A.R. Simmons's Blog: Musings and Mutterings, page 11

April 28, 2016

Writing Rx and Overdose (3)

“. . . tips are like aspirin. One may do you good, but if you swallow the whole bottle you will be lucky to survive.”

—Harvey Pennick, Harvey Pennick’s Little Red Book

“Free writing advice is appropriately priced.”

We’ve been cautioning about overdosing on some widely-accepted writing rules (see back pages).

Keeping in mind that all medicines are potential poisons, please take writing advice (including mine) as you would medicine—only as needed.

.................RULE 7 NEVER OPEN A BOOK WITH WEATHER................

This opening line of Edward Bulwer-Lytton 1830 novel Paul Clifford is often used as an example of florid writing. It does tell us something of the setting and sets the mood. The rest of the passage goes on in detail with asides and becomes an overly long example of “purple prose.”

The purpose of the rule is to cut to the chase and immerse the reader immediately in the “human” story:

“Call me Ishmael,” begins Hermann Melville’s main character as he speaks directly to us, setting out with a world of allusions. He, and we, are the outcasts who have been deprived of our birthright and must go into the world to seek our heritage with a lesser blessing.

So there are the best and the worst (according to some). The problem I have with the rule is the word “never.” Can we say, “Never use ‘never’ in a rule”? The opening line below illustrates why we cannot.

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

—George Orwell, 1984

.................RULE 8 AVOID FLASHBACKS................

Some say that flashbacks “lose the reader.” They say the reader needs simple linear plots. Such an approach underestimates him. Readers are smart and experienced.

A good flashback gives him vital information that bears on, but does not occur within the present narrative. It is a “hook” to transport him to the “beginning” of the story. (As a writer, you are in the business of transportation.)

A good flashback gives him vital information that bears on, but does not occur within the present narrative. It is a “hook” to transport him to the “beginning” of the story. (As a writer, you are in the business of transportation.)The flashback is a valuable tool in competent hands. If you have the skill to use it, then keep it in your kit. If you don’t, learn it. Its use requires skill. (Doesn't all writing?) It either works or doesn’t based on execution.

You may not use this tool often, but keep it in your toolkit.

.................RULE 9 AVOID PROLOGUES................

This is an Rx for an imaginary malady. Don't title it "Prologue." Use a descriptive word of phrase, and then get on with it.

"What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet."

The rationale behind this rule is that anything worth being in the story should be part of the story proper. Guess what? It is.

Everything stated about flashbacks applies to prologues.

A prologue can set the mood, define a character, or let the reader in on something the main character does not know. It can do any number of things to enhance the story. Perhaps best, it limits narration by a vignette that “shows rather than tells.”

These three rules have to do with story telling rather than the nuts and bolts of grammar and exposition. Just remember that story telling is an art. It is creative, and no one can teach creativity by the numbers.

Pack your tool kit, and refine your skills. Don’t limit your options just because a famous author says a tool is worthless. Write like you, not like him or her.

Don't get me wrong. If they are famous and successful, they have paid their dues. That doesn’t make them the arbiter of style. Listen to what they say carefully because they know a thing or two, but don’t take what they say as gospel. People almost always overstate and simplify rules to drive home a point. Just remember what Harvey Pennick says about dosage.

April 26, 2016

Legendary Detectives: Hercule Poirot

We began with gentlemen detectives, the amateur C. August Dupin and the professional “consulting detective” Sherlock Holmes, who was a proto-CSI. Both were men of leisure from the upper class, hankering for intellectual challenge. Then came Father Brown, perhaps the first "psychological investigator." Although neither a man of leisure nor rich, he too was from the upper strata of society as was our fourth detective, the hard-boiled man of action Bulldog Drummond.

Now we turn to a detective who was decidedly not a man of action, the "arm chair sleuth" par excellence. Who does not know the famous Belgian ex-pat, Hercule Poirot?

