A.R. Simmons's Blog: Musings and Mutterings, page 7

July 13, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 10

MISS MARPEL

Female version of the “gentleman sleuth.”

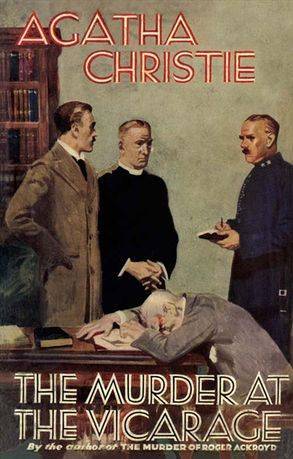

Dashiell Hammett may have taken murder out of the vicar’s garden, but Agatha Christie used Miss Marple put it there. In fact, the novel that introduces us to the shrewd old lady is

The Murder at the Vicarage.

It is difficult to imagine a detective as different from Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot than the elderly Miss Marple.

Margret Rutherford

The first Miss Marple of film.

Patterned after the old ladies the author encountered in English villages, the wily old lady solves cases by seeing parallels and connection that no one else appreciates. She has, in fact, done what amounts to post-doctoral work as a criminologist by a lifetime of observing crime.

“There is a great deal of wickedness in village life,” she says.

Miss Marple is a bit of a profiler, quickly seeing the hidden motives and passions behind what appear to be inexplicable crimes. Like a master pathologist, she is first and foremost a diagnostician, sorting the true motive among many possible ones. Her long and observant life has rendered this harmless old lady quite familiar with mayhem. As she says, she has seen a great deal of the darker side of human nature.

Of course, she needs “grist for her mill,” evidence only available to the professional investigators. This is often supplied by her friend, Sir Henry Clithering, a retired Police Commissioner who is still privy to official information.

Like many later sleuths, Miss Marple is usually underestimated. People dismiss her as a nosy old lady going on and on about stories from her past. But the things that come to her mind bring things into focus. The human mind is, of course, a pattern finder, and that is Miss Marple’s primary skill. Things fall into place for her.

Kimberley Nixon as Miss Marple

on Masterpiece Theater

Female version of the “gentleman sleuth.”

Dashiell Hammett may have taken murder out of the vicar’s garden, but Agatha Christie used Miss Marple put it there. In fact, the novel that introduces us to the shrewd old lady is

The Murder at the Vicarage.

It is difficult to imagine a detective as different from Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot than the elderly Miss Marple.

Margret Rutherford

The first Miss Marple of film.

Patterned after the old ladies the author encountered in English villages, the wily old lady solves cases by seeing parallels and connection that no one else appreciates. She has, in fact, done what amounts to post-doctoral work as a criminologist by a lifetime of observing crime.

“There is a great deal of wickedness in village life,” she says.

Miss Marple is a bit of a profiler, quickly seeing the hidden motives and passions behind what appear to be inexplicable crimes. Like a master pathologist, she is first and foremost a diagnostician, sorting the true motive among many possible ones. Her long and observant life has rendered this harmless old lady quite familiar with mayhem. As she says, she has seen a great deal of the darker side of human nature.

Of course, she needs “grist for her mill,” evidence only available to the professional investigators. This is often supplied by her friend, Sir Henry Clithering, a retired Police Commissioner who is still privy to official information.

Like many later sleuths, Miss Marple is usually underestimated. People dismiss her as a nosy old lady going on and on about stories from her past. But the things that come to her mind bring things into focus. The human mind is, of course, a pattern finder, and that is Miss Marple’s primary skill. Things fall into place for her.

Kimberley Nixon as Miss Marple

on Masterpiece Theater

Published on July 13, 2018 10:40

•

Tags:

amateur-sleuth, cozy, detectives, genre, mystery, police-procedure, strong-female-character

June 25, 2018

I Love Reader Reviews

I read every review. I admit it cheerfully.

What I never do, however, is respond. No matter how much I want to thank a reader for finding one of my novels worthy of their time and attention, and no matter how much I want to argue with those who think I’m a hack, I simply won’t do it.

That said, I take all reviews seriously, positive or negative. I read both types of reviews carefully in hopes of getting feedback that will make the next novel better. If an author doesn’t get reviews, he is like a would-be marksman shooting without ever seeing the bullseye. I wish I could convey to the reader, even the casual one how important his/her opinion is.

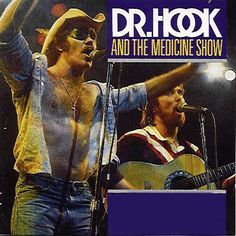

I would be less than truthful if I told you that a negative review is comfortable to read. After all, I have yet to write a novel that didn’t take the better part of a year’s hard work to produce. Having it rejected is bad enough. Having it skewered and panned is awful. That said, the story did not work for the negative reviewer, and I need to know why. Sometimes it’s simply a matter of taste. As the famous philosopher Dr. Hook once said, “Some folks like pork chops and some folks like ham hocks and some folks like vegetable soup.”

What I served up was something other than their favorite food. Sometimes the objection is that I failed to follow the genre formula. At other times it’s that I used a writing device like the flashback for which the reader has a dislike. Nevertheless, knowing what a reader likes and dislikes is helpful.

Good reviews simply make my day, but more importantly, they tell me what works. I love hearing that my style is good, my characters interesting, and my plots exciting. Most of all, though, I like hearing that the reader enjoyed the story. That means that he/she was drawn in, stayed in, and vicariously lived my yarn.

I find it fascinating when a reader really likes, or really detests one of my characters. If you found yourself "living" a particular character, drop me a comment. I would really like to hear from you.

A review doesn’t have to be one hundred per cent laudatory for it to qualify as good. Quite often I get a review that tells me both what they liked and disliked in my novel. What could be better than that? The reader cared enough about my story to include positive criticism.

Below are some of the more negative comments I’ve received (I won’t reproduce the positive ones because that’s too much like bragging).

“The book was too long.”

“There were too many characters.”

“There was too little (or too much) backstory.”

“There were no strong female characters.”

That last one is the only one I’ll argue with. My stories are full of extremely strong women, and, being a Chauvinist, I must defend them. Some of the ladies are villains. But that shouldn't surprise you. As Kipling reminds us, “. . . the female of the species is more deadly than the male.”

What I never do, however, is respond. No matter how much I want to thank a reader for finding one of my novels worthy of their time and attention, and no matter how much I want to argue with those who think I’m a hack, I simply won’t do it.

That said, I take all reviews seriously, positive or negative. I read both types of reviews carefully in hopes of getting feedback that will make the next novel better. If an author doesn’t get reviews, he is like a would-be marksman shooting without ever seeing the bullseye. I wish I could convey to the reader, even the casual one how important his/her opinion is.

