David Macinnis Gill's Blog: Thunderchikin Reads, page 10

September 7, 2016

8-Minute Memoir Day 10

Today’s prompt from Ann Dee Ellis’s 8-Minute Memoir: “Messes.Big messes. Small messes. Emotional messes. Physical messes. Spiritual messes. Relationship messes. Scheduling messes. Take your messy pick. 8 minutes. Let it be messy.”

Day 10: Messes

This is about the biggest mess of a dog I ever had. A big, goofy, Brillo-Pad-looking, hot mess of a dog. My father brought him home from work one day, a pot-bellied pup that had barely been weaned. He carried the pup over to us in the front yard, then went inside the house without a word. What possessed him to break the dog home, I never knew, but it was probably the soft heart he kept hidden for decades behind that walnut-hard skin of his.

I took the puppy and let him run around, but his legs were so short, he crawled up at a tuft of fescue grass and got stuck there, little legs whirring but grabbing only air. We laughed at the poor thing while he whined and barked until he finally rolled over and off like a awkward pill bug, earning him the name Roly-Poly. Not the most dignified name, but it fit.

We lived in the semi-country back then, on a horseshoe shaped neighborhood off Cloud Springs Road near Fort Oglethorpe. Our yards were not marked by fences but by the gullies cut between the property to collect storm runoff, so the dogs in the neighborhood ran free. Roly-Poly spent exactly one not inside, before his constant howling got him kicked out. We built a fence out of chicken wire borrowed from my uncle across the street, and I built a rickety wooden box for him to sleep in. Every morning before we go to school, I would take him out to play, and he would stay in his chicken wire Ritz until I got back.

He was a sweet dog, but not overly smart, and I often found him stuck halfway under the chicken wire, trying to crawl out, but he was too fat to make it through the hole that his head had fit in to. He grew fairly quickly and within sex months, he reached the adult weight of 35 to 40 pounds. His gray fur had grown in poofy and patchy, full of large curls and waves, and he had a snout like a schnauzer with a hipster goatee. Great sprouts of hair sprung from his eyes like mouse’s whiskers, and his ears looked like old slippers covered in lint. He had a long, half curled tail like a puffball scimitar, and his butt was four or five inches higher than his shoulders, making him look like a galloping gray wedge. He was not an athletic dog, and his front feet would often get tangled up, and he would flip he over heels and keep right on rolling.

I fed the dog every day, once in the morning and once at night, but he still developed a hankering for the neighbors’ garbage. Like all people in the semi-country, we had learned to secure our garbage cans with the ropes or bungee cords to keep the dogs out. It was a lesson you learned when you get off the bus and found garbage strewn across the front yard and you had to be the one to pick it up, no matter whose dog had done the strewing. Roly especially liked the garbage cans of the people across the street. The youngest boy was as old as my brother, and he didn’t like my dog at all, something he told me most days at the bus stop. That dislike usually came out as threats of what he was going to do to Roly the next time he caught him, but I never took it seriously. Semi-country people like to run off at the mouth, and you can’t listen to everything they say. It’s partly from having Scots/Irish heritage and partly from not having a lick of sense.

One night, we heard a horrible howling sound. I opened the front door to see Roly barreling across the front yard, screaming and holding his head at a funny angle. I came off the porch and grabbed him, trying to hold his head still look enough to get a good look. There was a hole the size of a quarter in his scalp, and it was bleeding profusely. Somebody had struck him with something long and sharp, like they had tried to stab him. Across the way, the neighbor’s porch light went out.

We cleaned the wound and bandaged it, and although he had a white scar on top of his head, Roly seem to just roll with it. Then a funny thing happened. The midsize adult dog began to grow. Within a couple of months, he was a very large dog, probably weighing a hundred pounds. He could easily jump up and put both paws on my shoulders. He also developed a habit of chasing cars, something most my semi-country dogs seemed to enjoy, until he made the mistake of actually catching one. Roly wasn’t the first dog I owned to bite the wrong tire. Two years before when we lived on Fine Street, Peanut got hit by a church bus that I happen to be riding on. There are few things worse than singing, “I’ve Got the Joy Down in My Heart” and hearing the bump as the church bus runs over your dog.

I used to ride the church bus from Highland Park Baptist Church in downtown Chattanooga all the way out to Fairview Georgia, a distance of some ten miles. Highland Park was one of the first mega churches in the country, and they sent their young pastors and repainted school buses far and wide each Sunday to gather the children. A group of us would catch the bus at 8 o’clock sharp, and we would be given Little Debbies cakes as a welcome gift, with the promise of Double Bubble, Moon Pies, and Zingers on the way back home. It was a long ride, so we passed the time singing old church songs like “Deep and Wide,” “This Little Light of Mine,” and “Jesus Loves the Little Children.” That was the last time I rode the church bus. There’s something about running over your pet that makes you lose your taste for Little Debbies and makes you wonder why Jesus doesn’t love little dogs, too.

I was thinking about poor Peanut when we took Roly to the vet to set his leg. The vet wanted to do x-rays and put on a walking cast, but my mother explained the financial facts of life to him. Roly came home with a cast made from a single metal tube wrapped in surgical tape that served as his splint/cast for six weeks. He was already a mess, but it was a pitiful sight watching him drag that metal cast around like a duck tape peg leg. When the six weeks were finally up, I told my mother it was time to take him back to the vet to remove the cast. She handed me a pair scissors and told me they charged fifty bucks to remove the cast, so I would have to do it myself.

The vet had shaved Roly’s leg before putting the tape on, but of course, six weeks was enough for the puffballs to grow back. As I try to peel off the dirty tape, I pulled fur with it. I tried soaking the tape, but it was too sticky, and I finally used my mother’s baby oil suntan lotion to melt the glue. After an hour tugging and pulling, the poor dog patiently licking up the excess baby oil, he was free. Once he realized his leg would bend, he shot across the road, narrowly avoiding a truck driven by one of my cousins, and crashed into the neighborhood’s garbage can head long. From inside the house, there was cussing conniption, and the neighbors flew outside, but I laughed my head off as they stood there shaking their fists, as my hot mess of a dog took off down the street, tongue lolling, like this was the best thing ever. And it was.

The next day, Roly-Poly wasn’t around when I got on the bus. He wasn’t around when I got home that afternoon, either. No one seemed to be able to find him, and I walked around the neighborhood, calling his name, expecting him to come running. I hand wrote a couple of posters and stuck them on Phone post, but nobody ever called about the dog. Days passed, then a couple of weeks, and strangely, I seemed to be the only one in the family concerned.

Then one day I was leaving school to catch the afternoon bus, and a bunch of kids were screaming at a big gray dog running around, jumping on them, and trying to steal their lunch boxes. It was him. Somehow he had managed to travel the six miles from my house to the junior high school. I grabbed Roly, tied him to a post to using my jacket, then went inside to call my mom. She picked us up a half an hour later, looking very put out and not at all nearly as excited as I was to have the dog back. That night when my father came home, I was calling the dog to eat. He shook his head at me, not realizing the dog had come back. It was one of many times he thought I had lost my mind. This time, the look didn’t phase me. My dog was back. I was happy.

A month before, we had decided that we’d had enough of the horseshoe neighborhood. My parents bought a house across the line in Chattanooga, so we would be moving to a new state and starting new schools. The new house had no fence, and Chattanooga had leash laws, so we knew it was going to be a problem having Roly. I had already begun designing a fence to keep him out of trouble.

The next day, my mother told me we were taking the dog for a ride.

The dutiful son, I got into her big green Oldsmobile and called Roly-Poly to the backseat. We drove out of the neighborhood and onto Cloud Springs Road. A few miles later, Mom turned down a road that went deep into the real country. Dirt rose behind the car, and the cicadas began to call out to the night. When we were in the middle of nowhere, she stopped the car.

