Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 340

July 3, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Virginia Konchan

Author of

Vox Populi

(Finishing Line Press), and a collection of short stories, Anatomical Gift (forthcoming, Noctuary Press),

Virginia Konchan’s

creative work has appeared in The New Yorker, Best New Poets, Boston Review, The Believer, StoryQuarterly, and The New Republic. Co-founder of

Matter

, a journal of poetry and political commentary, she lives in Montreal.

Author of

Vox Populi

(Finishing Line Press), and a collection of short stories, Anatomical Gift (forthcoming, Noctuary Press),

Virginia Konchan’s

creative work has appeared in The New Yorker, Best New Poets, Boston Review, The Believer, StoryQuarterly, and The New Republic. Co-founder of

Matter

, a journal of poetry and political commentary, she lives in Montreal.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook, Vox Populi, came out in 2015, and my first book of short fiction is forthcoming in 2017. I wouldn’t say having a chapbook out has changed my life drastically. It was great to give a few readings from the chapbook rather than my usual folder of poems. I’m writing fewer ekphrastic and persona poems, and more sonnets; my most recently poems are based on tropes of blindness and memory. Recent fiction investigates virtual reality and how characters negotiate the relationship between aspects of her spiritual and secular lives. And the novel I’m working on is a madcap feminist bildungsroman, a form apart from the rest.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I have written poetry and fiction in tandem since undergrad. I think I was first drawn to poetry over fiction because of metaphoric thinking; then I realized how to extend metaphors in prose.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Charles D'Ambrosio says it best: “Instead of sobbing, you write sentences.” I love that idea, of metrical form or discipline to a form as a way to order the emotional life. As far as genesis goes, guiding images or tropes come immediately, but the piece itself is birthed line by line, sentence by sentence, in increasingly slower drafts. I used to write drafts of poems that were close to what was eventually published. Now, in both genres, my process is much more labored and deliberate. I think carefully about the effect my work has on a reader.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

An image, a word, a sentence or line of overheard/found language, or an adopted persona. I now think of my work in terms of book projects.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy giving readings, but I like reading new material, and that’s not always possible. I’m reading this April in Toronto, and plan to read experimental prose, instead of poetry. I tend to get more excited about readings when I know I have the option to subvert expectations, even if they’re just my own.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The short answer is yes. It’s often the critic or reader that decides what those theoretical concerns are, but if those questions or preoccupations are shared by the writer, all the better.

My chapbook was described by Jill Magi as “Marxism singing a joyful song.” Moving to Canada in 2014, and graduating from a Ph.D. program in 2015 has put what was a few years ago some very abstract ideas about socialism and critical theory into lived praxis, for sure. Much of the critical writing I did for my Ph.D., and in reviews and essays about capitalism, commodification, and cultural theory, has been set into high relief upon moving to a socialist country, and graduating from a theory-centric program (The University of Illinois at Chicago).

The main questions I’m trying to answer now with my fiction, and to an extent my poetry, is how to remain a conscious participant in any political system or aesthetic form, resisting modes of hypnosis, even lyric hypnosis, and bandwagoning. How can the move toward the social, the repeated decentering of the I, in the lyric, still work in concert with a notion of aesthetic responsibility? If traditional modes of lyric address (apostrophe, I/Thou), are obsolete, how should we think of or configure our audience? Why are the acts of of cognition and music-making be opposed in poetry, when in fact poetry can be the highest form of musical thinking?

