Rupert Matthews's Blog, page 4

January 10, 2021

The Battle of Hastings via Zoom

Yesterday I was delighted to give my talk on the Battle of Hastings to a Probus group via Zoom.

The year 1066 is the best known date in English history – and deservedly so. The defeat of King Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings led to the total subjugation of England under the foreign dynasty of William of Normandy. English nobles were stripped of their titles and lands, English clergy ousted from their positions and even the English language itself driven from both Court and the courts. This talk looks at the build up to the battle to explain why it was fought, at the battle itself to explain how it was won and lost, and at the aftermath to show why this one battle had such devastating long-term results.

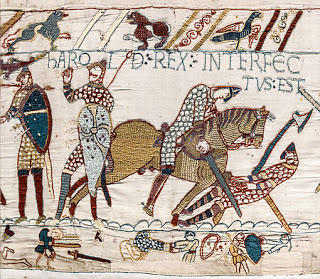

The members of the group asked some cracking questions. They were fascinated by the mystery surrounding the death of the heroic King Harold - as shown in this iconic scene from the Bayeux Tapestry.

There are two distinct accouns of Harold's death. Writing only a year or two after the battle, Guy of Poitiers names four Norman knights who killed Harold from horseback, while he was on foot and who then mutilated his body. Writing twenty years later Amatus of Montecassino says that Harold was hit in the eye by an arrow during the battle, but does not definitely give this as the cause of death. William of Malmesbury - writing in the 1120s and using official government documents as source material - states that Harold was killed by an arrow.

The traditional version of Harold's death, with him being killed by an arrow in the eye is a combination of Amatus' eye wound and William's death by arrow. Guy's account has traditionally been skated over by historians. More recently, however, Guy's version has gained popularity among academic historians who prefer it as it was written straight after the battle. They pooh-pooh the traditional account.

However the scene from the tapestry hints at a chain of events that explains all. The words "Harold Rex" are placed over the man wounded in the head by an arrow. The words "is killed" are over the figure of an Englishman being hacked down by a Norman knight on horseback. Perhaps the scene is intended [as some others clearly are] to be read chronologically. That would mean that Harold was first wounded by an arrow in the eye, and then killed by one or more Norman knights.

This solution neatly explains all the evidence - the accounts of Guy,William ad Amatus are all true, and the otherwise enigmaic tapestry panel is explained. It is also in accordance with human nature. The knights who killed Harold would naturally want to boast about having overcome one of the most famous warriors and military commanders of his age. They would not be so keen to boast of having killed a man already grievously wonded by an arrow in the eye.

I have a wide range of talks available to be given over Zoom or - when permitted - in person. See my website for details.

January 9, 2021

BOOK REVIEW - Homo Britannicus by Chris Stringer

This is an interesting book about the prehistory of humanity in the British Isles.

It tells the epic history of life in Britain, from man's very first footsteps to the present day. Chris Stringer describes times when Britain was so tropical that man lived alongside hippos and sabre tooth tiger, times so cold we shared this land with reindeer and mammoth, and times colder still when we were forced to flee altogether. TThe Ancient Human Occupation of Britain project, led by Chris, has made discoveries that have stunned the world, pushing back the earliest date of arrival to 700,000 years ago. Our ancestors have been fighting a dramatic battle for survival here ever since.

I have a few quibbles about the tone of the book. IN places it reads a bit like a pitch for more funding for his research rather than a dispassionate account. But I guess that is one side of academia these days.

January 8, 2021

RAF Typhoons in Sussex and Sir Arthur Coningham

The more established airfields were still active, with Tangmere acting as a staging post for numerous squadrons coming in and out of the area. The Typhoons of No.266 (Rhodesia) Squadron was in residence for a while. Flying Officer Norham Lucas was lost to anti-aircraft fire while firing rockets during a low pass, or so his comrades thought when he failed to form up after the attack. In fact his aircraft had been badly damaged, but not destroyed. At low altitude he managed to keep the engine running long enough to get over the Channel and find a patrol boat. He then baled out and was picked up, to get back to Tangmere that evening.