I would be less than truthful if I told you that a negative review is comfortable to read. After all, I have yet to write a novel that didn’t take the better part of a year’s hard work to produce. Having it rejected is bad enough. Having it skewered and panned is awful. That said, the story did not work for the negative reviewer, and I need to know why. Sometimes it’s simply a matter of taste. As the famous philosopher Dr. Hook once said, “Some folks like pork chops and some folks like ham hocks and some folks like vegetable soup.”

What I served up was something other than their favorite food. Sometimes the objection is that I failed to follow the genre formula. At other times it’s that I used a writing device like the flashback for which the reader has a dislike. Nevertheless, knowing what a reader likes and dislikes is helpful.

Good reviews simply make my day, but more importantly, they tell me what works. I love hearing that my style is good, my characters interesting, and my plots exciting. Most of all, though, I like hearing that the reader enjoyed the story. That means that he/she was drawn in, stayed in, and vicariously lived my yarn.

I find it fascinating when a reader really likes, or really detests one of my characters. If you found yourself "living" a particular character, drop me a comment. I would really like to hear from you.

A review doesn’t have to be one hundred per cent laudatory for it to qualify as good. Quite often I get a review that tells me both what they liked and disliked in my novel. What could be better than that? The reader cared enough about my story to include positive criticism.

Below are some of the more negative comments I’ve received (I won’t reproduce the positive ones because that’s too much like bragging).

“The book was too long.”

“There were too many characters.”

“There was too little (or too much) backstory.”

“There were no strong female characters.”

That last one is the only one I’ll argue with. My stories are full of extremely strong women, and, being a Chauvinist, I must defend them. Some of the ladies are villains. But that shouldn't surprise you. As Kipling reminds us, “. . . the female of the species is more deadly than the male.”

Published on June 25, 2018 06:31

•

Tags:

criticism, reader-reviews, readers, reviews

June 7, 2018

The Boy Soldier Theme

In reply to readers who object to Richard Carter often revisiting the "boy soldier" introduced in Bonne Femme: How could he do otherwise? As Jill points out, "We are the sum total of what happens to us and what we do." Being a decent man, he will forever be visited by that ghost and forever own what he did. It is part of who he is.

Such is one aspect of PTSD. (One size does not fit all.)

As Richard says while attending group sessions, "No one ever goes into combat and comes back unchanged."

He will continue to pay the price for a split second decision. Yet he deals with it. Work and sunlight dampen the dark days. Oddly, his OCD fueled passion is the very mayhem one would think he has to avoid.

He wanted an FBI career, but events shortly after he returned from the Marines have shut that door forever. Instead he has washed ashore in rural Hawthorn County, in the Missouri Ozarks.

His rock and pole star is his wife Jill, a woman who should have wanted nothing to do with him, but who fell in love with him as deeply as he did with her. He doesn't understand how that could have happened.

And then Mirabelle came.

Ever since then, he has been haunted by the thought that fate will surely even the score and take everything away as if it had all been a mistaken delivery because he surely doesn't deserve the blessings that have come his way.

But which of us do?

Published on June 07, 2018 13:46

•

Tags:

character, characters, depression, fate, plot, ptsd, survivor-s-guilt

May 16, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 9

The Hard-Boiled P. I.

SAM SPADE

Watch this space for a completion of these posts.

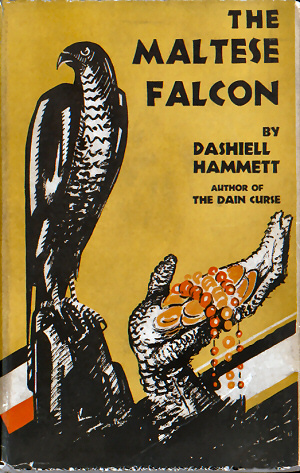

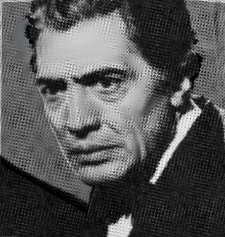

There is no more well-known hard-boiled private detective story than the eponymous 1930 novel by Dashiell Hammett THE MALTESE FALCON. Unfortunately, Sam Spade appears only once in a full-length novel, although he appears in three short stories.

Think of Sam Spade and you probably see and hear the distinctive movie image and voice of Humphrey Bogart. In fact, for me, it's a toss up as to whether Bogart gave Sam Spade a voice or vice versa. To me, Hammett's hard-boiled detective is Bogart.

Sam Spade is a gritty character, living and working in an environment far different from that of the gentlemen and ladies of leisure, those soft-handed but brainy and intrepid amateurs who solve crimes in cozy mysteries.

As Raymond Chandler famously said about Hammett, “[He] helped get murder out of the Vicar’s rose garden, and back to the people who are really good at it.”

Spade is a hard man, living in a world that demands compromises. Their are few choir boys in his world, and the trenchcoated private dick is certainly not one. He is a cold-eyed realist who is not above bending rules and even breaking laws. Yet he is a man with a definite moral compass, albeit one that varies from the conventional in its "true north." At bottom he is a pragmatist who in the end tries to do the right thing even if it costs him (and people with whom he sympathizes) a great deal.

This is illustrated in the Maltese Falcon story which gets its name from the statuette containing a fortune.

SAM SPADE

Watch this space for a completion of these posts.

There is no more well-known hard-boiled private detective story than the eponymous 1930 novel by Dashiell Hammett THE MALTESE FALCON. Unfortunately, Sam Spade appears only once in a full-length novel, although he appears in three short stories.

Think of Sam Spade and you probably see and hear the distinctive movie image and voice of Humphrey Bogart. In fact, for me, it's a toss up as to whether Bogart gave Sam Spade a voice or vice versa. To me, Hammett's hard-boiled detective is Bogart.

Sam Spade is a gritty character, living and working in an environment far different from that of the gentlemen and ladies of leisure, those soft-handed but brainy and intrepid amateurs who solve crimes in cozy mysteries.

As Raymond Chandler famously said about Hammett, “[He] helped get murder out of the Vicar’s rose garden, and back to the people who are really good at it.”

Spade is a hard man, living in a world that demands compromises. Their are few choir boys in his world, and the trenchcoated private dick is certainly not one. He is a cold-eyed realist who is not above bending rules and even breaking laws. Yet he is a man with a definite moral compass, albeit one that varies from the conventional in its "true north." At bottom he is a pragmatist who in the end tries to do the right thing even if it costs him (and people with whom he sympathizes) a great deal.

This is illustrated in the Maltese Falcon story which gets its name from the statuette containing a fortune.

