Mark R. Vickers's Blog, page 5

December 24, 2018

#MythicFictionMonday Begins: A New Year’s Resolution

I’ve decided to start a little tradition that may or may not last. I’m calling it #MythicFictionMonday. Every Monday, I’m going to write a short post on a piece of mythic fiction.

So, what’s mythic fiction, you ask? Yeah, I hadn’t heard of it either until I stumbled over the term on Goodreads. It turns out The Tollkeeper is a pretty classic example of the genre, so at least I know how where in the literary landscape to locate it.

Wikipedia provides the following definition of mythic fiction:

Mythic fiction is literature that is rooted in, inspired by, or that in some way draws from the tropes, themes and symbolism of myth, legend, folklore, and fairy tales. The term is widely credited to Charles de Lint and Terri Windling. Mythic fiction overlaps with urban fantasy and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, but mythic fiction also includes contemporary works in non-urban settings. Mythic fiction refers to works of contemporary literature that often cross the divide between literary and fantasy fiction.

I’m currently reading a mythic fiction novel, which I’ll post about next Monday. I doubt I can read a piece of mythic fiction (can we call it mythfic for short?) every week, but I can probably scrounge up some info about a mythfic novel once a week.

If this sounds fun, feel free to tweet about a mythic fiction work on Mondays. Maybe it’s your own work. Maybe some else’s. But it’d be neat if we could form a community of sorts, sharing discoveries and raising the profile of this genre.

The post #MythicFictionMonday Begins: A New Year’s Resolution appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

#MythicFictionMonday Begins

I’ve decided to start a little tradition that may or may not last. I’m calling it #MythicFictionMonday. Every Monday, I’m going to write a short post on a piece of mythic fiction.

So, what’s mythic fiction, you ask? Yeah, I hadn’t heard of it either until I stumbled over the term on Goodreads. It turns out The Tollkeeper is a pretty classic example of the genre, so at least I know how where in the literary landscape to locate it.

Wikipedia provides the following definition of mythic fiction:

Mythic fiction is literature that is rooted in, inspired by, or that in some way draws from the tropes, themes and symbolism of myth, legend, folklore, and fairy tales. The term is widely credited to Charles de Lint and Terri Windling. Mythic fiction overlaps with urban fantasy and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, but mythic fiction also includes contemporary works in non-urban settings. Mythic fiction refers to works of contemporary literature that often cross the divide between literary and fantasy fiction.

I’m currently reading a mythic fiction novel, which I’ll post about next Monday. I doubt I can read a piece of mythic fiction (can we call it mythfic for short?) every week, but I can probably scrounge up some info about a mythfic novel once a week.

If this sounds fun, feel free to tweet about a mythic fiction work on Mondays. Maybe it’s your own work. Maybe some else’s. But it’d be neat if we could form a community of sorts, sharing discoveries and raising the profile of this genre.

The post #MythicFictionMonday Begins appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

December 18, 2018

Modern Superheroes and Ancient Mythologies: Part 1

The headline reads, “Heroes: Stephen Fry reveals how modern superhero stories have plundered ancient mythology.”

When I first read it, part of me was thrilled. I’m a sucker for this stuff, and I plan to grab a copy of the book out of the library in coming weeks.

But another part of me was cynical, responding with the adolescent, “Yeah, no shit, Sherlock.”

Since the Norse god Thor is part of the most popular team of superheroes in cinematic history, how could this be anything but dead obvious?

There are, for example, plenty of direct references to Norse, Greek and other myths in the world of comic books. Below are some examples:

Norse Myth

Aside from Thor in the Marvel Universe, there are various other examples of comic book heroes directly linked to Norse myths:

-> Valhalla comics: A Danish series published by Carlsen Comics and drawn by Peter Madsen. These are based on the stories and legends in the Elder Eddas.

-> Ragnarok: These are manhwa (like the better known manga) created by Lee Myung-jin and published by Daiwon C.I. in South Korea. The series mostly draws from Norse mythology.

-> Ink Pen: A syndicated comic strip that included, among other, the Norse gods Tyr and Hela.

-> Beowulf (DC Comics): A short-lived series that featured the hero of the famous epic poem Beowulf.

-> A whole slew of Marvel comics: These are often linked to the Thor, but they incorporate a wide range of other Norse gods and heroes.

-> A range of non-Marvel comics: Sure, the Norse god types tend agglomerate in Marvel, but there are various others. Take Ymir, for example. The frost giant (and first living creature in the universe) isn’t exactly a well known character in U.S. popular culture, yet there he is in variety comics, such as Zölasträya and the Bard, Master of the Void, DC, Grimm Fairy Tales: Myths & Legends, and Valhalla.

