Rupert Matthews's Blog, page 7

August 16, 2020

BOOK REVIEW - Wetherley Parade by Richmal Crompton

I bought this book second hand as I have read other books by this author and enjoyed them. But I'm afraid that I just could not get on with this book. I gave up about half way through.

I found the writing style to be rather prissy, for want of a better word. It was all very proper and reserved. I struggled with the characters. I suppose partly because the author told us what they were like rather than allowing us to work it out for ourselves. And some of it seemed rather formulaic. The teenage boy at public school and his friend who styed in the village. The loyal, dutiful wife and the errant, wayward sister. The returning hero. And not much seemed to happen.

I guess it is more about style and setting than story. You might like it, but I did not. A shame really, as I loved Just William.

August 15, 2020

My VJ Day Story

I was not alive on the first VJ Day, but I used to know a man who was. His name was Arthur and I knew him back in the 1980s when he was an elderly man.

Arthur was the caretaker, security guard and odd job man at the little business estate in Surrey where I was working for a publishing company - one of my first jobs. Arthur was well past retirement age, but he had taken the post to keep himself busy. He was often pottering about touching up paintwork, caring for the bedding plants or helping with some task or other. When he wasn't busy, he was always to be found in his "Tool Room" reading a newspaper while drinking tea or smoking some foul smelling cigarette. He was always friendly in a reserved sort of a way, happy to gossip about people he knew. I remember that rain or shine he always wore a flat cap.

Anyway, one lunchtime I set off to walk into Guildford to get a sandwich - it was only about a ten minute stroll. Arthur came with me. We chatted about this and that - I can't really recall what but perhaps a recent football match, Arthur loved football.

A car pulled up alongside us and the passenger window was rolled down. A man with obviously Far Eastern features poked his head out asked in strongly accented English "Excuse me. Could you tell us the way to Guildford?"

Now, as it happens the road on which the car was driving led straight to Guildford High Street, it was about 400 yards away round a corner. I was about to say so, when Arthur bent down to peer in through the open car window at the three men inside.

"Are you Japanese?" he asked.

"Yes," replied the man. "We are from Japan. We go to Guildford for business."

"Right," said Arthur standing and glaring at the man. "Well, you found your f***ing way to Singapore. So you can find your f***ing way to Guildford. Now p*** off." He stared at the man until the car drove off. Then Arthur spat into the road. "Bastards!" he said with great savagery, turned and stalked off back the way he had come. When I got back he was not in his Tool Room, nor did he show up until the following day.

I learned from speaking to some of the older hands at the little estate about Arthur's history. He had been in the Royal Navy and had been captured by the Japanese at the Fall of Singapore in 1942. After being held in a prison in Singapore for a while, Arthur and others were put on a ship and taken to an island somewhere to work as slave labour. The savage treatment handed out by the Japanese led to numerous deaths from hunger, disease and casual violence. Summary executions were common. Month after month passed, with no word from the outside world. Suffering and death were constant companions for Arthur and his dwindling group of comrades. One by one they died in agony.

Then the tempo of violence suddenly increased. Food rations fell, brutality increased and executions became more common. The work ceased, and the survivors were locked into the prison camp for days on end. Arthur and his comrades were convinced that the Japanese guards were going to kill them all.

But one bright morning a truck load of men arrived at the prison gates. They were American soldiers who had come to announce that Japan had surrendered.

It took Arthur months to recover from the mistreatment handed out to him by the Japanese. When it was recovered, he rejoined the navy. He later got married, took a job ashore and ended up in Guildford so that he could live close to his son and his family. But he never forgot his wartime experiences.

As I found out that summer's day on a walk into Guildford to buy a sandwich.

July 19, 2020

Within 7 weeks they were all dead

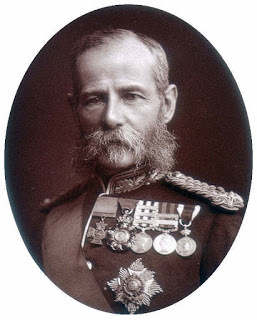

I'm reading the memoirs of Earl Roberts of Kandahar - the famous "Bobs" of the Victorian military. It is a long book and well written - but I'll write a review of it when I have finished ploughing through the pages. For now I want to comment on a quite remarkable throwaway line that occurs early in the book.

