A.R. Simmons's Blog: Musings and Mutterings, page 3

February 26, 2021

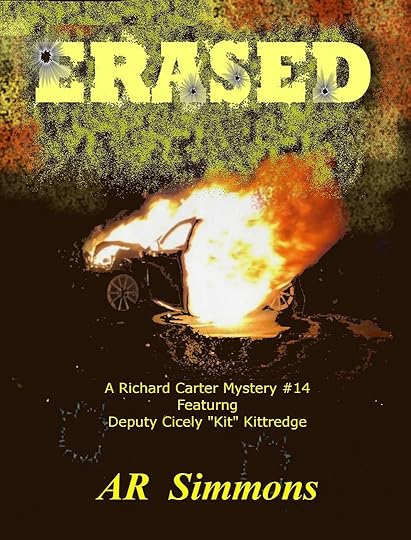

ERASED Chapter Reveal

Chapter-1 April Fool

This is a view from a logging trail in Mark Twain National Forest

east of Blue Creek in Hawthorn County, a typical April scene

in the Missouri Ozarks.

Cicely (Kit) Kittredge is sent on what appears to be a "fool's errand."

ERASED (Richard Carter #14) is coming this summer 2021

These short previews are not spoilers.

This is a view from a logging trail in Mark Twain National Forest

east of Blue Creek in Hawthorn County, a typical April scene

in the Missouri Ozarks.

Cicely (Kit) Kittredge is sent on what appears to be a "fool's errand."

ERASED (Richard Carter #14) is coming this summer 2021

These short previews are not spoilers.

Published on February 26, 2021 07:02

•

Tags:

cozy-detectives, detectives-mystery, sleuths, strong-female

February 21, 2021

Don't Just Read

"A person who won’t read has no advantage over one who can’t read." That quotation is credited to my state's own Mark Twain. "Reading maketh a full man," said Francis Bacon. But unless we read with discrimination, we stand a good chance of being less informed rather than more.

Information-wise, we live in the best of times and the worst of times—the best of times because the world of knowledge is at our fingertips via the Internet. It is the worst of times because any fool can use the world wide web to tell us anything that pops into his mind. The worst misinformation used to be limited to rags like The National Enquirer. Stuff that might as well have been taken from graffiti scrawled on public bathroom walls.

Years ago, at the dawn of the Internet, I taught a class called Methods of Research in which I sent students to various websites with the assignment of determining the reliability of articulate sources both well researched and totally pulled from the netherworld of what came to be QAnon and other specious websites.

When we read stuff that claims to be "things they don't want you to know," we should automatically be skeptical. Also beware of catchphrases and labels like "lame stream media,"

Conspiracy theories abound, but real conspiracies are extremely rare. As my father always told me. "Up to three people can keep a secret . . . as long as two of them are dead.

Whatever you do, weigh the consequences before you repeat or retweet outrageous accusations.

Information-wise, we live in the best of times and the worst of times—the best of times because the world of knowledge is at our fingertips via the Internet. It is the worst of times because any fool can use the world wide web to tell us anything that pops into his mind. The worst misinformation used to be limited to rags like The National Enquirer. Stuff that might as well have been taken from graffiti scrawled on public bathroom walls.

Years ago, at the dawn of the Internet, I taught a class called Methods of Research in which I sent students to various websites with the assignment of determining the reliability of articulate sources both well researched and totally pulled from the netherworld of what came to be QAnon and other specious websites.

When we read stuff that claims to be "things they don't want you to know," we should automatically be skeptical. Also beware of catchphrases and labels like "lame stream media,"

Conspiracy theories abound, but real conspiracies are extremely rare. As my father always told me. "Up to three people can keep a secret . . . as long as two of them are dead.

Whatever you do, weigh the consequences before you repeat or retweet outrageous accusations.

Published on February 21, 2021 04:27

•

Tags:

conspiracy, conspiracy-theory, extremists, gosip, qanon, retweets

February 12, 2021

Possible Cover for New Mystery

Published on February 12, 2021 12:58

•

Tags:

book-cover, cover, cover-art

February 11, 2021

Bonne Femme (Introducing Richard Carter)

Is Richard Carter what he is because of what happened in Somalia or despite of it?

Is Richard Carter what he is because of what happened in Somalia or despite of it?

He may never know if it was something he did, or something that happened to him.

