Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 48

July 10, 2024

Ongoing notes: the ottawa small press book fair (part three : Jenny Wong, Michael e. Casteels + Barbara Caruso,

[see the first part of these notes here; see the second part of these notes here]

[see the first part of these notes here; see the second part of these notes here]BC/ON: One of the most recent chapbook titles throughPinhole Poetry Chapbook Press is SHIFTINGS & other coordinates ofdisorder (2024), the chapbook debut by Jenny Wong, a poet who “resides inCanada near the Rocky Mountains.” There are some curious moments and silencesacross Wong’s lines—halts, and hesitations across first-person observational/meditationallyrics. “I come early / before sunscreen and sand / precipitate over miles ofskin,” she writes, to open the poem “At Kitsilano Beach,” “before portable nets/ catch spikes and volleys / of sunlit sound.” These poems hold such curious slownesses,and some intriguing lines amid striking images. “The lawns have begun todisintegrate / into brittle lessons about primary colors.” she writes, as partof “August Storms,” “Observe what happens to green / when there is nolonger blue. Feel the prick / of parched dry yellow.” Certain of thesepoems could have used a bit of an edit, but I am interested to see what Wongpublishes next; it does feel as though Wong is working to get at something thatshe hasn’t quite reached yet, but is certainly possible (and not that far off).As she writes to close the poem “Lactic Acid”:

Perhaps as we get older,our skeletons begin to show.

There is something insideme that eats away any desire for stillness. And so perhaps this is why I wander.Something in my bones.

Looking for home.

Michael e. Casteels + jwcurry, post-fair

Michael e. Casteels + jwcurry, post-fairKingston/Cobourg ON: I’m always pleased tosee a new title by Kingston writer Michael e. Casteels, and his latest is theprose collection A SUDDEN CHANGE OF SEASON (Proper Tales Press, 2024), acollection of thirteen pieces that sit in the realm of “postcard fiction.” I’vebeen intrigued for some time with Casteels’ ongoing work, watching each projectshift focus and framing between more narrative prose, prose poems and shorterpoem-structures to collaborative and even visual works. With each newpublication, I’m enjoying the fact that one doesn’t quite know what structures hemight be working with until one opens to the first page. Are these shortstories? Are these postcard fictions? Are these moments?

Monte and Me

My horse retrieved mymoccasins from the saddle bags. I took off my boots and slung them onto thesaddle horn. Then I donned the moccasins.

“What are you thinkin’?”he asked.

“Only one of us can makeit. I’ll pin them down, you open that gate.”

For a moment he stood inthe lemon light, inhaling deeply. Then he started down the hill, putting eachfoot down with equal care. Precious few moments were left.

Proper Tales Press (with Stuart Ross' works on the left + Anvil Press on the right,

Proper Tales Press (with Stuart Ross' works on the left + Anvil Press on the right,Ottawa/Paris ON: A while back, Cameron Anstee produced atitle by the late painter, publisher, collaborator and writer Barbara Caruso(1937-2009), her WORD HAPPENS POEM (Apt. 9 Press, 2023), a small titlethat opens with a “STATEMENT” by Caruso’s late husband (dated March 2018), thepoet Nelson Ball (1942-2019) [see my obituary for him here]. As he wrote:“Barbara occasionally employed letter forms, numbers and sometimes words in herearliest paintings and drawings. Her paintings became exclusively non-objectivearound 1970, while in her drawings she continued to incorporate the forms ofletters and numbers.” There is something lovely about Anstee working hissequence of archival projects, focusing his attention on the minutae of Caruso,as well as William Hawkins, whether through repeated issues, reissues or the collectedpoems that landed not long before Old Bill passed. There is such a delicateintelligence, out of complex, straightforward play in Caruso’s work, one thatdeserves a far larger attention (might a collected around pieces such as these,be worth considering?). Ball’s introduction continues, a bit further on:

Sometimes during such aperiod of respite she would make things, frequently working with small sizes.She was usually playful in what she produced. Word Happens Poem is anexample. She made it around 1970 as a private gift to me. It was drawn withgraphite pencil, employing stencils. Other examples of her “play” are the verysmall rubber hand-stamped presspresspress (1988-1998) booklets that shedistributed selectively to friends, and a series of miniature ink drawings madein the manner of her larger non-objective drawings.

It was not Barbara’sintention to publish Word Happens Poem. She grew up in the town ofKincardine during the 1950s, a conservative era in Ontario. Even today, she maynot have approved publication of several of the pieces. Nevertheless, theseries is here complete.

July 9, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Chuqiao Yang

Chuqiao Yang’s

poems have appeared in magazine suchs as The Walrus, Arc PoetryMagazine, Prism, Grain, CV2, Room, and on CBC Radio. She was a finalist for theBronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers and her chapbook,

Reunions in theYear of the Sheep

, won the bpNichol Chapbook Award.

The Last to the Party

isher first full-length collection.

Chuqiao Yang’s

poems have appeared in magazine suchs as The Walrus, Arc PoetryMagazine, Prism, Grain, CV2, Room, and on CBC Radio. She was a finalist for theBronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers and her chapbook,

Reunions in theYear of the Sheep

, won the bpNichol Chapbook Award.

The Last to the Party

isher first full-length collection.1 - How did your firstbook or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

Hi rob! Thank you for inviting me to do this. It means a lot.

My first chapbook, Reunions in the Year of the Sheep won thebpNichol Chapbook Award which was a huge honour. I have that chapbook, andbaseline press (Karen Schindler, I am talking about you!), and the RBC Writers'Trust to thank as all of that led to my first collection, The Last to theParty with Goose Lane Editions' icehouse poetry imprint.

