Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 351

March 15, 2016

today is my forty-sixth birthday,

Another birthday party survived [see last year, here]. Saturday night at our usual location, the Carleton Tavern, where I’ve had birthday parties for well over a decade (I think since 2000 or so, most likely). The evening began with Rose and I attempting a dance party (as she does what she calls her “wiggle dance”). There were drinks, cake, lots of friends and family, and much joyous celebration.

Another birthday party survived [see last year, here]. Saturday night at our usual location, the Carleton Tavern, where I’ve had birthday parties for well over a decade (I think since 2000 or so, most likely). The evening began with Rose and I attempting a dance party (as she does what she calls her “wiggle dance”). There were drinks, cake, lots of friends and family, and much joyous celebration. Christine suggests I’m “late forties,” which I completely refuse; mid-forties, please. I don’t even begin that “late” until, what, forty-eight? Bah.

Christine suggests I’m “late forties,” which I completely refuse; mid-forties, please. I don’t even begin that “late” until, what, forty-eight? Bah.Most of my photos from the birthday gathering (which was, itself, magnificent) were terrible, so I’ve pilfered ones Christine took on her phone (the wiggle dance, for example), and others that Stephen Brockwell snapped with his super-camera.

I’ve now been full-time at home with Rose for a year and a half, with our new maternity leave scheduled to begin in another month. Given our Wednesdays at the new Comet Comics in Old Ottawa South, we’ve begun to seek out new options for post-comics muffins, and have found the Tim Hortons nearby to be quite nice. If the weather is good, we simply take the stroller and walk the half-hour. Rose and I stop each way on the bridge to look at the ducks below, collected along the shoreline and ice.

I work my two mornings a week while she is at ‘school,’ and afternoons as she naps (which I’m hoping she continues for a while, given the summer doesn’t have ‘school’ at all; but Christine hopes less nap means more nighttime/morning sleep…). I’ve been attempting to complete my manuscript of short stories [four of which appeared recently in a wee chapbook], especially given the five or six weeks remaining before the birth of our new bundle (Christine’s second; my third). Once the new baby comes, I fully expect a month or three of complete (joyous/exhaustive/hazy/confused) chaos, before things begin to settle down again.

I work my two mornings a week while she is at ‘school,’ and afternoons as she naps (which I’m hoping she continues for a while, given the summer doesn’t have ‘school’ at all; but Christine hopes less nap means more nighttime/morning sleep…). I’ve been attempting to complete my manuscript of short stories [four of which appeared recently in a wee chapbook], especially given the five or six weeks remaining before the birth of our new bundle (Christine’s second; my third). Once the new baby comes, I fully expect a month or three of complete (joyous/exhaustive/hazy/confused) chaos, before things begin to settle down again.Birth mother: two years-plus since we connected, communication occurs, albeit intermittently. She hints, she responds. She plays her cards incredibly close. But she does respond. This, I know, is good. Is, for now, good enough.

My Patreon page slowly sees attention, in dribs and drabs. I’ve even composed a small mound of blog posts on my patron-only blog, which, for some reason, given the dozen or so folk invited to read, almost no-one actually has. There is something oddly gratifying about writing into a blog that I know no one is actually reading. Does that even make sense? (Probably not.)

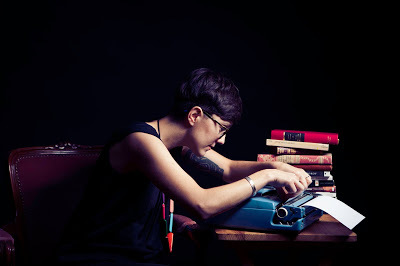

[photo credit: Stephen Brockwell] As part of a growing poetry manuscript titled “Cervantes’ bones” begun just over a year ago [other poems from the same manuscript-in-progress exist here and here and here], I’ve been well over a year poking at a suite of fragments underneath the title “Sex at Forty-five,” my further offering into the “Sex at” sequence begun way back in Prince George, British Columbia in the late 1970s [see my 2015 ‘commentary’ over at Jacket2 on the series, and an earlydraft of my “Sex at Forty-five,” here]. Given the year named is finally over (it’s okay, as Elvis Costello didn’t actually release “45” until he was actually forty-seven years old), I’ve been the past few weeks digging back into the five-page poem, and have found myself unsatisfied. As a result, I’ve done what I haven’t before: I erased the whole damned thing (okay, not erased erased, but set aside with a new file name, leaving my “Sex at Forty-five” file a blank page), and attempted to start again from scratch.

[photo credit: Stephen Brockwell] As part of a growing poetry manuscript titled “Cervantes’ bones” begun just over a year ago [other poems from the same manuscript-in-progress exist here and here and here], I’ve been well over a year poking at a suite of fragments underneath the title “Sex at Forty-five,” my further offering into the “Sex at” sequence begun way back in Prince George, British Columbia in the late 1970s [see my 2015 ‘commentary’ over at Jacket2 on the series, and an earlydraft of my “Sex at Forty-five,” here]. Given the year named is finally over (it’s okay, as Elvis Costello didn’t actually release “45” until he was actually forty-seven years old), I’ve been the past few weeks digging back into the five-page poem, and have found myself unsatisfied. As a result, I’ve done what I haven’t before: I erased the whole damned thing (okay, not erased erased, but set aside with a new file name, leaving my “Sex at Forty-five” file a blank page), and attempted to start again from scratch.Over twenty-five years-plus of daily practice, my poetry composition process has become slower, and far more methodical. In my twenties and into my thirties, I would start writing a poem at the beginning, and write chronologically towards an end I rushed toward never finding, Robert Kroetsch’s “delay, delay, delay” as a mantra throughout. Now my poems tend to begin somewhere in the middle and expand outwards. I add words and phrases in the middle of lines; I introduce new line-breaks, stanza breaks and move lines and stanzas around. The poem is less chronological than a series of mixes, stirred and constantly re-set.

[photo credit: Stephen Brockwell] Really, the current dissatisfaction and erasure of what I’d composed up to this point follows a trajectory suggested in my Jacket2 piece; I am getting better at tossing lines, stanzas and entire poems. I am getting better, finally (one might say), at returning to pull apart what simply isn’t (yet) enough.

[photo credit: Stephen Brockwell] Really, the current dissatisfaction and erasure of what I’d composed up to this point follows a trajectory suggested in my Jacket2 piece; I am getting better at tossing lines, stanzas and entire poems. I am getting better, finally (one might say), at returning to pull apart what simply isn’t (yet) enough. Begin again. Finnegan.

Retreat, into the body. Lexical. The back of my scaled tongue. Whatyou seek of. Formulated.

Interrupted, rupture.

The nightly juke-box of the baby’s breathing, intermittent cries. Wehold collective breath.

Each silence an opportunity.

The body, like a theatre. Translated. Distance, is a chorus.

Earth and sky. A single hair that drips.

Published on March 15, 2016 05:31

March 14, 2016

Inger Wold Lund, Leaving Leaving Behind Behind

Last summer. At the border between two countries.

It was hot. The police wore white hats. In white leather belts they carried guns. The guns were attached to their belts with white cords, curled up like the cords of old telephones. I thought of whom I would like to kill if given the chance. Of people on my phone list: One. Maybe two.

Berlin-based visual artist and writer Inger Wold Lund’s first English-language publication is the small chapbook Leaving Leaving Behind Behind (Brooklyn NY: Ugly Duckling Press, 2015), an absolutely incredible title I’m delighted to have discovered in a pile of books resting on one side of my little office. Listed in the Ugly Duckling Presse catalogue under both poetry and fiction, the delightfully subtle and deceptively straightforward prose-pieces in Leaving Leaving Behind Behind examine the remarkable within the mundane, and are easily comparable to some of the best that the border on either side of “postcard fiction” and the prose poem have to offer, whether the works of Lydia Davis, Sarah Manguso’s Hard to Admit and Harder to Escape (McSweeney’s, 2007) or Czeslaw Milosz’ Roadside Dog (1998). Certainly, the issue of genre in her work is fluid, and one that might seem as irrelevant as it is essential. In an interview posted at the Ugly Duckling Presse tumbler(a frustratingly short interview, I might add), she responds to the question “What is poetry?” with “I am not very concerned with genres, but I was told that as a rule of thumb one can recognize poetry by the ragged right margin.”

