Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 38

October 8, 2024

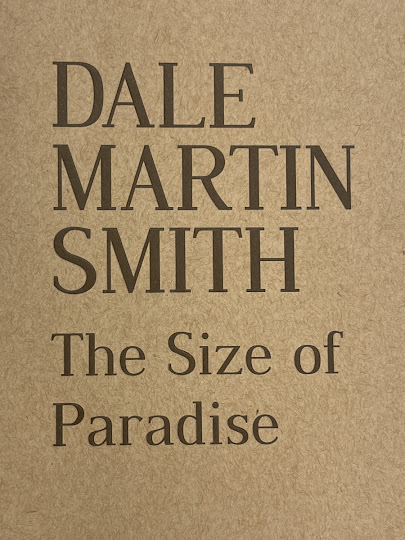

Dale Martin Smith, The Size of Paradise

Dear lord king godlydeath maniac.

I’m just filling spacewith phatic utterance.

Surge for entry, denseroots strangled in clay.

Word by word weave FatTuesday’s brassy balance.

Liminal king of antiquity’ssunk mores.

Now winter braces hymnalswith waste.

No gloves to love with orglow into.

Spin toward disaster—herewe so

take it wildly. Listeningbeyond

where one’s self pretendsplantation. Sensuous

cashmere or Thermore. Flannelsheets and wool

the kids wear threadbare.Dream vocal warden’s

venal agency making roomfor the dead.

A new wind enlivens uncertainty.

I’mintrigued by the latest full-length poetry title by Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Dale Martin Smith,

The Size of Paradise

(Toronto ON: knife|fork|book,2024). The Size of Paradise follows prior full-length collections BlackStone (effing press, 2007), Slow Poetry in America (Cuneiform Press,2014) and

Flying Red Horse

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks 2021) [see my review of such here], as well as numerous chapbooks, including from Riot/ September 2016, an Inside Out Journal (above/ground press, 2019), and atleast two with Kirby’s knife|fork|book: Sons (2017) [see my review of such here] and

Blur

(2022) [see my review of such here]. The Size ofParadise is composed as a kind of book-length sonnet-scape or sonnet suite,one hundred pages of one hundred untitled poems. These are pieces composed throughconstraint, albeit one focused more on a gymnastic language than I’ve seen ofhis work prior, offering an array of poems that each sit self-contained, as akind of repeated response to a particular prompt. “Promised bomb falls at eachstep and the dead / persist in long slumber,” he writes, half-way through thecollection, “cohabitants / of earthly paradise. Circle the many / objects composingyou, insistent / collection folding me in.” There’s a collage-echo to thesentences and phrases assembled here, and I’d be interested to hear how thesepoems began, almost expecting a response involving the daily motion ofcomposing a poem with the only constraint being the sonnet, a consideration ofduration and of writing itself.

I’mintrigued by the latest full-length poetry title by Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Dale Martin Smith,

The Size of Paradise

(Toronto ON: knife|fork|book,2024). The Size of Paradise follows prior full-length collections BlackStone (effing press, 2007), Slow Poetry in America (Cuneiform Press,2014) and

Flying Red Horse

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks 2021) [see my review of such here], as well as numerous chapbooks, including from Riot/ September 2016, an Inside Out Journal (above/ground press, 2019), and atleast two with Kirby’s knife|fork|book: Sons (2017) [see my review of such here] and

Blur

(2022) [see my review of such here]. The Size ofParadise is composed as a kind of book-length sonnet-scape or sonnet suite,one hundred pages of one hundred untitled poems. These are pieces composed throughconstraint, albeit one focused more on a gymnastic language than I’ve seen ofhis work prior, offering an array of poems that each sit self-contained, as akind of repeated response to a particular prompt. “Promised bomb falls at eachstep and the dead / persist in long slumber,” he writes, half-way through thecollection, “cohabitants / of earthly paradise. Circle the many / objects composingyou, insistent / collection folding me in.” There’s a collage-echo to thesentences and phrases assembled here, and I’d be interested to hear how thesepoems began, almost expecting a response involving the daily motion ofcomposing a poem with the only constraint being the sonnet, a consideration ofduration and of writing itself.I’mcurious about the way Smith pushes at the boundaries of the sonnet form,stretching and extending outward in waves, the edges of these poems movingnearly as would lungs. As well, to move through these poems is to move acrossduration in an interesting way, through the very act of writing, and ofreading. “To write is a / residue like beauty,” he writes, early on in thecollection, “a deformity / one adapts.” A few pages further: “I can barelysense duration.”

October 7, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ori Fienberg

Ori Fienberg’s

is the author of the chapbook

Old Habits, New Markets

from elsewhere press, and a micro-chapbook,

InterimAssistant Dean of Having a Rich Inner Life

, part of Ghost City Press’ 2023 summer series. Ori Fienberg’s debut collection of prose poetry, Where Babies ComeFrom, is available for preorder from Cornerstone Press.

Ori Fienberg’s

is the author of the chapbook

Old Habits, New Markets

from elsewhere press, and a micro-chapbook,

InterimAssistant Dean of Having a Rich Inner Life

, part of Ghost City Press’ 2023 summer series. Ori Fienberg’s debut collection of prose poetry, Where Babies ComeFrom, is available for preorder from Cornerstone Press.1 - How did your firstbook or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

Nearly every poem in Where BabiesCome From, like Mr. Peanutbutter’s memoir in Bojack Horseman, “just fellout of me”: beginnings, parallel worlds, childhood (which is a parallel world),alternate realities, anxieties, and strange explanations for how we live in atime that's simultaneously magical and mechanical. I'm still looking forexplanations for how we live, but now rather than finding an unexpected featherto treasure, I get into the dirt and comb through it, like someone who hasstopped dreaming of flying and instead falls asleep to burrowing.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

The first words we understand must bea poem. It’s always been there. But then there were so many stories: AesopFables, Blueberries for Sal, and the tales of Chelm read to me by my parents,and Taran the Wander, read to me by my brother.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Some poets set themselves to write acrown of sonnets about how 14th century Slavic puppeteer Vladimir Richevskilosing his leaf-stuffed kupalo in a fire foreshadowed the triumph of moralityover superstition in itinerant minstrel shows, and each word and each day is astep towards completion. Every poem is a leaf caught falling from a tree: Itend not to be able to grab more than one at once, but I do like making a pile.

4 - Where does a poem orwork of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

A poem has an interesting life cycle. Atleast one of the poems in Where Babies Come From came into being over 20 yearsago. Several began 10 years ago. A poem appears in space because the gravity ofthe words brought it into being. That first poem attracts other words, whichsometimes coalesce into other poems with their own gravitational pull.Gradually a collection begins to form.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

It hardly enters my creative process,but I love the opportunity to introduce audience members to something new andsurprising, and to connect. I hardly know what I'm going to read until a couplehours (or less) before a reading starts, and even then it may change based onthe appearance and mood of the audience. I don't have favorite poems to read,and prefer to mix it up, instead referring to current events, the weather, howI slept the night before, or taking cues from the audience.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

I struggle with the role of the“first-person” and personal and communal identities. In my prose poetrycollection, the first-person rarely appears; in manuscript I’m working on now,many more poems are in the first person, but I still feel constrained by a sortof taboo-of-self: how much do I want to share about my body? How much of myidentity is private, and how much is communal? But outside of my continuousfear of oversharing (which may not be possible in poetry), how can I connectwith other readers who are struggling to live in a rapidly changing world,especially when what we hope for may be out of reach?

