Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 45

August 10, 2024

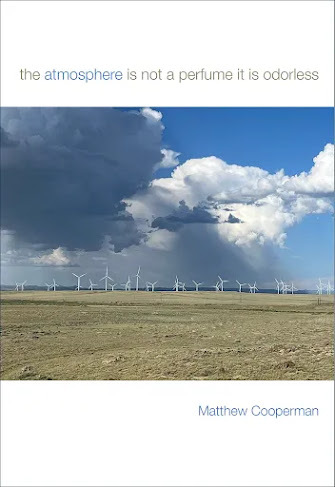

Matthew Cooperman, the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless

Precarity

To see and be seen

by others

not the voice

but the face

voice in the face

mouthward

the warbler

now

in the coffee tree

broken and free

*

In hunger by migration

to see the living

and be seen

to have taken it in

the scene and all

its decline

the moving picture

in sepia hues

the map made body

blushing blue

blood a precipitate folly

in wheat or oil

rainfall’s mean

in the morning dew

Forsome time now, I’ve admired Fort Collins poet and editor Matthew Cooperman hisability to compose book-length collections, and even certain poems and individuallines, of sprawling distance, ecological concern, geographic acknowledgement,cultural touchstones and lyric expansiveness, all set in a Colorado he lovesdearly. The author of a handful of titles, including Spool (Anderson SC:Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press, 2016),

NOS (disorder, not otherwise specified)

(with Aby Kaupang; Futurepoem, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

Wonder About The

(Middle Creek Publishing, 2023) [see my review of such here], his latest solo collection is

the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless

(Anderson SC: Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press,2024). The lyrics of the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless weaveand incorporate strands of contemporary and cultural alongside accompanying full-colourphotographs that feel as much as part of the text as the writing, extending asense of time and timelessness, but one that stretches his lyric of human destructionof the landscape to one that includes even deeper anxiety, citing gun culture,politics and domestic matters. “Innocence,” he writes, across the extendedtitle poem, “being, / lost or being found out, my sense of time goes in and outof phase with // what must be yours, I know I feel it, dispersed and sometimesnot / dispersed, as if I am gas also speaking to you, which of course I am, /the punchline of poetry. Are we always going to go over how I or you // do ornot smell the haloing over the Front Range?”

Forsome time now, I’ve admired Fort Collins poet and editor Matthew Cooperman hisability to compose book-length collections, and even certain poems and individuallines, of sprawling distance, ecological concern, geographic acknowledgement,cultural touchstones and lyric expansiveness, all set in a Colorado he lovesdearly. The author of a handful of titles, including Spool (Anderson SC:Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press, 2016),

NOS (disorder, not otherwise specified)

(with Aby Kaupang; Futurepoem, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

Wonder About The

(Middle Creek Publishing, 2023) [see my review of such here], his latest solo collection is

the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless

(Anderson SC: Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press,2024). The lyrics of the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless weaveand incorporate strands of contemporary and cultural alongside accompanying full-colourphotographs that feel as much as part of the text as the writing, extending asense of time and timelessness, but one that stretches his lyric of human destructionof the landscape to one that includes even deeper anxiety, citing gun culture,politics and domestic matters. “Innocence,” he writes, across the extendedtitle poem, “being, / lost or being found out, my sense of time goes in and outof phase with // what must be yours, I know I feel it, dispersed and sometimesnot / dispersed, as if I am gas also speaking to you, which of course I am, /the punchline of poetry. Are we always going to go over how I or you // do ornot smell the haloing over the Front Range?”Coopermanwrites of an American cultural expansiveness, even through one of deep uncertainty.“As in, O America, aren’t you tired of being an ode,” he offers, as part of “GunOde.” He writes of precarity and odes, through poems examine and explore culturalspace and seek out its humanity, aching to flesh out something different acrossthe habits of decades. Later, in the same extended poem, writing: “If the impulseto destruction is greater than the insight to love / we are doomed to a gardenof graves // If freedom is money spent on guns, what is American grace?” Hispoems stretch as endless as does that view, which is glorious and open, a tingeof fresh, cool air among the biting dust.

Inthe end, his is a love for country, culture and space as deep and as wide asany horizon, one unafraid to love critically and out loud. “Not motive orasseveration. Not a result of living as experiment,” he writes, as part of “NoOde,” “but living together. Every lab a vial filled. Not a sea / full of oil,nor an office full of bluster. Not a corporation / nor the October morningmoving / to incorporate a neighborhood.”

August 9, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tāriq Malik

Tāriq Malik has worked across poetry, fiction, and artfor the past four decades to distill immersive and compelling narratives thatare always original. He writes intensely in response to the world in fluxaround him and from his place in its shadows. His published works,including Rainsongs of Kotli (TSAR Publications,short stories, 2004), Chanting Denied Shores (Bayeux Arts,novel, 2010), and now his poetry in Exit Wounds (Caitlin Press, Poetry, 2022)and Blood of Stone (Caitlin Press, Poetry, 2024), challengeentanglements in the barbed wires of racism and cultural stereotyping in art,the workplace and across societies.

Tāriq Malik is thecurrent Writer-in-Residence at the Polyglot Magazine and a formerWriter-in-Residence (July 2023) at the Historic Joy Kogawa House and hasoffered Poetry Master Classes at various locations.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first published book, Rainsongs of Kotli, was a compilation ofloosely interwoven short stories set in the backwaters of Pakistani Punjab. Itwas challenging to describe the work and situate it for potential publishers. Ireceived several very negative responses. Eventually, Rainsongs of Kotliwas published by Toronto-based TSAR Publications in 2004, and that gave meconfidence in my creative voice.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

Rainsongs of Kotli, my first published work, began as a longpoem that evolved into a historical fiction. However, I retained a few originalpoetic sections and transformed them into prose.

My next book was based on the Komagata Maru saga, Chanting DeniedShores. In it, I included a handful of poems to vivify the narrative andserve as an itinerant poet's voice.

I ventured wholly into poetry for my third and fourth books, ExitWounds and Blood of Stone. By then, I had some confidence in mypoetic voice and was now less concerned about how these works would bereceived. I am glad I was able to make the transition to poetry and find myreaders.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I write almost daily, relying on my biphasic sleep patterns, and puttingwork together to submit is very often slow and laborious. While immersed inthis lonely process, I feel empowered and sustained by the writing's drive,passion, and truth. At no point do I consider the reader's response to mynarrative my sole concern, as this often gets in the way of the writing. If Ido my task well enough, the reader will find my writing accessible and thenwillingly take the journey with me.

