certainly not made of passion. Rather, it happens because society expects it to.

What is the center of

What is the center of your universe?For years, Margaret remains the dutiful wife, typing Andrew’s manuscripts and supporting his questionable scientific conclusions. She wants him to succeed because it’s what he desperately needs. Yet as Margaret’s circle of friends expands, she begins to recognize that Andrew may not be the center of her universe. She watches her friend Dora tramp off to Europe to cover the war. She befriends a Japanese midwife and her artist husband. She wrangles with the dubious past of a disposed Russian.

As Andrew wrestles with how and why the universe operates the way that it does, his theories come apart. He becomes increasingly controlling of Margaret’s freedoms, not in a tyrannical manner but rather through an oppressively rationalistic authority that smothers Margaret’s sense of identity. She is witness to a shifting and changing world, while Andrew demands that there be one answer to the ultimate question of the universe, even if he can’t articulate what that might be. In many ways, there relationship is reminiscent of Dorothea and Casaubon in George Eliot's Middlemarch.

Smiley’s novel is fascinating and heartbreaking. Its core is Margaret’s internal life: her observations are keen and curious and often unspoken, so that she remains sheltered from her family and friends. She doesn’t allow much emotional connection, even with those she is closest to, yet you can sense how important these people are to her world.

When I started reading Private Life, I wasn’t quite sure what to make of it. The plot unfolds as though it is slowly coming awake. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; Smiley’s prose is rich and should be savored. Yet I can’t say that I found it compelling enough to race through. Still, I remained curious to find where Margaret’s life was heading. Once I caught on that this was a novel of slow discovery, I allowed myself to sink into it, and in some ways I dreaded reaching the end when the story (and Margaret) would be fully awake. Not surprisingly, Smiley pulls off a realistically nuanced conclusion that leaves a sense of bitter anticipation in Margaret’s future.

Private Life is not my favorite Smiley (Horse Heaven holds that position), yet it is a masterclass in writing by a fine novelist.

Published on June 21, 2016 07:46

June 10, 2016

Book Review: The Eyre Affair

Fifteen years ago I was browsing a bookstore and found an intriguing detective novel in which someone is kidnapping characters from literature. The concept tickled me, but due to some lapse of judgment, I put the book back and went back to browsing.

Then I forgot the title, and since then I’ve been kicking myself for not buying it when I had the chance.

Recently GoodReads recommended to me Jasper Fforde’s The Eyre Affair. This was it! The book! So I nabbed a copy of it and read it over vacation. It was worth the wait.

In a surreal world, the Crimean War is still in full swing in 1985, and militant gangs proselytize that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare’s plays, and dressing up as John Milton at conventions is the height of cosplay. Thursday Next is a special operative in the LiteraTec division, which tracks down criminals in the high-stakes world of literary forgeries. When a criminal mastermind Hades Acheron literally kidnaps Jane Eyre from the novel, it is up to Thursday to jump into the Bronte world, and with the aid of Rochester, keep the story from being derailed into nonexistence.

Thursday Next is a special operative in the LiteraTec division, which tracks down criminals in the high-stakes world of literary forgeries. When a criminal mastermind Hades Acheron literally kidnaps Jane Eyre from the novel, it is up to Thursday to jump into the Bronte world, and with the aid of Rochester, keep the story from being derailed into nonexistence.

The story is rife with cleverness, but if all it had to offer was a clever premise, the book wouldn’t have been worth the trouble. Fortunately Fford knows how to tell a great story.

"Yes, I named one of the

"Yes, I named one of the

characters Paige Turner."A veteran of the Crimean War, Thursday has the emotional scars of battle as well as the death of her brother, due to a military blunder for which he is held responsible. Fifteen years later, she is still haunted by the past. She is an exceptional operative, though lately she is craving a quieter existence, so she returns to her hometown. Unfortunately, Hades Acheron has other plans, and soon Thursday is embroiled in tracking him down.

Fford relies on the reader having a certain degree of familiarity with Bronte’s novel, but he judiciously uses only select scenes from the novel rather than trying to cover the entire scope of Jane Eyre. Also, so he can focus on Thursday’s story, he keeps Jane out of the action until the second half of the novel. It’s a smart move that keeps the reader eager for Jane’s eventual appearance rather than jumping too quickly to the novelty of the premise.

