William Krist's Blog, page 45

February 25, 2021

Opening Up the Order A More Inclusive International System

When the world looks back on the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, one lesson it will draw is the value of competent national governments—the kind that imposed social-distancing restrictions, delivered clear public health messaging, and implemented testing and contact tracing. It will also, however, recall the importance of the CEOs, philanthropists, epidemiologists, doctors, investors, civic leaders, mayors, and governors who stepped in when national leaders failed.

Early in the pandemic, as the U.S. and Chinese governments cast research into the new coronavirus as a jingoistic imperative, the world’s scientists were sharing viral genome sequences and launching hundreds of clinical trials—what The New York Times called a “global collaboration unlike any in history.” The vaccine race involved transnational networks of researchers, foundations, and businesses, all motivated by different incentives yet working together for a common cause.

Still, with the rise of China, the fraying of the postwar liberal international order, and the drawbridge-up mentality accelerated by the pandemic, realpolitik is back in vogue, leading some to propose recentering international relations on a small group of powerful states. Although it is easy to caricature proposals for a world run by a handful of great powers as the national security establishment pining for a long-gone world of cozy backroom dealing, the idea is not entirely unreasonable. Network science has demonstrated the essential value of both strong and weak ties: small groups to get things done and large ones to maximize the flow of information, innovation, and participation.

Stay informed.

In-depth analysis delivered weekly.

Even if states could create a modern-day version of the nineteenth-century Concert of Europe, however, it would not be enough to tackle the hydra-headed problems of the twenty-first century. Threats such as climate change and pandemics transcend national jurisdictions. In the absence of a true global government, the best bet for guaranteeing the world’s security and prosperity is not to limit the liberal order to democracies but to expand it deeper into liberal societies. There, civic, educational, corporate, and scientific actors can work with one another—and with governments—in ways that enhance transparency, accountability, and problem-solving capacity.

Leaders do not face a binary choice between the state and society. Global problem solving is a both/and enterprise. The task is thus to figure out how best to integrate those two worlds. One promising approach would be to identify the many actors working on a specific problem (say, infectious disease) and then connect the most effective participants and help them accomplish clear goals. “We do not need new bureaucracies,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres has written. “But we do need a networked multilateralism that links global and regional institutions. We also need an inclusive multilateralism that engages businesses, cities, universities and movements.”

It is a dark time for global politics. States are adapting to a world of multiple power centers and complex issues that require coordination at every level of society. Four years of erratic, personality-driven leadership in the United States under President Donald Trump, moreover, have left the liberal order in tatters. To repair it, leaders need to tap the talent and resources outside the state. Humanity cannot afford to go back to a world in which only states matter.

THE CASE FOR EXPANSION

States create international orders to, well, establish order—that is, to fight chaos, solve problems, and govern. The liberal international order is a subset of this idea, a set of institutions, laws, rules, procedures, and practices that shaped international cooperation after World War II. Its purpose was to facilitate collective action by regularizing decision-making processes, developing shared norms, and increasing the reputational costs of reneging on commitments. The institutions that form part of that order—the UN system, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, NATO, and the precursor to the EU, the European Economic Community—served that purpose reasonably well for decades.

But the world cannot successfully address twenty-first-century threats and challenges, such as climate change, pandemic disease, cyberconflict, and inequality, without mobilizing a new set of actors. Existing institutions, although valuable, were built for a world of concentrated power, in which a handful of states called the shots. Today, power is much more diffuse, with nonstate actors strong enough to both create international problems and help solve them. Accordingly, the current order needs to expand not by differentiating between various kinds of states but by making room for new categories of nonstate actors.

Take the response to the pandemic. Unilateral action by national governments was often decisive in curbing the disease. Implementing social restrictions, closing borders, and providing emergency economic relief saved lives. Despite all the criticism they have received, international organizations were also essential. The World Health Organization was the first body to officially report the outbreak of a deadly novel coronavirus; it issued technical guidance on how to detect, test for, and manage COVID-19; and it shipped tests and millions of pieces of protective gear to more than 100 countries.

If humanity is to survive and thrive, it cannot go back to a world in which only states matter.

Also critical, however, were many other actors outside the state. As many governments promulgated false or politically biased information about the new coronavirus and its spread, universities and independent public health experts provided reliable data and actionable models. Philanthropies injected massive amounts of money into the fight; by the end of 2020, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation had donated $1.75 billion to the global COVID-19 response. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, a global vaccine-development partnership of public, private, and civil society organizations, raised $1.3 billion for COVID-19 vaccine candidates, two of which, the Moderna vaccine and the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, are already being administered to the public.

Officials below the national level also played a vital role. In the United States, where the federal government’s response was indecisive and shambolic, governors convened regional task forces and together procured supplies of ventilators and protective equipment. Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire philanthropist and former New York City mayor, provided funding and organizational and technical assistance to create a contact-tracing army in the city. Apple and Google partnered to develop tools that could notify smartphone users if they came into contact with people infected by the virus. Serious planning on when and how to reopen the U.S. economy was first done not in the White House but by governors and a CEO task force convened by the nonprofit the Business Roundtable. The first large-scale antibody study to determine the prevalence of the virus in the United States was conducted not by the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention but by California universities, an anti-doping research group, and 10,000 employees and players of Major League Baseball.

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic is only one example of how global actors, not states alone, drive solutions to complex problems. Although it would have been preferable had efficient central governments organized a coherent response to the pandemic, the distributed response on the part of others demonstrated just how much problem-solving talent exists outside the state. Moreover, as some countries become more nationalist, parochial, and captured by special interests, opening up the international order to global actors is the best way to reform the order in the absence of a major state-led initiative.

GROWING NETWORKS

The activity of global actors working on a given problem, such as COVID-19, is difficult to map, much less manage. But it is also here to stay. As the scholar Jessica Mathews first noted in Foreign Affairs in 1997, powers once reserved for national governments have shifted substantially and inexorably to businesses, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations. Later that same year, one of us (Anne-Marie Slaughter) noted, also in these pages, the emerging “disaggregation of the state” into its component executive, legislative, judicial, and subnational parts. Regulators, judges, mayors, and governors were already working together in “government networks” that provided a parallel infrastructure to formal international institutions. This phenomenon has only grown more pronounced in the intervening two decades.