I tend to overwrite, hence there are several drafts, from which I laterdistill the work to its bare essence before the final submission.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

Since my natural state as a poet is ekphrastic, I usually begin with ascene or an image. A piece of dialogue may inspire me to move onto the page andput down my personal take or view of the situation. The writing then dribblesin and is worked into a coherent whole (or incoherent whole, if I amdeliberately risking obscurity). For me, the volta is often as compelling asection of the poem as the point of the reader's entry into it, even more so.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy public readings immensely as the writer's voice introduces anuance that the written word does not always convey. I also find that there isa significant challenge in reading concrete poems where the visual aspect ofthe phrase is a vital part of the work. However, given the subjective nature ofmy writing and its narrow focus on unfamiliar themes, I am rarely offered opportunities to read my own work.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

I try to amplify a personal experience and viewpoint and attempt tovivify these for the reader.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

One of the roles of the writer in our culture is to engage with thesocial areas of concern/friction/intersection that are often outside thereaders' sphere and then to elucidate these emotional and intellectualexperiences in an engaging, enlightening, and entertaining manner.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

I have not yet had the fortune to work substantially with any editor formy fiction.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Be true to your art even if it does not find fertile soil to land on andflourish.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry toshort stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

My fiction is heavily laced with my poetics. My poetry is mostlyconcrete and narrative based.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My writing day begins at around 4am.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for(for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Look for inspiration in writing I admire, primarily Urdu poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz for his rhythms. Lately, I am returning for inspiration in the poetry ofValzhyna Mort, Andrea Cohen, Laura Ritland, Tolu Oloruntoba, et al.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Petrichor, in other words, Blood of Stone.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science,or visual art?

Nature, science, and visual arts are all inspirational for me. I amexcited to be working on a poetry chapbook on the wisdom of trees, anotherinspired by ravens.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

Robert Macfarlane (any of his multi-faceted writing), Pankaj Mishra's Fromthe Ruins of Empire, Loren Eiseley's The Unexpected Universe, E. L.Doctorow's Ragtime.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write a play or a screenplay, or collaborate on a creative project inthis field.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would itbe? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

I have held scores of jobs before turning to writing: Plant chemist,candy factory worker (mercifully only one day), a nightshift at the pillowfactory stuffing down feathers (four months), industrial lab chemist (17 years)

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I did not find any writings that related to my subjective livedexperience.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last greatfilm?

Colum McCann's awesome Apeirogon.

A favorite TV series: The latest incarnation of The Talented Mr.Ripley (titled simply as Ripley).

20 - What are you currently working on?

I am busy with a poetry book tentatively titled STALAG NOW thatexplores the global consolidation of influence and wealth in the hands ofever fewer individuals and organizations, often in collusion with the military,and the experiences of the precariat societies living under these conditions.

My next novel, Blood Towers, will present an ant's POV ofconstructing glass pyramids in the desert sands to fulfill the wet dreams oflatter-day pharaohs.

I am also working on a sophomore outing for my short story collection ofRainsongs of Kotli.

August 8, 2024

Patty Nash, Walden Pond

The wheel of history isbeing turned

Terns skim the wetlandswhich are evaded by the tiller

The tiller is the leverwhich turns the wheel

The wheel levers thetiller and is attached to the rudder

The rudder maneuvers theship like a shark fin

Fine establishment you’vegot here

Her? Oh, she’s my sister(“Lübeck”)

Thefull-length debut by Berlin, Germany-based American poet Patty Nash is

WaldenPond

(Colombia MO: Third Hand Books, 2024), holding as her title echoes ofreferences to both American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau’s infamous Walden;or, Life in the Woods (1854) as well as the celebrated pond itself, whichrests in Concord, Massachusetts. Can such a sleek and sharp poetry debutsurvive underneath such cultural weight? As the back cover offers: “In WaldenPond, Nash probes and plays with the first-person pronoun, investigatingthe construction of national identities and the way nations in turn constructthe identities of individuals.”

Thefull-length debut by Berlin, Germany-based American poet Patty Nash is

WaldenPond

(Colombia MO: Third Hand Books, 2024), holding as her title echoes ofreferences to both American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau’s infamous Walden;or, Life in the Woods (1854) as well as the celebrated pond itself, whichrests in Concord, Massachusetts. Can such a sleek and sharp poetry debutsurvive underneath such cultural weight? As the back cover offers: “In WaldenPond, Nash probes and plays with the first-person pronoun, investigatingthe construction of national identities and the way nations in turn constructthe identities of individuals.”Thereis an absolute sharpness to her poems, her restless, thoughtful meditations,her cutthroat lines, such as the short poem “Economy,” the first in the final (andtitle) section, as she writes: “I’d like to perfect my technique, / Which I knowis wanting // Though in order to do that, I’d need fresh / Hands on my sternumand my chest [.]” She writes a solidity of meaning and purpose that allows for afluidity of lyric, almost reminiscent of the work of the late Saskatchewan poet John Newlove. Her poems shape an American terrain, offering perspectives frommultiple points across a wide map, writing her “first-person pronoun” acrossfractures, fragments and sediment. “Don’t laugh,” she writes, in the poem “WorthHome,” “The order propped / Itself up in choir chairs / And didn’t wear underwear,and didn’t speak / And today we are meant / To be charmed by this and are dutiful.”

Setin four sections—“LÜBECK,” “PRECURSOR,” “THE PATRICIANS” and “WALDEN POND”—the poemsin Walden Pond offer collage in a really precise through-line, leapingfrom moment to small moment with fascinating coherence. She carves out delicatelines through deep cuts of restless imagery. “Ah, summer.” she writes, as partof the title poem, “Life / is what happens / when you / remember May / 2012 inpure / dread and fear. / Life is also what / happens when / you say ‘I simply /cannot deal’ and / defer, tuck / spaghetti / bolognese in / napkins, I’m truly/ excellent at that.”