I am answering your questions immediately after the book's release so Ireally don't know how things will have changed yet. So far, my friends andfamily and community have been really supportive, which is wonderful especiallysince this is my first full-length book. Things feel a bit different because Iwrote a lot of the book in my 'youth' and early 20s and left the poems alonewhile I was in school. Revisiting them and reworking them now in my 30s andadding new poems to the collection felt a bit like I was greeting and biddingfarewell to who I used to be when I wrote them the first time. Editing and peerreview was bot fun and odd because it felt like I was low-key saying 'get overyourself' to myself which was pretty, pretty humbling.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I'm not really sure. Forme personally, at least in the beginning, it felt like there was moreopportunity to say something through poetry than fiction, non-fiction oranother genre. But I like to dabble.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

As you hinted at in yourreview of my book (thank you again), it takes a very long time and it happensin spurts. I could be more disciplined. I notice that when I am reading a lot,I am more perceptive and open to writing.

4 - Where does a poem orwork of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

I piece things togetherover time. I learned a lot of new things about myself through the editingprocess working with Goose Lane and my editor. I'm excited to see how I'vegrown or changed or stayed the same, and I am excited to apply those lessons toother projects in the future.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

I like to go to readingsfrom time to time but I don't like reading. I know that it's a chance for me,reading it aloud, or someone hearing it, to experience or encounter newdimensions of the poem but I always worry I'm being gimmicky, pretentious, orboring. I will say though that it's very useful to hear your writing out loudwhen you are working on it, or to have someone read your work to you as youedit it.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one?What do you think the role of the writer should be?

People write for all sortsof reasons and those reasons can change with time. I really think it depends onthe writer, their literary and/or personal goals, and what they hope toaccomplish in their work.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Focus on the work.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?I let it pass without judgment. I used to beat myself up about it. But I don'tthink a period of time away from writing means anything negative; life ishappening all the time and it can feel more damaging if your mindset is thatyou have to keep your momentum up in order to be prolific, purposeful orinspired. I really think it's more than okay to have long periods of time whereyou are just absorbing the world, or living in it, or even struggling to makesense of it or yourself. You aren't wasting time. You are just chilling out andtaking it easy on yourself.

Of course it can be hard, but in those times, I try to do mindfulnesstechniques. I read and spend time with family and friends. I watch comedy, I seemovies, or I just do nothing. I bide my time to take care of myself. It's all awork in progress even if you're not working!

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Li-Young Lee, East of Edenby John Steinbeck, Simple Recipes by Madeline Thien, T.S. Eliot.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

More sports.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?I've been reading someteachings by the Stoics lately. I find reading their reflections validating andreassuring.

Also, last year I readthis book called Luster by Raven Leilani in literally one sitting, itwas amazing. I just finished Based on a True Story by Delphine du Vigan(wow!). Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky (also wow). Homie by DanezSmith (more wow). The Good Women of Safe Harbour by Bobbi French (WOWand so, so devastating).

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

Nothing has takenform yet, but maybe some stories.

July 8, 2024

from "the green notebook,"

Here’sa section of a work-in-progress I’ve been composing since April, a kind of “daybook,” if you will. Other fragments have been appearing over at my substack, also.

Here’sa section of a work-in-progress I’ve been composing since April, a kind of “daybook,” if you will. Other fragments have been appearing over at my substack, also. -- - - - - - - - - - - - -

Semi-trappedat my desk with boot upon broken foot, the site formerly known as Twitterprovides me with an introduction to the work of Brazilian novelist andtranslator Victor Heringer (1988-2018) through the online journal grand: The Journal of One Grand Books. I should be working on final proofs for On Beauty, but I am caught up here, instead. Heringer’s piece, “THE WALL AGAINST DEATH,” provides this as introduction: “The late Victor Heringerauthored the following crônica, a literary hybrid form of personal essay andcultural criticism popular in Brazil, four years before his death in 2018. Hereit is available in English for the first time, translated by James Young.” Thereare echoes between the nameless form of this particular notebook and Heringer’scrônica, echoes of Robert Creeley’s A Day Book (1972), all the waysthrough which writing and writers work through their thinking across aparticular blend of critical, lyric hybrid. We are not so divided, after all,however unique.

Wikipediaoffers that “Crônica or crónica is a Portuguese-language form of short writingsabout daily topics, published in newspaper or magazine columns. Crônicas areusually written in an informal, observational and sometimes humorous tone, asin an intimate conversation between writer and reader. Writers of crônicas arecalled cronistas.” I very much like the idea of that, the “intimateconversation between writer and reader,” echoing back to Robert Kroetsch’smantra of all literature as part of a much larger polyphonic conversation. And so,Heringer wrote against death, which the translation provides for him,posthumously. In that, as well. Isn’t that what we’re all doing? The push in myown writing and writing life, raised by a mother with a long-term illness that could,and even should, have taken her out multiple times across those forty-three difficultyears. I need to do these things now, I thought, at seventeen, twenty-one,twenty-seven. I don’t know how much time I might have.

RonHoward’s new Jim Henson documentary, Idea Man (2024), references a youngJim devastated by the death of his beloved brother, and the suggestion of how thispushed Jim’s future and ongoing creative endeavors. Is there ever enough timeto do all the things? As Heringer, through Young’s translation, writes:

The clearly visible,upper case letters of “I defeated death” (which, ironically, were erased a fewdays later) stayed with me. If at first I considered the gesture (all graffitiis a gesture, and Duchampian) a little inelegant, today I find it inelegant buta little fascinating (above all because it was defeated, erased). Why such astrident proclamation of a desire for transcendence?

Froman earlier draft of Christine’s Toxemia (2024): “Every body survivessomething. Or they don’t.”

July 7, 2024

Leah Souffrant, Entanglements

Nothing I explain isoutside this writing, and as I explain it transforms in the telling. But thereare countless pieces entangled, unknown, taking shape and changing the work.The travel that might take place. The arrivals of passengers full of excitement.And passengers slow with exhaustion, bored with business. The man next to measks his interlocutor, “Have you been to the Austin airport?” Which terminal doyou see me in? How terminal could any terminal be, how otherwise than yours? Ihave not been to Austin, I think silently. Where have we never been? Where arewe not going, shaping the ideas?

