Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 339

July 13, 2016

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Shaun Marie (with ChiaLun Chang, Sarah Francois, Krystal Languell + Monica Sun) on Belladonna*

Belladonna*

is a feminist avant-garde collective, founded in 1999 by Rachel Levitsky. 2016 marks the 17th anniversary of the Belladonna* mission to promote the work of women writers who are adventurous, experimental, politically involved, multi-form, multicultural, multi-gendered, impossible to define, delicious to talk about, unpredictable and dangerous with language.

Belladonna*

is a feminist avant-garde collective, founded in 1999 by Rachel Levitsky. 2016 marks the 17th anniversary of the Belladonna* mission to promote the work of women writers who are adventurous, experimental, politically involved, multi-form, multicultural, multi-gendered, impossible to define, delicious to talk about, unpredictable and dangerous with language.Interview answers from: Shaun Marie is a poet based in Brooklyn, studying Creative Writing at Pratt Institute. She has a chapbook titled In the Land of Women published through Thistlemilk Press. She is currently finding ways to marry film theory with poetry.

With additional contributions from:

ChiaLun Chang is the studio manager and intern coordinator at Belladonna* Collaborative.

Sarah Francois is a new graduate from Long Island University Brooklyn Campus with an MFA in Cross-genre Creative Writing.

Krystal Languell is the finance manager for Belladonna* Collaborative and her second book, Gray Market, comes out from 1913 this fall.

Monica Sun is an undergraduate student currently at Wesleyan University pursuing the Dance Major and the Writing Certificate.

1. When did Belladonna* first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?Belladonna* was founded in 1999 by Rachel Levitsky. But for me, Belladonna started when I became an intern during the Spring 2016 semester of my studies at Pratt Institute. I had heard of the press from many of my poetry professors, who insisted I send in my resume. Once I started, it was such an easy transition (as it should be for any future interns). There is a collaborative spirit, a community of poets and writers supporting each other. When you hear about Belladonna* being a non-profit and existing and flourishing solely because of its team leaders, that’s the honest truth. Everything made by Belladonna* is the result of individual women dedicating their time and efforts to the creation of smart, progressive, and challenging poetry. It really is like a plant growing from the ground up. It needs water, it needs air; it’s an investment and it takes time. I have a new respect for how responsible my supervisors are and how they are able to keep Belladonna* thriving.

2. What first brought you to publishing?I am a writer first and foremost. I am a poet. I study Creative Writing at Pratt Institute with a minor in Cinema Studies. I took a chance interning at Belladonna* and was pleasantly surprised by how immersive the editing process is. My internship responsibilities vary day by day, but I do partake in the publishing process. Seeing the drafts and final manuscripts of our chaplets, seeing events and readings come together and people coming out to support our featured writers is the best experience. It’s incredibly rewarding, and also reminds me that it takes a village, a community to allow art—good art—to reveal itself. Belladonna* dispels the misconception that people are just born with golden nuggets of genius; rather, people are provided opportunities and avenues by which they are able to create. Belladonna* is a vehicle for that, and keeps giving and giving and renewing itself.

3. What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing?Our responsibilities are especially condensed, and we are entirely reliant on one another. If one person is sick or out, another must step up to the plate. That’s why I’ve grown to really respect the women of Belladonna*. It’s a true commitment that they have integrated into their lives, this bond to a press that sometimes isn't easy or immediately rewarding. The reward is in the community; seeing a recent chaplet sell out, or watching new books win awards4. What do you see your press doing that no one else is?Belladonna* is very genuine. The aesthetic of a small press or underground poetry press can often be used to sell the press as this cool, up-and-coming organization. But Belladonna* is the definition of collective. It is a small press to its core and it doesn't try to be anything else. Its backbone is made up volunteers, interns, and collective members. You give what you can. It’s very fluid; people come and go like a wave. So I would say Belladonna* is the type of press that stands by its word. Not to say that this is uncommon, or not being done by other small distributors, but when you read a Belladonna* book, you know it's the result of many hands working together. You know it's a product of the community.