Still, nation-states will not disappear, nor even diminish in importance. Many governments possess political legitimacy that global actors often lack. Populist leaders have also demonstrated both the capacity to reassert traditional conceptions of sovereignty and the appeal of that strategy to many of their citizens. Trump single-handedly dismantled many of the signature foreign policy achievements of the Obama administration: he withdrew from the Paris climate agreement, torpedoed the Iran nuclear deal, and reversed the opening to Cuba. Autocrats in China, the Philippines, Russia, and Turkey have consolidated power and control, leading observers to bemoan a return to the era of the strongman. Where democracy is retrenching, however, it is often mayors, governors, businesspeople, and civic leaders who offer the strongest resistance. These actors prize and benefit from an open, democratic society.

The geography of global economic power, moreover, is also shifting in favor of nonstate actors. Five giant technology companies—Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft—have a combined market capitalization of roughly $7 trillion, greater than the GDP of every country except China and the United States. Even if governments reined in or broke up those five, scores of other companies would have more economic resources than many states. A similar shift is evident when it comes to security. As 9/11 made clear, some of the most potent national security threats emanate from organizations unaffiliated with any state. Even public service delivery is no longer the sole remit of governments. Since 2000, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, has helped immunize more than 822 million children in the developing world.

This transformation is partly the product of global connectivity. Never before has it been so easy to communicate, organize, and conduct business across national borders. In 1995, 16 million people used the Internet; in 2020, 4.8 billion did. Nearly 1.8 billion people log on to Facebook every day, a population larger than that of any single country. World trade as a percentage of global GDP is double what it was in 1975. According to one estimate, the number of treaties deposited with the UN grew from fewer than 4,500 in 1959 to more than 45,000 50 years later. In 1909, there were 37 international organizations; in 2009, there were nearly 2,000.

MAPPING THE NETWORKED WORLD

The world of global networks is a messy and contested space. International networks committed to ending climate change, promoting human rights, and fighting corruption exist alongside those bent on perpetrating terrorist attacks or laundering money. But COVID-19 has shown that successfully responding to contemporary challenges requires mobilizing global actors.

One way to marshal these forces is to expand the liberal order down. The goal should be a horizontal and open system that harnesses the power and efficacy of both governments and global actors. The pillars of this order might be called “impact hubs”: issue-specific organizations that sit at the center of a set of important actors working on a particular problem—coordinating their collective work toward common, clearly measurable goals and outcomes. A hub could be an existing international or regional organization, a coalition of nongovernmental organizations, or a new secretariat within the UN system specifically created for the purpose.

Gavi is the clearest example of this hub-based approach. The Gates Foundation helped found Gavi in 2000 as an alliance of governments, international organizations, businesses, and nongovernmental organizations. Its small secretariat is charged with a wide array of vaccine-related functions, from research to distribution, all under the eye of a 28-person board of public, private, and civic representatives. The founders of Gavi designed it as a new type of international organization, one that sought to be representative, nimble, and effective all at the same time. The result is far from perfect, but it has enormous advantages. Purely governmental organizations are often paralyzed by politics, and purely private or civic networks are invariably interested in pursuing their own interests.

Delivering COVID-19 vaccines in Amazonas state, Brazil, February 2021

Bruno Kelly / Reuters

In most areas of global problem solving, however, the challenge is not too few actors but too many. The goal is to identify the most effective and legitimate organizations in a particular area and link them to a hub that has both the funds and the authority to make a difference. Too much connection can be as bad as too little: the bigger the meeting, the harder it is to reach consensus and take action. Moreover, formal inclusion often means informal exclusion: when nothing gets done in the meeting, lots of action takes place among smaller groups in the lobby.

To avoid that outcome, would-be architects of a new global order should begin by mapping the networked world. A good place to start would be to look at the actors working on each of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—targets the world has agreed must be met by 2030 to achieve global peace and prosperity. The relevant actors include UN special agencies and affiliates; regional groups such as the European Union and the Organization of American States; corporations such as Coca-Cola, Siemens, and Tata; large philanthropies such as the Gates Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the Aga Khan Foundation; and research centers, private institutes, think tanks, and civic and faith groups. Mapping these actors and the connections between them would reveal the most important centers of activity and provide a starting point for figuring out where to locate or support a hub.

HUBS AND SPOKES

With networks mapped, leaders would then need to offer incentives to spur the designation or creation of the hubs. One way to do this would be to use challenges issued by international organizations, philanthropies, or groups of governments. The MacArthur Foundation’s 100&Change challenge, for instance, offers a $100 million grant to fund a single proposal that “promises real and measurable progress in solving a critical problem of our time.”

A properly designed challenge could encourage the formation of powerful hubs by triggering a natural growth process that network science calls “preferential attachment.” In all sorts of networks—biological, social, economic, political—the nodes that already have the most connections attract the greatest number of new connections. Within international relations, the UN is a useful example of this phenomenon. Initiatives and institutions often grow out of the UN because nearly all countries are already a part of its structure and because it has a record of credibility and expertise.

The UN should, however, pursue a more deliberate strategy to ensure that its many programs, commissions, and sub-organizations become problem-solving hubs. The secretary-general could, for example, connect a global network of mayors and governors to the UN Refugee Agency to help with refugee resettlement. Or, to combat climate change, the UN Environment Program could work with the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, a partnership between Bloomberg Philanthropies and the European Union that has brought together more than 7,000 local executives.

An expanded liberal order can harness and shape networks from every sector of society.

For those issues on which actors view the UN as too big, bureaucratic, or divided for effective action, regional organizations, informal groups, or existing public-private coalitions could serve a similar purpose. The point, however, is not simply to create partnerships and coalitions—the world is awash in them already. It is to create a stronger and more participatory order. Over time, the messy spaghetti bowl of global networks could evolve from a distributed structure with no hubs, or countless small hubs, into a more rationalized structure, one that has fewer but bigger hubs.

