David Macinnis Gill's Blog: Thunderchikin Reads, page 9

September 21, 2016

Mist

Shall we gather at the river?

Shall we gather stones

To place on the graves

Of those we’ve lost?

Shall I open myself

Like a spigot turns

A fountain flowing

Deep and wide?

Or shall we walk

Hand in hand, speaking

To the voices that whisper

From the mist?

September 19, 2016

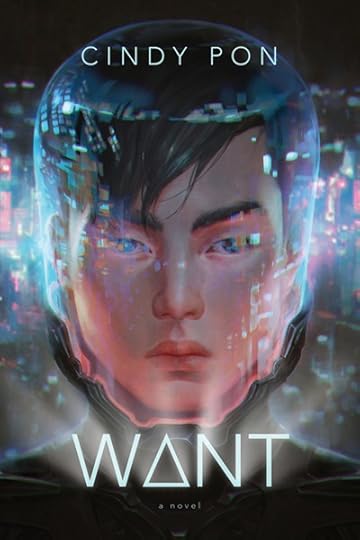

Diversity in YA — WANT Cover Reveal

Cindy Pon and I have been friends since we were both signed by Greenwillow, one after the other, only months apart. This is the cover reveal of her latest novel, WANT, coming soon form Simon Pulse. Read the whole post at http://diversityinya.tumblr.com/post/...

Every book I have written is a book of my heart, but WANT is especially dear to me. A near-future thriller set in Taipei, it is an ode to my birth city, the vibrancy of which is deeply rooted in me. The feel of the air, the smells, these colors shaped my childhood and who I am today. I tried to capture that in WANT. This book is also special because it is the first non-fantasy novel I have ever written and challenged me in so many ways as a writer. But I loved my characters in this book, especially my hero and heroine, and I loved portraying this city I adore, a character in itself, so close to my heart. It is the first YA speculative fiction I’m aware of published by a big US publisher set in Taipei, if not the first young adult set there. So many fantastic firsts!

The WANT cover is stunning and amazing and everything I could have hoped for as an author. I hope you love it too!

Jason Zhou survives in a divided society where the elite use their wealth to buy longer lives. The rich wear special suits, protecting them from the pollution and viruses that plague the city, while those without suffer illness and early deaths. Frustrated by his city’s corruption and still grieving the loss of his mother who died as a result of it, Zhou is determined to change things, no matter the cost.

With the help of his friends, Zhou infiltrates the lives of the wealthy in hopes of destroying the international Jin Corporation from within. Jin Corp not only manufactures the special suits the rich rely on, but they may also be manufacturing the pollution that makes them necessary.

Yet the deeper Zhou delves into this new world of excess and wealth, the more muddled his plans become. And against his better judgment, Zhou finds himself falling for Daiyu, the daughter of Jin Corp’s CEO. Can Zhou save his city without compromising who he is, or destroying his own heart?

September 18, 2016

Hank Williams on the Radio

The nicotine coating your truck windows so thick

it took us vinegar and old paint canvas

to cut through it.

The snap of your Zippo lighter

like the snap of a worn leather belt

when you let me fill it with fluid.

The ember of your Pall Mall

dancing in the night

when you told Uncle Joe that

jacks bounced

hippity-hop, hippity-hop

in the south Georgia sand

and you had to get them

on the hip or else

they’d be gone.

The rabbit’s foot you rubbed each time

the lotto numbers came out,

the one’s a dark-haired angel had whispered

in your ear, just above

the morphine patch.

The clickity-click, clickity-click

of the breathing machine

and the tube of oxygen that your fingers

fluttered to your face to hold in place

when your lungs were coated so thick

no vinegar could cut through it.

The ease of lifting you from toilet to bed,

your body but sinew and bone,

the husk that had once been my father.

Your wink after the eleventh-hour taking

of Jesus Christ as your personal savior,

cause it never hurt to hedge your bets.

Other things about you I have forgotten.

But those, those

I remember.

Gotta get ’em on the hip,

Or else they’ll be gone.

To the Long Islander Waxing Poetic about a Fast Food Chicken Leg

Southerners take comfort

Not in a liquor bottle filled with escape

But in food that brings them back home.

Collards and turnip greens and mustard greens, too.

Fried taters and mashed and smothered with

With sawmill gravy or red-eye if you’re brave.

Okra, cream corn, tomatoes fried green

Sliced onions, pickles and four types of peas.

Pole beans, green beans, pinto beans,

And butter beans big as your thumb.

When necessity makes the Colonel

The modern version of a yesterday meal,

I hanker for a plate filled with real food

Not approximated potatoes and a

Ten-pound chicken bucket

Filled with breaded regret.

Give me hamhocks and pork chops and

Fried chicken, filling long tables of

Sunday Dinner after church, with

No Yankees allowed.

September 16, 2016

Gossamer Steel

Calla heard the train before she saw its light cut through the fog. The air horn blasted as the engine wound over the ribbon of track, at first unhurried and small then growing until it blew by the small people in the Nashville station. Calla clutched her baby and the steamer trunk that held the contents of her life.

“It’s about time,” she told her baby. “The North Carolina and St. Louis ain’t got nothing on Southern. Southern’s more punctual than God.”

The air brakes cried. Sparks lit the air, and the wheel trucks clattered and groaned. The wind stirred up by the train whipped against the passengers’ faces and scattered fog across the platform where Calla waited. Lamps over her head burned to meet the morning and Calla yearned to feel their heat on her small hands.

Calla watched the conductor step down the from the vestibule. He set out a box for passengers to step up on. In the brittle December, the train pulsed dense exhaust onto the platform and Calla was lost in the fog, afraid to move because she might be run over by the Red Cap porters who darted around her, seeming to know every inch of the planked platform.

Is it this cold all the time out west, she thought. She fingered the telegram that she folded neatly and put in her pocket for safekeeping. The edges were tattered from worry and she thought about her husband’s command that her and his baby join him in Washington. He would meet her train in Tacoma, it said, and she knew she’d catch Hell if she wasn’t on time. He’d wired enough money for a bus from Monteagle mountain to Nashville and for a train to Chicago, then Tacoma. She had hidden the change in her shoe, just enough leftover to pay for her dinners but not much else.

Is he going to keep his promises about the drinking, she thought, or will he just turn meaner without Mama to watch out for me?

In a moment, the fog cleared, but the cold remained crisp and bright. Calla’s wool coat barely deflected the wind, and the baby cried, his cheeks red and burned. When he nuzzled Calla’s warm neck, she pushed down her chin to hold off the cold nose, and pushed the baby’s face into the blue coat where it could rub against the fabric and be still.

“Boarding!” the call came down the line. “Have all luggage checked.”

It’s about time, she thought, I’m about to freeze to death.

Calla stamped on the boards to get warm, a trick she’d learned growing up in a house with only a pot-bellied stove for heat. Through her sneakers she felt an icy snap from her arches to her knees and she wanted the fog back, so that the diesel exhaust could warm her legs and lick her thighs and fill her dress to the waist, where she never seemed to be warm enough.

“Boarding!” the call came again.

Red Caps wove through them, dollies in hand, wheeling baggage onto the train. The other passengers, dressed smartly in knee-length overcoats and warm hats, lined up to board the Pullman. A conductor held his hand out to the ladies, who smiled at him and whose husbands nodded their approval, and the same conductor, his uniform as bulky and black as the car, held the door for each and every one of them.

When she was last, and when the other bags had been loaded in the baggage cars and the other people had been escorted to the Pullman, Calla waited for them to load her trunk, feeling like a blue speck against the bulk of the train.

“This ain’t right,” she said to one porter. “Me and this baby paid to ride this train, too, just like them rich folks.”

But the Red Caps, who danced around her as if she were a loose plank in the platform, had disappeared.

“Last call for boarding!”

“Don’t y’all leave me here. My husband will beat the tar out of me if I miss this train.”

She pulled the steamer trunk along by the cracked leather handle until it broke, then kicked the trunk, pushed and cussed it across the planks, tearing off bits of the platform with its loose rivets.

“You need a hand with that?” the conductor said from the vestibule.

“Well, yes, I need help,” she said. “This thing’s heavier than I am.”

“Bo!” His voice was deep like the sound of churning wheel pistons. “Come get this here trunk for this pretty little girl.”

With a rush of exhaust the platform filled with mist and fog, and Calla stood still to let the warmth massage her knees and thighs and panties. A ghost from the fog, the Red Cap materialized, his skin shiny black against his muted white uniform. He scraped up the trunk then dissolved into the steam.

