Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 41

September 18, 2024

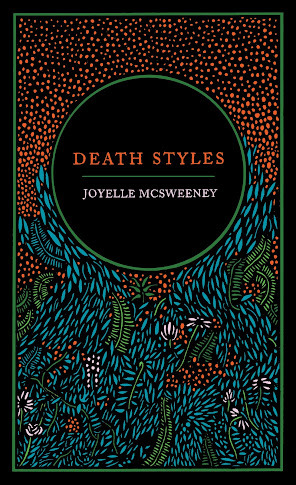

Joyelle McSweeney, Death Styles

My review of South Bend, Indiana poet Joyelle McSweeney’s Death Styles (New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2024)

is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

. See my 2009 "12 or 20 questions" interview with her here.

My review of South Bend, Indiana poet Joyelle McSweeney’s Death Styles (New York NY: Nightboat Books, 2024)

is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics

. See my 2009 "12 or 20 questions" interview with her here.September 17, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Michelle Winters

Michelle Winters is a writer,painter, and translator born and raised in Saint John, NB. Her debut novel, IAm a Truck, was shortlisted for the 2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize. She isthe translator of Kiss the Undertow and Daniil and Vanya byMarie-Hélène Larochelle. She lives in Toronto.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How doesyour most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Publishing my first book made me a writer; getting itshortlisted for the Giller made me a suddenly popular writer, an experience atonce glorious, terrifying, wonderful, and fraught with self-doubt. Hair for Menis a more assured book than I Am a Truck; the concepts are stronger andbetter argued, the writing is more fluid... I used to worry about I Am aTruck out there in the world with its wobbly little legs; Hair for Mencan handle anything.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to,say, poetry?

I’ve always been a sucker for character and narrative.I love a story that develops as a result of the way a person is. It’s anotherworldly kind of fun.

3 - How long does it take to start any particularwriting project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slowprocess? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or doesyour work come out of copious notes?

I won’t spend too much time planning, because I find theidea only develops while I’m actively writing. This means that I discover thestory as I go, and it changes a lot, but it gets written!

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually beginfor you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I keep a lot of observations, episodes, characterstudies, etc. tucked away in a Notes folder. There are Big Notes for novels andSmall Notes for short stories. I usually know whether a note is Big or Small,but it tends to be a particularly compelling character that pushes a note intothe Big folder and sets a novel in motion. I watched a man on a flight theother day close all the overhead compartments before takeoff, not in order tohelp the flight attendants, but because he seemed to think he’d do a betterjob. Then he stood in the aisle and talked about himself to anyone who wouldlisten for the whole five-hour flight. That guy was a Big Note.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to yourcreative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. I only consider my own workcomplete once I’ve read it out loud - very important for flow and pacing. Istudied theatre, so delivery is important. Hair for Men is written insuch a way that you should be able to read it out loud, in character, asLouise.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I like to think I’m turning over a number of rocks, takinga look at what’s underneath, and seeing how it responds to the light of day. I’mmore an asker than an answerer, and the question I’m always asking is “Why this??”

7 – What do you see the current role of the writerbeing in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role ofthe writer should be?

The writer is there to reveal humanity to itself.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

I find it essential. My structure is absolutely everywhere.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Write for the top 5% of your audience.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move betweengenres? What do you see as the appeal?

I write, translate fiction, and paint. Translation iswonderful practice for my own writing; it’s expression without the strain ofcreation and is deeply satisfying. Painting clears the whole slate, returning meto my factory settings - but I can ruminate on a story/character idea while I’mpainting, which is a refreshing way to get there. All the arty activities feedone another in a nice symbiosis.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep,or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I still work a regular job, so when I’m not doing that,I’m cramming the rest of my moments with creative things. I do get a few full,glorious days a week where I can just write. Those days start with coffee (obviously)and proceed with as little interruption as possible. After dinner, I’ll jam in anothercouple of hours. Then a sensible hour of prestige television. Time is so precious.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turnor return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Walking helps, and a good, long stretch, but alsopicking up any book from the shelf and reading a few pages reminds me that anythingcan be written. My idea is as good as any other. Sometimes, I listen to TheStreets, A Grand Don’t Come for Free. It’s like an electronica hip/hopoperetta about the mundane events surrounding a guy misplacing a thousand quid.Again, it reminds you that you can write anything.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The smell of the Bay of Fundy at the Market Squaredocks in Saint John. The scent of a shipping port will always bring me home.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

Oh man, music, film, visual art – but I also lovesitting quietly, watching my fellow humans. The things we do…

15 - What other writers or writings are important foryour work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Martin Amis – for better or worse - has influenced meheavily my whole reading/writing life. I’m aware of his difficulties, but noone was more generous with humour – plotting it out bit by bit, laying hislittle trap, until he delivers the punchline, and you realize just how muchwork he was doing all that time - what subtle, devious work - in the pursuit ofyour amusement. I loved Mart.

I aspire to the brisk, no bullshit style of Patricia Highsmith, I seek guidance from Lynn Coady, Lorrie Moore, Lydia Davis, and thesuperhuman Jennifer Egan. Also, George Saunders, Barbara Gowdy, and Raymond Carver, of course.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yetdone?

I toy with a one-person performance – where I’m theperson. Or maybe a musical...

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

There’s a chance I’d have ended up back in jail.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

The first word of fiction I ever set down was borne ofanger and frustration, and writing felt like the only option. I paint when I’mhappy. When something needs conquering, I write.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What wasthe last great film?

I loved Kick the Latch by Kathryn Scanlon. The lastgreat film is (and perhaps always will be) Border – the 2018 Swedish one,written by John Ajvide Lindqvist. Utterly transforming. Oh, but I also justwatched Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, which changedmy whole cellular makeup. Hoo!

20 - What are you currently working on?

Paintings. Big, defiantly joyful ones. I also have someof a novel started, currently concerning a factory and an accidental murder. I’llknow when it’s time to jump in and write the thing, but for now I scribble bitsand let them simmer while I paint and listen to true crime podcasts.