Yesterday. In an email.

He wrote me that a group of kids had biked past him when he was sitting outside the house where he lived when he himself was a kid. As they passed, one of them turned around and screamed.

I am not with them. I am not with them.

In a short review posted at Rain Taxi, Tova Gannana opens with: “Inger Wold Lund, a Norwegian living in Berlin, wrote Leaving Leaving Behind Behind in English. A book of poems in the form of a day-book or a day-book written to read as poetry, it offers a duality, a doubleness of language.” The day book aspect of the volume is intriguing, as Lund composes extremely dense sketches of domestic life, and domestic patter, yet reveling in a kind of magical quality throughout. Her titles, each a double of sorts, sets the immediate scene of the poem—from “Last summer. In an email.” to “Many years ago. At my mother’s place.” and “Some years ago. In a kitchen.” Occasionally, either a physical or temporal location might be repeated, which help tie the collection of seemingly stand-alone pieces together into a single, and quite incredible, work. One notes as well that all the temporal locations are in the past, and never present, which make the present, in its own way, curiously absent, but for the sake of these short missives (which, themselves, appear to be entirely in the present). Is it the distance that allows the narrator such clarity? Is the present sense of the past the only version that ever exists?

In a short review posted at Rain Taxi, Tova Gannana opens with: “Inger Wold Lund, a Norwegian living in Berlin, wrote Leaving Leaving Behind Behind in English. A book of poems in the form of a day-book or a day-book written to read as poetry, it offers a duality, a doubleness of language.” The day book aspect of the volume is intriguing, as Lund composes extremely dense sketches of domestic life, and domestic patter, yet reveling in a kind of magical quality throughout. Her titles, each a double of sorts, sets the immediate scene of the poem—from “Last summer. In an email.” to “Many years ago. At my mother’s place.” and “Some years ago. In a kitchen.” Occasionally, either a physical or temporal location might be repeated, which help tie the collection of seemingly stand-alone pieces together into a single, and quite incredible, work. One notes as well that all the temporal locations are in the past, and never present, which make the present, in its own way, curiously absent, but for the sake of these short missives (which, themselves, appear to be entirely in the present). Is it the distance that allows the narrator such clarity? Is the present sense of the past the only version that ever exists?Frustratingly, the book is already listed as out of stock. Will they make more? Is another larger volume, perhaps, in the works?

Half a year ago. At a store.

The lady in the store told me the marks on the pumpkin I had chosen had appeared during a hailstorm earlier in the fall. Then she asked if I remembered the storm. I said no.

Published on March 14, 2016 05:31

March 13, 2016

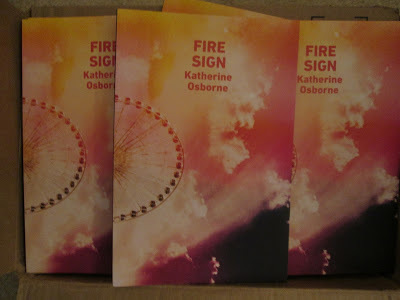

Queen Mob's Teahouse: Niina Pollari interviews Katherine Osborne

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the sixth interview is now online: an interview with Katherine Osborne, conducted by Niina Pollari. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview I conducted with Dale Smith, on the Slow Poetry in America Newsletter, and an interview with Ann Tweedy conducted by Mary Kasimor.

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the sixth interview is now online: an interview with Katherine Osborne, conducted by Niina Pollari. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview I conducted with Dale Smith, on the Slow Poetry in America Newsletter, and an interview with Ann Tweedy conducted by Mary Kasimor.Further interviews I've conducted myself over at Queen Mob's Teahouse include conversations with Allison Green, Andy Weaver, N.W Lea and Rachel Loden.

If you are interested in sending a pitch for an interview my way, check out my "about submissions" write-up at Queen Mob's ; you can contact me via rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com

Published on March 13, 2016 05:31

March 12, 2016

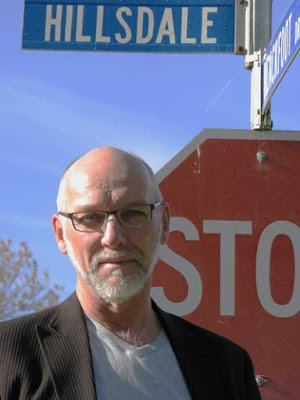

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Gerald Hill

Gerald Hill [photo credit: Mark Anderson] has published six poetry collections — two of which won Saskatchewan Book Awards for Poetry. His latest collection,

Hillsdale Book

, came out with NeWest Press in April, 2015. Two sub-sets of that book were published in 2012:

Hillsdale, a Map

, produced with designer Jared Carlson, and

Streetpieces

, a chapbook produced by David Zieroth at The Alfred Gustav Press in Vancouver. Also in 2015, Hill published

A Round for Fifty Years: A History of Regina's Globe Theatre

with Coteau Books. Widely published in literary magazines and online journals, active as both organizer of and participant in workshops and readings, conferences and courses, and winner of Second Prize in the 2011 CBC Literary Awards, Gerald Hill is newly retired from his career teaching English and Creative Writing at Luther College at the University of Regina. In the fall of 2015 he was Doris McCarthy Artist-in-Residence at Fool's Paradise in Toronto.

Gerald Hill [photo credit: Mark Anderson] has published six poetry collections — two of which won Saskatchewan Book Awards for Poetry. His latest collection,

Hillsdale Book

, came out with NeWest Press in April, 2015. Two sub-sets of that book were published in 2012:

Hillsdale, a Map

, produced with designer Jared Carlson, and

Streetpieces

, a chapbook produced by David Zieroth at The Alfred Gustav Press in Vancouver. Also in 2015, Hill published

A Round for Fifty Years: A History of Regina's Globe Theatre

with Coteau Books. Widely published in literary magazines and online journals, active as both organizer of and participant in workshops and readings, conferences and courses, and winner of Second Prize in the 2011 CBC Literary Awards, Gerald Hill is newly retired from his career teaching English and Creative Writing at Luther College at the University of Regina. In the fall of 2015 he was Doris McCarthy Artist-in-Residence at Fool's Paradise in Toronto.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When good things happen, I nod and say that’s just the way the universe is supposed to work. No big deal. That’s how I felt when that first book came out (in 1985 from Thistledown). This theory was tested in the 16 years before I published my second book ( The Man From Saskatchewan , Coteau, 2001)—years spent at grad school, raising kids, recovering from a broken marriage, with most of my writing done in summers at Emma Lake, Sask. That first collection was very much a collection of lyric poems. Now I write books, not poems. It’s all about the book concept, with individual pieces serving as just that, individual pieces that need not produce a well-wrought urn, say, on their own. It’s a longpoem approach very much in keeping with my first teacher, Fred Wah, at David Thompson University Centre in Nelson, B.C., 1981-82. I’ve always said, though, that I’m grateful for the teaching of Fred and Tom Wayman and Dave McFadden at DTUC and see my own work since as essential a blend of those three writers’ approaches.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

We produced work in all genres at DTUC. The poetry emphasis for me may have been an echo of my father, a Sask schoolteacher, who often recited poetry to his kids as we were growing up. He’d had an old-school education that involved, apparently, much memorizing and oral recitation of poetry. Or the poetry thing derives from those teachers I mentioned, who demonstrated that, all in all, anything was possible with poetry.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

All of these things vary. I’ve never had a problem coming up with something to write. I’m one of those who believes that if you keep the daily process going, the larger project will reveal itself, as if I’ve been working toward it all the time even before I knew it. I save hard copy drafts now, with one eye on the archive. (URegina holds the Gerald Hill papers, such as they are.) But yes, initial entries come relatively quickly; I know enough, I think, just to get stuff down knowing I’ll work on them later, a slower process. Along these lines, I really like Michael Ondaatje’s note, in his Afterword (or Foreword is it?) to the newer edition of The Collected Works of Billy the Kid , about just writing ahead, not looking back. For a long time before you start revising.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I rarely assume that the piece I’m working on is discrete unto itself. It’s always a page or fragment of the larger whole. As poems are not about closing in on themselves but gesturing open to the larger constellation.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy readings and think I do them well. I like that preparation for public performance brings a different set of editing principles into play. What I don’t like so much is the sense that getting ready for a reading necessitates getting out of the daily flow of exploration of new work.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

