A.R. Simmons's Blog: Musings and Mutterings, page 8

February 28, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 2

The CSI

In the initial Legendary Detectives post, we looked at Poe’s C, August Dupin, introduced in the 1840s story “Murders in the Rue Morgue.” Now we turn to the most famous detective of all time, Sherlock Holmes. Perhaps I can stir your memory or provoke you into reconsidering your image of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's iconic "consulting detective." The problem for us is that Sherlock Holmes has been portrayed by so many actors, and in so many movies and TV episodes, that our present view of him differs from the original character.

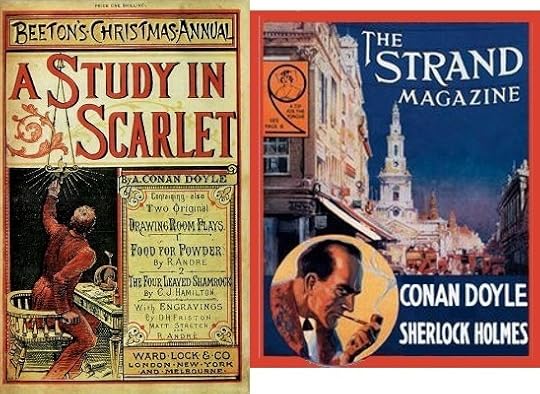

Conan Doyle introduces him in "A Study In Scarlet," published in Beeton's Christmas Annual in November of 1887. He continues to flesh him out in adventures published in The Strand magazine. Eventually, the mysteries total 56 short stories and four novels. In these, the author produces a detailed and consistent physical, emotional, and psychological portrait of the first great detective.

Unlike Poe’s paucity of detail as to Dupin’s appearance, Conan Doyle is quite precise in his physical description of Holmes. That’s good because so many actors have portrayed him that we may have a different picture of the man than the stories describe.

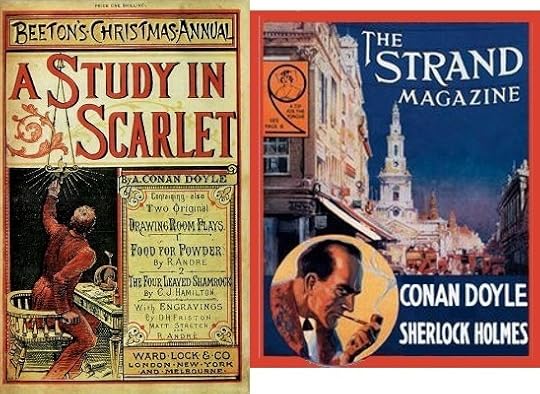

The author paints Holmes as a tall and lean black-haired man with piercing gray eyes beneath heavy dark-brown eyebrows. Thin firm lips and a hawk nose complete the thin intense face. He has sinewy arms and long thin fingers. His appearance is angular and wiry to the extreme. For me, the closest match among his portrayers was Peter Cushing. Compare the photo with the painting of Holmes on the Strand cover above.

I’ll not draw conclusions about Holmes's psyche, but only catalog what comes through the stories. He says of himself, "I use my head, not my heart." He abhors emotion as an impediment to rational thought, hence his aversion of women (whom he considers emotional as well as emotion-producing). Perhaps this also explains his disinclination to form new friendships. He has no time for small talk and casual acquaintances. He plays the violin, but otherwise has no interest in the arts (literature included—unless it is sensationalist press stories about mayhem and horror). Holmes is egotistical in the extreme, having no patience for lesser intellects and open contempt for inferior minds. He is cold, precise, and didactic in stating his conclusions. That could be tiring, but it's not.

Holmes is often restless, obsessive, and impatient. At other times, he is consumed with intense ennui which he escapes via drugs that were legal at the time: the famous seven-per cent solution of cocaine and morphine. Is it that his mind needs a puzzle to throw his switch on a bipolar disorder? Or is he, as Benedict Cumberbatch has him say, a “high-functioning sociopath?” I don’t know, but Conan Doyle would never have considered such things. In his day, psychiatrists were “alienists” and psychological disorders might be termed “fevers of the brain.” Holmes is what he is: an extreme enthusiast, at times insufferable, but vastly interesting.

But it's all about method, isn't it?

So what is the Holmes method?

How can he see things as so “elementary?”

To what extent Conan Doyle modeled Sherlock Holmes on Poe's Dupin is a matter of conjecture. Like the strange French detective, Holmes is preternaturally observant, not only of crime scene clues, but of facial expressions, body language, speaking mannerisms and inflections as well as other "tells." Neither miss details that others discount or fail to observe.