I'm reading the memoirs of Earl Roberts of Kandahar - the famous "Bobs" of the Victorian military. It is a long book and well written - but I'll write a review of it when I have finished ploughing through the pages. For now I want to comment on a quite remarkable throwaway line that occurs early in the book.Roberts is writing about the Indian Mutiny [as it was called when I was at school] and his role in it. He mentions that as a junior officer in the Quartermaster's department he was in Umballa in the early days of the uprising. He recounts a meeting that was summoned by the Commander in Chief of the British army in India - General George Anson. Present were the top five military officers in the Punjab plus their aides. Secrecy was vital so nobody else was allowed in and guards were posted outside. Roberts himself was hanging about nearby awaiting what decision would be made so that he could start his task of allocating supplies to different units. In due course the meeting ended with a decision to form a mobile column of reliable troops that would march through the Punjab to rescue isolated outposts.

Roberts then makes a remark that I found to be quite astonishing. It is a noteworthy fact, he says, that every man who was in that room would be dead within seven weeks.

We are accustomed to senior military officers spending their time far behind the lines, safe and secure. Casualties among generals are, today, rare to the point of being unthinkable. And yet here are the top five military commanders of the British army in northern India all killed within a few weeks.

Now to be fair, Anson himself succumbed to cholera rather than enemy bullets. But even so that is quite astonishing. Almost as astonishing is the fact that Roberts did not find this fact to be as remarkable as I do. It was worth commenting on, but only as a throwaway line. Casualties among generals and brigadiers was obviously only to be expected.

Clearly being a senior military commander in the 1850s was a dangerous job.

July 8, 2020

Wellington, helmets and shakos

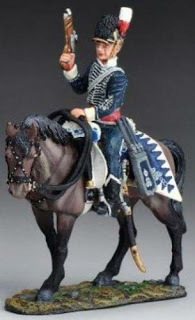

A re-enactor wears the pre-1813 Light Dragoon uniform. Note the distinctive silhouette.

A re-enactor wears the pre-1813 Light Dragoon uniform. Note the distinctive silhouette.For a work project I’ve been reading through the Duke of Wellington’s official correspondence with the government back in the UK during the Peninsular War. As you might imagine most of this is fairly routine, but one very dramatic dispute flared up in the winter of 1812-13. And just for once the Duke did not get his way.

The point at issue was the uniform of the British light dragoon regiments serving with Wellington in Portugal and Spain. The arguments raged back and forth for months, and set me thinking about what uniforms were meant to do. What purpose do they serve?

But before moving on the more generic issues of uniforms, lets have a look at the dispute between Wellington and the Army HQ.

Until the autumn of 1812, British light dragoons wore a distinctive and rather attractive uniform. The trousers and jacket were dark blue with white detailing, the boots were black and of the Hessian style. Each regiment had its own colour, which featured on the collar and cuffs. As ever the uniforms of the officers was more ornate than that of the other ranks, with additional embroidery and silver buttons.

The headgear of the British light dragoons was known as the Tarleton helmet, named for the officer who had invented it. It consisted of a rounded helmet and peak over the eyes, both made from leather boiled in chemicals to make it exceptionally hard – tough enough to turn a sword blade. Along the top, running from front to back, was a fur crest. Officers sported a feather plume on the left side and a coloured cloth – called a “turban” – tied around the base of the helmet.

This Tarleton helmet was unique, used by no other nation, and highly distinctive.

The Tarleton Helmet [officer]

The Tarleton Helmet [officer]Then the headquarters of the British Army wrote to Wellington telling him that the light dragoon uniform was changing. The blue trousers and jacket were staying, but instead of white detailing, the jacket was now to have a broad plastron in the regimental colour. A plastron is a piece of cloth that covers the front of a jacket, being buttoned down both sides and along the top. This annoyed Wellington as from the front the jacket no longer looked blue, but red, yellow, white or whatever the regimental colour might be.

The problem here was that Wellington was facing not only French troops, but also those of the allies of the French such as the Neapolitans, Wurttemburgers, Bavarians and so forth. The light cavalry of these states wore jackets of a variety of colours. Confusion was almost inevitable.

Even worse, HQ wanted to get rid of the Tarleton helmet and replace it with a shako that flared out at the top. The shako was made of felt with a leather peak. This was considerably less effective at giving the wearer protection against enemy sabres, but it was the shape that annoyed Wellington. The new-style light cavalry shako was exactly the same shape as that of the French light cavalry. Combined with the new plastron, the shako gave the British light cavalry a very similar appearance to their enemies.

Wellington was furious.