There are plenty more books in the Thursday Next series, and from the blurbs, it looks like Fford is eager to explore the breadth of his world rather than repeating the whole literary kidnapping storyline.

Then I forgot the title, and since then I’ve been kicking myself for not buying it when I had the chance.

Recently GoodReads recommended to me Jasper Fforde’s The Eyre Affair. This was it! The book! So I nabbed a copy of it and read it over vacation. It was worth the wait.

In a surreal world, the Crimean War is still in full swing in 1985, and militant gangs proselytize that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare’s plays, and dressing up as John Milton at conventions is the height of cosplay.

Thursday Next is a special operative in the LiteraTec division, which tracks down criminals in the high-stakes world of literary forgeries. When a criminal mastermind Hades Acheron literally kidnaps Jane Eyre from the novel, it is up to Thursday to jump into the Bronte world, and with the aid of Rochester, keep the story from being derailed into nonexistence.

Thursday Next is a special operative in the LiteraTec division, which tracks down criminals in the high-stakes world of literary forgeries. When a criminal mastermind Hades Acheron literally kidnaps Jane Eyre from the novel, it is up to Thursday to jump into the Bronte world, and with the aid of Rochester, keep the story from being derailed into nonexistence.The story is rife with cleverness, but if all it had to offer was a clever premise, the book wouldn’t have been worth the trouble. Fortunately Fford knows how to tell a great story.

"Yes, I named one of the

"Yes, I named one of thecharacters Paige Turner."A veteran of the Crimean War, Thursday has the emotional scars of battle as well as the death of her brother, due to a military blunder for which he is held responsible. Fifteen years later, she is still haunted by the past. She is an exceptional operative, though lately she is craving a quieter existence, so she returns to her hometown. Unfortunately, Hades Acheron has other plans, and soon Thursday is embroiled in tracking him down.

Fford relies on the reader having a certain degree of familiarity with Bronte’s novel, but he judiciously uses only select scenes from the novel rather than trying to cover the entire scope of Jane Eyre. Also, so he can focus on Thursday’s story, he keeps Jane out of the action until the second half of the novel. It’s a smart move that keeps the reader eager for Jane’s eventual appearance rather than jumping too quickly to the novelty of the premise.

There are plenty more books in the Thursday Next series, and from the blurbs, it looks like Fford is eager to explore the breadth of his world rather than repeating the whole literary kidnapping storyline.

Published on June 10, 2016 09:13

May 17, 2016

Making a Run at It

In the TV show Ninja Warrior, athletes compete on a four-stage obstacle course. Some obstacles include log rolls, spider climbs, and a salmon ladder, in which you hang from a bar and must jump the bar up a series of notches until you reach the top of the ladder. At the beginning of each game, there are a hundred competitors, but most wipe out fairly early, and often times no one reaches the fourth stage. To give you an idea of how tough it is – Olympic athletes have not been able to complete the course.

Certainly strength is essential in making it through the course; the athletes have to possess phenomenal body strength to haul themselves up and over objects or cling to narrow ledges with their fingertips. But there is also a mental factor, and throughout the course you can see athletes pause to calculate the best possible approach.

This usually occurs at the warped wall, a 14-foot barrier that the competitors must scale. They have to make a run up a short slope with enough momentum to leap and catch the top of the wall. Typically it takes two or three tries before they get it; then they have to pull themselves up and over before moving on to the next challenge.

barrier that the competitors must scale. They have to make a run up a short slope with enough momentum to leap and catch the top of the wall. Typically it takes two or three tries before they get it; then they have to pull themselves up and over before moving on to the next challenge.

It’s always at the warped wall when I start to get tense (watching it. I doubt I could do it) because the athletes are losing precious seconds while they gauge their approach. And usually you can tell as soon as they take off whether or not they will make it. There’s something about their plosive momentum that forecasts whether they have made the best calculation.

Tackling a new story is like scaling the warped wall.

I’m standing here with my story plans right in front of me, a humongous barrier, and I know once I scale it, I will be off and running.

In my eagerness to get writing, I launch myself at the wall and get only so far up before I realize I can’t reach the top. So, I slide back down and reconsider my approach. Some approaches get me closer to the top, but typically I have to make a run at it several times again.