With fiction and poetry, the questions of audience, of consciousness, of intentionality, of art as a legitimate (though hopefully not self-legitimizing) form of epistemology are ever-important. But today, more than ever, the question of how to live in the information age, while remaining users rather than pawns of technology and social media is also crucial. And also, in brief, the question of the textual vs. digital archive. Questions of performativity (whether of gender, race, ethnicity or sexuality); questions of performance vs. text-based art forms. Questions of postcolonial theory and ecocriticism. And lastly, a lot of my work—poetry and prose—is concerned with animal ontology—animals as the ultimate other. What is our responsibility, as artists, or just as humans, in an age of industrial slaughterhouses, mass extinctions, and eco-devastation: what Gabriel Gudding calls “an apocalypse that cannot be seen”? I don’t have the answer. But I think this is a hugely important question or set of questions that strikes at the heart of what it means to think about survival, stewardship, otherness and compassion in the post-anthropocene.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To prescribe a role for a writer can be dangerous. Shoulds and Oughts are rightfully the domain of philosophers like Immanuel Kant. Having said that, I think E.B. White says it best: “I feel no obligation to deal with politics. I do feel a responsibility to society because of going into print: a writer has the duty to be good, not lousy; true, not false; lively, not dull; accurate, not full of error . . . Writers do not merely reflect and interpret life, they inform and shape life.” To that I’d add that writers have a responsibility to respond to the zeitgeist and help create it, by writing works that give structure to this historical moment, and beyond that, to challenge and question the status quo and given (political, aesthetic, cultural) forms.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both.

Cutting back is the easiest; it’s more difficult to reenter the work and try to graft on a different perspective. The conversations that ensue can be productive, but the work can also suffer from the attempts to please or to entertain multiple POV’s. Still: essential, and necessary.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Most recently: “Don’t be afraid to write a grubby first draft,” and “Plot and structure are your friends,” from Vermont Studio Center visiting writer David Gilbert (February 2016).

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to short fiction to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

Relatively easy, all things considered, though I believe each genre suffers individually from my inability to focus on just one for a long period of time. The appeal is the overlap, between the short story and the long poem, the flash fiction and the prose poem, the lyric essay and others genres of narrative non-fiction. It’s knowing within ten minutes of beginning something that it wants to be, or will eventually be, a story versus a poem. As Stuart Dybek, an equally brilliant poet and fiction writer, says, the abstract definitions of a genre (or genre distinctions themselves) are less interesting than whether the piece moves you and takes you somewhere interesting.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I get up at 7:30, have coffee, meditate, and try to write for two hours before my work day begins. I usually save the evenings for reading or emails. On the weekends, it varies.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Reading. Running. Yoga. Travel. My cats. My friends.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Dryer sheets.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Pina Bausch and contemporary dance, painting, photography, physics. Artists Louise Bourgeois, Imogen Cunningham, David LaChapelle, Dana Schutz, Barbara Hammer. And, yes, music. Today I am listening to cellist Truls Mørk and editing a few sonnets.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Hmm. I’ll stick with writers. Calvino, Borges, Beckett, Kafka, Flaubert, Cheever, Henry James, the Brontës, Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, Elizabeth Bowen . . . Rebecca Solnit, Lydia Davis, Rosalind Krauss, Marguerite Duras, Maggie Nelson, Jill Magi, Bhanu Kapil, Kate Zambreno. As for poets, Shakespeare, Keats, Dickinson, Mina Loy, Wallace Stevens. Sylvia Plath, John Berryman, Alice Notley, Matthea Harvey, Lucie Brock-Broido, Jorie Graham, Louise Glück, Charles Wright. Carolyn Forché, Brenda Hillman, Michael Palmer, Susan Stewart, C.D. Wright, Geoffrey G. O’Brien, Timothy Donnelly, Claudia Keelan. So many others, especially contemporary writers.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Start my own business, and publish a novel.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A Jungian psychoanalyst.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Natural inclination + passion.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Sphinx by Anne Garréta (trans. Emma Ramadan), and John Cassavetes’ Gloria.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Final edits on my novel, Camelot, second short story collection, Midas Touch. And two poetry manuscripts, one all-but-done, and the other in process.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 03, 2016 05:31

July 2, 2016

The Hardest Thing About Being A Writer : rob mclennan,

In case you didn't see:

I answered some (two) of Sachiko Murakami's questions for her "The Hardest Thing About Being A Writer" series

; I complain a bit more than I usually do (in print, anyway), and perhaps a bit less than she might have hoped.

In case you didn't see:

I answered some (two) of Sachiko Murakami's questions for her "The Hardest Thing About Being A Writer" series

; I complain a bit more than I usually do (in print, anyway), and perhaps a bit less than she might have hoped.Other writers interviewed in the same series (so far) include Nikki Reimer, Laura Broadbent, Anita Anand, Sarah Yi-Mei Tsiang, Vivek Shraya and Daniel Zomparelli.

