Deepanjana Pal's Blog, page 2

April 6, 2021

March 30, 2021

Pagglait

THIS POST CONTAINS SPOILERS

Among the things that count as acting out or being crazy in Pagglait are:

eating gol gappas

drinking Pepsi

getting a job.

Man, it’s good to be a woman (in a conservative, patriarchal society).

When newly-wed Sandhya becomes a widow, she doesn’t seem to be particularly grief-struck. Some of her unflappable calm is clearly her mind working on autopilot as it grapples with the shock of her husband Astik’s sudden death. Another significant part is her refusal to perform the role that society has assigned to her. Yes, she’s a widow, but she also had an arranged marriage and barely knew her husband before he died. As the men in Astik’s family perform by rote the rituals expected of them, Sandhya grieves for the relationship she didn’t have and the husband she didn’t know. Along the way, she realises her husband had kept some rather significant secrets. For instance, Astik never told Sandhya about his ex-girlfriend and colleague, Aakanksha, whose photo he’d kept tucked among his papers. Neither had Astik shared that he had made named Sandhya as the sole nominee of his life insurance — a detail that in a flash turns Sandhya from an awkward liability to a coveted asset.

Most people would expect the title Pagglait to refer to the madness of a grieving woman acting out, but Sandhya’s actions are more socially awkward than provocative. By the end of the film, what really seems crazy is the conservatism that holds a certain section of society together. The craziness of serving tea in a “special” cup to the Muslim houseguest; of looking to marry off a widow days after her husband’s death because that is supposedly considerate behaviour; of forcing men to live secret lives. Pagglait is keenly aware of how traditions and social practices straitjacket people across genders. It’s also intent upon keeping the focus upon those who have been sidelined by Hindu tradition in particular: the women. For decades, we’ve seen Hindi cinema take stories that would have been better served by a female protagonist and have them told by heroes who occupy the spotlight just by virtue of being biological males. In Pagglait, the exact opposite happens. A man has died and the positions of power are all occupied by men; but the ones who push the story forward and claim agency are the women.

Although initially the death rituals seem senseless (especially because we’re seeing them from the perspective of Astik’s brother Alok, who doesn’t understand why Astik’s death has to mean Alok having to give up everything from decent food to his bed), the stories and symbolism of the rites gain an emotional weight as the 13 days of mourning unfold. Even though women aren’t allowed to participate in these rituals traditionally, the rites end up resonating with Sandhya. Which is why it feels like a proper triumph when on the last day, Sandhya changes a tradition to make it more inclusive. Raghubir Yadav is so good as the odious patriarch and it is particularly satisfying to have Sandhya use his exact words (used earlier in a different context) to make a progressive point. With her words, Sandhya effectively displaces the patriarch and using this ritual, she publicly acknowledges the fact that Nazia is part of her family and community.

One of the loveliest (and least credible) parts of Pagglait is the friendship that Sandhya builds with Aakanksha. Sure, it takes some serious suspension of disbelief, but it’s so nice to see the two women reach out to one another instead of lashing out in a futile attempt to be territorial over the memory of a man. The names of the two women also seem to be carefully chosen. Sandhya, or evening, marks the last period of Astik’s life. Aakanksha, true to her name, embodies all that was possibly aspirational for Astik. Aakanksha is urbane; lives alone in an apartment that’s diametrically opposite to the crumbling structure that is Astik’s family home (with its Indian style loo and strictly conservative codes of conduct); is a successful professional; and has her own car (an obvious metaphor for social mobility).

Through Aakanksha, Sandhya is able to escape the stifling atmosphere at her in-laws’ home, where everyone is hunched under the weight of upholding tradition and hiding their anxieties (or Patiala pegs). Aakanksha’s memories of Astik also help Sandhya decode the little that she has of her husband, like the cupboard full of blue, formal shirts for instance. Sandhya may not have been in love with Astik when he died, but because of Aakanksha, she finally falls in love with her husband — after their relationship is irrevocably over. When Sandhya finally heads out into the big bad world, it feels as though a little bit of Astik is by her side because of Aakanksha’s friendship and his laptop tucked into her handbag. (Three cheers for capitalism! The human is literally objectified into a product, which is supposed to leave us feeling the warm fuzzies. And we do. Because you’ve got to admit that the laptop you’re working on right now is probably your most intimate companion and offers access to most of what is important to you as a person.)

When Aakanksha becomes friends with Sandhya, she opens Sandhya’s eyes to a different world — one in which a woman holds down a job and lives independently (but isn’t necessarily independent enough to oppose her parents and marry the man she loves). So it’s interesting that Sandhya says her homemaker mother is the one who makes Sandhya realise she can get a job and fend for herself. It’s also a nice touch for Sandhya to become a pillar of support for her in-laws. Through Sandhya’s relationship with her bestie Nazia as well as Astik’s mother, father and grandma, Pagglait imagines a new kind of conservative family and a different sort of family of choice.

March 9, 2021

Pavel Borshchenko

I was born in the Soviet Union in a small town in a family of people who were, in a sense, Soviets. For me, the impression was that to be a Soviet person, you simply had no need to decide anything as others had already decided for you, right up to where to work or place of residence, this makes decisions still difficult for me. Therefore, the ’90s were a difficult time when one system collapsed, and the new one did not yet exist or did not know how to live in this new one, especially on the periphery.

“This is reflected in my photographic practice when I look for something rare from that time and can use it in creating an image, thereby seeking compensation in the possession of the thing now and not when it was still relevant but not available.”

Most of the fabrics that my grandmother kept were laid aside in the sixties, they are about that time, they are bright, colourful, but outside the window and on the streets, the reality was different, grey, I wanted to convey this conflict. In this, I see a huge influence of Asian culture on the Soviet cultural standard.

Source: Metal Magazine

February 7, 2021

True Beauty is in the details

Now that she’s worked as a volunteer in Haiti and is raising funds for kids in Africa, Kang Su-Jin’s hands are finally clean.

Now that she’s worked as a volunteer in Haiti and is raising funds for kids in Africa, Kang Su-Jin’s hands are finally clean.So whaddyaknow, writer Lee Shi-Eun didn’t leave Kang Su-Jin as the villain of the piece in True Beauty. Not only does Su-Jin literally go around saving the world in order to repent for her sins at Sae Bom High, she returns home to find forgiveness from her old friends. Is any of this written in a way that could be described as “good”? Not even slightly. While I want to give Lee a toffee for not surrendering to the cliché of the villainising the teenaged girl, the restoration of Kang Su-Jin is very contrived and awkward. I wanted to be moved by her final monologue and it’s obvious that Lee cares about Su-Jin — after all, as a character, Su-Jin is more dynamic and has a better arc than Ju-Gyeong, who is charmingly portrayed by Moon Ga-Young, but doesn’t have much by way of character development — the attempt at redeeming Su-Jin is meh.

Now that True Beauty has ended, I can say with complete conviction that no one should watch past Episode 9 and Episode 16 is designed solely to make fangirl hearts flutter as Cha Eun-Woo, sorry Su-Ho, casts aside his virginal charms and spends the night with Ju-Gyeong. Unfortunately, three chaste kisses and one neck nuzzle are hardly enough to distract you from the cheerfully-lazy writing and the many holes in the plot. (Though, I have to admit, my little desi heart twanged with nostalgia for vintage masala Bollywood when the final climax was a parent’s brain haemorrhage.)

I don’t think anyone was expecting cutting-edge writing and/or piercing insight from True Beauty (for things like that, watch Run On, which is flawed but fabulous). That True Beauty is adapted from a webtoon was reason enough to know that this was going to be fluffy, clichéd and committed to escapism. And that’s fine. Not just that, for all its flaws, True Beauty is still better written than The Prom, which, along with being one of the worst scripts ever, is apparently one of the best motion pictures Hollywood has seen last year. But I digress…

By and large, True Beauty is full of clichés and everything about it walks the straight and narrow path of formula. This is occasionally tiresome, but there is a certain comfort that comes from formulaic entertainment because everything from character to situation feels familiar. Plus it is to the show’s credit that ultimately, True Beauty comes across as the story of how a victim of bullying was able to restore their sense of self and self-esteem, rather than being about a girl who wants to look pretty. True Beauty has a cast (particularly Moon Ga-Young) that has fun and it seems like the crew was giggling its way through the filming, sneaking in details like this moment featuring a hunk of meat and a hunk of Cha Eun-Woo biting into, of all fruits, an apple.

This is not a show with great writing, but despite being thoroughly unambitious in its storytelling, every now and then True Beauty adds a layer to a stereotype, which ensures the formulae doesn’t become a vehicle for only outdated ideas and conventional messaging.

So here, in no specific order, is a rough list of things I’ve enjoyed in True Beauty, because of what’s tucked into the details.

