William Krist's Blog, page 49

November 19, 2020

New Approaches to Supply Chain Traceability: Implications for Xinjiang and Beyond

In recent years, growing demand for sustainable sourcing and responsible manufacturing has driven efforts to establish an understanding of a product’s geographic origins and conditions of production. A key component of this has been the development of traceability systems. In an ideal world, these systems would allow companies to identify where inputs are sourced from (“origin”), which intermediaries products pass through (“chain of custody”), and the conditions in which those goods were produced at various stages of the supply chain (“conditions of production”). Knowledge about the origins and suppliers of goods—or traceability—is a key first step that then enables companies to conduct due diligence to verify the conditions of production, such as product authenticity and compliance with environmental and labor standards, including forced labor. Visibility into suppliers is needed so that appropriate due diligence can be carried out. A strong traceability system capable of meeting the expectations of the future must be capable of realizing each of these benefits and more.

While each one of these issues is important to corporations and consumers alike, some prove more difficult to tackle than others. A system that can address the issue of human rights, including forced labor, has been exceptionally difficult to design and implement. Whereas products may hold physical indicators of authenticity or sustainable farming, such as differences in quality compared to counterfeits, goods made with forced labor are often indistinguishable from their responsibly sourced counterparts. Moreover, malicious actors using forced labor often obscure their operations from outside scrutiny. A complete system, then, requires a robust methodology that is reliable even when working with partners that may be untrustworthy or uncooperative.

201116_Lehr_New_Approaches_Supply_Chain_Traceability_Implications_Xinjiang_Beyond (1)

Amy K. Lehr is director and senior fellow of the Human Rights Initiative (HRI) at CSIS. Her work focuses on human rights as a core element of U.S. leadership, labor rights, emerging technologies, and the nexus of human rights and conflict. She interfaces with civil society, government, and business, all of which have roles to play in addressing human rights.

To read the report, click here.

25th Anniversary of the WTO

The event — entitled “WTO at 25: Past, Present & Future” — comprised of a keynote speech and two panels. The first will feature a discussion among government officials, including ministers. The second will be a debate among stakeholders, including representatives from the private sector, civil society, media and academia.

WTO at 25: Past, Present & Future: Opening session

WTO: Past, Present & Future - Opening Session

Keynote Speech: Keynote speaker Guy Parmelin, Federal Councillor, Vice President of the Swiss Confederation

WTO: Past, Present & Future — The political perspective

WTO: Past, Present & Future — The political perspective

Panel 1: Senior government representatives, including at ministerial level, will discuss how the WTO has evolved over 25 years. They will share their views on the role the WTO has played in shaping their economies, consider the shortcomings of the system and what should be done to facilitate the integration of developing and least developed countries into the multilateral trading system.

WTO: Past, Present & Future — The political perspective

Soraya Hakuziyaremye, Minister for Trade and Industry, Rwanda

Dennis Shea, Deputy USTR and Ambassador to the WTO for the United States

Cheryl Spencer, Jamaica’s Ambassador to the WTO and Coordinator of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States

Wang Shouwen, Vice Minister and Deputy International Trade Representative, Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), China

Sabine Weyand, Director General, Trade, European Union

George Yeo, former Singapore Minister for Foreign Affairs and for Trade and Industry

Moderator:

Vonai Muyambo, WTO

WTO: Past, Present & Future — The stakeholders’ perspective

WTO: Past, Present & Future — The stakeholders' perspective

Panel 2: Representatives from the private sector, civil society, media and IGOs will debate how the multilateral system has served society. This will include sharing ideas on how to ensure that the multilateral trading system better reflects the needs and expectations of society and how it can be more inclusive, providing a level playing field for all, particularly the poorest countries, small business, women and youth.

WTO: Past, Present & Future — The stakeholders’ perspective

Joshua Bolten, President and CEO, US Business Roundtable

Céline Charveriat, Executive Director, Institute for European Environmental Policy

Martin Chungong, Secretary-General, Inter-Parliamentary Union

Frank Heemskerk, Secretary General, European Round Table for Industry

Soumaya Keynes, Trade and Globalization Editor, The Economist magazine

Guy Ryder, Director-General, International Labour Organization

Moderator:

Bernie Kuiten, WTO

Women Pioneers at the WTO- Video Stories

Women Pioneers at the WTO” pays tribute to women who have played a pioneering role in the activities of the WTO and the multilateral trading system over the last 25 years.

In the videos displayed here, these exceptional women tell their stories.

Messages from Civil Society, the Private Sector and International Organizations

On the occasion of the WTO’s 25th anniversary, a number of representatives of the private sector, international organizations and non-governmental organizations have provided video messages where they reflect on what the WTO and the multilateral trading system means to them. They provide their thoughts on how to ensure trade continues to support economic growth, development and job creation and what they expect from the global trading system in the future.

Videos available here.

Conversations on the WTO at 25

As the WTO turns 25, the organization takes a look at its past, present and future. Keith Rockwell, WTO spokesman, invited three former Directors-General to share their views about how the organization has evolved over the past quarter of a century and what lies ahead. Roberto Azevêdo, Supachai Panitchpákdi and Pascal Lamy shared their thoughts and reflected on their time in office.

“Conversations on the WTO at 25” with former WTO Directors-General Supachai Panitchpakdi, Pascal Lamy and Roberto Azevêdo will be screened. In these one-to-one, pre-recorded conversations with WTO Spokesperson Keith Rockwell, the former DGs reflect upon the 25 years of the WTO.

Full interviews with each of the three former WTO heads will also be available soon

For more information about the event, click here.

Trade and Integration Monitor 2020: The COVID-19 Shock: Building Trade Resilience for After the Pandemic

The 2020 edition of the Trade and Integration Monitor identifies the factors underlying recent developments in trade flows of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), examines current risks, and concludes that the current crisis is less intense than initially expected. However, the recovery remains unstable even though exports have rebounded recently.

