William Krist's Blog, page 44

March 31, 2021

2021 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers

SCOPE AND COVERAGE

FOREWORD

The 2021 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers (NTE) is the 36th in an annual series that highlights significant foreign barriers to U.S. exports, U.S. foreign direct investment, and U.S. electronic commerce. This document is a companion piece to the President’s 2021 Trade Policy Agenda and 2020 Annual Report, published by the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) in March.

In accordance with section 181 of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended by section 303 of the Trade and Tariff Act of 1984 and amended by section 1304 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, section 311 of the Uruguay Round Trade Agreements Act, and section 1202 of the Internet Tax Freedom Act, USTR is required to submit to the President, the Senate Finance Committee, and appropriate committees in the House of Representatives, an annual report on significant foreign trade barriers. The statute requires an inventory of the most important foreign barriers affecting U.S. exports of goods and services, including agricultural commodities and U.S. intellectual property; foreign direct investment by U.S. persons, especially if such investment has implications for trade in goods or services; and U.S. electronic commerce. Such an inventory enhances awareness of these trade restrictions, facilitates U.S. negotiations aimed at reducing or eliminating these barriers, and is a valuable tool in enforcing U.S. trade laws and strengthening the rules-based system.

The NTE Report is based upon information compiled within USTR, the Departments of Commerce and Agriculture, other U.S. Government agencies, and U.S. Embassies, as well as information provided by the public in response to a notice published in the Federal Register.

This report discusses the largest export markets for the United States, covering 61 countries, the European Union, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the Arab League. The discussion of Chinese trade barriers is structured and focused to align more closely with other Congressional reports prepared by USTR on U.S.-China trade issues. The China section includes cross-references to other USTR reports where appropriate. As always, omission of particular countries and barriers does not imply that they are not of concern to the United States.

Trade barriers elude fixed definitions, but may be broadly defined as government laws, regulations, policies, or practices that protect domestic goods and services from foreign competition, artificially stimulate exports of particular domestic goods and services, or fail to provide adequate and effective protection of intellectual property rights.

The NTE covers significant barriers, whether they are consistent or inconsistent with international trading rules. Tariffs, for example, are an accepted method of protection under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994 (GATT 1994). Even a very high tariff does not violate international rules unless a country has made a commitment not to exceed a specified rate, i.e., a tariff binding. Nonetheless, it would be a significant barrier to U.S. exports, and therefore covered in the NTE Report. Measures not consistent with international trade agreements, in addition to serving as barriers to trade and causes of concern for policy, are actionable under U.S. trade law as well as through the World Trade Organization (WTO). Since early 2020, there were significant trade disruptions as a result of temporary trade measures taken unique to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This report classifies foreign trade barriers in eleven categories. These categories cover government-imposed measures and policies that restrict, prevent, or impede the international exchange of goods and services, unduly hamper U.S. foreign direct investment or U.S. electronic commerce. The categories covered include:

Import policies (e.g., tariffs and other import charges, quantitative restrictions, import licensing, preshipment inspection, customs barriers and shortcomings in trade facilitation or in valuation practices, and other market access barriers);

Technical barriers to trade (e.g., unnecessarily trade restrictive standards, conformity assessment procedures, labeling, or technical regulations, including unnecessary or discriminatory technical regulations or standards for telecommunications products);

Sanitary and phytosanitary measures (e.g., trade restrictions implemented through unwarranted measures not based on scientific evidence);

Subsidies, especially export subsidies (e.g., subsidies contingent upon export performance and agricultural export subsidies that displace U.S. exports in third country markets) and local content subsidies (e.g., subsidies contingent on the purchase or use of domestic rather than imported goods);

Government procurement (e.g., closed bidding and bidding processes that lack transparency);

Intellectual property protection (e.g., inadequate patent, copyright, and trademark regimes and inadequate enforcement of intellectual property rights);

Services barriers (e.g., prohibitions or restrictions on foreign participation in the market, discriminatory licensing requirements or regulatory standards, local-presence requirements, and unreasonable restrictions on what services may be offered);

Barriers to digital trade and electronic commerce (e.g., barriers to cross-border data flows, including data localization requirements, discriminatory practices affecting trade in digital products, restrictions on the provision of Internet-enabled services, and other restrictive technology requirements);

Investment barriers (e.g., limitations on foreign equity participation and on access to foreign government-funded research and development programs, local content requirements, technology transfer requirements and export performance requirements, and restrictions on repatriation of earnings, capital, fees and royalties);

Competition (e.g., government-tolerated anticompetitive conduct of state-owned or private firms that restricts the sale or purchase of U.S. goods or services in the foreign country’s markets or abuse of competition laws to inhibit trade); and

Other barriers (e.g., barriers that encompass more than one category, such as bribery and corruptioni).

Pursuant to Section 1377 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, USTR annually reviews the operation and effectiveness of U.S. telecommunications trade agreements to make a determination on whether any foreign government that is a party to one of those agreements is failing to comply with that government’s obligations or is otherwise denying, within the context of a relevant agreement, “mutually advantageous market opportunities” to U.S. telecommunication products or services suppliers. The NTE Report highlights both ongoing and emerging barriers to U.S. telecommunication services and goods exports used in the annual review called for in Section 1377.

USTR continues to vigorously scrutinize foreign labor practices and to address substandard practices that impinge on labor obligations in U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs) and deny foreign workers their internationally recognized labor rights. In addition, USTR has enhanced its monitoring and enforcement of U.S. FTA partners’ implementation and compliance efforts with respect to their obligations under the environment chapters of those agreements. To further these initiatives, USTR has implemented interagency processes for systematic information gathering and review of labor rights practices and environmental measures in FTA countries, and USTR staff regularly work with FTA countries to monitor practices, and directly engages governments and other stakeholders in its monitoring efforts. The Administration has reported on these activities in the 2021 Trade Policy Agenda and 2020 Annual Report of the President on the Trade Agreements Program.

