Mark R. Vickers's Blog, page 2

September 19, 2020

Coyotes: Reviled Varmints or Constant Compatriots?

Are coyotes varmints to be reviled or reflections of transcendent beings worth worshiping? It depends on whom you ask.

Humanity is conflicted, and perhaps always has been, about coyotes. On the pest side of the ledger, coyotes have probably always been at least a nuisance to humans who raise domesticated animals. Not long ago I watched The Biggest Little Farm, a documentary about an idealistic couple who decide to develop a sustainable farm on 200 acres outside of Los Angeles.

These folks faced a lot of different problems, but one of biggest was the coyotes that massacred their chickens. It’s one thing to hear about such events in the abstract, but the movie helps you realize just how devastating such events can be to farmers. By the time our narrator John Chester finally shoots one of the coyotes, we understand his frustration.

In the end, though, John comes to realize that if he can keep the coyotes out of the hen house (he seems to succeed by using a combination of dogs and fencing), then those same varmint animals can help control the gopher population on the farm, which is wreaking havoc on their orchards.

These sustainable farmers are far from the only people battling coyotes. Some sources suggest coyotes may result in considerable lost livestock per year. What makes coyotes so dangerous as predators is their intelligence and adaptability. It’s said coyotes will observe landowners, watching their comings and goings, to time their raids to when they’re least likely to encounter human resistance.

On the other hand, the United States Department of Agriculture reports that “the majority of the coyote’s diet is comprised of rodents and other small animals” and that “many coyotes do not prey on livestock.” It notes killing livestock appears to be a learned behavior not shared by all coyotes. In some cases, coyotes may even become “an asset to landowners by defending a territory against other coyotes and keeping other predator numbers low.”

And not just other predators. Even as far back as 1887, the Salt Lake Weekly Tribune ran an article which noted that the locals had killed off the coyotes via poison, only to watch the wild rabbit population grow to such a degree that they devastated crops. The Tribune reported that “the farmers pray for coyotes now.”

So, again, we see that coyotes can be beneficial to farmers…especially if they’re the right coyotes.

Benefits can even appear in urban settling. A study of the coyotes in Chicago’s Cook County suggests that coyotes “earn their keep eating small rodents, especially rats and voles.” Indeed, it’s thought that one reason coyotes can often be found around humans is that they’re after the rodents that inevitably come with human habitations, a tradition that dates back to at least the Aztecs.

So, despite the fact that they are still regularly poisoned, shot and trapped (a recounting of the long war waged on them is too horrific to detail) , coyotes keep finding their way into human towns and cities because that’s where they can prosper. They’re not likely to become “man’s best friend” as are domesticated dogs (which are descended from wolves), but they are likely to continue to be our compatriots, like it or not. Indeed, this relationship is an aspect of how they became such a deep part of the American mythos, as we’ll discuss next time.

Note: Featured image by USDA - USDA Wildlife Research Center media database Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by User: Quadell using CommonsHelper., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Note: Image of sitting coyote by Frank Schulenburg, Coyote (Canis latrans) in Bernal Heights, San Francisco, California.

The post Coyotes: Reviled Varmints or Constant Compatriots? appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

The Cool Coyote and Its Lame European Epithets (Part 1)

I’ve written about wolves but have so far given short shrift to their coyote cousins and the trickster god Coyote. The lines between the beasts and god are surprisingly blurred, so first let’s talk about the former.

Coyote the Canid

Coyotes belong, not too surprisingly, to genus canis (aka, canines) which is part of the family Caninae (aka, canids). Their actual species name is Canis latrans, which basically means “barking dog,” a mildly accurate but still pretty lame Latin moniker. That’s probably because the English-speaking Europeans who first ran across coyotes didn’t give them a lot of thought, tagging them as prairie or brush wolves.

Fortunately, the word coyote is much more interesting, being a Spanish borrowing from its Nahuatl name coyōtl. Nahuatl is still a language spoken in parts of central Mexico and was the language of the Aztecs. It strikes me as fitting that this species, which is unique to North America, retains at least some form of a word used by Native Americans.

The Aztecs were apparently huge fans of coyotes, having at least four different gods inspired by the beast: Coyotlinauatl, Nezahualcoyotl, Coyotlinahual, and Huehuecoyotl. The last of these translates to something like “Venerable Old Coyote,” a name that probably relates to the “Old Man Coyote,” a coyote god of the Native Americans who lived well to the north in the area we now often refer to as the Great Plains.

Coyote the Idiom

As with wolves, coyotes have crept into human language and idioms. Writing in the 1940s. Frank Dobie stated, “In modem Mexican folk sayings and other homely expressions, there are many applications of the coyote’s name and nature to human character and activity.”

The range of such expressions demonstrates the mix of feelings we human tend to have about coyotes, from respect and admiration to fear and disdain.

Sometimes coyote refers to thievery and antagonism. Dobie points to the saying, “Whoever has chickens must watch ‘for coyotes.” It not only referred to a keeper of chickens but to parents of attractive young women. Another saying is, “That coyote won’t get another chicken from me,” suggesting that someone has learned from experience.

Sometimes the term refers to someone sneaking in the shadows and carrying out illegal activities, as is the case with those who smuggle people over the Mexican-United State border. In other cases of Mexican speech, according to Dobie, coyote could refer to a “pettifogger, a thief, any kind of shyster or go-between, a curbstone broker, a fixer who has ‘pull’…”

On the other hand, coyote sometimes has positive or neutral connotations. Dobie writes:

To have “coyote sense” is to have a sense of direction that guides one independently of all landmarks, stars, winds and other externally sensible aids… More than any other animal, the vaquero people say, the coyote is muy de campo. Campo includes everything country – wilderness, desert, prairie,· brush, cactus, mountain, fields. An hombre de campo is frontiersman, woodsman, plainsman, mountaineer, scout, trailer, one who can read all the signs of nature… All of his senses are sharp, all his instincts alive. The true hombre de campo is muy coyote for, beyond all other creatures, the coyote himself is de campo.

Sometimes coyote just means shrewd without the negative connotations of crookedness. Even in English, to “out-coyote” someone tends to mean to out-smart someone who was trying to trick you. It can also be applied neutrally to refer to native plants. This is the case with coyote melon, coyote prickly pear, tabaco del coyote, and coyotillo.

All of these uses shed light on how people view coyotes. So how and why did coyote of the canid become Coyote the god? We’ll come to that, but next up I want to discuss coyote the pest.

