Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 36

October 28, 2024

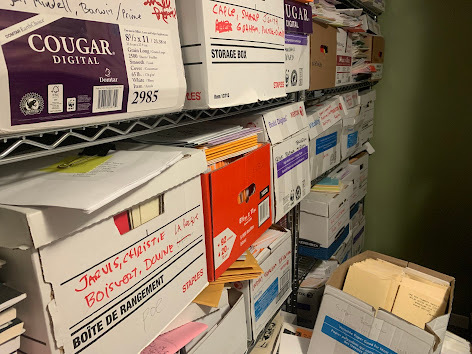

new from above/ground press: carisse, Landers, Logan, Benedict, Strath, Levy, Shirley, FitzGerald, Jaeger, fitzpatrick, Inniss + Touch the Donkey #43,

poetry and labour / is concrete, russell carisse $5 ; SIDEWALK NATURALIST, Sue Landers $5 ; THERE’S NOTHING OUT THERE, Nate Logan $5 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #43, with new poems by Lisa Samuels, Tom Jenks, Nate Logan, Henry Gould, Sandra Doller, Kit Roffey, Leesa Dean and Scott Inniss $8 ; Fragments of a Mirrored-Voice For a Friend, Alexander Hammond Benedict $5 ; Inconsistent Cemeteries, Mckenzie Strath $5 ; To Assemble an Absence, John Levy $5 ; CASSETTE POEMS, factory practice-room cassette-recording responses, Vik Shirley $5 ; Each Mouthful Dripping… poems from slogans, Ian FitzGerald $5 ; SELECTED MEMOIRS, Peter Jaeger $5 ; Spectral Arcs, ryan fitzpatrick $5 ; Back Shelve, Scott Inniss $5 ;

poetry and labour / is concrete, russell carisse $5 ; SIDEWALK NATURALIST, Sue Landers $5 ; THERE’S NOTHING OUT THERE, Nate Logan $5 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #43, with new poems by Lisa Samuels, Tom Jenks, Nate Logan, Henry Gould, Sandra Doller, Kit Roffey, Leesa Dean and Scott Inniss $8 ; Fragments of a Mirrored-Voice For a Friend, Alexander Hammond Benedict $5 ; Inconsistent Cemeteries, Mckenzie Strath $5 ; To Assemble an Absence, John Levy $5 ; CASSETTE POEMS, factory practice-room cassette-recording responses, Vik Shirley $5 ; Each Mouthful Dripping… poems from slogans, Ian FitzGerald $5 ; SELECTED MEMOIRS, Peter Jaeger $5 ; Spectral Arcs, ryan fitzpatrick $5 ; Back Shelve, Scott Inniss $5 ; keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material; oh, and you heard that 2025 subscriptions are now available, yes?

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

August-October 2024

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; in US, add $2; outside North America, add $5) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles, or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

With forthcoming chapbooks by: Brook Houglum (two!), Nathanael O'Reilly, Orchid Tierney, Andy Weaver, Catriona Strang, Penn Kemp, Jason Heroux and Dag T. Straumsvag, Alice Burdick, Susan Gevirtz, Carter Mckenzie, Maxwell Gontarek, Conal Smiley, Noah Berlatsky, JoAnna Novak, Julia Cohen, Ryan Skrabalak, Terri Witek and David Phillips; and probably others! (yes: others,

October 27, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Trisia Eddy Woods

Trisia EddyWoods is the author of A Road Map for Finding Wild Horses (Turnstone Press, 2024.) A former editor for Red Nettle Press,Trisia’s writing has appeared in a variety of literary journals and chapbooksacross North America including Contemporary Verse 2, The GarneauReview, and New American Writing. Her artwork has been exhibitedboth close to home and internationally, and is held in the special collectionof the Herron Art Library. Currently she lives in Edmonton /amiskwaciywâskahikan with her family, which includes an array of four-leggedcompanions. Her photography, including wild horses, can be found online atprairiedarkroom.com or IG: @prairiedarkroom

1 - How didyour first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook was a long form poem published with dancing girl press, over ten years ago now. I really loved it,it felt special and the poem still holds a lot of meaning for me. Although thesetting is quite different, this current book is similar in the sense that I amexploring different layers of connection. However, I definitely see and feel whereI have grown as a writer, and I feel more confident in my voice. This being myfirst full-length collection, I’m incredibly excited to see it out in theworld.

2 - How didyou come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I was encouragedwhen I was still in junior high school by my English teacher, Mrs. Leppard. Iremember her putting together a compilation of pieces written by students, andwhen one of my poems was chosen I felt incredibly proud. I continued writingpoetry throughout university, and after my kids were born. It wasn’t veryaccomplished or well edited, but poetry was a way for me to write in the briefspells of time I had in between working and mothering. As they have grown Ihave been able to spend more focused time, be more thoughtful and consistent. I’ddefinitely like to write essays or fiction; perhaps that is on the horizon.

3 - Howlong does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I amconstantly writing things that come to mind, and collect them in notebooks oron my phone if I don’t have a pen and paper. I also often make voice memos tomyself, and transcribe them every coupleof months. This particular project was done over several years, so I had a lotof disorganized pieces to go through and make sense of!

Lately as Ihave been dealing with the effects of long covid I find myself coming acrosssnippets of writing, and I cannot remember when they are from, or the contextunder which I wrote them. So I am accumulating a collection of verses that aresimply phrases I like the sound of, or evoke certain feelings, which is provingto be an interesting way to put together a project.

4 - Wheredoes a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

I thinkthat my ideas grow out of what I happen to be obsessing over at the time. I don’tpurposefully create a book, but I do like to deeply explore concepts and getlost in research, so that seems to organically take shape as a larger body ofwork. Sometimes it feels as though the idea of putting together a collection isintimidating, as I have a few half-formed manuscripts that were supposed to be ‘books.’In the last several years, though, I have become more comfortable with takingthings apart and letting them go, whether it is individual poems or acollection.

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

Havinghelped organized readings in the past, I found them really quite inspiring andimportant in terms of hearing the work of others, as well as sharing my own.Poetry in particular has always seemed to me a kind of art form that enjoysbeing read aloud. I love hearing writers interpret their work in their ownvoice, I think you hear things that you might miss just reading from the page.With this book I have had a few opportunities already to read at differentevents, and it seems to bring a life to the project that is invigorating on adifferent level.

6 - Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

That’s adifficult one. I don’t know that I have contemplated much in the way oftheoretical concerns, aside from my own emotional processes. In the past I wasoften mired in wanting to say something ‘important,’ and I struggled withfeeling reluctant to share my writing. Now I appreciate the fact that all of ushave important experiences and perspectives to share, so perhaps I might saythat one current consideration is to be generous with our reading and writing,and to make space for embracing a variety of questions and answers, especiallyfrom voices that are not traditionally heard.