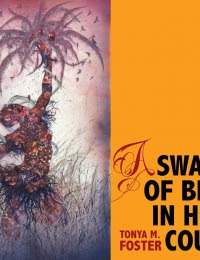

5. What do you see as the most effective way to get new books out into the world?That’s hard to answer as literature in general is becoming a medium that is accessible on social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook. People are able to publish their work immediately. There’s definitely a sense of authorship, but a lack of ownership. Things are so easily accessed and distributed. You find yourself questioning the original source or the validity of the work. In terms of publishing, the most recent changes are the changes that render writing an easily accessible and digestible medium. Belladonna* has the chaplet series which features the work of poets still in the process of working through and editing their final manuscripts. So the chaplet is a medium of its own, and stands as this testimonial or documentation of the writing process. In a way, our chaplets have built this elaborate archive of works in their beginning and final stages. I was able to see Tonya M. Foster’s chaplet (#34, published in 2002) for A Swarm of Bees in High Court in the studio in its early stages. Now it’s become a celebrated work, but I have seen the amount of time and attention Foster dedicated to honing in on the sound and the word play, which has made it such a great success. I’ve recently found authors who ask for donations to provide access to their writing process online. To me, that’s such a fascinating idea. People are interested in the process, in the editing stages of a work just as much as they are invested in the final product. So in terms of new ways to release books, I think making the process visible makes it an act of community-building. It becomes a gesture to the reader. I think the goal is to sell books, but also to make the book a collaborative experience as a whole.

6. How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?Towards the end of the semester, I did a lot of outreach and grant writing and researching. When we had more chaplets coming out during the middle of the semester, I did a little bit of copy-editing and was responsible for organizing the Studio Assistants chaplet, which was a great opportunity Belladonna* gives its interns to publish our work. This has been an annual event for interns since 2012 now. It’s an interesting process because poetry isn't edited like fiction. Of course, there’s the occasional typo or misprint, but editing poetry is like editing music and language and space. Nothing is fixed. Everything is intentional. The space of the page is engaged in a manner you don’t see in fiction, unless it’s prose poetry or experimental fiction, but even then, it can adhere to the formal aesthetics of fiction. I enjoy how Belladonna* is an open book. You have access to the emails and you can see how the process is coming along from one message to the next. You know when a chaplet is being finalized with the designer, Bill Mazza, and you know when it’s being sent to the print shop. We are in direct contact with our writers and contributors. The process is organic and I suppose because of that, it’s even more transparent. You understand fundamentally what this community is truly doing and why it’s so important, especially when you're working with writers who are producing content that is urgent and necessary.

7. How do your books get distributed? What are your usual print runs? We reach out to poets, and invite them to be a part of our reading series. They publish a chaplet of their work and participate in a reading with said chaplet and/or recent work they want to discuss. The writers are given a lot of authority and authorship. The chaplet exists as a medium small enough to open up a dialogue about the new work without stifling it with criticism. It’s like a mini writing group; a preview of the work that helps guide the authors in their final steps in producing their works. A discussion begins and the author can then work with it.

And we have our full-length books of poetry, which are of course more permanent, and these are really compelling. For most of these works, we do a first print run of 1,000 copies. Tonya Foster’s A Swarm of Bees in High Court is a favorite of mine, but you also have these amazing sound-based works like LaTasha Diggs’ TwERK that are very powerful and urgent.

8. How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?It’s a matter of determining what work is needed and how my time will help the quality of the work being published. Sometimes I’m not needed, but there are other small tasks that I can be involved with. As an intern, you realize that your time can sometimes inconvenience others if you overstep where you're needed. It doesn’t make sense for me to be involved in something that requires more expertise. In those cases I usually take on the role of shadowing so I can learn and adapt. I’ve also learned that listening in some cases is more beneficial than doing. I’ve been introduced to amazing writers and amazing organizations that support new writers. Belladonna* is extremely focused on the community and the volunteers that keep our organization alive. In terms of collaborating with other editors, the posthumous publication of Beth Murray’s Cancer Angel would be a great example of Belladonna* working together with writers and editors in the San Francisco Bay Area. Cancer Angel stands as a collaborative work, one that I know proved how flexible and intuitive this collective can be in the hardest of circumstances.

