Dory Codington's Blog, page 4

May 6, 2014

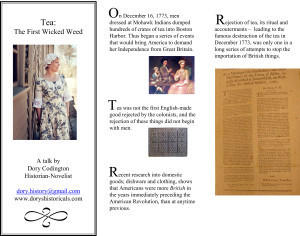

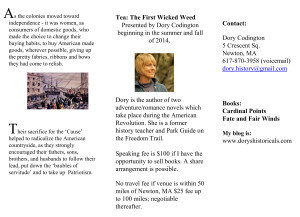

Tea the First Wicked Weed

I have been working on a talk for libraries and groups about how Tea; the buying, preparing and drinking, became a symbol of all things British and therefore rejected as colonists began to separate from their mother country. It’s loads of fun to think about and I am making a shiny pink dress (gown) just for the project. Here is the brochure:

February 13, 2014

Ice and Snow in 1773

In December 1773, John Rowe wrote in his diary:

Dec 26. Exceeding windy & stormy – it Blown down many Turrets & done Damage among the Shipping at Long Wharff & Tillstons & Blown off the Tiles from my house.

Many New England diaries include weather notations as a matter of course, but in this diary either Mr. Rowe did not include weather notes, or the editor took them out. That this notation made it into the edition published by the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1903, makes it doubly interesting.

Below is the section from Cardinal Points I wrote using Rowe’s diary:

Below is the section from Cardinal Points I wrote using Rowe’s diary:

Oona had walked to the Common to watch the sun set over the marshes of the Back Bay. The walk back over Fort Hill was made treacherous and plodding by a harsh storm that started just as she turned toward home. She pushed back the hood of her cloak so she could see against the driving sleet. She was happy for the warm fisherman’s cap and sweater Jason had left, the thick lanolin soaked wool was warm and waterproof against the cold and wet. She lifted her face to the stinging ice and steadily increasing gusts, loving the howling wind and the energy of the storm. Hours later, alone in her room after the long day, she looked out the attic window, the wind had picked up and was roaring now. The reflected light from the thick clouds and white ground showed that ice had begun to stick and accumulate on every tree limb, roof, and mast.

The Nor’easter raged all night and all of the next day. It was Sunday, but no one ventured out for church. The ground was a solid sheet of ice, too treacherous for horses’ hooves, or a walker on anything but the most important errand. With each gust of wind, another heavy, ice coated limb crashed to the ground, making the world even more treacherous. Someday, Oona thought while staring out the window, when the sun came out again, this dull gray world will be changed by the ice, snow and freezing rain into a shiny, sparkling otherworld.

And so it was Monday morning that people emerged from their hearths to get on with their week. Frozen mud and brick walks, coated with a day’s worth of accumulated ice greeted them. Oona, like other brave souls ready to face such a day, held tight to her stout walking stick as she maneuvered through town. Like everyone she stepped gingerly, but it was the sight overhead that captivated her. The clouds had cleared away for bright winter light that caught the ice on every surface and brought it to an unearthly life. Nothing looked as it had before. Things like tree limbs, window shutters, shop and tavern signs – glittered in the bright light, moved unnaturally in the wind, broke loose from their anchors and simply shattered when they hit the ground. As the morning progressed and no heat could be coaxed from the sun to melt the layers of accumulated ice, a new wind arrived from the harsh north. Gusts from this frigid wind took the ice covered trees and ships’ masts and snapped them like twigs.

Oona headed home with bread, eggs and stew beef for dinner. She was pleased to have made it home and not slipped and fallen on Mrs. Channings fresh eggs. Back in the warm kitchen on Oliver Street, she put down her bundles and pulled off her cloak and warm undergarments. “Mrs. Prince, it’s bad down at the harbor. Masts broken, ships on their sides. I didn’t see the Catherine, but I don’t see how she could’a come through with nothing. Leastways, not completely. None of them did.”

“Don’t tell the master.”

“Don’t tell? Why not?”

“If he goes out now and gets hurt on a fall, mistress will blame you. I think she is quite angry enough over Peter Church.”

“Really? Did something new happen?”

Mrs. Prince poured two cups of chocolate and sat Oona down for a chat. Nothing had happened. But there was no reason to upset Anne Goodiel, or make Matthew run out before the streets were cleared. The cook was absolutely right.

