Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 35

November 7, 2024

Elizabeth Smart’s Rockcliffe Park, from GEIST

my non-fiction dispatch, "Elizabeth Smart’s Rockcliffe Park," from GEIST magazine (print) is now online!

my non-fiction dispatch, "Elizabeth Smart’s Rockcliffe Park," from GEIST magazine (print) is now online!accompanying image: Jenny Bou, L'éveil de la bienveillance, 2020, handmade collage on cardboard

November 6, 2024

Michael Turner, Playlist: A Profligacy of Your Least-Expected Poems

Everything I think I ambeginning is already in motion and never ends. An infinite middle that “begins”with my periodic need of origins.

This book has itsbeginnings. One of them came in the fall of 2019, when I was on hold waiting tospeak to my cable provider. The song playing was the Beatles’ “Yesterday.”

Another came in 1979,when Debbie, mark, Phil and I began spending after-hours at the Avenue Grill.Each booth had its own jukebox, and we fed ours regularly, colouring our worldwith song.

A third came ten yearsbefore that, in 1969, captured in a long-lost Polaroid of my mother, my sisterand me standing uncomfortably around our piano while my father led us in asing-a-long. On top of the piano was a cloth-bound book called A Treasury ofOur Best-Loved Songs.

Thelatest from Vancouver writer, poet and musician Michael Turner is Playlist: A Profligacy of Your Least-Expected Poems (Vancouver BC: Anvil Press,2024), a collection that follows multiple poetry and prose titles across thirty-plusyears that play with genre, music and narrative layerings, from the infamous

Hard Core Logo

(Vancouver BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1993)—the only Canadian poetry title adapted into a feature-length film—

Kingsway

(Arsenal Pulp Press,1995),

American Whiskey Bar

(Arsenal Pulp Press, 1997),

The Pornographer’s Poem

(Toronto ON: Doubleday, 1999) and the most recent 9x11(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2018) [see my review of such here]. As the backcover of this new collection offers: “Playlist fiddles with a two-partwriting system that begins with the songbooks’ contextual introduction and endswith the songs – or in this instance, poems – to which they refer. Though thesepoems aren’t expressly critical, their formal method of construction qualifiesthem as that subgenre of poetry known as the protest poem.”

Thelatest from Vancouver writer, poet and musician Michael Turner is Playlist: A Profligacy of Your Least-Expected Poems (Vancouver BC: Anvil Press,2024), a collection that follows multiple poetry and prose titles across thirty-plusyears that play with genre, music and narrative layerings, from the infamous

Hard Core Logo

(Vancouver BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1993)—the only Canadian poetry title adapted into a feature-length film—

Kingsway

(Arsenal Pulp Press,1995),

American Whiskey Bar

(Arsenal Pulp Press, 1997),

The Pornographer’s Poem

(Toronto ON: Doubleday, 1999) and the most recent 9x11(Vancouver BC: New Star Books, 2018) [see my review of such here]. As the backcover of this new collection offers: “Playlist fiddles with a two-partwriting system that begins with the songbooks’ contextual introduction and endswith the songs – or in this instance, poems – to which they refer. Though thesepoems aren’t expressly critical, their formal method of construction qualifiesthem as that subgenre of poetry known as the protest poem.” Turner has long been engaged with the the hows of narrative, offering book-lengthtwists, blending working-class first-person commentaries into the lyric, or abook-length poem as long as a particular city street. There are threads herethat run through the length and breadth of Turner’s work, from an interest ingenre, working class flexibilities, autofiction, tour notes, rock ‘n’ rollsongbooks, the lyric sentence and the straighter lyric, and the dual-aspect ofcommentary and poem in Playlist provides an inverse kind ofcall-and-response to the pieces. It is almost a reversal of thepoem-and-response of Leonard Cohen’s Death of a Lady’s Man (McClellandand Stewart, 1978), or even Ken Norris’ COMMENTARIES (above/groundpress, 1999), his chapbook-length prose poem response to his own full-lengthcollection, The Music (Toronto ON: ECW Press, 1995). Turner offers astory, and a song; another story, and another song. Sometimes the story is directlytied to the song that follows, but often it is not, allowing for a series ofsuggested links. There something of the folk-crooner, the work poet, throughthese pages. If Peter Culley (1958-2015) wrote songs, or if Gordon Lightfoot(1938-2023) composed poetry titles, Michael Turner’s Playlist landssomewhere between, perhaps.

I was seven when mymother enrolled me in piano lessons. Mrs. Sather was a nervous widow in herlate-sixties who lived across the park in a magazine clean house with a blindBoston Terrier. It was fun at first – Mrs. Sather’s piano was brighter thanours, its action quicker. But after a year of scales I lost interest. Plus I didn’tlike the way her dog looked at me.

I return to music in myearly teens, first with the mandolin, which I found in a junk shop my fatherliked to visit and taught myself to play. After that, the guitar, especiallythe folkier aspects of bands my friends and I were listening to – the music ofT. Rex, David Bowie and Led Zeppelin.

There were others in mygrade who played musical instruments. Phil was already accomplished on trumpetand guitar, and I marvelled at how he could listen to any song and figure outits chords and solo by ear. Mark also played guitar and sang well enough toturn the words of songs I was familiar with into moods that I was not.

Eventually Phil and Markand others would gather with their amps, drums and keyboards to jam in Phil’s basement.But while they were rocking out on Zappa fragments, flirting with jazz fusion, Isat on the edge of my bed reading bluegrass tabs, or trying to get my handsaround the songs of Melanie Safka, Joni Mitchell, Joan Armatrading and KateBush.

November 5, 2024

torrin a. greathouse, DEED

I Am Beginning to Mistake

the Locust’s Song forSilence

Night is lonely asunplucked

guitar strings. Desire:blue

hum of a phone screenmaking

neon from my skin’s dampspread.

Ugly music of two bodies

rapt in the performanceof lust.

Dance choreographed for athird

party’s pleasure. Thescreen freezes

&, for a moment,pixelates cum

to flake of off-whitesnow.

A mattress can be a kindof desert.

Mine, a drought—

40 days without softness.

My palm makes the sound

of a thirsty mouth. I’mjealous

of crickets, for how theyturn

friction to song.