NTE sections also report the most recent statistical data on U.S. bilateral trade in goods and services, and compare these data to those of the preceding year. This information is reported to provide context for the reader. The merchandise trade data contained in the NTE are based on total U.S. exports, free alongside ship (f.a.s.)ii value, and general U.S. imports, customs value, as reported by the Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce. The services data and direct investment are compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) in the Department of Commerce. (NOTE: These data are provided in Appendix II, ranked according to the size of the market).

2021NTE

To read the full report from the Office of the United States Trade Representative, please click here

March 25, 2021

Four Ways to Achieve a Worker- Centric Trade Policy

Biden administration officials have pledged to pursue a “worker-centric” or “worker-centered” trade policy.[1] The following four policies would allow President Biden to achieve that goal.

Eliminate taxes on imports used by U.S. workers

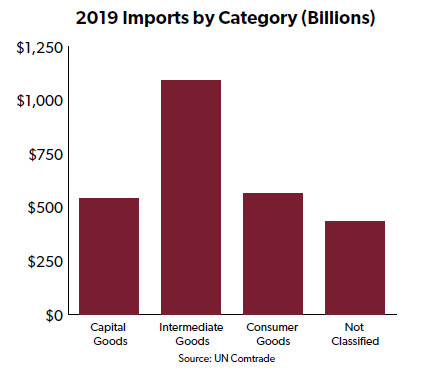

In 2019, 62.1 percent of imports were either intermediate goods like motor vehicle parts or capital goods like machinery that are used by U.S. workers to produce goods.[2] Eliminating taxes on these imports would support American manufacturing jobs, encourage companies to locate in the United States instead of abroad, and boost exports.

For example, in 2019 the United States collected more than $2.1 billion in taxes on imported motor vehicles parts.[3] Eliminating tariffs on motor vehicle parts would make the United States more attractive to car manufacturers looking for the best location to assemble vehicles.

Figure 1: 2019 Imports by Category

Eliminate taxes on imported shoes and clothing worn by U.S. workers

The Biden administration has pointed out that every consumer is also a worker: “The President knows that trade policy should respect the dignity of work and value Americans as workers and wage-earners, not only as consumers.”[4]

The inverse is also true: every worker is a consumer, and in 2019 American workers paid an average 14 percent tax on imported shoes and clothing.[5]

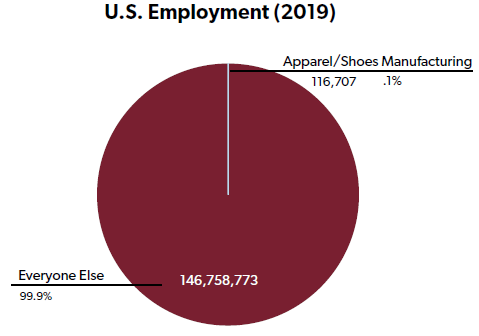

Shoe and clothing tariffs pit a small number of workers who benefit from tariffs against the vast majority of the American workforce. For every worker in the apparel and footwear manufacturing industry, 1,258 Americans working in other industries pay inflated prices for shoes and clothing as a result of double-digit import taxes.[6]

Figure 2: Number of U.S. Jobs

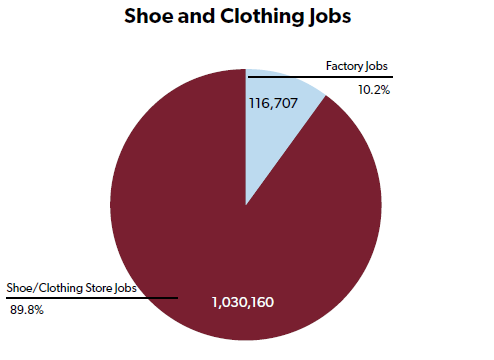

Tariffs pit workers against one another even within the shoe and clothing industry. Jobs in shoe and clothing stores outnumber jobs in shoe and clothing factories by nearly 9-to-1.[7] That doesn’t even count the millions of Americans who sell clothing and shoes at large department stores and sporting good stores.

Figure 3: U.S. Shoe and Clothing Jobs

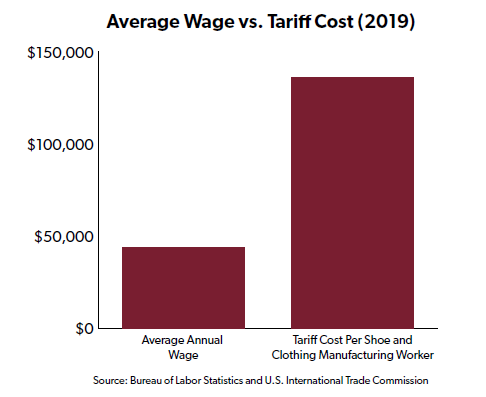

The federal government collected $15.8 billion from taxes on imported shoes and clothing in 2019, the equivalent of $135,776 for every production worker in the apparel and footwear industry. On average, apparel and footwear manufacturing workers earned less than $44,000.[8] Compared to the $15.8 billion cost of tariffs, it would cost taxpayers less to pay every person in the industry three times their current salary.