The more established airfields were still active, with Tangmere acting as a staging post for numerous squadrons coming in and out of the area. The Typhoons of No.266 (Rhodesia) Squadron was in residence for a while. Flying Officer Norham Lucas was lost to anti-aircraft fire while firing rockets during a low pass, or so his comrades thought when he failed to form up after the attack. In fact his aircraft had been badly damaged, but not destroyed. At low altitude he managed to keep the engine running long enough to get over the Channel and find a patrol boat. He then baled out and was picked up, to get back to Tangmere that evening. Meanwhile the Poles were still in action, attacking ground targets with their bombs and guns. Le Havre was attacked on 21 May, Vacqueriette on 22 May and Douai on 24 May. Next day they hit Amiens, Criel on The 27 May, Bavinche on 28 may, Abbeville on 29 May and Grenflos on The 30 May.

This remark by Coningham led to some heated debate among the Poles as to whether they were supposed to target civilian women and children as well as military and industrial targets. Coningham was forced to send a telegram next day to explain that he had meant that the pilots could attack any bridge, truck or railway that they saw, not just those they had been briefed to attack. He finished by writing “If you do see Frau Goering hanging out the washing leave her to it while you concentrate on Fat Hermann.”

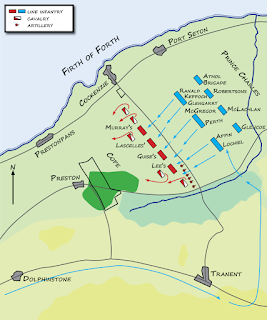

Introduction - The Battlefield of Prestonpans

The Battle of Prestonpans was fought on 21 September 1745. It was one of the most dramatic battles ever to be fought on British soil. By any objective measure, the result should have been an easy victory for the government forces, but by skill, courage and some luck the forces of Bonnie Prince Charlie swept all before them. This was a triumph for the Jacobites and a crushing blow to the hopes of the government that the rising would be put down quickly. The followers of Bonnie Prince Charlie were called "Jacobites" as they supported the claim of his father James to be King of Britain, "Jacobus" being Latin for "James".

The previous Jacobite uprisings of 1689 and 1715 had both, after initial inconclusive battles, fizzled out fairly quickly. But "The '45", as it became known, was to be a very much more serious affair. The results were to be momentous. Once Bonnie Prince Charlie had won at Prestonpans supporters flocked to his standard. While some military men advised staying in Scotland to raise money, men and munitions, while luring the Government to fight the next battle on ground of the rebels' choosing, Bonnie Prince Charlie decided to invade England with the forces at his disposal.

That invasion was to end at Derby and the Jacobites began the long retreat that was to end on the moor of Culloden in utter and total defeat. The deliberate destruction of the Highland way of life and culture that followed would have devastating effects on the clans, whether they had chosen to rise and follow Charlie or to remain at home.

Without the stunning victory at Prestonpans it is likely The '45 would have fizzled out much as had The '89 and The '15. Instead, Bonnie Prince Charlie swept on only to lead his followers to destruction. No doubt change would have come to the Highlands eventually, but it would have been slower, less violent and driven by the Highlanders themselves. As it was an entire culture was smashed and destroyed.

The two armies that met at Prestonpans could not have been more different. The Government army was modern, professional and beautifully equipped. It was led by a full time army officer with more than two decades of experience on the major battlefields of Europe. The Jacobite army was composed of farmers, herdsmen and craftsmen who had enjoyed no military training at all. They were led by a young Prince of charismatic charms but unproven abilities, assisted by a retired soldier who had not been in uniform for 25 years. The battle was in many ways a clash between not just two armies but between two cultures and two epochs. The Jacobite army was recruited, led and fought as if it were straight out of the Middle Ages. The Government Army was modern in every sense of the word, instilled with the values and teachings of the Age of Enlightenment.

The battle should have been a walkover for the modern, but in fact it was a total victory for the old. It was not only the British government that was stunned by the news from Prestonpans. All of Europe sat up and took notice. Generals, field marshals and war ministers began sifting through their manuals and textbooks looking for some sort of explanation for what had happened, and for a solution to the problem of how a rag-tag army of amateurs had trounced a fully modern army that was its equal in size.

And they shook their heads over the most amazing thing of all about the Battle of Prestonpans. From the moment the first shot was fired, to the time the battle ended, the whole affair had lasted just 14 minutes.

