Dane Cobain's Blog, page 15

June 16, 2017

More Than You Can Shake a Stick at

I haven’t really stopped since moving from full-time employment to full-time freelance. There’s a huge amount of work for me to do – more than you can shake a stick at – and so I decided to write a poem.

Sometimes you have to ask yourself,

“Why the hell did I agree to this?”

Life is more about the yesses

than the nos of course

but sometimes a yes

can land you

in some trouble.

You take on

more than you should take on

and your schedule of work

starts to look more like

the long road

we all must

walk along.

And then the time

you thought you’d save

just rushes to the grave

in desperation,

like a clock

when the hands

start to shake

a bit.

Oh I know

I get a lot done

when I put my mind to it,

but I can’t switch off

when someone’s watching.

They’re waiting for me

to fall over.

Basically,

I need to write

a novel;

one every six weeks

should do the trick.

Or at least

its nearest equivalent

in scripts, blogs

and whitepapers.

Power

I wrote this poem the day after the general election over here in the UK, as you can probably tell. I don’t think any further comment is necessary – enjoy!

It’s the big day after

a general election

and nobody really

wins or loses,

except for the public.

I’m almost thirty years old

and my party of choiuce

has never come out

at the top of the totem

poll.

That’s probably unsurprisinhg

because really

what do I know

about running

a country?

If I was

the glorious leader

I’d make people beg

for nuclear disarmament,

or maybe even

just call in sick

and watch the TV.

It must be

those Nazi

documentaries;

they made me think

the best way to pick a leader

is to find the man

or woman

who doesn’t want

to do it.

When people seek power,

it automatically means

they don’t deserve it.

I don’t deserve it

either.

Everything Now

This is a relatively recent poem about how we live in a culture that expects… well, everything now. This is particularly apparent when I’m working on freelance projects, because a lot of people forget that freelancers work with multiple clients and expect you to drop everything to work on their project. It’s definitely a balancing act.

Everything now

and not tomorrow

my friend

you forget

there’s a general

election.

I don’t know how

we keep living longer

when the days become short

and unmanageable,

and thanks largely

to the global economy

there’s always someone

somewhere

who needs you

to do something.

There’s even a guy

from Ethiopia

who said

he wants to give me

his inheritance;

it isn’t legit,

but I still want

to click it.

Meanwhile

my liver is shot

and I wonder if

I’ll ever heal it,

so I’ll smoke

another cigarette

while the world spins on

without me.

Or maybe it’s standing still

and my head is spinning.

Yesterday

I learned

that the earth

is closer to the sun

than it is to Masr,

at least

on average.

That’s the kind of thing

that blows my mind,

and I didn’t even have

a hangover.

It made me realise

we’re insignificant,

little blips in existence

like grains of sand

on a football field.

Then I went to an open mic

and forgot all about it.

There’s a moral there,

but I don’t quite know

what it is.