Figure 4: Average Annual Wage vs. Tariff Cost Per Shoe and Clothing Manufacturing Worker

The shoe and footwear industry includes more than just manufacturing and retail workers. More than 28,000 American fashion designers earned an average of $73,790 in 2019 creating new clothing and footwear. Millions more work in the transportation and logistics industries that help deliver such items to consumers.[9] Eliminating tariffs on shoes and clothing would directly boost employment in these sectors. Nationwide, additional jobs would be created indirectly as the dollars American workers save as a result of lower-cost shoes and clothing were spent on other goods and services or invested in the U.S. economy.

Negotiate job-creating trade agreements

The United States has been falling behind the rest of the world in negotiating trade agreements, and as a result U.S. exporters face higher tariffs than do most of their foreign competitors. As of 2016, U.S. exporters faced an average foreign tariff of 4.9 percent, ranking in the bottom ten of 136 countries ranked by the World Economic Forum.[10]

The United States has failed to implement a single new market-opening trade agreement since 2012. Since our last trade agreement took effect, other countries have signed 70 regional trade agreements, notably including the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).[11] The Trump administration’s U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is not included, since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) had already eliminated most tariffs between the three countries.

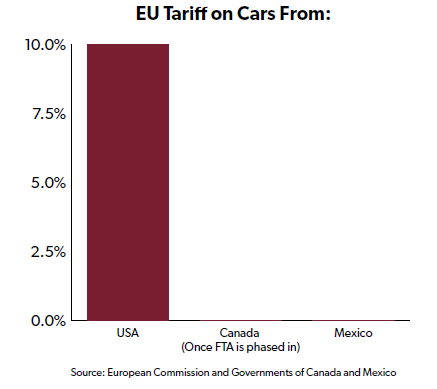

To illustrate why the failure to negotiate new trade agreements has been costly for American workers, consider the automobile industry. Cars exported from the United States to the European Union (EU) face a 10 percent tariff. But because Canada and Mexico have managed to negotiate trade agreements with the EU, cars exported from Canada and Mexico will enter tariff-free once those agreements are fully phased in.[12]

Figure 5: EU Automobile Tariffs

This gives Canada and Mexico a big advantage over the United States in attracting investment from carmakers that want to export to the EU. For example, when BMW announced a new factory in Mexico in 2014, the company said, “The large number of international free trade agreements – within the NAFTA area, with the European Union and the MERCOSUR member states, for example – was a decisive factor in the choice of location.” When Audi chose to locate a new factory in Mexico instead of Tennessee in 2012, the company’s chairman said, “Good infrastructure, competitive cost structures and existing free trade agreements played a significant role in the choice of Mexico.”[13]

If trade negotiators from Canada and Mexico have been able to negotiate tariff-free access to the EU (or close to it), what’s keeping U.S. negotiators from doing the same thing? Unfortunately, the Biden administration has suggested it will put trade negotiations on the back burner. According to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, “President Biden has been clear that he will not sign any new free trade agreements before the U.S. makes major investments in American workers and our infrastructure. Our economic recovery at home must be our top priority.”[14]

This is the wrong approach. Negotiating good trade agreements and making economic recovery the top priority is not an either-or proposition. Pursuit of good trade agreements would create good new jobs for American workers and boost the U.S. economy.

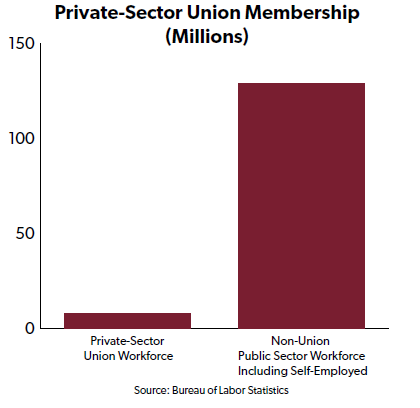

Follow a trade policy designed to benefit more than just unionized workers

According to the Biden administration, “President Biden’s trade agenda will support all workers.”[15]

That is much better than pursuing a trade agenda that focuses on the 5.5 percent of the private-sector workforce who belong to labor unions without regard to the other 94.5 percent.[16]

Figure 6: Union Membership (Millions)

The goal of trade agreements should be to benefit workers by reducing barriers to international trade and investment, as opposed to imposing new multinational labor regulations or minimum wage provisions.

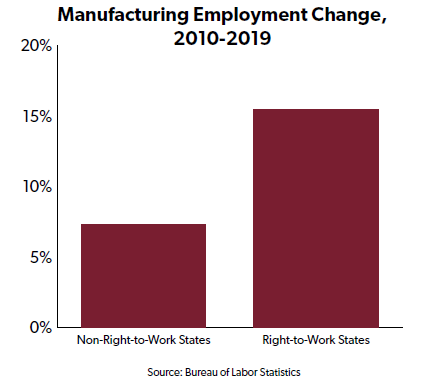

However, if labor provisions are to be included in future trade agreements, the Biden administration should consider guaranteeing every worker’s right to work without joining a labor union. Manufacturing workers in particular could benefit from this labor policy. In recent years, manufacturing employment in states with right-to-work laws has increased more than twice as much as in states that do not have such laws.[17]

Figure 7: Manufacturing Employment Change, 2010-2019

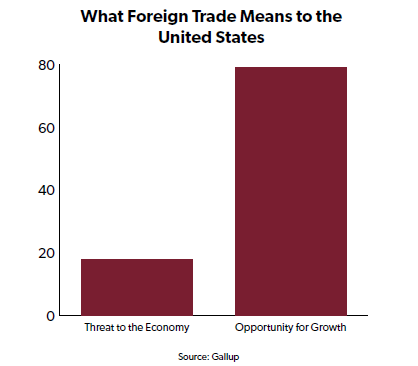

The White House has said that our trade and international economic policies must serve all Americans.[18] If the Biden administration is serious about that, a good start would be for it to listen to Americans, who believe trade is more of an opportunity than a threat by a 4.4-to-1 margin.[19]

Figure 8: What Foreign Trade Means to the United States

According to U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai, “i think that for a very long time our trade policies were based on an assumption that the more we traded with each other and the more liberalized our trade, the more peace and prosperity there would be.”[20] For the most part, that’s exactly what happened.