Greek and Roman Myth

-> Wonder Woman (DC): She is the best known of the Greek-myth based superheroes, and plenty of other Greek gods are woven into her books. She was created by the gods and has many of their virtues: “Beautiful as Aphrodite, wise as Athena, swifter than Hermes, and stronger than Hercules.”

-> Hercules (multiple): Hercules was originally a character out of Greek legend, where he was known as Heracles. Then he was incorporated into the Roman pantheon, where he went by the name most people are familiar with today. He has appeared in a range of comic books produced by different publishers, such as Charlton, Marvel, DC, Image and more.

-> Olympian gods (both Marvel and DC): This represents a hodgepodge of gods and heroes, most of them with Greco-Roman origins. Marvel has a group known as Olympians, while DC has assorted Greek and Roman gods incorporated into a variety of story lines, often in Wonder Woman narratives but finding their into other books such as Batwoman as well.

There are assorted superhero characters from other myths as well, especially Egyptian mythology.

So, it’s not exactly a revelation that superhero stories have plundered mythology. In fact, those mythologies probably live on in comic books and graphic novels more than in any part of today’s popular culture. (Though there are plenty of examples in video games, television, cinema and fiction. In fact, The Tollkeeper is in a long line of novels often referred to as mythic fiction).

The direct references in comic books are, of course, just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. If we look at the “inspired by” references, the list grows much longer. We’ll cover that topic in Part II of this three-part series.

Image from By Mårten Eskil Winge - at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

The post Modern Superheroes and Ancient Mythologies: Part 1 appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

December 8, 2018

On Ancient Myths, Modern Robots and High-tech Imaginings

When I was a kid, I loved watching the reruns of the 1963 movie Jason and the Argonauts. My friends and I lived for the scenes in which the human characters battle the various monsters created through the magic of stop-motion animation. There’s still nothing like them. Somehow modern CGI-animated scenes just don’t have that same cinematic magic when it comes to sword-fighting with scowling skeletons.

One of scenes I liked best (aside from the sword-fighting skeletons) is where Jason exsanguinates Talos, the giantic bronze statue that eerily comes to life. Stop-motion is especially convincing when it comes to animating things that are supposed to be artificial to begin with. According to Greek myth, Hephaestus, the Greek god of blacksmiths and artisans, built Talos at the request of Zeus.

In the original myth, Talos was supposed to protect Europa, whom Zeus kidnapped and brought to the island of Crete. (I’m not sure if he was supposed to protect her from other wannabe kidnappers or from rescuers, but maybe we’ll take that up in a future blog on Europa, after whom the continent of Europe was named).

From Swords and Sandals, “The Creatures of Jason and the Argonauts”

Anyway, I don’t remember Europa being in the movie. I think they just stumbled onto the island because, well, they needed to fight a gigantic bronze monster.

In the movie, Jason kills Talos by unscrewing a round port in the giant’s heel to let the molten lava-like ichor (that is, the blood of the gods) drain out. Thinking back, that round port bears a strong resemblance to the compartments where we store batteries in lots of our modern devices.

Of course, that’s the made-for-TV version. In mythology, it’s often Medea, Jason’s wife, who kills Talos by removing a nail in his heel. That also led to to deadly ichorlessness.

The bottom line, though, is that Talos is essentially a robot built to be a security system for a whole island. When I was a kid, I understood his essential innocence and felt kind of bad for poor Talos, who was just doing his pre-programmed job. (He dies pretty gruesomely, if I recall correctly, grabbing at his giant throat as if he’s strangling to death.)

But what I didn’t appreciate as a kid was that Talos was just one of many “robots” to appear in mythology. There’s now a whole book devoted to the subject: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology, by Adrienne Mayor.

Writing in the Weekly Standard, William Wilson notes:

Greek myths as [Mayor] tells them are overflowing with robots. Robot sentinels like Talos, ferocious killer robots like the Stymphalian birds, sinister androids like Pandora, robotic assistants like Hephaestus’ forge helpers, and on and on. What makes such things robots? Mayor offers two criteria: first, that they are of mechanical rather than biological construction, and second, that they are the products of conscious artifice. The Greeks, she argues, envisioned and described these beings as advanced technological artifacts driven by internal machinery and following rational principles of operation.

As I suggested in an earlier blog on the topic of Mimir (who is a character in the The Tollkeeper), ancient myths often anticipate current and future technologies because they give expression to our visions of what’s possible and desirable. Flying humans? Check out Daedalus. Instant messaging? Check out Mercury.

The robots of mythology are just another case in point. If we want to better understand the promise and perils of artificial intelligence and robots, we should start there and then work ourselves up to the present moment. It is, after all, just one long, mythic narrative. Yesterday’s blacksmith Greek god is today’s Silicon-valley billionaire uber nerd. When you look at it from that perspective, it doesn’t seem like such a big leap.