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

The role of a writer is to conveytheir experience of the world in a way that enriches the world for someoneelse.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I relish having an editor, but I thinkit’s just, or maybe even more important to read widely and seek out poets whoboth reinforce and challenge my conception of poetry.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t be afraid of writingshit poems. For a while, I was in a poem-a-day writing group, and nearlyeveryone who lasted more than a month wrote a shitty poem occasionally. Writerecklessly. Write without shame. Keep writing.

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (poetry to prose)? What do you see as theappeal?

I lived in the in between for a longtime, completing an MFA in Nonfiction Writing, then writing exclusively prosepoems for many years. I guess I usually prefer a little argument to a long one.I like small, carefully crafted arguments, that are non-Newtonian, but fill outa container. One day my arguments stopped responding the same way; they shearedinstead of compressing. But I’m going back and forth now: I understand my formsof argument better.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I try to make it part of every day.For several years that meant writing in the evening, after the 9-5 work day wasdone, for an hour. I think a routine works best, but sometimes I fall out ofthe routine, and almost as important advice as not being afraid to writeshit-poems, is to not to berate yourself when you can’t lure the right words.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

So much of writing isn’t writing. If Iread a new poem in a literary journal, that's part of my writing routine. If Ichange three words in a poem that hasn't been accepted, but is getting nicenotes from editors, that's part of my writing routine. Sometimes, particularlyin the summer, my writing routine is making a root beer float and then waitingfor the globe of ice cream to fully sublimate.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Home has been many places for me, butone of my earliest scent blends is honeysuckle and chlorine from when we usedto pick blossoms off the fence surrounding the pool at the Jackson, MS HolidayInn.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

In Wales, the Preseli ponies will beyour friend. Mt Monadnock is the most climbed mountain in the world. I waslucky to be taken to Alinea, and saved the bagthe smoked (Alder, maybe?) potato chips came in so I could take whiffs of itlater. I was floored when I discovered Ken Nordine’s Word Jazz.I’ll never stop, a la Tom Waits, asking “what’s he building in there?”.At various points I’ve had Janelle Monae,Curren$y,Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations (including rehearsals),Rob Crow,and Beck on loop. Lindsey Mendickis doing hilarious and disturbing things in narrative ceramics. I invariablyrub my eyes after chopping Thai chilies. There are so many delicious andsurprising forms of inspiration.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

So much of my poetry is predicated on impossiblepossibility that it's maybe unsurprising that outside of poetry I spend most ofmy time reading scifi and fantasy. I typically read 1-2 of these books a week,and often go back to these worlds, sometimes several times. If you haven't readN.K. Jemison's Inheritance Trilogy,now is always a good time. Seanan McGuire’scatalog ranges from doors-to-high-logic-worlds to killer mermaids: it’s endlessand wonderful. You’ll fall in love with Bonedog from T. Kingfisher’s Nettle and Bone.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

My wife (essayist and potter EmilyMaloney) and I have talked about starting aliterary journal that's printed on a brick and pays contributors one brick.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Sometimes, I think I’dlike to mong. There’s a store front around the corner from us that would begreat for a cheese shop.

18 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

You’re saying we get a choice?

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

I love the cozy sci-fi of BeckyChambers’ The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

I'm just starting to submit a newmanuscript, currently titled Every Special Offer is a Special Celebration,which is primarily backyard financial anxiety pastorals. You can read recentlypublished work from the project in the last issues of No Contact Magazineand Superstition Review.

October 6, 2024

Toronto International Festival of Authors’ Small Press Market (part three, : Annick MacAskill + Jay MillAr,

[see part one of my notes here; see part two of my notes here] Here are somefurther notes from my recent participation at the Small Press Market that Kate Siklosi and Gap Riot Press organized and hosted through the Toronto International Festival of Authors. Hooray small press! And I’m hoping youcaught that above/ground press was being represented yesterday in Mississauga, with Christine as table-proxy at the Ampersand Festival? She was also on a panel,discussing her brand-new book! Dang, I wish I could have been there.

[see part one of my notes here; see part two of my notes here] Here are somefurther notes from my recent participation at the Small Press Market that Kate Siklosi and Gap Riot Press organized and hosted through the Toronto International Festival of Authors. Hooray small press! And I’m hoping youcaught that above/ground press was being represented yesterday in Mississauga, with Christine as table-proxy at the Ampersand Festival? She was also on a panel,discussing her brand-new book! Dang, I wish I could have been there.Halifax NS/Toronto ON: I was curious to engagewith the carved lyrics of Halifax poet Annick MacAskill, her small chapbook five from hem (Toronto ON: Gap Riot Press, 2024), set as five short, sharplyrics that each take as their jumping-off points opening quotes from Ovid’s Metamorphosis(8 AD), as translated into English by MacAskill herself. “blazing in mymarrow / laid down the quiver to / greed the god in long fa- / miliar grasseswet / before his carbon-grey,” she writes, to open the poem “Upon losing mygold star & being confronted / by Diana, I, Callisto, tell my story.” This isn’tthe first time MacAskill has slipped into Metamorphosis, having donesame through her Governor General’s Award-winning third collection, ShadowBlight (Gaspereau Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]. The poems hereare extended, nearly breathless, composed as short-lined single stretches ofthought and utterance running down the length of a page. As the poem “Togethertogether together together together / together” begins: “once just another girl/ -friend the goddess cursed me / worse than mute stripped me of / my girlpower gossip / my place in the gaggle / resented my prattle / garrulous oncebut trick / her so now only soak / up the words of others [.]” Whereas that collectionmoved through Metamorphosis as a way to articulate a particular loss, thesepoems are no less intimate through their own explorations, an unfolding of fathers,female relationships and love that teases at something far larger I lookforward to seeing, once the larger shape of the narrative is published as afull-length collection. As the first third or so of the poem “The snake bitesthey sting, yes, but are not, / strictly speaking, the worst part of this” reads:

not my silken farewell

or the blush pinpricks so

faint the world couldhear or

see through shade &fog me

like a token blotted

the end of it & I

slipping asked so fainttoo

his frame now & thatlyre

almost but don’t fadethose

songs mere aftershockstin

Toronto ON: Given how many years I’ve composed birthdaypoems (including my own recent Gap Riot and № Press titles), I’m intrigued byToronto poet Jay MillAr composing his own meditations on making the half-centurymark through Offline: Fifty Thoughts for Fifty Years(Toronto ON: Anstruther Press, 2024), produced as #11 of Anstruther’sManifesto Series. Composed with introductory paragraph and post-script, MillAroffers his thoughts on fifty numbered single-paragraph prose-commentaries, set asone thought immediately following another. There is a curious way that MillArattempts to find ground through a suggestion of disconnect, even flailing,putting one foot down and seeing where the next might lead. Part five, forexample, reads: “When I read older novels, the past has been filed intotouchstones that are recognizable, almost orderly. Unlike the present, which ismultifarious and unwieldy, overflowing. How will this mess be distilled andcommodified by our collective memory fifty or a hundred years from now?” His isa pause, a checking-in, to see where he is at and how one might interact with culturaland temporal shifts, an introspection of and through time and space. “Can onelive autonomously and independently off-grif in a major urban centre?” he asks,as part of the tenth section. MillAr muses on moments and movements, writing onagency, the long shadow of American culture and politics, community, seasons,literature, disposability, institutions, etcetera. There’s an anxiety here asMillAr works through where we’re at, and where we might be headed, slowlyboiling to death (as a frog in a pot on the stove) in and through a sequence ofsituations that might not be okay. He offers no answers, but pushes the veryquestion, and questions. As the essay, the prose-manifesto, opens:

A sensation brought on bythe anxiety of our age rubbing up against the inescapable reality that I amquickly approaching my fiftieth birthday: I have lost the plot. The world, orat least the human world, since this has only ever been a human world to theextent that even the non-human things around us are still human, feels out ofcontrol. And so I find myself undertaking a retreat: I will turn away from theworld into a series of texts meant to represent my thoughts summed up as a seriesof moments. Every time I have the urge to share something on social media, I willadd it to this list instead. My hope is that these texts will become a pathway,pebbles, or crumbs by which I can engage with, and perhaps even to return to,the world.

October 5, 2024

the ottawa small press book fair, fall 2024 (30th anniversary!) edition: November 16, 2024

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:

the ottawa

the ottawasmall press

book fair

fall 2024 : CELEBRATING THIRTY YEARS!

will be held on Saturday, November 16, 2024 at Tom Brown Arena, 141 Bayview Station Road (NOTE NEW LOCATION).

“once upon a time, way way back in October 1994, rob mclennan and James Spyker invented a two-day event called the ottawa small press book fair, and held the first one at the National Archives of Canada...” Spyker moved to Toronto soon after our original event, but the fair continues, thanks in part to the help of generous volunteers, various writers and publishers, and the public for coming out to participate with alla their love and their dollars.

General info:

the ottawa small press book fair

noon to 5pm (opens at 11:00 for exhibitors)

admission free to the public.

$25 for exhibitors, full tables

$12.50 for half-tables

(payable to rob mclennan, c/o 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9; paypal options also available

Note: for the sake of increased demand, we are now offering half tables.

To be included in the exhibitor catalog: please include name of press, address, email, web address, contact person, type of publications, list of publications (with price), if submissions are being considered and any other pertinent info, including upcoming ottawa-area events (if any). Be sure to send by November 1st if you would like to appear in the exhibitor catalogue.

And hopefully we can still do the pre-fair reading as well! details TBA

BE AWARE: given that the spring 2013 was the first to reach capacity (forcing me to say no to at least half a dozen exhibitors), the fair can’t (unfortunately) fit everyone who wishes to participate. The fair is roughly first-come, first-served, although preference will be given to small publishers over self-published authors (being a “small press fair,” after all).

The fair usually contains exhibitors with poetry books, novels, cookbooks, posters, t-shirts, graphic novels, comic books, magazines, scraps of paper, gum-ball machines with poems, 2x4s with text, etc, including regular appearances by publishers including above/ground press, Bywords.ca , Room 302 Books, Textualis Press, Arc Poetry Magazine , Canthius , The Ottawa Arts Review , The Grunge Papers, Apt. 9, Desert Pets Press, In/Words magazine & press, knife | fork | book, Ottawa Press Gang, Proper Tales Press, 40-Watt Spotlight, Puddles of Sky Press, Invisible Publishing, shreeking violet press, Touch the Donkey , Phafours Press, etc etc etc.

The ottawa small press fair is held twice a year (apart from these pandemic silences), and was founded in 1994 by rob mclennan and James Spyker. Organized/hosted since by rob mclennan.

Come on by and see some of the best of the small press from Ottawa and beyond!

Free things can be mailed for fair distribution to the same address. Unfortunately, we are unable to sell things for publishers who aren’t able to make the event.

Also: please let me know if you are able/willing to poster, move tables or distribute fliers for the event. The more people we all tell, the better the fair!

Contact: rob mclennan at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com for questions, or to sign up for a table.

October 4, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tonya Lailey

Tonya Lailey (she/her) writes poetry and essays. Her first full-lengthcollection, Farm : Lot 23, wasreleased this year by Gaspereau Press. Her poem, “The Bottle Depot,” wasshortlisted for Arc Poetry 2024 "Poem of the Year". Her poems “BatLove” and “Love on the Rocks” won first and second prize in FreeFallMagazine’s Annual Poetry Contest 2024. She holds an MFA in creative writingfrom UBC.

1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

My first book has notchanged my life materially – ha! It has given some confidence, and somesmall sense of place in the big open field we call writing. I now know it’spossible to have a manuscript accepted and published. I also know that the publishingexperience can be good. Andrew Steeves, at Gaspereau Press, was lovely to workwith – clear, kind and respectful in his approach. The book always felt like mybook in his hands.

My second manuscript (mymost recent and not yet published) deals with more charged material, namely,addiction and codependency. I don’t know how different the writing is, exactly.I play with form as I do in the first book. A single thread of colour – yellow– runs through this second collection. It felt very different to write thesepoems since I didn’t write them to belong to a book. The poems took shape over10 years, in various workshops and with writing groups, friends.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

At King’s College inHalifax, where I did my undergrad degree, I took a French Feminism course withProfessor Elizabeth Edwards. She was the first person who told me that mywriting was poetic, that I had a sense for metaphor. Whether or not that wastrue, I believed her. I think that metaphor happened to me from readingKristeva and De Beauvoir and being swept up by their prose. I wasn’t much of areader or writer as a teenager. I mean, I won the English award when Igraduated high school, but I didn’t write much beyond school assignments. I spentthe bulk of my time outside of school training as a competitive swimmer, thenalso a runner. Growing up on a farm and doing sports had me living an intensebody life. I think that’s a solid prelude to writing poetry, being deep in thebodies of things, deep in one’s own body— its pains and pleasures. And I’vealso always been a day dreamer, space-cadet as we called it when I was a kid. Ithink poetry is kinder to dreamers than fiction might be. I’ve always felt moreat home catching poems than telling stories.

3 - How long does ittake to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I always have many writingprojects on the go. I think that’s not unusual for writers. Starting projectscomes easily. Developing these ideas and getting them to a point I feel goodabout is not such a snap. It’s rare thata draft appears looking close to its final shape. I take it as a good sign whenit does. I live for the poems that “flow from the hand unbidden”, to quoteDerek Mahon. More often I write by hand frantically to capture what feels mostalive on paper and then I spend hours working with the juicy material, tryingto coax it into something without killing it. It’s not all that different fromwinemaking.