And, of course, I've already added the link to my ongoing list of interviews with me that have been posted online: see?

Published on July 02, 2016 05:31

July 1, 2016

Ongoing notes: Canada Day, 2016

Happy Canada Day! I’m behind on everything, as you might imagine.

Happy Canada Day! I’m behind on everything, as you might imagine.I’m attempting to be less behind on some of these reviews (again). I’ve yet to start going through the material I picked up at the most recent ottawa small press book fair, but hope to be getting into that soon. Otherwise, are you checking out the activity on some of my other blogs, whether the ottawa poetry newsletter , above/ground press, Chaudiere Books or the “Tuesday poem” series over at the dusie blog?

I think we’re going somewhere for brunch today. Not sure yet. Maybe something else as well.

It only takes us an hour, these days, to leave the house at all…

Brooklyn NY: I’m quite taken by New York City poet and doctor Jennifer Stella’s debut poetry collection, Your lapidarium feels wrought. (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2016), a small suite of erasure poems, all of which share the same title. Who is this Jennifer Stella? Her line and breath breaks are stunning, staggering and staccato-precise. I want more.

Your lapidarium feels wrought

After bus to plane to train to bus, street sweeping dictates horse-like machines. It’s much colder in Colorado. Typhoons are only signs, but curbsare hydrant glass. Once I am driving, I

drive. The Pacificis far from momentum, my Pacific is so close

Philadelphia PA: I like the twenty-six poems that make up Laura Theobald’s odd edna poems , produced (undated) in an edition of one hundred copies by Gina Myers’ Lame House Press.

XI

edna read a book by mark twain. “i will never be a book,” she said.

edna looked in the mirror. all twelve of her eyes blinked.

The poems, titled via Roman numerals, exist as self-contained moments that, as they progress, give a sense of movement, almost as a flip-book constructed out of poems (instead of images).

XIV

edna couldn’t decide whether to be a princess or a scoundrel. “if i was a scoundrel,” edna thought, “i could ride a raft downriver. if i was a princess, ii could ride the back of a horse.”

“i wish i was the elephant man,” she said.

edna rode a raft down the river in her mind for 15 yrs. it was a lot like driving.

when edna woke there was nothing left. her sheets were blue like a river and she thanked god. “god,” she said. “for the sheets.” there were screams coming from all around her but she didn’t know why.

Published on July 01, 2016 05:31

June 30, 2016

Today would have been my mother's seventy-sixth birthday,

Published on June 30, 2016 05:31

June 29, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Richard Kelly Kemick

Richard Kelly Kemick's

poetry, prose, and criticism have been published in literary magazines and journals across Canada and the United States, most recently in

The Walrus

,

Maisonneuve

, and The Fiddlehead. His debut collection of poetry,

Caribou Run

, was published March 2016 by Goose Lane Editions.

Richard Kelly Kemick's

poetry, prose, and criticism have been published in literary magazines and journals across Canada and the United States, most recently in

The Walrus

,

Maisonneuve

, and The Fiddlehead. His debut collection of poetry,

Caribou Run

, was published March 2016 by Goose Lane Editions.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

That’s a bit of a tricky question because I’m writing this (March 25th) four days before my first book, Caribou Run, comes out (March 29th). As of right now, the largest change in my life is my mother passing around one of my advanced copies at her dinner parties and making me watch horrified as people take their perfunctory flip through, nod encouragingly, and unload it to the next person.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I looked at the trajectories of my favourite writers (Ondaatje, for example) and so many of them seemed to start with poetry. The precision of language that poetry so loudly demands is what I think made their novels, short stories, essays of such a high calibre. Their language is poetic––though not just in a “look at the pretty flower simile” sense but that they have a sixth sense for knowing where which word will do the most damage.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It doesn’t take me too long to start a project; usually I will have started one before I realize I’ve done so. And it doesn’t take me an inordinate of time to finish a complete draft of the project either. What takes me the most time is editing. Often times, I don’t fully know what themes I am writing about until after I’ve finished; then, I go back through several times and make sure I’m drawing those themes out. It’s a lot of taking a word out, putting a word in, taking that word out, putting the first one back in, taking the whole sentence out, and then openly weeping.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I’d thought about Caribou Run as a project: a collection about the caribou migration from start to finish. I then started filling in each section with poems that I felt fitting. This was absolute torture (try writing a villanelle about caribou rutting) and am looking forward to living the rest of my life never doing this again.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I used to enjoy reading my work a lot more––when I wasn’t so dreadfully self-conscious about everything I wrote. I do, however, still think that readings are good for me to not just for crowd-test my work but to ensure I don’t become that god-awful cliché of a poet in his single bedroom walk-up, writing by candlelight, letting his toenails grow lavishly long.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I get hesitant when it comes to having my poems answer “Big Picture” questions. Any attempt to do that always makes my work seem didactic and simple. I try to just write as honestly and clearly as I can;if the reader happens to connect those ideas to larger issues, then I allow myself a fleeting moment of fulfillment.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