A policeman in his native land, he was Chief of Police in Brussels. Forced to flee Belgium for Britain by The Great War, he never returns.

Many of his cases involve members of the high society among whom he moves. He is a globe-trotting investigator, solving murders in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and South America.

He first appears in Agatha Christie’s “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” in 1920.

Christie makes Poirot the antithesis of both the meticulous CSI Holmes and the rough and tumble P.I. Drummond. He does, however, share the psychological approach of Father Brown. Most intriguing to me is Poirot's tendency to keep secrets—both from his associates and clients and from the reader.

CO-INVESTIGATOR, SIDEKICK, and CONFIDANT

It seems de rigueur for fictional detectives to have sidekicks. Dupin had the narrator, Holmes had Doctor Watson, Father Brown had the reformed criminal Flambeau, and Drummond had a group of war buddies. Poirot has his friend Captain Arthur Hastings who is a confidant a la Holmes’ Watson.

It seems de rigueur for fictional detectives to have sidekicks. Dupin had the narrator, Holmes had Doctor Watson, Father Brown had the reformed criminal Flambeau, and Drummond had a group of war buddies. Poirot has his friend Captain Arthur Hastings who is a confidant a la Holmes’ Watson.Captain Hastings supplies the muscle when necessary, but he is a good investigator in his own right—although a lesser light than his friend.

Poirot's true foil is the plodding, Lestrade-type Scotland Yard detective, Inspector Japp. (This is formulistic, but if the official investigators were bright and competent, there would be no need for a private sleuth.)

HERCULE POIROT AS DESCRIBED BY CHRISTIE

Poirot is persnickety in dress, manners, and taste. Already in middle age, his attire, tastes, and manners are becoming antiquated. This mental giant is physically small (5’4”) but of noble carriage and great dignity. He has a neat military mustache (of Great War vintage), and is always impeccably dressed. Any untidiness is almost painful to him.

The dandified detective fights time by dying his hair and refusing to adapt to changing style. Late in his career, his dress is described as hopelessly out of fashion.

Many actors have portrayed him. Perhaps the best movie or TV portrayal of his appearance was Albert Finney’s in the 1974 movie, Murder on the Orient Express.

His habits are as impeccable as his appearance. He wants predictability and order in his life. Poirot is extremely punctual, frequently consulting his old-fashioned pocket watch.

Time zones were necessitated by rail travel, and the “turnip watch” he carries was common for train travelers.

Poirot loves trains and eschews autos, again revealing his clinging attachment to the world that was when he was young.

We love him for it.

THE POIROT METHOD

The Belgian detective is no hands-on CSI. In fact, he ridicules detectives (like Holmes) who dive into the fine details of physical evidence. He pays careful attention to them, but does so with an eye to WHO would leave such clues and WHY.

Modern investigators develop suspects by establishing motive, means, and opportunity, and then finding physical evidence linking suspect to crime. Interrogating suspects and acquaintances of the victim, they seek court-worthy facts to prove guilt.

Poirot follows a similar process. But he develops his suspects by letting the clues from the crime scene tell him about the killer and the victim, anticipating the procedure of criminal profiling developed by the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit. He examines the murderer-victim dynamic, trying to understand the intimate relationship leading to homicide.

Despite his growing reputation, Poirot is able to make people underestimate him by his appearance, manner, and history. He seems the alien, not so much from his ex-pat status as from his being “stuck” in a previous era. He seems prissy, antiquated—an odd duck, hopelessly out of touch with the modern world.

It is more appearance than fact. He is a genius at eliciting information when people have no idea they are giving it.

He is also old enough to seem harmless. Physically unthreatening, he often hides his brilliance until it is too late for the over-confident criminal to appreciate.

He is also old enough to seem harmless. Physically unthreatening, he often hides his brilliance until it is too late for the over-confident criminal to appreciate. Poirot is the “master interrogator.” He knows that when a liar talks at length, he often gives himself away, either by revealing a hitherto hidden truth, or by becoming entangled in the details of his lie. As Mark Twain said of the truth: “it’s easier to remember.”