This may not be the best writing practice out there. It consumes a lot of time making failed approaches at the plot. The story hasn’t changed; I know what I want to write, but the problem is figuring out the best way to get into the story … on the other side of the wall.

When I was working on Dead Hungry, I wrote and rewrote the first nine chapters probably six or seven times. The events in the chapters didn’t change much, but how I went about building the scenes did. And while I had my cast of characters right from the beginning, they needed time to show me who they were.

So, now I’m back at the first draft of another novel, and again I can see the story I want to tell, but I’m having difficulty scaling that warped wall. I’ve made three separate approaches so far, and none of them has quite worked. What usually happens is that the story loses momentum and eventually stalls. And if I’m losing interest in it, there is no way I can convince readers to keep going.

This morning I woke before the alarm and tried looking at the story from a new angle. I’m not quite convinced that this will be the strategy to get me over the wall. What I have to trust, though, is that this is part of my writing process. And the obstacle is going to remain there until I figure out how to scale it.

It’s time to take a step back to the beginning of the slope. My next run at it might be the one I need to get over.

Certainly strength is essential in making it through the course; the athletes have to possess phenomenal body strength to haul themselves up and over objects or cling to narrow ledges with their fingertips. But there is also a mental factor, and throughout the course you can see athletes pause to calculate the best possible approach.

This usually occurs at the warped wall, a 14-foot

barrier that the competitors must scale. They have to make a run up a short slope with enough momentum to leap and catch the top of the wall. Typically it takes two or three tries before they get it; then they have to pull themselves up and over before moving on to the next challenge.

barrier that the competitors must scale. They have to make a run up a short slope with enough momentum to leap and catch the top of the wall. Typically it takes two or three tries before they get it; then they have to pull themselves up and over before moving on to the next challenge.It’s always at the warped wall when I start to get tense (watching it. I doubt I could do it) because the athletes are losing precious seconds while they gauge their approach. And usually you can tell as soon as they take off whether or not they will make it. There’s something about their plosive momentum that forecasts whether they have made the best calculation.

Tackling a new story is like scaling the warped wall.

I’m standing here with my story plans right in front of me, a humongous barrier, and I know once I scale it, I will be off and running.

In my eagerness to get writing, I launch myself at the wall and get only so far up before I realize I can’t reach the top. So, I slide back down and reconsider my approach. Some approaches get me closer to the top, but typically I have to make a run at it several times again.

This may not be the best writing practice out there. It consumes a lot of time making failed approaches at the plot. The story hasn’t changed; I know what I want to write, but the problem is figuring out the best way to get into the story … on the other side of the wall.

When I was working on Dead Hungry, I wrote and rewrote the first nine chapters probably six or seven times. The events in the chapters didn’t change much, but how I went about building the scenes did. And while I had my cast of characters right from the beginning, they needed time to show me who they were.

So, now I’m back at the first draft of another novel, and again I can see the story I want to tell, but I’m having difficulty scaling that warped wall. I’ve made three separate approaches so far, and none of them has quite worked. What usually happens is that the story loses momentum and eventually stalls. And if I’m losing interest in it, there is no way I can convince readers to keep going.

This morning I woke before the alarm and tried looking at the story from a new angle. I’m not quite convinced that this will be the strategy to get me over the wall. What I have to trust, though, is that this is part of my writing process. And the obstacle is going to remain there until I figure out how to scale it.

It’s time to take a step back to the beginning of the slope. My next run at it might be the one I need to get over.

Published on May 17, 2016 08:27

May 13, 2016

Book Review: A List of Things that Didn't Kill Me

When I wasn’t reading it, I was thinking about it.

Jason Schmidt’s memoir, A List of Things that Didn’t Kill Me, covers his childhood up to his first years in college. His upbringing is anything but typical: the son of a drug dealer/addict, Jason lives on the fringes of society. He and his father, Mark, move up and down the west coast, striving for a secure and stable environment, but their lives are a series of upsets as Mark is in and out of jail, in and out of relationships, in and out of jobs.