This is a question I actively avoid since that way madness lies. My father’s a cabinetmaker and I not sure how much time he spends each day, leaning up against the miter saw, and thinking, “What is the role of the cabinetmaker in larger culture?” I think the role of the writer is to write.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both. Much to my delight, Don McKay edited Caribou Run; I sometimes found the process difficult (but always found him delightful) because poems I’d been sitting with for years were now being asked to change. I often found myself saying, “But that’s not how this poem goes!” But now that the project is finished, I can firmly say that an outside editor was a godsend.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

You can tell a simple story in a complex way, or you can tell a complex story in a simple way; but you can’t tell a simple story in a simple way or you’re an idiot, and you can’t tell a complex story in a complex way or you’re a bigger idiot.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

For me, the appeal is in the honeymoon period of working within a new genre. The rules are different, the style is different, the audience is different. When that genre’s flame begins to dwindle, I approach a new genre with all the lessons I’ve learned from working in the former. And yes, in that sense, all my writing is in the early stages of an entropic heat death.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don’t really have a daily routine; sometimes I write in the morning, sometimes in the evening. As long as I’m writing each day, I’m content.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I usually turn to a piece of writing in the same genre I’m working. Or I take the dog for a walk. Or I stare out the window and question every single choice I’ve made in my life.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Sawdust.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Over the past few years, I have been in a war of attrition with bilingualism. I have found, however, that French has helped me gain a bird’s-eye view of the English language. This view has helped me see even basic concepts such as grammar and sentence structure in a new and refreshing light.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Anything by the aforementioned Ondaatje. Amy Hempel. Don McKay. Shakespeare. Eliot. Heart of Darkness. God, this list sounds like I’m writing an admissions essay.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Live forever.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Veterinarian. And I’d published one collection of linked short-stories about living in another specie’s skin and it would be the most poignant book ever written.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I tried hockey but was shitty at it. I worked at Blockbuster for a bit and we all know how that ended. Waiting tables was difficult because there’s only so long you can hand people food which you yourself could never afford. I don’t think I could hack it in veterinarian school.

My mother always said I could do whatever I wanted. I’m putting that theory to the test.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Ishiguro’s Remains of the Day.

Film: Is House of Cards considered a film if I watched the last season in a single sitting?

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a collection of creative non-fiction essays. With any luck, my marriage will survive.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on June 29, 2016 05:31

June 28, 2016

Barking & Biting: The Poetry of Sina Queyras, selected with an introduction by Erin Wunker

Thus far, twenty-first-century poetics has been preoccupied with two ongoing conversations: the perceived divide between lyric and conceptual writing, and the underrepresentation of women and other nondominant subjects. While these two topics may seem epistemologically and ethically separate, they are in fact irrevocably intertwined. Questions of form are, at their root, questions of visibility and recognizability. Will the reader know a poem when she sees it? And will that seeing alter her perception of the world? And how is the form of the poem altered, productively or un-, by the identity politics of its author? (Erin Wunker, “Of Genre, Gender, and Genealogy: The Poetry of Sina Queyras”)

Barking & Biting: The Poetry of Sina Queyras, selected with an introduction by Erin Wunker (Waterloo ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016) is the latest ‘critical selected’ in the Laurier Poetry Series, a series now over a decade old and more than two dozen titles deep. Barking & Biting: The Poetry of Sina Queyras includes selections from Queyras’ five published poetry collections— Slip (Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2001), Teethmarks (Gibson BC: Nightwood, Editions, 2004), Lemon Hound (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2006), Expressway (Coach House Books, 2009) and M x T (Coach House Books, 2014) [see my review of such here]—leaning far heavier on the more recent collections and less on the earlier books.

