Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 348

April 14, 2016

Nicole Markotić, whelmed

bandonto wild. wild, bodacious, bandit, and braded. a rear deposit, posited. trade for trade, and weary, and eerily, and –ily. give up colour and fluenced broadsides. this rag, this peppered snag. grasp the ladder and holes won’t stream by. bandy-on, clever a-hoy. a-cling, a-stifle, a-stash. carry on, to the final creet coda. sneeze first, ask proposals anon. (“a-”)

While I understand she’s been doing other work in the interim, I’m simply (selfishly) pleased that we don’t have to wait another series of years for a new poetry collection from Windsor, Ontario writer, editor and critic Nicole Markotić. Her fourth poetry collection,

whelmed

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2016), comes fairly quickly after her prior,

Bent at the Spine

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2012) [see my review of such here], especially when you consider the length of time between these and her earlier poetry collections: Connect the Dots(Toronto ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 1994) and Minotaurs & Other Alphabets(Wolsak & Wynn, 1998). The editor of

By Word of Mouth: The Poetry of Dennis Cooley

(Waterloo ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2007) and author of two novels, Yellow Pages: a catalogue of intentions (1995) and

Scrapbook of My Years as a Zealot

(Vancouver BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2008), Markotić has long explored elements of lyric prose, and for whelmed, she shifts her gaze, slightly, for the sake of the prefix, both as subject and form. As the book opens with the section “a-,” itself composed out of a dozen short poems (such as the one above), subsequent sections in the collection include “ab-,” “ad-” “auto-,” “be-,” “bi-,” “co-,” “com-,” “con-,” “de-” and “dis-,” as well as the section “ins & outs,” a short sequence that appeared last year as a chapbook through above/ground press.

While I understand she’s been doing other work in the interim, I’m simply (selfishly) pleased that we don’t have to wait another series of years for a new poetry collection from Windsor, Ontario writer, editor and critic Nicole Markotić. Her fourth poetry collection,

whelmed

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2016), comes fairly quickly after her prior,

Bent at the Spine

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2012) [see my review of such here], especially when you consider the length of time between these and her earlier poetry collections: Connect the Dots(Toronto ON: Wolsak & Wynn, 1994) and Minotaurs & Other Alphabets(Wolsak & Wynn, 1998). The editor of

By Word of Mouth: The Poetry of Dennis Cooley

(Waterloo ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2007) and author of two novels, Yellow Pages: a catalogue of intentions (1995) and

Scrapbook of My Years as a Zealot

(Vancouver BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2008), Markotić has long explored elements of lyric prose, and for whelmed, she shifts her gaze, slightly, for the sake of the prefix, both as subject and form. As the book opens with the section “a-,” itself composed out of a dozen short poems (such as the one above), subsequent sections in the collection include “ab-,” “ad-” “auto-,” “be-,” “bi-,” “co-,” “com-,” “con-,” “de-” and “dis-,” as well as the section “ins & outs,” a short sequence that appeared last year as a chapbook through above/ground press.lornto prompt the miserable wretch, hoard the past participle of praved. to be deity for saken. to bandon all former nications. to go and to originate. is that right? to accurately spurt apple pips. to bargain a dreary release that refunds that lugubrious sky hook. too triste in the east. to author the mud on the dais in the linguistic circus. to gloom. O lorne. (“for-”)

If her prior poetry collections, through the prose poem, focused more on the sentence, then the poems in whelmedfocus instead on the lyric fragment, whether accumulating together in the prose poem, or utilizing a rhythmic scattering across the length and breadth of the page. There is the most luscious bouncing, nearly sing-song, quality here, one not usually featured so prominently in Markotić’s work. There’s always been an element of influence from the work of Winnipeg poet Dennis Cooley, but has Markotić’s recent work editing his critical selected prompted this shift? The poems in whelmed are incredibly playful, gymnastic in their rhythms and meant to be heard, utilizing slang, text and chat acronyms, each composed as lyric accumulations stretched across as a short study on a particular prefix and word combination. As the poem “ly” in the section “over-” reads:

joyed but also shadowed. past beyond, into super-flushed realms. a Times Roman sodoku, ordinately and orbitantly solved. stump and bozzlebam. or boozle. neither cukes nor thinly sliced zucchini. unless yellow and rectangular, less the yellow overlie. minus the revocable ‘t’

Published on April 14, 2016 05:31

April 13, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Brent van Staalduinen

Brent van Staalduinen

lives, works, and finds his voice in Hamilton.

SAINTS, UNEXPECTED

, his novel of urban magical realism, will be published by Invisible Publishing in the spring of 2016. His stories appear or are forthcoming in The Sycamore Review, Prairie Fire Magazine, The Bristol Short Story Prize Anthology, The Prairie Journal, EVENT Magazine, The Dalhousie Review, The New Quarterly, Litro Magazine, The Nottingham Review, and Urban Graffiti. A graduate of the Humber School for Writers, he also holds an MFA in creative writing from the University of British Columbia and teaches writing at Redeemer University College.

Brent van Staalduinen

lives, works, and finds his voice in Hamilton.

SAINTS, UNEXPECTED

, his novel of urban magical realism, will be published by Invisible Publishing in the spring of 2016. His stories appear or are forthcoming in The Sycamore Review, Prairie Fire Magazine, The Bristol Short Story Prize Anthology, The Prairie Journal, EVENT Magazine, The Dalhousie Review, The New Quarterly, Litro Magazine, The Nottingham Review, and Urban Graffiti. A graduate of the Humber School for Writers, he also holds an MFA in creative writing from the University of British Columbia and teaches writing at Redeemer University College.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’m at a very interesting point in the release schedule for SAINTS, UNEXPECTED, which will be released on April 15. I’ve sold the book, done all the major revisions, and am just now choosing a final design for the cover. So the short answer is that I’m almost able to hold the final version of my debut novel in my hands, which is the culmination of my writing aspirations thus far, and so incredibly exciting I sometimes have trouble believing that my novel, my words, sweat, and tears, will soon be out there in the wild.

The longer answer is that on a day-by-day, practical level my life hasn’t changed much at all: I still have family to care for, writing to create, my library job to show up at, and life to grab hold of, and I’m finding that those things, those regular efforts and joys, are really the things that are changing my life in measurable quantities. From a writing standpoint, too, I’m seeing real fruits from the overall ground campaign that is my writing life—winning the Bristol Short Story Prize, getting a nod for the Journey Prize, landing regular publications, and so on—and am being changed as an artist as I find success and get better at the “smaller” tasks we work towards. So, yes, life changes, and I’m seeing some success, but at this point the novel’s release feels like another piece—a big piece, of course—of the individual efforts that go into everything else.