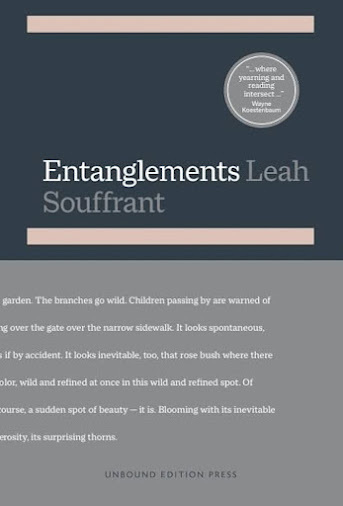

I’mabsolutely delighting in the prose of

Entanglements

(Atlanta GA: UnboundEditions Press, 2023) by New York-based Leah Souffrant, the author of

Plain Burned Things: A Poetics of the Unsayable

(Presses Universitaires de Liège,2017), who “makes art, poetry, essays and criticism.” There are ways throughwhich her prose offers comparisons to similar works by Jenny Boully, Sarah Lang, Danielle Vogel [see my review of her latest here] or Lori Anderson Moseman [see my review of her latest here]; a way through which thinking andreading and composition itself are presented across a rich and extended proselyric. Through Souffrant, the very subject is the shape of the writing as itoccurs. “I need poetic form to convey the ways we come to know and create theworld we inhabit and experience,” she writes, early on, “both as experience andthrough experience. These ways are necessarily multiple, plural. Hungry fromthe fragrances.” As the cover blurb offers: “Nothing less than a journey behindthe scenes of her own creative process, Leah Souffrant’s Entanglementsembraces the contingency, incompletion, difficulty, and uncertainty of artisticpractice.”

I’mabsolutely delighting in the prose of

Entanglements

(Atlanta GA: UnboundEditions Press, 2023) by New York-based Leah Souffrant, the author of

Plain Burned Things: A Poetics of the Unsayable

(Presses Universitaires de Liège,2017), who “makes art, poetry, essays and criticism.” There are ways throughwhich her prose offers comparisons to similar works by Jenny Boully, Sarah Lang, Danielle Vogel [see my review of her latest here] or Lori Anderson Moseman [see my review of her latest here]; a way through which thinking andreading and composition itself are presented across a rich and extended proselyric. Through Souffrant, the very subject is the shape of the writing as itoccurs. “I need poetic form to convey the ways we come to know and create theworld we inhabit and experience,” she writes, early on, “both as experience andthrough experience. These ways are necessarily multiple, plural. Hungry fromthe fragrances.” As the cover blurb offers: “Nothing less than a journey behindthe scenes of her own creative process, Leah Souffrant’s Entanglementsembraces the contingency, incompletion, difficulty, and uncertainty of artisticpractice.”Thecollection is woven, entangled, even through the description of sections—“Introduction:Entanglements: poetic epistemology,” “Thread: And keep me all this night,”“Thread: Attention to Loving,” “Thread: Riddle of Peace,” “Thread: The Book,”“Thread: Riddle of the Physical,” “On Entangling Threads” and “Thread: Weare always in ruins” to “Further Entanglements, Works Cited, End Notes.” Asthe collection opens, she offers the suggestion of being in a particular spaceand letting the notes fly in highly considered and formed prose, allowing that,even in flight, her thoughts are properly grounded. This is a remarkablecollection, one that rewards and even requires repeated readings through asimultaneous lyric density across ease. Further, as she offers:

Poetic knowing has longunderstood our limitations, the relativism of knowledge, the ways in whichattention to what happens – its repetition, its patterns, its disruptions – ishow we come to understand anything, perhaps everything. And this arrival comesthrough the senses: sound, body, living even as we think. Some poets aretrapped in history, poets seeking some humans and not others, loving only wheatmight have been before them as love-worthy. Language has oppressed, imprisoned,ruined. Loosening chains requires a heat, fine, burning. Yet even these poetsmight have seen nonetheless a world created in our perceptions. Even here, afragment of wisdom more capacious than law.

July 6, 2024

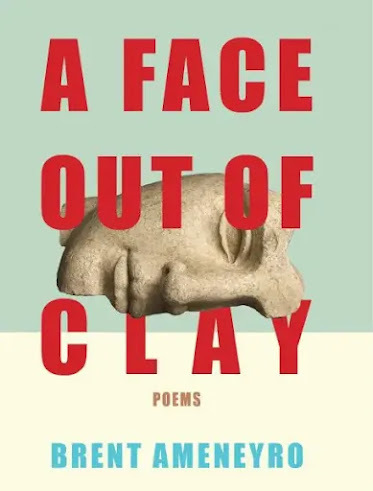

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Brent Ameneyro

Brent Ameneyro

is the author of the collection A Face Out of Clay (The Center for Literary Publishing, 2024) and the chapbook Puebla (Ghost City Press, 2023). His E-Lit has been selected for the 2022 Education and Electronic Literature Conference and Art Festival in Italy, as well as for film festivals in Denmark, Barcelona, Canada, and Los Angeles. He was the 2022-2023 Letras Latinas Poetry Coalition Fellow at the University of Notre Dame. He currently serves as the poetry editor at

The Los Angeles Review

.

Brent Ameneyro

is the author of the collection A Face Out of Clay (The Center for Literary Publishing, 2024) and the chapbook Puebla (Ghost City Press, 2023). His E-Lit has been selected for the 2022 Education and Electronic Literature Conference and Art Festival in Italy, as well as for film festivals in Denmark, Barcelona, Canada, and Los Angeles. He was the 2022-2023 Letras Latinas Poetry Coalition Fellow at the University of Notre Dame. He currently serves as the poetry editor at

The Los Angeles Review

.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Poems in my chapbook Puebla (Ghost City Press 2023) are featured in my debut full-length collection, A Face Out of Clay, which is being published as part of the Mountain/West Poetry Series with The Center for Literary Publishing in June 2024. As a little boy, I created books with crayons and colored paper, and announced myself as “Brent, Author.” A Face Out of Clay is my first book, and although it isn’t out yet, it has changed my life by fulfilling my childhood dreams. I’m sure this is true for many writers, and maybe it’s even a little cliché, but I feel as though I’m fulfilling a lifelong calling.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I’ve always had a hard time with names. When I read books like 1984 and Lord of the Flies as school assignments, I fell in love with language and literature, only to return to class the next day feeling like it wasn’t mine to have. It felt like literature wasn’t meant for me because I couldn’t remember the name of the character that first appeared halfway through the fourth chapter. I’d fail a test or get called on and not be able to answer the question in front of the class, so I started to ditch school and focus my energy on music.