Note: Image from Christopher Bruno - http://www.sxc.huhttp://www.sxc.hu/br..., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The post The Cool Coyote and Its Lame European Epithets (Part 1) appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

The Cool Coyote and Its Lame European Epithets

I’ve written about wolves but have so far given short shrift to their coyote cousins and the trickster god Coyote. The lines between the beasts and god are surprisingly blurred, so first let’s talk about the former.

Coyote the Canid

Coyotes belong, not too surprisingly, to genus canis (aka, canines) which is part of the family Caninae (aka, canids). Their actual species name is Canis latrans, which basically means “barking dog,” a mildly accurate but still pretty lame Latin moniker. That’s probably because the English-speaking Europeans who first ran across coyotes didn’t give them a lot of thought, tagging them as prairie or brush wolves.

Fortunately, the word coyote is much more interesting, being a Spanish borrowing from its Nahuatl name coyōtl. Nahuatl is still a language spoken in parts of central Mexico and was the language of the Aztecs. It strikes me as fitting that this species, which is unique to North America, retains at least some form of a word used by Native Americans.

The Aztecs were apparently huge fans of coyotes, having at least four different gods inspired by the beast: Coyotlinauatl, Nezahualcoyotl, Coyotlinahual, and Huehuecoyotl. The last of these translates to something like “Venerable Old Coyote,” a name that probably relates to the “Old Man Coyote,” a coyote god of the Native Americans who lived well to the north in the area we now often refer to as the Great Plains.

Coyote the Idiom

As with wolves, coyotes have crept into human language and idioms. Writing in the 1940s. Frank Dobie stated, “In modem Mexican folk sayings and other homely expressions, there are many applications of the coyote’s name and nature to human character and activity.”

The range of such expressions demonstrates the mix of feelings we human tend to have about coyotes, from respect and admiration to fear and disdain.

Sometimes coyote refers to thievery and antagonism. Dobie points to the saying, “Whoever has chickens must watch ‘for coyotes.” It not only referred to a keeper of chickens but to parents of attractive young women. Another saying is, “That coyote won’t get another chicken from me,” suggesting that someone has learned from experience.

Sometimes the term refers to someone sneaking in the shadows and carrying out illegal activities, as is the case with those who smuggle people over the Mexican-United State border. In other cases of Mexican speech, according to Dobie, coyote could refer to a “pettifogger, a thief, any kind of shyster or go-between, a curbstone broker, a fixer who has ‘pull’…”

On the other hand, coyote sometimes has positive or neutral connotations. Dobie writes:

To have “coyote sense” is to have a sense of direction that guides one independently of all landmarks, stars, winds and other externally sensible aids… More than any other animal, the vaquero people say, the coyote is muy de campo. Campo includes everything country – wilderness, desert, prairie,· brush, cactus, mountain, fields. An hombre de campo is frontiersman, woodsman, plainsman, mountaineer, scout, trailer, one who can read all the signs of nature… All of his senses are sharp, all his instincts alive. The true hombre de campo is muy coyote for, beyond all other creatures, the coyote himself is de campo.

Sometimes coyote just means shrewd without the negative connotations of crookedness. Even in English, to “out-coyote” someone tends to mean to out-smart someone who was trying to trick you. It can also be applied neutrally to refer to native plants. This is the case with coyote melon, coyote prickly pear, tabaco del coyote, and coyotillo.

All of these uses shed light on how people view coyotes. So how and why did coyote of the canid become Coyote the god? We’ll come to that, but next up I want to discuss coyote the pest.

Note: Image from Christopher Bruno - http://www.sxc.huhttp://www.sxc.hu/br..., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The post The Cool Coyote and Its Lame European Epithets appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

September 14, 2020

Politics and the Popular Appeal of Trickster Gods

While studying Coyote myths, it occurred to me that Donald Trump fits the characteristics of trickster gods to an uncanny degree.

Here’s how the Wikipedia entry on trickster gods reads:

Lewis Hyde describes the trickster as a “boundary-crosser.” The trickster crosses and often breaks both physical and societal rules: Tricksters “violate principles of social and natural order, playfully disrupting normal life and then re-establishing it on a new basis.” Often, this bending/breaking of rules, takes the form of tricks or thievery. Tricksters can be cunning or foolish or both. The trickster openly questions, disrupts or mocks authority. They are often male characters, and are fond of breaking rules, boasting, and playing tricks on both humans and gods.

In its discussion of trickster tales, Britannica states:

Simultaneously an omniscient creator and an innocent fool, a malicious destroyer and a childlike prankster, the trickster-hero serves as a sort of folkloric scapegoat onto which are projected the fears, failures, and unattained ideals of the source culture….The typical [trickster] tale recounts a picaresque adventure: the trickster is “going along,” encounters a situation to which he responds with knavery, stupidity, gluttony, or guile (or, most often, some combination of these), and meets a violent or ludicrous end.

The study of the trickster has helped me understand Trump’s allure to many Americans. Tricksters are, after all, among the most appealing personalities in mythologies. In the popular western tradition, consider our attraction to characters such Br’er Rabbit, Loki, Puss in Boots, Bugs Bunny, Bart Simpson, Woody Woodpecker and even Batman’s The Joker.

One of my personal favorites is Coyote, the most pervasive trickster in a wide variety of Native American traditions. Describing Coyote, author Dan Flores writes:

He is a god who is not merely good but also, transparently, very, very bad…Coyote is admirable, inspirational, imaginative and energetic…[but]…he is also vain, deceitful, and ridiculously self-serving. And I should add he is quite often envious, lustful to a degree of advanced, creative horniness, and possessed of an overconfidence that gets him into no end of fixes.

Some of you may take issue (perhaps vehemently) with categorizing Trump as in any way good, admirable or inspirational, but many of his supporters see him this way. Even I, who am definitely not a fan, must admit that the sheer depth and breadth of his boldness and chutzpah impresses me, being qualities I would like to see more of in myself. And, certainly he has inspired many people, even if that inspiration sometimes leads to destructive impulses such as forswearing social distancing or mask-wearing in the midst of a pandemic or denigrating freedom of the press.