The sudden deterioration of prices and real flows were the main explanatory factors behind the decline in the value of LAC goods exports. Services exports also began to contract for the first time since 2015. There have been some signs of improvement since June, but projections for the second half of 2020 suggest that significant risks to recovery remain.

The COVID-19 pandemic plunged the world and LAC into the most acute trade contraction since the Global Financial Crisis. Goods exports from LAC had already fallen by 2.4% in 2019 after just two years of growth. The year-on-year contraction accelerated from 3.5% in the first quarter to 27.5% in the second. In the first half of 2020, the average year-on-year variation rate was –16.0%. Unlike the trade contractions of the last decade, the main driver of the current crisis was the drop in export volumes. In real terms, the region’s external sales contracted more than global trade (–12.1% and –8.9%, respectively). Commodity markets, particularly those of energy goods, reacted quickly to the pandemic, causing a 5.2% contraction in export prices that also contributed to depressing the value of LAC’s external sales. The variation rate of exports of services from LAC moved onto negative ground for the first time since 2015, going from 1.1% growth in 2019 to a contraction estimated at 29.5% year- on-year in the first half of 2020.

Although the pandemic has not impacted trade flows as much as initially expected and relative improvement has been observed since June, the most recent trend indicators point to a slow recovery of export flows to precrisis levels. Looking ahead, there are growing risks associated with the instability of external demand as a result of new lockdowns and social isolation measures, the volatility of commodity markets, and the indirect effects of global trade tensions, as well as the forecasts of a contraction in intraregional trade, given that the region is continuing to be hard hit by the pandemic.

Although most of the contraction was explained by the drop in extraregional trade flows, the downturn in intraregional trade was more intense. Trade flows within every integration scheme contracted more than trade with the rest of the world. This intensified a trend toward intraregional trade losing relative weight that was also observed in 2019.

In the first half of 2020, the contraction in exports to the US (–19.5%), the EU (–18.6%), and, to a lesser extent, China (–1.0%) played a decisive role in LAC’s trade performance, explaining around two-thirds of the overall downturn. However, intraregional flows fell at even higher rates within all LAC blocs: –30.3% in the Andean Community, –24.6% in MERCOSUR, –24.0% in the Pacific Alliance, and –8.8% in Central America and the Dominican Republic. Similarly, a limited sample of Caribbean countries suggests that intrazone exports from the region contracted by 25.4%, excluding Guyana whose notable increase in oil exports set it apart. In MERCOSUR, the contraction in intrazone sales caused by the collapse of bilateral trade between Argentina and Brazil played a decisive role in the drop in total exports, while Brazil saw an extraordinary increase in soybean shipments to China. On balance, and in keeping with the trend that was observed in 2019, the share of intraregional trade flows in total LAC trade continued to shrink, reaching 12.8% of total trade flows, a drop of 1.2 percentage points in comparison with 2019.

Chapter 1 of this report examines the main features of the downturn in global and regional trade that has been observed since early 2018, tracks the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on trade in 2020, and assesses the balance of global economic risks. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the region’s recent trade performance, break – ing down the variation in prices and export volumes and assessing the likelihood of a trend reversal in the coming months. Chapter 3 examines the specific features of export and import flows of goods and services in different countries and subregions of LAC. Chapter 4 analyzes the downturn in intraregional trade and examines the export performance of LAC’s main integration blocs. The conclusions discuss the challenges the region must tackle in order to strengthen the participation in the post-COVID-19 global value chains. 1 The Impact of the Pandemic on Global Trade.

Trade-and-Integration-Monitor-2020-The-COVID-19-Shock-Building-Trade-Resilience-for-After-the-Pandemic

To read the full report, click here.

November 18, 2020

The Coming NEV War? Implications of China’s Advances in Electric Vehicles

China’s economy appears to have sprung back to normal. While the overall growth numbers have recovered and China has put forth an ambitious economic agenda for the next five years, optimism has also returned to the new-energy vehicles (NEV) sector, a good metric for the new economy. At the Beijing Auto Show, held in late September, automakers unveiled a dizzying 785 new models, 160 of which were electrified. There is growing speculation that China’s NEV sector is ready to burst onto the global stage and become an export powerhouse. But despite the glitzy new models, incremental progress on several fronts, and initial signs of expanding business abroad, China’s NEV sector still faces substantial roadblocks. Some are the result of continuing economic troubles, while others paradoxically are a result of gradual success. Consequently, the new wave of enthusiasm is a bit premature.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE UNITED STATES

The one upside of the ongoing domestic challenges for China’s NEV sector is a likely delay in the outbreak of a possible “NEV war” between an upstart China and the world’s dominant producers. For the immediate future, the contest will still be primarily in the Chinese market, but eventually the field of play could move to showrooms around Europe and North America and, by implication, present a new challenge to domestic automakers and their workers. To the extent these cars come equipped with automous vehicle or driver-assistance capabilities or are otherwise connected to the internet, vehicles from China could also raise national security concerns related to vehicles’ performance and passenger data.

One appropriate reaction would be defensive. Trade lawyers and officials within the U.S. Commerce Department’s International Trade Administration could sharpen their pencils in preparation for a bevy of antidumping and countervailing duty cases. And officials elsewhere in Washington will need to develop regulatory protections because of the potential national security risks related to network security, data storage, and data privacy.

But an equally if not more important response will be offensive—for U.S. industry, educational and training institutions, consumer groups, and government to collaborate in strengthening the United States’ own NEV industry from top to bottom. This means: (1) fostering design and engineering talent (which includes attracting international students and workers to the United States); (2) conducting R&D for batteries, hydrogen fuel cells, other alternative energy sources, car components, and chasis materials; (3) encouraging transportation manufacturing clusters in multiple regions; (4) investing in private and public charging infrastructure; (5) expanding incentives for producers; (6) offering larger buyer rebates to make NEVs more affordable for everyone; and (7) integrating developments in NEVs with autonomous vehicle technology, other transportation systems, and urban and regional planning.