Published on May 16, 2018 09:30

•

Tags:

detectives, genre, mystery, police-procedure

April 24, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 8

HARRIET DEBORAH VANE (LADY WIMSEY)

The Mystery Writer as Sleuth

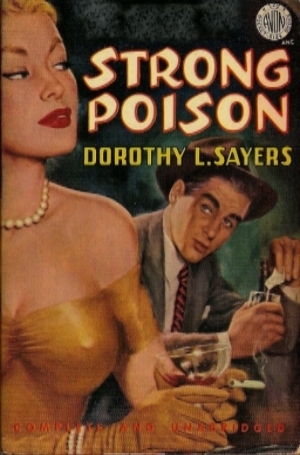

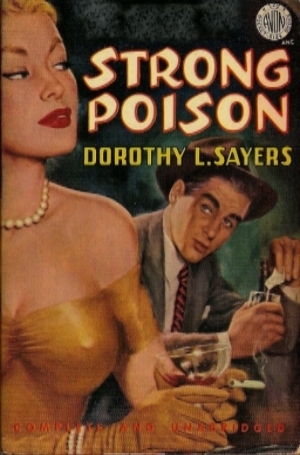

Author Dorothy L Sayers gave us the precursor of TV's Murder She Wrote and Castle: The mystery writer as detective and also “husband and wife investigator team." (remember TV's McMillan And Wife?) Her detective is Harriette Deborah Vane, later Lady Wimsey.

Vane's life as it unfolds in Dorothy Sayers' excellent series is very loosely based on the author's own life.

British writer Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957), created the character Harriet Deborah Vane in the first book of her series (Strong Poison). Mystery writer Vane is on trial for poisoning her lover. Lord Peter Wimsey, the detective on the case (Lord Wimsey) falls in love with Vane, even going so far as to propose to her. Traumatized as she is, she turns him down. In the end, of course, she is vindicated.

In following novels, Vane collaborates with Lord Wimsey. Their first case together is Have His Carcase. At this point, the independent Vane still finds Lord Wimsey overbearing and a bit shallow. She eventually requites his love in Gaudy Night and they marry in Busman's Honeymoon.

So, Dorothy Sayers pioneers two new subgenres: the mystery writer as detective like in TV’s Murder, She Wrote, and the husband and wife as detective partners.

Vane/Lady Wimsey doesn’t give us any new detection tools, but she is an interesting character type: the woman as determiner of her own fate. Remember at the time, women were considered “the weaker vessel” and second-class citizens. A case in point: Sayers herself studied and excelled at Oxford, but, being a female, she was precluded from receiving a degree. However, she was retroactively awarded the degree she had more than earned.

Like Sayers, Vane/Wimsey is strong-willed, intelligent, and at times quite prickly. She is outspoken and not at all prone to playing second fiddle to her husband or any other male.

The Mystery Writer as Sleuth

Author Dorothy L Sayers gave us the precursor of TV's Murder She Wrote and Castle: The mystery writer as detective and also “husband and wife investigator team." (remember TV's McMillan And Wife?) Her detective is Harriette Deborah Vane, later Lady Wimsey.

Vane's life as it unfolds in Dorothy Sayers' excellent series is very loosely based on the author's own life.

British writer Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957), created the character Harriet Deborah Vane in the first book of her series (Strong Poison). Mystery writer Vane is on trial for poisoning her lover. Lord Peter Wimsey, the detective on the case (Lord Wimsey) falls in love with Vane, even going so far as to propose to her. Traumatized as she is, she turns him down. In the end, of course, she is vindicated.

In following novels, Vane collaborates with Lord Wimsey. Their first case together is Have His Carcase. At this point, the independent Vane still finds Lord Wimsey overbearing and a bit shallow. She eventually requites his love in Gaudy Night and they marry in Busman's Honeymoon.

So, Dorothy Sayers pioneers two new subgenres: the mystery writer as detective like in TV’s Murder, She Wrote, and the husband and wife as detective partners.

Vane/Lady Wimsey doesn’t give us any new detection tools, but she is an interesting character type: the woman as determiner of her own fate. Remember at the time, women were considered “the weaker vessel” and second-class citizens. A case in point: Sayers herself studied and excelled at Oxford, but, being a female, she was precluded from receiving a degree. However, she was retroactively awarded the degree she had more than earned.

Like Sayers, Vane/Wimsey is strong-willed, intelligent, and at times quite prickly. She is outspoken and not at all prone to playing second fiddle to her husband or any other male.

Published on April 24, 2018 05:35

•

Tags:

detectives, genre, mystery, police-procedure

April 5, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 7

THE HYPHENATED AMERICAN

A SLEUTH WITH A SENSE OF HUMOR

Say “Charlie Chan” and duck. A brickbat is on the way as soon as you mention Earl Derr Biggers’s Chinese-American detective. Yes, I know about demeaning stereotypes—scratch that and just say “stereotypes.” They are all demeaning. However, please try to judge an author, a book, a character, even a stereotype in the setting of the era to which they belong.

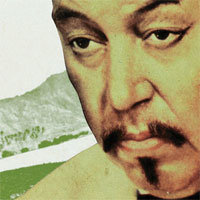

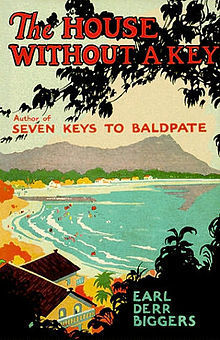

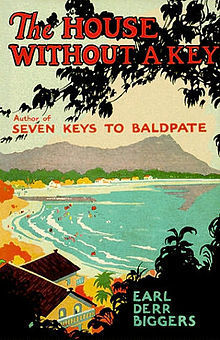

The House Without A Key is an old fashioned murder mystery in which Earl Der Biggers introduces us to both early 20th century Hawaii and the finest detective on the police department, Charlie Chan. In the book, Chan is not the main character, but he plays the pivotal role.

The author also presents the cultural diversity of the island territory. This is a successful launch of career for a detective beloved by readers and much more so by movie goers.

Chan emerges as a non-threatening, amiable, hyphenated American possessed of the supposedly "oriental" traits: stoicism and quiet persistence.

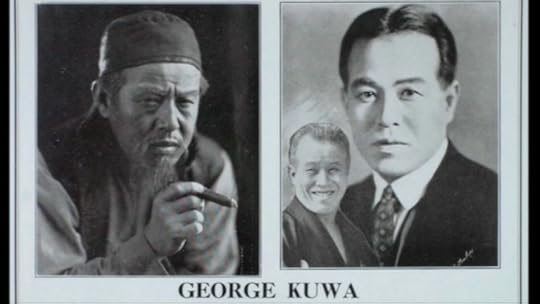

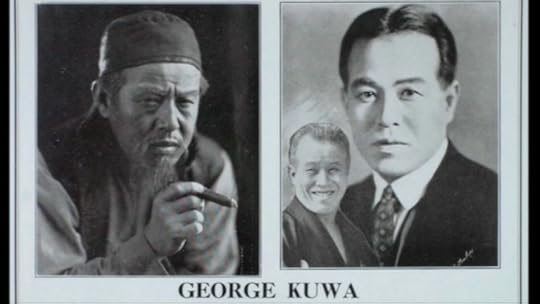

George Kuwa a Japanese-American was the first to portray Chan in movies. The House Without a Key. (1926) pic below

Every new hero needs a hook, something that makes him interestingly unique. Der Biggers gave Chan his ethnicity as an arresting image. At the time, the stereotype of the "Yellow Peril" was widespread in the US (think Fu Manchu).