The problem facing American workers is too little trade liberalization, not too much. Workers continue to be harmed by U.S. taxes on imported inputs that they need to do their jobs, by import taxes that increase the cost of their shoes and clothing, and by the government’s failure to implement new market-opening trade agreements. A truly worker-centered trade policy should correct these shortcomings.

[1] Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. (2021). “Fact Sheet: 2021 Trade Agenda and 2020 Annual Report.”(Accessed March 21, 2021) https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/2021/march/fact-sheet-2021-trade-agenda-and-2020-annual-report.

[2] Author’s calculations from United Nations Comtrade database, accessed March 21, 2021, comtrade.un.org/data.

[3] Imports for Consumption, U.S. International Trade Commission, accessed March 21, 2021 dataweb.usitc.gov.

[4] Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. (March 2021.) “2021 Trade Policy Agenda and 2020 Annual Report,” (Accessed March 21, 2021.) https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/reports/2021/2021%20Trade%20Agenda/Online%20PDF%202021%20Trade%20Policy%20Agenda%20and%202020%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

[5] U.S. International Trade Commission. “Imports for Consumption.” Accessed March 21, 2021, dataweb.usitc.gov.

[6] Author’s calculation from “May 2019 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed March 21, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/data/#employment.

[7] Author’s calculation from “May 2019 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed March 21, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/data/#employment.

[8] Author’s calculation from “May 2019 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed March 21, 2012, https://www.bls.gov/data/#employment.

[9] Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019.) “May 2019 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates,” (Accessed March 21, 2021.) https://www.bls.gov/data/#employment.

[10] World Economic Forum. (2016.) “The Global Enabling Trade Report.” Retrieved from: https://reports.weforum.org/global-enabling-trade-report-2016/enabling-trade-rankings/#series=TARIFACED.

[11] World Trade Organization. “Regional Trade Agreements Database”. (Accessed March 21, 2021.) http://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicMaintainRTAHome.aspx. Note: Recent UK trade agreements are not included in this count.

[12] Government of Canada. (2021.) “Opportunities and Benefits of CETA for Canada’s Automotive Exporters,” (Accessed March 21, 2021.) https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/ceta-aecg/business-entreprise/sectors-secteurs/auto.aspx?lang=eng; and the Government of Mexico (2021). “The Automobile Sector in Mexico,” (Accessed March 21, 2021). http://www.economia-snci.gob.mx/sic_php/pages/bruselas/pdfs/FS02AUT.pdf.

[13] Thomson, Adam, and Reed, John. “Audi to open Mexico production plant.” Financial Times, April 8, 2012. https://www.ft.com/content/ab3abae8-8987-11e1-85b6-00144feab49a.

[14] Shalal, Andrea, and Lawder, David. “Domestic investment needed before new trade deals: U.S. Treasury pick Yellen.” Reuters, January 21, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-biden-yellen-trade/domestic-investment-needed-before-new-trade-deals-u-s-treasury-pick-yellen-idUSKBN29Q2RZ.

[15] Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. (2021.) “Fact Sheet: 2021 Trade Agenda and 2020 Annual Report,” Accessed March 21, 2021. https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/2021/march/fact-sheet-2021-trade-agenda-and-2020-annual-report.

[16] Author’s calculation based on “Union affiliation of employed wage and salary workers by occupation and industry,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed March 21, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.t03.htm, and “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed March 21, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/webapps/legacy/cpsatab9.htm. Private-sector workforce includes self-employed Americans.

[17] Author’s calculation from “Employment by State,” Bureau of Economic Analysis, accessed March 21, 2021, https://www.bea.gov/data/employment/employment-by-state.

[18] The White House. (2021). “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,” (Accessed March 21, 2021.) https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf

[19] Saad, Lydia. “Americans’ Vanishing Fear of Foreign Trade.” Gallup, February 26, 2020. https://news.gallup.com/poll/286730/americans-vanishing-fear-foreign-trade.aspx.

[20] “Senate Finance Committee Hearing on Nomination of Katherine Tai to be U.S. Trade Representative,” YouTube, February 25, 2021, accessed March 22, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rm3QlkYL9Es.

Four-Ways-to-Achieve-a-Worker-Centric-Trade-Policy-2-

To view the original research by the National Taxpayers Union Foundation, please click here.

March 16, 2021

Reauthorizing Trade Promotion Authority: The first trade test for the Biden administration

The expiration of Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) on July 1 provides an opportunity for the Biden administration to clarify whether pursuing new agreements, including joining the now renamed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), will be part of its approach to trade.

The Biden administration has so far been deliberately ambiguous about its trade policy, preferring broad statements (“a worker-centric” trade policy) to specific proposals. The expiration of Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) on July 1 provides an opportunity to clarify whether pursuing new agreements, including joining the now renamed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), will be part of the new administration’s approach to trade. If the administration does decide to take a more aggressive approach to trade, polling data suggest it will find a public that has grown much more supportive of trade over the past four years.

Reauthorizing Trade Promotion Authorityv2

To view the original research, please click here.