The future at a hundred miles an hour, mouths stretched like windsocks. I hate your seamless layers, you know that, but you scratch by, and I am thinking of all the Trojan horses this bay has seen, eleven of them now, bobbing in the harbour, containing who knows what army of product.

Unbelievable views, never did take them for granted. There is a spot just outside the pillar and glass where, when you stand in the pea gravel and whisper to me, standing where I am standing by the totem at the edge of the continent, we can hear all the dead ones singing. (“‘Water, Water Everywhere’”)

The poems that make up Barking & Biting: The Poetry of Sina Queyras show outspoken Montreal-based poet and critic Queyras—author, as well, of a collection of critical prose, Unleashed (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2010) and the novel

Autobiography of Childhood

(Coach House, 2011)—to be deeply engaged with a poetics in constant flux, and one that works to engage with identity politics, as well as the divide (both real and imaginary) that exists between lyric and conceptual writing. Her writing has long been known for both a pervasive restlessness and an engaged ferocity, and one that has little patience for half-measures. Queyras engages Sappho, Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein in the same breath as she might also speak of Mary Oliver, Lisa Robertson and Vanessa Place, and the breadth of her view somehow manages only to focus her attention. As critic and editor Wunker writes in her introduction: “Queyras’s poetics pay dogged attention to questions of both representation and genre. In each of the collections of poetry she inhabits tenets of the traditional lyric, while also leveraging the genre open and letting conceptual in.”

The poems that make up Barking & Biting: The Poetry of Sina Queyras show outspoken Montreal-based poet and critic Queyras—author, as well, of a collection of critical prose, Unleashed (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2010) and the novel

Autobiography of Childhood

(Coach House, 2011)—to be deeply engaged with a poetics in constant flux, and one that works to engage with identity politics, as well as the divide (both real and imaginary) that exists between lyric and conceptual writing. Her writing has long been known for both a pervasive restlessness and an engaged ferocity, and one that has little patience for half-measures. Queyras engages Sappho, Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein in the same breath as she might also speak of Mary Oliver, Lisa Robertson and Vanessa Place, and the breadth of her view somehow manages only to focus her attention. As critic and editor Wunker writes in her introduction: “Queyras’s poetics pay dogged attention to questions of both representation and genre. In each of the collections of poetry she inhabits tenets of the traditional lyric, while also leveraging the genre open and letting conceptual in.”One of the benefits of such a collection, even by those already familiar with Queyras’ work, is in the reminder of just how powerful her writing is, pushing to constantly challenge boundaries, margins and safeties. If you read nothing else, be aware that the longer poem-essay “‘Water, Water Everywhere’” is perhaps the finest example of everything Queyras is doing and has done, all set in the space of a few short pages, writing:

I read Mary Oliver’s poem about angels dancing on the tip of a pin and I kept thinking, She is writing about a penis, Mary Oliver is really a gay man and everything is about AIDS, which made me want to carry Mary Oliver in my pocket.

I could think of no finer way to close such a collection than Queyras’ “Lyric Conceptualism, A Manifesto in Progress” (interestingly enough, Queyras is not the first poet in the series to close their collection with a piece more in the shape of a poem than straight prose), reinforcing the notion that hers is a poetics that continually adapts and re-thinks, refusing the fixed point, and willing to constantly be learning. The idea is reminiscent of Jay MillAr, who, after the appearance of his anthology Pissing Ice: an anthology of new Canadian poets (Toronto ON BookThug, 2004), an anthology constructed in part as a more experimental/avant-garde response to some of the more formally-conservative anthologies of Canadian poetry that were appearing around that time, resisted composing a fixed introduction or “poetics.” One can’t set down, easily, if at all, a moving target. As Queyras writes in her end-piece:

Lyric Conceptualism is a poetics of the sentence, but it does not turn its back on the relationship between words, nor the power of prosody, nor the possibility of lyric propulsion. On the other hand, nor does Lyric Conceptualism shy away from the knotted and the complex.