Charlie Chan was the "benign" half of the stereotype. He was the wily, inscrutable, proverb-uttering Chinaman. His flawed syntactic English was a sop to the genteel bigotry of early 20th century American culture. It made him "acceptable" in the same way as employing the Swedish actor Warner Oland to portray him in most of the movies.

So we have the faux Confucius proverbs spoken to explain his thinking and the eventual undoing of the criminals he brought to justice. Chan was so beloved that virtually all children in the US grew up with a panoply of "Confucius say . . ." one-liners. The thing about "benign" stereotypes is that they are unconscious and not at all intended to offend—yet they did and do.

Still, Der Biggers' Chinese-American sleuth adds something new to the detective genre—humor. Charlie Chan gives us perhaps more humor than any of his predecessors.

He is an engaging man, not at all the "wily Oriental gentleman" of British colonial stereotyping . His charm lies in his use of aphoristic wisdom stated in faux-Confusion sayings. Chan actually is a sort of classic sage.

Sometimes he uses his “proverbs” to reveal what he has deduced and to explain motives, but also uses them to respond to the prejudice that he encounters. He is wise, calm, and as proper as Hercule Poroit. And like Poroit and Father Brown, he deliberately lets people underestimate him.

The House Without a Key

A SLEUTH WITH A SENSE OF HUMOR

Say “Charlie Chan” and duck. A brickbat is on the way as soon as you mention Earl Derr Biggers’s Chinese-American detective. Yes, I know about demeaning stereotypes—scratch that and just say “stereotypes.” They are all demeaning. However, please try to judge an author, a book, a character, even a stereotype in the setting of the era to which they belong.

The House Without A Key is an old fashioned murder mystery in which Earl Der Biggers introduces us to both early 20th century Hawaii and the finest detective on the police department, Charlie Chan. In the book, Chan is not the main character, but he plays the pivotal role.

The author also presents the cultural diversity of the island territory. This is a successful launch of career for a detective beloved by readers and much more so by movie goers.

Chan emerges as a non-threatening, amiable, hyphenated American possessed of the supposedly "oriental" traits: stoicism and quiet persistence.

George Kuwa a Japanese-American was the first to portray Chan in movies. The House Without a Key. (1926) pic below

Every new hero needs a hook, something that makes him interestingly unique. Der Biggers gave Chan his ethnicity as an arresting image. At the time, the stereotype of the "Yellow Peril" was widespread in the US (think Fu Manchu).

Charlie Chan was the "benign" half of the stereotype. He was the wily, inscrutable, proverb-uttering Chinaman. His flawed syntactic English was a sop to the genteel bigotry of early 20th century American culture. It made him "acceptable" in the same way as employing the Swedish actor Warner Oland to portray him in most of the movies.

So we have the faux Confucius proverbs spoken to explain his thinking and the eventual undoing of the criminals he brought to justice. Chan was so beloved that virtually all children in the US grew up with a panoply of "Confucius say . . ." one-liners. The thing about "benign" stereotypes is that they are unconscious and not at all intended to offend—yet they did and do.

Still, Der Biggers' Chinese-American sleuth adds something new to the detective genre—humor. Charlie Chan gives us perhaps more humor than any of his predecessors.

He is an engaging man, not at all the "wily Oriental gentleman" of British colonial stereotyping . His charm lies in his use of aphoristic wisdom stated in faux-Confusion sayings. Chan actually is a sort of classic sage.

Sometimes he uses his “proverbs” to reveal what he has deduced and to explain motives, but also uses them to respond to the prejudice that he encounters. He is wise, calm, and as proper as Hercule Poroit. And like Poroit and Father Brown, he deliberately lets people underestimate him.

The House Without a Key

Published on April 05, 2018 06:13

•

Tags:

detectives, genre, mystery, police-procedure

March 26, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 6

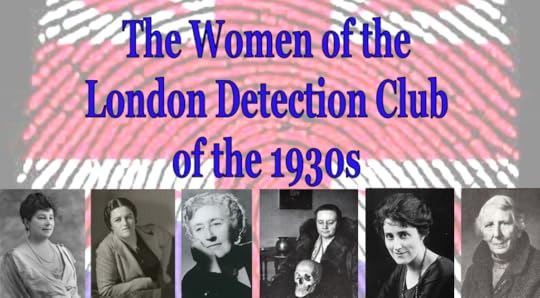

BEATRICE ADELA LESTRANGE BRADLEY, ONE TOUGH WOMAN DETECTIVE

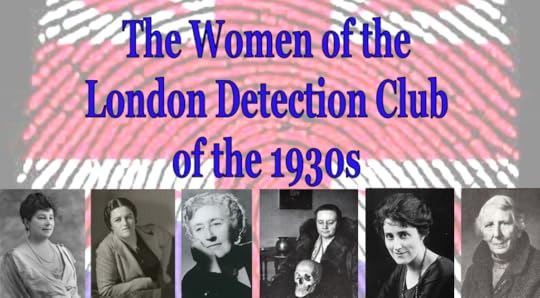

In the 1930s, the golden age of detective stories, Glady Mitchell (seen here) along with GK Chesterson, Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayer formed the “Detection Club.” Chesterson gave us Father Brown. Christie gave us both Hercule Peroit and Mrs. Marple, Sayers gave us Harriet Vane/Lady Wimsey. Mitchel gave us Beatrice Adela Lestrange Bradley (perhaps the first of the "girls-kick-butt" heroines) in a series of 66 novels.

Beatrice Bradley is no shrinking violet, being as physically strong and adept as she is mentally acute. This eccentric detective ranks with the best of literary sleuths of all time.

Eschewing the subservient role most women of her era, she is far from cuddly, indeed described as somewhat cold-blooded. She is gaunt, lean, sinewy, and strong. She is formidable in bearing, and especially so when provoked.

Diana Rigg as Bradley from BBC TV's “Speedy Death”

The Bradley method is the epitome of the omniscient school. She sets her trap and springs it after luring her prey into taking the bait. She is never at a loss, and nothing ever takes her by surprise. It is precisely when the “criminal genius” thinks he has her bested that she springs her trap.

No mere male can surpass or even equal her mentally or physically. She routinely puts them in their places, often addressing them as “child.”

She is charmed: the shot fired at her, like the stone falling or tossed from the roof, might take her by surprise, but it never hits her. The elderly sleuth is light on her feet, stronger than she appears, and a sixth sense warns her when things aren’t quite as they should be.

It is not so much that she is fey as that her subconscious mind warns her of danger in the nick of time.

With her almost super-human power of observation, her vast knowledge of human behavior, and her uncanny ability to see the big picture, no cunning criminal can possibly outdo her.