8. How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?It’s a matter of determining what work is needed and how my time will help the quality of the work being published. Sometimes I’m not needed, but there are other small tasks that I can be involved with. As an intern, you realize that your time can sometimes inconvenience others if you overstep where you're needed. It doesn’t make sense for me to be involved in something that requires more expertise. In those cases I usually take on the role of shadowing so I can learn and adapt. I’ve also learned that listening in some cases is more beneficial than doing. I’ve been introduced to amazing writers and amazing organizations that support new writers. Belladonna* is extremely focused on the community and the volunteers that keep our organization alive. In terms of collaborating with other editors, the posthumous publication of Beth Murray’s Cancer Angel would be a great example of Belladonna* working together with writers and editors in the San Francisco Bay Area. Cancer Angel stands as a collaborative work, one that I know proved how flexible and intuitive this collective can be in the hardest of circumstances. 9. How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?I appreciate space now when I sit down to write. When you spend time studying and editing the way in which others use sound to support their work, there’s an appreciation for music. The form should match the content. When I say form, what I’m referring to is content as composition. Is the content self-reliant? Is the content contained in itself or does it allow for a discourse? In lyric, too often the focus is on the I and the I in relation to the object of desire, the you. I’ve enjoyed seeing this subverted, seeing the form allow for multiple accounts and perspectives, but mainly the I as ever-changing, ever-expanding. Is the form capable of caring for the content? Is it allowing the content to expand and develop as it’s intended? Is using a couplet here hurting or helping the content? It’s a composition; they communicate with one another. If you're worried about aesthetics, you're probably more concerned with writing something that’ll connect with or start discussions about trend writing, the writing that we all fall into when we attempt to write things uninspired. And of course it's not good. It’s impressionable. Working with Belladonna*, I’ve thought a lot about what it means to be a feminist. There’s a collaborative spirit a lot of the time with feminist literary works. There is reclamation of self and community, a celebration of supporting and recognizing each other. And this transpires into the space imbued within the poetry. The sense that you are cared for and acknowledged. You have to allow for that in the work.

10. How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?Being published by a press is always followed with the sense of accomplishment. The idea is: you worked with editors, your work was accepted, and someone found you worth investing in. But in opposition, there’s the reality that people have a lot of power in today’s age. You can self publish on a multitude of platforms, and although any work you self-publish is subject to your own outreach skills, there is a sense of reclaiming the authorship of your work. The deadline and release date are entirely the decision of the writer, which is a form of creative freedom, but what’s missing is the support system and tools you'd be able to access with a team behind you. But I suppose that’s why I appreciate small presses. They maintain a level of respect and empowerment with the author. I don’t think the writers compromise or give up their agency with Belladonna*; it’s a true partnership and that’s ideal.

11. How do you see Belladonna* evolving?Though Belladonna*’s aesthetic is ever-evolving and changing, I’d like to see an aesthetic that is immediately acknowledged as a Belladonna* product. I like seeing beautiful books, books with evocative and alluring art that draws the reader in. I also see Belladonna* gaining even more participants, volunteers and collective members. I’ve realized how much my supervisors and peers pay attention to the ways in which our society engages with literature and poetry. I think Belladonna* has the potential to eventually make the writing process a medium to invest in, like featuring artists and their personal journeys with major projects they are undertaking. There’s a genuine connection to the writing practice and the finished product. They are inseparable. It’s of the body, it can’t not be.

12. What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What do you think people have overlooked about your publications? What is your biggest frustration?I enjoyed seeing the success of Tonya M. Foster’s A Swarm of Bees in High Court. This book inspired me in my personal work, but also reminded me that a community is responsible for making good art accessible and visible. It reminded me of why the small press is such an important part of the literary community. You're reminded poetry must exist in a space where people are eager to engage and work with it. I can’t say that I’m frustrated by much; rather, I understand now that sometimes there simply isn't enough energy to go around. Sacrifices are made when running small publishing organizations, and you have to remember that the strides we make in the community affect the present and future. I’m most satisfied when the work I’m surrounded with is truly communicating and engaging with dialogues capable of rendering change.

13. Who were your early publishing models when starting out?I use Belladonna* as a model because I know how we work. I know how this press keeps itself alive and thriving and I know how this press deals with success and failure. I have a lot of respect for the collective and I think Belladonna* has taught me that a press relies on its community.

14. How does Belladonna* work to engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large? What journals or presses do you see Belladonna* in dialogue with? How important do you see those dialogues, those conversations?Until I started interning, I didn’t realize how involved our press is. We are in direct contact with a lot of small publishers like Litmus and Futurepoem. Our events are hosted at a multitude of locations that help bring visibility to independent bookstores and poetry-based organizations. I think the way we share resources with these other organizations is crucial for our survival.

