Rupert Matthews's Blog, page 6

September 1, 2020

Tactics at the Battle of Falkirk 1298

At Stirling Bridge, Wallace had deployed his men in the revolutionary tactical formation known as the shiltron. This was a circular formation of about a thousand men which could move slowly without losing order. When attacked by cavalry, the men on the outside of the shiltron knelt down and braced their spears against the ground with the sharp points projecting outward. This formed an impenetrable hedge of spikes from behind which the rear ranks could thrust at enemy cavalry. The previously unstoppable charge of heavily armoured knights could thus be halted.

At Falkirk, Wallace again deployed his main body in shiltrons, formed up on the slopes in front of Callendar Wood. The few cavalry he had were placed behind the shiltrons and the archers interspersed in pockets among and between the shiltrons. His plan was to lure the English cavalry into charging against the shiltrons where they would be halted by the spears, shot down by the archers and then tumbled into defeat by a counter charge from his own knights. With the English knights defeated, Wallace hoped, the rest of the English would retreat as they had done at Stirling Bridge. To further ensure the charge of the English knights was disrupted, Wallace placed his men behind a small burn which had marshy banks.

The tactics of the various elements of the English army would be much the same at Falkirk as at Stirling Bridge, but with one crucial difference. Up until this time it was usual to spread the archers evenly through the army and rely on their skill at aiming to shoot down enemy troops. But Edward had been listening to his commanders who had been defeated at Stirling Bridge and he knew the key to victory was to defeat the apparently impervious shiltrons.

Edward reasoned that the shiltrons were invulnerable to a traditional charge of armoured knights, but only so long as the infantry formation held firm. Once the formation was disrupted, a cavalry charge would succeed. He knew that the archers at Stirling Bridge had tried to pick holes in the Scots ranks, but had failed. Edward decided to try a new archery tactic.

He ordered his Welsh archers not to bother aiming at individual enemy soldiers at all. He reasoned the shiltrons were so closely packed with men that an arrow hitting roughly the right area was bound to find a target. Edward told his men to concentrate on the speed with which they could shoot, not on accuracy. Then he bunched his archers into large formations of over 2,000 men each. So many men shooting rapidly in the same direction would create an ‘arrow storm’ which would lash an area of ground like a sudden storm of rain.

The Crecy Campaign 1346 : Fire at Beauvais

Beauvais Cathedral, which escaped the flames

Beauvais Cathedral, which escaped the flames

Once the English army was north of the Seine, the pace of the campaign began to speed up.

Again it is not entirely clear exactly what Edward was intending to do. On the day that Edward arrived at Poissy, Sir Hugh Hastings and the Flemings had finally marched out of Ypres to attack Mervilles. By the time Edward had got his army over the Seine the Flemings had advanced as far as Béthune. The obvious move for Edward was to march north to link up with the Flemings, then turn to face the French army of King Philip.

However, Edward probably did not know where Hastings was, nor what he was doing. The territory between Béthune and Poissy was firmly in the control of the French. Armed men guarded all the bridges and key road junctions. The chances of a messenger getting through between Edward and Hastings were slim indeed, so slim that it is likely neither commander considered even sending one. Getting a message through by way of the sea was even more problematic. Grimaldi’s ships had been patrolling the Channel since the start of August. It seems that the last contact Edward had with English ships had been at Caen.

Of course, Edward knew that Hastings was supposed to be marching south by way of Béthune, but given the instability of the Flemish alliance it was by no means certain that he was. Certainly to risk the safety of an entire army on what somebody was meant to be doing would have been very dangerous.

The chronicler Jean le Bel states that when marching north from Poissy “his chief intention was to lay siege to the strong town of Calais”. This was written some years after the event and may have been a case of talking with hindsight, though it cannot be discounted entirely.

There is just one fact which indicates what Edward might have been planning. Before leaving Caen, he had sent orders back to England asking for supplies of bows, arrows, food and men to be sent to join him at Le Crotoy by the end of August.

