Louis Arata's Blog, page 12

December 21, 2015

Book Review: A Journey to Matecumbe

When I was twelve, I saw the Disney movie The Treasure of Matecumbe, which starred Robert Foxworthy, Joan Hackett, and Peter Ustinov. I probably liked it at the time, though the only thing I remember is Peter Ustinov being swept off his feet during a hurricane and rolling toward the sea. For Christmas, my mother bought me the book, A Journey to Matecumbe by Robert Lewis Taylor, the basis for the movie.

I never got very far in the book because Davie’s Uncle Jim is a member of the Ku Klux Klan, and I couldn’t reconcile that the hero of the book would be in any way associated with a hate group. I tried a couple times to get through it, but I always got hung up on this enormous detail.

Something recently made me think about the book again, and I dug up a copy from the library to see if I could get through it. And the truth is I really had to force myself through the first part. Even though Uncle Jim recants his membership in the KKK, and he and Davie go on the run, there is something decidedly unpleasant about the storyline.

But that’s the thing about this book: Robert Lewis Taylor is writing a novel about the antebellum South, its racism and its reconstruction. It’s not the shiniest period in U.S. history, and the author doesn’t shy away from the absurd aspects of culture nor its bitter racism. The book is full of questionable characters seen through the eyes of fourteen year old Davie, who is getting his first glimpse at the wider world.

This is a novel.

This is a novel.

This is a movie.The adventures are a mixture of Mark Twain and Dicken’s Martin Chuzzlewit. The characters elbow each other to get the spotlight, basking in their grandiosity. There are Civil War veterans, quack doctors, wily villains, and a fair amount of racist portrayals of Native Americans and Blacks. But is the author representing how society probably was at the time or is he subtle enough to tap into the humanity of the characters, despite the stereotypes? I haven’t decided. My guess is that he is endeavoring to be historically accurate while representing a bit more enlightened view of the world. The novel was written in the 1961 in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement so he was probably sensitive to the complexity of the characters. By 21st Century standards, though, the book feels dated, sociologically speaking. The movie focuses on the adventures to find the treasure, while the novel uses it as the McGuffin. It’s the excuse for the various episodes: Uncle Jim encountering a pal from the Mexican-American War, Davie and Lauriette hooking up with Native Americans to sail through the Florida swamps, Dr Snodgrass shystering small-town yokels. By the time they reach the treasure, its discovery is tossed off in three anticlimactic paragraphs. In other words, the journey is more important than the destination.

This is a movie.The adventures are a mixture of Mark Twain and Dicken’s Martin Chuzzlewit. The characters elbow each other to get the spotlight, basking in their grandiosity. There are Civil War veterans, quack doctors, wily villains, and a fair amount of racist portrayals of Native Americans and Blacks. But is the author representing how society probably was at the time or is he subtle enough to tap into the humanity of the characters, despite the stereotypes? I haven’t decided. My guess is that he is endeavoring to be historically accurate while representing a bit more enlightened view of the world. The novel was written in the 1961 in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement so he was probably sensitive to the complexity of the characters. By 21st Century standards, though, the book feels dated, sociologically speaking. The movie focuses on the adventures to find the treasure, while the novel uses it as the McGuffin. It’s the excuse for the various episodes: Uncle Jim encountering a pal from the Mexican-American War, Davie and Lauriette hooking up with Native Americans to sail through the Florida swamps, Dr Snodgrass shystering small-town yokels. By the time they reach the treasure, its discovery is tossed off in three anticlimactic paragraphs. In other words, the journey is more important than the destination.

A Journey to Matecumbe is long by today’s standards. YA novels tend to roll out over the course of many books, so Robert Lewis Taylor’s novel may seem a bit ponderous, but if you’re in a Twain type of mood, you might enjoy the adventures.

I enjoyed some sections of the novel, and I got bored in others. I guess I will keep trying to figure out if it’s a product of its time or an accurate portrayal of the antebellum world.

I never got very far in the book because Davie’s Uncle Jim is a member of the Ku Klux Klan, and I couldn’t reconcile that the hero of the book would be in any way associated with a hate group. I tried a couple times to get through it, but I always got hung up on this enormous detail.

Something recently made me think about the book again, and I dug up a copy from the library to see if I could get through it. And the truth is I really had to force myself through the first part. Even though Uncle Jim recants his membership in the KKK, and he and Davie go on the run, there is something decidedly unpleasant about the storyline.

But that’s the thing about this book: Robert Lewis Taylor is writing a novel about the antebellum South, its racism and its reconstruction. It’s not the shiniest period in U.S. history, and the author doesn’t shy away from the absurd aspects of culture nor its bitter racism. The book is full of questionable characters seen through the eyes of fourteen year old Davie, who is getting his first glimpse at the wider world.

This is a novel.

This is a novel.

This is a movie.The adventures are a mixture of Mark Twain and Dicken’s Martin Chuzzlewit. The characters elbow each other to get the spotlight, basking in their grandiosity. There are Civil War veterans, quack doctors, wily villains, and a fair amount of racist portrayals of Native Americans and Blacks. But is the author representing how society probably was at the time or is he subtle enough to tap into the humanity of the characters, despite the stereotypes? I haven’t decided. My guess is that he is endeavoring to be historically accurate while representing a bit more enlightened view of the world. The novel was written in the 1961 in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement so he was probably sensitive to the complexity of the characters. By 21st Century standards, though, the book feels dated, sociologically speaking. The movie focuses on the adventures to find the treasure, while the novel uses it as the McGuffin. It’s the excuse for the various episodes: Uncle Jim encountering a pal from the Mexican-American War, Davie and Lauriette hooking up with Native Americans to sail through the Florida swamps, Dr Snodgrass shystering small-town yokels. By the time they reach the treasure, its discovery is tossed off in three anticlimactic paragraphs. In other words, the journey is more important than the destination.

This is a movie.The adventures are a mixture of Mark Twain and Dicken’s Martin Chuzzlewit. The characters elbow each other to get the spotlight, basking in their grandiosity. There are Civil War veterans, quack doctors, wily villains, and a fair amount of racist portrayals of Native Americans and Blacks. But is the author representing how society probably was at the time or is he subtle enough to tap into the humanity of the characters, despite the stereotypes? I haven’t decided. My guess is that he is endeavoring to be historically accurate while representing a bit more enlightened view of the world. The novel was written in the 1961 in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement so he was probably sensitive to the complexity of the characters. By 21st Century standards, though, the book feels dated, sociologically speaking. The movie focuses on the adventures to find the treasure, while the novel uses it as the McGuffin. It’s the excuse for the various episodes: Uncle Jim encountering a pal from the Mexican-American War, Davie and Lauriette hooking up with Native Americans to sail through the Florida swamps, Dr Snodgrass shystering small-town yokels. By the time they reach the treasure, its discovery is tossed off in three anticlimactic paragraphs. In other words, the journey is more important than the destination.A Journey to Matecumbe is long by today’s standards. YA novels tend to roll out over the course of many books, so Robert Lewis Taylor’s novel may seem a bit ponderous, but if you’re in a Twain type of mood, you might enjoy the adventures.