Beyond being proactive at home, the United States’ international strategy likewise should not be purely defensive. The United States needs to be more supportive without violating its international trade commitments and copying any of China’s discriminatory practices. Washington certainly should oppose China’s unfair trade practices and any threats to our national security, but successfully developing NEVs and transportation systems requires greater coordination with other economies and in international institutions on setting technical standards, engaging in R&D, developing trusted supply chains, and protecting data.

There is no doubt China is accelerating its efforts in NEVs. If the United States is going to win this competition, it must develop and execute on its own effective playbook. And the sooner it does so, the better.

To read the full policy brief, please click here.

201113_Kennedy_NEV_War_v.5 (002)

Scott Kennedy is senior adviser and Trustee Chair in Chinese Business and Economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

© 2020 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

November 17, 2020

The 26TH Global Trade Alert Report: Collateral Damage: Cross-Border Fallout from Pandemic Policy Overdrive

Executive Summary

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic meant governments faced their second systemic economic crisis in under 15 years. This year policymaking went into overdrive as states rightly took steps to protect public health and to stabilize their national economies. The impact of those steps did not stop at national borders. Once more the world trading system faced a major stress test.

When crises happen, overwhelmed officials and policymakers try stifling concerns about trade fallout with the following knee-jerk arguments:

• Collateral damage to trading partners is inevitable at times like this.

• Crisis policy response is temporary and so poses no long-term threat to the world trading system. • No across-the-border tariff hikes (like those witnessed in the 1930s) have occurred and so trade distortions are under control.

• It is unrealistic to expect trade reform during crises.

• Trade rules should not get in the way of national crisis response.

Having documented and analysed information relating to over 2,000 policy interventions taken during the first 10 months of 2020, in this report we marshal evidence to reject every single one of these points. We also compare the policy response this year to that in 2009, during the dark days of the Global Financial Crisis. Doing so reveals there is no single crisis playbook. Governments have a choice in how they respond to crises. Once again states made dissimilar choices with different repercussions for their trading partners. Collateral damage was not inevitable. In fact, we show the fallout across nations this year was very uneven.

This report provides the most comprehensive account to date of the cross-border commercial fallout from government measures taken to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. Not every element of pandemic response had consequences for trading partners. Of those that did, not all were harmful. Governments may see themselves as responsible solely for the wellbeing of their own citizens but that doesn’t negate the fact that their actions can harm the health as well as the livelihoods of citizens of trading partners. This year has witnessed policy interventions that both sicken-thy-neighbour and beggarthy-neighbour. There has also been a substantial amount of import reform. Key findings relating to global policy dynamics affecting cross-border commerce include:

• Trade distortions implemented this year cover 13.6% of world goods trade. By contrast, trade reforms cover 8.2%.

• By 31 October 2020, a total of 2,031 policy interventions affecting international commerce were imposed by governments around the world. That total is up 74% over the same period in 2019 and 147% higher than the average for 2015-2017, the years before the United States-China trade war really kicked in.

• Only 27% (or 554) of those 2,031 policy interventions benefited trading partners.

• 37 nations saw their commercial interests benefit from 100 or more reforms in trading partners. Whereas 58 nations saw their interests harmed 100 times or more so far this year.

• This year 43 nations saw 10% or more of their goods exports face worse market access conditions. Only seven nations saw 10% or more of their goods exports enjoy better market access.

• During the first 10 months of 2020, 26 nations saw more of their goods exports exposed to better market access abroad than worse conditions. For the rest–over 170 economies—more of their goods exports faced impaired access to foreign markets than improvements.

• Overall, policy intervention during the first 10 months of this year generated a total of 10,546 positive crossborder effects for trading partners. Meanwhile, policy induced 17,252 negative spillovers.

• 110 export curbs on medical goods and medicines remain in force. 68 such curbs have no phase-out date raising the prospect of long-term scarring.

• This year 106 nations implemented a total of 240 reforms to ease the importation of medical goods and medicines.

As is the case before any G20 Leaders’ Summit, we put the track records of this group’s members under the spotlight. Here the main findings are:

• In the first 10 months of this year, together the G20 members undertook 1,371 policy interventions—1,067 of which harmed trading partners. The harmful total is up 24% on 2019 and 117% higher than the years before the trade war, 2015-2017.

• G20 members were responsible for three-quarters of both the harmful and the beneficial knock-on effects for trading partners witnessed this year.

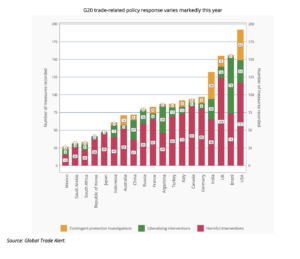

• Three classes of G20 member can be identified—four nations that implemented over 125 trade-related policies in the first 10 months of this year, three nations that implemented 33 or fewer, and the rest (see Figure).

• The policy mix employed by G20 members varied markedly. For example, Brazil undertook 156 policy interventions this year, 47% of which harmed trading partners. For its part, the UK imposed 155 measures and 80% tilted the playing field in favour of domestic firms. Remarkably, the UK’s percentage was bested by Canada, Germany, Japan, Korea, and Saudi Arabia.

• Resort to time-bound crisis intervention varies a lot too. Russia has already phased out 20% of harmful crisis intervention taken earlier this year. China is scheduled to phase out 29% of its harmful measures by the end of this year—the comparable percentages for Italy and Mexico are 32% and 26%, respectively. Overall, 47% of Mexico’s harmful crisisera intervention is time-bound, just ahead of China (46%). In contrast, over 95% of Canada, Saudi Arabia, and South Africa’s policies imposed this year that harm trading partners are not time-bound.