Le Crotoy was a small port on the north shore of the estuary of the River Somme. That put it in Ponthieu, the small county which Edward had owned before the war began and which he had visited several times during the years of peace. When he gave these orders they may have been nothing more than a contingency plan. By 16 August, however, the rendezvous at Le Crotoy might have become critical.

Although Edward had got north of the Seine, his situation was still serious. The army’s food was running low, though starvation was still some way off. He was being dogged by a superior army, and as yet no place suitable for English tactics had yet been found. Just as Edward had probably considered using the rendezvous with the fleet at Caen to go home if things were going wrong, perhaps he now saw the meeting at Le Crotoy in a similar light.

Alternatively he may have been hoping for a sympathetic reception in Ponthieu. After all he knew and was friends with several of the local landowners and noblemen. Ponthieu might offer a haven in which to rest and resupply the army.

Whatever Edward’s aims were, they depended on staying ahead of the French army and on getting across the Somme. He had to march quickly.

On 18 August, the English reached the rich and prosperous city of Beauvais. The Prince of Wales thought he could take the city, and sent a messenger back to the king asking permission. Edward refused, telling his son that since the French were following it was no time to think of plunder. Despite this, some of the prince’s men did slip into the faubourgs and abbeys outside the walls to engage in some private looting. Twenty of these men had the misfortune to be leaving the Abbey of St Lucien as the king himself was riding past.

Stressed by the way the campaign was going and already peeved by his son’s behaviour, Edward was in no mood to be lenient. He ordered the men to be arrested and, as a tell tale trail of smoke showed that they had fired the abbey, he had them hanged on the spot. The bodies were left dangling from roadside trees past which the rest of the English army passed, making it very clear what would happen to those who disobeyed orders.

Photo : By Diliff - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The Wars of Rameses II

Rameses II 1304-1237bc

When Sety died the Hittite King Muwatallis, who ruled what is now Turkey attacked Egypt. He hoped that the young Rameses would be too weak and inexperienced to resist. The Hittites captured the key fortress city of Kadesh on the Orontes. Rameses led an army of 20,000 men, divided into four divisions, north to face the Hittites

Rameses believed the reports of two Hittites who claimed to be deserters, but were really spies, that Muwatallis was at Aleppo. As Rameses and the Egyptian army marched passed Kadesh they stumbled into an ambush. The first division of the Egyptian army was destroyed, but the second and third were rallied by Rameses himself. Galloping about in his chariot, Rameses put fresh heart into his men and led a charge that drove the Hittites back in defeat.

Rameses II was enormously proud of his feats at the Battle of Kadesh. He had carvings showing him in action carved on to temple walls throughout Egypt. However, the Hittites were a rich and powerful nation. The war dragged on for years. It finally ended in a peace treaty that established a boundary between the two empires and pledged them to support each other if a third force attacked either. To seal the treaty, Rameses married Manefrure, a daughter of Muwatallis.

Meanwhile, Rameses had been fighting wars in Nubia to the south of Egypt. This was another area that had slipped away from Egyptian control. Rameses defeated his enemies and re-established Egyptian power in the area.

Wars came to an end once Rameses had defeated his enemies and established secure borders for the Egyptian Empire. For the final 20 years of his reign, Rameses concentrated on building vast temples and palaces.

Conquest timeline

c.1314bc Birth of Rameses

1292bc Rameses becomes Pharaoh

1288bc Battle of Kadesh

1257bc Treaty with Hittites

1237bc Death of Rameses

Photo By Speedster - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The Armies at the Battle of Cardigan / Crug Mawr in 1136

The rival armies that met outside Cardigan were quite different in character, but not in numbers. Both sides had managed to muster around 10,000 men for this final and greatest effort of the campaigning season.