“You and your baby follow Bo. He’ll get you fixed right up.” the conductor said.

“Follow him? I can’t even see him. Besides, I got me a ticket for this Pullman car, and I intend to get on it.”

“And I’m President Eisenhower.” He stuck out his hand. “Ticket.”

Calla fished in her coat pocket, finding a sewing kit, a spare dime for a drink when she got to Chicago, and the telegram. “Must be in my other pocket. Here, hold the baby.”

Calla started to hand the baby up to him, but she yanked him back before he could lay a finger on it. Don’t let go of that baby, her husband had written in the wire and she knew better than to defy John Mark. She shifted the baby to her other shoulder where it grunted and nuzzled against her neck and she reflexively pushed its cold face away with her chin.

“Oh God,” she whispered, “please let it be there. He’ll hurt me bad this time.” She pulled out the boarding pass, also neatly folded. “Here it is.”

“Thank you, miss.” The conductor pulled open the door.”That’s missus.”

Calla snatched her stub and stepped into the car. She nudged her way down the aisle and hiked the baby up to her shoulder. For a nine month old, he slept heavy, like a red-faced rock she had to carry from one place to another. Maybe it hadn’t been such a good idea to add a thimbleful of whiskey to his water. She had problems enough as it was.

It felt hot inside and she was instantly uncomfortable. The door latched behind her and she leaned against it while an old man and a young occupied the aisle putting valises and hat boxes into the overhead compartments. The old man, dressed in a black suit, slammed a compartment door as Calla passed. The baby snapped up his head and cried.

“Be still,” Calla said. “Hush.”

The young man smiled as she passed him. “How do?” His dark suit with thin lapels was nothing like the mechanic’s coveralls her husband always wore, and the man smiled like it was natural for him, not something he had to force himself to do. She ducked her head and slipped to the back of the car. She looked up at the overheads and wished in her meanest mind that she could put the baby in one of those compartments and not be bothered during the trip, but she hated herself for thinking about it and put it out of her mind.

Out of the deep pockets in the lining of her coat, she took one of six bottles of water. She tucked it under her free arm to warm it. She whispered to the baby, “that’s colder than a witch’s tit. See what I have to put up with for you.” But the baby slept and sucked on the coat.

When she looked around, the smiling man was stuffing a duffel bag into an overhead. He sat two rows up facing the back of the car and caught her eye then winked, and she blushed at having been caught looking. The man opened his coat, stuffed his fingertips into his waistband, and closed his eyes.

John Mark puts his hands in the exact same place, she thought. But when this man did it, he wasn’t so ill-mannered. Though her husband wasn’t exactly crude, he had his own ideas about the way things were done and not done. A person couldn’t tell that about him because he was so reserved that he seldom spoke, often going a full day without saying anything to anybody.

Calla watched the man sleep. “That’s one good-looking boy,” she whispered to the baby. Then no, she decided, he just looked nothing like her husband. But looks weren’t everything in a man. Sometimes a girl had to be practical if she was ever going to get anywhere. How many times since she’d married John Mark had she told her mama, love and good looks ain’t what concerns me in a man. And many how times had her mama answered, that’s good, because love ain’t got nothing to do with John Mark Hawkersmith, and if he had his druthers, he ain’t got nothing to do with love.

She wished now that she had sat closer to the man to maybe have somebody to talk to. Her husband wouldn’t know any better, so he couldn’t throw a fit like he did sometimes when men spoke to her. “I suppose I could just move,” she said, but the baby weighed a ton now and she wasn’t the kind to be hopping from seat to seat, place to place. Once she sat somewhere, she rested.

The train jerked. Slowly at first, almost as if it, instead of the train, were moving, the Nashville station seeped by the window. Within seconds, the city seemed far away and unreal, like the crayon pictures she had drawn in school, using bits and pieces of colors. The picture in the window became scribbled like the lid of a cigar box: just scraps like crayons on a hot sidewalk in summer melted into a liquid of color and sound so that only the distant rolling foothills of the mountain remained. And before she turned back to the car, the horizon had gone–not melted, just gone–and the world she’d known was flat and without color.

The sleeping man opened one eye then the other. As he passed her on the way to the john, Calla noticed his hair was cropped short in the back but covered his forehead in front where it was parted down the middle. John Mark kept his hair clipper-cut and slicked down with Vitalis, a style left-over from his Army days. Calla’s brother had brought John Mark home to the mountain after Korea. She didn’t like him at first because he didn’t talk enough and when he did, he gave orders, plus he was too old for her. But after awhile she warmed up to him. He wasn’t a mountain boy and she had thought this hard man could be her ticket to something better, and if not that, at least something else.

Now she ached for a smoke, just one, the menthol fog that soothed her nerves and filled her lungs with warmth. But with the other baby on the way, she didn’t think she should trade food money for cigarettes since she was eating for two and feeding another. She hadn’t been smoking that long. John Mark taught her how to smoke when they were dating and he’d shared his once after they’d made love. To Calla, the smoke was more satisfying than the sex. Then she thought of the night before he’d left town, when he’d come home drunk again and forced her legs open because she was too sleepy to say yes.

Wonder what you’ll say, she thought and patted her still-flat stomach, when I tell you about this present you left me with.

The baby cried to be fed. Calla stood, then sat, the side-to-side rocking of the Pullman throwing her off. She stood again and by bracing with her free hand, turned to the john behind her as the smiling man was opening the door. He bumped into them then caught Calla around the waist to keep her from falling.

“Excuse me,” he said. “I’m sorry. Are you hurt?”

“No, I’m fine. You can let go of me now.”

“Of course.”

As he tried to slide by her, the train rocked and he rubbed against the back of her skirt. He caught the headrest of a seat and pulled himself into his row. Calla smoothed her skirt and grabbed for the closing door. Inside, she expected a ladies room like the ones in the movies–velour chairs, a vanity mirror, and lighting that made the skin milky white and rich red in the right places, or an attendant, maybe, who helped the ladies freshen up and passed out hand towels and thin mints. Instead, she found a sparse metal toilet and a box of a sink with no mirror.

A towel borrowed from the rack made a good burp rag. She unbuttoned her blouse to expose her small breast and hard nipple that the baby clamped between its gums. “Good baby,” she whispered. Her breasts always itched at feeding. Alone at home, she would have kneaded her breasts, twisting them in her fingers until the nipples turned buttery. Sometimes she felt something between her legs like the rocking of the Pullman car.

“Might as well kill two birds,” she said and sighed. She wiped the toilet seat with paper. “Woo. I feel sorry for them well-diggers.” Goose bumps danced down her legs when she peed.

The baby finished and she put him on her shoulder. Her breast was still uncovered and the nipple hardened with the cold. She thought of the man and cupped her breast, pinching the brown nipple and rolling it between her fingers. Her breathing became rhythmic and she squeezed the baby tight against her.

“Tickets!” the call came through the door. “Tickets, please sir!”

Lights seemed to dance in front of her. “Oh God, what am I doing?” She pulled up her panties with one hand by twisting her hips side-to-side and buttoned her blouse. The baby burped as she slipped through the door and into her seat.

Another conductor worked his way down the car. From her pocket, Calla took the ticket stub.

“Ticket, please.”

Even as she handed the ticket over, Calla knew from the way the man cocked his head, he was looking down on her, judging her ratty blue coat, faded red tennis shoes and the new bobby socks with yellow piping that were folded over with crisp edges.

“How did you get a first-class ticket?”

She choked off words that tasted like fuel. She looked up at the square, rigid face. “I bought it.”

“With what money?”

“Mine. What’re you saying, I stole it?”

“Ain’t said nothing. Not yet. How old’re you, girl?”

Calla watched the overhead lights dance in the gold threads on his cuff. “Old enough.”

“Speak up. If you’re a minor traveling alone, I got to know that.”

“I’m nineteen.”

“Littlest nineteen I ever laid eyes on.”He pinched the ticket stub. “Where’s your husband?”

“I’m going to meet my husband in Tacoma. Him and my brother found work there.” John Mark’s promises clattered through her head, Things’ll be better in Washington, a man can find work there, a good job. Maybe we can get that house you been wanting. Maybe a washer-dryer.

“What’s Tacoma like?” the blue man said.

“Don’t know. Ain’t been there.” She thought, It can’t be no worse than home.” How many times in the last month had she heard her mama say, You making a big mistake, going off to that man. How many times had she told her mama that John Mark was her ticket off the mountain and her mama would say, but what price you got to pay for that ticket?

As the conductor examined the ticket, the smiling man came over to them. “Is there some problem here?”