An effective global order also needs to be judged by its practical results, with clear metrics that incentivize competition and investment. Here, impact hubs offer an enormous opportunity to compare progress across different organizations, alliances, coalitions, and networks. Some organizations are already developing standardized metrics of progress. Impact investing—whereby investors seek not just financial returns but also environmental, social, and governance returns—is an enormous and fast-growing field. Just as traditional investors look to economic indicators such as profit margins, impact investors rely on concrete indicators to guide their choices, such as carbon emissions or school enrollment.

Leaders can and should apply similar metrics to the work of international institutions. Imagine a global impact metrics organization, comparable to the International Organization for Standardization, that rated global impact hubs in terms of the progress they were making toward achieving a particular SDG. However they were organized, reliable metrics would create a uniform way of assessing the actual contributions of different groups and hubs. In challenge competitions, the networks that were measurably more effective would prevail, which would then put them in a position to attract more people, funds, and connections, creating a virtuous circle.

The broader result would be a flexible, ever-changing system, one that would be more responsive and effective than the current order. It could meet the planet’s challenges while allowing for important variation at the local and national levels.

A NEW LIBERAL ORDER

As children pore over maps and globes, they learn to see a world neatly divided into geographic containers, brightly colored shapes separated by stark black lines. Later, they come to understand that although those borders are real, guarded by fences, walls, and officials, they are only one way of visualizing the international system. Satellite pictures of the world at night show clusters and ribbons of light, depicting the riotous interconnectedness of humanity in some places and the distant isolation of others.

Both of these images signify something relevant and important. The former portrays the state-based international order—visible, organized, demarcated. The latter illustrates the tangled webs of businesses, civil society organizations, foundations, universities, and other actors—an evolving, complex system that, although harder to conceptualize, is no less important to world affairs. The two exist side by side or, more precisely, on top of each other. The great advantage of the state-based order is that it has the legitimacy of formal pedigree and sovereign representation, even if it is often paralyzed and ineffective at solving important problems. The global order, by contrast, has the potential to be far more participatory, nimble, innovative, and effective. But it can also be shadowy and unaccountable.

If leaders bring together parts of both systems in a more coherent vision of a liberal order, the United States and its allies could build the capacity necessary to meet today’s global challenges. An expanded liberal order could harness networks of people, organizations, and resources from every sector of society. The existing institutions of the liberal, state-based order could become impact hubs. The result would be a messy, redundant, and ever-changing system that would never be centrally controlled. But it would be aligned in the service of peace and prosperity.

To read the original piece from Foreign Affairs, please click here

ANNE-MARIE SLAUGHTER is CEO of New America and former Director of Policy Planning at the U.S. State Department.

GORDON LAFORGE is a Senior Researcher at Princeton University and a lecturer at Arizona State University’s Thunderbird School of Global Management.

February 19, 2021

The Trade Policy Collision of Our Times: China’s Subsidies Encounter Abba Lerner and David Ricardo

This note takes a contrarian position on the significance of China’s subsidies, which are generally viewed as intractable and damaging to the rules-based system. It considers the implications of Lerner Symmetry for the aggregate effect of China’s subsidies and the implications of comparative advantage for the differential effects across industries, in a context where the effective differential tax burdens are unknown, as indeed is also the case with differential effects of tax and subsidy regimes in the rest of the world. It concludes that the net effect of China’s subsidies is much less than commonly supposed and that differential effects that may be damaging can be handled, as they have been in the past, through tools available under the WTO Agreement.

SSRN-id3789391

To read the original paper from SSRN, please click here

February 17, 2021

Understanding US-China Decoupling: Macro Trends and Industry Impacts

Conceived in 2019, this study seeks to illuminate the costs of decoupling for the United States. The analysis has been complicated over the past year by a shifting landscape. Tensions between the U.S. and China have grown in the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak, triggering a broader debate about supply chains, reshoring, and resilience. In truth, because of the many variables at play, it is beyond the capacity of economics to deliver a precise answer regarding the costs of decoupling. Nonetheless, this study offers what we believe is a valuable perspective on the magnitude and range of economic effects that the Biden administration should consider as it weighs its policy agenda with China. The study highlights the potential costs of decoupling from two perspectives: the aggregate costs to the U.S. economy and the industry-level costs in four areas important to the national interest.

Key findings of our assessment of the aggregate costs of decoupling to the U.S. economy include the following:

In the trade channel, if 25% tariffs were expanded to cover all two-way trade, the U.S. would forgo $190 billion in GDP annually by 2025. The stakes are even higher when accounting for how lost U.S. market access in China today creates revenue and job losses, lost economies of scale, smaller research and development (R&D) budgets, and diminished competitiveness.

In the investment channel, if decoupling leads to the sale of half of the U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) stock in China, U.S. investors would lose $25 billion per year in capital gains, and models point to one-time GDP losses of up to $500 billion. Reduced FDI from China to the U.S. would add to the costs and—by flowing elsewhere instead—likely benefit U.S. competitors.

In people flows, the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the economic impact from lost Chinese tourism and education spending. If future flows are reduced by half from their pre-COVID levels, the U.S. would lose between $15 billion and $30 billion per year in services trade exports.

In idea flows, decoupling would undermine U.S. productivity and innovation, but quantification in this regard is difficult. U.S. business R&D at home to support operations in China would fall and companies from other countries would reduce R&D spending related to their China ambitions in the U.S. The longer-term implications could include supply chain diversion away from U.S. players, less attraction for venture capital investment in U.S. innovation, and global innovation competition as other nations try to fill the gap.

In terms of industry-level costs, we find the following:

For the U.S. aviation industry, decoupling would mean reduced aircraft sales resulting in lower U.S. manufacturing output, falling revenues for the firms involved, and thus U.S. job losses and reduced R&D spending—leading to diminished U.S. competitiveness. We estimate that a complete loss of access to China’s market for U.S. aircraft and commercial aviation services would create U.S. output losses ranging from $38 billion to $51 billion annually. Cumulatively, lost market share impacts would add up to $875 billion by 2038.