Both men are “human lie detectors.” They “cold read” so well that they seem to read minds. Each uses “creative imagination” to get into the minds and understand the actions of the perpetrator. However, Dupin relies on it, while Holmes relies on cold reason. Holmes is also a pioneer in forensic science. Doyle even has him author treatises on innovative CSI work. He breaks the case using logic, deduction, and science. And all of this began in an age when the official investigators were only becoming aware of the CSI tools that Holmes employed.

If he did not invent the mystery genre, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle certainly defined it for decades to come. Moreover, he was the prophet of real-life crime detection much as another Brit, Arthur C. Clarke, was the prophet of space science technology.

A Study in Scarlet

In the initial Legendary Detectives post, we looked at Poe’s C, August Dupin, introduced in the 1840s story “Murders in the Rue Morgue.” Now we turn to the most famous detective of all time, Sherlock Holmes. Perhaps I can stir your memory or provoke you into reconsidering your image of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's iconic "consulting detective." The problem for us is that Sherlock Holmes has been portrayed by so many actors, and in so many movies and TV episodes, that our present view of him differs from the original character.

Conan Doyle introduces him in "A Study In Scarlet," published in Beeton's Christmas Annual in November of 1887. He continues to flesh him out in adventures published in The Strand magazine. Eventually, the mysteries total 56 short stories and four novels. In these, the author produces a detailed and consistent physical, emotional, and psychological portrait of the first great detective.

Unlike Poe’s paucity of detail as to Dupin’s appearance, Conan Doyle is quite precise in his physical description of Holmes. That’s good because so many actors have portrayed him that we may have a different picture of the man than the stories describe.

The author paints Holmes as a tall and lean black-haired man with piercing gray eyes beneath heavy dark-brown eyebrows. Thin firm lips and a hawk nose complete the thin intense face. He has sinewy arms and long thin fingers. His appearance is angular and wiry to the extreme. For me, the closest match among his portrayers was Peter Cushing. Compare the photo with the painting of Holmes on the Strand cover above.

I’ll not draw conclusions about Holmes's psyche, but only catalog what comes through the stories. He says of himself, "I use my head, not my heart." He abhors emotion as an impediment to rational thought, hence his aversion of women (whom he considers emotional as well as emotion-producing). Perhaps this also explains his disinclination to form new friendships. He has no time for small talk and casual acquaintances. He plays the violin, but otherwise has no interest in the arts (literature included—unless it is sensationalist press stories about mayhem and horror). Holmes is egotistical in the extreme, having no patience for lesser intellects and open contempt for inferior minds. He is cold, precise, and didactic in stating his conclusions. That could be tiring, but it's not.

Holmes is often restless, obsessive, and impatient. At other times, he is consumed with intense ennui which he escapes via drugs that were legal at the time: the famous seven-per cent solution of cocaine and morphine. Is it that his mind needs a puzzle to throw his switch on a bipolar disorder? Or is he, as Benedict Cumberbatch has him say, a “high-functioning sociopath?” I don’t know, but Conan Doyle would never have considered such things. In his day, psychiatrists were “alienists” and psychological disorders might be termed “fevers of the brain.” Holmes is what he is: an extreme enthusiast, at times insufferable, but vastly interesting.

But it's all about method, isn't it?

So what is the Holmes method?

How can he see things as so “elementary?”

To what extent Conan Doyle modeled Sherlock Holmes on Poe's Dupin is a matter of conjecture. Like the strange French detective, Holmes is preternaturally observant, not only of crime scene clues, but of facial expressions, body language, speaking mannerisms and inflections as well as other "tells." Neither miss details that others discount or fail to observe.

Both men are “human lie detectors.” They “cold read” so well that they seem to read minds. Each uses “creative imagination” to get into the minds and understand the actions of the perpetrator. However, Dupin relies on it, while Holmes relies on cold reason. Holmes is also a pioneer in forensic science. Doyle even has him author treatises on innovative CSI work. He breaks the case using logic, deduction, and science. And all of this began in an age when the official investigators were only becoming aware of the CSI tools that Holmes employed.

If he did not invent the mystery genre, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle certainly defined it for decades to come. Moreover, he was the prophet of real-life crime detection much as another Brit, Arthur C. Clarke, was the prophet of space science technology.