How long must a man wait for confirmation of what he suspects? When is he justified in doing the unthinkable?

A Tale of Terror

Three people. Two former soldiers, each with a mission, each waging a campaign. At the center of their conflict is a vulnerable young woman, alone and far from home.

Richard Carter has come back to Cartier trying to pull his life together, while Jill Belbenoit has come to finish her degree. He has seen her on campus, but doesn’t know her. When a former squadmate from Somalia, Mic Boyd, turns up unexpectedly and assumes a friendship that never was, Richard allows himself to fall into what he hopes will be only a brief association. The last thing he wants is a reminder of his tour in the famine-racked squalor of Africa.

Mic inserts himself into Jill’s life as well as Richard’s. As attractive women must do, she has learned to deal with unwanted male attention. Unable to disengage from one man, however, she obligates herself to the other. Now she must navigate out of both relationships. Jill reproaches herself for both her naiveté and her manipulativeness. Soon she will have much greater concerns.

Memories, dreams, and flashbacks torment Richard as he tries to discover if what he fears is real, while Jill must decide if he is only a damaged soldier suffering from PTSD, or dangerously delusional and obsessed with her.

Is his nightmare vision the product of a fevered imagination tortured by his war experience and his guilt? Or does he see what no one else can? Is he averting a horror or perpetrating one?

Where does Jill’s real danger lie? Can she trust him? Is the “godforsaken pile of rocks” called Bonne Femme a refuge from peril—or from reality?

February 9, 2021

I Survived Coal Oil

Coal oil (kerosene) lit our great grandparents’ nights, and it fuels today’s jets. When I was a child it was also a miracle drug. Folks washed wounds with it and even took it internally—a good way to poison yourself!

Maybe its popularity came from the idea that the more evil-smelling and disgusting stuff was the better it was for you (think cod liver oil and creosote cough medicine). Rich people used to travel to spas like Eureka Springs to drink and soak in water that smelled like rotten eggs and tasted awful.

Despite its relatively mild aroma, coal oil’s curative powers were highly esteemed. There were other home remedies : tobacco juice relieved the welts of “wasper” stings, and lard poultices pulled poison from cuts and gashes. Coal oil was an antiseptic/healing balm.

My first encounter with the miracle cure came when I was four. Back then we boys went shoeless whenever temperatures permitted. They tell me that I literally ran wild, stubbing my toes on rocks, cutting my feet on broken glass, running thorns that had fallen from blue jays’ nests into my soles, and stepping on rusty nails.

One fall day, as I tore across the yard like a hellion, I ran through a gray mound of innocent-looking ashes. It contained live coals from a hog butchering the previous day. For those who don’t know where our food comes from, you can’t skin hogs. You scald them in a kettle of boiling water and scrape the hair off like shaving.

After my ill-advised shortcut through the bed of hot coals, my feet looked like I had a severe sunburn. I don’t remember any pain, but I vividly remember the smell when they soaked my feet in a tin bowl of coal oil.

I doubt the treatment did any good, but my elders were satisfied that they had applied the latest medicine.

“Hospital,” you say? No. Hospitals were where babies were born and where people went to die.

Coal oil was “snake oil.” But there is a petroleum product recommended by dermatologists to facilitate the healing of minor wounds: Petroleum jelly (Vaseline). Mine recommends it instead of antibiotic creams.

Maybe its popularity came from the idea that the more evil-smelling and disgusting stuff was the better it was for you (think cod liver oil and creosote cough medicine). Rich people used to travel to spas like Eureka Springs to drink and soak in water that smelled like rotten eggs and tasted awful.

Despite its relatively mild aroma, coal oil’s curative powers were highly esteemed. There were other home remedies : tobacco juice relieved the welts of “wasper” stings, and lard poultices pulled poison from cuts and gashes. Coal oil was an antiseptic/healing balm.

My first encounter with the miracle cure came when I was four. Back then we boys went shoeless whenever temperatures permitted. They tell me that I literally ran wild, stubbing my toes on rocks, cutting my feet on broken glass, running thorns that had fallen from blue jays’ nests into my soles, and stepping on rusty nails.

One fall day, as I tore across the yard like a hellion, I ran through a gray mound of innocent-looking ashes. It contained live coals from a hog butchering the previous day. For those who don’t know where our food comes from, you can’t skin hogs. You scald them in a kettle of boiling water and scrape the hair off like shaving.