March 9, 2021

Economic Report of the President Provides Feeble Defense of Trump Trade Policy

Failure to accurately assess the impact of trade agreements

The report’s chapter on trade policy begins: “…the Trump Administration inherited a legacy of asymmetric trading arrangements that had imposed steep costs on U.S. manufacturing and segments of the labor market.”

In fact, U.S. trade agreements are generally symmetric and fair. They embody the very “free, fair, and reciprocal” goals the Trump administration claimed to be pursuing.

With a handful of exceptions on both sides, all U.S. trade agreements required each trading partner to treat foreign and imported goods equally. In addition to being free, fair, and reciprocal, most trade agreements negotiated prior to President Trump successfully reduced foreign tariffs by more than U.S. tariffs.That’s part of the reason that while U.S. tariffs have declined, foreign tariffs have declined by even more.

The Economic Report adds, “…unfair trading arrangements…have harmed, in particular, U.S. manufacturing and manufacturing employment.” In fact, real manufacturing output increased by more than 50 percent from 1997 to 2019 as U.S. and global trade barriers fell. Manufacturing employment fell because manufacturing workers became more productive, and manufacturing job losses were typically not due to layoffs but instead resulted from workers finding better jobs.

PA-912

To read the original issue brief from the National Taxpayers Union Foundation, please click here

Bryan Riley is Director of NTU’s Free Trade Initiative. Bryan’s background includes years of research on the impact trade has on people in the United States. He has led grassroots campaigns in support of initiatives like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and in opposition to special-interest efforts to get the government to pick winners and losers in the U.S. economy. Bryan has been quoted in publications including the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. He is also an in-demand speaker who travels the country explaining the benefits international trade and investment bring to Americans. Bryan Riley grew up in Manhattan, Kansas. He holds a bachelor’s degree in economics from Kansas State University and a master’s degree in economics from the University of Southern California. Bryan first came to Washington, DC as an NTU intern during the Reagan administration, and he continues to champion President Reagan’s pro-trade vision for America.

Protectionism or National Security? The Use and Abuse of Section 232

President Biden took office at the height of modern American protectionism. The trade policy legacy he inherited from the Trump administration puts the United States at a crossroads. Will Biden go down the problematic path of executive overreach like his predecessor, or will he forge a new path? We may not need to wait long to find out. In his first trade action, President Biden reinstated tariffs on aluminum from the United Arab Emirates under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which authorizes the president to impose tariffs when a certain product is “being imported into the United States in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair national security.” Though infrequently used in the past, Section 232 was a favored trade tool of the Trump administration, which was responsible for nearly a quarter of all Section 232 investigations initiated since 1962. While Congress has constitutional authority over trade policy, Section 232 gives the president broad discretion to enact protectionist measures in the name of national security.

Why is this law a problem? First, the statute’s lack of an objective definition of “national security” permits essentially anything to be considered a threat, regardless of the merits. Second, the law’s lack of detailed procedural requirements encouraged the Trump administration to cut corners in applying the law, thus breeding cronyism and confusion. Third, President Trump took advantage of the law’s ambiguity to shield key Section 232 findings from Congress and the public, undermining both transparency and accountability.

The Trump administration’s abuse of the rarely used Section 232 has allowed the statute to become an excuse for blatant commercial protectionism, harming American companies and consumers and our security interests. It’s unclear whether the Biden administration will continue this troubling trend or seek reform. The best course of action would be the latter: Biden should avoid using Section 232 and support congressional efforts to rein in presidential power, thus ensuring an end to the calamitous episodes that were common during the Trump era.

To read the original policy analysis from the CATO Institute, please click here

March 8, 2021

Outcompeting Beijing: A Roadmap for Meeting China’s Commercial Challenges

The relationship between the United States and China is one of the most important geopolitical relation- ships in the world—and will be for the foreseeable future. How Washington and Beijing manage their relationship will have far-ranging consequences for global peace, prosperity and stability for decades to come.

With a global pandemic ravaging the world on the heels of a temporary détente in a protracted and intense trade war, the relationship between Washington and Beijing is souring. The media, politicians and pundits now routinely refer to the deteriorating relationship between the United States and China as a new “cold war.” However, the analogy is flawed. The United States and the Soviet Union were never economically integrated the way the United States and China are today, which makes the Washington-Beijing relationship much more complicated and challenging to manage. Though the United States’ and China’s economic integration began in the 1970s, Beijing’s place in the rules-based economic system was guaranteed by its admission into the World Trade Organization (WTO). Much of the current dis- course today revolves around Beijing’s membership in the WTO, which ostensibly prevents the United States from discriminating against Chinese trade and investment.

One of the bedrock principles that governs international trade is the most-favored-nation (MFN) status. With some exceptions, such as bilateral or regional free trade agreements, MFN status requires WTO members to treat other WTO members equally when applying tariffs or other trade barriers to their goods. When Beijing began negotiations to join the WTO, U.S. law prohibited permanently grant- ing communist countries like China MFN. However, after a lengthy negotiation between Washington and Beijing, and a vigorous debate in Congress, President Clinton signed legislation granting China permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) in October 2000. A year later, China formally joined the WTO. Though increasingly controversial today, the decision to grant China PNTR and welcome Beijing into the WTO enjoyed wide bipartisan support in Congress at the time—and was broadly supported by foreign policy analysts and the U.S. business and agricultural communities.