For the U.S. semiconductor industry, forgoing the China market would mean lower economies of scale and R&D spending—and a less central role in the full web of global technology supply chains. Decoupling would prompt some foreign firms to “de-Americanize” their semiconductor activities, putting to the test whether that is possible and further motivating China to seek self-sufficiency. Lost access to Chinese customers would cause the U.S. industry $54 billion to $124 billion in lost output, risking more than 100,000 jobs, $12 billion in R&D spending, and $13 billion in capital spending.

For the U.S. chemicals industry, decoupling would mean a smaller U.S. share in China’s growing market, diversification by China and others from U.S. suppliers, lost competitiveness, and lower R&D spending. This decrease would offset the newfound competitive advantages the U.S. enjoys from lower feedstock costs, thanks to improved extraction technologies. From the imposition of tariffs alone, the potential cost ranges from $10.2 billion in U.S. payroll and output reductions and 26,000 lost jobs to more than $30 billion in output losses and nearly 100,000 lost jobs.

For the U.S. medical devices industry, decoupling would mean the added cost of reshoring supply chains and restricted product and intermediate input imports from China, along with retaliation against U.S. exports by Beijing. Abandoned market share in China would go to competitors, boosting their economies of scale and handing them future revenue from the market in China, where both rising incomes and an aging population are driving demand for medical devices. U.S. lost market share is valued at $23.6 billion in annual revenue, amounting to lost revenue exceeding $479 billion over a decade.

These estimations are derived from economic models of “normal” before the COVID-19 pandemic; the macroeconomic assumptions about future supply and demand that such models depend on must now be viewed with great skepticism. Moreover, they explore only the economic welfare effects: they do not attempt to price in the costs or benefits to U.S. security, which is a critical factor in the rethink of engagement with China. But the analysis does point to a number of important takeaways for U.S. policymakers, even with the caveats about the limits of economic modeling amid a global disruption:

First, data analysis is critical to policymaking. China policy requires economic impact assessment, cost-benefit analysis, and a process of public debate and discovery.

Second, even based on our rough assessment, we can see that the costs of anything approaching “full” decoupling are uncomfortably high. Alternative approaches—including mitigation and in many cases forbearance—would complement any decoupling scenario.

Third, many elements merit inclusion in a comprehensive U.S.-China policy program, from promoting industry and innovation and technology to preserving the rules-based, open market order and its institutions, and protecting systemically and strategically important assets and industries from threats. In the policy reengineering to come, the central role of market forces in determining winners, and governments’ finite capacity to redistribute resources to ease the process, must be respected.

Finally, working with like-minded partners on a plurilateral basis to harmonize regulatory approaches in priority areas and to take coordinated actions that address shared concerns over China’s practices is essential to minimizing the costs to the U.S. economy and preventing the erosion of U.S. comparative advantage that would occur if decoupling policies are implemented solely on a unilateral basis.

024001_us_china_decoupling_report_fin

To view the original report by the RHG, please click here.

February 10, 2021

ALI’s A Global Digital Strategy for America: A Roadmap to Build back a More Inclusive Economy, Protect Democracy and Meet the China Challenge

ALI’s A Global Digital Strategy for America: A Roadmap to Build back a More Inclusive Economy, Protect Democracy and Meet the China Challenge is a comprehensive roadmap to enable the United States to be a digital leader in the 21st century.

Click here to read the report , or here to read an executive summary .

The report asserts that this new global digital strategy must include two interrelated pillars: Investing in America and Leading Globally. At home, it calls for landmark investments in digital training and connectivity, the development of a digital governance regime, and measures to upgrade America’s technological competitiveness among other topics. The report emphasizes that these investments must come with implementation of diversity, equity and inclusion policies to ensure that the benefits are widely shared among all Americans.

To lead globally and address the challenge posed by China’s growing technological power, the report calls for increases in U.S. federal research and development, immigration reform, along with a “Digital Marshall Plan” for developing countries to level the playing field for American internet and communications workers and businesses competing abroad with Chinese companies benefitting from subsidized financing, while supporting sustainable development. It also calls for moving away from the go-it-alone, nationalist approach of recent years, instead repairing relationships with U.S. allies to build a foundation for global digital governance that embraces democracy, accountability and transparency and developing a coordinated approach to addressing China’s policies.

ALI++GDSA++Full+Report++Rev+02.22.21

To view the original report by the ALI, please click here.

February 8, 2021

Anatomy of a flop: Why Trump’s US-China phase one trade deal fell short

The Biden administration plans to review the phase one trade agreement President Donald Trump forged with China in late 2019. Good. Much of the deal was a failure. Its centerpiece was China’s pledge to buy $200 billion more of US goods and services split over 2020 and 2021.

According to evidence from the deal’s first year, China was never on pace to meet that commitment, with the economic devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic only partly to blame. Attempting to manage trade—to meet Trump’s objective of reducing the bilateral trade deficit—was self-defeating from the start. It did not help that neither China nor the United States was willing to deescalate their debilitating tariff war.

The phase one deal should not be ripped up, however. Several elements are worth keeping and building upon—such as China’s commitment to reduce nontariff barriers related to food safety and open up to foreign investment. China’s agreeing to crack down on intellectual property violations and the forced, insufficiently compensated, transfer of American technology will also prove beneficial if enforced.

But the dubious policy objective of reducing the bilateral trade deficit—the heart of Trump’s phase one deal—should be scrapped. The purchase commitments only sowed distrust in the very same like-minded countries with which the new US administration must work to tackle their mutual concerns involving China.

COMPARING CHINA’S PURCHASES OF PHASE ONE GOODS IN 2020 WITH 2019 IS IRRELEVANT FOR THE LEGAL AGREEMENT

China actually did import more phase one goods from the United States in 2020 compared with the previous year—imports were 13 percent higher (figure 1). That was also much better than the flat growth of China’s imports of the same goods from the rest of the world.

While economically meaningful, both comparisons, however, are irrelevant for the phase one legal agreement. US exports to China in 2019 were extraordinarily low, in part because China imposed retaliatory tariffs in response to Trump’s trade war. US exports had declined by 10 percent in 2018 compared with 2017, shrinking by another 8.5 percent in 2019. Thus, under the threat of continued tariff escalation, the Trump administration convinced Beijing to commit to purchasing an additional $200 billion of US goods and services, in prescribed amounts split over 2020 and 2021, on top of the baseline of 2017 trade flows—not 2019.

