Victoria Noe's Blog, page 11

April 5, 2017

Five Things I Learned Interviewing People for My Books

greenhouse.io

greenhouse.ioWhen I started work on the Friend Grief series, I was only sure of one thing: they would be a mix of interviews and research. They would tell the stories of men and women who struggled to deal with the death of a friend; sometimes many friends.

The first time I ever interviewed anyone was in 1976. I was in New York doing research for my master’s degree project, the development of director-choreographers in American musical theatre. I sat in Bob Fosse’s living room near Carnegie Hall and discussed his career. I don’t remember much, though I’m sure my notes are in a box somewhere. But he was gracious with his time, and for that I’ll always be grateful.

I didn’t have much experience interviewing people again until about 2010, when I began working on my books. I thought I was prepared, but as it turned out, I had a lot to learn: about interviewing, about grief, about people.

The series ended in 2016, so now I’m interviewing women for my next book (Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community). As a rule, a person’s sex life is none of my business. But in this case, it leads to the most awkward interview question ever: “Are you straight?” So that’s the biggest difference from earlier. In New York and Washington, DC recently conducting interviews, I began to really appreciate what I’ve learned:

You don’t need a degree to interview people. I was frequently asked at the beginning what my credentials were for writing about grief. None, I admitted, other than my own experiences. I felt uniquely unqualified. I was afraid that people would refuse to meet with me because I wasn’t a therapist or grief counselor. But as it turned out, that master’s degree in theatre was an advantage. They knew I wasn’t there to diagnose them. I wasn’t there to prescribe treatment or judge them. I had no particular agenda. I was just there to listen. And that gave them the permission and freedom to bare their souls

It’s okay to cry. The first person I interviewed for my books was Roseanne Tellez, news anchor on the CBS TV station in Chicago. She talked at length about her on-air partner, Randy Salerno, and the impact of his death on her work and personal life. She stopped three times because she started to cry. I was mortified that I was responsible, that I upset her that much. But now I can look back and see that fully 1/3 of the people I interviewed cried at least once. I thought the percentage would drop with this book, but it hasn’t. If anything, it’s closer to 1/

All the senses are important. As part of Women & Children First’s renovation crowdfunding campaign, I scored a non-fiction class with Rebecca Skloot, acclaimed author of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. We talked of many things that night, but the one that stuck with me most was about interviewing. She suggested taking pictures of the room where you hold the interview to reference later on. I don’t usually take pictures, but in my notes is a description of the location. For example, when I interviewed women last fall at the Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS office overlooking Times Square, I made note of the distracting advertising outside the windows, the size of the table in the conference room, the lighting. Other interviews have taken place in the back of a diner, an office at police headquarters and once in a hotel AV supply room (we were desperate for a quiet space). But it’s all part of the experience

Men really do talk. I went into this process believing that interviewing men would be like pulling teeth. I bought into the stereotype of men who don’t share their feelings, which made no sense: not only were they letting me interview them, some asked to be interviewed. I was armed with a list of thirty questions the first time I interviewed a man. I assumed, arrogantly, that we’d be done in about fifteen minutes. An hour and a half later, we were on question #3. He was not the exception. He was the rule. The only interview that was less than 90 minutes was one that was in two parts (which totaled 90 minutes). Again, they knew I was there to listen, not judge. Once they started to talk, it was hard to stop. Many followed up with more information. So, mea culpa

Everyone wants to be heard. “I can’t believe anyone cares about this,” was a frequent objection from interview subjects. There is no greater compliment you can give someone than to listen. You may not agree with them. You may not truly understand or appreciate what they’re telling you. The latter is true of some of the people I interviewed. It wasn’t until later, when I listened to the recording, that I heard what they were really saying.

I’ve learned a lot from the people I interviewed. I’ve learned about emotional pain that brings you to your knees, about grief that never completely goes away, about the infinite joys of friendship and making a difference in your community. I try to keep my mouth shut and just let them talk, but sometimes the interview becomes more like a conversation between friends. And I think that’s okay, too.

It would be a lie to suggest I’m comfortable on the other side of the interview table. I worry about what the next question will be, if I’ll be able to answer it without stumbling. But now I think I’ll try to concentrate on being as honest as the people who trusted me to tell their stories.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

March 28, 2017

Women’s History Month – AIDSWatch

I planned to turn over my blog again this week to another straight woman in the AIDS community. That particular post will have to wait a bit. Instead I thought it would be better to report on my day (the first of two) in Washington, DC at AIDSWatch. It’s no accident, in my mind, that the conference is presented by the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, named for once of the fiercest advocates in the history of the epidemic.

I planned to turn over my blog again this week to another straight woman in the AIDS community. That particular post will have to wait a bit. Instead I thought it would be better to report on my day (the first of two) in Washington, DC at AIDSWatch. It’s no accident, in my mind, that the conference is presented by the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, named for once of the fiercest advocates in the history of the epidemic.