Let the dog out, she said. I asked why. She explained that we couldn’t take him to the new house. I asked why again.

She got out and opened the door. Roly shot out, dashing into the woods is if it contained a hundred garbage cans. Then it occurred to me that Roly had not run away before. This was his second time she had taken him off, her phrase for dumping a dog on the side of the road. The first time, she done it without me. The second, she driven far enough away to make sure he would never find his way back home again.

How about we go to McDonald’s? She said and turned the car around. Want some french fries?

Behind the car, Roly-Poly emerge from the woods. He ran after the car with all his speed, but as the car accelerated, he fell behind and slowed to a jog. Finally he stopped in the middle of the road and sat down, his eyes filled with a look of complete betrayal. Choking back tears, I caught my mother watching me in the rearview, and I stared back at her with the same eyes.

Spine

Hold still the heart you swore was mine

And crack it open on its spine.

Pretend it’s filled with only air

And it’s broken beyond repair.

For in your heart two lovers clash

And on your lips love turns to ash.

8-Minute Memoir: Day 9

Today’s 8-Minute Memoir prompt from Ann Dee Ellis: “Write about being 8 years old. Do you remember? Where did you live? Who were your friends? What did you do? What were you siblings like? What did your mom do? What did your dad say? What did you hope for? What were you scared of?”

Day 9: Eight Years Old

While wiping counters after washing dishes tonight, I found a pack of playing cards nestled between a bag of bagels and brown bag of bran cereal. They were Bicycle brand, the ones with ornate read pattern on the back that’s been around since 1855. I set the cleaning aside and opened the pack, then sniffed the waxy perfume, a smell that’s been around since at least the mid-70s, when I learned to play poker.

My dad with something of a gambler. Not with his finances, not with his family, nor with his dead-end job. But he with games of chance he thought could lead him to a better life, if he just could manage a long enough winning streak. He fought in the Korean War and worked as a mechanic. There are photographs of him sitting inside the wheel of one a massive truck, a small man in the hole of a mammoth doughnut of synthetic rubber. It was in Korea (Core-rear in his South Georgia glide) that he learned how to gamble. Like many soldiers at the time, he sent much of his pay back home to support his mother. He used the rest of the pay to gamble with and to buy a more than occasional pack of smokes. He got very good at cards during the war. He said it was because they played with Army script, and the paper didn’t feel like real money. Later, when he was stationed in Alaska, he and his buddies spent the winters in their tents, huddled under parkas and playing Deuces Wild to pass the time on those endless dark nights.

He brought the love of the game back home and taught my mom how to play. When I was eight, they used to go over to my aunt’s house and play cards well into the night, huddled around a black formica table wedged into a cramped kitchen decorated with plaster of Paris chickens and filled with cigarette smoke and laughter. We kids used to watch our folks play, catching peeks at their hands and watching the cards fly impossibly fast around the table. Soon, we would get bored and drift off. Maybe go outside to play horseshoes before darkness and the skeeters sent us back inside. We would plop down in front of the television set and watch whatever western or made-for-TV was on. Sometimes, we would fall asleep on the couch, the sound of the poker game chattering in the background.

My father’s voice never made it out of the kitchen. He had a rich, resonant baritone, but he spoke very little. It wasn’t much fun watching him play cards, either. He kept his cards close to his chest. He held them in his left hand, a habit it he’d picked up in Korea, and squeezed the edges while sneaking a peek, as if he were a cheapskate trying to make a penny scream. And then while looking at the cards with one eye, he would flick the corner of the card and make his bet. They called it penny ante poker, but there were nickels, dimes, quarters and even dollars in the pot. The game, though, was all for fun, shared among folks who didn’t have a lot of money. It was understood that if you were winning too much, you would find a way to give some money back to the pot.

I was in fourth grade when we finally convinced our parents to teach us poker. We’d always played cards–rummy, gin, crazy eights, pinochle, and if cousin Earl was around 52-card pickup– – but none of them had the draw of poker or the chance to share some of that pot full of coins. So one night after a visit to my aunt’s in North Carolina, the five of us gathered around the dining room table, and my parents laid out the rules of the game. They started out with the basics. Stud poker. One car down, four cards up. Nothing wild. Nothing much to guess about with Five Card Stud. Just straight up cold nerves and trying to figure out what everybody else had. It quickly became my favorite game, because I had a penchant for counting cards. It was far easier to play the odds with one hole card then two or three, as with my father’s favorite game, Seven Card Stud.

In Seven Card, the first two cards were down (called the hole), and four were laid up on the table so that the other players knew what everyone else had. After four rounds of betting, the final hole card was dealt, and that’s where the fun began. My mom was always chatty, but my father held silent during play at all times—until he dealt. When it was his turn to deal, he kept up a pattern of patter, commenting on what everyone had and making possible suggestions for what each player might be holding. It was through his patter that I learned how to play the table and how to predict what the next cards would be. Intuitively, I guessed the odds, and I could tell how quickly those odds changed depending on which cards were facing up. I was good at spotting patterns, and poker is all about patterns—in the cards and in the people playing them.

Each person in the family had their own style of playing. My sister was very conservative. She never raised more than a dime. My brother wasn’t as conservative, although he had a very obvious tell: If he got what he was looking for, his eyebrows with arch over the top of his classes. My mother was a complete outlier. Her betting strategy, if it was a strategy and not an extension of her personality, was to be as random as possible. She might hold the winning hand and never raise a single time. The next hand, she might bet aggressively from the very beginning, raising and raising again, trying to buy herself a pot.

I had nothing like a poker face. Not at first. I would bet like a madman when I had something good. Or when I had something bad. It didn’t matter. I just like playing the game. I held my cards too far away from my chest, and my sister enjoy taking long, luxurious peeks over my shoulder. She would even mock me for it–because that’s my little brothers are for. In time, I would adopt my fathers habit of holding the cards in the single stack, looking only one before the betting reached the final round. I would squeeze the cards like they were screaming pennies and maybe even add a flick a corner for luck.

I was never silent though, either when it was my turn to deal or when I was just playing. I never spoke in school, so maybe I was saving up for the poker games. My mother would warn me about running off at the mouth, but the warning never seemed to do any good. If the cards were flying, I was talking and cracking jokes. Some of them were even funny. Unlike my father, I never adopted a conservative betting strategy. Even though stud poker has no provision for going all-in, it was not uncommon to see me push my entire stack of coins into the pot and wait for someone to match my bet. I lost often, but when I won, I won big.

After a year of weekend games, all of us could play some poker. When relatives would come to town, we would nonchalantly suggest a game or two of poker. For fun, of course. Thus would begin a marathon session, usually going from early afternoon to the wee hours of the morning. We all developed a distinctive patter by then, especially me and my brother. We were constantly chattering insulting each other, teasing our sister, and messing with our mom. We had enough sense not to bother our dad too much, the same way you don’t tease a rattlesnake.

Most of the relatives were taken aback by the raucous show. One uncle in particular had the misfortune of winning a hand without showing having to show his cards. I looked at him very seriously and said, can I see your hole? Before the poor flabbergasted man could answer, I ripped off a laugh that would make a jackass proud, and the rest the table joined in. It was one of those awkward, hilarious moments that made the games so much fun. We were a family of introverts, sometimes going to all day without speaking (except for my mother who never went any time without speaking). But when we played cards, there was something in the air, a crackle, a feeling of possibility, that the game was afoot, and we were the ones who played it best.

