Rupert Matthews's Blog, page 2

January 28, 2021

A Word about Niall of the Nine Hostages

The mighty warrior king Niall Noígíallach dominates the twilight world between history and legend. He was one of the greatest of the High Kings of Ireland in prehistoric days, but one of the least known to modern historians. He gave rise to the powerful and widespread O'Neil (Ui Neill) dynasty of rulers, but even the century in which he lived is obscure. He was a pagan, but his reign prepared the way for Christianity.

That Niall of the Nine Hostages did live and did rule at least part of Ireland nobody doubts, but how powerful he really was and how he got his famous sobriquet "of the Nine Hostages" remain utterly obscure.

According to legend, Niall was the stepson of a goddess, kissed the Spirit of Ireland and had eight sons - each of whom became a king. On the last point at least the facts seem to confirm the legend. Geneticists have found that no less than 21% of men in the northern parts of Ireland share a common male ancestor who lived about 1,600 years ago. Niall of the Nine Hostages is the prime candidate for this role as progenitor of a people.

But how much of the rest of the legend of Niall of the Nine Hostages can be born out by the facts? Historians have traditionally scorned the tales of his invasion of Britain, attacks on France and assault on Scotland. But in this book I hope to show that Niall was every bit the warrior hero that the legends make him out to be, though perhaps not in quite the same way.

And the facts are there to support this.

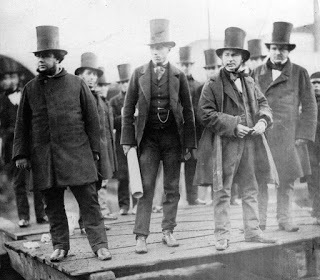

Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the Wycombe Railway

What is now the branch line from Maidenhead to Marlow, by way of Cookham, has had a chequered and patchy history. It is now enjoying something of an upswing even though the original purpose of the line was long since made redundant by the closure of part of the line.

It was on 27 July 1846 that Parliament approved the Wycombe Railway Act, which envisaged a route running from Oxford to Maidenhead by way of Thame and High Wycombe with a branch line out to Aylesbury. Almost at once the company announced that it had failed to raise the necessary money to build the line. Nothing much happened for another six years, when the Wycombe Railway Company announced that it had hired as chief engineer none other than Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the greatest engineer of his age and mastermind of the Great Western Railway. Brunel had agreed to work for the Wycombe Railway Company only on condition that he was allowed a completely free hand in the design of the railway and its works. The directors were only too pleased to agree so long as their relatively minor project got the name of Brunel associated with it.

As hoped, the arrival of the new engineer led to a change in fortunes. Construction work began, although there was only enough money to get the line from Maidenhead as far as High Wycombe. Brunel insisted on a number of special features for the new railway. The first was that it should be built to his preferred broad gauge of 7ft 1/4in, rather than the standard gauge of 4ft 81⁄2in. The broad gauge was that used on the GWR, though other railways had preferred the standard gauge.

A second stipulation was that, apart from the main station at Wycombe, all the stations had to be constructed to an identical design. These were to have a booking office at one end with an open porch or waiting area at the other. Stations that had a level crossing beside them were provided with a small house in which the crossing keeper could live. The buildings were all to be of brick and knapped flint. Brunel believed this design incorporated everything a smaller station would need, while the standardisation would help to keep costs down.

It was the third engineering decision that was to cause trouble. Brunel always had a liking for innovative design and for the tracks he chose the new and impressive, but untried barlow rails. These had been invented by William Henry Barlow, chief engineer to the Midland Railway and were being used on all the lines running out of St Pancras.

The exciting feature of the barlow rails was that they did not need sleepers. Instead of being tied to timbers at frequent intervals to keep them in position, the barlow rails relied on inertia. They took the form of an upside down V, the hollow centre being packed with sand and gravel before the rail was buried half deep in the ballast of the road bed. The technique speeded up construction and made it easier to lay out complex patterns of crossovers and points. Experience was to show that the rails were not as stable in the long term as Barlow and Brunel had hoped, but that was for the future.

In the 1850s, all seemed well for the new Wycombe Railway. Construction was completed quickly and efficiently under Brunel’s watchful eye.

On 1 August 1854 the line was opened from Maidenhead to High Wycombe. There then followed a pause to raise more capital before the line was pushed on to reach Thame in August 1862, Aylesbury in October 1863 and finally Oxford in October 1864.

