Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 347

April 24, 2016

Ongoing notes: late April, 2016

Given our new baby distractions, I thought it might be worth going back through the past few months and acknowledging the books over the past two years-plus that I started to review, but, for whatever child-related reason, I wasn’t able to complete as a longer, full-sized review. Here are some notes, if not even regrets, on a couple of books that I wish I’d more time and attention to properly discuss (as they each, obviously, deserve).

Given our new baby distractions, I thought it might be worth going back through the past few months and acknowledging the books over the past two years-plus that I started to review, but, for whatever child-related reason, I wasn’t able to complete as a longer, full-sized review. Here are some notes, if not even regrets, on a couple of books that I wish I’d more time and attention to properly discuss (as they each, obviously, deserve).Kiki Petrosino, Hymn for the Black Terrific: American poet Kiki Petrosino’s second trade poetry collection, Hymn for the Black Terrific (Louisville KY: Sarabande Books, 2013) is part of a vibrant, aural tradition of poetry that can’t help but lift itself from the page. Her poems run the range of questioning, arguing and speaking clearly, and are best experienced out loud, in a collection where her voice is clearly there, inside your head. This is truly a remarkable collection by a remarkable poet.

Ariana Reines, Mercury: There aren’t that many 240 page-plus contemporary poetry collections, but American poet Ariana Reines manages such for her third trade collection,

Mercury

(New York NY: Fence Books, 2011). The author of The Cow (Alberta Prize/Fence Books, 2006) [see my review of such here] and Coeur De Lion (Fence Books, 2007), Reines’ Mercury, with its silver reflective cover, is an expansive, sexual, highly charged and even perverse collection, collecting five incredible sections: “LEAVES,” “SAVE THE WORLD,” “WHEN I LOOKED AT YOUR COCK MY IMAGINATION DIED,” “MERCURY” and “O.” There is something about Reines’ new collection I haven’t seen in serious poetry before, that level of personal, physical and sexual openness, and the text rocks with a physical urgency that propels the poem forward. Her second section, “SAVE THE WORLD,” is composed as an essay/rant against the film The Watchmen (2009), and its conflation of sex and violence, as she writes:

Ariana Reines, Mercury: There aren’t that many 240 page-plus contemporary poetry collections, but American poet Ariana Reines manages such for her third trade collection,

Mercury

(New York NY: Fence Books, 2011). The author of The Cow (Alberta Prize/Fence Books, 2006) [see my review of such here] and Coeur De Lion (Fence Books, 2007), Reines’ Mercury, with its silver reflective cover, is an expansive, sexual, highly charged and even perverse collection, collecting five incredible sections: “LEAVES,” “SAVE THE WORLD,” “WHEN I LOOKED AT YOUR COCK MY IMAGINATION DIED,” “MERCURY” and “O.” There is something about Reines’ new collection I haven’t seen in serious poetry before, that level of personal, physical and sexual openness, and the text rocks with a physical urgency that propels the poem forward. Her second section, “SAVE THE WORLD,” is composed as an essay/rant against the film The Watchmen (2009), and its conflation of sex and violence, as she writes: This movie is about evilWhat its woman wantsIs love and respectShe does not care that the world is endingAnd that the superhuman man is trying to save the evil worldFor humanitarian reasons. He is not paying attention to her.She wants loveAnd respect.She wants his thoughts.

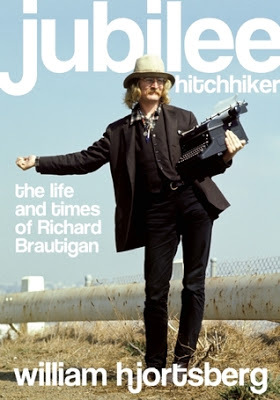

Jubilee Hitchhiker: the life and times of Richard Brautigan, William Hjortsberg: After years of rumours, William Hjortsberg’s incredibly detailed biography of the late American writer Richard Brautigan was released a few years back, the 852 page Jubilee Hitchhiker: the life and times of Richard Brautigan (Berkeley CA: Counterpoint, 2012). And, after three long months, I have finally finished reading it. In Hjortsberg’s biography, the detail is absolutely incredible. In working up to talking about Brautigan’s association with the hippie period of Haight-Ashbury, a whole chapter is dedicated to providing a backdrop, with the same treatment given to the earlier period of the Berkeley Renaissance. Brautigan managed to become a leading figure in American writing [see a recent piece I wrote on his work here], called “the last of the Beat poets,” connecting the beat writers to further literary and cultural movements, including the Diggers and Hippies (he was part of the former, but less the latter). One of the most striking, and thoroughly-researched, biographies I’ve read, this is a fantastic biography of an American writer often dismissed by serious readers unable to read past the surface elements of his ‘hippie-surrealism,’ misunderstanding the depth of his work, and the place he should hold as one of the most original American writers of the second half of the twentieth century.

Jubilee Hitchhiker: the life and times of Richard Brautigan, William Hjortsberg: After years of rumours, William Hjortsberg’s incredibly detailed biography of the late American writer Richard Brautigan was released a few years back, the 852 page Jubilee Hitchhiker: the life and times of Richard Brautigan (Berkeley CA: Counterpoint, 2012). And, after three long months, I have finally finished reading it. In Hjortsberg’s biography, the detail is absolutely incredible. In working up to talking about Brautigan’s association with the hippie period of Haight-Ashbury, a whole chapter is dedicated to providing a backdrop, with the same treatment given to the earlier period of the Berkeley Renaissance. Brautigan managed to become a leading figure in American writing [see a recent piece I wrote on his work here], called “the last of the Beat poets,” connecting the beat writers to further literary and cultural movements, including the Diggers and Hippies (he was part of the former, but less the latter). One of the most striking, and thoroughly-researched, biographies I’ve read, this is a fantastic biography of an American writer often dismissed by serious readers unable to read past the surface elements of his ‘hippie-surrealism,’ misunderstanding the depth of his work, and the place he should hold as one of the most original American writers of the second half of the twentieth century.

Published on April 24, 2016 05:31

April 23, 2016

Sandra Doller and Ben Doller, The Yesterday Project

Yesterday yesterday started. Movement in the bed, chronological. Fast morning and warm tea, getting colder in the carafe. A new project, a reality show. Each day, a performance of living. Each record, a matter. This is what it’s like to be here.

In collage there was a younger girl with attention problems who made a photography art project called “This is what it’s like in here” showing how sad it was to be her, sad little negligee and fake blood and sorry eyes. I always hated that line, that direction, that girl. Pity the animal.

This is what. Westerns with Joseph Cotton and Gary Cooper and the Preston Sturges actor who survived. No popcorn. Raw goji berry chocolate pieces. Cauliflower steak and tofu steak and wild rice and spinach salad. Lentil soup. Egg frittata with red peppers. Flavor tray. Gertrude Stein and Maria Damon. Bob Kauffman. Fanny Howe at the end of it all, her wild childhood now in pieces.

I emailed the doctor who didn’t get the slides of your original lesion, no word on the real diagnosis, no word on. (“July 18, 2014”)

As the press release to Sandra Doller and Ben Doller’s collaborative prose-work

The Yesterday Project

(Sidebrow Books, 2016) informs: “The Yesterday Projectfinds Ben Doller and Sandra Doller undertaking a seemingly simple, stripped-down, though thoroughly brave and highly personal blind collaboration. Each separately wrote a document recording the previous day, every day, for 32 days, without sharing their work over the summer of 2014 in the shadow of a diagnosis of life-threatening illness: Melanoma cancer, Stage 3. The resulting work is a declaration of dependence—a relentlessly honest chronicle of shared identity and the risks inherent in deep connection.”