“Nothing we can’t handle, sir.”

“I don’t mean to butt in, but I couldn’t help overhearing. I can vouch for this pretty lady. I myself saw her buy that ticket in Nashville. The ticket agent wasn’t nice to her, either.”

Calla wanted to stick her tongue out at the railroad man. They were all a bunch of bastards.

“I ain’t meaning to harass nobody. I just got rules I have to follow.” His face was as stern as John Mark’s. “You and the baby be careful. Chicago is a big city.” He moved on. “Tickets, please sir.”

“Thank you,” Calla said.

The man nodded, “No problem.”

She wanted to say more, but he turned away before she could think of anything. With his fingertips in his waistband and his feet up on the facing seat, he closed his eyes. Calla noticed how long his eyelashes were and how clean the soles of the shoes seemed. She liked a man who took care of himself and his shoes, instead of tracking mud everywhere and letting the boots go to Hell.

The train settled into a rhythm, gliding sing-song on the twin threads of gossamer steel rails. Calla warmed another bottle of water under her arm and tried to stay awake, but she fell asleep. The baby nuzzled warm into Calla’s neck. They slept together for awhile until the baby woke her up crying.

“Hush now. Shhh.”

She rocked in the seat, panicked to keep him quiet. She knew a crying baby was the sign of a weak mama. As the baby and the train rocked in unison, Calla noticed the man watching her. He whistled until the baby finished crying. Stealing glances, she noticed the man had dark skin and black hair that seemed tossed onto his head. Her husband’s hair was already thinning. She remembered the feel of the crow’s feet on John Mark’s squinted eyes and then the down-turned corners of his brittle smile that didn’t dance like the white scar on the young man’s cheek bone. His eyes were smooth and only crinkled when he smiled.

“That your baby?” After finishing his last tune, he stood, caught his balance, then swung into the seat beside her. “Is this seat taken?”

“Yes.”

“You mean it’s taken?”

“No, I mean it’s my baby. The seat ain’t.”

“Pretty baby.”

“Thanky.”

“Pretty as its mother.”

“Hush up with that. I ain’t pretty and you know it.”

“Pretty as a picture, so don’t try to be modest. You traveling alone?”

“You’re awful nosy, mister.” She put the baby on her shoulder and pounded some burps out of it.

“Just making polite conversation.” He hummed again, then stopped. “Any harm in that?”

“Ain’t selling nothing, are you?”

He laughed. “I’m a Navy man. What do I have to sell?”

“Navy, huh? You don’t look like you been in the Navy.”

“Just mustered out.”

She whispered. “You got a tattoo?”

He cupped a hand beside his mouth. “Seven of them.”

“Seven? Naw.”

“Naw. You crack me up.”

“You ain’t got seven tattoos.”

“Have.”

“Prove it.”

“Can’t.”

“Why not? You a liar?”

“Nope. Just can’t show them to you.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t know you that well.” His eyes whistled an exotic tune at her.

Fingering the wisps of the baby’s hair, she turned her head away from the man, suddenly sorry the conductor had interrupted her in the bathroom. Calla patted the baby’s diaper and kept watch on the window.

“Care for a nip?”

“Huh?”

“Warm you up a bit. Cures what ails you.”

“I don’t drink. I’m a Baptist.”

“Isn’t everyone down here? Here’s a joke for you, why don’t Baptists have sex? It looks too much like dancing.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“It’s a joke, you know Baptists don’t dance.”

“I used to dance.”

He took a sip from his muted silver flask. “Good stuff.” He patted his breast pocket. “You smoke?”

“No,” she said, though she craved a cigarette and wondered how satisfying one would be right now.

“Boy, you don’t smoke and you don’t drink. No vices at all. At least you can’t lie about being a virgin.”

“I can’t believe you said that.”

“You got a husband?”

She fanned her left hand to display the white gold ring. “Yes, nosy, I do.”

“Where is he then?” He tapped a fresh pack of Chesterfield’s against the back of his hand, unzipped the cellophane and slid off the wrapper. Gently, he withdrew a cigarette, reinserted it and withdrew another. Cupping his hands around the lighter, he massaged the roller. The flame, set barely above the wick, lit the tip of the cigarette. He drew smoke deep into his lungs, blew rings that drifted level with his head before they were stripped of their shape by the humid draft.

She watched the phantom rings float away. She yearned to cup the rings in her hands, to fold them neatly, crease the edges and stick them in her pocket along with the wire. “Tacoma. He’s been in Tacoma looking for work.”

“I’ve been to Tacoma, Seattle too.”

“What’s it like? Bet you it snows a bunch up there.”

“Been all across the country. Mexico, France, Philippines, Cuba, too. Strange and wonderful world we have here.”

“You don’t say. France. What’s France like?”

“Cuba’s like a woman.”

“You’re strange. I didn’t ask you about Cuba.”

“Sure you’re not wanting a cigarette?”

Her hand almost trembling, she plucked one from the pack. “You tempted me into it.”

“The only way to resist temptation is to consent to it, that’s what I always say.”

The smoke sifted from her lungs into her body, settling her hands and her nerves. Funny how fast a cigarette did its business. She tasted the menthol and ran her tongue around the edge of her teeth and even blew a small smoke ring. Things seemed much clearer now. Her heart stopped beating so fast. “So, where you headed?”

“Home.”

“Where’s that?”

“Chicago.”

“Anybody ever tell you that you look like somebody famous?”

“Never.”

“You don’t, now that I think about it.”

He started whistling again, a deep, dirge-like tune. “You like opera?”

“Don’t know. Ain’t heard none. I like rock and roll myself and my husband, he’s big on country and western.”

“I’m not much for western, though there’s something about country girls I really like.”

He brightened and hummed. For miles, he watched the window, a music stand that held the notes to his score. Calla shifted the baby to the other shoulder after covering her coat with the soaked hand towel.

“When we get to Chicago,” he said, still watching the window. “How about I show you the sights.”

“You mean going drinking?”

“Nope. You’re underage. Besides, I meant sight seeing or dancing, that kind of thing.”

“If you was to buy a girl a present, what would it be?”

“Something that would match her beauty.”

“Wouldn’t be no washer-dryer, would it?”

“What kind of present is that?”

“You said you wanted to go dancing? That’d be fine. I’d like that.”

He leaned toward her. His scar jitterbugged in the light. “Your husband won’t mind?”

She laid the baby down on the seat beside her and covered him with his blanket. Without the child’s weight, her shoulder felt like it was rising. Calla took a drag of the cigarette and blew smoke into the sultry cabin air. “My husband won’t know.”

They made their plans and he told her about his family’s home in Oak Park and about the lake and the jazz clubs downtown where they played music better, faster and with more guts than anywhere else on earth. For hours he talked and she listened and the memory of the mountain and John Mark faded with each passing mile. In time, she fell asleep with him still talking.

Then the baby woke crying, red-faced and gasping for air. Calla snatched him into her arms. His jagged cry rang through the car as if he were a train coming to a crossroads, blasting its air horn at passers-by. The other passengers watched Calla and the baby, and they began to whisper to one another. Calla tried a bottle, but the baby bit the nipple and cried despite it. Her attention darted down the aisles to the faces of the others until she rested on the dark man. In his eyes, she found no waltz, no slow dance, no help. She moved the baby to the sticky warmth of her neck. Calla felt the little cold nose and the soft cold lips against her skin. She hummed and rocked and pressed her head against her son’s cheek and warmed that too.

The train stopped in the Chicago depot. Calla closed her eyes. In the darkness, she felt herself still moving, still traveling, still fluid. When she opened her eyes again, the man had stood.

“Got to get my stuff,” he said. “Be back in a minute.”

Calla nodded. The man slipped ahead of the other passengers to get his duffel bag. He pulled on an overcoat while Calla gathered up the baby and their things.

“My train to Tacoma leaves in half an hour,” she said.

“Backing out on me? I thought we had plans.”

“I just….”

“Come on. Let’s get some coffee and we’ll talk. Stick close to me, though. Guys in this station get a load of you, I’ll have to beat them off with a stick.”

As they left the train, she stepped onto a concrete slab landing. A wrought iron rail separated the platform from the rest of the station. Calla held the baby high when they stepped through the turnstile and up the four steps to the main floor. The baby opened its eyes to the cold swirl of passengers leaving the platform.

A Red Cap whirled by her. “This you trunk.” He flicked the trunk off the dolly and wheeled into the crowd before Calla could stop him.

“Lord help me.” She tried to jerk the trunk along with her free hand. “Why didn’t they just put it on my next train.”

