The Role of a “Fit Mythology” in the Norse Expansion

Mythologies often originate with religious and spiritual beliefs, but where do those beliefs come from?

Are they figments of fearful or mischievous imaginations? We can easily envision a prehistoric clan sitting around a fire, seriously weaving tense narratives about the angry gods that toss lightning bolts out of the hidden mysteries of looming thunder heads. Likewise, we can envision a bunch goofy hunters eating and farting Blazing-Saddles-style as they guffaw about how the foolish trickster spirit Coyote nearly killed himself running from a turkey feather.

Or are the roots of religion typically found in sublime and awesome solitude, a shiver up the back amid crystal stars in a vast desert, the complete and sudden certitude that a deity is present.

Whatever the origins of the original sparks–and I imagine there are many–there remains the question of why some spiritual beliefs grow into full-scale religions while others fade into obscurity.

Ironically, the answer to this question may boil down to the forces we call natural selection.

The Long Dispute

Why ironically? Because from the first days that the theory of natural selection was proposed by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, it was seen as threatening and antithetical to traditional religious beliefs, especially Christian ones. Today, 160 years after Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, the controversy and debate continues. It is a very extended dispute about the nature of reality.

“In fact,” Pew Research reports, “about one-in-five U.S. adults [still] reject the basic idea that life on Earth has evolved at all. And roughly half of the U.S. adult population accepts evolutionary theory, but only as an instrument of God’s will.”

Despite this ongoing antagonism, some seen the idea of natural selection–applied to cultures rather than species–as a useful tool when trying to determine how religions have developed, suggests a recent episode of the Hidden Brain podcast. Called “Where Does Religion Come From? One Researcher Points To ‘Cultural’ Evolution,” it largely focuses on the ideas of Azim Shariff, a psychology professor at the University of British Columbia.

From Smaller Nature Gods to Bigger Punisher Types

Shariff essentially argues that the agricultural revolution, which allowed human beings to congregate in much larger numbers than the typical nomadic hunter-gatherer group, demanded new religions for new ways of living. Before that revolution, human groups were typically smaller and culturally cohesive because so many people were related to one another. They are were, essentially, extended families walking around from place to place in search of food. Their gods tended to be more varied, less powerful, and less concerned about moral behaviors. Shariff states:

[I]t was only in the last 12,000 years that we started getting groups that bubbled up from beyond 100, 150 people to 1,000, 10,000 people. And what that means is that it needed something more than just our genetic inheritance [to hold the group together]. It needed a cultural idea. It needed a cultural innovation to allow us to succeed in these larger groups. And so one of the things that me and my colleagues have been arguing is that religion was one of these cultural innovations.

So, what kind of gods help large numbers of unrelated people cohere into cooperative groups? Powerful ones that are deeply interested in moral behaviors. Gods or a single God that will punish immorality, thereby keeping people on their best behaviors.

One course, podcasts are a limited format, and this one made it sound as if people evolved from animism to monotheism in one grand jump. Maybe you can make that argument for Judaism. But, in many parts of the world, agricultural peoples first developed polytheism, or the belief in multiple gods.

Where the Norse Gods Fit In

Probably the best known of the Western polytheistic traditions are the Greco-Roman and Norse myths. These gods fall somewhere in between the animist mythologies of hunter-gatherers and the monotheistic mythologies originating in the Middle East.

Their gods are neither single omnipotent rulers nor a varied hodgepodge of nature spirits. They are, in essence, complex congregations of powerful but flawed gods, led by an especially powerful and yet still limited god with many of the characteristics of mortal men: fear, depression, ambition, dauntlessness, uncertainty and more.

In the case of the Norse, the king god is Odin, of course, who is not the Alpha and Omega but, rather, a being born to specific parents, who can not control the ultimate fate of the universe, and who has had to struggle and sacrifice to achieve the limited wisdom he had.