7 – What do you see the current role of thewriter being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think therole of the writer should be?

I work in alibrary, so I see first hand the influence of writers in people’s lives. It’squite amazing, really, how many books circulate, and how attached people get tocertain authors. How excited they are when their holds arrive, how disappointedthey are when we don’t have something they are looking for on the shelf. Howmuch they love to talk about a book they really enjoyed, with staff and withstrangers. I think if writers could see the interactions we have with thepublic they would feel quite proud of the pivotal role they play in creatingcommunity.

8 - Do youfind the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (orboth)?

A Road Map for Finding Wild Horses was my first opportunity towork closely with an editor, and it was a transformative experience. I was veryfortunate to work with Di Brandt, and she asked a lot of questions that helpedme clarify what I was wanting to convey in the manuscript. So in that sense, itwas definitely both; difficult because I was confronted with the potentialweaknesses in my writing, and at the same time essential, because I was able todig deep to answer those questions.

9 - What isthe best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I was working with Di, at one pointshe told me ‘you need to trust your writing more,’ and I was really struck bythat. I think there are a lot of moments (for myself, at least!) wheresecond-guessing the words on the page becomes a habit, and the idea of givingourselves permission to believe in what we write can be very liberating.

10 - Howeasy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to photography)? Whatdo you see as the appeal?

In many ways I see both my visual artpractice and my writing practice as a conversation—there are times when I don’thave much to say in writing, and I turn to photography or printmaking toexpress what I am processing at the moment. Other days writing takes over, andI will spend weeks without picking up my camera. There is a certain amount ofcomfort in knowing that if the words aren’t at my fingertips, I still have waysof finding a creative outlet. It also means I am looking at the world in amulti-faceted way: sometimes I see or experience a moment and words come tomind, while other times I am struck by the particular way the light is just so,and feel the need to create a photograph.

11 - Whatkind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How doesa typical day (for you) begin?

It isreally only in the past couple of years that I’ve been able to develop any kindof writing routine. In the past I always just found bits of time here andthere, late at night when everyone had gone to bed, or perhaps during the oddretreat away from home. Now I am able to sit and focus more consistently, butit is definitely a practice I am still working on.

12 - Whenyour writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

I had tokind of laugh at this question, because my writing has been a constant sort ofjourney of starts and stops. I’ve learned to find inspiration in little things,as that is often what life is composed of; unfolding moments that make youpause. Sunsets that take your breath away, music that makes you teary. Reallyappreciating small accomplishments, or even the ability to have the time torest and breathe in between the bustle.

13 - Whatwas your last Hallowe'en costume?

A witch, Ithink? I still have this fabulous witch hat I used to wear on Hallowe’en when Idid library story times.

14 - DavidW. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes, all ofit! Especially since much of what I write about is the interconnectedness oflife, how loss of that connection spurs grief, how rediscovery of it can openus up in so many ways. All of these modes of expression are avenues forexploring our relationships with one another and the world around us.

15 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

I havealways been buoyed by friends who are fellow writers. I think it has been that encouragementand support that kept me on the path, because there were many moments when Ifelt discouraged or ready to shove ideas in the drawer. Dear friends like Jenna Butler, Shawna Lemay, Marita Dachsel… reading their writing has been sustainingin some dark moments because it feels like having a conversation with them.

16 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Oh gosh, somany things. Before I became ill, I was actually booked on a trip to SableIsland, to photograph the wild horses there. I still plan on doing that. I alsodream of photographing Polar bears in the north; that trip definitely requiresmore planning, but the time I have to actually make it there feels pressing asour climate radically shifts. I also look forward to the day I go to Montrealto see one of my sons perform; he’s studying jazz at university and will bedoing his final recital soon. That will be a proud day.

17 - If youcould pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately,what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I oftenthink I would have liked to have been a teacher; my husband is a teacher andthe stories he brings home have become a part of our family mythology now. Iwas always struck by what a difference he made in many of his student’s lives.But now my oldest son is also becoming a teacher, so I will live vicariously!

18 - Whatmade you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writing wassomething I often turned to as a child. I had no siblings so spent a lot oftime alone, immersed in creating other worlds, and writing became a sort ofrefuge. During the years of raising a family, writing was often the same kindof respite, but in the sense that I had a place to go and decompress, exploremy thoughts while caught in the tangle of parenting and working and all theother things life entails.

19 - Whatwas the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Mostrecently I have been reading and thoroughly enjoying Jasmine Odor’s newestnovel, The Harvesters. We just watched American Fiction which was based on the novel Erasure, it was really well done.

20 - Whatare you currently working on?

Lately Ihave had to focus on health and recovery, which has meant finding new ways toincorporate writing and creative expression, as it is difficult to sustain anykind of activity, mental or physical. I find being in natural spaces is one ofthe things that is truly healing, so a lot of what I am writing is based on myexperience with trying to access those spaces while also being limited in mycapacity. I also find myself writing about aging, the mother wound, and climateanxiety, capitalism and the politics of care, how to embrace beauty and loveand being flawed.

October 26, 2024

Jordan Windholz, The Sisters

The Sisters in the Night

Together, but they didn’tknow how they arrived, in the center, or where they could imagine the center,of a dark forest, howls with teeth in them, a grey silence that ate theirquestions. They didn’t even know if they were the villains, the wayward, theweird, the witches cursed to conjure sprites and devilish curs, if they were anancient magic feeding saplings into a heretic bonfire, its pillar of wet, whitesmoke rising like a spell. The sky was black above them, stuck with stars thatseemed the pinpricks of a bloodletting, their hot light hissing and steaming inthe mists snaking through the woods. The moon was a sister of what they didn’t know.They were not afraid. They had knives beneath their muslin, amethyst charms, alanguage that bent the world back into wishing. They imagined whatever was nextwas a perch with a nest of mottled eggs in its maw, a birthing of naked, flyingforms or a tender meal for skulking cats.

Iam intrigued by this second collection (and the first I’ve seen) by Carlisle, Pennsylvania poet Jordan Windholz,

The Sisters

(Black Ocean, 2024),following on the heels of his full-length debut,

Other Psalms

(DentonTX: University of North Texas, 2015). The Sisters is an assemblage ofshort prose poems interspersed with illustrations, and includes this brief caveatin the author’s “Notes & Acknowledgments”: “Written first as bedtimestories for my daughters, these poems were largely private affairs until they weren’t.I owe almost everything to Erin Ryan for her attentive reading and care, andfor her urging me to put them out in the world.” Across fifty-four prose poems,Windholz offers such fanciful titles such as “The Sisters in the Emperor’sGardens,” “The Sisters as Points of Infinite Regression,” “The Sisters as Two amongthe Many,” “The Sisters as the History of Blue” and “The Sisters in the Dreamof a Giant.”