The man smiled. “I had them get it. Let me give you a hand.” He hefted it up by the good handle. “You don’t pack light, do you?”

The wind swept around her, moved her away from the cars and the noise of the train. The current of people carried her toward the main terminal. She was glad to get off the train and back on solid ground. There were things to think about, but first she needed a cup of loud black coffee.

The restaurant warmed her up. She felt the heat on her face, on the back of her hands. She heard the bright clink of flatware, dark whispers of conversation, the resonating shine of chrome-lined counters and stools where she sat.

“Coffee?” the man asked when the waitress came over.

“Coffee.” Calla said. While she waited, she fed the baby a half a bottle of water.

The coffee came hot. Calla considered, then decided against, the cubes of sugar and the metal pitcher of cream. She would take it black and brightly steaming. While rocking the baby, she poured coffee into the small saucer to cool it, then sipped from the saucer until the baby was finished with his bottle.

“Interesting way to drink coffee,” said the man. When she didn’t answer he said, “You worried about something?”

“Look, I don’t know about this. My husband won’t like it if I miss the train.”

“What he doesn’t know won’t hurt him. Just wire him that the train got delayed or your got lost, or they lost your trunk. That could happen.”

“What about my baby? I can’t take him to no jazz clubs.”

“No problem. I’ll phone my mom up. She’ll be glad to baby-sit for us. She loves kids.”

“I don’t know.”

“Sure you do. Wait here. I’ll be right back.” He gulped down his coffee and walked out to a bank of phone booths on the other side of the station.

“What have I got myself into?” she asked the baby. “His mama won’t do it and that’ll be it.” She patted his diaper as he bounced and hummed. Calla thought of taking the baby down, but she kept him there, a small timid comfort.

“Maybe what your daddy don’t know won’t hurt him. Wonder what it’s like to dance and sing all night.”

“Is this seat taken?”

A big woman, red muffler wrapping her neck and chin, politely sat on the stool next to them. She signaled with one finger for a cup of tea. She unwrapped her face, unbuttoned her smile.

“Cold enough for you?” she said.

“Sure is.”

“That’s a fine little boy you’ve got.”

“Thanky.” She smiled at the baby’s quiet blue eyes. “I always thought so.”

The woman dropped two sugars and a teaspoon of cream into her tea. “You have quite a load there.”

“Guess so.”

“Your husband’s giving you a hand, then?”

“My husband’s in Washington. I’m on my way to meet him.””But the man who just left?”

“He ain’t my husband.” Calla felt the rush of embarrassment and anger. “Not that it’s any of your business.”

The woman sipped her tea. “Of course it isn’t. Didn’t mean to intrude.”

“He’s just a friend I met on the train from Nashville. He’s real nice. He offered to take me around to see Chicago and go to a couple of places. Things like that. He’s gone to call his mama to see if she can baby sit for my son.”

The woman didn’t look up at Calla. She stared straight ahead, the tea cup touching her bottom lip. Calla followed her line of sight to the clock on the wall. The train to Tacoma was set to leave in fifteen minutes. The boarding call would come soon. Calla shoved her hands in her pockets, feeling the sewing kit, an empty bottle and the telegram.

“I sound stupid don’t I?”

“I didn’t say that.”

“You didn’t have to. My friend’s just got this way about him.”

“What’s his name?”

Calla searched their conversations and realized they had never introduced themselves and that she was considering giving her son to a woman she’d never met, even one who was probably harmless. She looked back at the clock.

“Lady, I got to go.”

“Let me help you then.”

“No thanky. I can handle it.”

“Now girl, a baby and a trunk is too much for anyone alone. Let me help.” She held out her arms to take the baby.

Calla pulled away. “If you’re wanting to help, carry the trunk.”

The woman smiled without a sound: her eyes whispered a promise. “All right then.” She finished her tea and hefted the trunk in an avalanche of motion. “Such a big trunk.”

Calla held the door. “Everything I own.” The wind met them with gust of glistening air. The woman’s face, raw against the cold, turned bright pink, then dull red before they climbed the steps to the platform. While Calla held her son close, the woman hoisted the steamer trunk to her shoulder, seeming to swim in the sea of passengers.

“Thanky very much,” Calla told her when they reached the train. A Red Cap, signaled by the woman, loaded the baggage.

“Take care.” She patted the baby through the blanket and wrapped the scarf around her head and neck then stepped into the crowd until she disappeared, swept away.

Calla stood above the churning crowd, searching, separated by the wrought iron rail. “Please don’t come back. Don’t tempt me again.”

“Boarding!” the call came down the line.

Calla caught a glimpse of a bobbing face in the crowd. She clutched her son until he cried. The train blew a dirge-like horn: people covered the platform like fog. The man grabbed the railing and jumped up to the edge of the platform.

“Found you!” he said.

“Boarding!”

“Stay. We’ll see the sights.”

Bodies pushed past her, careening in different directions, as if she were a smooth, hard stone in a rapid stream.

“Stay!”

She clutched the baby. Her son cried again, unheard in the cacophony of light and motion.

“Stay!”

He held onto the rail with one hand and stretched out the other to her. Somebody yelled for her to board. As she allowed herself to be washed onto the train, she looked past him, eyes unfocused, as if he were a opaque dream lost in the deep shallows of sleep.

September 14, 2016

Candle

We struck

a match

that lit

a wick.

A flame

that we consumed

in a moment stolen

from forever.

But now we

are just shadows dancing on

the cave wall

You and I.

September 13, 2016

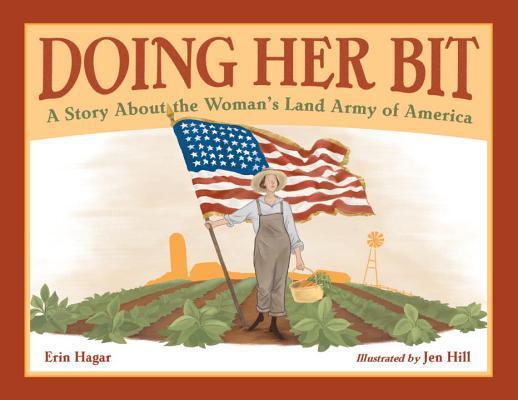

Happy Book Birthday to Doing Her Bit: A Story about the Woman’s Land Army of America

Based on true events, Doing Her Bit traces the history of the Women’s Land Army during World War I. Real-life Farmerette Helen Stevens trains to farm the land, negotiates a position for herself and other women, and does her bit for the war effort. This unique book celebrates the true grit of American men and women.

“Crisp dialogue and small dramas propel this story of a young woman’s summer of service in wartime and women’s emerging power on the homefront.” – Kirkus Reviews

Written by Erin Hagar, author of middle-grade biography, JULIA CHILD: AN EXTRAORDINARY LIFE IN WORDS AND PICTURES, and illustrated by Jen Hill.

Lee & Low’s New Visions Award Expands; Manuscripts Due October 31

First Book and the NEA Foundation are working with Lee & Low to introduce a new middle grade or young adult book by a never-before-published author of color, as part of the publisher’s existing New Visions Award. The collaboration will enable Lee & Low to expand its New Visions Award by selecting and publishing work by an additional new author of color. The winning book is expected to be released in 2018 as a hardcover edition at retail, and as a special edition paperback available exclusively on the First Book Marketplace. Award submission deadline is October 31; full submission information can be found here.

“Educators around the country have increasingly more diverse classrooms, with children from a wide variety of home environments, family structures, religions, cultures, ethnicities, languages and more,” said Harriet Sanford, president and CEO of the NEA Foundation. “First Book has been out in front of the need to provide our educators with relevant, affordable books and resources that they can use in their classrooms every day. Diverse books and resources are not only critical to foster understanding and empathy, they’re critical to learning. To have kids see themselves and their families in books lets kids know that books are, in fact, for them! Sharing diverse stories is a powerful tool for learning and belonging.”

“Educators around the country have increasingly more diverse classrooms, with children from a wide variety of home environments, family structures, religions, cultures, ethnicities, languages and more,” said Harriet Sanford, president and CEO of the NEA Foundation. “First Book has been out in front of the need to provide our educators with relevant, affordable books and resources that they can use in their classrooms every day. Diverse books and resources are not only critical to foster understanding and empathy, they’re critical to learning. To have kids see themselves and their families in books lets kids know that books are, in fact, for them! Sharing diverse stories is a powerful tool for learning and belonging.”

