Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 43

August 29, 2024

Samuel Ace, I want to start by saying

I want to start by sayingI hear the filter in the turtle tank like a fountain.

I want to start by sayinglike a fountain in the middle of a field of wildflowers.

I want to start by sayingthat today would have been my father’s 84th birthday,

that he died eighteen days before his 79th.

I want to start by sayingthat he was young and that death took him by surprise.

I want to start by sayingthat my mother died nine months ago, less than four

and a half years after my father.

I want to start by sayingthe beginning of this sentence.

I want to start by sayingthat a child could have been born in that time.

I want to start by sayingthat a whole year has gone by since my godchild’s birth.

Andso begins the accumulative book-length poem by American poet Samuel Ace, thedeeply intimate

I want to start by saying

(Cleveland ON: Cleveland StateUniversity Poetry Center, 2024), a work composed from a central, repeatingprompt. The structure is reminiscent of the echoes the late Noah Eli Gordonproffered, composing book-length suites of lyrics, each poem of which sharedthe same title—specifically

Is That the Sound of a Piano Coming from Several Houses Down?

(New York NY: Solid Objects, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Source

(New York NY: Futurepoem Books, 2011) [see my review of such here]—or, perhaps a better example, the late Saskatchewan poet John Newlove’s poem “Ride Off Any Horizon,” a poem that returned to that samecentral, repeated mantra (one he originally composed with the idea of removing,aiming to utilize as prompt-only, but then couldn’t remove once the poem was fleshedout). “I want to start by saying,” Ace writes, line after line after line,allowing that anchor to hold whatever swirling directions or digressions the textmight offer, working through the effects that history, prejudice and grief hason the body and the heart. I want to start by saying articulates past racialviolence in Cleveland, subdivisions, loss, “trans and queer geographics offamily and home,” chronic illness, love and parenting, stretched across onehundred and fifty pages and into the hundreds of accumulated direct statements.Amid a particular poignant cluster, he writes: “I want to start by saying that Iaccepted the conditions of my father’s love.” There is something of thecatch-all to Ace’s subject matter, the perpetually-begun allowing the narrativesto move in near-infinite directions. As it is, the poem loops, layers andreturns, offering narratives that are complicated, as is often the way offamily, writing of love and of fear and of a grief that never truly goes away. Further,on his father: “I want to start by saying I was frightened to upset the balanceof our connection.”

Andso begins the accumulative book-length poem by American poet Samuel Ace, thedeeply intimate

I want to start by saying

(Cleveland ON: Cleveland StateUniversity Poetry Center, 2024), a work composed from a central, repeatingprompt. The structure is reminiscent of the echoes the late Noah Eli Gordonproffered, composing book-length suites of lyrics, each poem of which sharedthe same title—specifically

Is That the Sound of a Piano Coming from Several Houses Down?

(New York NY: Solid Objects, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Source

(New York NY: Futurepoem Books, 2011) [see my review of such here]—or, perhaps a better example, the late Saskatchewan poet John Newlove’s poem “Ride Off Any Horizon,” a poem that returned to that samecentral, repeated mantra (one he originally composed with the idea of removing,aiming to utilize as prompt-only, but then couldn’t remove once the poem was fleshedout). “I want to start by saying,” Ace writes, line after line after line,allowing that anchor to hold whatever swirling directions or digressions the textmight offer, working through the effects that history, prejudice and grief hason the body and the heart. I want to start by saying articulates past racialviolence in Cleveland, subdivisions, loss, “trans and queer geographics offamily and home,” chronic illness, love and parenting, stretched across onehundred and fifty pages and into the hundreds of accumulated direct statements.Amid a particular poignant cluster, he writes: “I want to start by saying that Iaccepted the conditions of my father’s love.” There is something of thecatch-all to Ace’s subject matter, the perpetually-begun allowing the narrativesto move in near-infinite directions. As it is, the poem loops, layers andreturns, offering narratives that are complicated, as is often the way offamily, writing of love and of fear and of a grief that never truly goes away. Further,on his father: “I want to start by saying I was frightened to upset the balanceof our connection.”I want to start by saying that I’vebeen out of the house twice today.

I want to start by saying that now Iam sitting with a friend over coffee.

She mourns the loss offriends because she’s in love with someone who is trans.

I want to start by saying thefamiliarity of so many stories.

I want to start by saying that I mournthe rise of rivers, the smell of creosote,

the relief of summer monsoons.

Andyet, through Ace’s perpetual sequence of beginnings, one might even comparethis book-length poem to the late Alberta poet Robert Kroetsch’s conversationsof the delay, delay, delay: his tantric approach to the long poem, always backto that central point; simultaneously moving perpetually outward and back tothe beginning. “I want to start by saying the deep orange skies of the monsoon.”he writes, mid-way through the collection. “I want to start by saying we havereturned to Tucson.” Set into an ongoingness, the lines and poems of Samuel Ace’sI want to start by saying is structured into clusters, allowing thebook-length suite a rhythm that doesn’t overwhelm, but unfolds, one self-containedcluster at a time. His lines and layerings are deeply intimate, setting down adeeply felt moment of grace and contemplation. The book moves through thestrands and layers of daily journal, writing of daily activity and thoughts aswell as where he emerged; how those moments helped define his choices through theability to reject small-mindeded prejudices. Through the threads of I wantto start by saying, Samuel Ace may be articulating where he emerged, butall that he is not; all he has gained, has garnered, and all he has leftbehind. As he writes, early on:

I want to start by sayingperfect in what world.

I want to start by sayingdesire.

August 28, 2024

Rae Armantrout, Go Figure

REASONS

1

The snake was a fall guy.

That tree

was temptation enough.

Staged apples,

drop-dead gorgeous.

2.

“Not in my body!”

they shout.

Benzene in the shampoo;

lead in the water;

pesticide in fruit.

They mean the newvaccine, but

isn’t there more to it?

Water on fire;

neonicotinoids in nectar;

black and tarry

stools

Thelatest from San Diego poet Rae Armantrout [see my review of her prior collection here] is

Go Figure

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press,2024), adding a further heft to an already heft of multiple award-winning poetrycollections going back decades. There is something intriguing about how thepoems in Go Figure cluster, offering Armantrout as less a poet of single,self-contained poems than sequences of gestural sweeps that cohere into this meditativebook-length suite, threading through numerous ebbs and flows as she goes. Herpoems interact with each other, including poems that end sans punctuation,suggesting a kind of ongoingness, beyond the scope of the single page. As theopening of the poem “SHRINK WRAP” reads: “An idea is / an arrangement // ofpictures / of things // shrunken / to fit // in the brain / of a human.” Armantrout’spoems are constructed through extended lines of precise, abstract thinking,providing specifics that accumulate into something far larger, and far morecoherent, than the sum of their parts. Armantrout’s poems throughout GoFigure offer points on a grid progressing a single extended sequence ofthought, as the author addresses culture, climate and financial crises, as wellas echoes and influence from her grandchildren. At the core, Armantrout’s poemsarticulate how our experiences are held by and solidified through words, thevery foundation of language that allow shape and coherence, meaning and contextto those very same experiences. As the poem “DOTS” opens:

Thelatest from San Diego poet Rae Armantrout [see my review of her prior collection here] is

Go Figure

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press,2024), adding a further heft to an already heft of multiple award-winning poetrycollections going back decades. There is something intriguing about how thepoems in Go Figure cluster, offering Armantrout as less a poet of single,self-contained poems than sequences of gestural sweeps that cohere into this meditativebook-length suite, threading through numerous ebbs and flows as she goes. Herpoems interact with each other, including poems that end sans punctuation,suggesting a kind of ongoingness, beyond the scope of the single page. As theopening of the poem “SHRINK WRAP” reads: “An idea is / an arrangement // ofpictures / of things // shrunken / to fit // in the brain / of a human.” Armantrout’spoems are constructed through extended lines of precise, abstract thinking,providing specifics that accumulate into something far larger, and far morecoherent, than the sum of their parts. Armantrout’s poems throughout GoFigure offer points on a grid progressing a single extended sequence ofthought, as the author addresses culture, climate and financial crises, as wellas echoes and influence from her grandchildren. At the core, Armantrout’s poemsarticulate how our experiences are held by and solidified through words, thevery foundation of language that allow shape and coherence, meaning and contextto those very same experiences. As the poem “DOTS” opens:Poems elongate moments.

“My pee is hot,” shesaid,

dreamily, mildly

surprised

Thereis something, too, about the openness of her lyric: if you haven’t readArmantrout’s work before, one might say that any book of hers might be a goodplace to start, but I’ll say this: if you haven’t read her work before, GoFigure is a good place to start. Or, as the first part of the two-parttitle poem reads:

First she made up theschedule,

and the rules,

Then the desire to breakthem or,

worse yet,

the yen to follow them.

You put your left footout;

you pull your left footin.

You do it all again

and laugh.

What next?

“Go figure,” she said.

Line up your letters

and shake them all about.

Play CAT,

then TAG.

Someone will play dead.

August 27, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jaz Papadopoulos

jaz papadopoulos (they/them) is an interdisciplinary writer, educator and video artist. They hold an MFA from the University of British Columbia and are a Lambda Literary Fellow. A self-described emotionalist and avid Anne Carson fan, jaz is interested in media, horticulture, lyricism, nervous systems, anarchism and erotics. Originally from Treaty 1 territory, jaz currently resides on unceded Syilx lands.

I Feel That Way Too

is their debut poetry collection.

jaz papadopoulos (they/them) is an interdisciplinary writer, educator and video artist. They hold an MFA from the University of British Columbia and are a Lambda Literary Fellow. A self-described emotionalist and avid Anne Carson fan, jaz is interested in media, horticulture, lyricism, nervous systems, anarchism and erotics. Originally from Treaty 1 territory, jaz currently resides on unceded Syilx lands.

I Feel That Way Too

is their debut poetry collection.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

This is my first book, and it hasn't quite come out yet, so it's hard to say! Probably, it has been extraordinary for my self-esteem and self-perception as a writer.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I'd say I came to clowning first, and then critical theory, and then came to see experimental writing as the clowning of language. My poetry (and non-fiction) are also fairly hybridized, lyrical forms: I'll write an essay, and people call it a poem. For me, various forms are just part of the process, and I don't know until the last edits what genre the final form will take.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It depends on the context. Am I writing on contract, with a set deadline? I'll take notes for 90% of the time, and then write the entire thing in the last 10% of days. If I'm writing for my own process, well, it's even slower; there will likely never be a final shape because without an externally-imposed deadline, I'll likely never finish a thing. I think I could pull 4+ books out of all the half-writings I have tucked in notebooks in my bookshelf.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I'm someone who loves puzzles. I love the chaos of a pile of pieces which, in their pile-form, are meaningless and frustrating. I get immense pleasure from the slow process of organizing the pieces, finding the similar shapes and colours, and painstakingly organizing them into shapes that make sense.

The same is true for my writing. Things start as a feeling, an image, a colour blooming in the chest. I write on sentence/paragraph at a time, and then eventually I collect all the little fragments, cut the pieces of paper into squares, and arrange and rearrange them until I like the final shape. (Yes, I literally print things off, cut them up, and arrange them all over the floor. To my cat's delight.)

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

If all I did was talk into a microphone, I would be so happy.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

There is so much I could say here. I am obsessed––obsessed––with language. I see language as the meaning-making tool that translates the world around us into our minds, and mediates nearly all our experiences. Because of this, it's also a meaning-making tool in the context of power, oppression and freedom. I'm heavily influenced by Foucault in this way (like I said, I came to poetry through critical theory.)

Orwell's 1984 is a great example of how a government limits the thoughts of its people through language; the way news and media outlets attach specific words to marginalized people is another one (see: comparisons of how the war in Ukraine and the genocide in Palestine are described differently). Words shape how we think about things, and how words create oppression versus freedom is my main concern most of the time. I think as we move into an increasingly-online world of increasingly partitioned media, AI-generated (false) information, and low media literacy, this will more and more become a question concerning everyone.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I'm not prescriptive about this. I think my own role as a writer in larger culture is to help people see nuance––beauty and violence––in the mundane.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I prefer it! I love being in collaboration, and hearing how an outside mind perceives what I'm communicating. (Please, someone, invite me to your writing group.)

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

This is the Anne Carson quote currently sticky-noted to my desktop: "The things you link are not in your control...But how you link them shows the nature of your mind." It gives me a sense of confidence and peace about my writerly impulses. I think the nature of my mind is pretty interesting, so why wouldn't I want to share it?!

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I mostly do contract work, so my routine shifts every couple of months based on what's going on in my life. Which is to say, routine is a fantasy that mostly eludes me. The ideal would be: wake up, short meditation, coffee while writing morning pages, and then on with the day.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I research! Sometimes that looks like reading, other times it's making people talk at me on the topic at hand.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The warmth of cooking in the air. Nivea chapstick. Home Depot.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

For me, everything is rooted in relationship. I had a huge "aha" moment when reading T. Fleischmann's Time Is the Thing a Body Moves Through, when the author described Felix Gonzalez-Torres' art practice as always making things for his lover, Ross. Everything as a love letter. I am a very romantically-inclined person, and my art practice became much clearer to me when I considered every word on the page to ultimately be a love letter with a specific recipient in mind.

All that said, I think any productive material (a book, a tapestry, a leaf-covered tree) can inform me. What is this all if not some form of information?

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Anne Carson and Edward Said are everything to me. Jeanette Winterson has done a lot. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. Dorothea Lasky. Hera Lindsay Bird.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Currently I'm seeking a 2 gallon jar to make my first batch of kombucha (10 years late, I know).

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

There are alternate universes where I am a contemporary dancer, a lawyer, a business mogul, a house spouse.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Ah, but I do both/all! But I would say that having financial stability is what has allowed me to dedicate so much time to writing. If I had to work more, I would never have enough space in my brain to let the words bounce around.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Noopiming: The Cure for White Ladies by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson; Piaffe by director Ann Oren.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Besides my own web copy? lol. Fragments about my summer garlic farming with friends. Specifically, about managing our group chat :)

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

August 26, 2024

Julie Carr, UNDERSCORE

Sentences I’ve often said

The unmanifested face wasmy mother’s and I kissed it.