One way of addressing those questions is to suggest that what I do is deal with/ explore/ fool around with/ dodge the “I”. As a good subject of postmodern and post-structuralist literary theory 25 years ago, I learned—thank God or somebody—to mistrust the authority of that pronoun. The lyric poet is locked into that authority. A poet who works in more open forms—which is where I place myself—will undercut the “I” much more, playing with what we see to be its inherent slipperiness. As a teacher (a job from which I retired just last year) I tried to deny my students the apparatus of nailing down what a poem supposedly means. It was about submitting and allowing the poems contradictory effects to work on us, rather than us on them. The general issue here is openness, multiplicity, polyphony, etc.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Beyond my largely ceremonial (but I’m working on it) role as poet laureate of Saskatchewan intending (without much budget) to spread the word of poetry in the larger society, I don’t think the writer has any role in larger culture, necessarily. A writer’s duty is first and last to his/her work.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ve had good luck with my editors (incl. Dennis Cooley, Jeanette Lynes, Douglas Barbour, Don Kerr) for the most part. In my experience, they seem less interested in what I imagine the larger theoretical concepts of the book to be, preferring to focus on how bits of text work. I have noticed that I enter an editor-writer relationship warily.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

What comes to mind right now is Ondaatje from In the Skin of The Lion . Trust me, there is order here. Very faint, very human. That’s a paraphrase of what the narrator says at one point—true of the main character and the text in which he appears. So, forget what you think you’re doing. Forget meaning. Forget overly elaborative linking passages. Downplay endings. Trust. You’ll figure out and get to where you’re going sooner or later.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Easy. Both are wide open.

My blog entries over the years (http://poetshoes.blogspot.ca/) have often served as versions of poems, and vice versa.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

The day begins with sudoku and kenken puzzles. Beyond that it depends on how my body is feeling today, what errands I have to do, what deadlines I’m facing. If I’m generating new material, I’m probably walking and sitting down someplace with my notebook or tablet. It becomes an intense paying of attention to the specifics of where I am mixed, as always, with whatever comes up from inside. Generally, mornings for new work. Afternoon or evening for revision work.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

To the next page. It’s always a way out. Or to my library, reading my way out.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

If I ever get my nose on a palm springs cake, that will do it. Caragana hedge and lilac. Fresh-baked bread. Model glue (I specialized in WWI aircraft).

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Absolutely. We can learn from artists and works in any discipline. I learned many years ago at Emma Lake that painterly concerns—the continuum of abstraction to representation, for instance—were also writerly concerns. Their solutions might be ours. Dance, theatre, visual art, music—any discipline that calls for and evokes the great highs and lows of human existence and explores its generic protocols—will be instructive for writers.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I got rid of hundreds of books in the last couple of years. I kept about 40 in my tiny apartment: Anne Carson, Daphne Marlatt, Charles Olson, Lorca, Borges, Kroetsch, Calvino, Pessoa, Basho. Saramago, W.C.Williams, Wah, Stevens, Cortázar, Kerouac (my first literary hero, if I don’t get a chance to say this somewhere else), Salinger, Carver, Simic, Ondaatje, bp.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Live for a year in southern Spain. Win the G-G, why not. See my work, and that of many other writers we could name, get thoughtful critical attention. Create an endowment that would fund a fabulous writer’s retreat.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I was a teacher off and on, here and there, for 40 years. A good one, for most students. An effective writing and literature teacher. For a while I wanted to be a sportswriter. Now that I’m older, I’d love to run—or create, get someone good to run it—a pub that showed what good service means.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Probably had something to do with my dad’s books and poetry recitations. And being read to. Over the years, however, what has made me write is the sense that it is as a writer that I am most Gerry Hill.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

They happen to be the same. Brooklyn . In both cases, I marvel at how the story is told. And the movie, of course, has what’s-her-name—the Irish/American actress nominated for the Oscar. She’s fabulous. I loved Fifteen Dogs as well. Poetry I raid, not read—dipping in and out of Carson or Lorca or . . .

20 - What are you currently working on?

I have a book, poems, begun last summer. Dogabout, I call it. Its central character is a man named dog (lower case) though I’m running into so many dogs in literature these days that I might have to come up with something else. I know I’ve got an idea that’s good when it gives me everything I want in writing, as this one does. Doesn’t matter where I am. In January I sent every page of Dogabout—now in its 8th draft—to various journals. I sent another manuscript to a publisher in January also. And I have another one that’s been knocked back a couple of times.

[Gerald Hill reads in Ottawa on Tuesday, March 15 as part of the opening night of VERSeFest 2016]

12 or 20 (second series) questions

Published on March 12, 2016 05:31

March 11, 2016

U of Alberta writers-in-residence interviews: Trevor Ferguson (1992)

For the sake of the fortieth anniversary of the writer-in-residence program (the longest lasting of its kind in Canada) at the University of Alberta, I have taken it upon myself to interview as many former University of Alberta writers-in-residence as possible [see the ongoing list of writers here]. See the link to the entire series of interviews (updating weekly) here.

Trevor Ferguson

(a.k.a. John Farrow) is the author of eleven novels and four produced plays. His crime novels, City of Ice and Ice Lake, under the name John Farrow, were published in major markets around the world and reissued in 2011 by HarperCollins. Booklist praised the Farrow series as the best of our time, while Die Zeit in Germany called it the best in history. River City, which covers over 450 years of Montreal history written as a crime novel, the third in the Farrow series, was released by HarperCollins in 2011 (pb 2012) to impressive critical success. His literary novels, such as Onyx John, The Kinkajou, The True Life Adventures of Sparrow Drinkwater and The Fire Line, enjoyed dazzling critical acclaim. His most recent literary novel is The River Burns (2014, pb 2015, Simon & Schuster). The Timekeeper (1995, HarperCollins) won the Hugh McLennan Prize for Literature and was produced as a feature film. One of his plays, Long, Long, Short, Long received an audience of over 22,000 in its second run, while another, Zarathustra Said Some Things, No? enjoyed a stupendous critical reception Off-Broadway. A new trilogy in his crime series (as John Farrow) is underway, having begun with

The Storm Murders

(May, 2015), to be followed by Seven Days Dead (May, 2016) and The Talisman Quarry (2017), all published by Minotaur/St. Martin’s in New York. He presently is writing the next Farrow novel and living in Hudson, Quebec.

Trevor Ferguson

(a.k.a. John Farrow) is the author of eleven novels and four produced plays. His crime novels, City of Ice and Ice Lake, under the name John Farrow, were published in major markets around the world and reissued in 2011 by HarperCollins. Booklist praised the Farrow series as the best of our time, while Die Zeit in Germany called it the best in history. River City, which covers over 450 years of Montreal history written as a crime novel, the third in the Farrow series, was released by HarperCollins in 2011 (pb 2012) to impressive critical success. His literary novels, such as Onyx John, The Kinkajou, The True Life Adventures of Sparrow Drinkwater and The Fire Line, enjoyed dazzling critical acclaim. His most recent literary novel is The River Burns (2014, pb 2015, Simon & Schuster). The Timekeeper (1995, HarperCollins) won the Hugh McLennan Prize for Literature and was produced as a feature film. One of his plays, Long, Long, Short, Long received an audience of over 22,000 in its second run, while another, Zarathustra Said Some Things, No? enjoyed a stupendous critical reception Off-Broadway. A new trilogy in his crime series (as John Farrow) is underway, having begun with

The Storm Murders

(May, 2015), to be followed by Seven Days Dead (May, 2016) and The Talisman Quarry (2017), all published by Minotaur/St. Martin’s in New York. He presently is writing the next Farrow novel and living in Hudson, Quebec.

He was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the winter 1992 academic term.

Q: When you began your residency, you’d already published three novels. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: The opportunity was a game-changer in both expected and unexpected ways. My fourth novel was finished, and while in residence I was able to complete the edit of that book, as I had hoped. I was also moving my fiction in a fundamentally different direction back then. The Fire Line, written in Edmonton, was a difficult project in that its diction and accouterments, momentum and content were in sharp contrast from what I had been doing. That drastic a shift always takes time and concentration, which were afforded me by the residency.