As the press release to Sandra Doller and Ben Doller’s collaborative prose-work

The Yesterday Project

(Sidebrow Books, 2016) informs: “The Yesterday Projectfinds Ben Doller and Sandra Doller undertaking a seemingly simple, stripped-down, though thoroughly brave and highly personal blind collaboration. Each separately wrote a document recording the previous day, every day, for 32 days, without sharing their work over the summer of 2014 in the shadow of a diagnosis of life-threatening illness: Melanoma cancer, Stage 3. The resulting work is a declaration of dependence—a relentlessly honest chronicle of shared identity and the risks inherent in deep connection.” I’ve long been fascinated by response projects (or as theirs is, a “parallel project”) such as these, produced by couples who also write individually: Sandra Dollar’sbooks include Oriflamme (Ahsahta Press, 2005), Chora (Ahsahta Press, 2010) [see my review of such here], Man Years (Subito Press, 2011) and Leave Your Body Behind (Les Figues, 2015) [see my review of such here], and Ben Doller’s books include Dead Ahead (Louisiana State University Press, 2001), FAQ (Ahsahta Press, 2009), Radio, Radio (Fence Books, 2010) and FAUXHAWK (Wesleyan University Press, 2015) [see my review of such here]. As far as other poet-couples working on conjoined projects, one could point to Robert Kroetschand Smaro Kamboureli, as she composed her travel journal, in the second person (Longspoon, 1985), and he composed his Letters to Salonika (Grand Union Press, 1983) as epistolary in direct response to her absence, or even Daphne Marlatt and Betsy Warland’s Two Women in a Birth(Guernica Editions, 1994), Patrick Lane and Lorna Crozier’s No Longer Two People (Turnstone Press, 1979) and Roo Borson and Kim Maltman’s The Transparence of November/Snow (Quarry Press, 1985) (Christine and I have been slowly working on our own, which we discussed here). In an interview posted at The Rumpus in November,2015, the Dollers talk about their collaborative project, and their crafting of an “androgynous shared identity”:

The Rumpus:How did the idea for this project come about?

Ben Doller:We were in a rough patch, as the book makes clear. I had been diagnosed with cancer (stage III melanoma), and our world suddenly looked very different. It was difficult to see the significance of writing amidst the shock and despair, and I think Sandra decided at some point that perhaps a collaborative, ritualized project could benefit us both in different ways. We had significantly and rapidly changed our lifestyle, and there was a desire to buy into homeopathic remedies and cures. I’ve never been a meditative sort—most of my writing is anxiety driven. I think that Sandra thought this project could be a sort of Trojan Horse to trick me into a more meditative approach to creative practice and, in turn, life.

Sandra Doller: The answer above is interesting to me. The way this project is. I like to hear the secret thoughts of my constant companion. Even if we think we’re communicating everything, we’re not. There’s always some surprise in the revelation, the articulation. I don’t remember it that way. Not exactly. I suppose factually—I did decide we had to do this. It’s a way of being alive.

Rumpus: There must be something fascinating about reading the secrets of the person you know best, even if those secrets are perceptions of your shared days together. Ben, your last name used to be Doyle, and Sandra, yours was Miller, right? How did you get the idea to meld your last names? Why was this important for you?

Sandra: We’d been together/married (same thing) for two years and when we moved to California we made a new name. We like to practice androgynous shared identity. This is ongoing. Although when Ben got sick, I had to realize we don’t share a body. And now, pregnant as I am, that is apparent in every way. We share a body and we don’t. We share a name yet people still assume I took his. My father addresses my mail to Mrs. John Benjamin Doller, which makes me lethal.

The Yesterday Project is actually their second collaboration, after The Sonneteers (Editions Eclipse, 2014), and where that earlier work (composed a decade or so prior to this current work) was a far more direct collaboration, this new project was composed as two distinct threads composed side-by-side, without either reading what the other had written. What makes the combination of the two threads curious is in seeing the parallels that float through such, as they both respond to their shared previous days, one after another, including their unspoken moments, shared outings and day to day tasks, and shared and individual responses and anxieties around Ben’s threatened health. Given there are two in a shared space writing concurrently, the project becomes an intriguing memory project, articulating the different perspectives, what either recall, and how, and what either might choose to highlight from the immediate day prior. The book also includes a series of wonderfully mundane details, from cooking, reading and simply being, some of which reveal the most astounding insight, and at other times, become almost self-conscious (“There are so many things I forgot to put in the yesterdays that would probably make better news.”).

I find it curious, also, that their prose styles match so closely, with only the occasional note or detail reminding which authored which piece (although Ben appears to compose his pieces with far fewer paragraph breaks, and both wrote their date/titles in different formats), which, according to the interview, was entirely deliberate on their part, stripping away their own individual styles. As they collaboratively respond: “And we did shoot for no tone. We talked a few times about writing in a not-trying-to-write kind of way. Not being clever, cute, sound-based, punny, poetic, or engaging any of our familiar writing habits or tics. This was difficult, but I think it changed writing for both of us in a permanent way. Just documenting. Just the facts. Though there is no such thing.”

Yesterday was the day that we met a person. She had a hot tub that her grandmother had handed down to her at her wedding, and it sat on her back porch for three years and now she had a baby and she wanted it cleared out. She was selling it real cheap, 175 dollars, and we found her on Craigslist. I think it was around noon or one o’clock. Previously we had eaten a smoothie and, I believe, some leftover rice and beans. I almost wrote rhythm and blues. Do I only know two songs that repeat yesterday predominantly, The Beatles and The Cure? The woman lived in Yukka Valley and her puppy had chewed on the side of the hot tub. It was enormous. It takes 20 minutes to get from Yukka from our place. Each corner was missing wooden slats that covered the tub guts. But the rest looked clean, very clean, except for the dusty top, which was very nice actually, under the grime, and underneath, which was filled with detritus. I could tell you wanted it. The woman was young, but she had a baby, and her husband had told her they couldn’t afford the $400 to hook the tub up. I could tell I wanted it. Too good of a deal, too great for our place in the desert, under the deep skies, soaking in warm water, listening to the coyotes cry. (“08.12.2014”)

Given their looming health crisis, there is an obvious anxiety that threads itself through their collaboration (the largest, admittedly, of a number of anxieties that run through the book, including: “I am trying to be better. I am trying to see people.”), one that most likely opens up the possibility for a deeper level of intimacy in composing the two sides of their conversation (and, despite the fact that pieces weren’t read by the other, these are pieces directed at each other, which make them very much a conversation; simply because the texts weren’t read doesn’t mean they weren’t communicating). This book might not have been originally intended for publication, but make for an incredibly deep and rich conversation between their private and public selves, both individually and together.