Iam intrigued by this second collection (and the first I’ve seen) by Carlisle, Pennsylvania poet Jordan Windholz,

The Sisters

(Black Ocean, 2024),following on the heels of his full-length debut,

Other Psalms

(DentonTX: University of North Texas, 2015). The Sisters is an assemblage ofshort prose poems interspersed with illustrations, and includes this brief caveatin the author’s “Notes & Acknowledgments”: “Written first as bedtimestories for my daughters, these poems were largely private affairs until they weren’t.I owe almost everything to Erin Ryan for her attentive reading and care, andfor her urging me to put them out in the world.” Across fifty-four prose poems,Windholz offers such fanciful titles such as “The Sisters in the Emperor’sGardens,” “The Sisters as Points of Infinite Regression,” “The Sisters as Two amongthe Many,” “The Sisters as the History of Blue” and “The Sisters in the Dreamof a Giant.” Theseare charming, even delightful story-poems that play with children’sstorytelling, and a way of narrative and character unfolding through a sequenceof self-contained prose poems reminiscent of Toronto poet Shannon Bramer’s full-lengthdebut, scarf (Toronto ON: Exile Editions, 2001), or even Montreal poetStephanie Bolster’s Three Bloody Words (Ottawa ON: above/ground press,1996, 2016)—one might also be reminded of Berkeley, California poet Laura Walker’sstory (Berkeley CA: Apogee Press, 2016) [see my review of such here], Victoria,British Columbia poet Eve Joseph’s Quarrels (Vancouver BC: Anvil Press,2018) [see my review of such here] or New York poet Katie Fowley’s TheSupposed Huntsman (Brooklyn NY: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021) [see my review of such here]—through shared shades of fable, fairytale and the fantastical. Aswith any appropriate foray into fable, there are shadows that unfurl, unfold, throughthese pages, and hardly bloodless, echoing the best of what those BrothersGrimm might have salvaged. “It didn’t surprise them, exactly,” begins “TheSisters as Regicides,” “how cleanly the blade slipped between the bones of hisneck, how, with just the slightest heft of their bodies on the hilt, hisscreaming—like a child’s, really—cratered into a singular whimper, then awheeze. With his head off, the King—but was it right to call him that now?—was nothingmore than what all corpses are: a heap of flesh, a sinewy mess, time’s raggedlace.”

October 25, 2024

Ben Robinson, As Is

THE ORIGINAL TREATYbetween the Mississaugas

and the British describedthe upper boundary of

the parcel as an imaginedline from Lake Ontario

northwest to DeshkanZiibi / La Tranche / The

Thames. To confirm it,Jones & co. set out on

foot from the lake,crossing the Speed and the

Grand before reaching theConestoga. Realizing

their line would nevermeet the specified river,

thus could not close theperimeter, they turned

home to inform the Crownthat the Indenture

entitled it to animpossible tract.

Thelatest from Hamilton poet Ben Robinson, following The Book of Benjamin (WindsorON: Palimpsest Press, 2024) [see my review of such here], is

As Is

(Winnipeg MB: ARP Books, 2024), a collection that opens, appropriately enough,with a quote by the late London, Ontario artist Greg Curnoe: “It is a longdistance call from London to Putnam (25km). / It is not a long distance callfrom London to Glencoe (50km).” The quote emerges from Curnoe’s infamous Deeds/Abstracts(London ON: Brick Books, 1995), and Robinson utilizes As Is with similarintent, even if far different approach: attempting to explore and articulatehis own relationship to geographic space and its wealth of history, from his ownimmediate back through well before European occupation. Whereas Curnoe exploredthe specific Lot upon which sat his house, Robinson explores specific elementsof his Hamilton, Ontario, where, as his author biography has offered in thepast, he has only ever lived. “I push my son through our neighbourhood.” he writes,to open “By-law to Provide for and Regulate a Waste / Management System for theCity of Hamilton,” “It’s just us / and the dog people. A three-legged chair ona lawn, / a box spring at the curb with NO BUGS spray painted / on it in black.”Through long sweeps of short lines and historical space interspersed with shorter,first-person lyrics, Robinson provides As Is the feel of a kind of fieldnotes, moving across and through layers of personal history, the history ofHamilton, and the occupation of centuries. “He didn’t realize that in thiscountry,” he writes, as part of “Remediation,” “when a white man / runs hisboat into something, it gets name after him. / Fifty years later, randlereef.cais adorned / with a logo of a tern flying low over water.” Composed as a poeticsuite on and around overlooked and neglected histories, Robinson folds in andincorporates research and first-person observation, moving in and across time,references and intimacies deep and distant, from kept lawns and parenting to cityfounders, landscapes and boundaries, and what passes for history, passing noteslike waterways.

Thelatest from Hamilton poet Ben Robinson, following The Book of Benjamin (WindsorON: Palimpsest Press, 2024) [see my review of such here], is

As Is

(Winnipeg MB: ARP Books, 2024), a collection that opens, appropriately enough,with a quote by the late London, Ontario artist Greg Curnoe: “It is a longdistance call from London to Putnam (25km). / It is not a long distance callfrom London to Glencoe (50km).” The quote emerges from Curnoe’s infamous Deeds/Abstracts(London ON: Brick Books, 1995), and Robinson utilizes As Is with similarintent, even if far different approach: attempting to explore and articulatehis own relationship to geographic space and its wealth of history, from his ownimmediate back through well before European occupation. Whereas Curnoe exploredthe specific Lot upon which sat his house, Robinson explores specific elementsof his Hamilton, Ontario, where, as his author biography has offered in thepast, he has only ever lived. “I push my son through our neighbourhood.” he writes,to open “By-law to Provide for and Regulate a Waste / Management System for theCity of Hamilton,” “It’s just us / and the dog people. A three-legged chair ona lawn, / a box spring at the curb with NO BUGS spray painted / on it in black.”Through long sweeps of short lines and historical space interspersed with shorter,first-person lyrics, Robinson provides As Is the feel of a kind of fieldnotes, moving across and through layers of personal history, the history ofHamilton, and the occupation of centuries. “He didn’t realize that in thiscountry,” he writes, as part of “Remediation,” “when a white man / runs hisboat into something, it gets name after him. / Fifty years later, randlereef.cais adorned / with a logo of a tern flying low over water.” Composed as a poeticsuite on and around overlooked and neglected histories, Robinson folds in andincorporates research and first-person observation, moving in and across time,references and intimacies deep and distant, from kept lawns and parenting to cityfounders, landscapes and boundaries, and what passes for history, passing noteslike waterways.