After my ill-advised shortcut through the bed of hot coals, my feet looked like I had a severe sunburn. I don’t remember any pain, but I vividly remember the smell when they soaked my feet in a tin bowl of coal oil.

I doubt the treatment did any good, but my elders were satisfied that they had applied the latest medicine.

“Hospital,” you say? No. Hospitals were where babies were born and where people went to die.

Coal oil was “snake oil.” But there is a petroleum product recommended by dermatologists to facilitate the healing of minor wounds: Petroleum jelly (Vaseline). Mine recommends it instead of antibiotic creams.

Published on February 09, 2021 07:52

•

Tags:

childhood, folk-remedy, kerosene, lore, medicine, ozark-culture, snake-oil

February 5, 2021

A Simple Pleasure

This Ozark boy spent a lot of time in the barn.

As a boy I was outside during the daylight and twilight hours. In the winter, my cousin Jerry and I spent many sun-warmed, but wind-cooled days in the loft of Uncle Benton’s barn. The loft was floored with rough-cut oak boards, and overlaid with loose hay, most of which was gone by the time winter was grudgingly gave way to spring.

There was danger and treasure in the loft, the danger coming from gaps in the plank floor we occasionally fell most of the way through, catching ourselves at the last minute to the great amusement of the other. The real danger came from nails in the joists upon which hung drying and obsolete horse tack.

The treasure consisted of “apple johns,” winter-stored apples. Uncle Benton had two Jonathan apple trees that produced an abundance of tartly sweet apples which I loved. He always stored a few bushels of them in the loft covered with hay to prevent freezing. By spring they were wrinkly and shriveled, a bit spongy, but still sweet. Aunt Zelma used them for pies—the ones that survived the appetites of us boys.

I remember sitting with feet dangling out the loft door and munching on late winter apples seasoned with the rock salt that Uncle Benton kept in the barn to feed to his cows.

A person is rich indeed if he can appreciate such simple pleasures. And he doesn't need to be a country boy or boy.

Carpe diem.

As a boy I was outside during the daylight and twilight hours. In the winter, my cousin Jerry and I spent many sun-warmed, but wind-cooled days in the loft of Uncle Benton’s barn. The loft was floored with rough-cut oak boards, and overlaid with loose hay, most of which was gone by the time winter was grudgingly gave way to spring.

There was danger and treasure in the loft, the danger coming from gaps in the plank floor we occasionally fell most of the way through, catching ourselves at the last minute to the great amusement of the other. The real danger came from nails in the joists upon which hung drying and obsolete horse tack.

The treasure consisted of “apple johns,” winter-stored apples. Uncle Benton had two Jonathan apple trees that produced an abundance of tartly sweet apples which I loved. He always stored a few bushels of them in the loft covered with hay to prevent freezing. By spring they were wrinkly and shriveled, a bit spongy, but still sweet. Aunt Zelma used them for pies—the ones that survived the appetites of us boys.

I remember sitting with feet dangling out the loft door and munching on late winter apples seasoned with the rock salt that Uncle Benton kept in the barn to feed to his cows.

A person is rich indeed if he can appreciate such simple pleasures. And he doesn't need to be a country boy or boy.

Carpe diem.

Published on February 05, 2021 09:25

•

Tags:

childhood, country-life, memories, philosophy, simple-pleasures

February 1, 2021

Ozark Xenophobia

(Xenophobia: fear of the stranger, the foreigner, or the outsider)

This Ozark Boy did a shameful thing, He grew by the knowledge of what he did.

One of my classmates at Twin Springs (my rural one-room school) lost his pocketknife. He claimed that it had been stolen, and his suspicion came to rest upon a boy who had recently enrolled. It took almost no persuading for all of us to “know” that the new boy was the thief. After all, we didn’t know him, and he spoke with what we considered a city accent. We weren’t intending him physical harm, but the truth is that we had become a sort of juvenile “lynch mob.”

We took our accusations to Mr. Inman, a man I consider to be one of the two best teachers I was privileged to have. He listened. Then he calmly, but firmly, told us what a great injustice we were committing. “Accusing someone of being a thief when you have no proof is wrong and mean,” he said. “I don’t want to hear that again.”