Yesterday we spoke a bit about this project, but later in the day, about who it could possibly be for, about the obligation, the vacancy, the things that are left out. Everything is left out. We do have sex. We do get mad. The project is not a project in complete transparency, rather, one in willful obfuscation. But we haven’t decided this. The first rule of yesterday is no talking about the yesterday. We shied away from it. I was pissed to have to go over it again, a day with family, a day with so many banal frustrations, none that I wanted to elucidate. But that was later in the day. Earlier we woke, and started getting ready to see my parents off. First plan was breakfast at Great Maple. My dad starting texting a bit early, I think they were worried about making it to the airport in time. I texted back, be there in half an hour. They had already pulled their car out when we got there, there was some anxiety. There was plenty of time. (“08.05.2014”)

Published on April 23, 2016 05:31

April 22, 2016

U of Alberta writers-in-residence interviews: Marilyn Dumont (2000-01)

For the sake of the fortieth anniversary of the writer-in-residence program (the longest lasting of its kind in Canada) at the University of Alberta, I have taken it upon myself to interview as many former University of Alberta writers-in-residence as possible [see the ongoing list of writers here]. See the link to the entire series of interviews (updating weekly) here.

Marilyn Dumont’s first collection,

A Really Good Brown Girl

, won the 1997 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award presented by the League of Canadian Poets. This collection is now a Brick Books Classic 2015. Selections from this first collection are widely anthologized in elementary, secondary and post-secondary literary texts, and is now in French translation from Les editions Hannenorak Press. Her second collection,

green girl dreams Mountains

, won the 2001 Stephan G. Stephansson Award from the Writer’s Guild of Alberta. Her third collection,

that tongued belonging

, was awarded the 2007 McNally Robinson Aboriginal Poetry Book of the Year and the McNally Robinson Aboriginal Book of the Year.

The Pemmican Eaters

– her newest collection – is published by ECW Press, 2015. Marilyn has been the Writer-in-Residence at the Edmonton Public Library, the Universities of Alberta, Brandon, Grant MacEwan, Toronto-Massey College, and Windsor. She has been faculty at the Banff Centre in programs such as Writing with Style and Wired Writing and she has advised and mentored in the Aboriginal Emerging Writers’ Program. She serves as a board member on the Public Lending Rights Commission of Canada, and freelances for a living.

Marilyn Dumont’s first collection,

A Really Good Brown Girl

, won the 1997 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award presented by the League of Canadian Poets. This collection is now a Brick Books Classic 2015. Selections from this first collection are widely anthologized in elementary, secondary and post-secondary literary texts, and is now in French translation from Les editions Hannenorak Press. Her second collection,

green girl dreams Mountains

, won the 2001 Stephan G. Stephansson Award from the Writer’s Guild of Alberta. Her third collection,

that tongued belonging

, was awarded the 2007 McNally Robinson Aboriginal Poetry Book of the Year and the McNally Robinson Aboriginal Book of the Year.

The Pemmican Eaters

– her newest collection – is published by ECW Press, 2015. Marilyn has been the Writer-in-Residence at the Edmonton Public Library, the Universities of Alberta, Brandon, Grant MacEwan, Toronto-Massey College, and Windsor. She has been faculty at the Banff Centre in programs such as Writing with Style and Wired Writing and she has advised and mentored in the Aboriginal Emerging Writers’ Program. She serves as a board member on the Public Lending Rights Commission of Canada, and freelances for a living.

She was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 2000-01 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you were about to publish your second poetry collection. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: When I began the residency, I felt very much like a novice and was quite anxious returning to my old English Department. The opportunity was a total surprise to me and as a young writer, I welcomed it because it affirmed my identity as writer.

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Were you working on anything specific while there, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: Previous to my time as WIR at U. of A, I had lived in Vancouver while doing my MFA, and returning to Edmonton provoked a profound sense of coming home, not only to a recognition of Metis culture and history, but I felt like I had come home to the light of the prairie which I had forgotten about. I had also returned to a place that held my personal history and the history of many more Metis whose history like mine was resting quietly below the Eurocentrism.

Q: What do you see as your biggest accomplishment while there? What had you been hoping to achieve?

A: I felt like I was in a period of gestation for a collection focusing on the resilience and resourcefulness of Aboriginal women.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? Were there any encounters that stood out?

A: Since it was my first residency, I stayed within the conventions of Writer in Residence of keeping office hours and public readings. But I do recall, an incident with a young Aboriginal woman who broke down in my office. We were discussing her writing , and she just started crying. I’m not sure if either of us knew why she was crying, but I comforted her the best I could and then she was gone into the crowd of students traversing campus. Over ten years later she recounted that story to me and I recognized her. In the interim years I had forgotten what the young Aboriginal woman sitting in my office looked like, and this woman was now in my circle of friends but hadn’t known it. I do remember feeling sisterly whenever I’d see her, but it’s strange how life repeats itself.

Marilyn Dumont’s first collection,

A Really Good Brown Girl

, won the 1997 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award presented by the League of Canadian Poets. This collection is now a Brick Books Classic 2015. Selections from this first collection are widely anthologized in elementary, secondary and post-secondary literary texts, and is now in French translation from Les editions Hannenorak Press. Her second collection,

green girl dreams Mountains

, won the 2001 Stephan G. Stephansson Award from the Writer’s Guild of Alberta. Her third collection,

that tongued belonging

, was awarded the 2007 McNally Robinson Aboriginal Poetry Book of the Year and the McNally Robinson Aboriginal Book of the Year.

The Pemmican Eaters

– her newest collection – is published by ECW Press, 2015. Marilyn has been the Writer-in-Residence at the Edmonton Public Library, the Universities of Alberta, Brandon, Grant MacEwan, Toronto-Massey College, and Windsor. She has been faculty at the Banff Centre in programs such as Writing with Style and Wired Writing and she has advised and mentored in the Aboriginal Emerging Writers’ Program. She serves as a board member on the Public Lending Rights Commission of Canada, and freelances for a living.

Marilyn Dumont’s first collection,

A Really Good Brown Girl

, won the 1997 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award presented by the League of Canadian Poets. This collection is now a Brick Books Classic 2015. Selections from this first collection are widely anthologized in elementary, secondary and post-secondary literary texts, and is now in French translation from Les editions Hannenorak Press. Her second collection,

green girl dreams Mountains

, won the 2001 Stephan G. Stephansson Award from the Writer’s Guild of Alberta. Her third collection,

that tongued belonging

, was awarded the 2007 McNally Robinson Aboriginal Poetry Book of the Year and the McNally Robinson Aboriginal Book of the Year.

The Pemmican Eaters

– her newest collection – is published by ECW Press, 2015. Marilyn has been the Writer-in-Residence at the Edmonton Public Library, the Universities of Alberta, Brandon, Grant MacEwan, Toronto-Massey College, and Windsor. She has been faculty at the Banff Centre in programs such as Writing with Style and Wired Writing and she has advised and mentored in the Aboriginal Emerging Writers’ Program. She serves as a board member on the Public Lending Rights Commission of Canada, and freelances for a living.She was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 2000-01 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you were about to publish your second poetry collection. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: When I began the residency, I felt very much like a novice and was quite anxious returning to my old English Department. The opportunity was a total surprise to me and as a young writer, I welcomed it because it affirmed my identity as writer.

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Were you working on anything specific while there, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: Previous to my time as WIR at U. of A, I had lived in Vancouver while doing my MFA, and returning to Edmonton provoked a profound sense of coming home, not only to a recognition of Metis culture and history, but I felt like I had come home to the light of the prairie which I had forgotten about. I had also returned to a place that held my personal history and the history of many more Metis whose history like mine was resting quietly below the Eurocentrism.

Q: What do you see as your biggest accomplishment while there? What had you been hoping to achieve?

A: I felt like I was in a period of gestation for a collection focusing on the resilience and resourcefulness of Aboriginal women.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? Were there any encounters that stood out?