And often, yes, I start with research and many, many pages of notes until Ifeel at home enough in the content to play with it and have a say.

4 - Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

I do both. I write thepoems that arise out of daily living. I write them to write them. I believe inthose poems. They keep me going, the way perennials keep me wanting to garden,and seeds that germinate keep me wanting to plant seeds.

That said, I also likepiloting projects. There’s a thrill in imagining a book then working to pull itoff, especially if I’m open to “it” becoming not what I thought it would be.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

Hmmm. I’m not sure yet.I haven’t done enough of them. I’ll say I learn a lot about my writing byreading it out loud to people. I hear more clearly where the writing trips overitself. I hear where I may need other words I haven’t found yet.

I have both enjoyedreadings and not enjoyed readings. The biggest barrier to enjoyment is typicallymyself, my insecurities. If I prepare myself in a loving way and read from thatplace, lo and behold, I find I can love the reading. I try to remember topractice what Richard Wagamese writes in Embers:

When my energy is low,meaning I don’t feel at my best in terms of creativity, inspiration, attunementor rest, I let Creator have my flow and ask only to be a channel. My deepestaudience connection has always happened when I do this. So, on my way to apodium nowadays, I say to myself, ‘Okay, Creator, you and me, one more time.’When I surrender the delivery, along with the outcome, the anxiety and theexpectation, everything becomes miraculous. It’s a recipe for life, really.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

Oh, yeah. I’m alwaysasking about love and relationships, how to love, how to have betterrelationships, what that looks like, how it’s done, what the actions are,whether the desire for sustainable, deep, caring love (not caretaking love) isa pipedream or an attainable, generative foundation for living. I’m betting the latter. And by relationships,I mean all of them—to the self, to each other, to difference, to all the otherlife on the planet, to technology, to work, to eating, to aging, to death.

So, that’s also to saythat I’m concerned about the social and economic systems within which we conductour collective selves and that shape our imaginations for what is and whatcould be. I don’t like how we tend to define our choices, limit them. It’sstrange because in so many ways we scoff at limitations, particularly when itcomes to the exploitation of natural resources. At the same time, ourimagination for public wealth and well-being is gravely constrained. So, yeah,I’m concerned about concentrations of wealth and power and how limiting anddeadly they are / we know them to be.

I am also concernedabout the degree to which women continue to be held in contempt in our culture.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

I’m not one for“should”. And, I don’t know about writers having a defined role in largercultures. Something about attempting to define that makes me uncomfortable. Idon’t think writers are a special class of people. Writers are people who writeand share/distribute their writing in public places. I want to live in a worldwhere people do that. And I want to live in a world where people are interestedin reading what other people are writing about, especially if those otherpeople live very different lives from their own. I want to live in a world thatthrums with imagination. Writing can be one way to cultivate imagination.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Again, my experience islimited. To date I have had only positive experiences with outside editors, butI know writer-editor relationships can be fraught with difficulties.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t write to be loved.

10 - How easy has itbeen for you to move between genres (poetry to essays to children's fiction)?What do you see as the appeal?

I find it a challengeand a relief to move between genres. My move is most often from poetry tocreative non-fiction. I find the scale of CNF intimidating – it tends to happenover so many pages whereas I can contain a poem on one page. Since I writemostly poetry, when I go to write a poem I can drop into a certain state. Idon’t have that as reliably with CNF. I definitely don’t have that yet withfiction.

11 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I tend to resistroutine, but I like commitment. So, I commit to a certain number of hours eachday. That number changes, almost daily. Alternately, I commit to finishingsomething, which doesn’t mean I won’t work on it again but rather that I’llsubmit it for publication and see what happens.

The one constant is thatevery day begins with an hour of spiritual-type readings and a brief free writeor “noticing poems” as Patrick Lane called them.

Early morning is my bestwriting time. I tend to wake up with a thin skin, alert and sensitive. This canwork well for writing.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I go for a walk. Iclean. I make food.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Parathion. Woodsmoke.Rotting peaches. Fermenting grapes. Diesel. Cedar. Yew.

Willow. Kerosene. Brownbread and baked beans.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes : Plants. Paintings.Photographs. Music. Science – botany usually. Sculpture.

And the fabric arts arenot to be overlooked! And the prompt – a poetry prompt is an art form I tellyou.

15 - What other writersor writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of yourwork?

I tend to freeze whensomeone asks me this question, so I’ll just start writing the names of thewriters that feel most present with me these days. Emily Dickinson / Ross Gay /Claire Keegan / Sarah Moss / Ocean Vuong / Alice Oswald / Seamus Heaney / JaneHirshfield / Marie Howe / Ada Limón / Richard Wagamese / Richard Powers /Susan Musgrave / Sue Goyette / Joan Didion / Rainer Maria Rilke / Anne Lamott /Bronwen Tate / Lorna Crozier / Bob Hicok / Gregory Orr / Aimee Nezhukumatathil/ Karen Solie / Naomi Shihab Nye. And so many Canadian poets not already namedwhom I work with or have shared work with like, Juleta Severson-Baker, Mary Vlooswyk, Erin E. McGregor, Kimberley Orton, Bren Simmers, Barbara Pelman,Barbara Kenney, Micheline Maylor, Lisa Richter, Richard Osler, AndreaScott…this list is much longer but this is a start.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

The Biles II.

Write a novel that getspublished and then read by at least a handful of people.

17 - If you could pickany other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

In no order: mastergardener for hire, vegetable/flower farmer with a market stall (you know, evenjust a folding table would be great), winemaker with a market stall (but withno sampling, I’ve been that woman and it wasn’t fun).

18 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

The flexible schedule: Ihad kids. I’m not great with my hands. I was encouraged to do it on a fewoccasions that remain vivid for me – felt like a lightning strike. Writing cantake place in bed, in a car, on a log, with a frog. Farming is bloody hard work.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

Book? Books:

I’ve read both booksthree times. I’m not even sure why I find these books so affecting but I do.The writing comes close to the bone while feeling deeply mysterious. I find ituncanny.

Film? Films:

The Cathedral

Good luck to you, Leo Grande

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

An essay about traffic,driving, the end-days of cars, with the working title: “Palliative Car”.

A couple of poetry bookreviews.

A commonplace book onthe Black Ash Tree that I hope is the foundation for a hybrid form book withthe working title: “In Light of the Black Ash”

A drawing practice – Iwant to draw regularly.

Italian; learning it.

I need to write apantoum that incorporates things near and things far; it’s for a writing group.(So far, it’s gotten no further than the back of my mind.)

Everyday poems that comeup, as they do.

Revisions to shortstories I wrote two years ago.