Feature image: Medeia and Talus by Sybil Tawse

The post On Ancient Myths, Modern Robots and High-tech Imaginings appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

December 6, 2018

The Máni on the Moon Chased by a Walloping Warg

The Moon is a woman in most European-based mythologies. In fact, below is a list of 16 such goddesses, though some are different versions of very similar goddesses, such as Diana and Artemis.

Goddess Diana (Roman mythology)

Goddess Achelois (Greek mythology)

Goddess Arianrhod (Welsh mythology)

Goddess Artemis (Greek mythology)

Goddess Artume (Etruscan mythology)

Goddess Ataegina (Lusitanian mythology)

Goddess Bendis (Thracian mythology)

Goddess Hecate (Greek mythology)

Goddess Ilargi (Basque mythology)

Goddess Kuu (Finnish mythology)

Goddess Losna (Etruscan mythology)

Goddess Luna (Roman mythology)

Goddess Mano (Sami mythology)

Goddess Phoebe (Greek mythology)

Goddess Selene (Greek mythology)

Goddess Trivia (Roman mythology)

This does not count Christianity’s Virgin Mary, who is not a goddess but who is often associated with the Moon in European arts and literature. In contrast, there are only four male versions of the moon in European mythology:

God Tylze (Mari mythology)

God Elatha (Irish mythology)

God Hors (Slavic mythology)

God Máni (Norse mythology)

Máni on the Moon

Because of the research I conducted while writing The Tollkeeper, I focused on the Norse version of the moon deity, Máni. He is, however, less of a deity than mythical figure. Here’s how the Prose Edda describes the origins of the Máni.

Mundilfare hight the man who had two children. They were so fair and beautiful that he called his son Moon [that is Máni] , and his daughter, whom he gave in marriage to a man by name Glener, he called Sun [that is, Sól]. But the gods became wroth at this arrogance, took both the brother and the sister, set them up in heaven, and made Sun drive the horses that draw the car of the sun, which the gods had made to light up the world from sparks that flew out of Muspelheim…. Moon guides the course of the moon, and rules its waxing and waning.

“Far away and long ago” (1920) by Willy Pogany

Both Máni and Sól are chased around the heavens by two huge wolves, or wargs, known as Hati Hróðvitnisson and Sköll, respectively. The wargs are said to be the sons of Fenrir, the giant wolf destined to kill the king of Norse gods, Odin.

Chapter Two of The Tollkeeper begins with the following quote:

“In the forest dwell troll-women, who are known as Ironwood-Women. The old witch gives birth to many giant sons.”

This is reference to the mother of Hati Hróðvitnisson, who is a giantess or “troll-woman” as well as a witch. She lives in the forest of known as Járnviðr (aka, “Ironwood”) and fosters giant sons, all of whom are apparently giant wolves.

A Dude Name Máni

Moon is also followed by two children, Hjúki and Bil, who were originally taken up from the earth by Máni.

Given the history of moon goddesses in Europe, it’s understandable that so many poems in the Western tradition allude to it as an alluring or virginal woman. In fact, it originally struck me as interesting and somehow incongruous that the moon is male in Norse mythology. As a satire of, as well as tribute to, all the verse that alludes to the moon as a woman, I wrote the following poem:

The skalds said the moon is a dude named Máni,

Who’s staying one step ahead of the wolves at his door,

A divorced dad who drinks and pays plenty of alimony

Plus support for two spoiled kids he loves to the core.

He sure as hell is no shrouded pale virgin of mystery

As the sad sack poets of romance tell in their dainty lore.

Hell, Máni’s just a longshoreman with aching knees

Who yanks at the tides with hooks, ropes, cables and more.

A couple of days a month, he’s too hungover to even see

So he calls in sick, draws the drapes, and soothes his sore

Head with frozen steaks, or chicken wings, or bags of peas.

Yeah, he may seem like a loser and a broody boor,

But, truth be told, Máni is so freaking steady and dependable that we

Can set our watches by his seasons of dejection, renewal and joy.

He’s not so different from other guys or gals, or you or me,

Maybe not so bright as sister Sól but Máni reflects our humanity.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MIT/GSFC - GRAIL's Gravity Map of the Moon

The post The Máni on the Moon Chased by a Walloping Warg appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

November 30, 2018

On the Endless Stream of TV Shows and Movies Based on Fairy Tales

Fairy tales date back 6,000 years, yet they continue to pop up in our psyches and the news. The tropes are timeless. …[F]airy tales also endure because they adapt, routinely reimagined and reinterpreted for new generations and audiences. Gritty or sunny, pared down or jazzed up, their themes and characters reverberate in headlines and popular culture, reflecting hope and fear. From princesses to emperors with no clothes, the surprising amount of fairy-tale scholarship by academics is testament to the impact of the genre.