The Hong-Im family

First of all, I love that Im Ju-Gyeong’s mother uses her maiden name (Hong) and that’s not a big deal to anyone. When members of her family call her “Madam Hong”, it’s with love and affection, and not intended as a jibe or a takedown.

Unlike the apartments of the rich families, the Hong-Im home is full of warm colours and patterns that should clash, but don’t. The family dislikes it — “the house is shabby”, says more than one character apologetically — but this is the place that offers them refuge when the family is struck with misfortune. This is the place where the best of chaos reigns and it’s a place of laughter and togetherness despite the Hong-Im family’s constant bickering. What we quickly realise though is that these squabbles are all playful and I love the Hong-Im family tradition of settling fights: make the two squabblers sit down, facing each other; then make them cut each other’s toenails while professing love to one another. Genius. And exactly the kind of resolution that would strike a woman who runs a beauty parlour. Contrast that to the terribly toxic relationship in the Kang family (between Su-Jin and her parents).

The Hong-Im homes is also a contrast to Su-Ho’s flat, with its cool colours and clinical, orderly appearance. When you see Su-Ho hanging out more and more in the Hong-Im home, it makes sense because their home is an inviting, unpretentious space while his flat has the general air of being an aquarium, which is helped by the detail that one of the (backlit) walls has fish as wallpaper. It is definitely not a coincidence that the first time that apartment starts to resemble a home is when Ju-Gyeong’s father is a stowaway.

Gentle men and loud ladies

Apparently, TVN as a network has got grief from some of its audience for commissioning shows with weak women characters. If True Beauty and Mr Queen are any indication, then the network heard that criticism and it’s making an effort to address the problem. I’m still conflicted about what’s happening in Mr Queen, but as far as True Beauty is concerned, props to writer Lee Si-Eun for ensuring the show doesn’t fixate over girls’ appearances or glorify conventional beauty. Also, while she sticks to stereotype (by and large) for the lead characters, Lee’s script reverses traditional gender roles with the supporting characters.

Let’s start with Ju-Gyeong’s parents: Madam Hong (Jang Hye-Jin, who was so good as the North Korean entrepreneur and mum in Crash Landing on You) and Dae-Soo (Park Ho-San, from the heartbreaking and wonderful My Mister). Instead of the mother being the home-maker and the father being the breadwinner, it’s Madam Hong who wears the pants in the household. Not only is her beauty parlour their only source of income, she’s loud, domineering and generally all the things that you’d expect of a patriarch. In contrast, Dae-Soo is the home-maker and his character is treated much like a conventional housewife would be. Everyone talks about how good-looking he is; he likes pretty things (like aromatic candles, which he learns to make with a bunch of other women at the local community centre); and no one notices how much he does at home until he leaves. Dae-Soo is the heart of the Hong-Im family, caring and looking out for everyone who comes his way. Madam Hong is the disciplinarian. They make a great team particularly because you’d expect the opposite from the conventional mum and dad.

Then there’s Ju-Gyeong’s older sister Hui-Gyeong (Im Se-Mi), who is a high-flying executive in a music company and falls in love with Ju-Gyeong’s home room teacher Jun-Woo (Oh Eui-Shik). She likes power drills; he likes poetry. She doesn’t hesitate to grab Jun-Woo for a kiss in the middle of the street; he’s reduced to a mushy, clumsy mess at the sight of her. He ends his day with a little cup of coffee that he sips from delicately; she regularly gets wildly drunk and makes scenes. He’s a poorly-paid teacher who is struggling to repay his student loan; she’s Ms Moneybags and at one point, she cheerfully says that one of the reasons she works is to keep Jun-Woo in luxury. Hui-Gyeong and Jun-Woo’s romance is actually better told than the central plot and among the cutest parts of True Beauty are how she chases Jun-Woo during their courtship and their delightfully chaotic wedding. Like Dae-Soo, Jun-Woo is a sensitive, caring man who looks out for the kids who are his responsibility. Conceptually, he’s a companion character to Ju-Gyeong because like her, he’s also very conscious of being seen as ugly because he has no eyebrows (which may be a nod to alopecia?). The fact that a grown and responsible man also feels insecure about his appearance helps to ensure the audience doesn’t see Ju-Gyeong’s anxiety about her looks as superficial. Much like Su-Ho keeps telling Ju-Gyeong that she’s pretty with or without make-up, Hui-Gyeong is constantly talking about how handsome Jun-Woo is. (Incidentally, the one who offers Jun-Woo a solution to his problem is Madam Hong.)

Domesticating boys

Few things in life have given me as much joy as watching Su-Ho (Cha Eun-Woo) and Seo-Jun (Hwang In-Yeop) battle it out not in the dojo or with fisticuffs, but over dumplings. If you just look at the broad strokes of their characters and actions, Su-Ho and Seo-Jun are very familiar and standard male leads. They have egos, they protect Ju-Gyeong, etc. But then come the details, like Su-Ho spending days learning how to knit and all the boys in Sae Bom High being avid knitters (which is reminiscent of the knitting club that the techie boys of Start Up had). Or Seo-Jun making big, bad Kim Cho-Rong’s heart flutter in the gym when Seo-Jun uses Cho-Rong as a stand-in for Ju-Gyeong. Or Su-Ho and Seo-Jun pulling out all the stops to establish who makes the best dumplings, in order to impress Ju-Gyeong and her family. It’s just so damn cute and it puts forward a distinctly unmacho masculine ideal. Reader, I’m here for it — for both the men and the dumplings they made.

While on the subject of Su-Ho and Seo-Jun, the friendship between them is one of the more well-observed sub-plots of True Beauty. When we first meet Su-Ho and Seo-Jun, they’re frigid towards each other, but there’s an old friendship that’s evident from the way they understand and stand by each other even while sniping at one another. Although the love triangle is supposed to be central to True Beauty, the tension between Su-Ho and Seo-Jun isn’t ever really about Ju-Gyeong. Instead it’s rooted in the guilt and grief that both have been grappling with since their friend Se-Yeon died by suicide. Despite this, Lee is able to make many of their interactions swing smoothly from dark or serious to funny.

The girls are alright

Sure Seo-Jun does a much better job of being a friend than any of the girls manage in True Beauty and yes the bromance is way more fun to watch, but while it lasts, Su-Jin and Ju-Gyeong’s friendship is a welcome departure from the usual catfighting girls that make up the norm in high school dramas. Failed womance notwithstanding, it’s worth remembering that this is not the only friendship between girls in True Beauty. Go-Woon and Ju-Gyeong become friends after Ju-Gyeong helps her get rid of a few bullies. Su-Ah and Ju-Gyeong have a friendship that is simple and uncomplicated (as most friendships tend to be in real life) and ultimately, the other bullied girl who transfers from Yon Pa High School becomes a friend of both Su-Ah’s and Ju-Gyeong’s. Contrary to the convention of the high school drama, the norm in the world of True Beauty is not of girls criticising each other and pulling one another down. Quite the opposite.

The beauty industry and social mobility

It’s hard to make the beauty industry smell of roses in the times we live in because there is so much that is problematic about what is promoted as beautiful and how it’s done, but True Beauty makes a valiant effort (as you’d expect it to since make-up brands are among its main sponsors). Make-up for Ju-Gyeong does make her look prettier — although, it’s worth pointing out that everyone who loves her, from her parents to Su-Ho to Su-Jin to Su-Ah to Seo-Jun, keeps telling her she’s pretty without the make-up too — but the show also reminds the audience at every stage that it’s the bullying she suffered that has convinced Ju-Gyeong she’s ugly. For Ju-Gyeong, make-up is initially a chore, but after a while, it’s something that she enjoys and chooses to do because she is good at it. From feeling irritated at having to put on and take off her “goddess face”, we see Ju-Gyeong’s approach to make-up shift over the course of the show. When Ju-Gyeong does Go-Woon’s make-up, you can see that she’s enjoying the process of figuring out what will highlight Go-Woon’s best features. By the end of the show, wearing make-up is a choice guided by enjoyment and self-care rather than fear of not fitting in.

What’s also interesting is how the beauty industry is a lifeline for both Madam Hong and Ju-Gyeong. It doesn’t feel like Ju-Gyeong is overreacting when she decides she needs an armour after the way she’s bullied in her old school. Make-up gives her that armour and the protection it offers gives Ju-Gyeong the space to recover from the trauma that she suffered. Meanwhile, when Dae-Soo loses the Hong-Im family’s savings, it’s the beauty parlour that Madam Hong runs which saves the day.