Like all things, the fun came to an end. Not suddenly, but with a long stretched out passing of days. Kids grew up and married or went off to college. We played here and there, but the magic wasn’t there. No game has ever been as much fun sitting around the big table in the dining room, the TV playing behind us, the cigarette smoke in the air, the smell of Pabst and Schlitz for the grownups and sweet tea for the kids. The click of the cards during the shuffle, the metallic click-clink of pennies and dimes, nickels and quarters coming together for the ante.

The lessons I learned at the table will never be forgotten–the first pragmatic application of mathematics in my life, the importance of community and conversation, the ability to distract someone with humor so they couldn’t see the cards on the table, and the keeping of my cards close to the vest so that no one could see them. Most of all, I learned a lesson that’s too often forgotten–when you’re holding the winning hand, go all-in with everything you’ve got and never, ever look back.

September 5, 2016

Bird Lake Morning

How can it be Friday when yesterday was Sunday?

How can I write a poem about a lake

When what I want is to row into

The middle of that lake and

Let the current take the helm

And float, float, float like

Human driftwood to whatever

Shore the current commands

But I know I must make

The current

Must be my own current

And the steer the boat toward the

River that feeds this

Lake and set the oars

Into the gunnels and row

Back against the current

Fighting through it,

Making the hard journey,

Rowing, rowing, rowing,

Oars slicing, dipping, thrashing,

Until exhaustion overcomes

My aching arms and shoulders

And the current takes me

Back to the lake, where I

Must take to the oars

Again. And again. And again.

Me against the current

Until I build the strength

To row myself

Back home.

September 4, 2016

Hungers

The puppies are restless this morning,

Wrestling and bouncing and whining,

Hungry for the walk they can’t have.

Hermina’s rain bands reached us

Last night in the middle of REM sleep.

My dreams played cymbals

For the thunder that shook the windows,

Shook Moose from his rest.

Pillow in hand, I sat next to his crate,

Singing the songs I had sung to my children

When it was dark and they were afraid.

Lewis Farms up the road

In Rocky Point, which is neither rocky nor pointed,

Lets you pick your own

Strawberries, blueberries, and blackberries

For $3.25 a pound, a bargain

Price for fresh fruit.

The car takes you off the exit

To boundless rows of furrowed mounds

Of low plantings ready for picking.

Blackberries grow on racing tendrils

Laced with too many stinging thorns

And too many memories of plucking

Wild blackberries in boggy gulleys

By the highway, watching for snakes,

Bearing the hard gusts of semis

That rushed by,

To ever pay

For the privilege of eating

Something so seedy and tart.

Red fruit fills the first basket,

The first flat and others follow

Blue fruit fills the first basket,

The first flat and too many follow.

Still you keep on

Picking these bargains, paying the price

With a popping back, twisting from

Stooping, thigh and ass muscles aching,

Sneaking the occasional berry

To taste for ripeness until the flavor

Turns bitter.

Still, the plucking and tasting keep on,

Because now it’s all about the picking,

Basket after basket,

Flat after flat,

Row after row.

Row beyond row.

I think of the path

The dogs and I take

Every morning and evening exactly.

One point six miles precisely.

Manicured houses like mausoleums

Faces of persons I nod to but do not know

My unquenched hunger,

When it’s dark and I am afraid,

To plow under

The endless circle of the neighborhood.

Path after path,

Street after street,

Road beyond road,

And sow them with blackberry vines, sharp and wild.

September 2, 2016

Moose as viewed from my lap during Hermine

8-Minute Memoir: Day 8

The prompt for today’s 8-Minute Memoir via Ann Dee Ellis: “Day 8: Birthdays. 8 minutes. So easy.”

Day 8: Birthdays

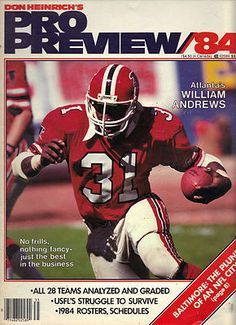

For my 16th birthday, I got a subscription to sports illustrated. Before the Internet, it was the magazine for sports information. Big glossy photos, stories about the biggest stars and also the up-and-coming young players The three television networks had discovered yet. Along with the subscription came the fall preview for both reviews, both pro and college. The preview market was huge back then.

On Thursdays when my mother would stop at Kroger’s on the way home from school and strand me at the magazine rack, I would devour each of the glossies for news about my favorite teams, the Atlanta Falcons and the Tennessee volunteers. Tennessee wasn’t very good at the time, other Atlanta head again resurgent see behind the arm of a Cal graduate who could throw the ball the link to the field that was slower than most geriatrics about escaping the pocket. The past year, the Falcons had drafted a fullback out of Auburn who had become my favorite player of all time.

There was something sacred about those magazines, but those tidbits of information, which we passed back-and-forth at school like the Gospel, adding a few juicy details and made up statistics in the course of the conversation. This is before you could Google any information you wanted, so it’s a lot easier to get away with a little fudging back then. After the preview was read until it was dog-eared, Labor Day weekend would finally come, and the games would begin. I have never enjoyed it football season as much as I did that one, living and dying but that running back and that strong-armed and stiff-legged golden boy quarterback.

The next year, Sundays were for pick-up football, and I often left for the field behind the local junior high before the Falcons finished playing. We would meet on the field, 20 or so of us, some former players, send like me who just love the game and enjoyed the thrill of hitting another human being as hard as you could and then getting up and walking away. One day in early November, the leaves already turned from the trees, the lambs black and naked, the era cool enough that I wore a coat until kickoff, I had of been that in mind when we started. There was a former friend who had insulted me in some forgotten way, and I promised him I was going to get him this week. He was faster than me, more athletic, but he was also a ball hog, so I knew he would return the kickoff.

As our wedge move down the field to meet theirs, I jogged behind the line on the right, biding my time, knowing that the ball carrier would make a sharp cut, try to race around the end, then turn and sprint for the government. I matched his steps laterally, hiding as the blocker in front of me broke the other team’s wedge and caused my target to bounce outside early. I bounced too, planting my right foot and lowering my shoulder, anticipating the electrifying crack of my muscles and bones into his belly, a more satisfying whoop I have yet to feel, even from boxing and karate.

I closed my eyes in anticipation.

When I opened them, I was back-flat on the ground. My teammates were chasing my target, who was 30 yards down the field and about ready to cross the goal line. I tried to sit up and instead, puked. A million tinny chimes buzzed in my head, and vertigo tilted the field at an acute angle. I touch the side of my face and felt the tender spot where two days later a purple bruise would rise between my temple in here, roughly the size of the head of the guy who had blindsided me on the block. In my tunnel vision to take out my target, I had missed him coming around the end, walking onto me as much as I locked onto the ball carrier. He was not a big guy, 30 pounds lighter than me, but quicker, which was a blessing in some ways because if he had been bigger, had had more mass, the concussion I received would’ve been much more severe. Back then, they called it getting your bell wrung. Now it’s called a Grade3 Concussion.

For years, the pros covered up the long-term effects of concussions, and I’m not sure we still know how bad they are. It’s obvious that beating your head against a hard plastic shell on another human being’s head is a poor life decision.

I got up and played the rest of the game, sometimes in the zombie stupor that concussions give you, sometimes in the heightened state of awareness that blended my senses together. Colors began to make sounds. Smells made my body tingle. Much later, I would learn that the concussion had given me synesthesia, a neurological condition that blends your senses so that they overlap. Soon after, I would also learn that the hit had screwed up my vision: It had been 2020 until that day, but six months later, I was wearing glasses. I went back home, walking the highway between the middle middle school in my home, forgetting the jacket left hanging on a branch somewhere.