I enjoyed some sections of the novel, and I got bored in others. I guess I will keep trying to figure out if it’s a product of its time or an accurate portrayal of the antebellum world.

Published on December 21, 2015 06:56

December 18, 2015

Book Review: Night

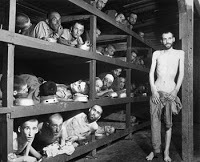

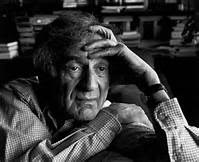

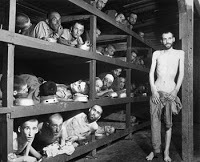

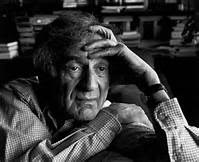

How do you review a book like Elie Wiesel’s Night? It’s a horrifying depiction of his experiences in Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

At fifteen, Wiesel and his family were living in Sighet, Transylvania (Romania). While there was plenty of evidence of Hitler’s hatred of the Jews, no one wanted to believe the rumors about the camps. In 1944, the Nazis arrive in town and blockade whole neighborhoods, forming ghettos for the Jews. Soon after, the Jews are herded out of town, onto trains, and sent to concentration camps. Elie and his father are separated from his mother and sisters, who do not survive. For the next twelve months, Elie and his father struggle to survive hard labor, starvation, beatings, and the ever-present threat of the furnaces. In April 1945, Buchenwald camp is liberated by Americans. Elie survives but his father does not.

At fifteen, Wiesel and his family were living in Sighet, Transylvania (Romania). While there was plenty of evidence of Hitler’s hatred of the Jews, no one wanted to believe the rumors about the camps. In 1944, the Nazis arrive in town and blockade whole neighborhoods, forming ghettos for the Jews. Soon after, the Jews are herded out of town, onto trains, and sent to concentration camps. Elie and his father are separated from his mother and sisters, who do not survive. For the next twelve months, Elie and his father struggle to survive hard labor, starvation, beatings, and the ever-present threat of the furnaces. In April 1945, Buchenwald camp is liberated by Americans. Elie survives but his father does not.

Nightis the first in a trilogy that also includes Dawn and Day. Wiesel said, “In Night, I wanted to show the end, the finality of the event. Everything came to an end – man, history, literature, religion, God. There was nothing left. And yet we begin again with night.”

Evidently part of the struggle is how to treat the book – as a memoir, an autobiography, a novel? Wiesel called it his deposition.

It’s easy to get tangled up in whether the work is historically accurate but that can end up distracting you from the power of the work. As much as I have read and learned about WWII, I still struggle to comprehend the enormity of the Nazis crimes. They are so overwhelming that the brain freezes up and can’t compute the appalling number of dead, the cruelty of the camps, the amorality of the Nazis.

It’s easy to get tangled up in whether the work is historically accurate but that can end up distracting you from the power of the work. As much as I have read and learned about WWII, I still struggle to comprehend the enormity of the Nazis crimes. They are so overwhelming that the brain freezes up and can’t compute the appalling number of dead, the cruelty of the camps, the amorality of the Nazis.

Wiesel’s original draft was 862 pages, a fierce indictment of the Nazis crimes, but he ended up paring it down to a sparse 200-page manuscript that relies more on his internal experience rather than the literal interpretation of events. He uses Spartan language to emphasize the absolute inhumanity that was perpetrated. In describing the death march to Buchwenwald:

Wiesel’s original draft was 862 pages, a fierce indictment of the Nazis crimes, but he ended up paring it down to a sparse 200-page manuscript that relies more on his internal experience rather than the literal interpretation of events. He uses Spartan language to emphasize the absolute inhumanity that was perpetrated. In describing the death march to Buchwenwald:

“An icy wind blew in violent gusts. But we marched without faltering. The SS made us increase our pace. ‘Faster, you swine, you filthy sons of bitches!’ … I was putting one foot in front of the other mechanically. I was dragging with me this skeletal body which weighed so much. If only I could have got rid of it!”

Nightis an essential read. It is difficult, disturbing, horrifying but absolutely necessary. Given the current state of our world and how leaders are driving us deeper into wars and acts of terrorism, we need to be reminded again and again what the true cost is: our brothers and sisters die because of political decisions, and no rationale can justify it.

At fifteen, Wiesel and his family were living in Sighet, Transylvania (Romania). While there was plenty of evidence of Hitler’s hatred of the Jews, no one wanted to believe the rumors about the camps. In 1944, the Nazis arrive in town and blockade whole neighborhoods, forming ghettos for the Jews. Soon after, the Jews are herded out of town, onto trains, and sent to concentration camps. Elie and his father are separated from his mother and sisters, who do not survive. For the next twelve months, Elie and his father struggle to survive hard labor, starvation, beatings, and the ever-present threat of the furnaces. In April 1945, Buchenwald camp is liberated by Americans. Elie survives but his father does not.

At fifteen, Wiesel and his family were living in Sighet, Transylvania (Romania). While there was plenty of evidence of Hitler’s hatred of the Jews, no one wanted to believe the rumors about the camps. In 1944, the Nazis arrive in town and blockade whole neighborhoods, forming ghettos for the Jews. Soon after, the Jews are herded out of town, onto trains, and sent to concentration camps. Elie and his father are separated from his mother and sisters, who do not survive. For the next twelve months, Elie and his father struggle to survive hard labor, starvation, beatings, and the ever-present threat of the furnaces. In April 1945, Buchenwald camp is liberated by Americans. Elie survives but his father does not. Nightis the first in a trilogy that also includes Dawn and Day. Wiesel said, “In Night, I wanted to show the end, the finality of the event. Everything came to an end – man, history, literature, religion, God. There was nothing left. And yet we begin again with night.”

Evidently part of the struggle is how to treat the book – as a memoir, an autobiography, a novel? Wiesel called it his deposition.