August 7, 2024

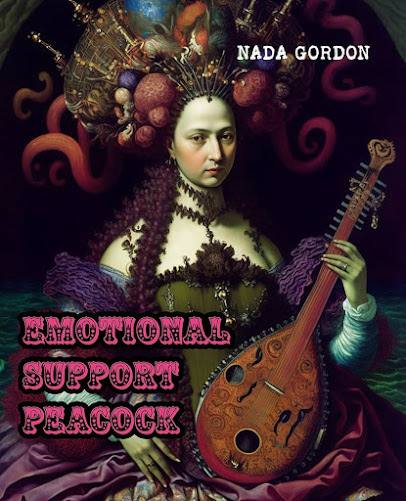

Nada Gordon, Emotional Support Peacock

Musings on Boys’ Arts

About our lords andmasters they were never wrong,

The second wavefeminists: how well they understand

Our degraded position:how it takes place

While someone else ismaking decisions or holding the reins of power or

Just galumphing dullyalong;

How, when the women arereverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculousequity, there always must be

Men who did not speciallywant it to happen, skating

On their awesome privilege:

They never forgot

That even the dreadfulpatriarchy must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, someuntidy spot

Where the boys go on withtheir boyish life and the emperor, with remorse

Scratches his ballsbehind a tree.

In Balthus’ “ThérèseDreaming” for instance: how she turns away

Quite leisurely from thegazer; her mother may

Have heard nothing, nokind of cry,

But for her it was not animportant failure; the dim light shone

As it had to on the whitelegs disappearing into the white

Panties, and theexpressive delicate girl that must have seen

Something amazing: anartist watching her with his eye

Had something to make andpainted calmly on.

Furtherto Oakland-born and Brooklyn-based American Flarf poet Nada Gordon’s recent

The Sound Princess: Selected Poems 1985-2015

(Subpress Collective, 2024) [see my review of such here] is

Emotional Support Peacock

(Buffalo NY: BlazeVOXBooks, 2024). Offering her usual flourish and flair of cover design, EmotionalSupport Peacock furthers Gordon’s exploration of the lyric through gesturalcollage, although one that deliberately seems to hold echoes of contemporaryAmerican politics and shades of certain poets from the New York School. “It’smy lunch hour,” she writes, to open the poem “SIX FEET AWAY FROM THEM,” “so I go/ into the kitchen among the Japanese / plates. First, into the refrigerator /to feed my vulnerable / plumpening torso some leftover curry / and kombucha,with my purple leggings / on.” If you don’t believe me, catch the last threelines of the same two-page poem: “A glass of water / and back to looking forwork. My heart is in my / throat, it is Lunch Poems by Frank O’Hara.”There is a curious way that Gordon engages in the “I did this, I did that” of apoet such as O’Hara, really weaving it in through already-familiar blends ofher lyric collage, as opposed to working any kind of replicant or falsetribute; this feels more akin to Brooklyn-based Gordon existing in the geographicspace of certain of these poets, certain of these poets, and allowing them spacein her particular yard.

Furtherto Oakland-born and Brooklyn-based American Flarf poet Nada Gordon’s recent

The Sound Princess: Selected Poems 1985-2015

(Subpress Collective, 2024) [see my review of such here] is

Emotional Support Peacock

(Buffalo NY: BlazeVOXBooks, 2024). Offering her usual flourish and flair of cover design, EmotionalSupport Peacock furthers Gordon’s exploration of the lyric through gesturalcollage, although one that deliberately seems to hold echoes of contemporaryAmerican politics and shades of certain poets from the New York School. “It’smy lunch hour,” she writes, to open the poem “SIX FEET AWAY FROM THEM,” “so I go/ into the kitchen among the Japanese / plates. First, into the refrigerator /to feed my vulnerable / plumpening torso some leftover curry / and kombucha,with my purple leggings / on.” If you don’t believe me, catch the last threelines of the same two-page poem: “A glass of water / and back to looking forwork. My heart is in my / throat, it is Lunch Poems by Frank O’Hara.”There is a curious way that Gordon engages in the “I did this, I did that” of apoet such as O’Hara, really weaving it in through already-familiar blends ofher lyric collage, as opposed to working any kind of replicant or falsetribute; this feels more akin to Brooklyn-based Gordon existing in the geographicspace of certain of these poets, certain of these poets, and allowing them spacein her particular yard.Emotional Support Peacock seems less constructed insections than in titled poem-clusters—“PROFESSIONAL POEMS,” “EMOTIONAL SUPPORTPEACOCK,” “THEY DO TORTURE MEANING,” “UNICORN BELIEVERS,” “MASCOT OF THEAPOCALYPSE,” “LITTLE BLUE THING” and “STURM”—and one might suggest this a bookof responses, including particular riffs on and around and from Mary Ruefle,Frank O’Hara, Wallace Stevens, offering snark and commentary, critique andhomolinguistic translation. She offers the poem title “Musings on Boys’ Arts,” andone might suspect a play on Musee de Beaux-Arts, to poems “composed” by heteronyms(in a Fernando Pessoa or Erín Moure/Elisa Sampedrín manner) “Merely Ruffles,” “Wall-assSemens” and “Very Tolerant.” And, as ever, with an attendant delight to the waysounds move and sway and gyrate, the lyric recombinant (offering echoes ofToronto poet Margaret Christakos’ own play in this particular direction) equivalentof gestural, explosive fireworks.

Eugenic Ether Poi

A flagellated fee rigorwoos the murky poi;

Bad deed tenements letout a nifty gut howl.

As addenda, Ed snuffles—ohswirly!—

And a cad, refereeing,oft tempts the ting-glum lox.

If a reevaluated goofingyins two hurts,

And this condescendinglypimping snowsuit is, um, wuss

Then a reappearedfluffier miniskirt mulls in its yolk, and,

ceding to fleetingnesses,houris play with vinyl polyps.

Like animalarialdiffident dingy piss,

a piffling baccarat ebbsopium onto you

with a fleetingness like—ow!—myrrhwool poop.