The next week was full of foggy but restless nights, long days with the loud lights blaring in my face, the teachers’ voices setting off the chimes in my head. Yet I kept going to school, preferring into home. Evenings, I sat in a dark room, a towel or sheet over my head, trying to think, trying to do my schoolwork. My grades slipped for a few of weeks, and I got the only D ever in English, returned with my teacher’s bold red handwriting demanding, what happened? I got my bell wrung, that’s what happened.

In the grand scheme of things, my concussion was nothing compared to the ones that pro and college football players get. Sure, there were long lasting effects beyond headaches, synesthesia, and glasses. When I read, words swim on the page, and my once admirable ability to pick out typos was shot all to hell. I lost the ability to see words the way I always had, but at the same time, I have gained the ability to write them in a different way, using senses I never had before.

When Tennessee played Appalachian State last night, I wasn’t particularly interested in the game. Instead I thought of my daughter, who is playing hockey at a D3 school, receiving no scholarship but working just as hard as the boys who clacked their heads against each other last night. I’m also less than excited about the NFL. As a Tennessee grad, I followed Peyton Manning’s career from his freshman year til the day he retired, watching almost every game he played. I was thankful when he retired because a couple of years ago, I realized I’d been that rooting for a man who had been given everything. He was born into a family financial and physical wealth, taught to be a professional athlete from birth, and given every opportunity in college and at the pro level to be a star. If he had been anything less, he would’ve been a disappointment. I understand that kind of privilege comes with its own set of pressures. I also understand that my children’s lives are not enriched by watching a middle-aged millionaire throwing around a ball. When my daughter’s team has to do fundraisers to pay for their own lockers, how can I care about a sport that allows a university to rake in billions of dollars a year that it doesn’t share with other athletes. It’s a lot to ponder.

My own middle-aged birthday was not too long ago, and I didn’t order a subscription to Sports Illustrated since Sports Illustrated is available online. Or maybe it’s because the sports it illustrates isn’t nearly as glossy and sacred as it used to be.

Broken Circles

I have long legs and big feet, and I wear cowboy boots. So when my flight left LaGuardia, Delta terminal, at 6:45 am, I was in first class because I had to have some place to put my legs. The narrow coach seats aren’t a problem—I’m sort of bony, but my legs, just like the pioneers, need room to spread out. I picked an aisle seat so I could get to the bathroom easily, and I took along a Larry Brown novel to prepare myself for the trip home. It had been a long time since I’d been in the South, and I needed a refresher course.

After I’d stored my backpack, a blonde cliché sat beside me-a pretty, young woman, very neat, personable, power suit, Blackberry. Her hair was cut in a crop, and she wore tortoise-shell glasses.

“Excuse me,” she said as she tried to hurdle my legs. She ended up spread-eagled over my lap.

“Don’t think that’ll work,” I said and unfolded myself. “Let’s try it now.”

“… tall,” she said.

I filled in the blanks. “Six-five. And I’ve never played basketball.”

She settled in. “They don’t make planes for people such as you, do they?” She slid her carry-on underneath the seat in front of her.

“Little in this world fits my peculiarities.”

“Excuse me?” She paused, confused.

“Oh, don’t pay me attention. Just thinking aloud.” I felt awkward. I pulled my book from the mesh pouch in front of me. I’ve heard that bringing thick books on the plane keeps people from talking to you I’ve found it makes them want to bother you more.

She tapped me on the arm. “I said, I love your ponytail,”

“Oh. Thanks.”

“I see a few of them that look nice. Maybe it’s the silver streaks in your black hair. It must be the string tie. You have an accent. Are you from Texas?”

She was a challenge: her lips moved quickly, her mouth opened little. “No,” I said deliberately. “I spent some time in Oklahoma.” I held out the string tie to explain. “Few things fascinate me like mother-of-pearl, the way the light turns fluid and flows into different colors,”

“You certainly don’t sound like a cowboy.”

“I’m not.” I remembered how the judge gave me a choice-jail or Job Corps. The judge had slumped over the bench like a bushy black caterpillar. When I asked him would the Corps let me do any painting, he told me I was a strange boy and that he was sure the Job Corps would let me do all the house painting I wanted. I don’t think he understood. Life in the Corps wasn’t easy, but it wasn’t as hard as home. The sergeant in charge of civilian workers was nothing compared to my daddy. After four years, I had earned enough to go to NYU. I never went back home.

“You look more like somebody from the Village.”

“Soho, actually.”

“You’re an artist, then? Do you have a gallery?”

She must in sales, I thought as she pumped me for my life history.

“No,” I said, looking at my hands spread out on the closed book. My knuckles seemed too big, almost hollow, and my fingers feathered outward, delicate, frail. Woman’s hands, my daddy had always called them. Except for a horny callous on my bird finger, made by holding pencils and brushes too long and too hard, they could’ve been perfect “I just paint.”

“My name’s Cathy.”

“Raymond.”

“Is this trip business or pleasure?”

“Neither,” I said. “I’m going to a funeral.”

She didn’t say much after that. She spent most of the flight reading a magazine, arid I finished my book.

After my plane landed at Lovell field, I bought a copy of me Daily News to look up my mama’s obituary. It was short.

I rented a Chevy and headed north out of Chattanooga to Monteagle, where the funeral was being held. My mama was from the mountain originally, and it was her fondest wish to be buried there when she left this world.

If you were to write a brief history of my mama’s life, it would read like this. Milly May Stevens was in born in 1937 in Altamont, Tennessee. Her family was large even for those days-seven children. Her mama worked odd jobs-cook, housekeeper, school cafeteria server. Her daddy worked at Southern Railways, but he was gone most of the time, blowing his paycheck on liquor instead of supporting his family.

When she was two, her mama gave birth to twins who were stillborn. She met death face-to-face at an early age. At seven, she started doing most of the work around me house while her mama worked. At nine, she going to work with her mama some.

When she was fourteen, two remarkable things happened-she saw her mama beat her brother with a pick handle for stealing cigarettes, and her daddy gave her, for the first time, a Christmas present: a china doll with silky black hair and pretty blue eyes that rolled into the back of her head. By then, she was too old for dolls. She gave it to her sister Liddy.

A year later, she was married to Clyde Barrow, an older boy who worked with her daddy part-time down at Southern. She didn’t think much of him, nor his courtship. He was steel-cable thin, and he didn’t bring her flowers and candy. It seemed to be her time to move on. She might as well be a mama to her own children. At least they would be hers. They settled in Tracy City.

I—her boy—was born right there at home. Daddy couldn’t find work, and so for years, we hop-scotched our way toward Murfreesboro. There we lived for the first time with running water and power. My two sisters were born in the county hospital while Daddy was at the pool hall. As Mama grew older, she worked less and less. By the time she was thirty, she was bone-weary and felt like she’d worked all her days away. By the time she turned forty, her face, never pretty, was bloated and moon-shaped. Her body had long since decayed. For her fiftieth birthday, she lost a foot to diabetes. She didn’t know she was sick until her toes rotted off. Two years later, she died.

My sister Charlene called me with the news. I told her I didn’t know if I could make it She reminded me again that I’d missed our daddy’s funeral, so I told her I would try.

A week later, the day I arrived, they laid Mama out in Altamont Antioch Baptist Church for all to see. Some of her family hadn’t laid eyes on her in twenty years. I was one of them.

When I left Tennessee, I had honestly thought it was for good. When I was growing up, people always said that Raymond Barrow was a strange bird. I guess I was. As a boy, I liked to draw and build things. Once my mama caught me drawing on my bedroom wall. What she didn’t realize, even after whipping me, was that I’d made a fair copy of a Monet I’d seen the picture on one of her catalogs, and the dots and splotches of color had fascinated me.