A Study in Scarlet

Published on February 28, 2018 04:40

•

Tags:

detectives, genre, mystery, police-procedure

February 21, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 1

The Amateur Sleuth

I love mysteries. Nothing is more fun than becoming one of my favorite detectives with a good puzzle to solve. I know that most crime is uncomplicated. The bulk of it is stupid, banal, and squalid. There is little criminal genius in the real world, and our Moriartys are up to financial fraud, not “murder most foul.” Still, I can, and do, suspend disbelief gladly when I pick up a new novel or short story because I love being an investigator, a profiler, a criminologist, or a forensic expert—a sleuth of any stripe.

In this series of posts, I want to share with you some of my encounters with legendary detectives. I’ve followed some closely, been briefly introduced to others, but only know some by reputation. Let me share a few interesting things I know about them. I’m sure that you can list others that I will not include. And I’m equally sure that you know things about each of them that I will fail to mention. This list is a personal one. I make no claim to authority. As with all “best lists,” people will differ. That’s great. As they say, “a difference of opinions is what makes a horse race.”

Jonathan Kellerman has Alex Delaware remark that his friend Milo Sturgis is the only detective he knows that has actually detected anything. A detective goes about detecting by collecting physical evidence and asking questions. This “legwork,” is time-consuming whenever he gets a case without an obvious “who” that “did it.” Real life detectives handle such cases but rarely. The fictional ones do it every time, or else there would be no story for us to climb into.

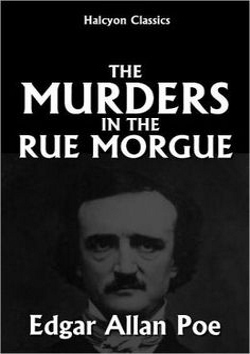

Let’s take a look at the first detective, Edgar Allen Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin from “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), and “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” (1842), followed by “The Purloined Letter” (1844). (I’ll not argue whether other detectives have a better claim to being first. If we have a difference of opinion, that’s good. It makes for stimulating conversation.)

C. Auguste Dupin

A professional detective, be he a cop or a private investigator, has time for the extensive legwork required because that’s the job. Amateur detectives, however, must find the time and have the money to pursue their cases. That’s why mystery writers often create detectives who are people of leisure with adequate resources. History supplies us with just such people. Beginning during the scientific revolution of the 17th century and continuing through the 19th century, some gentlemen of the nobility devoted their time, resources, and energy to advancing scientific knowledge. Robert Boyle, Henry Cavendish, and Antoine Lavoisier were of the nobility. Charles Darwin was a wealthy and connected doctor’s son. So when Poe chose a man of leisure for his detective, he followed historical precedent.

The narrator who introduces Le Chevalier (Sir) C. Auguste Dupin calls him “that unusual Frenchman.” Dupin’s once-rich noble family has apparently left him only modest means and its prestigious rank. He is a socially unattached man and eccentric. His life is books and a voyeuristic interest in the people among whom he moves with minimal and shallow interaction. He is coldly rational, egotistical, intellectually snobbish, and abrupt to the point of rudeness. Dupin is all brains and no soul. How that works with his being an amateur poet, I have no idea. He is obsessed with puzzles and enigmas. He doesn’t really care for abstracts like “justice.” Nor does he worry overmuch about the falsely-accused. He burns to solve the case for the mere satisfaction of solving it. In short, he’s brilliant and interesting, but not a nice guy. Does that sound like another detective you know? (Hint: he also has a sidekick who chronicles his cases.)

So how does this genius go about the job? He collects facts and then uses both sides of his brain. He pays intense attention to the details, especially the ones that seem to make no sense. He also notices what people do not say as well as what they do say. Dupin is adept at reading people. He notes their hesitations, their manner, their expressions, and their body language. You wouldn’t want to play poker with this strange fellow. The exact “how” leads to an understanding of the “why” which reveals the “who.” He applies a combination of cold logic and creative imagination to get into the head of the criminal. I suppose that makes him the first profiler as well as the first detective.

So how does this genius go about the job? He collects facts and then uses both sides of his brain. He pays intense attention to the details, especially the ones that seem to make no sense. He also notices what people do not say as well as what they do say. Dupin is adept at reading people. He notes their hesitations, their manner, their expressions, and their body language. You wouldn’t want to play poker with this strange fellow. The exact “how” leads to an understanding of the “why” which reveals the “who.” He applies a combination of cold logic and creative imagination to get into the head of the criminal. I suppose that makes him the first profiler as well as the first detective.