Highlightingthe tensions between how things were and how they have become, Gordon engageswith the terrain of contemporary America, including the Trump era, repurposing contemporarytwists and terrors and looking at earlier moments, Gordon writes masterful anddeliberate flailings, every word set in its own right place. “No ideas but in whitekittens.” she writes, as part of “Emotional Support Blep,” a poem subtitled “(outtakesand bloopers).” Further in the same piece, writing: “Trump won because poetryis so bad. / I’m so bored with this glittering wail.” Gordon writes of the mutatedAmerican culture and of female agency, dismissal; a collection less about playthan a darker and more absurd reordering of salvage, through which one mighteven survive. “She then flies to art,” she writes, as part of “Grandmother’sHands,” “and puts on a Periwig / valuing herself an unnatural bundle of hairs /all covered with Powder // My grandmother’s hands recognize grapes, / the dampshine of a goat’s new skin / all covered with sharp chips [.]” Or, as Jules Beckmanoffers in the “FOREWORD” to the collection:

Gordon’s is the MonsterTrucks of poetry. It rolls over everything. She feigns playful irreverence butreally she’s knitting you a new mind.

If you don’t likesurprises, keep your eyes off the page.

She’s making a point. You’regetting tattooed. Meaning: the singular is fractal. And you’re marked for life.

August 6, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Raisa Tolchinsky

Raisa Tolchinsky

is the author of the poetry collection

Glass Jaw

(Persea Books, 2024),winner of the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize (2023). She has published poemsin Boston Review, Kenyon Review, Michigan Quarterly Review,and elsewhere. Raisa earned her MFA from the University of Virginia and herB.A. from Bowdoin College. She was the 2022–2023 George BennettWriter-in-Residence at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, and iscurrently a student at Harvard Divinity School. Previously, Raisa lived inChicago, Bologna (Italy), and New York City, where she trained as a boxer.

Raisa Tolchinsky

is the author of the poetry collection

Glass Jaw

(Persea Books, 2024),winner of the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize (2023). She has published poemsin Boston Review, Kenyon Review, Michigan Quarterly Review,and elsewhere. Raisa earned her MFA from the University of Virginia and herB.A. from Bowdoin College. She was the 2022–2023 George BennettWriter-in-Residence at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, and iscurrently a student at Harvard Divinity School. Previously, Raisa lived inChicago, Bologna (Italy), and New York City, where she trained as a boxer. 1 - How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

My first book changed my life because itfulfilled the promise I made to myself at eight, and at sixteen, and again attwenty-six. The promise: not that I would write a great or even goodbook— just that I would finish one. There’s something sturdy about fulfilling apromise to past iterations of myself who walked through the poetry section andalways found the place where a book of mine might be shelved. I feel sturdieras a person, more capable of trusting my work in the world. I’ve realized more concretely that the peopleI love are rooting for me. I’m more able to accept I won’t be everyone’s cup oftea.

I don’t buy the myth that you have to publish abook to be a writer. But I will say I feel like a different kind ofwriter.

My current work risks more— I’ve learned a lotfrom my recent teacher Jorie Graham. These recent poems arrive gently, and arealso more terrifying to imagine out in the world.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, asopposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I found poetry in third grade. My teacher Pat isstill a dear friend and mentor. I loved the way a poem could hold so much in sofew words. All my intensity as a young kid had somewhere to go, somewhereplayful and loving. I’m sometimes creatively impatient and I like to toggle inbetween projects. I love fiction but I find it harder to dip in and out of. Ilike to think each genre has its season in my life, and I’m definitely in apoetry season.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

It’s taken me a few years to realize I’m a bingewriter. I’ll write 40 pages in four months and then not write for six. I’vebeen calling this “my living phase,” but the pause challenges me.

The real work of writing occurs for me inrevision— poems look entirely different when I finish them, and sometimes theinitial line that opened the poem is gone by the time it is “finished.” I writefor thirty minutes to an hour at a time— I always admire writers who can sit attheir desks all day, but I’m not one of them. I’m always getting up to getanother beverage. Sometimes it’s hard to quantify a “day’s work”— the processis still mysterious to me.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin foryou? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem usually begins with an image or a line,often while doing something other than writing (running, walking, cooking,etc). That line rarely makes it into the final poem, but serves as a compasstowards the poem beneath the poem. I tend to write widely until I’m clear whatI’m writing about, and then I search for the structure or story/myth the bookis telling. Once I’ve identified that, I know I’ll need to spend another chunkof time writing into the gaps.

5 - Are public readings part of or counterto your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I just completed a degree called Master ofReligion in Public Life at divinity school, so I am very interested in thepublic aspect of readings. There’s something so beautifully nourishing andgrounding about them— the simple act of showing up and saying here, I madethis. On this first tour, I love that I got to drive to every city whereI’ve lived and hug the people I love most. In that way, for those of us whohave patched together our livings from fellowships and programs, the book tourreally knit my life together. I learn so much from those who read Glass Jaw—and I also am aware that part of the process of being in a public space isembodying an archetype or image for others that is sometimes accurate,sometimes not.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concernsbehind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with yourwork? What do you even think the current questions are?

There’s that saying, and I’m not sure who saidit, that we ask the same question throughout our lifetime many different ways.I am always asking about how to live in my body. I am always asking what itmeans to love hard, in ways that are often painful. More of my recent work isinterested in where divinity enters or exits a life. I’m also interested inbending time. Writing is a way to be in conversation across many selves.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

For me, the writer is one who embodies moralimagination, sometimes beyond the current era— the one who courageouslylistens. Sometimes, the embodiment of Cassandra.

8 - Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’m so grateful to work with editors, teachers,friends who can point out my blindspots. All my work is a collaboration ofsorts, although sometimes with whom I’m collaborating is a mystery— everythingfrom ancestors to songs I listened to as a kid, turns of phrases that enteredmy mind and reappear in rhythm or pacing of a poem.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“I think we are well-advised tokeep on nodding terms with the people we used to be,whether we find them attractive company or not.” - Joan Didion

“If your Nerve, deny you— Go above yourNerve—” —Emily Dickinson

10 - What kind of writing routine do youtend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I tend to work well in the mornings. Coffee,some kind of movement practice, either before or after the page. I’ve learnedfrom my father, who is a playwright, to open the document every day, even if Imake no changes. It’s a way of keeping the poem alive. The things in my dailyroutine that tend to be consistent no matter the season are coffee and longwalks… especially now, as I’m trying to figure out the shape of my currentmanuscript, I find that I can’t really be at my desk “thinking”— I need to encounter,to play, to walk aimlessly. It’s a way of making a date with inspiration orchance. I love the story of David Lynch who showed up at Bob’s Big Boy everyday at 2:30 pm for ten years. Hereceived “only three perfect milkshakes out of more than 2,500.But that wasn’tthe point. For Lynch, it was enough to know he had set the stage for excellenceto occur,” believing that “whether with milkshakes or movies,”one “must make room forinspiration to strike — to lay the proper groundwork for greatness to takehold.”