I don’t know what happened to that knife, but that boy (whose name I can’t remember) almost certainly didn’t steal it. It was more than likely just lost. To this day, I see our schoolboy actions as emblematic of all-too-inclined-to-evil human nature. I hope that boy never discovered what we did. I still feel shame for my part in it. And now I know this: what we were doing was a lot worse than swiping a knife.

Mr. Inman taught me that.

This Ozark Boy did a shameful thing, He grew by the knowledge of what he did.

One of my classmates at Twin Springs (my rural one-room school) lost his pocketknife. He claimed that it had been stolen, and his suspicion came to rest upon a boy who had recently enrolled. It took almost no persuading for all of us to “know” that the new boy was the thief. After all, we didn’t know him, and he spoke with what we considered a city accent. We weren’t intending him physical harm, but the truth is that we had become a sort of juvenile “lynch mob.”

We took our accusations to Mr. Inman, a man I consider to be one of the two best teachers I was privileged to have. He listened. Then he calmly, but firmly, told us what a great injustice we were committing. “Accusing someone of being a thief when you have no proof is wrong and mean,” he said. “I don’t want to hear that again.”

I don’t know what happened to that knife, but that boy (whose name I can’t remember) almost certainly didn’t steal it. It was more than likely just lost. To this day, I see our schoolboy actions as emblematic of all-too-inclined-to-evil human nature. I hope that boy never discovered what we did. I still feel shame for my part in it. And now I know this: what we were doing was a lot worse than swiping a knife.

Mr. Inman taught me that.

Published on February 01, 2021 03:40

•

Tags:

culture, false-accusation, growing-up, lesson, lynch-mob, ozarks, prejudice, teacher, the-other

December 28, 2020

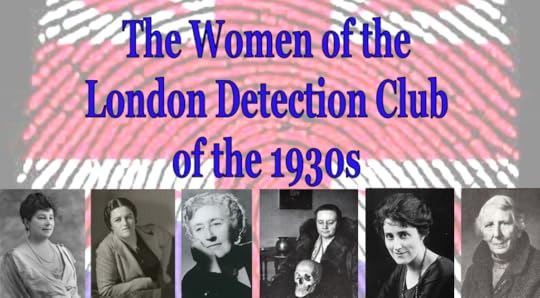

Legendary Detectives, BeatriceBradley

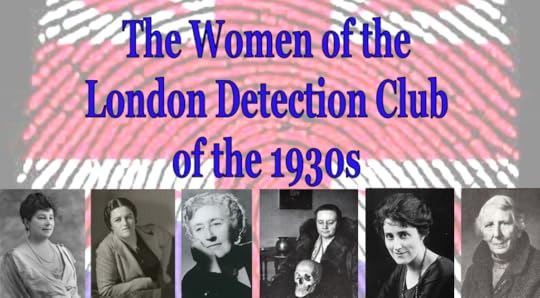

[Pic Gladys Mitchell]

In the 1930s, a golden age of detective stories, Glady Mitchell along with GK Chesterson, Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayer formed the “Detection Club.” Chesterson gave us Father Brown. Christie gave us both Hercule Peroit and Mrs. Marple, Sayers gave us Harriet Vane/Lady Wimsey. Mitchel gave us Beatrice Adela Lestrange Bradley, perhaps the first of the girls-kick-butts heroines through 66 novels.

[PIC Detection Club]

Beatrice Bradley is no shrinking violet, being as physically strong and adept as she is mentally. This eccentric detective ranks with the best of literary sleuths of all time.

Eschewing the subservient role most women of her era, she is far from cuddly, indeed described as somewhat cold-blooded. She is gaunt, lean, sinewy, and strong. She is formidable in bearing, and especially so when provoked.

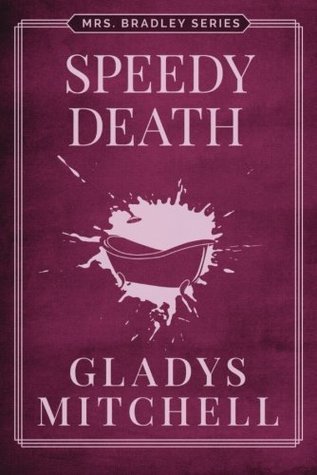

[Here Pic of Diana Rigg as Bradley from BBC TV “Speedy Death”]

Her method is the epitome of the omniscient school. She lays her trap with precise location and timing and then coaxes her hapless prey into taking the bait. She is never at a loss, and nothing ever takes her by surprise. It is precisely when the “criminal genius” thinks he has her bested that she springs her trap.