There is, however, a stark difference between the way mother and daughter see the beauty industry. Ju-Gyeong is a fan of a make-up artist named Selena who has a large fan following (courtesy YouTube) and runs her own fancy salon. Selena works with celebrities, does events at malls and exudes glamour. Nothing in her world resembles Madam Hong’s humble little beauty parlour, where neighbourhood ladies come to get eyebrows done. For Madam Hong, there’s no glory in running her own parlour. The work is drudgery, her clients often treat her disrespectfully and she wants Ju-Gyeong to do well academically so that she can go to university and essentially leave behind their middle class past. When she finds out Ju-Gyeong wants to become a make-up artist, rather than go to university, Madam Hong is furious. “I want you to say you aren’t going to pursue make-up,” she tells Ju-Gyeong. “Why cosmetology of all things? Do you want to end up like me?” It’s a heartbreaking moment, made all the more poignant by the fact that both mother and daughter are lashing out at each other because they don’t know what the other is going through. We mostly see Madam Hong being a dragon and it’s only when she says, with tears of frustration and helpless rage in her eyes, “Do you want to end up like me?” that we realise how much she’s buried under her theatrical grumbling.

Even when Ju-Gyeong’s chain is being yanked by the bratty idol, there’s a sense that the part of the beauty industry that Ju-Gyeong belongs to is more upscale than Madam Hong’s neighbourhood parlour. It’s almost as though Ju-Gyeong and Madam Hong’s careers reflect how K-beauty has gone from being a small-scale enterprise to a glossy industry in the space of one generation.

Which is why the scene in which Hui-Gyeong’s getting ready for her wedding is so heartwarming, because both Ju-Gyeong and her mother are at work. Madam Hong is seen in her hanbok while Ju-Gyeong is in a dress — two generations of Korean women, the younger standing on the shoulders of the older.

Move = Fantagio?

This isn’t a reason to watch True Beauty, but I found it very amusing that one of the sub-plots is about a CEO resigning from an entertainment company after the company’s management is accused of behaving unethically with its talent. Around the time True Beauty started airing, Fantagio got a new CEO. I’m not saying the two are connected, but what a coinkidink… .

In True Beauty, the company, Move, is where Hui-Gyeong works and the CEO is Su-Ho’s father (Jung Joon-Ho, who was in the completely insane Sky Castle). The Move office has posters of groups managed by Fantagio, the company that manages a number of actors and idols (including Cha Eun-Woo and his band Astro) and when Seo-Jun makes his debut as an idol, the backdrop for his concert shows snippets from Astro music videos. After Su-Ho’s father resigns, Move seems to change. Under its new management (we don’t see the new CEO), it seems to be a company that cares for its talent and platforms young artists the way they deserve.

February 2, 2021

Kang Su-Jin/ True Beauty

Episode 1

Su-Jin is introduced to Ju-Gyeong. She’s “the goddess” of Sae Bom High School.

She initially says she can’t go to the arcade after school because she has to study, but ends up going anyway. Later Su-Ah tells Ju-Gyeong that Su-Jin doesn’t respond to messages much. The assumption is that it’s because she’s studious and not checking her phone. Much later, there’s a suggestion that her father goes through her phone.

Episode 2

Su-Jin’s ease with Su-Ho. Stark contrast to how everyone else treats him.

Su-Jin notices perv trying to take photos up Ju-Gyeong’s skirt. Not only calls him out, but when he hurries off the bus, she follows. Proper chase and at the end, she catches him. Later tells Ju-Gyeong she hadn’t noticed Ju-Gyeong on the bus until she noticed the perv — it’s like she’s got a radar for abusive men.

When wild rumours are floating about Seo-Jun having beaten some kid, Su-Jin clears the air and tells her friends that he was out of school because his mother was unwell.

During Su-Ah and her boyfriend’s 100 days’ celebration, Su-Jin is the only one who has a normal reaction (i.e. eye-rolling and WTF expression).

Episode 3

Su-Jin gets a message from her father about meeting (a teacher is coming over for dinner). She goes to bathroom and washes hands manically. Two other girls (extras) in the bathroom look properly weirded out by how compulsively and violently she’s washing her hands. At one point, she raises her hands to her face and smells them. Her face wrinkles with distaste. She washes her hands more.

When Ju-Gyeong is running around like a headless chicken, Su-Jin misunderstands and thinks Seo-Jun is ragging her. She goes to the place where Seo-Jun and his boys hang out and tells them to stop bothering Ju-Gyeong.

Episode 4

Su-Ho and Su-Jin — ranked 1 and 2 in class — are asked to solve a maths problem on the board. Su-Ho solves it a little quicker than Su-Jin and you can see she’s upset by this. Later, she asks Su-Ho to join their study group, saying her mother’s been nagging her to study with Su-Ho. He tells her to lie to her mother.

Su-Jin to Su-Ho: “At my house, your scores matter the most after mine.”

Su-Jin to Su-Ho: “Don’t do better than me. Do just enough.”

In the bathroom, all Ju-Gyeong can see is the easy freedom that Su-Jin enjoys of being beautiful — she can wash her face without needing to think of what it will reveal. Meanwhile, Su-Jin asks Ju-Gyeong when she became friends with Su-Ho, after noticing Su-Ho made an effort to explain some maths to her. It isn’t insecurity or jealousy at this point, but just curiosity, which makes sense since Su-ho is so reserved.

Episode 5

Su-Jin tells Seo-Jun to stop bothering Ju-Gyeong (Seo-Jun’s been flirting with her — because he’s cottoned on to Su-Ho’s liking her — and the school is loving the spectacle. Ju-Gyeong just wants to blend in and not stand out, so Seo-Jun’s antics bother her).

On the bus, Ju-Gyeong notices Su-Jin’s hands are painfully chapped. She doesn’t push Su-Jin for an explanation, but gives her a quick massage with some moisturiser. It’s a very sweet, caring moment (and you can see Ju-Gyeong is her father’s daughter). Yon Pa bully gets on to bus right after and seems to recognise Ju-Gyeong. Ju-Gyeong freezes, but Su-Jin steps in between the two of them — literally — and saves Ju-Gyeong. At the bus stop, Su-Jin asks what happened on the bus, but Ju-Gyeong can’t bring herself to admit to the bullying. Su-Jin does seem to guess though — “They act obnoxious if you come off scared. Next time, come off stronger, ok?” she tells Ju-Gyeong.

Su-Jin also scares the girl who has been bullying Go-Woon.

Episode 6

Su-Jin and Ju-Gyeong talk about their fathers after getting their test results. Su-Jin says she’s jealous of the relationship Ju-Gyeong has with her father. She smiles when Ju-Gyeong says there’s nothing to envy since her father’s unemployed and the reason that her family’s lost all their money.

First time we see Su-Jin’s father hit her. It’s clearly not the first time he’s hit her. Su-Jin’s mother stands behind father. Su-Jin’s father: “You think I invested in you to see these grades? can’t even beat that vulgar family’s son. You think you’ll be able to go to medical school at Seoul University?” (Grades — Su-Jin’s ranked second. Vulgar family — He’s talking about Su-Ho. Old notion of class versus new money. The obsession with getting into a top university — adding an Asian obsession to the American high school drama.)

The whole world lands up at the noraebang to save Ju-Gyeong, and Su-Jin clearly relishes beating the crap out of the thugs.

Episode 7

Su-Jin can’t go for baseball game because she has to attend tutoring. It sounds dedicated, but we now know that studying is what she does because she’s terrorised by her father.

Lovely set of scenes where Su-Jin and Ju-Gyeong hang out and get to know each other a little better. Su-Jin admits to stealing alcohol from her father’s drinks’ cabinet — is it innocent curiosity or is she drinking to deal with the abuse at home? Ju-Gyeong seems very innocent in contrast. Su-Jin tells Ju-Gyeong that when she gets stressed — mostly because of her grades, which aren’t good enough for her parents — she washes her hands manically. “I need to fix it, but it’s not going well. … My pride will get hurt, so don’t tell anybody.” (Su-Jin to Ju-Gyeong) First indication that she’s struggling to handle the abuse.

Su-Jin tells Ju-Gyeong that she’s the only friend who knows about the hand-washing, which is definitely a sign of their friendship deepening but also an indication of Su-Jin beginning to spiral?

Su-Jin self-sabotages and does relatively badly on a test. Her rank slips and a teacher gently points out that there is an obvious pattern to her mistakes. Su-Jin seems to have gone deliberately haywire after completing half the test perfectly — it’s like a foreshadowing of what her character does on the show too. Rather than respond to the teacher’s concern, Su-Jin runs away. She bumps into Su-Ho on the way out of the staff room and he notices she’s disturbed.

Su-Ho: What’s wrong?

Su-Jin: Don’t know. You’re annoying.

At home, we see Su-Jin’s mother nursing her. Su-Jin’s father has obviously hit her again. Her mother asks if Su-Jin has a boyfriend and it’s almost as though that would be an acceptable explanation for her “bad” grades. Her mother is also upset that he hit Su-Jin’s face (suggesting that earlier, he was hitting her where the bruises wouldn’t show?). She tells Su-Jin that he’s hitting her because Su-Jin’s rank keeps slipping. Su-Jin walks out.