February 4, 2014

Lewis Hayden of Boston

In honor of February I got a great email from Kirsten Hughes, the Chairman of Mass. GOP. She writes of the extraordinary life of the first African-American Massachusetts’ State Legislator, Lewis Hayden, Republican of Boston.

In 1844, Hayden, along with his wife and son, fled from the constraints of slavery in Kentucky to become a fugitive and key participant in the abolition movement. Lewis, eventually settling in Boston, facilitated the escape of many other slaves through the Underground Railroad.

In 1844, Hayden, along with his wife and son, fled from the constraints of slavery in Kentucky to become a fugitive and key participant in the abolition movement. Lewis, eventually settling in Boston, facilitated the escape of many other slaves through the Underground Railroad.

The Lewis and Harriot Hayden House on Beacon Hill, which still stands today, served as a refuge for those escaping to their freedom.

Hayden began his political career after being appointed as a messenger in the Secretary of State’s office. He was then elected as a Republican representative for Boston. His most notable contribution to the city is the statue of Crispus Attucks, the African American* who was killed in the Boston Massacre in 1770, at the start of the American Revolution.

The transition from slave to elected official in one lifetime shows the strength of character and the power of initiative in this remarkable man. Representative Hayden refused to allow discrimination and socio-economic background stand in his way. His incredible journey reminds us that any American can rise to greatness and contribute to our democratic government.

A word about Crispus Attucks: there really is no proof that he was of African descent. Books have been written about him, schools have been named for him. The truth is we know virtually nothing about him, except that he was “dark skinned” and worked at the docks. It has been assumed he was half Natik Indian, and half African. He may have been from Framingham, Massachusetts.

January 18, 2014

Molasses Cookies and Gunpowder

In January of 1919 an enormous tank of molasses on Commercial St. in the North End of Boston burst. This disaster spewed hundreds of gallons of molasses into the streets, killing and maiming nearly two hundred people and horses and moved entire buildings off their foundations. This is a famous story, at least one definitive book has been written on it. I will leave known history severely alone and tell a different story. A sweeter one – of Boston, molasses, sugar and chocolate.

In January of 1919 an enormous tank of molasses on Commercial St. in the North End of Boston burst. This disaster spewed hundreds of gallons of molasses into the streets, killing and maiming nearly two hundred people and horses and moved entire buildings off their foundations. This is a famous story, at least one definitive book has been written on it. I will leave known history severely alone and tell a different story. A sweeter one – of Boston, molasses, sugar and chocolate.

To do this some historical background is necessary.

Most of colonial America developed along a pattern, known as the Virginia model, of agriculture and extraction. Highly successful because land was fertile, cheap and plentiful. So was labor, mostly due to indentured and enslaved workers.

New England Farms grow rocks and children.

The New England colonies could not follow a model of agriculture and extraction. Labor was expensive because of available work on ships and at docks, and because the region’s thin rocky soils produced barely enough food to feed large families, certainly not enough to maintain a labor force that wasn’t needed anyway. This subsistence farming was the result of geology. From 30,000 to 10,000 years ago, the Wisconsin ice sheet, about three miles high, pushed rocks from upper Canada into New England rearranging everything in its way. Boston Harbor, the Blue Hills, Cape Cod, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and Long Island, NY are the nearby, obvious result of this ice. The size and shape of the north eastern mountain ranges, and the dearth of native rhododendrons are a few others.

While the ice took away to soil, it left deep harbors (and a never-ending supply of field stones that decorate the sides of roads and foundations for most of the region’s houses.) But before we move onto sweeter things, there is one extractive thing the mother country needed very badly: New England hardwoods for ship building and tall white pines for ships’ masts.

Molasses??

In brief, he who can make a leak-proof ship, can make a barrel that doesn’t leak. And New England shipyards produced the best fitting, leak-proof barrels and barrel staves in the colonial world. This was good because although the British Colonies in the Carribean tried to make sugar into cones from the cane they grew, the tropical heat caused the raw sugar to return to its drippy, syrupy state. Fortunately for the sugar producers of the Caribbean, barrels of dried cod, quickly returned to Boston with drippy molasses that was refined into sugar in the reliably cool New England town of Boston.