A: Since it was my first residency, I stayed within the conventions of Writer in Residence of keeping office hours and public readings. But I do recall, an incident with a young Aboriginal woman who broke down in my office. We were discussing her writing , and she just started crying. I’m not sure if either of us knew why she was crying, but I comforted her the best I could and then she was gone into the crowd of students traversing campus. Over ten years later she recounted that story to me and I recognized her. In the interim years I had forgotten what the young Aboriginal woman sitting in my office looked like, and this woman was now in my circle of friends but hadn’t known it. I do remember feeling sisterly whenever I’d see her, but it’s strange how life repeats itself.

Published on April 22, 2016 05:31

April 21, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tony Iantosca

Tony Iantosca is a person who writes poems and teaches English composition and creative writing at Borough of Manhattan Community College. Poems have appeared in 6x6, Lungfull!, ThoseThatThis, Death and Life of Great American Cities, a Perimeter, among others. His first full-length collection of poems,

Shut Up, Leaves

was published by United Artists Books in November 2015. Previous collections include

Team Burnout

(Overpass Books) and

Naked Forest Spaces

(Third Floor Apartment Press). He holds an MFA from Long Island University in Brooklyn.

Tony Iantosca is a person who writes poems and teaches English composition and creative writing at Borough of Manhattan Community College. Poems have appeared in 6x6, Lungfull!, ThoseThatThis, Death and Life of Great American Cities, a Perimeter, among others. His first full-length collection of poems,

Shut Up, Leaves

was published by United Artists Books in November 2015. Previous collections include

Team Burnout

(Overpass Books) and

Naked Forest Spaces

(Third Floor Apartment Press). He holds an MFA from Long Island University in Brooklyn.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook helped me begin to think of single poems as part of a larger project, and then to think of what that larger project's main concerns are and how to work with and sometimes against those concerns. Other times I try to write poems that make fun of the tendencies that I see in my own writing and interests. But none of that would have been possible without seeing the poems presented as a book. It makes palpable and literal something I tell students all the time, which is that they should look at their writing in the third person. With my most recent full-length book, Shut Up, Leaves, it felt good to make use of the process I'd used in compiling poems for smaller chapbooks

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I first came to poetry during high school. I was part of the creative writing club in my high school. I'm not sure what attracted me to poetry as opposed to another genre, but I had some very dear friends in the creative writing club. It was generally the student club that more punks and hippies joined, so I liked it for that reason too.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I don't generally set out to start a writing project. I normally decide after I've accumulated a handful of similar poems that any given project should continue and expand. It's interesting to see how all of the reading I do--which is by no means limited to poetry--can begin to shape the concerns I grapple with in the composition of a new set of poems. It takes quite a long time for me to know if the final shape of a poem should resemble the lines written hurriedly in a notebook, or if I should isolate and foreground only a few words or sentiments. So sometimes the final looks identical to the mess in the notebook, whereas other times everything's been rearranged, often because I'm trying to fine tune the lines to be identical to the poems which came out right the first time.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

More recently, the poem begins with speech. I'm interested in how speech can become unmoored from its original context and setting. It's hard to generalize about whether or not short pieces become longer ones, or vice versa, but most recently my poems exist as parts of a larger series. The long or serial poem helps me figure out how many different ways there are to express the same idea. As a lot of my poetry deals with received ideas about the world, this can mean that I take notes on stray phrases I hear on the street, or that I work through outlining a literary trope in the abstract and try to make it sound a little off. I used to do much more compiling, but even then I feel like I must have been writing the same poem a million times in a row.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings, though recently I haven't been doing that many. Last year I didn't attend that many readings either (I needed a break) so that might have something to do with it. Public readings are definitely a part of my creative process. They help me hear what's working and what isn't, but so do one-on-one meetings I have with friends who've been kind enough to read what I'm working on and tell me what they think. I'd also say that hearing my friends give readings is helpful, somehow, though I'm not sure how. Maybe because it keeps me in touch with the greater poetry scene in New York.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Many of my poems retell familiar narratives, but do so in a way that attempts to call attention to the assumptions present in those narratives. In doing this, the reader might be able to examine what types of cultural assumptions exist in American literature as a whole, and they might be able to ask how that reflects on our world and where we are now. I'm referring to assumptions about the supremacy of the individual in our society, and how that tendency may seep into the figure of the author or the singular protagonist in our literature. Often when one articulates what a speaker or author assumes about reality it can sound totally insane. Other poems articulate tendencies that may exist instead only in a societal or political narrative (as opposed to in literature). How can I as an author inhabit such ways of making meaning while also defacing them? In the midst of such concerns I still try to show, or reveal, a subjectivity behind these broad narratives and assumptions, and that's me and my actual worries and concerns and heartbreaks. Hopefully that prevents a reading that sees these cultural tendencies as totalizing.

But those are only the most recent concerns. I have other projects that attempt to say exactly what I mean in a way that escapes the idea of the poem--plain unadorned speech. Some poems in Shut Up, Leaves are very emotional but try to keep sentimentality at bay. As I mentioned before, it's worth it to make fun of feelings while expressing those feelings at the same time.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

It's both the larger culture's task to figure that out and the writer's. I really think that poets in particular should not think of poetry or the poetry community as an inaccessible, specialized domain, even if that's comfortable for us. Doing so reinforces the isolation from the larger culture that writers often feel and sometimes disingenuously bemoan. At the same time, changing the larger culture and all its problems is a process that would necessarily change the poetry being written within that supposed culture or "subculture." I think both should happen so that we can one day teach poetry to people starting from preschool. Maybe that way I would never have to hear another person say "I don't get poetry."

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It is essential. I've been meeting intermittently with the poet Lisa Rogal at this place in Brooklyn called Junior's. We have a beer and exchange long poems and help each other find ways of structuring them. We've both been working on long poems recently, so it's a particularly good match. She's been a huge help.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Once you've accumulated a whole bunch of writing that you know works well, go back and read it and figure out why it works well.

Another great piece of advice is to try to undermine comfortable tendencies that you have in your writing as you're writing something new. If you feel yourself wanting to write a line, try thinking and writing the opposite of that line. I've found this helpful for myself because it opens up some other space, other ways of seeing, that never would have occurred to me. I forget who told me this originally. It was probably Lewis Warsh.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Unfortunately I don't have a typical writing routine. I can go a long time without writing, which both helps and hurts. A typical day begins with me waking up and eating granola, listening to the news, and looking out the window. After that I get on my bike and go to teach or plan a lesson or tutor someone. In between classes or tutoring sessions, there's often a lot of time. Sometimes something comes to me during those intervals, and sometimes this will happen every day for a week and then abruptly stop.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

If that happens, I make myself write and make myself accept the fact that whatever comes out is likely going to suck for a little while, at least until I can get back into some kind of practice. I go back pretty often to Bernadette Mayer's Desires of Mothers to Please Others in Letters. I also like to return to Today I Wrote Nothing by Daniil Kharms (translated by Matvei Yankelevich). Something about those two books reminds me how many possibilities are available to writing, even if both authors are working with very different concerns.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Old rugs.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Many of my friends are painters and many are musicians, still others study philosophy. Conversations with them about their own work influence me tremendously, even though I probably can't name directly the way that influence happens.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I'm reading an excellent book by my friend Bruno Gulli called Labor of Fire. It's been helpful to think of writing and poetry as labor, and not to think of labor as a concept limited or restricted by economic structures, but as something that precedes and exceeds those structures.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I'd like to go into one of those caves carved out by the ocean.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

If I could pick any other occupation, I'd like to be the park ranger in a public park in a city somewhere. I think it would be nice to spend that much time outside. Also that way I could let people get away with all sorts of activities that are prohibited in public parks at the moment. But maybe that would get me fired.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I wrote a paper in college about the hip hop duo Pete Rock and CL Smooth. I wrote about their hit song "They Reminisce Over You (T.R.O.Y.)." The teacher loved the essay and told me I should major in writing. At the time I wanted to become a professional activist, but I figured there were other ways of doing that and being a writer at the same time. Writing essays was also a lot of fun, and then as time went on I began to take poetry much more seriously.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book was called Story of the Lost Child , the last in Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan series. I think it's the best of the four books by Ferrante, especially the section about the author's experience of the 1980 Irpinia earthquake. Also, Matvei Yankelevich's Some Words for Dr. Vogt, recently out from Black Square Editions, is great. I also read George Oppen's Of Being Numerous, which I'm told is related to Matvei's book somehow. All of these have been important books, and I imagine I'll go back to them quite a bit over the years.