Jason keeps the perspective focused on his younger self; this is a child without benefit of clear adult guidance trying to make sense of a world that has unspoken rules. There is the hippie and drug culture he lives among, and then there are the “straights” – the people who are “traditional,” law-abiding citizens. Jason has to learn how to straddle these worlds without drawing undue attention on his father’s unconventional lifestyle or risk having the scant foundation he feels pulled out from under him.

Jason keeps the perspective focused on his younger self; this is a child without benefit of clear adult guidance trying to make sense of a world that has unspoken rules. There is the hippie and drug culture he lives among, and then there are the “straights” – the people who are “traditional,” law-abiding citizens. Jason has to learn how to straddle these worlds without drawing undue attention on his father’s unconventional lifestyle or risk having the scant foundation he feels pulled out from under him.

Jason’s father, Mark, is a homosexual having the first taste of freedom from the closet. But this is the 1980s, and AIDS is making its first appearance in the gay community. As Mark struggles to fully inhabit his new sense of identity, Jason simply takes it in stride that his father is dating a man. This isn’t open-mindedness but rather a child’s unquestioning acceptance of what is presented as the norm.

As he enters public school, Jason grows aware that his home life is out of whack. Since he doesn’t seem to fit in with the other kids, he gets into fights, but this lashing out is also a way of trying to gain connection. He pieces together that other people don’t live the way he does, so he becomes increasingly guarded about his home life.

All of Jason’s friendships come across as tenuous, more a matter of circumstance rather than emotional connection. Surprisingly he stays clean: he doesn’t deal drugs, he doesn’t have sex, he doesn’t steal. This isn’t a righteously moralistic stance; he simply recognizes that if he draws attention to himself, it might bring the authorities crashing down on his head. To survive, it is essential to keep a low profile.

All of Jason’s friendships come across as tenuous, more a matter of circumstance rather than emotional connection. Surprisingly he stays clean: he doesn’t deal drugs, he doesn’t have sex, he doesn’t steal. This isn’t a righteously moralistic stance; he simply recognizes that if he draws attention to himself, it might bring the authorities crashing down on his head. To survive, it is essential to keep a low profile.

Schmidt is a good storyteller. He takes seemingly simple episodes, such as a first day at a new school, and effectively describes how it feels to be a perpetual outsider. So much of what is taken for granted among the “straights” is utterly foreign to this young boy, and there is no one to guide him through this curious landscape.

I'm still standingOnce he becomes a teenager, Jason is consciously at odds with his father, who has become increasingly belligerent and physically abusive. Though on a deep level, Jason knows that his father's behavior is wrong, still he feels he must live the life presented to him. He takes comfort knowing that there will come a day when he will be too big to beat, so his father turns to manipulative “gas-lighting” to torture his son.

I'm still standingOnce he becomes a teenager, Jason is consciously at odds with his father, who has become increasingly belligerent and physically abusive. Though on a deep level, Jason knows that his father's behavior is wrong, still he feels he must live the life presented to him. He takes comfort knowing that there will come a day when he will be too big to beat, so his father turns to manipulative “gas-lighting” to torture his son.

For all its grueling nature, Schmidt’s memoir is very readable and sometimes quite funny. He has a wry sense of humor, and he doesn’t descend into maudlin victimization (though it would make perfect sense if he did). He keeps the story present and real, a recognizable world viewed through an outsider’s lens.

After Mark dies, Jason continues in college, all while suffering PTSD. But these episodes are glossed over as the story rushes to the conclusion that he finds a way to survive. I would be curious to read about the next phase in his life as (I’m assuming) he becomes more grounded and finds the support he needs.

I know it’s a cliché, but this story will stay with me. I needed to know how it ended, and I kept thinking about how grateful I am that I did not have to endure what he did. Schmidt has amazing resilience and insight.

For what it’s worth, I wish I had come up with the title. It perfectly captures the tone of the book.

Jason Schmidt’s memoir, A List of Things that Didn’t Kill Me, covers his childhood up to his first years in college. His upbringing is anything but typical: the son of a drug dealer/addict, Jason lives on the fringes of society. He and his father, Mark, move up and down the west coast, striving for a secure and stable environment, but their lives are a series of upsets as Mark is in and out of jail, in and out of relationships, in and out of jobs.