Su-Jin bumps into Su-Ho at the mall and she pretty much shows him her bruise, only to realise Su-Ho knows her father has been hitting her. She didn’t expect that he’d know it’s been going on for years. She lashes out at him (because he thinks he knows what’s going on with her but still hasn’t done anything concrete?): “You’re so annoying. You don’t know anything. But I’m always struggling to do better than you. I can’t take it anymore! It pisses me off! Everything pisses me off! It pisses me off that I’m always compared to you. I really don’t think I can do this anymore. Why do you have to go to the same school as me? Why don’t you transfer?” Second sign that she’s spiralling. Neither of them realise Ju-Gyeong has seen them hugging.

Episode 8

Su-Jin being gooseberry while Su-Ho and Ju-Gyeong make eyes at one another. The crush on Su-Ho seems a little sudden, as though he’s become her knight in shining armour after that incident in the mall.

Episode 9

Su-Jin bumps into barefaced Ju-Gyeong and Ju-Gyeong tells her the whole backstory. Su-Jin is entirely lovely and supportive. It’s adorable how she literally holds Ju-Gyeong close to her heart to protect her.

Su-Jin figures out Su-Ho and Ju-Gyeong are dating.

Episode 10

Su-Jin tells Ju-Gyeong she likes Su-Ho and also gives Ju-Gyeong a scrunchie (it’s a token of their friendship. They’ll both have the same scrunchie). However, when Su-Jin is alone, her face is just a cold mask of evil. It’s like a switch has been flipped.

Episode 11

Ju-Gyeong tells Su-Jin that she likes Su-Ho (but not that they’re actually dating). Su-Jin’s response is what you’d expect from a friend. She says she’s hurt, but she’ll get over it. “I’d be lying if I said it doesn’t hurt. It does hurt … Don’t be too sorry for me.” It seems like she’s reminding herself as much as Ju-Gyeong that she and Su-ho are old friends, that he’s like an anchor for her.

New girl in Sae Bom High School is from Yon Pa, and used to be the other kid that the bullies picked on.

When Su-Jin catches the new girl sneaking photographs of Ju-Gyeong, it’s difficult to tell if this is Su-Jin looking out for Ju-Gyeong (like with the perv who was photographing her on the bus) because there’s something sinister about Su-Jin now.

Scene in the stairwell is like a repeat of the scene at the mall, except this time it’s Su-Ho being comforted by Ju-Gyeong and Su-Jin is the eavesdropper. We’re supposed to note the contrast — Ju-Gyeong decided to step aside when she thought Su-Ho and Su-Jin were together, but Su-Jin flips out.

Episode 12

Su-Jin’s father hits her for leaving her study session to see Su-Ho in hospital. It seems to be the first time that she dares to meet his eyes when he’s in a rage.

Su-Jin realises Ju-Gyeong is uncomfortable around the new girl and starts engineering awkward situations for Ju-Gyeong. It’s as though Ju-Gyeong feeling weak is making Su-Jin feel powerful. The scene in which Su-Jin brings the new girl to the lunch table is very unsettling. They were all similarly welcoming and friendly to Ju-Gyeong when she first joined Sae Bom High so there’s no reason to suspect any malice and yet Su-Jin is doing this for all the wrong reasons.

When their paths cross with the Yon Pa bullies, Ju-Gyeong’s first reaction is to run away. It’s when she decides to come back to save the new girl that Su-Jin realises these girls are Ju-Gyeong’s old demons. In this scene, Su-Jin is still Ju-Gyeong’s protector and once again, stands between Ju-Gyeong and the bully, but later Su-Jin starts talking to the bully. It’s almost like they’re becoming friends. Su-Jin starts taking photos of Ju-Gyeong for the Yon Pa bully.

Su-Jin steals the necklace that Su-Ho gave Ju-Gyeong.

Su-Ho confronts Ju-Gyeong and she admits that she would rather “abandon” Ju-Gyeong than “lose” Su-Ho. She also throws the necklace into the conveniently-located fire when Su-Ho makes it clear that he’s not interested in Su-Jin in romantically.

After Su-Jin meets the Yon Pa bully, a video of barefaced Ju-Gyeong being bullied in Yon Pa goes up on the school’s message board. Su-Jin doesn’t seem at all bothered and it’s obvious to the audience that she’s the one behind it. It’s a horrible thing to do, but how often do you see a soap opera in which a girl being bullied is given more emotional heft than the male lead suffering a car accident?

Episode 13

Su-Jin’s reading the comments under the video of Ju-Gyeong and one of them points out that this is cyberbullying. She’s sitting at a mirror and avoiding her own reflection.

Su-Ho starts ignoring Su-Jin in school.

Ju-Gyeong goes to talk to Su-Jin and standing at the gate of her house, she asks Su-Jin to deny that she uploaded the video. Su-Jin tells her she can’t stand to see Su-Ho with Ju-Gyeong and she hopes Ju-Gyeong will transfer out of Sae Bom the way she’d run away from Yon Pa. The phrasing seems very similar to Su-Jin lashing out at Su-Ho and asking him to leave in Episode 7.

Episode 14

When Ju-Gyeong comes to school barefaced, Su-Jin is furious. In the bathroom, she attacks Ju-Gyeong and the setting is a reminder of how Su-Jin had been with Go-Woon’s bully. Back then, she’d used violence — she almost kicked the younger girl — as a threat and now she’s attacking Ju-Gyeong using words instead of kicks. In both instances, it’s Su-Jin trying to feel powerful by threatening someone else and you realise what a massive difference details (like age and attitude of the opponent) have to a power balance. Su-Ah bursts into the bathroom and says she can’t believe that not only would Su-Jin upload that video, but she isn’t apologising even now. Park Yoo-Na’s subtle expressions when Su-Ah says “Kang Su-Jin, you’re seriously the worst” are brilliant. Park gets the desperation and fragility of Su-Jin’s character beautifully.

Su-Ah: I thought you would be sorry. I was waiting for you to apologise to her. But is this the kind of person you are?

Su-Jin: Yes. This is who I am. (Once again, there’s a mirror and she’s avoiding her reflection. Contrast to when she’s washing her hands and seeing herself in the mirror.)

Su-Jin bumps into Su-Ho and this time, he doesn’t ignore her. Instead, he asks her what’s wrong and why she’s acting in this way. He also asks if Su-Jin’s father has been hitting her again. She hates him trying to be considerate and tells him to back off. Su-Jin is now entirely alone.

Su-Jin has a face-off with her father and he demands to see her phone. She has a hysterical reaction that makes her parents take a step back. It’s a heartbreaking mix of the energy that comes from complete desperation and helpless rage. Even though she’s stopped her father from hitting her at that moment, this doesn’t feel like a display strength. This is Su-Jin falling apart.

When she comes to school the next day, there’s a cut on her lip. Clearly, the reprieve that her hysterics had got her were temporary and her father’s abuse is getting worse.

On the school message board, an anonymous poster has exposed Su-Jin and now the whole school knows what she did to Ju-Gyeong. The reactions are mostly of contempt. It’s not that they think she’s actually scary. She’s just “pitiful”. Su-Jin runs out of the classroom and Ju-Gyeong follows her. Ju-Gyeong takes Su-Jin’s hand — a hand that Su-Jin keeps washing; a hand that Ju-Gyeong once moisturised because it hurt her to see Su-Jin in pain — and asks her to put this all in the past and start again, but Su-Jin rejects Ju-Gyeong.

Su-Jin: “Do you think I’ll hold on to your hand? Did you believe you and I could go back to how we were?” She walks away, turns a corner and breaks down in tears. Crouching behind a bush, she’s like a hunted, hurting animal.

Bully for True Beauty

CONTAINS SPOILERS.

In the high school drama universe, women and girls aren’t supposed to have friends and they certainly can’t have girl friends. The whole point of this genre is to create a relatable, wish-fulfilment story that has as its foundation the loneliness so many of us felt when we were squirrelling our way through school as puberty-ravaged young adults. Over the decades, the high-school romance (which reimagines the Cinderella story) has proved to be one of America’s greatest exports because of how well it taps into those memories. Even though very few places have school cultures like what we see in fictional American high-schools, the tropes of that genre have been claimed enthusiastically by pretty much everyone around the globe.

Most of the time, the story centres around a girl who is alone and feels like an outcast. She is brought into the social fold when the school’s coolest guy falls for her — usually because she’s undergone a transformation — and as a result, everyone sees her as desirable, just as he does (because what else could a girl possibly want…). If the girl is allowed any friends, they are almost always boys who accept her in their gang because they don’t see her femininity. Very occasionally, she’ll get the company of another equally misfit girl for a few scenes, but usually, the other girls in the high school are modified versions of Cinderella’s stepsisters and exist only to make our heroine’s life hell.