Stephen the Constable could have sheltered behind the walls of Cardigan, but instead he chose to march out to face the enemy. He must have had confidence in his chances of victory to do so and he did have good reason to anticipate success. A few months earlier an English army had sallied out from Kidwelly Castle and driven off an attacking Welsh force with ease.

Stephen’s army was made up of around 2,000 heavily armoured cavalry, some thousand or so Flemish mercenaries and a large number of English infantry. There can be no doubt that he believed the heavy cavalry to be his main battle-winning force and he was to choose the battlesite for their benefit. Each man was mounted on a large horse, using a high saddle and long stirrups to ensure he had a firm seat from which to fight. Most knights were armed with lance and sword. The lance was used in the charge for shock impact, while the sword was more use in the confused scrum of a disorganised melee. The men were protected by a helmet of solid iron and a coat made of interlinked rings of iron, a material known as mail. Most carried a large shield which had a long pointed base, though a few would have been equipped with the more modern short shield.

When a force of these knights formed in a solid mass four riders deep and were able to charge across an open field they were virtually invincible. Cohesion and momentum were everything. In more than one battle a force of knights simply rolled over the opposition without needing to draw sword.

The Flemish mercenaries were a highly respected force of professional soldiers. Thousands of Flemings served in armies right across Europe at this time. Each man was equipped with a triangular shield and armoured with a short mail jacket and simple helmet. With this defensive armour the Flemings could form a solid bastion of infantry on the battlefield that was proof against everything except a well co-ordinated charge of knights. the men were armed with stout spears around 12 feet long and with short swords or daggers. They tended to be used to defend tactically important positions, such as fords or hill crests, while the cavalry charged and other infantry manoeuvred.

The bulk of Stephen’s army was made up of English infantry. At this time the majority of such infantry were semi-professionals. They may have been raised as a feudal levy from ordinary farmers, but most underwent basic training and those serving in Wales tended to do so for cash payments. They were equipped with round or kite-shaped shields together with a helmet of iron or hardened leather. Some wore coats sewn with metal scales, but none would wear the more effective, but more expensive, mail. These men were the cannon fodder of a medieval battle. They were useful for attack or defence, but lacked the striking power of knights or the steadiness of heavily armoured mercenaries.

Owain’s army was made up of around 6,000 trained men of the army of Gwynedd and 4,000 local men. Like the bulk of the English, the men of Gwynedd were semi-professionals. They were younger sons and ambitious farmers who went to war for cash and loot. Most were equipped with shield and spear and the majority had helmet and short sword. They would form up in solid masses to push forward or fall back as a unified whole. The army of Gwynedd fielded around 2,000 cavalry. Although some wore mail armour, these men were not as heavily armed as the English knights, largely because they rode Welsh ponies rather than large chargers. They lacked the impact power of the heavy knights, but had the ability to manoeuvre swiftly, darting here and there across a battlefield with lightning speed.

The local men from South Wales served under their chiefs: Hywell ap Maredudd, Madog ap Idnerth and Gruffydd ap Rhys. These men were lightly armoured and few, if any, had a helmet as well as a shield. Many had neither. The better equipped men on both sides must have looked askance at these farmers and herdsmen who had joined up out of sheer enthusiasm. But these men were those who came with the peasant’s weapon of the longbow.

Cardigan was the first time that longbows were seen on a battlefield in any numbers. They were, essentially, a hunter’s weapon well suited to the long open moorlands of central and southern Wales where range and hitting power were essential. The English used shorter and less powerful bows better suited to hunting in woodland. Exactly how many men came armed with longbows in unclear, but it seems to have been about half the local volunteers - around 2,000 men in all.

Most of the English infantry were equipped with helmet, shield and sword but lacked much in the way of body armour. They were trained to form up in a dense "shieldwall" formation with their shields overlapping and their spears jabbing at the enemy over the shields. Most of these men carried a sidearm such as a short sword, axe or mace for use if the spear broke. The more professional Welsh infantry would have been similarly equipped.

