Mark R. Vickers's Blog, page 6

October 27, 2018

Dammit, Shakespeare, Look What You’ve Done to the Wyrd Sisters!

I had to do a facepalm today when I read an article called “Why The Weird Sisters In Chilling Adventures Of Sabrina Seem So Familiar.” I was just minding my own business while Googling “norse myths” in the news. Yes, I admit that’s an eccentric habit I got into while writing The Tollkeeper. But I didn’t expect to come across such calumny against the Norns in an entertainment website targeting women. Here’s a portion of the article:

The Weird Sisters of Chilling Adventures of Sabrina stem from a long line of other witches in literature and pop culture who group themselves in threes, dating all the way back to ancient mythology. Both Greek and Norse mythology feature a trio of witches who determine the course of a person’s life using a cosmically important thread: One witch unspools the thread, one measures, and one snips. The Fates, as these witches are called in Greek mythology, appear in the Underworld in Hercules. In Norse myths, these arbiters of destiny are the Norns. [emphasis in red is mine]

Come on! It’s true that the notion of three powerful female characters goes back a long way, as do the stories of the Norns and Fates. But they were not witches until wily Willy Shakespeare made them so in his play Macbeth, probably to avoid any hassles from the religious authorities of his time. After all, the Fates were originally part of ancient religions that only became myths once they were (more or less) defunct with the spread of Christianity in Europe.

So, Shakespeare turned them into “witches” rather than gods or, in the case of Norse myth, giantesses. The original “wyrd sisters” (wyrd means fate) were nothing like Shakespeare’s creepy old biddies. Bullfinch’s Mythology states:

The Northern goddesses of fate, who were called Norns, were in nowise subject to the other gods, who could neither question nor influence their decrees. They were three sisters, probably descendants of the giant Norvi, from whom sprang Nott (night). As soon as the Golden Age was ended, and sin began to steal even into the heavenly homes of Asgard, the Norns made their appearance under the great ash Yggdrasil, and took up their abode near the Urdar fountain. According to some mythologists, their purpose in coming thus was to warn the gods of future evil, to bid them make good use of the present, and to teach them wholesome lessons from the past.

It’s hard to blame a lot of present-day writers for getting this wrong. After all, they’re just taking their cues from the greatest writer in English of all time. And I’m not going to sweat the fact that some script writers turn the Weird Sisters into a trio of mean girls in a show about teenage witches.

But, if we’re going to write about their historical roots, let’s not refer to all those mythological characters as witches. They are more than that — much more — and they deserve better.

Image from https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2018...

The post Dammit, Shakespeare, Look What You’ve Done to the Wyrd Sisters! appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

October 23, 2018

The Essential Spookiness of Hearing the Hávamál Spoken in Old Norse

So, what did ancient Norse sound like? Dr. Jackson Crawford gives you a taste, even if it is with a midwestern accent. For me, it’s spooky to hear the Hávamál read out loud in the Old Norse. The Hávamál is presented as a single poem in the Codex Regius, which is a collection of Old Norse poems. The collection gives voice to Odin, the king of the Norse gods. It is partially “gnomic” in that it offers advice for proper conduct. See if it raises any hairs on the back of your neck.

Odin’s tale plays a major thematic role in The Tollkeeper.

The post The Essential Spookiness of Hearing the Hávamál Spoken in Old Norse appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

October 17, 2018

Wolves in Our Modern Poetry and Environmental Art

I wrote a number of blog posts about the role that wolves have played in folklore, myths and language–a role that they continue to play in our modern age. What I didn’t write about was what the role they play in poetry. There, though with some twists, they still tend to be villains, as in Roald Dahl’s “Little Red Riding Hood And The Wolf.” Or they represent sudden death, as in Barry Middleton’s “Wolf.” Or they are something else, something harder to summarize, as in Martha Collins’ “The Good Gray Wolf,” where the wolf is more akin to desire.

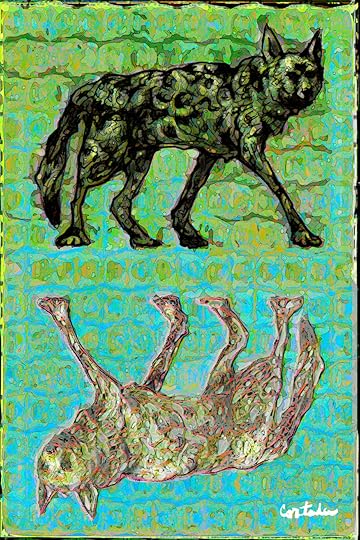

I took my own whack at a wolf poem that, like “On Cortada’s Key Deer,” is an ekphrastic poem based on a work of Xavier Cortada. This particular work of his is called Red Wolves.

Aside from the fact that I once studied in London and lived in a Florida bungalow, this is not an autobiographical poem. The narrator is, in fact, something of a creepy voyeur, but he gave me a chance to meditate on something in Cortada’s piece, where there are two opposed wolves: one on top and the other on bottom.

Cortada’s Red Wolves

You assume–being so knowledgeable with your one art history class

taken decades ago while studying in London (yes, London!), where there were real, honest-to-god Monet water lilies in the what’dya’call it Tate–

that the two red wolves are symbolic (or something).

Maybe that’s why only one is kind of tawny,

the other being black as death or shadows

or the long lustrous hair of your neighbor’s new girlfriend,

who has got to be 20 years younger than than him,

the shyster shit in his big ugly Spanish Colonial that dwarfs

your tiny, termite-eaten bungalow.

Those Monets were something, alright, big-ass canvases

like the massive flat screens the neighbor has all over his place

–living room, dining room and master bedroom–

where he probably watches porn while she works

the nightshift at The Palms, coming back in the dawn

reeking of sweat and hand sanitizer and what-not hospital smells,

stripping out of that sky blue uniform

as the lech watches from the king-sized water bed.

Is the red wolf the black one’s reflection or something?

Could be with the blue-green below like maybe murky waters

or turquoise springs or the huge screened-in pool of the neighbor

where you watched the bikinied girlfriend laughing while slipping

like a kid on those smooth, cool ceramic tiles.

Anyway, the black wolf beast slouches, the cocky bastard,

looking right at you as it goes by going somewhere.

Bethlehem, maybe? Galilee? Except now that you think about it

the black one and the red are slouching in different directions

so the walking-near-water (in water, on water?) reflection thing

doesn’t quite make sense after all

but at least you’re here, right, appreciating art?

Meanwhile your shallow neighbor is probably lounging

by that pool staring smugly at his mug reflected darkly

as the dusk creeps into that goddamned mausoleum of a house,

thinking how he’ll be in danger of dying when she’s still young,

of how bleak and black the world can look

even from top of the goddamned food chain.

Cover image from https://www.flickr.com/photos/kachnch... via Wikipedia

The post Wolves in Our Modern Poetry and Environmental Art appeared first on The Tollkeeper.