June 10, 2017

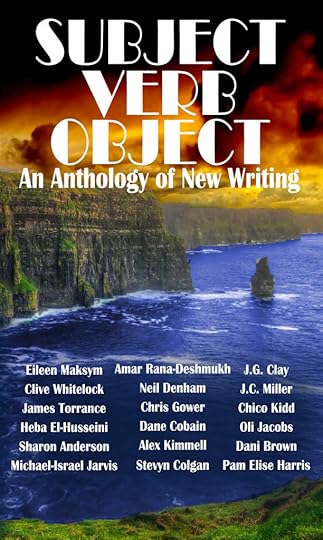

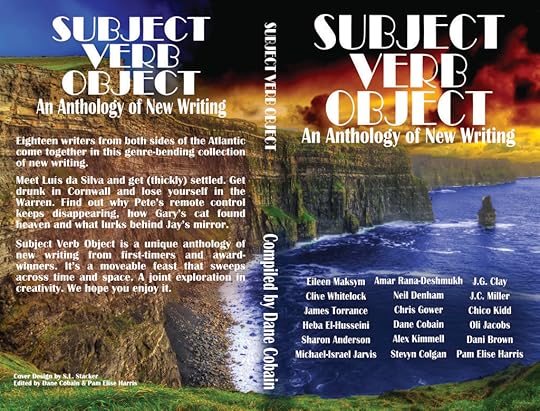

Introducing Subject Verb Object: An Anthology of New Writing

Hi, folks! Today is an exciting day because it’s launch day for Subject Verb Object: An Anthology of New Writing! Read on to find out more and to learn how to snag yourself a copy.

Dane Cobain – Subject Verb Object

Dane Cobain – Subject Verb Object

Eighteen writers from both sides of the Atlantic come together in this genre-bending collection of new writing.

Meet Luís da Silva and get (thickly) settled. Get drunk in Cornwall or lose yourself in the Warren. Find out why Pete’s remote control keeps disappearing, how Gary’s cat found heaven and what lurks behind Jay’s mirror.

Subject Verb Object is a unique anthology of new writing from first-timers and award-winners. It’s a moveable feast that sweeps across time and space. A joint exploration in creativity. We hope you enjoy it.

The anthology contains pieces by the following authors:

James Torrance

Alex Kimmell

Dane Cobain

Neil Denham

Amar Rana-Deshmukh

Oli Jacobs

J. G. Clay

Chris Gower

Michael-Israel Jarvis

JC Miller

Dani Brown

Clive Whitelock

Heba El-Husseini

Pam Elise Harris

Stevyn Colgan

Sharon Anderson

Eileen Maksym

Chico Kidd

Subject Verb Object Paperback

Subject Verb Object Paperback

As always, thanks a lot for visiting, and be sure to follow me on Facebook and Twitter for further updates. You can also click here to check out Subject Verb Object on Amazon. I’ll see you soon!

June 8, 2017

A Wild Goose Chase

This piece is another Leipfold short story. I had planned to explore his backstory through a short story collection, but I’m not sure what’s happening with that due to it taking me forever to get the first novel out. Still, it’s a fun intellectual activity to see what he was like when he was younger, and a few familiar faces make a special guest appearance too. Enjoy.

LEIPFOLD HAD A HANGOVER.

It was a banging hangover, the kind that takes your legs out from beneath you and leaves a gritty, bloody taste in the mouth. He hadn’t showered for several days, he’d been drinking for about as long, and he couldn’t remember when he’d last eaten. There was a vague recollection of dry roasted peanuts, but he couldn’t place it. From the night before, perhaps.

He groaned and raised his head. It throbbed like he’d been kicked in the head by an angry mule. The angry world was spinning in front of him, and he dropped his head again. It thudded off something solid and the pain blinded him all over again. He blacked out.

Leipfold woke up for the second time several minutes later. The ache hadn’t subsided, but the world was slightly more in focus and he was able to focus enough to see the hands of the clock as they ticked slowly around, marking the seconds as life slipped away from him.

He sighed and massed his temples, then forced himself to stand up and to look around him. He was at home, in the tiny London bedsit that he’d moved into after his dishonourable discharge from the army. He hated the place, but it was all he could afford – and without a fixed job, he didn’t think much of his chances of getting out of there.

Leipfold brushed his teeth and made himself a strong cup of coffee, then whipped together a bowl of instant noodles. He smothered it with soy sauce to try to give the stuff some flavour, then scooped the noodles lazily into his mouth with a plastic fork. It tasted like shit in a sandwich, but it was all he could afford – and, according to his calculations, it offered the most calories for the lowest price. The soy sauce was his only luxury.

Leipfold didn’t have a phone, so he started every day by taking a trip down the stairs to the front door, where his mail was deposited on the floor in an ugly bundle by the building’s lazy postman. He sorted through it, dropping his neighbours’ mail into the relevant slots and keeping hold of a couple of pieces that were addressed to him. His mail could wait – he could already tell that they were bills, and there was no point opening them until he knew he had the money to pay for them.