Fromself-described Washington State-based “transgender cripple-punk poet andessayist” torrin a. greathouse comes the poetry collection

DEED

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2024), following on the heels of herfull-length debut,

Wound from the Mouth of a Wound

(2020). DEEDis a collection of poems on physicality; writing the body—the queer body, thetransgender body, the disabled body—through a lens of resistance, limitation,comfort, discomfort, gender and sex. “The truth of most words / is the bloodythey leave behind.” she writes, to open the poem “While Researching theEtymology of Punk, / I Discover a Creation Myth Stitched into the Liner Notes,”“Every name I’ve given myself— // a kind of injury.” There is an expansiveness thatburns through this collection, moving through elements of burst text anderasure, expressive gestures and a precise, lyric ferocity. “There’s a certaineconomics // to the way I let them fuck me / as if I were a man. My body more /valuable as anything it’s not. I cut // my hair short,” she writes, as part ofthe extended lyric sequence, “I Want to Write an Honest Poem About Desire,” “thenburied—for years—any hope of a future / girl. Call it backpassing. Cost / -benefitanalysis. Safety feature. / I was closeted at every job. After all, /nowhere is safe for girls like me.”

Fromself-described Washington State-based “transgender cripple-punk poet andessayist” torrin a. greathouse comes the poetry collection

DEED

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2024), following on the heels of herfull-length debut,

Wound from the Mouth of a Wound

(2020). DEEDis a collection of poems on physicality; writing the body—the queer body, thetransgender body, the disabled body—through a lens of resistance, limitation,comfort, discomfort, gender and sex. “The truth of most words / is the bloodythey leave behind.” she writes, to open the poem “While Researching theEtymology of Punk, / I Discover a Creation Myth Stitched into the Liner Notes,”“Every name I’ve given myself— // a kind of injury.” There is an expansiveness thatburns through this collection, moving through elements of burst text anderasure, expressive gestures and a precise, lyric ferocity. “There’s a certaineconomics // to the way I let them fuck me / as if I were a man. My body more /valuable as anything it’s not. I cut // my hair short,” she writes, as part ofthe extended lyric sequence, “I Want to Write an Honest Poem About Desire,” “thenburied—for years—any hope of a future / girl. Call it backpassing. Cost / -benefitanalysis. Safety feature. / I was closeted at every job. After all, /nowhere is safe for girls like me.”

November 4, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Clare Goulet

Clare Goulet is aBritish-Québécoise hybrid raised in Nova Scotia. Essays, fiction, reviews, andpoems have been published in journals and books in Canada and abroad including TheFiddlehead, Grain, Room, Dalhousie Review, TAR,Collateral, and Listening to the Heartbeat of Being (MQUP). WithMark Dickinson, she co-edited the anthology Lyric Ecology (Cormorant) onthe work of Jan Zwicky; she's given papers for various scholarly associationson metaphor in science, polyphony, manuscript editing, machine-generated poems,and writing pedagogy. Graphis scripta / writing lichen (Gaspereau) wasreleased May 2024. She lives a few steps from woods and ocean at the edge ofHalifax, where she teaches and directs the Writing Centre at MSVU.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Graphisscripta snuck up between an anthology ofessays on Jan Zwicky, far behind me, and a novel just ahead: between thoseslower, thicker books, this one deked through like a breakaway kid chasing thepuck for the slapshot & through sheer luck landing it. After decadescollecting lichen and slow walks, plus a daily whirl of work and parenting, thebook itself happened fast—had to—and was a sneaky joy to make. I thought that would be the end, didn’trealize that a book can generate its own life once it’s out, and now it’s mechasing after it—readings inunexpected places, lichen walks, scientists getting in touch about poetry,connecting with ecopoets in other countries, new projects. New life.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fictionor non-fiction?

Oh I’ve written all three always – particularly essays aboutmetaphor and science and looking, and small fiction-poetry hybrids, and I canfeel fiction for better or worse tugging at some of these poems – the 2 boys ofHypogymnia (H in the Index of names,power-headed tube lichen) —they popped out of nowhere as main characters andtook over with plastic 80s tampon applicators flapping on their fingers. And Acharius in his garden bent overspecimens, and the pre-war northern British street kids of hammered shieldlichen. Fortunately the whole point ofthe Index was, in a way, to character-ize lichen, unpack the metaphoric names. Way back when I was agonizing over genre asyou do in your 20s, Don McKay penciled a marginal quip: “Poetry has always hadthe hots for prose, and vice versa. As lovers they are much more interestingthan as categories.” It’s still pinned to my wall. The novel ahead, allegedlyfiction, has a prose-poem and non-fiction threads running alongside the story—soperhaps I’ve found the form for me at last!

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

A quick idea—seeing it all in a flash —then slow and painful and dread and masses of overthinking—then(usually, though not with this book) forcing myself to the table, until therelief of revision. But this one was fun—an idea sketched in 2010 on the backof an envelope, then I raised a kid, then found the envelope in the pandemic andwent for it.

I was heartened by Joel Plaskett’s song-a-week project and built weekly deadlinesfor 26 pieces into its Canada Council Research & Creation grant, and made thegame-changing rule for myself that writing had to happen alongside the research, not after. To always be writing, to havethe thing always cooking on the front burner. Thank god for that and for Pavia caféin Herring Cove and its excellent window ledge for scribbling those firstdrafts.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I write lots of one-offs in the moment, most in my drawer, beglad, but I love reading books with atiny focus—could be structural, thematic, conceptual—as they tend to take youeverywhere, and that’s what happened here. After a couple of early lichen poems and essays on metaphor, the idea of a science-art poetic field guidewith an Index of Names came at once, sketched, grounded in walks for localspecies, after years of silent looking. Graphis scripta was always a book.

As for the poems themselves – most begin with looking and a phrase that arrivesunbidden —like a line of music—the notes and the vibe all there – and for me thework is to see if there’s more there, a whole song. Often what comes first is an end that I then writetowards (chasing after the puck again). What to me are the four or five truestpoems in the book arrived entire like that, whole, one draft, it was liketaking dictation. Elf-ear, mushroom, the diva Cladonia, a couple others. Maybe some writers can access thatsphere often or easily or all the time. I’m not there yet!

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’m more used to creating andhosting and organizing and applauding otherwriters at readings; I prefer to be offstage and tend to disappear if a camera’spulled out. But I know that public readings and hearing poems in the moment, together, matters, and so far they’ve each been unexpectedlyfun, particularly with this book. I’m so passionate about lichen that itoverrides shyness, people ask hard, fantastic questions, and it’s the poems outthere, not me. Maybe improper, but I discoveredthat readings (and Brian Bartlett says it’s ok!) are where you can keep revising your poems after publication or try outdifferent versions—I’ve rarely read a poem exactlyas published in the book. Takingdifferent ones out for a spin, or in different combinations for differentvenues—mini-curating—is also fun and changes my own perception of what Ithought I knew.