He fired off an immediate reply pointing out that the light cavalry often operated miles from the main army as they scouted around. It was essential, he said, that the uniform of the light cavalry could be recognised at a distance – often several miles away. The old all-blue uniform with Tarleton helmet was quite unlike anything else in Spain. But the new plastron and shako uniform could easily be mistaken for many other light cavalry uniforms worn by the enemy.

Army HQ was unmoved – possibly in part because the Prince Regent loved the more modern and more colourful uniform. Correspondence went back and forth, but in the end the new uniforms were issued in time for the campaigning season of 1813.

The point at issue here had been the appearance of the uniform – and in particular its appearance at a distance. Wellington was particularly annoyed by the change in the silhouette of the headgear, but the coloured plastrons also caused confusion.

The new style British Light Dragoon uniform.

The new style British Light Dragoon uniform. French light cavalry, note the similarity to the new British uniform.

French light cavalry, note the similarity to the new British uniform. Clearly one of the key functions of a uniform is to identify the wearer. In an army, that primarily means identifying the army to which he belongs. Details within the uniform give the rank, unit and specialist skills of the wearer.

In civilian life uniforms can be used to identify a police officer, firefighter, paramedic, judge or other profession. In all cases, the appearance of the uniform must be instantly recognisable to anyone who sees it. Given that many of these civilian uniforms are worn by emergency services, there is no point in wearing a uniform that requires a person to read words or look for detail. A police uniform must look very different from a paramedic, and both must be very different from civilian mufti.

As with Wellington’s light dragoons, silhouette is crucial. A police helmet is distinctive and can be recognised at a great distance. Similarly the style of a police uniform and its blue colour needs to be distinct from that of others.

Of course there is far more to a uniform than its appearance. It must also be functional. Wellington’s soldiers were out in all weathers, day and night, for weeks on end. The opportunities for changing or washing were very limited. Police officers and firefighters, by contrast, may be out in terrible weather, but they are almost certainly able to look forward to a nice hot shower at the end of their shift, and a change into a clean set of clothes before they go on duty again. As a result modern day emergency services uniforms do not need to be as robust as those of Wellington’s soldiers.

And most police officers have a car or motorbike nearby where equipment can be kept, obviating the need for all the packs, pouches and bags that soldiers used to lug about with them.

Nevertheless, some features of uniforms remain that same as they always were. A uniform needs to be instantly recognisable. A uniform needs to be distinctive and unique. A uniform needs to be weather proof. A uniform needs to be comfortable to wear. A uniform needs to be practical.