Relative to that precise legal commitment, US exports of phase one products to China in 2020 failed spectacularly—falling more than 40 percent short of the target (figure 2).

US MANUFACTURING SUFFERED THROUGHOUT THE TRADE WAR AND HAS NOT RECOVERED

President Trump cast his trade policies as designed to help American manufacturing, citing China’s large bilateral trade surplus in goods as a problem. He also complained that Beijing was forcing US companies to turn over their technology and manufacture in China instead of exporting from America. Other targets of his ire were China’s higher tariffs on cars and its subsidies to steel and aluminum, which squeezed American companies out of export markets. Though some of the policy complaints were valid, Trump’s approach of starting a trade war and then settling it with a demand for purchase commitments backfired.

US manufacturing exports to China, which had nearly doubled between 2009 and 2017, flattened in the second half of 2018 and fell by 11 percent in 2019 (figure 3). This was partially a result of Chinese retaliation against Trump’s tariffs. But in the first year of the phase one agreement, US manufacturing exports continued to suffer, declining another 5 percent. Overall, they fell 43 percent short of the legal commitment for 2020, remaining more than 14 percent below pre–trade war levels. Because manufacturing constituted 70 percent of the value of all goods covered by the purchase commitments, this shortfall essentially guaranteed that the total targets would disappoint.

The US auto sector provides an excellent illustration of how even temporary trade war tariffs can inflict long-term damage. By 2017, China had become the second largest export market for American vehicles. Then, in July 2018, China retaliated with a 25 percent tariff on US autos. (In a savvy economic maneuver, it simultaneously lowered its auto tariff on imports from the rest of the world.) US exports to China fell by more than a third (see figure 3). Tesla accelerated construction of a new plant in Shanghai, arguing that Trump’s tariffs on auto parts, China’s retaliation on cars, and the resulting uncertain trade picture, made it no longer competitive to manufacture electric vehicles destined for China in the United States. For similar reasons, BMW shifted some production destined for China out of South Carolina. By the end of 2020, US auto exports had still not recovered.

Aircraft provides another cautionary tale about the limits of the purchase commitment approach to policymaking. Boeing had been a large historical exporter to China, and aircraft did not face Chinese retaliation during the trade war. Yet, following two crashes of Boeing’s 737 MAX airplane, sales declined from over $18 billion in 2018 to less than $11 billion in 2019. (The model was grounded globally between March 2019 and December 2020, and Boeing shut down production between January and May 2020.) In April 2020, China canceled purchase orders for undelivered planes. US aircraft exports in 2020 were only $4.6 billion, less than one-fifth of the estimated target.

Semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment provide a different lesson. The high-tech sector’s exports outperformed their estimated targets in 2020, also for reasons likely unrelated to the phase one deal’s legal commitments. In 2019 and 2020, the United States announced it would soon limit exports of semiconductors and equipment, citing national security concerns. Exports accelerated in part because Chinese buyers such as Huawei and SMIC reportedly stockpiled in 2020, anticipating that US export control policy would soon cut them off.

Also on the (export) bright side were US sales of medical products to China in 2020. Pandemic-induced demand likely helped growth continue despite the otherwise challenging economic environment.

US AGRICULTURE ALSO SUFFERED, BUT RECEIVED SUBSIDIES, THEN RECOVERED

China has long been an important market for US agricultural exports such as soybeans. US exports to China through 2017 remained strong, though slightly lower than the peak years of 2012–14, driven in part by a global increase in certain commodity prices, including corn and wheat.

But as with manufacturing, the trade war devastated US agricultural sales to China. Exports were cut in half in 2018, with 2019 levels remaining nearly 30 percent lower than in 2017 (figure 4). The Trump administration responded by dishing out tens of billions of dollars of taxpayer-funded federal subsidies to farmers in 2018 and 2019, a step it never took for the manufacturing sector. As a result, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimated that American farm income—subsidized by the government—was 11 percent higher in 2019 than 2017, achieving its highest level since 2014.

Overall, China did ramp up farm purchases in 2020 and by September was back on pace to reattain 2017 levels. Nevertheless, US agricultural exports ended up both 18 percent short of the 2020 legal commitment and considerably lower than the Trump administration’s political aspirations. The Trump administration touted the deal as just the start of what China would do to help US farmers, boastingChina had agreed to “strive” to buy $5 billion more per year on top of the already hefty purchase commitments. In 2020, China did not.

Soybeans had been nearly 60 percent of US farm exports to China prior to the trade war and one of the first products China hit with 25 percent retaliatory tariffs. US exports fell from $12 billion in 2017 to $3 billion a year later, as China shifted purchases toward Brazil and Argentina. Despite President Trump’s repeated assurances beginning late in 2018 that China would soon be “back in the market” for soybeans that American farmers were being forced to stockpile in record amounts, 2019 sales also remained more than a third lower than in 2017. Part of China’s reduced demand for the animal feed in 2019 derived from a devastating outbreak of African Swine Fever that cut the world’s largest pig herd by 40 percent. US soybean exports picked up again only in 2020, reaching pre–trade war levels (though falling short of the estimated target), as the Chinese pig herd recovered.

Consider pork. China had begun to import more pigmeat from the United States in 2019 to deal with its local pork shortages, even before the phase one agreement was signed. The shortage was so bad, China’s pork imports from the rest of the world in 2020 were also more than 500 percent higher than 2017 levels.

A few other US farm exports also beat their estimated targets in 2020, including corn and wheat. Here, Beijing began complying with a 2019 World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement ruling against its unfilled tariff rate quotas; compared with 2017, China’s imports from the rest of the world in 2020 increased by more than 340 percent for corn and 280 percent for wheat. US cotton sales to China also improved in 2020, and sorghum recovered from the effects of trade war tariffs.

But many other food products did not recover. US lobster exports to China remained 18 percent lower in 2020 than 2017. Beijing both imposed tariffs on US lobster during the trade war and encouraged Chinese consumers to shift to other suppliers by lowering tariffs on lobster from Canada and other countries. (China’s lobster imports from the rest of the world increased by nearly 250 percent in 2020 compared with 2017 levels.) Maine’s lobster industry suffered but was ineligible for the tens of billions of dollars of USDA trade war payments of 2018 and 2019. The Trump administration granted it subsidies only in the immediate runup to the 2020 election.