Founder’s Day

It is not a metaphor

that the city’s originalsquare

sketched by Mr. GeorgeHamilton

was centred around aprison,

that though the jail’swooden walls were sound

its foundation was socompromised

an inmate need only liftthe loose board

in the corner to make hisexit,

that once free, if hefollowed the main road south,

it would have led straightto the founder’s door.

October 24, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Patrick James Dunagan

Patrick James Dunagan

lives in San Francisco and works as E-resources Assistant in Gleeson Library at the University of San Francisco. He recently edited

Roots & Routes: Poetics at New College

(w/ Lazzara & Whittington) and David Meltzer’s Rock Tao. His new book

City Bird and other poems

is now out from City Lights.

Patrick James Dunagan

lives in San Francisco and works as E-resources Assistant in Gleeson Library at the University of San Francisco. He recently edited

Roots & Routes: Poetics at New College

(w/ Lazzara & Whittington) and David Meltzer’s Rock Tao. His new book

City Bird and other poems

is now out from City Lights.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Whether it was Josh Filan publishing my chap Young American Poets (2000) or Simone Fattal publishing my full length GUSTONBOOK (2011) having somebody you don’t personally know find your work valuable enough to publish it is a humbling experience that also encourages you onward.

City Bird & other poems differs from my previous published books in so far it is not one entire long poem or poem-series, City Lights poetry editor Garrett Caples invited a manuscript of shorter poems grouped with the long poem ‘City Bird’. I gave him a much too long manuscript along with two other short manuscripts of poems from out notebooks I had typed up. He arranged what is City Bird and other poems.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I suspect it was simply shorter lines, fewer words was more appealing. Learning concision, however, was still required.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’ve written out of pretty much any and every scenario. In the case of City Bird, it began as a tinkering with the idea of a novelette about a character named Hugh eating a sandwich. I wrote it out in ‘prose’ lines I then later went back over and put into the poetic ‘form’ they now appear in. This also involved some editing of words, etc.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

As I mentioned, all my previous published books are one long poem or poem-series and in these cases, as with the poem ‘City Bird’, I did indeed understand it was a whole piece being composed. Generally I would fill a notebook. Then type it up.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I have recently been enjoying doing readings and feel as if they’re getting pretty good. Last nite I read without any planning from a collaborative book Three Heads Gone written and published years ago that I hadn’t looked at in years. I just skipped about within the poems at near random yet it felt natural and sounded solid, I believe. I have also often been making little self-made chaps for each solo reading. In other words, reading different poems, usually fairly new ones, every time and arranging them in order with a cover and title, etc.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I listen to the poem. It more or less writes itself. Generally, and hopefully, it is what I’d like to read. I believe writing and reading are more or less the same thing.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

‘The Writer’ is a different thing from ‘The Poet’. I think it is always important to be as aware of as much as possible at all times and always to be learning new things. The writer imposes order. The poet listens in.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Poetry can’t really be edited as such. With book reviews, of which I have written and published hundreds, I have found editors useful at times but probably not essential and I have definitely found them to be at times trying and quite possibly difficult. Editors of poetry magazines/journals are difficult when they reject work, which is the case for me with 99% of my poetry submissions.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

If asked, say yes.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I started writing book reviews many years ago because I found myself always writing in response to reading (still do) but I was having a horrible time publishing individual poems that I sent out (still do) and I wanted to get ‘out there’ and have some skin in ‘the ballgame’. I have at times pretty much merged the two. ‘Twenty-five for Lew Welch’ in City Bird, for instance, originally appeared online as a ‘review’ of the City Lights reissuing of Ring of Bone. I think that’s fun.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have no writing routine aside from poems usually going from being handwritten in a notebook to typed on the typewriter to then typed up again and saved as an electronic file. The day starts with bathroom business, radio news, some coffee and a walk through golden gate park, if it's a workaday.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don’t sweat not writing. I have a nice stack of unpublished manuscripts.

13 - What was your last Hallowe'en costume?

Every day’s Halloween.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Reading is Writing.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Friends have really pulled everything along for me and made it all possible.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Not much that I’m yet aware of aside from some trips with my wife Ava. Going to Iran for a bit, for instance.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’d have most likely been employed in some fashion in the San Francisco skateboarding community if my folks hadn't up and moved from Orange County, CA to New Ipswich, NH when I was fifteen.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I’d always been reading everything. Living on a dirt road in New Ipswich I started writing in high school classrooms.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I adore books like Genoa by Paul Metcalf and Hart Crane Voyaging by Hunce Voelcker. We just saw Deadpool and Wolverine in the theater, it was silly and highly amusing. I like films that go over 2 hours.

20 - What are you currently working on?

An expanded edition of The Duncan Era: One Reader’s Cosmology. Joanne Kyger suggested perhaps it could be a larger book. I’ve written further since it’s publication on Duncan, Jess, Spicer, and Blaser, which material I have now added, but also I now have some on Joanne herself, along with what I am hoping will be useful reflections on Thom Gunn and Duncan, having recently gone on a bit of a Gunn kick. Whether or not it finds a publisher, is another story.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

October 23, 2024

Zoe Whittall, no credit river

April Tornado Watch

COFFEE LID THE COLOUR OFa pinched lip, a spring so avoidant I’m attracted to it. This rain iswet-whispering a menacing taunt. Because a tornado took our barn in 1983, I am untetheredby wind. I don’t like the wind, I say, as I make origami hearts on the livingroom carpet. We got the rug thick, so we could sink into the floor, so it wouldcall us to nap. I order blush and Victorian nightgowns that come in the mail. Ipick up my phone between lines. I scroll to feel the weight of me lift. I knowhe’s beside me but he isn’t. He’s with all the followers. I can never be assimultaneously far away and close as they are. I am just here, in parallelplay, with our phones out and our bodies on pause, the wind throwing elbowsoutside.