September 16, 2024

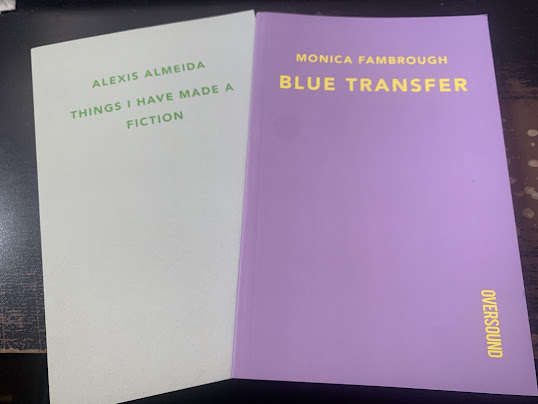

OVERSOUND: Monica Fambrough + Alexis Almeida,

Irecently garnered a handful of gracefully-produced softbound chapbooks producedthrough American poetry journal

OVERSOUND

, most of which were producedthrough their annual chapbook manuscript competition: Monica Fambrough’s BLUETRANSFER (2020) and Alexis Almeida’s THINGS I HAVE MADE A FICTION (2024).

Irecently garnered a handful of gracefully-produced softbound chapbooks producedthrough American poetry journal

OVERSOUND

, most of which were producedthrough their annual chapbook manuscript competition: Monica Fambrough’s BLUETRANSFER (2020) and Alexis Almeida’s THINGS I HAVE MADE A FICTION (2024).Ithas been a while since I’ve seen any work by Georgia-based poet Monica Fambrough, back to her full-length debut, Softcover (Boston MA: NaturalHistory Press, 2015) [see my review of such here], although her author biographysuggests a self-titled chapbook appeared in German translation by Sukultur atsome point. There are such delicate, honed lines to the eight poems acrossFambrough’s BLUE TRANSFER. “my wedding ring / thin / as a mint,” she writes, aspart of the opening poem, “A SHELTER.” She manages lengthy stretches acrosssuch lively accumulations of short phrases, one line following another, carefullyset with an ease that is crafted, careful and clear. “Our children, / asleep intheir beds / arrayed like canapés / in their particular positions,” she writes,as part of the poem “MEXICO POEM IN TWO PARTS,” “holding in the still space /of time between / when you think / the baby will wake up / and when the babywakes up.” Her poems hold such a soft intimacy against declaratives, offering asequence of quiet, precise details. Or, as the first third of that same openingpoem reads:

delicate blue transfer

the little life

I bring with

light

everything it

passes through

it passes through

beautifully

even Styrofoam

I will cling

to a ritual

until it is all

that is left

Ihaven’t seen much work by Brooklyn-based poet and translator Alexis Almeida—beyondthe chapbook-length translation she did of Buenos Aires poet RobertaIannamico’s Wreckage (Toad Press International Chapbook Series, 2017)[see my review of such here]—so I was quite pleased to catchTHINGS I HAVE MADE A FICTION (2024), winner of the 2023 OversoundChapbook Prize as selected by Andrew Zawacki. The pieces here, fourteen in all,are untitled prose poems that each begin with the prompt “I wrote a book where…”and swirl out across such lovely distances. As I’ve mentioned prior, I’mfascinated by works that hold to such deliberate echoes, the most overt in myrecollections being works by the late Noah Eli Gordon. These pieces aregestural, open and flow with a prose adorned and propelled through lyric butanchored by logic. Or, as the last sentence of the final piece reads, itself akind of encapsulation of the project as a whole: “So it went this way, whereinside the lists were other lists that started to leak and form paragraphs, andthe longer I wrote them, the more it felt like something was happening (awave), and what I had wanted, or failed to want was taking on the particularshapes of these sentences.” Might this be an excerpt of something larger,longer, even full-length? According to her author biography at the back of thisparticular title, her translation of Roberta Iannamico’s Many Poemsis forthcoming from The Song Cave this year, and her first full-length book, Caetano,is forthcoming next year with The Elephants. I am very eager to see where shegoes next.

I wrote a book aboutpulling, what is a word when pulled from inside another word, or a sound whenshaped from another sound, what is a story pulled from another one, what madethe original seem less true, where is a dream still pulling you in the morning,why do people say pulling an espresso shot, what does it feel like to write aword that immediately invokes a force in you, what becomes locked when youpull, what shuts down after so much effort, if someone turns away why does itpull in you, what is what pulls you to stay awake long into the night, or towardthe door in the morning, are you pulling, or waiting at the beginning ofsomething’s life, have you ever been so afraid as when you didn’t know which,it’s a constant feeling like something tilting inside you, like the walls oflanguage disappearing as soon as you wake up.

September 15, 2024

Keagan Hawthorne, After the Harvest

THE DARK

When she was little mymother wanted to hear

what the river had tosay.

She pressed her ear tothe ice

and it spoke.

A neighbour saw,

guessed where to chop ahole downstream.

A miracle, they said, ourLazarus.

Her father gave the man acow.

Three weeks in bed and noone asked

what the lights were likebeneath the ice,

what darkness.

A shame, she thought.

It was beautiful.

I’mjust now getting into Sackville, New Brunswick poet and letterpress printer (founderof Hardscrabble Press, who is also in the process of taking over GaspereauPress) Keagan Hawthorne’s full-length debut,

After the Harvest

(KentvilleNS: Gaspereau Press, 2023), a carved sequence of family stories cut and shapedinto stone. Hawthorne sets up a landscape of east coast barrens, every word in itsproper place, akin to the kind of Newfoundland patter and long descriptivephrases and sentences of Michael Crummey’s Passengers: Poems (TorontoON: Anansi, 2022) [see my review of such here]. “Well, you know, we had a fewgood years,” Hawthorne writes, to open the poem “THE BOOK OF RUTH,” “no kidsbut a nice house, jobs, / and when the end came it was mercifully quick. // Hismother moved in for the last few weeks / to help with care, and stayed on / afterthe funeral to help me clean things up.” There is a physicality to these poemsthat are quite interesting; a rhythm of storytelling, and a story properlytold, through the rhythm and patterns of first-person ease across such descriptivemotion. “It was a spring of record heat,” the poem “SPRING FEVER” begins, “whenyou walked down to the river, / found the pool above the beaver weir / and tookoff all your clothes.”