• This year G20 members undertook 770 General Economic Support measures (WTO terminology that captures inside-the-border policy intervention that can affect global commerce). A total of 679 of such measures involved granting different types of trade-distorting subsidies, either to firms competing in home markets or in foreign markets. The G20 is responsible for substantial subsidy-related trade fallout, affecting competitive conditions for 9.4% of world goods trade this year.

Coming at a time when the prospects for a revival of multilateral trade cooperation are improving, our evidence supports three recommendations to policymakers. First and foremost, a major shift in mindset is needed—away from the prevailing view that the world trade rule book must be effectively suspended for the duration of a crisis. This mindset has deep roots—going back to the origins of the post-war trading regime and manifests itself in what are euphemistically referred to as “flexibilities” in multilateral trade accords. In a world with extensive cross-border commercial ties, the current approach to crisis management is a recipe for the long-term scarring of the world trading system.

Keeping goods—including medical kit, medicines, and hopefully soon vaccines—flowing across borders is essential during a pandemic. More generally, open trading regimes facilitate exports, which speed up national economic recovery. A crisis management protocol should be agreed by governments to shape how they respond to crises in a way that limits harm to trading partners and keeps commerce flowing. Temporary policy intervention should be prioritised and a mechanism included to encourage the unwinding of trade distortions introduced during crises. The World Health Organization has protocols that kick in when crises occur, so why can’t the World Trade Organization?

Second, governments and international organizations need to systematically compare the state responses to this year’s pandemic and to the Global Financial Crisis so as to identify those effective policy actions that inflicted little or no harm on trading partners. Third, developing such best practices requires systematic information collection on public policy responses and their crossborder commercial fallout. The new Director-General of the World Trade Organization should strengthen that body’s monitoring and analysis functions. That monitoring needs to pay particular attention to subsidies and other General Economic Support measures. Other international organisations and independent analysts should contribute too.

GTA26disseminated

Simon J. Evenett is Professor of International Trade and Economic Development, University of St. Gallen, Switzerland; Coordinator, Global Trade Alert; and a former nonresident Senior Fellow, Economic Studies, Brookings.

Johannes Fritz is a research assistant University of St. Gallen, Switzerland.

To read the full report, click here.

© CEPR Press, 2020

November 13, 2020

Greening EU Trade

“Is trade bad for the environment?” is the simple question that was asked on July 11 to the 110 young professionals and students coming from 25 member States, who were participating to the Budapest European Agora. 40% of them answered yes. 37% answered no and 23% admitted they do not know. These results highlight the complexity of this relation. Time has come to democratise this debate and to put concrete solutions on the table.

This is all the more necessary that the 2019 elections have resulted in a rebalancing of political forces at the European Parliament which will necessitate to review the trade environment nexus at EU level for several reasons:

• environment protection featured prominently among the political signals sent by the voters;

• it is, by essence, a global public good issue, better dealt with at EU level;

• the EU is seen as having so far exercised a leadership role in this area of global governance;

• trade is one of the few really “federalised” EU competences;

• as such, it remains the main EU lever to influence the global agenda, starting with SDGs.

This is confirmed by noticeable developments since the elections, such as the new President of the Commission declaring that she is in favour of border carbon taxes (a first), or by the growing debate on the preservation of the rainforest that have surfaced as a result of the EU and Mercosur’s agreement reached after 25 years of bilateral trade negotiations.

Even if trade measures are not among the “first best solutions” to tackle environmental degradations, revisiting the EU stance in this area appears, both necessary and urgent, starting with climate change related aspects. This is also true about other issues such as biodiversity or ocean governance. It is a highly complex matter, necessitating deep analytical and technical investigations in several areas, new political debates, and search for operational

and implementable solutions.

Time to Green EU Trade Policy: But How?

190903-PP-EN-Time-to-green-EU-policy-but-how-1

Greening EU Trade Policy -2: The Economics of Trade and Environment

PP245_Verdirlecommerce2-EN_PL-GP-PLT-1

A European Border Carbon Adjustment Proposal Greening EU Trade – 3

PP_200603_Greeningtrade3_Lamy-Pons-Leturcq_EN-1

Greening EU Trade 4: How to “Green” Trade Agreements?

201109_GreeningTrade4_Lamy-et-al._EN

Climate 21 Project

The Climate 21 Project taps the expertise of more than 150 experts with high-level government experience, including nine former cabinet appointees, to deliver actionable advice for a rapid-start, whole-of-government climate response coordinated by the White House and accountable to the President.

The memos below contain the Climate 21 Project’s recommendations for 11 White House offices, federal departments, and federal agencies, as well as cross-cutting recommendations on personnel and hiring.

Importantly, the Climate 21 Project is not offering a policy agenda. Rather, the memos below contain recommendations that can help the President hit the ground running and build the capacity of his administration to tackle the climate crisis quickly with the existing tools at hand.

The recommendations are focused in scope on areas where the contributors have the most expertise. An all-of-government mobilization on climate change will require important work by additional federal departments and agencies that were not examined by the Climate 21 Project.

To view the recommendations, please click the links below:

Transition Recommendations for Climate Governance and Action

Executive Office of the President

Office of Management and Budget

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Attracting and Hiring Climate Change Talent

© 2020 Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions.

November 12, 2020

2021 Index of Economic Freedom: After Three Years of Worsening Trade Freedom, Countries Should Recommit to Lowering Barriers

Global trade freedom has fallen for the third straight year in the 2021 Index of Economic Freedom and is at its lowest level since 2006. Higher tariffs and more nontariff barriers have made trade more difficult and costly for individuals and businesses worldwide. For more than 25 years, the Index has shown that individuals in countries with higher levels of trade freedom are more prosperous and often have much higher incomes, greater food security, healthier environments, and increased political stability. To improve their trade freedom scores and the lives of their citizens, countries should seek to eliminate tariffs and nontariff barriers, enter into new free trade agreements, and remain dedicated to their World Trade Organization commitments.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

1.Global trade freedom has fallen for the third straight year and is at its lowest level since 2006 according to the Index of Economic Freedom.