FromPrince Edward County novelist, poet and television writer Zoe Whittall comesthe prose poem memoir no credit river (Toronto ON: Book*hug Press, 2024),a book self-described as “a contribution to contemporary autofiction asformally inventive as it is full of heart.” As the first line of the introductorypoem-essay, “Ars Poetica / Poem in the Form of a Note Before Reading” begins: “ITIS A CONFUSING THING to be born between generations where the one above thinksnothing is trauma and the one below thinks everything is trauma.” Approached asa hybrid/memoir through the structures of lyrc/narrative prose poems, this is Whittall’sfourth poetry title, following Pre-cordial Thump (Toronto ON: ExileEditions, 2008), The Emily Valentine Poems (Montreal QC: Snare Books,2006; reprinted by Invisible Publishing, 2016) and The Best Ten Minutes of Your Life (McGilligan Books, 2001). As the opening piece continues:

Of course a poet likes tobe in love. To fall for someone you have to be vulnerable, to hold a teaspoonof existential terror in your mouth and let it go. Intimacy is the only cliff jumpI like. Otherwise I’m in a lifelong battle with catastrophic thinking. On hispodcast the comedian Marc Maron says the only risks he takes are emotional and Ipull over to write that down. Oversimplified attachment theory memes on theinternet would say the anxiously attached person is just as afraid of intimacyas her avoidant partner but has someone else to blame for the distance. I startedwriting this book and stopped prioritizing love because I had a broken heart thatbordered on lunacy. That’s a poetic exaggeration but also not. In the spring of2021 my therapist, through Zoom, said, You’re doing well. You really seem likeyou have it together. I was telling her that it had been two years since thebreakup and I still felt grief. I was holding stones in my palm, telling myselftheir heaviness was the relationship, and throwing them into the lake to letthem go. I watched them sink like a wilful tangible metaphor but they didn’t help.If my therapist is the person I tell the worst things to, and she says I’mdoing well post-breakup and miscarriage and rewatching the same GilmoreGirls or Grey’s Anatomy every night over and over, then how can youever be perceived?

Setwith introduction and three numbered sections of shorter pieces, no creditriver is constructed through a sequence of self-contained prose poems as a first-personessay/memoir with lyric tilt, offered episodically, each piece unfolding as akind of lyric moment or scene. Rich with fierce intelligence and a deepintimacy, Whittall’s sequence of diary-poems unfold and meander, and there’s anability that I admire about her (or her narrator, alternately) ability to bepresent, whether discussing the wish to possibly have a baby, the devastationof a break-up, or seeing an elk outside her window at Banff Writing Studio, allwhile allowing the blend of daily life and writing life to shape and inform. “Formis content, I tell the elk. My girlfriend and I have an arrangement,” shewrites, as part of “Neurotic, / Bisexual, Alberta,” “a type of freedom wheneverwe travel. This makes me cconsider all strangers from a different angle. When I’mthe one left at home it makes me sleepless and on edge. I go see Dave read froma new play. I watch Jonathan give a talk. When I’m with a woman, I look only atmen, and vice versa. You should know you’re bisexual if you answer the questionAre you ever just happy with what you’ve got? I know gender isn’t thatsimple.”

Setwith introduction and three numbered sections of shorter pieces, no creditriver is constructed through a sequence of self-contained prose poems as a first-personessay/memoir with lyric tilt, offered episodically, each piece unfolding as akind of lyric moment or scene. Rich with fierce intelligence and a deepintimacy, Whittall’s sequence of diary-poems unfold and meander, and there’s anability that I admire about her (or her narrator, alternately) ability to bepresent, whether discussing the wish to possibly have a baby, the devastationof a break-up, or seeing an elk outside her window at Banff Writing Studio, allwhile allowing the blend of daily life and writing life to shape and inform. “Formis content, I tell the elk. My girlfriend and I have an arrangement,” shewrites, as part of “Neurotic, / Bisexual, Alberta,” “a type of freedom wheneverwe travel. This makes me cconsider all strangers from a different angle. When I’mthe one left at home it makes me sleepless and on edge. I go see Dave read froma new play. I watch Jonathan give a talk. When I’m with a woman, I look only atmen, and vice versa. You should know you’re bisexual if you answer the questionAre you ever just happy with what you’ve got? I know gender isn’t thatsimple.”Acrosswhatever flow or ebb, there is still a larger structure upon, through andwithin which the assemblage of short pieces can shape, cohere and, in the end,hold, simultaneously composed as document, process and an attempt to find herfooting after and through a sequence of upheavals. “THERE IS A BEAR BETWEEN thetheatre and the house a literary festival has rented for me.” begins the piece “Sechelt.”“An orange cat outside, I seem to attract them everywhere I go.” As a sequence,the poems assemble across a period of time that includes “abandoned love, thepain of a lost pregnancy, and pandemic isolation,” attempting to articulate andreconcile those gains, experiences and losses, while in the midst of the workof a daily writing life, and odd moments that pool and tide against the shores.“Nadine Gordimer said that writing is making sense of life.” This, as Whittallwrites, is her working to make the most sense of it all.

October 22, 2024

Ryan Eckes, Wrong Heaven Again

injury music

here i am documentingnothing

inside the defiance ofbrick

everyone cheats like atrain

broken into photographs

rowhomes are a belief

sighed into knees

a bottle in front of me

is finally you as you

i’m afraid of

an empty baseball field

where i grew up

wanting to hit

tell me you’re sorry

and i’ll move on

like a moth

in the stands

the infinite line oftrees

makes one fan

pull me out

of the car

Thelatest from Philadelphia poet Ryan Eckes, author of the full-length collectionsOld News (Furniture Press 2011), Valu-Plus (Furniture Press,2014) [see my review of such here] and General Motors (Split Lip Press,2018) [see my review of such here], as well as several chapbooks, is Wrong Heaven Again (Raleigh NC: Birds, LLC, 2024), a collection self-described as“songs of solidarity and struggle for and about workers and the working class—defiantand hopeful, absurd and alive.” “the dean showed us a picture of hisgrandchildren right before the labor- / management committee meeting on jobsecurity,” he writes, as part of the opening poem, “under the table,” “mostpeople have a name and address, it’s true // you can buy lottery tickets foreveryone in your family // you can read the sunday paper to your dog [.]” Dividedby images, and as suggested through the table of contents, the collection isorganized with opening and closing poems—“under the table” and “deep cuts,” respectively—andfour untitled cluster-sections into an accumulated book-length suite. Also, atthe rough mid-point, the collection opens to two lines in larger font, that spreadacross both pages:

“revolutionbegins with change in the individual,” said the

english departmentas it disappeared

Eckes’work over the years has become thicker, heftier, more nuanced; there’s anincreased weight to the poems in Wrong Heaven Again, one that clearlyshowcases a writer becoming more capable with his tools. “the choir got boredenough the windbags collapsed into soft balloons / found years later in adrawer,” he writes, to open the poem”wrong heaven,” “wrong heaven again,said the rabbit, returning to the dance floor // i accepted a position overthere, on the dance floor, which is a field // a ranger leers at me // only icould prevent forest fires [.]” His blend of surreal humour and straightforwardnarratives allow for a kind of collage-collection, each poem another smallpiece of the larger book-length construction. As part of his 2018 interviewover at Touch the Donkey, referencing the beginnings of what would becomethis collection, he writes:

After finishing GeneralMotors, I started writing poems called “injury music” and “for what wewill,” not entirely sure where I’m going. I’m thinking about pain, trauma andmore questions around work. “For what we will” comes from the old labor unionslogan, “8 hours for work, 8 hours for sleep, 8 hours for what we will.” It’ssad that 8 hours of work/40 hours a week is still considered normal, consideredactually natural by many people, a century after it was established as a*protection*. Why aren’t we at 4 hours by now? Why is the minimum wage still solow? Why do Americans worship the rich? I could go on. But these are the kindsof questions that I let propel my writing at the same time that I am trying tounderstand myself as a living thing made of relations.