Jason keeps the perspective focused on his younger self; this is a child without benefit of clear adult guidance trying to make sense of a world that has unspoken rules. There is the hippie and drug culture he lives among, and then there are the “straights” – the people who are “traditional,” law-abiding citizens. Jason has to learn how to straddle these worlds without drawing undue attention on his father’s unconventional lifestyle or risk having the scant foundation he feels pulled out from under him.

Jason keeps the perspective focused on his younger self; this is a child without benefit of clear adult guidance trying to make sense of a world that has unspoken rules. There is the hippie and drug culture he lives among, and then there are the “straights” – the people who are “traditional,” law-abiding citizens. Jason has to learn how to straddle these worlds without drawing undue attention on his father’s unconventional lifestyle or risk having the scant foundation he feels pulled out from under him.Jason’s father, Mark, is a homosexual having the first taste of freedom from the closet. But this is the 1980s, and AIDS is making its first appearance in the gay community. As Mark struggles to fully inhabit his new sense of identity, Jason simply takes it in stride that his father is dating a man. This isn’t open-mindedness but rather a child’s unquestioning acceptance of what is presented as the norm.

As he enters public school, Jason grows aware that his home life is out of whack. Since he doesn’t seem to fit in with the other kids, he gets into fights, but this lashing out is also a way of trying to gain connection. He pieces together that other people don’t live the way he does, so he becomes increasingly guarded about his home life.

All of Jason’s friendships come across as tenuous, more a matter of circumstance rather than emotional connection. Surprisingly he stays clean: he doesn’t deal drugs, he doesn’t have sex, he doesn’t steal. This isn’t a righteously moralistic stance; he simply recognizes that if he draws attention to himself, it might bring the authorities crashing down on his head. To survive, it is essential to keep a low profile.

All of Jason’s friendships come across as tenuous, more a matter of circumstance rather than emotional connection. Surprisingly he stays clean: he doesn’t deal drugs, he doesn’t have sex, he doesn’t steal. This isn’t a righteously moralistic stance; he simply recognizes that if he draws attention to himself, it might bring the authorities crashing down on his head. To survive, it is essential to keep a low profile.Schmidt is a good storyteller. He takes seemingly simple episodes, such as a first day at a new school, and effectively describes how it feels to be a perpetual outsider. So much of what is taken for granted among the “straights” is utterly foreign to this young boy, and there is no one to guide him through this curious landscape.

I'm still standingOnce he becomes a teenager, Jason is consciously at odds with his father, who has become increasingly belligerent and physically abusive. Though on a deep level, Jason knows that his father's behavior is wrong, still he feels he must live the life presented to him. He takes comfort knowing that there will come a day when he will be too big to beat, so his father turns to manipulative “gas-lighting” to torture his son.

I'm still standingOnce he becomes a teenager, Jason is consciously at odds with his father, who has become increasingly belligerent and physically abusive. Though on a deep level, Jason knows that his father's behavior is wrong, still he feels he must live the life presented to him. He takes comfort knowing that there will come a day when he will be too big to beat, so his father turns to manipulative “gas-lighting” to torture his son.For all its grueling nature, Schmidt’s memoir is very readable and sometimes quite funny. He has a wry sense of humor, and he doesn’t descend into maudlin victimization (though it would make perfect sense if he did). He keeps the story present and real, a recognizable world viewed through an outsider’s lens.

After Mark dies, Jason continues in college, all while suffering PTSD. But these episodes are glossed over as the story rushes to the conclusion that he finds a way to survive. I would be curious to read about the next phase in his life as (I’m assuming) he becomes more grounded and finds the support he needs.

I know it’s a cliché, but this story will stay with me. I needed to know how it ended, and I kept thinking about how grateful I am that I did not have to endure what he did. Schmidt has amazing resilience and insight.

For what it’s worth, I wish I had come up with the title. It perfectly captures the tone of the book.

Published on May 13, 2016 08:07

April 29, 2016

Book Review: In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex

“Call me Thomas Nickerson.”

It doesn’t have the sane ring as Ishmael. But it is from the true story of the sinking of the Essex that Herman Melville was inspired to write Moby Dick.