He tottered outside and breathed deeply as the cool, spring air hit his nostrils. The fresh air helped, and the hangover slipped to the back of his mind, at least for a moment. He wondered if he was safe to drive, then figured that even if he was, he wouldn’t be for much longer. So he decided to walk to the Rose and Crown instead.

The old pub wasn’t the most inspiring of places, but it was good enough for Leipfold as a base of operations. Cedric, the landlord, was a happy-go-lucky kind of guy who didn’t ask too many questions of his customers. And he owed Leipfold a favour – a big one – from back when he’d been too young to even drink in the establishment. Leipfold used it as a pass to use the pub’s telephone, making a dozen or more calls a day. He was in trouble.

He needed work.

He ordered a pint from the bar and carried it over to his usual table in the corner. Cedric had already stacked up the day’s papers with The Tribune on top, so Leipfold settled into his daily routine by skimming through the paper until he reached the jobs section and the personal ads. They were always the same, or close enough for it to make no difference. Since his discharge from the army, he’d worked a number of dull, dead end jobs which had helped to pay the bills but which had left him feeling worn and backbroken, his spirits crushed. And most had only kept him for a couple of days – a week at the most – before letting him go.

The door opened and a man walked in, but Leipfold was in a world of his own. His hands were absentmindedly circling possibility opportunities while his mind wandered off by itself. Then someone sat a glass down on the table in front of him and startled him so much that he knocked the papers to the ground.

Leipfold looked up at the man and found himself facing another surprise. The man was not just a man – he was a policeman in full uniform, a sight that you didn’t often see in the Rose and Crown. The officer smiled and Leipfold looked at him – really looked at him. There was something in his eyes or his chiseled brow that reminded him of–

“James Leipfold,” the policeman said. “Long time no see.”

“It’s you,” Leipfold replied. “I remember you.”

“Yes,” the cop said. He smiled. “I see you don’t remember my name, though. Jack Cholmondeley. Good to see you again.”

“I suppose it’s good to see you too,” Leipfold replied. “How have you been?”

“Not bad,” Cholmondeley said. “Not bad at all.”

They paused. Leipfold took a swig from his drink and looked at the policeman, who smiled and slid another pint across to him.

“I can’t drink on duty, James,” Cholmondeley said. “But that doesn’t mean you can’t have a drink on me. I heard about what happened to me.”

“Nothing happened to me.”

“That’s not what I heard,” Cholmondeley said. “But perhaps it’s for the best. You were always too good for the army.”

“People died,” Leipfold murmured.

“That’s what people do.”

Another silence descended on the two men. Leipfold stared moodily at is pint while Cholmondeley’s radio crackled.

“How are you making your money, James?” Cholmondeley asked, eventually. Leipfold looked across at him sharply, but he could detect no malice in the policeman’s eyes. For what it was worth, it seemed like a genuine question.

“I’m not,” Leipfold said. “Not really.”

“I thought as much.” It went silent again. Leipfold left Cholmondeley with the stack of papers while he nipped to the little boys’ room. When he came back, the policeman was still there, and he’d bought him another drink.

“Two drinks?” Leipfold said. He raised an eyebrow, the hint of a smile in the corner of his mouth. It was the early afternoon and Cholmondeley had just lined up pints number four and five, which meant he was already a little merry and well on the way to the blissful stage when anything seems possible, the best stage to be in when trying to land a little work. “Anyone would think you’re trying to corrupt me.”

“Something like that,” Cholmondeley said. “Listen, I have a favour to ask.”

“You have a favour to ask?”

“That’s what I said.”

Leipfold laughed. “You haven’t seen me for years. How did you even find me?”

“I have my ways,” Cholmondeley said.