I frustrated my teachers at school, too. When my sixth grade teacher brought in popsicle sticks so that we could make cute little Civil War cabins, I copied the Golden Gateway bridge, using up almost half of the sticks. In frustration, the teacher gave me an F and threw the bridge into the dumpster. I punched her, and they expelled me. I guess I shouldn’t have done it, but I had the Barrow temper, and I’d learned from my daddy that the way to solve problems was to hit somebody.

Before my accident, I’d been a decent kid. School didn’t make much sense, and neither did anything else; but when I was ten, my world changed. A series of run-ins with John Law followed. Right before I reached legal age, the judge gave me that option—jail or work for the Job Corps. I took the Job Corps, of course.

On the way up the mountain, I rolled all of this history out, like unpacking boxes I had long ago stored away. Dust and cobwebs had settled on my memories, and I wasn’t sure there was much worth keeping.

When I got to Tracy City, I was surprised that everyone knew me, or had heard of me. At G & W’s Esso Service and Tow, I bought a six-and-a-half-ounce Coke from a pull-out machine and wondered how time had forgotten this place. The old pump-boy filled my tank. I asked directions to the church.

“You must be a going to Milly May’s service,” the hunched man said, a generous wad of snuff between his bottom three teeth and lower lip.

I nodded I was.

“Going myself, in a few minutes.” His face seemed pinched, almost gathered al the ends and drawn tight. “Got to close down, first.” He replaced the pump. “That’ll be seventeen-fifty.”

I hanged him a twenty.

“Yeah, I been knowing Milly since, oh, ’51, ’52, back when her and Clyde was just starling out, just after she had her boy. Lord, ain’t seen him in years.” He leaned in, as if sharing a confidence. “He always was a strange one, that Raymond. Hear tell he run off to some sissy-boy commune in New York.”

I raised my eyebrows in surprise.

“If you ask me, it was him and his shenanigans that run her to her grave:’

“I thought it was a stroke. Diabetes related”

“I heard different, if you know what I mean.” He winked and his face seemed to pinch tighter. “By the way, I didn’t get your name?

I got into the rented car and gunned the engine. The Barrow temper had come home with me, I guess. “Raymond.” Gravel pinged off the gas pumps and the man’s ungathered face.

About a half-mile down the highway, Altamont Antioch Baptist Church had fluffed itself into a comfortable nest under a broad canopy that like a leafy parasol, blocked the relentless August sun. Small and white, clapboard siding, a gilded spire as tall as the church itself, the church seemed eternal, as if the passing years couldn’t touch it. A small sign that announced the Sunday School hours and the second to last preacher’s name welcomed me. I didn’t feel welcomed, though. This had been my mama’s church when she was a girl. With its tin sheet roof and whitewashed clapboard siding, it reminded me of a dime-store painting, a piece of Americana, a perfect place for Mama to be married, if she hadn’t run off to the Grundy County justice.

I pulled into the gravel lot the visitation must not have begun because only a few cars were there-a red and black long-bed Ford—a faded-blue Nova, a white Buick Century, its dash cracked from the sun, a black Towne Car, gleaming like a sleek ebony stone. Must be the undertakers car. I said to myself. Good. Maybe I can see him alone.

A semicircular wreath, a mixture of white and. red silk flowers, hung discreetly on the massive oak doors. Antioch, my mama had told me years before, had been built around the turn of the century by local carpenters, most of them original members of the congregation.

When I walked in, I felt those carpenters the legacy of their work. Heart of pine and oak blended splendidly to form the pews, the altars, and the pulpit lines, gentle and sweeping, seemed to emerge from nowhere, converge to form a sweet melody of design, and then disappear into infinity.

I stood, hands almost touching in applause, as the melody began a crescendo. An insistent finger jabbed my shoulder and shattered my reverie. I whirled around, cursing myself for not sensing the man behind me.

“I said, ‘May I help you?’”

“You must be the undertaker,” I said to the broad, flattened, somber face.

“We prefer to call ourselves morticians these days:’ He didn’t look like an undertaker, not ghoulish-more like a car salesman, slick enough but not too slick.” Are you a friend of the family?”

“Family,” I said. I’m her son.

“Oh, I see. I didn’t realize. You don’t sound much like folks around here.” He turned away, walked toward the right wing.

”I’m from… I live in New York.”

As the man turned, the practiced sobriety blotted out the surprise on his face. Most people wouldn’t have noticed, but I had spent a lifetime studying faces. “…must be Raymond.” He pumped the offered hand. “I heard a lot about you. We weren’t sure you’d be coming in. The family will be delighted, just delighted.”

“I’m sure they will.” The old doubts returned: feelings I thought I’d locked away a long time ago pecked at me, chirping a shrill song. My eyes traced the curves of the pews, rolling through the gentle, soothing valleys of wood and stone until the sound of the thoughts faded away.

“To see the deceased?”

My attention focused on the undertaker just as he finished the sentence. I said, “Would I like to see the deceased?”

The undertaker smiled, but his eyes blinked twice betraying his frustration. “Yes, that is what I said. Twice.”

“I believe I would,” I said.

The man led me down the left hallway. The light of the August day filtered through the rooms to the right, and I lingered, not knowing why, in the day-room doorway, fixed on a bird cage made of popsicle sticks. For an instant, I lingered, but I sensed that the man had stopped and was waiting for me. He was talking, but I couldn’t make out what he was saying. “I’m sorry. I didn’t catch that.”

“I was just saying…” He turned into the room and I lost him again.

I followed the man into the small room. My mama’s casket, closed, glowed canary yellow in the sunlight. How tacky, I thought. How utterly tacky. Clydette must have picked it out. Mama’s life had been colorless. Full of smells and stinks and perfumes, yes, bathed in the aroma of bacon in the mornings of sweat and Clorox in the afternoon, and of Emeraude dabbed on her neck for Sunday Service, masking the week’s work. But no color. Her life, was drab.

Her death should have been drab, too. “So Clydette picked it out,” I said.

“Yes, yes. That’s what I said a while back.” His nostrils flared, but the smile remained fixed. “Mr. Barrow, have you heard a word I said?”

I fluttered like a bird pegged with a stone. “No, I’m sorry, I haven’t. You see, I’m…”

“Preoccupied. Full of distraction right now, I know. It’s hard to concentrate in times like these, I know.”

“No, no. You see, I’m…”

A terse pat on the back. A beckoning hand. I flit forward. The casket seems to roar, attack me. My feet search the floor for a foothold, a perch. Two latches thrown. The lid lifted an inch. My hand slamming it down. The undertaker’s nostrils flaring, the terse patting, the vibration of fading footsteps. I am left alone.

Somewhere deep in my recollections, the chirping begins. A soft cheep of a chickadee, the lonesome coo of the dove. Lifting the lid, the first hot wave of Mama’s stench encircling me like a net. Swifts join the song—thousands and thousands of shrieking cries. I reel, the lid springs open. The song fades, leaving me shaking.

She is there. Shrouded in a dress she never owned, great streaks of rouge seem to gouge her cheeks, bright red lipstick on wax candy lip.

A hand touched mine, a gentle squeeze.

“Hello, Raymond.” The woman was pretty. Dark brown hair framing a pleasant, scrubbed face. She held out her arms.

“Hello, Sissy. How are you?” I whispered into her ear.

She held onto my hand. “Raymond, this is my fiancé, Roosevelt Stargin.

Rosie, this is my brother, Mond.”

The young man’s tie was too long, his pants too short, and he lugged too often on his collar, but his smile was genuine. “How do,” he said and extended his hand.

“Very well, thank you.”