No mere male can best or even equal her mentally or physically. She routinely puts them in their places by addressing them with the term “child.”

She is somewhat charmed: the shot fired at her, like the stone falling or tossed from the parapet, may take her by surprise, but never hits her. The elderly sleuth is light on her feet, stronger than she appears, and is possessed of a sixth sense that warns her when things aren’t quite as they should be. It is not so much that she is fey as that her subconscious mind warns her of danger in the nick of time. With her almost super-human power of observation, her vast knowledge of human behavior, and her uncanny ability to see the big picture, no mere genius can possibly outdo her.

She is well and appropriately educated, holding multiple doctorates and is an expert or master of psychiatry and psychology giving her an unequaled understanding of human nature. Like Hercule Peroit, she uses the little grey cells to solve crimes. In appearance and manner, however, she is the polar opposite of the persnickety Belgian detective. With a combination of intellect, grit, and single-minded determination, she attacks her cases, coming at them with a profound understanding of human nature and forensic science.

In eccentricity, she is a match for Sherlock Holmes. She was in her day, to put it mildly, a detective of a different sort. Utterly fearless and much more agile and strong that she appears. She is not a warm and cuddly woman, not a grandmotherly sort, nor the timid soul such as other famous female sleuths of the day. Not attractive, but wiry, all gristle and brains.

Call her cases, cozies, but don’t for a minute think that she is.

[Speedy Death]

[Come Away Death]

In the 1930s, a golden age of detective stories, Glady Mitchell along with GK Chesterson, Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayer formed the “Detection Club.” Chesterson gave us Father Brown. Christie gave us both Hercule Peroit and Mrs. Marple, Sayers gave us Harriet Vane/Lady Wimsey. Mitchel gave us Beatrice Adela Lestrange Bradley, perhaps the first of the girls-kick-butts heroines through 66 novels.

[PIC Detection Club]

Beatrice Bradley is no shrinking violet, being as physically strong and adept as she is mentally. This eccentric detective ranks with the best of literary sleuths of all time.

Eschewing the subservient role most women of her era, she is far from cuddly, indeed described as somewhat cold-blooded. She is gaunt, lean, sinewy, and strong. She is formidable in bearing, and especially so when provoked.

[Here Pic of Diana Rigg as Bradley from BBC TV “Speedy Death”]

Her method is the epitome of the omniscient school. She lays her trap with precise location and timing and then coaxes her hapless prey into taking the bait. She is never at a loss, and nothing ever takes her by surprise. It is precisely when the “criminal genius” thinks he has her bested that she springs her trap.

No mere male can best or even equal her mentally or physically. She routinely puts them in their places by addressing them with the term “child.”

She is somewhat charmed: the shot fired at her, like the stone falling or tossed from the parapet, may take her by surprise, but never hits her. The elderly sleuth is light on her feet, stronger than she appears, and is possessed of a sixth sense that warns her when things aren’t quite as they should be. It is not so much that she is fey as that her subconscious mind warns her of danger in the nick of time. With her almost super-human power of observation, her vast knowledge of human behavior, and her uncanny ability to see the big picture, no mere genius can possibly outdo her.

She is well and appropriately educated, holding multiple doctorates and is an expert or master of psychiatry and psychology giving her an unequaled understanding of human nature. Like Hercule Peroit, she uses the little grey cells to solve crimes. In appearance and manner, however, she is the polar opposite of the persnickety Belgian detective. With a combination of intellect, grit, and single-minded determination, she attacks her cases, coming at them with a profound understanding of human nature and forensic science.

In eccentricity, she is a match for Sherlock Holmes. She was in her day, to put it mildly, a detective of a different sort. Utterly fearless and much more agile and strong that she appears. She is not a warm and cuddly woman, not a grandmotherly sort, nor the timid soul such as other famous female sleuths of the day. Not attractive, but wiry, all gristle and brains.

Call her cases, cozies, but don’t for a minute think that she is.