THE ENERGY COMMITMENTS WERE A RIDDLE

Energy made up only 8 percent of the total goods covered by the phase one agreement yet is also characterized by contradictions. US energy exports to China performed the worst of the three goods sectors (figure 5), reaching less than 40 percent of the 2020 legal commitment. Low oil prices hampered export commitments measured in dollars, not volume (e.g., barrels of oil). On the other hand, the export performance of both crude oil and liquefied natural gas was considerably higher in 2020 than even 2017 levels, as each started from a very low pre–trade war baseline.

Yet, the extremely large energy purchase commitments in the phase one agreement raise at least two additional questions for policymakers. First is legal good faith. As Bloomberg reported, only after the agreement was signed did the administration learn from the US industry that it lacked production capacity to fulfill the targets. Can the consumer be found at fault for insufficient purchases if the American industry lacked short-run ability to provide the supplies?

Second is climate change concerns. The unrealistic targets were only for crude oil, liquefied natural gas, coal, and refined products. The Trump administration did not share climate concerns. But President Joseph R. Biden Jr. rejoined the Paris Agreement on climate change on day one of his administration and has prioritized climate change mitigation, which could have implications for fossil fuel exports.

THE TRADE WAR AND PHASE ONE AGREEMENT IN THE MACROECONOMIC CONTEXT

Did the COVID-19 pandemic doom the phase one deal? The United States fell into recession, with GDP contracting by 3.5 percent in 2020. China was the first country hit by the pandemic, yet its economy recovered both more quickly and more robustly than most, with GDP expanding 2.3 percent in 2020. And according to World Trade Monitor, China’s imports reached prepandemic levels by June; the rest of the world’s trade recovered only near the end of 2020.

We will also never know, of course, what the world economy would have looked like without the trade war and phase one agreement. But what if US exports in 2018, 2019, and 2020 to China of phase one products had grown at the same pace as China’s imports of those same goods from the world? (China’s imports from the United States and the rest of the world grew roughly in tandem over 2009–17; see again figure 1.)

Without the US-China trade war, US exports to China would have ended up roughly 19 percent higher than actual 2020 levels (figure 6). The United States would also not have suffered those export losses—US sales to China would have been $29 billion (33 percent) higher in 2018 and $34 billion (43 percent) higher in 2019 than actual levels. Without the export losses, American taxpayers would also not have needed to fund tens of billions of dollars of farm subsidies.

Looking more broadly, the trade war was costly. As economists have documented extensively, the tariffs raised prices and hurt American consumers. American companies (not just exporters) faced higher input costs because of the tariffs, hurting competitiveness and reducing their employment and sales. A handful of sectors and workers may have benefited, but the overall damage to the US economy was inarguable.

THE LINGERING PUZZLE OF THE UNCOVERED PRODUCTS

Oddly, the purchase commitments in the phase one agreement did not cover 27 percent of US goods exports to China in 2017. China had little incentive to buy such goods from the United States in 2020, as the purchase targets would not be credited.

Unsurprisingly, US exports of uncovered products to China performed even worse than covered products (see again figure 6). The Trump administration may have thought them unimportant—indeed, nine of the top 20 uncovered products by value included the words “waste” or “scrap” or “not elsewhere specified or indicated” in their descriptions. But declines in these exports simply offset one-for-one any export increase in covered products. Their omission from the deal remained a mystery.

THE UNITED STATES NEEDS A NEW CHINA POLICY

The lesson from year one of the US-China agreement is that purchase commitments did not work. Looking ahead to year two, some products that performed well last year could fall short in 2021. Will China continue to accelerate soybean purchases, once its stockpiles have been replenished? Will it import as much pork, once its domestic herd has recovered? Will it be cut off from American semiconductors and equipment as US export controls start to bind? Will it demand less American cotton, since the January 13, 2021 ban on US imports from Xinjiang means more domestic cotton is now available in China? As part of its decarbonization policy, will the Biden administration seek cuts in carbon-intensive energy production and exports?

The phase one agreement was never the long-term fix to what ails the US-China trade relationship. But attempting to manage trade with purchase targets and an intention to reduce the bilateral deficit is the wrong approach. It distracts from the engagement necessary to address the costly incompatibilities of the Chinese economic system with the more market-oriented economies of the United States, European Union, Japan, and other like-minded countries.

The other positive parts of phase one—such as China’s removal of technical barriers to trade, baby steps of market-oriented reform, and additional market access—can be a foundation for future progress. For example, the United should press for more Chinese commitments to permanently eliminate the retaliatory tariffs on US exports and bind its significant most favored nation (MFN) tariff reductions of 2018 and 2019. The Biden trade team should look at the European Union’s recently signed EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). It achieved many of the same things the United States attained with China in the phase one deal, including new financial services market access and some Chinese commitments not to forcibly transfer technology—an achievement won without the costs of a trade war.

Indeed, the European Union’s export performance with China is humbling. Even limiting focus to America’s priority products covered by the phase one agreement, China’s imports from the EU ended up 21 percent higher in 2020 than 2017 (figure 7). China’s imports from the United States ended up 8 percent lower in 2020, in addition to all the losses US exporters suffered in 2018 and 2019.

Yet, even with CAI, the Europeans learned that core issues with China cannot be tackled bilaterally. Sabine Weyand, director-general for trade, stated recently that “what we are looking at is to work with the US, Japan, but also other like-minded countries to agree on an update of the WTO rulebook.” That includes rules for industrial subsidies, a thorny issue neither the United States or the European Union was able to address with China through their respective deals.

In other words, only a group of countries working together and sharing the burden will be able to make progress with China. For the United States, the purchase commitments both worked against collaboration and reflected an approach divorced from economic reality.

To read the original report from PIIE, please click here

Chad P. Bown, Reginald Jones Senior Fellow since March 2018, joined the Peterson Institute for International Economics as a senior fellow in April 2016. His research examines international trade laws and institutions, trade negotiations, and trade disputes. With Soumaya Keynes, he cohosts Trade Talks, a weekly podcast on the economics of international trade policy.