I saw a good film about the vigilante groups in Michoacan, Mexico. They arose to combat both the state police and armed forces and the drug cartels. It was ultimately a failed project led by a pediatric doctor who decided to arm his community, and the director does a nice job making sure the audience feels no allegiance to anyone.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Most recently, I've been working on a set of poems under the heading "Bad Poetry." These poems tackle political issues that arise in everyday life. I'm interested in whether it's possible for me to write an overtly political poem, and whether that poem can pose as a bad poem (by feeling unedited, or lazy) while still somehow working. It's hard to fake laziness and it's equally hard to make a poem have a message without the poem being kind of boring. So the poems take lots of editing. Maybe they'll never be published, and maybe there's a good reason for that, but I think it's important for me to play with text in this really difficult way if only to keep the broader experiments outside of this project moving along.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on April 21, 2016 05:31

April 20, 2016

rob mclennan interviewed by Oscar Martens

I was interviewed last week by Vancouver writer Oscar Martens, now posted up on his blog. Much thanks!

I was interviewed last week by Vancouver writer Oscar Martens, now posted up on his blog. Much thanks!I've actually been recently collecting a series of links to a variety of online interviews with me, here.

Published on April 20, 2016 05:31

April 19, 2016

Introducing: Aoife Lydia Judith McLennan, b. April 16

Our new little girl, Aoife [“eee-fah”] Lydia Judith McLennan, was born Saturday, April 16 at 2:21pm at Ottawa’s Montfort Hospital. Due on April 18th(or 21st, depending on which version you believe), our little Aries arrived after a quick (precipitous) 2 hour birth at 8lbs 9.9oz and 19 ¾ inches long (head c. 36.5cm).

Our new little girl, Aoife [“eee-fah”] Lydia Judith McLennan, was born Saturday, April 16 at 2:21pm at Ottawa’s Montfort Hospital. Due on April 18th(or 21st, depending on which version you believe), our little Aries arrived after a quick (precipitous) 2 hour birth at 8lbs 9.9oz and 19 ¾ inches long (head c. 36.5cm). We very much thank our midwife Maxine and Marika from the Midwifery Group of Ottawa, doula Pia Anderson (who was heroic) and the hospital staff at the Montfort for all their help and support. And photographer Kim Brooks at Breathe In Photography!

Aoife is the fourth grandchild on the McNair side, and the sixth (and final!) grandchild on the McLennan side, providing a new sister for toddler Rose [see her birth notice here], a second half-sibling for big sister Kate, as well as a new cousin for Emma, Rory and Duncan (on the McLennan side) and Duncan and Adelaide (on the McNair side). So many cousins!

Aoife is the fourth grandchild on the McNair side, and the sixth (and final!) grandchild on the McLennan side, providing a new sister for toddler Rose [see her birth notice here], a second half-sibling for big sister Kate, as well as a new cousin for Emma, Rory and Duncan (on the McLennan side) and Duncan and Adelaide (on the McNair side). So many cousins!Curious to me, that now Christine and her brother (so far) each have two children, and my sister and I each have three children (and, another three days, and our Aoife would have shared a birthday with my dear sister).

Aoife:how does one reconcile an Irish first name with a Scottish surname? There’s Irish on the McNair side, so it’s fine, really. When researching the name, I became quite partial to Aoife MacMurrough (c.1145–1188), who often fought on behalf of her husband, Strongbow. MacMurrough was sometimes known as Red Eva (Irish: Aoife Rua) (which make me hope our Aoife might have some of the red tint that threads through the McNair line). Her descendants include “all the monarchs of Scotland since Robert I (1274-1329) and all those of England, Great Britain and the United Kingdom since Henry IV (1367-1413); and, apart from Anne of Cleves, all the queen consorts of Henry VIII.”

Aoife:how does one reconcile an Irish first name with a Scottish surname? There’s Irish on the McNair side, so it’s fine, really. When researching the name, I became quite partial to Aoife MacMurrough (c.1145–1188), who often fought on behalf of her husband, Strongbow. MacMurrough was sometimes known as Red Eva (Irish: Aoife Rua) (which make me hope our Aoife might have some of the red tint that threads through the McNair line). Her descendants include “all the monarchs of Scotland since Robert I (1274-1329) and all those of England, Great Britain and the United Kingdom since Henry IV (1367-1413); and, apart from Anne of Cleves, all the queen consorts of Henry VIII.” We’ve already had half a dozen requests for pronunciation. It might not be as common in North America, but in 2003, it was the third most popular Irish girls name for babies in Ireland.

Lydia is Christine’s mother’s middle name, a name that also comes from mother-in-law’s maternal grandmother, about whom we know almost nothing (she died of TB in 1939, when mother-in-law’s mother was nine). And yet, do you remember the first episode of The Muppet Show, as Kermit sang that infamous Groucho Marx standard (it was apparently a Jim Henson favourite; the same song was sung at his funeral)? I’ve always been partial to the song as well, honestly.

Lydia is Christine’s mother’s middle name, a name that also comes from mother-in-law’s maternal grandmother, about whom we know almost nothing (she died of TB in 1939, when mother-in-law’s mother was nine). And yet, do you remember the first episode of The Muppet Show, as Kermit sang that infamous Groucho Marx standard (it was apparently a Jim Henson favourite; the same song was sung at his funeral)? I’ve always been partial to the song as well, honestly.Judithcomes from Judith Fitzgerald, who fought like hell against a difficult upbringing (for the whole of her life, it would seem). To have even a fraction of her iron will and survival instinct (sans trauma, obviously) would be a blessing. And: Judith was a friend of mine. See my obituary for her here.

Judith was Christine’s suggestion: for both girls, we’ve aimed for three names in a particular order: name that is only theirs, name from family, and (as Christine has called it), aspirational name. After reading Fitzgerald’s obituary, Christine was impressed by her resilience, and suggested we consider it for our list. I immediately agreed.

Rose has mostly managed the name correctly, but at least a couple of times has called her (among other things) “Ooo-fah.”

As of Sunday night, all are home, and all are doing well, if a bit hazy in places.