Which is why the real shocker in True Beauty is not that the relationship between Ju-Gyeong (Moon Ga-Young) and Su-Jin (Park Yoo-Na) sours in episode 12, but that the two actually get nine whole episodes to develop a genuine friendship.

Written by Lee Shi-Eun and directed by Kim Sang-Hyub (he’s perhaps best known for Extraordinary You), True Beauty is an adaptation of a webtoon and tells the story of Ju-Gyeong who is bullied in school for being ugly. When circumstances force her family to relocate, she has to change schools. Before joining the new school, Ju-Gyeong learns how to use make-up to transform her appearance. Armed with this new face, Ju-Gyeong finds herself fitting in and making friends in a way that she hadn’t in her old school. The challenge now is to make sure no one ever finds out that she’s an ‘ugly’ girl under the make-up and of course there’s a love triangle because the two prettiest boys in Ju-Gyeong’s school fall for her. However, for Ju-Gyeong and True Beauty, the story of finding true friendship is arguably as important as the romance. After all, the reason Ju-Gyeong is so invested in the new high school is not because she’s dreaming of a boyfriend, but because she wants to leave her bullies behind and find a circle of friends.

True Beauty could have been a painfully shallow story that glorified being conventionally beautiful, but Lee is a smarter writer than that. Like so many good K-drama writers, she folds critiques of class into her subplots and hammers away at a lot of gender conventions. Among the ideas that she explores in True Beauty is how differently a person reacts when they feel like a victim as opposed to a survivor. Lee isn’t trying to remake the high school romance wheel, but she does add complexities to the established tropes. This is why it feels like a body blow when Su-Jin is ultimately reduced to being the mean girl.

We meet Su-Jin in the first episode, when she’s introduced to Ju-Gyeong as the “goddess” of Sae Bom High School. She’s one of the top students in their class, beautiful, rich and seems practically perfect, especially after she chases down a pervert who was trying to sneak photographs of Ju-Gyeong. This is a girl who has never been in detention, solves maths problems without a hiccup and can execute the perfect round kick to put bullies in their place. It makes complete sense that she’s the only girl that the “god” of Sae Bom High, Su-Ho (Cha Eun-Woo), deigns to befriend in school and that everyone is in awe of her.

[image error]

The first hint that this perfect girl routine may be a façade is in Episode 3, when we learn that Su-Jin has a manic habit — when she’s upset, she washes her hands compulsively to the point that her palms are rubbed raw. The only person to whom she confides about this is Ju-Gyeong, after she realises Ju-Gyeong doesn’t see her chapped hands as an ugly flaw, but as a reason to care for Su-Jin. “I need to fix it, but it’s not going well,” Su-Jin tells Ju-Gyeong of her mental health, smiling wryly when Ju-Gyeong says her parents would be over the moon if she was like Su-Jin.

The two sets of parents couldn’t be more different and this is one of the many examples of Lee’s clever writing in True Beauty. Ju-Gyeong’s middle-class family is a loving and lovable jumble of cuckoo characters who live in a house that reflects the family’s colourful chaotic harmony. Her mother is a dragon and the family’s breadwinner. Her father is a teddy bear and house husband, who gets shoved around and taken for granted much like most housewives. Even at her angriest, Ju-Gyeong’s mother is never cruel and you know she’s acting out of love for her family. (Side note: there’s a thesis on social mobility and the beauty industry in the way Ju-Gyeong and her mother, who runs a beauty salon, view cosmetics and the industry. Also, it’s thanks to the beauty industry that both women survive the challenges life throws at them. Take that, all those who want to look down on make-up.) If Ju-Gyeong gets her determination from her mother, she gets from her father the ability to care for those who need a little tenderness, whether it’s Su-Ho grieving for his lost friend or Su-Jin with her rubbed-raw hands.

In contrast, Su-Jin’s parents are part of the elite set, both in terms of wealth and class. Their home is like a grand fortress from the outside, with massive, forbidding gates. Inside, it’s all chandeliers and gleaming whiteness. Su-Jin’s father is a respected surgeon and apparently a friend of Su-Ho’s father, but that’s only for show. “You can’t even beat that vulgar family’s son,” he yells at Su-Jin when she comes second in class (Su-Ho is the class topper). Not only does Su-Jin’s father terrorise her psychologically — an SMS from him is enough to make Su-Jin rush to the bathroom and frantically wash her hands — he also hits her. On one hand, you have Ju-Gyeong’s father who sets up a mini kitchen outside his daughter’s room and cooks her favourite food to get her out of her depressed funk, and on the other, you have Su-Jin’s father who needs to beat up his daughter to feel like a patriarch. Su-Jin’s mother is complicit in the abuse. Sure, she’ll nurse Su-Jin’s swollen face, but while doing so, she tells Su-Jin that her father wouldn’t have hit her if she’d got better grades. Meanwhile, there’s Ju-Gyeong’s mother who, after learning Ju-Gyeong was bullied in her old school, camps outside her new school and is ready to wage war on anyone who dares pick on Ju-Gyeong when she eventually musters the courage to go to school without make-up.

What Ju-Gyeong and Su-Jin have in common are experiences of violence and constructing masks so that no one will guess what they’ve suffered. Ju-Gyeong seems more fragile, with her make-up and her anxiety attacks, but each time she encounters bullies, she comes out of it a little bit stronger. From being the one who’s frozen with fear and an outcast, she eventually stops being the victim and instead is a survivor who doesn’t run away but stands her ground; and finds she doesn’t have to go through this fight alone. At first, Su-Jin seems much stronger than Ju-Gyeong and one of the reasons for this is that she seems ever ready to brawl with bad guys. In fact, these performances of strength are more like Su-Jin’s attempts to compensate for the weakness that she feels because of her father’s violence. The stand that she can’t take against him, Su-Jin takes against all the bullies that she encounters outside her home.

When 12 episodes into True Beauty, Su-Jin turns a sharp right into mean-girl territory, it’s ostensibly because she’s jealous that Su-Ho and Ju-Gyeong are dating. For her to lash out at Ju-Gyeong and sabotage the budding romance is in line with the standard formulae of these storylines, but Lee’s script makes it a point to remind us that Su-Jin’s behaviour doesn’t add up, especially because of the friendship between Ju-Gyeong and her.

That Su-Ho struggles to understand the change in Su-Jin is important because he’s an old friend and also the only one in Su-Jin’s circle who knows about her father hitting her. He knows how hard it’s been for her and that him recognising she’s acting out of character is one of the many hints scattered across True Beauty of Su-Jin spiralling because she just can’t handle the abuse at home. On the face of it, Su-Jin attacking Ju-Gyeong is the love triangle that we were expecting from the moment Su-Jin made her entry in the first episode, but this is not just a simplistic trope playing out. In Su-Jin’s world, Su-Ho occupies a very particular and complicated position. He’s the reason her father hits her, but Su-Ho is also the only one who tries to protect her from her father. He is an embodiment of everything she needs in order to feel worthy. “I’m always struggling to do better than you,” Su-Jin tells Su-Ho in one of the rare moments when she isn’t bottling up her emotions. “I can’t take it anymore. It pisses me off! Everything pisses me off! It pisses me off that I’m always compared to you. I really don’t think I can do this anymore,” she says, breaking down. It’s not that losing Su-Ho makes Su-Jin unravel. She’s been falling apart for a long time, from as far back as Episode 7 when she told Ju-Gyeong “it’s not going well”. However, it’s the straw that breaks Su-Jin’s back and to keep herself from getting more hurt, Su-Jin cobbles out of the broken bits of herself an alter ego. Her own personal not-so-incredible hulk who can be angry and go “Smash!” Su-Jin’s behaviour feels out of character because that’s exactly what it is — she’s become someone else.

In the course of True Beauty, we see Ju-Gyeong go from being a broken victim to a confident young woman. While Ju-Gyeong builds herself up, going from victim to survivor, Su-Jin steadily falls apart. The strong girl we saw in the beginning starts to look more and more hollow as the story unfolds. By Episode 14, she has a new persona — that of a bully. “Yeah, turns out this is the type of person I am,” Su-Jin says defiantly to everyone who is horrified at her toxicity. The only one who realises that Su-Jin’s alter ego is connected to her father’s abusive behaviour is Su-Ho, who asks her directly if her father has been hitting her again. “What do you care?” Su-Jin says in reply, and you can see how much she hates herself for noticing that Su-Ho hasn’t given up on her despite all the terrible things she’s done. He may be angry with her and he may not forgive her, but he also remembers she’s not just the toxic mess that’s lashed out at Ju-Gyeong.