June 30, 2020

My Arrival in Fiji

ArrivalNow I never really thought I had a particularly strange name. Unusual, yes, I knew that. But not strange. Of course, some people get my name wrong just because it is unusual. I’ve been called “Bob” more times than I can remember. “Bose” is another favourite. An Italian friend insists on calling me “Boroo”. And when I went to Germany on business I was called “Bopsy”, but that might have been a joke because everyone at the meeting giggled. Not until I came to Fiji did my name actually cause me any problems. Like most people coming to Fiji, I arrived at Nadi Airport. I came in around dusk on Air Pacific and had been travelling for over 20 hours. I was tired, very tired. Knowing this was likely to be the case, I had a hotel room booked so I would not have to face anything too complicated on arrival. Get a taxi and head for the hotel. Then a quick bath and straight to sleep. Lovely! I’d leave finding the company flat in Suva until tomorrow. It could wait. Like so many others, I made my way to the immigration hall, had my passport stamped and declared that I had no prohibited animal products in my luggage. Then I slipped past the white, glass-panelled doors and grabbed my luggage from the carrousel. After again assuring a smartly uniformed guard that I had no honey, meat or bonemeal in my suitcase, I emerged into the crowded arrivals lounge. People swirled around the stark hall in an endlessly shifting pattern. Some walked with determined strides to where they were going. Others wandered about looking for family or friends. One elderly lady in a sari sat on her suitcase regarding everyone around her with complete disdain - including me. That was when I saw my taxi driver. Very nice of the hotel to send a man to collect me, I thought. And a very smart taxi driver he was too. Dressed in the bright blue and red shirt which forms the uniform of Tulip Travel, he stood watching the passengers as we drifted out of the luggage reclaim room. In his hand he held a sign reading:“Collecting Mr Bobo Worth”It was fairly close. I’ve certainly been called by many names over the years. And I have seen my name written in a variety of ways. When you read them out they always sound pretty much like my name. This was close. I’d been told the Fijians were reliable. Excellent. “Here I am,” I told the driver. “Beau Bosworth”.The driver smiled broadly. “Bula,” he said. “Nice to meet you Mr Bosworth. I am here to collect Mr Worth.”The young man had a small badge pinned to his chest telling me his name was Sanjay. “That’s right, Sanjay,” I smiled back. “That’s me. People always get my name wrong. Beau Bosworth - Bobo Worth. Same thing. See?”Sanjay grinned again. He pulled a sheet of paper out of his pocket and looked at it. He frowned. Then he smiled. “OK” he said. “No worries. You follow me, yes?”Within minutes my suitcase was safely stashed in Sanjay’s car and we were off. The car glided past the long lines of people queuing to get into the airport’s departure area, past a clump of palm trees and out of the airport. “Are you tired?” asked Sanjay.I agreed that I was, almost too tired to do more than nod my agreement. “It’s not far,” Sanjay said. “We at Tulip Travel look after our travellers. You need a nice room. This hotel has very nice rooms.”I nodded again and peered out of the car window. It was almost dark now but I could see the shapes of tall trees gliding past and, every now and then, a brightly lit shop or house. Everyone seemed to be having a good time chatting to each other. I was, I thought, going to enjoy my time in Fiji. Sanjay was still talking. “And if you want to go anywhere, you just ask for Tulip Travel. We have a man in your hotel. His name is Dhani. He is a very helpful man. We can take you anywhere. And at Tulip Travel we have guides to show you round Nadi or Suva.” Perhaps I looked uninterested - I was tired. “Or you might want to see the animals,” continued Sanjay hopefully. “Many people like the forest. Tulip Travel can take you to the forest. We have a very clever man who knows where the animals live. He will show you. Oh. Here we are.”The car glided smoothly off the road along a short drive. As soon as the car stopped in front of a welcoming doorway, Sanjay was out of his door. He had my luggage out in a second and was smiling at me. “Here we are,” he declared. Then he pointed past the approaching member of hotel staff to an empty desk set against a wall. “That is the Tulip Travel desk. Dhani is not here. He will be here tomorrow. You ask him anything. Tulip Travel are always going to help.”Well, Sanjay had certainly been helpful. I slipped him a few coins and thanked him. He grinned. “You ask for Sanjay. I look after you. Yes?”I nodded as my suitcase was expertly whisked off on a trolley by the hotel porter. I followed him to the reception desk and gave the woman on duty my name. She tapped expertly on a keyboard and studied her computer screen. She frowned and tapped some more. The woman looked up at me. “I am sorry Mr Bosworth. You have no room booked here at the Domain Hotel.”It was not what I needed. I needed a hot bath and a soft bed. I fished about in my jacket pocket and pulled out the slip of paper confirming my booking. I held it out to the receptionist.“Here,” I said. “I confirmed the room by email before I set out. Here is your reply.”The receptionist took the sheet of paper and studied it. Then she tapped on her computer again. Suddenly I realised what had happened. They must have me down as Mr Bob Worth, just like Sanjay did. That would explain it. “Try looking under ‘Worth’”, I said helpfully. “Sometimes people spell my name wrong.”The receptionist smiled at me and went back to her keyboard and my sheet of paper. She tapped some more. She nodded. She frowned. She looked at me. She said something to the porter in Fijian, which I did not understand. He laughed and wandered off through a door leaving my suitcase looking rather lonely in the middle of the entrance hall. I was beginning to feel lonely as well. The receptionist tapped some more. Finally she looked up. “Now I understand,” she said. “This is the Domain Hotel, part of the Tapoa Group of Hotels.” She looked at me as if this was going to mean something. It didn’t, of course, because I was almost asleep and wanted my room. She realised that she was going to have to explain more. “You are Mr Bosworth. You have a room booked at the Nadi Sun Hotel, also a part of the Tapoa Group of Hotels. Vilimoni will drive you there. It is not far.” Even as she spoke the porter came back carrying a bunch of keys. He took hold of the trolley and began pushing it towards the front doors. I turned to follow him, eager to get to my hotel. “Oh yes,” I heard the receptionist say. “Mr Beau Bosworth, a room at the Nadi Sun. Here it is on the computer. It is Mr Bob Worth who has the room here at the Domain. I wonder where he is.”And that was when I realised what I had done. I had been so convinced that Sanjay had got my name wrong that I had not stopped to think. I suppose it was because I was tired. While I was being whisked off to my wonderful hotel room there was a Mr Worth standing around at Nadi Airport looking for his taxi.I knew I should tell Vilimoni the porter to go to the airport to collect Mr Worth, but right now I needed a bath. I’d tell him when we got to the Nadi Sun. I hoped Mr Worth would see the funny side. Well, perhaps.*****************

Note that this is a fictional short story written for a newspaper in Fiji.