The Murders in the Rue Morgue

I love mysteries. Nothing is more fun than becoming one of my favorite detectives with a good puzzle to solve. I know that most crime is uncomplicated. The bulk of it is stupid, banal, and squalid. There is little criminal genius in the real world, and our Moriartys are up to financial fraud, not “murder most foul.” Still, I can, and do, suspend disbelief gladly when I pick up a new novel or short story because I love being an investigator, a profiler, a criminologist, or a forensic expert—a sleuth of any stripe.

In this series of posts, I want to share with you some of my encounters with legendary detectives. I’ve followed some closely, been briefly introduced to others, but only know some by reputation. Let me share a few interesting things I know about them. I’m sure that you can list others that I will not include. And I’m equally sure that you know things about each of them that I will fail to mention. This list is a personal one. I make no claim to authority. As with all “best lists,” people will differ. That’s great. As they say, “a difference of opinions is what makes a horse race.”

Jonathan Kellerman has Alex Delaware remark that his friend Milo Sturgis is the only detective he knows that has actually detected anything. A detective goes about detecting by collecting physical evidence and asking questions. This “legwork,” is time-consuming whenever he gets a case without an obvious “who” that “did it.” Real life detectives handle such cases but rarely. The fictional ones do it every time, or else there would be no story for us to climb into.

Let’s take a look at the first detective, Edgar Allen Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin from “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), and “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” (1842), followed by “The Purloined Letter” (1844). (I’ll not argue whether other detectives have a better claim to being first. If we have a difference of opinion, that’s good. It makes for stimulating conversation.)

C. Auguste Dupin

A professional detective, be he a cop or a private investigator, has time for the extensive legwork required because that’s the job. Amateur detectives, however, must find the time and have the money to pursue their cases. That’s why mystery writers often create detectives who are people of leisure with adequate resources. History supplies us with just such people. Beginning during the scientific revolution of the 17th century and continuing through the 19th century, some gentlemen of the nobility devoted their time, resources, and energy to advancing scientific knowledge. Robert Boyle, Henry Cavendish, and Antoine Lavoisier were of the nobility. Charles Darwin was a wealthy and connected doctor’s son. So when Poe chose a man of leisure for his detective, he followed historical precedent.

The narrator who introduces Le Chevalier (Sir) C. Auguste Dupin calls him “that unusual Frenchman.” Dupin’s once-rich noble family has apparently left him only modest means and its prestigious rank. He is a socially unattached man and eccentric. His life is books and a voyeuristic interest in the people among whom he moves with minimal and shallow interaction. He is coldly rational, egotistical, intellectually snobbish, and abrupt to the point of rudeness. Dupin is all brains and no soul. How that works with his being an amateur poet, I have no idea. He is obsessed with puzzles and enigmas. He doesn’t really care for abstracts like “justice.” Nor does he worry overmuch about the falsely-accused. He burns to solve the case for the mere satisfaction of solving it. In short, he’s brilliant and interesting, but not a nice guy. Does that sound like another detective you know? (Hint: he also has a sidekick who chronicles his cases.)

So how does this genius go about the job? He collects facts and then uses both sides of his brain. He pays intense attention to the details, especially the ones that seem to make no sense. He also notices what people do not say as well as what they do say. Dupin is adept at reading people. He notes their hesitations, their manner, their expressions, and their body language. You wouldn’t want to play poker with this strange fellow. The exact “how” leads to an understanding of the “why” which reveals the “who.” He applies a combination of cold logic and creative imagination to get into the head of the criminal. I suppose that makes him the first profiler as well as the first detective.

So how does this genius go about the job? He collects facts and then uses both sides of his brain. He pays intense attention to the details, especially the ones that seem to make no sense. He also notices what people do not say as well as what they do say. Dupin is adept at reading people. He notes their hesitations, their manner, their expressions, and their body language. You wouldn’t want to play poker with this strange fellow. The exact “how” leads to an understanding of the “why” which reveals the “who.” He applies a combination of cold logic and creative imagination to get into the head of the criminal. I suppose that makes him the first profiler as well as the first detective.The Murders in the Rue Morgue

Published on February 21, 2018 06:31

•

Tags:

detectives, genre, mystery, police-procedure

December 30, 2017

About That Plot Hole You Repaired.

Okay. So, you found a hole in your plot.

What to do? Fix it.

A good analogy for the process is road repair. Whenever a pot hole threatens to make the road uncomfortable if not impassable, a road crew is sent out to patch it. The problem is that a poorly patched pot hole becomes a bump which makes the desired smooth passage—well, not so smooth. That is not good road work, and the equivalent plot patching is not good editing.