2.Without a free trade leader, individuals and businesses are facing more difficult and costly barriers worldwide.

3.Countries should seek to increase their trade freedom by eliminating tariffs and nontariff barriers.

IB6026_0

Tori K. Smith is the Jay Van Andel Trade Economist Heritage’s Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies. She provides the conservative true north on free trade through her research and writing.

To read the full report, click here.

Climate 21 Project: Transition Memo for USTR

Climate change is unique among the issues facing the President, because both the effects and the policy solutions to the challenge defy neat categorization. Climate change is already or will soon affect every sector of the economy, every community in the nation, and every nation in the world. Reducing the greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change and helping communities adapt to the unavoidable impacts already baked into the system requires domestic investment, rulemakings, and policy changes, as well as robust international diplomacy to incentivize other countries to also raise their ambitions. That means that every agency in the federal government has some degree of responsibility in addressing climate change—and so does every policy council in the White House.

This diffusion of responsibility can all too easily lead to confusion, turf battles, and inaction. When everyone is partially responsible, no one is ultimately in charge. And despite the increasing political salience of climate change to voters—particularly young people—the long time horizon for seeing results from many climate policies, not to mention the political and technical complexity of many climate solutions, means that the issue can all too easily be put on the back burner when a White House is faced with multiple urgent crises, like a global pandemic and a historic recession.

That is why the single most important thing a new White House must do is commission as Assistant to the President (AP) an experienced, respected Counselor or Senior Advisor who is 1) a credible leader on climate policy, 2) who sits in the West Wing and 3) who has direct access to and is trusted by the President of the United States, to lead the Administration’s domestic and international efforts on climate change. When there has been a single, forceful actor with the mandate to lead the President’s climate agenda, the White House has historically been able to organize the federal government to effectively address climate change. When that position has not been filled or has not been appropriately empowered, it has been appreciably harder to make progress.

While it is necessary to appoint and empower an AP to lead on the climate agenda, it is not sufficient. There are other important White House organizational changes needed to create an integrated domestic and international vision and provide sufficient staff resources. In addition to being led by an AP for Climate, as described above, a new administration must ensure that the White House structure meets the following criteria:

Staff resourcing. The White House must have the staff capacity and credibility to manage a whole-of-government climate effort. In addition to the AP position, the White House should have at least one Deputy Assistant to the President for Climate and Energy (DAP); three Special Assistants to the President for various climate functions, including one SAP dual-hatted to the National Economic Council, one dual-hatted to the National Security Council, and one dual-hatted to the Council on Environmental Quality; and further non-commissioned FTE climate staff to support the President’s climate agenda.

Policy council buy-in. The White House climate structure must create buy-in and serious engagement on climate across all White House policy councils, and facilitate effective collaboration, including through the dual-hatted SAPs.

Robust non-policy support. The White House must integrate the ongoing work of the climate team across non-policy offices, including Legislative Affairs, the White House Counsel’s Office, Communications and Digital, Cabinet Affairs, and the Presidential Personnel Office.

Regular interagency engagement. The White House climate structure must formalize an all-of-government approach to climate change, with senior White House staff engaging regularly with senior agency leadership to develop an ambitious climate agenda, monitor implementation, and continually identify opportunities to increase ambition.

To meet these essential criteria, the President should:

Issue an Executive Order to create a National Climate Council that is co-equal to the Domestic Policy Council and the National Economic Council to organize and drive White House and Administration actions. (Day 1)

For too long, climate policy has been sidelined as solely an environmental issue in the minds of many political operatives and elected officials. In the past, the core White House staff dedicated to domestic emissions reduction and energy transition policies have been grouped in the Domestic Policy Council, with additional support from CEQ and small numbers of domestic climate and energy staff at NEC and OSTP. In the absence of strong AP level leadership outside the DPC, it can be challenging for the DPC staff to coordinate activities with other policy councils or to get the leadership-level attention necessary for Presidential approval of policy initiatives or decisions. A DPC-led climate team can also struggle to plug in effectively to international climate policy led by the NSC, hamstringing both domestic and international progress.

Given the urgency of climate change, a new administration cannot allow these structural challenges to continue inside the White House. Creating a National Climate Council by Executive Order, just as the NEC and DPC were created by Presidents Clinton and Carter, respectively, would elevate climate change as an issue worthy of sustained, national policymaking and communications. It would also create a consistent organizational mechanism for climate change policy in the White House from year to year. In line with the above criteria, the NCC should be led by the Assistant to the President for Climate and staffed by the DAP for Climate Change and Energy, with at least three SAPs, dual-hatted to the NEC, NSC, and CEQ, and at least eight to ten further FTE staff as a starting point. Additional FTE positions on the NCC can be filled using flexible hiring authorities available to the Council on Environmental Quality and the Office of Science and Technology Policy.

It is important to emphasize that creating an NCC is not sufficient to deliver an effective, empowered White House climate team. In particular, an NCC that did not meet the four criteria above—for example, an NCC whose Director sits in the EEOB rather than the West Wing, an NCC without clear authority to drive both domestic and international climate policy, or an NCC that is not directly integrated into the other policy councils via double-hatted senior staff—would be less effective than a more informal structure that meets those criteria. If the President declines to create an NCC, these minimal staffing requirements—including the AP, DAP, and dual-hatted SAPs—are still essential to building a robust climate policy apparatus in the White House. The AP must be empowered to lead the integrated domestic and international climate agenda, and to draw on staff capacity from all the policy councils, along with functional offices like Communications and WHCO.