She was very near phobicso we kept things quiet.

With a pencil in my mouthI wrote on my tongue: loved, unloved.

I am hypocriticallyawake.

Thelatest from Denver poet Julie Carr is the collection

UNDERSCORE

(OaklandCA: Omnidawn, 2024), following a whole slew of titles, including

Mead: An Epithalamion

(University of Georgia Press, 2004),

Equivocal

(AliceJames Books, 2007),

100 Notes on Violence

(Ahsahta Press, 2010; Omnidawn,2023),

Sarah-Of Fragments and Lines

(Coffee House Press, 2010),

Rag

(Omnidawn, 2014) [see my review of such here],

Think Tank

(New York NY:Solid Objects, 2015) [see my review of such here],

Objects from a Borrowed Confession

(Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2017) [see my review of such here] and

Real Life: An Installation

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2018) [see my review of such here]. As the colophon offers on the collection, thecollection “is dedicated to two of Carr’s foundational teachers, the dancerNancy Stark Smith and the poet Jean Valentine, both of whom died in 2020.Elegiac and tender-at-times erotic at other times bitter—these poems explorethe passions of friendship and love for the living and the dead.”

Thelatest from Denver poet Julie Carr is the collection

UNDERSCORE

(OaklandCA: Omnidawn, 2024), following a whole slew of titles, including

Mead: An Epithalamion

(University of Georgia Press, 2004),

Equivocal

(AliceJames Books, 2007),

100 Notes on Violence

(Ahsahta Press, 2010; Omnidawn,2023),

Sarah-Of Fragments and Lines

(Coffee House Press, 2010),

Rag

(Omnidawn, 2014) [see my review of such here],

Think Tank

(New York NY:Solid Objects, 2015) [see my review of such here],

Objects from a Borrowed Confession

(Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2017) [see my review of such here] and

Real Life: An Installation

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2018) [see my review of such here]. As the colophon offers on the collection, thecollection “is dedicated to two of Carr’s foundational teachers, the dancerNancy Stark Smith and the poet Jean Valentine, both of whom died in 2020.Elegiac and tender-at-times erotic at other times bitter—these poems explorethe passions of friendship and love for the living and the dead.”Thepoems hold both the tension of the pandemic-era lockdowns and an outreach, composingpoems for an array of friends and friendships, including two important friendsand mentors who died during the first year of Covid-19 pandemic lockdown: American dancer Nancy Stark Smith (1952-2020) and poet Jean Valentine (1934-2020), towhom the collection is dedicated. As the opening poem, “Was the world,”ends: “Cruising and wordless in its // breadth breaching river’s dusk // fromout of the past of the // hills, it heads down // into dust, for and of it.” Underscoredby a series of movements and music, Carr’s title emerges from Nancy Stark Smith’s“long-form dance improvisational structure,” one that has been “evolving since1990 and is practiced all over the globe.” From Smith’s own website:

The Underscore is avehicle for incorporating Contact Improvisation into a broader arena ofimprovisational dance practice; for developing greater ease dancing inspherical space—alone and with others; and for integrating kinesthetic andcompositional concerns while improvising. It allows for a full spectrum ofenergetic and physical expressions, embodying a range of forms and changingstates. Its practice is familiar yet unpredictable.

The practice—usually 3 to4 hours in length—progresses through a broad range of dynamic states, includinglong periods of very small, private, and quiet internal activity and othertimes of higher energy and interactive dancing.

Heldto that pandemic-era as a kind of lyric portrait of the author’s attentionsduring that period, the poems in UNDERSCORE are made up of a myriad ofprecise lyric threads, sharp and supple as glass; straight lines and statements,whether direct or indirect, that strike, sleek and overlap. “Out-gutted andcried-out,” her poem “100 days” begins, “I left the house for food. // I would,I thought, walk the alley / with a phone strapped to my forehead like a lamp.// To cough, to soak a pillow, to take it, to yearn for the hand of a mother, /not your mother, not anyone’s, an un-mother, an unknowable un-hand of an /un-mother to no one.” Carr composes birthday poems, letters and collaborativecalls-and-response (including one I was part of, which resulted in a collaborative chapbook; her poems subsequently reworked for the sake of this currentcollection). UNDERSCORE works through revisions, declarations, dedications,contemplations and scraps, all held in pristine, rhythmic harmony. From the extendedlyric “17 letters for Lisa at the start [3.12.20 – 4.30.20],” a poemthat suggests a reference to her friend, the Austin, Texas-based poet Lisa Olstein, with whom she composed the collaborative call-and-response non-fictioncollection, Climate (Essay Press, 2022) [see my review of such here]:

Because you need to rest,I speak to you where you cannot hear me. The kids are

curled or flat open: newand newish leaves. The pathogens in the house, the yeast.

There’sa structural echo here reminiscent of the carved lines of Equivocal (which,until this current collection, had been the collection of Carr’s I felt thedeepest kinship with or connection to), a concordance and weave of lines and lyrics,held together as a kind of pastiche. “She said it’s not done with you yet. I agreed,”she writes, to open the prose poem “It,” “but had no way to approach it,to find out what it wanted from me that it had not yet got.” The poems in UNDERSCOREoffer a halt, a halt, a hush; a carved, sharp sequence of accumulating linesset across an incredible rhythm and pacing that propels, pivots and swings,such as the poem “Apples,” dedicated “for Patti Siedman (1944-2022),”that includes:

I would not allow her toleave me is a confused object.

Like a dinner plate in abookshelf, or a glass of coiled guitar strings.

I keep saying five, butthere were six.

For how do we count thefaces of the dead?

August 25, 2024

new from above/ground press: Rhodes, Smith, McElroy, Pittella, Pirie, Banks, Farrant, Hajnoczky + Touch the Donkey #42,

It’s Here / All the Beauty / I Told You About, by Shane Rhodes $6 ; Enter the Hyperreal, by Mahaila Smith $5 ; Small Consonants, by Gil McElroy $5 ; footnotes after Lorca, by Carlos A. Pittella $5 ; Rushing Dusk, by Pearl Pirie $5 ; Tiny Grass Is Dreaming, by Chris Banks $5 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #42 : with new poems by Grant Wilkins, Russell Carisse, Lori Anderson Moseman, Ariana Nash, Wanda Praamsma, Taylor Brown, JoAnna Novak and John Levy $8 ; The Literary Cow Festival, by M.A.C. Farrant $5 ; By the Shores of Issyk-Kul, by Helen Hajnoczky $5 ;

It’s Here / All the Beauty / I Told You About, by Shane Rhodes $6 ; Enter the Hyperreal, by Mahaila Smith $5 ; Small Consonants, by Gil McElroy $5 ; footnotes after Lorca, by Carlos A. Pittella $5 ; Rushing Dusk, by Pearl Pirie $5 ; Tiny Grass Is Dreaming, by Chris Banks $5 ; Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] #42 : with new poems by Grant Wilkins, Russell Carisse, Lori Anderson Moseman, Ariana Nash, Wanda Praamsma, Taylor Brown, JoAnna Novak and John Levy $8 ; The Literary Cow Festival, by M.A.C. Farrant $5 ; By the Shores of Issyk-Kul, by Helen Hajnoczky $5 ; keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material;

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

July-August 2024

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; in US, add $2; outside North America, add $5) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9. E-transfer or PayPal at at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com or the PayPal button (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles, or click on any of the extensive list of names on the sidebar (many, many things are still in print).