That said, ask me again in six months, a year—maybe I’ll have a different perspective when the book has been out there for a little while.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

For me, my first love is fiction, although I’ve been having some remarkable success with my creative nonfiction. In his comments towards my undergrad independent study portfolio fifteen years ago, Hugh Cook, novelist and my former writing instructor (now colleague) at Redeemer, noted in his comments that he had a feeling I’d be finding more success in my fiction than in poetry. He was right. I enjoy poetry, but as an oft-confounded but loyal spectator with cracked binoculars: with prose, I’m staring to realize that I have some skills to offer the team down on the field, and even find myself occasionally in the starting lineup.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

In terms of starting, I start when the words start flowing, and this can be immediately or begin, in the case of a few projects, years after conception. Once I’m writing, my pace feels slow, but the more I encounter the writing processes of other writers, it’s actually pretty quick. Mechanically and structurally, I think my drafts hold up well to their final form, although the elements within always, always, always need development and nudging before I can call a draft ready to submit. Like many writers, I have difficulty with calling any of my work finished—some of the better drafts have found some great literary homes, yet the barest sense of self-control keeps me from endlessly monkeying with all of them.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’m often inspired at odd moments by an image or a phrase, or I find myself reading something that makes me want to get back to my own craft. Unless I abandon them mid-way, which only happens occasionally, products always become what I set out to create: stories become stories, novel manuscripts become novel manuscripts. There’s a shared root, though, to be sure: SAINTS, for example, first appeared in a short story, but the novel’s premise and conflict was created on their own, and it was drafted as a novel from day 1 (as a NaNoWriMo project, incidentally).

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. For three reasons: first, although I’m an introvert, I’m comfortable speaking with people, and my Fanshawe College radio broadcasting training ensures that my voice is moderated and that I measure what I say; second, I don’t write just for myself and love sharing my work with others; and third, it’s a universal truth that we all love having stories read to us—it’s a privilege to do so.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I love it when my readers talk about the themes they identify in my work, and I’m frequently surprised by what gets found in the characters and conflicts I create. I think this is because I always start with story: discovering what is desired or struggled against, and exploring how those elemental concerns impact the characters. The more tangible and concrete I make the situations and settings, the more meaning can emerge through the experience of the story. I won’t say that I’m never aware of the themes and larger issues as they appear, but I try not to be swayed by them as they’re created. I grew up with morality tales and fables and the didactic tripe that can get passed off as “religious” fiction and have discovered—like many of us—that truths are rarely laid out so neatly. It can go other extreme ways, of course, with writing that is oppressively dark or obscene, so mired against a particular philosophy or issue that only those steeped in that reality can understand it, or so unconventional it becomes opaque. I hope readers find truths in my work, although I refuse to tell them what they are: good writing will always reveal what’s deepest and most meaningful, most often in a mucky and twisted way.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Tell good stories well. Stories matter. Words matter.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both. Although in an overall sense I’m an effective self-editor, my blindness to certain tics and flinches in my writing is almost total.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Try to notice and make record of meaningful things. Then put your ass in the chair and write about them.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Between fiction and nonfiction the transition has been steady, if not seamless: good craft and good story translate well to both genres.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Morning is my best creative time, but right now, with a new baby and a toddler in the house, I write when (if) I can.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

It’s probably too easy to say good literature, but for me that’s a given: I love seeing what others are doing with words. Specifically to my situation, though, my involvement in projects can be all-consuming, so when I have the chance to breathe and look around, I try to do so as intentionally as possible, and absorb inspiration from life going on around me. So much of what gives my stories colour comes from what gives life its colour.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Frying onions. The smell of simmering spaghetti sauce. Earl Grey tea. Good coffee.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

While I avoid overtly including spirituality in my creative work, I’d be a fool if I didn’t acknowledge that my faith informs a large part of who I am and what I do. In my old age, I’ve come to love the liturgical and meditative side of my Christianity: paying attention to the words of belief and the rhythms they inspire. Also, I suppose by extension, I’m drawn to what some might call the supernatural or speculative, but what I’d call the powers that move just beyond our sensory perception: there is a lot happening in the world that isn’t guided by human intent. It’s fascinating to imagine, for example, the machinations of angels, demons, djinn as they move and live in dimensions other than the actual, and what echoes here in the real as a result.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I lean most on contemporary writers for my inspiration, and for the satisfaction I get from how we are writing now (as opposed to how Donne, Bronte, or Dickens wrote, by example), for the muscularity and simplicity we’re seeing in the best new literature.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Make, from scratch, the perfect Thai green curry.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’d be a jet fighter pilot, no question. But one that lived in the earlier days of flight, when flying and air combat was personal and face to face. Or a Zen garden designer.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

At this point, my writing is part of who I am as a whole, which includes family life and responsibilities, working at the Hamilton Public Library, teaching writing at Redeemer University College, attending church and being a part of community, and so on. So I guess there is no “as opposed to” because I love that all my facets reflect and mirror all the others: I’m not sure I’d enjoy life as much if all I did was write.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’m 2/3rds of the way through Fifteen Dogs by Andre Alexis—pure genius—and dread getting to the end. Before that, my top 2015 reads were All True, Not a Lie In It, a novel by Alix Hawley, and Debris, Kevin Hardcastle’s heart-stopping collection of short fiction. Film-wise, Star Wars: The Force Awakens has re-ignited the Star Wars geek inside me.

20 - What are you currently working on?

My main project is husbandhood and parenthood these days, so there can’t be enough of that: more time with my girls, soaking in the ineffable and exhausting miracle of Daddyhood. Writing-wise, I actually finished a draft of a short story the other day, which because of editing SAINTS and life getting full, full, full, is my first real new creative output in about six months. Feels divine. I also have BOY, a novel manuscript, to flog to agents and publishers. One of these days I should also put together a short fiction manuscript and capitalize on my recent publishing successes. Write more stories, for sure.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on April 13, 2016 05:31

April 12, 2016

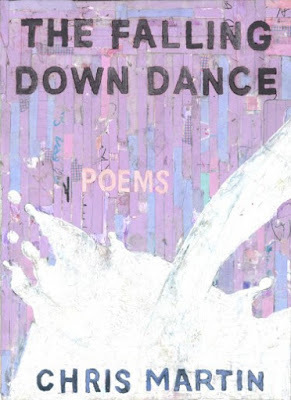

Chris Martin, The Falling Down Dance

After we touchdown, next morning, we get Octobersunburns in TransmitterPark, pregnanthipsters tanning elasticrounds. The EastRiver Ferry goes bothways, graffitiaccuses: YOU WOULD. Firstour child was a raspberry,then a prune, a peach, a fist, nowI fear the metaphorshave stopped. Little pluralurchin. Karaoke October I couldn’thelp bassing outon LoveWill Tear Us Apart. (“Hunger”)