But what a lot of Trump’s supporters love best about him is his willingness to cast off conventional norms and be a “rule-breaker.” This has alway been the appeal of trickster gods, their enthusiastic abandonment of the societal rules that we all chafe against. Because of this, he often retains and even enhances his popularity when he says and does outrageous things. Paying off a porn star to stay quiet about an affair? No problem, because “creative horniness” is expected of a trickster. Making fun of a disabled person in public? Hey, the rules of common decency do not apply to these gods. They are supposed to be politically incorrect in the extreme.

But how about lying to an entire nation about the danger posed by a new virus, a lie that probably causes many unnecessary deaths? Well, deceit of all sorts is expected from tricksters. Wouldn’t we all like to be untethered to the truth, to remake reality in whatever form suits our selfish needs and inflated egos?

Sometimes, of course, tricksters go too far, crossing the line from mischief to evil. Perhaps the best known case of this Loki, who finally crosses that line after one of his tricks leads directly to the death of Baldur, one of Odin’s sons. The Norse gods ultimately “forge a chain from the entrails of Loki’s son Narfi and tie him down to three rocks inside a cave…[where]… a venomous serpent sits above him” dripping acidic venom onto his face and body.

Of course, Loki’s ultimate crime is to engineer and lead the destruction of the entire Norse universe. That obviously goes well beyond making mischief.

So, has Trump crossed the line from sheer mischief to actual evil? Many would say so. After all, by some accounts, Trump’s lies and incompetent inaction have led to well over 100,000 avoidable American deaths. Of course, his staunchest supporters and allies would vehemently deny such figures. For them, Trump remains an admirable trickster who continues to excel at undermining and infuriating the despised “liberals” who oppose him. For that alone, they may forgive all his sins. We can only hope those will never include an American Ragnorak.

Note: Image is from G. Yakulov. The Costume Design for the play “The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest”

The post Politics and the Popular Appeal of Trickster Gods appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

Donald Trump and the Appeal of Trickster Gods

While studying Coyote myths, it occurred to me that Donald Trump fits the characteristics of trickster gods to an uncanny degree.

Here’s how the Wikipedia entry on trickster gods reads:

Lewis Hyde describes the trickster as a “boundary-crosser.” The trickster crosses and often breaks both physical and societal rules: Tricksters “violate principles of social and natural order, playfully disrupting normal life and then re-establishing it on a new basis.” Often, this bending/breaking of rules, takes the form of tricks or thievery. Tricksters can be cunning or foolish or both. The trickster openly questions, disrupts or mocks authority. They are often male characters, and are fond of breaking rules, boasting, and playing tricks on both humans and gods.

In its discussion of trickster tales, Britannica states:

Simultaneously an omniscient creator and an innocent fool, a malicious destroyer and a childlike prankster, the trickster-hero serves as a sort of folkloric scapegoat onto which are projected the fears, failures, and unattained ideals of the source culture….The typical [trickster] tale recounts a picaresque adventure: the trickster is “going along,” encounters a situation to which he responds with knavery, stupidity, gluttony, or guile (or, most often, some combination of these), and meets a violent or ludicrous end.

The study of the trickster has helped me understand Trump’s allure to many Americans. Tricksters are, after all, among the most appealing personalities in mythologies. In the popular western tradition, consider our attraction to characters such Br’er Rabbit, Loki, Puss in Boots, Bugs Bunny, Bart Simpson, Woody Woodpecker and even Batman’s The Joker.

One of my personal favorites is Coyote, the most pervasive trickster in a wide variety of Native American traditions. Describing Coyote, author Dan Flores writes:

He is a god who is not merely good but also, transparently, very, very bad…Coyote is admirable, inspirational, imaginative and energetic…[but]…he is also vain, deceitful, and ridiculously self-serving. And I should add he is quite often envious, lustful to a degree of advanced, creative horniness, and possessed of an overconfidence that gets him into no end of fixes.

Some of you may take issue (perhaps vehemently) with categorizing Trump as in any way good, admirable or inspirational, but many of his supporters see him this way. Even I, who am definitely not a fan, must admit that the sheer depth and breadth of his boldness and chutzpah impresses me, being qualities I would like to see more of in myself. And, certainly he has inspired many people, even if that inspiration sometimes leads to destructive impulses such as forswearing social distancing or mask-wearing in the midst of a pandemic or denigrating freedom of the press.

But what a lot of Trump’s supporters love best about him is his willingness to cast off conventional norms and be a “rule-breaker.” This has alway been the appeal of trickster gods, their enthusiastic abandonment of the societal rules that we all chafe against. Because of this, he often retains and even enhances his popularity when he says and does outrageous things. Paying off a porn star to stay quiet about an affair? No problem, because “creative horniness” is expected of a trickster. Making fun of a disabled person in public? Hey, the rules of common decency to not apply to these gods. They are supposed to be politically incorrect in the extreme.

But how about lying to an entire nation about the danger posed by a new virus, a lie that probably causes many unnecessary deaths? Well, deceit of all sorts is expected from tricksters. Wouldn’t we all like to be untethered to the truth, to remake reality in whatever form suits our selfish needs and inflated egos?

Sometimes, of course, tricksters go too far, crossing the line from mischief to evil. Perhaps the best known case of this Loki, who finally crosses that line after one of his tricks leads directly to the death of Baldur, one of Odin’s sons. The Norse gods ultimately “forge a chain from the entrails of Loki’s son Narfi and tie him down to three rocks inside a cave…[where]… a venomous serpent sits above him” dripping acidic venom onto his face and body.

Of course, Loki’s ultimate crime is to engineer and lead the destruction of the entire Norse universe. That obviously goes well beyond making mischief.

So, has Trump crossed the line from sheer mischief to actual evil? Many would say so. After all, by some accounts, Trump’s lies and incompetent inaction have led to well over 100,000 avoidable American deaths. Of course, his staunchest supporters and allies would vehemently deny such figures. For them, Trump remains an admirable trickster who continues to excel at undermining and infuriating the despised “liberals” who oppose him. For that alone, they may forgive all his sins. We can only hope those will never include an American Ragnorak.

Note: Image is from G. Yakulov. The Costume Design for the play “The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest”

The post Donald Trump and the Appeal of Trickster Gods appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

September 14, 2019

The Role of a “Fit Mythology” in the Norse Expansion

Mythologies often originate with religious and spiritual beliefs, but where do those beliefs come from?

Are they figments of fearful or mischievous imaginations? We can easily envision a prehistoric clan sitting around a fire, seriously weaving tense narratives about the angry gods that toss lightning bolts out of the hidden mysteries of looming thunder heads. Likewise, we can envision a bunch goofy hunters eating and farting Blazing-Saddles-style as they guffaw about how the foolish trickster spirit Coyote nearly killed himself running from a turkey feather.