February 2, 2021

Business Confidence Survey: Positive Development for German Businesses in China and High Expectations for EU-China Investment Agreement

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Continuous Recovery of Chinese Business of German Companies

Despite Covid-related declines in turnover in the first half of 2020, 39 percent of German companies in China managed to increase their turnover and 42 percent their profits in 2020, according to the survey. In addition, in 2020, around 25% of the surveyed German companies in China managed to achieve turnover and profits roughly at the same level as in the previous year. China is the only large economy that has managed to grow -even if only by about 2 percent in 2020. German companies also benefited from this and could partially compensate for the declines in the EU and the USA due to the recovered business in China in the second half of the year.

Expectations for the upcoming EU-China Investment Agreement (CAI) are high: the companies surveyed by the German Chamber of Commerce in China and KPMG Germany stated that market access (40 percent) and equal treatment of all market participants in China (39 percent) were the main expectations for the agreement. However, the study results also showed quite positive assessments of formal market access. Compared to the previous year, fewer companies reported to fail at this first hurdle (30 percent). On the other hand, the challenges remain clearer at the indirect level. Summing up the regulatory challenges of German companies in China, administrative and bureaucratic hurdles are among the biggest obstacles: Customs regulations and procedures, obtaining the necessary licenses, the requirements of the Cyber Security Act, the Corporate Social Credit System, as well as capital transfers and cross-border payments.

Optimism for 2021 is evident: 77 percent of respondents expect their industry to perform better in China than in other markets. As a result, 72% of respondents expect rising sales in China and 56% higher profits in 2021. This is also reflected in a strong commitment to the Chinese market: Almost all companies surveyed (96%) stated that they had no plans to leave China and 72 percent planned further investments in production facilities (44%) and machinery (34%) as well as in research and development (32%). Many key industries in China are setting the course for future developments. A local presence is important to generate sales in the Chinese market, enter into local partnerships, or closely observe tomorrow’s competitors in their home market. The German companies surveyed see great business opportunities in China, especially with innovative technologies (58%) and digital solutions (51%).

To read the original report from AHK Greater China, please click here

0202_BCS_Report_web.pdf

February 1, 2021

The US–China trade war and phase one agreement

The Trump administration changed US trade policy toward China in ways that will take years for researchers to sort out. This paper makes four specific contributions to that research agenda. First, it carefully marks the timing, definitions, and scale of the products subject to the tariff changes affecting US-China trade from January 20, 2017 through January 20, 2021. One result is that each country increased its average duty on imports from the other to rates of roughly 20 percent, with the new tariffs and counter-tariffs covering more than 50 percent of bilateral trade. Second, the paper highlights two additional channels through which bilateral tariffs changed during this period: product exclusions from tariffs and trade remedy policies of antidumping and countervailing duties. These two channels have received less research attention. Third, it explores why China fell more than 40 percent short of meeting the goods purchase commitments set out for 2020, the first year of the phase one agreement. Finally, the paper considers additional trade policy actions—involving forced labor, export controls for reasons of national security or human rights, and reclassification of trade with Hong Kong—likely to affect US-China trade beyond the Trump administration.

US China

To read the originial report from PIIE, please click here

January 31, 2021

Global Trade Today is Global Value Chains

In the last 25 years global value chains have come to dominate global trade in a way surprisingly little discussed or understood. To meet the policy challenges of today and the future we need to understand the key characteristics of this new global trade and how they came about.

The OECD estimate around 70% of total trade takes place in global value chains. Using their definition as where “the different stages of the production process are located across different countries”, and considering both goods and services inputs, this may be an understatement.

The example most commonly used is the automotive sector, with 30,000 parts and associated services like satellite navigation going into one car. However there are many others. Modern primary commodity production is optimised by technology developed in other countries, diverse services and goods are frequently combined to create new product offerings, and most international business to consumer transactions are facilitated by leading global platforms.

Positively this new globalization has provided consumers with an unprecedented choice of products at affordable prices. More challengingly it has seen governments struggle with the question of how they can best influence modern trade, amid signs of a backlash and simple demands for ‘more domestic manufacturing’.

The popular global narrative that feeds such demands is one that has a traditional view of trade as a set of simple primary or manufactured goods transactions. Policymakers must move on from this narrative, making their choices, and explaining them clearly, on the basis of global value chains.

Why Global Trade Changed

The dramatic fall in the cost of transporting goods since the 1970s due to containerisation is well documented. More recently the Internet in particular has reduced the cost of transporting ideas and other services since 1990. Together these developments mean large companies can source their final products by taking their pick of the best ideas and most economic facilities from around the world. This process of breaking down final production in turn accounts for most of the 900% rise of goods trade since the mid-1980s.

Yet companies also face constraints in their choices. Complexity in operation is likely to increase risk. This is why governments seeking to attract companies have sought to offer reassurances, not always successfully, against domestic policy change. The drivers around global supply chains are thus complex, and likely to remain so.

Picturing Global Supply Chains

Global value chains use individual goods or services inputs which are in various ways processed into a finished product to a customer. The diversity of how this happens is almost endless, with no single model, and thus no single predictable response to change.

In the previously mentioned automotive case, a set of physical components are made into a car, combined with services such as car’s information systems, and sold as a single product with the possible addition of warranty or financing. Supermarkets combine products bought, and those made specifically, with services such as loyalty schemes. Both use sophisticated computer systems developed by third parties to manage stock levels and human resources. They will draw upon marketing experts, quality systems and third party contact centre providers where required.

Overall the sum of all these transactions form a complex network running across borders to constitute the majority of global trade. There is trade outside these networks, for example direct international manufacturer-to-consumer retail or transfers of precious metals, but far less than that happening within global chains. Understanding this is of vital importance in understanding a national economy.