It’s easy to get tangled up in whether the work is historically accurate but that can end up distracting you from the power of the work. As much as I have read and learned about WWII, I still struggle to comprehend the enormity of the Nazis crimes. They are so overwhelming that the brain freezes up and can’t compute the appalling number of dead, the cruelty of the camps, the amorality of the Nazis.

It’s easy to get tangled up in whether the work is historically accurate but that can end up distracting you from the power of the work. As much as I have read and learned about WWII, I still struggle to comprehend the enormity of the Nazis crimes. They are so overwhelming that the brain freezes up and can’t compute the appalling number of dead, the cruelty of the camps, the amorality of the Nazis. Wiesel’s original draft was 862 pages, a fierce indictment of the Nazis crimes, but he ended up paring it down to a sparse 200-page manuscript that relies more on his internal experience rather than the literal interpretation of events. He uses Spartan language to emphasize the absolute inhumanity that was perpetrated. In describing the death march to Buchwenwald:

Wiesel’s original draft was 862 pages, a fierce indictment of the Nazis crimes, but he ended up paring it down to a sparse 200-page manuscript that relies more on his internal experience rather than the literal interpretation of events. He uses Spartan language to emphasize the absolute inhumanity that was perpetrated. In describing the death march to Buchwenwald:“An icy wind blew in violent gusts. But we marched without faltering. The SS made us increase our pace. ‘Faster, you swine, you filthy sons of bitches!’ … I was putting one foot in front of the other mechanically. I was dragging with me this skeletal body which weighed so much. If only I could have got rid of it!”

Nightis an essential read. It is difficult, disturbing, horrifying but absolutely necessary. Given the current state of our world and how leaders are driving us deeper into wars and acts of terrorism, we need to be reminded again and again what the true cost is: our brothers and sisters die because of political decisions, and no rationale can justify it.

Published on December 18, 2015 08:00

December 9, 2015

Book Review: An End to the Thrill

Time-travel. Computer viruses. Raindrops. Varun Kumar has a quirky take on storytelling. In his short story collection An End to the Thrill, he composes concise, philosophical tales with unusual twists. Nothing is quite what it appears to be.

The trick in reviewing the stories is to not give away the endings. Once you catch on that the stories contain the unexpected, part of the fun is to see if you can figure out how they will turn out. The trouble with this approach, however, is that the stories might come across as novelties rather than as thoughtful meditations on the human experience in the midst of an uncertain world.

Take the story “If Time Could Tell,” which deals with how time travel affects a husband and wife. Time travel is an intriguing concept, with lots of changing variables as the present readjusts to the past and future. Life flows in ripples as each event unfolds. But what Kumar does is tap into the inherent tensions of the couple's relationship. There is as much focus on the failure of communication between them as there is on the unexpected fate.

Take the story “If Time Could Tell,” which deals with how time travel affects a husband and wife. Time travel is an intriguing concept, with lots of changing variables as the present readjusts to the past and future. Life flows in ripples as each event unfolds. But what Kumar does is tap into the inherent tensions of the couple's relationship. There is as much focus on the failure of communication between them as there is on the unexpected fate.

Kumar also uses anthropomorphism and personification to touch on themes of betrayal and healing. He uses the human point of view in microcosmic arenas where the narrator has a very limited perspective on how the world works. We think we know what is going on, but sometimes we are blindsided by a force of nature or the rules of physics. Life’s unexpected challenges.

Kumar’s language is direct and unadorned; he does not waste time on superfluous descriptions or unnecessary character analysis. In “Severence or Adherence,” he gets right down to business with the theme of choices, as well as insight into the narrator Mr. Denfi’s personality:

“I was standing at a place with two paths in front of me and I had to make a choice. I was always bad at making choices.”

An End to the Thrill is a quick, satisfying read and shows the talent of a good storyteller.

The trick in reviewing the stories is to not give away the endings. Once you catch on that the stories contain the unexpected, part of the fun is to see if you can figure out how they will turn out. The trouble with this approach, however, is that the stories might come across as novelties rather than as thoughtful meditations on the human experience in the midst of an uncertain world.

Take the story “If Time Could Tell,” which deals with how time travel affects a husband and wife. Time travel is an intriguing concept, with lots of changing variables as the present readjusts to the past and future. Life flows in ripples as each event unfolds. But what Kumar does is tap into the inherent tensions of the couple's relationship. There is as much focus on the failure of communication between them as there is on the unexpected fate.

Take the story “If Time Could Tell,” which deals with how time travel affects a husband and wife. Time travel is an intriguing concept, with lots of changing variables as the present readjusts to the past and future. Life flows in ripples as each event unfolds. But what Kumar does is tap into the inherent tensions of the couple's relationship. There is as much focus on the failure of communication between them as there is on the unexpected fate.Kumar also uses anthropomorphism and personification to touch on themes of betrayal and healing. He uses the human point of view in microcosmic arenas where the narrator has a very limited perspective on how the world works. We think we know what is going on, but sometimes we are blindsided by a force of nature or the rules of physics. Life’s unexpected challenges.

Kumar’s language is direct and unadorned; he does not waste time on superfluous descriptions or unnecessary character analysis. In “Severence or Adherence,” he gets right down to business with the theme of choices, as well as insight into the narrator Mr. Denfi’s personality:

“I was standing at a place with two paths in front of me and I had to make a choice. I was always bad at making choices.”

An End to the Thrill is a quick, satisfying read and shows the talent of a good storyteller.

Published on December 09, 2015 06:40

December 1, 2015

Book Review: Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex

She doesn’t know it, but I named one of my characters after Mary Roach. I was reading her book Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers while I was writing the first draft of Dead Hungry. Reading about all the ways corpses can be used in medical and forensic work (not to mention airline safety and plastic surgery) seemed a fitting topic when I was writing about cannibalism (I still get creeped out by macerating a body with honey). Using her name is in no way meant to be disrespectful; I’m a huge fan of her work. It’s just that the name Roach was a perfect fit for one of the more Ghoulish characters in the book.

Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex is her 2008 work on, well, just that: the study of sexual physiology. She reviews some of the earliest research by Kinsey, Masters and Johnson, and Robert Latou Dickenson. But their work is just the tip of the iceberg. Researchers have been trying to figure out the nature of orgasm, the medical cures for erectile dysfunction, and the somewhat mystical workings of the vagina (I was surprised at the amount of theorizing still going on about women’s reproductive systems; I assumed things had been figured out a long time ago).

Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex is her 2008 work on, well, just that: the study of sexual physiology. She reviews some of the earliest research by Kinsey, Masters and Johnson, and Robert Latou Dickenson. But their work is just the tip of the iceberg. Researchers have been trying to figure out the nature of orgasm, the medical cures for erectile dysfunction, and the somewhat mystical workings of the vagina (I was surprised at the amount of theorizing still going on about women’s reproductive systems; I assumed things had been figured out a long time ago).The thing about Roach’s reporting is that she can take a potentially disagreeable and/or unsettling topic and make it fascinating. She knows where to find the most unexpected research (coital imaging, the penis-camera, pig fertilization techniques) and describe it in accessible and at times irreverent terms. Many times the particulars of the research can get me squirming, until she throws in a tongue-in-cheek analogy that makes it more palatable.

Author and Test SubjectNot surprising, I had difficulty getting through the section on Dr. Geng-Long Hsu’s work. He is developing a surgical solution to erectile dysfunction which involves suturing off particular veins in the penis to redirect blood flow. Doesn’t sound too bad, except Roach describes in detail what the operation looks like:

Author and Test SubjectNot surprising, I had difficulty getting through the section on Dr. Geng-Long Hsu’s work. He is developing a surgical solution to erectile dysfunction which involves suturing off particular veins in the penis to redirect blood flow. Doesn’t sound too bad, except Roach describes in detail what the operation looks like:“Once the anesthesia takes effect, Dr. Hsu will begin ‘degloving’ the organ. The verb ‘skinning’ would get the idea across more efficiently, but it is more pleasant, I suppose, to picture an aristocrat gently loosening the fingers of his opera gloves.”

Okay, I’m still squirming.

There could be something very prurient about sexual research, except there isn’t. The researchers and their subjects approach their tasks with high degrees of professionalism, even when performing somewhat unorthodox experiments. Roach excels at focusing on the importance of the work, even if on the surface it might look like quackery. The scientists clearly are driven to understand why the body works the way it does. And there is definitely still a lot to learn.

Still, it’s Roach’s dry humor that carries the reader through:

On Kegeling: "Kegeling has since been taken a step further, in the form of vaginal weightlifting. The idea being: You don’t just flex your muscles if you want to build them up; you train with weights. I once tried the Feminine Personal Trainer for a story. It came with a slip of paper telling me not to be overwhelmed by its weight. I wasn’t. I was overwhelmed by its size. Suffice to say, this is the only workout on Earth that calls for vaginal lubricant. The directions tell you to insert and contract, causing the FPT to rise up inside you until all that can be seen protruding is a doorknob-shaped piece of steel, as though you are giving birth to a hardware store. I use mine as a paperweight.”

On vaginal lubrication: "Dickinson's descriptions of the female secretions read, in places, like a WD-40 advert: 'It is clear as glass, tenacious and persistent, without being sticky. No other lubricant can compare with it in efficiency for a certain smooth and slippery quality ... '"

She certainly knows how to cut through the jargon.

Published on December 01, 2015 07:16

November 24, 2015

Reblog: Stanford Author Explores The Idiosyncratic Process of Writing

This is a great little article about Stanford Lecturer Hilton Obenzinger's "How I Write" project. He interviews writers on their process and soon discovers that they have quirky ways of approaching each project.

Hilton Obenzinger: How I Write

I, myself, tend to use the blunderbuss approach to a first draft: I fire everything I can at the target then see what is closest to the bull's eye.

What are the tools, habits and tricks writers use to get their job done?

What are the tools, habits and tricks writers use to get their job done?

Stanford scholar Hilton Obenzinger shares information he's gathered

since 2002 in a new book, How We Write

I just signed up for Obenzinger's podcast so I have some fun learning to do on my drive to friends for Thanksgiving.

Hilton Obenzinger: How I Write

I, myself, tend to use the blunderbuss approach to a first draft: I fire everything I can at the target then see what is closest to the bull's eye.

What are the tools, habits and tricks writers use to get their job done?

What are the tools, habits and tricks writers use to get their job done?Stanford scholar Hilton Obenzinger shares information he's gathered

since 2002 in a new book, How We Write

I just signed up for Obenzinger's podcast so I have some fun learning to do on my drive to friends for Thanksgiving.

Published on November 24, 2015 05:17

November 20, 2015

Storytelling: Books vs Movie Adaptations

The first time I usually hear about trendy books is when they’re being made into movies. Then, in preparation, I read the book, all excited to see how the director is going to translate it into film. But more times than not, I wind up losing any interest in it.

Why? Not because movie adaptations are notoriously bad. I think in recent years directors and producers have worked very hard to make movies with excellent production design, charismatic casts, and a script that respects the original work.

But more times than not, the movies are merely serviceable. They cling to the notion that being faithful to the novel is the best approach, which gives the director little leeway to visually interpret the work.

For example, John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars has an emotional resonance which comes through Hazel’s first-person narration. The movie opts for the same technique, but by having the voice-over tell us what Hazel is thinking, it ends up spoon-feeding the audience. It’s not that voice-over is always a bad choice, but I can’t help but wonder what else the director might have done if he hadn’t been saddled with sticking so closely to the book.

In contrast, look at Fight Club. Edward Norton’s narration overlays visually interesting scenes. One of my favorite moments is his sweeping gaze of his Ikea-ridden apartment, with the superimposed price tags on every item of furniture. In Palahniuk’s novel, that sort of covetousness is handled in the storytelling, while in the movie, the director David Fincher uses a visual shorthand instead. It’s not that one technique is better than the other; it’s that a novel has one way of telling a story and a movie has another.

Probably my all-time favorite book-to-movie adaptation is The Lord of the Rings. While I have no doubt that Tolkien would not have thought much of Peter Jackson’s films, they must tap into something Middle-Earthian for fans to be so enthralled.

In the second chapter of The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf provides a lengthy exposition on the One Ring. Just as Frodo is being taught the complicated history, so too is the reader. By frontloading the backstory, Tolkien is setting the stage. Then Gandalf introduces how Gollum came upon the ring and the devastating effects it has on him. Having already appeared in The Hobbit, Gollum is a familiar character to the reader and serves as a narrative bridge between the two works.

But Peter Jackson doesn’t do this in his films. Instead, he intimates pieces of Gollum’s story but waits to actually show it. As the films progress, they become visually darker – vibrant colors are replaced by pervasive grays. Frodo and Sam start off in the pastoral beauty of the Shire before trudging through the unsettling bleakness of Mordor. Everything looks grim.