“I… I seen some of your stuff, y’know, painting and little buildings and stuff. They’re real pretty, I don’t care what folks around here say. Ow,”

“Watch your mouth, Rosie.” She pulled her heel out of his foot

“Oh, don’t worry about it” I smiled. “I never listen to my critics.”

Sissy and I laughed.

“What’s so funny?” Rosie said, offended.

“I’ll tell you later, Rosie.”

“He doesn’t know?”

“Know what?”

“I’ll tell you later,”

“Roosevelt,” I began, “it’s no big secret I’m …”

“Raymond Earl Barrow, Lord have mercy, I do declare.” The voice careened through the room. A squat, square-faced woman waddled up to me and threw her arms around my stomach…It’s so good to have you home,” She shouted, forming the words carefully.

“It’s good to be here, Clydette,” I said, but I wasn’t quite sure that was true.

Clydette, camouflaged in a canary yellow dress, waved a beefy hand at the body. “Ain’t she beautiful?” she yelled.

“Clydette, darling,” Sissy said, “Mond is deaf, so it don’t do no good to holler.”

She shot her sister that look. “I know that I just get carried away, that’s all.”

“You’re deaf?” Rosie shouted. “But you can talk.”

“He’s not a mute; Rosie. He just can’t hear.”

“Well, I noticed he talked funny, but I just thought that was his Yankee accent How. Do. You. Do. It?”

“I read lips. And don’t feel like you have to slow down. By the way, Sissy, you better make my apologies to the undertaker. He thinks I was rude and not listening, but he kept turning away in mid-sentence. I tried to explain, but he was too busy consoling me.”

Sissy showed me her sweet smile, the one with no teeth bared. “I’ll be glad to, eventually. I think I’ll let him stew a little.” She mouthed the words: He’s a friend of Clydette’s. She picked out the casket. Could you guess?

“Absolutely.”

Clydette plowed into the conversation. “Would you two stop conversating like that? It’s awful distracting. Didn’t Mama tell you it ain’t polite to whisper in public?”

“I wasn’t whispering,” I said innocently.

“You know what I mean:” Clydette frogged me on the arm. “Ain’t the casket just grand?”

“Amazing,” I said.

“Hideous,” Sissy mouthed.

“It’s very… yellow,” I said.

“I know it” Her eyes misted over, and she dabbed them with a monogrammed hanky. “It was her favorite color, you know.”

No, I didn’t know that, I thought.

“Yeller is such a pretty, lively color. Why, you know, I bought me a new dress so’s I could match the casket” She lurched to the coffin and struck a pose, spreading her chiffon like a drape over a statue, covering Mama’s face.

“Clydette,” Sissy rushed over, “you get your tent off Mama.”

“Oh, I’m sorry, Mama.” She patted a cold cheek, arranged a stray hair.

“Just look at her, ain’t she just beautiful?”

“Hellfire, Clydette,” Sissy said, “why don’t you just crawl in there with her?”

Fabricated surprise pierced the armor of her face. “I beg your pardon. I can’t believe you would say such a thing in front of Mama’s body.”

“I don’t know, Clydette,” said I, ”I think you’d make a fine-looking corpse. After all, you’ve already got the dress for it.”

Out came the hanky. “You ain’t changed a bit, have you? Not one bit. You think you’re so much better’n everybody else, mister artsy-fartsy.” She plowed through us. “Sissy, I expected better of you.” She covered her mouth. “Tomorrow, he’ll be back in New York with his faggot friends, and here you’ll be. Don’t come crying to me to make up then.” She marched down the hall.

Bitch, Sissy mouthed.

“Aren’t you afraid she’s excommunicated you?”

“I wish.” She closed the lid of the coffin. “Good night, Mama. Sweet dreams.” The clasps clicked, locked. “Tomorrow or the next day, she’ll come around, begging me to let her forgive me.” She winked at Roosevelt.

“Huh? Oh, yeah. I guess I’ll head on out. See y’all in a minute. Call me if you need anything.”

“Now, Mond, give me some sugar.” After the hug and a peck on the cheek, she said, “I’m glad you come this time. I was afraid you wouldn’t”

“It was time.”

“You seen Daddy yet?”

“No.”

“Going to?”

“Won’t have much choice, considering where we’re going today.”

“You would’ve hardly recognized him. He was thinner. What hair was left was silver. I see yours is getting that way, now. The skin cancer was hard on him. I want to say that he was sorry for the things that… happened.”

My daddy and I had spoken little since I was a boy. I blamed him for most of the lousy life ‘we led. Why don’t you get a job and quit drinking, I once asked him. After he had backhanded me across the kitchen and knocked two teeth loose, he told me it was his house, he’d do what he wanted. I felt the bridge in my mouth, the one that had replaced the teeth.

I peeked into my heart and found little sympathy. “Did he lose any more fingers?” My daddy always seemed to be losing body parts. He’d get drunk and go to work in a mill or shop, and then he’d come home a lesser man.

“No, not after those last two. Mond, you’re a sick boy, you know that?”

When we were kids, Sissy and I had learned a trick to aggravate our sister. Since my accident happened when she was two, Sissy had grown up used to my hearing loss. The rest of the family was always forgetting to face me, I thought on purpose. I learned quickly to read lips as my only means of real communication.

Sissy, though, helped me. By the time she was four, Sissy formed her words for me, and I responded out loud. Our sister said this one-way vocalization drove her to distraction. She swore that it was unnatural, the work of the devil.

“Excuse me, sir, ma’am,” interrupted the undertaker. His palms pressed together. “It’s time for the service to begin.”

Without a sound, Sissy led me to the vestibule. I took my seat on the front pew.

Friends and relatives packed the tiny church, as much to catch a glimpse of the bad son made good as to pay respects to Mama. It seemed to me that the building cracked and groaned under their weight. The temperature was noticeably higher. What earlier had seemed to be a splendid hall had changed into a cluttered cage, and I fluttered in its oppressive heat

The pall-bearers rolled in the yellow coffin. The undertaker, with all the dignity he could borrow, lifted the lid. Even over the heat and sweat, I could smell her, like a mix of old baloney and preservative.

During the service, I entertained myself by tracing the thread lines of the preacher’s embroidered shawl. Veins of golden light danced through a perfect pattern. I delighted in its symmetry and fluid motion. In its design, I found a new painting. People often ask me, where do you get you ideas from? Once I responded that ideas were like sperm—you were born with more than you’d ever need, but you had to wait around for them to be useful. That was picked up by the wire services and made the quotables in several magazines. But to be honest, I have no idea where my inspiration comes from. I really don’t care, as long as it keeps coming back.

By the time I checked my watch, the preacher had gone on for forty minutes.

“… and I don’t know what the Lord has in mind for Milly May Barrow. None of us know what God had in store for Milly May Barrow. We cannot know until we reach the pearly gates of Heaven. And He might not tell us then. But you can rest assured, my children, that God has a plan. He has writ His plan in His Book of Life. Yes, He has a plan. The great God Almighty in Heaven above has a plan for you, sinner.” His eyes bulged and the ligaments strained in his neck like cables laced around a hot air balloon. I knew he was working up a crescendo. Soon, he would be spent, his fury transferred to the faithful. “Now let us pray,”

I had never heard a prayer. Before my accident, my mama hadn’t gone in much for church. She found religion a year of so afterwards, too late for me to hear. I’ve read the Bible, probably more than the preacher himself, but the services didn’t hold much meaning for me. I could tell from the strained faces and purple fury of the preacher that the sound of the words had more impact than their meaning. I couldn’t lip-read a scream.

I bowed my head out of respect. The prayer was over long before I lifted my head. Sissy had to signal me by squeezing my hand. To the faithful, my actions seemed the devotion of a good and loving son, but in truth, I’d spent my time poring over the rich grain of the floor.