Reading was a big part of my childhood; my mom would read to me every night before I started picking up books myself. So, when reading took a backseat to music in my teenage years, I fell in love with language through a new medium: song lyrics. Community college—which, admittedly, started as mostly tennis, bowling, and guitar classes—helped to reignite my passion for reading. When I transferred to CSUS in 2007, thinking about ways to improve my song lyrics, I began studying poetry. At the same time, I was listening to a lot of jazz and experimental music, and I was creating more music without lyrics. For most of the following decade, I made instrumental music and wrote poetry. I created a clear distinction between the two artforms and my studies of them. I eventually found myself in grad school in 2019 where I immersed myself almost exclusively in poetry for three years.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Some of my favorite poems that I’ve written appeared on the page complete in one sitting, with the exception of a few minor edits. I’m thinking of “To My Ancestors,” a Shakespearean sonnet first published in Alaska Quarterly Review, and “Sweet Little Things,” a pantoum which was a finalist in the 2022 Iowa Review Awards. Most of the time, this isn’t the case for me. I usually write as a kind of desperate utterance—compelled by the beauty of a moment or a surge of inexplicable emotion—then over months or years the poem marinades in my subconscious, waking me in the night when it demands a change in syntax or punctuation.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My work is a result of moving between different states of being. Therefore, any poetry written within a particular time period contains organic connections. Often referred to as “obsessions,” I visualize this phenomenon like a never ending hallway with doors on either side (channeling my inner William Blake, I suppose). Each door in this hallway leads to a micro-universe where a unique constellation of feelings, memories, and imagined realities crash into me. Publishing helps to provide a sense of closure. After A Face Out of Clay was selected for publication, I felt like I could finally close the door behind me and allow myself to fully enter a new one.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

The lifecycle of art while the artist is still alive almost demands community. The creative process as I’ve come to experience it is as follows: inspiration/compulsion; the initial creative act; allowing the art piece to breathe and make demands; publication; performance/community. I’ve been performing off and on—between music and poetry—for over 20 years now, and the periods of time where I didn’t perform felt like letters written that were never mailed.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

In A Face Out of Clay, I primarily explore movement. Images and ideas that deal with movement range from small, immediate gestures made in sculpting, to larger, more abstract brushstrokes as the speaker moves through time and memory. Under the umbrella of movement, other themes and questions emerge, but even explorations of identity and place, for example, are tied to movement: how one moves through different phases of life and knowing oneself; how families move from one country to another; the way groups of people move through collective experiences; and so on.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

With the internet and advancements in computer technology came the democratization of art. Art in the 21st century is undoubtedly shaped by the way information, tools, and resources have been placed into the hands of the masses. This translates differently depending on which artform is being discussed. For writing, the greatest differentiator is the ability to “post” or “publish” work immediately via the internet. The etymology of the word “publishing” comes from the Latin “publicare,” which means “to make public.” Prior to this shift, publishing was costly and restricted to a few lucky individuals. In short, there are more writers and artists creating and sharing art today, I believe, than ever before. This helps to create a more equitable publishing landscape (in theory), to erase the myth of the rare creative genius, and it also allows for writers to nurture smaller communities and connect more deeply with their audiences. And in these communities writers have the same responsibility they’ve always had: to handle language thoughtfully, with care.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I welcome collaboration and feedback. Every editor that I’ve worked with, whether for my book or for journals, has been kind, generous, and supportive.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

My dad always told me, “No eres monedita de oro para caerle bien a todos,” which can be interpreted in different ways, but he always followed with his English translation, “you are not a gold coin for everyone to love.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to musical composition)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’m a poet, sure, but I see that as a subcategory of being an artist. My definition of an artist is someone who is compelled to create; a conduit for a creative force that wills art into the physical world; a translator of the divine. From this perspective, when I move between poetry and other artforms, I’m simply choosing which vessel is most suitable for the flow of energy passing through me.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My day begins with coffee and reading. I don’t have a writing routine. Out of pure convenience, most of my writing begins as a note in my phone. I then move it over to my computer where the poem nests and makes itself comfortable. Editing is writing; I don’t distinguish between the two in my mind. I don’t think I’ve ever written more than one decent poem in a single day. Some days I open my manuscript and make huge shifts across multiple poems. Other days all I do is contemplate a single word.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don’t seek inspiration. I’m perfectly comfortable allowing myself to exist without writing when I don’t feel the page calling to me. I do spend as much time as possible listening to birds, looking at flowers, and walking my dog. Being in love is also an endless source of inspiration, so I must credit my wife, Alita. Sometimes just hearing her breathing is enough to spark my imagination.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Rosemary.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Can I say everything? Is that cheating? Music, for example, can directly influence my artistic cravings and vision on the page. I might desire a little splash of Charles Mingus’ controlled chaos, or the distilled, droning calm of a drawn out Miles Davis moment.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I read In Search of Duende by Federico García Lorca about 18 years ago. For the first time I felt that someone was able to describe feelings I had that I was not able to describe for myself. If I try to select my favorite excerpts, I might end up copying the entire text here, but I’ll share one quote that is powerful and affirming to me: “I have heard an old maestro of the guitar say, ‘the duende is not in the throat; the duende climbs up inside you, from the soles of your feet.’ meaning this: it is not a question of ability, but of true, living style, of blood, of the most ancient culture, of spontaneous creation.”