Leipfold chuckled. “You think I’m yours for two pints?” he asked. He thought it over. “What the hell. What’s the favour?”

“Well,” Cholmondeley said. “That’s just it. I wanted to pick your brains about something. Something off the record.”

“Why me?” Leipfold asked. “Why not ask one of your coppers?”

“I don’t want anybody to know,” Cholmondeley said. “Nobody. But I need help. I think you can help me, and I also think you can keep a secret. Better still, you don’t know anyone that I know. I can talk to you in confidence.”

“You hardly know me.”

“That’s rather the point,” Cholmondeley said. He looked around the room conspiratorially and felt satisfied by what he saw. Then he reached into an inside pocket and pulled out a plain-looking envelope. He tossed it over to Leipfold, who held it suspiciously in front of his eyes before slitting the seal with a fingernail and opening it up. He tipped it upside down and a half dozen rigid sheets of paper slid out and onto the beer-stained table in front of him.

“They used PVA glue,” the policeman explained. “PVA glue and old newspapers. Looks like a kid’s art project.”

“What the hell is this?” Leipfold asked.

“See for yourself,” Cholmondeley said.

So Leipfold did. He picked up the first of the notes by the corner, then held it up to the light to examine it. Someone had made the note by cutting different letters out of a newspaper and sticking them to the page in a haphazard jumble of different colours and fonts. The first note read, “FOlL0w thE CLUeS, MR. P0LicEMaN.” It was followed by another note, and then another, both of which read like the riddles from the adventure books that Leipfold read as a boy. It was all, “I’m tall when I’m young and short when I’m old.”

Leipfold gasped as he continued to work his way through the letters, and Cholmondeley asked him what he made of it.

“Hard to tell,” Leipfold said. “But whoever sent them was well-educated. At least, they were well-educated enough to use correct grammar, spelling and punctuation.”

“But what do they want?”

“It’s a treasure hunt,” Leipfold said. “Looks like you need to follow the clues.”

“No shit,” Cholmondeley replied. “I figured that out already.”

“How did you get the notes?”

“The first one was delivered to the station,” Cholmondeley said. “Addressed to me in a plain white envelope.”

“Does anyone else know about it?”

Cholmondeley shook his head. “Not yet,” he admitted. “It felt…personal, somehow. I didn’t want to share it.”

“But you shared it with me,” Leipfold reminded him.

“Well that’s just it,” Cholmondeley said. “I need help. I tracked down the first four clues without a hitch. Each one pointed to a location, and each location had another clue for me. But now I’m stuck on this one.”

Cholmondeley sorted through the sheets of paper until he found the one that he wanted, then slid it across to Leipfold over the table. Leipfold reached over to grab it, nudging his forgotten pint aside as he did so. He read the message out loud.

“I’m a place of worship but I live atop the river,” he intoned. “I’m the final little secret for the city to deliver.”

“Weird, right?”

“Not at all,” Leipfold said. “That’s Vauxhall Bridge.”

Cholmondeley looked across at him, stunned. “It is?”

Leipfold nodded. “There’s a sculpture of St. Paul’s on it. It’s down the side, but you can’t miss it if you look for it.”

“And you just happened to look for it?”

“I just know things,” Leipfold said. He grinned. “Have you wondered what this is all about? What these things mean and why they were sent to you in the first place?”

“Of course,” Cholmondeley replied. “Who wouldn’t? In fact, that’s the question that I want an answer to. And it’s why I’m trying to solve the bloody thing in the first place.”

“You must have some idea.”

“I have several,” Cholmondeley said. “But if I follow the clues to the end then I won’t have to speculate. I’ll know.”

“Spoken like a true copper,” Leipfold muttered.

“What was that?” Cholmondeley asked.

But Leipfold refused to repeat it, so Cholmondeley shook his hand and left him to it, scouring the paper for vacancies while cradling the remnants of his free pint of lager.