The well repaired pot hole will go unnoticed. It will be as if the pot hole never existed. So should your repaired plot holes be. The ideal repair of your story will make your reader’s journey so smooth that he enjoys the ride without distracting holes and bumps.

So, what constitutes a good patch? The answer is that it depends upon the nature of the hole. If it is only a small and shallow hole, say you write “before” when it should have been “after,” a simple substitution of the correct word will solve the problem and make the going seamless. However, what if the hole is a gaping chasm? For example, what if your heroine is saved in Chapter 30 by the sudden appearance of a character who died in Chapter 6? This might require the demolition and repaving of a large section of the road. If you do not carefully examine and repair the entire “road” from Chapter 6 to Chapter 30, your story may become so muddled that your reader will quit in disgust.

I know that editing is not as much fun as writing, but it can be very rewarding. A well-crafted story is what we strive for. We begin at the off-ramp (the opening scene) and a destination (the climax), but the story is the journey. There are interesting twists, turns, jolts, disappointments, obstacles to overcome, and successes. These are some of the things that make the journey fun. Things can and should be encountered unexpectedly, but they should not come illogically. Every time our reader has to stop and try to reconcile something he encounters that conflicts with another part of the story, we are taking him on a detour around a plot hole. Do you know anyone who enjoys such detours? I do: a book doctor who is paid to fix a book that perhaps shouldn’t have been written.

Whenever a beta reader points out an inconsistency, we should take it seriously and do the necessary repairs while remembering that we are not being paid by the hour, but by the job. Writing is as much craft as art. Unlike street planners, we writers must not only plot the way, we must also lay the roadbed, repairing our mistakes as we go.

Published on December 30, 2017 09:30

•

Tags:

case-file, holes-in-the-plot, murder-book, mystery, plot, plot-holes, writing

December 19, 2017

You Have a Hole in Your Plot

“You have a hole in your swing.” is a line from the Tom Sellick movie “Mr. Baseball.” A hitter with a hole in his swing is vulnerable. Since the batter has more than one swing per at bat, the hole may not be fatal. The author who has a hole in his “at bat” may soon find himself losing his present and potential readers. There is no excuse for leaving a hole in your plot. Edit. Edit. Edit. That’s why Hemmingway advised to write drunk, and edit sober.

Although never good, some genres can tolerate a small hole or two, horror and fantasy, for example. Not mysteries. The plot is the all in all. Mystery readers are perhaps the smartest and most careful of readers. When they plop down good money for a book, they expect twists and turns, red herrings, subterfuge, false flags, and all manner of misleads—but not plot holes. The rule of mysteries may be “Nothing is as it seems,” but the caveat is “until the end.” Mystery readers will not tolerate kludges. A key fact appended at the end to make the incomprehensible comprehensible is not acceptable.

If you write detective stories or police procedurals or cozies, a good way to keep your ducks in order is to compile a case file just as a professional detective would do. Compile your own “murder book,” lest the victim be you

Published on December 19, 2017 10:18

•

Tags:

case-file, holes-in-the-plot, murder-book, mystery, plot, plot-holes, writing

October 25, 2017

The Missing Scenes

I don’t know if other authors write scenes that they never intend to put into a novel or not. I do—regularly. I suppose that is because I’m a “method” writer. Instead of just telling the story, I have to hear the characters speak and experience the action.

Consequently, when something happens that must remain hidden from the reader in order to keep the mystery and suspense, I find it necessary to write the scene so that the characters’ actions are authentic, correctly motivated, and believable.

In some stories, there is just a single scene that must be written only to be revealed in snippets of dialog or thought. In some, like The Daughter and Devil’s Run, there are several. I may not share the scene with the reader, but I must live it before I can continue with the story. If I cannot lose myself in the story I am trying to tell, I have no chance of staying engaged enough to finish. If I find myself going through the motions, I quit—at least for a while. I have even abandoned a novel completely. After all, how could I expect a reader to remain engaged if I can’t?

These missing scenes are important, and often intense, even horrific. Like in real life, horrors that characters experience are referred to, but not detailed. For example, soldiers who have gone through the trauma of combat seldom talk about it. Yet, to understand a person, we must know a little about the life-changing events that they have survived.

Horrible violence, sickening gore, and intense sex might be part of a character’s past, but I see no redeeming benefit for including them in my stories. To tell the truth, I can’t write such things, even if I intend to relegate them to the cutting room floor. So, the scenes may be missing, but they are not invisible. We do glimpse them, if only in reflections.