I’mjust now getting into Sackville, New Brunswick poet and letterpress printer (founderof Hardscrabble Press, who is also in the process of taking over GaspereauPress) Keagan Hawthorne’s full-length debut,

After the Harvest

(KentvilleNS: Gaspereau Press, 2023), a carved sequence of family stories cut and shapedinto stone. Hawthorne sets up a landscape of east coast barrens, every word in itsproper place, akin to the kind of Newfoundland patter and long descriptivephrases and sentences of Michael Crummey’s Passengers: Poems (TorontoON: Anansi, 2022) [see my review of such here]. “Well, you know, we had a fewgood years,” Hawthorne writes, to open the poem “THE BOOK OF RUTH,” “no kidsbut a nice house, jobs, / and when the end came it was mercifully quick. // Hismother moved in for the last few weeks / to help with care, and stayed on / afterthe funeral to help me clean things up.” There is a physicality to these poemsthat are quite interesting; a rhythm of storytelling, and a story properlytold, through the rhythm and patterns of first-person ease across such descriptivemotion. “It was a spring of record heat,” the poem “SPRING FEVER” begins, “whenyou walked down to the river, / found the pool above the beaver weir / and tookoff all your clothes.”

September 14, 2024

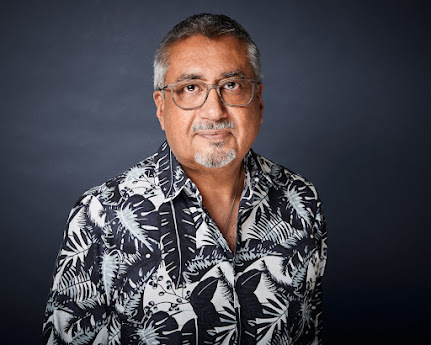

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Rajinderpal S. Pal

Rajinderpal S. Pal is acritically acclaimed writer and stage performer. He is the author of twocollections of award-winning poetry, pappaji wrote poetry in a language i cannot read and pulse. Born in India and raised in Great Britain,Pal has lived in many cities across North America and now resides in Toronto. HoweverFar Away is his first novel.

1 - Howdid your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

My firstbook, pappaji wrote poetry in a language i cannot read, was released in1998 by TSAR. The attention that this poetry collection received completelyexceeded my expectations. As well as winning the Writers Guild of Alberta awardfor Best First Book, the publication received a couple of mentions in the Globeand Mail and allowed me to do readings across the country. I have been workingon a New, Unpublished and Selected collection, working title The LesserShame. I really wish I knew then, at the time of writing my earlier poems, whatI know now about craft and structure. Writing and editing my debut novel, HoweverFar Away, I have gained a discipline and rigour which has previously eludedme. In some ways, I am covering similar ground to what I covered in my twopublished poetry collections (themes of family and tradition, love andcommitment) but the novel feels very different in terms of scope and reach.

2 - Howdid you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Myfather was a published and much-admired poet, and poetry readings were aregular occurrence in my childhood home. He wrote in Punjabi and Urdu, bothlanguages that I do not read or write. My father was only in my life for ashort time before he died of a heart attack. I was ten at the time. In my latetwenties I was desperate to understand my father: his life as a soldier, aheadmaster, a poet, what led him to move our family across continents, why hewrote, and what he wrote. Poetry seemed to be the natural medium to examinethis man and try to understand my relationship to him.

3 - Howlong does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I’llspeak to my novel, However Far Away. In June 2005 I was sitting on abench in Kitsilano Park. It was a beautiful sunny day, the beach, the ocean,the North Shore Mountains in full view. As I sat and surveyed all the activityaround me a determined looking South Asian man, approximately my age, ran pastme. I immediately began to wonder what this man might be running from orrunning toward. That afternoon, at the dining table of my basement apartment Iwrote seven pages of prose; an opening scene for what I imagined would be anovella. At that time, I was primarily a poet. I was not one for spontaneouswriting. For the next twelve years, immersed in my career in healthcare salesand marketing, I wrote very little. Occasionally, I would open the Word filefor Settle (the working title for However Far Away) and write aline, a paragraph or a scene but there was no substantial progress. In late2018 I was retired out of my career and had to admit I had run out of excusesto not tackle this larger project. I completed dozens of drafts before it was evensubmitted to House of Anansi Press. The finer edits, however, were onlycompleted once they had agreed to publish the book. The final shape only becameclear after my editor and I had reduced the manuscript from 130,000 words to90,000 words.

4 -Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an authorof short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you workingon a "book" from the very beginning?

Forpoetry I write individual pieces without a larger project in mind. For fictionI always had a larger project in mind, though just how large the project becameis a surprise.

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

Publicreadings are critical to the creative process for both poetry and fiction.Perhaps that is from growing up in a house where poetry was frequently read outloud. For me, both poetry and fiction have to work on the page and when spokenout loud.

6 - Doyou have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questionsare you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

I writefiction for the same reasons that I write poetry—as a way to understand, tocome to terms with, to uncover a nugget of truth, to seek (or, dare I say,create) beauty and meaning, and perhaps enlighten myself.

7 – Whatdo you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Ibelieve that there will always be a thirst for storytelling and meaning, that therumours of the death of poetry and fiction are much exaggerated. For sure newtechnologies like AI will have some impact but we will continue to create andsearch for meaning through literature, whether through a concrete poem, aghazal, or a long work of fiction.

8 - Doyou find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential(or both)?

Essential.I wish I had worked more closely with an editor for my two books of poetry.

9 - Whatis the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Before Ipublished my first book, Nicole Markotic said to me, “You need an editor whocould tell you to remove your favourite line in a poem in progress and you willconsider it.” Those are not Nicole’s exact words, but the sentiment has stayedwith me for over twenty-five years. The word “consider” is the most criticalword in that advice; you do not have to eliminate that line but you shouldquestion what purpose it might be serving in the poem and whether it isnecessary. The final decision is always yours.

10 - Howeasy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction)? What doyou see as the appeal?

Ifwriting a poem is the bull’s eye, then writing a novel is the entire bull, itslineage, its character, and what it ate today. You need to choose the formbased on what it is that you are trying to understand, to come to terms with,or uncover.

11 -What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? Howdoes a typical day (for you) begin?

Duringthe most intense periods of writing However Far Away I had a strictdaily schedule; three hours of writing each morning, two hours of writing andone hour of editing each afternoon. Most days I exceeded the scheduled numberof hours, but it was okay if there was an occasional day when I failed. I tookevenings off since I am a social being and needed the nourishment that goodconversation provided. I am looking forward to the time that my next projectwill require me to get back to a similar routine.