Lyric Conceptualism imagines herself a boat, fluid, without handles, able to slip through definitions, anchor at will.

Lyric Conceptualism is interested in achieving the sculptural.

Published on June 28, 2016 05:31

June 27, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ben Parker

Ben Parker's debut pamphlet,

The Escape Artists

, was published by tall-lighthouse in 2012 and shortlisted for the 2013 Michael Marks Award. He spent a year as Poet-in-Residence at The Museum of Royal Worcester, which culminated in the publication of From the Porcelain a pamphlet of work produced. He is currently Poet-in-Residence at The Swan Theatre, Worcester and poetry editor of

Critical Survey

. His debut collection, Insomnia Postcards, is due from Eyewear Publishing on October 6th. www.benparkerpoetry.co.uk

Ben Parker's debut pamphlet,

The Escape Artists

, was published by tall-lighthouse in 2012 and shortlisted for the 2013 Michael Marks Award. He spent a year as Poet-in-Residence at The Museum of Royal Worcester, which culminated in the publication of From the Porcelain a pamphlet of work produced. He is currently Poet-in-Residence at The Swan Theatre, Worcester and poetry editor of

Critical Survey

. His debut collection, Insomnia Postcards, is due from Eyewear Publishing on October 6th. www.benparkerpoetry.co.uk1 - How did your first chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I don’t know if I would say it changed my life exactly, but it certainly opened up some new opportunities. I was able to read at some venues I might not have previously, and I was able to use it as a sort of proof-of-ability when becoming a writer in residence.

My hope is that my recent work is basically a better version of my previous work. I think at the moment that any changes are small ones. Every so often I will try and write in a way that is radically different, and I usually manage this for a few poems, but end up going back to something more recognizably like my old style, though perhaps having learnt something along the way.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I can pin-point it exactly. I was 21, and after overhearing a conversation about Sylvia Plath, specifically her reading style, I decided to check it out online. Up to that point I had zero interest in poetry, and pretty much thought it wasn’t for me. But hearing Plath reading, specifically her poem ‘Daddy’, switched something on in me. After that I read her Collected Poems and realized that poetry contained everything I wanted from writing, and I haven’t stopped reading it since.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I think on the whole I write pretty quickly, and it is very rare that I work from notes. The poems of mine that I like best are the ones that arrive almost complete. There is always some editing to do, and this can go on for months after the poem was written, but I tend to feel the poems I’ve had to hammer in to shape have a forced quality.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Poems can begin anywhere, and I often find it hard to pin down the exact catalyst for any given piece. I’m very much an author of short pieces, both in the sense that most of my poems don’t exceed one page, and in that I think of them as standing alone, rather than as part of a larger book. I try not to worry about how any given poem I’m writing will fit with other poems I’ve written.

That said, Insomnia Postcards, the book due out with Eyewear later this year, has as its backbone the eponymous title sequence. These 10-line poems are spread throughout the book, and hopefully hold together the disparate other pieces that make up the majority of the collection.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I think they do play a small part in the creative, specifically the editorial, process. When I give public readings I tend to practice quite a lot before hand, which forces me to go back to poems I had thought of as completed. Reading them out loud multiple times often reveals a line that doesn’t work, or something I’m not happy with, at which point I have to re-type the poem and start the process over again.

It has taken a few years, but I am becoming more relaxed about giving readings. I still tend to enjoy them more retrospectively, rather than in the moment.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’t think that I do have any theoretical concerns really, I just try to write the poems that I myself would like to read.

I suppose the question a lot of my poems try to answer is “what if...?”