Launch a 90-day, Cabinet-level effort to craft a Climate Ambition Plan designed to hold the Administration accountable in meeting the President’s stated goals—and go further. (Day 1)

The next administration will need to set ambitious goals; design and implement policies that will put the United States on a path to achieving net-zero emissions no later than mid-century; and restore the U.S. to a position of global climate leadership that incentivizes increasingly strong climate commitments from other major emitters.

In order to translate those goals and other important policy priorities into a governing plan that will hold the Cabinet accountable for achieving results in a timely manner, the next administration should revive the successful Climate Action Plan approach from the second term of the Obama-Biden Administration. Specifically, at the same time the NCC is created, the President should launch a 90-day Cabinet-level task force to write and publish a new, four-year Climate Ambition Plan, containing within it specific, agency-by-agency actions on greenhouse gas mitigation and the clean energy transition, climate change adaptation and resilience, and international climate diplomacy and development. The AP for Climate should be tasked with driving the 90-day process and, after its completion, with ensuring every responsible Cabinet agency delivers against the policies included in the Climate Ambition Plan. The 90-day process to develop a Climate Ambition Plan should be launched whether or not an NCC is created.

Embed key aspects of the climate change agenda in other White House policy councils and functions, including CEQ, NSC, OSTP, OMB, CEA, and cross-functional offices like Communications, Cabinet Affairs, Legislative Affairs, OPE, WHCO, and PPO. (Day 1 and ongoing)

Even if a National Climate Council is created, other policymaking councils and cross-functional offices still will play critical roles in furthering an ambitious climate agenda. Appropriate staff from those councils and offices should be consistently included in NCC meetings and policy planning. As detailed later in this memo:

• The Council on Environmental Quality is best suited to elevate environmental justice to the White House and to lead the agenda on climate change resilience, in addition to its statutory responsibilities for NEPA and historic responsibilities for managing conservation and species issues.

• The International Economics deputate should be re-established within the NSC, with a climate-focused directorate led by a senior director (a SAP dual-hatted to the NCC) and team of two to three director-level positions, to work with the State Department and other key agencies on international negotiations and coordinate climate inputs into the President’s bilateral and multilateral engagements.

• The Office of Science and Technology Policy urgently needs to be re-empowered to support federal climate science and clean energy innovation in the U.S. and internationally.

• The Office of Management and Budget can and should be a stronger partner to federal agencies on climate policy. Senior political staff at OMB and its sub-agencies and offices, notably OIRA, should clearly understand that supporting the President’s climate agenda is a central part of their mandate. In terms of budget, OMB must prioritize securing the increased funding for climate and clean energy investments that should be integral to any COVID-19 economic stimulus package, and for implementing the Climate Ambition Plan. The OMB budget process is addressed in more detail in a separate memo.

• Cross-functional offices, including the White House Counsel’s Office, the communications shop, and the Presidential Personnel Office, should have staff who are dedicated to working on the climate portfolio and empowered to support ambitious activities.

Office of the U.S. Trade Representative

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) is unusual among EOP offices, in that it has the strongly outward-facing role of overseeing trade negotiations directly with other countries and working with the World Trade Organization (WTO) system. U.S. leadership of the global trading system has long allowed it to shape the international trade agenda so that it advances U.S. commercial and economic interests. Given the substantial impacts of climate change on the economy, USTR should more fully integrate climate change considerations into its work and encourage other countries and the global trading system to do the same.

USTR has traditionally had a robust structure on trade and environment, with an Assistant USTR for Environment who oversees negotiations on environment chapters in free trade agreements, WTO agenda items and WTO plurilateral agreement negotiations, trade and environment discussions at the UNFCCC and in other forums, and evaluation of trade barriers that arise out of environmental and climate policies. While the office retains a senior professional team on environmental issues, the previous administration had a limited focus on environmental issues, particularly on climate issues. USTR should dedicate greater staff resources with climate and trade expertise, and the U.S. Trade Representative should recognize climate and environment as key aspects of a 21st century trade regime.

USTR regularly coordinates with agency counterparts at the staff level through its Trade Policy Staff Committee (TPSC) and at policy levels through the Trade Policy Review Group (TPRG), works closely with its oversight committees in Congress, and seeks input from stakeholders, affected industries, workers, and NGOs, particularly through its cleared advisors process. USTR can enhance these relationships by adding in climate-specific agendas to better understand opportunities and challenges on the intersection of trade and climate issues.

USTR has a number of programmatic opportunities to advance climate and environmental policy within the context of trade. USTR and U.S. trade agencies—including the Departments of Energy, State, Transportation, Commerce, Treasury, and the EPA—should consider incorporating trade negotiating objectives for emissions mitigation, climate resilience, or other climate objectives in the context of bilateral and regional FTAs under negotiation. Against the backdrop of broader U.S. trade policy, and similar to efforts by the previous administration to negotiate “digital trade” agreements, USTR could also seek to negotiate targeted climate-specific trade agreements or arrangements, rather than comprehensive FTAs, that focus on specific climate concerns, such as trade in climate-related goods, enforcement of relevant multilateral environmental agreement provisions, and border adjustments to level the playing field.

Within the context of the WTO, the new administration could consider plurilateral agreements related to climate goals, e.g., with respect to fossil fuel subsidies, environmental goods, and other achievable trade-related climate objectives, as well as including climate-related consultation provisions in ongoing negotiations on e-commerce or fisheries subsidies. USTR can also work with Congress and within the administration on domestic WTO-consistent measures to ensure a level playing field and prevent cross-border carbon leakage such as border tax adjustments.

USTR can also work internationally with like-minded countries, to develop a consistent and plurilateral approach to prevent carbon leakage.

To view all the recommendations of the Climate 21 Project, please click here.