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

DON'T FORGET THAT THERE IS LESS THAN A WEEK LEFT IN THE BIG 31ST ANNIVERSARY RIDICULOUS SALE; see my report on the 31st anniversary reading/launch/event held in August here; and: at the anniversary party, I did offer that anyone who wished to subscribe to the press from this moment right now through to the end of 2025 could for the low price of $100 Canadian (for American addresses, $100 US), which I'm willing to offer here as well, an offer good until the end of this month (just send me an email: rob_mclennan (at) hotmail (dot) com).

Forthcoming chapbooks by: Sue Landers, Jason Heroux and Dag T. Straumsvag, Vik Shirley, Alice Burdick, Susan Gevirtz, Carter Mckenzie, Maxwell Gontarek, Conal Smiley, Ian FitzGerald, Nate Logan, Peter Jaeger, Noah Berlatsky, ryan fitzpatrick, russell carisse, JoAnna Novak, Julia Cohen, Andrew Brenza, Mckenzie Strath, John Levy, alex benedict, Ryan Skrabalak, Terri Witek, David Phillips + Scott Inniss! And there’s totally still time to subscribe for 2024, by the way (backdating to January 1st, obviously).

August 24, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Cristalle Smith

Cristalle Smith [photo credit: Ryan Lee] has been published in ARCPoetry, CV2, subTerrain and more. She won the Lush TriumphantAward for Creative Nonfiction in 2020 and has a chapbook with Frog HollowPress. She lives in Calgary, Alberta with her son.

Invisible Lives

isher debut poetry collection.

Cristalle Smith [photo credit: Ryan Lee] has been published in ARCPoetry, CV2, subTerrain and more. She won the Lush TriumphantAward for Creative Nonfiction in 2020 and has a chapbook with Frog HollowPress. She lives in Calgary, Alberta with her son.

Invisible Lives

isher debut poetry collection. 1- How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Thisis my first book, so excited! At 37, I think I’m a bit later to the game thansome of my peers. That’s okay though, Ifeel like I’m on a different timeline.

Theprocess of writing my book really changed my life. I grew up in a lot of upheaval and poverty. We moved frequently—including large movesfrom Airdrie, Alberta to Water’s Lake, Florida (moves too numerous tolist). Like my mother, I dropped out ofhigh school and worked.

Asan adult, I went back to school to get away from working minimum wage at Subwayas a single mom. I had just left anabusive marriage and felt lost. I wokeup each day and did what was in front of me, placing one foot in front of theother—making moves myself from Moscow, Idaho to Kelowna, British Columbia.

InKelowna, I had no furniture and made a bed for my son out of my clothes andsome blankets on the floor. I slept on the bare floor. I eventually got some furniture through thehelp of a women’s shelter. I kept goingto class and kept going no matter what. Each day, one after the other.

Inever thought someone like me could be a writer. Practical concerns and the practicallyoriented world told me I shouldn’t bet on art for liberation from poverty. However, I signed up for a creative writingclass on a whim and then I got introduced to the world of writing by MattRader, Michael V. Smith, Nancy Holmes, Anne Flemming, and Margo Tamez. My life clicked into place when I spent myenergy on writing creative nonfiction and poetry. Lyrical experimentation allowed me theintellectual and artistic freedom I needed so desperately. I applied to the MFA at UBC Okanagan and Iwrote under the supervision of Matt Rader.

MyMFA manuscript became my book. Theprocess made me learn that I could be an artist. It was life changing to go from beingcloistered in silence to solidified in lyrical expression.

2- How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Istruggle at times with genre conventions and stricter boundaries between poetryand creative nonfiction. I think I workin a hybridized space of creative nonfiction and poetry—maybe I’m anexperimental lyricist.

Toget it out of the way, I’m not a fiction writer because I just gotta respond tothose poets I love so much. I want to bein that long and ongoing poetic conversation even if I’m just a quietcontributor from the sidelines.

Sometimespeople tell (what are to me) very funny narratives about what povertymeans. You might hear someone saysomething like, “Poor people can’t understand such and such academic jargon…”and I have to chuckle to myself. I grewup poor in Alberta, Canada and then later rural Florida. Living poverty as asingle mom myself felt almost natural, but my world was always full of poetryand conversation. My stepdad got meinterested in W.B. Yeats as we drove backroads to the tent where we lived innorth Florida. These conversations led to my love of Yeats, Langston Hughes,Countee Cullen, Sonia Sanchez, and many more. I remember my stepdad explained in detail “Cuchulain’s Fight with the Sea” and to this day it’s still one of my favorite poems.

Poetryis a vignette that folds on itself. Amoment of time I can revisit over and over. I always wanted to learn to time bend like Yeats or Hughes.

Biginspirations include Alicia Elliott (A Mind Spread Out on the Ground)and Chelene Knight (Dear Current Occupant). (It might be time forpeople to stop saying that class divides preclude people from lyricism andintellectual pursuits).

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Alot of my writing process happens when I’m walking or doing similar kineticactivities (even driving, shout out to John Keats and negative capability!) An image appears in my mind and then mythoughts shift laterally between seemingly unassociated memories, sensoryinformation, and “school type” knowledge. A poem forms in the spaces connecting everything. The process is lightning or a dripping faucetthat stains a bathtub red over years and years.

Sometimesdeadlines motivate me to move thoughts onto the page, but generally I writeafter sequences and patterns of images have sufficiently developed.

Mydrafts are often close to the final shape, but I spend time paring downsuperfluous language and ideas. Then Igive the work a lot of room and revisit it with fresh eyes and change what Istumble over.

4- Where does a poem or work of creative non-fiction usually begin for you? Areyou an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, orare you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

WhenI was a teenager, I had a huge collage of punk rock pictures, Polaroids, andephemera all over my walls. Flyers from shows,discarded drumsticks, patches, stickers, pieces of fabric.

Ithink when I work on writing, I work in the same collage style. The work is a collection of ephemera andconcrete items associated with music duct taped to the wall.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Performancehas always been a part of my writing process, but with the amount I work latelyI don’t get to engage with readings like I used to. I think I’d like to change that in the futureand reprioritize my own writing process through readings and community.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

Fortheory, I’m looking at negative capability, lyric philosophy (Jan Zwicky),lyric inquiry (Nancy Holmes and Lorri Neilsen Glenn), scholartistry (Lorri Neilsen Glenn), poetic methods/methodologies, confession (Melissa Febos), andekphrasis. Pages could swell withtheories. Let me try brevity: whathappens when lyric expression meets memory to defamiliarize difficult and tabootopics? How can you sing domestic violence, leaning trailer houses, a tent andan abandoned station wagon in the woods?