That sounds about right to me, even if this is just advertising copy in the New York Times for a new show called Tell Me a Story. The idea of the show is to use three fairy tales to weave together a dark modern story set in New York.

I’ve not seen it, so I can’t comment on the show itself. But the concept of reinterpreting old myths, folktales and fairy tales for modern consumption is far from new. I’ve had the guilty pleasure of watching all the episodes of Grimm, for example. The acting was often cheesy and the plots hackneyed, but its satire and self-mocking humor kept me coming back. It was just fun to watch a police procedural in which the cop must regularly battle mythological creatures. (But how the heck did Nick end up with Adalind? Come on, now!)

Grimm is hardly alone, of course. In fact, there are so many movies and TV shows based on fairy tales that IMDb has a catalog that is 237 works long…and growing. Moreover, that’s just fairy tales, as opposed to myths and legends (though there’s bound to be overlap).

It’s a fascinating trend that keeps our modern fictions and mythologies, if you’ll forgive me, forever Jung.

Of course, my book The Tollkeeper is also a contemporary tale based on various myths and sagas, so I expect I’m a more than a tad biased in this direction.

The post On the Endless Stream of TV Shows and Movies Based on Fairy Tales appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

November 27, 2018

A Phony Interview with Mythologist Joseph Campbell

Joseph John Campbell was a Professor of Literature at Sarah Lawrence College who worked in comparative mythology and comparative religion. He became especially well-known for his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In it, he discusses his theory of the journey of the archetypal hero, an archetype that he thought appeared in various forms in mythologies throughout the world. (The Tollkeeper, by the way, often riffs on the hero archetype concept.) Campbell is also well known for coining the phrase “follow your bliss.” In fact, he was so good at coining phrases, that you can read inspirational Joseph Campbell quotes all over the Internet. The following is a phony baloney interview with Prof. Campbell created by threading together just a small portion of the (seemingly) zillions of Campbell quotes on the Web.

Interviewer: Thanks for agreeing to this interview, Mr. Campbell. We were surprised you could make it. I guess the reports of your death were, as they say, greatly exaggerated.

Joseph Campbell: Suddenly you’re ripped into being alive. And life is pain, and life is suffering, and life is horror, but my god you’re alive and it’s spectacular.

I: Okay, well said, thank you for that. Now, you lived a long and productive life…

JC: The privilege of a lifetime is being who you are.

On the Meaning of Meaninglessness

I: Sure, I guess. But what I wanted to ask is what you’ve learned from all your studies. When you boil it all down, what did you find the meaning of life is?

JC: Life has no meaning. Each of us has meaning and we bring it to life. It is a waste to be asking the question when you are the answer.

I: That sounds kind of existentialist. Maybe even postmodern. I thought your whole idea was that there are stories and myths that cross cultures and have a shared meaning.

JC: Myths are clues to the spiritual potentialities of the human life.

I: Right, but how can there be spiritual potentialities if life has no meaning?

JC: I don’t believe people are looking for the meaning of life as much as they are looking for the experience of being alive.

I: Really? Now that sounds a bit like Epicurus. Or maybe Nietzsche. So you really think life is meaningless?

JC: Life is without meaning. You bring the meaning to it. The meaning of life is whatever you ascribe it to be. Being alive is the meaning.

I: Wow, so, if being alive is the meaning, does that mean being dead is meaningless?

JC: Life is but a mask worn on the face of death. And what is death, then, but another mask?

On Following Your (Damned) Bliss

I: If life is meaningful but it’s only a mask on the face of death, then doesn’t that mean death is just as meaningful as life? Seems like a conundrum.

JC: Life is not a problem to be solved but a mystery to be lived. Follow the path that is no path, follow your bliss. Follow your bliss and the universe will open doors for you where there were only walls.

I: Okay, I’m sorry, but I’ve just got to say that sounds like fortune-cookie crap. Do you know how many liberal arts students have graduated with virtually no work skills just because they buy into that “follow your bliss” line?

JC: I think the person who takes a job in order to live – that is to say, for the money – has turned himself into a slave.

I: A slave, really? So, what’s that person supposed to do? Live on dumpster food? Dude, you spent your life in cushy academia. You never even lived in the real world. You’ve got some nerve…

JC: When you follow your bliss, you begin to meet people who are in the field of your bliss, and they open the doors to you.

I: Ah, okay, so you’re saying we should network more to succeed in our blissful pursuits?

JC: If you are on the right path you will find that invisible hands are helping.

I: I’d prefer the hands to be visible, you know, but I get the idea. Note to self: Join LinkedIn. By the way, didn’t you steal that invisible hand thing from Adam Smith?

JC: People forget facts, but they remember stories.

JI: Now you sound like the president. Are you saying you prefer stories to facts?

JC: The warrior’s approach is to say ‘yes’ to life: ‘yes’ to it all.