It's a wonderful adaptation!In the prologue to The Return of the King, suddenly we’re back in a beautiful green meadow, with two Hobbit-like individuals – Smeagol and Deagol – fishing from a rowboat. Deagol falls into the river and discovers in the mud the One Ring. Now we witness Smeagol’s downfall: he murders Deagol for the ring, goes mad, hides himself beneath the Misty Mountains. He becomes Gollum. In the space of those few minutes, the color washes from luscious green to despairing gray. In other words, the prologue is a visual template for Frodo’s own trajectory, should he fail to destroy the ring.

It's a wonderful adaptation!In the prologue to The Return of the King, suddenly we’re back in a beautiful green meadow, with two Hobbit-like individuals – Smeagol and Deagol – fishing from a rowboat. Deagol falls into the river and discovers in the mud the One Ring. Now we witness Smeagol’s downfall: he murders Deagol for the ring, goes mad, hides himself beneath the Misty Mountains. He becomes Gollum. In the space of those few minutes, the color washes from luscious green to despairing gray. In other words, the prologue is a visual template for Frodo’s own trajectory, should he fail to destroy the ring.

They changed things!

They changed things!

It's not exactly like the book!So, why does Jackson move the story around? If he had stayed true to Tolkien’s story structure – if he had told Gollum’s tale at the beginning of the first movie – there would have been too long a gap before the viewer sees Frodo in the same type of danger. By the beginning of The Return of the King, the viewer needs that template to know exactly how far Frodo has fallen.

Again, one type of storytelling isn’t better than the other. Tolkien’s choices work in the context of the book. But movies tell stories in different ways, and it’s when a director has the freedom to expand the book beyond the constrictions of a literal adaptation that the movie becomes art in its own right.

Being different animals, books and movies do much better when they complement each other.

Why? Not because movie adaptations are notoriously bad. I think in recent years directors and producers have worked very hard to make movies with excellent production design, charismatic casts, and a script that respects the original work.

But more times than not, the movies are merely serviceable. They cling to the notion that being faithful to the novel is the best approach, which gives the director little leeway to visually interpret the work.

For example, John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars has an emotional resonance which comes through Hazel’s first-person narration. The movie opts for the same technique, but by having the voice-over tell us what Hazel is thinking, it ends up spoon-feeding the audience. It’s not that voice-over is always a bad choice, but I can’t help but wonder what else the director might have done if he hadn’t been saddled with sticking so closely to the book.

In contrast, look at Fight Club. Edward Norton’s narration overlays visually interesting scenes. One of my favorite moments is his sweeping gaze of his Ikea-ridden apartment, with the superimposed price tags on every item of furniture. In Palahniuk’s novel, that sort of covetousness is handled in the storytelling, while in the movie, the director David Fincher uses a visual shorthand instead. It’s not that one technique is better than the other; it’s that a novel has one way of telling a story and a movie has another.

Probably my all-time favorite book-to-movie adaptation is The Lord of the Rings. While I have no doubt that Tolkien would not have thought much of Peter Jackson’s films, they must tap into something Middle-Earthian for fans to be so enthralled.

In the second chapter of The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf provides a lengthy exposition on the One Ring. Just as Frodo is being taught the complicated history, so too is the reader. By frontloading the backstory, Tolkien is setting the stage. Then Gandalf introduces how Gollum came upon the ring and the devastating effects it has on him. Having already appeared in The Hobbit, Gollum is a familiar character to the reader and serves as a narrative bridge between the two works.

But Peter Jackson doesn’t do this in his films. Instead, he intimates pieces of Gollum’s story but waits to actually show it. As the films progress, they become visually darker – vibrant colors are replaced by pervasive grays. Frodo and Sam start off in the pastoral beauty of the Shire before trudging through the unsettling bleakness of Mordor. Everything looks grim.

It's a wonderful adaptation!In the prologue to The Return of the King, suddenly we’re back in a beautiful green meadow, with two Hobbit-like individuals – Smeagol and Deagol – fishing from a rowboat. Deagol falls into the river and discovers in the mud the One Ring. Now we witness Smeagol’s downfall: he murders Deagol for the ring, goes mad, hides himself beneath the Misty Mountains. He becomes Gollum. In the space of those few minutes, the color washes from luscious green to despairing gray. In other words, the prologue is a visual template for Frodo’s own trajectory, should he fail to destroy the ring.

It's a wonderful adaptation!In the prologue to The Return of the King, suddenly we’re back in a beautiful green meadow, with two Hobbit-like individuals – Smeagol and Deagol – fishing from a rowboat. Deagol falls into the river and discovers in the mud the One Ring. Now we witness Smeagol’s downfall: he murders Deagol for the ring, goes mad, hides himself beneath the Misty Mountains. He becomes Gollum. In the space of those few minutes, the color washes from luscious green to despairing gray. In other words, the prologue is a visual template for Frodo’s own trajectory, should he fail to destroy the ring. They changed things!

They changed things!It's not exactly like the book!So, why does Jackson move the story around? If he had stayed true to Tolkien’s story structure – if he had told Gollum’s tale at the beginning of the first movie – there would have been too long a gap before the viewer sees Frodo in the same type of danger. By the beginning of The Return of the King, the viewer needs that template to know exactly how far Frodo has fallen.

Again, one type of storytelling isn’t better than the other. Tolkien’s choices work in the context of the book. But movies tell stories in different ways, and it’s when a director has the freedom to expand the book beyond the constrictions of a literal adaptation that the movie becomes art in its own right.

Being different animals, books and movies do much better when they complement each other.

Published on November 20, 2015 07:39

November 13, 2015

Book Review: Divergent

Divergentwas recommended to me by an effusive barista. We got talking about urban fantasies, and she couldn’t say enough great things about Veronica Roth’s series. It takes place in Chicago sometime in the future, after some cataclysmic event has driven people to wall themselves up in the city and to divide up into factions to survive. The barista encouraged me whole-heartedly: “You’ve got to read it!”

And so I did.

And so I did.

Maybe I’ve read too many dystopian novels, because they’re starting to run together. Each has an intriguing premise, tough characters, gritty action, and the promise of future adventures in the sequels.

Roth’s strongest point is the factions, which fall along lines of personality traits: Abnegation (selflessness), Dauntless (bravery), Erudite (intellect), Candor (unwavering honesty), and Amity (sociability). The characters are born into factions, but at the age of sixteen they participate in a choosing ceremony in which they can either elect to stay or to move to another one, and thereafter undergo a training program to become loyal members of their team.

And then there are the Divergent: those who are mentally nimble enough to recognize that the world does not fall into black-and-white behaviors, but rather each of us carries traits of each of the different factions.