12 -When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

There isa list of books, films and music albums that always inspire me to create. Thatlist continues to shift and grow. It’s a long list, but some of the writersthat I turn to are Michael Ondaatje, Robert Hass, Jorie Graham, Hanif Kureishiand, more recently, Sally Rooney and Anna Burns. I would occasionally revisitthe film The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, especially for the twoscenes that I consider to be the most emotionally wrought ever put on film. Ifnothing else works a bit of travel and long exploratory walks seem to help.

13 -What fragrance reminds you of home?

AnIndian spice mix tempering in a pan.

14 -David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any otherforms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All ofthe above. I am as influenced and inspired to create art by film, theatre,contemporary dance, and music, as I am by books. If I am writing, I need to beactively engaged in other arts. I will carry a small notebook with meeverywhere I go and often write lines that will later make their way into apoem or a work of fiction. These lines might be inspired by anything from awork of art to psithurism to a beautiful horizon to overheard conversation.

15 -What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

If abook really strikes me, I will read it multiple times. There were a few booksthat were constant companions during the most productive periods of writing HoweverFar Away: The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes, Milkman byAnna Burns, Intimacy by Hanif Kureishi, All About Love byBell Hooks.

16 -What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I havean idea to create and produce a performance piece for stage incorporatingpoetry, music and film; something that could be performed at Fringe festivalsas well as at literary festivals.

17 - Ifyou could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

I had a thirty-yearcareer in sales and marketing in the healthcare industry. When I was retiredout of that career in 2018, I was able to fully focus on completing HoweverFar Away. In the future, I would like to facilitate creative writing workshops—poetryand fiction—but have no desire to be a full-time instructor. Other than that, Ijust want to create and stay healthy.

18 -What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Standingbeside an upstairs banister listening to emotional and powerful recitalsfloating up from the gathering of poets in the downstairs front-room.

19 -What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Soldiers,Hunters, Not Cowboys by Aaron Tucker. Film: Past Lives written anddirected by Celine Song.

20 -What are you currently working on?

As wellas the new and selected poetry collection, I am mapping out two possible worksof fiction.

September 13, 2024

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Ken Taylor and Fred Moten on selva oscura press

Fred Moten lives in New York with hiscomrade, Laura Harris, and their children, Lorenzo and Julian. He works in theDepartments of Performance Studies and Comparative Literature at New YorkUniversity.

Ken Taylor is the author of three booksof poetry, two chapbooks, three plays, and a collaborative work with twelveartists. found poem(s), with Ed Roberson, is forthcoming from Corbett vs.Dempsey—Ken’s photographs and Ed's poems.

1 – When did selva oscura press firststart? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started,if at all? And what have you learned through the process?

We want to publish books that we loveby writers whom we love. We are especially glad to publish first books and toimagine that these will be platforms that can propel their authors onto atrajectory in which their work will continue to be seen and heard. We also loverecovering and making available older texts that have fallen out of print andoff the map. And we are committed to seeking out and finding and publishing thework of black authors, authors of color, and queer and trans authors. We havebeen primarily focused on poetry, but we have been branching out into fictionand non-fiction prose and have some plays forthcoming, as well. We areespecially committed to making sure that the authors love the way their bookslook and so we are especially happy to work with authors who know how they wanttheir books to look.

2 – What first brought you topublishing?

In the Research Triangle of NorthCarolina, we were part of a great community of writers which included ShirletteAmmons, Joseph Donahue, Nathaniel Mackey, Pete Moore, Kate Pringle, Ken Rumbleand Magdalena Zurawski (among many others), all of whom had made it theirbusiness to serve the community by providing venues for people to read andpublish. We wanted to follow their example. Three Count Pour and selva oscuraemerged from that desire.

3 – What do you consider the role andresponsibilities, if any, of small publishing?

Get the word and the work out.

4 – What do you see your press doingthat no one else is?

There are so many presses servingpoetry in so many ways. Not sure we’re a step above or beyond. We lean intocollaboration. Listen. Are renewed with new enthusiasms that come our way withnew and established work.

5 – What do you see as the mosteffective way to get new books out into the world?

Lately it’s been Asterism Books. Theyhave been a godsend since SPD shuttered.

6 – How involved an editor are eitherof you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a lighttouch?

Our touch is very light. We don’t doline edits. We find books and writers that we like and trust them to get it howthey want it. We try to help them find that if they want or need us to.

7 – How do your books get distributed?What are your usual print runs?

Runs depend on the author. 200-400.Asterism Books is our new distributor. They do a good job at stuff we’re notmuch good at. We don’t have a lot of resources for promotions but try and helpwith at least one launch reading for each author.

8 – How many other people are involvedwith editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, howeffective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?

We keep it pretty close. Our copyeditor(Miles Champion) and our designer (Margaret Tedesco) do the lion share of thework in terms of grind and production. The benefits are that they are bothbadassed. No drawbacks yet.

9 – How has being an editor/publisherchanged the way you think about your own writing?

We both get to keep our heads in thegame. If we’re excited about something to publish, it usually inspires us towrite.

10 – How do you approach the idea ofpublishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ranCormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titlesduring their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bp Nichol.What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the wholequestion as irrelevant?

We’re not against it. We areprincipally focused on the work of others. We’ve talked about various projectswe’ve done that might work for selva oscura or Three Count Pour, and alsodiscussed supporting that work financially through other presses.

11 – How do you see selva oscura pressevolving?

One thing we want to do is get back todoing chapbooks, through our subprint/imprint Three Count Pour. Maybe that’s alittle bit more like revolving than evolving. We’d like to do them in smallbundles, like the Durham Suite that we published years ago, combiningwell-known and less well-known writers in one package. And we’d like thechapbooks to be art books. We want the book actually to be necessary, somethingheld in the hand as that which couldn’t have been any other way. This meansthat the writers will work in co-accompaniment with the book designer as wellas with visual artists.

12 – What, as a publisher, are you mostproud of accomplishing? What do you think people have overlooked about yourpublications? What is your biggest frustration?

I don’t think there have been any bigfrustrations. I think we both hope and intend to do a better and better job ofpromoting the books and supporting them after publication. The idea is not onlyto have a palpable and beautiful document of the work the authors do but alsoto get the books in the hands of sensitive, generous, and enthusiastic readers.

13 – Who were your early publishingmodels when starting out?