A longbow archer at this date was entirely unarmoured, but he didhave a sword for close fighting. He had his spare arrows tucked into his belt, which was usual at this time. Because every archer had to provide his own arrows, and as each arrow could cost more than a day's wages, they tended not to have very many arrows on the battlefield.

Most Anglo-Norman knights in Wales at the time wore a style of armour that was becoming old fashioned. The conical helmet was made from several pieces of hammered iron and could be vulnerable along the joints. The mail shirt reached to the knees and elbows and the long shield protected the left side of the body to the feet. The lance was fairly light by later standards and could be used overarm for jabbing as well as underarm for charging. All such men carried a sword for use at close quarters. The horses were trained to remain calm amid the noise of battle, even when blood could be scented.

A more modern style of mounted warrior had armour that would have been considered the latest thing at the time of the battle. The mail shirt is augmented by mail leggings and armoured boots. The helmet is made of one piece of metal, making it stronger than earlier models though its flat top makes it vulnerable to an overhead blow. The shield is now smaller, enabling the man to use it on either side of the horse which was useful in a confused melee. He would have carried a lance as well as a sword.

Photo By Cered, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

When Bloody War came to Canon Frome, Herefordshire

The Herefordshire village of Canon Frome is difficult to find. It is well signposted enough, down a lane off the A417 to the east of Hereford itself, but one searches for the village in vain. In fact Canon Frome consists of a manor house, a parish church and a number of farms and houses scattered over several square miles of gently rolling countryside made up of a patchwork of fields and woods. It is about as quietly rural as a quietly rural area gets in 21st Century England.

It was not very different back in the 17th century, though if anything it was even quieter due to the lack of motorised traffic and tarmac highways. But in June 1645 bloody war came here as the closing stages of the English Civil War brought sudden death and bloody wounds to this quiet corner of England.

The Commanders at Canon Frome

The Royalist garrison at Canon Frome was commanded by Colonel John Barnard, a Royalist from Lichfield. Barnard had joined the king's army as soon as the war broke out, volunteering for the Earl of Chesterfield's Regiment. This was a mixed body of Horse and Foot, with Barnard serving in the infantry section. For the next 18 months Barnard had a fairly quiet war, commanding detachments of the regiment as they served in garrison duty at various places around Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire.

In 1644 Barnard and his detachment took part in the Battle of Newark. In December of that year Ferdinand Stanhope, son of the Earl of Chesterfield and colonel of the regiment, was killed in battle. The regiment was then divided in two. The Horse were kept by the King, but the Foot was put under the command of Barnard who was thus promoted to the rank of Colonel. Barnard's force was by this date very under strength, so the king gave him a hundred or so Irish volunteers as reinforcements and then sent him to Hereford.

Arriving in Hereford, Barnard set about reorganising the somewhat run down and relaxed condition of the local garrisons. This went down badly with the garrisons, who had been enjoying a peaceful war to this date, and even worse with the local population. Barnard's orders included an instruction to extract as much tax money as possible from the county for the king's coffers. He had full authority to levy fines on anyone he thought might be shirking his duty to the king, and many fines were levied. Adding to the financial annoyances, the local people were none too impressed by the behaviour of the Irish. They were Catholics in a Protestant land, spoke a foreign language and - or so it was said - drank too much. Barnard was not popular, but it must be admitted he did the job the king had sent him to do.

When Barnard heard that a Parliamentary army was approaching he decided to take refuge in the best defensive position to hand, and that was Canon Frome Manor.

The commander of the approaching Parliamentary army was Alexander Leslie, Earl of Leven. Leslie was a veteran soldier with a formidable reputation. He had been born in 1582, the illegitimate son of Leslie of Balquhain and a woman described only as a "wench from Rannoch". His father gave him an education, then in 1605 packed him off to earn his living as a mercenary in European armies.