The Berkshire section of the Wycombe Railway was only ever a small part of its total length. From a junction with the GWR at Maidenhead, the line curved sharply north, then ran gently downhill to the station at Cookham. The lines then ran on downhill to reach the damp, boggy watermeadows of Cock Marsh. These were crossed by a low viaduct, later replaced by an embankment. The line then crossed the Thames by way of a wooden viaduct, later replaced by an iron girder bridge. The line then entered Bourne End Station before running on through Woodburn Green to Loudwater and so to High Wycombe.

Having overseen the successful construction of the line, the Wycombe Railway Company decided to take a backseat when it came actually to running the trains. The line was leased out to the GWR, which ran it profitably until 1867 when the GWR bought out the Wycombe Railway Company.

How to Make Bosworth Jumbles

Preparation time: 12 minutes

Cooking time: 20 minutes

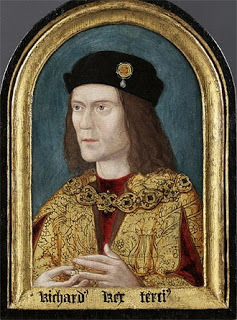

According to the version of the story I was told, these tasty little cakes gained their name from the Battle of Bosworth, fought on 22 August 1485. This was the last major battle of the War of the Roses which saw Yorkist King Richard III defeated by the Lancastrian Henry, who went on to found the Tudor dynasty as King Henry VII. Richard had gathered his army in Leicester, heading west as soon as his scouts brought in definite news of the enemy’s position. Richard camped on Albion Hill on the night of 21 August. Next morning his cook baked Richard these tasty little cakes to carry with him in a pouch so that he could whip them out for a quick snack in a break from the fighting. In the event, Richard rode out to battle before they were ready and was killed in the battle. The cakes were, therefore, scoffed up by the victorious Henry Tudor that evening. Personally I think that the original cakes must have been round, not S shaped. A thin, curly shape is not a robust one to carry around in a pouch all day. In any case, the S was a symbol of the Lancastrian cause - Henry himself wore a gold necklace of interlinked S-shaped links. I suspect the shaping of the cakes into S came after the battle as a tribute to the winner. Whatever the truth of their origin, they are very tasty little snacks - which is all that really matters.

6oz butter

6oz caster sugar

1 egg

Grated rind of 1 lemon

8oz flour

Preheat the oven to 180C Gas Mk 4.

Beat together the butter and sugar until it is white and fluffy.

Beat the egg well, then gradually add to the butter-sugar mix.

Add the grated lemon rid and stir well.

Add the flour a little at a time to form a stiff mixture.

Divide the mixture into small pieces and form into an S shape.

Place on a greased baking tray

Bake for 20 minutes or until golden brown.

Wars of the Roses billmen

Most armoured infantry during the Wars of the Roses were armed something like this figure. He wears an iron helmet and full upper harness composed of breastplate with groin plates over a mail shirt. His lower arms and hands are protected by plate armour gauntlets. His legs are quite unprotected. His main weapon is a bill, a weapon on a shaft over six feet long that combined a thrusting point with a chopping blade and sometimes, as here, a back hook to pull enemies to the ground. The bill was based on a farmer’s hedging tool and was a distinctively English weapon. He has a sword to use in case his bill breaks or for close infighting.

James Allen Ward VC

The second action that led to a Norfolk Bomber Command VC took place just three days later on 7 July. The recipient this time was a quiet school teacher from New Zealand named James Allen Ward. Ward had volunteered in July 1940, finally reaching 75 Squadron at Feltwell as a pilot in June 1941 at the age of just 21.

It was on Ward’s seventh operation that he worked his way to a VC. Ward was second pilot to squadron Leader R. Widdowson on a Wellington that was part of a force being sent to bomb Munster. The raid was carried out by 41 aircraft, ten of them from 75 Squadron and went largely without incident. The return trip took Widdowson over the Zuider Zee at a height of 13,000 feet. Suddenly he saw an ominous twin engined silhouette to his left. Recognising it as a Messerschmitt 110 nightfighter, Widdowson turned to starboard. It was a trap. Lurking beneath the Wellington was a second Me110 which now climbed up to rake the bomber from front to rear with a savage fusillade of cannon shells. The central area of the Wellington was riddled with holes, the hydraulics system punctured, the radio smashed and the starboard engine set on fire.