I went last year, joining a few hundred people from around the country to advocate for funding and legislation important to people living with HIV and AIDS. It was my first time lobbying in the capitol since 1989, when I advocated for the first Ryan White Care Act. A lot had changed in 27 years. This year, though, is very different.

The radical changes in government at the federal level, coupled with a resurgence of activism for a variety of causes, resulted in a sell-out crowd of well over 600 activists this week. We trained today for the visits on the Hill tomorrow. Though the American Health Care Act was defeated on Friday, that was just one battle in an ongoing war to protect people with and at risk for HIV.

So what does that have to do with women?

I talked to a number of women today (that’s me with the amazing Wanda Brendle-Moss). Some of them will be in my next book (Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community). The issues facing straight women in the community haven’t changed all that much since the beginning of the epidemic:

I talked to a number of women today (that’s me with the amazing Wanda Brendle-Moss). Some of them will be in my next book (Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community). The issues facing straight women in the community haven’t changed all that much since the beginning of the epidemic:

The challenges of convincing straight men to commit to safe sex with them all the time.

The pain of living in an abusive relationship, without the power to protect yourself from infection.

The reluctance of women to put themselves and their health first, when others are dependent on them.

The frustration of trying to find doctors who will treat them with accuracy and without stigma.

The ongoing desire to have healthy sex lives, regardless of HIV status.

The all-too-common emotional and physical burnout experienced by women who work and volunteer in the AIDS community.

The racism and misogyny that rear their ugly heads when you least expect it.

It can be a little depressing to read that list because in a lot of ways nothing has changed since the beginning of the epidemic. But the good news is plentiful and inspiring.

ETAF Ambassador Kelly Gluckman

ETAF Ambassador Kelly GluckmanThere is a new generation of activist: young women who demand healthy sex lives, who demand equal access to drugs and treatment, who demand that their voices – especially in advocating for women who are homeless, addicted, abused and scared – be heard. And that gives me hope.

“Not everyone knows what you know,” is something I say all the time to people who disparage millennials or other groups of young people. It is the responsibility of those who are older to share our experience and knowledge with those who will take our place on the front lines. At AIDSWatch I’ve seen a lot of women doing just that: sharing what they know, training younger women to end this epidemic once and for all.

I never thought AIDS would still be around when I reached this age. I never thought there would be a need – a desperate need – to head to Washington and our state capitols to demand continued funding for services that not only take care of those with HIV, but stop the epidemic in its tracks. And I never thought women would still be fighting additional battles – stigma, misogyny, abuse – that were all too common three decades ago.

But like I said, I have hope. The energy at the Marriott Georgetown could’ve lit up Times Square for weeks. I can’t wait to go up on the Hill and hear stories of others exercising their rights as citizens to advocate for issues that affect their lives. And I guarantee you, the fiercest advocates will be women.

As always.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

March 21, 2017

Women’s History Month – Susan Freed

Photo from The Advocate

Photo from The AdvocateIt’s natural for people to assume that my book (Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community) is about women who work(ed) in the community: nurses, social workers, researchers, nonprofit executives.

But a large number do/did get involved as volunteers. Maybe they were drawn in by the illness and death of someone close to them. Or they just saw an opportunity to make a difference: to build on the diversity of the community and give back. Los Angeles resident Susan Freed, a Bank of America vice president, shared her experience June 22, 2016 in The Advocate.

I just completed my third AIDS/LifeCycle, a 545-mile, seven-day bike ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Finishing this ride gave me an amazing sense of accomplishment. Every ride brings different experiences and emotions but each made me feel elated at the finish line. The AIDS/LifeCycle ride, the annual event to raise money and awareness in the fight against HIV and AIDS, is not an easy trek. During the journey, I was overwhelmed with feelings of comradery and love from not only my colleagues, but also a group of more than 3,000 riders and roadies from nearly every state and 17 countries.

Unfortunately, that feeling was stifled momentarily the morning after the ride when I heard about the tragedy in Orlando. As an LGBT ally, I was saddened, upset, and stunned by the news. It felt especially personal to me after spending a week with an amazing group of people celebrating diversity and inclusion.

Then I read about the outpouring of support and solidarity from communities around the world in the aftermath of the event. It reminded me of the sense of community I felt during AIDS/LifeCycle. Within the AIDS/LifeCycle “love bubble,” it didn’t matter if you were gay, straight, white, black, rich or poor — we were all just people acknowledging each other as people. You felt nothing but positivity, support, and respect. I truly can’t decide whether I learned more about diversity or inclusion during this ride.

The support also reminded me about the people I met during prior AIDS/LifeCycle rides over the years and the impact they’ve had on me. One of my fondest memories took place during the event. AIDS/LifeCycle was the longest bike ride I have ever completed, and it includes steep descents; I’ve always struggled with descents. Upon reaching a steep hill along the ride, I was terrified. My heart was racing and I didn’t know if I could do it. Everything that could go wrong crossed my mind. What if I ride off the cliff on the side of the road? What if I can’t stop? What if I hit gravel and fall?