First Book, which has operations in both the U.S. and Canada, works with formal and informal educators serving children in need ages 0-18 in a wide range of settings – from schools, classrooms, summer school and parks and rec programs, to health clinics, homeless shelters, faith-based programs, libraries, museums, summer food sites and more. Almost 32 million children are growing up in low-income families in the U.S. alone; in fact, in U.S. public schools, children in need are now the majority. First Book currently works with more than 275,000 under-resourced classrooms and programs; more than 5,000 new programs and classrooms sign up with First Book every month.

The need for books featuring diverse voices was underscored by feedback from First Book’s membership. In a survey, 90 percent of respondents indicated that children in their programs would be more enthusiastic readers if they had access to books with characters, stories and images that reflect their lives and their neighborhoods. Additionally, 51 percent use books and resources from First Book as a way to enable kids to learn about other cultures and experiences. By aggregating the purchasing power of its network, First Book is able to work with publishers to expand content that accurately reflects diversity of race, ability, sexual orientation and family structure in an ever diversifying world.

“Lee & Low has long been publishing multicultural and inclusive content, and we’re pleased to be expanding the New Visions Award in partnership with NEA Foundation and First Book. First Book has been leading the charge to bring this content to a broader market, and for developing partnerships like this one that make diverse content more affordable and more widely available to educators and children in need,” said Craig Low, president of Lee & Low Books, Inc.

“One only needs to read the headlines to know how important it is to help celebrate our similarities and learn how our differences can make us stronger,” said Kyle Zimmer, president and CEO of First Book. “We are grateful to the NEA Foundation and the team at Lee & Low Books to help us expand our Stories for All Project and our ongoing effort to arm heroic educators with best-in-class resources of all kinds.”

Organizations serving children in need can sign up to access First Book’s wide range of books and educational resources atfirstbook.org/join. For more information on First Book, visit firstbook.org.

September 11, 2016

Tears

I shouldn’t sounds

Like she’s declining

The offer, starting with

Her crisp bronzed tunic,

To peel the skin away

Layer by layer of scale,

Past the fleshy leaves,

Down to the wild heart,

Crisp, sweet and tangy,

And oh so

oh

September 9, 2016

Scent of Apples

My dad, Allison thought as she took the Corvette off of cruise control, is a philosopher. Not a Descartes or a Machiavelli. More like a Will Rodgers, a man who studies every day life and finds meaning in it. If she’d had a penny stock for all the times her dad had said, You get what you pay for and pay for what you get, she could have paid off the car twice over.

Allison left the interstate at the Smoky Mountains exit and was heading up the winding roads to Townsend when she noticed that something was not quite right. Fall had always been her favorite season. Crisp air. Burning leaves gathered with clattering rakes that swooped and scraped the ground. Bags full of bright yellows and reds like blood drops from dogwoods or multi-colored pin oaks or orange maples. But that Fall, the leaves ignored the pageantry and turned from green to ugly brown without so much as an afterthought and lay at the bottoms of the naked trees.

She punched the accelerator and the Corvette cut around a hairpin turn. The valley rolled out below her and she kept to the road and refused to look down. Between Gatlinburg and Townsend, she watched for her parents’ inn. She knew her Mom would be cooking her apples and a hundred bushel baskets would be lining the mud room out back. The kitchen would be sweating apple cider and apple butter and apple this and apple that.

Allison smelled the apples even as she pulled into the driveway of the inn, a hunting lodge her parents had transformed into a bed and breakfast. She carried her bags to the porch.

“Welcome to the Great Smokies,” Mom’s trusting voice came through the transom and when she opened the door, the scent of cooking apples tumbled past her.

“Ally!” Mom opened her arms. “I thought you’d never get here.”

“Whoa, you’re giving me the Heimlich.”

Allison stepped back and shifted the bags to keep her balance at the top of the stairs. Her mom danced after her as Allison twisted away and held the suitcase between them. When her mom finally caught up, she hugged her as hard as she could, giving three quick pats between the shoulder blades, a Dad-hug.

“It’s so good to have you home, Ally.”

She touched her daughter’s face with cinnamon-stained hands that cradled the chin in their flavor. The hands drew away but they held onto an unseen stem that connected them. Her hands abruptly smiled with her voice, “How was the drive?”

“Fine. Can I get in the door now?”

“You got here fast.”

“After what you told me on the phone, what did you expect?.”

Mom picked up the bags.

“Those are too heavy for you. Let me do it.”

“Nonsense.” She disappeared into the house with the bags. Her voice became an echo. “Hooper will be happy you’re home.”

“I wish I were,” she whispered. Allison lingered at the threshold like a drop of cider on the rim of a wide-mouthed jar, almost ringing the bell to let her Dad know he had company.

“Coming?” Mom’s voice came from the fourth step, her face barely above the mahogany baluster as she held the bags and waited for her daughter before she would climb up to the top.

“Let me get in the door first. Hey, you got a new rug. My, we are coming up in the world.”

“Just something to spice up the place. You like it?”

If her mother had seen the way Allison chewed on her bottom lip, she would have known her daughter was lying when she said, “It’s beautiful. It’s good to mix things up a little.”

“Glad to hear it. I know how much you hate things to change.”

“I don’t hate change,” she whispered. “I just hate it when you’re the one who changes things.”

She followed her mom to the first room on the right.

“We thought the blue was perkier than the lavender. What do you think?” Mom said.

Allison said nothing and looked out the window at her car parked in the gravel drive. I’d give anything to be heading back to Charlotte in that thing, she thought.

“Are you listening, Ally?”

“Just thinking.”

“No harm in that.” Mom fixed the bed and firmed up the pillows. She stood beside her daughter and tied back the drapes. “Isn’t the sunshine beautiful?” Then she put the bags on two luggage stands pulled from the closet.

“I’m getting the royal treatment here.”

“Nothing’s too good for my girl.” She turned down the quilt. “Why don’t you get a little rest? You must be worn out from your trip. Kick off your shoes and stay awhile.”

Allison turned away from the window. “Mom, how could you? That’s your canned phrase for guests. What am I, a tourist?”

“Nonsense. And if you keep making that face, it’s going to freeze there, and you’ll be stuck with it, and what would all of your boyfriends say about that?”

“Fine. Be that way. Make snide comments like you always do.”

Her mom clutched a pillow to her stomach and let go of the pillow case that she had held open with her teeth.”Why are you so defensive? Did I say something about your relationships?”

“There. You did it again.”

“Really, Allison.”

From down the hall, Allison heard her father cough. She put a hand on her mother and passed without speaking. Her mother grabbed the hand to hold her there. She slipped free with ease.

“I’m going to see my Daddy.”

“No, I haven’t told you enough. Don’t go in there.”

They swept into the master suite. Beside the window that leaked sunshine into the room, in a bed of cold metal, a tube in his nose from an oxygen machine beside him, Allison’s dad slept covered by a hand-sewn quilt and a brilliant blanket of light. Fresh-shaven, his dentures out and his chin almost touching his nose, he looked like one of the wax heads in Gatlinburg, except he wasn’t moving, even mechanically, and no canned words came out of his mouth. Just the sound of a rattle when he inhaled and the smooth hum and click of the air machine reminded them that he was still alive.

Allison backed into the hall. Her whisper was as sharp as a paring knife. “He looks awful. Why did you let me go in there?”

She ran to her bed and dropped onto it. Her mom stroked her hair and kissed her head and Allison could smell the nutmeg in the apron.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t want it to be like this.”

“Allison?” Her Dad called from down the hall. His voice was a rattle. “Is that you?”

“He’s calling me.”

“Stay here.” Mom went to shut his door. “No, Allison’s not here yet, dear. Would you like a drink of something?”

After she had tended to him, Allison’s mom led her daughter by the hand to the round oak table in the far corner of the kitchen, where they sat down with some hot cider.

Allison took one look at the cinnamon stick in the cup. “Can I have some coffee please?”

“Coffee?”

“Think I’ve lost my taste for cider.”

“One coffee coming up.”

She sighed and served the coffee black in an oversized stoneware mug that Allison drank from quickly, though the coffee was too hot for her taste. Then she remembered last night when she had answered the phone and heard Mom’s voice and knew something was wrong. Except for the cat curled up in her lap and the half-empty bottle of Chardonney on the night stand, she was alone. Then the phone rang with Mom’s ring and the cat jumped onto the night stand and Chardonney spewed everywhere.

“Is everything all right Allison? You sound upset.”

Allison told her she was fine while she blotted the rug with a sock, swept the stand clean, and wiped her hands on the cat. “And to what did I owe this pleasure.”