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’m not very interested in pursuing ideas or goals. I’m more interested in discovering ideas by allowing the art to flow through me, and creating space to cultivate surprise and wonder.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

There are those who write to get a certain job, to make money, to fuel their ego, or to get attention, among other things, and that’s none of my business. I write as a result of my need to create. I think of the myth of Sisyphus when I think of what it means to be a writer or artist of any kind. I push this poetry boulder up a hill, and when I get to the top, it rolls back down, and I start all over again. Through the act of pushing the boulder up the hill over and over, I’m compelled to contemplate the life assignment I’ve been given (I’m currently reading The Life Assignment by Ricardo Alberto Maldonado, and the title is fresh on my mind, so I’m borrowing it for this point I’m trying to make). To answer the question more directly, I don’t have memories of a time in my life where I wasn’t writing. I don’t think I “ended up” being a writer, I think it’s hard wired into me.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

July 5, 2024

Lindsey Webb, Plat

Before you died, Iconfused the personal with the ecological, die with dye. Now I hold my mouth tothe mouth of a tree and blow. Was I died here too, or did I born? I call therabbits whatever comes into my head, though a pearly vapor rolls beneath the real.Deep fur behind a name.

I dig, mulch, prune, andfertilize; I don’t dig, mulch, prune, and fertilize. I grow you; I die you. Inmy dream I visit a time before your death, when nature generated itself from aspool of tiny spirals. Little white berries. I’m told the garden is whereverthe righteous are, or vice versa; so at the felled catalpa I follow a vein ofpollen, adopt a mastic attitude. I eat something that looks delicious but hasno taste. Meanwhile, over my shoulder, a young woman sucks at the sap of atree, bending as if permanently cast that way, shrouded in the blue light ofarchetype.

July 4, 2024

ongoing notes: the ottawa small press book fair (part two : Jason Heroux + Moez Surani,

[see part one of these notes here] Might we see you at the ottawa small press fair this fall? The event will be turning thirtyyears old, don’t you know.

[see part one of these notes here] Might we see you at the ottawa small press fair this fall? The event will be turning thirtyyears old, don’t you know.Kingston ON: The latest by Kingston writer (and formerKingston Poet Laureate) Jason Heroux is the small Blizzard of None(2024), published through Michael e. Casteels’ Puddles of Sky Press. Heroux’slyrics emerge as short, narrative sketches, short lines carved as gestures intostone. “The old broken fence,” the two-line “Damage Report” reads, “loves itsbrokenness.” Unlike the brevity of a poet such as the pointillist mode of, say,Ottawa poet Cameron Anstee, Heroux works a short form across these eight small poems,but one that still retains a structure of narrative, working with clear delineationsof beginning, middle and end. “One definition of darkness is that it doesn’t exist/ by itself as a unique physical entity but is simply / the total or near totalabsence of light.” the poem “Black Lamp” begins. According to the authorbiography at the back of this small collection, also, he has a collection ofprose poems, Like a Trophy from the Sun, due out this fall with GuernicaEditions, which I am very much curious about, and looking forward to.

Blizzard of None

Blizzard of none

you remind me

of something I’ve neverseen.

Snowflake drifting fromone

nowhere to another,

where is your home?

Michael e. Casteels, Puddles of Sky Press

Michael e. Casteels, Puddles of Sky PressOttawa ON: I was fascinated by Moez Surani’s latest [see my review of his fourth full-length collection here], the chapbook The FirstThousand Questions (Ottawa ON: Apt. 9 Press, 2024), a title that opens withthis introductory note:

For about a year, I trackedthe questions that my daughter, Zara, asked. I tried to record them exactly as shesaid them—with her grammar, omissions, nicknames, and diction. In the editing, Iculled some of the redundant question, and I added referents or context insquare brackets.

I had the idea for thiswork when my daughter was born, and waited as her brain, senses and identitydeveloped. It was then that these inquiries began.

Setas an ongoing list of questions, there is something quite delightful in thenarrative of these pieces, offering a trajectory of development that beginswith Zara and circles out into the larger world. At the offset, Zara’s world isintimate, small (self, toys, parents) and moves with a wide-eyed andopen-hearted curiosity through the simplest of inquiries that become, throughthe process, increasingly aware and increasingly complex. As the parent ofthree (and a former child as well, if you can imagine), it is very familiar to watchas Zara, through her father’s hand, works from “Mama say goodnight? // Did youplay soccer ball? Did you win? // I peed in my bed and in my shirt. Why? //Where’s me? [Stuck in a sweater.] // Oh no, where’s my bath fruit?” into “Can Ido it [plunge the Bodum]? // Who left it [newspaper] on the ground [driveway]?// Do you have any grapes Why [not]? // Will there be penalty shots? Where’sJack Grealish? // How many fingers do you have? How many does Laiq have? // Arewe going to Montreal next week? Gosh. I love Montreal-y.”

July 3, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Amanda Merpaw

Amanda Merpaw

(she/her) is the author of

Most of Allthe Wanting

(2024) and

Put the Ghosts Down Between Us

(2021). Her poetry, playwriting, and nonfiction haveappeared in Arc Poetry Magazine, carteblanche, CV2, Grain, Prairie Fire, Plenitude, with Playwrights CanadaPress, and elsewhere. Amanda was a finalist for Arc Poetry Magazine’s2022 Poem of the Year Contest. She is currently a contributing editor at

ArcPoetry Magazine

and a member of the editorial board at Anstruther Press.

Amanda Merpaw

(she/her) is the author of

Most of Allthe Wanting

(2024) and

Put the Ghosts Down Between Us

(2021). Her poetry, playwriting, and nonfiction haveappeared in Arc Poetry Magazine, carteblanche, CV2, Grain, Prairie Fire, Plenitude, with Playwrights CanadaPress, and elsewhere. Amanda was a finalist for Arc Poetry Magazine’s2022 Poem of the Year Contest. She is currently a contributing editor at

ArcPoetry Magazine

and a member of the editorial board at Anstruther Press.