On Life as Improv

I: ‘Yes’ to it all. Neat. I think that’s a rule of improv, by the way.

JC: Nothing is exciting if you know what the outcome is going to be.

I: Again, an improv basic! I had no idea you were into that stuff. But, you know, some folks hate improv. It’s scary to just get up and wing it moment to moment.

JC: The ultimate dragon is within you, it is your ego clamping you down. The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.

I: So, you’re saying we should be bolder, to live with greater courage and whatnot.

JC: The big question is whether you are going to be able to say a hearty ‘yes’ to your adventure. You are the hero of your own story.

On Being a Hero

I: But that sounds kind of narcissistic, doesn’t it? Follow your bliss. Be your own hero.

JC: A hero is someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself.

I: That seems contradictory. I mean, how can I follow my own bliss while giving my life to something bigger than myself?

JC: Passion will move men beyond themselves, beyond their shortcomings, beyond their failures.

I: Passion, eh? You’re saying that to find my bliss, I’ve got to lose myself in something bigger than my own small life? Sounds like a great adventure. How do I go about it?

JC: Sit in a room and read – and read and read. And read the right books by the right people. Your mind is brought onto that level, and you have a nice, mild, slow-burning rapture all the time.

I: Wait, what? That’s your idea of a grand adventure? Reading a bunch of books?

JC: Every hero must have the courage to be alone, to take the journey for himself.

I: Seems like being alone is the opposite of seeking adventure.

JC: All the gods, all the heavens, all the hells, are within you.

On the Dark Night of the Soul

I: I get it: adventures are ultimately internal. That begs a question. How do we find our adventure? What sets us on the right path, aside from “bliss,” of course.

JC: Opportunities to find deeper powers within ourselves come when life seems most challenging. The dark night of the soul comes just before revelation.

I: You mean when we are down and out? Fallen on hard times?

JC: If you are falling, dive.

I: That sounds like a pretty tough path to bliss, Professor Campbell.

JC: If the path before you is clear, you’re probably on someone else’s.

I: Oh, joy. Everybody’s got to blaze their own darkened path! Couldn’t we all just go on a fabulous cruise together and enjoy ourselves? Seems like there’s already enough suffering in the world.

JC: Find a place inside where there’s joy, and the joy will burn out the pain. There is perhaps nothing worse than reaching the top of the ladder and discovering that you’re on the wrong wall.

I: I guess that’s the stuff of mid-life crises….wrong ladder and all that.

JC: We’re so engaged in doing things to achieve purposes of outer value that we forget the inner value, the rapture that is associated with being alive, is what it is all about. Regrets are illuminations come too late.

I: That pretty profound but also pretty depressing. Illuminations come too late…

JC: Your life is the fruit of your own doing. You have no one to blame but yourself.

I: That makes you sound like a big believer in free will. Are you?

JC: The fates lead him who will; him who won’t, they drag.

I: Not sure if that’s a yes or a no…

JC: If you do follow your bliss, you put yourself on a kind of track that has been there all the while, waiting for you, and the life that you ought to be living is the one you are living. Follow your bliss and don’t be afraid, and doors will open where you didn’t know they were going to be.

On the Meaning of Dance

I: You sure are hard to pin down philosophically but are consistent on all this bliss stuff. Is that what you taught your students?

JC: The job of an educator is to teach students to see vitality in themselves.

I: Not any more. The job is to teach the test. It’s so dismal. You would hate it. By the way, you married one of your former students, dancer-choreographer Jean Erdman. What did you learn from her?

JC: You don’t ask what a dance means. You enjoy it. You don’t ask what the world means. You enjoy it. You don’t ask what you mean. You enjoy it.

On Which Religion Is Best

I: I bet you’re a fan of Shiva, whose dance both creates and destroys the world. You’ve studied many religions. Any recommendations?

JC: In choosing your god, you choose your way of looking at the universe. There are plenty of gods. Choose yours. Your sacred space is where you can find yourself over and over again.

I: So it’s all back to me, again? Isn’t there one true faith, as they say?

JC: All religions are true but none are literal.

I: Dude, you’re so slippery! Everything’s choose-your-own-adventure with you.

JC: No one in the world was ever you before, with your particular gifts and abilities and possibilities.

I: Now that sounds like feel-good crap. You don’t really believe that, do you?

JC: If you can see your path laid out in front of you step by step, you know it’s not your path. Your own path you make with every step you take. That’s why it’s your path.

I: I guess that’s a yes. It must be nice to have it all figured out.

JC: He who thinks he knows, doesn’t know. He who knows that he doesn’t know, knows.

I: But then if you know that you don’t know, isn’t that thinking that you do know? Those are just basic rules of logic.

JC: You can’t have creativity unless you leave behind the bounded, the fixed, all the rules.