Initially it was chapbooks, and then anart/poetry collaboration, with the aim to add beautiful objects to the historyof folks doing this. We’ve haven’t tried to emulate any model specifically.

14 – How does selva oscura press workto engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large? Whatjournals or presses do you see selva oscura press in dialogue with? Howimportant do you see those dialogues, those conversations?

We just want to be working in concertwith, and be part of the complementary variety of, the community that is givento the general field of poetry, which we tend to think of, by way of Juliana Spahr, as “this connection of everyone with lungs.” We’re not picky and we’rehere militantly to mess with anyone who is so that the conversation can stayinfinite and real.

15 – Do you hold regular or occasionalreadings or launches? How important do you see public readings and otherevents?

We have had launches and readings foralmost all of the books and will do so for all the authors who desire that. ThePandemic but a temporary hold on that but we are now trying to catch up, and wewill. It’s important to get the sound of this writing into the world.

16 – How do you utilize the internet,if at all, to further your goals?

We have a web site, and social mediahandles, send out invites, but not working the internet much beyond that.That’s largely dictated by the time we have available.

17 – Do you take submissions? If so,what aren’t you looking for?

We don’t take unsolicited submissions.

18 – Tell me about three of your mostrecent titles, and why they’re special.

To Regard a Wave, by Sora Han, weaves physics andtranslation, translation and weaving, in a beautiful meditation on love andrevolution; Arvo Villars’s Violently Dancing Portraits can’t sit still,teaches how to withstand immersion in (im)migrant energy, kinda like Creole’s –aka Kreyól’s – blues as it pulses under Sonny’s (for all you beautiful Baldwinfans); and, in Shekhinah Speaks, Joy Ladin offers a prophetic transtheology that’s radical as every day.

September 12, 2024

Melanie Siebert, Signal Infinities

My review of Victoria, British Columbia poet and therapist Melanie Siebert’s second poetry collection,

Signal Infinities

(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2024),

is now online at Chris Banks' The Woodlot

. See here for my review of her full-length debut,

Deepwater Vee

(McClelland and Stewart, 2010).

My review of Victoria, British Columbia poet and therapist Melanie Siebert’s second poetry collection,

Signal Infinities

(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2024),

is now online at Chris Banks' The Woodlot

. See here for my review of her full-length debut,

Deepwater Vee

(McClelland and Stewart, 2010).

September 11, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Alison Stone

Alison Stone is theauthor of nine full-length collections, Informed (NYQ Books, 2024), To See What Rises (CW Books, 2023), Zombies at the Disco (Jacar Press,2020), Caught in the Myth (NYQ Books, 2019), Dazzle (Jacar Press, 2017),Masterplan, a book of collaborative poems with Eric Greinke (PresaPress, 2018), Ordinary Magic (NYQ Books, 2016), Dangerous Enough(Presa Press 2014), and They Sing at Midnight, which won the 2003 ManyMountains Moving Poetry Award; as well as three chapbooks. Her poems haveappeared in The Paris Review, Poetry, Ploughshares, Barrow Street,Poet Lore, and many other journals and anthologies. She has been awarded Poetry’s Frederick Bock Prize, New York Quarterly’s Madeline Sadin Award,and The Lyric’s Lyric Poetry Prize. Shewas Writer in Residence at LitSpace St. Pete. She is also a painter and thecreator of The Stone Tarot. A licensed psychotherapist, she has privatepractices in NYC and Nyack. https://alisonstone.info/ Youtube and TikTok – Alison Stone Poetry.

1 - How did yourfirst book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compareto your previous? How does it feel different?

The first booktaught me patience and how to change course. It was a finalist in many nationalcontests, beginning when I was in my early 20’s. I thought I’d publish it andthat would help me get a teaching position. But it didn’t end up winning untilI was 38. By that point I’d gone back tograd school and become a psychotherapist.

My new book is allformal poems, which is different from all my past collections. Most of them aremainly free verse, except for Dazzle(ghazals and anagram poems) and Zombiesat the Disco (all ghazals.)

2 - How did youcome to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I came to fictionfirst. I wrote a love poem to my beagle when I was 6 (“Your nose is wet andyou’re my pet. You’re brown and white, you never bite…”) but I was writing a“novel” (also about a dog) at the same time. I only finished the first twochapters. I was focused on fiction as an undergrad and only took a poetryworkshop because I needed to for graduation requirements. But my teacher, HugoWilliams, converted me.

3 - How long doesit take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initiallycome quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close totheir final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It completelydepends on the project. For OrdinaryMagic (a book with one poem for each tarot card), I did a lot of research.The same with Caught in the Myth. Iwas asked by a photographer to write poems to go with photos he’d taken of ancient sculptures. So I neededto learn about these historical figures in order to write. Some of the otherpoems are from Greek myths, so I’d research those as well.

The speed variesaccording to different projects as well. Some poems come out almost finished.Others need more substantial revisions.

4 - Where does apoem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

Again, it depends.Usually I start with poems and then they start to coalesce.

For individualpoems, I usually start with a phrase or a line. For ghazals, I start eitherwith a sound I want to explore or else a refrain.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I love doingreadings! I’m an introvert, but somehow I find them really enjoyable.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

That’s a greatquestion! I’m interested in stories – whose voices haven’t been heard? Howwould this tale be told from a different point of view? I’m also interested inhow traditional forms can work with contemporary subject matter. I’m not sureif there are any “current questions” for all poets. This is such a diverse,exciting time in poetry – so many different voices and perspectives.

7 – What do you seethe current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one?What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers help peoplefeel less alone. At least that’s what writing (including song lyrics) did anddoes for me. It’s a way of helping people open their hearts and minds.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ve never had one,but I’d love to. All my books have been published by small literary presses.Only once did I even get a copy editor. But no one to help me shape or improvethe work, like at the big houses.

9 - What is thebest piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Have something elsein your life you love as much as writing (Louis Simpson).

10 - How easy hasit been for you to move between genres (poetry to painting)? What do you see asthe appeal?

They are suchdifferent processes. Once I had children, I mostly stopped painting. I work inoil and couldn’t be covered in toxic paint if the baby needed me. Then I hurtmy arm/shoulder so I gave over doing the art for my book covers to my kid. ButI’m going to do the next one.

11 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I have no writingroutine, except during POMO, when I write a poem a day.