Poirot examines the “what,” “where” and “when” to discover the “why” which reveals the “who.” It is a matter of using “the little gray cells” to orchestrate the revelation of the solution to the mystery.

In the end, it is not the clues, but the guilty temselves that (with Poirot's help) give up the game.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

Murder on the Orient Express

April 23, 2016

Writing Rx and Overdose (2)

The following 10 rules are widely accepted, but should be taken with caution. These “powerful drugs” can benefit you—but only if they address your particular malady. Warning: all medicines are potential poisons, and the side effects may outweigh the benefits.

Please take writing advice (including mine) as you would medicine—only as needed.

Remember what golf pro Harvey Pennick says, “. . . tips are like aspirin. One may do you good, but if you swallow the whole bottle you will be lucky to survive.”

TEN RULES

The Rules 3 through 6 (Prose rules)

3 Avoid using adjectives, except those of color, size and number.

4 Avoid detailed descriptions of characters, places, or things.

5 Never use the word "suddenly"

6 Avoid using adverbs.

The intent of these prose rules is to get to the meat, but the danger is that you will strip away too much and leave the reader with only a tasteless bare bone. I get it that you should convey the thought or action quickly and without unnecessary elaboration. I get it also that you should not be wordy. However, descriptors are the spice of the dish. The key is to not overwhelm the essence by using too much spice.

So let's take a look at these four rules.

Rule #3 : Avoid using adjectives, except those of color, size and number.

Reverting to our pharmaceutical metaphor, this is just plain bad medicine. It is a low-dose poison.

A few examples demonstrate that this rule is worse than useless.

“Gothic cathedral” “faint praise” “holistic approach” “insidious attempt” “cyber attack” All these are obviously useful and appropriate. They do not add useless detail.

Rule #4 : Avoid detailed descriptions of characters, places, or things.

The justification for an economy of words is that “brevity is the soul of wit.” But prose is not a collection of witty sayings. It is “prosaic,” but need not be stripped of poetic beauty. The "beauty" comes from accurate description that sets mood or provides quick and necessary information.

For example, describing the hollow sound of footsteps on a marble staircase in the courthouse might enhance the mood of fearful anticipation when a character is about to enter the courtroom.

On the other hand, describing a flock of geese launching themselves from the glassy surface of a pond might add nothing to the mood of a person driving to the courthouse.

Avoid making a description an extended aside. Instead, incorporate descriptions in a way that is "invisible" to the reader. Instead of stopping the action to list all the attributes of the character’s features, appearance, and dress, distribute the descriptors within the action.

To sum up, take a dose of this medicine as needed to remove yourself from the reader’s awareness and keep him inside the scene.

The side effects of an overdose of this drug are generic characters, places, and things along with tepid and bland description. Worse, by not painting an adequate picture, you may fail to tap into the experience and memory the reader brings to the story.

Rule #5 : Never use “suddenly.

Let’s substitute a little weaker medicine for this one: Use “suddenly” sparingly.

If you use “suddenly” more than a few times in a novel, or more than once in a short story, it is a symptom that your writing may be ill—but probably not fatally so.

Rule #6 : Avoid using adverbs.

This is the most abused medicine in the pharmacopeia.

It is prescribed to shorten, simplify, and “clean up” the action. However, removing every word ending in –ly doesn't perfect badly-written prose. It deadens it. Like all descriptors, the adverb focuses and colors actions.

(Do try, however, to remove all adverbs that modify other adverbs.)

Let’s look at a random sentence with and without adverbs.

"In stocking feet, he went to the fireplace and quietly fed kindling to awaken the nearly dead embers."

"In stocking feet, he went to the fireplace and fed kindling to awaken the embers."

Whether you prefer the first or second is a matter of taste, but which tells you more? Do the adverbs enhance or detract from the passage?