Ifind it interesting that I can’t think of too many poets approaching workingclass poetics so directly, offering shades of the late Vancouver poet Peter Culley (1958-2015) and other elements of The Kootenay School of Writing. Thereare poets engaged in elements of working class poetics, certainly, whether Vancouver writer Michael Turner, Philadelphia poet Gina Myers or Chicago poet Andrew Cantrell, among others, but Eckes seems one of the more overt, swirling betweenstraight commentary and language flourish, and even offering an echo of theclassic poetry title on cross-cultural poetics by Toronto poet Stephen Cain, AmericanStandard/Canada Dry (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2005), as Eckes’ poem “independenceday” begins: “who made you einstein, monday-face // american standard is abrand of toilet // so i just start walking on water // out of respect for pangea// trash gets picked up // i mean if you’re gonna be a nobody // have someclass about it [.]” Eckes works his working-class politics from the groundlevel, from the foundation of language itself, allowing the paired foundationof working-class ethos and fluid language to mix together into something uniquelyhis own, while informed by a wealth of poets, observations and social politics.

HOV

i keep getting ads to bean uber driver, which reminds me of a term i learned in chile for adjunctprocessors—los processors taxis—and a poem by russell edson in which ataxi driver turs into canaries as his car flies thru a wall and back out again.that’s where i’m at, jobwise, a cluster of canaries flying toward you. inchile, students started evading subway fares and it turned into a rebellion. nowtheir government has to re-write the constitution. in the u.s., fascists arewearing t-shirts that way “pinochet did nothing wrong.” republicans and democratshave long agreed. so has the ny times: capitalism is the only way, they say,and some apples are bad. so the government keeps killing black people andjailing those who fight back. every employer encourages you to vote. Your employeris running against your employer. they’ll never pay enough. how are you gettinghome tonight?

October 21, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Dobby Gibson

DobbyGibson [photocredit: Zoe Prinds-Flash] is the author of Polar; Skirmish; ItBecomes You, a finalist for the Believer Poetry Award; and Little Glass Planet. His poetry has appeared in the American Poetry Review, TheParis Review, and Ploughshares. He lives in Saint Paul,Minnesota.

1 -How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Myfirst book didn’t change my life, much to my surprise at the time. I eventuallyrealized the disenchantment was a kind of gift. As poets, it is our job to beforever in search of a transformation we never quite attain.

2 -How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I didcome to fiction first! I even have an MFA in fiction and an underwhelminggraduate-thesis novel to prove it. I began writing poetry on the sly in mysecond year of the Indiana University fiction program. Poetry wasn’t what I wassupposed to be doing, in the eyes of the institution. I’m happy to report that itslost none of its transgressive thrill.

3 -How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

I’mwriting all the time and tend not to think in projects. I wake up most days andwrite a poem, and then, over a few years, the poems point toward the book.

4 -Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces thatend up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Everypoem begins in an encounter with language.

5 -Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I wantmy poems to connect with actual people—people who aren’t necessarily poets oracademics. If I’m interested in a poem I’m working on, I’ll eventually read itout loud when no one else is home. I suppose I’m imagining an invisibleaudience being there with me, but this imaginary reading is just as mysteriousto me as a real reading. Who is listening? As a poet, you can never be sure,unless you’re reading at a Monsters of Poetry event in Madison, Wisconsin,which is the greatest reading series in America. It’s not even close.

6 -Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

I’mtrying to capture the texture of lived experience. Its astonishments. Itsbefuddlements. Its outrages. All its bizarre simultaneities.

7 –What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do theyeven have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

In “The Nobel Rider and the Sounds of Words,” Wallace Stevens says the role of the poetis “to help people to live their lives” through the power of the imagination. Thismay require working within the culture, or it may require working outside of theculture. In my experience, it often requires not thinking about the culture atall.

8 -Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Overthe course of five books, I’ve worked with three different editors: April Ossmann, Jeff Shotts, and Carmen Giménez. Each of those relationships has beenessential. If April, Jeff, or Carmen have something to say to me about my work,I’ll stop whatever I’m doing and listen. I may not act on what they say, but Iwill listen.

9 -What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Neverwear light brown shoes with a dark suit.

10- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

On agood day, I have 30 minutes with my notebook in the morning before anyone elsein the house is awake. But I’m un-fussy about routines and protocols. Ivoice-text poems and parts of poems to myself while driving my car all thetime.

11- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

ReadingTomaž Šalamun cures anything. It’s like splashing cold water on my face.

12- What fragrance reminds you of home?

Kimchi.A red sauce after it’s been simmering on the stove for 30 minutes. The air justbefore it snows.

13- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Anythingcan spark a poem. In this most recent book, one was inspired by the sight of a tinyhotel soap.

14- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Aphorismsof all kinds. The comedian .

15- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Retire.

16- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

AnOlympic badminton player. But I would still write poems.

17- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I wishI could tell you. I have no memory of making the choice.

18- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

AlexanderChee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel and Grosse Pointe Blank,which I just rewatched. It still holds up (pun intended)!

19- What are you currently working on?

I’msurprised to find myself working in prose lately. And, as Dean Young’s literaryexecutor, along with Matt Hart, I’m also focused on bringing Dean’s first posthumouscollection of poems into print. It’s called Creature Feature.

October 20, 2024

Ashley-Elizabeth Best, Bad Weather Mammals

Sweet Sixteen

Mum said I had to callDad to find out where he was.

I didn’t want to thinkabout the day he would stop

coming around, the fistof his mouth. My mother was

always attempting to reassureherself by reassuring me.

She promised we would goto the funeral together; all of her

little foxes in the samepart of the forest. Before the funeral

we walked into a field asa cast of hawks stroked a November

morning into a gaslitday. Time measures itself in a scatter

like those hawks. My socialworker says I can be the axe

to break through the holdof my own misery. I’m learning

to be invisible, butthese hands refuse to lift the axe.

Mum knew how to make mejimmy her heart loose.

She could be gentle then,whispering tunes her grandfather

left tucked behind herears. I am learning what is not mine to tell.

I am not as free as I wouldlike to be.