Or are the roots of religion typically found in sublime and awesome solitude, a shiver up the back amid crystal stars in a vast desert, the complete and sudden certitude that a deity is present.

Whatever the origins of the original sparks–and I imagine there are many–there remains the question of why some spiritual beliefs grow into full-scale religions while others fade into obscurity.

Ironically, the answer to this question may boil down to the forces we call natural selection.

The Long Dispute

Why ironically? Because from the first days that the theory of natural selection was proposed by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, it was seen as threatening and antithetical to traditional religious beliefs, especially Christian ones. Today, 160 years after Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, the controversy and debate continues. It is a very extended dispute about the nature of reality.

“In fact,” Pew Research reports, “about one-in-five U.S. adults [still] reject the basic idea that life on Earth has evolved at all. And roughly half of the U.S. adult population accepts evolutionary theory, but only as an instrument of God’s will.”

Despite this ongoing antagonism, some seen the idea of natural selection–applied to cultures rather than species–as a useful tool when trying to determine how religions have developed, suggests a recent episode of the Hidden Brain podcast. Called “Where Does Religion Come From? One Researcher Points To ‘Cultural’ Evolution,” it largely focuses on the ideas of Azim Shariff, a psychology professor at the University of British Columbia.

From Smaller Nature Gods to Bigger Punisher Types

Shariff essentially argues that the agricultural revolution, which allowed human beings to congregate in much larger numbers than the typical nomadic hunter-gatherer group, demanded new religions for new ways of living. Before that revolution, human groups were typically smaller and culturally cohesive because so many people were related to one another. They are were, essentially, extended families walking around from place to place in search of food. Their gods tended to be more varied, less powerful, and less concerned about moral behaviors. Shariff states:

[I]t was only in the last 12,000 years that we started getting groups that bubbled up from beyond 100, 150 people to 1,000, 10,000 people. And what that means is that it needed something more than just our genetic inheritance [to hold the group together]. It needed a cultural idea. It needed a cultural innovation to allow us to succeed in these larger groups. And so one of the things that me and my colleagues have been arguing is that religion was one of these cultural innovations.

So, what kind of gods help large numbers of unrelated people cohere into cooperative groups? Powerful ones that are deeply interested in moral behaviors. Gods or a single God that will punish immorality, thereby keeping people on their best behaviors.

One course, podcasts are a limited format, and this one made it sound as if people evolved from animism to monotheism in one grand jump. Maybe you can make that argument for Judaism. But, in many parts of the world, agricultural peoples first developed polytheism, or the belief in multiple gods.

Where the Norse Gods Fit In

Probably the best known of the Western polytheistic traditions are the Greco-Roman and Norse myths. These gods fall somewhere in between the animist mythologies of hunter-gatherers and the monotheistic mythologies originating in the Middle East.

Their gods are neither single omnipotent rulers nor a varied hodgepodge of nature spirits. They are, in essence, complex congregations of powerful but flawed gods, led by an especially powerful and yet still limited god with many of the characteristics of mortal men: fear, depression, ambition, dauntlessness, uncertainty and more.

In the case of the Norse, the king god is Odin, of course, who is not the Alpha and Omega but, rather, a being born to specific parents, who can not control the ultimate fate of the universe, and who has had to struggle and sacrifice to achieve the limited wisdom he had.

Valhalla the Perfect Afterlife for a Warrior Invader Race

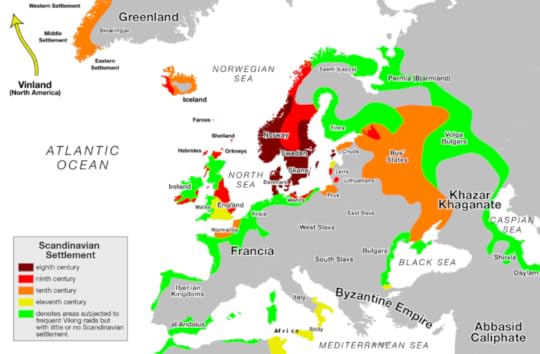

There are few practitioners of Norse religions today, though the modern variation known as Asatro does seem to have a small but passionate following. During the time of the Norse invaders that we now refer to as Vikings, the mythology was a boon to its practitioners. It helped them become among the most successful invaders and colonialists of their day, at least in and around Europe and what is now Russia.

According to Norse mythology, the way that a person enters the most desirable Viking heavens, typically known as Valhalla and Fólkvangr, is by dying in battle. Those who went to Odin’s Valhalla were a paradise for those who loved battle. Original sources have less to say about Fólkvangr, though it seems to have been another great hall and/or, based on the translation of the name, a great meadow or field. Others who didn’t die in battle were apparently mostly relegated to Helheimr, a cold and dark place.

In his blog Norse Mythology for Smart People, author Daniel McCoy reports:

The dead who reside in Valhalla, the einherjar, live a life that would have been the envy of any Viking warrior. All day long, they fight one another, doing countless valorous deeds along the way. But every evening, all their wounds are healed, and they are restored to full health. They surely work up quite an appetite from all those battles, and their dinners don’t disappoint…. They are waited on by the beautiful Valkyries.

(If you’ve read The Tollkeeper, then you know that Valkyries are pivotal to the story.)

Anyway, the implication is that by dying in battle, one either gets to go to a never-ending (till Ragnarok, that is) sporting and feasting event or gets to retire more quietly into the green fields of Fólkvangr.

Either way, it’s a great incentive for people to fight until death in a culture that, for 300 years or so, was predicated on daring, violence, conquest, adventure and the quest for personal glory. From a Darwinian point of view, these religious-based values helped the Norse spread their culture and genes–which till then were mostly isolated in the cold, dark and often inhospitable Northern climes–over much of the Western world, small parts of Africa, and “new worlds” such as Iceland, Greenland, and maybe even North America.

By Max Naylor – Public Domain

By Max Naylor – Public DomainThe Conversion to Christianity

Would this spread have occurred without their unique belief systems? I doubt it. We know that the Viking raids and conquests diminished once the Norse had accepted Christianity. But did they accept Christianity because they were done with their raiding, or vice versa? Or were other key factors, such as European ship-building technologies or the need to form alliances with their Christian conquests?