On Whether the Artist Is a Hero…or Vice Versa

I: Hmm, creativity trumps logic, does it? So, in your estimation, what, exactly, is the function of an artist?

JC: The function of artists is “the mythologization of the world.”

I: So, the artist’s job is to impart a mythical quality to her or his work. I guess that means that the artist is a hero, or maybe the hero is an artist. Does that mean that the path of the hero always leads to something new?

JC: There is what I would call the hero journey, the night sea journey, the hero quest, where the individual is going to bring forth in his life something that was never beheld before.

I: Then, I guess the hero’s art is really his or her own life, assuming the hero is brave enough to break their routine and risk the bliss-following gambit of you preach so hard.

JC: Breaking out is following your bliss pattern, quitting the old place, starting your hero journey, following your bliss. You throw off yesterday as the snake sheds its skin.

On Shit Happening

I: But let’s great real, Professor. Shit happens. Big plans can go belly up. People fall ill. I’ve seen it. What do you say to that?

JC: Nothing can happen to you that is not positive. Even though it looks and feels at the moment like a negative crisis, it is not. The crisis throws you back, and when you are required to exhibit strength, it comes.

I: Sounds like Nietzsche’s “that which does not kill me makes me stronger” stuff. But look how that guy ended up!

JC: You’ve got to find the force inside you.

I: Okay, Obi-Wan. Look, some people have horrible things happen to them, one after another, like they’re cursed.

JC: Respect your curses, for they are the instruments of your destiny. Whatever the hell happens, say, ‘This is what I need.’

I: How is that different from when somebody glibly says, “Don’t worry. Everything always ends up for the best”? Just because somebody suffers, it doesn’t make them a hero. Nor does it mean they’re going to wind up slaying the dragon. So what, exactly, is the point?

JC: The goal of life is to make your heartbeat match the beat of the universe, to match your nature with Nature.

On Life, Movies and the Holy Grail

I: Wow, we just jumped from Nietzsche to Lao-Tzu. But, seriously, you don’t think life is just one big hero quest, do you?

JC: Life is like arriving late for a movie, having to figure out what was going on without bothering everybody with a lot of questions, and then being unexpectedly called away before you find out how it ends.

I: Sounds like a Sartre play, but it’s nice to find that even you get annoyed by existence sometimes. Maybe that’s why you’re always mythologizing, trying to put down a layer of meaning over chaos. Okay, one last question. If life is a hero quest, then what’s the Holy Grail? And please don’t say it is literally the Holy Grail.

JC: The key to the Grail is compassion, ‘suffering with,’ feeling another’s sorrow as if it were your own. The one who finds the dynamo of compassion is the one who’s found the Grail.

I: Let’s end on that note. You, sir, remain an inspiration to millions. Thanks for being with us, if only in spirit.

Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?...

The post A Phony Interview with Mythologist Joseph Campbell appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

November 24, 2018

Even Today, Nothing Lights Up Art and Mythology Like Fire

Nothing lights the human imagination like fire.

Just think about all the (relatively) contemporary songs about fire. Here are some of my personal favorites:

But these represent just a tiny subset of art and literature inspired by fire. Telling stories and singing songs about fire is a tradition that goes back to the dawn of humanity and, of course, plays a key role in our mythologies. In fact, fire is so elemental (so to speak) to human beings that it has lots of origin myths, many including heroes or tricksters who steal or otherwise deliver fire to humanity at great personal cost.

That Gift Is Gonna Cost You, Prometheus

For many Westerners, the most famous fire myth is that of the titan Prometheus. According to Greek mythology, the boss god Zeus was worried that humankind would become too powerful if they acquired fire, so he forbade anyone from sharing it with them. But Prometheus, who shaped the first people out of water and earth, had a soft spot for his creations and so stole fire from Zeus’ lightning and smuggled it out of the heavens in a hollow stalk of fennel (you have to love mythical physics!).

This was fantastically generous, especially given that Prometheus wound up paying a terrible price for his transgression. He was chained to a rock and everyday had to endure an eagle (emblem of Zeus) feeding on his liver. The liver would grow back at night and then he had to suffer the same torture the next day and every day after that. (In some tales, Heracles finally freed Prometheus, which would be a more merciful ending to the tale.)

The Fire Theft Song Has a Global Beat

The tale of Prometheus is one of the better known ones in the West, but tales of fire thieves and gift-givers occur in many cultures. Here are just a few:

Māui Throttles a Mud Hen Till It Talks

Māori mythology, which stems from the native cultures of New Zealand, has the tale of how culture hero and trickster Māui deceived and then tortured one of the local mud hens into revealing how they made fire (which they did by rubbing dry, grooved hau wood with a stick). Unlike various other fire-bringers, Māui didn’t pay a price for stealing fire. But he did eventually come to a macabre (if hilariously Freudian) end, in case that makes any PETA activists feel better.