She is well educated, holding multiple doctorates and is a master of psychiatry and psychology with a deep understanding of human nature. Like Hercule Peroit, she uses "the little grey cells" to solve crimes. In appearance and manner, however, she is the polar opposite of the fastidious Belgian detective. She attacks her cases with intellect and gritty determination, employing her profound understanding of human nature and of forensic science.

As eccentric as Sherlock Holmes, she is, not to put too fine a point on it, a detective of a unique stripe. Bradley is utterly fearless and athletic. Unlike other female sleuths of the day, she is no warm and cuddly woman, not a grandmotherly sort, nor particularly attractive. She is wiry, all gristle and brains, and both physically and mentally strong.

Call her cases cozies, if you will, but don’t for a moment think that there is anything cozy about Beatrice Bradley.

In the 1930s, the golden age of detective stories, Glady Mitchell (seen here) along with GK Chesterson, Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayer formed the “Detection Club.” Chesterson gave us Father Brown. Christie gave us both Hercule Peroit and Mrs. Marple, Sayers gave us Harriet Vane/Lady Wimsey. Mitchel gave us Beatrice Adela Lestrange Bradley (perhaps the first of the "girls-kick-butt" heroines) in a series of 66 novels.

Beatrice Bradley is no shrinking violet, being as physically strong and adept as she is mentally acute. This eccentric detective ranks with the best of literary sleuths of all time.

Eschewing the subservient role most women of her era, she is far from cuddly, indeed described as somewhat cold-blooded. She is gaunt, lean, sinewy, and strong. She is formidable in bearing, and especially so when provoked.

Diana Rigg as Bradley from BBC TV's “Speedy Death”

The Bradley method is the epitome of the omniscient school. She sets her trap and springs it after luring her prey into taking the bait. She is never at a loss, and nothing ever takes her by surprise. It is precisely when the “criminal genius” thinks he has her bested that she springs her trap.

No mere male can surpass or even equal her mentally or physically. She routinely puts them in their places, often addressing them as “child.”

She is charmed: the shot fired at her, like the stone falling or tossed from the roof, might take her by surprise, but it never hits her. The elderly sleuth is light on her feet, stronger than she appears, and a sixth sense warns her when things aren’t quite as they should be.

It is not so much that she is fey as that her subconscious mind warns her of danger in the nick of time.

With her almost super-human power of observation, her vast knowledge of human behavior, and her uncanny ability to see the big picture, no cunning criminal can possibly outdo her.

She is well educated, holding multiple doctorates and is a master of psychiatry and psychology with a deep understanding of human nature. Like Hercule Peroit, she uses "the little grey cells" to solve crimes. In appearance and manner, however, she is the polar opposite of the fastidious Belgian detective. She attacks her cases with intellect and gritty determination, employing her profound understanding of human nature and of forensic science.

As eccentric as Sherlock Holmes, she is, not to put too fine a point on it, a detective of a unique stripe. Bradley is utterly fearless and athletic. Unlike other female sleuths of the day, she is no warm and cuddly woman, not a grandmotherly sort, nor particularly attractive. She is wiry, all gristle and brains, and both physically and mentally strong.

Call her cases cozies, if you will, but don’t for a moment think that there is anything cozy about Beatrice Bradley.

Published on March 26, 2018 09:49

•

Tags:

detectives, genre, mystery, police-procedure, strong-female-character

March 21, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 5

The Armchair Sleuth

We began with gentlemen detectives, the amateur C. August Dupin and the professional “consulting detective” Sherlock Holmes, who was a proto-CSI. Both were men of leisure from the upper class, hankering for intellectual challenge. Then came Father Brown, perhaps the first "psychological investigator." Although neither a man of leisure nor rich, he too was from the upper strata of society as was our fourth detective, the hard-boiled man of action Bulldog Drummond.

Now we turn to a detective who was decidedly not a man of action, the "arm chair sleuth" par excellence. Who does not know the famous Belgian ex-pat:

HERCULE POROIT

A policeman in his native land, he was Chief of Police in Brussels. Forced to flee Belgium for Britain by The Great War, he never returns.

Many of his cases involve members of the high society among whom he moves. He is a globe-trotting investigator, solving murders in Europe, the Middle East, and South America.

He first appears in Agatha Christie’s “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” in 1920.

Christie makes Poirot the antithesis of both the meticulous CSI Holmes and the rough and tumble P.I. Drummond. He does, however, share the psychological approach of Father Brown. Most intriguing to me is Poirot's tendency to keep secrets—both from his associates and clients but also from the reader.

CO-INVESTIGATOR, SIDEKICK, and CONFIDANT

It seems de rigueur for fictional detectives to have sidekicks. Dupin had the narrator, Holmes had Doctor Watson, Father Brown had the reformed criminal Flambeau, and Drummond had a group of war buddies. Poirot has his friend Captain Arthur Hastings who is a confidant a la Holmes’ Watson.

It seems de rigueur for fictional detectives to have sidekicks. Dupin had the narrator, Holmes had Doctor Watson, Father Brown had the reformed criminal Flambeau, and Drummond had a group of war buddies. Poirot has his friend Captain Arthur Hastings who is a confidant a la Holmes’ Watson.

Captain Hastings supplies the muscle when necessary, but he is a good investigator in his own right—although a lesser light than his friend.

Poirot's true foil is the plodding, Lestrade-type Scotland Yard detective, Inspector Japp. (This is formulistic, but if the official investigators were bright and competent, there would be no need for a private sleuth.)

HERCULE POIROT AS DESCRIBED BY CHRISTIE

Poirot is persnickety in dress, manners, and taste. Already in middle age, his attire, tastes, and manners are becoming antiquated. This mental giant is physically small (5’4”) but of noble carriage and great dignity. He has a neat military mustache (of Great War vintage), and is always impeccably dressed. Any untidiness is almost painful to him. The word “prissy” comes to mind.

The dandified detective fights time by dying his hair and refusing to adapt to changing style. Late in his career, his dress is described as hopelessly out of fashion.

Many actors have portrayed him. Perhaps the best movie or TV portrayal of his appearance was Albert Finney’s in the 1974 movie, Murder on the Orient Express.

His habits are a impeccable as his appearance. He wants predictability and order in his life. Poirot is extremely punctual, frequently consulting his old-fashioned pocket watch.

Time zones were necessitated by rail travel, and the “turnip watch” he carries was common for train travelers.

Poirot loves trains and eschews autos, again revealing his clinging attachment to the world that was when he was young.

We love him for it.

THE POIROT METHOD

Modern investigation develops suspects by establishing motive, means, and opportunity, and then finding physical evidence linking them to the crime. The case proceeds through interrogation of the suspects and acquaintances, seeking provable and court-worthy facts to establish guilt.