C21_EOP

Christy Goldfuss is the former Managing Director at CEQ, and former Deputy Director of the National Park Service.

Tim Profeta is a researcher at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions.

Kristina Costa is the former Advisor to the Counselor to the President Jeremy Symons and former Climate Policy Advisor at EPA.

Jeremy Symons is the former Climate Policy Advisor at EPA.

To download the full report, please click here.

Executive Office of the President: Transition Memo

Climate change is unique among the issues facing the President, because both the effects and the policy solutions to the challenge defy neat categorization. Climate change is already or will soon affect every sector of the economy, every community in the nation, and every nation in the world. Reducing the greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change and helping communities adapt to the unavoidable impacts already baked into the system requires domestic investment, rulemakings, and policy changes, as well as robust international diplomacy to incentivize other countries to also raise their ambitions. That means that every agency in the federal government has some degree of responsibility in addressing climate change—and so does every policy council in the White House.

This diffusion of responsibility can all too easily lead to confusion, turf battles, and inaction. When everyone is partially responsible, no one is ultimately in charge. And despite the increasing political salience of climate change to voters—particularly young people—the long time horizon for seeing results from many climate policies, not to mention the political and technical complexity of many climate solutions, means that the issue can all too easily be put on the back burner when a White House is faced with multiple urgent crises, like a global pandemic and a historic recession.

That is why the single most important thing a new White House must do is commission as Assistant to the President (AP) an experienced, respected Counselor or Senior Advisor who is 1) a credible leader on climate policy, 2) who sits in the West Wing and 3) who has direct access to and is trusted by the President of the United States, to lead the Administration’s domestic and international efforts on climate change. When there has been a single, forceful actor with the mandate to lead the President’s climate agenda, the White House has historically been able to organize the federal government to effectively address climate change. When that position has not been filled or has not been appropriately empowered, it has been appreciably harder to make progress.

While it is necessary to appoint and empower an AP to lead on the climate agenda, it is not sufficient. There are other important White House organizational changes needed to create an integrated domestic and international vision and provide sufficient staff resources. In addition to being led by an AP for Climate, as described above, a new administration must ensure that the White House structure meets the following criteria:

Staff resourcing. The White House must have the staff capacity and credibility to manage a whole-of-government climate effort. In addition to the AP position, the White House should have at least one Deputy Assistant to the President for Climate and Energy (DAP); three Special Assistants to the President for various climate functions, including one SAP dual-hatted to the National Economic Council, one dual-hatted to the National Security Council, and one dual-hatted to the Council on Environmental Quality; and further non-commissioned FTE climate staff to support the President’s climate agenda.

Policy council buy-in. The White House climate structure must create buy-in and serious engagement on climate across all White House policy councils, and facilitate effective collaboration, including through the dual-hatted SAPs.

Robust non-policy support. The White House must integrate the ongoing work of the climate team across non-policy offices, including Legislative Affairs, the White House Counsel’s Office, Communications and Digital, Cabinet Affairs, and the Presidential Personnel Office.

Regular interagency engagement. The White House climate structure must formalize an all-of-government approach to climate change, with senior White House staff engaging regularly with senior agency leadership to develop an ambitious climate agenda, monitor implementation, and continually identify opportunities to increase ambition.

To meet these essential criteria, the President should:

Issue an Executive Order to create a National Climate Council that is co-equal to the Domestic Policy Council and the National Economic Council to organize and drive White House and Administration actions. (Day 1)

For too long, climate policy has been sidelined as solely an environmental issue in the minds of many political operatives and elected officials. In the past, the core White House staff dedicated to domestic emissions reduction and energy transition policies have been grouped in the Domestic Policy Council, with additional support from CEQ and small numbers of domestic climate and energy staff at NEC and OSTP. In the absence of strong AP level leadership outside the DPC, it can be challenging for the DPC staff to coordinate activities with other policy councils or to get the leadership-level attention necessary for Presidential approval of policy initiatives or decisions. A DPC-led climate team can also struggle to plug in effectively to international climate policy led by the NSC, hamstringing both domestic and international progress.

Given the urgency of climate change, a new administration cannot allow these structural challenges to continue inside the White House. Creating a National Climate Council by Executive Order, just as the NEC and DPC were created by Presidents Clinton and Carter, respectively, would elevate climate change as an issue worthy of sustained, national policymaking and communications. It would also create a consistent organizational mechanism for climate change policy in the White House from year to year. In line with the above criteria, the NCC should be led by the Assistant to the President for Climate and staffed by the DAP for Climate Change and Energy, with at least three SAPs, dual-hatted to the NEC, NSC, and CEQ, and at least eight to ten further FTE staff as a starting point. Additional FTE positions on the NCC can be filled using flexible hiring authorities available to the Council on Environmental Quality and the Office of Science and Technology Policy.

It is important to emphasize that creating an NCC is not sufficient to deliver an effective, empowered White House climate team. In particular, an NCC that did not meet the four criteria above—for example, an NCC whose Director sits in the EEOB rather than the West Wing, an NCC without clear authority to drive both domestic and international climate policy, or an NCC that is not directly integrated into the other policy councils via double-hatted senior staff—would be less effective than a more informal structure that meets those criteria. If the President declines to create an NCC, these minimal staffing requirements—including the AP, DAP, and dual-hatted SAPs—are still essential to building a robust climate policy apparatus in the White House. The AP must be empowered to lead the integrated domestic and international climate agenda, and to draw on staff capacity from all the policy councils, along with functional offices like Communications and WHCO.

Launch a 90-day, Cabinet-level effort to craft a Climate Ambition Plan designed to hold the Administration accountable in meeting the President’s stated goals—and go further. (Day 1)

The next administration will need to set ambitious goals; design and implement policies that will put the United States on a path to achieving net-zero emissions no later than mid-century; and restore the U.S. to a position of global climate leadership that incentivizes increasingly strong climate commitments from other major emitters.