In 1820, the whaleship Essex was approaching the Pacific Hunting Grounds when it was attacked by a large sperm whale. The whale repeatedly rammed the ship, crushing the bow. It is conjectured that this was either in defense or retaliation against the whalers. The sailors, forced to leave their sinking vessel, embarked in three whaleboats. For the next 95 days, they sailed more than 2,000 miles before being rescued. One by one, the crew died, and as supplies dwindled, the remaining sailors resorted to cannibalism in order to survive.

In 1820, the whaleship Essex was approaching the Pacific Hunting Grounds when it was attacked by a large sperm whale. The whale repeatedly rammed the ship, crushing the bow. It is conjectured that this was either in defense or retaliation against the whalers. The sailors, forced to leave their sinking vessel, embarked in three whaleboats. For the next 95 days, they sailed more than 2,000 miles before being rescued. One by one, the crew died, and as supplies dwindled, the remaining sailors resorted to cannibalism in order to survive.

I've got a whale of a taleTo reconstruct the history, author Nathaniel Philbrick uses the first mate Owen Chase’s first-person account, first published in 1821. Chase cuts a dashing figure as first mate, the sort of hero a story like this needs. He is decisive whereas Captain George Pollard is somewhat passive. While both Chase’s and Pollard’s individual whaleboats do eventually reach safety, it is Chase who comes across as the more valiant.

I've got a whale of a taleTo reconstruct the history, author Nathaniel Philbrick uses the first mate Owen Chase’s first-person account, first published in 1821. Chase cuts a dashing figure as first mate, the sort of hero a story like this needs. He is decisive whereas Captain George Pollard is somewhat passive. While both Chase’s and Pollard’s individual whaleboats do eventually reach safety, it is Chase who comes across as the more valiant.

But Philbrick does not rely on Chase’s account alone. He also uses secondhand documents from the ship captains who rescued the survivors. Of even more importance, he uses the cabin boy Thomas Nickerson’s account, long thought to be lost. Originally written in the 1876, the document was rediscovered in the 1960s. This narrative offers a slightly different version of the events, in particular the portrayal of Owen Chase. Philbrick nicely contrasts the Nickerson’s version to Chase’s to create a more complex history.

After giving a brief overview of the history of whaling, Philbrick examines Nantucket in particular, especially in terms of how the social network affected the sailors’ personalities. He also describes in detail the process of whale hunting and rendering the carcass. I confess that I had a harder time reading about the rendering than about the cannibalism. Maybe by the time I got to the sections on survival tactics, it made sense that these sailors would do what they needed to in order to survive.

In the Heart of the Sea won the 2000 U.S. National Book Award for Nonfiction.

It doesn’t have the sane ring as Ishmael. But it is from the true story of the sinking of the Essex that Herman Melville was inspired to write Moby Dick.

In 1820, the whaleship Essex was approaching the Pacific Hunting Grounds when it was attacked by a large sperm whale. The whale repeatedly rammed the ship, crushing the bow. It is conjectured that this was either in defense or retaliation against the whalers. The sailors, forced to leave their sinking vessel, embarked in three whaleboats. For the next 95 days, they sailed more than 2,000 miles before being rescued. One by one, the crew died, and as supplies dwindled, the remaining sailors resorted to cannibalism in order to survive.

In 1820, the whaleship Essex was approaching the Pacific Hunting Grounds when it was attacked by a large sperm whale. The whale repeatedly rammed the ship, crushing the bow. It is conjectured that this was either in defense or retaliation against the whalers. The sailors, forced to leave their sinking vessel, embarked in three whaleboats. For the next 95 days, they sailed more than 2,000 miles before being rescued. One by one, the crew died, and as supplies dwindled, the remaining sailors resorted to cannibalism in order to survive. I've got a whale of a taleTo reconstruct the history, author Nathaniel Philbrick uses the first mate Owen Chase’s first-person account, first published in 1821. Chase cuts a dashing figure as first mate, the sort of hero a story like this needs. He is decisive whereas Captain George Pollard is somewhat passive. While both Chase’s and Pollard’s individual whaleboats do eventually reach safety, it is Chase who comes across as the more valiant.