Published on October 25, 2017 06:31

•

Tags:

motivation, mystery, scenes, suspense, writing

September 22, 2017

Small-towns; New Paint on Old Bricks

This is a photo taken in downtown Birch Tree, Missouri. a small Ozark village at the intersection of Highways 60 and 99. I've narrowed it to what I think is emblematic of such towns as they struggle to survive and remain relevant. It's not that they don't matter. It's that they are not economically viable. They remind me of the "tie hackers" trying to eke out an existence by hand-making railroad ties after the lumber boom used up the best of the forest and moved on, leaving them behind.

The stop sign, facing into the town, seems to be imploring the young not to leave.

Going to a small town can be a trip into our cultural past. Look at this Coke ad painted on the brick wall at the corner of the main street. In my section of the Ozarks, there are many such backwater villages that were once vibrant centers of trade. Life back then was much more local than it is today. Every “First Street” was lined with merchants shops selling goods and services that are now bought at the chain discount store out on the highway or perhaps in a neighboring town.

Once the “Farm to Market” roads (paved in the middle of the last century to “ . . . get Missouri out of the mud”) carried agricultural products to the town and rural shoppers to into town (on Friday or Saturday for the most part) to buy the few dry goods and groceries needed to supplement what was produced on the homestead farm.

Perhaps a trip to the shoe repair place was needed to re-sole a pair of work boots or Sunday-go-to-meeting dress shoes. Maybe there was a trip to the two-seat barber shop.

The downtown was a going thing, and definitely a place to window shop, perhaps at the local Woolworth, Ben Franklin, or Newberry’s.

I remember people in the early 1960's debating whether or not the new-fangled shopping center coming to my town would “go over.” Go over it did, driving one of the earliest nails in the coffin of old town.

I think the thing that really did in the outlying towns, however, was the production of better automobiles and the rising expectations of their younger generations.

The intensely local way of life with all its close-knit and traditional ways died a natural death, hastened by the arrival of mass media, reliable personal transportation, and the decreasing viability of the small family farm. There was also the ages old story of changing trade routes. When passenger trains were no longer a primary means of transportation, the local depot either closed or only opened for a few stops a week.

There’s no going back to a simpler time, and I have a feeling that it wouldn’t be all that simple anyway. We are products of our own time, and that’s where we fit. Truth to tell, there never was a “golden age.” If it seems that way, it's because, as the song The Way We Were says, "time has rewritten every line." The past is a wonderful place to visit because it tells us where we came from. But we can’t live there even if we want to.

The next time your travels lead you to one of these small towns, take the time to look around and imagine what it was like for the people who built and inhabited it. It may tell you a story worth the contemplation.

The stop sign, facing into the town, seems to be imploring the young not to leave.

Going to a small town can be a trip into our cultural past. Look at this Coke ad painted on the brick wall at the corner of the main street. In my section of the Ozarks, there are many such backwater villages that were once vibrant centers of trade. Life back then was much more local than it is today. Every “First Street” was lined with merchants shops selling goods and services that are now bought at the chain discount store out on the highway or perhaps in a neighboring town.

Once the “Farm to Market” roads (paved in the middle of the last century to “ . . . get Missouri out of the mud”) carried agricultural products to the town and rural shoppers to into town (on Friday or Saturday for the most part) to buy the few dry goods and groceries needed to supplement what was produced on the homestead farm.

Perhaps a trip to the shoe repair place was needed to re-sole a pair of work boots or Sunday-go-to-meeting dress shoes. Maybe there was a trip to the two-seat barber shop.

The downtown was a going thing, and definitely a place to window shop, perhaps at the local Woolworth, Ben Franklin, or Newberry’s.

I remember people in the early 1960's debating whether or not the new-fangled shopping center coming to my town would “go over.” Go over it did, driving one of the earliest nails in the coffin of old town.

I think the thing that really did in the outlying towns, however, was the production of better automobiles and the rising expectations of their younger generations.

The intensely local way of life with all its close-knit and traditional ways died a natural death, hastened by the arrival of mass media, reliable personal transportation, and the decreasing viability of the small family farm. There was also the ages old story of changing trade routes. When passenger trains were no longer a primary means of transportation, the local depot either closed or only opened for a few stops a week.

There’s no going back to a simpler time, and I have a feeling that it wouldn’t be all that simple anyway. We are products of our own time, and that’s where we fit. Truth to tell, there never was a “golden age.” If it seems that way, it's because, as the song The Way We Were says, "time has rewritten every line." The past is a wonderful place to visit because it tells us where we came from. But we can’t live there even if we want to.