“I don’t know how to say this, Ally, so I just will. Your Dad is sick. He has cancer.”

Cancer, she had thought, what kind of cancer, how do you know this? Why didn’t you tell me sooner, you’re crazy, he’ll be all right, he’s going to die, why me, why me? “What did you say. Mom?”

“Cancer,” she’d said, “Lung cancer. It’s spread to his brain. The doctor says it’s stage four already.”

“Stage four? What’s stage four? What happens at stage five?”

Behind her Mom’s voice, she had heard pots clanging in the kitchen. Mom was busy canning, putting up apple butter in wide-mouthed mason jars clattering in the submersed pot racks. “There is no stage five, dear.”

And then Allison didn’t hear the pots clanging and she didn’t feel the wet rug or the cat purring. And she didn’t feel or think anything when she had called in to work after packing and then driven to see her daddy and to prove to herself that he was really sick.

Now at the oak table, the mug cradled in her hands, she repeated, “There is no stage five, dear.”

“What did you say, Ally?”

“There is no stage five, that’s what you said last night.”

“Yes, I might have.”

Mom set out a head of iceberg lettuce, some cold cuts, and the loaf of Roman Meal she always stored in the fridge to keep it fresh. “”You don’t look so good. You really should lie down.” She cut into the ripe tomato with a paring knife then quartered it.

“Look, Mom, I’m a little rusty on the small talk, so let’s quit dancing around this.”

“Would you like a sandwich?”

“Mom! Listen to me.”

She rinsed the knife before putting it in the drainer. “Fine.”

She brought herself and her sandwich to the table. “Fine. We’ll talk about this. And when I say something you don’t like, you will not walk out on me and you will not run to your father for comfort because he can’t comfort you now. Okay?”

Allison nodded so she wouldn’t have to talk. She didn’t like the sound of her voice when she was angry. It broke like cracked ice and she sounded like child.

“You know how he’s been hurting. We thought it was that fall he took last Spring when was pruning, but the pain kept on and just got worse. Finally he went to the doctor and they found this tumor, well these tumors in his lungs and shoulder. Even his brain. I don’t know how he stood it.”

“That’s terrible. How long have you known?”

“A week or so.”

“A week?” said Allison, “You’ve known for a week? What took you so long to call?”

“You know your father. He didn’t want to worry you.”

“Some favor.”

“I’m not lying to you.”

“I know that Mom. Worrying’s the last thing on my mind. I just can’t stand to think he’s hurt for so long.”

“Well, thank heaven for small favors there. They gave him morphine as soon as they found out. Now he wears this patch on his back that doses him. He sleeps most of the time, but he does have delusions sometimes.”

“What kind of delusions?.”

“About working on Army trucks mostly. He’s dropped my transmission twice this week.”

Allison laughed and took the empty cup to refill it and then stood by the window to watch the birds at the feeder, sparrows mostly, then a small cardinal and his mate, even smaller and pale against his lively red plumage. They cracked sunflowers seeds together, piling the hulls higher, eating in unison. A blue jay swept onto the feeder to chase the cardinals away. He pranced around the feeder with his beak working, scattering the hulls, picking around for a few spare seeds. He shrieked delight then flew away to a nearby tree where he could keep watch.

“Asshole.”

“Excuse me?” Mom said from the sink where she rinsed her dishes before setting them in the strainer.

“Talking to this blue jay out here. He’s an asshole. He won’t let anybody else eat, but he’s not hungry himself.”

“That’s a blue jay for you.”

“Why do you put out seed if you know he’s going to hoard it?”

Her mom sighed. “So how long are you staying?”

“Don’t know. It depends.”

“I see.”

Allison let her breath out in measured doses. Always wanting to pin me down, aren’t you, she thought. “I’ll stay as long as it takes or until I’m in the way.”

“Good, it will give us time to talk. By the way, I’ve got some things the hospice doctor brought.”

“Hospice? Surely he doesn’t need those people. They take care of terminal cases.”

“True.” She passed some papers to Allison. “These might help you understand better. I know they did me a world of good.”

Allison read the first line of a pamphlet. “The death of a hospice patient is not an emergency? Then what the Hell is it, a cause for celebration?” She threw the papers on the table. “Excuse me, Mom. Got to use the little girl’s room.”

When she’d gone upstairs and used the bathroom, Allison walked down the hall and knocked softly on her dad’s door.

“Dad? Still asleep?”

He didn’t answer, so she tip-toed in. Seated beside him, Allison put his hand in hers and felt the palms and the veins on the back. They were not cold and she could catch the pulse in them by simply rubbing the backs and listening with her fingers as the blood filled the vessels again. She leaned back in the rocking chair and still feeling the pulse knew he wasn’t dying. His heart was good. But his nails had yellowed from nicotine, the tips grown thick and uneven and his fingers were white, even on the palm side where the white began to grow up the length of his arm, underneath the loose shirt that covered the empty hull of his chest.

“So what do you have to say for yourself?” she said.

His eyes deep in the sockets did not open. The skin on his face was blemished as if it had been bruised by the breathing tube that had worn groves into his cheeks. When she moved the tube aside, she could see the sores scabbing over. The twitch of the line woke him, his hand going to the tube and expertly working it deeper into his nostrils.

“Dad, are you in there?”

She waved her hand over his face and his eyes popped open. He snatched her wrist with one hand and her thumb with the other.

“She’s a little out of alignment here, Ray.”

His left hand a socket wrench, her thumb the engine part, he ratcheted her into place and tightened her bolts, then laid her repaired hand down on the comforter. She giggled before she realized that he was not playing a game but that he was back in Korea underneath a Dusseldorf. His hands searched the air between them until she offered her hand again, but then she withdrew it when he tried to fix it.

“Tell McArthur to stick that in his corn cob pipe and smoke it.”

“Daddy? What’s wrong?”

She put her head up on the comforter that had been hand-stitched from scraps swapped by her mother for a case of apple butter. On the dresser at the foot of the bed she saw the box made of teak that her dad had brought back from Korea. Inside it was a ragged wallet stuffed with receipts and notes and four pieces of hard candy.

No one would mind if she sneaked a candy but she unwrapped it quietly so as not to wake her father who she thought had settled down to sleep again. But the candy was sour apple and she spit it out into her hand.

“Yuck. I hate sour.” She rattled the candy wrapper at him as she bent over the bed. “Did you spike these with something?”

When he reached for her hair, she expected him to adjust her ears, maybe set their timing but he just twisted the ends in his fingers and patted her three times.

“So,” his voice a wind through the dry leaves, “what do you have to say for yourself, getting into my stash?”

“Hey there, stranger. How you doing?”

The smile he mustered lasted until he moved in the bed. “Been better.” Veins spread like branches across his cheeks. He nodded at the candy wrapper. “See you found my surprise.”

“Boy howdy, did I ever. That candy isn’t sour, is it.”

His laugh made him gag. The cough rattled his chest. He sat up heaving. “Napkin.”

She panicked for the box of tissues then practically shoved a handful of them against his mouth. A long stream of phlegm followed the Kleenex away from the mouth when he cleaned himself. He collapsed onto the bed, drinking oxygen from the tube like a straw in water. He pushed the tissues into her lap. She jerked away and threw them on the floor on her way to the bathroom sink where she washed her hands. She heard him over the water.

“Do I make you sick or something? Do I? Get out then, if that’s how you feel.”

“I’m sorry, Daddy,” she called to him and sounded as blanched as her hands under the hot water. “I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings.”

As she watched from the bathroom, his hands fluttered to his face and probed for the tube, reset it, then perched on his brow, tugging the wrinkles on his forehead.

“Time for my medicine,” he said.

She shook her hands dry as she went to him, at the same time measuring his mood and the distance between them so that she could catch hold of his ruffled hands before she spoke.

“What’s wrong? What did I do?”

“Time for my medicine. You deaf, soldier? Boy, you better get a move on.”

In the room’s fading light she let go of her father when she found she had no strength to hold him still. He pick-picked at his eyebrows. His arms made a cross on his chest that spastically rose and dropped, then he grasped his shoulders and started to moan. No words were formed by his voice that sounded like a low wind in the foothills.

“Dad? Dad?” She shook him to no response. “Mom!”

To keep herself from running she didn’t kick off her shoes until she got to the landing where she scurried down the steps barefoot.

Get a grip, she thought, don’t let her see you panicked. “Mom?”

Allison’s voice found her Mom in the kitchen. She peeked around the stoves, wiping sticky hands in the apron tied around her thin waist. Her smile fell when she saw her daughter’s face.