[Speedy Death]

[Come Away Death]

Published on December 28, 2020 08:23

•

Tags:

cozy-detectives, detectives-mystery, sleuths

December 16, 2020

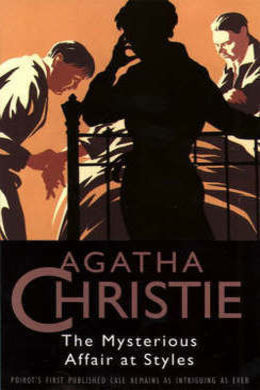

Legendary Detectives, Hercule Poirot

We began with gentlemen detectives, the amateur C. August Dupin and the professional “consulting detective” Sherlock Holmes, who was a proto-CSI. Both were men of leisure from the upper class, hankering for intellectual challenge. Then came Father Brown, perhaps the first "psychological investigator." Although neither a man of leisure nor rich, he too was from the upper strata of society as was our fourth detective, the hard-boiled man of action Bulldog Drummond.

Now we turn to a detective who was decidedly not a man of action, the "arm chair sleuth" par excellence. Who does not know the famous Belgian ex-pat, Hercule Poirot?

A policeman in his native land, he was Chief of Police in Brussels. Forced to flee Belgium for Britain by The Great War, he never returns.

Many of his cases involve members of the high society among whom he moves. He is a globe-trotting investigator, solving murders in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and South America.

He first appears in Agatha Christie’s “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” in 1920.

Christie makes Poirot the antithesis of both the meticulous CSI Holmes and the rough and tumble P.I. Drummond. He does, however, share the psychological approach of Father Brown. Most intriguing to me is Poirot's tendency to keep secrets—both from his associates and clients and from the reader.

CO-INVESTIGATOR, SIDEKICK, and CONFIDANT

It seems de rigueur for fictional detectives to have sidekicks. Dupin had the narrator, Holmes had Doctor Watson, Father Brown had the reformed criminal Flambeau, and Drummond had a group of war buddies. Poirot has his friend Captain Arthur Hastings who is a confidant a la Holmes’ Watson.

It seems de rigueur for fictional detectives to have sidekicks. Dupin had the narrator, Holmes had Doctor Watson, Father Brown had the reformed criminal Flambeau, and Drummond had a group of war buddies. Poirot has his friend Captain Arthur Hastings who is a confidant a la Holmes’ Watson.Captain Hastings supplies the muscle when necessary, but he is a good investigator in his own right—although a lesser light than his friend.

Poirot's true foil is the plodding, Lestrade-type Scotland Yard detective, Inspector Japp. (This is formulistic, but if the official investigators were bright and competent, there would be no need for a private sleuth.)

HERCULE POIROT AS DESCRIBED BY CHRISTIE

Poirot is persnickety in dress, manners, and taste. Already in middle age, his attire, tastes, and manners are becoming antiquated. This mental giant is physically small (5’4”) but of noble carriage and great dignity. He has a neat military mustache (of Great War vintage), and is always impeccably dressed. Any untidiness is almost painful to him. The word “prissy” comes to mind.

The dandified detective fights time by dying his hair and refusing to adapt to changing style. Late in his career, his dress is described as hopelessly out of fashion.

Many actors have portrayed him. Perhaps the best movie or TV portrayal of his appearance was Albert Finney’s in the 1974 movie, Murder on the Orient Express.

His habits are as impeccable as his appearance. He wants predictability and order in his life. Poirot is extremely punctual, frequently consulting his old-fashioned pocket watch.

Time zones were necessitated by rail travel, and the “turnip watch” he carries was common for train travelers.

Poirot loves trains and eschews autos, again revealing his clinging attachment to the world that was when he was young.

We love him for it.

THE POIROT METHOD

The Belgian detective is no hands-on CSI. In fact, he ridicules detectives (like Holmes) who dive into the fine details of physical evidence. He pays careful attention to them, but does so with an eye to WHO would leave such clues and WHY.

Modern investigators develop suspects by establishing motive, means, and opportunity, and then finding physical evidence linking suspect to crime. Interrogating suspects and acquaintances of the victim, they seek court-worthy facts to prove guilt.

Poirot follows a similar process. But he develops his suspects by letting the clues from the crime scene tell him about the killer and the victim, anticipating the procedure of criminal profiling developed by the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit. He examines the murderer-victim dynamic, trying to understand the intimate relationship leading to homicide.