So Revere Sugar, Baker’s and now Taza chocolates, and of course Lindt and NECCO are not coincidentally located within reach of Boston, neither was the molasses tank that exploded on Jan 15, 1919, but for that you need to understand how molasses was made into smokeless gunpowder for use in WWI, and I’d rather make cookies.

Interesting fact. Dried cod is still used in many Caribbean dishes, a leftover from colonial times.

December 25, 2013

Christmas in Colonial New England

To think about Christmas in Colonial New England, we first must remember that colonial New England encompasses a region over a very long time. The Plymouth Colony began in 1620, Salem, Massachusetts was settled in 1627, and Boston in the Massachusetts Bay Colony was settled in 1630. Colonialism ends with the beginnings of the American Revolution in 1775. That is one-hundred and fifty years, give or take a few. Nothing stays the same for seven generations, not even in New England.

In the seventeenth century the devout Protestants who settled these places, did not celebrate Christmas. There are a few reasons for this. For instance, Cotton Mather, one of Boston’s leading Puritan ministers of the time, expressed the opinion of most when he preached that Christ’s birth should be celebrated every day. But really these first ministers were worried and opposed to the dual pagan holidays of Yule and Saturnia. Yule being the Anglo-Saxon worship of the darkest days of the year, and the return to lengthening days and increasing light. In other words the winter solstice. Saturnalias were what we now associate with New Years, the loud raucous -drunken worship of the god Saturn; the end of one year and beginning of another.

So Christmas worship was frowned upon. In many places it was another work-day, in others it was a day of prayer and contemplation.

But Colonial New England extends over one-hundred years, and many things changed over a century and a half, among them Christmas celebrations. Yes change even happened among the most religious New Englanders. It happened slowly, with the Anglofication of New England, and quickly as new people with different and more light hearted ways of doing things moved in to the region.

It is well known that America was never more English than it was just at the time of the Revolution. Colonists had adopted many English customs as travel time lessened, and more English goods were available in the marketplace. Those customs began to include boughs of evergreen and holly in the house, Christmas parties and church services dedicated to the birth of the Christ child.

At the same time America was becoming more English, more Germans immigrated to America, making up the second largest immigrant group in colonial America. Although most settled in the mid-Atlantic region, many moved north and settled in New England towns. These newcomers brought many of the things we today associate with Christmas, such as candles in the windows, gingerbread houses and men, the work cookie, and eventually – in another one-hundred years, the Christmas tree. (The first of these was erected in 1832 in Lexington Massachusetts, so the story goes, by a Unitarian minister, a German named Charles Follen.)

So the quick answer to: how was Christmas celebrated in Colonial New England? Is that it wasn’t, and then it was.

December 16, 2013

Boston Harbor a Teapot Tonight : December 16, 1773

December 16 two-hundred and forty years ago, that’s 1773, a gang of seamen and mechanics, Boston harbor’s working men, after listening to debates and lectures for nearly four weeks, dumped million’s of dollars worth of East India Company tea into Boston Harbor. This event was originally called ‘the destruction of the tea,’ and over the years it has come to be known as The Boston Tea Party. (Not to be confused with a former rock ‘n roll venue of the same name.)

December 16 two-hundred and forty years ago, that’s 1773, a gang of seamen and mechanics, Boston harbor’s working men, after listening to debates and lectures for nearly four weeks, dumped million’s of dollars worth of East India Company tea into Boston Harbor. This event was originally called ‘the destruction of the tea,’ and over the years it has come to be known as The Boston Tea Party. (Not to be confused with a former rock ‘n roll venue of the same name.)

The arguments the men, women, and children heard, involved much talk of ‘taxation without representation’, and a governor who was out of touch with the needs of the Province. He, of course, was an employee of the King, and knew it. The issue being discussed was over three ships in the harbor. By statute, they had to be moved that night, and it was Governor Hutchinson’s decision either to land the tea, that was unload it, or allow the ships to sail out of the harbor and back to London.

Most of Boston wanted the tea sent back. By itself that was contentious. Boston was the largest and busiest port west of Plymouth, England, and busy, profitable ports are not in the habit of sending ships back where they came from without an exchange of goods. But that was exactly what the citizens of Boston were clamoring for. And it wasn’t even over the tea.

Not over the tea? No, non-importation agreements had been in place for years by then. These were agreements that town meetings had voted on and signed throughout New England, promising that British made goods would not be sold, purchased or consumed. Tea had been politically and socially too hot to drink or handle for a decade, and no one protesting the tea-ships had sipped a cup for years.