It’sall the same well-worn grooves from William Blake’s musings on poverty inLondon to Alicia Elliott’s invocation of allusion to concretize upheaval. What’s my contribution to it all? A collection of poems that are tannins in theSuwanee River and dust on the Coquihalla.

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writersare important for process. People arecollectively forgetting process. Processis slow and creative and unending. Ithink my role is to hold onto process for myself and my poetry.

Idon’t know what the writer’s role should be ideally. I really like when Mary Ruefle writes in Madness,Rack, and Honey about taking a vase and putting it on your head and thenyou’re an upside-down flower. Maybewriters should be/do that.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Ilove it! I’m not precious about my work.

Oncemy former supervisor, Matt Rader, took a poem I was struggling with and brokethe lines into tercets. My world shiftedwith each line and new enjambment. Outside perspectives are fun and interesting. Learning how my work is perceived andreceived gives me information to incorporate into my lyrical patterns.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Thatwriting improves with time and practice. Sounds simple, but it’s helpful for me to remember that I’ll get betterthe more I read, write, and practice over and over.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to creativenon-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Idon’t view them as divided and sometimes struggle to fit my work intocategories. Maybe CNF can be dividedinto fiction-like CNF and poetry-like CNF. Maybe my CNF is just a bunch of really long prose poems. And for appeal, I suppose it’s not everyone’staste. Collages of fragmentary vignettesare lovely to me though.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Iteach a lot! Composition, critical reading and writing, literature, creativewriting, interpersonal communication. For 3 years, I commuted from Calgary to Red Deer, often waking at 4.00AM and getting back at 10.00 PM. My lifehas revolved around teaching and paying the bills as a single mother withskyrocketing costs of living. I writewhen I can: when I’m not burnt out from grading, emails, and emotionallycomplicated problems. Seems to work okayenough.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Igo for a drive, a walk, tidy up the house a bit. Then I read “The Lady of Shalott” and “Skunk Hour” and will usually be good to go.

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

Mudand palm fronds on a hot Florida day.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Punkrock, TV shows, Warren Zevon, brands of shoes, history, roadways, abandonedbuildings, philosophy, movies. You nameit.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Matt Rader, Michael V. Smith, Nancy Holmes, Margo Tamez, Suzette Mayr, Alicia Elliott, Chelene Knight, Molly Cross Blanchard, Mallory Tater, Melissa Weiss, Robert Lowell, Rosanna Deerchild, Sonia Sanchez, W.B. Yeats, Lord Tennyson, Rita Dove,Joy Harjo. I could go on, but these are very important ones.

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Seethe Grand Canyon. Go on a writing retreat where childcare is not an issue. Gainstability and permanence in my employment. Pay off my student loans. Get a Canada Council grant. Through-hike the Appalachian Trail. Re-watch Krulland maybe Ladyhawke too.

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Iused to apprentice with a lay midwife. My great grandmother was a midwife too. Maybe I would have liked to follow that path.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Writingwas easier on my body and mind. It was away out of extreme poverty.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book:Molly Cross Blanchard’s Exhibitionist

Movie:(I know it’s a part of the military industrial complex…) Top Gun: Maverick.

20- What are you currently working on?

Ahybrid CNF and poetry collection using ekphrasis to explore domestic violence.

August 23, 2024

Stephanie Austin, Something I Might Say

When I was growing up inthe 1980s, my dad was a laborer. He wore flannel shirts and trucker hats andalways smelled like sweat, cigarettes, and beer. My dad had a friend namedStan, and we would all go to Stan’s house out in the woods in rural Illinois. Thisarea was thick with trees, which seemed like a jungle, and was full of smalllakes and rivers. Stan had a dog named Ribs, or maybe Bones. Something to dowith the skeleton. He lived beside a lake edged with sand, but my sister and I werenot allowed to walk barefoot there so we wouldn’t cut our feet on broken glass.My dad and Stan drank beer and built things together. My father surroundedhimself with other alcoholics.

Stan died in a drunk-driving accident. His car slid offan icy backroad and into a tree. My mom said Dad was drunk at the funeral. He situateda six-pack of beer and a hammer in Stan’s casket, angering Stan’s sister whoasked him to leave.

“Stan liked beer,” my dad said in defence. “I wanted tosend him off with something he liked.”

I’mjust now getting into Arizona writer Stephanie Austin’s full-length debut, theprose memoir

Something I Might Say

(Santa Rosa CA: WTAW Press, 2023), a slimvolume of sleek writing packed with complicated grief. Composed as five self-containedstories or chapters, the back cover offers: “Stephanie Austin had a complicatedfather and a complicated relationship with him. His death, after a short battlewith lung cancer, forced her to reckon with his always-threatened and nowpermanent absence from her life. Then the health of her grandmother, with whomshe had always been close, began to fail, and she faced another looming loss,intensified by the bewildering early months of the pandemic.” The prose isclear, unflinching; clearly describing the turmoils and details of losing aparent and then a grandparent, back to back, while mother to a four-year-old,and all beneath the shadow of Covid-19 pandemic. All of this, of course, morecomplicated due to the difficult relationship the author had with her father. Ifound elements of parent loss and the surrounding grief entirely familiar, asmy own father died within weeks of pandemic [see my essays in the face ofuncertainties], and Austin delves deep into the details of his erosion,death and all that followed. “He tried to cut his oxygen tubing. He said heneeded to cut the tybing to breathe. I told him no, it’s the opposite. I tookthe knives from his house. I took the scissors. I drove around with his knivesand scissors in my trunk.”

I’mjust now getting into Arizona writer Stephanie Austin’s full-length debut, theprose memoir

Something I Might Say

(Santa Rosa CA: WTAW Press, 2023), a slimvolume of sleek writing packed with complicated grief. Composed as five self-containedstories or chapters, the back cover offers: “Stephanie Austin had a complicatedfather and a complicated relationship with him. His death, after a short battlewith lung cancer, forced her to reckon with his always-threatened and nowpermanent absence from her life. Then the health of her grandmother, with whomshe had always been close, began to fail, and she faced another looming loss,intensified by the bewildering early months of the pandemic.” The prose isclear, unflinching; clearly describing the turmoils and details of losing aparent and then a grandparent, back to back, while mother to a four-year-old,and all beneath the shadow of Covid-19 pandemic. All of this, of course, morecomplicated due to the difficult relationship the author had with her father. Ifound elements of parent loss and the surrounding grief entirely familiar, asmy own father died within weeks of pandemic [see my essays in the face ofuncertainties], and Austin delves deep into the details of his erosion,death and all that followed. “He tried to cut his oxygen tubing. He said heneeded to cut the tybing to breathe. I told him no, it’s the opposite. I tookthe knives from his house. I took the scissors. I drove around with his knivesand scissors in my trunk.”Thecore of the collection emerges from grief, rippling out into the specifics of acentral idea most if not all of us will engage with at some point, especially throughthe losses of a parent or grandparent. When someone close to a writer dies, onecan imagine the advice (whether external or internal) becomes the mantra of “writethrough it,” and here, Austin does, allowing for a process that might otherwisebe so much more difficult. She writes of deathbed conversations, hospice care,health care professionals and funeral homes, and how grief is impossible to compartmentalizeor contain. “After he died,” she writes, “there was no place for my bitternessabout him, about men, about life, to go. No place for my righteous sense of emotionalabandonment. My dark, awful feelings had always been directed at him, and nowhe was gone, and those feelings hovered around me like ghosts.” Not long afterher father, she writes of her Grandma Sis, and the onset of an erosion, bothsudden and slow, through dementia.