Readings underscore how place matters: I’m half British, and some poems have turns ofphrase that worked fully only in Ireland and the UK, whereas other poems couldn’t go over at all! (When writer ClarePollard was looking at a couple in revision, I had to explain a ‘cakewalk’—whichby the way sounds super-odd as a custom to non-initiates). Here in Halifaxlocal audiences know the landscape at Herring Cove so I can’t get away withbullshit. Last month, reading pieces on 1810 Irish botanist Ellen Hutchins inher landscape of West Cork, Ireland toher family descendants became suddenly high-stakes – I felt a responsibility ofcare that probably should always be there.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? Whatkinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you eventhink the current questions are?

John Berger famously switched from painting to writing to meet hisown particular 20th-century moment. Here in the 21st, atthis tipping point, I’m not sure that writing meets the current questions. I do seem to trace over the same concerns;failure of language, failure to connect, seeing and mis-seeing things as theyare.

In this case I wanted to reada field guide to lichen that explored the nature of metaphor and couldn’t findone, so I wrote one. At one stage it had a Preface for the concept, deletedlast minute: Metaphor and lichen each about two or more wholes sharing the samespace; lichen isn’t a plant, it’s a relationship,alliance of fungus and at least one photosynthetic partner (alga,cyanobacterium)—as well as other elements we’re only beginning to see. A metaphor, too, associates one thing withanother: something is like but not the same as, not literally, something else,changing our minds in ways that we’re just beginning to understand. The mainmove is that in a metaphor, as in a lichen, each partner remains whole, yettheir conjunction creates something that wasn’t there before. I gave a talk in2006 on this and encountered the analogy twice since, Don McKay in an essay andBrenda Hillman in a recent interview (so hey it must be true!). We each sawdifferent points of congruity, took different paths to the same clearing.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture?Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Oh god, I remember interviewing Karen Connelly back in the ’90s – she wasjust back to Canada from Greece and Thailand and had an articulate impassioned despairing ranton the lack of role in the culture,here in Canada, compared to elsewhere, back in that golden era when somethinglike the state of writing seemed like a serious problem.

I do think—for any art—stitching together disparate fragments intoa piece of wholecloth of some kind—integrating what appears separate, illuminatinga relationship of this to that, connecting—is of immense value ata time when other interests seek to break us apart and see us as pieces morethan wholes, for the purpose of control. I think this kind of art-making of whole paintings, poems, books, jokes,photographs, bread loaves etc is of value not only (or even primarily) for theculture but for the person doing it, the maker. Whole persons can make wholecultures that are resistant and resilient to forces of destruction and control.Putin and his Kremlin cohort know this: there’s a reason missiles are targetingtheatres, libraries, schools, galleries, and cafés where influential writers likeVictoria Amelina were known to congregate. Ukrainians know this and rescuedbooks when the Dnipro dam broke, drying them page by page in the sun. The last thingMaksym Kryvtsov did the day before he waskilled defending Ukraine from invasion—expecting he might be killed—was towrite a poem in the company of his cat. You can read it here.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Essential and wildly enjoyable—puttinga book out means to me the poems have to aim to work for others, as ahospitable gesture, to point and look with someone at something, together. But as a working parent-writer of a youngerchild For this book, it was impossible to access the standard Banff editorial programs that glimmered and beckoned; like manyparents, I couldn’t at the time turn the key and leave for a month, or stopworking. Thankfully Andrew Steeves at Gaspereau gave a lucid sensitive read, plustime, and I invented an editorial development project with a UK writer for ahalf-dozen poems over Zoom, with the Canada Council’s professional developmentgrant and the brilliant Clare Pollard.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)?

Margaret Laurence, in an interview with her I found when I was 16:“You’d be a fool to be an optimist in this world. But you gotta have hope.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetryto critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

Over a life I’m noticing the reverse direction—critical prose topoetry—though I still flip back and forth. I used to love the flip and how each fed the other, but now, moving into complex stories I can feel myself wanting to leaveanalysis behind—having a bit of a break-up with it. It hogged the mic for waytoo long.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do youeven have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

The day begins with the dog needing something, continues with thedog and amazing child needing something, then my wonderful students, returns tothe dog and family, and in between I write. For anything complex, I use longstretches pre-dawn before the dog or the world is awake. (The doghas a great routine though; too bad hedoesn’t write.)

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or returnfor (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I take the problem into the woods and walk a circular trail andlet my brain solve it sideways, without trying to. Or just embrace the stall andsit in granite cliffs by the Atlantic, big ocean, and aim to be empty of words—tolet language, to quote Don, “fray back into air” and just breathe.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Coal. It conjures 1970sStaffordshire where I lived with my grandmother and went to school briefly as achild – coal in the grate to heat the tiny house, coaldust in the bricks, inthe air, in your mouth. Here in Nova Scotia it’s the stink of seaweed at lowtide: it fills you.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, butare there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Yeah this book feels built fromand for a lifetime of books, in a way. Other art forms? Music! Virginia Woolf once said she always conceivedof her books as music before she wrote them. I think certain pieces of musiccan respond to and also shape the rhythms of what you write, or offer complexpolyphonic structures that help you build other complex structures. The novelto come has one thread that’s entirely music, a score composed for and builtinto the story. Without music how can you articulate loss?

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work,or simply your life outside of your work?

Fairy tales and Atwood’s Cat’sEye and the 1986 reprint of Eli Mandel’s Poets of Contemporary Canada 1960-1970—one of those 5-dollarMcClelland & Stewart NCL paperbacks. In college Jan Zwicky’s Lyric Philosophy changed my life in thefull Rilkean sense. Don McKay’s “Baler Twine,” ditto, and not only his essaysand poems (Birding, Or Desire and Apparatus and Vis à Vis and Paradoxides) but the marginalia, jazz collection,postcards, quips and asides, with Don it’s all gold and of a piece. Sue Sinclair, Elizabeth Hay, Anne Simpson, Helen Humphreys. Ilya Kaminsky. In theUK Carol Ann Duffy and Simon Armitage speak to my north-midland English soul,as does Kate Atkinson, whose stories somehow permit serious fun.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write a mystery. It’s inescapable, like cultural genetic code.See: Atkinson, above.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what wouldit be?