1 -How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Inthe years before I published my first chapbook, Put the Ghosts Down Between Us, I was feeling especially insecureabout my writing. Finishing the chapbook helped me realize that I was capableof doing the work that I wanted to do. I felt more grounded in my work, and Istarted to trust myself more. Working on my debut collection, Most of All the Wanting, was anamplification of that, a real internal validation of myself for myself,regardless of what happens next with its readership or reception.

2 -How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

As akid, I was drawn to fiction first. My earliest memory of writing is a series ofshort stories about a superhero who was pretty obviously just an extension ofme. As a teenager, I started to read more poetry, and that’s when I startedwriting poems pretty obsessively. Poems were more aligned with how I processedthe world and language—I felt more myself in the writing of poems and in thealchemy of reading them. I’ve only recently returned to writing fiction, aftera long time believing that it wasn’t “for me” anymore (whatever that means!),and it’s been fun to play in that world again. I also write nonfiction andplays, but I don’t have the executive functioning (or the time!) to be workingin all of these forms at once, so these are not currently as central to mypractice. I’m sure I’ll reconnect with them when they’re the right form for astory or question I want to explore.

3 -How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

I’m a slow writer. Sometimes a first draft will arrive quickly and then sit inmy notebook for weeks or months or longer. My mind moves slowly through thosedrafts, and while a poem’s final shape is sometimes similar to its first draft,I only arrive at knowing that something is done by spending a long timeconsidering the words, the lines, the turns, the breath, the form. I type up mydraft, play around with those things, and often have many variations of a poemliving in one document. Often many notes, too—my own questions and potentialedits, research about relevant topics, thoughts on including arts and culturereferences, etc. Larger writing projects sometimes feel clear to me early on,especially if I have particular themes or preoccupations in mind—that’s how itfelt with Most of All the Wanting. Andsometimes the larger projects aren’t apparent to me until I’ve done morewriting and can consider how all the writing might exist in relation.Regardless of what I’m working on, part of my slowness also comes from managingsome chronic health issues and the impact of my anxiety on my writing/thinkingprocess. Producing work quickly and frequently isn’t possible for me, and Idon’t aspire for it to be.

4 -Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces thatend up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Mypoems begin all over the place: a line that I can’t stop turning over, an image(real or imagined) that persists, overheard dialogue, a moment of connectionwith art, a question I can’t easily answer. With Most of All the Wanting, I was working on a book from thebeginning, and I knew that I wanted to explore my relationship to a specificset of experiences: my divorce, dating in Toronto as a bisexual woman, findingmy way to a relationship again. I knew I wanted the book to go there becausethe work I did in my chapbook helped me to figure that out. I’m working onpoems for my second collection now, and I don’t have a sense of any central“aboutness” or connectedness quite yet, if it ever arrives. I have some ongoingpreoccupations and questions, and I’m just writing towards those in eachindividual poem until I see how they come together.

5 -Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ireally enjoy reading my work aloud. I read it aloud to myself constantly whilewriting—it’s a central part of my process in achieving rhythm, musicality, andfinding the right words. So it’s a joy when I finally get to read them toothers, when I get to consider how poems might come together to build a sort ofset list and an experience for the audience. I desperately do not want readingsto be boring, so I think a lot about anecdotes to share alongside the poems—theevents within them, my relationship to them. I think about how I can make theaudience laugh. Making the audience laugh between poems or during apoem—reminding them poetry doesn’t have to take itself so seriously all thetime—is sometimes the best part.

6 -Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Inthis collection, I’m working through questions about intimacy and how we existin relation to one another and ourselves. How do we make and remake ourselvesin our relationships (and in their endings)? How do our relationships impactour experiences of time? What is relational grief? How do I experience myqueerness in private and in public space, with and without others? How does myqueerness shape my desires, how do my desires shape my queerness? I’m alsointerested in questions of the conversational and of dialogue, how voice andform and content meet, and how they can make space for, represent, or makestrange how we speak to one another and how we speak to ourselves.

Assomeone with lived experiences of disability and madness, I’m always thinkingabout how I can use language and form to communicate that, too—what it is liketo have a disabled body, a doubting and anxious mind. These concerns are morepresent in the poems I’m working on now, towards a second collection.

7 –What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do theyeven have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Lately,I've been thinking a lot about James Baldwin, who said “a writer is bydefinition a disturber of the peace…he has to make you ask yourself, make yourealize that you are always asking yourself, questions that you don’t know howto face.” Be they questions about ourselves, our close intimate relationships,our relationship to the world and the systems that we maintain or that we workto dismantle—the questions and their disruptions are central to myunderstanding of what writers do. I do not see writing as apolitical, even whenI’m writing a poem about love. Even when I’m focused on aesthetics. Isn’t lovepolitical? And its absence? What about aesthetics? Audre Lorde told us thatpoetry is not a luxury, it is “a vital necessity of our existence”—a place forour feelings, our dreams, our hopes to survive and to change, “first made intolanguage, then into idea, then into more tangible thought.” Naming somethinghelps us imagine the possibilities of that thing in the world.

Ibelieve, too, that writers are historians—our work creates a robust archive ofour questions, emotions, experiences, and of the emotional, cultural,relational, political, linguistic, etc., experiences of our times.

8 -Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

I’vehad the opportunity to work with Jim Johnstone on both my chapbook andfull-length collection, and it’s been essential. I can get caught in a lot ofdoubt—these spirals of overthinking in the editing phase. I get stuck for areally long time on a question of a single line break or word choice. That’swhen I know I’m too far into a conversation with myself about my work and am inneed of an outside perspective. Jim is a perceptive and thoughtful editor, andgenerous with his energy and time. I always appreciate his suggestions. Evenwhen we’re making difficult choices—cutting entire poems from the collection,changing language I’ve become attached to—I know it’s bettering the work, theproject, for us to consider these choices, and for me to figure out myrelationship to them. Jim gets my intentions, my voice, my aspirations for theprojects, which builds a lot of trust. And the process also helps me be lessprecious about holding on to anything too tight, becoming too deeply embeddedin my own stuff.