Through Su-Jin’s character, True Beauty offers a look at one of the ways that a bully is born out of old patterns of violence and repression. It’s a reminder that the bad guys weren’t born this way, but were fashioned into their flat cruelty by both circumstance and personality. The arc of Su-Jin’s story gives the stereotype of a bully the complexity of a backstory, but without ever making the audience feel bad for her and Park Yoo-Na’s restrained performance manages this delicate balance. Whatever sympathy the audience felt when Su-Jin’s father hit her or when Su-Ho brushed her aside is sliced away with surgical precision by each act of unnecessary cruelty that she actively chooses, like, for instance, picking Ju-Gyeong as her target (rather than, say, Su-Ah) because she knows the bullies from Ju-Gyeong’s old school.

The change in Su-Jin feels particularly heartbreaking because she and Ju-Gyeong had a truly heartwarming friendship for most of True Beauty, and we rarely see this in popular entertainment in general and K-drama in particular.

You want this friendship to be stronger than Su-Jin’s father’s toxicity and the insecurities that have taken root in Su-Jin as a result of that continued trauma. However, not only is there the cliché of a love triangle that needs to be checked off the drama’s list, a few months’ friendship is rarely enough to be an antidote to years of abuse. It still feels like a travesty that Su-Jin had to be reduced to almost caricaturish evil and the two girls’ friendship couldn’t survive, but while staying true to tropes, Lee also managed to sneak in some welcome surprises. Like writing a drama in which a video of a girl being bullied in school is more emotional, potent and dramatic than a car accident (featuring both male leads, no less). Or giving us a villain who carries in her the twisted pain of being a girl, a victim and a perpetrator in a patriarchal world; who is inherently tragic and yet evokes so little sympathy in us.

February 1, 2021

Hello hellsite

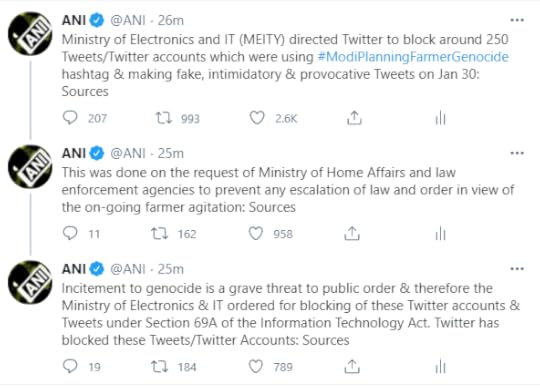

Leaving aside the burning question of why there’s a Y in the acronym for ministry of electronics and IT and also sidestepping the detail of how “ministry of electronics” sounds like the place you show up at to buy a new TV, this is where freedom of expression stands in today’s India. At around 2.30pm today, around 250 Twitter accounts were no longer accessible, including the accounts of the Caravan magazine and Kisan Ekta Morcha, a collective representing the farmers who have been protesting the recently-passed agricultural laws. They were given no reason for this gag order and neither have they been told how long their accounts will be withheld. Twitter issued a vague statement that said the company was responding to a “legal request”.

Some time later, ANI put up the tweets seen above.

Of late, many have applauded Twitter for its liberal values and readiness to resist authoritarianism because first, it started fact-checking tweets by President Donald Trump and his supporters and then, after the January insurrection, it was the first to kick Trump off the platform. In India, Twitter acceded to the government of India’s “request” instead of fact-checking the allegations the state had levelled. I don’t know if there’s a master list of all the accounts that have been withheld, but it’s clear that a lot of them belong to people or organisations that have been critical of the government.

This is censorship, by the government and facilitated by a (foreign) corporation.

And I find myself wondering what the hell I’m doing on a site that’s colluding with the state to stifle dissent. Is it just a bad habit? Do I stick with Twitter because it’s (ostensibly) free and GIF-friendly*? Because there are a few thousand bots and a handful of humans following me on it?

The real answer is: my Twitter timeline.

While Caravan‘s account being withheld is (probably) the first time that an Indian publication has been officially gagged since the Emergency era, subtler forms of censorship have become normal in India today. For many, the first reaction to intimidation is to protest on Twitter in an effort to ensure more people know how state institutions are making a mockery of our constitutional rights and liberties. The weird and miserable truth is that the platform that is helping silence critics and dissenters is also the one bringing together critics and dissenters.

Stand-up comedian Munawar Faruqui being denied bail; the Supreme Court suggesting an actor could be held liable for what a script requires their character to say; photographs of Delhi Police arming themselves with swords; videos of barricades being built in the capital; screenshots to prove 250-ish Twitter accounts have been withheld — I saw all these updates first on Twitter. Today, it was there that people asked whether Twitter USA would withhold the account of a publication like the Atlantic the way Twitter India had done with the Caravan. It’s on Twitter that people pointed out that tweeting in solidarity with protesting farmers is considered “provocative”, but neither the government of India nor Twitter appeared to be bothered by the hate speech that had flowed freely on January 30 when fans of Nathuram Godse celebrated the death anniversary of MK Gandhi. It’s because of journalists on Twitter that I know the Kisan Mazdoor Sangharsh Samiti has asked the “police DJ” to stop blasting songs (from the film Border) close to the protest site at the Singhu border; that Hirokazu Kore-eda’s new film will mark his Korean debut (and star Bae Doo-Na and IU!); and that there’s a Dutch footballer named JizzHornkamp. All this is why I remain on that hellsite.

Despite everything that Twitter fails at and thanks only to a minority of its users, the platform is a place to access reliable information, informed analyses and thought-provoking arguments. For journalists in particular, it’s become an almost invaluable tool for researching, reporting and promoting their stories. Particularly for those who have to contend daily with obstacles like time limits and word counts, Twitter offers something precious — the freedom to explore a subject at length from any angle you want and the possibility of an engaged, interested audience. For readers (like me), Twitter is the magazine that doesn’t exist in the offline world, complete with breaking news, arguments, opinion pieces and feature writing on a dazzling array of subjects. When it isn’t shutting people and conversations down, Twitter can be a vibrant, hopeful space. Somehow, in the middle of this dumping ground for propaganda, deliberate misinformation and toxic conservatism, communities of dissenters don’t just exist but thrive.

When the government of India wants Twitter accounts withheld (indefinitely?**) and when individual accounts get suspended unfairly, it is precisely this culture of dissent that is attacked. The government is hoping that if it can force publications and people off a platform, the loudest voices in the critical chorus will be scattered across the internet. They’ll lose volume and everyone else will feel nervous/ scared. The government is banking on the idea that if dissent is inconvenient, it will fizzle out; that we don’t care enough about the state of the nation to go hopping from site to site to remain informed. The government is hoping Twitter has made everyone lazy.

It’s probably not logical, but I’m suddenly missing Google Reader with proper violence. I’m swamped with nostalgia for that bygone era when things we wanted to share didn’t have to be constrained by character limits or structured into threads; when everyone seemed to be setting up blogs and the internet felt like a never-ending conversation that you could pop in and out of — especially if your own personal internet, made up of the sites you followed, was on Google Reader. It feels as though the good things of the internet may have been relatively harder to find because they were scattered, but they were easier to keep safe.

But the Google Reader is dead and for better or for worse, Twitter (or Facebook/Instagram, if that’s the hellsite of your choice) is what we’ve got at the moment. So that’s where we’ll stay, mostly to hold on to whatever little patch of the virtual space we can claim for dissent.

*It sounds terribly shallow, but the reason I abandoned Mastodon was its incompatibility with GIFs. That and the fact that for the life of me, I can’t remember my password. Sigh.

** Caravan, Kisan Ekta Morcha and quite a few of the withheld accounts were restored at night, around 9pm. I don’t know if all the accounts were restored, but I’m guessing they were. No explanation was given about the restoration, which makes it obvious that this whole exercise had everything to do with harassment and intimidation; and nothing to do with maintaining “public order”.

January 20, 2021

A Culture of Conversation

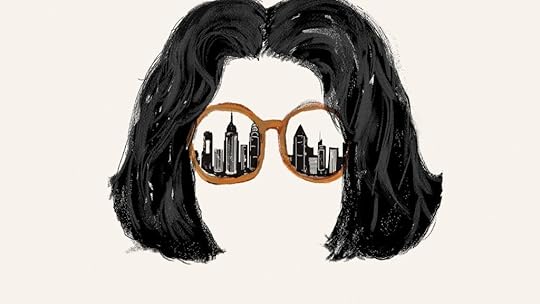

If you replaced her trademark tortoiseshell frames with thick black ones and added a goatee to her face, Fran Lebowitz could be adman, theatre producer and professional talking head Alyque Padamsee. Until she starts talking, that is.