My stint in Alberta helped in other ways though. It allowed me to get my feet wet with respect to teaching and the academic environment, having never been a university student myself. That led to teaching Creative Writing on a part time basis after that up until this year. I would not have been permitted through the door at Concordia University without the U. of A. experience. Obviously, this became a huge, and as I say, unexpected, benefit, which allowed my career as a writer to continue, as well as introducing me to a secondary career which I have much enjoyed.

Also, in Edmonton, my wife and I lived in an unattached house and not an apartment for the first time in our lives. We enjoyed that aspect. Returning home, we went out and bought a house. Without the Edmonton experience, that may never have happened. So that fundamentally changed my life as well.

Q: Given the fact that you aren’t an Alberta writer, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while in Edmonton? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: I was writing a novel at the time (The Fire Line) that is set in northern B.C., and the book that was to follow (The Timekeeper) starts out in northern Alberta and extends into the Northwest Territories (called that in the book’s day). Quite possibly, being back in Alberta instigated the latter. The novel derived from my experience as a runaway in my mid-teens, so it was good to be back for a return visit and under much improved circumstances. I had, in fact, committed my life to writing during that earlier time so enjoyed noting the improvement in my fortunes (“The last time I was in this town I was starving”). So yes, my many drives across the countryside, no longer penniless and desperate, served to both adjust and deepen my appreciation of the prairies and moved my fiction back west for a time.

Tom Pow was over from Scotland then on a residency exchange, and Greg Hollingshead was overseeing the program, and we formed something of a merry band. Greg made a point of connecting me to the broader community in Edmonton, particularly, so I had many good times among other writers, both informally and at events. I recall having the whole faculty (it seemed, anyway) out to a reading and talk I gave, something that doesn’t happen too often elsewhere. Normally, only a grudging few show up. Mind you, I do recall one faculty member expressing disappointment that I was too well behaved for a writer, neither a dipsomaniac nor a philanderer, as he preferred his writers to enliven the university environment with a dash of scandal. I pointed out to him that living as an organ-grinder’s monkey loses its charm soon enough.

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Was it an opportunity to hunker down and focus, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: My work was undergoing what felt like a polar shift, which it has the habit of doing every dozen years or so. So urban, contemporary, complex, sprawling family sagas were giving way to quasi-folkloric, wilderness, male-centric and violent tales of the Canadian north. This meant, on this occasion, a change in how the language was being deployed, new rhythms, a new sound, the exploration of a different diction, as well as a shift in how the stories evolved—toward tighter, more compact, more driven narratives. As a novelist, hunkering down is perpetual, that never changes, but I think the abrupt alteration to daily routines—the familiar transplanted by the fresh—was undoubtedly beneficial in aiding my headspace to welcome and adjust to the change in direction.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? Were there any encounters that stood out?

A: One of the beauties of the residency for me had to do with the variety of work that came across the transom, and manuscripts arrived weekly, which dovetailed with the variety of the encounters. Older folks and quite young. Avid readers and writers were juxtaposed with those dipping their toes in their creative waters for the first time. I met folks in my office and off-campus, as well, whatever worked best. Quite a few family histories appeared, many interesting, although the form rarely finds a home. One gentlemen I visited was a quadriplegic, and therefore confined to his home and subject to continuous care. Writing was critical for him as an emotional lifeline. I taught students in other English classes, including a post-grad group at one point where we got into a hot discussion on the nature of plot. During a break I rapidly wrote a position paper in bullet-poem form (a new genre) that I’ve used in my own classes ever since. Another class was so early in the morning I’m really not sure that anyone could be accused of being wide awake at the outset, but we had a few laughs before we were done. I worked very extensively on a novel with one philosophy grad, no longer a student at the time, a man in his thirties, and I’m not sure that that book found the light of day, although I traced it’s progress, or its lack, for years after the residency had ended. I thought it was a good novel and regret that it was never published, to my knowledge. A student who did fulfill his considerable promise, with whom I worked on a collection of stories that would be published, was Curtis Gillespie, who, of course, became a Writer-in-Residence at the university himself one day.

Trevor Ferguson

(a.k.a. John Farrow) is the author of eleven novels and four produced plays. His crime novels, City of Ice and Ice Lake, under the name John Farrow, were published in major markets around the world and reissued in 2011 by HarperCollins. Booklist praised the Farrow series as the best of our time, while Die Zeit in Germany called it the best in history. River City, which covers over 450 years of Montreal history written as a crime novel, the third in the Farrow series, was released by HarperCollins in 2011 (pb 2012) to impressive critical success. His literary novels, such as Onyx John, The Kinkajou, The True Life Adventures of Sparrow Drinkwater and The Fire Line, enjoyed dazzling critical acclaim. His most recent literary novel is The River Burns (2014, pb 2015, Simon & Schuster). The Timekeeper (1995, HarperCollins) won the Hugh McLennan Prize for Literature and was produced as a feature film. One of his plays, Long, Long, Short, Long received an audience of over 22,000 in its second run, while another, Zarathustra Said Some Things, No? enjoyed a stupendous critical reception Off-Broadway. A new trilogy in his crime series (as John Farrow) is underway, having begun with

The Storm Murders

(May, 2015), to be followed by Seven Days Dead (May, 2016) and The Talisman Quarry (2017), all published by Minotaur/St. Martin’s in New York. He presently is writing the next Farrow novel and living in Hudson, Quebec.

Trevor Ferguson

(a.k.a. John Farrow) is the author of eleven novels and four produced plays. His crime novels, City of Ice and Ice Lake, under the name John Farrow, were published in major markets around the world and reissued in 2011 by HarperCollins. Booklist praised the Farrow series as the best of our time, while Die Zeit in Germany called it the best in history. River City, which covers over 450 years of Montreal history written as a crime novel, the third in the Farrow series, was released by HarperCollins in 2011 (pb 2012) to impressive critical success. His literary novels, such as Onyx John, The Kinkajou, The True Life Adventures of Sparrow Drinkwater and The Fire Line, enjoyed dazzling critical acclaim. His most recent literary novel is The River Burns (2014, pb 2015, Simon & Schuster). The Timekeeper (1995, HarperCollins) won the Hugh McLennan Prize for Literature and was produced as a feature film. One of his plays, Long, Long, Short, Long received an audience of over 22,000 in its second run, while another, Zarathustra Said Some Things, No? enjoyed a stupendous critical reception Off-Broadway. A new trilogy in his crime series (as John Farrow) is underway, having begun with

The Storm Murders

(May, 2015), to be followed by Seven Days Dead (May, 2016) and The Talisman Quarry (2017), all published by Minotaur/St. Martin’s in New York. He presently is writing the next Farrow novel and living in Hudson, Quebec.He was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the winter 1992 academic term.

Q: When you began your residency, you’d already published three novels. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: The opportunity was a game-changer in both expected and unexpected ways. My fourth novel was finished, and while in residence I was able to complete the edit of that book, as I had hoped. I was also moving my fiction in a fundamentally different direction back then. The Fire Line, written in Edmonton, was a difficult project in that its diction and accouterments, momentum and content were in sharp contrast from what I had been doing. That drastic a shift always takes time and concentration, which were afforded me by the residency.

My stint in Alberta helped in other ways though. It allowed me to get my feet wet with respect to teaching and the academic environment, having never been a university student myself. That led to teaching Creative Writing on a part time basis after that up until this year. I would not have been permitted through the door at Concordia University without the U. of A. experience. Obviously, this became a huge, and as I say, unexpected, benefit, which allowed my career as a writer to continue, as well as introducing me to a secondary career which I have much enjoyed.

Also, in Edmonton, my wife and I lived in an unattached house and not an apartment for the first time in our lives. We enjoyed that aspect. Returning home, we went out and bought a house. Without the Edmonton experience, that may never have happened. So that fundamentally changed my life as well.