My relationship with my father had been complicated,troubled, unhappy most of the time, and now, just weeks ago, his life hadended. Grandma Sis was not ending. She was injured. I argued with my mother: itshould be me who went back to collect her.

“Why?” she asked.

“Well, you know, because I could probably make thetransition for her a little smoother.” We both knew. Grandma Sis respondedbetter to me. My mother told me to stay home: my own daughter needed me.

Austin’sprose is exploratory, capturing the essence of the chaos that surrounds attendingcare, especially while simultaneously working and parenting, and aself-awareness throughout, enough to articulate elements of surprise, such as theend of the first piece, as she cleans her late father’s house:

In his nightstand, I found a pack of cigarettes stuffedinto a sock. I laughed and held them up to my husband. “Jesus Christ,” I said. “Helived alone. Who was he hiding these from?”

August 22, 2024

OTTAWA BOOK LAUNCH: rob mclennan’s On Beauty: stories (University of Alberta Press) : Sept 25, 2024 :

Wednesday, September 25, 2024 : 7pm (opens at 6pmif you want to have dinner first,

Wednesday, September 25, 2024 : 7pm (opens at 6pmif you want to have dinner first,The Royal Oak, 1 Beechwood Avenue (upstairs),Ottawa

lovingly hosted by Rhonda Douglas,

a Q&A with the author will follow a readingfrom the collection; copies of the book (as well as copies of prior works) willbe available (cash or e-transfer); or order direct through the publisher

a Q&A with the author will follow a readingfrom the collection; copies of the book (as well as copies of prior works) willbe available (cash or e-transfer); or order direct through the publisher “rob mclennan’s On Beauty is anastonishing work of literary panache, a collection of brief, elliptical storiesthat make a virtue of their brevity, terse words carved out of the white spaceof the page, glowing with wit, startling juxtaposition, crashing sadness, andsly comedy. For each story there is an emotional core, the thing of the story,an ordinary human thing involving birth, death, marriage, and parenthood,around which mclennan elaborates swirling arabesques of language, image, andthought. Figure and ground, object and mystery. Author as a lone skater on apristine sheet of ice, unscrolling his mind. mclennan’s sentences are elegantlydramatic and precise. He is a master of the sapient aphorism, the exquisitedetail, and cascading sequences of word associations that are pure poetry. Twothings to notice especially in this regard: the stories are grounded in place(Ottawa and the Valley landscape streaming by), but there are a dozen veryshort texts all entitled “On Beauty,” together to be read as part of mclennan’sstrategy of contrasting and alternating figure and ground. The real, the human,and the Canadian are set inside the frame of beauty. Beauty insists. All thislife is beautiful, the author says.” Douglas Glover, author of Elle and SavageLove

“Though I am often mistrustful of literarynotions of Beauty, I am not being ironic when I say this book of stories OnBeauty is in fact Beautiful. It’s a beauty attributable, in part, to theauthor’s response to wide philosophical and literary readings over time, littlethreads of which wind comfortably through these almost conversational tales ofeveryday life in a city called Ottawa. rob mclennan, the critic, is also athoughtful reader of poetry. It is not surprising, then, that his sentences arewritten with the ear of a poet, forging the painful dramas and small pleasuresof the everyday lives of generations, of neighbours, in ordinary neighbourhoodcontexts, into an episodic suite that has the depth and complexity of a goodnovel. Above all, I am struck by the descriptive accuracy of the prose, the hotOttawa streets, for example, that I also remember from childhood. The detailsof a certain Scottish heritage. The portrait of a city almost empty in themiddle [save for the Parliament]. The relations of son to Mother, Father,children. On Beauty underscores once more that it takes a good reader tomake good writing.” Gail Scott, author of Furniture Music: A Northern inManhattan: Poets/Politics [2008-2012]

On Beauty is a provocativecollection of moments, confessions, overheard conversations, and memories, bothfleeting and crystalized, revolving around the small chasms and large cratersof everyday life. Situated at the crossroads of prose and poetry, these 33 vignettesexplore the rhythm, textures, and micro-moments of lives in motion. Composedwith a poet’s eye for detail and ear for rhythm, rob mclennan’s brief storiesplay with form and language, capturing the act of record-keeping while in theprocess of living those records, creating a Polaroid-like effect. Throughoutthe collection, the worlds of literature and art infuse into intimate fragmentsof the everyday. A welcome chronicle of human connection and belonging, OnBeauty will leave readers grappling with questions of how stories areproduced and passed through generations.

IF YOU CAN'T WAIT AND WANT A COPY FROM ME: the book itself is $25 + shipping ($5.40 for Canada; $12 for United States); either paypal/e-transfer to rob_mclennan (at) hotmail (dot) com

Bornin Ottawa, Canada’s glorious capital city, rob mclennan currently livesin Ottawa, where he is home full-time with the two wee girls he shares withChristine McNair. The author of more than thirty trade books of poetry, fictionand non-fiction, he won the John Newlove Poetry Award in 2010, the Council forthe Arts in Ottawa Mid-Career Award in 2014, and was longlisted for the CBCPoetry Prize in 2012 and 2017. In March, 2016, he was inducted into the VERSeOttawa Hall of Honour. His most recent titles include the poetry collection World’sEnd, (ARP Books, 2023), a suite of pandemic essays, essays in the faceof uncertainties (Mansfield Press, 2022) and the anthology groundworks:the best of the third decade of above/ground press 2013-2023 (InvisiblePublishing, 2023). The Artistic Director of VERSeFest: Ottawa’s InternationalPoetry Festival, he spent the 2007-8 academic year in Edmonton aswriter-in-residence at the University of Alberta, and regularly posts reviews,essays, interviews and other notices at robmclennan.blogspot.com

August 21, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kāyla Geitzler

Kayla Geitzler

is from Moncton, New Brunswick, whichis within Siknikt of the Mi’kma’ki. Named “A Rad Woman of Canadian Poetry”,Kayla was Moncton’s first Anglophone Poet Laureate (2019-2022). Organizer andhost of the Attic Owl Reading Series, she is also co-creator of Poésie Moncton Poetry, a video poetry archive of Mi’kmaq andMoncton area poets, and co-editor of

Cadence:Voix Feminines Female Voices

(Frog Hollow Press, 2020). Her first book

ThatLight Feeling Under Your Feet

(NeWest Press, 2018) was a Calgary Bestseller andfinalist for two poetry awards.