Published on April 19, 2016 05:31

April 18, 2016

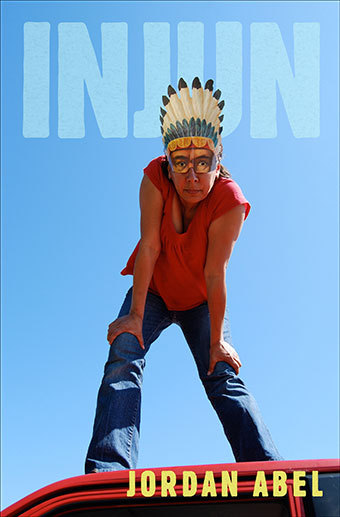

Jordan Abel, Injun

a)

he played injun in gods countrywhere boys proved themselves clean

dumb beasts who could cut fireout of the whitest sand

he played english across the trailwhere girls turned plum wild

garlic and strained wordsthrough the window of night

he spoke through numb lips andbreathed frontier (“injun”)

The first work I encountered by Vancouver poet Jordan Abel was blind, as part of my time judging the 24th annual Short Grain Competition for Saskatchewan’s Grain magazine in 2012(he came in second), and the work leapt up at me in a way I’ve rarely experienced. Now some of that same work finally appears in a trade collection, his third—Injun (Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2016)—after The Place of Scraps (Talonbooks, 2013) [see my review of such here] and Un/inhabited (Talonbooks/Project Space Press, 2014) [see my review of such here]. Injun extends Abel’s remarkable series of reclamation projects (or: project) that bring such a freshness, lively energy and engagement to Canadian and North American poetry, engaged with conversations attached to Idle No More and Truth and Reconciliation, and Language/Conceptual Poetries. Anyone suggesting that conceptual writing has no heart, or that contemporary poetry has exhausted itself, really needs to start engaging with Abel’s work.

b)

he heard snatches of commentgoing up from the river bank

all them injuns is people firstand besides for this buckskin

why we even shoot at themand seems like a sign of warm

dead as a horse friendshipand time to pedal their eyes

to lean out and say the truthall you injuns is just white keys

Abel’s book-length projects open a series of conversations on race, colonization and aboriginal depictions, utilizing settler language and blending an exhaustive research with erasure to achieve an incredible series of inquiries and subversions, twisting racist phrases, ideas and words back in on themselves. In a recent interview posted at Touch the Donkey, Abel wrote: “[…] if your writing is only resistant, only oppositional, only focused on decolonization, you kind of end up writing yourself into a corner. That resistance alone is somehow insubstantial and unsustainable. More or less, this makes a lot of sense to me, and I think it’s exceptionally important to balance out that resistance with presence. Or perhaps balance out decolonization with resurgence.” He continued:

Abel’s book-length projects open a series of conversations on race, colonization and aboriginal depictions, utilizing settler language and blending an exhaustive research with erasure to achieve an incredible series of inquiries and subversions, twisting racist phrases, ideas and words back in on themselves. In a recent interview posted at Touch the Donkey, Abel wrote: “[…] if your writing is only resistant, only oppositional, only focused on decolonization, you kind of end up writing yourself into a corner. That resistance alone is somehow insubstantial and unsustainable. More or less, this makes a lot of sense to me, and I think it’s exceptionally important to balance out that resistance with presence. Or perhaps balance out decolonization with resurgence.” He continued: Primarily, the texts that I’ve focused on as source texts have all been written from a settler-colonial perspective, and, I think, have pointed towards the kinds of foundational knowledges that should be resisted. My challenge, so far, has been to articulate an Indigenous presence from within those texts. TPOS is probably my most accessible example of this. From within Barbeau’s voice comes my own voice, an Indigenous voice. In that resistance and disassembly of Barbeau’s writing an Indigenous presence emerges.

Further, in an October 2014 interview conducted by Elena E. Johnson for Event magazine, Abel discussed the research and erasures that make up the individual book-length components of this ongoing project (specifically, his previous book, Un/inhabited):

Un/inhabited is a study in context. The book itself is draws from 91 Western novels that total over 10,000 pages of source text. Each piece in the book was composed by searching the source text for a specific word that related to the social and political aspects of land use, ownership and property. For example, when I searched for the word “uninhabited” in the source text, I found that there were 15 instances of that word appearing across the 10,000 page source text. I then copied and pasted those 15 sentences that contained the word “uninhabited” and collected them into a discrete unit. The result of this kind of curation is that the context surrounding the word is suddenly visible. How is this word deployed? What surrounds it? What is left over once that word is removed? Ultimately, the book accumulates towards a representation of the public domain as a discoverable and inhabitable body of land.

Abel’s project both engages and works to unsettle, attempting both an ease and unease into the ongoing shame of how aboriginals are treated and depicted in Canada through repetition, erasure and settler language. Simply through usage, Abel forces us, the occupiers, to confront our language, in an effort to reconcile, restore and heal, none of which can truly exist without real conversation. The poems in Injun exist as a single book-length erasure and reclamation project, one with the result of seeing sketched erasures alongside exploded characters that are difficult to replicate within the space of this kind of review. Lines and phrases explode across the page. At the end of Injun, he includes this short “[ PROCESS ],” that writes:

Injun was constructed entirely from a source text comprised of 91 public domain western novels with a total length of just over ten thousand pages. Using CTRL+F, I searched the source text for the word “injun,” a query that returned 509 results. After separating out each of the sentences that contained the word, I ended up with 26 print pages. I then cut up each page into a section of a long poem. Sometimes I would cut up a page into three- to five-word clusters. Sometimes I would rearrange the pieces until something sounded right. Sometimes I would just write down how the pieces fell together. Injun and the accompanying materials are the result of those methods.

Published on April 18, 2016 05:31

April 17, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Teri Vlassopoulos

Teri Vlassopoulos is the author of the short story collection,

Bats or Swallows

(2010), and a novel,

Escape Plans

(2015), both with Invisible Publishing. Her fiction has appeared in Room Magazine,

Joyland

, Little Fiction, and various other North American journals. She is the cookbook columnist for Bookslut, and has had non-fiction published at

The Toast

,

The Millions

and

The Rumpus

. She can be found at http://bibliographic.net or @terki. She lives in Toronto.

Teri Vlassopoulos is the author of the short story collection,

Bats or Swallows

(2010), and a novel,

Escape Plans

(2015), both with Invisible Publishing. Her fiction has appeared in Room Magazine,

Joyland

, Little Fiction, and various other North American journals. She is the cookbook columnist for Bookslut, and has had non-fiction published at

The Toast

,

The Millions

and

The Rumpus

. She can be found at http://bibliographic.net or @terki. She lives in Toronto.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, a collection of short stories called Bats or Swallows, didn’t so much change my life as it did assuage a low grade panic that I would never publish anything. Ever. So, the book helped me relax and taught me that publication isn’t necessarily the end goal. Despite this lesson, a similar existential panic crept up on me anyway while I waited for my second book, a novel called Escape Plans, to get published. It was a little less existential panicky than the first time around, though.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I started off making personal and music zines as a teenager and in my early twenties, but the writing was closer to poetry and fiction than non-fiction. I realized I could address the issues I wanted to work through better in fiction, though, and eventually ended up there.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The spark of an idea and the initial writing come quickly, but the journey to the final product is slow and circuitous. I end up on the scenic route no matter how much advanced planning I do. There are many drafts, many notes.

4 - Where does a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Escape Plans began as short pieces that I glued together into something longer, but then realized the seams were too obvious and had to start all over. It was tedious, and I don’t want to go through the same process again for my next book, but maybe that’s just how I work. Damn it.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I hate reading my writing out loud, and am jealous of writers who enjoy doing readings. That being said, I’ve had fun at pretty much every reading I’ve ever done and always leave thinking I should do more. That feeling quickly fades, apparently, because my first instinct when it comes to readings is, “noooo.”