It was hands down a cello-playing marine biologist for saltwaterplants until I realized there was such a thing as a lichenologist.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Probably lack of ability to do something else. I read and wrote freakishlyearly so I have no memory of learning to do them, or of not doing them; it’s a hard question to answer as there was never inmemory a ‘before’ books time.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

Film: the slow intense Banel & Adamaby Ramata-Toulaye Sy, with my daughter over the summer, and watching her watchit. Great pleasure books are always for mygreatly pleasurable book-club, currently Emily Wilson’s Iliad and Speedboat, a wild1976 novel by Renata Adler, and I’m behind on both. For poems a recent slip ofa thing that lingered is Slant Lightby Sarah Westcott.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Fiction and poetry at the same time, god help me! Small steps intoa new thing, Loan Words, morelanguage stuff, and a long poem/recording, Subliminal,using 1810 letters of an Irish botanist from the other side of the Atlantic, which forever pulls. Basically whateverI can make at dawn before the rest of the house wakes up.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

November 3, 2024

poems, essays, interviews, chapbooks + upcoming readings: Toronto, Kingston, Calgary etc;

In case you hadn't seen,

I was interviewed recently by Ivy Grimes, for her cleversubstack

.She’s interviewed a whole ton of folk over there, so be sure to check out her archives. And you saw that

Stan Rogal interviewed me for periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

, and

Cara Waterfall interviewed me for her substack as well, yes?

I had

a recent poem up at Amsterdam Review

, and

asection of “the green notebook” up at Annulet

,

with another section up recently at Eunoia Review

.

Did you see all the Canadian books I recommended recently over at 49th Shelf?

I also have a poem in Allium,A Journal of Poetry and Prose

.

My new short story collection, On Beauty, was also featured not long ago over at the Creative Writing at Leicester site.

I should probably be sending more workout, but there’s been less of that lately, between my attentions around theworks-in-progress “the green notebook” and “the genealogy book.” I’m hopingonce at least one of those projects is off my plate I can start focusing againon poems again, as well as that novel-in-progress I keep referencing (some of whichfurthers threads from

On Beauty

, by the way). I also keep forgetting to tell you about chapbooks I've had out recently, including

Retreat journal:

(Montreal: Turret House Press, 2024),

: condition report

(Toronto: Gap Riot Press, 2024) and

the great silence of the poetic line

(Banff: No Press, 2024). Support those presses! Order things!

Although if you were following either my enormously clever substack

or

my ongoing Patreon

, you would have already known about these items (it is a lot to update all of these systems, you know).

In case you hadn't seen,

I was interviewed recently by Ivy Grimes, for her cleversubstack

.She’s interviewed a whole ton of folk over there, so be sure to check out her archives. And you saw that

Stan Rogal interviewed me for periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

, and

Cara Waterfall interviewed me for her substack as well, yes?

I had

a recent poem up at Amsterdam Review

, and

asection of “the green notebook” up at Annulet

,

with another section up recently at Eunoia Review

.

Did you see all the Canadian books I recommended recently over at 49th Shelf?

I also have a poem in Allium,A Journal of Poetry and Prose

.

My new short story collection, On Beauty, was also featured not long ago over at the Creative Writing at Leicester site.

I should probably be sending more workout, but there’s been less of that lately, between my attentions around theworks-in-progress “the green notebook” and “the genealogy book.” I’m hopingonce at least one of those projects is off my plate I can start focusing againon poems again, as well as that novel-in-progress I keep referencing (some of whichfurthers threads from

On Beauty

, by the way). I also keep forgetting to tell you about chapbooks I've had out recently, including

Retreat journal:

(Montreal: Turret House Press, 2024),

: condition report

(Toronto: Gap Riot Press, 2024) and

the great silence of the poetic line

(Banff: No Press, 2024). Support those presses! Order things!

Although if you were following either my enormously clever substack

or

my ongoing Patreon

, you would have already known about these items (it is a lot to update all of these systems, you know).

Oh, and did youhear I’m going to be interviewed by Alan Neal for CBC Radio Ottawa’s All InA Day on Tuesday afternoon? We’re taping around 2pm due to my schedulecollecting our wee monsters from school, so I don’t know yet what time mysegment will air. The show runs from 3-6pm EDT, so you can attempt to catchlive, or check the website after to catch it recorded.

Christine is reading in Toronto on Monday night, as part of the Book*hug Press launch

, and

in Hamilton on Thursday, November 7, as part of a further Book*hug launch

, which has me a few days solo with ouryoung ladies, which is fine. I’m also heading out Toronto way on Friday morning,as Christine and I will meet up for an event I’m part of on Dundas StreetWest on Friday, November 8, reading to help launch a small handful of new letterpress items published by someone editions (including something ofmine) (I’ll also have a handful of copies of my short story collection on hand,if you want a copy). Christine even has a clever graphic she made up with allof her events, some of which I’m part of, even. Oh, and

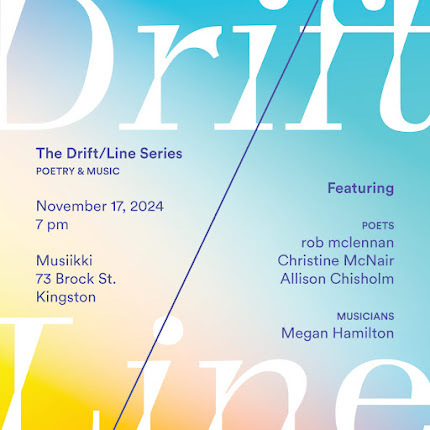

Christine and I read in Kingston on Sunday, November 17 with Alison Chisholm at the Drift/Line Series

, which I’m lookingforward to, lovingly hosted by poet Wanda Praamsma. Do you know her work?

Christine is reading in Toronto on Monday night, as part of the Book*hug Press launch

, and

in Hamilton on Thursday, November 7, as part of a further Book*hug launch

, which has me a few days solo with ouryoung ladies, which is fine. I’m also heading out Toronto way on Friday morning,as Christine and I will meet up for an event I’m part of on Dundas StreetWest on Friday, November 8, reading to help launch a small handful of new letterpress items published by someone editions (including something ofmine) (I’ll also have a handful of copies of my short story collection on hand,if you want a copy). Christine even has a clever graphic she made up with allof her events, some of which I’m part of, even. Oh, and

Christine and I read in Kingston on Sunday, November 17 with Alison Chisholm at the Drift/Line Series

, which I’m lookingforward to, lovingly hosted by poet Wanda Praamsma. Do you know her work?And then there's our reading later this month in Calgary, also, via Single Onion, November 21. There are also plans afoot for Christine and I to read in Vancouver in February, but nothing yet is confirmed.