Sherlock Holmes concentrates on the minutia of physical evidence, following a trail of clues that eventually leads to the discovery of the culprit. Poirot, like Father Brown, focuses on what the clues tell him about the criminal and the victim, anticipating the modern procedure of criminal profiling and victimology developed by the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit. Poroit seeks to discover the murderer-victim dynamic. Of course, the clues are important, because they reveal the relationship between victim and killer. It is almost always an intimate one.

The Belgian detective is no hands-on CSI. In fact, he ridicules detectives who immerse themselves in the fine details of physical evidence. Although he pays careful attention to it, he does so with an eye to WHO would leave such a clue and WHY. He does this by interacting with the people acquainted with the victim. His genius is eliciting information from people when they have no idea they are doing so. He finds blanks and fills them in.

Despite his growing reputation, he is able to make people underestimate him. His appearance, manner, and history aid. He seems the alien, not so much from his ex-pat status as from his being “stuck” in a previous era, in a fast-receding past. He seems the prissy, antiquated odd duck, hopelessly out of touch with the modern world. It is more appearance than fact.

He is also old enough to seem harmless for young women, who tend to confide in him. He is unthreatening physically and often hides his brilliance until it is too late for the over-confident criminal to appreciate. Put these together, and you have Poirot, the “master interrogator.” He knows that when a liar talks at length, he gives himself away, either by revealing a hitherto hidden truth, or by becoming entangled in the details of his lie. As Mark Twain said of the truth: “it’s easier to remember.”

Poirot examines the “what,” “where” and “when” in order to discover the “why” which then reveals the “who.” For him it is all a matter of using “the little gray cells.” In the end, it is often not the clues; it is the guilty themselves that, with Poirot's help, give up the game.

We began with gentlemen detectives, the amateur C. August Dupin and the professional “consulting detective” Sherlock Holmes, who was a proto-CSI. Both were men of leisure from the upper class, hankering for intellectual challenge. Then came Father Brown, perhaps the first "psychological investigator." Although neither a man of leisure nor rich, he too was from the upper strata of society as was our fourth detective, the hard-boiled man of action Bulldog Drummond.

Now we turn to a detective who was decidedly not a man of action, the "arm chair sleuth" par excellence. Who does not know the famous Belgian ex-pat:

HERCULE POROIT

A policeman in his native land, he was Chief of Police in Brussels. Forced to flee Belgium for Britain by The Great War, he never returns.

Many of his cases involve members of the high society among whom he moves. He is a globe-trotting investigator, solving murders in Europe, the Middle East, and South America.

He first appears in Agatha Christie’s “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” in 1920.

Christie makes Poirot the antithesis of both the meticulous CSI Holmes and the rough and tumble P.I. Drummond. He does, however, share the psychological approach of Father Brown. Most intriguing to me is Poirot's tendency to keep secrets—both from his associates and clients but also from the reader.

CO-INVESTIGATOR, SIDEKICK, and CONFIDANT

It seems de rigueur for fictional detectives to have sidekicks. Dupin had the narrator, Holmes had Doctor Watson, Father Brown had the reformed criminal Flambeau, and Drummond had a group of war buddies. Poirot has his friend Captain Arthur Hastings who is a confidant a la Holmes’ Watson.

It seems de rigueur for fictional detectives to have sidekicks. Dupin had the narrator, Holmes had Doctor Watson, Father Brown had the reformed criminal Flambeau, and Drummond had a group of war buddies. Poirot has his friend Captain Arthur Hastings who is a confidant a la Holmes’ Watson.Captain Hastings supplies the muscle when necessary, but he is a good investigator in his own right—although a lesser light than his friend.

Poirot's true foil is the plodding, Lestrade-type Scotland Yard detective, Inspector Japp. (This is formulistic, but if the official investigators were bright and competent, there would be no need for a private sleuth.)

HERCULE POIROT AS DESCRIBED BY CHRISTIE

Poirot is persnickety in dress, manners, and taste. Already in middle age, his attire, tastes, and manners are becoming antiquated. This mental giant is physically small (5’4”) but of noble carriage and great dignity. He has a neat military mustache (of Great War vintage), and is always impeccably dressed. Any untidiness is almost painful to him. The word “prissy” comes to mind.

The dandified detective fights time by dying his hair and refusing to adapt to changing style. Late in his career, his dress is described as hopelessly out of fashion.

Many actors have portrayed him. Perhaps the best movie or TV portrayal of his appearance was Albert Finney’s in the 1974 movie, Murder on the Orient Express.

His habits are a impeccable as his appearance. He wants predictability and order in his life. Poirot is extremely punctual, frequently consulting his old-fashioned pocket watch.

Time zones were necessitated by rail travel, and the “turnip watch” he carries was common for train travelers.

Poirot loves trains and eschews autos, again revealing his clinging attachment to the world that was when he was young.

We love him for it.

THE POIROT METHOD

Modern investigation develops suspects by establishing motive, means, and opportunity, and then finding physical evidence linking them to the crime. The case proceeds through interrogation of the suspects and acquaintances, seeking provable and court-worthy facts to establish guilt.

Sherlock Holmes concentrates on the minutia of physical evidence, following a trail of clues that eventually leads to the discovery of the culprit. Poirot, like Father Brown, focuses on what the clues tell him about the criminal and the victim, anticipating the modern procedure of criminal profiling and victimology developed by the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit. Poroit seeks to discover the murderer-victim dynamic. Of course, the clues are important, because they reveal the relationship between victim and killer. It is almost always an intimate one.

The Belgian detective is no hands-on CSI. In fact, he ridicules detectives who immerse themselves in the fine details of physical evidence. Although he pays careful attention to it, he does so with an eye to WHO would leave such a clue and WHY. He does this by interacting with the people acquainted with the victim. His genius is eliciting information from people when they have no idea they are doing so. He finds blanks and fills them in.

Despite his growing reputation, he is able to make people underestimate him. His appearance, manner, and history aid. He seems the alien, not so much from his ex-pat status as from his being “stuck” in a previous era, in a fast-receding past. He seems the prissy, antiquated odd duck, hopelessly out of touch with the modern world. It is more appearance than fact.

He is also old enough to seem harmless for young women, who tend to confide in him. He is unthreatening physically and often hides his brilliance until it is too late for the over-confident criminal to appreciate. Put these together, and you have Poirot, the “master interrogator.” He knows that when a liar talks at length, he gives himself away, either by revealing a hitherto hidden truth, or by becoming entangled in the details of his lie. As Mark Twain said of the truth: “it’s easier to remember.”

Poirot examines the “what,” “where” and “when” in order to discover the “why” which then reveals the “who.” For him it is all a matter of using “the little gray cells.” In the end, it is often not the clues; it is the guilty themselves that, with Poirot's help, give up the game.