15. Do you hold regular or occasional readings or launches? How important do you see public readings and other events?Readings and events are the press’s backbone. Readings are a sign of community and a sign of outreach. I’ve learned so much about my work from going to readings and engaging with writers. It seems only natural that writers support one another at readings; it allows the work to exist in a space of care, but it also shows an amount of respect for the work and the time that was put into the finished product. Readings and events reveal the work that’s being done behind the scenes. It goes back to the idea that everything is sustained by a caring community, and that this community is responsible for making sure people are being heard and recognized. At most of our events, the host takes a moment to call out the names of all the Belladonna* members, volunteers, and interns who are present—and this roll call further highlights that behind the scenes labor.

16. How do you utilize the Internet, if at all, to further your goals?I think the internet is as essential as drinking water nowadays. We not only consume media at a fast pace, but we also consume media as entirely image-based now. The internet is like a form of cinema. So it follows that small presses use social media to reach as many people as possible. It’s not that we’re selling the Belladonna* brand or capitalizing off of the system; rather, we’re adapting to the way people engage with work. It’s all one big conversation, and if the conversation must also exist online, then we adapt. It makes sense to do everything we can to make these dialogues possible, and to provide avenues and ways to connect with one another.

16. How do you utilize the Internet, if at all, to further your goals?I think the internet is as essential as drinking water nowadays. We not only consume media at a fast pace, but we also consume media as entirely image-based now. The internet is like a form of cinema. So it follows that small presses use social media to reach as many people as possible. It’s not that we’re selling the Belladonna* brand or capitalizing off of the system; rather, we’re adapting to the way people engage with work. It’s all one big conversation, and if the conversation must also exist online, then we adapt. It makes sense to do everything we can to make these dialogues possible, and to provide avenues and ways to connect with one another. 17. Do you take submissions? If so, what aren’t you looking for?Belladonna* does consider queries as they come in via email, but we most often take on projects through the readings series and proposals by members of our collective. Sometimes, submissions are sent in that disregard or overlook that Belladonna* has a non-hierarchal, feminist, avant-garde collective mission. Nonetheless, we are always accepting new volunteers and interns who are eager to help build and shape the press.

18. Tell me about three of your most recent titles, and why they’re special.Tonya M. Foster’s A Swarm of Bees in High Court is a beautiful ode to Harlem, race, identity and space. It’s sound-based, brilliantly written, and takes on multiple voices and perspectives. Another favorite of mine is LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs’ TwERK. I think TwERK is extremely urgent and impassioned. Also, a lot of detail is given to the sound and music of the work. I also enjoyed R. Erica Doyle’s proxy, which I think is a very sexy and challenging book. It keeps me alert and sensitive in ways other books with similar content fail to do. It gets under my skin, and I feel like I have to properly metabolize it when reading it.

12 or 20 (small press) questions;

Published on July 13, 2016 05:31

July 12, 2016

Sarah Mangold, Giraffes of Devotion

I had a terrible time because I was not takingthe liquor in those days and they’d say Nowwhat will you drink Of course naturally mydear husband would drink whatever theyoffered him like most naval officers And I

said Nothing thank you And they would havea fit and say You must have something I’d sayno no I’m not thirsty It doesn’t make anydifference you must have something This gotto be terrible you know Then they startedsaying What will we give Mary to drink Canyou feature (“Yes but not—”)

Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold’s third full-length poetry collection is Giraffes of Devotion (Tucson AZ: Kore Press, 2016), a collection described as an experiment “to present a rebelliously voiced witness and investigator into U.S. history, its families and war. Framed within the domestic sphere of military service, facts and speech are misheard, whispered, indexed and reassembled to reveal the word make spirit.” As Kore Press editor Ann Dernier writes in the press release:

In the mid-1920s, Sarah’s great grandmother Mrs. Roy Smith followed her husband Lt Commander Roy Smith with their four children to Shanghai where he was stationed with the US Navy in the years following the Boxer Rebellion. In the tradition of family stories, Giraffes of Devotion is the patient work of collage created from oral history archives and a lifetime of letters, and in that tradition, this narrative incorporates lapses of time. It sputters, pauses, rushes ahead, but all of the gaps fade with each new letter, each new poem and each plunges the wealth of memory of a lifetime of service, of military service and in service to husbands and fathers in land both occupied and occupying.