Attacking the Luftwaffe head-on

The 15 September 1940 again dawned bright and sunny, but this time the Luftwaffe were up early with decoys and feints. Then, around 10.40am, the radar picked up what was clearly a major formation gathering over Calais. At 11.15am No.253 and No.501 Squadrons were scrambled from Kenley and ordered to attack a formation of German aircraft coming in over the Kent coast.

The commander of No.253 Squadron, Squadron Leader Gerry Edge (who had been awarded a DFC only two days earlier), had developed the theory that attacking bombers head on was the best form of assault. The closing speed was nerve-wracking, but the tactic did make the German formation break up so that the individual bombers were easier targets. On this occasion he decided to put his plan into effect using the entire squadron.

As they raced toward Germans, the pilots of No.253 saw that the enemy formation was composed of 28 Dornier Do17 bombers with an escort of over 100 fighters. Hoping for the best, the Hurricane fighters roared in with guns blazing. As predicted the bombers began to weave and peel off as they were attacked. In all 17 bombers were hit and fell out of the formation. How many were actually shot down is unclear as the Hurricane pilots were speeding away with throttles wide open to escape the 100 fighters that were coming down fast. When No.501 Squadron arrived, the remaining German bombers jettisoned their bombs and turned for home.

Three Men in a Boat - with a cheese

In 1889 the famous book Three Men in a Boat was written by Jerome K. Jerome. The book was about three men who go on a boating holiday up the Thames. As they are preparing to set off the three men discuss what foods they should take with them. One of the men, Harris, suggests taking a whole cheese that they can carve at as they row. Another, George, objects. The narrator then tells of the time that he had an unpleasant encounter with some cheeses. He does not name the cheeses, but if they were Stilton’s they must have been well past their best. The book continues:

I remember a friend of mine, buying a couple of cheeses at Liverpool. Splendid cheeses they were, ripe and mellow, and with a two hundred horse-power scent about them that might have been warranted to carry three miles, and knock a man over at two hundred yards. I was in Liverpool at the time, and my friend said that if I didn’t mind he would get me to take them back with me to London, as he should not be coming up for a day or two himself, and he did not think the cheeses ought to be kept much longer.

“Oh, with pleasure, dear boy,” I replied, “with pleasure.”

I called for the cheeses, and took them away in a cab. It was a ramshackle affair, dragged along by a knock-kneed, broken-winded somnambulist, which his owner, in a moment of enthusiasm, during conversation, referred to as a horse. I put the cheeses on the top, and we started off at a shamble that would have done credit to the swiftest steam-roller ever built, and all went merry as a funeral bell, until we turned the corner. There, the wind carried a whiff from the cheeses full on to our steed. It woke him up, and, with a snort of terror, he dashed off at three miles an hour. The wind still blew in his direction, and before we reached the end of the street he was laying himself out at the rate of nearly four miles an hour, leaving the cripples and stout old ladies simply nowhere.

It took two porters as well as the driver to hold him in at the station; and I do not think they would have done it, even then, had not one of the men had the presence of mind to put a handkerchief over his nose, and to light a bit of brown paper.

I took my ticket, and marched proudly up the platform, with my cheeses, the people falling back respectfully on either side. The train was crowded, and I had to get into a carriage where there were already seven other people. One crusty old gentleman objected, but I got in, notwithstanding; and, putting my cheeses upon the rack, squeezed down with a pleasant smile, and said it was a warm day.

A few moments passed, and then the old gentleman began to fidget.

“Very close in here,” he said.

“Quite oppressive,” said the man next him.

And then they both began sniffing, and, at the third sniff, they caught it right on the chest, and rose up without another word and went out. And then a stout lady got up, and said it was disgraceful that a respectable married woman should be harried about in this way, and gathered up a bag and eight parcels and went. The remaining four passengers sat on for a while, until a solemn-looking man in the corner, who, from his dress and general appearance, seemed to belong to the undertaker class, said it put him in mind of dead baby; and the other three passengers tried to get out of the door at the same time, and hurt themselves.