The Cog - a medieval ship

A cog, the type of ship used most widely in northern waters during the 14th Century. The ship was primarily a merchant vessel which had a large hold to carry cargo and needed only a relatively small crew to operate. In times of war these ships were fitted with temporary platforms at bow and stern, as here, from which armed men could gain the advantage of height over those on the decks of enemy ships.

The Siege of Tiverton begins 1645

After his setback at Sourton Down, Sir Ralph Hopton won a stunning victory for the king in Cornwall at Stratton. Thereafter, apart from Plymouth, Devon was free of Parliamentarian soldiers for two years. By 1645, however, King Charles I had been doing badly throughout the rest of England. In September the key port of Bristol surrendered to Parliament. With Bristol captured and the king’s army routed at Naseby, Parliament felt able to send forces into Devon once again. They put in command of the campaign their most feared commanders, Lord Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell.

On 17 October the columns of Fairfax’s army were seen approaching Tiverton. The Royalist garrison abandoned the town as being too weak to be defended and retired into the castle. Fairfax and his men entered the town, took up lodgings and at once began to reconnoitre the castle and its defences. The castle of Tiverton had been built in 1106 and although it had been regularly updated since, it was far from being a modern or a powerful fortress. By 1645 modern artillery was able to smash even the stoutest stone walls given enough time and ammunition. All the garrison could hope to do was hold out until either help came or the Parliamentarians gave up and left. Neither was very likely.

By noon on 18 October Fairfax had got his artillery into position both here and on the west bank of the Exe, so that his fire could attack both sides of the castle at once. The gunners opened fire immediately, but one of the first buildings to be hit was not the castle, but the nearby Church of St Peter. A chantry chapel, famously the finest in Devon, was reduced to rubble. Such damage obviously did not bother Fairfax’s gunners too much for the church continued to take hits from cannon balls.

Despite the pounding they were receiving, the Royalists held firm. According to the conventions of the day a garrison was given two chances to negotiate a surrender. The first came when the attackers first arrived. At this point an agreement might be reached to surrender by a specified date unless help arrived. This would avoid the need for any actual fighting and was often welcomed by both sides. If an early date was agreed, it was usual for the garrison to be granted generous terms, perhaps allowing them to leave with their weapons and possessions so that they could rejoin their army elsewhere. If the attackers were faced by a long delay, however, they might insist that the garrison be taken prisoner. The details could be many and varied, and the talks could drag on for days. At Tiverton the garrison refused to negotiate at all, so a fighting siege was begun.

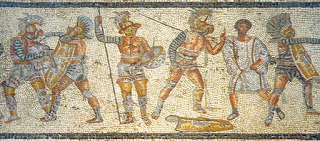

The key figure in the gladiator industry was the lanista.

The key figure in the gladiator industry was the lanista.

The man known as the lanista was the owner and business manager of a troupe of gladiators, or familia gladiatoria. The gladiators were housed and trained at the school, the ludi gladiatori. The trade of a gladiator, and by extension that of the lanista, was considered rather disreputable in Roman society. A decent Roman citizen looked to earn a living with his brain or his skill, perhaps as a lawyer or a jeweller. Those who hired out their entire bodies for money were looked on as having sold themselves unworthily. Slaves fell into this category, as did prostitutes, actors and gladiators. It is not surprising, therefore, that most people who followed these despised trades actually were slaves. Even the lanista was as often as not a former slave desperate enough not to have the fine scruples of a citizen about what he did.

The lanista made his money by hiring out his troupe of gladiators to those who wished to stage a gladiatorial display, usually as part of a munus for a deceased relative. The scale of charges would be carefully worked out in advance and were subject to extensive negotiations between the lanista and his customer, known as the editor of the games. Not only were charges made for the number of gladiators appearing, but highly skilled fighters would cost a lot more than raw recruits. The types of gladiator used would also affect the price.