11 - When your writing gets stalled, wheredo you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Silence. Trees.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Lake water, sun warmed wood, burnt coffee.

13 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whethernature, music, science or visual art?

Definitely music. Country ballads. I’ve beenlistening to Adrianne Lenker and Jess Williamson lately. Definitely artistic friendships across thecenturies. Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe, to name a few. Pilgrimages toplaces—New Mexico shows up a lot in my recent years because I’ve gone to Ghost Ranch (Georgia O’Keefe’s home) a few times.

14 - What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

My partner, fiction writer Derick Olson, who isbrilliant and kind and makes the best cappuccino I’ve ever had. On my deskright now are books by A.R. Ammons, Jorie Graham, Lexi Rudnitsky, Kiki Petrosino, Maggie Millner, Helene Cixous, and .

15 - What would you like to do that youhaven't yet done?

Lift more heavy weights. Write a novel. Go on awalking pilgrimage for my thirtieth birthday. Learn more bird calls. Get morecomfortable driving, since I learned in my late twenties.

16 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

It’s always been a writer’s life for me. Maybe adancer or a painter or a carpenter, but I have none of the attributes neededfor those jobs. Without poetry, I’d probably be a chaplain or a therapist.

17 - What made you write, as opposed todoing something else?

It’s FUN. And strange. And magical. It makes mefeel alive. Some days I’m frustrated, but most days I get to be surprised.

18 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

Great book: Couplets by Maggie Miller.Alternatively, The Highly Sensitive Person by Elaine Aron— I picked itup because I thought it said The Highly Sensitive Poet— ha!

Great Film: Not a film, but I’m watching Twin Peaks for the first time. My partner and I started it in May on a road tripwhen we stayed at a creepy ski lodge…

19 - What are you currently working on?

A book about the heart!

August 5, 2024

the green notebook :

For further excerpts of this current and ongoing work-in-progress, check out my enormously clever substack

. [note: I've been out of the boot for at least two weeks now,]

For further excerpts of this current and ongoing work-in-progress, check out my enormously clever substack

. [note: I've been out of the boot for at least two weeks now,]* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Father’sDay, I slip rushing up stairs and mangle the big toe on my right foot. Isuspect I may have broken it. I have broken my foot. I cancel a reading I wasto do in Picton this week, given it would have meant a solo three-plus hourdrive each way. I am very sore, and rather irritated: the frustrations ofcancelling a reading at all, let alone one so close to the date.

*

Semi-trappedat my desk, the site formerly known as Twitter provides me with an introductionto the work of Brazilian novelist and translator Victor Heringer (1988-2018)through the online journal grand: The Journal of One Grand Books. Ishould be working on final proofs for On Beauty, but I am caught uphere, instead. Heringer’s piece, “THE WALL AGAINST DEATH,” provides this asintroduction: “The late Victor Heringer authored the following crônica, aliterary hybrid form of personal essay and cultural criticism popular inBrazil, four years before his death in 2018. Here it is available in Englishfor the first time, translated by James Young.” There are echoes between thenameless form of this particular notebook and Heringer’s crônica, echoes ofRobert Creeley’s A Day Book (1972), all the ways through which writingand writers work through their thinking across a particular blend of critical,lyric hybrid. We are not so divided, after all, however unique.

Wikipediaoffers that “Crônica or crónica is a Portuguese-language form of short writingsabout daily topics, published in newspaper or magazine columns. Crônicas areusually written in an informal, observational and sometimes humorous tone, asin an intimate conversation between writer and reader. Writers of crônicas arecalled cronistas.” I very much like the idea of that, the “intimateconversation between writer and reader,” echoing back to Robert Kroetsch’smantra of all literature as part of a much larger polyphonic conversation. Andso, Heringer wrote against death, which the translation provides for him,posthumously. In that, as well. Isn’t that what we’re all doing? The push in myown writing and writing life, raised by a mother with a long-term illness thatcould, and even should, have taken her out multiple times across thoseforty-three difficult years. I need to do these things now, I thought, atseventeen, twenty-one, twenty-seven. I don’t know how much time I might have.

RonHoward’s new Jim Henson documentary, Idea Man (2024), references a youngJim devastated by the death of his beloved brother, and the suggestion of howthis pushed Jim’s future and ongoing creative endeavors. Is there ever enoughtime to do all the things? As Heringer, through Young’s translation, writes:

The clearly visible, upper case letters of“I defeated death” (which, ironically, were erased a few days later) stayedwith me. If at first I considered the gesture (all graffiti is a gesture, andDuchampian) a little inelegant, today I find it inelegant but a littlefascinating (above all because it was defeated, erased). Why such a stridentproclamation of a desire for transcendence?

Froman earlier draft of Christine’s Toxemia (2024): “Every body survivessomething. Or they don’t.”

August 4, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Myriam J.A. Chancy

Myriam J.A. Chancy, award-winning author of What Storm, What Thunder, is a Haitian-Canadian-American writer, the HBA Chair in theHumanities at Scripps College in Claremont, California and a Fellow of the JohnSimon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Whenyou publish a first book, it feels like you'll never write another, but thenyou do. Life doesn't so much change as it gets bigger in terms of reachingreaders and finding that what you had to say resonated with others. My firstpublished book (not the first written), was on Haitian women's literature andcreated a subfield. It made it possible for others to do their work andestablished me as a senior scholar fairly early in my career. So, that was agreat boost, but it took much more time to get my novels out. What I've learnedin the process of publishing my books (ten in all at this point) is that whatmatters is writing the next book, and each one will have varying degrees ofsuccess but each will find their intended audience in time. So, it's not somuch life changing as taking a step towards one's writing life, towards comingto terms with exposing one's inner self to a greater world through writing.

Mymost recent work, a novel, Village Weavers compares to the previous inthat it depicts Haitian characters as connected to a complex culture and alsoto global affairs. It differs in that it has fewer characters than my previouswork, which was narrated by ten characters, whereas Village Weavers hasonly two.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say,poetry or non-fiction?