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’m interested in what we hide from the people we love, not spitefully or maliciously, but unknowingly, because of who we simply are. I’m interested in unspoken bonds. I’m interested in the relationship between food and life. I’m interested in family and marriage and motherhood. These questions and concerns, perhaps banal, perhaps impossibly broad, preoccupy my writing.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I don’t hold the role of the writer differently than any other role in society. Be a good person, whatever that definition is to you, and let your work be a reflection of your interests. (The two don’t need to intersect, though.)

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential! My editors at Invisible Publishing have given me fundamental insight into my work; I’m so grateful.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Grace to be born and live as variously as possible, which is from Frank O’Hara’s poem “In Memory of my Feelings” and is also the epitaph on his gravestone. I would like to apply this to writing, life.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I don’t think about it much; the subject dictates the genre. Sometimes I can only address an issue in a personal essay, sometimes in a novel or short story. My secret is that I want to be able to throw poetry in the mix, but… I’m not quite there yet.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m currently, shakily, trying to establish a writing routine. After a year of maternity leave, I’m now back to working a fairly demanding day job, while also raising a wonderful and energetic toddler with my husband. These days, a typical day does not include any writing other than maybe thinking about it while I drive to work. I welcome advice.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

A handful of writers who’s names are all weirdly similar: Laurie Colwin, Lorrie Moore, Lisa Moore. Also, Geoff Dyer, Marilynne Robinson, Miriam Toews. Also, recently, Elena Ferrante, Heidi Julavits.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

These days, Johnson’s baby lotion, the kind in the pink bottle.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

My books most definitely also come from music, photographs, the view from a car window on a roadtrip, the feeling of seeing a painting in an art gallery, the feeling of sitting in a doctor’s office waiting room, the feeling of wading into the sea.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

See question 12!

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Where do we even start…

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

My day job is already pretty much the complete opposite of a writer: an accountant. It pays better than royalties. It would be nice to be just a writer, though.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I had no choice in the matter! It’s just what I do.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Aforementioned wonderful and energetic toddler means it’s been awhile since I’ve seen a great film (which is also an excuse for the fact that I’m just not a big movie person). But books, there are always great books. Sharon Olds’ first collection of poetry, Satan Says. Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. Barbara Comyns’s Our Spoons Came from Woolworths. Stories from Grace Paley’s The Little Disturbances of Man.

20 - What are you currently working on?

A novel! Ugh! I also write these TinyLetters every two weeks or so: http://tinyletter.com/teri_vlass

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on April 17, 2016 05:31

April 16, 2016

Anne Cecelia Holmes, Dead Year

Dead Year

Tonight I pay attentionto my energetic state.

Reframe, reframe,prickly feelings aside.

I turn on the fireuntil my eyes adjust,

expand to let a pathscorch through all

of me. All of medying in fake light.

I know about steeringtoward forfeit.

Each time I crackI touch the gap between

my lungs. I reachinside my brain,

malleable as it is,and spend a century

slicing its dimensionsuntil it becomes

a map I can trust.

The author of

The Jitters

(horse less press, 2015) [see my review of such here] and the chapbooks

Junk Parade

(dancing girl press, 2012) and I Am A Natural Wonder (with Lily Ladewig; Blue Hour Press, 2011), Western Massachusetts poet Anne Cecelia Holmes’newest poetry book is

Dead Year

(sixth finch books, 2016). Dead Yearis made up of a suite of twenty-eight short lyrics, each of which utilize the same title, claiming (and re-claiming) a safe physical and temporal space. As she writes in the opening poem: “I unfold old terror / until it is a landmark. // Anything wanting / to be born this year // needs more than / an inarticulate feeling.” The poems in Dead Year are powerful in their subtlety, openness and even optimism, with only the thinnest verneer between the surface of the page and an immeasurable depth of rage and grief. On her website, as part of her announcement for the new book, she offered: “These poems are dispatches from abuse and violence and looking for shelter, apologies to unneeded apologies.” In many ways, these poems do feel like epistolary dispatches, little notes composed, not as a cry for help, but for an acknowledgment of what has happened, what is happening, and what comes next, attempting to emerge, rebuilt, on the other end of trauma. The poems in Dead Year are very much an acknowledgment, giving voice to what had not yet been spoken of. To give voice is to make tangible, but it is also allowing the potential for exorcism. As she writes towards the end of the collection: “I reach / inside my brain, // malleable as it is, / and spend a century // slicing its dimensions / until it becomes // a map I can trust.” In her December 15, 2015 “12 or 20 questions” interview, Holmes spoke a bit about the process of working on the manuscript:

The author of

The Jitters

(horse less press, 2015) [see my review of such here] and the chapbooks

Junk Parade

(dancing girl press, 2012) and I Am A Natural Wonder (with Lily Ladewig; Blue Hour Press, 2011), Western Massachusetts poet Anne Cecelia Holmes’newest poetry book is

Dead Year

(sixth finch books, 2016). Dead Yearis made up of a suite of twenty-eight short lyrics, each of which utilize the same title, claiming (and re-claiming) a safe physical and temporal space. As she writes in the opening poem: “I unfold old terror / until it is a landmark. // Anything wanting / to be born this year // needs more than / an inarticulate feeling.” The poems in Dead Year are powerful in their subtlety, openness and even optimism, with only the thinnest verneer between the surface of the page and an immeasurable depth of rage and grief. On her website, as part of her announcement for the new book, she offered: “These poems are dispatches from abuse and violence and looking for shelter, apologies to unneeded apologies.” In many ways, these poems do feel like epistolary dispatches, little notes composed, not as a cry for help, but for an acknowledgment of what has happened, what is happening, and what comes next, attempting to emerge, rebuilt, on the other end of trauma. The poems in Dead Year are very much an acknowledgment, giving voice to what had not yet been spoken of. To give voice is to make tangible, but it is also allowing the potential for exorcism. As she writes towards the end of the collection: “I reach / inside my brain, // malleable as it is, / and spend a century // slicing its dimensions / until it becomes // a map I can trust.” In her December 15, 2015 “12 or 20 questions” interview, Holmes spoke a bit about the process of working on the manuscript:Over the past two years or so, the voice and intent behind my poems have shifted pretty forcefully to a more bodied, female perspective. Like I mentioned before, for a long time I was uncomfortable facing depression, anxiety, trauma, especially related to a personal and societal female experience in my work, even though these ideas and concerns were boiling in me. To that end, I am writing poems investigating how to reconcile these issues—how to be okay with anger, but also working toward hope. Hope is important to me, no matter how sick the world seems or how foolish it feels to still seek it. There are theoretical questions behind this, of course, but it is also impossible for me to separate the theoretical from the personal.

Published on April 16, 2016 05:31

April 15, 2016

U of Alberta writers-in-residence interviews: Tim Lilburn (1999-2000)

For the sake of the fortieth anniversary of the writer-in-residence program (the longest lasting of its kind in Canada) at the University of Alberta, I have taken it upon myself to interview as many former University of Alberta writers-in-residence as possible [see the ongoing list of writers here]. See the link to the entire series of interviews (updating weekly) here.