October 3, 2024

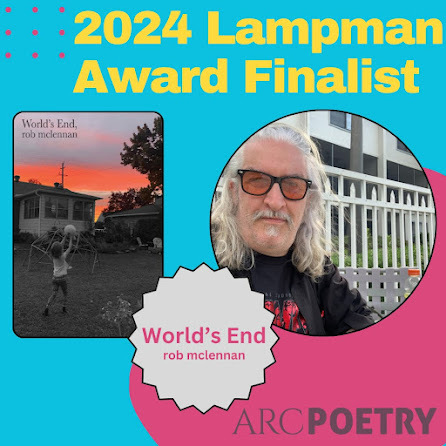

the first review of On Beauty, the Archibald Lampman Shortlist + upcoming shortlist reading,

In case you hadn't heard, my latest poetry title,

World's End,

(ARP Books, 2023), was recently shortlisted for the Archibald Lampman Award, alongside D.S. Stymeist's Cluster Flux (Frontenac House, 2023) and Sandra Ridley's Vixen (Book*hug Press) [see my review of such here]. Naturally, I've lost track of how many times (a handful, certainly) I've been up for the Lampman (always a bridesmaid, never the bride, as Bugs Bunny once complained as well), although the last time I was, ten years ago, it was also along Sandra Ridley (for those at home, keeping score). If you are so inclined, also, be aware that the three of us will be participating in a Lampman Award Shortlist reading this coming Monday at 7pm at Ottawa's SPAO: Photographic Arts Centre, 77 Pamilla Street (in Little Italy). In other news, Canadian writer J. Jill Robinson was good enough to provide a deeply generous first review of

On Beauty: stories

(University of Alberta Press) over at Goodreads! Thanks so much! Here's the link to where she posted the review, or you can read such, below:

In case you hadn't heard, my latest poetry title,

World's End,

(ARP Books, 2023), was recently shortlisted for the Archibald Lampman Award, alongside D.S. Stymeist's Cluster Flux (Frontenac House, 2023) and Sandra Ridley's Vixen (Book*hug Press) [see my review of such here]. Naturally, I've lost track of how many times (a handful, certainly) I've been up for the Lampman (always a bridesmaid, never the bride, as Bugs Bunny once complained as well), although the last time I was, ten years ago, it was also along Sandra Ridley (for those at home, keeping score). If you are so inclined, also, be aware that the three of us will be participating in a Lampman Award Shortlist reading this coming Monday at 7pm at Ottawa's SPAO: Photographic Arts Centre, 77 Pamilla Street (in Little Italy). In other news, Canadian writer J. Jill Robinson was good enough to provide a deeply generous first review of

On Beauty: stories

(University of Alberta Press) over at Goodreads! Thanks so much! Here's the link to where she posted the review, or you can read such, below:I’ve been thoroughly enjoying reading and being challenged by rob mclennan’s fine new book of stories, On Beauty. It’s called ‘stories,’ but the author’s approach to narrative is largely unconventional, untraditional, and distinctive.

In mclennan’s work there is a fine balance between how each piece happens and what happens, which is a particular delight for readers who are writers: opportunities to learn craft from a master. Poetry and prose combine, and fuse. mclennan has the facility with language of a poet, uses compression like a poet, yet he also indulges a fondness for story. He uses brush strokes, wispy suggestions, evocative details, and graceful, often charming phrasing to convey meaning drawn from the domestic to the sublime.

At times mclennan speaks directly to writerly choices in craft: for example, “Who is the intended reader of the contemporary novel? Some books are composed to be intimate. Is that better, or worse? Perhaps an improvement to be spoken to directly, as opposed to listening in to a conversation between others.” Thus the frequent use of the close third person, and first person, drawing his readers near to his head, and his heart.

Each of the often brief stories, which are interspersed with fourteen “On Beauty” sections, is introduced by a quote that both informs each piece, and also illustrates how well-read mclennan is, how varied his influence are, seen through a wide range of writers including writers like Brossard, Auster, Kundera, Wah, Stein, Miranda July, Gunnars, and many others. A diverse bunch of language lovers.

Examples are surely the best way to convey the fineness of mclennan’s work. Here are a few of my favourites.

Before his son is born, the persona writes, with humour and delight:

I was beginning to see them more clearly, fleshy outline of baby-foot in my dear wife’s belly. There was something inside.

And then, on witnessing the birth of that son, the persona observes:

Stunned as our newborn pulled himself to the breast. Baby skin-to-skin as I quietly wept, and our new trio drifted from anxiety to relief.

Note how much he can convey in so few words, a quick character sketch of a wife as an domestic whirlwind: "Their mother a flurry of cupboards and movement"

And then there’s this, which follows a quote from Paul Auster: "What frightens us most isn’t death, but its result: absence"

Or, in “Translator’s note,” “I am shaped by these words, as I understand them.”

And here’s one of my favourites, in which a social media excerpt is incorporated:

On National Boyfriend Day, @adultmomband posted: that ex u still romanticize is just a concocted projection based off of everything they were never able to give you.”

The piece goes on to note: All of this is projection. All of this is created.

Throughout On Beauty mclennan provides the reader with the “delightful instruction” Aristotle speaks of. I would add that On Beauty is also of beauty, in beauty, from beauty, as well as being simply beautifully written, beautifully expressed. Lovers of language and of narrative will delight in this volume.

Congratulations, rob mclennan, on this fine book of intellectually and emotionally engaging work, work that skilfully uses the abstract and the concrete to entertain, touch, and move the reader with mclennan’s open mind and open heart.

October 2, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Leah Souffrant

Leah Souffrant is a writer and artist committed to interdisciplinary practice. Sheis the author of

Entanglements: Threads woven from history, memory, and the body

(Unbound Edition Press 2023) and

Plain Burned Things: A Poetics of the Unsayable

(Collection Clinamen, PULG Liège 2017). The range ofSouffrant’s work includes poetry, visual art, translation, and critical work inliterature, feminist theory, and performance. She teaches writing at New YorkUniversity.

Leah Souffrant is a writer and artist committed to interdisciplinary practice. Sheis the author of

Entanglements: Threads woven from history, memory, and the body

(Unbound Edition Press 2023) and

Plain Burned Things: A Poetics of the Unsayable

(Collection Clinamen, PULG Liège 2017). The range ofSouffrant’s work includes poetry, visual art, translation, and critical work inliterature, feminist theory, and performance. She teaches writing at New YorkUniversity.1 - Howdid your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

Every time a book is published, it isimportant. That affirmation, showing that your work reached a reader, canenergize the works that come next, and that’s been true with my books.

2 - Howdid you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry had been the most freeingwriting, where sound and idea and image intermingle in unexpected ways. Givenhow poetry is often taught with emphasis on form and received “meaning,” thisliberating relationship to poetry isn’t always the case for young writers. Inrecent years, the categories themselves – poetry, fiction, non-fiction, memoir,and so on – have felt restrictive. Now, writing is most free when I’m not boundby those categories, or where the boundaries blur. A poem composed ofsentences. An essay that slips into poetic lines. Non-fiction infused byimaginative sequences. This flexibility revives the sense of freedom I recallwhen poetry first seduced me as a writer.

3 - Howlong does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Writing is fast and slow at the sametime. Some of my most satisfying writing comes in bursts, quickly written, butwhat the reader eventually encounters is the result of a slow process. Instarting a poem, I might see or hear something, and it begins, and throughwriting I figure something out. Then I re-write, often for sound and oftencutting the first couple of lines or moving them to a later moment in the poem.