Asa reader and professor of literature, I've always preferred the novel form forits complexity and breadth so I gravitate to fiction over other genres at thesame time as I write academic essays and nonfiction pieces alongside thefiction.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

Eachproject is different in terms of the time it may take. Some works have taken meseveral years while others have only taken months. I think the time a projecttakes depends on external factors, whether I'm teaching full time or not,whether I have to undertake a great deal of research or not and how tired I maybe at any given point. If the structure is particularly trying, that may alsotake me more time to work out. Village Weavers took me roughly a yearand a half to write, whereas the previous novel, What Storm, What Thunder,took six to eight years. Having said this, the process is more or less the sameeach time: I begin with an idea and start writing, then I determine if I wantto block out the book's structure or just want to write my way through. If Iwrite my way through, I write several drafts before arriving at the versionthat will go out to an editor. The initial drafts I consider the writer's draftand can look very different from the final product. I take notes while I'mwriting, usually on research and points of plot that I don't want to forget butI don't essentially write from notes; they're there to keep me on track as Iwrite and revise.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are youan author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or areyou working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I'malways working on a novel; it's the genre that interests me, the complexity ofthe relationships between the characters and the larger scope of their lives.It's what keeps me engaged. So, I'm definitely always working on the “book”rather than shorter pieces.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ido enjoy doing readings. As a kid, I participated in French declamationcontests and the objective was to bring someone else's piece alive for anaudience. Readings from one's own work is similar in that it brings the workalive for the reader but it also marks the definitive end of a project for meas its writer. Public readings are a letting-go process: it's not an act ofcreation but an act of release - to give up the finished project and to freemyself up to work on something new.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing?What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do youeven think the current questions are?

Well,since I'm also an academic, I'm always animated by theoretical concerns havingto do with the postcolonial condition, feminist issues, race, gender, and soon, and I think about the intersection of the theories developed in thesefields with the themes I'm trying to bring out in my fiction. By the sametoken, I don't think there are particular questions I want to answer in theworks generally. My creative projects also differ from my academic ones in thatthey address spiritual concerns that can't be addressed in the academic work.Each project brings with it its own sets of questions - or a particularquestion - that I then seek to work out through the arc of the novel and therelationships of the characters to one another. These questions from one projectto another while the overarching issues having to do with the postcolonial andidentity remain more or less stable: how does the history of colonizationcontinue to impact individuals within formerly colonized nations? How dofactors such as gender, race, clas and sexuality alter the scope of possibilityfor characters and color their perspectives?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

Tomy mind, the role of the writer is to illuminate, whether that is to examinevarious aspects of human nature or to shed light on forgotten histories orcommunities. Literature exists in order to provide us with tools for examiningourselves, our beliefs, societies and to better understand others. It shouldserve as a means to sympathize with others on the human condition. Empathymight be the end goal but that might be too much to hope for.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Editorshave been key to my publishing life whether early in my career or at present.Earlier on, editorial feedback helped me to work out my strengths andweaknesses, helped me to make decisions about what aspects of the craft werevaluable to me and which were not. At this point, editorial feedback has moreto do with assisting me in reaching my goals as I've set them out in a givenproject. A good editor provides the necessary external perspective, especiallywhen a project is complex or emotionally charged. In the revision process, anobjective editorial eye is essential.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Readpoetry. Raymond Carver (in a letter of response he sent me when I reached outasking for writing advice when I was a teenager).

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Notypical days. I write mostly when inspiration moves me to do so. When I'm deepinto a project, my usual routine is to get up very early in the morning towrite, usually between four and seven or seven to ten in the morning. I write.The cat joins me, then I go back to sleep or go teach. The earlier I can getsome writing in, the more I can get out of my day. Then I just keep going untilthe full first draft is completed. Sometimes I revise as I go until I feel thatI'm nearly done. It depends ont the project. I know the work is done when thecharacters no longer have anything to say and aren't waking me up to get towork! I also drink a lot of tea when I write and take daily walks.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Music.Always music. I usually have particular recordings I play related to each work.Sometimes I compile a playlist as I go, sometimes afterward. Music is atouchstone so if I get stalled or need to rethink some aspect of a project,music is always the way to go. And walks.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Thescent of laundry. This always reminds me of my mother.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

I'ma very visual person and worked with photography when I was younger. I like tothink of my novels as cinematic so thinking in terms of film sequences,lighting, mood, setting, all of that comes into my writing. Music too.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

I'minspired by the work of many contemporary writers and read widely. Historicallyspeaking, the works of James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Paule Marshall, Toni Cade Bambara, Margaret Laurence, Margaret Atwood, have been formative, among others.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Createan alternative small press or run a creperie/bookstore.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

IfI had a different constitution, I would have liked to have been a chef, or apainter. When I was in College, an aptitude test claimed that I would have beena good florist - that might still be something interesting to try.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Ireally don't know. I've been writing since I was seven and publishing since Iwas a teenager so it seems I was always meant to be a writer. But, in the end,I think I'm an artist and if I weren't writing, I would have found anotheroutlet for self expression.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

Thelast great book I read was Jacque Roumain's 1946 classic, Gouverneurs de laRosee (Masters of the Dew), in the original French.

Thelast great film - Jessica Lange in The Great Lillian Hall.

19- What are you currently working on?

Anovel focusing on the entwined themes of race, gender and travel, and someessays.

August 3, 2024

Tonya Lailey, Farm: Lot 23

The End of an Orchard

I want to land

on another reason

to yank out the farm’sfruit

trees, cut off theircoming

peaches, pears, cherries,plums,

replace them with vines

for wine.

My mother had it right.

Picking cherries didn’t addup.

Couldn’t pay for thebaskets

never mind thebabysitter.

And she didn’t like towork up

on ladders

up, in trees.

Maybe it was just themoney.

Even so, I want to makeroom

for anotherunderstanding.

My motherstood level with the vines,

tooktheir arms into her own,

set herfeet in step with their roots,

curled her fingers around their trunks

and bowed to them—

as if they were hertrellis.