November 2, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Janet Merran

Janet Merran

received her Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota, and attended classes at the Loft Literary Center. She lives with her family in Minnesota where she enjoys yoga, swimming, and gardening.

Janet Merran

received her Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota, and attended classes at the Loft Literary Center. She lives with her family in Minnesota where she enjoys yoga, swimming, and gardening.As an insider in Top 40 radio in the 1970’s, she experienced its culture and many of its seamier practices first-hand. Top 40 Honeypot is fictional, but it is based on a real era, industry, and culture. This is her first novel.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Top 40 Honeypot is my first novel.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I have published book reviews and concert reviews but Top 40 Honeypot is a story that needed to be told. It is based on my experiences in Top 40 Radio in the 1970’s. I told it for all the women who were afraid to come forward about what happened to them in those days.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I was convinced this story needed to be told and researched the details for quite a long time. I worked with a professional editor and the process was slow, but I learned quite a bit about writing fiction from my editor.

My first draft was too long and was extensively edited.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

This story is a fictitious memoir of two years in the life of a corrupt Top 40 program director. It was written as a book from the beginning, using real time to mark each chapter.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

My book is written for a global audience who read most, if not all of their books, in electronic versions. The novel is action-driven and fast-paced, written with a male audience, aged 24-60 in mind. There are so few books specifically written for men, I think this is a niche that I can fill.

The book could also appeal to those interested in the 1970’s, those interested in the history of radio, and women who want to explore the mind of a predatory male. It’s a “Me Too” book in the voice of the perpetrator. As such, public readings would not fit my audience, and I would probably not enjoy giving public readings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The reader might want to think the subject matter of this book is long in the past. But if one looks at the multiple current accusations against Sean Combs (P. Diddy) you will see that corruption and sexual exploitation in the music industry is far from over.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The role of the writer is to educate and entertain.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I wrote Top 40 Honeypot working closely with a male professional editor. His help was valuable in toughening up the dialogue to the way a man would speak. He also helped with the dialogue of the villainess.

We only clashed on one thing—curse words. He put them in, and I kept taking them out. In the 1970’s average people did not curse in public. In particular disc jockeys didn’t curse in everyday speech, because a curse word slipping out on air could cost their station its license.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Maya Angelou: “When someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time.”

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I like to write in the late afternoon and early evening. My typical day begins with a protein shake and vitamins.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Regular progress appointments with my editor kept me on track writing Top 40 Honeypot. I earned my Master’s Degree as an adult learner, and writing my novel was like turning in assignments.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cigar smoke and Chanel No. 5.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I watch a streaming series or movie almost every night. I especially like dramatizations based on novels.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I have a group of author friends and I always read and review their work. Also, I belong to a woman’s writer’s group in my area. Its members inspire and motivate me.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to put together a genealogy book for my whole extended family, especially since we have some very well-known people on our family tree.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I wrote Top 40 Honeypot after I retired from a career at a major University in Human Resources.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I waited 50 years to write, then publish, Top 40 Honeypot. It took a great deal of courage to get this story out.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The Fourth Turning Is Here: What the Seasons of History Tell Us about How and When This Crisis Will End by Neil Howe, and Oppenheimer .

19 - What are you currently working on?

I currently run social media platforms for a national non-profit organization and I am doing research for two projects.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

November 1, 2024

above/ground press: 2025 subscriptions now available!

The race to the half-century continues! And with more than THIRTEEN HUNDRED TITLES produced to date over thirty-one-plus years, there’s been a ton of above/ground press activity over the past calendar year, including FIFTY TITLES (so far) produced in 2024 alone (including poetry chapbooks by Brook Houglum, Mckenzie Strath, alex benedict, russell carisse, Nate Logan, Sue Landers, John Levy, Vik Shirley, Ian FitzGerald, Peter Jaeger, ryan fitzpatrick, Scott Inniss, Shane Rhodes, Mahaila Smith, Gil McElroy, Carlos A. Pittella, Pearl Pirie, Chris Banks, Helen Hajnoczky, rob mclennan, Kacper Bartczak (trans. by Mark Tardi), Ken Norris, Saba Pakdel, Hope Anderson, Sacha Archer, Peter Myers, Julia Polyck-O'Neill, Kyla Houbolt, Dale Tracy, Phil Hall + Steven Ross Smith, Melissa Eleftherion, Katie Ebbitt, Amanda Deutch, Kyle Flemmer, Pete Smith, russell carisse, Micah Ballard, Angela Caporaso, Cary Fagan, Blunt Research Group, Gary Barwin and Lydia Unsworth, all of which are still in print), as well as issues of the poetry quarterly

Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal]

and an issue of

The Peter F. Yacht Club

.

The race to the half-century continues! And with more than THIRTEEN HUNDRED TITLES produced to date over thirty-one-plus years, there’s been a ton of above/ground press activity over the past calendar year, including FIFTY TITLES (so far) produced in 2024 alone (including poetry chapbooks by Brook Houglum, Mckenzie Strath, alex benedict, russell carisse, Nate Logan, Sue Landers, John Levy, Vik Shirley, Ian FitzGerald, Peter Jaeger, ryan fitzpatrick, Scott Inniss, Shane Rhodes, Mahaila Smith, Gil McElroy, Carlos A. Pittella, Pearl Pirie, Chris Banks, Helen Hajnoczky, rob mclennan, Kacper Bartczak (trans. by Mark Tardi), Ken Norris, Saba Pakdel, Hope Anderson, Sacha Archer, Peter Myers, Julia Polyck-O'Neill, Kyla Houbolt, Dale Tracy, Phil Hall + Steven Ross Smith, Melissa Eleftherion, Katie Ebbitt, Amanda Deutch, Kyle Flemmer, Pete Smith, russell carisse, Micah Ballard, Angela Caporaso, Cary Fagan, Blunt Research Group, Gary Barwin and Lydia Unsworth, all of which are still in print), as well as issues of the poetry quarterly

Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal]

and an issue of

The Peter F. Yacht Club

.The Factory Reading Series is gearing up for some further events, but have you seen the virtual reading series over at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics (with new monthly online content, by the way; the pandemic-era extension of above/ground press). Have you seen the posts, as well, through the (ottawa) small press almanac? lots of information on above/ground press and everyone else in town who makes chapbooks/ephemera etcetera! And the next edition (30th anniversary!) of the ottawa small press fair is November 16th!