Q: Given the fact that you aren’t an Alberta writer, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while in Edmonton? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: I was writing a novel at the time (The Fire Line) that is set in northern B.C., and the book that was to follow (The Timekeeper) starts out in northern Alberta and extends into the Northwest Territories (called that in the book’s day). Quite possibly, being back in Alberta instigated the latter. The novel derived from my experience as a runaway in my mid-teens, so it was good to be back for a return visit and under much improved circumstances. I had, in fact, committed my life to writing during that earlier time so enjoyed noting the improvement in my fortunes (“The last time I was in this town I was starving”). So yes, my many drives across the countryside, no longer penniless and desperate, served to both adjust and deepen my appreciation of the prairies and moved my fiction back west for a time.

Tom Pow was over from Scotland then on a residency exchange, and Greg Hollingshead was overseeing the program, and we formed something of a merry band. Greg made a point of connecting me to the broader community in Edmonton, particularly, so I had many good times among other writers, both informally and at events. I recall having the whole faculty (it seemed, anyway) out to a reading and talk I gave, something that doesn’t happen too often elsewhere. Normally, only a grudging few show up. Mind you, I do recall one faculty member expressing disappointment that I was too well behaved for a writer, neither a dipsomaniac nor a philanderer, as he preferred his writers to enliven the university environment with a dash of scandal. I pointed out to him that living as an organ-grinder’s monkey loses its charm soon enough.

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Was it an opportunity to hunker down and focus, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: My work was undergoing what felt like a polar shift, which it has the habit of doing every dozen years or so. So urban, contemporary, complex, sprawling family sagas were giving way to quasi-folkloric, wilderness, male-centric and violent tales of the Canadian north. This meant, on this occasion, a change in how the language was being deployed, new rhythms, a new sound, the exploration of a different diction, as well as a shift in how the stories evolved—toward tighter, more compact, more driven narratives. As a novelist, hunkering down is perpetual, that never changes, but I think the abrupt alteration to daily routines—the familiar transplanted by the fresh—was undoubtedly beneficial in aiding my headspace to welcome and adjust to the change in direction.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? Were there any encounters that stood out?

A: One of the beauties of the residency for me had to do with the variety of work that came across the transom, and manuscripts arrived weekly, which dovetailed with the variety of the encounters. Older folks and quite young. Avid readers and writers were juxtaposed with those dipping their toes in their creative waters for the first time. I met folks in my office and off-campus, as well, whatever worked best. Quite a few family histories appeared, many interesting, although the form rarely finds a home. One gentlemen I visited was a quadriplegic, and therefore confined to his home and subject to continuous care. Writing was critical for him as an emotional lifeline. I taught students in other English classes, including a post-grad group at one point where we got into a hot discussion on the nature of plot. During a break I rapidly wrote a position paper in bullet-poem form (a new genre) that I’ve used in my own classes ever since. Another class was so early in the morning I’m really not sure that anyone could be accused of being wide awake at the outset, but we had a few laughs before we were done. I worked very extensively on a novel with one philosophy grad, no longer a student at the time, a man in his thirties, and I’m not sure that that book found the light of day, although I traced it’s progress, or its lack, for years after the residency had ended. I thought it was a good novel and regret that it was never published, to my knowledge. A student who did fulfill his considerable promise, with whom I worked on a collection of stories that would be published, was Curtis Gillespie, who, of course, became a Writer-in-Residence at the university himself one day.

Published on March 11, 2016 05:31

March 10, 2016

March 9, 2016

D.G. Jones (January 1, 1929 - March 6, 2016)

The poet, editor and translator

D.G. (Douglas Gordon) Jones

has died. A resident of Quebec’s eastern townships, he was one of the few English-language poets of his generation visibly influenced by some of the Quebec poets that came before him, notably the late Anne Hebert, and more recently, influenced by more contemporary poets such as Steve McCaffery, Erin Moure and Stephanie Bolster, making him one of the rare Canadian poets that straddled with ease the line between modernism and post-modernism.

The poet, editor and translator

D.G. (Douglas Gordon) Jones

has died. A resident of Quebec’s eastern townships, he was one of the few English-language poets of his generation visibly influenced by some of the Quebec poets that came before him, notably the late Anne Hebert, and more recently, influenced by more contemporary poets such as Steve McCaffery, Erin Moure and Stephanie Bolster, making him one of the rare Canadian poets that straddled with ease the line between modernism and post-modernism.The author of the selected/collected poems The Stream Exposed with All its Stones (Montreal QC: Vehicule Press/Signal Editions, 2010) [see my review of such here], his earlier collections include Frost on the Sun (Contact Press, 1957), The Sun is Axeman (University of Toronto Press, 1961), Phrases From Orpheus(Oxford University Press, 1967), the Governor General’s Award-winning Under the Thunder the Flowers Light up the Earth (Coach House Press, 1977), A Throw of Particles (General Publishing, 1983), Balthazar and Other Poems (Coach House, 1988), The Floating Garden (Coach House, 1995), Wild Asterisks in Cloud (Empyreal Press, 1997) and Grounding Sight (Empyreal Press, 1999). An ‘essential poems’ volume has been in the works for some time , edited by Jim Johnstone for The Porcupine’s Quill, Inc.

See brief biographies for Jones at The Canadian Encyclopedia and Wikipedia . In 2007, he had a short selection of poems appear online at Jacket Magazine .

Donald Winkler (who also provided the photo, above), via facebook, provided this note received via the Translator’s Association:

The distinguished poet, D. G. Jones died peacefully on March 6th, 2016 after a short bout with pneumonia. A University of Sherbrooke professor emeritus, he was also a literary critic and translator. Twice, he received a Governor General's literary award and in 2008, he was made an “Officer of the Order of Canada” for his contributions to Canadian Literature.

He is survived by his wife Monique, his four children Stephen, Skyler, Tory and North, his stepson Nicolas, and his ten grandchildren. A private funeral service will be held.

In his latter years, Mr. Jones became a prolific and passionate computer artist, generating compelling works that were a unique combination of his artistic vision and poetry. This summer his family is planning a retrospective of his computer art in his beloved town of North Hatley, Quebec.

In his memory, contributions to the North Hatley Library would be appreciated (165 Main Street, North Hatley, QC, JOB 2C0).

His work has been a big influence on mine over the years, specifically my paper hotel (Broken Jaw Press, 2002), which included many of Jones’ cadences, predominantly lifted and adapted from my increasingly-tattered copy of Under the Thunder the Flowers Light up the Earth; a book that accompanied me on at least one if not two reading tours.

for cybele creery & jonathon wilcke (after jones

one mans apartment is anothershome, we live in the house, not the hallway, the neighbourtells her two young girls

a calendar is not a chessboard, a countrynot a destination in itself

some say, or admit, its the choicewe lack

& whether sound has a colour,or music, a presentable shape, how the text& picture, overlay

blesst w/ a good ear can still be guidedby voices

pornographers & poets enjoylarge views

Later on, I composed a short piece triggered by his admission that he wasn’t going to attempt to write again until he’d prepared for the winter, directly lifting a line from one of his short letters, a poem that fell into my poetry collection name , an errant (Stride, 2006):

for doug jones

the poems will come, he says, oncethe wood gets cut

he captures the hard, thinenterprise & leansby the backdoor

when the trees look like bones

a seasonal thing, what pertains to the breath

not an accident of birth

once it can be seen, it canfinally be transcribed

I had been fortunate enough to produce a small chapbook of his poetry, standard pose (above/ground press, 2002), a chapbook we reprinted in Ground rules: the best of the second decade of above/ground press 2003-2013 (Chaudiere Books, 2013). Given he’d been sending me the occasional poem or two for the past half decade or so, I’d been attempting to convince him to allow me to produce a second chapbook; those queries were the only parts of my letters he never responded to. Despite that, I’d managed to include a new poem in the “Tuesday poem” series , and further new poems in two different issues of the small poetry journal Touch the Donkey : two poems in #3 (October 2014) and a single poem in #6 (July 2015). He declined to be interviewed.

Slim Chances

the Mexican billionaire, or maybemultibillionaire, Carlos Slimhas sold his majority holdings in some telecomcompany I was surprisedhaving just read his namein Thomas Picketty’s book on Capitalismin the 21st Century – no doubthe’d discovered the gent inreading Forbes magazine

– no doubt becausehis government could not accuse him then ofmonopolizing communications

– Picketty no doubt would include himon a list of capitalists who should betaxed quite highly

to reduce the inequality between theupper & lower classes incontemporary society –

I wouldn’t be surprised if Slim, reading Picketty,just smiled . (Touch the Donkey #6)

I shall miss his occasional quick notes and accompanying poems and computer graphics; I shall miss his generosity.