9 -What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Oneof the best pieces of advice about writing I’ve heard recently is from Kirby,in a fantastic workshop they ran earlier this year based on their book, Poetry Is Queer. I mean, the wholecollection feels like you’re being wrapped up in good advice about living andwriting and finding joy as a queer person. Something I’ve carried from thatworkshop is Kirby’s reminder to arrive at the page considering the poem wedon’t know how to write yet. To practice the non-habitual. What kind of writingdoes that lead to?

10 -How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to theatreproductions)? What do you see as the appeal?

Ilove moving between poetry and theatre—they ask different things of me, and Iappreciate that. I like that theatre begins from a place of imagining theliveness of the experience, the energy exchange between performers andaudience. You’re creating something that feels both intimate and shared,public. Something that requires extensive collaboration with many artists andtechnicians performing, directing, costuming, lighting, designing, etc. Youhave tools beyond language at your disposal! So many perspectives beyond yourown! Sometimes that feels like a relief. When producing theatre, I like thatthe project management/event coordination aspects are organized andconcrete—it’s so satisfying. And I really love that poetry isn’t satisfying inthat way. It’s more nebulous and quiet and interior. I like imagining asingular reader having a private experience with the work. I like the relief ofsitting with a single stanza or poem for as long as I want, and that nobody(hopefully) is counting on me to finish it so they can also do their jobs. I’mgrateful to be alone when I’m working, and that the tool at my disposal islanguage (or the absence of language, the space of silence)—that’s probablywhere I feel most at home as an artist.

11 -What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? Howdoes a typical day (for you) begin?

Itreally depends on my health and associated energy and focus levels. I gothrough periods where I’m able to wake up and write for an hour or two beforemoving on to my full-time job, and other periods where that’s impossible.During the latter periods, I focus on jotting down ideas when I can, reading asmuch as I can, and editing existing material rather than generating new drafts.I’ve been lucky to take part in really wonderful online writing workshops overthe last few years, and I try to participate in those regularly so that I haveongoing writing dates with myself where I’m engaged with craft and activelydrafting. I sometimes go long periods without touching my notebook or laptop,periods when the work is the living and observing and thinking and feeling. Therest and the taking care. I try to give myself grace. Regardless of myrelationship to writing at any given time, I always start my day by walking mydog and then eating some breakfast.

12 -When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

IfI’m feeling stalled with my writing, it means I need to take a break to doliterally anything else. I go for a walk or put on a record or watch some goodor very, very bad TV. Reading helps a lot—sometimes something new, or returningto an old favourite. Like, oh yeah,that’s how Sharon Olds opens a poem. Good to know. If I still can’t getunstuck, I skip over what’s not working and just keep writing beyond it, orinto another piece entirely, and I make a note to come back later.

13 -What was your last Hallowe'en costume?

WednesdayAddams. I was a middle school teacher for a long time, so I have Halloweenedfar too close to the sun. Wednesday is a great sustainable/repeat costumebecause it’s just a cute dress with some Mary Janes that otherwise live in mycloset anyway. Add some braids and you’re giving macabre girl energy.

14 -David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any otherforms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Thiscollection is definitely attuned to and in conversation with nature—weatherpatterns, the climate crisis, landscapes, non-human animals, etc., they’re allthere throughout, they’re on my mind all the time. As someone who grew up in amusical home, music has a deep impact on my sense of rhythm, movement, wordchoice, sound, etc., in a poem. There are musical references throughout thecollection. Film, TV, and theatre influence my work too, the content and thelanguage of it, especially where narrative or dialogue or the epistolary comesin. I’m also currently working on a series of ekphrastic poems for my secondcollection in response to visual art by and about women, specificallyportraiture.

15 -What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

Inaddition to the writers I named in previous answers, I’ll add: Hanif Abdurraqib, Nicole Brossard, Sophie Calle, Emily Dickinson, Mark Fisher, Louise Glück, Donna Haraway, bell hooks, June Jordan, Ada Limón, Gwendolyn MacEwen,Lee Maracle, Wajdi Mouawad, Frank O’Hara, Sharon Olds, Erin Shields, Mark Strand, Virginia Woolf, Kate Zambreno.

16 -What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I’dlike to write for TV. Something funny, like BaronessVon Sketch. I’d like to travel the country by train in all directions—akind of writing residency, maybe.

17 -If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

I spent nearly a decade working as a classroom teacher, and I still work ineducation now, outside of a school setting. I could see myself being atherapist too. Maybe that’s cliché and all the millennial queers see themselvesas potentially good therapists.

18 -What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Ever since I had the realization as a kid that people wrote the books I wasreading and maybe I could be a person who writes books too, I’ve been writing.I’m sure it had something to do with being a sensitive, anxious, highlycommunicative kid who was always taking shelter in books or talking to myselfor writing in diaries, etc. I just can’t imagine not doing it.

19 -What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Earlierthis year, I devoured Olga Ravn’s My Work(trans. Jennifer Russell and Sophia Hersi Smith). I recently watched andloved The Holdovers. These days Iwatch more TV, though—I just binged KillingEve, which finally became available to stream. Sandra Oh and Jodie Comer? Adream!

20 -What are you currently working on?

I’mworking on poems towards a second collection. And I’m slowly working on myfirst novel.