Despite his growing reputation, Poirot is able to make people underestimate him by his appearance, manner, and history. He seems the alien, not so much from his ex-pat status as from his being “stuck” in a previous era. He seems prissy, antiquated—an odd duck, hopelessly out of touch with the modern world.

It is more appearance than fact. He is a genius at eliciting information when people have no idea they are giving it.

He is also old enough to seem harmless. Physically unthreatening, he often hides his brilliance until it is too late for the over-confident criminal to appreciate.

He is also old enough to seem harmless. Physically unthreatening, he often hides his brilliance until it is too late for the over-confident criminal to appreciate. Poirot is the “master interrogator.” He knows that when a liar talks at length, he often gives himself away, either by revealing a hitherto hidden truth, or by becoming entangled in the details of his lie. As Mark Twain said of the truth: “it’s easier to remember.”

Poirot examines the “what,” “where” and “when” to discover the “why” which reveals the “who.” It is a matter of using “the little gray cells” to orchestrate the revelation of the solution to the mystery.

In the end, it is not the clues, but the guilty temselves that (with Poirot's help) give up the game.

Published on December 16, 2020 03:07

•

Tags:

cozy-detectives, detectives-mystery, sleuths

December 12, 2020

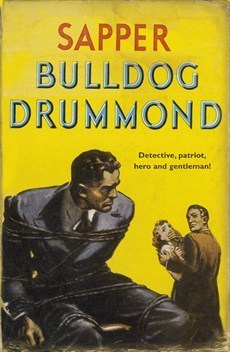

Legendary Detectives, Bulldog Drummond

The caption on the cover of the first book says it all: “Detective, patriot, hero, and gentleman.”

The caption on the cover of the first book says it all: “Detective, patriot, hero, and gentleman.”

The cold-blooded, coolly-calculating, cerebral types are all right, but the reading public craves a two-fisted, hot-blooded man with common sense, a man capable of and willing to meet out summary justice and set things right.

The Great War is finally over, and the people are ready for a detective who is “all man.” They want a man like Bulldog Drummond.

He is a type of ideal gentleman, one who is comfortably acquainted with his social inferiors, especially a group of former comrades in arms who aid him in his adventures. He is patriotic, loyal, morally and physically courageous. He is a big, impressive, but not particularly attractive, man.

Hugh Drummond is a wealthy gentleman, formerly an office on the western front. His wartime exploits have equipped him with confidence and the hunter’s skill of stealth. He is also an expert boxer and a crack shot, and can handle himself in any physical confrontation. He can kill quickly, economically, and without a second thought.

PTSD was called “shell-shock” after the Great War, but it was seen as a weakness rather than as an illness. The muddy carnage of trench warfare may have taken the glamour from combat, but it did not detract from the valor of the men who contested in it. Drummond may have been brutalized by the war, but it only made him stronger. He knew things—had done things that others had not, and it equipped him with the skills and demeanor to solve problems and right wrongs. If ever a man was born to cut the Gordian Knot, it was Hugh “Bulldog” Drummond.

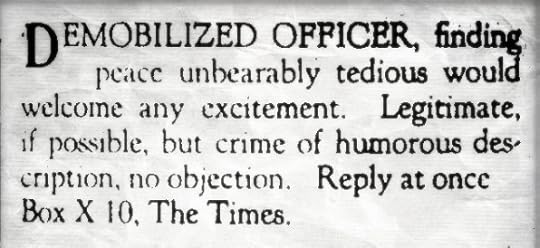

In the general disillusionment following the First World War, there was a great appeal among readers (and movie goers) for a character like Hugh Drummond. He was a gentleman adventurer with the courage of a war hero and the solid common sense of the average man. The former officer had carried out his own solo sorties in the hellish no-man’s-land between the trenches. When he came back to civilian life, and found it boring. He advertises in the newspaper that he is looking for adventure—and soon finds it.

With that ad, Sapper (H.C. McNeile) introduces Drummond and the “hard-boiled” detective genre.

Sherlock Holmes had his Moriarty, and Drummond has his nemesis, Carl Peterson. He also has a second nemesis, Peterson’s wife, the femme fatale Irma Peterson.

Published on December 12, 2020 03:49

•

Tags:

detectives-mystery, hard-boiled-detectives, sleuths

Musings and Mutterings

Posts about my reading, my writing, and thoughts I want to share. Drop in. Hear me out. And set me straight.

- A.R. Simmons's profile

- 59 followers