The next time your travels lead you to one of these small towns, take the time to look around and imagine what it was like for the people who built and inhabited it. It may tell you a story worth the contemplation.

Published on September 22, 2017 03:38

•

Tags:

culture, golden-age, heritage, history, ozarks, past, reality, sleepy-town, small-town

September 4, 2017

A Character Adds Herself

I was leery about adding a major character to the Richard Carter novels, especially such a strong one as Kit Kittredge. After all, Jill is already a stronger figure than Richard, the title character. I know. I know. Her strength is composed of the "traditional" traits of our culture. She is the rock of the family and the exemplar of wifely and motherly virtues, something that tends to offend "girl kicks butt" aficionados. (I'm told by someone very close to me that if I don't think being a wife and mother while being a co-equal breadwinner takes real strength, I don't know which end is up.)

Jill has undergone and weathered harrowing violence and has found the courage and will to overcome both emotional and physical attacks that could (and do) destroy all but the strongest of us. In a sense, such a strong character takes up a lot of the oxygen in the room. I wasn't ready to put Richard through that. He's had a lot of trauma in his life.

I'm not your average fool, however, and I realize that the majority of readers these days are women (bless them). That is not the reason I have written stories with strong female characters, some victims, some villains, some rivals and/or cohorts of Richards. I include them because they are the most interesting people that I know or can conceive of.

Kit, like visiting deputy Woodie Koeltz (ROAD SHRINES) and PI Sarah Rafferty (COLD TEARS) was meant to be a one-story major character in Journey Man. However, at the end of the story, she refused to leave my mind and go back to her native Miller County. She had become to involved with Guidry and Jill, and too important as a role model for Mirabelle to leave as I commanded. In Devil's Run, she established herself as a permanent member of the Hawthorn force.

What can I say? She intimidated me. It's not the first time that has happened to me.

The truth is, she is just too interesting for me to do without.

Published on September 04, 2017 04:46

•

Tags:

characters, female-lead, identification, investigator, lady-cop, strong-female

August 19, 2017

On Traveling the Old Roads.

While researching for a new novel, we take frequent road trips through the hills of south-central Missouri. Sometimes we turn off the present highways onto the roads of the past, those sections of highway now bearing county numbers. The roads are often poorly maintained, but are well worth traveling (as long as you have a good map). These two-lane blacktops take the nostalgic traveler into the receding past. There, the old bridges are rusted metal structure that give great views of the creeks and rivers we cross in stark contrast to the concrete view-blocking (but safer) bridges we see on our main highways today.

For us, the attraction to these winding, narrow, shoulderless byways is that they conjure a feeling of the past. They remind us—no, takes us to the time when the boredom of a long trip was broken by reading Burma Shave signs and stopping for lunch at our favorite cafe, The Shade Tree Diner which we had to reach by crossing a farmer's fence and wading through waist-high fescue pasture.

It was a time of isolated two-pump service stations and country corner stores where we had to pay a two cent deposit on our glass soda bottles.

Try it. A trip into the past isn't as distant as you imagine.

Published on August 19, 2017 06:13

•

Tags:

childhood, countryside, memories, nostalgia, old-roads, research, road-trips

July 31, 2017

Do You Insist on Genre Formula?

Please take a look at the labels in the image below.

Okay. You buy a book billed as a mystery and it turns out to have paranormal or fantasy themes so entwined with the mystery that you find it difficult to suspend disbelief and enjoy the read. We've all been there in a sense. Maybe the cover illustration was so striking that it tempted you to buy a book that just wasn't your cup of tea or what an excellent illustrator led you to believe it would be.

As an author, I feel it my responsibility to accurately label my stories. That, however, is not always as easy as one might think. Publishing on Amazon provides only a set number of genre labels. For example I can't label a book as a combination of crime, mystery, police procedural (or amateur sleuth), family saga, and suspense. I write a series, and several of those labels apply to each story. I try to give enough information in the "Product Description" to satisfy potential readers' curiosity because I would rather lose a potential reader than irritate him.

Back to the original question: do you as a reader want a detailed and accurate genre label?

I ask because, for me at least, a story goes where it will. Let's say that you are a cozy mystery fan. Do you feel misled if a cozy mystery features a character or two whose traits drift too close to what you might expect in a hard-boiled mystery?