What then? Thomas Hutchinson, the man who was to decide if the ships were to stay or go, had already decreed that only a few shops in Boston would sell the East India Company tea sitting in the harbor. And not surprisingly the owners of those few shops were friends and relations of Gov. Thomas Hutchinson. So when the Governor sent word that the ships should be brought in, unloaded, and the tea brought to the approved-merchants’ warehouses; no one was surprised. It was after Hutchinson’s order was given, that Samuel Adams stood at the pulpit at Boston’s Old South meetinghouse and gave the sign that sent the disguised workmen down Milk Street to the harbor to dunk the tea.

Adams said: “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country!” the men responded “huzzah” and “Boston harbor a tea pot tonight”. And off they went.

People from Rhode Island and North Carolina have pointed out on Facebook and other places, that it happened at their ports too. They are correct. But it wasn’t what Bostonians did that night that started the American Revolution, it was what Parliament did in response to the tea’s destruction that started the war. It was Parliament’s efforts to punish Boston with a series of laws now referred to as the Insufferable Acts, which caused worry in the Massachusetts countryside, and in the other twelve colonies. Their worry, and their efforts to save the townsfolk of Boston, changed gangs of young rebels, into a unified nation of Patriots. Patriots, who with a common cause, organized against the government of King George III and started something amazing.

December 12, 2013

Cardinal Points:Review from InD’tale Magazine

Cardinal Points

Dory Codington

✮ ✮ ✮ ✮

Born the fourth son of a Duke, Jason FitzSimmon grew up knowing he would have to find his own way in life. The sea and the freedom it held became that way. While working his way up the ladder of command, Jason realized his best opportunities lie in America, so he takes a chance, relocates to the shipping town of Boston and hires on with a local merchant shipping magnate. From the moment he enters his boss’ home, however he is mesmerized by a beautiful serving girl.

Oona had been an indentured servant since she a child. After almost ten years of service, she is finally approaching freedom – if she can just abide by the strict rules set by her employers. One of them is no private indiscretions with men. But, one look at Jason and Oona recognizes his beloved face from her past. How can she stay away? Yet, if she doesn’t she risks everything she’s worked for her entire life.

This story is a delicately woven mix of history and romance. Both are done with exquisite care and understanding, both are intricately woven into the soul of the reader. Because of this the historical aspect becomes a very large focus of the story so those who are not committed history buffs may get decidedly bored at times. The relationship between Oona and Jason is definitely worth the read, however! Watching a forbidden love grow as the American revolution gears up is both exciting and riveting. Although Jason’s nonsensical choices near the end leave the reader scratching their heads rather than sighing in satisfaction, this committed historical is definitely a keeper.

Ruth Lynn Ritter

http://www.indtale.com/magazine/2013/december-january/#?page=72

November 16, 2013

American Georgians: Novels in the time of George III and George Washington

Readers prefer Regencies. I write American Georgians. (An open letter to author Jo Beverley)

Readers prefer Regencies. I write American Georgians. (An open letter to author Jo Beverley)

Recently I read an interview with an author of Medieval romances. She spoke of the era as lawless, and that the lack of social rules made some readers shy away from that genre, but she liked writing in a period that allowed a man and a woman to be discovered in a room together without scandal or forced marriage. That was just one of many reasons she liked this relatively chaotic world where the only law was the King’s word and he and his armies were largely absent. I agree that such times open up areas of romance and relationships to an author, that the rigid rules of the Regency cannot allow.

A few years ago I began writing about another chaotic, lawless era. Not lawless because the law was absent, though often it was, but because the known world was changing so quickly that rules seemed suspended. This is a short essay on how I began writing my Edge of Empire / World Turned Upside Down Series or the American Georgians, if you will. (George III and George Washington.) The novels take place during the American Revolution 1773-1780 plus or minus a plot point.

It all began when Jo Beverley’s Rothgar, mentioned ‘trouble in the colonies’ in conversation with his younger brother. Being an American historian with a deep love for, not only British history, but British historical romances, my antennae went up and I matched the “trouble” to the stamp crisis in Boston. Then Chastity discovered Cyn’s tomahawk-scar from an attack during in the Seven Years War in Canada or perhaps Massachusetts or New York. That is a war we in America call the French and Indian War. For us, this war began with Indian attack in 1675 and didn’t end until the treaty of Paris in 1765, even then there were attacks from Canada into western New York for another year. In those years, Americans were British, and army and militia fought together against the French and the Canadian Indians.