Leslie served for three years in the Dutch militia as a captain, then transferred to the Swedish army. By 1627 Leslie had worked his way up to be a full colonel and was knighted by King Gustav Adolphus. He was then sent to command the city of Stralsund, then under siege by the forces of the Holy Roman Empire. Having gained the victory there, Leslie returned to Scotland to raise an entire army of mercenaries for Swedish service.Back on the continent by 1636 Leslie won the Battle of Wittstock, inflicting a key defeat on the Empire. The battle involved Leslie sending part of his army on a lengthy flanking march which allowed them to erupt from a forest to attack the rear of the enemy army. This was a bold move, which cemented Leslie's reputation as a commander of skill and daring who was able to maintain strict discipline among his men.

In 1638 the Scottish government - at this date entirely separate from the government of England although both countries shared the same monarch - offered Leslie command of the Scottish army. Leslie returned to Scotland to take up his new and lucrative position. He brought with him Scottish veterans of the continental wars, together with a huge quantity of arms and ammunition.

Leslie found himself arriving in a tense and difficult political situation. King Charles I was seeking to impose English church organsiation and liturgy on Scotland. The Scots wanted none of it and riots broke out in several places. In 1640 Scotland went to war with England, technically meaning that the Kingdom of Scotland was in rebellion against its own monarch. Leslie led the Scottish army into northern England and won a series of small but impressive victories culminating in the Battle of Newburn Ford on 28 August 1640.

When the English Civil War broke out, Scotland was at first not involved. In 1644, however, Scottish Royalists rose in rebellion against the Scottish government which was providing material aid to the English Parliament. That uprising was put down by the spring of 1645, and the Scottish army commanded by Leslie now marched into England to fight against the Royalist forces. Leslie commanded the Scottish forces at the Battle of Marston Moor and Siege of York, before marching to the west to reduce and capture Royalist garrisons and so deprive the king of money and men.

Leslie's main objective was to capture Hereford, but as he marched toward that city he found his path blocked by the small garrison at Canon Frome.

Photo : By Bob Embleton, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The Town Walls of Chesterfield, Derbyshire

The coat of arms of Chesterfield shows as its crest a ram, the traditional symbol of Derbyshire, standing atop a mural crown, or circlet made of stone or brick. This was traditionally given only to towns with defensive walls.

From the point of view of the king, one of the key advantages of making a town a borough was that he thereby gained a fortified place, the inhabitants of which were loyal to him instead of to some local noble. If there were any civil unrest, and King John had suffered more than his fair share of that, the king could send troops to garrison a town knowing that it had defences and that it could serve as a base for operations in the area.

Boroughs were usually assessed for the militia, and some kept a town guard composed of a small number of men permanently on duty. In the event of invasion or disturbance, the inhabitants of local villages could pour into the borough to shelter behind its walls until the danger had passed.

The nature of the town walls at Chesterfield has long been a matter of controversy. Not only are there no town walls today, but there is no trace of them in Tudor or Stuart times when most towns were dismantling their medieval fortifications. However, the town’s coat of arms feature a mural crown, a crown around the helmet on top of the coat of arms that is composed of stones. This device was traditionally restricted to towns with walls, though there were exceptions.

Archeological digs in Chesterfield have shown that the hill crowned by the Church of St Mary and All Saints was formerly occupied by an iron age village and a Roman army fort. The site was naturally easy to defend, with rivers on two sides and fairly steep slopes leading up to the summit. The southern edge of the Roman fort was south of Church Lane and its eastern edge along what is now Station Road. The northern and western sides of the fort are unclear, but it probably covered about 7 acres.

The medieval town occupied much the same area as the Roman fort. What appears to have been the medieval ditch outside the walls has been found in Station Road. This was a wide, V-shaped ditch about 15 feet deep. Broken pottery shows that it was filled in during the later 15th century. If this ditch is what remains of the medieval town walls then nothing of any actual wall has survived. However, comparison with similar structures elsewhere shows what the town walls would have been like in 1266.

