Metin Bektas's Blog: Metin's Media and Math, page 2

November 4, 2013

Intensity (or: How Much Power Will Burst Your Eardrums?)

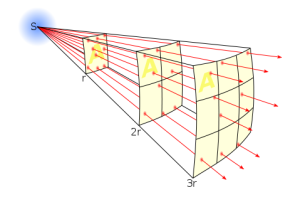

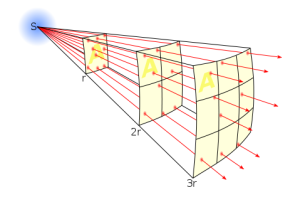

Under ideal circumstances, sound or light waves emitted from a point source propagate in a spherical fashion from the source. As the distance to the source grows, the energy of the waves is spread over a larger area and thus the perceived intensity decreases. We'll take a look at the formula that allows us to compute the intensity at any distance from a source.

First of all, what do we mean by intensity? The intensity I tells us how much energy we receive from the source per second and per square meter. Accordingly, it is measured in the unit J per s and m² or simply W/m². To calculate it properly we need the power of the source P (in W) and the distance r (in m) to it.

I = P / (4 · π · r²)

This is one of these formulas that can quickly get you hooked on physics. It's simple and extremely useful. In a later section you will meet the denominator again. It is the expression for the surface area of a sphere with radius r.

Before we go to the examples, let's take a look at a special intensity scale that is often used in acoustics. Instead of expressing the sound intensity in the common physical unit W/m², we convert it to its decibel value dB using this formula:

dB ≈ 120 + 4.34 · ln(I)

with ln being the natural logarithm. For example, a sound intensity of I = 0.00001 W/m² (busy traffic) translates into 70 dB. This conversion is done to avoid dealing with very small or large numbers. Here are some typical values to keep in mind:

0 dB → Threshold of Hearing

20 dB → Whispering

60 dB → Normal Conversation

80 dB → Vacuum Cleaner

110 dB → Front Row at Rock Concert

130 dB → Threshold of Pain

160 dB → Bursting Eardrums

No onto the examples.

----------------------

We just bought a P = 300 W speaker and want to try it out at maximal power. To get the full dose, we sit at a distance of only r = 1 m. Is that a bad idea? To find out, let's calculate the intensity at this distance and the matching decibel value.

I = 300 W / (4 · π · (1 m)²) ≈ 23.9 W/m²

dB ≈ 120 + 4.34 · ln(23.9) ≈ 134 dB

This is already past the threshold of pain, so yes, it is a bad idea. But on the bright side, there's no danger of the eardrums bursting. So it shouldn't be dangerous to your health as long as you're not exposed to this intensity for a longer period of time.

As a side note: the speaker is of course no point source, so all these values are just estimates founded on the idea that as long as you're not too close to a source, it can be regarded as a point source in good approximation. The more the source resembles a point source and the farther you're from it, the better the estimates computed using the formula will be.

----------------------

Let's reverse the situation from the previous example. Again we assume a distance of r = 1 m from the speaker. At what power P would our eardrums burst? Have a guess before reading on.

As we can see from the table, this happens at 160 dB. To be able to use the intensity formula, we need to know the corresponding intensity in the common physical quantity W/m². We can find that out using this equation:

160 ≈ 120 + 4.34 · ln(I)

We'll subtract 120 from both sides and divide by 4.34:

40 ≈ 4.34 · ln(I)

9.22 ≈ ln(I)

The inverse of the natural logarithm ln is Euler's number e. In other words: e to the power of ln(I) is just I. So in order to get rid of the natural logarithm in this equation, we'll just use Euler's number as the basis on both sides:

e^9.22 ≈ e^ln(I)

10,100 ≈ I

Thus, 160 dB correspond to I = 10,100 W/m². At this intensity eardrums will burst. Now we can answer the question of which amount of power P will do that, given that we are only r = 1 m from the sound source. We insert the values into the intensity formula and solve for P:

10,100 = P / (4 · π · 1²)

10,100 = 0.08 · P

P ≈ 126,000 W

So don't worry about ever bursting your eardrums with a speaker or a set of speakers. Not even the powerful sound systems at rock concerts could accomplish this.

----------------------

This was an excerpt from the ebook "Great Formulas Explained - Physics, Mathematics, Economics", released yesterday and available here: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00G807Y00.

First of all, what do we mean by intensity? The intensity I tells us how much energy we receive from the source per second and per square meter. Accordingly, it is measured in the unit J per s and m² or simply W/m². To calculate it properly we need the power of the source P (in W) and the distance r (in m) to it.

I = P / (4 · π · r²)

This is one of these formulas that can quickly get you hooked on physics. It's simple and extremely useful. In a later section you will meet the denominator again. It is the expression for the surface area of a sphere with radius r.

Before we go to the examples, let's take a look at a special intensity scale that is often used in acoustics. Instead of expressing the sound intensity in the common physical unit W/m², we convert it to its decibel value dB using this formula:

dB ≈ 120 + 4.34 · ln(I)

with ln being the natural logarithm. For example, a sound intensity of I = 0.00001 W/m² (busy traffic) translates into 70 dB. This conversion is done to avoid dealing with very small or large numbers. Here are some typical values to keep in mind:

0 dB → Threshold of Hearing

20 dB → Whispering

60 dB → Normal Conversation

80 dB → Vacuum Cleaner

110 dB → Front Row at Rock Concert

130 dB → Threshold of Pain

160 dB → Bursting Eardrums

No onto the examples.

----------------------

We just bought a P = 300 W speaker and want to try it out at maximal power. To get the full dose, we sit at a distance of only r = 1 m. Is that a bad idea? To find out, let's calculate the intensity at this distance and the matching decibel value.