It isn’t only that Lebowitz at 70 comes across as effortlessly witty, unlike Padamsee’s laboured, theatrical flair. Padamsee occupied the spaces he walked into with undimmed confidence. Whether it was on stage, at a party or on a news channel, he radiated privilege and entitlement. Lebowitz, in contrast, is a nervous bundle of energy and mostly combative in Pretend It’s a City, as though she has to fight for her place in the concrete chaos of New York City. She doesn’t. Lebowitz has long been firmly entrenched as NYC’s cultural elite. You don’t call director Martin Scorsese a friend and he doesn’t make one documentary and a seven-part Netflix series with you front and centre if you’re not part of a rather rarefied set. Yet Lebowitz seems to always be on edge, as though she’s told herself that she needs to prove herself with every sentence she speaks; as though she knows she has no business being famous.

Pretend It’s a City is Scorsese and Lebowitz’s love letter to their beloved NYC as well as a portrait of the duo’s friendship. Scorsese presents Lebowitz, a slight figure in real life, towering over a miniature version of the city (it’s the scale model in Queens Museum), like a genteel Godzilla. Instead of rampaging through the city, Lebowitz tiptoes carefully on the fake East River and scrutinises actual pavements for details like plaques and graffiti, keeping an eye and ear out for Scorsese. The meandering conversation with Lebowitz is a masterclass in editing because it sews together fragments from different events. Q and A sessions that followed the screening of Public Speaking (Scorsese’s 2009 documentary featuring Lebowitz); an event in which Lebowitz interviewed the legendary Toni Morrison (they were good friends and Pretend It’s a City is dedicated to her); Lebowitz in conversation with Alec Baldwin, Spike Lee and Olivia Wilde; clips from Lebowitz’s television appearances — all these miraculously come together to become one coherent chat, held together by the love for NYC that Scorsese and Lebowitz share. She is literally a woman in the street who is somehow deeply rooted in the reality of NYC even while living in her own bubble. He’s doing his best to remember and hold on to what he loves in this city that’s always rushing to change. Their camaraderie is rooted in a particular worldview that both Scorsese and Lebowitz identify with NYC — one which is fiercely idiosyncratic, privileges the impractical over the practical, and thrives on eccentricity and wit.

Scorsese opens with a clip of an on-screen orchestra from a vintage Hollywood movie, which serves as a fair warning that what’s coming up is steeped in nostalgia (the same orchestra closes the series too). The series is peppered with clips from old films, which feels fitting given the incredible work Scorsese has done restoring hundreds of films from all over the world. With Pretend It’s a City, he is preserving NYC and its culture in a similar fashion. Scorsese starts off as an off-camera voice in the series and then starts appearing in fragments and flashes, before eventually becoming a fully embodied presence that shares the frame with Lebowitz. Pretend It’s a City is as much about Lebowitz revelling in her New Yorker identity as it is about Scorsese celebrating the things he enjoys — browsing through shelves in a library; listening to stories about volatile artists; discussing old movies; examining how the imagination preserves history. In short: Lebowitz gives him the ultimate gift of a good and profoundly chaotic conversation that hopes to be ongoing and can’t be structured into a Twitter thread.

In Public Speaking, Scorsese had filmed Lebowitz at Waverly Inn, a West Village dining institution that began as a tavern and bordello and after many changes, ended up as a restaurant that is practically a private club. In 2008, about two years after it opened as a restaurant, Waverly Inn’s phone number didn’t work (which meant you couldn’t call to make a reservation) and the menu had said “preview” (as though it was a work in progress). Vanity Fair‘s Graydon Carter owned it and the swishest set dined there. Occasionally, it opened its doors to the public. Waverly Inn now makes me think of Man Wol’s Hotel del Luna, the hotel for ghosts who aren’t ready to move on to the afterlife. It’s as though Scorsese and Lebowitz were haunting Waverly Inn’s dining room, like ghosts unable to give up the idea of a bygone New York City.

For Pretend It’s a City, Scorsese settles Lebowitz down at a table in the Players Club, a private club that was founded in the 1880s (Lebowitz supplies great trivia about the founder of the club) and allowed women to become full members in 1987. Outside its doors is NYC. Step inside, and a doorman takes your coat and walks you back in time. It seems fitting that moments after Lebowitz — a woman and a lesbian — sits down in Players Club, there’s a loud crash as though just her presence had unsettled the institution, which looks like it’s remained the same for 100 years if not more. It’s particularly charming to hear Scorsese cackling with laughter as he listens to Lebowitz in this particular location Club because that simple celebration takes a battering ram to the patriarchal culture in which so many male comics will fall back on hackneyed jabs about women lacking a sense of humour.

Lebowitz doesn’t really say anything scandalous or incendiary in Pretend It’s a City. She’s teeming with opinions and some of these are controversial, like when she says she can separate art from the artist. Occasionally she’ll deliver a pronouncement, like “If you can eat it, it’s not art” (untrue, Fran, but never mind), or a directive, like when she wants you to read physical books rather than e-books (the reason for this seems to be that physical books make it easier for her to see what you’re reading). Entertaining as she is, I doubt anyone can say they learnt much from Pretend It’s a City. It’s not that she lacks insight, but there are times when the series feels indulgent and you can’t help wonder what angularities are being smoothened out by the fact that this series is directed by a friend of hers. A Twitter thread offered a reminder that in the past, Lebowitz has said things that sound myopic and transphobic while talking about the trans pioneer Candy Darling. Lebowitz mentions Candy in Pretend It’s a City too, but with great fondness and respect. I’d like to believe you can’t be friends with someone who is trans and be transphobic at the same time (but humanity has a way of surprising me so who knows). That said, I haven’t seen the documentary mentioned in the thread and just by virtue of Lebowitz being 70 and unfamiliar with the internet, I can believe she may need to update her understanding of gender. Say what you will against social media, but it’s enabled conversations that have gone a very, very long way in educating people on gender normativity and sexuality.

At some point, while watching a grumpy Lebowitz walk around NYC, you may wonder what makes her a “worthy” subject. Lebowitz came to New York City around 1970 after being expelled from high school. She’d work many jobs to earn a living in the city, including being a cab driver and writing columns for Interview, a magazine founded by Andy Warhol. In 1978, her first book, Metropolitan Life, was published. The collection of essays made Lebowitz a New York celebrity, especially after she became a frequent guest on David Letterman’s television show. Her second book Social Studies, another volume of essays, was also a success. The last book Lebowitz published was a children’s book in 1994, with illustrations by Michael Graves. Titled Mr. Chas and Lisa Sue Meet the Pandas, it’s about two children who discover their apartment building in New York is home to two Giant Pandas who have come from China and want to go to Paris.

While her writing brought her some recognition, Lebowitz became famous because of her TV appearances, which is ironic given how mulishly tech-adjacent Lebowitz is. (She owns neither a cellphone nor a computer. She’s never used either a typewriter or a word processor.) People saw and heard Lebowitz on TV and by some alchemy, this led to public speaking engagements, which have since become her livelihood. It’s almost poetic that someone famous for being unimpressed by the contemporary youth has a career that is quintessentially Gen Z. What influencers are now doing (for free) on Instalive, Twitch and other live streaming platforms, Lebowitz has been doing as a paid profession for decades.

Lebowitz has often ranted about the youth in her talks, grumbling about their Teflon-tough self-confidence, which is hilarious because it’s so off the mark. (If there’s one thing for which millennials and Gen Z stand out, it’s their readiness to admit they are damaged, scared and/ or broken.) Every generation has its share of the insecure. The only difference is that each generation has its own particular, acceptable way of articulating pain and hiding insecurities. In Public Speaking, Lebowitz says with all the belligerence of a gladiator, “There are too many books, the books are terrible, and it’s because you have been taught to have self-esteem.” The “you” is interesting because it suggests Lebowitz holds herself apart from the audience, rather than imagining these public speaking events as part of the project of building a community (there’s a clip in Pretend It’s a City in which Morrison and Lebowitz talk about the differences in the way the two women see the reader/ audience). Meanwhile, the crowd roars delightedly and I’m still not sure what they’re responding to when they react with laughter. Does the audience find itself relating to Lebowitz despite her efforts to distance herself from them? Is the audience laughing as a collective at a solitary old woman lashing out (ineffectually) at the young? Is the laughter a manic cover-up of a depressive conviction that an entire generation is unworthy and not as good as the ones in whose footsteps they follow? Is the crowd mocking Lebowitz for complaining about high self-esteem in others when her own was robust enough to claim a spotlight as a public intellectual despite her writing career having floundered?

Ultimately, the reason to watch Pretend It’s a City is that it rejoices in the fine art of rambling conversations. It doesn’t seek to teach because the conversations in the series are premised on the understanding that everyone involved is learned. These are conversations between a voracious reader and a film nerd; between an audience that cherishes a nuanced punchline and a person who went to boxing matches not for the sport (which she doesn’t care for) but to see the fabulous fashion worn by those in attendance. The speakers don’t demand agreement with their points of view. They only assert their right to their own opinions. These are conversations about culture, history, pleasure and love — all topics that are sidelined as unimportant unless they’ve been politicised by someone. This is what makes Pretend It’s a City so precious — it imagines a world in which culture and art matter, not for the politics they espouse, but for their beauty. They’re relevant not because of the battles fought over them but for the ideas they inspire. Especially in a time when so much public discourse is (for good reason) focused on educating the public, Lebowitz and Scorsese offer reminders of what else we could be discussing if we didn’t have to confront multiple apocalypses every other day. If the world wasn’t going to hell, then maybe we could sit back and talk about works of art and the meanings nestled in then. Or maybe it’s because we stopped doing this that the world is going to hell.