Published on March 09, 2016 05:31

March 8, 2016

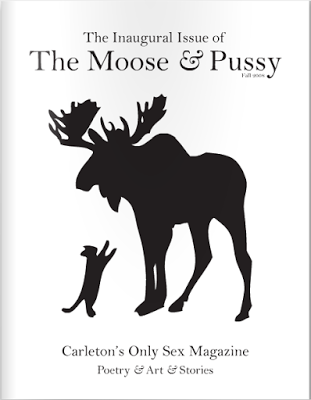

The Moose and Pussy (2008-2012): bibliography, and an interview

this interview was conducted over email from January – February 2016 as part of a project to document Ottawa literary publishing. see my bibliography-in-progress of Ottawa literary publications, past and present here

Jeff Blackman’s poetry has appeared in periodicals such as Blacklock’s Reporter, In/Words, and The Steel Chisel, the anthology

Five

(Apt. 9 Press), and

Best Canadian Poetry in English 2015

(Tightrope Books). He keeps warm in Ottawa, Ontario, with his growing family. Visit jeffblackman2001.wordpress.com for poetry and downloadable chapbooks.

Jeff Blackman’s poetry has appeared in periodicals such as Blacklock’s Reporter, In/Words, and The Steel Chisel, the anthology

Five

(Apt. 9 Press), and

Best Canadian Poetry in English 2015

(Tightrope Books). He keeps warm in Ottawa, Ontario, with his growing family. Visit jeffblackman2001.wordpress.com for poetry and downloadable chapbooks.

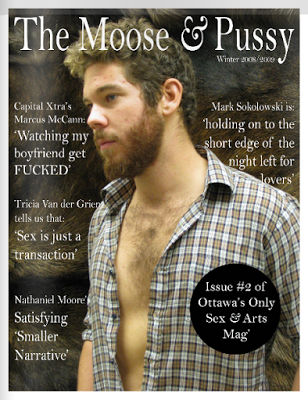

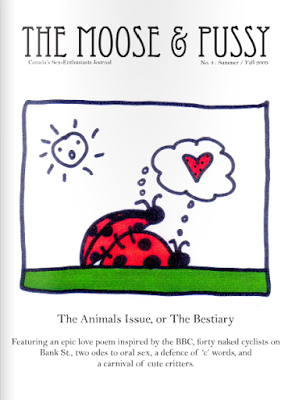

The Moose and Pussy #1-5 can be read online here, and copies of issues #6-8 are still very much available through Jeff Blackman via twitter: @jeffblackman2k1

Q: How did TheMoose and Pussy first start?

A: Fellow Carleton student and In/Words contributor Kate Maxfield and I fell in love in 2006, after a courtship hooked to writers’ circles and readings. In/Words is Carleton’s student-run literary press and at the time there were a lot of new spin-off mags, such as the feminist Vagina Dentata, first-year-centric Blank Page, and the French Mot Dit. Our courtship was inextricably linked to writers’ circles and readings, and we were both writing – including lots about our own relationship. It wasn’t long before we thought, heck: let’s start a literary sex magazine. We invited other community-members Jeremy Hanson-Finger and Rachael Simpson to join us as editors, and launched our first issue in mid-2007.

Q: Were there any influences on the journal outside of your immediate circle? Were there any other publications you were influenced by, or were you responding to what you saw as a lack?

A: In a way, yes, we saw a lack. While some of us read Literotica and some read Vice, we weren’t aware of magazines publishing smart sex writing. Even if there were, we still would have gone ahead, because I think it was more an outlet than anything else. It should be noted we were young, early 20s, and definitely not the cool kids. We were outsiders who had found this writing community at Carleton and wanted to make something together, and to an extent get our ya-yas out. Jeremy was especially versed in transgressive literature and felt motivated to disrupt the easy and the safe (he wrote his MA thesis on Pynchon & Wallace), and I think we all had a bit of that: a belief we would turn heads, and that other people would flock to the cause.

Q: How did your experience with In/Words shape the way you approached editing and publishing a magazine?

A: While only I’d been an editor for In/Words, we’d all been regulars to the weekly writers’ circles, monthly open-mikes, and help to make a lot of chapbooks. This community experience led to us all working through selection and design decisions together (at least for the first few issues), as well as the idea that we should print the magazine ourselves (which we did for the first two issues).

However, and In/Words’ editor-in-chief Collett Tracy has rightly said I aimed to leave In/Words in our dust, we definitely dreamt big. We sought out local advertisers, actively solicited art, even bringing student Tanya Decarie (now spoken word champ Twiggy Stardust) on as an illustrator, and got the magazine in stores throughout Ottawa. A few copies even wound up in Toronto and Montreal shops. We wanted to have a core community in Ottawa, which meant we still had Valentine’s Day card-making parties and film screenings, but we loved sending out copies to contributors from around the world. We wanted to go beyond the university, and we thought ourselves rather professional – despite being relative virgins to the world of publishing.

Q: What was the process of soliciting submissions? Did you initially send out a wide call, or solicit from your immediate community?

A: We began local, soliciting work from colleagues in the community. This would have been buttressed by some posters around Carleton campus and emails sent to In/Wordscontributors. We’d been talking the thing up enough that we knew we could put together an issue largely from our own connections, and it gave us a contributor & reader base which stayed with us. By issue two, if memory serves, we were listing ourselves online via submission aggregators.

So from issue one to seven we went from probably 20 or so submissions to well over a hundred per issue. However for the final huzzah, issue 8 (Codename: Oral) we directly solicited recorded poems from previous contributors, with a focus on community members and favourite contributors.

Q: What kind of response were you getting? Did you hold launches for individual issues?

Q: What kind of response were you getting? Did you hold launches for individual issues?A: We held launches, some with In/Words and some a la carte. Our 2nd launch was part of a fundraiser for Bruce House, a local residence for people living with AIDS, and we were proud of that one. We broadcast a documentary about the house (by Taline Bedrossian, now with the NGC), and the event was co-hosted by the Dusty Owl at Swizzles on Queen. Good crowd, lots of readers, and we felt we were giving back to a city that had provided a wealth of contributions and inspiration.

Like anything else though, interest waned. For the fifth issue, we launched a la carte at Mercury Lounge. We had high hopes for that one (lots of art, big team, and a different venue) but that event really soured me. We had a number of readers, fair-sized crowd, but sold almost no magazines. Sour grapes I know, but I really can’t stand it when people come to your free event, drink a bunch of beer, but can’t drop five bucks for a student-run magazine, y’know?

Q: Presuming you were paying for the publication out of pocket, right? And how was the journal distributed otherwise?

A: We put a little bit of our own money into it, but largely we were supported by a combination of advertisement sales, Carleton Clubs & Societies funding, and magazine sales. Advertisers mostly included sex shops and head shops (Crosstown Traffic was our most loyal sponsor). We also had a few fundraiser events, like movie night on campus. The magazine was sold at events and a number of stores throughout Ottawa including magazine shops, sex shops, and head shops. We also sold a few individual issues and subscriptions online, and the mag did wind up in some stores outside Ottawa, on occasion.

The idea of including ads and focusing on sales was in part driven by a desire to produce a glossy, high quality magazine, and not have to depend primarily on the school or fundraising. It was really fulfilling to be four students in our early twenties going around town securing ad sales to places like Wicked Wanda’s, and seeing our magazine fly from the shelves of Mags & Fags and Venus Envy. In that way we weren’t like any other literary magazine, at least not since sex shops & book shops intermingled on Toronto's Yonge Street in the 1970’s.

Q: But for the final issue, which listed you as a single editor, the list of editors grew throughout the run of the journal. What was the process of working with so many editors for the journal, and how were final decisions made? Why bring on more editors?

A: For selection, we voted as a committee. For other decisions, we strived for consensus. We brought on more editors in order to alleviate the work load as submissions counts increased, and simply because people were interested.

A: For selection, we voted as a committee. For other decisions, we strived for consensus. We brought on more editors in order to alleviate the work load as submissions counts increased, and simply because people were interested.Q: After eight issues, what was behind the decision to finally suspend the journal?