The doors to the church flew open to uncage the mourners. Pall-bearers, mostly sons of Milly May’s sisters, carried the bright box. To me, it seemed a vibrant yellow pill.

I stepped into the light awash with the cacophony of colors and scents, the stymied air of the church behind me. Sissy looped her arm through mine and led me to the second limousine. Clydette had piled into the first one.

“How far out is the graveyard?” I said.

“A little ways, off the highway some,” Clydette said. “I want you to be ready, now. It ain’t nothing special, now. Clydette had to make out with what Mama and Daddy had, which weren’t much.”

“This where Daddy’s buried?”

“Yeah.” Several minutes passed. “It hurt Mama something awful when you didn’t come home.”

This isn’t my home, I thought. “I couldn’t see mourning something that I’d wished for years would happen.” I looked away.

Her gentle hand turned my chin to her. “I know you don’t mean that, Mond.”

“Yes, I do. You among all people should know how much I hate him.”

“But he was your daddy.”

“And I was his son.”

The graveyard was stuck out next to a farm house right on the highway. Chain links surrounded the hodgepodge of marked and unmarked graves. We walked to the grave site. A small sign proclaimed it to be THE LAST PIT STOP BEFORE HEAVEN. The pall-bearers hefted the beloved through the maze of graves and over the crumbling oak stump. They set her on the pine boards above the grave.

A row of gray metal chairs trimmed the precipice of the grave. In a few minutes, the chairs filled with the dutiful, and the pine boards split with the great weight of Mama’s yellow casket.

“Our father who art…” The preacher’s lips moved. When I focused on the red clay mud and mixed the hues of the earth with the yellow of the coffin, a radiant orange appeared in my mind. With my eyes for a brush, I painted the dead brown grass and the sullen summer leaves. An autumn breeze swept in, it seemed, and the summer was over brushed with vibrant, cooling color. The heat seemed to fade, and I sat in my metal chair, almost serene.

Out of the comer of my eye, I spotted a dog, a blue-tick hound, snuffling to ground outside the fence, its wet, soppy nose finding the way. The hound dog moved up and down the fence, pensively at first, then frantically.

The preacher had finished. Two cousins from North Georgia, kin of Mama’s, had assembled by the grave to sing Will the Circle Be Unbroken.

Sissy winced, and I knew the singers were probably off-key. The fine capillaries in her cheeks and ears pulsed with blood. The hound dog stopped abruptly, pawed at his ears, then bayed to the heavens as if his heart would break.

I couldn’t hear him—there was no possible way. But my ears rang with the baying, a ringing that seemed to turn into a pulsing gong. The dog reminded me of another dog, one I’d forgotten, or blocked out-I had blocked out so much. Then I remembered.

A fury of light, images of the baying and shrieking of a pup. My daddy cussing the dog, me, my life. The stench of liquor in his pores. Grabbing my head. Beating it against the side of the well. Me screaming, ”I didn’t mean to hurt it, Daddy. I didn’t mean”—Bang—”to hurt it”—Bang—”didn’t mean to”—Bang—”didn’t mean…” The overpowering gong and the roar. Daddy’s nails digging into my scalp, pulling the hair loose in furious clumps, the falling wisps of yellow down. My daddy saying, “I’ll learn you, boy. I’ll learn you.” The darkness pouring into me. The warm gentle flow of blood from one cut ear. My daddy walking away, hands guilty with hair and blood. My mama screaming, running to me. The great clanging of the gong shrinking into faint, electric buzz.

“Accident, my ass.” My tears washed my face, and I knew the truth. My lips trembled, and I tasted salt with the tip of my tongue.

No one would notice, I knew. They would think I was crying for my mama. My body shook and seemed to fade from view. I felt the sensation of falling, spinning into infinity, lost in the world of the first nightly dream.

“Please stop me before I hit bottom,” I said aloud.

I felt Sissy’s gentle fingers in my hand, her soft, downy cheek on mine. I seemed to awaken, and she held me, an unhearing lost child.

Clydette stood beyond us, dutifully dropping a handful of dirt into the grave.

She dabbed her eyes with the hanky. The preacher smiled approval at my grief.

I stiffened, unable to move, as my rage stupefied me. I would have liked to say a thousand things, recriminations, accusations, but I couldn’t I felt mute.

“Son, would you like to . . .” The preacher’ gestured.

I nodded. I grabbed a handful of dirt and lifted it as if to throw it down in some last, triumphant gesture of contempt; but my hand remembered, even if I didn’t. My mama holding me in her arms, “Hush sugar, you be all right.” The glowing yellow sun that seemed to warm her as she held my hands as the blood dried.

My hands lowered and gently opened. The soil, lifted in spite, rolled from my palms into the grave, showering my mama with a sweet, slow melody, the like of which she’d never heard.

Originally published in The Crescent Review, 1994.

8-Minute Memoir: The Real Day 8

The prompt for today’s 8-Minute Memoir via Ann Dee Ellis: “Day 8: Birthdays. 8 minutes. So easy.”

It was so not easy.

The real Day 8: Birthdays

My writing advisees often get a sticky note with with words “Don’t duck” written on them. In this case, I ducked. Not in the writing of the piece but in my decision not to post it. It has been nagging at me since, and because I abhor hypocrisy, especially in myself, this is the real response to the Day 8 Birthday prompt. As I said in the first post, this wasn’t easy, and it took longer than eight minutes.

My baby sister Lisa died when I was nine years old, two days after her eighth birthday. She was eighteen months younger, and as much a baby the day she left this world as the day she came into. When my mother was pregnant, she contracted rubella, also known as German measles. Rubella is a mild disease for the infected person. In an unborn child, it can create birth defects including heart problems, microcephaly, intellectual disability, bone problems, and lack of growth. Lisa had all of these. She was born with profound birth defects that kept her an infant in body and mind for all of her life.

Lisa was always a part of my life. There is part of my early life that didn’t include her sunburst red hair, milk white skin, soft laughter and very vocal crying. When I was a preschooler, we lived in Florida, and my mother stayed at home to take care of us. All of us helped take care of Lisa, my big sister more than any of us kids. When I was four, it was my job to watch Lisa when my mother had to do some chore, to shake rattles for her to grab, to make sure she didn’t roll of the couch, or choke. Lisa suffered from seizures, and if she began to shake, we had to put a spoon in her mouth to keep her from swallowing her own tongue. If the seizures got too bad, my mother would use the spoon to give her a dose of phenobarbital to quiet them. It was my job to fetch the bottle, then hold Lisa’s nose so she would have to swallow. If you got too close, she would bite your finger and not let go. It wasn’t so bad when she was two and had milk teeth, but as she grew older and grew adult beautiful white adult teeth, she would cut blood.

Having an infant wore on my parents. Neither of them were educated, and neither had the coping skills to care for a special needs child. In the days before Public Law 94-142, there were no services provided by the state, so all care fell on my family, especially my mother. In this less enlightened era, people openly shunned us when they saw Lisa, even our relatives. There was no one who would or could watch her for long, and her care became an unending task. My mother had her faults and her weaknesses, but her strength was the love she felt for her children, and if she resented Lisa, it never showed. My sister was part of the family, and things worked okay until my mother talked my father into moving close to her family in North Georgia.