In his third full-length poetry collection, The Falling Down Dance (Coffee House Press, 2015), Minneapolis poet Chris Martin [see his “12 or 20 questions” interview here] explores fatherhood through meditative stretches that wander across a series of lyric specifics set within a longer, abstract flow. Following his first two collections— American Music (Copper Canyon, 2007) and Becoming Weather (Coffee House Press, 2011)—the poems in The Falling Down Danceoccasionally read as wistful, composed as thoughtful and inquisitive takes on fatherhood, mortality, marriage, partnership and the intimate moments of watching your first child emerge, and evolve from baby into toddler. These are poems as rough sketches filled with curiosity, confusion and (an entirely normal) parental fear, as he writes to open the poem “Time”: “What / if these were / notes not / for something more / finished, but for something more / like ruins, not Gothic / Revival Horace / Walpole fakes, not stonewashed / jeans, but real ruins, lived-in almost / to death [.]” In an “Author Statement” included with the press release, he writes:

If The Falling Down Dance is more personal, more domestic, and more direct than any of my previous work, it is no less concerned with how strangers, friends, and family permeate our experience of the world, or, in the case of parenthood, begin largely to co-determine what that experience will be. The pressures of anticipation, confusion, and cognitive development create an experimental matrix where the time we share can be stretched, dilated, squeezed, and collapsed. It is a book about survival, about failure, and about what happens when we place the care of another human being at the center of our lives.

Throughout the collection, there are multiple poems titled “Time,” each of which holds a fine line between the long stretch of a moment, and how hours might simply disappear. “Snow is the conversation / winter makes with itself. No / quarrel, just endless / pretty tedium, blank / babble, the baby / making his thizz face / with a fistful / of white melting against / his quartet of teeth.” The book is thick with wonderfully-intimate details on pregnancy, birth and babies that you might only really comprehend if you’ve lived through the experience (such as the confusing fruit descriptions in the poem quoted above, a way that fetuses are described in some apps; such as knowing that in week twenty, your baby is roughly the size of a banana). I’ve been curious about the increase of poems on fatherhood over the past few years, including recent works by Jason Christie and Farid Matuk, for example (some of which I wrote about in my own four-part essay on fatherhood for Open Book: Ontario soon after our Rose was born in 2013), opening up a long overdue conversation on domestic/caregiving gender roles. Further in his “Author Statement,” Martin makes a curious turn, suggesting the difficulties, still, inherent in men being caregivers to their children, let alone possibly speaking or writing on such:

Throughout the collection, there are multiple poems titled “Time,” each of which holds a fine line between the long stretch of a moment, and how hours might simply disappear. “Snow is the conversation / winter makes with itself. No / quarrel, just endless / pretty tedium, blank / babble, the baby / making his thizz face / with a fistful / of white melting against / his quartet of teeth.” The book is thick with wonderfully-intimate details on pregnancy, birth and babies that you might only really comprehend if you’ve lived through the experience (such as the confusing fruit descriptions in the poem quoted above, a way that fetuses are described in some apps; such as knowing that in week twenty, your baby is roughly the size of a banana). I’ve been curious about the increase of poems on fatherhood over the past few years, including recent works by Jason Christie and Farid Matuk, for example (some of which I wrote about in my own four-part essay on fatherhood for Open Book: Ontario soon after our Rose was born in 2013), opening up a long overdue conversation on domestic/caregiving gender roles. Further in his “Author Statement,” Martin makes a curious turn, suggesting the difficulties, still, inherent in men being caregivers to their children, let alone possibly speaking or writing on such:The Falling Down Dance is poised to join the burgeoning conversation about fatherhood and masculinity. What does it mean for a father to take equal responsibility for the care of a child? What does it mean for a man to face the difficulties inherent in caring for a child, to shirk the self-possession by which we recognize masculinity and let himself instead be possessed by a frail, helpless, suffering being? How does a man speak about the constant and necessary failure that accompanies the lessons of fatherhood, of parenthood, the labor in simply trying to be competent? In portraying both the boy and despair inherent in early parenthood, The Falling Down Dance gives every parent a new, lyrical window into that most treasured, ephemeral experience. We need poems like these to tell us how we felt, especially in those early days when being too alive obliterates and bends time, when memory can’t accommodate the onrush and overflow of feeling. We need these poems to recall for us what we learned, what we lost, and to remind us how the falling that is inextricable from falling in love can make us more compassionate, more impassioned, more human.

Given that men have been able to write poems about the domestic for years (from Robert Creeley to Phil Hall to Barry McKinnon, among so many others), the difficulties Martin suggests perhaps say as much about his thoughts on such as it might the climate (but I can’t, obviously, speak to his experience). There are more male poets writing on parenting now than there ever have been, certainly, and the idea of such conflicting with maleness, however present it may or may not be, would be an intriguing conversation on its own. Martin’s efforts have shown (one hopes, to himself, as well) that such is far more possible than he ever could have imagined.

Published on April 12, 2016 05:31

April 11, 2016

Queen Mob's Teahouse : rob mclennan interviews Claire Farley on Canthius

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the eighth interview is now online:

an interview I conducted with Claire Farley on Canthius [a literary journal]

. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview I conducted with Dale Smith, on the Slow Poetry in America Newsletter, an interview with Ann Tweedy conducted by Mary Kasimor, an interview with Katherine Osborne, conducted by Niina Pollari, and an interview with Catch Business, conducted by Jon-Michael Frank.

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the eighth interview is now online:

an interview I conducted with Claire Farley on Canthius [a literary journal]

. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview I conducted with Dale Smith, on the Slow Poetry in America Newsletter, an interview with Ann Tweedy conducted by Mary Kasimor, an interview with Katherine Osborne, conducted by Niina Pollari, and an interview with Catch Business, conducted by Jon-Michael Frank.Further interviews I've conducted myself over at Queen Mob's Teahouse include conversations with Allison Green, Andy Weaver, N.W Lea and Rachel Loden.

If you are interested in sending a pitch for an interview my way, check out my "about submissions" write-up at Queen Mob's ; you can contact me via rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com

Published on April 11, 2016 05:31

April 10, 2016

Susan Landers, Franklinstein

In the beginning of this writing I thought: I must make alive the feeling of importance these little lost gentle things hold, existence being not very strong in them.

Some connections to place are patronizing.