I get up at 6, doyoga, walk the dog, eat breakfast. During the school year I sometimes do dropoff. Then I start seeing clients.

12 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

Reading poetrymakes me want to write it. But I also let myself take breaks. Olga Broumas toldme when I was 24 to respect my silences, and I think that’s important.Capitalism is all about production, but art isn’t commerce.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

On rainy days, thesmell of dog. Otherwise I’d say cooking smells. Lots of garlic.

14 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music, nature,visual art. Politics, too, though that’s hardly an art form

15 - What otherwriters or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside ofyour work?

Gluck, Plath, Rilkeare my top three. Then Patricia Smith, Rita Dove, Diane Seuss.

16 - What would youlike to do that you haven't yet done?

Win a major poetryprize. See the Northern Lights. Be a grandmother (But no rush!).

17 - If you couldpick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, whatdo you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I have a full-timepractice as a Gestalt therapist. It counters the self-involvement of being anartist because it’s all about the other person.

18 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

I can’t carry atune. If I’d been able to, I would have wanted to front a band. But I’m toooff-key, even for punk.

19 - What was thelast great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just finishedrereading Middlemarch, and I’m sad tobe done. I don’t see a lot of films. This year we watched the Oscar finalists,and I enjoyed them all.

20 -What are you currently working on?

I have 3manuscripts in progress. I also invented a new poetic form.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

September 10, 2024

Apt. 9 Press at fifteen: SOME SILENCE: Notes on Small Press and APT. 9 PRESS: 2009-2024: A Checklist,

It is 2024. I am 37 yearsold. I have been writing poetry seriously for some two decades, and for most ofit I have also been engaged in some form in the world of the small press(whether as a reader, a poet, an editor, a publisher, a researcher, a bookseller).And yet, even after twenty years, it feel like I am just beginning in thisworld. (Cameron Anstee, SOME SILENCES: Noes on Small Press)

Tomark the fifteenth anniversary of his Apt. 9 Press, Ottawa poet, editor, critic and publisher Cameron Anstee has produced the limited edition chapbooks

SOME SILENCES: Notes on Small Press

(2024) and

APT. 9 PRESS: 2009-2024: A Checklist

(2024), each of which are hand-sewn, and produced with French flaps; both in anumbered first edition of eighty copies. Anstee’s chapbook and broadside publicationshave always held a quiet grace, a sleek and understated design on high-qualitypaper and sewn binding in limited editions [see some of the reviews I’ve postedon Apt. 9 Press publications over the years here and here and here and here andhere and here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here, etcetera, as well as his 2010 “12 or 20 (small press)” interview].If you aren’t aware of the work of Apt. 9 Press, the “Checklist” offers bibliographicinformation on some fifty chapbooks he’s produced through the press since 2009,as well as two full-length titles, two folios and a handful of ephemera, and a furtherselection of his own chapbooks under the side-imprint, “St. Andrew Books.” Ashe writes: “St. Andrew Books is an (unacknowledged) imprint of Apt. 9 Press. I startedit in 2011 to make a chapbook of my own to coincide with a reading. At thetime, I felt it was too soon in the life of Apt. 9 Press to self-publish underthe name, so the imprint was conceived. I have used it for 13 years now toself-publish chapbooks and leaflets when the impulse hits.”

Tomark the fifteenth anniversary of his Apt. 9 Press, Ottawa poet, editor, critic and publisher Cameron Anstee has produced the limited edition chapbooks

SOME SILENCES: Notes on Small Press

(2024) and

APT. 9 PRESS: 2009-2024: A Checklist

(2024), each of which are hand-sewn, and produced with French flaps; both in anumbered first edition of eighty copies. Anstee’s chapbook and broadside publicationshave always held a quiet grace, a sleek and understated design on high-qualitypaper and sewn binding in limited editions [see some of the reviews I’ve postedon Apt. 9 Press publications over the years here and here and here and here andhere and here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here, etcetera, as well as his 2010 “12 or 20 (small press)” interview].If you aren’t aware of the work of Apt. 9 Press, the “Checklist” offers bibliographicinformation on some fifty chapbooks he’s produced through the press since 2009,as well as two full-length titles, two folios and a handful of ephemera, and a furtherselection of his own chapbooks under the side-imprint, “St. Andrew Books.” Ashe writes: “St. Andrew Books is an (unacknowledged) imprint of Apt. 9 Press. I startedit in 2011 to make a chapbook of my own to coincide with a reading. At thetime, I felt it was too soon in the life of Apt. 9 Press to self-publish underthe name, so the imprint was conceived. I have used it for 13 years now toself-publish chapbooks and leaflets when the impulse hits.” Aspart of his “NOTES / ON APT. 9 PRESS / AT FIFTEEN YEARS” to open his checklist,Anstee begins: “The origin of the name of the press is unsurprising—I lived at328 Frank Street (Ottawa) in apartment 9 at the time. I considered FrankSt. Press, I think I may even have registered an email address, before mypartner suggested Apt. 9. I loved it; it rooted the press in the room in which Iwould be doing the work.” I am amused at the thought that he nearly took FrankStreet as his press name, especially given he offered the same title to thefirst chapbook of his poems published through above/ground press, Frank St.(2010). The specificity of place follows a fine trajectory of other presses namedfor their locations, whether Mansfield Press named for the editor/publisher’s homeaddress on Mansfield Avenue, Toronto, the myriad of Coach House affiliations(Coach House Press, Coach House Books and Coach House Printing) set in an oldCoach House behind Huron Street, Toronto, Alberta’s Red Deer College Press,which emerged out of Red Deer College (renamed Red Deer Press once the universityaffiliation had ended), or even Montreal’s Vehicule Press, a publisher that firstemerged in the 1970s out of the artist-run centre Vehicule Gallery. We namedour Chaudiere Books, as well, with a nod to the historic falls. I’m sure thereare plenty of other examples. Anstee’s imprint, “St. Andrew Books,” as well, isa project begun after Anstee and his partner relocated from Centretown into theByward Market (on St. Andrew Street, itself named for the Patron Saint ofScotland).