“I’mprone to forgetting,” Calgary-based poet Tonya Lailey writes to close theopening poem, “Farms and Poems,” of her full-length debut,

Farm: Lot 23

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2024), “the purpose / of a farm / of apoem / has always been / the living in it.” According to her author biographyon the back of the collection, Lailey “spent her childhood on a farm inNiagara-on-the-Lake. She started a winery there in 2000 with her family andwinemaker Derek Barnet. Certified as a sommelier, she worked in the wine tradeuntil 2020.” The length and breadth of the poems within Farm: Lot 23explore and examine her relationship with that plot of family land, from thedays of her grandfather and a history of that particular corner of Ontario toher own experiences growing up and eventually working within those particularboundaries. “I think about the new reaches of peaches,” she writes, to close thepoem “Peaches,” “the cultivars we’ve bred and breed for travel. / Andthat year, after the war supports ended, // when my grandfather still farmedpeaches / and Wentworth Canners closed, unable to compete / with plantationagriculture to the south, // all around the township peaches ripened / thenrotted in piles.” She writes poems from the Niagara Peninsula—wine country, forthose unaware—managing the music and rhythms of daily activity on a workingfarm, offering these as both documentary and as a way to speak to the humanelements of familial life, such as the poem “The Give in Inches,” as she offers:“My parents sum / up the farm in twenty acres; the survey says /eighteen-point-five. They never do agree // on boundaries.” These are sharppoems, composed with enormous thought and care, composed as both portrait and alove letter to an eroding space. “On the other side / of the property line,”she writes, to open “Acre,” “the riverbank / the river, / chestnut, basswood, black walnut / American elm, black willow / bitternut hickory, blue beech, butternut / blue ash, sassafras—with itsleaf asymmetry. // Nothing / in a /row.”

“I’mprone to forgetting,” Calgary-based poet Tonya Lailey writes to close theopening poem, “Farms and Poems,” of her full-length debut,

Farm: Lot 23

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2024), “the purpose / of a farm / of apoem / has always been / the living in it.” According to her author biographyon the back of the collection, Lailey “spent her childhood on a farm inNiagara-on-the-Lake. She started a winery there in 2000 with her family andwinemaker Derek Barnet. Certified as a sommelier, she worked in the wine tradeuntil 2020.” The length and breadth of the poems within Farm: Lot 23explore and examine her relationship with that plot of family land, from thedays of her grandfather and a history of that particular corner of Ontario toher own experiences growing up and eventually working within those particularboundaries. “I think about the new reaches of peaches,” she writes, to close thepoem “Peaches,” “the cultivars we’ve bred and breed for travel. / Andthat year, after the war supports ended, // when my grandfather still farmedpeaches / and Wentworth Canners closed, unable to compete / with plantationagriculture to the south, // all around the township peaches ripened / thenrotted in piles.” She writes poems from the Niagara Peninsula—wine country, forthose unaware—managing the music and rhythms of daily activity on a workingfarm, offering these as both documentary and as a way to speak to the humanelements of familial life, such as the poem “The Give in Inches,” as she offers:“My parents sum / up the farm in twenty acres; the survey says /eighteen-point-five. They never do agree // on boundaries.” These are sharppoems, composed with enormous thought and care, composed as both portrait and alove letter to an eroding space. “On the other side / of the property line,”she writes, to open “Acre,” “the riverbank / the river, / chestnut, basswood, black walnut / American elm, black willow / bitternut hickory, blue beech, butternut / blue ash, sassafras—with itsleaf asymmetry. // Nothing / in a /row.”Acrossopening poem and four sections—“CONCESSIONS,” “LINES,” “END POSTS” and “FARMPHOTO”—Lailey offers such a soft and subtle music articulating a working farmfrom the inside, not merely as reminiscence but contemporary, working andlived-in space. There’s a thickness, a density, to her detail, one that embracesthe lyric but carves the lines so precisely to hold all that is required, butwithout sacrificing her music. She writes a precision to her lushness, onseasonal crops of cherries, peaches, pears and plums. “Away,” she writes, aspart of “Out to the Farm in July,” “from the stewed lap / of the shore /and the scents in banks / of raspberries / spicebushes / fringed bromes / hopsedges / bonesets / running strawberries [.]”

Theredoes seem an articulation of contemporary space, whether cities, suburbs orrural landscapes, that begins to feel a bit outdated without mention of thesesame landscapes framed through the lens of colonization. When modern prairiepoetry began to explode and take shape throughout the 1960s and 70s, long poemsoften referenced Indigenous people and Indigenous spaces, so to compose orarticulate a space without that acknowledgment now seems outdated, evenincomplete. It was a difficulty I remember having a few years back with Saskatchewanpoet Gerry Hill’s 14 Tractors (Edmonton AB: NeWest Press, 2009), forexample. For Lailey, the original occupants of her family land sit deep acrossthe foundation of her lyrics, from the prior names of roads, or streams, or throughher poem “Our Necks in the Woods,” writing:

After the RoyalProclamation of 1763, after the Treaty of Niagara, after the Treaty of FortNiagara, after the British acquired thousands of acres in exchange for 12,000blankets, 23,500 yards of cloth, jaw harps, thousands of silver ear bobs. Afterthe Mississaugas accepted “300 suits of clothing” in exchange for exactly whatis unclear but is recorded as the ownerhip of a “four-mile trip of land” alongthe Niagara River between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. After the colonizerscleared land to plant corn, wheat, other vegetables and to raise livestock,only a few of them returned the odd acre to trees.

Later farmers, like theones in my family, replaced unprofitable fruit trees with European grape vinesfor wine. Others erected greenhouses to supply the grocery market.