A: Around issue seven, the last print issue, Rachael and Jeremy moved out of Ottawa to pursue this & that; Tanya would leave shortly thereafter. With the core of the team gone, we lacked the ability to keep up our production schedule (about three issues a year), and decided to focus online. For a couple years the magazine was simply a blog Kate & I maintained. The CD was definitely he last hurrah, one last big to do.

I think also we were getting a bit drained by the hunt for the good content. As any literary magazine editor can attest, you have to read a lot of really bad writing before you find much good stuff. With a literary sex magazine, it was probably doubly so. At a certain point the whole enterprise was just turning us off. The final issue, the audio one, was mostly solicited from previous contributors We used what money we’d saved up and used it to pay an honorarium to all contributors (something we’d never done before), and it was a nice send-off. We were doing again / for the last time, what we had set out to do at first, which was build up from a community of writers a wealth of provocative, meaningful collection of sex writing.

Q: What do you feel your experiences with In/Words and The Moose & Pussymight have contributed to your own writing?

A: Those magazines & their communities were my life for 2007 through 2012, during which time I feel I matured as a writer. Before then I was still the sort of middle-class beat-wannabe who thought every one of his diary entries was inspired. It’s hard to say exactly what the experience of being an editor had on my writing, as at the same time I was hosting writers’ circles and open-mike nights, editing and producing friends’ chapbooks, and taking writing workshops. It’s impossible to figure out what the M&P did for my writing, other than, I hope, make me braver.

Q: Given your experiences with In/Words and The Moose & Pussy, do you see yourself ever returning to literary publishing?

A: If I have a good idea for something new, I’d do it. What’d really excite me would be if someone else with a good idea invited me to help them.

The Moose & Pussy bibliography:

The Moose & Pussy bibliography:The Moose & Pussy #1: The Inaugural Issue. Fall 2008. Editors: Jeff Blackman, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Kate Maxfield and Rachael Simpson. Editorial by Jeff Blackman, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Kate Maxfield and Rachael Simpson. Sex You Can Read by Aaron Clark, Andrew Battershill, Anna Sajecki, Ben Ladouceur, Courtney Davis, F.C. Estrella, Jeff Blackman, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, John Cloutier, Kane X. Faucher, Kate Maxfield, Lindsey N. Woodward, Natalee Elizabeth Blagden, Nicholas Surges, Owen Hewitt, Peter Gibbon, Rachael Simpson, Teri Doell and Soggy Tickets. Sex You Can See by Erin Iverson, Joni Sadler, Nicholas Surges, Robyn Riley and Sarah Flathers.

The Moose & Pussy #2. Winter 2008/2009. Editors: Jeff Blackman. Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Kate Maxfield and Rachael Simpson. Editorial by Jeff Blackman. Sex You Can Read by Amanda Earl, Anna Sajecki, Ben Ladouceur, Calum Marsh, Daniel Zomparelli, F.C. Estrella, Jason Decker, Kane X. Faucher, Kathleen Brown, Kenneth Pobo, Leah Mol, Lindsey N. Woodward, Marcus McCann, Mark Sokolowski, Nathaniel Moore, Owen Hewitt, Peggy Hogan, Richard Scarsbrook, Sonia Saikaley, Teri Doell, Tricia Van der Grient, Warren Dean Fulton and Poppy Cox. Sex You Can See by Christopher Neglia, Erin Iverson, Jenn Huzera, Ralitsa Doncheva.

The Moose & Pussy #3: For Pseudonyms, Souls. Spring 2009. Editors: Jeff Blackman, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Kate Maxfield and Rachael Simpson. Editorial: Kate Maxfield. Sex You Can Read by Andrew Battershill, Andy Sinclair, Bardia Sinaee, Ben Ladouceur, Bill Noble, Brian Brown, Chad Woody, Edward Lemond, Hauquan Chau, J.J. Persic, Jadon Rempel, John Oliver Hodges, Jose Fernandez, juniper n.a. quin, Kevin Brown, Leah Mol, Lindsey N. Woodward, Luke LeBrun, Luna Allison, Madeline Moore, matthew whitely, Rotem Yaniv, Stephen Joseph, Steve Zytveld, Taline Bedrossian, Teri Doell and Tom Mallouk. Sex You Can See by Tanya Decarie.

The Moose & Pussy #4: The Animals Issue, or The Bestiary. Summer/Fall 2009. Editors: Jeff Blackman, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Kate Maxfield and Rachael Simpson. Editorial by Rachael Simpson. Sex You Can Read by Ben Ladouceur, Brendan Inglis, Bryan Borland, Calum Marsh, Chelsey Storey, David Brennan, Jamie Bradley, Julie Innis, Justin Million, Kate Maxfield, Kristel Jax, Leah Mol, Mark Burns Cassell, Mark Naser, Peggy Hogan, Samantha Everts, Shannon Rayne, shawn macmillan and Warren Dean Fulton. Sex You Can See by Becky Beach, Kristel Jax and Tanya Decarie.

The Moose & Pussy #5: Versus the Sexless Marriage. Winter 2010. Editors: Jeff Blackman, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Kate Maxfield, Rachael Simpson and Tanya Decarie, Editorial by Jeremy Hanson-Finger. Sex You Can Read by Andrew Battershill, Barbara Foster, Chris Weige, Christine Sirois, Danielle Blasko, Jenna Jarvis, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Jessica Azevedo, John Grochalski, Kasandra Larsen, Katie Moore, Ken Shakin, Pippa Rogers, Rachael Simpson, Rotem Yaniv, Stephen S. Mills and Tanya Decarie. Sex You Can See by Kristel Jax and Tanya Decarie.

The Moose & Pussy #6: The Crucifiction Issue. Spring 2010. Editors: Jeff Blackman, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Kate Maxfield, Pippa Rogers, Rachael Simpson and Tanya Decarie. Sex You Can Read by Andy Sinclair, Bardia Sinaee, Chad Hammett, Chris Carroll, Gus Ginsberg, Hauquan Chau, Jeff Blackman, Jeff Fry, Jenna Jarvis, Jessica Azevedo, John Harrower, Kristel Jax, Kristy Logan, Marcus McCann, Matt Dennison, Peter Gibbon, Pippa Rogers and S. Gabriella. Sex You Can See by Kristel Jax and Tanya Decarie.

The Moose & Pussy #7: The Back to School Special. Fall 2010. Editors: Jeff Blackman, Jenna Jarvis, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Kate Maxfield, Pippa Rogers, Rachael Simpson and Tanya Decarie. Editorial by Jeff Blackman, Kate Maxfield, Tanya Decarie. Sex You Can Read by Andrew Battershill, Bardia Sinaee, Christian McPherson, Crystie Lovestrom, Danielle Blasko, Dave Currie, David Porder, Flower Conroy, Frederick Blichert, Jess Scott, John Kelly, Josh Nadeau, Lee Minh Sloca, Lisa Slater, Meaghan Rondeau and patrick mckinnon. Peter Gibbon. Sex You Can See by Kaelan Murray and Tanya Decarie.

Valentine’s Day Cards. Winter 2011. Sex You Can Read by Jenna Jarvis, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Peter Gibbon, jesslyn delia smith, Adrian Lippert and Cameron Anstee.

self-portrait as the bottom of the sea at the beginning of time (chapbook). Spring 2011. Sex You Can Read by Ben Ladouceur.

The Moose & Pussy #8: Oral. Winter 2012. Producer: Jeff Blackman. Sex You Can Hear by Alice Shindelar, Annik Adey-Babinski, Bardia Sinaee, Ben Ladouceur, David de Bruijn, Diane Seuss, Ezra Stead, Ivana Velickovic, Jeff Blackman, Jenna Jarvis, Jeremy Behreandt, M.A. Istvan Jr., Pearl Pirie and Peter Gibbon. Sex You Can See by Illya Kymkiw.