No nonfictional family explains the emotional conflict the American Revolution presented to the British aristocracy better than the Howes. Cousins of King George III, (their mother was an avowed illegitimate daughter of George I). Three brothers served in America during the French and Indian War. The oldest, General George Howe, led forces in New York, and died at Ticonderoga in 1758. He is buried near Albany, New York. He was greatly adored on both sides of the Atlantic and after his death the Province of Massachusetts paid for a commemorative plaque in his honor to be placed in Westminster Abbey.

In 1774, as the next crisis in the colonies heated up, George III asked General William and Admiral Richard Howe to go back to America to lead the Army and the Naval forces there. They agreed only if they would be allowed to seek reconciliation with the colonies. The King agreed, but he and his secretaries gave them no support.

With the inspiration of Ms. Beverley’s Malloren novels, and the fighting of the pro and anti Americanists in Parliament as background, I constructed a fictional aristocratic family and the fictional Duchy of Chardon. The FitzSimmons are a large loving family with too many sons, two of whom I quite rudely remove from Britain, and place in America at the time of this conflict. One is a merchant seaman who lands in Boston the week of the “Tea Party” the other is a lieutenant on General Howe’s staff. A younger brother will come to visit as soon as he finishes school.

Their mother, Elizabeth FitzSimmon, Duchess of Chardon, is an energetic redhead who has been involved in the raising of her children from their birth, and running all aspects of her household. She argues politics with anyone who will listen, and writes to the newspapers as Queen Bess. She visited family in America, some time in the past, and loved the land and its people. She is a cousin of General John Burgoyne, who lands in Boston with William Howe in the spring of 1775. And is not shy in telling him he is a buffoon when he does not believe the Americans on the frontier will fight hard and well.

The two oldest brothers, Robert and Stephan sit in Parliament. Robert takes his father’s seat in Lords, because the Duke won’t travel anymore, and Stephan was elected as an MP for the district. Both men are sympathetic to the American cause, as were many others to greater and lesser degrees. Historian, David Hackett Fischer refers to this as the King in Parliament Whigs, (the British), vs. the no King in Parliament Whigs, (the Americans), the two sides agreed on almost everything except that one thing, and it was insurmountable.

Three family members: Stephan; Thomas, the third brother; and the husband of their sister Elizabeth, own a shipping company named after the family. Jason, the fourth son, has been in the employ of this company as first mate on the Chardon. The first book begins as he is makes landfall at Boston, Massachusetts, December 1773. Simultaneous to the treasonous events of the night, be decides to leave his brothers’ employ and strike out on his own.

John’s story begins during his travels. He had been tasked by General Howe to come to an understanding of the Americans, in order to help the Howes, William and Richard, with the attempt at reconciliation. John lands in Philadelphia at the time of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. He is fiercely loyal to the King and the notion of nationhood, but grows to believe that Parliament has betrayed the English ideal of representative government with their attitude toward the Americans.

So, these are the stories of the extra sons, as a new world unfolds before them. Each man meets an American girl. In Boston Jason meets Oona. An indentured Irish servant who has lived in Boston since she was ten. She has no family, a vulnerable woman in a town under siege, but she is smart, and rightfully proud of her abilities. And in Philadelphia John meets the angry and rebellious Rebecca, a farm girl from a large family, who is trying find her path to independence and safety in a topsy-turvy world even as the British Army moves onto her farm to quarter.

What I have tried to do in these books, beside giving the reader a fun story with adventure and romance, is to complicate the narrative of the American Revolution. To tell the story, not through military victories and losses, but through the eyes men and women finding love in the midst of rhetoric and revolution.

When General Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington in October 1781, he had his band play a tune called “World Turned Upside Down.” For an Enlightenment Englishman of that time, losing the colonies was not simply the loss of valuable real-estate, but an alteration of the way things should be in an ordered world. Quite literally, the known world had ended.

As I say on my book covers: In a world turned upside down, the only right – may be love.