To sum up: like words, parts of speech are tools of thought and communication. To change metaphors, they are like the colors, brushes, thinner, and oils of an artist’s palette. Descriptors are pigments used to tint and amend the colors an artist applies as he paints the picture he imagines.

Why would any artist deprive himself of a pigment? Writing with no descriptors is like painting with only primary colors.

April 19, 2016

Writing Rx and Overdose

To quote the great golf teacher, Harvey Pennick, “. . . tips are like aspirin. One may do you good, but if you swallow the whole bottle you will be lucky to survive.”

The following 10 rules are widely accepted, but should be taken with caution. These “powerful drugs” can benefit you—but only if they address your particular malady. Remember, all medicines are potential poisons, and the side effects may outweigh the benefits. So please take writing advice (including mine) as you would medicine—only as needed.

TEN RULES

1 Use no dialog tags other than “said.”

2 Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said.”

3 Avoid using adjectives, except those of color, size and number.

4 Avoid detailed descriptions of characters, places, or things.

5 Never use the word “suddenly”

6 Avoid using adverbs.

7 Never open a book with weather.

8 Avoid flashbacks.

9 Avoid prologues.

10 Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

Let’s examine the first two, the ones concerning dialog.

Dialog Rule #1 Use no dialog tags other than “said.”

So rule #1 seeks to avoid the amateurish technique of “thesaurus tapping” whereby perhaps odd dialog tags are sprinkled around so as to become distracting to the reader. Remember that the writing, like the author, should be “invisible.” You want your reader to be in the story, not the mechanics of your writing. However, are we really supposed to throw away all our tag words except “said?”

All words are tools. Why throw them away? Use them to say something. A dialog tag should not be relegated to keeping track of who is speaking. Words like “murmured,” “ muttered,” “whispered” and “sobbed” are useful and “invisible” if employed with skill. They add color, nuance, and emotion.

Dialog rule #2 Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” (or other tags).

I suppose this medicine is intended to keep you from unnecessarily qualifying the way your characters deliver their lines. I get it. However, since an adverb is a word, and since every word is a tool of thought and expression, employ one if it is the best tool for the job.

Compare these two lines of dialog:

“Don’t you ever say that again,” she whispered harshly.

“Don’t you ever say that again,” she said.

Which is the more vivid expression?

April 14, 2016

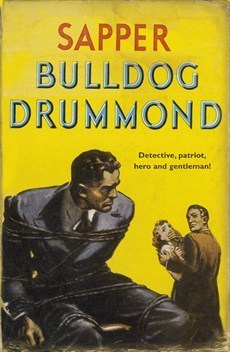

Legendary Detectives: Bulldog Drummond

The caption on the cover of the first book says it all: “Detective, patriot, hero, and gentleman.”

The caption on the cover of the first book says it all: “Detective, patriot, hero, and gentleman.”

The cold-blooded, coolly-calculating, cerebral types are all right, but the post-World War I reading public craves a two-fisted, hot-blooded man with common sense, a man capable of and willing to meet out summary justice and set things right. They need a hero, a man of action.

The Great War is finally over, and the people are ready for a detective who is “all man.” They want a man like Hugh Drummond.

He is a type of ideal gentleman, one who is comfortably acquainted with his social inferiors, especially a group of former comrades in arms who aid him in his adventures. He is patriotic, loyal, morally and physically courageous. He is a big, strong, impressive man, but not particularly attractive. Or perhaps he is ruggedly handsome.

Hugh "Bulldog" Drummond is a wealthy gentleman, fresh from the western front where his heroic exploits have equipped him with confidence and the hunter’s skill of stealth. He can really handle himself, being an expert boxer and a crack shot. He can kill quickly, economically, and without a hint of second thought.

PTSD was called “shell-shock” after the Great War, but it was seen as a weakness rather than as an illness. The muddy carnage of trench warfare may have taken the glamour from combat, but it did not lessen respect for the valor of those who contested in it. Drummond was brutalized by the war, but it only tempered his strength. He knows things—has done things that others have not, and that equips him with skills and the demeanor to solve thorny problems and right wrongs. If ever a man was born to cut the Gordian Knot, it is Bulldog Drummond.