***

Cholmondeley headed back to the station and cracked on with his work, ploughing through case notes like there was no tomorrow until clocking off time, when he packed it all neatly away and headed out of the building. His meagre salary wouldn’t stretch to a vehicle, but he was more than happy to take the tube around – or, when he was on duty, to hop behind the wheels of a police vehicle.

It was getting late by the time that he left the office, but the treasure hunt felt like a stone around his neck and he knew that if he didn’t visit the bridge, he wouldn’t sleep. So he hopped on the Victoria line and raced over to Vauxhall Bridge, arriving in the south of the city just as the sun was starting to set.

Cholmondeley walked up and down the bridge with his usual policeman’s swagger, trying to get a feel for the place before he bit the bullet and looked for what he was looking for. He found it on the upstream side of the bridge, a sculpture of the city’s iconic cathedral in the hands of a beautiful woman who held a pair of calipers in her right hand and the cathedral in her left. She was tall – taller than any woman Cholmondeley had ever met – and she was imposing, and the policeman had no idea how he was going to get down to her.

And then he saw the message, and he laughed and laughed and laughed. It was written in waterproof chalk on the pavement and read “for a good time, call…” It was followed by an eleven digit phone number. Cholmondeley wrote the number down in his notebook and made his way to the nearest phonebox, then entered a few coins and punched a few digits. There was a click and then somewhere, a phone began to ring.

It rang and then it rang some more. Then it clicked through to an answering machine and a familiar voice transmitted itself through the airways.

“Hello, Jack,” Leipfold said. “It’s me.”

“Son of a bitch,” Cholmondeley growled.

“Listen, there’s a point to all of this,” Leipfold continued. “You’re probably asking what this is all about and why I put you through your paces to get you this far.”

“You’re damn right.”

“Do you remember the Swires kid? Well, he’s not a kid anymore. Word on the street is that he did something. He did something bad. Now, I’m willing to help you to take him down, but I needed a little assurance. If I help you out, you have to promise that you’ll take him down. If this comes back on me, he’ll have me killed.”

“It was a test,” Cholmondeley murmured.

“I need you to keep going on this one,” Leipfold said. “Bear with me, Jack. This one’s a tough one. I want you to find me the garden where sovereigns grow. Then find the place where the fish swim and jump into it. You’ll find the woman you look for with her feet in the silt.”

“And why should I do that?” Cholmondeley asked, although he knew he was talking to a recording. But Leipfold didn’t answer, and there was a click on the other end of the line as Leipfold’s cassette recorder kicked in. Cholmondeley slammed the phone back onto the hook and scowled at it, then headed underground again to retrace his steps.

Leipfold was still in the Rose and Crown when Cholmondeley got back there, although his voice was significantly more slurred and his eyes were like two pricks of light at the end of two tunnels. Cholmondeley wondered how many more drinks he’d had – and whether he’d had any success with his job hunt.

When the policeman entered, a morose silence descended amongst the punters. Even out of uniform, he had the look of someone official, and the evening drinkers at the Rose and Crown were the kind of people who didn’t like to be overheard by strangers. Cholmondeley ordered a pint – what the hell? he thought – and went to sit down next to Leipfold. The younger man didn’t even look up from his newspaper.

“How can I help you, Jack?” he asked.

“You bastard,” Cholmondeley replied. “What’s the deal? I should charge you for wasting police time.”

“You listened to the message, then,” Leipfold observed. “I know you, Jack. I know your kind. I’m willing to bet that you played it by the book. You wouldn’t have wasted police time. That’s why you’re here right now, in your civvies and not your uniform. You’re off-duty.”

“You still wasted my time,” Cholmondeley said.

“So?” Leipfold replied.

Cholmondeley growled and pushed himself back on his seat. Then he stood upright and motioned for Leipfold to do the same.

“You want to fight me?” Leipfold asked. He sounded wry, almost amused. The other punters had drawn back in a semicircle around them. For them, this was the night’s entertainment. They wouldn’t be happy until fists were flying.