A rider nearby must have noticed my anxiety because he came up from behind to offer words of encouragement. Another rider joined him, and then two became five. They were strangers who slowed down just to help me get down safely, and I will never forget that moment. This is what community is all about — supporting one another through a tough journey, whatever the journey may be. We make each other stronger and help each other do our best.

I thought about the colleagues I rode with for the past two years, along with countless other colleagues at Bank of America, especially as a member of its LGBT Employee Network. But more than that, I thought about the importance of diversity and inclusion, having volunteered for last summer’s Special Olympics in Los Angeles as part of Bank of America’s partnership with the World Games.

However, to find out that the bank was encouraging people to take seven days off to participate in the ride and allowing eligible associates paid time off to volunteer with nonprofits and at nonprofit events such as AIDS/LifeCycle was astonishing to me. We had 49 riders on Team Bank of America Merrill Lynch, the largest AIDS/LifeCycle corporate team for three years in a row. It was great to meet other employees that I would not have been able to know, from Nevada to Miami.

I have given a lot of thought to the reason I participate in AIDS/LifeCycle. I do it mainly because it benefits the San Francisco AIDS Foundation and the Los Angeles LGBT Center. These agencies continue to provide critical services and education needed to meet the growing needs of our community. Since the AIDS epidemic began in 1981, 1.7 million Americans have been infected with HIV and more than 617,000 have died of AIDS-related causes. In California alone there are 151,000 people living with HIV. More than two-thirds of all Californians living with HIV reside in Los Angeles County or the San Francisco Bay Area.

The hard reality is that people have AIDS, and people are sick. Although at times it’s really tough, all I have to do is move this bike, I can do that. Don’t get me wrong — it hurts, it hurts a lot, but it’s the least I can do in the grand scheme of things to help raise funds and awareness for those affected by HIV and AIDS. Ultimately, this brings more awareness to the other important issues that the LGBT community continues to face.

During this reflection, I realized more than ever just how powerful a diverse and inclusive community can be. My hope is that I can impact others and can foster an environment where everyone feels included and safe to be their true and whole self. I believe we’re on the right path, and I continue to hope we will get there because in the end, love wins.

SUSAN FREED is a Los Angeles resident and senior vice president at Bank of America

I just completed my third AIDS/LifeCycle, a 545-mile, seven-day bike ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Finishing this ride gave me an amazing sense of accomplishment. Every ride brings different experiences and emotions but each made me feel elated at the finish line. The AIDS/LifeCycle ride, the annual event to raise money and awareness in the fight against HIV and AIDS, is not an easy trek. During the journey, I was overwhelmed with feelings of comraderie and love from not only my colleagues, but also a group of more than 3,000 riders and roadies from nearly every state and 17 countries.

Unfortunately, that feeling was stifled momentarily the morning after the ride when I heard about the tragedy in Orlando. As an LGBT ally, I was saddened, upset, and stunned by the news. It felt especially personal to me after spending a week with an amazing group of people celebrating diversity and inclusion.

Then I read about the outpouring of support and solidarity from communities around the world in the aftermath of the event. It reminded me of the sense of community I felt during AIDS/LifeCycle. Within the AIDS/LifeCycle “love bubble,” it didn’t matter if you were gay, straight, white, black, rich or poor — we were all just people acknowledging each other as people. You felt nothing but positivity, support, and respect. I truly can’t decide whether I learned more about diversity or inclusion during this ride.

The support also reminded me about the people I met during prior AIDS/LifeCycle rides over the years and the impact they’ve had on me. One of my fondest memories took place during the event. AIDS/LifeCycle was the longest bike ride I have ever completed, and it includes steep descents; I’ve always struggled with descents. Upon reaching a steep hill along the ride, I was terrified. My heart was racing and I didn’t know if I could do it. Everything that could go wrong crossed my mind. What if I ride off the cliff on the side of the road? What if I can’t stop? What if I hit gravel and fall?

A rider nearby must have noticed my anxiety because he came up from behind to offer words of encouragement. Another rider joined him, and then two became five. They were strangers who slowed down just to help me get down safely, and I will never forget that moment. This is what community is all about — supporting one another through a tough journey, whatever the journey may be. We make each other stronger and help each other do our best.

I thought about the colleagues I rode with for the past two years, along with countless other colleagues at Bank of America, especially as a member of its LGBT Employee Network. But more than that, I thought about the importance of diversity and inclusion, having volunteered for last summer’s Special Olympics in Los Angeles as part of Bank of America’s partnership with the World Games.

However, to find out that the bank was encouraging people to take seven days off to participate in the ride and allowing eligible associates paid time off to volunteer with nonprofits and at nonprofit events such as AIDS/LifeCycle was astonishing to me. We had 49 riders on Team Bank of America Merrill Lynch, the largest AIDS/LifeCycle corporate team for three years in a row. It was great to meet other employees that I would not have been able to know, from Nevada to Miami.