One can't forget the prose chapbook series that above/ground started during the pandemic-era , with new titles this year by M.A.C. Farrant, Jacob Wren and Clint Burnham, with a further forthcoming by Susan Gevirtz! And did you see the chapbook anthology Dessa Bayrock guest-edited for the press this year, A Crown of Omnivorous Teeth: poems in honour of Chris Johnson and raccoons in general?

Forthcoming items through the press also include individual chapbooks by Brook Houglum, Nathanael O'Reilly, Orchid Tierney, Andy Weaver, Catriona Strang, Penn Kemp, Jason Heroux and Dag T. Straumsvag, Alice Burdick, Susan Gevirtz, Carter Mckenzie, Maxwell Gontarek, Conal Smiley, Noah Berlatsky, JoAnna Novak, Julia Cohen, Ryan Skrabalak, Terri Witek and David Phillips (a couple of which have already been sent to the printer, by the by), as well as a whole slew of publications that haven't even been decided on yet.

Oh, and groundswell: the best of the third decade of above/ground press, 2013-2023 (Invisible Publishing) appeared last fall, yes? but you probably already knew that.

2025 annual subscriptions (and resubscriptions) are now available: $75 (CAN; American subscribers, $75 US; $100 international) for everything above/ground press makes from the moment you subscribe through to the end of 2025, including chapbooks, broadsheets, The Peter F. Yacht Club and G U E S T [a journal of guest editors] and quarterly poetry journal Touch the Donkey (have you been keeping track of the dozens of interviews posted to the Touch the Donkey site? there are also more than 200 interviews via the Chaudiere Books site with writers currently/formerly Ottawa-based as well, in case such appeals ). Honestly: if I’m making this many titles per calendar year, wouldn’t you call that a good deal? So many things!

Anyone who subscribes on or by December 1st will also receive the last above/ground press package (or two or three) of 2024, including those exciting new titles by all of those folk listed above, plus whatever else the press happens to produce before the turn of the new year.

Why wait? You can either send a cheque (payable to rob mclennan) to 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1H 7M9, or send money via PayPal or e-transfer to rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com (or through the PayPal/donate button up at the top, on the right there. see it?

October 31, 2024

Aditi Machado, Material Witness

now you’re in the middleof the thing

beset by its obvious& lush features

mysterious garment drapedacross a low tree

you sniff its bouquet, itis an odor that goes

beyond description

who left this here &what do you remember

of persons, your handgoing against the surface

tension ferns & falsenasturtiums as you bend

to pick an arrant briar,your whole leg as tho

a bending filament, creepytendrils spurting thru

the accursed growth ofthyself

there are someprehistoric truths here

but where (“NOW”)

Thethird full-length poetry title from poet, translator and essayist Aditi Machado,following

Some Beheadings

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2017) [see my review of such here] and Emporium (2020) [see my review of such here], aswell as the chapbook-essay

The End

(Brooklyn NY: Ugly Duckling Presse,2020) [see my review of such here], is

Material Witness

(NightboatBooks, 2024), a collection set in six sections: “Material Witness,” “What Use,”“Bent Record,” “Concerning Matters Culinary,” “Feeling Transcripts from theOutpost” and “NOW.” Machado’s poems have a lush quality, but with an adornmentthat provides no wasted space. With poems set as extended sequences ofstand-alone sections, her poems have a remarkable ability to expand and contract,furthering a dense, honed language across great distances. “To step into it,”she writes, to open the poem “FEELING TRANSCRIPTS FROM THE OUTPOST,” “timebeing / funnily sequenced or accruing // laterally: a botany tyranny / is moss,is how listening // dithers at the drum and I / follow it out to the fence. //There is a system to regress / in November.”

Thethird full-length poetry title from poet, translator and essayist Aditi Machado,following

Some Beheadings

(New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2017) [see my review of such here] and Emporium (2020) [see my review of such here], aswell as the chapbook-essay

The End

(Brooklyn NY: Ugly Duckling Presse,2020) [see my review of such here], is

Material Witness

(NightboatBooks, 2024), a collection set in six sections: “Material Witness,” “What Use,”“Bent Record,” “Concerning Matters Culinary,” “Feeling Transcripts from theOutpost” and “NOW.” Machado’s poems have a lush quality, but with an adornmentthat provides no wasted space. With poems set as extended sequences ofstand-alone sections, her poems have a remarkable ability to expand and contract,furthering a dense, honed language across great distances. “To step into it,”she writes, to open the poem “FEELING TRANSCRIPTS FROM THE OUTPOST,” “timebeing / funnily sequenced or accruing // laterally: a botany tyranny / is moss,is how listening // dithers at the drum and I / follow it out to the fence. //There is a system to regress / in November.”Shewrites on history, motion, starlight; she writes around and through subjectswith charged lyrics, providing an electrical current even along the most directsentences, as the lengthy sequence “NOW” includes: “inner time rises to meetthe peach / you place your lips against // green rays shoot out // it’s only apain & a pain’s a / direction dislocatedly pointing to / what’s pleasure &when // & where are you, pacific infant / that isn’t heart land [.]” Composedas what appear as direct statements, the quality of lyric emerges through theaccumulation, allowing a nuance of sound pattern and rhythm to flow through theongoingness, one step following further upon another. Listen to the underlay ofrhythm and sound in the opening/title sequence, as she writes:

Then there was no motion.

Then it picked up again,the ‘always already etcetera’ rejects.

Your stamina of compost.

It was like thingsdeferred their freedom to you. No.

It was their kineticenchantments.

Haunted in an old miningtown turning private investment.

Haunted in its distinctodor of data, the labored sound of its pipes.

In the absence ofculture. In the reduction and juice of it. You spat on the

inklings of flowers.

Death to suburbia and youbegan to think again, militantly aroused resident

alien of every which nowhere.

October 30, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ben Robinson

Ben Robinsonis a poet, musician and librarian. His first book, The Book of Benjamin,an essay on naming, birth, and grief was published by Palimpsest Press in 2023.His poetry collection, As Is, was published by ARP Books in September2024. He has only ever lived in Hamilton, Ontario on the traditionalterritories of the Erie, Neutral, Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, andMississaugas. You can find him online at benrobinson.work.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How doesyour most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook helped me meet poets. It took thisthing—poetry—that I was spending an increasing amount of time thinking about,and gave me a way to connect with like-minded folks through reading and mailingand editing and exchanging.