I smiled at the gentleman, and said I thought we were going to have the carriage to ourselves; and he laughed pleasantly, and said that some people made such a fuss over a little thing. But even he grew strangely depressed after we had started, and so, when we reached Crewe, I asked him to come and have a drink. He accepted, and we forced our way into the buffet, where we yelled, and stamped, and waved our umbrellas for a quarter of an hour; and then a young lady came, and asked us if we wanted anything.

“What’s yours?” I said, turning to my friend.

“I’ll have half-a-crown’s worth of brandy, neat, if you please, miss,” he responded.

And he went off quietly after he had drunk it and got into another carriage, which I thought mean.

From Crewe I had the compartment to myself, though the train was crowded. As we drew up at the different stations, the people, seeing my empty carriage, would rush for it. “Here y’ are, Maria; come along, plenty of room.” “All right, Tom; we’ll get in here,” they would shout. And they would run along, carrying heavy bags, and fight round the door to get in first. And one would open the door and mount the steps, and stagger back into the arms of the man behind him; and they would all come and have a sniff, and then droop off and squeeze into other carriages, or pay the difference and go first.

From Euston, I took the cheeses down to my friend’s house. When his wife came into the room she smelt round for an instant. Then she said:

“What is it? Tell me the worst.”

I said:

“It’s cheeses. Tom bought them in Liverpool, and asked me to bring them up with me.”

And I added that I hoped she understood that it had nothing to do with me; and she said that she was sure of that, but that she would speak to Tom about it when he came back.

My friend was detained in Liverpool longer than he expected; and, three days later, as he hadn’t returned home, his wife called on me. She said:

“What did Tom say about those cheeses?”

I replied that he had directed they were to be kept in a moist place, and that nobody was to touch them.

She said:

“Nobody’s likely to touch them. Had he smelt them?”

I thought he had, and added that he seemed greatly attached to them.

“You think he would be upset,” she queried, “if I gave a man a sovereign to take them away and bury them?”

I answered that I thought he would never smile again.

An idea struck her. She said:

“Do you mind keeping them for him? Let me send them round to you.”

“Madam,” I replied, “for myself I like the smell of cheese, and the journey the other day with them from Liverpool I shall ever look back upon as a happy ending to a pleasant holiday. But, in this world, we must consider others. The lady under whose roof I have the honour of residing is a widow, and, for all I know, possibly an orphan too. She has a strong, I may say an eloquent, objection to being what she terms `put upon.’ The presence of your husband’s cheeses in her house she would, I instinctively feel, regard as a `put upon’; and it shall never be said that I put upon the widow and the orphan.”

“Very well, then,” said my friend’s wife, rising, “all I have to say is, that I shall take the children and go to an hotel until those cheeses are eaten. I decline to live any longer in the same house with them.”

She kept her word, leaving the place in charge of the charwoman, who, when asked if she could stand the smell, replied, “What smell?” and who, when taken close to the cheeses and told to sniff hard, said she could detect a faint odour of melons. It was argued from this that little injury could result to the woman from the atmosphere, and she was left.

The hotel bill came to fifteen guineas; and my friend, after reckoning everything up, found that the cheeses had cost him eight-and-sixpence a pound. He said he dearly loved a bit of cheese, but it was beyond his means; so he determined to get rid of them. He threw them into the canal; but had to fish them out again, as the bargemen complained. They said it made them feel quite faint. And, after that, he took them one dark night and left them in the parish mortuary. But the coroner discovered them, and made a fearful fuss.

He said it was a plot to deprive him of his living by waking up the corpses.

My friend got rid of them, at last, by taking them down to a sea-side town, and burying them on the beach. It gained the place quite a reputation. Visitors said they had never noticed before how strong the air was, and weak-chested and consumptive people used to throng there for years afterwards.

Fond as I am of cheese, therefore, I hold that George was right in declining to take any.”

The Roaring Girl of Surrey

A busy day for Sergeant Ronald Hamlyn , RAF

That bomb craters could be a real hazard was discovered to his apparent cost by Sergeant Ronald Hamlyn just after dawn on 23 August. The Spitfire had a notoriously long nose. This was not much of a problem in the air, but on the ground with the aircraft angled upward it meant the pilot had very little forward vision. Pilots were supposed to move forward in a series of sweeping turns so that the could peer around the engine cowling. As he taxied out to take off on patrol, Sergeant Hamlyn omitted to do this and drove his Spitfire straight into a bomb crater. The undercarriage was wrecked and the propeller sheared off, so that it would take days to repair the aircraft.