Today, critics contend that rather than moving China in a democratic, capitalist direction, admitting Beijing into the WTO simply empowered a brutal regime and decimated U.S. manufacturing through a surge of imports. Yet policies must be judged by the calculus facing lawmakers at the time the decision was made, not based on information avail- able to policymakers nearly two decades ex post. Under that framework, the decision to admit China into the WTO was the right one at the time. Likewise, even with the benefit of hindsight, the decision still makes sense today even if some of the more Panglossian predictions about the nature of the government in Beijing did not come to fruition.

To be sure, all is not well with the U.S.-China relationship. From the trade war and investment restrictions to tensions over Hong Kong, Taiwan and the treatment of Uighur Muslims, the Biden administration inherited an increasingly toxic relationship with Beijing. Opportunities to de-escalate the tensions exist, but it will be a fraught task. This paper will briefly detail the recent history of the U.S.-China commercial relationship, diagnose the current problems, explain the failures of the current approach and provide policymakers with concrete policy ideas to outcompete China in the 21st century.

To understand the current economic clash between Wash- ington and Beijing, it is imperative to understand a brief post- World War II history of Sino-American relations, though a full accounting is beyond the scope of this paper.

Between the establishment of the Republic of China in 1949 and the early 1970s, the United States and China had little interaction, including virtually no international trade or investment. After Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s secret visit to Beijing in 1971 and President Richard Nixon’s subsequent trip in 1972, relations between the United States and China began to thaw.11 These meetings would eventually lead to the normalization of diplomatic and economic relations between the two countries as the United States sought a new ally in its Cold War with the Soviet Union.

In the late 1970s, China made internal reforms to its eco- nomic model that continue to have a profound impact on the global economy. As one economist notes in his comprehen- sive history of U.S. trade policy:

In the 1970s, China was one of the poorest coun- tries in the world…and it had virtually no presence in world markets. In 1978, China’s premier, Deng Xiop- ing, began to open what had been a closed economy, moving it away from rigid state control and central planning toward a market-oriented system with lim- ited private enterprise. Agricultural collectives were phased out, and private farming was introduced; the state monopoly on foreign trade was abolished; foreign investment was gradually permitted; and trade barriers were reduced in stages.

These policy reforms led to a dramatic acceleration in China’s economic growth and sparked a rapid expan- sion in its foreign trade…Within two decades, China made an enormous impact on world markets and trade flows. China’s share of world exports rose from miniscule proportions in 1980 to 5 percent in 2000, reaching 12 percent in 2014.

Indeed, Beijing’s own internal reforms are much more important to its status today as an economic superpower than Washington’s decision to grant China PNTR—or the rest of the world’s decision to admit the country into the WTO. In many ways, the “main explanation for the rapid growth in imports from China in the 1990s and 2000s was the large size and rapid growth of the Chinese economy.”

Final-No.-223-China-trade

To read the original policy study from the R Street Institute, please click here

About the Author: Clark Packard is a resident fellow and trade policy counsel in the Finance, Insurance and Trade policy department at the R Street Institute. Clark joined R Street from the National Taxpayers Union, where he spearheaded the organization’s work on trade and financial services policy and provided legal counsel to the organization’s senior officers. Previously, he was an attorney and policy adviser for two former South Carolina governors. Earlier in his career, Clark worked in private legal practice, where he advised financial services companies on federal and state financial regulation. Clark is a graduate of the University of South Carolina School of Law. He is a member of the South Carolina Bar.

March 1, 2021

Global Trends 2040 – A More Contested World

Welcome to the 7th edition of the National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends report. Published every four years since 1997, Global Trends assesses the key trends and uncertainties that will shape the strategic environment for the United States during the next two decades.

Global Trends is designed to provide an analytic framework for policymakers early in each administration as they craft national security strategy and navigate an uncertain future. The goal is not to offer a specific prediction of the world in 2040; instead, our intent is to help policymakers and citizens see what may lie beyond the horizon and prepare for an array of possible futures.

Each edition of Global Trends is a unique undertaking, as its authors on the National Intel- ligence Council develop a methodology and formulate the analysis. This process involved numerous steps: examining and evaluating previous editions of Global Trends for lessons learned; research and discovery involving widespread consultations, data collection, and commissioned research; synthesizing, outlining, and drafting; and soliciting internal and ex- ternal feedback to revise and sharpen the analysis.

A central component of the project has been our conversations with the world outside our security gates. We benefited greatly from ongoing conversations with esteemed academ- ics and researchers across a range of disciplines, anchoring our study in the latest theories and data. We also broadened our contacts to hear diverse perspectives, ranging from high school students in Washington DC, to civil society organizations in Africa, to business lead- ers in Asia, to foresight practitioners in Europe and Asia, to environmental groups in South America. These discussions offered us new ideas and expertise, challenged our assump- tions, and helped us to identify and understand our biases and blind spots.

One of the key challenges with a project of this breadth and magnitude is how to organize all the analysis into a story that is coherent, integrated, and forward looking. We constructed this report around two central organizing principles: identifying and assessing broad forces that are shaping the future strategic environment, and then exploring how populations and leaders will act on and respond to the forces.

Based on those organizing principles, we built the analysis in three general sections. First, we explore structural forces in four core areas: demographics, environment, economics, and technology. We selected these areas because they are foundational in shaping future dynamics and relatively universal in scope, and because we can offer projections with a reasonable degree of confidence based on available data and evidence. The second section examines how these structural forces interact and intersect with other factors to affect emerging dynamics at three levels of analysis: individuals and society, states, and the inter- national system. The analysis in this section involves a higher degree of uncertainty because of the variability of human choices that will be made in the future. We focus on identifying and describing the key emerging dynamics at each level, including what is driving them and how they might evolve over time. Finally, the third section identifies several key uncertainties and uses these to create five future scenarios for the world in 2040. These scenarios are not intended to be predictions but to widen the aperture as to the possibilities, exploring various combinations of how the structural forces, emerging dynamics, and key uncertain- ties could play out.