At the Small Press Distribution website, Brooklyn poet Susan Landers’ remarkable Franklinstein (New York NY: Roof Books, 2016), subtitled “Or, the making of a modern neighborhood,” is described as a “hybrid genre collection of poetry and prose [that] tells the story of one Philadelphia neighborhood, Germantown—an historic, beloved place, wrestling with legacies of colonialism, racism, and capitalism. Drawing from interviews, historical research, and two divergent but quintessential American texts (

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

and Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans), Landers’ Franklinsteinis a monster readers have not encountered before.” Franklinstein certainly riffs off Franklin and Stein, as well as the idea of the collage-creation (creating new life out of dead parts), but, as she responds in an interview conducted by Christopher Schaeffer, posted in issue 7 of the online TINGE Magazine(spring 2014): “To call this project ‘collage’ is probably a misnomer. While the project had started out as a mash-up, at this stage in my writing, Franklin and Stein operate more as muses. Searching for language in their texts enables me to get fresh perspective and enter the poems from new angles. And because writing is difficult and I can get stymied by the enormity of Germantown’s history or the challenge of writing autobiographically, turning to these texts is a kind of release valve when writing, like letting the steam out of the radiator.”

At the Small Press Distribution website, Brooklyn poet Susan Landers’ remarkable Franklinstein (New York NY: Roof Books, 2016), subtitled “Or, the making of a modern neighborhood,” is described as a “hybrid genre collection of poetry and prose [that] tells the story of one Philadelphia neighborhood, Germantown—an historic, beloved place, wrestling with legacies of colonialism, racism, and capitalism. Drawing from interviews, historical research, and two divergent but quintessential American texts (

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

and Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans), Landers’ Franklinsteinis a monster readers have not encountered before.” Franklinstein certainly riffs off Franklin and Stein, as well as the idea of the collage-creation (creating new life out of dead parts), but, as she responds in an interview conducted by Christopher Schaeffer, posted in issue 7 of the online TINGE Magazine(spring 2014): “To call this project ‘collage’ is probably a misnomer. While the project had started out as a mash-up, at this stage in my writing, Franklin and Stein operate more as muses. Searching for language in their texts enables me to get fresh perspective and enter the poems from new angles. And because writing is difficult and I can get stymied by the enormity of Germantown’s history or the challenge of writing autobiographically, turning to these texts is a kind of release valve when writing, like letting the steam out of the radiator.”At the beginning of this writing I was reading. Reading two books I had never read before: The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin and The Making of Americans. And as I was reading, I thought: I should make a new book. A new book from pieces. A new book using only Ben’s words and Gertrude’s. And so I did that. For months. Cutting and pasting little pieces. To make a monster. And it was so boring.

It was so boring, my dead thing of parts.

Then the church I grew up in closed. The church where my mother and father were married. The church where they baptized their babies. A church in Philadelphia in the neighborhood where I grew up. A kind of rundown place. A place of row homes and vacant and schist.

And when I went there to see that place – the place that was with me from my very beginning – I thought, this will breathe life into my pieces. This will be the soul of my parts. I thought: if I could write the story of this place and its beginnings, this writing would be the right thing, a kind of living.

This is where my writing began.

At the beginning of this writing, historian David Young told me there is Germantown the place – a place of demographics, statistics, boundaries – and Germantown the constructed historical place – what people have chosen to save and memorialize, ignore or forget – and how some of those who talk about its history are plagued by nostalgia, by notions of an idealized past that never existed. He warned me that strong personal connections to this place can intensify a sense of decline, and that this melancholy does little to interpret the past in ways that do justice to the neighborhood as it exists today.

This is where my writing began: in a church I felt compelled to visit before it closed, before it became another vacant, beautiful building in a neighborhood of vacant, beautiful buildings. At the beginning of this writing, I was participating in behavior long practiced in Germantown – that of white people mourning what was. (“IT WAS MY DESIGN TO EXPLAIN (PART 1)”)

As Wikipedia informs: “Germantown is an area in Northwest Philadelphia. Founded by German Quaker and Mennonite families in 1683 as an independent borough, it was absorbed into Philadelphia in 1854. The area, which is about six miles northwest from the city center, now consists of two neighborhoods: ‘Germantown’ and ‘East Germantown’. Germantown has played a significant role in American history; it was the birthplace of the American antislavery movement, the site of a Revolutionary War battle, the temporary residence of George Washington, the location of the first bank of the United States, and the residence of many notable politicians, scholars, artists, and social activists.” The collage-elements in Landers’ Franklinsteinare an intriguing and incredibly powerful blend of what American poets Susan Howe and Juliana Spahr have also long done in their own work, as Landers utilizes both personal history and prior knowledge against research to attempt a portrait of a neighbourhood that has gone through numerous shifts and iterations both before and since her time there. Structured in sections that fragment and fractal, she blends prose with the lyric with the archive, setting research beside memory, and contemporary photos alongside scanned archival documents and testimonials by residents past and present. This is the sort of book that others, including myself, attempting to capture and comprehend geography through writing might wish they’d written. Much of the strength of the book, apart from the obvious clear force of her writing, is in how personal she allows it to be, without being entangled or hindered through a sentimental lens. Combined with her awareness of larger communities, Franklinstein is not simply about her and hers, but a larger context of geographic and cultural spaces, shifting perspectives, each utilized to reach an impossibly complex portrait, as she writes: “To come closer // to come to see // this writing must meander.”

This is a poem about pulping bibles to make bullets for a revolution – a bladder full of pokeberry juice – a portrait drawn in blood – about how impossible it was to get the right kind of mortgage – and how savage the lenders were in foreclosing – a postcard of a cemetery with the words still living scrawled across the front.

This is a poem about Sydney telling me we can get there wherever there is to have a decent life where the poetry happens – a poem about John and his bowl full of prayers – and Vashti who gets asked why she doesn’t live in Mt. Airy – and Rachael who says places like this are hard to navigate, all tied up with romance and symbolism and baggage – a poem about a poem about Kevon who gave me a hug – and Bernard who gave me a ride – and that guy who wanted to give me one of his minutes since I didn’t have one – and Tiptoe who called me a vampire.

These are the makings of an autobiography of America. (“THIS WAS THEN THE WAY I WAS FILLED FULL OF IT AFTER LOOKING”)

Published on April 10, 2016 05:31

April 9, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Dan Rosenberg

Dan Rosenberg is the author of The Crushing Organ (Dream Horse Press, 2012), which won the American Poetry Journal Book Prize, and

cadabra

(Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2015). He has also written two chapbooks, A Thread of Hands(Tilt Press, 2010) and

Thigh's Hollow

(Omnidawn, 2015), which won the Omnidawn Poetry Chapbook Contest. Rosenberg earned an M.F.A. from the Iowa Writers' Workshop and a Ph.D. from The University of Georgia. He teaches literature and creative writing at Wells College and co-edits

Transom

. His website is danrosenberg.us.