November 13, 2013

Thanksgivings

In the early days of the Commonwealth, the Colony of Massachusetts, the residents believed themselves to live in a covenanted society. This is an Old Testament philosophy that tied residents to one another and the community to God. Although the Puritans, and the Separatists, (the Pilgrims of Plymouth) differed slightly in their practices, they were Calvinists who believed that the actions of one person would effect God’s blessings or lack thereof on the entire community.

It is this belief, that the every individual was responsible for the welfare of the whole, that led to fast days and thanksgivings, and these were called regularly by the General Court, which is now the Massachusetts Legislature.

Fast Days were called when calamities, such as Indian attacks and battles during the series of wars that began with the King Philip’s War 1675 and concluded with the War for Independence, (1775-1781) occurred. Disease epidemics, flood, drought, and particularly bad winters were also reasons for fasting. Fast Days were spent at the meeting house and little food was eaten, as all human needs were replaced with prayer.

Fast days became less religious over time, and many towns offered speakers at local Atheneums rather then fasting at the local church. They disappeared from diaries, no longer mentioned by the early nineteenth century.

Thanksgivings were born from the same tradition as were fast days. Thanksgivings were called by the General Court for successes and survivals; the end of a drought, soldiers safely home from war, harsh winters endured or soft, mild winters, and most famously bountiful harvests. These were as religious as the Fasts, days of thanking a generous God for the bounty of His love and whatever blessings He had bestowed.

The pattern of legal Thanksgivings follows that of Fast Days, called by the General Court whenever occasion warranted during the early years of the Commonwealth, and becoming fixed at two per year by the beginning of the eighteenth century. According to the diaries, by 1704, the two Thanksgivings were fixed at – the first Thursday of April, roughly the Massachusetts state holiday known as Patriot’s Day, and the end of November or early December – today’s Thanksgiving holiday. (The New England Puritans did not celebrate Christmas, believing that every day was given over to the celebration of Christ’s birth.)

So whatever happened in the Plymouth Colony in 1621, and whatever FDR did to create this holiday in the rest of the nation to help stores sell their Christmas goods, Thanksgiving was a religious and state holiday in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts that began in 1630 and was gifted to the rest of the nation by Sarah Josepha Hale after the Civil War and by FDR in 1939.

November 5, 2013

Guy Fawkes Day

Known as Pope’s Day here in Boston, it was a day of pub hopping and the burning of effigies of the Pope and all sorts of political enemies. I am pasting Nicola Cornick’s bit here:

Bonfire Night grew out of the celebrations that King James I had survived the attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605 in the gunpowder plot. It was a festival that started immediately after the event - Londoners lit bonfires in the streets to celebrate the fact that the King’s life had been spared. The following year, 1606, The Observance of 5th November Act came into force and made November 5th a public holiday. Thanksgiving events up and down the country formalised the celebration with food and drink, music, artillery salutes and gunpowder.

One of the fascinating things about Guy Fawkes Night is that it changed and developed as a festival down the centuries. It has a complex history as an anti-catholic protest at times and also as a festival celebrating parliamentary government. During the early 19th century in particular the day was often an excuse for rioting and disorder. The Victorians tamed Bonfire Night and made it a focus for organised celebrations once more.

One of the fascinating things about Guy Fawkes Night is that it changed and developed as a festival down the centuries. It has a complex history as an anti-catholic protest at times and also as a festival celebrating parliamentary government. During the early 19th century in particular the day was often an excuse for rioting and disorder. The Victorians tamed Bonfire Night and made it a focus for organised celebrations once more.

These days there is a danger that Bonfire Night, a fire festival that perhaps took on the guise of Samhain and in its time eclipsed Halloween, is in eclipse itself. But one thing about our traditions is their ability to change and adapt with time. Guy Fawkes isn’t beaten yet!

In 1776 George Washington had a situation on his hands. The bulk of his troops at Cambridge came from New England. They were deeply Protestant and had spent many years fighting the French in the backwoods and Canada. The General got wind of their traditions, which of course included burning a dummy in Pope’s robes. The problem was he had the Marylanders to keep happy. They were Catholic and fierce Patriots willing to die for Washington and the Cause.

Washington called the New Englanders into a conference and laid out the problem, probably very sternly. They came through and kept the celebrations under control. No lashes were needed and no one was offended.

Happy November 5.