But Leipfold refused to get up, and Cholmoneley’s anger dissipated as quickly as it came when he felt the eyes of the drinkers upon him. Leipfold eyed him warily and gestured to the seat opposite him. Cholmondeley took it and stared right back at him.

“Listen,” Leipfold said, carefully. He looked around the room, daring the drinkers to meet his eyes. He couldn’t risk being overheard – not with such a sensitive subject, and definitely not in the middle of the Rose and Crown. “Don’t cause a scene, okay? This is private business. That’s why I started the damn treasure hunt in the first place. If Swires finds out about this…”

“He won’t,” Cholmondeley said.

“Follow the clues, Jack,” Leipfold insisted. “You won’t regret it.”

Cholmondeley wanted to ask for further details, but Leipfold held up his hand and excused himself to go to the little boy’s room. He climbed out of the window and headed off into the night.”

***

It was the following afternoon, and while Cholmondeley was still following the clues on the sly, he’d roped in a little help from the diving team – a man called Wilko who looked a little like the fish that he swam with. Wilko was an unpopular man, but that worked in Cholmondeley’s favour. He didn’t have many friends at the station, but Jack Cholmondeley was one of the popular cops who seemed somehow destined for greatness. So when Cholmondeley asked him for a favour – “strictly off the record, of course” – the man felt almost contractually obliged to help him.

And so Wilko suited him while Cholmondeley drove the car, and they parked outside the Rose and Crown before cutting across the back and along to the riverbank. The water was muddy there and visibility was slim, and Cholmondeley didn’t even know what he was looking for. But with no other active assignments, Wilko was happy to have an excuse to look around, and the murky waters of the Thames provided the perfect training ground.

He went under for ten minutes or so, then surfaced again to get his bearings. He waved at Cholmondeley and removed his mouthpiece, then shouted, “I found something!”

“What is it?” Cholmondeley asked.

But Wilko just shook his head, reattached the mouthpiece and dived back under. He resurfaced a couple of minutes later with a leather case in his hands, which he hauled to the side of the river and dumped onto the bank. Cholmondeley couldn’t wait for the diver to resurface and disengage himself from his equipment, so he worked his hand at the straps and tugged it open. The water had rusted the buckles and the leather had lost some of its colour, but it held it together until Cholmondeley managed to get one of the straps unhooked.

Then a mini waterfall spilled out all over the pavement as the leather folded in on itself and the bag collapsed. The water was the colour of urine and smelled just as bad, and the bag itself had the smell of death all over it. Cholmondeley had smelled it just once before as the first responder to a grizzly suicide, and he knew that it would clog up his nostrils for the days and weeks to come.

Inside the bag, he found a severed arm, half a leg and a clump of scalp with the hair still attached. The stench was unbelievable. It took everything Cholmondeley had to hold his lunch in. Wilko, meanwhile, was spared the stench by his breather, which he was wisely still wearing. He looked quizzically at Jack Cholmondeley, who returned his gaze with a baleful frown.

“We’d better call this in,” Cholmondeley said.

The diver nodded at him and backed away from the bag, then took of his mask and switched back to the natural air that the planet had to offer. “I’ll see you back at the station,” he said. “If anyone asks, I wasn’t here.”

“I won’t involve you unless I have to,” Cholmondeley said. It wasn’t quite a promise, but it was good enough for Wilko, who left the scene and put the call in while Cholmondeley waited for backup to arrive.

Back at the station, they were able to take a closer look at the bag and its unpleasant contents. But Cholmondeley had seen enough, so he left it to the morgue to do their work and told them to have a report on his desk as quickly as possible. Cholmondeley wasn’t even in charge of the case – that dubious honour had been passed onto one of his superiors, a man called Bilstone who scared the bejeezus out of everyone he worked with.