I've got a whale of a taleTo reconstruct the history, author Nathaniel Philbrick uses the first mate Owen Chase’s first-person account, first published in 1821. Chase cuts a dashing figure as first mate, the sort of hero a story like this needs. He is decisive whereas Captain George Pollard is somewhat passive. While both Chase’s and Pollard’s individual whaleboats do eventually reach safety, it is Chase who comes across as the more valiant.But Philbrick does not rely on Chase’s account alone. He also uses secondhand documents from the ship captains who rescued the survivors. Of even more importance, he uses the cabin boy Thomas Nickerson’s account, long thought to be lost. Originally written in the 1876, the document was rediscovered in the 1960s. This narrative offers a slightly different version of the events, in particular the portrayal of Owen Chase. Philbrick nicely contrasts the Nickerson’s version to Chase’s to create a more complex history.

After giving a brief overview of the history of whaling, Philbrick examines Nantucket in particular, especially in terms of how the social network affected the sailors’ personalities. He also describes in detail the process of whale hunting and rendering the carcass. I confess that I had a harder time reading about the rendering than about the cannibalism. Maybe by the time I got to the sections on survival tactics, it made sense that these sailors would do what they needed to in order to survive.

In the Heart of the Sea won the 2000 U.S. National Book Award for Nonfiction.

Published on April 29, 2016 08:22

April 23, 2016

Book Review: Pants on Fire

Clayton Smith is upfront about it: Pants on Fire is a collection of lies. It says so in the subtitle. But what sort of lies? Unbelievable elements that have a ring of truth.

Smith’s tall tales take unlikely premises and carries them through whimsical, comical, and at times creepy twist and turns. But the stories don’t rely solely on their quirkiness; for all their comic qualities, they examine the consequences of the choices we make:

A woman plays a game of verbal chess with the Grim Reaper on the other side of her front door.

A woman plays a game of verbal chess with the Grim Reaper on the other side of her front door.

Unsigned postcards accurately predict a couple’s relationship.

A groom gets cold feet. Literally.

A man waiting for the Rapture gets an unexpected visit from Jesus.

"Maybe the Sandalman Twins

"Maybe the Sandalman Twins

won't find me in here."Smith keeps the language light and conversational, so it’s like listening to a friend who knows how to tell a good story. He has a Pythonesque quality to his humor, especially in “The Castle Dim”, where the knight Bimmiden aspires to be part of Arthur’s Round Table instead of one of the “Knights of the Small Parlor Table in the Anteroom Adjacent to the Room Which Holds the Round Table.”

Some of the stories, particularly the creepier ones, have an O. Henry quality. In “The Amazing Brutillo,” a woman is selected to participate in a magic trick and disappears from the magician’s box, but who knows to where? In “The Sandalman Song” – perfect for telling around a campfire – a young boy discovers the truth of an urban legend. The Sandalman Twins can give Freddy Krueger and Slenderman a run for their money.

Good stuff.

Smith is the author of Apocalypticon and Anomaly Flats.

Smith’s tall tales take unlikely premises and carries them through whimsical, comical, and at times creepy twist and turns. But the stories don’t rely solely on their quirkiness; for all their comic qualities, they examine the consequences of the choices we make:

A woman plays a game of verbal chess with the Grim Reaper on the other side of her front door.

A woman plays a game of verbal chess with the Grim Reaper on the other side of her front door.Unsigned postcards accurately predict a couple’s relationship.

A groom gets cold feet. Literally.

A man waiting for the Rapture gets an unexpected visit from Jesus.

"Maybe the Sandalman Twins

"Maybe the Sandalman Twinswon't find me in here."Smith keeps the language light and conversational, so it’s like listening to a friend who knows how to tell a good story. He has a Pythonesque quality to his humor, especially in “The Castle Dim”, where the knight Bimmiden aspires to be part of Arthur’s Round Table instead of one of the “Knights of the Small Parlor Table in the Anteroom Adjacent to the Room Which Holds the Round Table.”

Some of the stories, particularly the creepier ones, have an O. Henry quality. In “The Amazing Brutillo,” a woman is selected to participate in a magic trick and disappears from the magician’s box, but who knows to where? In “The Sandalman Song” – perfect for telling around a campfire – a young boy discovers the truth of an urban legend. The Sandalman Twins can give Freddy Krueger and Slenderman a run for their money.

Good stuff.

Smith is the author of Apocalypticon and Anomaly Flats.

Published on April 23, 2016 09:44