A Boy Thieves from the Sky Boss

In mythology of out Nigeria, there’s the tale of how the sky god Obassi Osaw refused to give fire to humanity. A boy went to work for Obassi and, in the classic tradition of inside-job heists, smuggled the fire out and brought it home to humanity. To punish the boy for his transgression (not to mention his chutzpah), Obassi Osaw made the boy lame. I guess it’s better than having your liver eaten for eternity, but it still seems a pretty harsh way to treat a juvenile miscreant.

A Rainbow Crow Gets Burned

In one tale from the Native American Lenni Lenape Tribe, there’s a character known as Rainbow Crow who goes to the Kijiamuh Ka’ong, the Creator Who Creates By Thinking What Will Be (a name that I think every supreme being should aspire to). Anyway, it turns out that the Creator is “thinking” winter because of all the snow and ice suddenly covering the Earth.

The Rainbow Crow, named for his shimmering feathers of rainbow hues, is selected to go to Kijiamuh Ka’ong to, well, ask her if she’d stop thinking wintry thoughts. But that’s a no-go because snow and ice apparently have spirits of their own. Instead, the Creator takes a stick, lights it via the sun, and gives it to Rainbow Crow so he can deliver fire to the Earth.

Except, as you might expect, the stick burns down and catches his gorgeous feathers on fire even as the smoke gets in his throat and lungs, ruining his amazing, better-than-Bieber voice. So, it turns out that he too pays a price for bringing fire, even though he doesn’t actually steal it. (As a side note, I suppose this may be how the mud hens got the secret of fire before humans did.)

The Rainbow Crow Goes Virtual

Fire is often viewed as a symbol for creativity. So it seems fitting that the Rainbow Crow myth was recently animated in honor of the Native American Heritage month. One recent article calls the film, Crow: The Legend, a “CGI short and an experiential virtual reality (VR) film that is the first VR movie to incorporate an indigenous world view.”

I think it’s pretty groovy that a Native American myth is not only reimagined for the cinema but for an up-and-coming tech-like virtual reality. The Rainbow Crow keeps right on carrying forward that flame of narrative ingenuity into the 21st century.

By the way, here’s a line I particularly liked in the original article: “Crow: The Legend also stars Oprah Winfrey, who makes her virtual animation film debut as The One Who Creates Everything by Thinking.” I don’t know exactly why that sentence tickles me. Maybe it’s the line “virtual animation film debut,” which feels like a wonderful bit of press-release verbiage, but I think it’s more about Oprah playing the title role of The One Who Creates Everything by Thinking. If anybody should be playing that role, it’s definitely Oprah.

The post Even Today, Nothing Lights Up Art and Mythology Like Fire appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

November 11, 2018

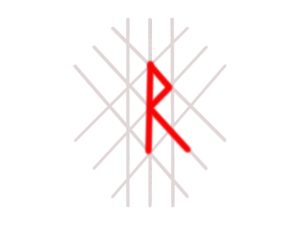

The Web of Wyrd and the Design of Norse Runes

The Web of Wyrd—which is portrayed by the cross-hatching of nine lines—represents the web of fate and alludes to the idea that the were “weavers of fate.” It has been said that the Web contains all the runes, which are letters in the runic alphabets used to write various Germanic languages. The name rune means “secret, something hidden,” indicating it was originally known to only a few. The myths of Odin, the Norns and others infer the runes had magical properties.

Runes Can Be Overlaid on the Web of Wryd

To check whether or not all the runes can fit somewhere into the Web of Wyrd, I mapped each of the runes from the Elder Futhark, which is the oldest of the rune alphabets. I created an infographic based on that exercise, which you can acquire by signing up for the The  Tollkeeper Blog. It’s quite lovely, and convincingly demonstrates that the Web can indeed contain most or all of the runes.

Tollkeeper Blog. It’s quite lovely, and convincingly demonstrates that the Web can indeed contain most or all of the runes.

I’m still not sure of whether the Web of Wyrd existed in the Norse era or is a more recent invention, possibly linked to Asatro, the modern worship of the Norse gods. Whichever it is, it’s an intriguing symbol. The name references the Norns, who were known to weave webs of fate, but it also echos the network of life that is presented by Yggdrasil, the Norse Tree of Life.

In addition, of course, the runic connection invokes the one of the more famous activities of the Norns: the carving of runes into wood. We should note, of course, the runes were seldom written but, rather, carved into wood, bone, stone, metal, or some other hard surface. The angular shapes of the runes lent themselves to carving. This largely explains how a cross-hatching of nine lines (which is basically the Web of Wyrd is) can contain them so well.