In order to translate those goals and other important policy priorities into a governing plan that will hold the Cabinet accountable for achieving results in a timely manner, the next administration should revive the successful Climate Action Plan approach from the second term of the Obama-Biden Administration. Specifically, at the same time the NCC is created, the President should launch a 90-day Cabinet-level task force to write and publish a new, four-year Climate Ambition Plan, containing within it specific, agency-by-agency actions on greenhouse gas mitigation and the clean energy transition, climate change adaptation and resilience, and international climate diplomacy and development. The AP for Climate should be tasked with driving the 90-day process and, after its completion, with ensuring every responsible Cabinet agency delivers against the policies included in the Climate Ambition Plan. The 90-day process to develop a Climate Ambition Plan should be launched whether or not an NCC is created.

Embed key aspects of the climate change agenda in other White House policy councils and functions, including CEQ, NSC, OSTP, OMB, CEA, and cross-functional offices like Communications, Cabinet Affairs, Legislative Affairs, OPE, WHCO, and PPO. (Day 1 and ongoing)

Even if a National Climate Council is created, other policymaking councils and cross-functional offices still will play critical roles in furthering an ambitious climate agenda. Appropriate staff from those councils and offices should be consistently included in NCC meetings and policy planning. As detailed later in this memo:

• The Council on Environmental Quality is best suited to elevate environmental justice to the White House and to lead the agenda on climate change resilience, in addition to its statutory responsibilities for NEPA and historic responsibilities for managing conservation and species issues.

• The International Economics deputate should be re-established within the NSC, with a climate-focused directorate led by a senior director (a SAP dual-hatted to the NCC) and team of two to three director-level positions, to work with the State Department and other key agencies on international negotiations and coordinate climate inputs into the President’s bilateral and multilateral engagements.

• The Office of Science and Technology Policy urgently needs to be re-empowered to support federal climate science and clean energy innovation in the U.S. and internationally.

• The Office of Management and Budget can and should be a stronger partner to federal agencies on climate policy. Senior political staff at OMB and its sub-agencies and offices, notably OIRA, should clearly understand that supporting the President’s climate agenda is a central part of their mandate. In terms of budget, OMB must prioritize securing the increased funding for climate and clean energy investments that should be integral to any COVID-19 economic stimulus package, and for implementing the Climate Ambition Plan. The OMB budget process is addressed in more detail in a separate memo.

• Cross-functional offices, including the White House Counsel’s Office, the communications shop, and the Presidential Personnel Office, should have staff who are dedicated to working on the climate portfolio and empowered to support ambitious activities.

Office of the U.S. Trade Representative

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) is unusual among EOP offices, in that it has the strongly outward-facing role of overseeing trade negotiations directly with other countries and working with the World Trade Organization (WTO) system. U.S. leadership of the global trading system has long allowed it to shape the international trade agenda so that it advances U.S. commercial and economic interests. Given the substantial impacts of climate change on the economy, USTR should more fully integrate climate change considerations into its work and encourage other countries and the global trading system to do the same.

USTR has traditionally had a robust structure on trade and environment, with an Assistant USTR for Environment who oversees negotiations on environment chapters in free trade agreements, WTO agenda items and WTO plurilateral agreement negotiations, trade and environment discussions at the UNFCCC and in other forums, and evaluation of trade barriers that arise out of environmental and climate policies. While the office retains a senior professional team on environmental issues, the previous administration had a limited focus on environmental issues, particularly on climate issues. USTR should dedicate greater staff resources with climate and trade expertise, and the U.S. Trade Representative should recognize climate and environment as key aspects of a 21st century trade regime.

USTR regularly coordinates with agency counterparts at the staff level through its Trade Policy Staff Committee (TPSC) and at policy levels through the Trade Policy Review Group (TPRG), works closely with its oversight committees in Congress, and seeks input from stakeholders, affected industries, workers, and NGOs, particularly through its cleared advisors process. USTR can enhance these relationships by adding in climate-specific agendas to better understand opportunities and challenges on the intersection of trade and climate issues.

USTR has a number of programmatic opportunities to advance climate and environmental policy within the context of trade. USTR and U.S. trade agencies—including the Departments of Energy, State, Transportation, Commerce, Treasury, and the EPA—should consider incorporating trade negotiating objectives for emissions mitigation, climate resilience, or other climate objectives in the context of bilateral and regional FTAs under negotiation. Against the backdrop of broader U.S. trade policy, and similar to efforts by the previous administration to negotiate “digital trade” agreements, USTR could also seek to negotiate targeted climate-specific trade agreements or arrangements, rather than comprehensive FTAs, that focus on specific climate concerns, such as trade in climate-related goods, enforcement of relevant multilateral environmental agreement provisions, and border adjustments to level the playing field.

Within the context of the WTO, the new administration could consider plurilateral agreements related to climate goals, e.g., with respect to fossil fuel subsidies, environmental goods, and other achievable trade-related climate objectives, as well as including climate-related consultation provisions in ongoing negotiations on e-commerce or fisheries subsidies. USTR can also work with Congress and within the administration on domestic WTO-consistent measures to ensure a level playing field and prevent cross-border carbon leakage such as border tax adjustments.

USTR can also work internationally with like-minded countries, to develop a consistent and plurilateral approach to prevent carbon leakage.

To download the full report, please click here.

C21_EOP

Christy Goldfuss is the former Managing Director at CEQ, and former Deputy Director of the National Park Service.

Tim Profeta is a researcher at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions.

Kristina Costa is the former Advisor to the Counselor to the President Jeremy Symons and former Climate Policy Advisor at EPA.

Jeremy Symons as the former Climate Policy Advisor at EPA.

William Krist's Blog