I believe these issues are so complex that there’s no way to properly answer those questions. Moreover, there have been plenty of Christian conquerors over history, which is a decent argument against my thesis.

Still, I suspect Norse mythology played a pivotal role for centuries, helping spur the raiders and traders that we now call Vikings into a lifestyle that had, from at least from an evolutionary point of view, many successes in its period of expansion.

How About Today?

If belief systems are themselves Darwinian forces, then how can we determine which myths are “selected for” in our current multimythic world?

How does one even judge? Via genetic expansions? Via wealth, health, happiness? It depends on how we classify success and competition.

But it does appear that certain mythologies have gained an upper hand over the last couple of centuries. One is capitalism, which has won out over competing mythologies (yes, I know most argue they are ideologies rather than mythologies) of communism, agrarianism or feudalism. Another is scientism, which has largely led to the spread of new technologies that allowed some cultures to dominate others over the last century or two.

These two mythologies interact with others, including religion itself. In fact, Shariff’s research suggests that some religion-based values, such as trust in those who share our worldviews, promote trade and, therefore, the economic success.

But will today’s mythologies continue to dominate human civilizations in the future? If not, what other mythologies will gain the upper hand?

Those are kinds of question that authors of speculative fiction play with all the time. But, given the length of this post, that needs to be a subject for another day.

Note: Image of Darwin and son William from Karl Pearson (1914-30) The life, letters and labours of Francis Galton, IIIa, Cambridge: University press, p. 341

The post The Role of a “Fit Mythology” in the Norse Expansion appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

September 2, 2019

The Norns, Fate and Einstein’s Loaf of Spacetime

Most of us don’t associate Norse mythology with Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, but maybe we should, especially when contemplating the idea of fate.

Norse mythology assumed that the future is fixed and we must adapt to fate, aka, wyrd or urdr, as best we can. The play a key role in this mythology, determining the fates of individuals, including the certain time and place of their deaths.

Our Modern Myths of Time, Fate and Freewill

Today, most of our common modern narratives tell a different story. Christianity tends to posit that we have free will and that God judges us based on the actions taken during our lives. Likewise, our modern society, including our penal system, assumes that we all make choices for which we should be rewarded or punished. This is, I think, especially part of the credo of cultural conservatives, as opposed to liberals, who are more likely to believe the destinies of individuals are strongly influenced by genetics, family backgrounds, socioeconomic status, and more.

How does all this jive with modern science? That depends. Science is in constant flux because it’s based on the interpretation of data stemming from millions of observations and experiments. But one of the most prominent and respected of today’s scientific mythologies is the idea of spacetime, which as was originally conceived of by Albert Einstein. (Okay, you can also make a case for Hermann Minkowski, but that’s a digression.)

Spacetime is based on the counterintuitive idea that space and time are part of a single continuum. That is, time does not exist separately from space. Our day-to-day experiences suggest that time is the same everywhere: here, on a edge of a light beam, in a black hole or on the other side of the universe.

But it’s not. Time is highly variable, passing differently depending on location, gravity, speed and other variables.

I know this intellectually, but it’s not the basis of my intuitive understanding of the the universe.

The Great Loaf of Spacetime

I was watching a Nova program called The Fabric of the Cosmos: The Illusion of Time. (I can’t embed that original video here, but you can access the link to see the whole show. There are, however, Youtube excerpts, including the version embedded in this post.)

In the accompanying clip, at around 4 minutes and 15 seconds (or about 22 minutes in the original video), host and narrator Prof. Brian Greene, author of the The Fabric of the Cosmos, elaborates on the “now slice” of the great loaf of spacetime.

Bud and the Itchy Alien

Yes, the loaf of bread conceit is a bit corny (or is it yeasty?), but I’m fascinated by the part about how the present moment (that is, the “slice of now”) compares for two individuals: one is a newspaper-reading dude (who we’ll call Bud) sitting on a bench at a gas station on Earth, and the other is a antennaed, somewhat itchy (nice detail, that) alien 10 billion light years away.

According to the show, when both of these individuals are “stationary” along a parallel slice of spacetime, their “now” moments line up. That is, Bud and the tentacled alien exist in the same moments of time. (I don’t know exactly how this is supposed to work, given the constant movement of the cosmos, but let’s call it a thought experiment dumbed down for a popular audience).

But then, Greene posits, the itchy alien gets on a bicycle and starts rolling away from Bud at typical bike speed. What happens? Greene narrates:

Since motion slows the passage of time, their clocks will no longer tick off time at the same rate. And if their clocks no longer agree, their now slices will no longer agree either. The alien’s now slice cuts across the loaf differently. It’s angled towards the past. Since the alien is biking at a leisurely pace, his slice is angled to the past by only a minuscule amount. But across such a vast distance, that tiny angle results in a huge difference in time. So what the alien would find on his angled now slice—he considers as happening right now, on Earth—no longer includes our friend at the gas station, or even 40 years earlier when our friend was a baby. Amazingly, the alien’s now slice has swept back through more than 200 years of Earth history and now includes events we consider part of the distant past, like Beethoven finishing his 5th Symphony: 1804 to 1808.

Bicyling into the Future

Okay, so that’s weird, right? Time travel by velocipede.

But, according to Greene, it can get weirder yet.

Watch what happens when the alien turns around and bikes toward Earth. The alien’s new “now slice” is angled toward the future, and so it includes events that won’t happen on Earth for 200 years: perhaps our friend’s great-great-great granddaughter teleporting from Paris to New York.

Wait, what?

Thanks to scifi stories and high school science class, most of us are at least vaguely familiar with the idea that time runs at different speeds for folks hanging on a planet and folks traveling at, say, something close to light speed in a rocket ship. The idea is that the faster you go, the slower your speed relative to folks who are moving, well, not so fast. So, if you zoom around at 99.5% of the speed of light for five years and then come back to Earth, 60 years would have passed on Earth. Thus, time travel into the future, assuming you can figure out how to sufficiently speed yourself up, is perfectly allowable in Einstein’s universe.

But the idea that the you could bicycle from hundreds of years in the past to hundreds of years into the future (relative to some other far-flung guy named Bud) is, well, surprising to me.

I realize that the alien, unless he can figure out instantaneous transport across billions of light years, can’t actually travel into Earth’s past or future, but here’s what gets me: this thought experiment suggests that the future is fixed. Spacetime is already mapped out, not just for today and yesterday but for tomorrow as well. Because the future is just a matter of your location in the (apparently) already baked loaf of spacetime.