So Cholmondeley found a quiet room with a telephone line and put a call in to the Rose and Crown. Cedric, the landlord, answered on the second ring. He sounded like he’d been drinking on the job, and Cholmondeley surmised that he probably had. It was that kind of pub.

“Get me James Leipfold,” Cholmondeley said.

“Never heard of him,” the man replied.

“Funny looking chap,” Cholmondeley explained. “Red hair. Drinks like a thirsty cat. Sits in your pub while trying to find work.”

“Oh, him,” Cedric said. “I know the one you mean. Hang on, I’ll go and get him.”

Cholmondeley waited impatiently for Leipfold to pick up the receiver. He could hear a dull chattering of voices in the background, the sure sign of a British pub in the inner city. Then Leipfold grabbed hold of the phone and said Hello. He was breathing heavily, like a smoker who’d just placed last in a marathon.

“Leipfold,” Cholmondeley growled, “you could have warned me.”

“Warned you about what?”

“The body, goddamn it,” Cholmondeley said. “How did you know it was there?

“I didn’t,” Leipfold replied. “It was just a good guess. Let’s just say that it was the word on the street.”

“I could bust you as an accessory after the fact.”

“You could,” Leipfold admitted. His voice was slurry but still legible, a little soft around the edges but still clearly the voice of a man who was in possession of all of his faculties. “I hoped that the little treasure hunt would impose upon you the seriousness of the help that I gave you. If word gets out, I’ll be skinned alive. I’m trusting you to keep it to yourself.”

“You made me prove myself,” Cholmondeley said, but he was laughing.

“I had to,” Leipfold replied.

Cholmondeley laughed. It was a bitter laugh, but it had its undertones of geniality, like a department store Father Christmas being made redundant.

“Well, I proved myself all right,” Cholmondeley said. “And now there’s a Jane Doe in the morgue. I don’t suppose you know what happened to her.”

“Blunt force trauma,” Leipfold replied. “At least, that’s the word on the street.”

“Well, we’ll see if that’s true.”

From the other end of the phone line, Cholmondeley could hear Cedric kicking up a fuss and trying to get Leipfold to hang up. The policeman guessed that another of his punters – probably one who paid better – wanted to use it.

“Is there anything else?” Leipfold asked.

“Well, I’m not amused by your bloody antics,” Cholmondeley began, “but I’d be lying if I told you that you don’t have a certain style. Are you sure you won’t reconsider joining the force?”

“I’m sure of it,” Leipfold said. “Jack, I really need to go. Good luck with your investigation.”

“You have a talent, James,” Cholmondeley replied. “A rare talent. If you won’t join me then perhaps you should work against me. Form a detective agency. Start putting those skills of yours to good use instead of wasting my time.”

Cholmondeley waited for a response that never came, but he did think he heard something in that final half a second as he pulled the receiver away from his ear and slammed it back into the cradle.

It sounded like laughter.

But Jack Cholmondeley wasn’t in the mood for laughter. He had half a body in the morgue and a whole heap of unanswered questions. He thought about Jimmy Swires, now grown older and uglier. And he wondered whether he was sleeping well that night.

Whether he had anything on his conscience.

Freedom (Poem)

Now that I’m working full-time as a freelancer, I’m enjoying a certain sense of freedom that’s hard for me to describe, so I thought I’d try to describe how I felt through the medium of poetry. I think it turned out pretty well.

I’ve never felt this good

at half past nine

on a Monday morning.

The weekend passed by

in a blur of car boot sales

and the garden centre

was so middle class

it frightened me.

A load has been removed,

and like a miner with a bad back

I go back towards the coal-face,

only this time

I gather fuel

for my own fireplace.

It’s funny how

a generation of parents

fought hard for a better future

so their kids could drink Jagerbombs

inside a Wetherspoons;

I say

the fight must go on,

and if I don’t become better

I have only myself

to blame.