To be part of my team,

To be part of my team,

you have to jump off

the roofRoth’s societal groups reminds me of a team-building workshop I attended. My co-workers and I first took a quiz that separated us into groups based on our work style. There were the leaders, the social, the data, and the tech groups, each with distinctive characteristics. I was with the data group; we tended to like working on solitary projects with a definite goal. The leaders, of course, were all wrestling over who should hold the pen to write down the group’s traits. The social group was loud and boisterous; lots of laughing going on at that table. And the tech group sat silently at its table but kept an eye on everyone else, perpetually on the ready to go dash in and offer help to resolve any problems.

So, Roth’s societal landscape makes sense. We do have loyalties to certain behaviors. And though this is a dystopian novel, there is evidence that the social groupings work … until one faction becomes power-hungry.

Roth does a great job with a large cast of characters. She keeps them intermingling and interacting, because that is where the drama takes place. She also carries Beatrice/Tris, the Divergent narrator, along a believable arc – moving from selfless Abnegation to courageous Dauntless. Tris, of course, is tougher than she expects herself to be, but eventually learns that she has skills that the others do not. By the end, she is bad-ass enough to take on the enemy.

But Roth’s story, intriguing as it is, lacks true individuality. There are dabs of other stories that rise to the surface: the Matrix (Tris’ ability to manipulate the virtual reality), the Hunger Games (every person for themselves), Harry Potter (immersion into an entirely foreign world and the expectation that you will learn to fit in or you will be booted out). These tropes have become so commonplace; you sort of expect to taste the all the familiar flavors. In other words, parts of the story feel marketed to be like the other stories so you don’t have to try too hard to follow along.

And then there’s the brutality. Granted, Roth is not depicting an ideal world, but the casual acceptance of sadism as part of the pecking order is actually pretty disturbing. What does it say about our society that three of them most successful series in young adult books (Harry Potter, the Hunger Games, and Divergent) all feature grueling training exercises and a kill-or-be-killed manifesto? Has the world become so terrible that we instinctively teach our kids that they’d better toughen up or they will be eaten alive? Given what is occurring in the U.S. right now with school shootings, police violence, racial assaults … well, then, yes, I suppose it has.

There are two more books in Roth’s series: Insurgent and Allegiant.

And so I did.

And so I did. Maybe I’ve read too many dystopian novels, because they’re starting to run together. Each has an intriguing premise, tough characters, gritty action, and the promise of future adventures in the sequels.

Roth’s strongest point is the factions, which fall along lines of personality traits: Abnegation (selflessness), Dauntless (bravery), Erudite (intellect), Candor (unwavering honesty), and Amity (sociability). The characters are born into factions, but at the age of sixteen they participate in a choosing ceremony in which they can either elect to stay or to move to another one, and thereafter undergo a training program to become loyal members of their team.

And then there are the Divergent: those who are mentally nimble enough to recognize that the world does not fall into black-and-white behaviors, but rather each of us carries traits of each of the different factions.

To be part of my team,

To be part of my team,you have to jump off

the roofRoth’s societal groups reminds me of a team-building workshop I attended. My co-workers and I first took a quiz that separated us into groups based on our work style. There were the leaders, the social, the data, and the tech groups, each with distinctive characteristics. I was with the data group; we tended to like working on solitary projects with a definite goal. The leaders, of course, were all wrestling over who should hold the pen to write down the group’s traits. The social group was loud and boisterous; lots of laughing going on at that table. And the tech group sat silently at its table but kept an eye on everyone else, perpetually on the ready to go dash in and offer help to resolve any problems.

So, Roth’s societal landscape makes sense. We do have loyalties to certain behaviors. And though this is a dystopian novel, there is evidence that the social groupings work … until one faction becomes power-hungry.

Roth does a great job with a large cast of characters. She keeps them intermingling and interacting, because that is where the drama takes place. She also carries Beatrice/Tris, the Divergent narrator, along a believable arc – moving from selfless Abnegation to courageous Dauntless. Tris, of course, is tougher than she expects herself to be, but eventually learns that she has skills that the others do not. By the end, she is bad-ass enough to take on the enemy.

But Roth’s story, intriguing as it is, lacks true individuality. There are dabs of other stories that rise to the surface: the Matrix (Tris’ ability to manipulate the virtual reality), the Hunger Games (every person for themselves), Harry Potter (immersion into an entirely foreign world and the expectation that you will learn to fit in or you will be booted out). These tropes have become so commonplace; you sort of expect to taste the all the familiar flavors. In other words, parts of the story feel marketed to be like the other stories so you don’t have to try too hard to follow along.

And then there’s the brutality. Granted, Roth is not depicting an ideal world, but the casual acceptance of sadism as part of the pecking order is actually pretty disturbing. What does it say about our society that three of them most successful series in young adult books (Harry Potter, the Hunger Games, and Divergent) all feature grueling training exercises and a kill-or-be-killed manifesto? Has the world become so terrible that we instinctively teach our kids that they’d better toughen up or they will be eaten alive? Given what is occurring in the U.S. right now with school shootings, police violence, racial assaults … well, then, yes, I suppose it has.

There are two more books in Roth’s series: Insurgent and Allegiant.

Published on November 13, 2015 07:49

October 30, 2015

Book Review: Siddhartha

In my freshman high school English class, we read a ton of classics: A Tale of Two Cities, Les Miserables (abridged), Hedda Gabler, and selections from The Odyssey. This was heavy-duty Literature (with a capital L), and you were supposed to comprehend the gravitas inherent in each.

But the three books I enjoyed the most were ones I’d never heard of before: Nectar in a Sieve (Kamala Markandaya), Growth of the Soil (Knut Hamsen), and Siddhartha. Both Nectarand Growth are stories of family struggles against the elements and society. Siddhartha is about a spiritual journey.

I’ve read Siddhartha four times now. It’s my go-to book when I need to cleanse my palate. Plus, it’s short. After reading lengthy tomes (such as The Brothers Karamazov and A Game of Thrones), I need the freshness of brevity.

I’ve read Siddhartha four times now. It’s my go-to book when I need to cleanse my palate. Plus, it’s short. After reading lengthy tomes (such as The Brothers Karamazov and A Game of Thrones), I need the freshness of brevity.

The fact that I keep coming back to it, though, is not solely that it is a quick read. There is something decidedly peaceful about Siddhartha’s journey. A Brahmin’s son, he dispenses with the traditional education and elects to live an ascetic life. He encounters Gotama, the Buddha, and though he recognizes the teacher’s wisdom, Siddhartha is committed to following his own path. In other words, in order to learn, he must live.