If I had to guess, I would say the current questions for most people are the same as the old questions, with “what does it mean to be human” being one of the favourites. I suspect we will never have an answer, and that’s why we can keep asking it.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think this depends on the writer. I don’t feel comfortable claiming that ‘writers’ in an abstract sense have any particular role. Some writers are trying to entertain, some to educate, some to incite change. I think there is space for all these roles, and many others.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I have found the process positive on the occasions when I have worked with outside editors, and I think I’m pretty open to suggestions. The poems have definitely benefited from having a critical eye cast over them.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I don’t think you can do much better than Picasso’s “inspiration exists but it has to find you working”. Certainly for me, the inspiration for a lot of my poems seems to arrive the way a cartoon character might lay down tracks in front of a moving train.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I try to write every morning, with a coffee, before doing anything else. This is the only planned writing time that I have, but if a particular impulse drives me then I will write afternoon/evening/whenever. I would say that 90% of my poems were written at my desk in the morning.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Whoever I’m currently reading normally does the trick. My favourite poet is usually the one whose book I have open in front of me, if it wasn’t I would probably stop reading them, and at that point I think all my poems would be better if they sounded more like theirs.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

My mum cooks an excellent curry every Friday night, so I guess the fragrance of Indian spices is a smell I associate with home.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yes, definitely. I don’t feel that there is one particular area that influences me, but outside of poetry popular science is probably what I read more than anything else. There are certainly a few poems in Insomnia Postcards that use some aspect of science as jumping off point. Also tv and film are very important to me.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I could list a dozen poets today, and it might be a different dozen tomorrow. However, outside of poetry William Burroughs is the author I return to most often. I read him first when I was 18 and I return to his work frequently.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

There are lots of great UK poetry festivals that I’d love to read it at, so hopefully once I’ve got another book or two under my belt I might start getting some calls.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Well, poetry isn’t exactly my occupation anyway, I work in marketing for a publishing firm. But aside from poetry, my other main activity is climbing, mainly indoors because there isn’t much rock around Stratford-upon-Avon. I guess if I spent less time reading and writing poetry, my next choice would be spending that time climbing.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It’s hard to say where the impulse to write came from, it just felt like something I’d like to do. I’d tried to do other things but I never stuck at them. I’ve never struggled to stick with poetry.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I spent a lot of last year reading Christopher Middleton’s Collected Poems, whose work I think deserves far more recognition than it has. In film, Calvary and Ex Machina are the ones I have raved most about recently.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Putting the finishing touches to Insomnia Postcards, writing poems for the Swan Theatre residency and also producing some new work along the way.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on June 27, 2016 05:31

June 26, 2016

Today is my father's seventy-fifth birthday,

Published on June 26, 2016 05:31

June 25, 2016

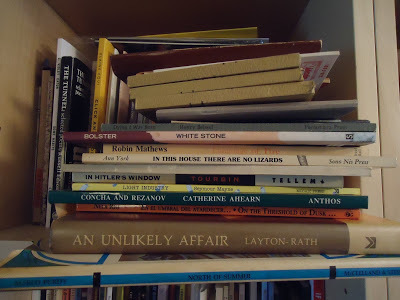

Dismantling Jane Jordan's Library : Open Book: Ontario

My short essay,

"Dismantling Jane Jordan's library," is now online at Open Book: Ontario

, composed as a continuation of an earlier piece I posted, here.

My short essay,

"Dismantling Jane Jordan's library," is now online at Open Book: Ontario

, composed as a continuation of an earlier piece I posted, here.

Published on June 25, 2016 05:31

June 24, 2016

U of Alberta writers-in-residence interviews: Erín Moure (2013-14)

For the sake of the fortieth anniversary of the writer-in-residence program (the longest lasting of its kind in Canada) at the University of Alberta, I have taken it upon myself to interview as many former University of Alberta writers-in-residence as possible [see the ongoing list of writers here]. Seethe link to the entire series of interviews (updating weekly) here.

Erín Moure by the North Saskatchewan River in Edmonton. Photo by Karis Shearer.

Erín Moure by the North Saskatchewan River in Edmonton. Photo by Karis Shearer.Erín Moure is a poet and translator of poetry from French, Spanish, Galician and Portuguese. Her work has received the Governor General's Award, Pat Lowther Memorial Award, and A.M. Klein Prize (twice) and been a three-time finalist for the Griffin Prize. Her Insecession, a biopoetics echoing Chus Pato, appeared in one book with Pato’s Secession, in Moure translation(BookThug, 2014). Her French/English play-poem Kapusta (Anansi, 2015), sequel to The Unmemntioable , was a finalist for the A.M. Klein Prize and was a CBC Best Book of 2015. 2016 will see three new Moure translations from Galician and French: Flesh of Leviathan by Chus Pato (Omnidawn), New Leavesby Rosalía de Castro (Small Stations), and My Dinosaur by François Turcot (BookThug).