Tim Lilburn was born in Regina, Saskatchewan. He has published nine books of poetry, including To the River (1999), Kill-site (2003), and Orphic Politics (2008). His work has received Canada’s Governor General’s Award (for Kill-site), the Saskatchewan Book of the Year Award and the Canadian Authors Association Award among other prizes. A selection of his poetry is collected in Desire Never Leaves: the Poetry of Tim Lilburn (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2007). Lilburn has produced two books of essays, both concerned with poetics, eros and politics, especially environmentalism, Living in the World as if It Were Home (1999) and Going Home (2008). His poetry has been translated into Chinese, Spanish, Polish, French, German and Serbian. His most recent book is Assiniboia (2012), an opera for chant in three parts, sections of which have been choreographed and performed by contemporary dance companies in Canada, notably Regina’s New Dance Horizons. He recently collaborated with Edward Poitras and Robin Poitras of New Dance to produce the opera/dance “House of Charlemagne” on the life of Honore Jaxon. A new poetry collection,

He was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 1999-2000 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you were the author of a small handful of books. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: When I went to the U of A, I had published five books, Names of God, Tourist to Ecstasy, From the Great Above She Opened Her Ear to the Great Below, and To the River, all poetry, and a collection of essays called Living in the World As If It Were Home. I was a little at an impasse in my work; I wanted to do something different, to make a shift in how I came at things. The year in Edmonton, working in the writer-in-residence program, gave me a break from my usual life and a freedom to take a good look around. I started writing some of the poems that made up Kill-site during that time.

Q: What was the impasse you were attempting to reconcile? Was it a shift in tone, or the line, or something else?

A: I wanted to find a way to get more political and philosophical content into a poem, without completely breaking out of the lyric gesture, like I had seen mid Nineties poets in Beijing do. To come to something bulkier, more spreading, but still with a driven music and compelling turns.

Q: Was this your first residency?

A: No. I was w-in-r at the U of Western Ontario in 1989-90 and at the Regina Public Library 1998-9, the year before I went to U of A. I also did a short residency at St. Mary’s University in Halifax.

Q: Looking back on the experience now, how did your University of Alberta experience compare to those other residencies?

A: I remember that year in Edmonton fondly. The department gave me a warm welcome. I had an apartment on Saskatchewan Dr., about a thirty minute walk from the university, near the farmers’ market, a jazz club and a couple of good bookstores, which may no longer be there. The residencies at Western and the RPL were also great, open spaces to think about my work outside my normal routine. I enjoyed talks with Kristjana Gunnars, Bert Almon, Doug Barbour and Greg Hollingshead, long walks by the North Saskatchewan, Oilers games.

Q: How did you engage with students during your residency? Were there any that stood out?

A: I visited numerous classes during my year in Edmonton and met, one-on-one, with many students, poets, prose writers, playwrights. Audrey Whitson stands out among those I consulted with. She was working on a manuscript, which was eventually published as Teaching Places, an important book, and one that I have used in my own teaching. I enjoyed that people from outside the university community, like Audrey, came in to see me. I remember people coming from as far away as Hinton. The city and region had embraced the writer-in-residence program and used it. I also taught a weekend non-credit poetry workshop, and I recall writers like Erin Michie from those sessions.

Q: Given the fact that you aren’t an Alberta writer, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while in Edmonton? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: Well, the landscape was very much my own then. I was living in Saskatoon in those days. I liked to get out to a nice series of trails near Camrose, prairie, ponds and sloughs. That would be a good Sunday outing. Then there were the river trails.

I enjoyed the vital poetry scene in the city, The Stroll of Poets, in which Alice Major was deeply involved, readings at the university. I spent quite a bit of time talking to Tim Bowling and Ted Blodgett about poetry in general.

Edmonton was a great book store city back then, but I don’t know what that scene is like now. Book stores seem to evaporate rather quickly. Long afternoons grazing away at Greenwoods.

Tim Lilburn was born in Regina, Saskatchewan. He has published nine books of poetry, including To the River (1999), Kill-site (2003), and Orphic Politics (2008). His work has received Canada’s Governor General’s Award (for Kill-site), the Saskatchewan Book of the Year Award and the Canadian Authors Association Award among other prizes. A selection of his poetry is collected in Desire Never Leaves: the Poetry of Tim Lilburn (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2007). Lilburn has produced two books of essays, both concerned with poetics, eros and politics, especially environmentalism, Living in the World as if It Were Home (1999) and Going Home (2008). His poetry has been translated into Chinese, Spanish, Polish, French, German and Serbian. His most recent book is Assiniboia (2012), an opera for chant in three parts, sections of which have been choreographed and performed by contemporary dance companies in Canada, notably Regina’s New Dance Horizons. He recently collaborated with Edward Poitras and Robin Poitras of New Dance to produce the opera/dance “House of Charlemagne” on the life of Honore Jaxon. A new poetry collection,

He was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 1999-2000 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you were the author of a small handful of books. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: When I went to the U of A, I had published five books, Names of God, Tourist to Ecstasy, From the Great Above She Opened Her Ear to the Great Below, and To the River, all poetry, and a collection of essays called Living in the World As If It Were Home. I was a little at an impasse in my work; I wanted to do something different, to make a shift in how I came at things. The year in Edmonton, working in the writer-in-residence program, gave me a break from my usual life and a freedom to take a good look around. I started writing some of the poems that made up Kill-site during that time.

Q: What was the impasse you were attempting to reconcile? Was it a shift in tone, or the line, or something else?

A: I wanted to find a way to get more political and philosophical content into a poem, without completely breaking out of the lyric gesture, like I had seen mid Nineties poets in Beijing do. To come to something bulkier, more spreading, but still with a driven music and compelling turns.

Q: Was this your first residency?

A: No. I was w-in-r at the U of Western Ontario in 1989-90 and at the Regina Public Library 1998-9, the year before I went to U of A. I also did a short residency at St. Mary’s University in Halifax.

Q: Looking back on the experience now, how did your University of Alberta experience compare to those other residencies?

A: I remember that year in Edmonton fondly. The department gave me a warm welcome. I had an apartment on Saskatchewan Dr., about a thirty minute walk from the university, near the farmers’ market, a jazz club and a couple of good bookstores, which may no longer be there. The residencies at Western and the RPL were also great, open spaces to think about my work outside my normal routine. I enjoyed talks with Kristjana Gunnars, Bert Almon, Doug Barbour and Greg Hollingshead, long walks by the North Saskatchewan, Oilers games.

Q: How did you engage with students during your residency? Were there any that stood out?

A: I visited numerous classes during my year in Edmonton and met, one-on-one, with many students, poets, prose writers, playwrights. Audrey Whitson stands out among those I consulted with. She was working on a manuscript, which was eventually published as Teaching Places, an important book, and one that I have used in my own teaching. I enjoyed that people from outside the university community, like Audrey, came in to see me. I remember people coming from as far away as Hinton. The city and region had embraced the writer-in-residence program and used it. I also taught a weekend non-credit poetry workshop, and I recall writers like Erin Michie from those sessions.

Q: Given the fact that you aren’t an Alberta writer, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while in Edmonton? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: Well, the landscape was very much my own then. I was living in Saskatoon in those days. I liked to get out to a nice series of trails near Camrose, prairie, ponds and sloughs. That would be a good Sunday outing. Then there were the river trails.

I enjoyed the vital poetry scene in the city, The Stroll of Poets, in which Alice Major was deeply involved, readings at the university. I spent quite a bit of time talking to Tim Bowling and Ted Blodgett about poetry in general.

Edmonton was a great book store city back then, but I don’t know what that scene is like now. Book stores seem to evaporate rather quickly. Long afternoons grazing away at Greenwoods.

Published on April 15, 2016 05:31