Acrossfifteen years, Anstee’s Apt. 9 Press has produced work by a flurry of contemporarypoets, from the emerging to the established, centred around the beginnings ofhis own public literary engagements through Carleton University’s in/words(titles by Justin Million, jesslyn delia smith, Dave Currie, Leah Mol, BenLadouceur, Jeremy Hanson-Finger, Rachael Simpson and Peter Gibbon) to encounteringthe wider Ottawa literary community (titles by Michael Dennis, Sandra Ridley,Monty Reid, William Hawkins, Phil Hall, Stephen Brockwell, Marilyn Irwin, RhondaDouglas and Christine McNair) and further, into the wider Canadian literarycommunity (titles by Leigh Nash, Nelson Ball, Stuart Ross, Beth Follett, Michaele. Casteels, Barbara Caruso and Jim Smith), and beyond, into the United States(a title by New York State-based Arkansas poet Lea Graham). His bibliographic checklistis thorough, and certain entries include short notes on each particularpublication, offering history on both the publication specifically and thepress generally, each of which provide, in Anstee’s way, short notes as teaserstoward a potential heft of further information. I quite enjoyed this note heincludes for Ottawa poet Dave Currie’s chapbook, Bird Facts (November 2014):“Dave somehow convinced CBC Radio to have him on the air one Saturday morningto discuss this book, which is comprised of made-up facts about birds. Ahandful of very confused customers came to the Ottawa Small Press Book Fair andpurchased copies.”

Thehistory of Apt. 9 follows a trajectory that coincides with Anstee’s personal interestsin writing, including his own critical and creative explorations, from the short,dense forms of poets such as Nelson Ball and Michael e. Casteels, widercommunity engagements across the scope of his own ever-widening landscape, tobibliographic and editorial projects he worked on, including around the work ofthe legendary and since-passed Ottawa poet and musician William Hawkins (a bibliographic folio, a chapbook reprint and editing a volume of his collected poems). While Anstee’s work with the press can be separated and is impressiveon its own, as with any poet-run press, his creative and critical work areessential to his work through Apt. 9 Press and vice versa; to attempt to fully understandone element requires an understanding of each element in turn (and how theyrelate to each other). Early on, as he writes in the essay-chapbook SOMESILENCES: Notes on Small Press:

In the earliest of thoseyears, when I was 18, during a second-year CanLit survey, Professor CollettTracey introduced me to Contact Press. I was immediately taken with the idea ofRaymond Souster quietly working throughout his life writing poems, and then fora decade or two in middle of the twentieth century, from his basement,making mimeographed books and magazines that re-shaped how poetry was writtenand published in this country. Shortly thereafter I began learning how to makechapbooks during my time working with In/Words, the little magazine and pressCollett ran. There were earlier moments too, such as when I was a teenager andgradually came to understand that my father’s collection of books was astonishing—booksby Beat and San Francisco and New York School writers filled the corners of ourhouse, books that were published by small presses run by editors who did itmostly because they felt these books should exist (though I couldn’t haveidentified them as small presses yet).

The lesson I took fromthese earliest encounters with books I found I cared about was that the act ofwriting can involve quite a bit more than simply writing. To write, in thesense of a lifelong practice embedded in a particular literary community, meansso many other things. I couldn’t have defined those other things when I firstencountered them, and honestly still struggle to articulate them today. In fact,through my first two decades doing this, in each overlapping role right up totoday, I have never been entirely at ease with the term small press. Ithas always felt elusive because it can mean so many different things to so manydifferent people, entirely dependent on the contexts of the conversation andits participants. That is something I confront anytime I try to speak about thesmall press or about what a writing practice is (about what my writing practiceis), given how intertwined and unstable the two are.

Anstee’sprose recollections are sharp, detailed and thoughtful; they are quite moving,articulating an essay-sequence of prose sections around elements of engagingwith small press, and his thoughts on small publishing generally, and his workthrough Apt. 9 Press specifically. “These silences are pressing for livingwriters and accompany the dead ones.” he writes, further along in the essay. “Youcan only let the work go I think, and hope that it finds the right hands in thefuture, that is, someone who will be sympathetic to it, who will open it andread it through and for whom it may spark a response, and who may come back andread it again.” Anstee’s prose through this piece, this chapbook, arecomparable to his chapbook production—sleek, carefully-honed and deeply precise—offeringmeditations around and through publishing. I know he’s already sitting on an as-yet-unpublishedcritical manuscript around small press (it seems criminal that such a work hasn’tyet seen book publication), but one might hope that he sees enough orders forthis particular title that it manages a reprint; it deserves to be read. Or, possibly,expanded upon. I could see this piece expanding into something full-length, anessential read on the specifics of literary engagement. Although, knowing theprecision and density of Anstee’s poems, perhaps everything he needed to say isalready here, set in a text that deserves even my own further engagement.

Books are great—of coursethey are!—but the idea of living a life in the small press or in poetry issomething else. There is no moment when you will have made it, no finish; thereis just the ongoing work of making poems, or books, or organizing events, orwhatever part of it you’re putting your own energy and resources behind. Maybe thatwork occasionally gets some attention, but it will pass so, so quickly. Publishbooks, and chapbooks, and leaflets, and weird little magazines, yes, as oftenas you want and are able to, but my feeling is that it is best to try to do sowith a hopeful eye on the much longer history you’re engaging with—the full scopeof which is forever out of sight—and with an understanding that your moment inthat history is both very small and totally essential, rather than on someimmediate pay off in public recognition or success (critical, financial) orwhatever other short-term validation is occasionally available.

So—and this is too easyto say—don’t be resentful that you didn’t get enough reviews, or didn’t winthat award, or weren’t published by that magazine. It matters a great deal andit doesn’t matter at all.

September 9, 2024

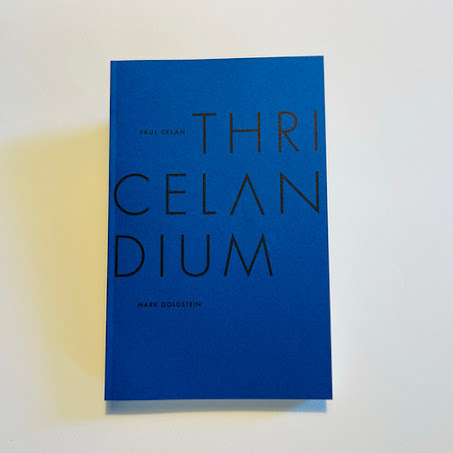

Paul Celan, Thricelandium, trans. Mark Goldstein

On finishing mytranslation of Eingedunkelt, I was startled to discover the 11 poemscomprising this work required a draft of over 100 pages. Rereading thesematerials, I came to understand that a response in English to Paul Celan’spoetry in German necessitates a material approach. The poem’sword-materiality in English first must parallel the word-materiality inDeutsch.

