Legendary Detectives: Sherlock Holmes

In the initial Legendary Detectives post, we looked at Poe’s C, August Dupin, introduced in the 1840s story “Murders in the Rue Morgue.” Now we turn to the most famous detective of all time, Sherlock Holmes. Perhaps I can stir your memory or provoke you into reconsidering your image of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's iconic "consulting detective." The problem for us is that Sherlock Holmes has been portrayed by so many actors, and in so many movies and TV episodes, that our present view of him differs from the original character.

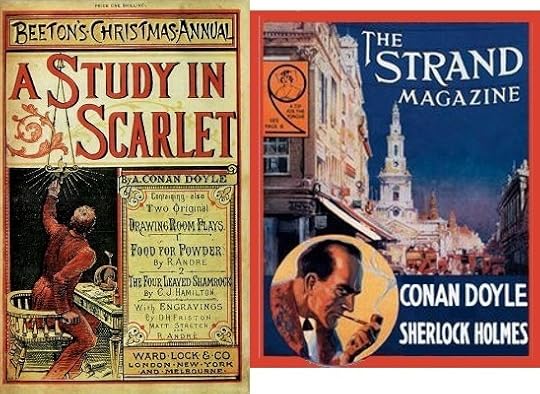

Conan Doyle introduces him in "A Study In Scarlet," published in Beeton's Christmas Annual in November of 1887. He continues to flesh him out in adventures published in The Strand magazine. Eventually, the mysteries total 56 short stories and four novels. In these, the author produces a detailed and consistent physical, emotional, and psychological portrait of the first great detective.

Unlike Poe’s paucity of detail as to Dupin’s appearance, Conan Doyle is quite precise in his physical description of Holmes. That’s good because so many actors have portrayed him that we may have a different picture of the man than the stories describe.

The author paints Holmes as a tall and lean black-haired man with piercing gray eyes beneath heavy dark-brown eyebrows. Thin firm lips and a hawk nose complete the thin intense face. He has sinewy arms and long thin fingers. His appearance is angular and wiry to the extreme. For me, the closest match among his portrayers was Peter Cushing. Compare the photo with the painting of Holmes on the Strand cover above.

I’ll not draw conclusions about Holmes's psyche, but only catalog what comes through the stories. He says of himself, "I use my head, not my heart." He abhors emotion as an impediment to rational thought, hence his aversion of women (whom he considers emotional as well as emotion-producing). Perhaps this also explains his disinclination to form new friendships. He has no time for small talk and casual acquaintances. He plays the violin, but otherwise has no interest in the arts (literature included—unless it is sensationalist press stories about mayhem and horror). Holmes is egotistical in the extreme, having no patience for lesser intellects and open contempt for inferior minds. He is cold, precise, and didactic in stating his conclusions. That could be tiring, but it's not.

Holmes is often restless, obsessive, and impatient. At other times, he is consumed with intense ennui which he escapes via drugs that were legal at the time: the famous seven-per cent solution of cocaine and morphine. Is it that his mind needs a puzzle to throw his switch on a bipolar disorder? Or is he, as Benedict Cumberbatch has him say, a “high-functioning sociopath?” I don’t know, but Conan Doyle would never have considered such things. In his day, psychiatrists were “alienists” and psychological disorders might be termed “fevers of the brain.” Holmes is what he is: an extreme enthusiast, at times insufferable, but vastly interesting.

But it's all about method, isn't it?

So what is the Holmes method?

How can he see things as so “elementary?”

To what extent Conan Doyle modeled Sherlock Holmes on Poe's Dupin is a matter of conjecture. Like the strange French detective, Holmes is preternaturally observant, not only of crime scene clues, but of facial expressions, body language, speaking mannerisms and inflections as well as other "tells." Neither miss details that others discount or fail to observe.

Both men are “human lie detectors.” They “cold read” so well that they seem to read minds. Each uses “creative imagination” to get into the minds and understand the actions of the perpetrator. However, Dupin relies on it, while Holmes relies on cold reason. Holmes is also a pioneer in forensic science. Doyle even has him author treatises on innovative CSI work. He breaks the case using logic, deduction, and science. And all of this began in an age when the official investigators were only becoming aware of the CSI tools that Holmes employed.

If he did not invent the mystery genre, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle certainly defined it for decades to come. Moreover, he was the prophet of real-life crime detection much as another Brit, Arthur C. Clarke, was the prophet of space science technology.

A Study in Scarlet

Published on April 06, 2016 05:08

•

Tags:

crime, csi, detective, detective-fiction, doyle, forensics, mystery, sherlock-holmes, study-in-scarlet

No comments have been added yet.

Musings and Mutterings

Posts about my reading, my writing, and thoughts I want to share. Drop in. Hear me out. And set me straight.

- A.R. Simmons's profile

- 59 followers