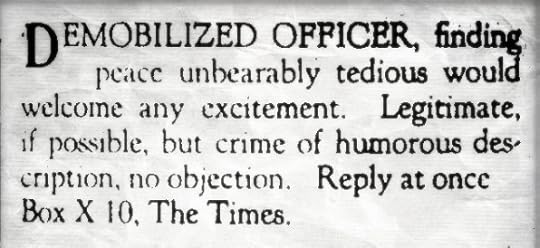

The former officer was intrepid—one might say fool-hardy during the war. (He carried out his own solo sorties in the hellish no-man’s-land between the trenches.) It shouldn't surprise us that he misses the adrenaline rush of combat. He places the following personal in the newspaper.

With that ad, Sapper (H.C. McNeile) introduces Drummond and the “hard-boiled” detective genre.

Sherlock Holmes had Moriarty.

Drummond has Carl Peterson.

But remember: The female of the species is more deadly than the male. He has a second nemesis: Peterson’s wife, the femme fatale Irma Peterson.

So what does "The Bulldog" bring to the table?

What is his method of investigation?

He is the gentleman-adventurer, a man with the courage of a war hero and the solid common sense of the average man. Sure. He follows clues, tracks down leads, and brings the culprit to justice, albeit Drummond's concept of justice, not necessarily the legal system's. Quite often, he sketches out a plan of action, but "muddles through" (perhaps "ad libs" is a better way to describe it). The one thing Bulldog Drummond is not: he is not frustrated by technicalities. He gets things done, presaging Spillane's "I The Jury."

Bulldog Drummond

April 12, 2016

Reading With Both Sides of Your Brain

Okay, the whole left-brain/right-brain theory was overblown. People aren’t one or the other. We aren’t divided into bean-counters and artists. There are, however, some functions that are localized by hemisphere. An interesting study of people who had the halves of their brains surgically disconnected by severing the corpus callosum showed that both perception and the ability to communicate perception were drastically altered.

After the operation, they were fitted with a viewing apparatus so that the left eye saw one thing, and the right another. (They saw an X and an O, one with the left eye and one with the right.) When asked to say what they saw, the people who had undergone the split brain operation said they saw an X. When asked to write what they saw, however, the wrote an O. I may have that backwards as far as the X’s and O’s, but the point is that the two sides of the brain were perceiving things and communicating those perceptions quite differently.What does that have to do with writing? I believe it has everything to do with both writing and effective reading. Let me explain. When writing dialog, one must “hear” it as it is spoken. I mean that literally. When I write dialog, I imagine it being spoken as a particular character would say such a thing. (I have no idea if other authors do that or not, or for that matter, it it’s supposed to be done that way.) For me to communicate the meaning, tone, connotation, and emotion involved, I must hear the dialog in situ. For the reader to perceive what I write, he must do the same. To do this, each of us must use both sides of our brain, the analytical and the creative/artistic sides. The writing/reading experience is an attempted melding of two realities, two worlds if you will. As a writer, I want you to step into my world, to actually experience it the way I do.

As with hearing, so with seeing. I wish to paint a picture so that you can visualize it. Have you ever seen a movie that was better than the book on which it was based? Perhaps you have. I seldom have. The reason, I think, is that when really into a book, my imagination paints the scenes, the faces, and the action. It transports me into a world partly of my own creation. Therefore, the book is more real to me than a movie, because the movie is someone else’s creation.

So, what is the purpose of this discussion? I suppose I want to urge you to give full range to your imagination when you read. But to do that, you must read slowly. Pay attention to the words used. Pay attention to the punctuation. Stop and think often. Reading is the perfect example of Gestalt: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The writing is nothing without your unique interpretation. You are make it live.