The earth excavated from the ditch would have been piled up behind the ditch to form a mound of earth. This served to increase the vertical distance from the bottom of the ditch back up to the ground surface. The mound would have been constrained within wooden revetments to keep it in place. On top of the mound would have been placed a wooden palisade around four feet tall. The actual top of the mound may have been left as bare earth, or may have had a wooden walkway laid on top of it. The defenders of the town would have stood on the walkway and sheltered behind the palisade when fighting any attackers. The ground immediately outside the ditch would have been cleared of trees, bushes and buildings to a distance of around 300 feet or so. This was so that no attackers could creep up to the walls unobserved.

By the standards of the mid-13th century, these walls were obsolete and next to useless. Techniques to overcome earth and timber defences were well known, so even a mediocre commander of a small army could expect to be inside Chesterfield within a day or two. Given that the town guard was likely to be as poorly put together as the town walls it may not have taken even that long. Most towns of any size had stone walls by this date, usually with towers and sophisticated gatehouses. Presumably the town walls of Chesterfield were more for monitoring those attending the market than for any real attempt at defence.

Coat of Arms: By Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?...

August 18, 2020

BOOK REVIEW - Templar's Acre by Micahel Jecks

This is a long and rambling novel. While I enjoyed it, I thought that it was a bit overlong for the story line. It could have been shortened a bit without losing anything.

One thing that I did find slightly disconcerting is that this book is a prequel to a series of books that I have not read. When some characters were introduced they were clearly much more important than some others in the book. I assume that this is because they are in the later books [chronologically] in the series. People who have read the books written earlier will think "Aha, I know this chap. He is the one who goes on to do whatever it is he does". But not having read the other books this was all a bit lost on me. Never mind. I guess most people reading this book will have read the other Templar books by Michael Jecks and will be fully on board with it.

The book successfully conjures up the lost world of the crusades and of the military orders. It manages to convey the contemporary attitudes to religion and religious warfare without being condemnatory [which must be a temptation] nor portraying the monastic killers as being overly heroic. We learn a lot about the attitudes of the men and women of the time - on both sides of the divide.

And it is a gripping story with numerous twists and turns. I really must look around for more in this series.

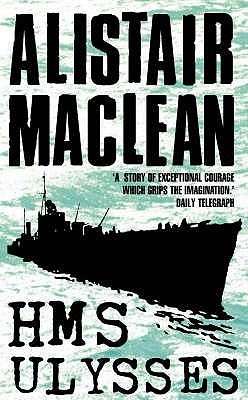

BOOK REVIEW - HMS Ulysses by Alistair MacLean

Crikey - What a harrowing read!

I picked this book up second hand in a charity shop for 50p. I grabbed it only because it was a MacLean novel that I had not read before. It is an early edition and at the time I did not realise that it was MacLean's first novel.

The book is based on his own naval experiences on the awful Arctic Convoys to Russia in the Second World WAr. I can only hope that his own war was not as terrifying and doomed as the events of this novel.

As the title might suggest, the novel followed the course of a voyage by the cruiser HMS Ulysses [a fictional ship] as it escorts a convoy of merchant ships from Iceland to Russia. It concentrates on the ship and its men - other vessels, people and aircraft are there in supporting roles only and rarely get much mention unless they impact directly on HMS Ulysses.

The ship is very well described. The weapons and abilities of the ship's radar etc are very well documented - certainly good enough for any naval buff to feel that they are getting a clear description of what it was like on such a ship. The characters of the men - and they are all men - in the book are very well drawn. A couple of them might veer towards cardboard cut outs, but by and large the men are strong and believable figures.