Maybe I’ve misinterpreted. Feel free to watch the video yourself and see if you can draw some other conclusion. And maybe Greene’s interpretation of spacetime is itself flawed. Or maybe there are, via quantum uncertainties or the hypothetical multiverse, lots of different alternatives.

But, assuming I understand this correctly, our futures–and therefore our fates–are fixed. Which brings me back, after a lengthy, freewheeling detour, to Norse mythology.

Wyrd, Urdr and Our Present Age

As I’ve noted in a separate post, the word word wyrd is typically viewed as a word for fate in Norse mythology. It’s also one of the names of the most widely cited of the three Great Norns, the woman I think of as the eldest norn.

But there are experts such as professor Jackson Crawford who take issue with using the word wyrd for fate. He notes that, although it’s a word used in Beowulf, it’s actually just an Old English translation of Urd or Urdr, which he prefers to use both as the word for fate and the name of the eldest norn. In The Tollkeeper, of course, she is the character known as Urd.

So, how did the Norse tend to view urdr or fate? In a succinct but typical usage, stanza 30 of the Poetic Edda poem called “Hamthismal,” one of main characters says, “We earned honor here, though we are fated to die today – a man will not live one day longer than the Norns have decided.”

While believing that their future was fated, the Norse also tended to believe that reputation and honor hinged on how a person met their fate. Daniel McCoy, author of The Viking Spirit, writes, “[T]he Vikings believed that one’s fate was hardly more important than what one did with one’s fate – that is, the attitude with which one met whatever fate had in store. There was no honor in merely passively surrendering to fate. Instead, honor was to be found in approaching one’s fate as a battle to fight heroically – even if it was a battle one was ultimately doomed to lose.”

Our Choices in a Multimythic Society

In past ages, myths and religions tended to hold societies together. In the more multicultural societies of today, myths mesh and merge, bump up and even clash with one another. I don’t know if there’s a word for this, but let’s call it the multimythic society.

I live in the U.S., where we are definitely multimythic when it comes to our understandings of time and destiny. To the degree you believe in one of those realities (that is, the notion of free will), you can decide for yourself which mythology you want to adopt. Even if you believe that your future is somehow already engraved in the intricate whirls of galaxies and darkness, you can adopt the Viking attitude of dauntlessness and defiance. There are likely worse fates amid the great existential uncertainties of a multimythic cosmos.

Nebula IRAS 05437+2502. Links Sahai, R., Claussen, M., Morris, M., & Ainsworth, R. 2009, Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 41, 456 Rosen.

Nebula IRAS 05437+2502. Links Sahai, R., Claussen, M., Morris, M., & Ainsworth, R. 2009, Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 41, 456 Rosen.Images: From Hubble Space Telescope: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/multimedia/index.html

The post The Norns, Fate and Einstein’s Loaf of Spacetime appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

The Norns, Fate and Einstein’s Spacetime

Most of us don’t associate Norse mythology with Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, but maybe we should, especially when contemplating the idea of fate.

Norse mythology assumed that the future is fixed and we must adapt to fate, aka, wyrd or urdr, as best we can. The play a key role in this mythology, determining together the fates of individuals, including the certain time and place of their deaths.

Our Modern Myths of Time, Fate and Freewill

Today, most of our common modern narratives tell a different story. Christianity tends to posit that we have free will and that God judges us based on the actions taken during our lives. Likewise, our modern society, including our penal system, assumes that we all make choices for which we should be rewarded or punished. This is, I think, especially part of the credo of cultural conservatives, as opposed to liberals, who are more likely to believe the destinies of individuals are strongly influenced by genetics, family backgrounds, socioeconomic status, and more.

How does all this jive with modern science? That depends. Science is in constant flux because it’s based on the interpretation of data stemming from millions of observations and experiments. But one of the most prominent and respected of today’s scientific mythologies is the idea of spacetime, which as was originally conceived of by Albert Einstein.

Spacetime is based on the counterintuitive idea that space and time are part of a single continuum. That is, time does not exist separately from space. Our day-to-day experiences suggest that time is the same everywhere: here, on a edge of a light beam, in a black hole or on the other side of the universe.

But it’s not. Time is highly variable, passing differently depending on location, gravity, speed and other variables.

I know this intellectually, but it’s not the basis of my intuitive understanding of the the universe.

The Great Loaf of Spacetime

I was watching a Nova program called The Fabric of the Cosmos: The Illusion of Time. (I can’t embed that original video here, but you can access the link to see the whole show. There are, however, Youtube excerpts, including the version embedded in this post.)

In the accompanying clip, at around 4 minutes and 15 seconds (or about 22 minutes in the original video), host and narrator Prof. Brian Greene, author of the The Fabric of the Cosmos, elaborates on the “now slice” of the great loaf of spacetime.

Bud and the Itchy Alien

Yes, the loaf of bread conceit is a bit corny (or is it yeasty?), but I’m fascinated by the part about how the present moment (that is, the “slice of now”) compares for two individuals: one is a newspaper reading guy (who we’ll call Bud) sitting on a bench at a gas station on Earth, and the other is a antennaed, somewhat itchy (nice detail, that) alien 10 billion light years away.

According to the show, when both of these individuals are “stationary” along a parallel slice of spacetime, their “now” moments line up. That is, Bud and the tentacled alien exist in the same moments of time. (I don’t know exactly how this is supposed to work, given the constant movement of the cosmos, but let’s call it a thought experiment dumbed down for a popular audience).

But then, Greene posits, the itchy alien gets on a bicycle and starts rolling away from Bud at typical bike speed. What happens? Greene narrates:

Since motion slows the passage of time, their clocks will no longer tick off time at the same rate. And if their clocks no longer agree, their now slices will no longer agree either. The alien’s now slice cuts across the loaf differently. It’s angled towards the past. Since the alien is biking at a leisurely pace, his slice is angled to the past by only a minuscule amount. But across such a vast distance, that tiny angle results in a huge difference in time. So what the alien would find on his angled now slice—he considers as happening right now, on Earth—no longer includes our friend at the gas station, or even 40 years earlier when our friend was a baby. Amazingly, the alien’s now slice has swept back through more than 200 years of Earth history and now includes events we consider part of the distant past, like Beethoven finishing his 5th Symphony: 1804 to 1808.