“He says he needs his medicine.”

“Thought you were going to the bathroom.”

“I made a little detour.”

Mom ran a glass of water from the sink then she drew medicine into a needleless syringe. “This is for his nerves. Is he anxious?”

“Kind of. He threw a snotty tissue on me and I freaked.”

“You shouldn’t have done that.”

“What was I supposed to do with a napkin full of snot?”

“Throw it away?” Her mom poured a glass from the bottle of sherry she kept behind the Saltines can. “Don’t worry about your father. He’s just not himself.”

“Hospice prescribed the sherry??”

She couldn’t help smiling after she’d drained the glass. “That’s for my nerves, dear. Be back shortly.”

“Shouldn’t he be in the hospital?”

“What good would that do him? He wants to be at home with his trees and his old house and his family. You know how he feels about hospitals.”

“But where is he going for treatment?”

“It’s too late for treatment, Ally. I thought I’d told you that.”

“That’s ridiculous. Why aren’t you doing anything? How can you sit back and let him die? Don’t you love him?”

Her mom stepped around her. “Don’t say another word.”

She watched her mom leave. Reluctantly, she stayed in the big galley kitchen with its two stoves and sinks and punch-metal cabinet doors hiding pots and jars with their patterns of holes shaped like apples. Mom had cut back on the canning but usually the counters were lined with mason jars sterilized in a water-bath and the screw lids would be stacked everywhere in their square boxes.

“This is pissing me off. She expects me to stay here and do nothing and not say anything. Just be a good little girl and shut up.” She stalked to the front door and got her coat from the pegboard. “Forget that. I’m out of here.”

The keys were in the ignition and she had turned on the car. It idled in the drive and she cursed and turned on the radio loud. She looked up at the house and into the window where her mom was holding a cup for her dad to drink from. She turned the car off and went back inside to the kitchen and she threw her coat on the floor.

“So much for that idea. I can’t stand this. First chance I get, I’m heading back to Charlotte. I will not stay here and watch him go.”

Her mom cam in with an empty cup. She looked at the coat. “Going somewhere?”

Allison slapped the table. “I can’t believe this is happening. Not to my daddy.”

Her mother went to her and held her as much as she could as long as she could until Allison regained control. It was a long time before they spoke again, well into the dinner that Mom cooked while Allison drank coffee and thumbed through the phone book absentmindedly.

After dinner was finished and her mom stayed to wash dishes, Allison dressed for bed and took a book with her upstairs to Dad’s room. She sat down and turned on the lamp. He was still sleeping when she noticed how red his skin was and leaned down to check his temperature. She felt his forehead then his neck. His hands were just as hot.

“Mom!” She called down the stairs. “Dad’s burning up. Where’s your thermometer?”

“Coming.”

Her mom brushed past her on the way to the bathroom where she got the thermometer out of a box in the medicine cabinet.

“How hot is he?” Allison said.

“Hundred and two and climbing.”

“What’s the hospice doctor’s number?”

“It’s the orange label on the handset.” The thermometer beeped. “One hundred three point four.”

The number dialed, Allison sat on the edge of the rocking chair and waited for the nurse on the other end to answer, while her mother dabbed at his face with a damp washcloth and pulled back the comforter to give him more air. His body was like a sack of bones and he reminded Allison of the pictures of the survivors of the Nazi Deathmarches. She had to give the phone to her mother when they answered. She could not talk.

When Mom finished with phone, she said, “they’ll be here in a couple of hours.”

“A couple of hours? Is that a joke?”

“They have other patients.”

“And I’ve got only one daddy. Give me that phone. I’m calling an ambulance.”

“You shouldn’t do that. Your father won’t like it.”

“I don’t really care what you say he wants.” She dialed for an ambulance and gave the address. “Now we’ll see what some real doctors can do.”

“He’s not leaving this house.”

In thirty minutes the Rural-Metro ambulance pulled into the drive and the paramedics were led by Allison to her father’s room. Her mother smiled and greeted them.

“He’s got a high temperature and he’s got cancer,” Allison told them when they asked questions. “He’s needs to be in the hospital.”

A blue-shirted paramedic checked her dad’s breathing and the other wrote down the information in a metal notebook.

“Some rattle in his chest,” said the examiner.

“He has pneumonia,” said Mom. “You all shouldn’t have come. Hospice will be here soon.” She slipped by the paramedic and straightened her husband’s bedding.

“Is hospice responsible for his care?” said the writer.

“Yes.”

“No,” said Allison, “they’re not doing a damn thing for him but letting him die. Take him to the hospital so they can do something for him. Now! What are you waiting around for?”

The blue-shirt said, “we can’t transport except in an emergency.”

“What do you call this?”

Her dad woke coughing. He sucked the line for air and sat half up. Mom held tissues to his mouth. Allison caught the men exchanging nods and said, “Dad, the ambulance is here to get you.”

He shook his head and that made him cough until he was bent over. Mom rubbed his back.

“Ask hospice for a suction device when they come,” the writer said. “It’s better than tissues.”

Her father caught his breath and after looking at his daughter, waved the men away. “I ain’t going to no goddamn hospital. Y’all get the Hell out of my house. Didn’t nobody here call y’all.”

“Your daughter did, sir.”

With unsteady hands he pushed the tube into his nose and turned way toward the window and he breathed in the oxygen like it was water and his thirst could not be quenched.

They packed their things. “There’s not much we can do for him. Sorry.”

“I know,” said Mom.

Allison waited until they were on their way downstairs before she rushed after them. She pulled her coat on over her night gown and slipped on a pair of the galoshes. On the porch she yanked the coat of the blue-shirted man. “Where are you going? Get back up there and do your job.”

“Ma’am, your father’s a cancer patient. We don’t deal with that kind.”

“So you only do car wrecks? Do you know how stupid you sound?”

The writer stayed on the porch and signaled the other man to go. “I know your hurting. I lost my mama awhile ago, and that was hard because there wasn’t anything I could do for her, even when she got so bad she screamed for morphine. And Hell, I’m trained to deal with this. Why don’t you just wait for the hospice people?”

“Get away from me. Get your useless ass off the property.”

She watched the ambulance drive away. After a few minutes of pacing the porch, she was calm enough and cold enough to go back in. The door was locked. She reached for the buzzer twice and wanted to beat on the door but she felt ridiculous being stuck outside in her nightgown so she zipped her coat and snapped the collar tight around her ears and over her mouth. Her hands nested in the deep pockets, she left the porch and walked around the house to check the back door.

Behind the mud room on the small back porch, bushel baskets were stacked five high. There must have been a hundred. Allison looked at the back door, then at her father’s orchard. She stepped down off the porch. Beyond her the path turned to packed dirt and branched away in all directions. Leaves covered the paths and she kicked them aside as she walked. The apple trees swayed like rickety dancers too stiff to move and she hunkered into her coat to hide from the wind.

When she was six, her father had rolled her around out here in her birthday wagon. The workers were stripping the trees clean and her dad piled the wagon full of her favorite Granny Smith’s. The stomachache she got from them taught her to hate anything sour.

Another time, her dad fixed up a haunted forest for Halloween and she and her friends screamed and laughed at the dummies hanging in the trees. She herself had almost peed in her pants when her dad dressed up like a skeleton chased them back to the house, kids scattering like loose pebbles.

And when she was fifteen and in love for the first time, her boyfriend carved their initials on a pine sapling on the back row of the windbreak her dad had planted. Now she searched for that tree. It had grown steadily along with the other pines towering over the orchard that had once dwarfed them. At eye level, where a blemish exposed the pine’s heart wood, she found her initials, misshapen but still beside the boy’s. She tried to picture the boy as the man he’d become and saw nothing more than the silly grin full of braces that had cut her lip when they kissed. She moved on to the right side of the orchard. The house was beside her, though far away, and she watched it in the distance on her way to the old caretaker’s cottage.

Now she lifted the unlocked hasp and pushed the door open. The lights till worked. The tools the workers used to maintain the orchard were stacked on racks in the front room and the floor was stained with mud and cluttered with twigs and leaves and needles that made a path to the kitchen. An electric coffee pot and a small microwave had been left on the counter. She used to play house here when she was little and serve her dad play tea. When she was older, she helped her mom feed the workmen here and kept the coffee pot full. Her dad taught her to like coffee and to light the kerosene heaters they warmed their hands on. Back then the cottage was full of life and work, but now it seemed lazy and empty and the heaters were no longer burning. She sat in the middle of the kitchen floor and watched the lines in the linoleum as the day ended and night came on.