Published on March 08, 2016 05:31

March 7, 2016

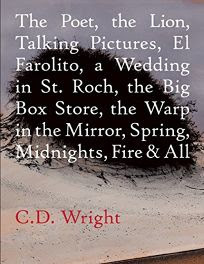

C.D. Wright, The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All

Spring & All

Between great hails to the imagination and salvos of opprobrium, William Carlos Williams set one sharp-edged poem after another into the composition of an unframed original. So the one who did not cast off his roots chose the eldest trope in the book, SPRING, to push and pull American poetry into the present tense. Not before he had initiated a willful number of false starts, cranking up anticipation and repeatedly sabotaging expectations. Not before the hectored reader was fetched up “by the road to the contagious hospital,” only then would the first glimpse of grass and “the stiff curl of wildcarrot leaf” be permitted—at the precise point at which every stick in the refuse emerged particular. Terrifying, as Robert Creeley was given to say.

Reminiscent of the work of Perth, Ontario poet Phil Hall for his own take on the essay-poemcomes American poet C.D. Wright’s (1949-2016) posthumous collection of prose poem-essays,

The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All

(Port Townsend WA: Copper Canyon, 2016). Given this collection appears mere weeks after Wright’s unexpected death in January gives the book an extra edge: a twinge of grief, of wondering what might-else-have-come (one can be heartened, slightly, by a 2015 interview in which she mentions two other forthcoming works, as she offered: “A book of poetry ShallCross will be out next year and then Casting Deep Shade, also in prose (with photographer Denny Moers)”). The pieces in the expansively-titled The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All blend a boundary between and through the prose poem and short essay, weave in and out of a variety of books and authors, with repeated sketches on the work of Jean Valentine, William Carlos Williams’ Spring & All (1923), Robert Creeley, Brenda Hillman, Gale Nelson, Michael Ondaatje’s Handwriting (1999), René Char and photographer and Wright-collaborator Deborah Luster, as she composes thoughtful, witty, deeply personal and utterly charming poem-essays on craft, style and subject. The ease in which Wright offers insight and commentary are intoxicating, as she seems to explain herself in the short piece “My American Scrawl,” a poem set near the beginning of the book: “Increasingly indecisive, about matters both big and little, I have found that poetry is the one arena where I am not inclined to crank up the fog machine, to palter or dissemble or quaver or hastily reverse myself. This is the one scene where I advance determined, if not precisely ready, to do battle with what an overly cited Jungian described as the anesthetized heart, the heart that does not react.”

Reminiscent of the work of Perth, Ontario poet Phil Hall for his own take on the essay-poemcomes American poet C.D. Wright’s (1949-2016) posthumous collection of prose poem-essays,

The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All

(Port Townsend WA: Copper Canyon, 2016). Given this collection appears mere weeks after Wright’s unexpected death in January gives the book an extra edge: a twinge of grief, of wondering what might-else-have-come (one can be heartened, slightly, by a 2015 interview in which she mentions two other forthcoming works, as she offered: “A book of poetry ShallCross will be out next year and then Casting Deep Shade, also in prose (with photographer Denny Moers)”). The pieces in the expansively-titled The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All blend a boundary between and through the prose poem and short essay, weave in and out of a variety of books and authors, with repeated sketches on the work of Jean Valentine, William Carlos Williams’ Spring & All (1923), Robert Creeley, Brenda Hillman, Gale Nelson, Michael Ondaatje’s Handwriting (1999), René Char and photographer and Wright-collaborator Deborah Luster, as she composes thoughtful, witty, deeply personal and utterly charming poem-essays on craft, style and subject. The ease in which Wright offers insight and commentary are intoxicating, as she seems to explain herself in the short piece “My American Scrawl,” a poem set near the beginning of the book: “Increasingly indecisive, about matters both big and little, I have found that poetry is the one arena where I am not inclined to crank up the fog machine, to palter or dissemble or quaver or hastily reverse myself. This is the one scene where I advance determined, if not precisely ready, to do battle with what an overly cited Jungian described as the anesthetized heart, the heart that does not react.”In a Word, a World

I love the nouns of a time in a place, where a sack once was a poke and native skag was junk glass not junk and junk was just junk not smack and smack entailed eating with your mouth open, and an Egyptian one-eye was an egg, sunny-side up, and a nation sack was a flannel amulet, worn only by women, to be touched only by women, especially around Memphis. Red sacks for love and green for money. Of course the qualifying adjective nation does exercise an otherwise eventful noun.

As her title, a collage of multiple references, hints, Wright’s The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All is a bricolage from a lively, engaged reader pulling at strands from a variety of corners of American poetry and stitching them together into a comprehensive through-line, one that only she could have constructed. The repetitions of title, subject and author throughout allow for some intriguing movements, such as the half-dozen poems referencing Jean Valentine, for example, that, instead of attempting to contain the complexity of an author’s work in a single piece, expand into a series of facets, each exploring another element or idea in Valentine’s writing. The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farolito, a Wedding in St. Roch, the Big Box Store, the Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All showcases the depth of what we have lost through the author’s sudden death: a restless curiosity, a thoroughly engaged mind, and heart as large as the continent. As Wright writes to open one of the “Jean Valentine, Abridged” poems: “The poems stay resolutely strange. When I say the writing is strange, I mean the writing resides on the positive side of the strangeness axis.” An earlier piece with the same title opens: “When I read Jean Valentine’s poems I fill up with questions, flow over with emotion. I cease, in some ways, to think.” She continues:

It is not that the writing is hermetic; in fact, I believe its entire pitch and purpose is openness. I grasp that the whole life—of loving and losing, erring and righting, reading and thinking, saying and seeing—is faithfully recorded, word for word, and submerged under each elliptic dot. She is “shy of words but desperately true to them,” wrote Seamus Heaney. “Looking into a Jean Valentine poem is like looking into a lake,” wrote Adrienne Rich. I think I see what Valentine sees: her own outline and what has settled below. But I am wary of describing it.

Published on March 07, 2016 05:31

March 6, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Talya Rubin

Talya Rubin is a poet and performance maker, her poetry won the Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers. In 2011, she was short-listed for the Winston Collins/Descant prize for Best Canadian poem and was a finalist for the Montreal International Poetry Prize. She won the Battle of the Bards at Harbourfront and was invited to attend IFOA in 2015. Talya holds an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC and currently lives in Montreal with her husband and son. Her first book of poetry,

Leaving the Island

, was published with Véhicule Press in April 2015. She also runs an interdisciplinary performance company, Too Close to the Sun.

Talya Rubin is a poet and performance maker, her poetry won the Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers. In 2011, she was short-listed for the Winston Collins/Descant prize for Best Canadian poem and was a finalist for the Montreal International Poetry Prize. She won the Battle of the Bards at Harbourfront and was invited to attend IFOA in 2015. Talya holds an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC and currently lives in Montreal with her husband and son. Her first book of poetry,

Leaving the Island

, was published with Véhicule Press in April 2015. She also runs an interdisciplinary performance company, Too Close to the Sun.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Poetry is a quiet art. It has a small readership and is a very niche market. And unlike theatre, which is where I have put a good deal of my focus up until now, there is not that immediacy of audience feedback. So it has been a bit of an adjustment, in all honesty. That this book exists in the world and quietly ticks along, with some really nice things happening, like recently going to IFOA in Toronto, is absolutely fantastic.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

There was a lot of language in my upbringing. My mom is an actor and translator and she had us reading Shakespeare and cueing her on lines from an incredibly young age. I do remember loving the language in Shakespeare, its authority and power. And the King James Bible , that was around too. The Golden Bough was another text being referred to a lot. I remember playing a game with the Oxford English Dictionary where we would pick a very obscure word, make up two definitions as well as read the real one and have to guess what the word meant. Total nerds! I wrote a novella when I was 15, so I thought I would be a novelist at some point. And wrote plays very young, too. But poetry did come first.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I tend to harbour something for a while, maybe a year before I set out to seriously start writing. The idea ripens until it is ready to break open. It seems like nothing, but there is this background way of working that seems to me to be almost unconscious, the way the mind processes what happens to you through dreams. But then there comes a point where serious research and time at a desk begin.

I do lots of drafts of poems. It is rare something comes out the first time fully formed. It has happened, but I am always skeptical when it does because you want to reach further, push deeper into language and ideas and if it comes out in one rush of inspiration I will often leave something for a while and see how it holds up in the light of day. I write in notebooks by hand. And I do keep notebooks with lots of words, ideas, jottings, title names, research passages, that I dive into when I am creating something new.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?