My stories feature a small-town cop and his family, including his daughter who ages at about a year per novel. Many of the elements of cozy are present, but there is occasional intense (though not graphic) violence. Likewise, there is mild profanity at times. Sex scenes are absent, but the violence and profanity (thought slight) keep me from calling my stories cozies. Likewise, the absence of graphic content keep me from labeling them hard-boiled.

So am I doing enough when I insert the information in the product definition? What do you want from the author when it comes to genre description?

Okay. You buy a book billed as a mystery and it turns out to have paranormal or fantasy themes so entwined with the mystery that you find it difficult to suspend disbelief and enjoy the read. We've all been there in a sense. Maybe the cover illustration was so striking that it tempted you to buy a book that just wasn't your cup of tea or what an excellent illustrator led you to believe it would be.

As an author, I feel it my responsibility to accurately label my stories. That, however, is not always as easy as one might think. Publishing on Amazon provides only a set number of genre labels. For example I can't label a book as a combination of crime, mystery, police procedural (or amateur sleuth), family saga, and suspense. I write a series, and several of those labels apply to each story. I try to give enough information in the "Product Description" to satisfy potential readers' curiosity because I would rather lose a potential reader than irritate him.

Back to the original question: do you as a reader want a detailed and accurate genre label?

I ask because, for me at least, a story goes where it will. Let's say that you are a cozy mystery fan. Do you feel misled if a cozy mystery features a character or two whose traits drift too close to what you might expect in a hard-boiled mystery?

My stories feature a small-town cop and his family, including his daughter who ages at about a year per novel. Many of the elements of cozy are present, but there is occasional intense (though not graphic) violence. Likewise, there is mild profanity at times. Sex scenes are absent, but the violence and profanity (thought slight) keep me from calling my stories cozies. Likewise, the absence of graphic content keep me from labeling them hard-boiled.

So am I doing enough when I insert the information in the product definition? What do you want from the author when it comes to genre description?

Published on July 31, 2017 07:27

•

Tags:

cozies, cozy, genre, genre-formula, mystery, product-description, suspense

July 27, 2017

Pilot: This Changes Everything; Mirabelle

The single most life-changing event for decent people is the birth of a first child. At the beginning of the third book (Canaan Camp), Richard is gainfully employed in a job that is as close as he will ever get to major law-enforcement. He is a rural “road deputy,” one step above an unpaid auxiliary deputy. Despite the lack of excitement (he’s had more than his share of that), he would be contented if it weren’t for his conviction that Jill has sacrificed her career to save him from his unmanly weakness. He would insist that they leave the hills and get her academic career back on track, but the very idea of giving up his “nothing job” is literally as depressing as approaching death.

Jill is settling into a community college, reasoning that being a professor in the Ozarks, although a far cry from being one in a prestigious university, is at bottom the same profession. Besides, she and Richard are living in the sort of place people go to “get away from it all,” which is good. It’s time for less drama in their lives. She is, of course, rationalizing. Yet Jill is convinced that she has made the wise choice in moving them to Blue Creek. Richard needs the job, and she needs him.

Then it happens. Normally meticulously careful, she inexplicably mismanages her birth control and becomes pregnant. Suddenly, the carefully-constructed new life she has worked out in order to save their marriage threatens to collapse. The last thing their fragile world needs is the complication of an unwanted child.

Richard, in typical male oblivion, thinks that Jill got pregnant in order to “fix” things by moving him past his moodiness. And it has as far as he’s concerned. He suddenly decides that he cannot afford to allow depression to dominate his life any longer. He sees her decision to have a baby as a vote of confidence in him. As far as he is concerned, this changes everything.

Jill is heartened by his reaction, but is far too wise and cautious to think that his demons can be exorcised so easily. She realizes something that Richard perhaps never will: he is suffering from PTSD. As her pregnancy proceeds, Jill becomes increasingly glad that she has engineered their move to the rural Ozarks. She has always dreamed of a having a loving family with the full complement of functioning parents, and thinks that Blue Creek will be a safe and wonderful world for their child to grow up in. Being a realist, however, she knows that problems will arise. No matter. She and Richard will be equal to the task.

They name their little girl after Jill’s only parent, her maiden aunt, Mirabelle.

Published on July 27, 2017 02:55

•

Tags:

characters, evolving-characters, mystery, ptsd, realistic-characters, series, suspense

Musings and Mutterings

Posts about my reading, my writing, and thoughts I want to share. Drop in. Hear me out. And set me straight.

- A.R. Simmons's profile

- 59 followers