What do I mean by this? Ipropose considering this parallel materiality as a kind of alchemical Landschaftor Landscape. One wherein, amid its territory, we may inscribe Stein asStone – and as a result of the difference between words, we may begranted a glimpse of their glyphic (and lithic) associations as anomalies: achrysopoeia through which the under-poem may announce itself. (afterword, “ONTRANSLATING PAUL CELAN”)

Furtherto Toronto poet, editor, publisher, translator and critic Mark Goldstein’sexplorations through the work of Romanian-French poet Paul Celan (1920-1970) is

Thricelandium

(Toronto ON: Beautiful Outlaw Press, 2024), translated byand with a hefty introduction and even heftier afterword, “ON TRANSLATING PAULCELAN,” by Goldstein. Thricelandium is but one step in a much largertrajectory through Goldstein’s thinking around Celan’s work, with otherelements including: his poetry collection,

Tracelanguage: A Shared Breath

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2010) [see my review of such here]; his collection

PartThief, Part Carpenter

(Beautiful Outlaw, 2021), a book subtitled “SELECTEDPOETRY, ESSAYS, AND INTERVIEWS ON APPROPRIATION AND TRANSLATION” [see my review of such here]; as publisher of American poet Robert Kelly’s Earish (BeautifulOutlaw, 2022), a German-English “translation” of “Thirty Poems of Paul Celan” [see my review of such here];and as curator of the folio “Paul Celan/100” for periodicities: a journal ofpoetry and poetics, posted November 23, 2020 to mark the centenary ofCelan’s birth. It has been through the process of moving across such a sequencethat I’ve begun to appreciate the strength of Goldstein as a critic, offering athoroughness and detail-oriented precision to his thinking, working toarticulate his approach to the material and his translations of such, thatseems unique, especially one focused so heavily on the work of a single,particular author. Honestly, I’m having an enormously difficult time notreprinting whole swaths of his stunningly-thorough introduction, which dealswith, among other considerations, Goldstein’s approach to the translation andhow Celan’s work helped him develop his own writing. As Goldstein wrote as part of his “A Prefatory Note:” for the “Paul Celan/100” folio:

Furtherto Toronto poet, editor, publisher, translator and critic Mark Goldstein’sexplorations through the work of Romanian-French poet Paul Celan (1920-1970) is

Thricelandium

(Toronto ON: Beautiful Outlaw Press, 2024), translated byand with a hefty introduction and even heftier afterword, “ON TRANSLATING PAULCELAN,” by Goldstein. Thricelandium is but one step in a much largertrajectory through Goldstein’s thinking around Celan’s work, with otherelements including: his poetry collection,

Tracelanguage: A Shared Breath

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2010) [see my review of such here]; his collection

PartThief, Part Carpenter

(Beautiful Outlaw, 2021), a book subtitled “SELECTEDPOETRY, ESSAYS, AND INTERVIEWS ON APPROPRIATION AND TRANSLATION” [see my review of such here]; as publisher of American poet Robert Kelly’s Earish (BeautifulOutlaw, 2022), a German-English “translation” of “Thirty Poems of Paul Celan” [see my review of such here];and as curator of the folio “Paul Celan/100” for periodicities: a journal ofpoetry and poetics, posted November 23, 2020 to mark the centenary ofCelan’s birth. It has been through the process of moving across such a sequencethat I’ve begun to appreciate the strength of Goldstein as a critic, offering athoroughness and detail-oriented precision to his thinking, working toarticulate his approach to the material and his translations of such, thatseems unique, especially one focused so heavily on the work of a single,particular author. Honestly, I’m having an enormously difficult time notreprinting whole swaths of his stunningly-thorough introduction, which dealswith, among other considerations, Goldstein’s approach to the translation andhow Celan’s work helped him develop his own writing. As Goldstein wrote as part of his “A Prefatory Note:” for the “Paul Celan/100” folio:I came to the work ofPaul Celan in my 20s through the common entryway of his poem Todesfuge[Death Fugue]. I suspect that I first encountered it in anthology — likelyeither in Jerome Rothenberg’s translation found in Poems for the Millenniumor in John Felstiner’s translation as it appears in Against Forgetting:Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness.

In each case I wasstartled by Celan’s power of expression, and as a Jew, I obsessed over hisearly use of the imagery of the Shoah. In time, as I read through his books, Ibegan to develop an ever-expanding sense of their territory. Moreover, as thewriting neared its terminus, I came to recognize my estrangement with it too —one born from its profound and compelling angularity.

I’velong been intrigued by Goldstein’s long engagement with the work of Celan, asdeep and rich as his engagement with the work of Perth, Ontario poet Phil Hall, fromBeautiful Outlaw having produced multiple chapbooks and books by Phil Hall, tothe recent ANYWORD: A FESTSCHRIFT FOR PHIL HALL, eds. Mark Goldstein andJaclyn Piudik (Beautiful Outlaw Press, 2024) [see my review of such here]. Onthe surface, at least, there seems far more affinity between the work of Celanand Hall than the two life-long focuses of Ottawa poet, publisher andbibliographer jwcurry’s writing life, bpNichol and Frank Zappa, although eitherof these parings (or trios, really) would make absolutely fascinating theses bysome brave academic at some point.

Acrossthree poem-sequences—“ATEMKRISTALL · BREATHCRYSTAL,” “EINGEDUNKELT ·ENDARKENED” and “SCHWARZMAUT · BLACKTOLL”—there is a lovely contrary anddelicate quality to these poems, offered both in the original German alongsideGoldstein’s translation. The language swirls, moving in and out, and through,blended and perpetual meanings that become clear as one moves through, holdinga firm foundation of clarity by the very means of those swirlings, thosegestural sweeps. As Goldstein’s translation offers, early on in the first sequence:

Etched in the undreamt,

a sleeplesslywandered-through breadland

casts up the life-mount.

From its crumb

you knead our names anew,

which I, an eye

in kind

on each finger,

feel for

a place, through which I

can awaken to you,

a bright

hungercandle in mouth.