January 8, 2021

Crash landing on 2021

We’re barely a week into the new year, but it feels old and the year past already feels distant enough for me to find nothing weird about starting a sentence with “back in December 2020”.

So. Back in December 2020, when I realised that I’d made the most of my insomnia by bingeing on K-dramas over the past three months, I gave myself an end-of-the-year project — write blogs on the K-dramas I had seen. That year ended, a new year has begun and I’ve decided to hell with my grand plans of discussing themes and connections between different K-dramas. I’m already invested up to my eyeballs in three new K-dramas, which means I have Thoughts. Only I can’t write about those until I’ve dealt with the shows I watched in 2020*, which means bloggleneck (blog + bottleneck). It’s all very harrowing.

* Obviously it’s not like I can’t, but chaos and procrastination require organising principles and in my head, the law states that I must clear this 2020 backlog before scribbling about 2021.

* Obviously it’s not like I can’t, but chaos and procrastination require organising principles and in my head, the law states that I must clear this 2020 backlog before scribbling about 2021. So here’s the full list of all the K-dramas I watched last year, from most loved to most meh. Brace thyselves.

heart-flutterers

(aka my favourites)

(contains glorious heroines, beautiful men and ample scope for overthinking)

1. Rookie Historian Goo Hae-Ryung

(written by Kim Ho-Soo; directed by Kang Il-Soo and Han Hyun-Hee)

Take Rapunzel, add a whole lot of court intrigue, set the story in the Joseon period; oh and make Rapunzel an impossibly babyfaced man who is saved by a firecracker of a woman — et voila! It’s Rookie Historian Goo Hae-Ryung. While the writing is fantastic and the show was beautifully produced, arguably its best part is Shin Se-Kyung’s luminous performance as Goo Hae-Ryung. Hae-Ryung is the opposite of an ideal Joseon woman — she dislikes romances, preferring instead non-fiction, science books; she’s outspoken and doesn’t hesitate to stand up to men in power; she wants a career; she’s practically a spinster; and she’ll drink pretty much anyone under the table. Prickly, proud and brighter than sunshine, Shin’s Hae-Ryung is a delight. It helps that she’s surrounded by some wonderful actors and characters, like the other women who have signed up to be the first female officials in the court of an insecure king.

Rookie Historian is a show about new ideas finding their place in history. No wonder then that it begins with the sneaky vehicle of change that is a book. Books, bookshops and writing play key roles in this show, which is just one of the many reasons to love Rookie Historian. In addition to two wonderful and unconventional love stories (one of them between an older woman and a younger man that ends happily but NOT in matrimony despite being set in the 1700s), one strand of story follows a young prince negotiating a way through the pit of vipers that is the court that he’s inherited from his father. Another strand is about a group of young women establishing themselves as professionals, rather than pawns in court politics. In the middle of all this, Rookie Historian manages to explore the idea of freedom of speech and expression; examine what Catholicism and the West have signified for traditional Korean society; and tuck in a sub-plot on variolation and small pox. This show has my heart and I’ve found new things to love each time I’ve re-watched it. Yes, you read that right. I’ve rewatched this 20-episode magnum opus. Thrice.

2. Stranger/ Forest of Secrets 1 & 2

(written by Lee So-Yeon; directed by Ahn Gil-Ho [season 1] and Park Hyun-Suk [season 2])

Early on, we’re told that the hero Shi-Mok has a problem — his brain is too big for his head. It’s almost as though the writer thought, “Autism is so done. What’s a crackerjack of a disorder that seems like a weakness but is sufficiently heroic? … I know! An outsized brain!” It’s absolutely ridiculous and the one part of the show that requires you as an audience member to put your brain aside while watching it.

Get past that little hiccup and the first season of Stranger is a gripping mystery that coils itself around you tighter with every passing minute. Shi-mok (Cho Seung-Woo) is a public prosecutor with a reputation for being difficult to work with and incorruptible. When a fixer who had been hanging out in the prosecutors’ office is found murdered, the case seems straightforward but Shi-Mok spots discrepancies that hint at a bigger problem and a murkier plot. He finds an invaluable partner in Detective Yeo-Jin (Bae Doo-Na), and together, they start unravelling a tangled and bloody network of bribes, power-brokers, and dead bodies. The way the friendship between these two develops is as wonderful as the mystery at the heart of Stranger. This show has excellent writing, superb acting from the entire cast and some of the most fun behind-the-scenes footage (look them up on YouTube) that you’ll ever see. My only real issue is how shoddily the script treated Shin Hye-Soon’s character.

Since the first season was a commercial and critical success, you’d imagine that the writer would give you more of the same in the second season. Think again. Stranger 2 is so different from the first season in both its subject and treatment, it could almost be a standalone. That said, it helps to know the first season because Stranger 2 doesn’t waste time on any backstories and introductions for all the returning characters. Also, if you’ve seen the teamwork and rapport between Shi-Mok and Yeo-Jin in the first season, then the fact that they’re now forced to be adversaries hits you where it hurts.

In season 2, the police and the public prosecution are fighting for power and authority, and it’s an ugly fight because both parties are tainted and vicious. The storytelling isn’t as strong and tight as in the first season and the pacing is definitely more inconsistent, but it also aims higher. Stranger 2 is less action and incident-oriented, focusing instead on the ideals and anxieties that underpin the actions of individuals and the stands taken by institutions. One of its greatest strengths is the character of the police chief Choi-Bit (Jeon Hye-Jin) and her relationship with Yeo-Jin, who looks up to Choi-Bit. If you’re a woman who has worked in a male-dominated field, this strand in Stranger 2 will resonate deeply with you as will the storyline involving the Yeon-Jae (Yoon Se-Ah), the widow of one of the main characters in the first season who in this season is up against her family as she tries to establish herself as a businesswoman. Also, unrelated to the excellent women characters in this show, rarely has a man’s smile been deployed with such tactical precision as Shi-Mok’s in Stranger 2. Off-screen goofball and on-screen ice king, Cho as Shi-Mok is a treasure.

3. Search WWW

(written by Kwon Do-Wun; directed by Jung Ji-Hyun and Kwon Young-Il)

I’ve already gushed about this show here, so I won’t repeat myself. It’s not as though the show is perfect — the second half is definitely loose and less engaging than the first few episodes — but there’s so much to love in Search WWW.

4. Hotel del Luna

(written by Hong Jung-Eun and Hong Mi-Ran; directed by Oh Choong Hwan)

Most K-dramas make me feel hungry — these impossibly thin actors are constantly nibbling on a snack or eating at restaurants that feel like siren songs for foodies — but the kind of snacking Hotel del Luna inspired was at a whole new level. All because of IU’s electric performance as a woman who goes around eating at restaurants that have been visited by a chubby celebrity chef on whom she’s been crushing. For most of the series, the restaurant crawl seems to be a sign of Man-Wol being whimsical and eccentric, but eventually, the Hong sisters tuck in the sweetest, most heart-melting explanation that reveals her to be quite the opposite. I’m now craving japchae just remembering why Man-Wol follows that chef’s train.

Anyway. Man-Wol looks like an ageless sprite but is a 1,000-ish year old undead spirit who runs a hotel for the dead. While the hotel is more fantastical than Hogwarts on the inside, it is also a building in the heart of Seoul and a registered business, which is why it needs a human manager. Enter Chan-Sung, freshly returned from Harvard and general bright spark. When Chan-Sung returns to Korea after years abroad, he thinks he’s going to join a big hotel as a manager and climb the corporate ranks. The last thing he expects is an odd woman giving him the ‘gift’ of being able to see ghosts and telling him he must work for her because of a promise his father made.

In every episode of Hotel del Luna, Chan-Sung learns a little bit more about why Man-Wol has been cursed to be an undead hotelier while sorting out the problems of a freshly-minted ghost. Things start getting a whole lot more complicated when Man-Wol realises there’s a connection between Chan-Sung and her and his presence changes things inside the magical hotel. Man-Wol realises that she may finally be able to leave the earthly plane for the afterlife, which would be good news (after all, she’s been undead for more than 1,000 years), but for the fact that she and Chan-Sung are in love. Through the many ghosts and humans that pass through the hotel, the show talks about love, pride, the importance of attachment as well as letting go, and (I kid you not) Heidegger.