Thanks to Cyndi for the Web

By the way, if you get the paperback version of The Tollkeeper, you’ll notice that each chapter starts with a small icon of the Web of Wyrd. My lovely wife Cyndi created that version and has even made a t-shirt with the Web of Wyrd on it. Since runes play an important role in the book, it all makes sense in the end. It’s all, ahem, connected.

The post The Web of Wyrd and the Design of Norse Runes appeared first on The Tollkeeper.

November 3, 2018

Alfheim of the Elves and Our Shifting Sense of Self

Meadow Elves by Nils Blommér (1850)

A Colony of the Gods?

In Norse myth, Alfheim is one of the nine realms and, more specifically, the home of the elves. When you first hear about it, it sounds like a great vacation spot but, in truth, it’s a rather sketchy and poorly documented place. It comes up ever-so-briefly in “The Ballad of Grimnir”:

And Alfheim the gods

to Freyr once gave

as a tooth-gift in ancient times.

That attestation is often glossed over in the literature, but it is one nutty group of words. It states, in essence, that “the gods” gave Freyr (another god) the realm of the elves as a teething present! You see, a “tooth-gift” refers to the custom of making a present to a baby when it gets its first tooth.

So, let’s get this straight. The gods gave an entire realm packed with beautiful, noble creatures to a baby? Now, that sounds like some very serious colonialism.

Or Maybe the Aesir and/or Vanir Are Elves?

Another theory is that this Freyr actually was an elf. Snorri Sturluson, the author of the Prose Edda (aka, Younger Edda) reported that Freyr was one of the Vanir, which was one of the two flavors of Norse gods. But the term Vanir seems to have been rare in Eddaic and Skaldic verse, so some suspect that álfar and Vanir are different words for the same group of beings.

Just to add another level of complexity, there’s also evidence that the elves and the Aesir (that other flavor of Norse god) were the same. Wikipedia reports”

[E]lves are frequently mentioned in the alliterating phrase Æsir ok Álfar (‘Æsir and elves’) and its variants. This was clearly a well established poetic formula, indicating a strong tradition of associating elves with the group of gods known as the Æsir, or even suggesting that the elves and Æsir were one and the same. The pairing is paralleled in the Old English poem Wið færstice and in the Germanic personal name system; moreover, in Skaldic verse the word elf is used in the same way as words for gods.

The Creepiness of Light and Dark Elves

Okay, let’s move on the second mention of Alfheim in the Prose Edda.

There are many other fair homesteads there,” replied Har;

“one of them is named Elf-home (Alfheim), wherein dwell

the beings called the Elves of Light; but the Elves of Darkness

live under the earth, and differ from the others

still more in their actions than in their appearance.

The Elves of Light are fairer than the sun,

but the Elves of Darkness blacker than pitch.

This all sounds not-so-vaguely racist, with the distinctions between the “fair” Light Elves and the “blacker than pitch” Dark Elves. None of it is clear-cut, however, especially because the so-called Elves of Darkness are often associated with “swarthy” dwarves in the Eddas, and they are supposed to live in another place called Svartalfheim.

For now, let’s just point out that we learn precious little about the elves in the Eddas. Lots of questions remain unanswered, which is why today we have all kinds of contradictory notions of elves. In some cases, they’re viewed as demigods as large as humans but more beautiful, magical, athletic and even immortal. This image of elves has been fixed in our collective imaginations by JRR Tolkien.

At the same time, we also have the idea of small, merry, dancing beings living in trees (Keebler elves, anyone?) or stuffing stockings at the North Pole.

So, who really inhabits Alfheim? Are they a bunch of beautiful “fair” demigods who, sorry to say, would look a lot like ideal Hitler youth? Or are they spritely little folks dancing in circles and singing songs to cowbells?

Elves as a Cultural Rorschach Test

In many ways, elves represent our ideal: attractive, lithe, ageless, and powerful. But they also represent the “other”: mysterious, threatening, inhuman and never to be entirely trusted.

This contradiction tells us much about ourselves. We are constantly struggling to define who we are, who we wish to be and who we treat as worthy of being a member of our tribe. For example, are illegal immigrants into the U.S. carrying on a proud tradition by entering a rich land to which they were never invited and trying to make a better life for themselves? Or are they law-breakers undeserving of our empathy, the “dark elves” of our age?

Or consider the post-human movement, where people are striving to become more elf-like by reaching for perennial youth and fantastic new powers. Is this something most of us strive toward, or is it a Faustian bargain wherein we lose our souls and become less than human?

We will never know exactly what Alfheim looks like because it shifts along with our identities, ideals, anxieties and fears. Ultimately, we must inherit and inhabit Alfheim ourselves, colonizing that little known world with our own endless imaginings.

The cover feature image is Daniel Naczk's photo taken at Glasgow Botanic Gardens of

William Goscombe John's statue called The Elf, 1899

The post Alfheim of the Elves and Our Shifting Sense of Self appeared first on The Tollkeeper.