Look,

freedom isn’t wings

or a motorbike

on the open road;

freedom is just

making a living

how you want to

make a living.

Get a load of this

kid he’s full of it.

A Broken Record (Poem)

Sometimes I feel like a broken record, because my poetry often touches upon the same subjects again and again and again. It’s something that I’ve been thinking about more and more of late, so I wrote a poem to explore it. Here goes.

There’s no need to be

an asshole man

when it’s not going to make

any difference.

You’d think that

we’re trying to cure

CANCER,

instead of selling shit

that somehow causes it.

Have you never seen

Prison Break?

It’s all pointless

really anyway,

like blowing up robots

on computer screens

and racking up

the highest score

on Donkey Kong;

when we leave this world

behind us,

our entire lives

hardly scratched

the surface.

But now I’m just

a broken record.

Sometimes my dreams

are like a trick shot

when you forgot to turn

the camera on,

and I’m going down fast

to the bottom of everything.

My work comes from pain

and suffering,

and it’s not always my

pain to play with.

Whatever man,

I can’t help

who I am,

just like

you can’t help

who you are.

No one ever said

you had

to like me.

June 5, 2017

So I Quit My Job… | Freelance Plans

Well, today’s the day.

A couple of months ago, I handed in my notice at fst and quit my job to do something that I’ve been thinking about for a while. I’m going freelance, and today is my first official day of being a self-employed freelance writer. How exciting!

It’s also scary, most notably because my income will be taking a huge dip. I have enough saved up to keep me going for a couple of months, and so I’m hoping to grow my current income until I’m matching my old salary. But that also means that everything could go wrong and I could end up somehow losing my existing clients and failing to get any new ones.

But still, it’s exiting – and something that I’ve wanted to do for a long time. Now is as good a time as ever, and I’ve been almost working myself into the ground by moonlighting while working a regular job, and so I decided to take the leap and try it out. You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take, so I’d rather try and fail than always wonder what might have happened.

So yeah, that’s a thing. I’m now officially self-employed – or unemployed, if you want to look at like that. Sometimes it feels like that when you’re enjoying what you’re doing so much that it doesn’t feel like work. Just an extension of your own writing.

If you want to find out more about the work that I do and what my rates are, you can check out my portfolio on Slideshare. You can also follow me on Facebook and Twitter for further updates. I’ll see you soon!

May 25, 2017

Poorly Cat

My cat wasn’t feeling very well, so I wrote a poem for him. Here it is.

My cat is ill

and it makes me sad,

and I wonder if I’m a bad

human being.

I think it’s pretty clear

I’d do anything for him,

so this must be

what it’s like to be

a parent.

Unfortunately,

sometimes

you love something

too much;

Bukowski said

you should find it

and let it destroy you.

I’d rather be

destroyed by love

than left alone

like a child

without a mother.

Little Biggie,

now you’re hiding

in the corner

and I don’t think you want

any attentions.

I swear

it’ll be

alright,

my friend,

sometimes life

likes to kick us

in the nutsack.

Don’t worry,

I still think

I love you,

even if

you left your shit

on the blanket

you sleep on.

The Day After a Terrorist Attack

I wrote this because reasons. You know what it’s about.

The Western world

is crying today

as the ambulances

reveal themselves

along the high street.

The police

are overwhelmed

mostly emotional,

standing at the station

as the trains

run on time

to take commuters to work.

Their newspapers

are black-bordered

obituaries,

and I somehow know

this poem

will still be relevant.

It’s starting to feel like

nowhere is safe,

which is what they want,

whoever they are.

Meanwhile

the same desperate seconds

are shown again

and again

while ‘experts’ talk

about whatever they talk about.

Life goes on

of course,

but not

for everyone.

And I,

I’ll hide inside

my house

and write words

that won’t make

any difference.

But at least

I feel

I’ve made sense

of it all;

people are evil

and that’s all

there is to it.

No wonder

I’d rather

live with

animals.