My first book was maybe an extension of this, but also itsopposite. For all of the grief about the decline of the book, I think there’sstill a certain amount of cultural capital attached to the idea of having published a book, such that my first onebrought me back into contact, even briefly, with old neighbours, formerclassmates, friends from out of the country, etc.

As for how my most recent book, AsIs, compares to the earlier work, I think there are common concerns aroundclosely investigating inherited pieces of my identity, like my name, myrelationship to Christianity, or my hometown, and trying to come to both adeeper understanding of the way these forces have shaped me, and also how Imight want to relate to them in the future. That sounds somewhatindividualistic, but I hope these reflections also scale up, that they mightcontribute to broader conversations.

I think As Is differsfrom my past work in that it’s perhaps the most explicitly political. Perhapsthat’s because it’s about place and, while I share other aspects of myidentity, the communal aspect is undeniable when thinking about a city.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fictionor non-fiction?

I’m not sure that I did come to poetry first. I used to write shortfiction but it never felt quite right. I took a lot of my early work in manygenres to the various writers-in-residence at the Hamilton Public Library. OneWiR that I took stories to helped me, in maybe an inadvertent way, to see thatI didn’t really care about the rules of fiction, or at least conventionalfiction. I would bring in a story and she would ask these questions about plotand character development that I had no clue about and ultimately wasn’tinterested in. I’d say that I came to poetry because of its comparativeopenness. I’m not always sure that what I write are 100% poems, but there seemsto be a higher tolerance for divergence in the poetry world.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project?Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do firstdrafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I’m a real notebook writer. The poems often come when I find theconnection between a couple of images or lines in my notes, when it feels likethere’s a charge, like there’s something that merits exploring. Sometimes ittakes a while to find exactly why I’m drawn to a line or how it might be used,but once I find that connection, the poem tends to emerge quickly as I find itdifficult to think about much else in the meantime.

Lately, I’ve been trying to keep my drafts unsettled for as long aspossible. I often find it hard to get back to the generative space with a pieceonce I’ve gone into editing mode, so I’ve been letting my poems stay unfinishedfor as long as possible, giving them time to morph and stretch.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author ofshort pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working ona "book" from the very beginning?

A bit of both, I think. I wrapped up writing As Is at the start of 2023 and I wasn’t sure what would be next. Ididn’t write any new poems for almost a year, and when the new ones did come, Ididn’t immediately see what the connections were, but it’s exciting to watchthe themes slowly emerge and start to coalesce; there's something akin to theway a poem reveals itself in the writing that can also happen with acollection, I think.

The first new poems I wrote were about my experience of fatherhoodand then, seemingly out of nowhere, I wrote a couple of poems about bad adviceI’d received in my life, almost exclusively from men. While the connectionmight seem obvious now, at the time I wasn’t convinced these two sets of poemswere part of the same project. I’m trying to increase my tolerance for thatdivergence, trusting that the variety will ultimately make for a moreinteresting and less predictable collection as opposed to working backward froma theme and intentionally writing poems on particular subjects.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I think it depends when you ask me. On the day of a reading, Imight say that they’re counter to my process because I find the anticipationkind of immobilizing, whereas once I’m about two minutes into a reading orafter, I’d probably say they’re part of the process. It’s great to meet otherpoets and readers of poetry, to share the poems I’ve been tinkering with insolitude, but it takes a lot out of me. Maybe the nerves will go away one day,but they haven’t yet. Now I just know to expect them and keep going.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? Whatkinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you eventhink the current questions are?

I find this kind of question hard to answer. I did an interview with Kevin Heslop for my last book and it felt like a kind of creativetherapy—he had such great language for the connections between my projects thatI’m not all that conscious of. Each project has its particular theoreticalconcerns, but the broader ones are more elusive. I guess I’m interested in thebig questions: How should we live? What to do with life’s many coincidences andcontradictions?

I think I’m more concerned with the effect of my writing. The booksthat I love feel essential, both as pieces of writing, and also to my life ingeneral; they keep me attuned to the many nuances of experience that tend toget flattened out in daily living. I read a blurb once that talked about“obliterating cliche” [Anne Boyer, TheUndying] which I like—to take the old standards (life, death, love, home,family, etc.) and find some small particularity that might make them feelurgent again.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

I’m not sure that I operate in the larger culture, but I’m okaywith small. The writers I respect, even in their limited and local ways, aredoing the difficult work of thinking deeply, of escaping the rut of what hasalready been thought, or written down, or is Googleable and are revealing howmuch more complex life is out beyond the bounds of the feasible, the realisticor the expedient.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Yes, certainly both. I’ve tried to get better at emotionallypreparing myself for editing, to resist defensiveness. My default positiontends to be either wholesale acceptance or rejection of suggestions, but I’vebeen getting better at slowing down and evaluating edits individually.

Lately, I’ve had the opportunity to work with some great editors(as well as poets in their own rights) like Karen Solie and Annick MacAskill.My work is much stronger for their engagements with it, but, despite the factthat they are both unfailingly lovely people, it’s a vulnerable process for me.Ultimately, I try to remind myself that there are plenty of people in my life(thankfully) that I could go to for simple praise, to tell me that the poemsare “good,” and while praise is certainly nice and, to an extent, necessary,constructive and insightful feedback is so much harder to come by and is a realgift that ought to be treated as such.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)?

Put the problem into the poem - Robert Hass. This one works for bothwriting and life, I think.

Sometimes I’ll make lists of my worries about a given piece, aboutwhat might be missing, about how it might be misread. Some of these worriesjust need to be written down and then moved on from, others help reveal whatmight be missing in the project. When I was writing “Between the Lakes” whichis a long poem that threads throughout AsIs, I was concerned that the poem, which is trying to engage with the land,was doing so largely from within the confines of a car which was of courseactively degrading that same land. After reading Gabriel Guddings' Rhode Island Notebook where heobsessively lists his mileage and direction of travel, I realized that I neededto address this tension in the poem and so, in the final version, I includedmoments where the smeared windshield, or the gas station—the materialconditions of the poem’s construction—are visible and I think the piece isstronger for it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry toreviews to music)? What do you see as the appeal?

I don’t think of the transitions in terms of ease or difficulty. Asmuch as I love poetry, there are only so many hours I can spend with it in agiven day, and when I reach that saturation point, it’s not easy or difficultto transition, just necessary. They are all pursuits that I enjoy and theycertainly feed one another, but I move between them in the same way that Imight leave off writing a poem to ride my bike, or make dinner: because I thinkit’s important and valuable to fill a life with many different endeavours.