Published on March 21, 2018 04:59

•

Tags:

mystery, nre, police-procedure

March 13, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 4

The Gentleman Adventurer/Detective

(And Proto-"Hard Boiled Sleuth")

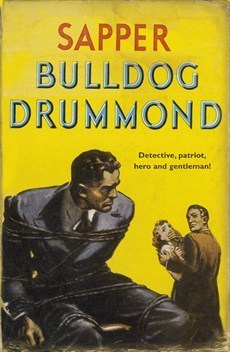

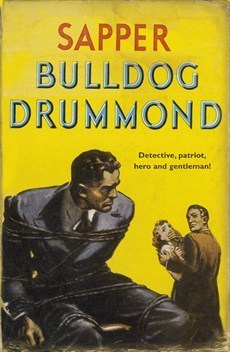

The caption on the cover of this first book says it all: “Detective, patriot, hero, and gentleman.”

The cold-blooded, coolly-calculating, cerebral types are all right, but the post-World War I reading public craves a two-fisted, hot-blooded man with common sense, a man capable of and willing to meet out summary justice and set things right. They need a hero, a man of action.

The Great War is finally over, and the people are ready for a detective who is “all man.” They want a man like Hugh Drummond.

Enter the stage of detective fiction the predecessor of Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and Mike Hammer. This is a man's man who is attractive to (and protective of) the ladies. If that's condescending and chauvinistic, so be it.

"Bulldog" is a type of ideal gentleman, one who is comfortably acquainted with his social inferiors, especially a group of former comrades in arms who aid him in his adventures. He is patriotic, loyal, morally and physically courageous. He is a big, strong, impressive man, but not particularly attractive. Or perhaps he is ruggedly handsome.

Hugh "Bulldog" Drummond is a wealthy gentleman, fresh from the western front where his heroic exploits have equipped him with confidence and the hunter’s skill of stealth. He can really handle himself, being an expert boxer and a crack shot. He can kill quickly, economically, and without a hint of second thought.

PTSD was called “shell-shock” after the Great War, but it was seen as a weakness rather than as an illness. The muddy carnage of trench warfare may have taken the glamour from combat, but it did not lessen respect for the valor of those who contested in it. Drummond was brutalized by the war, but it only tempered his strength. He knows things—has done things that others have not, and that equips him with skills and the demeanor to solve thorny problems and right wrongs. If ever a man was born to cut the Gordian Knot, it is Bulldog Drummond.

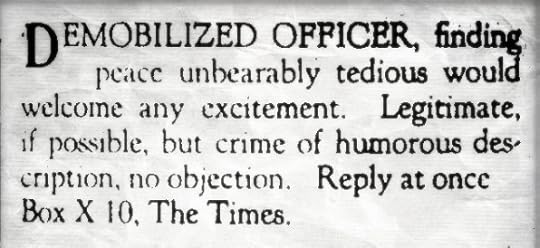

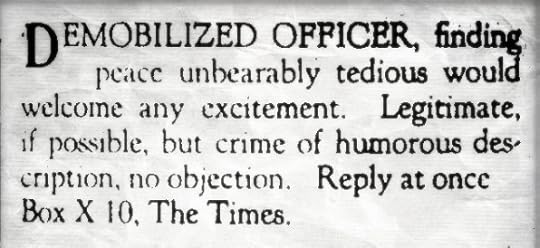

The former officer was intrepid—one might say fool-hardy during the war. (He carried out his own solo sorties in the hellish no-man’s-land between the trenches.) It shouldn't surprise us that he misses the adrenaline rush of combat. He places the following personal in the newspaper.

With that ad, Sapper (H.C. McNeile) introduces Drummond and the “hard-boiled” detective genre.

Sherlock Holmes had Moriarty.

Drummond has Carl Peterson.

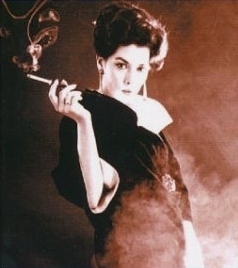

But remember: The female of the species is more deadly than the male. He has a second nemesis: Peterson’s wife, the femme fatale Irma Peterson.

What is this "Gentleman Adventurer"?

And what does "The Bulldog" bring to the genre?

What is his method of investigation?

He is the gentleman-adventurer, a man with the courage of a war hero and the solid common sense of the average man. Sure. He follows clues, tracks down leads, and brings the culprit to justice, albeit Drummond's concept of justice, not necessarily the legal system's. Quite often, he sketches out a plan of action, but "muddles through" (perhaps "ad libs" is a better way to describe it). The one thing Bulldog Drummond is not: he is not frustrated by technicalities. He gets things done, presaging Spillane's "I The Jury."

Bulldog Drummond

(And Proto-"Hard Boiled Sleuth")

The caption on the cover of this first book says it all: “Detective, patriot, hero, and gentleman.”

The cold-blooded, coolly-calculating, cerebral types are all right, but the post-World War I reading public craves a two-fisted, hot-blooded man with common sense, a man capable of and willing to meet out summary justice and set things right. They need a hero, a man of action.

The Great War is finally over, and the people are ready for a detective who is “all man.” They want a man like Hugh Drummond.

Enter the stage of detective fiction the predecessor of Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and Mike Hammer. This is a man's man who is attractive to (and protective of) the ladies. If that's condescending and chauvinistic, so be it.

"Bulldog" is a type of ideal gentleman, one who is comfortably acquainted with his social inferiors, especially a group of former comrades in arms who aid him in his adventures. He is patriotic, loyal, morally and physically courageous. He is a big, strong, impressive man, but not particularly attractive. Or perhaps he is ruggedly handsome.

Hugh "Bulldog" Drummond is a wealthy gentleman, fresh from the western front where his heroic exploits have equipped him with confidence and the hunter’s skill of stealth. He can really handle himself, being an expert boxer and a crack shot. He can kill quickly, economically, and without a hint of second thought.

PTSD was called “shell-shock” after the Great War, but it was seen as a weakness rather than as an illness. The muddy carnage of trench warfare may have taken the glamour from combat, but it did not lessen respect for the valor of those who contested in it. Drummond was brutalized by the war, but it only tempered his strength. He knows things—has done things that others have not, and that equips him with skills and the demeanor to solve thorny problems and right wrongs. If ever a man was born to cut the Gordian Knot, it is Bulldog Drummond.

The former officer was intrepid—one might say fool-hardy during the war. (He carried out his own solo sorties in the hellish no-man’s-land between the trenches.) It shouldn't surprise us that he misses the adrenaline rush of combat. He places the following personal in the newspaper.

With that ad, Sapper (H.C. McNeile) introduces Drummond and the “hard-boiled” detective genre.

Sherlock Holmes had Moriarty.

Drummond has Carl Peterson.

But remember: The female of the species is more deadly than the male. He has a second nemesis: Peterson’s wife, the femme fatale Irma Peterson.

What is this "Gentleman Adventurer"?

And what does "The Bulldog" bring to the genre?

What is his method of investigation?