Hesse’s novel follows Siddhartha through asceticism, capitalism, romance, and fatherhood. Each time he reaches the end of a path, he comprehends what he has learned. No lesson is pointless, and he is not ashamed of his time engaged with each occupation, but as he cycles through the phases of life, he reaches a point in which he craves something more.

“He felt he had thoroughly tasted and ejected a portion of sorrow, a portion of misery during those past times, that he had consumed them up to a point of despair and death. But all was well. He could have remained much longer with Kamaswami, made and squandered money, fed his body and neglected his soul; he could have dwelt for a long time yet in that soft, well-upholstered hell, if this had not happened, this moment of complete hopelessness and despair and the tense moment when he had bent over the flowing water, ready to commit suicide. This despair, this extreme nausea which he had experienced had not overpowered him. The bird, the clear spring and voice within him was still alive – that was why he rejoiced, that was why he laughed, that was why his face was radiant under his grey hair.” Who's my cutesy, little Nirvana?

Who's my cutesy, little Nirvana?

It’s deceptively simple language, rich with poetry and depth. The book reads almost as a parable, but Hesse never resorts to didactic purpose. Siddhartha’s journey may encounter recognizable milestones – love, career, family – but what pervades them all is the spiritual. Siddhartha remains focused on discovering the unity of life. Nirvana is not so much a goal but rather an awareness that it encompasses the whole of life: sin, desire, joy, laughter, love, despair.

About ten years ago I cleared off my over-stacked bookshelves and kept only those book that mean the most to me. The ones I will come back to again and again. Siddhartha is one of them.

But the three books I enjoyed the most were ones I’d never heard of before: Nectar in a Sieve (Kamala Markandaya), Growth of the Soil (Knut Hamsen), and Siddhartha. Both Nectarand Growth are stories of family struggles against the elements and society. Siddhartha is about a spiritual journey.

I’ve read Siddhartha four times now. It’s my go-to book when I need to cleanse my palate. Plus, it’s short. After reading lengthy tomes (such as The Brothers Karamazov and A Game of Thrones), I need the freshness of brevity.

I’ve read Siddhartha four times now. It’s my go-to book when I need to cleanse my palate. Plus, it’s short. After reading lengthy tomes (such as The Brothers Karamazov and A Game of Thrones), I need the freshness of brevity.The fact that I keep coming back to it, though, is not solely that it is a quick read. There is something decidedly peaceful about Siddhartha’s journey. A Brahmin’s son, he dispenses with the traditional education and elects to live an ascetic life. He encounters Gotama, the Buddha, and though he recognizes the teacher’s wisdom, Siddhartha is committed to following his own path. In other words, in order to learn, he must live.

Hesse’s novel follows Siddhartha through asceticism, capitalism, romance, and fatherhood. Each time he reaches the end of a path, he comprehends what he has learned. No lesson is pointless, and he is not ashamed of his time engaged with each occupation, but as he cycles through the phases of life, he reaches a point in which he craves something more.

“He felt he had thoroughly tasted and ejected a portion of sorrow, a portion of misery during those past times, that he had consumed them up to a point of despair and death. But all was well. He could have remained much longer with Kamaswami, made and squandered money, fed his body and neglected his soul; he could have dwelt for a long time yet in that soft, well-upholstered hell, if this had not happened, this moment of complete hopelessness and despair and the tense moment when he had bent over the flowing water, ready to commit suicide. This despair, this extreme nausea which he had experienced had not overpowered him. The bird, the clear spring and voice within him was still alive – that was why he rejoiced, that was why he laughed, that was why his face was radiant under his grey hair.”

Who's my cutesy, little Nirvana?

Who's my cutesy, little Nirvana?It’s deceptively simple language, rich with poetry and depth. The book reads almost as a parable, but Hesse never resorts to didactic purpose. Siddhartha’s journey may encounter recognizable milestones – love, career, family – but what pervades them all is the spiritual. Siddhartha remains focused on discovering the unity of life. Nirvana is not so much a goal but rather an awareness that it encompasses the whole of life: sin, desire, joy, laughter, love, despair.

About ten years ago I cleared off my over-stacked bookshelves and kept only those book that mean the most to me. The ones I will come back to again and again. Siddhartha is one of them.

Published on October 30, 2015 07:30

October 20, 2015

Book Review (sort of): A Game of Thrones

I’m still trying to figure out why it took me 11 weeks to read A Game of Thrones. Yes, it’s a long book, but George R.R. Martin certainly keeps things moving. The story is gripping, the characters are fascinating, the whole freaking world feels richly weighted with detail. It’s a great read, and I’m definitely planning on continuing the series.

I’m still trying to figure out why it took me 11 weeks to read A Game of Thrones. Yes, it’s a long book, but George R.R. Martin certainly keeps things moving. The story is gripping, the characters are fascinating, the whole freaking world feels richly weighted with detail. It’s a great read, and I’m definitely planning on continuing the series.So why did it take 77 days? Granted, I’m a slow reader. In elementary school, when we would practice faster reading because it was supposed to improve retention … well, that never worked for me. And so without shame, I claim it completely: I read slowly. And I enjoy it. It gives me a chance to pay particular attention to the writer’s language. Sometimes I will go back over sentences or paragraphs because the writer is teaching me a new way to express an emotion. So, there are definite benefits involved.

I might be a lumberjack

I might be a lumberjackor a sea captain,

but actually

I'm a bestselling authorPlus, I’m rarely reading one book at a time. That is due to my distractibility. There’s always a new book to discover, and ooh, that cover grabs my attention, and oh, that’s a writer I haven’t read before, and wait, there’s a new book by one of my favorite authors, and that’s a subject I never thought about before so maybe it’ll be fun to learn that bit of history … In other words, I’m a curiosity hound, always tracking after something new.

So, back to A Game of Thrones. This isn’t so much a review of the book, other than to say it’s wonderful. And the ending scene makes me drool with envy (as a writer).

I haven’t seen the TV series, which certainly looks compelling. But I’ve been known to watch popular series long after their initial run. In other words, I’m a late arrival to the Buffy fan club, and I still need to watch Firefly. Back in college I watched the original Doctor Who and more recently I’ve been watching the new series (except now my Netflix subscription has ended). So, I probably won’t get to Game of Thrones until it’s available on DVD at the local library.