The reviews or interviews are a bit more related, but I think theystarted as, and continue to be, a natural outflow of my reading practice, oftrying to think deeply about poetry and then wanting to offer some of that timeand effort to others. They are another way to participate in a literarycommunity, to escape the limits of introversion and ask brilliant people abouttheir practice in a structured environment that also hopefully serves to bringmore readers to work that I think is useful or excellent or interesting.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do youeven have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My routine has shifted a lot lately. Right now, with it beingsummer and having both my sons home all the time, my routine is noroutine—writing a bit on the bus to work, in the back room of the library on mylunch hour, at the kitchen counter while the little one naps and the big onewatches his shows, in the rare moments where the boys play quietly together andI try to stay as still as possible, so as not to disrupt them.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or returnfor (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Like many, I turn back to reading. I go back to the books that haveresonated with me or go looking for something new that will show me freshpossibilities. I ride my bike, which seems to open up a less conscious part ofmy brain that is capable of quickly solving problems I’ve been fussing with forhours.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I have a poor sense of smell, to be honest. We have a lilac bush inthe yard and my wife loves lilacs so maybe that? My kids love bananas, or atleast the first two bites of a banana, so perhaps the remaining 80% of thebanana that is then abandoned beneath the couch or somewhere similarly out ofthe way. Flowers and decaying fruit, like a Caravaggio. There are many things Ilike about our house, but its “fragrance” isn’t always top of the list.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, butare there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Well for As Is, the bookcame from historical plaques, local newspapers, neighbourhood watch Facebookgroups, archives, old maps, Google Maps, the land itself, by-laws, lawn signs,murals, government forms, realtor fliers, and road signs.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

The aforementioned Gabriel Gudding’s Rhode Island Notebook, C.D. Wright, Juliana Spahr’s Well Then There Now, Solmaz Sharif’s Look, Ari Banias’s A Symmetry, Layli Long Soldier’s “38,” Doug Williams’s Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg, Catherine Venable Moore’s introduction toMuriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead,Susan Howe, bpNichol’s The MartyrologyBook 5, Greg Curnoe’s Deeds/Abstracts,Emma Healey’s “N12”, and Zane Koss’s HarbourGrids.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Escape monolingualism.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what wouldit be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

My first thoughts were all writer-adjacent: journalist, podcaster,documentarian.

There was a time when I wanted to be a recording engineer. I findcutting audio meditative.

Increasingly, I’m fascinated by photography, but I don’t imaginethe career prospects are much better than poetry.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Probably some mix of the low barrier to entry, a preference towardworking alone, being content to sit in one place for long periods of time, andan inability to move on from the structure of school.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last greatfilm?

I loved Joyelle McSweeney’s DeathStyles. The music in her poems is blaring and raucous. And she went so farinto the underworld for this one, at once viscerally engaging with theunimaginable heartbreak of losing a newborn but also venturing off into all theother realms where poets dwell. It’s both mythic and materialist in the bestway.

As for movies, those seem to be the one art form that I haven’tfigured out how to fit into life as a parent without splitting a 2-hour filmacross four sittings. I have a Google spreadsheet of Movies to Watch, like a 2005 version of Letterboxd, which I havenot made much progress on lately. The odd time when my family goes away withoutme, I watch as many movies as I can to make up for it. Kelly Reichardt’s Showing Up was a highlight of my lastbinge—a moving but unassuming look at how art comes from, and is also thwartedby, daily life. Some great weirdos in it, dysfunctional family, but gentle andnearly plotless like many of my favourites.

20 - What are you currently working on?

As I mentioned above, I’m working on a collectionof poems that seems to be focused on fatherhood. I have two young boys who(often delightfully) take up much of my time and energy, so like Hass says, Iam putting the problem into the poem, trying to engage with an experience thatis often either absent from literature or overly sentimentalized, to documentsome of the amazing thinking that children do.

October 29, 2024

Geoffrey Olsen, Nerves Between Song

the fur is dream andgelatinous

I can’t speak or presentcan’t speak

life within mouth ofleaves

dream mouth

arrayed around the bleakopening

I do not have ownershipover blade and all the

things of a blade on theedge of

climactic or feral

and the edge reproducingthe dream in

a now of disaster songs

after songs and I’m also

the cat and the imbuedindirect

that waits, waiting

unordered, unwindowed (“THEDEER HAVENS”)

Followinga pair of chapbooks produced so far is the full-length debut by Brooklyn poet Geoffrey Olsen, his

Nerves Between Song

(Brooklyn NY: Beautiful Days Press, 2024),a collection set as a suite of five sections of poem-clusters: “THE DEERHAVENS” (which appeared previously as an above/ground press chapbook), “nervesbetween song,” “LUSH INTERFERENCE,” “THE RADIANT MOSS” and “

Followinga pair of chapbooks produced so far is the full-length debut by Brooklyn poet Geoffrey Olsen, his

Nerves Between Song

(Brooklyn NY: Beautiful Days Press, 2024),a collection set as a suite of five sections of poem-clusters: “THE DEERHAVENS” (which appeared previously as an above/ground press chapbook), “nervesbetween song,” “LUSH INTERFERENCE,” “THE RADIANT MOSS” and “

Hislyrics twist, twirl, accumulate and experiment with form. Across fivepoem-sections, lines and fragments overlap, bleed, accumulate; he writes a kindof field notes for witness, attending both landscape and wildlife. “I could bedoing dialogues for our / experience recessed shadow,” he writes, as part of thepoem “THERE TRANSLUCENCE,” set in the fourth section, “felt declension / lightshakes in the liquid [.]” There’s an ongoingness to Olsen’s lyrics, one thatprovides less of a sense of individual poems or poem-fragments, but a larger,full-length structure of ebbs and flows, gesture and nuance. This collection,this book-length poem, is a complex, lovely thing.

for BrandonShimoda

heat. little circular.embrace ash. voice entangles

shadow prison.little figure stretch against land-

scape. that stolen.that invaded. that incarcerated.

wood surface. sweatsalone. built. the noise is piano

dissolves piano.current, what is gray eye? cat length

sinuous wrapself with tile. curling inward. heat clips

sentence. wantof meaningful. the reserve is heat. a

leather patch.it dissolves bit by bit. fading shade.

evaporation. welick each other, the rock for rock salt.

permission forecstasy. impossibly weighs. a continu-

ous turningdown. “what’s the word for this ongoing?”