I have given a lot of thought to the reason I participate in AIDS/LifeCycle. I do it mainly because it benefits the San Francisco AIDS Foundation and the Los Angeles LGBT Center. These agencies continue to provide critical services and education needed to meet the growing needs of our community. Since the AIDS epidemic began in 1981, 1.7 million Americans have been infected with HIV and more than 617,000 have died of AIDS-related causes. In California alone there are 151,000 people living with HIV. More than two-thirds of all Californians living with HIV reside in Los Angeles County or the San Francisco Bay Area.

The hard reality is that people have AIDS, and people are sick. Although at times it’s really tough, all I have to do is move this bike, I can do that. Don’t get me wrong — it hurts, it hurts a lot, but it’s the least I can do in the grand scheme of things to help raise funds and awareness for those affected by HIV and AIDS. Ultimately, this brings more awareness to the other important issues that the LGBT community continues to face.

During this reflection, I realized more than ever just how powerful a diverse and inclusive community can be. My hope is that I can impact others and can foster an environment where everyone feels included and safe to be their true and whole self. I believe we’re on the right path, and I continue to hope we will get there because in the end, love wins.

This year’s AIDS LifeCycle ride will take place June 4-10. Learn more about how you can participate here.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

March 14, 2017

Women’s History Month – Trudy James

AppleMark

AppleMarkI was referred to Trudy James by another Chicago author. It was one of those serendipitous moments. I don’t know how else I would’ve found out about Trudy and the amazing work she has done in the AIDS community. But I guarantee you will learn more about her in my book, Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community:

I was accepted into a one year Pastoral Care internship at the University of Arkansas Medical Center in Little Rock in 1989. A newly-trained chaplain, from Kansas, I knew nothing about AIDS, a fearful, stigmatized disease slowly creeping into the South. I learned fast from the eight AIDS patients I served that year.

At the end of my chaplain internship, after learning that a dear childhood friend in Kansas had died of AIDS and they would not have a funeral in my hometown, I applied for a new half time position in Arkansas as director of RAIN, the Regional AIDS Interfaith Network. It was a four-state experiment funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to see if people in churches could become part of the solution to AIDS hysteria in the South, since some churches were definitely part of the problem.

My assignment was to do AIDS education in religious congregations: any way I could figure out to do it. That included recruiting, training and supporting faith-based volunteers in teams of 6 to 10 members. As CareTeams they were to become supportive friends to one individual or family affected by AIDS—their CarePartners. It was a noble experiment indeed. As a woman who had been shunned and often silenced by my own religious upbringing, (Missouri Synod Lutheran) I identified with AIDS patients who were being shunned, silenced and stigmatized. I could also identify with the people in the pews, having been married to an Episcopal priest for 22 years.

I knew how to tell stories. And I wanted others to be allowed to tell their stories. As I traveled the state of Arkansas, speaking in congregations of all sizes and varieties, (and also Rotary clubs, Dental Associations, Ministerial Associations) I always took a person living with AIDS or a family member with me. They put a face on AIDS in a state where most people did not believe that “AIDS could happen here.”

RAIN was an amazing success. Two years into it, when there were fifteen CareTeams, I wrote a statewide expansion grant proposal to the RWJF Funding Partners Initiative. We received a three-year grant and matched it with local funders.

CareTeam members took Carepartners to the hospital, and to the park; prepared meals, planned parties, and listened to CarePartners review their lives and plan their funerals. In small towns, they took patients to the dentist in the middle of the night, and sat with them as they were dying. The AIDS doctors noticed that their patients who had CareTeams did better and lived longer than their other AIDS patients. We were doing Palliative Care before there was a name for it.

Teams fell in love with their CarePartners; CarePartners fell in love with the teams. The RAIN community gathered quarterly at large interfaith RAINdays, to learn and celebrate together. Isolated individuals from all corners of the state attended the annual four-day Heartsong Retreats. CareTeam volunteers learned to listen to young men and women talk about their own deaths. Everyone learned how to grieve the constant losses so the work could continue.

I was the director of RAIN in Arkansas for ten years. In 1996, 60 of our CarePartners died. By 1997 you could see bumper stickers with our slogan, “Love Makes a Difference in AIDS” throughout the state. There were 127 CareTeams (1500 volunteers) in 40 different Arkansas cities, towns and villages. In ten years the teams had served 500 CarePartners with AIDS.

During those ten years I traveled to ten other states to begin and support the CareTeam model because it seemed so important and powerful to me. I saw miracles happening everywhere. People with AIDS living in small Arkansas towns, or moving home to die from either coast were astounded to be so loved by their CareTeams, and team members felt they were living their beliefs in real ways.