I = 300 W / (4 · π · (1 m)²) ≈ 23.9 W/m²

dB ≈ 120 + 4.34 · ln(23.9) ≈ 134 dB

This is already past the threshold of pain, so yes, it is a bad idea. But on the bright side, there's no danger of the eardrums bursting. So it shouldn't be dangerous to your health as long as you're not exposed to this intensity for a longer period of time.

As a side note: the speaker is of course no point source, so all these values are just estimates founded on the idea that as long as you're not too close to a source, it can be regarded as a point source in good approximation. The more the source resembles a point source and the farther you're from it, the better the estimates computed using the formula will be.

----------------------

Let's reverse the situation from the previous example. Again we assume a distance of r = 1 m from the speaker. At what power P would our eardrums burst? Have a guess before reading on.

As we can see from the table, this happens at 160 dB. To be able to use the intensity formula, we need to know the corresponding intensity in the common physical quantity W/m². We can find that out using this equation:

160 ≈ 120 + 4.34 · ln(I)

We'll subtract 120 from both sides and divide by 4.34:

40 ≈ 4.34 · ln(I)

9.22 ≈ ln(I)

The inverse of the natural logarithm ln is Euler's number e. In other words: e to the power of ln(I) is just I. So in order to get rid of the natural logarithm in this equation, we'll just use Euler's number as the basis on both sides:

e^9.22 ≈ e^ln(I)

10,100 ≈ I

Thus, 160 dB correspond to I = 10,100 W/m². At this intensity eardrums will burst. Now we can answer the question of which amount of power P will do that, given that we are only r = 1 m from the sound source. We insert the values into the intensity formula and solve for P:

10,100 = P / (4 · π · 1²)

10,100 = 0.08 · P

P ≈ 126,000 W

So don't worry about ever bursting your eardrums with a speaker or a set of speakers. Not even the powerful sound systems at rock concerts could accomplish this.

----------------------

This was an excerpt from the ebook "Great Formulas Explained - Physics, Mathematics, Economics", released yesterday and available here: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00G807Y00.

The Time Value of Money and Inflation

To make a point, I'll start this blog entry in an unusual way, that is, by talking about vectors. A vector is basically an ordered row of numbers. Consider this expression for example:

(12, 3, 5)

This vector could represent a lot of things. For example a point in a three dimensional coordinate system, with the vector components being the x-, y- and z-values respectively. Or for a company offering three products, it could stand for the sales of these products in a certain year.

Why this talk about vectors? You were probably very surprised when you heard grandma say that she paid only 150 $ for her first car. It seems so amazingly cheap. But it is not. Your dear grandma is talking about 1950's money, while you are thinking of today's money. These two have a very different value.

If you want to specify the costs of a good precisely, merely giving an amount of money will not be sufficient. The value of money changes over time and thus to be absolutely precise, you should always couple this amount with a certain year. For example, this is what grandma's car really cost:

(150 $, 1950)

This is far from (150 $, 2012), which is what you were thinking of when grandma shared the story with you. Using an online inflation calculator, we can conclude that this is actually what the car would cost in today's money:

(1410 $, 2012)

Not an expensive car, but certainly more than 150 $ in today's money. Now you can see why I started this chapter using vectors. They allow us to easily and clearly couple an amount with a year. A true pedant would even ask for one more component since we are still missing the respective months. But let's not get too pedantic.

How can we justify saying that 150 $ in 1950's money is the same as 1410 $ in today's money? We can look at how much of a certain good these amounts would buy in the given year. With 150 $ in 1950 you could fill your basket with about as many apples as you can with 1410 $ today. The same goes for most other common goods: oranges, potatoes, water, cinema tickets, and so on.

This is inflation, goods get more expensive each year. At a later point we will take a look at what reasons there are for inflation to occur. But before that, let's define the rate of inflation and see how it is measured ...

This was an excerpt from the ebook "Business Math Basics - Practical and Simple", available for Kindle here: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00FXB8QSO.

(12, 3, 5)

This vector could represent a lot of things. For example a point in a three dimensional coordinate system, with the vector components being the x-, y- and z-values respectively. Or for a company offering three products, it could stand for the sales of these products in a certain year.

Why this talk about vectors? You were probably very surprised when you heard grandma say that she paid only 150 $ for her first car. It seems so amazingly cheap. But it is not. Your dear grandma is talking about 1950's money, while you are thinking of today's money. These two have a very different value.

If you want to specify the costs of a good precisely, merely giving an amount of money will not be sufficient. The value of money changes over time and thus to be absolutely precise, you should always couple this amount with a certain year. For example, this is what grandma's car really cost:

(150 $, 1950)

This is far from (150 $, 2012), which is what you were thinking of when grandma shared the story with you. Using an online inflation calculator, we can conclude that this is actually what the car would cost in today's money:

(1410 $, 2012)

Not an expensive car, but certainly more than 150 $ in today's money. Now you can see why I started this chapter using vectors. They allow us to easily and clearly couple an amount with a year. A true pedant would even ask for one more component since we are still missing the respective months. But let's not get too pedantic.

How can we justify saying that 150 $ in 1950's money is the same as 1410 $ in today's money? We can look at how much of a certain good these amounts would buy in the given year. With 150 $ in 1950 you could fill your basket with about as many apples as you can with 1410 $ today. The same goes for most other common goods: oranges, potatoes, water, cinema tickets, and so on.

This is inflation, goods get more expensive each year. At a later point we will take a look at what reasons there are for inflation to occur. But before that, let's define the rate of inflation and see how it is measured ...

This was an excerpt from the ebook "Business Math Basics - Practical and Simple", available for Kindle here: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00FXB8QSO.

Published on November 04, 2013 14:14

•

Tags:

business, inflation, money, time-value