Most expensive of all would be the death of a gladiator. If a gladiator was killed during a munus, the lanista lost a valuable commodity which he would no longer be able to rent out. The lanista may have invested months or years of training, food and keep in the gladiator, all of which he would expect to be reimbursed for as well as the lost revenue of future rentals. For an editor to have gladiators fight to the death was an expensive business.

Gladiators who were killed in combat or died later of wounds were often charged to the lanista, but those gladiators who surrendered and asked for mercy were the responsibility of the editor. It was his decision whether a defeated man was granted the missus and allowed to live or was put to death in the arena. When a man appealed for mercy the watching crowd would make their feelings clearly known to the editor. They might have suggested mercy by holding up a clenched fist or they might have suggested death by shouting “hoc habet”, ‘let him have it’, or by making stabbing motions with their thumbs. An editor wishing to gain favour with crowd would have been inclined to grant their wishes, but killing too many gladiators might have cost a fortune. Mercy was often tempered with cold financial calculation.

It is worth mentioning the dispute over the signal used by Romans keen to decide the fate of a defeated gladiator. For many years it was thought that the thumbs up sign indicated the man was to live and the thumbs down sign that he was to die. It now seems more likely that hiding the thumb within the fist meant the sword should be sheathed, thus granting life, while a vigorous stabbing motion with the thumb indicated that the sword should be used. Whether that involved jabbing the thumb up or down appears to have been irrelevant.

In any case the final decision lay with the editor. There was little room for confusion in his signals. If he waved a handkerchief it meant the missus was granted. A derisory sweep of the bare hand, however, meant death.

As well as the cost of the gladiators, the lanista could charge for any extras, such as a suitably impressive parade chariot on which the editor could arrive to impress the crowd. The lanista usually had a whole host of other props available, including richly embroidered cloaks for the editor’s family, special parade armour for the gladiators to use before entering combat, flags, banners and cushions to aid audience comfort.

A Gladiator Puzzle

Gladiator Puzzle

Three gladiators named Marcus, Antonius and Maximus prepare to enter the arena. They have the choice of three weapons: a straight sword, a curved sword and a spear. They also have the choice of three shields: a square shield, a rectangular shield and a round shield. Maximus takes the spear, but not the round shield. Antonius is not the man who takes both the curved sword and the square shield. Who uses what weapons and why?

Scroll down for the anwer

Answer:

Marcus has the curved sword and square shield.

Antonius has the straight sword and round shield

Maximus has the spear and rectangular shield.

If Maximus takes the spear he cannot be the man with the curved sword and square shield. Neither is Antonius, so it must be Marcus. The man with the round shield is not Maximus, nor is it Marcus, so it must be Antonius. That leaves Antonius to have the straight sword and rectangular shield.

Farming in Ancient Egypt

Nilometer

Every year the river Nile flooded. The flood waters spread fertile silt over the fields and deluged them with water. The water was trapped behind dams and in deep pits so that it could be used to water the crops in the dry months that followed. If the floods were not high enough the crops might not grow properly. Nilometers were gauges that measured how much the river rose at flood time.

Field boundaries

Each farmer and landowner had their own fields to farm, but canals that carried water from the Nile were shared between various people. There were many disputes between farmers about how much water they could use and who was responsible for keeping the canals in good condition.

The Shaduf

Water was lifted out of the canal to be poured on to fields by means of the shaduf. This is still used in Egypt today. It consists of a bucket attached to a long pole which has a heavy weight at one end. The farmer fills the bucket with water. Then he swivels the pole around, balancing the weight of the water with the counterweight.

Egyptian Crops

The most important crops grown in ancient Egypt were grain such as wheat and barley. Other crops included grapes, onions, garlic, cucumbers, leeks, cabbages and melons. Cattle, sheep and pigs were also kept for meat or milk.

Hunters

The Egyptians enjoyed eating meat from wild animals. Birds were hunted by throwing sticks or stones at them, while men with spears hunted hippopotamus in the Nile. Antelopes, gazelles and hares were hunted in the desert areas.

Egyptian Houses

Egyptian houses were built out of bricks made by drying mud in the sun. They had flat roofs and small windows. Most families had only a room or two in their house, but noblemen had much larger houses with a small shrine attached and storerooms for keeping food and drink.

Quiz Question

What did a nilometer measure?

Activity

Make a Menu

You could design an Egyptian menu for your family dinner.

You will need:

A sheet of paper

Coloured crayons or pencils

Find out what you are going to have for dinner. Now write out the list of foods and decorate it with pictures drawn in the Egyptian style, as seen in this book.