Shewas writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 2013-14 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you’d been publishing books for more than three decades. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: For me writing is always starting anew, as a beginner. Language always asks me to begin again. I don’t want to do what I did before.

I went to Edmonton very excited about spending time in English, and having time free of freelance work slogging (which largely conspires to make creative life impossible) to complete one poetic project (Kapusta, appeared from Anansi in 2015) of my own, and do a very complex and long translation of Brazilian Wilson Bueno’s work in Portunhol with Guaraní into English flecked with French and, I had hoped, Tsuu T’ina or another indigenous language of Alberta… that didn’t work out, and I decided to keep the Guaraní… but I did finish the translation and start trying to find a publisher. It will be out in the second half of 2017 from a US poetry press, but I won’t name it as I haven’t received the executed contract. I also wanted to spend those months with my father, whom I knew was near the end of his days and was in a seniors residence in Edmonton. He wanted to be part of my poetry life again too. Unfortunately for me (but fine for him, given his health), he died 10 days before the start of the residency; we were able to say goodbye and accompany each other, but the residency plan was altered.

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Were you working on anything specific while there, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: It allowed me to be in Alberta to grieve my father, for sure. I was working on specific projects, and just trying to live more calmly and focus on them. I snowshoed by the river, and took self defense classes, made use of the gym and bike paths and all, and the library was a great resource. The department itself was in a bit of disarray as there were budget cutbacks at the university level and an offer of early retirement packages that year; as well, one of the key poetry people, Christine Stewart, was on sabbatical.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency?

A: Through my usual office hours, I found there was a large contingent from the community who came for advice on every imaginable project and genre, unlike at other university residencies where mainly students make appointments. As well, I met with and worked with many great folks from Modern Languages, both profs and students, and some students in creative writing, via the poetry translation seminar I led all year. They were a marvellous group. I visited Jenna Butler’s poetry class, the TYP classes, attended events in the History department, in Modern Languages, and in English. I was also invited to speak elsewhere in Alberta (besides the exchange with U of Calgary): I gave a class in the history of writing and thinking at the college in Maskwacis, the Cree community south of Edmonton, and a talk at the U of Lethbridge.

Q: What do you see as your biggest accomplishment while there? What had you been hoping to achieve?

A: For me, the highlights were my class visits doing workshops in the TYP classes — the Transitional Year Program for Indigenous students coming into the university for the first time. They really inspired me, both the students and the profs, and excited me by their desire to learn and not just to learn, but to change learning as we know it, change the university, grasp new ways of viewing learning. Also, the river was a highlight.

Q: Were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while in Edmonton? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: The literary community in Edmonton is rich and varied and very welcoming in many ways; I would say I hung out more with the landscape and with the writing I was critiquing, and with my own projects which I desperately needed to work on! It was a renewal, for me. A luxury and and a fount of new energy. And I met folks I still keep in touch with, probably moreso than at other residencies. Had many great interactions with profs in the dept, such as Dianne Chisholm, Julie Rak, Keavy Martin. And because of the neighbourhood I was living in, and the fact that I did my grocery shopping on a bicycle and not in a car, I also had a lot of interesting conversations about the downside of the oil industry and the crises in mental health that people were living with on the streets. I met a lot of people who were ravaged, really, but also, strangely, full of hope for their day. I learned a lot.

Q: Given you are originally from Alberta (specifically, Calgary), was there any element of the position that felt like a return?

A: Being in Alberta was great. I grew up in Calgary decades ago, a different Calgary than the one that exists today. I have brothers in and near Edmonton, who are great guys, and my roots are definitely in the landscape of Alberta, those sounds, those trees, the river, the animals along the river. All these are my familiars, in a way, and kindling those relationships was vital to me. I felt close as well to both my parents, to their movements and voices, and to my grandmother. All of which really helped me work.

Published on June 24, 2016 05:31