Of course, we all know that the Arctic Convoys were awful. During the war my grandmother was a newly married young mum. Because her house had a spare bedroom they often had homeless waifs and strays billetted on them. I remember she once told me about a merchant ship captain that they had stay with them for a few weeks after his home in some dock city had been bombed. This captain went on an Arctic convoy once. Grandma said that he told her that the Germans were the least of his worries - it was the sea and the weather that were the real enemies. And this book backs that up with its vivid description of a terrible storm at sea. Mind you, if the convoys were as bad as this book makes them out to have been, it is a wonder that anyone survived at all.

A great war novel, by a great writer.

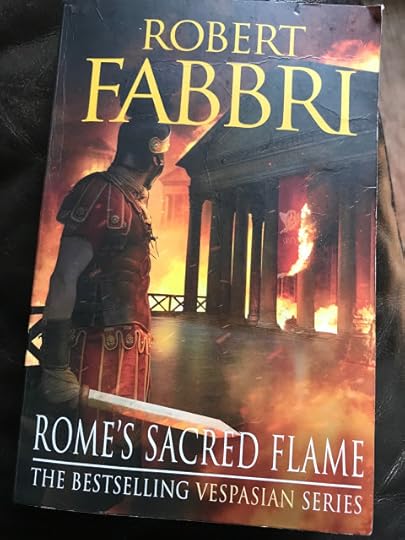

BOOK REVIEW - Rome's Sacred Flame by Robert Fabbri

This was, in many ways, a great historical adventure novel. I confess that I have not read of the other novels in this series so I came to this book about halfway the overall story arc. Fortunately the main character is Vespasian - well-known Roman Emperor so it was fairly easy to place the book in the story line of his life.

What the author seems to have done is to take what is known about Vespasian's life in this period before he became emperor, and then weave in fictional characters and events to make for an exciting action book. He has done this well.

I found the book to be well written with believable characters and a great story line(s). The action scenes were well done, and trotted along at a good pace. Certainly a cracking holiday read.

On the other hand, there were a few oddities. The book is written in four parts, with each part being a self-contained story. A couple of characters carry over from one part to another, but not the story lines. The third part seems to be the conclusion to something that happened in an earlier novel in this series. I found that unsatisfying as I could not really follow what was supposed to have happened in the earlier section.

My only real historical criticism here is that the author has included just about everything bad that was ever written about Nero. This makes him an entirely negative character. Fair enough, I suppose, but I have always wondered how Nero got to be so popular for so long if he was that bad. And the sources were all written by his enemies after his death.

But I quibble. This is a jolly good read. Enjoy it.

August 16, 2020

BOOK REVIEW - Patrol to the Golden Horn by Alexander Fullerton

I enjoyed this book. It must be said that I have always been a bit hazy about the war against the Turks in World War I. Other than Galipoli I have never really looked into it, so this book was as much an education as a diversion.

I read "Thunder and Flame" by this same author many years ago. So long ago that when I bought this book I did not realise it was the same chap. But this is now the second book by Alexander Fullerton that I have enjoyed, so I will have to look out for more.

The book really comes in two parts. The first two thirds is all about the submarine warfare in the eastern Med and Sea of Marmara in 1918 - as the war for Turkey was drawing to a close. I had no idea the fighting was as savage and widespread as it was. This section is well written and fast paced. The chracters are well drawn and believable. There is also a fair amount of techinical detail about submarines of this date which I found interesting. There was no asdic and no radar, nor any bomber aircraft operating, apparently, so much of what we are accustomed to read about submarine warfare in WW2 is not present.

The second and shorter section is all about the espionage war in Turkey, the internal politics of the Ottoman Empire and the peace negotiations. All jolly enjoyable and a cracing little adventure story in its own right. But, in my view, it was weaker than the naval part of the book. The plot line was a bit far-fetched in places while teh supposed cliffhanger was no such thing as we know that the main character survives to star in the next book in the series. Nevertheless, quite a serviceable ending to the book.

If you have never read any Alexander Fullerton, but enjoy war novels, then buy this book. It is a good read.