Kingston, Ontario poet Ashley-Elizabeth Best’s latest full-length poetry collection is

BadWeather Mammals

(Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2024), a follow-up to herfull-length debut,

Slow States of Collapse

(ECW Press, 2016). BadWeather Mammals explores illness, depression, trauma, disability poetics,and a history of violence; working through and across an array of ongoing andlingering, old and new, challenges across a first-person lyric. To open thepoem “Good Sick/Bad Sick,” she writes: “The sick should be good. / It is a kindof undoing.” As the back cover offers, the collection “navigates thedevastations and joys of living in a disabled and traumatized body. By taking abackward glance, Best traces how growing up under the maladaptive bureaucracyof social services with a single disabled mother and five younger siblings ledher to a precarious future in which she is also disabled and living on socialassistance.” Opening the collection, the prose-poem “Chapter of Accidents” setsthe tone, introducing all that might follow: “I am thirty years old and this isthe first year of my life I have lived in an apartment that did not have amould problem, that did not have a man problem, that did not have a man withfists in your face problem.” This is what one needs to know before she begins,before she moves further back to where she had been, compared to where she isnow. Further on in the same piece:

Kingston, Ontario poet Ashley-Elizabeth Best’s latest full-length poetry collection is

BadWeather Mammals

(Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2024), a follow-up to herfull-length debut,

Slow States of Collapse

(ECW Press, 2016). BadWeather Mammals explores illness, depression, trauma, disability poetics,and a history of violence; working through and across an array of ongoing andlingering, old and new, challenges across a first-person lyric. To open thepoem “Good Sick/Bad Sick,” she writes: “The sick should be good. / It is a kindof undoing.” As the back cover offers, the collection “navigates thedevastations and joys of living in a disabled and traumatized body. By taking abackward glance, Best traces how growing up under the maladaptive bureaucracyof social services with a single disabled mother and five younger siblings ledher to a precarious future in which she is also disabled and living on socialassistance.” Opening the collection, the prose-poem “Chapter of Accidents” setsthe tone, introducing all that might follow: “I am thirty years old and this isthe first year of my life I have lived in an apartment that did not have amould problem, that did not have a man problem, that did not have a man withfists in your face problem.” This is what one needs to know before she begins,before she moves further back to where she had been, compared to where she isnow. Further on in the same piece:Disability meanthousewife, meant I do everything else and he makes the money. Eleven years of water-bloatedwalls, mould an encroaching boundary of black on the carpet. It didn’t takemuch to lay my mood flat then, for the dishes to coalesce into a pile of grimethat neither of us wanted to deal with, until he decided it was myresponsibility. Oh, what of my joints, the sullen pop of knees as theystraighten the body. Tender points signal illness, swollen knees requireneedles to release the fluid. I flattened myself, expanded despite my desire tothin into invisibility.

Thepoems in and across Bad Weather Mammals represents an unfolding, anunfurling, of reclaimed and repurposed self, despite and through whatever elsehad been, has come and still is. “Bronwen suggested the body / is the limit wemust learn to love.” she writes, to open the poem “I Am Becoming a House,” apoem which suggests a reference to the late Kingston poet Bronwen Wallace (1945-1989).“I’m not one to love my limits: / I’m practicing being an empty house.” Shewrites of disability and poverty, both through her childhood and intoadulthood, and the reduced options available to her through either, both. “Mywords,” she writes, to open the nine-part sequence “Pathography,” “always palereflections for the language / of my organs. They say I am so lucky, to nothave / a nephrostomy tube intubating my kidneys, delivering / my body of itsown fluids, like E. I was lucky a nurse / didn’t have to come every other dayto clean bandages / and disinfect the open wound like E. I got to stay inschool, / collect a scholarship and student loans, pay rent, groceries.” Shewrites of agency, even when and through a seeming lack of such, forcing her waythrough, and hopefully past, the worst of it. As she writes, further along inthe collection: “Consider: it is a privilege to have a story, to know your own/ narrative as surely as you know your name.”

October 19, 2024

Other Influences: An Untold History of Feminist Avant-Garde Poetry, eds. Marcella Durand and Jennifer Firestone,

It was also at Naropa in1994 where I was introduced to Harryette Mullen and was lucky enough to take aworkshop with her. A brilliant teacher, Mullen shaped the workshop around heruse of Oulipo-based techniques, folkloric influences, and attention to thedemotic and conversational word play. That workshop forever influenced mypedagogy and writing. Likewise, that summer I was first introduced to the work ofBob Kaufman, Ted Berrigan, and Bernadette Mayer, and I took a workshop with Dennisand Barbara Tedlock, who gave a panel on their translation of the Popol Vukand who said that whenever they speak of their experiences around this work, itinvolved rain: it did. I took a sonnet workshop with the brilliant Anselm Hollothat initiated my lifelong interest in this form and after which I wrote myfirst mature poems, a sonnet sequence. It was at Naropa that I heard Nathaniel Mackeygive his soul-searing lecture “Cante Moro” on Lorca’s concept of duende.That lecture opened a cross-cultural understanding of bent strings, brokeneloquence, and the role of dialogue singing, allowing me to make perceptuallinks between U.S. Delta blues and the Cham-influenced musical scale of southVietnamese music, which is also composed of a pentatonic scale with flattenedand in-between notes. Delta to delta. (Hoa Nguyen, “WHEN YOU WRITE POETRY YOUFIND THE ARCHITECTURE OF YOUR LINEAGE”)

I’mdeeply impressed with the collection

Other Influences: An Untold History of Feminist Avant-Garde Poetry

, edited by Marcella Durand and Jennifer Firestone (London UK/Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2024), a collection of originalessays “by a range of leading contemporary feminist avant-garde poets asked toconsider their lineages, inspirations, and influences.” The list of contributorsinclude Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Nicole Brossard, Allison Adelle Hedge Coke,Brenda Coultas, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Tonya M. Foster, Renee Gladman, Carla Harryman,Erica Hunt, Patricia Spears Jones, Rachel Levitsky, Bernadette Mayer, Tracie Morris, Harryette Mullen, Eileen Myles, Sawako Nakayasu, Hoa Nguyen, Julie Patton, KPrevallet, Evelyn Reilly, Trish Salah, Prageeta Sharma, StacySzymaszek, Anne Tardos, Monica de la Torre, Cecilia Vicuña, Anne Waldman andRosmarie Waldrop. “First I had this impression of Leslie Scalapino bouncingoutside of language poetry,” Eileen Myles writes, to open “ACCIDENTALSCALAPINO,” “like she was kind of there but couldn’t quite stay still in the projectof it, or the project of hers. I always noticed who one pals around with in thepoetry world and she was I think beloved by Alice (Notley) and Ted (Berrigan)though they’d be the first to describe Leslie as ‘a weirdo,’ a phrase theyreserved for the best people and they meant it with the utmost affection.”There is such a richness to this collection, one that explodes across a constellationof names, threads, writing communities and commentaries, both a heft ofinformation for the experienced reader and emerging writer, allowing the bestof what be possible across an anthology of poets and poetics. Every essaywithin this collection is exceptional, each articulation on how one begins, howthe poems begin, how one establishes relationships to writing, writers and thinkingacross writing. “What can it mean for a woman,” Rachel Levitsky offers as partof “PUSSY FORWARD POETICS, OR THE SEX IN THE MIDDLE: READING AKILAH OLIVER ANDGAIL SCOTT,” “for radical marginalized women, for a Black woman, for mothers,for a poet, for an experimental prose writer, for a poor woman, an aging woman,a queer woman, a woman who holds no fixed idea or surety over the meaning ofthe category ‘woman,’ therefore a theoretical and theory-making woman, anonbinary woman, a trans woman, a trans man or masculine who was once calledupon to be a female or a woman, a no-longer-cis woman, a poet and artist, solitarywoman, a gazed-upon and scrutinized woman, a dreaming woman, a desiring woman,a traveling woman, a reading woman, a homebody, a woman of autonomousintellect, a friend, to perform freedom or more free-ness amid such conditions?”And then there is Stacy Szymaszek, writing in “VIVA PASOLINI!” a sense of thepoem and poet connected to civic responsibility: “[Pier Paolo] Pasolini is thefirst poet who teaches me to turn existing poetry spaces into spaces for poetsto be possessed by civic poetry, a poetry that is imbued with reciprocitybetween the individual poet and society.” Further on, writing:

I’mdeeply impressed with the collection

Other Influences: An Untold History of Feminist Avant-Garde Poetry

, edited by Marcella Durand and Jennifer Firestone (London UK/Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2024), a collection of originalessays “by a range of leading contemporary feminist avant-garde poets asked toconsider their lineages, inspirations, and influences.” The list of contributorsinclude Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Nicole Brossard, Allison Adelle Hedge Coke,Brenda Coultas, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Tonya M. Foster, Renee Gladman, Carla Harryman,Erica Hunt, Patricia Spears Jones, Rachel Levitsky, Bernadette Mayer, Tracie Morris, Harryette Mullen, Eileen Myles, Sawako Nakayasu, Hoa Nguyen, Julie Patton, KPrevallet, Evelyn Reilly, Trish Salah, Prageeta Sharma, StacySzymaszek, Anne Tardos, Monica de la Torre, Cecilia Vicuña, Anne Waldman andRosmarie Waldrop. “First I had this impression of Leslie Scalapino bouncingoutside of language poetry,” Eileen Myles writes, to open “ACCIDENTALSCALAPINO,” “like she was kind of there but couldn’t quite stay still in the projectof it, or the project of hers. I always noticed who one pals around with in thepoetry world and she was I think beloved by Alice (Notley) and Ted (Berrigan)though they’d be the first to describe Leslie as ‘a weirdo,’ a phrase theyreserved for the best people and they meant it with the utmost affection.”There is such a richness to this collection, one that explodes across a constellationof names, threads, writing communities and commentaries, both a heft ofinformation for the experienced reader and emerging writer, allowing the bestof what be possible across an anthology of poets and poetics. Every essaywithin this collection is exceptional, each articulation on how one begins, howthe poems begin, how one establishes relationships to writing, writers and thinkingacross writing. “What can it mean for a woman,” Rachel Levitsky offers as partof “PUSSY FORWARD POETICS, OR THE SEX IN THE MIDDLE: READING AKILAH OLIVER ANDGAIL SCOTT,” “for radical marginalized women, for a Black woman, for mothers,for a poet, for an experimental prose writer, for a poor woman, an aging woman,a queer woman, a woman who holds no fixed idea or surety over the meaning ofthe category ‘woman,’ therefore a theoretical and theory-making woman, anonbinary woman, a trans woman, a trans man or masculine who was once calledupon to be a female or a woman, a no-longer-cis woman, a poet and artist, solitarywoman, a gazed-upon and scrutinized woman, a dreaming woman, a desiring woman,a traveling woman, a reading woman, a homebody, a woman of autonomousintellect, a friend, to perform freedom or more free-ness amid such conditions?”And then there is Stacy Szymaszek, writing in “VIVA PASOLINI!” a sense of thepoem and poet connected to civic responsibility: “[Pier Paolo] Pasolini is thefirst poet who teaches me to turn existing poetry spaces into spaces for poetsto be possessed by civic poetry, a poetry that is imbued with reciprocitybetween the individual poet and society.” Further on, writing:Civic poetry is gnostic in its intelligence and shows anuncomprosmising fealty to language. It gives me an ability to intervene, torefuse, to create a more just reality, to rewire the brain into making bettersense. These are not new concepts, although they are new in the way that oldpoetry can be eternally new and new poets can be possessed by old poets.

Oneof the strengths of this collection emerges from the variety of responses; howevermuch overlap might occur, each poet leaning into their own unique direction orapproach, with the assemblage allowing for an opening of conversation orcollaboration over any sense of contradiction. There’s an openness to thesepieces, one that can’t help spark an enthusiasm for the possibility of furtherwork. “To unmask our history,” Anne Waldman writes, “we also need to go topoetry.” Or, as Nicole Brossard begins her essay “LA DÉFERLANTE”: “What informsmy poetry is not necessarily meaning first. It is mostly how sentences of linesdisrupt my reading-writing to create a tension in meaning and prepare new pathstoward it. Those paths are what I will call the basis of influence, ofresonance, of what becomes the appeal in the intimate space of a text, of anauthor.” Asking contemporary poets to speak to or about lineages and influence suggestthat this collection an extension of an idea from a prior collection, anotheranthology co-edited by Firestone, the anthology Letters to Poets:Conversations about Poetics, Politics, and Community (Philadelphia PA:Saturnalia Books, 2008) [see my review of such here], a book she co-edited withDana Teen Lomax. I recall finding this collection utterly fascinating and a bitenvious at the time, equally so for this current work: a book crafted to speak tothe best of how community can work, as well as a deeper understanding of eachof the works of the contributors, through seeing how their poetics and sense ofliterary kinship were developed. As the editors offer as part of theirintroduction:

The poets in this collection found their ways to their ownpoetics, identifying their contexts and lineages unbounded by the strictures oftheir schools, work, and established literary institutions. As Audre Lorestates, “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crushed into otherpeople’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” This community of writers resistslabels: they invite nuance, error, slippage, and even messiness. They take theterms feminist and avant-garde, claim them, and make them uniquelytheir own. They know deeply that canons change, that inspiration is subtle,that the path is not so easy or clear. This collection is only the beginning ofan evolving dialogue, an opening to a new generation of feminist avant-gardewriters to connect to, collaborate with, and support each other. ultimately, itis our vision to gather feminist avant-garde poets who engage with language asa point of contention and potentiality.