Dan Rosenberg is the author of The Crushing Organ (Dream Horse Press, 2012), which won the American Poetry Journal Book Prize, and

cadabra

(Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2015). He has also written two chapbooks, A Thread of Hands(Tilt Press, 2010) and

Thigh's Hollow

(Omnidawn, 2015), which won the Omnidawn Poetry Chapbook Contest. Rosenberg earned an M.F.A. from the Iowa Writers' Workshop and a Ph.D. from The University of Georgia. He teaches literature and creative writing at Wells College and co-edits

Transom

. His website is danrosenberg.us.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?When my first book was published, everywhere was a homecoming. I went on a tour with Adam Watkins, whose book came out at the same time from the same press. We reached out to friends who connected us with other people who hosted readings. Adam Clay, who was a total stranger when we were rolling through his corner of Kentucky, invited us to stay with him. And he promoted our reading. And when he found out we weren't savvy enough to have a Square reader, he gave us his. My book was my excuse to go out into the poetry world and meet people like him, people whose immediate kindnesses meant the world to me.

If that first book was a kind of homecoming, this new chapbook, Thigh’s Hollow, is an invitation into my home – into my brains and guts.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?Poetry came to me first, when I was a kid, because it allowed me to process things (my parents’ divorce, etc.) in utterly transparent code: A kangaroo finding a stable family to live with. It allowed me to feel clever, and I liked feeling clever. It took me a long time to stop enjoying poems that are merely clever – and even longer to stop trying to be clever myself. But I’ve never felt the impulse to write anything but poetry.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?I write quickly then gestate forever. I also tend to have multiple projects going at the same time – I write into each as I’m able. As for revision, mostly the shape of the poem is there by the time the first draft is complete. (I edit a lot as I go.) Some poems never look right, and I tinker and tinker until I realize those poems are never going to be any good, but the tinkering was the poem.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?Each poem begins on its own, as a scene or scrap of language or rhythm in my brain, but I can tell very quickly if it’s going in the book-length-project pile or the random-assortment-of-poems pile. I haven’t figured out how to write explicitly to flesh out a book, mostly because I don’t want to. Which might be the better answer to your question about writing poetry over prose.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I enjoy giving readings, but I’m acutely aware of how difficult it can be to hold onto a poem you’ve only heard read once. I tend to talk a fair amount around the poems, to provide what context I can, so I don’t lose everyone immediately. And then I feel anxious about having too much banter and distracting from the poems.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?I think the real current questions can’t be the ones we’re having conversations about now. The surrealists thought they were communists until the communist party came along and asked them to play nice. And on this side of the Atlantic, Dalí went and designed storefronts on 5th Avenue – and surrealism was digested in the great belly of American advertising, contrary to everything the other surrealists thought they were up to. All that time they were still talking about their revolution. We’ll know what today’s questions are tomorrow.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?I can’t speak for other writers, but for me, teaching is where I see my role as a writer most impacting the larger culture. My students grapple with poems that ask them to think, to feel, to listen more attentively than they do at any other point in their daily lives. Today my wife was on line at the DMV and everyone around her was talking about how excited they are to vote for Donald Trump. I think that’s a failure of our education system to promote attentiveness and thoughtfulness and empathy. I think poetry, well taught, can help fix it.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?Working with Omnidawn has been a dream! They have been collaborative, responsive, engaged – everything I could have asked for.

Most magazine editors don’t do much editing anymore, but some do – and I’m always grateful to get notes back on poems, to hear suggestions on how to make them better. Most recently, the Beloit Poetry Journal had a handful of comments on a poem they took. Some were great, and others I disagreed with. I have a thick enough skin that the process seemed benign at worst, helpful at best.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?“When the cat is sleeping, don’t try to lie down on him.” My son is a very active toddler.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to translation)? What do you see as the appeal?They recharge each other. My translation work is collaborative, so it’s an entirely different thing. If Boris were sitting beside me while I was trying to write my own poems, I’d freak out. But translation involves so much more puzzling out, so much more problem solving, and doing it together activates other parts of my brain.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?A typical day begins with a very small man shouting “HI!” right in my face and then laughing like a maniac. I’ve lost all writing routine in the aftermath of our son being born, but my wife and I take turns giving each other space and time to write. And to do the jobs we get paid for. So, the time comes irregularly, but it comes, and I’ve found my process shifting as a result.

The poems I’m working on now are in the Thigh’s Hollow form and voice – they’re more modular, easier to leave and come back to, and far more consistent in tone than my first two books, and that’s a direct result of my routine changing. Living in that one voice, poetically, has allowed me to pop into that world, write a bit, and pop back out, whereas before our son was born I could take an entire afternoon just sitting and staring off into space and call it working.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?I have a roster of great poets who I can always count on, Tomaž Šalamun foremost. Like many of us, his death last year hit me hard; he was one of those people who always seemed too alive to ever die.

But teaching also really energizes me: I read new work and reread old favorites with my students constantly, and that can usually kick me back in gear.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?I’ve had too many homes to answer this question.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?People, more than anything else, really. I’ve found my daily life creeping more and more into my poems, and I’m happy to see it there.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator” and Derrida’s “Des tours de Babel” both keep surprising me every time I read them. I also don’t know how I would get through a week, or a round of doing the dishes, without some of my favorite podcasts: My Brother, My Brother, and Me; Pop Culture Happy Hour, The Adventure Zone, International Waters, Stuff You Should Know … I spend a lot of time listening to people being funny and/or smart while I’m being neither.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?I’m very excited to meet the man my son will become.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?I like the idea that “writer” is my occupation. My employer is Wells College, and sure, they want me to write, but my primary occupation is to teach, and I’ve always known that’s what I wanted to do. There was a period of time when I was studying philosophy very intently, and I could have easily gone down that graduate school path too – which means I’ve never really considered a path that looked too different from the one I’m on now.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?Once I was done with college, I was interested to see what I would do. I’d never had the kind of freedom that a 9-5 job offers, in terms of not having to think about anything in particular from 5:01 to 8:59. Turns out, what I did in that free time was read and write poems. I can’t tell you why because I’ve never felt the need to interrogate that. I’m just grateful to have that impulse in my life.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?I’ve just been rereading Donald Barthelme’s Sixty Stories, because I’ll be teaching it in the spring. The book leaves me speechless, which is great, but I have no idea what I’m going to say to my students about it. As for film, I’m going to throw out a BBC show: Foyle’s War . It’s on Netflix. I love it.

20 - What are you currently working on?I’m writing into the project that Thigh’s Hollow is a part of. The larger collection is called Esau, and the poems I’m working on now are far more personal, far more intimate. I suppose I’m working on letting myself back into my poems.

12or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on April 09, 2016 05:31

April 8, 2016

U of Alberta writers-in-residence interviews: Caterina Edwards (1997-98)

For the sake of the fortieth anniversary of the writer-in-residence program (the longest lasting of its kind in Canada) at the University of Alberta, I have taken it upon myself to interview as many former University of Alberta writers-in-residence as possible [see the ongoing list of writers here]. See the link to the entire series of interviews (updating weekly) here.