Kayla Geitzler

is from Moncton, New Brunswick, whichis within Siknikt of the Mi’kma’ki. Named “A Rad Woman of Canadian Poetry”,Kayla was Moncton’s first Anglophone Poet Laureate (2019-2022). Organizer andhost of the Attic Owl Reading Series, she is also co-creator of Poésie Moncton Poetry, a video poetry archive of Mi’kmaq andMoncton area poets, and co-editor of

Cadence:Voix Feminines Female Voices

(Frog Hollow Press, 2020). Her first book

ThatLight Feeling Under Your Feet

(NeWest Press, 2018) was a Calgary Bestseller andfinalist for two poetry awards.Kayla has performed her poetry withaccomplished NB musicians, the NB Youth Orchestra, and Tutta Music Orchestra. She composed, and performed, threeoriginal poems for the Tutta Musica Ovation project. Other notable collaborationsinclude CraftNB's Atlantic Vernacular and Fundy projects, and broadside with Hard Scrabble Press.

Kayla holds an MA in English,Creative Writing (UNB, Fredericton). She has worked as a technical editor on someof Canada’s largest infrastructure projects and designed courseware for AirTraffic Controllers. In 2021, she received a Top 20 Under 40 Award from theGreater Moncton Chamber of Commerce for her dedication to the literary arts.She works as an editorand writing consultant.

1 - How did your first book changeyour life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does itfeel different?

My first book, That Light FeelingUnder Your Feet, was actually my MA thesis (University of New Brunswick).It examines the two years I worked on three different cruise ships and theexploitative nature of that industry (racism, misogyny, neoimperialism, flagsof convenience). In 2016, it won the WFNB Alfred G. Bailey prize for BestUnpublished Manuscript, and NeWest Press also selected it as an inauguraledition for their CrowSaid poetry serieswhich honours poetry in vein of Robert Kroetsch. A year after its publication, Jean-PhilippeRaîche and I became Moncton's inaugural Poets Laureate (2019-2022).

As a narrative poetry collection, ittook me five years to publish; I had to rewrite it twice. My goal was to pen acollection that could be enjoyed by general readers, but anyone interested inclose reading would be able to pick out finer, theoretical points. The poemswere more a part of a whole than individual pieces.

My most recent work is stillnarrative, but I am interested in narrative's relationship with itself as wellas the page and performance, so story and form and sound. I like to experiment,and I tell a good story. I feel I have a gift to create an immersive experience.

Perhaps my recent work feelsmysterious, freer, yet more condensed. I'm interested in inheritance, incantation,and surrealism. How space and image refocus text. Many readers have told me ThatLight Feeling feels as though they are absorbed into one long story, toldin vignettes, and that it doesn't feel like poetry. A few fellow writers havetold me that my recent work has a known yet otherworldly quality, like I ambringing them through a strange yet inherently familiar place.

2 - How did you come to poetry first,as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry was my first love. My mothertaught me to read when I was two. My father read poetry to me and taught me torecite, so poetry and story have been with me since the beginning. I wroteshort fiction for about ten years and perhaps I'll return to it, or finally getaround to drafting my first novel. I also enjoy lyrical prose and the personalessay. For a time, I was a writinglife advice columnist for the Miramichi Reader.

3 - How long does it take to startany particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or isit a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape,or does your work come out of copious notes?

Good question. I believe I just startthe project and usually within the first year, something shifts the originalfocus, but not the concept. I am not a fast writer; during university I madepeace with the fact that I wouldn't be publishing a collection every two years.I'm still working on my second book, so I'll let you know how long that projecttook me when I'm done ;).

Things usually gestate for a whileand then rise to the surface when I'm ready for them (this could be days oryears). Sometimes things just come to me, suddenly, and I must write them down.

An old friend of mine says that I"puke down the page", so my first drafts rarely look like the finalversions. Depending on my subject I do sometimes write from copious notes, but Itry to trim those down, as they can distract from my original concept.

4 - Where does a poem usually beginfor you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems usually begin with an openingand ending line, or a concept that has its own rhythm or language. Typically, Iwrite longer pieces and experiment with line breaks, space and form.

Honestly, I'm not sure as I'm stillworking on my second book. I can say that overarching themes are important forme, both for structure and inspiration, but my poems are a random bestiary. So,I would say that my concepts, interests, and experiments inevitably build acollection.

5 - Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

I like to read publicly, and I loveto read with writer friends. (I run the Attic Owl Reading Series with my friendDrew Lavigne, Moncton's current Anglophone Poet Laureate.) Readings can begreat test runs for works in progress. Audiences are usually responsive to mywork, and at a reading I can hear if the poem is working—does it flow, is therhythm on-point, are my ideas carried through well, is my work connecting with theaudience? An audience will generally trust an author, so I have to be sharp indiscerning if more clarity is needed, or if something is too heavy, doesn'thave the reaction I intended, etc.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My first book looked at simulacra but I'm more interested in theoriesabout "doing things to" language. For example, Jan Zwicky's conceptof gestaltand metaphor, exploring and reinterpreting traditional styles and forms, poetry of the female grotesque, where visual art intersects withwriting etc.

I would say I am not trying to answerquestions so much as find peace, forge meaning, create a narrative aroundexperiences that have indefinable answers. In my work, I don't think there's ananswer, just a story, and I have observed that when I forge meaning, it carriesa resonance that goes far beyond me. I feel the most valuable thing we can doas writers is to connect with a reader or an audience, to move them.

Perhaps the most current questions, orconcerns, are about survival and identity, the individual and the group.

7 – What do you see the current roleof the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

In the larger culture, I would saythe writer's role is awareness, and art. The value of both is often in questionand undervalued. When I make school visits, I tell students that writing hasvalue, that we, as writers, create culture, report on injustice, and we canchange how people think and act.

Some writers feel they have a roleand others do not want one. I feel thatquestion is different for every genre and author. And the idea of a role, Ithink, goes back to who is seen and heard, and why? Perhaps the role of awriter is wonder. And from wonder, equality, equity and justice. Also art. Manyof us write because we love to, and writing, in many ways, heals us, frees us.

8 - Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I am an editor, but I don't have aneditor. I prefer to mentor with a more experienced poet, such as Anne Simpson,or take workshops with skilled writers. I do, however, belong to a ratherexceptional writing group. Their feedback plays an essential role in my work.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Max Ehrmann’s "Desiderata."

10 - What kind of writing routine doyou tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you)begin?

My writing routine has never been a disciplinedpractice; I prefer to sit down and write when the piece comes. When the ideathat has been gestating inside me seems to find its words and bubbles up. But whatworks best for me now is to write in the morning when I am fresh, and edit atnight.

11 - When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I usually have to leave the piecealone for about three weeks and then return to it when I've "forgotten"it. Then, it can usually speak clearly to me from the page, without meoverthinking it.

12 - What fragrance reminds you ofhome?

Wild roses and cold Atlantic wind.

13 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

For me, poetry distills life,distills a life, and therefore is not a one-dimensional expression either. Ilove ideas and experimenting, asking "what if..." and "whatwould that look like or sound like if..." which includes folding imageryand documents into my poetry. I have a busy mind, so many things interest meand can influence my work—language, culture, archiving, nature, sound, science,history, philosophy, theory, music and visual art all have their unique role inwhatever piece I'm working on at the moment.