In 1997 I left Arkansas. I still loved visiting CarePartners and recruiting and supporting teams, but I was weary of administration and fund-raising and the ongoing grief. I moved to Seattle because two of my three children lived there. After several months of healing retreat time, I began another AIDS CareTeam program as part of a Seattle Multifaith AIDS Agency. I subsequently trained 70 AIDS CareTeams in the Puget Sound area, worked as a Cancer Care chaplain and began a small business called Heartwork.

When I retired in 2007, I wanted to use what I had learned from those early AIDS days to see if others could become comfortable talking openly about death and planning for a good ending. I initiated a program of four-session, community-based end-of-life planning workshops called “A Gift for Yourself and Your Loved Ones.” After facilitating 50 such workshops, I worked with a filmmaker to produce a film, “Speaking of Dying”, which premiered on April 16, 2015.

Today I travel about screening the film, doing workshops, and training more facilitators. I begin every presentation by sharing what I learned from people with HIV/AIDS and AIDS CareTeams in the South in those early days of the epidemic.

I am grateful.

Trudy James is a graduate of the University of Kansas and Union Theological Seminary in New York City and an interfaith hospital chaplain. She learned hands-on lessons about death, dying and grief in the early days of the AIDS epidemic in the South where her ground-breaking work with AIDS was honored at the Clinton White House. Later, she developed an AIDS Care Team program in Seattle and served as a chaplain at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. After retiring, she spent four years pioneering community-based end-of-life planning workshops and two years producing a 30-minute documentary film based on those groups. The film, Speaking of Dying, is useful for individuals, groups and families who wish to become more comfortable discussing the choices and resources needed to plan for good endings. Learn more here.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

March 7, 2017

Women’s History Month – Kathleen Pooler

Last year for Women’s History Month, I focused on women who will likely turn up in my book, Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community. This year I’m doing the same thing.

Last year for Women’s History Month, I focused on women who will likely turn up in my book, Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community. This year I’m doing the same thing.

First up is my friend, Kathleen Pooler. We met six years ago in an online book marketing class and became fast friends. She shares a common reaction from the early dark days of the epidemic: silence. And the price paid for that silence.

It was 1982. I was sitting at my desk contemplating the unfolding news about a mysterious virus that was creeping its way into our society and taking the lives of its victims. New details emerged every day leaving us in near panic. We knew it was blood-borne and soon we learned of its association with sexually active gay men and those who injected drugs.

As Nursing Administrative Director of the Emergency Department of a 400-bed community hospital, I witnessed first-hand the havoc it wreaked on its victim as we cared for emaciated, gravely-ill patients with multiple skin sores and a new kind of pneumonia, recently identified as Pneumocystis Carinii Pneumonia. I also witnessed the fear among the staff. It all unfolded in slow, agonizing motion as we tried to move forward to provide the best care we could for our patients while protecting ourselves.

The AIDS epidemic began in illness, fear and death. Thankfully, the initiation of anti-retroviral drugs has helped people live longer, healthy lives.

But back then it was shrouded in secrecy and silence which only added to the fear and panic both for the patient and the health care worker.

Back in 1982, I worked side by side with a bright young physician who had been appointed as Medical Director. He had a winning personality, quiet but engaged and skillful. His office was next to mine and as I sat at my desk that day, I wanted to tell him that I knew he was gay and that it didn’t matter. Here’s the thing. I felt the burden of his silence. And since fear was rampant, I could only imagine how the emerging data was affecting him. Everybody knew he was gay but no one talked about it. It was the proverbial elephant in the room.

I enjoyed working with Jeff and trusted his medical judgment. But as the world turned, administrative unrest developed in our department related to factors beyond anyone’s control. Changes at the top level of hospital administration created uncertainty and change for our department. In its wake, rumors circulated.

“Word has it that you and Jeff are having an affair.” My friend and coworker, Christine said, her dark eyes conveying compassion and sadness.

“What?” I asked, completely blindsided.

“And the worst part is that Jeff has not come out to deny it.”

Even back then I remember sensing Jeff’s desperation beyond his denial, but it was still devastating at the time to feel so manipulated and deceived.

Thankfully I moved on to a better job but I’ll never forget the price of silence I experienced during the onset of the AIDS epidemic.

***

A few years later, the epidemic hit home in an even more personal way. My cousin Bob died of AIDS.

“He died of lung cancer, Kathy.” Aunt El, his mom told me over the phone.

Again, I knew he was gay, though neither he nor our family acknowledged it. He was a manager of traveling Broadway shows and he always made sure to contact our family when he would be in our vicinity. I enjoyed Equus, Evita and Ain’t Misbehaving in front row seats. After the shows, he would take me backstage and introduce me to the cast, as if I was the celebrity. I cherish the memory of him dressed in a suit coat, cowboy boots and a brown felt hat, the picture of success and happiness.

A few months before he died in 1984, we were together at a family reunion. I noticed that he didn’t look well. He was pale and a bit disheveled. He had a day-old beard and wore a wrinkled tee shirt that hung unevenly over his jeans. So unlike him.