Caterina Edwards’

latest book, her sixth, is a literary noir called

The Sicilian Wife

. Her previous book

Finding Rosa: A Mother With Alzheimer’s/ A Daughter’s Search for the Past

won the Writers Guild of Alberta Award for Nonfiction, the Bressani Prize for Writing on Immigration, and was shortlisted for the City of Edmonton Book Prize. She has also WGA Award for Short Fiction for a collection of stories

The Island of the Nightingale

, and the Edna Staebler Award in 2013 for her personal essay on Moldovian migrant workers. Her play Homeground was shortlisted for the WGA drama prize and the docudrama The Great Antonio was chosen to represent Canada in an international radio competition.

Caterina Edwards: Essays on Her Works

was the first book published in Guernica Editions Series on Canadian Writers.

Caterina Edwards’

latest book, her sixth, is a literary noir called

The Sicilian Wife

. Her previous book

Finding Rosa: A Mother With Alzheimer’s/ A Daughter’s Search for the Past

won the Writers Guild of Alberta Award for Nonfiction, the Bressani Prize for Writing on Immigration, and was shortlisted for the City of Edmonton Book Prize. She has also WGA Award for Short Fiction for a collection of stories

The Island of the Nightingale

, and the Edna Staebler Award in 2013 for her personal essay on Moldovian migrant workers. Her play Homeground was shortlisted for the WGA drama prize and the docudrama The Great Antonio was chosen to represent Canada in an international radio competition.

Caterina Edwards: Essays on Her Works

was the first book published in Guernica Editions Series on Canadian Writers.

She was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 1997-98 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you’d published a small handful of books over the previous decade and a half. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: When I began the residency, I was feeling frustrated as a writer. I had published a few books, but like many writers, I felt my work was not getting the recognition it should. And in the mid-nineties, everything I sent off to literary magazines and publishers was being rejected. I am still not sure if it was the times or simply bad luck. A book of short stories was about to be printed when the publisher and I had a disagreement, and he stopped the publication. I grew discouraged and depressed. Being asked to be the writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta helped to restore my confidence in myself as a writer. It also gave me precious time to concentrate on my writing. During that year, I began my nonfiction book, Finding Rosa, which eventually took me to another level in terms of both recognition and depth of writing.

So the opportunity meant a great deal, and I am still grateful.

Q: The bulk of writers-in-residence at the University of Alberta have been writers from outside the province. How did it feel as a University of Alberta graduate to be acknowledged locally through the position? Given you were returning to familiar grounds, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while there? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: I did feel honoured to be asked to be writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta. I had visited several of the early writers-in-residence for advice on my own writing. I remember Matt Cohen, the first WIR, as being particularly helpful. Later on, I was on campus working as a sessional and teaching creative writing courses. I even had an honours student, Sean Stewart, who did a seminar on the novella with me for his senior project. (He wrote one.) During that time, I got to know many of the WIRs: Marian Engel, Sam Selvon, Elizabeth Smart, Di Brandt, David Adam Richards, and more. I learned much about the literary life and the literary scene from casual conversations over a coffee or at a social events. So I benefited from that access too.

I can’t say that I was influenced by other writers on staff when I was WIR. It was a difficult year, since both my parents fell gravely ill. I didn’t have much hanging around time. But certainly I was influenced by the two writers on staff when I was a student: Rudy Wiebe and Sheila Watson. Their work taught me that you can, and perhaps should, write about this city and this province. (Make this place real.) And they taught me the writing life was difficult, serious, and important.

A few years ago, past U of A WIR were asked to write essays on mentorship for an anthology. I called mine “The Habit of Mentoring,” and I wrote about Sheila Watson’s influence, positive and negative, on my writing self. I realized this year the anthology wasn’t ever going to be published – so I gave the essay to a new anthology, Sheila Watson: Essays on Her Works.

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Were you working on anything specific while there, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: My time as writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta allowed me to work on several projects. I completed a short story that was published first in a magazine, then four years later in an anthology. It will appear again in a new anthology in 2016. I did half of a draft of a novel that was then put aside. I didn’t begin working on it again until 2010. It was finally published this year, 2015. (But it was named #55 in The National Post best 100 published books of 2015.)

Finally, and most significantly, I began both taking notes and researching for my creative nonfiction work Finding Rosa. This became a massive undertaking. I uncovered suppressed history and untold stories through extensive interviews with former Istrian-Italian refugees all around the world. The novel I am currently writing (The Bone-Collector’s Daughter) was inspired by one of the stories I uncovered during that year.

So I both wrote new work and expanded my repertoire by embarking a new genre (creative nonfiction).

Q: Were you interacting with any other non-fiction writers while in Edmonton, whether Myrna Kostash or Ted Bishop?

A: Yes, I was interacting with both Myrna Kostash and Ted Bishop. They both encouraged me to experiment. And we did discuss the genre. Myrna, in particular, suggested writers to read, such as Ryszard Kapuscinski and Patricia Hampl.

But I forgot to mention that one of the reasons I turned to creative nonfiction was that I co-edited with Kay Stewart, two books of life writing by women: Eating Apples: Knowing Women’s Lives and Wrestling With the Angel. I was working on the latter book during that year I was WIR, choosing essays for the anthology, prior to editing them.

Kay Stewart had a position in the Department of English then and specialized in teaching the writing of nonfiction. Kay encouraged me to read feminist nonfiction writers, such as Mary Carr, Terry Tempest Williams, and Maxine Hong Kingston, so she definitely influenced me.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? Were there any encounters that stood out?

A: I did at least two readings on campus and the turnout was good. As far as I can remember – and it was a number of years ago – I wasn’t invited to visit any creative writing classes. However, I was invited to go to one class that happened to be studying one of my essays. (It was in a textbook.) I can’t remember any students coming for a consultation, though some staff certainly did, most of whom were sessionals. I was kept busy responding to the work of both aspiring and emerging writers in the community. I remember four writer in particular. They stuck in my mind, because of the quality of their work. I became a mentor to one of them. She went on to publish stories and essays in anthologies and literary magazines. Another had already published a couple of books of poetry and came to consult about a memoir she was writing. The third was also writing a family memoir. A couple of weeks ago I came across mention of the fourth, Michael McCarthy. He told me he wrote poetry and had published some but wanted my reaction to a series of stories inspired by his childhood in Ireland. I told him the stories were terrific, but there was so many amazing writers writing those kind of Irish tales. Perhaps, I said, he should stick to poetry. Michael McCarthy’s name came up in The Guardian. They had asked a number of prominent writers for their favorite books of 2015. Hillary Mantel had chosen McCarthy’s The Healing Station.