July 2, 2024

Brent Ameneyro, A Face Out of Clay: Poems

ODYSSEUS AS A MEXICAN BOY

the Cyclops sometimesappears as an angry school principal

who yells at the boy inSpanish

until a large vein splitshis forehead

into two hemispheres

and his dark brown skin

becomes the earth

the boy sails away untilhe finds a new land

with bright green grass

which is actuallyartificial turf for a soccer field

he comes across Poseidon

who is a goalie

that punches the ballwith a closed fist

Penelope is a blondesecond grader back in California

Calypso is a Mexican girlwho teaches a boy to dance

Iwas curious to see the full-length debut by Los Angeles poet and editor Brent Ameneyro, following the chapbook Puebla (Ghost City Press, 2023),

A Face Out of Clay: Poems

(Fort Collins CO: The Center for LiteraryPublishing, 2024). A Face Out of Clay is a collection of first-personlyrics that explores context as well as form, attempting to define the self,especially between the seeming-poles of two distinct cultural considerations,between Mexican and American, overlaying other literary considerations acrosshis own narratives, from Greek Odysseus to Ulysses. As he writes to openthe poem “ULYSSES IN PUEBLA”: “He cleans his lips with two wipes / of his JorgeCampos jersey. / Damn that new kid in school. / Damn him. Hope he trips / andcan’t play for a few weeks.” Across these poems, Ameneyro is first and foremosta storyteller, examining the American experience through the lens of his ownMexican background, providing echoes similar to that of Mexican American poet,editor and teacher Jose Hernandez Diaz’s recent full-length debut, BadMexican, Bad American (Cincinnati OH: Acre Books, 2024) [see my review of such here]. Ameneyro might utilize that initial and simultaneous dualconnection and disconnect as a kind of foundation for the collection as whole, hequickly furthers his reach by offering perspectives and insights into examples fromthe larger, surrounding population, each of whom are looking for some human wayto connect. “Nobody stopped to ask / if you are lonely // on the long drivehome. / You are so calm,” he writes, to open the poem “TO THE GUY WHO DRESSED AMANNEQUIN AND PROPPED IT UP IN / THE PASSENGER SEAT TO USE THE CARPOOL LANE,” “sostill // as you look beyond everyone, / past the illusion of daylight; it’shard to tell // where the black of your eye ends / and the infinite black ofthe universe // begins. Who sat there before?” In a very fine collection, debutor otherwise, Ameneyro displays himself as a narrative collage-artist,attending elements from all directions while holding still to that relativelystraightforward through-line, which allows any lyric and drift to remainpurposeful, propulsive. “Hidden above the ash / in the sky,” he writes, as partof “ULYSSES IN PUEBLA,” “a red-legged honeycreeper wanders / the empty space.”

Iwas curious to see the full-length debut by Los Angeles poet and editor Brent Ameneyro, following the chapbook Puebla (Ghost City Press, 2023),

A Face Out of Clay: Poems

(Fort Collins CO: The Center for LiteraryPublishing, 2024). A Face Out of Clay is a collection of first-personlyrics that explores context as well as form, attempting to define the self,especially between the seeming-poles of two distinct cultural considerations,between Mexican and American, overlaying other literary considerations acrosshis own narratives, from Greek Odysseus to Ulysses. As he writes to openthe poem “ULYSSES IN PUEBLA”: “He cleans his lips with two wipes / of his JorgeCampos jersey. / Damn that new kid in school. / Damn him. Hope he trips / andcan’t play for a few weeks.” Across these poems, Ameneyro is first and foremosta storyteller, examining the American experience through the lens of his ownMexican background, providing echoes similar to that of Mexican American poet,editor and teacher Jose Hernandez Diaz’s recent full-length debut, BadMexican, Bad American (Cincinnati OH: Acre Books, 2024) [see my review of such here]. Ameneyro might utilize that initial and simultaneous dualconnection and disconnect as a kind of foundation for the collection as whole, hequickly furthers his reach by offering perspectives and insights into examples fromthe larger, surrounding population, each of whom are looking for some human wayto connect. “Nobody stopped to ask / if you are lonely // on the long drivehome. / You are so calm,” he writes, to open the poem “TO THE GUY WHO DRESSED AMANNEQUIN AND PROPPED IT UP IN / THE PASSENGER SEAT TO USE THE CARPOOL LANE,” “sostill // as you look beyond everyone, / past the illusion of daylight; it’shard to tell // where the black of your eye ends / and the infinite black ofthe universe // begins. Who sat there before?” In a very fine collection, debutor otherwise, Ameneyro displays himself as a narrative collage-artist,attending elements from all directions while holding still to that relativelystraightforward through-line, which allows any lyric and drift to remainpurposeful, propulsive. “Hidden above the ash / in the sky,” he writes, as partof “ULYSSES IN PUEBLA,” “a red-legged honeycreeper wanders / the empty space.”

July 1, 2024

happy canada day!

Not sure what today is doing yet, although we might be slow moving. Christine has been laid flat with a cold all week, & I've my broken foot, falling up stairs on Father's Day. Here is, at least, a short story I wrote a while ago set on Canada Day, at the Dominion Tavern in Ottawa's Byward Market (posted as one of those occasional short stories upon my substack, in-between other projects I'm attempting to further), which falls into my short story collection,

On Beauty

(University of Alberta Press, 2024). You've already pre-ordered a copy, yes? And how many short stories, do you think, are set at the Dominion Tavern? Oh, those were the days.

Not sure what today is doing yet, although we might be slow moving. Christine has been laid flat with a cold all week, & I've my broken foot, falling up stairs on Father's Day. Here is, at least, a short story I wrote a while ago set on Canada Day, at the Dominion Tavern in Ottawa's Byward Market (posted as one of those occasional short stories upon my substack, in-between other projects I'm attempting to further), which falls into my short story collection,

On Beauty

(University of Alberta Press, 2024). You've already pre-ordered a copy, yes? And how many short stories, do you think, are set at the Dominion Tavern? Oh, those were the days. Both of our young ladies, obviously, have finished their school years. This past Thursday, Aoife completed grade two; the Thursday prior, Rose completed grade five. Let the summer of day-camps, potential travel and other randomness begin. Oh, and I'm reading in Toronto again at the end of the month?

Both of our young ladies, obviously, have finished their school years. This past Thursday, Aoife completed grade two; the Thursday prior, Rose completed grade five. Let the summer of day-camps, potential travel and other randomness begin. Oh, and I'm reading in Toronto again at the end of the month?