April 11, 2016

Legendary Detectives: Father Brown

Dupin introduced us to the gentleman detective using keen observation, precise reasoning, and mind-hunting via creative imagination to solve crimes. Sherlock Holmes took observation and single-minded obsession to new heights, ridding himself of emotion to apply cold, sharp logic. He added fingerprint, footprint, trace evidence examination, chemical analysis, and postmortem examination to his toolkit. He was the prototypical CSI.

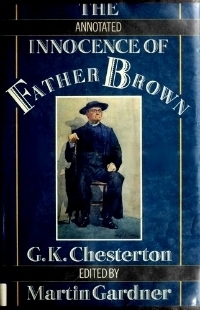

Inevitably, a detective came along who, while logical, employed the less tidy side of his brain, the intuitive faculty. G. K. Chesterton introduced us to Father Brown in “The Blue Cross” (1910). Poe and Conan Doyle gave us the “man of leisure” prototype of detective; Chesterton gave us the “cleric/detective” common in the Cozy Mystery genre. The first compilation of Chesterton’s short stories, “The Innocence of Father Brown,” was published in 1911. Four more compilations followed, the last in 1935.

At first glance, it seems odd that a cloistered “man of the cloth” should immerse himself in ugly mayhem and ungodly crimes. Chesterton, however, asks who is privy to more sins and crimes than a minister? How innocent of ugliness can a man be who occupies the confessional? A priest is not a hermit monk who has withdrawn from the world.

Let’s take a look at Chesterton’s hero. He is a humble man, given to deep thought but few words.

Father Brown’s appearance decidedly does not inspire confidence, much less fear. He is a short, stocky, dough-faced Roman Catholic priest, who wears pince nez glasses, a capello Romano priest’s hat, and rumpled clothes. Always at hand is a large umbrella, even as he rides about the parish on his bicycle. His aspect leads people to underestimate him, a device used later by the slovenly-dressed TV detective, Colombo (portrayed by Peter Falk).

So what does Father Brown bring to the table?

What is his method?

What becomes apparent is that the unassuming priest has a vast knowledge of human nature. He has been exposed to as much evil as any policeman—intimately exposed. His toolkit consists of a keen understanding of people, their foibles, temptations, and failures. The cleric tends to intuition more than deductive reasoning, although he employs both. He observes carefully and applies logic, but he primarily “feels” his way to the solution of the crime.

Dupin and Holmes hint at profiling, but Father Brown is a bona fide “mind-hunter.” He reconstructs the crime in order to get inside the mind of the criminal. In fact, he becomes the murderer (in his mind) and imagines committing the crime. When he gets firmly into the psyche of the criminal, he sees who it is. This is not a fey thing, however, not a séance, nor divine revelation. Father Brown always produces a rational explanation of the crime, and he details the criminal’s motivation.

One final note: don’t think that Father Brown is a man with nothing better to do than gallivant around the parish seeking diversion with juicy murder cases. He is a serious priest, devoted to his church and duties.

The Innocence of Father Brown

April 6, 2016

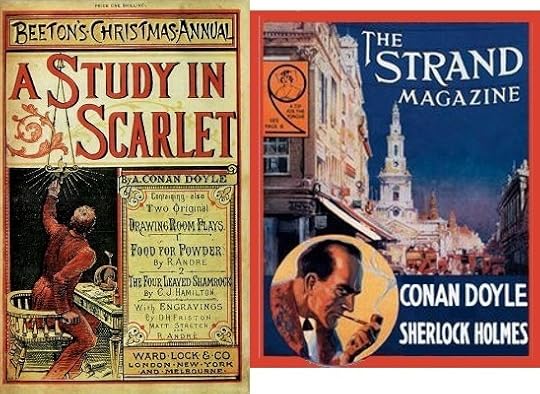

Legendary Detectives: Sherlock Holmes

In the initial Legendary Detectives post, we looked at Poe’s C, August Dupin, introduced in the 1840s story “Murders in the Rue Morgue.” Now we turn to the most famous detective of all time, Sherlock Holmes. Perhaps I can stir your memory or provoke you into reconsidering your image of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's iconic "consulting detective." The problem for us is that Sherlock Holmes has been portrayed by so many actors, and in so many movies and TV episodes, that our present view of him differs from the original character.