When exploring the long-term future, another challenge is choosing which issues to cov- er and emphasize, and which ones to leave out. We focused on global, long-term trends and dynamics that are likely to shape communities, states, and the international system for decades and to present them in a broader context. Accordingly, there is less on other near- term issues and crises.

We offer this analysis with humility, knowing that invariably the future will unfold in ways that we have not foreseen. Although Global Trends is necessarily more speculative than most intelligence assessments, we rely on the fundamentals of our analytic tradecraft: we construct arguments that are grounded in data and appropriately caveated; we show our work and explain what we know and do not know; we consider alternative hypotheses and how we could be wrong; and we do not advocate policy positions or preferences. Global Trends reflects the National Intelligence Council’s perspective on these future trends; it does not represent the official, coordinated view of the US Intelligence Community nor US policy.

We are proud to publish this report publicly for audiences around the world to read and consider. We hope that it serves as a useful resource and provokes a conversation about our collective future.

Finally, a note of gratitude to colleagues on the National Intelligence Council and the wider Intelligence Community who joined in this journey to understand our world, explore the future, and draft this report.

GlobalTrends_2040

To read the original report from the Strategic Futures Group National Intelligence Council, please click here

Covid-19 and the Danger of Self-sufficiency: How Europe’s Pandemic Resilience was Helped by an Open Economy

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Europe has benefitted strongly from being an open economy that can access goods and services from other parts of the world. Paradoxically, some politicians in Europe think that dependence on foreign supplies reduced the resilience of our economy – and argue that Europe now should wean itself off its dependence on other economies. In this Policy Brief, it is argued that self-sufficiency or less economic openness is a dangerous direction of policy. It would make Europe less resilient and less capable of responding to the next emergency.

It is key that people, firms and governments can get supplies from other parts of the world. It is diversification, not concentration of production, that will make Europe more resilient when the next emergency hit. We don’t know where the next crisis will come from. Nature will throw nasty surprises at us, and we will make stupid mistakes, some of which will have devastating consequences. What we do know, though, is that we stand a better chance to fight the next emergency if we get richer and improve our technology. The best policy for resilience is one that encourages specialisation and innovation – and, when the emergency hit, allow for people to improvise in search for solutions. For that to happen, we need openness to goods, services and technology from abroad.

ECI_21_PolicyBrief_02_2021_LY02

To read the original policy brief from the European Centre for International Political Economy, please click here

The Covid-19 Vaccine Production Club: Will Value Chains Temper Nationalism?

1. Introduction*

That vaccines for COVID-19 were developed so quickly during 2020 was a welcome source of hope in an otherwise bleak year. The approval of several vaccines at the end of last year was seen by many as a turning point in the global response to the pandemic, raising expectations that the threats to public health would soon be tackled through national inoculation strategies and that, ultimately, restrictions on everyday life could be lifted (IMF 2020).

The optimism witnessed in the New Year dissipated in the face of delays to the production of COVID-19 vaccines (Harford 2021)6 and reports that mutations of the coronavirus have resulted in new “variants,” some of which pose a greater public health threat than the original strain. The former has resulted in some governments losing trust in certain vaccine manufacturers, which in turn has triggered a controversial trade policy response (Evenett 2021a). The latter has led to the realization that COVID- 19 may become a permanent threat to global public health, potentially requiring different approaches by governments and by international organizations as vaccines race against new variants of COVID-19 (The Economist 2021a).

These developments amplify the tension between policy responses that tend to be national and a virus that does not respect jurisdictional borders. In turn this has raised the risk that governments engage in Vaccine Nationalism, taken to be zero-sum steps that come at the expense of the public health of the populations of other nations (Bollyky and Bown 2020, Freund and McDaniel 2020).

Vaccine Nationalism can take the form of overt export bans or limits—that aim at increasing domestic availability of vaccines at the expense of foreign supply—or they can take less transparent but often equally effective forms. Subtle mechanisms that are available to governments of vaccine producing nations include delays in shipments and conditioning delivery abroad on imports of vaccine from other production locations (Evenett 2021a). Finger-pointing between governments in February 2021 highlighted the potential for both covert as well as overt limits on vaccine exports.

Whether the world trading system will fail its COVID-19 vaccine-related stress test will depend on the incentives confronting governments. A potentially important factor in this regard is the existing pattern of cross-border value chains involved in the production and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. A government that pre-ordered vaccines from producers located abroad may think twice before curtailing exports of vaccines or vaccine ingredients manufactured at home.7 This is suggested by the broader hypothesis in the international trade and business literatures that the presence of cross-border value chains reduces the incentive of governments to engage in protectionism (Gawande et al. 2015;Blanchard et al. 2017, Baldwin 2018, Krugman 2018, World Bank 2020).8 Could vaccine-related value chains provide a bulwark against Vaccine Nationalism, to the benefit of populations at home and abroad? If so, during the current pandemic this particular configuration of international business would have broader societal as well as commercial benefits by inducing governments to keep trade routes open. The backdrop to these vaccine-related developments is the return of geopolitical rivalry and associated Economic Statecraft (Baldwin 1985; Aggarwal and Reddie 2020, 2021), which may color the policymaking calculus.

Recent actions and statements by large trading countries make clear that the risk of export curbs on vaccines and vaccine ingredients cannot be discounted. The purpose of this paper is to examine the degree to which international value chains implicated in the production of COVID-19 vaccines satisfy the necessary conditions to temper resort to this form of Vaccine Nationalism—between states where final vaccine manufacturers are located, between final vaccine manufacturers and producers of vaccine ingredients, and between states within and outside the COVID-19 vaccine value chains.