When her butt was too cold to ignore, she grabbed at the fixture and the light rolled back and forth across the empty room. Then she caught the bare bulb and put it out. She left the cottage and pulled the door to, shoved a dead branch into the hasp to hold it closed.

Her father never locked the cottage, even though there was a hasp on it. Many days, they’d stand together at the door to watch the workers in the trees or carrying their ladders or climbing down them, their bags full of picked fruit. Then they would pour them into the bins where they’d be sorted out for market. The blemished ones were culled out for her mom to use.

One day all of this will be yours, little girl, her dad would say and open in his arms as if the orchard were a kingdom.

“What I never told you, Daddy, is that I didn’t want it. Never did, even back when this was one big playground.”

When she’d taken a few scuffling steps from the cottage, she stopped. The trees looked dead and the leaves were gone, and the fruit the trees had borne was long gone, probably being spread on somebody’s toast somewhere.

This is all useless, she thought, he worked his whole life to build this place and now he’s dying. What a waste. The trees didn’t care about him, either. They would bloom next spring without him and somebody would rent a neighbor’s bees to pollinate the crop and the fruit would grow and mature without him, and somebody would be hired to do the picking and the pruning and every little nuance that he’d perfected would be done by someone else. He had raised this orchard from nothing, and now it didn’t need him. What a shame he couldn’t see that.

Then for some unknown reason, she thought of the first time she’d helped rake up the Fall leaves and how her dad had let her jump into them headfirst and how she’d come out laughing. Her dad leaned on the rake and watched smiling as she scattered the pile in all directions. Now, she smiled herself and turned in her tracks and to go back to the cottage to get a rake.

The night was clear and she could see well enough to find the ground. In a clearing nearby she gathered a mountain of leaves into a huge pile. She took a running start and jumped in feet first.

“Ow!” She grabbed her butt and rolled on the ground. “Either I’m fatter or these leaves aren’t as cushy as they used to be.”

After she had gathered up more and stacked them high above her head, she belly-flopped and shrieked. Leaves filled up her mouth so that she came out spitting and laughing.

“More leaves. Got to make it higher.”

The pile grew. Each time she dived in, she became more manic and each time she came out giggling like a little girl. She was sweating now and she pulled off her coat. In her gown and galoshes she ran around the pile and sang, her hot breath visible in the wind that cut through to her skin.

“One more time!”

She went in head first. A stick at the bottom scraped her cheek and she shrieked and rolled out from under the bottom. Fragments of leaves decorated her hair along with the twigs and gumballs that stuck to the gown. She found no blood on her cheek but winced from the salty touch.

“Ouch! Good move, dumbass.”

Her first temptation was to call for her mother but she knew she could never explain all the leaves on her night gown.

“She’ll just fuss and tell me I’ll catch my death of cold.”

On the way back to the house, her knees started to ache and she realized her arms and legs were criss-crossed with scratches. Her tail-bone hurt, a left-over from the first jump. The cheek quit hurting but now her faced itched. She left the coat open though the wind was blowing harder and cussed herself for being so careless, so childish.

As she left the orchard, she had no more thoughts and no more memories and her fingers had no feeling. The path returned her to the porch and the empty baskets. The back door was unlocked. She shed her coat in the mud rood, leaving it in a heap on the wood floor, and slipped off the galoshes. Barefooted, she went to wash her face.

“Mom?”

From the kitchen she heard water running and thought she heard her mom crying. When she came up behind her at the sink and saw the shoulders start to shake, she knew Mom was at the end of her rope.

“What’s the matter? Did the hospice people show?”

Her mom sniffled and wiped her nose. “They did, but they….”

“Mom?”

“They, um, said there wasn’t much they could do for him. He might not make it through the night.”

Allison turned off the water and timidly caressed her mom’s shoulders. She wanted to cry too, but she held on and did not let go until her mom turned the water back on to finish the dishes.

After awhile, Allison said, “Is that cloves I smell?”

“It is.”

“That mulling spices?”

“It is.”

Allison said, “I don’t like cider, you know.”

“Care for something to drink?”

From a drawer beside the stoves, Mom took out a paper envelope and shook it as if it were a sugar packet and emptied it into two mugs then ladled out the cider from a simmering pot, filling each cup three-quarters full. They carried the mugs to the table.

“You have leaves in your hair.”

“Really? How about that.”

Her mom looked skeptical but said nothing more about it. Allison sampled the cider, the mulling spices overpowering the sublime apple flavor: cloves, stronger than in the cigarettes she used to sneak into the barn and smoke. She could feel the rush after a few sips. “Whew, that’s some strong stuff. Your recipe?”

“Store bought. I know, I can’t believe it either. This little place in Gatlinburg puts it out.”

“I’m sorry, Mom. I shouldn’t have run my mouth.”

“We have to do what we have to do. Oh, listen to me. I sound like your father.” She made herself smile. “At least you stayed.”

“Yeah. Thank heaven for small favors.”

They both laughed and drank enough to have seconds. The cider and the cloves made Allison feel warmer inside and by the time she thought about her missed supper, she was ready to eat forever.

“I saved you out some food, if you want it.”

Allison took the dinner to her dad’s room. She ate and read a book and watched him and then slept some. After midnight the fever broke. He woke up with his face and hair sweaty. She squeaked by reflex when he tickled her feet.

“You’re awake?”

“You got a towel I could use?” he said.

“Sure thing.” From the bathroom she brought back a hand towel dipped in cool water and wrung dry that she used to wipe his face, hair and hands.

“How’s that?”

“It’ll do in a pinch.”

“How you feeling?”

He patted the tube in his nose. “Still here. You got anything I could sip on?”

“Water?”

“More in mind for some Coke. Where’s your mama?”

“Sleeping. I’ll get you some Coke.”

On the way she knocked and eased open the door where her mom lay in bed pulled into a ball underneath the covers, her pillow lost somewhere on the floor.

“Mom, wake up.”

“Dammit, Hooper. Let me sleep. This isn’t the Army.”

“Wake up.”

The static electricity made her thin gray hair stand straight up when Allison yanked the covers off of her head. “I thought you were your father.”

“He’s better.”

“Let me see.”

She pulled on a housecoat and Allison went downstairs. When she came back with a cup and a straw, her dad was in fresh pajamas.

“Lift your butt,” Mom said as she yanked off the old sheets and balled them up for the hamper then unfolded a clean one.

Allison offered the Coke. He shook his head at the cup and showed her his shaky hands. Instead he opened his mouth to take a sip from the straw. She set the cup on the table beside him among the prescription bottles.

“Mom, let me help you with that.”

The four corners of the fitted sheet were already pulled tight and they spread the cover sheet under him.

“Butt,” Mom said then they tucked in the bottom and made hospital corners that would be the envy of nurse. Allison changed the wet pillowcase.

“Nothing better than a clean bed when you’ve been sick,” Mom said.

“Y’all go on to bed,” Dad said in a few minutes. “I’m okay. Go on.”

“You sure?” said Mom, but he was beginning to drift off. “I guess so. You want me to stay with him awhile?”

Allison led her to the guest room. “I’ll be fine. Get some sleep.”

With them both taken care of, Allison settled in beside the bed on a moon-less night with the clouds hiding the sky. She could see nothing out the window, now that dark had come but she knew how the tops of the trees heavy with leaves, swayed like dancers in the mountain winds that swept down on them at night. She turned on the reading lamp, tucked her feet under to keep them warm and settled in to read.

Within a hour her dad stirred from his sleep. He was covered with sweat.

“You’re burning up again. I’m going to get Mom.” .

“Don’t go. Just sit there.” He shielded his eyes from the lamplight.

“Do you want me to turn this out?”

“Leave it on.”

“Do you want me to get Mom?”

He grabbed her by the wrist. “Don’t leave me.”

“It’s okay, Dad. The antibiotics will kick the pneumonia. You’ll be fine.”

Though she heard her voice in the room, she didn’t feel herself talking and she put the book down to offer him some Coke. He took the straw but he choked and started a coughing jag that left him red-faced and bent over the rail. Blood leaked from the corners of his mouth. With a napkin she wiped phlegm and a lump of matter out of his mouth and then swabbed it with a small sponge.

“Can’t swallow.” His voice was a rasp.

“It’s okay, Dad.”

Allison pressed a washcloth to his forehead and he lay back in the bed fiddling with his oxygen tube as she washed his neck and the backs of his hands. The mixture on the machine was turned up to give him more air. His hands shook and his eyes turned wild for a few minutes until the richer air calmed him.

“I’m here. I’ll be beside you all night.”