Conan Doyle introduces him in "A Study In Scarlet," published in Beeton's Christmas Annual in November of 1887. He continues to flesh him out in adventures published in The Strand magazine. Eventually, the mysteries total 56 short stories and four novels. In these, the author produces a detailed and consistent physical, emotional, and psychological portrait of the first great detective.

Unlike Poe’s paucity of detail as to Dupin’s appearance, Conan Doyle is quite precise in his physical description of Holmes. That’s good because so many actors have portrayed him that we may have a different picture of the man than the stories describe.

The author paints Holmes as a tall and lean black-haired man with piercing gray eyes beneath heavy dark-brown eyebrows. Thin firm lips and a hawk nose complete the thin intense face. He has sinewy arms and long thin fingers. His appearance is angular and wiry to the extreme. For me, the closest match among his portrayers was Peter Cushing. Compare the photo with the painting of Holmes on the Strand cover above.

I’ll not draw conclusions about Holmes's psyche, but only catalog what comes through the stories. He says of himself, "I use my head, not my heart." He abhors emotion as an impediment to rational thought, hence his aversion of women (whom he considers emotional as well as emotion-producing). Perhaps this also explains his disinclination to form new friendships. He has no time for small talk and casual acquaintances. He plays the violin, but otherwise has no interest in the arts (literature included—unless it is sensationalist press stories about mayhem and horror). Holmes is egotistical in the extreme, having no patience for lesser intellects and open contempt for inferior minds. He is cold, precise, and didactic in stating his conclusions. That could be tiring, but it's not.

Holmes is often restless, obsessive, and impatient. At other times, he is consumed with intense ennui which he escapes via drugs that were legal at the time: the famous seven-per cent solution of cocaine and morphine. Is it that his mind needs a puzzle to throw his switch on a bipolar disorder? Or is he, as Benedict Cumberbatch has him say, a “high-functioning sociopath?” I don’t know, but Conan Doyle would never have considered such things. In his day, psychiatrists were “alienists” and psychological disorders might be termed “fevers of the brain.” Holmes is what he is: an extreme enthusiast, at times insufferable, but vastly interesting.

But it's all about method, isn't it?

So what is the Holmes method?

How can he see things as so “elementary?”

To what extent Conan Doyle modeled Sherlock Holmes on Poe's Dupin is a matter of conjecture. Like the strange French detective, Holmes is preternaturally observant, not only of crime scene clues, but of facial expressions, body language, speaking mannerisms and inflections as well as other "tells." Neither miss details that others discount or fail to observe.

Both men are “human lie detectors.” They “cold read” so well that they seem to read minds. Each uses “creative imagination” to get into the minds and understand the actions of the perpetrator. However, Dupin relies on it, while Holmes relies on cold reason. Holmes is also a pioneer in forensic science. Doyle even has him author treatises on innovative CSI work. He breaks the case using logic, deduction, and science. And all of this began in an age when the official investigators were only becoming aware of the CSI tools that Holmes employed.

If he did not invent the mystery genre, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle certainly defined it for decades to come. Moreover, he was the prophet of real-life crime detection much as another Brit, Arthur C. Clarke, was the prophet of space science technology.

A Study in Scarlet

April 5, 2016

Navigating My Posts

To identify the subject matter, all my posts will begin with an appropriate image like this one. I hope it will be helpful in following a thread into my back pages.

April 2, 2016

Legendary Detectives: C. Auguste Dupin

I love mysteries. Nothing is more fun than becoming one of my favorite detectives with a good puzzle to solve. I know that most crime is uncomplicated. The bulk of it is stupid, banal, and squalid. There is little criminal genius in the real world, and our Moriartys are up to financial fraud, not “murder most foul.” Still, I can, and do, suspend disbelief gladly when I pick up a new novel or short story because I love being an investigator, a profiler, a criminologist, or a forensic expert—a sleuth of any stripe.