The rear gunner, Sergeant Allen Box, was wounded in the foot. Box forgot his wound almost immediately as the Me110 climbed past him, exposing its own underbelly. Box pumped 200 rounds into the German aircraft, seeing it fall earthwards with smoke pouring from one engine. Box tried to report back to Widdowson, but the intercom had been destroyed in the attack. Box could see the flaming engine, but reasoned that so long as the aircraft was flying straight and level the rest of the crew had not bailed out. He too stayed at his post, scanning the skies for enemy planes although he had no idea what was going on in the rest of his own aircraft.

In fact, Widdowson had decided to abandon the aircraft and ordered his crew to don their parachutes. Ward, however, had other ideas. He tore a hole in the fabric side of the Wellington and tried to put out the engine fire with an extinguisher. The foam was blown away before it could have any effect. Ward then turned to the navigator, Sergeant Lawton, and said “I think I’ll hop out to do this”. Widdowson refused to allow Ward to make the attempt, but agreed after Ward put on a parachute and tied the rope from the dinghy around his waist and got Lawton to hold the other end.

Thus equipped, Ward removed the cover from the astrodome and crawled out through the hole. He used his flying boots to kick holes in the fabric, and so get a grip on the metal struts that made up the geodetic frame of the Wellington. Slowly he worked his way down the side of the fuselage on to the wing. The main fear was that the fire would set alight the fabric covering the wing. With this gone the wing would generate no lift and the Wellington would crash. Ward intended to stuff a heavy canvas engine cover into the fire and so douse the flames, or at least stop them reaching the vulnerable fabric.

Ward slowly inched his way out along the wing until he was next to the flaming engine. Then he used his right arm to shove the canvas sheet into the hole and smother the flames. As soon as he let go, the slipstream tugged the cover free, so he pushed it back. He held it there for several minutes until his left arm could no longer stand the strain of supporting him against the slipstream. Ward let go again, and the canvas cover was whipped away. The fire was not out, but was now merely a wisp of flame. Hoping for the best Ward inched back towards the fuselage.

It was only with a great deal of pulling from Lawton that the exhausted Ward managed to get back into the aircraft. Having reported back to Widdowson, Ward collapsed in a heap. Widdowson turned the aircraft out over the North Sea, heading for the emergency landing strip near Newmarket.

The battered Wellington reached Newmarket just as dawn was breaking. With no brakes due to the smashed hydraulics system, the Wellington careered across the grass airfield and piled up into the boundary hedge. Only then did the rear gunner, Box, clamber out of his turret to ask his colleagues what had been going on. He was soon whisked off to hospital while the rest of the crew travelled back to Feltwell by lorry. Box was awarded a DFM for his coolness, while Widdowson was awarded a DFC. Ward, of course, was awarded a Victoria Cross.

Sergeant Chappie Chapman, who shared a room with Ward at Feltwell, explains what happened after the epic flight.

“After Jimmy was awarded the VC he was taken off operations for three weeks so that he could go to Buckingham Palace to collect his medal. After this we would go to the Sergeants’ mess at Feltwell and as soon as Jimmy walked in everyone would stand up and salute. Whenever this happened Jimmy would do a quick 180 degrees and walk out, he was very shy about the whole thing. But this meant that we were both living on sandwiches, so I had a word with the lads and they packed it in. At the end of the three weeks Jimmy became captain of his own aircraft; on his first trip as captain they had some trouble and landed away from Feltwell. On 15th September, when he was on his second trip, (Hamburg), he was shot down over the target and killed”.

Ancient Evidence for the Nittaewo cryptid

That the Nittaewo did once exist is almost beyond doubt, but nobody is entirely certain whether they still exist or not. Nor can it be stated with any absolute certainty just what sort of a creature this is (or was). Perhaps the Nittaewo is an unknown form of ape, or it may be a strange form of human, or perhaps it is some sort of half-way house between human and ape - the "ape-man" of this book's title.

Before trying to come to conclusions about this elusive character, it is best to look at the evidence and then see where that evidence points.

The first reference to these creatures comes in the work of the Roman historian Pliny the Elder, who wrote an encyclopedia in 37 books in about ad70. Writing about India Pliny records "Certain Indian men have mated with apes or monkeys, and have produced certain monstrous mongrels that are half-beast and half-man". The account is clearly fanciful, but it is worth noting a few things about this reference before it is dismissed out of hand.