Hamlyn was sent to report to the Station Commander for disciplinary action. He was standing in the Commander’s ante room when at 8.25 he heard the emergency scramble bell. Hamlyn raced from the room and leapt into the cockpit of the nearest Spitfire. He joined the squadron as they climbed towards Ramsgate to meet a formation of Junkers Ju88s escorted by 109s. Hamlyn shot down an 88, then sent a 109 spinning down out of control.

When the squadron landed, Hamlyn headed back to the Commander’s office for his disciplinary hearing. Barely had the meeting begun than the scramble signal sounded again. Hamlyn raced to leap into a Spitfire and took off at 11.35. This time the intruders were over Dover. Hamlyn got into a dogfight with a 109. When the German put his nose down and fled, Hamlyn followed. He finally caught up with the German over Calais, and sent it down into the sea.

For the third time Hamlyn reported for his hearing. This time the proceedings went ahead and the hapless pilot had just been found guilty of Negligence on Duty when the alert sounded once more. Following his comrades to the Isle of Sheppey, Hamlyn bagged two more German aircraft before returning to Biggin Hill.

This time Hamlyn returned to the Station Commander’s office rather grubby and extremely tired. The senior officer sternly told him that he was being fined £5 (then a fair amount of money) for his crime – and that he was being recommended for the DFM. The medal was awarded immediately.

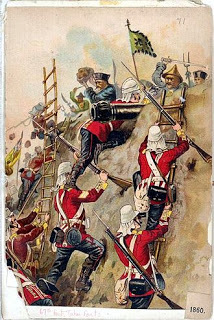

The Hampshire Regiment at the Battle of the Taku Forts

The Tuku Forts guarded the entrance to the Peiho River on which stands the Chinese capital of Beijing, then called Pekin or Peking. The forts had been first built in 1522, but over the years had been expanded and strengthened until by 1860 the fortified complex comprised five large forts, each able to operate independently, and 20 smaller fortifications. The forts are sometimes called the Taku Forts or the Tanggu Forts depending on which transliteration system is used to turn Chinese writing into the western alphabet.

In 1859 a naval flotilla tried to force a way past the forts, but failed. It was decided instead to land an army to capture the forts and so clear a way for the ships to sail upriver to Pekin. The 67th Regiment (later the South Hampshire Regiment) was then stationed in India, so it was shipped to China to take part in the expedition.

On 30 July 1860 the Anglo-French army led by Sir James Hope Grant landed at Pei Tang Ho. Hope had about 12,000 British and 8,000 French soldiers with him. Hope secured the area before a column set out towards the Taku Forts. As the column approached the fortified village of Sin Ho a large force of Tatar cavalry appeared and prepared to launch an attack. The 67th formed a skirmish line and drove the horsemen off with rifle fire. Sin Ho was then captured and the British began digging trenches and building gun emplacements around the three forts on the north bank of the Peiho.

At dawn on 21 August Hope studied the walls of the first fort and decided to order an assault to be carried out by the 67th. The walls of the fort were about 20 feet tall and in front of them was a wide moat and an extensive area of ground in front of that had been flooded to be marshy and was liberally planted with sharpened bamboo stakes. The fort mounted 15 cannon and was manned by over 1,000 men.

The 67th advanced at 7am, wading through the marsh to reach the edge of the moat. A squad of picked men was sent to swim the moat, then scramble up the walls to cut the ropes holding the drawbridge so that it would come down and enable the rest of the regiment to storm across. As the men swam over, those on the bank kept up a steady rifle fire to dissuade the Chinese from firing with their muskets from the fort’s embrasures. Six men made it and the drawbridge came down.

[image error]

Lieutenant Nathaniel Burslam led the charge over the bridge, receiving a musket ball in his chest as he did so. Burslam and Private Thomas Lane got to a small hole in the walls made by the cannon and they began widening the hole with their sword and bayonet. Meanwhile Lieutenant Edmund Lenon, and Ensign John Chaplin, who carried the Regimental Colour, were scrambling their way up into an embrasure through which fired a Chinese cannon. The Chinese defenders rained missiles down on the men, Lane being hit on the head by an artillery shell which fortunately did not detonate — his new style helmet probably saved his life.