Bicyling into the Future

Okay, so that’s weird, right? Time travel by velocipede.

But, according to Greene, it can get weirder yet.

Watch what happens when the alien turns around and bikes toward Earth. The alien’s new “now slice” is angled toward the future, and so it includes events that won’t happen on Earth for 200 years: perhaps our friend’s great-great-great granddaughter teleporting from Paris to New York.

Wait, what?

Thanks to scifi stories and high school science class, most of us are at least vaguely familiar with the idea that time runs at different speeds for folks hanging on a planet and folks traveling at, say, something close to light speed in a rocket ship. The idea is that the faster you go, the slower your speed relative to folks who are moving, well, not so fast. So, if you zoom around at 99.5% of the speed of light for five years and then come back to Earth, sixty years would have passed on Earth. Thus, time travel into the future, assuming you can figure out how to sufficiently speed yourself up, is perfectly allowable in Einstein’s universe.

But the idea that the you could bicycle from hundreds of years in the past to hundreds of years into the future (relative to some other far-flung guy named Bud) is, well, surprising to me.

I realize that the alien, unless he can figure out instantaneous transport across billions of light years, can’t actually travel into Earth’s past or future, but here’s what gets me: this thought experiment suggests to me that the future is fixed. Spacetime is already mapped out, not just for today and yesterday but for tomorrow as well. Because the future is just a matter of your location in the (apparently) already baked loaf of spacetime.

Maybe I’ve misinterpreted. Feel free to watch the video yourself and see if you can draw some other conclusion. And maybe Greene’s interpretation of spacetime is itself flawed. Or maybe there are, via quantum uncertainties or the hypothetical multiverse, lots of different alternatives.

But, assuming I understand this correctly, our futures–and therefore our fates–are fixed. Which brings me back, after a lengthy, freewheeling detour, to Norse mythology.

Wyrd, Urdr and Our Present Age

As I’ve noted in a separate post, the word word wyrd is typically viewed as a word for fate in Norse mythology. It’s also one of the names of the most widely cited of the three Great Norns, the being I think of as the eldest norn.

But there are experts such as professor Jackson Crawford who take issue with using the word wyrd for fate. He notes that, although it’s a word used in Beowulf, it’s actually just an Old English translation of Urd or Urdr, which he prefers to use both as the word for fate and the name of the eldest norn. In The Tollkeeper, of course, she is the character known as Urd.

So, how did the Norse tend to view urdr or fate? In one succinct but typical usage, stanza 30 of the Poetic Edda poem called “Hamthismal,” one of main characters says, “We earned honor here, though we are fated to die today – a man will not live one day longer than the Norns have decided.”

While believing that their future was fated, the Norse also tended to believe that reputation and honor hinged on how a person met their fate. Daniel McCoy, author of The Viking Spirit, writes, “[T] he Vikings believed that one’s fate was hardly more important than what one did with one’s fate – that is, the attitude with which one met whatever fate had in store. There was no honor in merely passively surrendering to fate. Instead, honor was to be found in approaching one’s fate as a battle to fight heroically – even if it was a battle one was ultimately doomed to lose.”

Our Choices in a Multimythic Society

In past ages, myths and religions tended to hold societies together. In the more multicultural societies of today, myths mesh and merge, bump up and even clash with one another. I don’t know if there’s a word for this, but let’s call it the multimythic society.

I live in the U.S., where we are definitely multimythic when it comes to our understandings of time and destiny. To the degree you believe in one of those realities (that is, the notion of free will), you can decide for yourself which mythology you want to adopt. Even if you believe that your future is somehow already engraved in the intricate whirls of galaxies and darkness, you can adopt the Viking attitude of dauntlessness and defiance. There are likely worse fates amid the great existential uncertainties of a multimythic cosmos.

Nebula IRAS 05437+2502. Links Sahai, R., Claussen, M., Morris, M., & Ainsworth, R. 2009, Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 41, 456 Rosen.

Nebula IRAS 05437+2502. Links Sahai, R., Claussen, M., Morris, M., & Ainsworth, R. 2009, Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 41, 456 Rosen.Images: From Hubble Space Telescope: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/multimedia/index.html

The post The Norns, Fate and Einstein’s Spacetime appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

August 18, 2019

Block Puzzles, Animism and the Rise of Digital Household “Gods”

When I relax, I sometimes like to listen to short stories while playing games on my phone. Nothing unusual there, of course. Cell phones have become multi-purpose entertainment systems for millions, perhaps billions, of people.

But the type of games I play, which can generically be referred to as “block puzzles,” makes me think of animistic mythologies. I know that sounds a bit nuts, so let me explain.

Animism in the 21st Century

Animism is the religious belief that objects, places and creatures possess distinct spiritual essences (and, therefore, preferences).

Religious writing depicts these spiritual essences as inherent in natural objects, plants and animals, but it’s sometimes associated with human-made artifacts, including even language itself.

I think many of us share stereotypes about animism, especially the idea that it is one of the most “primitive” of spiritual traditions. But not only is traditional animism still seen in ultramodern nations like Japan, but some thinkers such as the physicist Nick Herbert have argued that “mind” permeates everything in the universe. This is why the term “quantum animism” has been coined.

Digitism the New Animism?

But even if one is skeptical of quantum as well as traditional animism, it’s hard to argue against the notion that a lot of our artifacts are getting smarter. We can, for example, speak directly to some our digital devices, which can understand us well enough to give us reasonable and even helpful responses to a huge range of questions. What is the weather forecast for tomorrow, how tall is Lebron James, when was Shakespeare born?

What has gotten me thinking about animism and what I’ll call “digitism” is game play. I don’t play a lot of games on my smartphone, but I do find block puzzle games engaging and relaxing.

There are lots of versions of these games, but they’re all based on the same goal: to fit together virtual blocks in a grid so that they span horizontally, vertically and (in some versions) diagonally from one side of the grid to the other.

That sounds simple enough, but the games tend to get harder the longer you play. Sometimes the game will throw in progressively more complex shapes, which are hard to fit together. And, if the game genuinely “wants” you to lose, it can always give you one huge block after another in such a way that death and disaster is inevitable.

The longer one plays, the more the invisible game algorithm feels like a “little god” that determines, at least within the confines of these tiny universes, your fate. If you want to live long there, then you need to figure out what pleases and displeases the digital spirits within. And they are not all the same. Some are relatively benign, even merciful, but most are demanding, some even verging on sadistic.