We use information from detailed regulatory filings to identify the key ingredients of COVID-19 vaccines, other ingredients that are used in vaccine production, and selected products used for distribution (Annex Table 1). We then draw upon a number of commerce-related data sources—monthly customs data for the EU, annual global trade flows data from UNCOMTRADE, and firm-level data on pharmaceuticals’ headquarters and affiliates from Orbis—to obtain a picture of the supply chain of COVID-19 vaccines. The data clearly point to high concentration and self-reliance in COVID-19 vaccine production among a group of 13 countries9 that we refer to as the “COVID-19 Vaccine Producers’ Club” or simply the “Vaccine Club”.10 These countries are not only where the headquarters of the companies currently producing COVID-19 vaccines are found—they are also where 91% (783 out of 857 subsidiaries worldwide) of the subsidiaries of these companies are located. They also account for 60% of total confirmed advance purchasing agreements with pharmaceutical companies for vaccine doses.

The trade data show that vaccine producers are both the main source and destination of exports of COVID-19 vaccine ingredients, especially when we narrow down the analysis to key ingredients. Trade data for the 2017-19 period show that vaccine producers sourced 88.3% of key ingredients from other vaccine producers. The shares of imports of key ingredients from other vaccine producers as a group ranged from a low of 76.4% (India) to 98.7% (United Kingdom). In contrast, 68% of vaccine producers’ imports of all goods came from the Vaccine Club. The two top exporters of key ingredients are the United States and the European Union, which accounted for half of total exports, followed by United Kingdom, Japan and China with significantly smaller shares. Monthly data for the European Union show that extra-EU imports and exports of vaccine ingredients took off sharply from the second quarter of 2020. Extra-EU imports grew faster from vaccine producers than from non-vaccine producers, strengthening the dependence of the European Union on the Vaccine Club—a pattern that would most likely apply to other vaccine producers as well.

What are the implications of the current structure of the COVID-19 supply chains for trade policy and the production and distribution of vaccines worldwide? To differing degrees, members of the Vaccine Club have leverage over other members; that is, they can retaliate along the COVID-19 vaccine supply chain. Governments outside this club, which constitute the overwhelming majority of nations, have no such leverage. However, other options are available to the latter nations (a statement of fact rather than an endorsement, as will become clear.) The existence of differential options may account for differences in how governments across the world react any outburst of Vaccine Nationalism, the risk of which will remain so long as glaring excess demand for COVID-19 vaccines remains unmet.

Our analysis yields four types of recommendation for both the private sector and the public sector. Although trade policies are implicated and should be carefully monitored, trade policy alone cannot eliminate the shortages of COVID-19 vaccines. We urge that particular attention be given to the private sector incentives involved, including the way government policies affect those incentives and have been shaped by unfortunate legacies from the past. We also identify a critical coordination problem that the creation of a clearing house could alleviate. The transfer of tacit knowledge—as opposed to ceding codified knowledge in the form of patents—between vaccine creators and vaccine manufacturers has been identified by numerous experts as essential to ramping up COVID-19 vaccine production. We therefore discuss means by which that knowledge can be transferred and the attendant capabilities of developing countries nurtured. As such, our approach departs from those seeking to suspend certain multilateral trade disciplines on intellectual property rights.

Our focus on the location of producers of COVID-19 vaccines and their ingredients, and on the resulting international trade between nations, addresses only one facet of the global distribution of vaccines needed to quell the current pandemic. Other recent analyses have emphasized different aspects of the global distribution of vaccines including transportation and trade facilitation challenges (ADB 2021; OECD 2021); the role of national and international intellectual property rights regimes (Abbott and Reichman 2020; Mercurio 2021; Nicholson Price, Rai, and Minssen 2020); allocation, affordability, and deployment of vaccines (Wouters et al. 2021); and the incentives created when procuring vaccines (Ahuja et al. 2021).11

Moreover, the ongoing race to develop and ramp up production of vaccines should be seen in light of longstanding concerns about the strength of private sector incentives to develop vaccines (Xue and Ouellette 2020) and the legacy of societal responses to previous pandemics, including the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic of 2009-10 and the West African Ebola virus epidemic of 2013-16. As will become evident, actions taken during the latter two episodes are likely to have influenced public and private sector decision-makers this time around.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section outlines the current risks of policy-induced delays to vaccine exports and finds them credible. The third section deploys empirical evidence consistent with the existence of a club of COVID-19 vaccine producers. The fourth section discusses the policy implications of such a club and infers several implications for policy and the design of international cooperation. Concluding remarks on the impact of cross-border value chains on Vaccine Nationalism are offered in a final section.

The-Covid-19-Vaccine-Production-Club-Will-Value-Chains-Temper-Nationalism

To read the original report from the World Bank Group, please click here

International Labor Organization: Returning to the Core Business of Defending Workers

The focus of the International Labor Organization should be to champion the “freedom of workers to flourish.” This is best done not through heavy regulation but by guaranteeing basic rights and protections that are universally observed and allowing nations to adopt and adapt details to their unique circumstances. The ILO practice of promulgating standards in a voluntary manner and serving as a forum to combat the worst forms of labor abuses serves U.S. interests. If the ILO departs from this approach on conventions and recommendations or if it allows political agendas tangential to its core mission to overwhelm its original mission and purpose, it should jeopardize U.S. support.

BG3587

To read the original report from the Heritage Foundation, please click here

William Krist's Blog