First through was Chaplin who held off a Chinese counterattack with his rifle while Lenon squeezed through after him carrying the flag. Chaplin was wounded three times by musket balls, but carried on firing. Meanwhile, Lane and Burslam had enlarged their hole so that several men could get through at once and Burslam led a dozen men in to link up with Lenon and Chaplin. Together the men got up on to the parapet of the wall and began fighting their way towards the nearest cannon. More and more men of the 67th were now entering the fort, spreading out to capture the buildings from the retreating Chinese. The wounded Chaplin reached the pole on which was flying the Chinese flag, cut it down and replaced it with the colours of the 67th, at which point he was wounded for a fourth time. The Chinese then abandoned the fort and fled. The other two forts surrendered as soon as the British formed up to attack them.

Amazingly Ensign Chaplin made a full recovery from his four wounds. Along with Lane, Burslam and Lenon he was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions in the assault. The regiment was given the Battle Honour Tuku Forts.

October 28, 2020

Gogmagog and Geoffrey of Monmouth

When dealing with an enigma such as Gogmagog, it is probably best to start with the earliest written references to this giant. That takes us to Geoffrey of Monmouth, possibly the most controversial historian in British history.

Geoffrey was born in about the year 1100, almost certainly in Monmouth. At an early age he joined the Benedictine monastery in Monmouth as a monk, but soon his wide ranging academic interests and personal ambitions took him far from his birthplace. By 1129 he was in Oxford, studying at the nascent Oxford University. He wrote extensively, taking a deep interest in Welsh folklore, history and legend - it was Geoffrey who brought Arthur, Merlin and other such figures to an audience outside Wales for the first time.

In about 1136 Geoffrey produced the work for which he is best known. This was the Historia Regum Britanniae, or History of the Kings of Britain. It is a monumental 12 volume work that claims to be a serious history of Britain and the British (principally the Welsh) for 2,000 years or more. It makes for compelling reading, even today. Because nobody knew more about Welsh history or legend than did Geoffrey, it was widely believed to be a factual history. It's easy reading style of writing, sensational contents and academic credibility made it a best-seller. More than 215 copies have survived - and there must originally have been many more - all at a time when books had to be copied out by hand since printing had not yet been invented.

Before long doubts began to be raised about the book. Just how reliable it was as genuine history was never very clear. Geoffrey himself claimed to have simply translated a much older book, but even at the time nobody really believed this. Such a claim was a standard method of adding antiquity to one's writings. What Geoffrey had quite clearly done was to draw together history, legend and myth to create a single story. He slotted different stories, people and events into his history where he thought they probably fitted best - on what basis we don't know - and was not shy about simply making things up to help the story bounce along.

We know that Geoffrey did have access to sources that have since been lost. He talks about pre-Roman Celtic monarchs and figures which are today unknown in written sources, but who we know existed as their coins have been found by archaeologists. Where Geoffrey got this information from, we simply do not know. Crucially we have very little idea which of Geoffrey's otherwise uncorroborated stories came from genuine legends (since lost) and which he made up himself.

The other thing to bear in mind when dealing with Geoffrey's writings is that he was writing with a definite purpose: He wanted a job. Ideally he wanted a well-paid job that did not entail too much in the way of hard work. He eventually got what he wanted in 1152 when he was made Bishop of Asaph, but when he wrote he monumental history he was still very much on the scrounge.

His purpose in writing the History of the Kings of Britain was to establish the Welsh as a noble and ancient people. By linking the ancestors of Welsh noble families to the great heroes of old, Geoffrey would be flattering the people in the best position to get him a job. Geoffrey may have been an academic scholar, but he was also a man on the make.

And so we turn to the figure of Gogmagog as he appears in Geoffrey's writings. Gogmagog appears very early in Geoffrey's history, somewhere around the year 1200bc. This does not mean that he really lived at this early date (assuming he lived at all), simply that Geoffrey chose to place him there.