In this series of posts, I want to share with you some of my encounters with legendary detectives. I’ve followed some closely, been briefly introduced to others, but only know some by reputation. Let me share a few interesting things I know about them. I’m sure that you can list others that I will not include. And I’m equally sure that you know things about each of them that I will fail to mention. This list is a personal one. I make no claim to authority. As with all “best lists,” people will differ. That’s great. As they say, “a difference of opinions is what makes a horse race.”

Jonathan Kellerman has Alex Delaware remark that his friend Milo Sturgis is the only detective he knows that has actually detected anything. A detective goes about detecting by collecting physical evidence and asking questions. This “legwork,” is time-consuming whenever he gets a case without an obvious “who” that “did it.” Real life detectives handle such cases but rarely. The fictional ones do it every time, or else there would be no story for us to climb into.

Let’s take a look at the first detective, Edgar Allen Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin from “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), and “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” (1842), followed by “The Purloined Letter” (1844). (I’ll not argue whether other detectives have a better claim to being first. If we have a difference of opinion, that’s good. It makes for stimulating conversation.)

C. Auguste Dupin

A professional detective, be he a cop or a private investigator, has time for the extensive legwork required because that’s the job. Amateur detectives, however, must find the time and have the money to pursue their cases. That’s why mystery writers often create detectives who are people of leisure with adequate resources. History supplies us with just such people. Beginning during the scientific revolution of the 17th century and continuing through the 19th century, some gentlemen of the nobility devoted their time, resources, and energy to advancing scientific knowledge. Robert Boyle, Henry Cavendish, and Antoine Lavoisier were of the nobility. Charles Darwin was a wealthy and connected doctor’s son. So when Poe chose a man of leisure for his detective, he followed historical precedent.

The narrator who introduces Le Chevalier (Sir) C. Auguste Dupin calls him “that unusual Frenchman.” Dupin’s once-rich noble family has apparently left him only modest means and its prestigious rank. He is a socially unattached man and eccentric. His life is books and a voyeuristic interest in the people among whom he moves with minimal and shallow interaction. He is coldly rational, egotistical, intellectually snobbish, and abrupt to the point of rudeness. Dupin is all brains and no soul. How that works with his being an amateur poet, I have no idea. He is obsessed with puzzles and enigmas. He doesn’t really care for abstracts like “justice.” Nor does he worry overmuch about the falsely-accused. He burns to solve the case for the mere satisfaction of solving it. In short, he’s brilliant and interesting, but not a nice guy. Does that sound like another detective you know? (Hint: he also has a sidekick who chronicles his cases.)

So how does this genius go about the job? He collects facts and then uses both sides of his brain. He pays intense attention to the details, especially the ones that seem to make no sense. He also notices what people do not say as well as what they do say. Dupin is adept at reading people. He notes their hesitations, their manner, their expressions, and their body language. You wouldn’t want to play poker with this strange fellow. The exact “how” leads to an understanding of the “why” which reveals the “who.” He applies a combination of cold logic and creative imagination to get into the head of the criminal. I suppose that makes him the first profiler as well as the first detective.

So how does this genius go about the job? He collects facts and then uses both sides of his brain. He pays intense attention to the details, especially the ones that seem to make no sense. He also notices what people do not say as well as what they do say. Dupin is adept at reading people. He notes their hesitations, their manner, their expressions, and their body language. You wouldn’t want to play poker with this strange fellow. The exact “how” leads to an understanding of the “why” which reveals the “who.” He applies a combination of cold logic and creative imagination to get into the head of the criminal. I suppose that makes him the first profiler as well as the first detective.The Murders in the Rue Morgue

Musings and Mutterings

- A.R. Simmons's profile

- 59 followers