He asked me if I wanted to take a walk. As we strolled through the Connecticut woods surrounding our aunt’s home, he shared a recent camping trip he had with his father. They never saw eye to eye, I imagine because of his father’s propensity for manly activities like hunting and fishing. He cherished his gun collection. He probably couldn’t understand how his only son could find enjoyment in the theater. But on this trip, Bob and his dad bonded.

“I needed to give it one last shot,” Bob said.

How fortunate I was to share that walk and those precious moments he had with his father. But so much was left unsaid. I wish he could have confided in me how lonely he was. I could have told him I loved him the way he was.

I can only hope that he sensed my love and concern through my silence.

Kathleen Pooler is an author and a retired Family Nurse Practitioner whose memoir, Ever Faithful to His Lead: My Journey Away From Emotional Abuse, published on July 28, 2014 and work-in-progress sequel, The Edge of Hope (working title) are about how the power of hope through her faith in God helped her to transform, heal and transcend life’s obstacles and disappointments: domestic abuse, divorce, single parenting, loving and letting go of an alcoholic son, cancer and heart failure to live a life of joy and contentment. She believes that hope matters and that we are all strengthened and enlightened when we share our stories.

She blogs weekly at her Memoir Writer’s Journey blog.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

February 28, 2017

How Authors Are Rewarded

Last Saturday I was part of “Path to Published”, a panel discussion put together by Chicago Writers Association. I think I can say that all of us on the panel had a great time talking about our various experiences: self-publishing, traditional and hybrid publishing.

Last Saturday I was part of “Path to Published”, a panel discussion put together by Chicago Writers Association. I think I can say that all of us on the panel had a great time talking about our various experiences: self-publishing, traditional and hybrid publishing.

One of the questions has really stuck with me since then. It was one that’s fairly common, one that everyone is asked eventually:

“What’s the most rewarding thing about being a writer?”

There are the obvious things: lots of people buying your books, great reviews, awards, crowds at your book signings. But that’s not what I talked about. My answer was in two parts.

With my Friend Grief series, I knew I had a hard sell. Grief is not a real exciting topic. Whenever someone would ask what I write about, I would tell them that my books were about people grieving the death of a friend.

“That’s depressing.”

Yeah, that was the first comment I heard from most people. I assured them it wasn’t depressing: the books are (I hope) powerful testaments to the deep friendships that enrich our lives and the ways people find to honor their friends. The person making that comment would pause; maybe tap the cover of one of the books. And then they’d say, “You know…” Then they’d tell me a story about a friend of theirs who died. That’s when I knew I had them, that they understood my books.

The most rewarding part of my next book (Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community) is a little different.

In September 2015, I finally committed to writing this book, after spending over a year trying to talk myself out of it. So one night I announced it on my personal page, my author page and in various AIDS-related groups I belong to on Facebook.

Within five minutes my phone was chiming with private messages and texts:

“You need to interview X. Here’s her email. Tell her I recommended her.”

“I wrote a book that has some information you can use.”

“There’s an organization in Philadelphia/San Francisco/Baltimore/Texas that you should contact.”

Some were friends; others I only knew on Facebook. Many were strangers, members of the groups I belong to. But they all had one thing in common, besides liking the idea: they trusted me to tell these stories.

I didn’t realize at the time how rewarding that would feel, but frankly, it keeps me going. There are strangers out there – in the US, UK, Canada and Europe – who believe that I can do justice to the women whose contributions to the AIDS community have never been celebrated.

I guess the difference between the two experiences is that with the first one, it’s rewarding to me that they understand what I do. With the second one, their trust in me is not just rewarding, it’s humbling.

There are times when I feel like no one cares about what I write. Other writers feel the same way. But the reward comes when someone says, “You have to do this. It’s so important.”

What can be more rewarding than the realization that someone believes in you?

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

February 22, 2017

AIDS and Women’s History Month

ohio.edu

ohio.eduIt’s no secret that I’m writing another book. What began as a nagging thought turned into an idea that has taken on a life of its own. Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community overwhelms me occasionally – if you define ‘occasionally’ as ‘at least once a day’.

I’ve always felt these were stories that needed to be told: how straight women around the world have been an important part of the AIDS community since the beginning of the epidemic. But a random comment from a colleague a few weeks ago opened my eyes to something much bigger.

I was telling her about the book and she said “It’s like Hidden Figures.” I wasn’t sure how to respond. I loved the movie about the African-American mathematicians who helped build NASA in the 1960’s, whose stories are only now being told because women were erased from official histories of the space program. I could never compare my book to that.

Like many things, including the idea for the book, it was an idea that I couldn’t get out of my head. I’d been thinking in terms of the AIDS community, but now it seemed the book might have a wider audience.

So while I was working on the book proposal, I decided to check some books on late 20th century women’s history (that sounds so long ago, doesn’t it?). I started with one that was described as “definitive”. Almost 300 pages long, it included one paragraph about AIDS. What it described was an important moment for women: the official definition of AIDS did not include the unique ways the virus presents itself in women. Because of that, women were not properly diagnosed or treated and were denied disability benefits.