For a start, "India" was a rather vague place for the Ancient Romans. Basically anything very far to the east that was not in the north might be termed "India". Pliny might have been talking about what we now call Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Burma or Sri Lanka. Secondly, Pliny was taking his information about India from an older book written by the Greek diplomat Megasthenes. In about 300bc, Megasthenes went to what is now Patna in northern India to serve as the ambassador of the Greek ruler Seleucus I who ruled what is now Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and neighbouring regions. On his return Megasthenes wrote a book called simply "India" in which he recorded everything he had seen or heard about in India. That book has since been lost so we do not know exactly what it was that Megasthenes said about the "beast-men", we only have Pliny's abridged version.

Battuta did not see these monkey-men himself, but he was in no doubt that they existed. He does not give a physical description of the creatures, but his account of their behaviour clearly marks them out as having a far more sophisticated social structure and levels of intelligence than the average monkey or ape. At the same time the locals in Sri Lanka clearly thought of the monkey-men as not being fully human. The only physical fact that can be deduced is that they must have had luxuriant hair if pulling it out was a punishment.

The River Mole in Surrey & Sussex

The River Mole flows for 50 miles through Surrey and Sussex, draining an area of 200 square miles and pouring an average of 192 cubic feet per second into the Thames. Here is a list of the tributaries of the River Mole

Dead River

Bookham Brook

Pachesham Brook

The Rye

Fetcham Mill Stream

Pipp Brook

Tanner's Brook

Shag Brook

Gad Brook

Wallace Brook

Leigh Brook

Baldhorns Brook

Deanoak Brook

Earlswood Brook

Salfords Stream

Burstow Stream

Spencer's Gill

Hookwood Common Stream

Gatwick Stream

Mans Brook (in Sussex)

Crawter's Brook (in Sussex)

Ifield Brook (in Sussex)

Reubens Gill (in Sussex)

Noble Families square up for a fight in Gloucestershire, 1469

The two armies that fought each other at Nibley Green were led by two of the more powerful local noblemen in Gloucestershire. They were related to each other, and it was the nature of that relationship that led to the battle.

Back in 1417, Thomas Berkeley, 5th Baron Berkeley died without a male heir. The will that he left was complex and far from clear, meaning that the vast Berkeley lands and the powerful Berkeley Castle itself did not clearly belong to anyone. His daughter Elizabeth laid claim to most of the lands, supported by her husband Richard de Beauchamp. The claim was disputed by Thomas's nephew James Berkeley, backed by his father in law the powerful Duke of Norfolk.

The tomb of Thomas Berkeley, 5th Baron Berkeley.

At first it was Elizabeth who gained possession of the lands and castle. However, in 1421 the courts decided in favour of James, who was then given the title of Baron Berkeley. Elizabeth was given a consolation prize consisting of five manors, the most wealthy of which was Wootton-under-Edge. She may have accepted the decision, but the loss rankled with her family. In 1452 Elizabeth's grandson John Talbot, Baron Lisle, led a body of armed men in a surprise assault on Berkeley Castle. He took the castle, and imprisoned Baron James and his sons. Talbot then left for the wars in France where he died in heroic circumstances at the Battle of Castillon.

Back in England, Talbot's son the 9 year old Thomas Talbot, 2nd Baron Lisle, inherited his father's lands and claims to the Berkeley Estates. Baron James Berkeley had meanwhile got free and again gone to court, where he had again secured title to the Berkeley Estates and title. He also tried to get the five manors given to Elizabeth on the apparently spurious grounds that the grant had been for her lifetime only.

Baron James died in 1463 and was succeeded by his 37 year old son William who had neither forgiven nor forgotten his short imprisonment in Berkeley Castle at the hands of John, Baron Lisle. So the William, the new Baron Berkeley, and John, Baron Lisle, resented and disliked each other from the first. In 1468 William, Baron Berkeley, married for a second time and married into the powerful Neville family, the most famous member of which was the Earl of Warwick. John, Baron Lisle, meanwhile, had married Margaret Herbert, sister of the Earl of Pembroke. Pembroke was an ardent supporter of Edward IV, just as he had been of Richard Duke of York.

The two marriage alliances thus put Lisle and Berkeley on opposite sides of the growing rift between King Edward IV and the Earl of Warwick.