Pull up a throne and

Pull up a throne andI'll tell you a bloody good tale

So, despite how long it took me, I thoroughly enjoyed the book. Many kudos to Mr. George R.R. Martin. My only question is … Is there any chance of a happy ending?

Published on October 20, 2015 07:20

October 16, 2015

Book Review: Blood Work

“My name’s Matt Hawkins and I kill monsters for a living. Slay and pay.”

So begins L.J. Hayward’s Blood Work, the first in the Night Callseries, an entertaining urban fantasy that features generous doses of noir, street-fighter, vampires, and humor, with touches of Men in Black – there’s a whole other world going on right under the populace’s noses, but there are special people working the shadows to keep them safe. Hawkins hunts down supernatural beasties infesting Brisbane. With a nifty array of weaponry (holy water-infused paint balls, a night stick laced with garlic), he takes on the local vampire clans. He is something of a berserker. His impulsively violent temper has landed him some jail time as well as a court-appointed therapist. But it’s this berserker quality that serves him well in a fight.

Hawkins hunts down supernatural beasties infesting Brisbane. With a nifty array of weaponry (holy water-infused paint balls, a night stick laced with garlic), he takes on the local vampire clans. He is something of a berserker. His impulsively violent temper has landed him some jail time as well as a court-appointed therapist. But it’s this berserker quality that serves him well in a fight.

Hawkins’ teammate is Mercy, a scrappy vampire (only two years turned), who is the true muscle of the outfit. And this is where Hayward brings a fresh look at vampires. Hers are both Old World and New World creatures, who use their psychic powers to inhibit their prey. While they will drink any type of blood, they do have compatibility issues and will go into a stupor if they drink the wrong type. They also have exceptionally long adolescence, not able to pass as human until they hit fifty years. In fact, the newly turned are like awkward adolescents, not quite mastering their instincts or their powers.

But Mercy is special: despite turning vampire only two years earlier, she has become an effective fighter. Hers is a curious learning curve, as Matt teaches her how to appear human. In her cage, she wears pajamas and watches Will Smith movies, but she lacks the ability to comprehend sarcasm. Out in the street, she is a hunter. Mercy is both self-sufficient and surprisingly vulnerable, and Matt feels increasing parental concern for her safety and welfare.

"And that's where all the

"And that's where all the

cool kids go to get their

psychic powers"To complicate matters, there is Erin McRea, a private investigator hired by a mysterious client to hunt him down. As she is pulled into Hawkins’ fight with the vampires, she begins to discover all the supernatural goings-on of Brisbane. Not merely vampires but ghouls who act as snitches and dogs who are part werewolf.

While the action is definitely entertaining, it’s the personal interactions that give the story nice depth. Matt’s and Erin’s stories prove parallel: both are taking care of partners whose lives literally depend on them. Erin’s husband is dying of cancer, and Matt is the sole caretaker of a tamed vampire. With love comes responsibility, with all its costs.

Hayward knows how to bring backstory into the action. At no point does the plot come to a halt so the reader can get exposition. You learn about these characters as the story unfolds, with tempting bits of history. As Erin pieces together Matt’s past, you discover how he came to care for Mercy. And this is great storytelling: you’ve already witnessed the complexity of their relationship before you learn why they are together.

Hayward’s choice to switch between Matt’s first-person narration and Erin’s third-person POV was a little distracting at first. Overall, a fun read with nice surprises along the way.

The ebook edition had a sample of the second book in the series, Demon Dei. Just enough of a teaser to make me eager to get a copy.

So begins L.J. Hayward’s Blood Work, the first in the Night Callseries, an entertaining urban fantasy that features generous doses of noir, street-fighter, vampires, and humor, with touches of Men in Black – there’s a whole other world going on right under the populace’s noses, but there are special people working the shadows to keep them safe.

Hawkins hunts down supernatural beasties infesting Brisbane. With a nifty array of weaponry (holy water-infused paint balls, a night stick laced with garlic), he takes on the local vampire clans. He is something of a berserker. His impulsively violent temper has landed him some jail time as well as a court-appointed therapist. But it’s this berserker quality that serves him well in a fight.

Hawkins hunts down supernatural beasties infesting Brisbane. With a nifty array of weaponry (holy water-infused paint balls, a night stick laced with garlic), he takes on the local vampire clans. He is something of a berserker. His impulsively violent temper has landed him some jail time as well as a court-appointed therapist. But it’s this berserker quality that serves him well in a fight.Hawkins’ teammate is Mercy, a scrappy vampire (only two years turned), who is the true muscle of the outfit. And this is where Hayward brings a fresh look at vampires. Hers are both Old World and New World creatures, who use their psychic powers to inhibit their prey. While they will drink any type of blood, they do have compatibility issues and will go into a stupor if they drink the wrong type. They also have exceptionally long adolescence, not able to pass as human until they hit fifty years. In fact, the newly turned are like awkward adolescents, not quite mastering their instincts or their powers.

But Mercy is special: despite turning vampire only two years earlier, she has become an effective fighter. Hers is a curious learning curve, as Matt teaches her how to appear human. In her cage, she wears pajamas and watches Will Smith movies, but she lacks the ability to comprehend sarcasm. Out in the street, she is a hunter. Mercy is both self-sufficient and surprisingly vulnerable, and Matt feels increasing parental concern for her safety and welfare.

"And that's where all the

"And that's where all thecool kids go to get their

psychic powers"To complicate matters, there is Erin McRea, a private investigator hired by a mysterious client to hunt him down. As she is pulled into Hawkins’ fight with the vampires, she begins to discover all the supernatural goings-on of Brisbane. Not merely vampires but ghouls who act as snitches and dogs who are part werewolf.

While the action is definitely entertaining, it’s the personal interactions that give the story nice depth. Matt’s and Erin’s stories prove parallel: both are taking care of partners whose lives literally depend on them. Erin’s husband is dying of cancer, and Matt is the sole caretaker of a tamed vampire. With love comes responsibility, with all its costs.

Hayward knows how to bring backstory into the action. At no point does the plot come to a halt so the reader can get exposition. You learn about these characters as the story unfolds, with tempting bits of history. As Erin pieces together Matt’s past, you discover how he came to care for Mercy. And this is great storytelling: you’ve already witnessed the complexity of their relationship before you learn why they are together.

Hayward’s choice to switch between Matt’s first-person narration and Erin’s third-person POV was a little distracting at first. Overall, a fun read with nice surprises along the way.

The ebook edition had a sample of the second book in the series, Demon Dei. Just enough of a teaser to make me eager to get a copy.

Published on October 16, 2015 09:00