But the paragraph failed to mention how that changed and who did the hard work: the women of ACT UP. It took several years, but the definition of AIDS was finally changed. No one reading that paragraph would know who deserved the credit.

That’s when I realized that my book is about a movement in women’s history that has been ignored.

I found myself grateful for my broken hand, the one that put me a full two months behind on the book. That enforced break from my work also meant that my proposal is late going out to the agents who requested it. Now the marketing section is very different than it was a few weeks ago. But I realized I was already on the right path.

Last March for Women’s History Month I turned over my blog to four straight women in the AIDS community: Nancy Duncan, Eileen Dreyer, Andrea Johnson and Rosa E. Martinez-Colon. Their stories are all different, but they share one passion: to support those who carry the virus and work to end the epidemic.

This year you’ll hear from a different group of women. The stories are as unique and inspiring as the women themselves. I can’t wait to share them with you.

I wish my book could honor all the women I’m researching and interviewing, but it can’t. Each woman who makes it into the book will be representative of hundreds of others. But I have a few ideas on how to recognize these women beyond the book itself.

Yes, definitely overwhelmed. But not discouraged. Never discouraged.

Back to work.

Don’t miss these Women’s History Month posts and news about the book! Sign up for my newsletter in the upper right hand corner of this page.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

February 15, 2017

Delayed Grief on Facebook

how-to-geek

how-to-geekA friend found out recently that an old friend of hers died…a year ago. They’d lost touch, as friends often do. But when she saw a post noting the first anniversary of this man’s passing, she was not prepared.

Sometimes people cannot grieve a friend’s death immediately. Soldiers in combat can’t take the time to grieve in the midst of battle. They have to push their grief aside. Anytime grief is delayed, there’s a chance that it will pop up when least expected.

One of the men I interviewed for Friend Grief and Men: Defying Stereotypes was frustrated when the widow of his best friend did not hold a memorial service for almost nine months. He felt adrift, unable to process his grief without a public ceremony.

Like them, the friend who saw this news on Facebook has nowhere to go with her grief. The funeral was long ago, so that opportunity is gone. Should she contact the family? Would it cause them unnecessary pain?

It’s easy to lose touch with friends. And while high school reunions can be fun, they also include news of friends who died. My class meets every five years, and more often than not there have been names to add to the list of those we remember during mass.

Through the ‘80s and early ‘90s, at the height of the AIDS epidemic, it was not uncommon to learn of a friend’s death weeks or months later. I found out one college classmate was dead when I saw his panel on the cover of a book about the AIDS quilt. I hadn’t seen him for over a decade, and he’d been dead for several years, but it was still a shock.

Whenever I found out this kind of news, the shock was always followed by confusion: what do I do now?

I’ve struggled with that sometimes, and I’m sure my Facebook friend is struggling, too. So this is what I would say to her:

Do whatever you want. Take the time to grieve. Talk about your friend, ideally with someone who also knew him.

What I hope she doesn’t do – and what I hope you don’t do if you find yourself in a similar situation – is to brush it aside. Grief is grief, whether you watch someone die or learn the news years later. It’s not less important because your friend has been dead for months.

Facebook has been a blessing in many ways. I’ve re-connected with long-lost friends; I’ve kept up with their news. I’ve learned of their illnesses and recoveries, their accomplishments and challenges. Sometimes the news isn’t good: two of my Facebook – and real life – friends do not expect to live to see 2018.

Even though the news is sometimes shocking, sometimes unexpected and unwanted, I’m grateful to have a lot of ways – phone, mail, texting, tweets, posts – to keep in contact with my friends. I’m going to seek out a few more I’ve lost contact with. Because life is much too short.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

February 1, 2017

How Can You Write at a Time Like This?

A lot of writers I know have been struggling these past few months. Their fears about the future are on display, in their online posts and in their writing. Anxiety is rampant. So is insomnia. The news of the past two weeks has only heightened their concerns.

A lot of writers I know have been struggling these past few months. Their fears about the future are on display, in their online posts and in their writing. Anxiety is rampant. So is insomnia. The news of the past two weeks has only heightened their concerns.

They are a diverse group: men and women, all the major religions, every race and generation. They live in the US and other countries. They write fiction and nonfiction, memoir and science fiction/fantasy, poetry and children’s literature.

And every one of them seems to be asking themselves the same question: How can you write at a time like this?

Writing almost seems superfluous, a luxury we can’t afford. We have to keep our eye on the news 24/7, to react and respond. For God’s sake, how can romance novels be important when 1984 is #1 on Amazon?

Oddly enough, I haven’t felt that way. Maybe it’s because I feel so driven these days. What’s going on in the world has not discouraged me from working on this book. If anything, it’s given me the encouragement I need to keep going.

A few writers I know are similarly focused. After all, people are still buying books, still reading books. And while most of the people who are reading 1984 right now probably hadn’t read it since high school – if then – they’re reading it for a reason.