Ican’t think offhand of too many poets currently writing on farm-specifics, althoughI’ve recollections of certain pieces by Bren Simmers, Sandra Ridley and Karen Solie,including invocations of labour as an adult. The structure and approach ofthese poems compare to Solie’s, certainly, offering a perspective I can fullyappreciate and understand from my own experience, attempting to acknowledge theloss of a home and homestead, and an approach to daily living: the family farm.The collection closes with the long poem/section “FARM PHOTO,” that begins:

The farm road doesn’t end

or begin

where the photo halts

at the frame

at a stir fry vegetable

angle—the sort of slice

to render a carrot’sround

an oval

stylishly dismantle

a whole—

not that a farm is everywholly

land ever not only

a patch a plot

a pinch a section

an instant of earth oflife

as in one that has taken

place roughly

largely on one 20-acre lot

August 2, 2024

Jacob Wren, Authenticity Is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART

My performance work hasbeen a search for authenticity, but I don’t think authenticity is somethingthat exist. A work of art cannot be authentic, it can only feel authentic for certainpeople at certain times. Which is to say that, for me, authenticity is afeeling and about what we feel. In much the same way one might feel sad or feeljoy, one can feel something to be authentic. It is a word that suggestsengagement and connection. If you feel that Beyoncé is authentic and I don’t,this simply means that for you Beyoncé is authentic and for me less so. It doesn’tnecessarily mean anything about Beyoncé. However, what works of art we feel tobe authentic can also tell us a great deal about how we see things, what wevalue, and can at times also potentially change how we see and feel about theworld that surrounds us.

I’mbehind on everything, but finally working my way through writer and “maker ofeccentric performances” Jacob Wren’s

Authenticity Is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART

(Toronto ON: Book*hug Press, 2018), composed as a combination of criticism,first-person reportage and archive, surrounding the first two decades of hisparticipation in PME-ART, the collaborative interdisciplinary collective hehelped found in Montreal. Moving from storytelling, lingering doubt, alternate voicesand blistering self-critique, he writes of a growing disillusionment after adecade of working in Toronto, prompting him to head into Montreal, and startingthe beginnings of a sequence of connections, collaborations, conversations and conflictsthat opened up a wealth of writing, performance and possibility for both himand his work. “I have always been interested in what it means to stand in frontof a room full of people, often strangers, who are watching you, and to do sowith as little armouring as possible, not hiding the fact that the situation ispotentially unnerving or even nerve-racking, being as vulnerable as possiblewithout turning vulnerability into any kind of drama or crutch. I often saythat I personally find performing to be humiliating, and do my best, whileperforming, not to conceal this aspect of my experience. I often wonder why I havespent the past thirty years of my life obsessively working on this particular questionand practice. Perhaps it is only because it is a kind of impossibleundertaking, always leaving me artistically destabilized and therefore alwaysleaving me wanting more.”

I’mbehind on everything, but finally working my way through writer and “maker ofeccentric performances” Jacob Wren’s

Authenticity Is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART

(Toronto ON: Book*hug Press, 2018), composed as a combination of criticism,first-person reportage and archive, surrounding the first two decades of hisparticipation in PME-ART, the collaborative interdisciplinary collective hehelped found in Montreal. Moving from storytelling, lingering doubt, alternate voicesand blistering self-critique, he writes of a growing disillusionment after adecade of working in Toronto, prompting him to head into Montreal, and startingthe beginnings of a sequence of connections, collaborations, conversations and conflictsthat opened up a wealth of writing, performance and possibility for both himand his work. “I have always been interested in what it means to stand in frontof a room full of people, often strangers, who are watching you, and to do sowith as little armouring as possible, not hiding the fact that the situation ispotentially unnerving or even nerve-racking, being as vulnerable as possiblewithout turning vulnerability into any kind of drama or crutch. I often saythat I personally find performing to be humiliating, and do my best, whileperforming, not to conceal this aspect of my experience. I often wonder why I havespent the past thirty years of my life obsessively working on this particular questionand practice. Perhaps it is only because it is a kind of impossibleundertaking, always leaving me artistically destabilized and therefore alwaysleaving me wanting more.”Ifyou aren’t aware of Jacob Wren, he’s the author of a mound of award-winning novelsand plays, including Unrehearsed Beauty (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 1998),Families are Formed Through Copulation (Toronto ON: Pedlar Press, 2005),Revenge Fantasies of the Politically Dispossessed (Pedlar Press, 2010), PolyamorousLove Song (finalist for the Fence Modern Prize in Prose and a Globe andMail best book of 2014; Book*hug Press, 2014); Rich and Poor (finalistfor the Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction and a Globe and Mail bestbook of 2016; Book*hug Press, 2016) and the new novel, Dry Your Tears to Perfect Your Aim (Book*hug Press, 2024), out any minute now. There’ssomething really fascinating in how Wren composed this recollection, offeringhis take on certain situations, collaborations and performances, as well asallowing a number of his collaborators their own opportunities to offer theirown perspectives, after reading through an early draft of the manuscript. Workingfrom within the very idea of collaboration, Wren doesn’t wish his to be theonly perspective, certainly. If you don’t know where else to begin with thework of Jacob Wren, this might be the perfect point.

I have been makingperformances and literature for almost thirty years and, despite or perhapsbecause of my incessant doubts, I apparently have not quit. I constantly wonderwhat keeps me going. In one sense I feel that when you’re an artist the onlyway to keep going is to believe you have no choice. Believing one has no choiceis also a form of privilege.

August 1, 2024

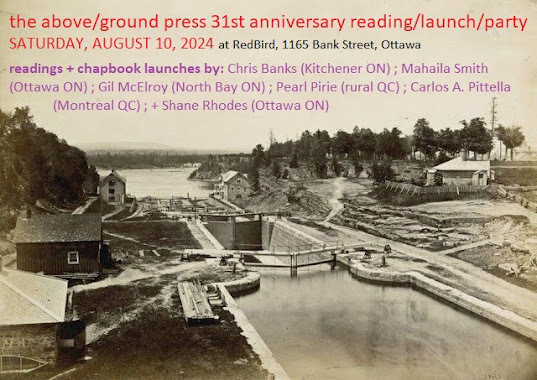

THE ABOVE/GROUND PRESS 31ST ANNIVERSARY READING/LAUNCH/PARTY!

SATURDAY, AUGUST 10, 2024 at RedBird, Bank Street, Ottawa

SATURDAY, AUGUST 10, 2024 at RedBird, Bank Street, Ottawalovingly hosted by editor/publisher rob mclennan

readings + chapbook launches by:

Chris Banks (Kitchener)

Mahaila Smith (Ottawa)

Gil McElroy (North Bay)

Pearl Pirie (QC)

Carlos A. Pittella (Montreal)

+ Shane Rhodes (Ottawa)

https://www.facebook.com/share/7XhrNyw6TzUUUQrU/

tickets available: https://www.showpass.com/the-aboveground-press-31st-anniversary-readinglaunchparty/