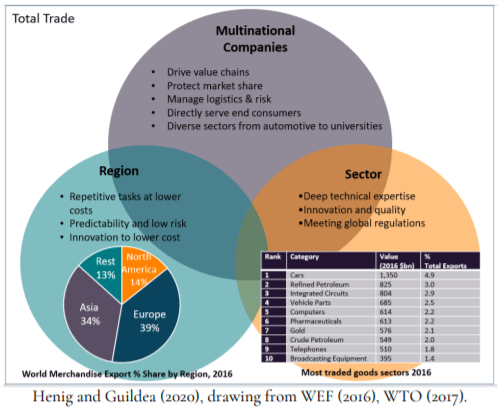

Identifying three distinct elements to the supply chains can help conceptualise this network. The large enterprises which drive the process balance their supply chains between sectoral expertise, increasingly global, and lower cost repeat production, looking first within their region if sufficiently economical.

This can be illustrated as below, noting that while modern trade is particularly concentrated in three regions, Asia (mainly East, South, and Southeast), Europe, and North America, there is a diversity of traded goods and services sectors.

Implications of Global Value Chains

Globally competitive companies must make their own decisions about how best to operate their supply chains. Governments cannot in general force them to increase domestic production, or indeed make any quick decisions. Global value chains and modern trade therefore exist largely outside the direct control of politicians, even where national champions or state owned enterprises exist. This lack of control over the economy may even influence governments to revert to more traditional views of trade in the hope this can make a difference.

Yet governments can and do influence value chain decisions. China positioned itself in the 1990s as a low cost high quality provider of complex consumer products on behalf of multinationals through various policies. European countries have sought to create specialist clusters of deep technical expertise, in the car industry, aerospace, or pharmaceuticals. Conversely new barriers to UK-EU trade are seeing some supply chains restructured without UK components.

Governments have numerous policy levers, such as trade, skills or taxation policy, but need to think carefully about the nature of modern trade in using them. President Trump’s targeting of US imports from China in the hope of stimulating domestic production failed to consider value chains. Rather it encouraged some manufacturers to transfer production to Vietnam to avoid tariffs, where such a short term move was possible, rather than set up expensive new operations in the US.

Similarly Free Trade Agreements focused predominantly on old models of trade are no guarantee of attracting greater domestic manufacturing or greater participation in supply chains. While stable and open trade relations are an important foundation, individual changes are unlikely to be significant. Similarly predictable regulatory and skills frameworks are likely to be more important than constant change. Supporting specialisms, reducing general costs for example through better infrastructure, and attracting major inward investments would then seem to be specific policies which could enhance supply chain participation.

Conclusion

Global value chains have become the predominant reality of international trade, and the factors behind their growth seem unlikely to change significantly. The ability for companies to operate globally, using the best technology and most cost efficient production, is here to stay. The implications are profound, economically and politically, as we may have already seen in the rise of populism, but equally in providing equipment and global research collaboration to fight Covid. Policy makers need to adjust their assumptions on trade accordingly, before considering what actions will be most effective in meeting their objectives.

To view the original research by the European Centre for International Political Economy, please click here.

NG-series-Paper-2

January 28, 2021

Adapting to the digital trade era: challenges and opportunities

Digital innovations are transforming the global economy. The decline in search and information costs, rapid growth of new products and markets, and emergence of new players ushered in by digital technologies have the promise of boosting global trade flows, including exports from developing countries. At the same time, digital technologies are also threatening privacy and security worldwide, while developing countries that lack the tools to compete in the new digital environment are in danger of being left even further behind.

This book from the World Trade Organization (WTO) Chairs, members of the Advisory Board and WTO Secretariat staff examines what the rapid adoption of digital technologies will mean for trade and development and the role that domestic policies and international cooperation can play in creating a more prosperous and inclusive future.

The first section identifies the challenges and opportunities posed by digital technologies to developing countries and the role of international cooperation, whether regionally or in the WTO, in addressing them. The second section discusses how countries in different developing regions view the opportunities and challenges of digital technologies and how policymakers are responding to them. The third section considers examples of how digital advances, for example the growth of e-commerce and the development of blockchain technology, may contribute to inclusive growth. The fourth and final section discusses the role of domestic policies and regional approaches to digital trade and offers some key findings.

adtera_e

To read the full report, please click here

The Longer Telegram Toward a new American China strategy

Today the Atlantic Council publishes an extraordinary new strategy paper that offers one of the most insightful and rigorous examinations to date of Chinese geopolitical strategy and how an informed American strategy would address the challenges of China’s own strategic ambitions.

Written by a former senior government official with deep expertise and experience dealing with China, the strategy sets out a comprehensive approach, and details the ways to execute it, in terms that will invite comparison with George Kennan’s historic 1946 “long telegram” on Soviet grand strategy. We have maintained the author’s preferred title for the work, “The Longer Telegram,” given the author’s aspiration to provide a similarly durable and actionable approach to China.

The focus of the paper is China’s leader and his behavior. “The single most important challenge facing the United States in the twenty-first century is the rise of an increasingly authoritarian China under President and General Secretary Xi Jinping,” it says. “US strategy must remain laser focused on Xi, his inner circle, and the Chinese political context in which they rule. Changing their decision-making will require understanding, operating within, and changing their political and strategic paradigm. All US policy aimed at altering China’s behavior should revolve around this fact, or it is likely to prove ineffectual.”

The author of this work has requested to remain anonymous, and the Atlantic Council has honored this for reasons we consider legitimate but that will remain confidential. The Council has not taken such a measure before, but it made the decision to do so given the extraordinary significance of the author’s insights and recommendations as the United States confronts the signature geopolitical challenge of the era. The Council will not be confirming the author’s identity unless and until the author decides to take that step.

The Atlantic Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution, and this paper is no different from any other in that sense.

Nonetheless, we stand by the importance and gravity of the issues that this paper raises and view it as one of the most important the Council has ever published. The Council is proud to serve as a platform for bold ideas, insights, and strategies as we advance our mission of shaping the global future together for a more free, prosperous, and secure world. As China rapidly increases its political and economic clout during this period of historic geopolitical crisis, this moment calls for a thorough understanding of its strategy and power structure. The perspectives set forth in this paper deserve the full attention of elected leaders in the United States and the leaders of its democratic partners and allies.

To read the original piece from the Atlantic Council, please click here

The-Longer-Telegram-Toward-A-New-American-China-Strategy

This paper is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations.

William Krist's Blog