To make sense of the world.

Now, how we do that varies. Some people seek out history books, to help them understand how the world has dealt with crisis situations in the past. Others seek out pure escapism, to simply close the door on what is so deeply overwhelming and disturbing.

It’s not surprising that people would choose books that are very different than what they read a few months ago. But they haven’t stopped reading, haven’t stopped looking for answers and/or solace. That’s why writers must keep writing: to give their readers what they need.

My reading has been, and continues to be, research-driven, focusing mostly on the first fifteen years of the AIDS epidemic (1981-1996). It was as dark a time as I ever remember: fear, panic and hatred, all directed towards people who were dying the most horrific deaths any writer could imagine. One would think that would make me feel worse, given that many of those who survived those years are now at risk again.

But I find my research leaves me incredibly optimistic. I remember all the things – and people – who made that time a nightmare. But it got better. It took a long time and not everyone survived, but it got better. And that gives me hope.

It got better because of the men and women who didn’t give up: the researchers and activists and caregivers and others who gave their all. That’s what will get us through these times, as well: the men and women who don’t give up.

That includes writers. Writing – like parenting – leaves us wondering if what we’re doing makes a difference. Too often, we have no idea. But now and then, like a kid who gives you a spontaneous hug, a reader lets us know what our writing meant to them. And that makes it all worthwhile.

So, my writing friends, keep at it. Take a break, have a glass of wine, get out in the sun (if you’re lucky enough to have any), order dessert. Get some sleep. Revive your spirits. There are readers out there who need to hear what you have to say.

Giving people what they need in these uncertain times may turn out to be the most radical activism of all.

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post

January 24, 2017

Who Tells Your Story?

mnu.edu

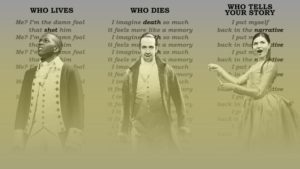

mnu.edu“Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” – Hamilton: An American Musical

The best movie I’ve seen in a long time is Hidden Figures, the story of the African-American female mathematicians who helped NASA put men in space. I’m old enough to remember the Mercury astronauts and when a space launch was reason to gather your family around the TV. Everyone we ever saw in the NASA control rooms was a white man. So when the movie – and book by Margot Lee Shetterly – were released, the most common reaction was “I never knew that.” The second most common reaction was “Why haven’t we heard this story before?”

Hidden Figures is not the first book or film to tell a little known story. Sometimes it’s the telling of a story for the first time (The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks). Sometimes it’s the story of a person who’s always been in the background (Hamilton: An American Musical). Why are we just now hearing about them decades or even centuries after the fact?

There have been a number of documentaries and books released in the past few years that address the AIDS epidemic. David France recently released his remarkable book based on the 2012 documentary, How to Survive a Plague. Tim Murphy’s novel Christodora is receiving much deserved praise. Two deeply emotional documentaries – Cecilia Aldorando’s Memories of a Penitent Heart and X’s Last Men Standing – came out last year. All are exhaustively researched, impeccably presented, critically acclaimed.

But why are they – and my next book, Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community – necessary? Do we really need all these books and films about the same thing?

I wondered the same thing when I was wavering on committing to this book. We’ve come to a point, in the fourth decade of the epidemic, when more memoirs and documentaries are focusing on the AIDS community. Some address the issues facing long-term survivors; others remind us of the obstacles we faced in those dark early days. But each and every one told a familiar story from a different angle. Each introduced us to people and events that were previously forgotten, or known only to a few. Each challenged you to look at the epidemic with fresh eyes.

That’s what I hope my book will do. It’s a huge responsibility, no doubt about it, to honor the contributions of straight women largely ignored in the above examples. There are so many stories that need to be told, like the origin of “Women Don’t Get AIDS, They Just Die From It”. Or what happened when Elizabeth Taylor testified before Congress. Or why Ruth Coker Burks is called the “cemetery angel”.

The point I’m trying to make is not about my book, or the AIDS community. It’s about stories.

If all we ever hear is one version of a story, no matter how broad, it’s going to miss someone. Sometimes that omission is deliberate, to suppress voices that threaten the official version and don’t further its agenda. And sometimes the omission is of something or someone that was simply deemed unimportant.

That’s when the Rebecca Skloots and Margot Lee Shetterlys of the world step up, uncovering the story of Henrietta Lacks and the injustice that was largely unknown even to her own family; revealing the unrecognized twin barriers of racism and sexism within NASA at a time when the country was united behind the space race.

I’m not comparing myself to them. All I’m saying is don’t assume that any story – no matter how sweeping – is the only one. Sometimes the people involved can tell the stories. Sometimes it takes a stranger, stumbling on a tidbit of information that surprises and intrigues them.

And if you don’t tell them, who will?

#short_code_si_icon img

{width:25px;

}

.scid-2 img

{

width:25px !important;

}

Share this post