So – did I give him good advice? Or stifle a potential great prose writer?

Caterina Edwards’

latest book, her sixth, is a literary noir called

The Sicilian Wife

. Her previous book

Finding Rosa: A Mother With Alzheimer’s/ A Daughter’s Search for the Past

won the Writers Guild of Alberta Award for Nonfiction, the Bressani Prize for Writing on Immigration, and was shortlisted for the City of Edmonton Book Prize. She has also WGA Award for Short Fiction for a collection of stories

The Island of the Nightingale

, and the Edna Staebler Award in 2013 for her personal essay on Moldovian migrant workers. Her play Homeground was shortlisted for the WGA drama prize and the docudrama The Great Antonio was chosen to represent Canada in an international radio competition.

Caterina Edwards: Essays on Her Works

was the first book published in Guernica Editions Series on Canadian Writers.

Caterina Edwards’

latest book, her sixth, is a literary noir called

The Sicilian Wife

. Her previous book

Finding Rosa: A Mother With Alzheimer’s/ A Daughter’s Search for the Past

won the Writers Guild of Alberta Award for Nonfiction, the Bressani Prize for Writing on Immigration, and was shortlisted for the City of Edmonton Book Prize. She has also WGA Award for Short Fiction for a collection of stories

The Island of the Nightingale

, and the Edna Staebler Award in 2013 for her personal essay on Moldovian migrant workers. Her play Homeground was shortlisted for the WGA drama prize and the docudrama The Great Antonio was chosen to represent Canada in an international radio competition.

Caterina Edwards: Essays on Her Works

was the first book published in Guernica Editions Series on Canadian Writers.She was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 1997-98 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you’d published a small handful of books over the previous decade and a half. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: When I began the residency, I was feeling frustrated as a writer. I had published a few books, but like many writers, I felt my work was not getting the recognition it should. And in the mid-nineties, everything I sent off to literary magazines and publishers was being rejected. I am still not sure if it was the times or simply bad luck. A book of short stories was about to be printed when the publisher and I had a disagreement, and he stopped the publication. I grew discouraged and depressed. Being asked to be the writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta helped to restore my confidence in myself as a writer. It also gave me precious time to concentrate on my writing. During that year, I began my nonfiction book, Finding Rosa, which eventually took me to another level in terms of both recognition and depth of writing.

So the opportunity meant a great deal, and I am still grateful.

Q: The bulk of writers-in-residence at the University of Alberta have been writers from outside the province. How did it feel as a University of Alberta graduate to be acknowledged locally through the position? Given you were returning to familiar grounds, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while there? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: I did feel honoured to be asked to be writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta. I had visited several of the early writers-in-residence for advice on my own writing. I remember Matt Cohen, the first WIR, as being particularly helpful. Later on, I was on campus working as a sessional and teaching creative writing courses. I even had an honours student, Sean Stewart, who did a seminar on the novella with me for his senior project. (He wrote one.) During that time, I got to know many of the WIRs: Marian Engel, Sam Selvon, Elizabeth Smart, Di Brandt, David Adam Richards, and more. I learned much about the literary life and the literary scene from casual conversations over a coffee or at a social events. So I benefited from that access too.

I can’t say that I was influenced by other writers on staff when I was WIR. It was a difficult year, since both my parents fell gravely ill. I didn’t have much hanging around time. But certainly I was influenced by the two writers on staff when I was a student: Rudy Wiebe and Sheila Watson. Their work taught me that you can, and perhaps should, write about this city and this province. (Make this place real.) And they taught me the writing life was difficult, serious, and important.

A few years ago, past U of A WIR were asked to write essays on mentorship for an anthology. I called mine “The Habit of Mentoring,” and I wrote about Sheila Watson’s influence, positive and negative, on my writing self. I realized this year the anthology wasn’t ever going to be published – so I gave the essay to a new anthology, Sheila Watson: Essays on Her Works.

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Were you working on anything specific while there, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: My time as writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta allowed me to work on several projects. I completed a short story that was published first in a magazine, then four years later in an anthology. It will appear again in a new anthology in 2016. I did half of a draft of a novel that was then put aside. I didn’t begin working on it again until 2010. It was finally published this year, 2015. (But it was named #55 in The National Post best 100 published books of 2015.)

Finally, and most significantly, I began both taking notes and researching for my creative nonfiction work Finding Rosa. This became a massive undertaking. I uncovered suppressed history and untold stories through extensive interviews with former Istrian-Italian refugees all around the world. The novel I am currently writing (The Bone-Collector’s Daughter) was inspired by one of the stories I uncovered during that year.

So I both wrote new work and expanded my repertoire by embarking a new genre (creative nonfiction).

Q: Were you interacting with any other non-fiction writers while in Edmonton, whether Myrna Kostash or Ted Bishop?

A: Yes, I was interacting with both Myrna Kostash and Ted Bishop. They both encouraged me to experiment. And we did discuss the genre. Myrna, in particular, suggested writers to read, such as Ryszard Kapuscinski and Patricia Hampl.

But I forgot to mention that one of the reasons I turned to creative nonfiction was that I co-edited with Kay Stewart, two books of life writing by women: Eating Apples: Knowing Women’s Lives and Wrestling With the Angel. I was working on the latter book during that year I was WIR, choosing essays for the anthology, prior to editing them.

Kay Stewart had a position in the Department of English then and specialized in teaching the writing of nonfiction. Kay encouraged me to read feminist nonfiction writers, such as Mary Carr, Terry Tempest Williams, and Maxine Hong Kingston, so she definitely influenced me.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? Were there any encounters that stood out?

A: I did at least two readings on campus and the turnout was good. As far as I can remember – and it was a number of years ago – I wasn’t invited to visit any creative writing classes. However, I was invited to go to one class that happened to be studying one of my essays. (It was in a textbook.) I can’t remember any students coming for a consultation, though some staff certainly did, most of whom were sessionals. I was kept busy responding to the work of both aspiring and emerging writers in the community. I remember four writer in particular. They stuck in my mind, because of the quality of their work. I became a mentor to one of them. She went on to publish stories and essays in anthologies and literary magazines. Another had already published a couple of books of poetry and came to consult about a memoir she was writing. The third was also writing a family memoir. A couple of weeks ago I came across mention of the fourth, Michael McCarthy. He told me he wrote poetry and had published some but wanted my reaction to a series of stories inspired by his childhood in Ireland. I told him the stories were terrific, but there was so many amazing writers writing those kind of Irish tales. Perhaps, I said, he should stick to poetry. Michael McCarthy’s name came up in The Guardian. They had asked a number of prominent writers for their favorite books of 2015. Hillary Mantel had chosen McCarthy’s The Healing Station.