Writing longer-form prose is both fastand slow, too, but on a more sprawling scale. Writing prose, what I’mencountering is often research. So that takes time, collecting those encounterswith reading and experience and research. I write as I go then rearrangethings. I love both the urgency of getting ideas down, reacting to thoughts –my own and others’ – and I love the slow meditation on the shape of the line orthe shape of the paragraph.

One of my favorite things to do withmy writing is to move things around and see how those changes impact thewriting, the experience of reading. It’s extraordinary and fascinating, how theorder of the encounter impacts our mind and feelings. Or, I might say, How theorder of the encounter impacts our mind and feelings is extraordinary andfascinating. And to do that, I have to slow down.

4 - Wheredoes a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

I begin noticing something – a word ina book, a sensation in the body, and experience in life. Often thoseobservations build into a pattern of observations, which eventual become abook. That can feel like a “project” once I start to fix on tracking thosepatterns of encounter. I want a book to have a sense of wholeness, whichbecomes more coherent when a project emerges. But it’s often hard to know whatwill inform that coherence until later in the writing process. Nevertheless, weall have preoccupations, and that informs what we write.

And as a reader I love project booksand focused series. Today I’m thinking about The Glass Essay by Anne Carson or the Lucy poems in Break The Glass by Jean Valentine come to mind. I love TheRupture Tense by Jenny Xie.

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

Pacing, repetition, coherence,variation, silence and noise, ambient sounds we can’t control or anticipate… Theyall fascinate me. Public readings push me to be thoughtful about what and how Ishare with a live audience. Some books – likely most of my book Entanglements– are more impactful when encountered privately by a reader. I’m interested inthe different ways we come to knowledge, and a live performance is a differentencounter than a private reading.

6 - Doyou have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questionsare you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

Memory and embodiment – how what we doand remember (and forget) relates to how we understand and make sense of theworld – are endlessly interesting to me, and lately I’ve been especiallyinterested in the ways these theoretical concerns emerge in everyday or mundaneexperience. I’m deeply interested in questions about love, in private and incommunity. My writing returns again and again to women’s experience, and moregenerally those experiences that are underexamined or difficult to name.

Abiding concerns in my writing and artinclude what is difficult or impossible to convey, yet are essential to humanexperience, understanding, knowledge and ignorance. My first published book, PlainBurned Things: A Poetics of the Unsayable, works to name what is often mostpowerful to me in books: the ways what is blank or silent in a work of art isoften holding something important, often traumatic, and the difficulty orimpossibility of conveying that importance is very exciting to me as a readerand writer and artist. My recent book Entanglements: threads woven throughhistory, memory, and the body, enacts the principle that what weexperience, what we read, what we learn, what we inherit, all impact knowledgeand ideas.

7 – Whatdo you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Reading can make us slow down, payattention. We pay attention differently and to different things (ideas, worlds,experiences) when we read. This feels like an urgent practice to cultivate now,given the ways the “larger culture” forces an attenuation of attention in somany ways. Of course, not all writing challenges that force, but I valuewriting that invites a slowing, that seduces us to slow down.

8 - Doyou find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential(or both)?

I have a few readers I turn to duringthe editing process. I sincerely value the insights of those trusted readers. Irely on different people for different projects. Finding these people isessential work of writing, being in community -- and the challenge of findingreaders and editors you trust is something I appreciate more as time goes by.

9 - Whatis the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

I’m a writer because I write, and I’ma poet when I write poems, an artist when I paint. I really believe in the callto do the work. Create, write, persist. Put in the time. It’s a sort of faith,but it’s also practice. You just have to do to become, and if you don’t dothen you aren’t that – you’re doing something else – but if you are doing it,you can (and should) claim that practice.

10 - Howeasy has it been for you to move between genres (poems to art to criticism)?What do you see as the appeal?

Easy – essential, even.

11 - Whatkind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How doesa typical day (for you) begin?

Wake up early. Write anything. Thenpick up where you left off – a line, a reading, a sketch, whatever the work is.And at the end of your (creative) day, leave something for tomorrow to discoverand continue. Leave these gifts for yourself to keep you working next time youturn to the page or the studio or the file.

Depending on the time of year and myother commitments (teaching, for example), my schedule fluctuates, but havingmorning time to write makes a big difference to me. There have been times in mylife when that meant setting an alarm for 5am to make it possible. If I getsomething down first thing in the morning, the rest of the day is buoyed bythat effort.

12 - Whenyour writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

Walking and reading – not at the sametime.

13 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

Less is more when it comes tofragrance; I’m keenly sensitive to smells. When I’m not distracted by anyscent, then I feel at home.

14 -David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any otherforms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Entanglements, my 2023 book, is in part a meditation on how everything impacts us. Isteadfastly believe all these influences and experiences are entangled in whatwe think and know and create.

15 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

I often return to Simone Weil. AndRilke. They remind me of the profound power of thinking with others, of poetryand ideas. And Anne Carson’s writing has been very important to me, not onlyindividual books, but the ways Carson experiments and reaches across genres,disciplines, and conventions. Yoko Ono’s art and writing has had a deep impacton me, too, for similar reasons.

16 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’d love to show my art more widely,to make the connection between my writing and visual art more available, andperhaps to a different audience.

17 - Ifyou could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

As a child, I thought about becomingan architect, because the architect puzzles out the use of space, but I’venever been very interested in precise measurements, so I wouldn’t trust myselfwith architecture. Then, thinking about similar puzzles of space and how anenvironment makes us feel, makes me think of interior design. Shaping theexperience of being in a space interests me, and interior design should be lessdangerous that an imprecise building.

18 - Whatmade you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing is a way of thinking – I needthis, and I’ve felt connected to that process for as long as I can remember.And it’s fun, too (sometimes!). Writing is fundamental for me. Even when it’shard. And beyond my own private needs for working out ideas and experiences, Ivalue sharing ideas with others -- in person, in conversation, in theclassroom, as a reader. As a writer, I enter this broader conversation byoffering ideas and images, even with unknown readers. Writing – and putting itout into the world -- is an act of optimism, compassion, and curiosity, all ofwhich are vital.

19 - Whatwas the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Great books are hard for me to narrowdown, but what stands out to me right now are Lewis Hyde’s A Primer forForgetting and Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the Worldand Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living. (Ask me tomorrow, and I’ll likelyhave a new list!) The last great film I’ve seen – easy: Poor Things.

20 - Whatare you currently working on?