There’s one thing common to all these games: the digital spirits “want” you to move in specific ways that are not always obvious. Indeed, in the best of these games, every single move is a separate puzzle that you must solve in order to “extend your play,” aka, live.

Digital Sacrifices

There’s nothing new in any of this. Most computer games work along similar principles, wherein in the game itself is an animate (and animating) spirit that determines your digital fate. But, for some reason, this feeling is especially acute in the realm of block puzzles for me.

The little digital spirits even demand their own version of sacrifices, as gods of all mythologies are apt to do. In this case, the sacrifices tend to mean spending 30 seconds allowing some advertisement to run, after which the game may grant a favor (perhaps, for example, some blocks suddenly disappear, allowing you avoid certain digital death). In essence, you are literally offering up a very small chunk of your time (that is, your actual life) so that the algorithm will safeguard you.

This is a kind of parody of a genuine religious experience, and I don’t mean to say that game algorithms are literal gods. But I do think we increasingly need a way of describing this eerie and, even in my eyes, slightly blasphemous feeling of wanting to understand and appease these digital beings.

Brave New Mythologies

This dynamic does not only apply to play, of course. As more and more of our tools and arts are digitized, we increasingly need to know what our machines want from us. For example, why won’t my printer work? Is it angry at my laptop? Did I not feed it paper correctly? Must I give up some portion of my life to finding a print driver on the Internet and downloading it onto my computer? Will that appease it, or only make it more angry still, perhaps freezing or rebooting my entire system?

In coming years, such digital spirits will inhabit more and more of our gadgets via the Internet of Things phenomenon. They will also increasingly crawl up over our eyes and maybe someday even into our brains, if the likes of Elon Musk have their way.

Spooky stuff. What kinds of sacrifices will they demand then? What kinds of new powers will they wield? Will digitism become the new animism? And, if so, what new mythologies will come to dominate our lives?

These questions are both old and new. We live in a Promethean Age, and I doubt anyone can tell us how humanity’s tale will ultimately end.

The post Block Puzzles, Animism and the Rise of Digital Household “Gods” appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

June 30, 2019

Unleashed Earth and Constrained Fire in The Golem and the Jinni

The Golem and the Jinni, a novel by Helene Wecker, is a tale that’s finely woven using an array of opposing thematic threads: earth and fire, self and selflessness, free will and enslavement, art and altruism.

Two Folklore Traditions

Wecker ingeniously weaves together two separate folklore traditions from two cultures that have similar roots but that are, in the modern world, often seen as in conflict with one another. A golem is, of course, a creature of Jewish folklore, a being that’s magically created out of clay or mud. It’s generally seen as a perfectly obedient vehicle used for vengeance or war.

A jinni is, on the other hand, a supernatural being originating in early pre-Islamic Arabian and later Islamic mythology and/or theology. In the Islamic tradition, the jinn (plural of jinni) are made up of “smokeless fire,” and that’s the tradition from which Wecker draws.

This sets up the tension and interplay between earth and fire, which are two of the four (along with air and water) elements of classical Greek thought. (Other cultures had similar ideas about the elements.) In the novel, these elements are also linked to the gender roles historically associated with them: female for earth and male for fire. These are personified in the form of the two main characters: Chava and Ahmad.

I enjoyed the book and would highly recommend it, but I’m not going to review it per se. Instead, I’ll discuss how these two traditions continue to inform our modern lives.

Earth and Fire

Gender is among the most controversial topics in today’s culture wars. Many women continue to struggle against what they view as male dominance and oppression. These are manifested many ways, some of which are:

* lower wages

* less political power

* legal infringements on what they do with their bodies

* less corporate power

* violence and harassment

* workplace discrimination

The golem in Wecker’s novel, Chava, is literally designed to be the ultimate obedient, unquestioning, and subservient woman. The fact that she winds up as an independent woman who must make her own decisions is a twist of fate brought about by the sudden death of her master/husband.

Her subsequent “independence” is not hard won, as it has been among many women in the 20th and 21st centuries, but she must nonetheless learn how to survive on her own.

The jinni, Ahmad, is in many ways her polar opposite. He is a protean creature who wants nothing more than to be free to soar through the desert winds, going wherever his whim may take him and adopting whatever form suits him.

Yet, it is he who finds himself wearing a shackle that keeps him from taking the form of anything other than a human being. He wishes to be a utterly free and powerful being but is shackled by fate. (Actually, there’s someone who enslaves him, but we’ll leave the villain aside here.)

Women and Men

Both characters are strangers in a strange land, and so find themselves drawn together. Yet, they are also alien to one another and often at odds. She ultimately adjusts, even if imperfectly, to her independence whereas he must resign himself to a new world where his powers and prerogatives are constrained.

The novel is nothing like a straight allegory, but it’s hard to miss the metaphorical undertones. In the process of freeing themselves from confines of the traditional “man’s world,” women often find themselves needing to reinvent who they are, and this can sometimes be an uncomfortable and maddening challenge.

Meanwhile, many men feel as if they’ve lost something precious. Their utter mastery of the world is challenged and their sometimes dangerous self-indulgences (which Ahmad displays throughout the novel) are called into question.

My View of the Mythological Lessons Learned

What is the book’s mythological resolution to all this? I’d say that Ahmad learns humility and compassion, two qualities in short supply through much of his narrative.

Meanwhile, what does Chava learn? Courage, for one thing, but also a willingness to endure complexity. It’s sorely tempting to give oneself over to some authority who will make decisions for you. That’s part of why, I believe, we live in an age of growing authoritarianism. It isn’t just that nations are using technology to spy and control as never before. It’s that people are increasingly willing, even eager, to give up their autonomy in return for feeling protected from the complexities of modern existence.

These are, of course, old lessons. Myths have been teaching humanity the dangers of hubris since the beginning. At the same time, they’ve been teaching about steadfastness of principles in the face of authorities. Consider, for example, the myth of Prometheus.

The narrative threads may be old, but the lessons are never easy. There are fine lines between steadfastness and hubris, and between self-sacrifice and the cowardly surrender of personal responsibility. Myth, including the subtle use of older myths to teller newer stories, are increasingly used to help us locate those lines, which can be as fine and elusive as ancient engravings carved into desert stone.

Image: Attributable to 'Abd al-'Aziz[1] - The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The post Unleashed Earth and Constrained Fire in The Golem and the Jinni appeared first on The Tollkeeper.