So – did I give him good advice? Or stifle a potential great prose writer?

Published on April 08, 2016 05:31

April 7, 2016

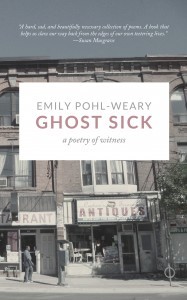

Emily Pohl-Weary, Ghost Sick

My short review of Emily Pohl-Weary's new poetry title,

Ghost Sick

(Toronto ON: Tightrope Books, 2015) is now online at Arc Poetry Magazine.

My short review of Emily Pohl-Weary's new poetry title,

Ghost Sick

(Toronto ON: Tightrope Books, 2015) is now online at Arc Poetry Magazine.

Published on April 07, 2016 05:31

April 6, 2016

Touch the Donkey supplement: new interviews with Kasimor, Mavreas, lopes, Smith, L’Abbé, Price and rawlings

Anticipating the release next week of the ninth issue of Touch the Donkey (a small poetry journal), why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the eighth issue: Mary Kasimor, Billy Mavreas, damian lopes, Pete Smith, Sonnet L’Abbé, Katie L. Price and a rawlings.

Anticipating the release next week of the ninth issue of Touch the Donkey (a small poetry journal), why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the eighth issue: Mary Kasimor, Billy Mavreas, damian lopes, Pete Smith, Sonnet L’Abbé, Katie L. Price and a rawlings.Interviews with contributors to the first seven issues, as well, remain online, including: Suzanne Zelazo, Helen Hajnoczky, Kathryn MacLeod, Shannon Maguire, Sarah Mangold, Amish Trivedi, Lola Lemire Tostevin, Aaron Tucker, Kayla Czaga, Jason Christie, Jennifer Kronovet, Jordan Abel, Deborah Poe, Edward Smallfield, ryan fitzpatrick, Elizabeth Robinson, nathan dueck, Paige Taggart, Christine McNair, Stan Rogal, Jessica Smith, Nikki Sheppy, Kirsten Kaschock, Lise Downe, Lisa Jarnot, Chris Turnbull, Gary Barwin, Susan Briante, derek beaulieu, Megan Kaminski, Roland Prevost, Emily Ursuliak, j/j hastain, Catherine Wagner, Susanne Dyckman, Susan Holbrook, Julie Carr, David Peter Clark, Pearl Pirie, Eric Baus, Pattie McCarthy, Camille Martin and Gil McElroy.

The forthcoming ninth issue features new writing by: Stephen Collis, Laura Sims, Paul Zits, Eric Schmaltz, Gregory Betts, Anne Boyer, François Turcot (trans. Erín Moure) and Sarah Cook. And, once the new issue appears, watch the blog over the subsequent weeks and months for interviews with a variety of the issue's contributors!

And of course, copies of the first eight issues are still very much available. Why not subscribe?

We even have our own Facebook group . You know, it's a lot cheaper than going to the movies.

Published on April 06, 2016 05:31

April 5, 2016

Ongoing notes: early April, 2016

Is it spring yet? I can barely tell, awaiting the new baby. Has it happened? I have no idea. What is sleep?

Is it spring yet? I can barely tell, awaiting the new baby. Has it happened? I have no idea. What is sleep?Don’t forget the ottawa small press book fair! It might not be happening until June, but if you write it on your calendars now, it gives you more than enough time to make something for it. And did you see I'm offering a series of very limited edition titles from above/ground press' mound of out-of-print backlist?

Montreal QC: I’m slightly frustrated at Vallum magazine and their wide array of chapbooks, nearly all of which I didn’t even know existed until recently, when I saw Don McKay read in Edmonton [see my report on such here] as part of the University of Alberta writers-in-residence anniversary with chapbook in hand, his Larix (2015). Did you know that the Vallum Chapbook Series is nearly twenty titles strong, with chapbooks by such as Fanny Howe, Jan Zwicky, George Elliott Clarke, Nicole Brossard, Mary di Michele, Sandy Pool and Blair Prentice, Eleni Zisimatos and Jason Camlot? I knew of a couple of the earlier titles, but I certainly didn’t know about their larger, rather impressive list.

Rhizosphere

Let’s pause and listen for what’s happeningunderground, with the roots, the rhizomes, andtheir close associates, the fungi and the worms.So much mycorrhizal promiscuity and death, suchheavy sinking and sucking among the microbes,so little regard for personal identity andhuman rights, such continuous French kissing,the birch and the Russala muchroom, the boletesand the larch, the Pink Lady’s Slippers and their specialfungal friends, all those hyphae busyhyphenating, corpse-compost, rot-root, the greatUr-symbiosis that is soil, the ecstatic, indecent,death-dissolving dance that will one daygather us up.

Given his prior publication was his seven hundred-plus page Angular Unconformity: Collected Poems 1970-2014 (Fredericton NB: Goose Lane Editions, 2014), it is good to see new work by McKay in such a small offering, one of his rare forays into small press chapbook publishing (there have been a few, including from Olive and a couple of other places, but not many). Larix, named for the tree genus that includes the larch, focuses its meditative lyrics on wood landscapes (with the occasional bird, as always, thrown in for good measure), shifting slightly from McKay’s prior geologic threads. McKay, as always, utilizes his thinking lyrics as a way of discovering, of “getting there.” As he writes in the poem “To Speak of Paths (2)”: “Which way is the way? A question / to be pondered and if possible / outwalked.”

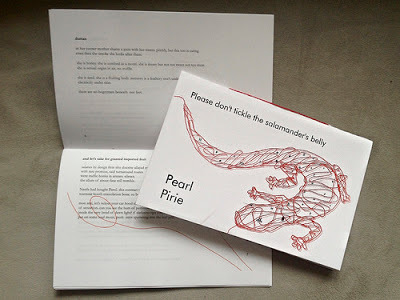

Ottawa ON: The recent crew at In/Words have been producing like mad lately, including a new chapbook by Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, her Please don’t tickle the salamander’s belly (2015). I’ve long been an admirer of Pirie’s lines, the meandering questions she moves through in a kind of collage-manner of thought and phrase, stitching together the most curious of through-lines in what otherwise might be seen as a concordance of semi-randomness. The mind seeks out patterns, and Pirie manages that tension in a most unusual way, similar to work by Perth, Ontario poet Phil Hall for its curious turns, language-play and meditative stretches.

our eyes have opened

for this we sing you our peeps, electric mother:the fence of your heat saves us from deep winter.electric father, we are hungry in our pin-feathers.your blender song comforts, regurgitate us fruit.electric mother, we cowbirds are still flightless.oven-divine pre-digest our grain, and feed us.we have no egg-teeth, flood us another valley,build another coal plant for we have great need.

Published on April 05, 2016 05:31