Romance in Wartime

On 13 May, 1942, 57 Squadron took off from Scampton to attack a motor works. On the return journey the Lancaster flown by Pilot Officer Jan Haye was shot down over Ensched in the Netherlands. Haye, a Dutch airman who had fled to Britain when the Netherlands was overrun in May 1940, landed uninjured, but could not find his crew. He learned later that two had died and the rest had been arrested by the Germans soon after they landed.

Haye dumped his flying gear and RAF jacket before setting off to try to find help. Unknown to him the Germans had recently arrested a number of locals for helping downed RAF crew. Although the farmers he approached would not take him in, they did give him food and a bike to help him get to his own home town Hilversum. At Apeldoorn, Haye cycled past a column of German infantry, none of whom gave him a second glance. Eventually Haye made contact with a man he had known before the war and who he guessed would be actively anti-German. The man was not involved with the Resistance, but told Haye to go to The Hague and make contact with a government official named Anton Schrader, who was.

Having met Schrader, Haye was whisked off to a safe house in The Hague, where he stayed hidden for the next two months. Schrader was in charge of organising coastal barges carrying food from farms to towns and cities. He had had one barge secretly converted to carry a hidden boat that was used for various Resistance missions. Interesting as this was, Haye was more taken with Elly de Jong, the young woman in whose house he was hiding.

On 26 July, Schrader took Haye to the docks where he boarded the converted barge to meet another downed RAF pilot and several Dutchmen who were wanted by the Germans. That night the men were launched into the North Sea from the barge aboard a small rowing boat with some food and a sail. After a voyage of four days and nights they were picked up by a Royal Navy destroyer in the Thames Estuary.

Haye returned to his squadron, later transferring to the Pathfinders and winning a DFC for a later flight. As soon as Germany surrendered, Haye asked for leave and for permission to travel to Holland. He found that both Schrader and Elly de Jong had been arrested by the Gestapo in 1943 and held in concentration camps. Remarkably both survived and that autumn Haye married Elly. They lived to celebrate their Golden Wedding Anniversary in 1997.

January 27, 2021

Kingdom of Sussex - a Talk

Today I gave my talk on the Kingdom of Sussex via Zoom to over 100 people from a U3A group in Sussex.

The Kingdom of the South Saxons was once one of the key states of Britain. Founded in about 480, the kingdom remained independent for three centuries until its old royal family had to replace their title of King with that of Earl under the control of the more powerful Kingdom of Wessex. The dynasty finally disappeared under the Normans. This talks follows the political, social and economic history of Sussex during its years of independence and demonstrates how the economy and wars of that time still have an influence on the modern county.

The audience asked a string of interesting questions afterwards. Most of them were asking for more detail on things that I had mentioned in the course of the talk. Inevitably when covering 600 years of history in just an hour, much is skated over.

The audience asked a string of interesting questions afterwards. Most of them were asking for more detail on things that I had mentioned in the course of the talk. Inevitably when covering 600 years of history in just an hour, much is skated over. One question was about the mythical King Arthur and his role in Britain in the early 6th century. Arthur is a fascinating subject on which historians are divided - sometimes bitterly. I explained that some historians think him a purely legendary character and that even if he really did exist it is impossible to know anything for certain about him. Others - myself included - think that it is possible to place Arthur in a credible historical context and while it can never be proven for certain who he was, what he did nor why he was regarded as so important, the balance of probability puts him as a champion of Christianity and Roman-style culture at a time when all was crumbling in the face of pagan barbarianism.

I also offered to come back to do my talk on Arthur at some future date.

Another question concerned the system of fortified "burhs" established by King Alfred to counter the Viking invasions. I explained that the Viking raiding system depended on a swift attack, often using stolen horses, to sweep across a territory, stealing everything portable and then escape before local militia could gather to fight them. The burhs were designed as static defences into which people could go with their wealth as soon as Vikings were sighted. Moving fast and light, the Viking has no siege equipment and so could not capture the burhs. Thus Viking raids ceased to be profitable, but became more dangerous. And the Viking danger melted away.

All in all a great afternoon of history-related activities relating to Sussex in the Dark Ages and early medieval period.

If you would like to book me to give this talk to your group, email me on rupert@rupertmatthews.com.

A complete list of my talks can be found on my website: https://rupertmatthews.com/talks-in-detail