My father liked Florida a lot. He managed a 7-11 and was moving up the ladder. He came home after work and was around on weekends, except when he went out to the dog track with family and friends. He didn’t want to leave, but the neighborhood had gotten dangerous, and my mother missed home. Home meant lots of good things, but it meant changes. The only job my father could get was as an exterminator, and on weekends and evenings, he painted houses for extra money. My brother and I would soon join him, and then later, so would my big sister. With money tight, my mother got a job as a spinner at a carpet mill. She worked third shift so she could be home with my sister. She left for work soon after we went to bed and got home after we were getting ready for the bus. When we got home from school, she was usually napping with my sister, and after dinner, she was nap again. My mother spent most of my childhood sleeping and working. We learned to take care of ourselves while we were helping to take care of our sister. I don’t think we ever thought twice about it. It was the way things were.

We moved a lot back then. The longest we stayed in one house was two years, and we switched schools often. There was always a feeling of impermanence, of disconnection. The only constant was family. That changed too, a few days before Lisa’s birthday birthday. Her convulsions had been getting stronger recently, and the medication wasn’t working as well. Her tiny body would shake, and arms would draw back in what I later learned was a pugilist’s pose. The bright mischief in her eyes had faded and the laugh she had made since I could remember was a rare, quiet thing. Lisa was prone to pneumonia, among other illnesses, so my mother took her to the doctor, and he gave her bad news—news that she didn’t share with anyone. We had a bakery cake for Lisa’s birthday, and as usual, I got to eat her piece after she got her one bite. Everything seemed normal, and my mother pretended it was.

On the morning of February 10, I awoke to the sound of voices coming form my parent’s room. The purple light of dawn was coming through the sheer curtains, and I thought it was strange that my mother was home from work so early. Then I heard my sister laughing and as I would swear later, her saying words. They too quiet to her, but I knew she was having a conversation and distinctly said, “yes.” I smiled and faded back to sleep. An hour later, I awakened again, this time to the sound of my mother screaming my sister’s name.

I tried to to find out what was wrong, but my father met us kids in the hallway and shut the door behind him. He sent us back to our rooms and told us to wait. My parents got dressed, made a phone call, and my mother told us to wait for an aunt to come pick us up.

We waited hours at my aunt’s house. The phone rang many times, and my aunt make more than a few calls, all of them received or made in low whispers than couldn’t hide the concern in her voice. She tried to hide the truth, but even a fourth-grade boy could tell what was happening. On the last phone call, my aunt looked out the window and hung up the phone without a goodbye.

In the driveway, my mother and father got out of the car. They were alone.

When they came inside, my mother’s face was puffy. No surprise. She was the definition of mercurial and wore her moods on her sleeves. My father, though, was stone. Weathered, chiseled from granite, never moving stone. His eyes were red, and when he looked at us standing together, hoping for good news, the tears broke from him like steel melting. We melted too. It was the first time I’d ever seen him cry, and it would be the last. Even on the day years later when a self-congratulatory physician happily told my father had stage four lung cancer, he only nodded and said, “I guess that’s that.”

Lisa’s funeral was a horrific thing for me, a story for another day or maybe for a day that never comes. The weather was brutal cold the day we buried her in the Chattanooga National Cemetery, hide on knobby hill that looked down on threadbare trees, in a grave that would one day also serve as the resting place for both of my parents. The image of thousands of white marble gravestones sweeping up the frigid hill has never left me, and I’m sure if I were to return, there would be many thousands more.

I don’t remember many birthdays from childhood, neither mine or my brother’s nor sisters’s, but I remember that one. I remember, too, the photo we took of us on the front porch, my mother in a platinum blonde beehive, holding the cake and holding Lisa, all of us wearing smiles–even my mother who, by keeping that awful secret inside, gave the gift of Lisa’s last birthday and allowed us to celebrate it with her.

September 1, 2016

8-Minute Memoir Day 7

Directions for today’s Ann Dee Ellis’ 8-Minute Memoir: “Write about something you need to finish. Or many things you need to finish. What’s holding you back? What do you do instead? Or perhaps write about something you did finish and you’re proud of it. Or maybe something you’ll never finish and you feel fine with that. 8 minutes. No stopping. Whatever comes.”

Day 7: Finishing

When today’s prompt came through was posted, my youngest child was finishing packing at literally the 11th hour and fifty-ninth minute of the day. She and I went to sleep past midnight and woke at four AM to load her bags for the trip to the airport. She checked in on time, after removing nine pounds of sweaters and scarves from her checked bag, said her goodbyes, and after a tediously long time waiting for the TSA agent to shuffle through her clothes, walked down the terminal toward the flight that would take her to college. This was my third college send off, but it was not typical: she was flying alone to the northeast where she had billeted for the last two years, so she was familiar with the flight and the route. Except this time she would not be living with the family to play hockey, she would be going to college to do it.

As she walked away, disappearing among the other travelers, I was hit with an overwhelming feeling of heaviness. After almost twenty-seven years of raising children, the last one was leaving. We throw around the phrase empty nest a lot, as if birds have flown away. In truth, it is the nest that is alone, abandon after it has served its purpose. Being a parent means you never finish. The ritual of going to college changes the relationship with your child but does not finish it.

Not that I’m great at finishing things. In seventh grade, I join the school band and chose the to play trumpet. I enjoyed the brashness of the sound, the loud, squawking blue note, the vibration of my lips on the mouthpiece that formed the little rumble from my cheeks that came out as a sonic blast. We got the trumpet from a local music store. The band director told all brass players to get a mute, too, so that we wouldn’t blow the woodwinds away, but the mute was expensive, and my mother told me a sock would work just as well. She wasn’t joking.

When I tried to practice, she banned me from the house. I played outside, scaring the birds out of the trees. When the neighbors complained about the squawking, she banned me from practicing at all. The band director, angry that I wasn’t practicing, sent me to the back of the bad room while the other bass played. He flashed angry looks me each day but said nothing. Within a week, I was hopelessly behind the other trumpets. I tried to learn the fingering of the notes but had no idea of how they sounded.

Then one day, my mother picked me up from school instead of making me take the bus. We drove to the music store, where the manager repossessed the trumpet. The next day, I went to the guidance counselor and switched from Band I to Current Events II, where you didn’t need to practice loudly to learn. When he signed the drop slip, the band director scowled and said, “You had some talent, but you’re lazy. You quit now, you quit for the rest your life. Do you know that?” I stood mute, but inside, I knew that I wasn’t the one who had quit this time.

Not that I hadn’t quit before: Baseball in the second grade, football in the sixth, was beyond our means. You can’t play baseball with a borrowed glove. We can’t play football without pads and helmet. You can’t play basketball when there’s no hoop at home. There are just some doors that don’t open when you don’t have a key. But it wasn’t just about the gear. I quit running, too, when side cramps bent me over. I quit riding a bicycle once, too, while going downhill, and I crashed full speed into our grumpy neighbor’s fence, cracking the knuckles of my left hand. My hand swelled like a puffy oven mitt, but because I could still move my fingers, we didn’t go to the doctor. Two decades later, an unrelated x-ray showed three broken fingers that had long healed.

When you quit things early, you began to doubt yourself. When you doubt yourself, you don’t try new things. There were things that I quit after the band teacher repossessed my self-esteem, but there were things I finished, too. I finished high school, which my parents never did. I finished college–three times. I never quit on my own students when I myself became a teacher.

When I taught Brit Lit, my favorite poem was “Ulysses.” I love to read from Tennyson’s last stanza: “Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will/To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.” I yield many times as a young man, and I still yield is an adult. I have too often yielded to my inner demons, giving into anger and pride instead of listening, often at the cost of friendships that sustained me. Like the idle old king, I know that we are never done, even on days like yesterday, when my daughter’s departure finished one phase of my life, while another had began.

The purpose of writing these memoirs has been to look back, to remember, and to make some meaning in those remembrances, yet now I find myself more and more looking forward instead of backwards, wondering what the future holds.

Thunderchikin Reads

- David Macinnis Gill's profile

- 134 followers