As usual, I’ve got a few irons on thefire. I spend many days in my studio painting and drawing. This summer Ifinished the first draft of a novel, which is a new genre for me, and I’mrevising a collection of poetry, working to bring together older and newerpoems. And I’ve continued a performance research project as part of the LeAB Iteration Lab with poet and theater artist Abby Paige. All this contributes todeveloping ideas about creative practice, memory, and experience, which areabiding interests.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

September 30, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Megan Pinto

Megan Pinto

is the author of

Saints of Little Faith

(Four Way Books, 2024). The winner of the 2023 Halley Prize from the MassachusettsQuarterly Review, Megan’s poems can be found in the Los Angeles Reviewof Books, Ploughshares, Lit Hub, and elsewhere. She has received scholarships and fellowshipsfrom the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference, the Martha's Vineyard Institute ofCreative Writing, the Port Townsend Writers' Conference, Storyknife, and an AmyAward from Poets & Writers. Megan lives in Brooklyn and holds an MFAin Poetry from Warren Wilson.

Megan Pinto

is the author of

Saints of Little Faith

(Four Way Books, 2024). The winner of the 2023 Halley Prize from the MassachusettsQuarterly Review, Megan’s poems can be found in the Los Angeles Reviewof Books, Ploughshares, Lit Hub, and elsewhere. She has received scholarships and fellowshipsfrom the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference, the Martha's Vineyard Institute ofCreative Writing, the Port Townsend Writers' Conference, Storyknife, and an AmyAward from Poets & Writers. Megan lives in Brooklyn and holds an MFAin Poetry from Warren Wilson.1 - How did yourfirst book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to yourprevious? How does it feel different?

Saints of Little Faith is my firstbook! I have always dreamed of having a book out in the world. Achieving adream is life changing in and of itself. Now I know it is possible.

2 - How did you cometo poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I read Anne Carson’s The Beauty of theHusband, in my first college English class and was forever changed.Before that point, I knew I wanted to be a writer. But after reading Carson, Iknew I wanted to devote myself to studying poetry, and learning how to writebeautifully.

3 - How long does ittake to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

In the beginning, I am following littlecuriosities. I tend to let the poems accrue, and not worry too much about thelarger architecture . About every 6 months or so, I like to print outeverything I have been working on and tape it up on the wall. I leave it likethat for another month, and revisit it frequently. I start to see how the poemsare talking to each other, and my deeper interests and themes begin to revealthemselves to me. Then I go back to generating new work.

4 - Where does apoem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

Poems usually begin for me with a musicalphrase or an image. A rhythm that stays in my mind, and propels me into thedraft. I would say I write musically, imagistic ally, and instinctually atfirst, and only later after many drafts I start to ask myself “what is thispoem trying to say?”. I am mostly going poem by poem. Only toward the very end,once the manuscript has started to become clear to me, am I writing morespecifically into the holes in the manuscript.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I see public readings as a parallel practice. Iread my poems aloud in private while revising, but public readings aredifferent. They sometimes reveal to me what I want to revise, if I falter overa line or verbally edit a phrase mid-reading, but mostly they teach me about myown vulnerabilities. What I’ve processed enough to share with others, and whatstill feels tender to me.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

In terms of my own work, I’m less interested intheory and more in beauty. I hope I make something that allows other people tofeel deeply.

7 – What do you seethe current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one?What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To listen, not just hear. To look, not justsee.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential! I’m not too precious with my workand I always appreciate the extra eye of a trusted editor. Sometimes thingsthat make sense to me inside my head do not totally translate. Four Way hasbeen so wonderful with edits. Hannah Matheson (my brilliant editor) is sothoughtful and kind. Editors make me feel confident about releasing my workinto the world.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

After college I read Twyla Tharp’s TheCreative Habit, and she talks about leaning against a problem or idea,instead of forcing a solution. I love that verb in this context. To leanagainst the idea. Keeping contact, but not forcing. Sharing someweight.

10 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I tend to have writing heavy months and readingheavy months, and these alternate due to the demands of my day job (I work inadvertising) and personal life. That being said, I can write whenever,wherever. If it’s a writing month, some days will have 5 minutes of writing,some will have hour long stretches. It depends on what I’m working on thatweek. If I’m generating heavily or revising. A typical day begins with somemovement, coffee, and breakfast. Hopefully I have a little time to readsomething that is inspires me.

11 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

This is such an important part of the writingpractice. For me, I’ve learned that whenever my writing is stalled, it meansI’m not reading something that speaks to me deeply. When this happens, I’lleither turn to some of my favorite books, or I’ll start a new novel. This getsme connected with language again, and I can start to fill the well.

12 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

Honeysuckle.

13 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I think everything influences my art. Myengagement with writing is a byproduct of my engagement with living in theworld.

14 - What otherwriters or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside ofyour work?

So many. But to keep it brief: Larry Levis,Susan Mitchell, Bhanu Kapil, Anne Carson. These are writers I can always turnto when I am feeling lost.

15 - What would youlike to do that you haven't yet done?

See the northern lights.

16 - If you couldpick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, whatdo you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would be a therapist. And I think I would bean excellent therapist.

17 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

I love writing. Writing has led me toeverything that is good in my life. It has guided me, shaped me, changed me. Idon’t think it is possible to be bored if you’re a writer. At least not forlong.

18 - What was thelast great book you read? What was the last great film?

Animal by Lisa Taddeo. And I just re-watchedMoonstruck and fell in love all over again.

19 - What are youcurrently working on?

Resting. It’s so easy for me to be in motion.Lately I’ve gotten much better at saying no and taking time for myself. I’venoticed this has benefited my writing immensely. I would like to continuefinding balance between being in the world and cultivating solitude.

September 29, 2024

Daisy Atterbury, The Kármán Line

The Kármán line is thealtitude at which the Earth’s atmosphere ends and outer space begins. The Kármánline is the edge of space, as opposed to near space, the high altituderegion of the atmosphere. When they say altitude they’re thinking interms of the human. What is measurable from the ground. Beyond the Kármán line theEarth’s atmosphere is too thin to support an object in flight. (“after stardeath.”)

I’mstruck by Santa Fe, New Mexico-based poet, essayist and scholar Daisy Atterbury’s

The Kármán Line

(Chicago IL/Cleveland OH/Iowa City IO: Rescue Press, 2024),a hybrid/lyric memoir around space travel, cosmology, planetary bodies and thelogic of landscape, all wrapped around the impossible abstract of the Kármán line,that edge between earth and outer space. As she writes, mid-way through: “Webecome identified with a wound, you said, and I am like sure, let me. I persistin autobiography.” Set in the nebulous between-space of prose poem and essay/memoir,Atterbury weaves her narratives around what is difficult to precisely capture,allowing for the betweenness to capture betweenness in startling ways. Writing ofasteroids in a piece titled “Binary Asteroids,” she offers: “Perhaps likepeople in my life, these stones can be classified as falls or finds: falls,seen falling to the Earth and then collected; finds, chance discover with norecord of a fall. In 1492, a large stone meteorite fell near Ensisheim, Alsace,one of the first known recorded falls. In 1895, my grandfather’s family leftAlsace-Lorraine after it was annexed from France by Germany. When my mother wasforced to enlist in the German army, they fled to the United States.” Opening witha list of “places (in no particular order).” Atterbury’s The Kármán Lineis constructed via a sequence of sections, most of which are composed via prose—“afterstar death.,” “troposphere.,” “stratosphere.,” “mesosphere.,” “thermosphere.,” “exosphere.”and “epilogue.”—as she works through the layers of this particular line, attemptingto discern the threads that accumulate into that single line of thought. And,oh, what distances she travels, even as she focuses on such intricated detail. Asher piece “Roads of the Dead” reads, in part:

I’mstruck by Santa Fe, New Mexico-based poet, essayist and scholar Daisy Atterbury’s

The Kármán Line

(Chicago IL/Cleveland OH/Iowa City IO: Rescue Press, 2024),a hybrid/lyric memoir around space travel, cosmology, planetary bodies and thelogic of landscape, all wrapped around the impossible abstract of the Kármán line,that edge between earth and outer space. As she writes, mid-way through: “Webecome identified with a wound, you said, and I am like sure, let me. I persistin autobiography.” Set in the nebulous between-space of prose poem and essay/memoir,Atterbury weaves her narratives around what is difficult to precisely capture,allowing for the betweenness to capture betweenness in startling ways. Writing ofasteroids in a piece titled “Binary Asteroids,” she offers: “Perhaps likepeople in my life, these stones can be classified as falls or finds: falls,seen falling to the Earth and then collected; finds, chance discover with norecord of a fall. In 1492, a large stone meteorite fell near Ensisheim, Alsace,one of the first known recorded falls. In 1895, my grandfather’s family leftAlsace-Lorraine after it was annexed from France by Germany. When my mother wasforced to enlist in the German army, they fled to the United States.” Opening witha list of “places (in no particular order).” Atterbury’s The Kármán Lineis constructed via a sequence of sections, most of which are composed via prose—“afterstar death.,” “troposphere.,” “stratosphere.,” “mesosphere.,” “thermosphere.,” “exosphere.”and “epilogue.”—as she works through the layers of this particular line, attemptingto discern the threads that accumulate into that single line of thought. And,oh, what distances she travels, even as she focuses on such intricated detail. Asher piece “Roads of the Dead” reads, in part:The Severan Marble Planof Rome is a carved marble rendering, a map of ancient Rome based on propertyrecords. Its size complicates its ongoing digital reconstruction.

The marble map is ablueprint of every architectural feature of the ancient city, from buildings tomonuments to staircases. The map’s carved blocks once covered a wall inside theTemplum Pacis, but all surviving pieces have been shipped to the floor of aStanford University warehouse to be scanned and catalogued. The 1,186 survivingmarble fragments make up only ten percent of the original marble plan. Using 3Dmodeling, the Computer Science department is digitally reconstructing thewhole.

The Severan Marble Planproject is a study in method. Virtual teams of engineers, archaeologists, andresearchers from the Sovraintendenza of the City of Rome solve the puzzle byusing shape-matching algorithms to digitally construct the jigsaw based onmatching forms. That the process is “painstaking and slow” is no deterrent.

The original plan isdetailed, accurate, and consistent in scale because it was copied from precisecontemporary surveys of the city of Rome, produced from cadastral records. Carvingmistakes and small irregularities remain in the original map. Its reproductionis made all the more difficult because of this lingering trace of the hand.

In the 1750s, a Europeanmapmaker cut a wooden map of the British Empire into pieces as an educationaltool for the children. In the 1990s, puzzle-making attained status as anaristocratic pastime.

I’m going to SpaceportAmerica.

Whatbecomes interesting, also, is how her sections of pieces, set more traditionallyinto the shapes of poems, suggest themselves as asides to the main narrative asvariations on the Greek Chorus, offering an alternate perspective on the mainaction, otherwise tethering together those elements of narrative.

You cant rely on

structure these folded

matchbooks I take one

greased packet of firesauce

This makes a very large

salsa verde, ten calories

The way you discovered

money, you pissed me off

when we touched, I sortof

peeled back, a paintstrip falling

from the pole. But wekeep

contact. I muscle myself

into a tight shirt, pressmy face

against a glass pane,make notes

Towards future health

wondering if the problemis lack

of calories or ritual

lack. Dry as a bone

and full of vacancies

September 28, 2024

Toronto International Festival of Authors’ Small Press Market (part two, : Conyer Clayton + brandy ryan,

[left: Gary Barwin, signing his new selected fiction collection with Assembly Press : see part one of my notes here] Here are some furthernotes from my recent participation at the Small Press Market that Kate Siklosi and Gap Riot Press organized and hosted through the Toronto International Festival of Authors. Hooray small press!

[left: Gary Barwin, signing his new selected fiction collection with Assembly Press : see part one of my notes here] Here are some furthernotes from my recent participation at the Small Press Market that Kate Siklosi and Gap Riot Press organized and hosted through the Toronto International Festival of Authors. Hooray small press!Toronto/Ottawa ON: The latest from Kentucky-born Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton (following two trade poetry collections and sixprior solo chapbooks) is the chapbook (Toronto ON:Gap Riot Press, 2024), a chapbook-length sequence the acknowledgements offers as“the first of a three-part series of interconnected poems.” The poem, thepoems, here are evocative and visceral, writing grief and loss and enormouslove. “My mother’s name is mine and buried in my throat.” she writes, to open “iv.,”“Her name is buried in my throat. / You scratch at her when you call to me. /When I kneel on the carpet. / When I stretch my neck to reach her. / When I reachinto my throat to touch her.” Set as an expansive sequence, Conyer moves fromshort lines to lyrics set closer to prose poems and scatters of lyric clustersset across the page, offering a narrative that writes parental loss asphysical, interconnected and devastating. “But I couldn’t do a damn thing tohelp. It hurt / right here, pointing, right here, kneeling. / right here,still.”

Browned edges.

Water droplets

on the corners

of the windows

I wipe

like a sermon.

Every day

like a sermon

The temperature

drops.

I kneel

to stretch my neck.

Every day

like a sermon

I kneel

to stretch my neck.

Like a prayer to

something

Toronto ON: It was very cool to watch brandy ryan work onfurther erasures throughout the fair, sitting at the Gap Riot Press table nextto mine. The author of three previous chapbooks— full slip (BaselinePress, 2013), once/was (Empty Sink Publishing, 2014) and After Pulse (w Kerry Manders, knife|fork|book, 2019)—ryan’s latest is the visual erasure in the third person reluctant (Toronto ON: Gap Riot Press, 2024). There is acurious blend of erasure and visual collage in ryan’s pieces, offeringfull-page reproductions of prose pages (a paperback of some sort; google doesn’tprovide easy answers as to what this book might be) with the bulk of the textexcised via coloured marker, overlayed with what appear to be full-colourglossy magazine images. ryan works an overlay across pages (and what might be ‘chapterheadings’—“LITERARY DIVERSIONS,” “LITERARY CONSUMPTION” and “LITERARYPOSSESSION”) with a text that suggests a commentary on gender, body autonomyand agency, and rage. “uncomfortable in ///// anger / the object of / her / housewifely/ high profile,” ryan writes, mid-way through the collection, “display / aperformance / a sharp observation, /// put on / like a ‘mask’ / they are ‘puttingon their face’) […]”