He is the gentleman-adventurer, a man with the courage of a war hero and the solid common sense of the average man. Sure. He follows clues, tracks down leads, and brings the culprit to justice, albeit Drummond's concept of justice, not necessarily the legal system's. Quite often, he sketches out a plan of action, but "muddles through" (perhaps "ad libs" is a better way to describe it). The one thing Bulldog Drummond is not: he is not frustrated by technicalities. He gets things done, presaging Spillane's "I The Jury."

Bulldog Drummond

Published on March 13, 2018 07:12

•

Tags:

detectives, genre, mystery, police-procedure

March 7, 2018

The Detective Genre, # 3

The "Cleric Detective"

Dupin introduced us to the gentleman detective using keen observation, precise reasoning, and mind-hunting via creative imagination to solve crimes. Sherlock Holmes took observation and single-minded obsession to new heights, ridding himself of emotion to apply cold, sharp logic. He added fingerprint, footprint, trace evidence examination, chemical analysis, and postmortem examination to his toolkit. He was the prototypical CSI.

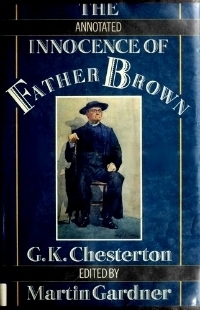

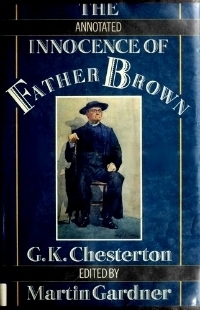

Inevitably, a detective came along who, while logical, employed the less tidy side of his brain, the intuitive faculty. G. K. Chesterton introduced us to Father Brown in “The Blue Cross” (1910). Poe and Conan Doyle gave us the “man of leisure” prototype of detective; Chesterton gave us the “cleric/detective” common in the Cozy Mystery genre. The first compilation of Chesterton’s short stories, “The Innocence of Father Brown,” was published in 1911. Four more compilations followed, the last in 1935.

At first glance, it seems odd that a cloistered “man of the cloth” should immerse himself in ugly mayhem and ungodly crimes. Chesterton, however, asks who is privy to more sins and crimes than a minister? How innocent of ugliness can a man be who occupies the confessional? A priest is not a hermit monk who has withdrawn from the world.

Let’s take a look at Chesterton’s hero. He is a humble man, given to deep thought but few words.

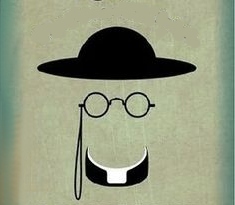

Father Brown’s appearance decidedly does not inspire confidence, much less fear. He is a short, stocky, dough-faced Roman Catholic priest, who wears pince nez glasses, a capello Romano priest’s hat, and rumpled clothes. Always at hand is a large umbrella, even as he rides about the parish on his bicycle. His aspect leads people to underestimate him, a device used later by the slovenly-dressed TV detective, Colombo (portrayed by Peter Falk).

So what does Father Brown bring to the table?

What is his method?

What becomes apparent is that the unassuming priest has a vast knowledge of human nature. He has been exposed to as much evil as any policeman—intimately exposed. His toolkit consists of a keen understanding of people, their foibles, temptations, and failures. The cleric tends to intuition more than deductive reasoning, although he employs both. He observes carefully and applies logic, but he primarily “feels” his way to the solution of the crime.

Dupin and Holmes hint at profiling, but Father Brown is a bona fide “mind-hunter.” He reconstructs the crime in order to get inside the mind of the criminal. In fact, he becomes the murderer (in his mind) and imagines committing the crime. When he gets firmly into the psyche of the criminal, he sees who it is. This is not a fey thing, however, not a séance, nor divine revelation. Father Brown always produces a rational explanation of the crime, and he details the criminal’s motivation.

One final note: don’t think that Father Brown is a man with nothing better to do than gallivant around the parish seeking diversion with juicy murder cases. He is a serious priest, devoted to his church and duties.

The Innocence of Father Brown

Dupin introduced us to the gentleman detective using keen observation, precise reasoning, and mind-hunting via creative imagination to solve crimes. Sherlock Holmes took observation and single-minded obsession to new heights, ridding himself of emotion to apply cold, sharp logic. He added fingerprint, footprint, trace evidence examination, chemical analysis, and postmortem examination to his toolkit. He was the prototypical CSI.

Inevitably, a detective came along who, while logical, employed the less tidy side of his brain, the intuitive faculty. G. K. Chesterton introduced us to Father Brown in “The Blue Cross” (1910). Poe and Conan Doyle gave us the “man of leisure” prototype of detective; Chesterton gave us the “cleric/detective” common in the Cozy Mystery genre. The first compilation of Chesterton’s short stories, “The Innocence of Father Brown,” was published in 1911. Four more compilations followed, the last in 1935.

At first glance, it seems odd that a cloistered “man of the cloth” should immerse himself in ugly mayhem and ungodly crimes. Chesterton, however, asks who is privy to more sins and crimes than a minister? How innocent of ugliness can a man be who occupies the confessional? A priest is not a hermit monk who has withdrawn from the world.

Let’s take a look at Chesterton’s hero. He is a humble man, given to deep thought but few words.

Father Brown’s appearance decidedly does not inspire confidence, much less fear. He is a short, stocky, dough-faced Roman Catholic priest, who wears pince nez glasses, a capello Romano priest’s hat, and rumpled clothes. Always at hand is a large umbrella, even as he rides about the parish on his bicycle. His aspect leads people to underestimate him, a device used later by the slovenly-dressed TV detective, Colombo (portrayed by Peter Falk).

So what does Father Brown bring to the table?

What is his method?

What becomes apparent is that the unassuming priest has a vast knowledge of human nature. He has been exposed to as much evil as any policeman—intimately exposed. His toolkit consists of a keen understanding of people, their foibles, temptations, and failures. The cleric tends to intuition more than deductive reasoning, although he employs both. He observes carefully and applies logic, but he primarily “feels” his way to the solution of the crime.

Dupin and Holmes hint at profiling, but Father Brown is a bona fide “mind-hunter.” He reconstructs the crime in order to get inside the mind of the criminal. In fact, he becomes the murderer (in his mind) and imagines committing the crime. When he gets firmly into the psyche of the criminal, he sees who it is. This is not a fey thing, however, not a séance, nor divine revelation. Father Brown always produces a rational explanation of the crime, and he details the criminal’s motivation.

One final note: don’t think that Father Brown is a man with nothing better to do than gallivant around the parish seeking diversion with juicy murder cases. He is a serious priest, devoted to his church and duties.

The Innocence of Father Brown

Published on March 07, 2018 04:04

•

Tags:

chesterton, cozy, crime, detective-fiction, detectives, father-brown, mystery, profiler

Musings and Mutterings

Posts about my reading, my writing, and thoughts I want to share. Drop in. Hear me out. And set me straight.

- A.R. Simmons's profile

- 59 followers