Valhalla the Perfect Afterlife for a Warrior Invader Race

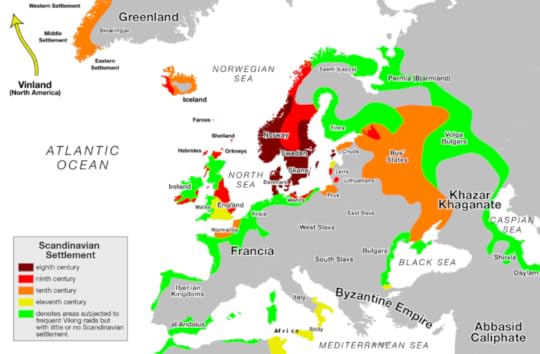

There are few practitioners of Norse religions today, though the modern variation known as Asatro does seem to have a small but passionate following. During the time of the Norse invaders that we now refer to as Vikings, the mythology was a boon to its practitioners. It helped them become among the most successful invaders and colonialists of their day, at least in and around Europe and what is now Russia.

According to Norse mythology, the way that a person enters the most desirable Viking heavens, typically known as Valhalla and Fólkvangr, is by dying in battle. Those who went to Odin’s Valhalla were a paradise for those who loved battle. Original sources have less to say about Fólkvangr, though it seems to have been another great hall and/or, based on the translation of the name, a great meadow or field. Others who didn’t die in battle were apparently mostly relegated to Helheimr, a cold and dark place.

In his blog Norse Mythology for Smart People, author Daniel McCoy reports:

The dead who reside in Valhalla, the einherjar, live a life that would have been the envy of any Viking warrior. All day long, they fight one another, doing countless valorous deeds along the way. But every evening, all their wounds are healed, and they are restored to full health. They surely work up quite an appetite from all those battles, and their dinners don’t disappoint…. They are waited on by the beautiful Valkyries.

(If you’ve read The Tollkeeper, then you know that Valkyries are pivotal to the story.)

Anyway, the implication is that by dying in battle, one either gets to go to a never-ending (till Ragnarok, that is) sporting and feasting event or gets to retire more quietly into the green fields of Fólkvangr.

Either way, it’s a great incentive for people to fight until death in a culture that, for 300 years or so, was predicated on daring, violence, conquest, adventure and the quest for personal glory. From a Darwinian point of view, these religious-based values helped the Norse spread their culture and genes–which till then were mostly isolated in the cold, dark and often inhospitable Northern climes–over much of the Western world, small parts of Africa, and “new worlds” such as Iceland, Greenland, and maybe even North America.

By Max Naylor – Public Domain

By Max Naylor – Public DomainThe Conversion to Christianity

Would this spread have occurred without their unique belief systems? I doubt it. We know that the Viking raids and conquests diminished once the Norse had accepted Christianity. But did they accept Christianity because they were done with their raiding, or vice versa? Or were other key factors, such as European ship-building technologies or the need to form alliances with their Christian conquests?

I believe these issues are so complex that there’s no way to properly answer those questions. Moreover, there have been plenty of Christian conquerors over history, which is a decent argument against my thesis.

Still, I suspect Norse mythology played a pivotal role for centuries, helping spur the raiders and traders that we now call Vikings into a lifestyle that had, from at least from an evolutionary point of view, many successes in its period of expansion.

How About Today?

If belief systems are themselves Darwinian forces, then how can we determine which myths are “selected for” in our current multimythic world?

How does one even judge? Via genetic expansions? Via wealth, health, happiness? It depends on how we classify success and competition.

But it does appear that certain mythologies have gained an upper hand over the last couple of centuries. One is capitalism, which has won out over competing mythologies (yes, I know most argue they are ideologies rather than mythologies) of communism, agrarianism or feudalism. Another is scientism, which has largely led to the spread of new technologies that allowed some cultures to dominate others over the last century or two.

These two mythologies interact with others, including religion itself. In fact, Shariff’s research suggests that some religion-based values, such as trust in those who share our worldviews, promote trade and, therefore, the economic success.

But will today’s mythologies continue to dominate human civilizations in the future? If not, what other mythologies will gain the upper hand?

Those are kinds of question that authors of speculative fiction play with all the time. But, given the length of this post, that needs to be a subject for another day.

Note: Image of Darwin and son William from Karl Pearson (1914-30) The life, letters and labours of Francis Galton, IIIa, Cambridge: University press, p. 341

The post The Role of a “Fit Mythology” in the Norse Expansion appeared first on The Tollkeeper.