14 - What other writers or writingsare important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Forugh Farrokhzad, Kim Hyesoon, AnneSimpson, Khaled Khalifa, Elena Ferrante, Safia Elhillo, Zeina Hashem Beck,Layli Long Soldier, Sei Shonagon, Ocean Vuong, Jake Skeets, Alden Nowlan, Emily St. John Mandel, Mahmoud Darwish, the Brontës, Tanith Lee. My friends' writing,too, which is at various stages of publication: Shoshanna Wingate, Elizabeth Blanchard, Drew Lavigne, Margo Wheaton, Judy Bowman, Nancy King Schofield,Carol Steel, Rose Després, Jean-Philippe Raîche.

15 - What would you like to do thatyou haven't yet done?

Swim (respectfully) with wildcreatures. Travel Central Asia. Start an affordable writing retreat. Write afew novels.

16 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Psychology in some form, most likelywhere it intersects with criminology. Forensic psychology and behavioural analysisfascinate me. Or art conversation/restoration.

17 - What made you write, as opposedto doing something else?

I was five years old when I told myfamily I wanted to be a writer. Even then it felt like a vocation. While I haveworked various jobs, the past five years of my life working as an editor andwriting consultant, and as Moncton's first Anglophone Poet Laureate, have beenthe most fulfilling of my life. There is a draw in my life that has returnedme, again and again, to writing.

18 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

It's a tie: My Brilliant Friend byElena Ferrante and In Praise of Hatred by Khaled Khalifa.

Solaris (1972), based on the book by StanislawLem, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, starring Natalya Bondarchuk and DonatasBanionis.

19 - What are you currently workingon?

I'm working on my second poetrycollection and two chapbooks.

My second book looks at how familiesmythologize themselves, what stories they tell, what was "forgotten"and recovered, historical influence, what is inherited (in many forms, such as predisposedillness, mental illness), and how we are, or are not, nurtured.

One chapbook examines femalerelationships and the deconstruction of dominate European patriarchalnarratives (in literature and history) through a queer diasporic protagonist asshe travels Europe and Canada.

The last chapbook project, which maybe amalgamated into the second poetry collection, examines the sudden death anddifficult life of my late mother.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

August 20, 2024

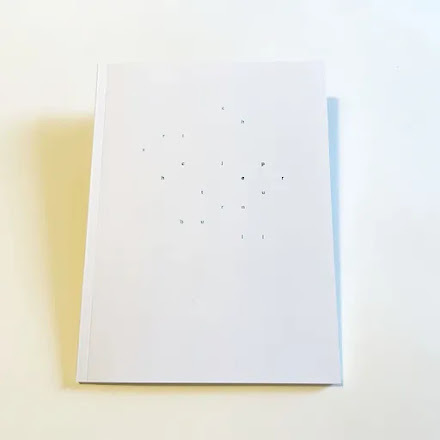

Chris Turnbull, cipher

the lake,

remnant, scar, is shallow

swings

toward edge-not.

kinetics of form

– ebb-terrain –

includes

the sodden

the parched

the reminiscent(“candid”)

Thelatest by Kemptville, Ontario poet and curator Chris Turnbull is

cipher

(Toronto ON: Beautiful Outlaw Press, 2024), a book of listening and attention;of being present, and outdoors. Set as a triptych of suites—“candid,”“contrite” and “ciper”—Turnbull extends her note-taking across a slowness,writing moments and local through a book of ecological space. “in now, when,then –,” she writes, as part of the first section, “compression – generated – /for this / instant-on-instant, [.]” Compression is a perfect word to describeTurnbull’s poem-structures, a kind of book-length accumulation of note-takingthat exists amid the tensions of compression and expansion. Across the length andbreadth of the book as compositional space, Turnbull composes short bursts oflyric that stretch out across a wide canvas, compelling and attending anecopoetic of minutae and magnitude. “littoral zone – hundreds / list,” shewrites, as part of the first section, “founder – dark reshaping clusters – /// easy/ does it /// these domains / are fluid [.]” She writes of unsafe roads, ice onthe river and bees messaging, a poem composed from and within a landscape, elementsof which echo her ongoing rout/e, her project of placing poems along rural walking trails, and watching across time as the words fade and pages decompose’;a project, by itself, which echoes Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott’s collaborativeDecomp (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2013) [see my review via Arc Poetry Magazine here]. Across cipher,Turnbull’s words hold, erode, corrode, and slip into soil. There is an element,also, that echoes Lorine Niedecker’s “Lake Superior,” although, unlike Niedecker’sinfamous poem that emerged as an extension of work-related research, Turnbull’slyric exists as both research and reportage: these poems are simultaneous studyand result, and of something ongoing, deeply intuitive and regularly attended. AsTurnbull speaks to the project in a recent interview conducted by Conyer Claytonfor periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics:

Thelatest by Kemptville, Ontario poet and curator Chris Turnbull is

cipher

(Toronto ON: Beautiful Outlaw Press, 2024), a book of listening and attention;of being present, and outdoors. Set as a triptych of suites—“candid,”“contrite” and “ciper”—Turnbull extends her note-taking across a slowness,writing moments and local through a book of ecological space. “in now, when,then –,” she writes, as part of the first section, “compression – generated – /for this / instant-on-instant, [.]” Compression is a perfect word to describeTurnbull’s poem-structures, a kind of book-length accumulation of note-takingthat exists amid the tensions of compression and expansion. Across the length andbreadth of the book as compositional space, Turnbull composes short bursts oflyric that stretch out across a wide canvas, compelling and attending anecopoetic of minutae and magnitude. “littoral zone – hundreds / list,” shewrites, as part of the first section, “founder – dark reshaping clusters – /// easy/ does it /// these domains / are fluid [.]” She writes of unsafe roads, ice onthe river and bees messaging, a poem composed from and within a landscape, elementsof which echo her ongoing rout/e, her project of placing poems along rural walking trails, and watching across time as the words fade and pages decompose’;a project, by itself, which echoes Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott’s collaborativeDecomp (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2013) [see my review via Arc Poetry Magazine here]. Across cipher,Turnbull’s words hold, erode, corrode, and slip into soil. There is an element,also, that echoes Lorine Niedecker’s “Lake Superior,” although, unlike Niedecker’sinfamous poem that emerged as an extension of work-related research, Turnbull’slyric exists as both research and reportage: these poems are simultaneous studyand result, and of something ongoing, deeply intuitive and regularly attended. AsTurnbull speaks to the project in a recent interview conducted by Conyer Claytonfor periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics:I’ve been working slowly on this manuscript forseveral years — and over this period considering seeming societal withdrawals‘from’ the outdoors. I wonder how other generations might mediate theirexperiences of, or limit fears of, various elements of our physical worlds. Ithink this conundrum is important — there is no conclusion, but cipher presentspossibilities. How do these generations relate to or make world(s)? Land doesnot take precedence, screens, networks, are central and unbound: the marsh is rippedat corner.