Giraffes of Devotion follows Mangold’s previous collections,

Electrical Theories of Femininity

(Black Radish Books, 2015) [see my review of such here] and

Household Mechanics

(New Issues, 2002) (a chapbook was recently released through above/ground press); an earlier section of the new collection appeared as a chapbook under the project’s working-title, Boxer Rebellion (Bainbridge Island WA: g o n g, 2004). The “Boxer rebellion,” for those who don’t know (including myself), Wikipedia describes it thusly: “The Boxer Rebellion, Boxer Uprising or Yihequan Movement was a violent anti-foreign and anti-Christian uprising which took place in China towards the end of the Qing dynasty between 1899 and 1901. It was initiated by the Militia United in Righteousness (Yihetuan), known in English as the ‘Boxers,’ and was motivated by proto-nationalist sentiments and opposition to imperialist expansion and associated Christian missionary activity. An Eight-Nation Alliance invaded China to defeat the Boxers and took retribution.” In an interview conducted in 2013, posted at seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics, Mangold specifically discusses the chapbook, and more generally, the work-in-progress that ended up being Giraffes of Devotion:

Giraffes of Devotion follows Mangold’s previous collections,

Electrical Theories of Femininity

(Black Radish Books, 2015) [see my review of such here] and

Household Mechanics

(New Issues, 2002) (a chapbook was recently released through above/ground press); an earlier section of the new collection appeared as a chapbook under the project’s working-title, Boxer Rebellion (Bainbridge Island WA: g o n g, 2004). The “Boxer rebellion,” for those who don’t know (including myself), Wikipedia describes it thusly: “The Boxer Rebellion, Boxer Uprising or Yihequan Movement was a violent anti-foreign and anti-Christian uprising which took place in China towards the end of the Qing dynasty between 1899 and 1901. It was initiated by the Militia United in Righteousness (Yihetuan), known in English as the ‘Boxers,’ and was motivated by proto-nationalist sentiments and opposition to imperialist expansion and associated Christian missionary activity. An Eight-Nation Alliance invaded China to defeat the Boxers and took retribution.” In an interview conducted in 2013, posted at seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics, Mangold specifically discusses the chapbook, and more generally, the work-in-progress that ended up being Giraffes of Devotion:SM: Rukeyser’s US 1 and Reznikoff's Testimony were very present as I started working with historical documents and an oral history transcript for my long poem Boxer Rebellion. They both use historical source texts with many voices and they both use documents that could have been filed away as bureaucratic documentation. George & Mary Oppen, Lorine Niedecker, Beverly Dahlen, Susan Howe, and of course John Ashbery were also instrumental in how I go about writing and thinking about writing.

[…]

rm: What was the process of composition for your chapbook, Boxer Rebellion? You mention a love for documentary poetics, and this short work is strongly influenced by very specific historical fact, yet I’m intrigued at how the work isn’t written out as straight documentary. It’s almost as though the facts themselves are broken down into language, and reshaped into the poem on that level. How do you manage to use real information without composing poems (like so many others have done) simply regurgitating story?

SM: Yes! That’s exactly what I tried to do—happy that comes through. Boxer Rebellion is a long poem about my great-grandmother’s life as a Navy wife in China during the early 1920s with her four children. I had heard stories about moments in China from my grandmother and my mom throughout my childhood but I hadn’t heard the story laid out from start to finish within an historical context. The source text is an interview my great-grandmother gave to the US Naval Institute as part of their Navy wives oral history project, complete with index. The facts had such an emotional connection for me I decided the only way to start working with it was to break everything back into language, not a story, not history, not a family biography. That’s how the alphabetical sections started—I retyped the index and did an alphabetic sort just to free up the language and it read like a condensed oral history, complete with stutters and repetitions. With the rest of the transcript I wrote down the phrases that caught my attention and used those as the building material for the poems. My first experiments started in 1998 and a few years later I had a chapbook together but I've also recently spent more time with the transcript to make the poem book-length so hopefully a new book will be in my future.

Mangold has engaged in the poem suite for some time, constructing chapbook-length, and now, book-length, manuscripts out of lyric fragments, and her Giraffes of Devotion follows this path, shaping and reshaping threads of family history and story into a documentary collage that opens into a series of foreign and long-forgotten histories. Her poems are wonderfully playful, utilizing the materials of language and story to create a series of delightful sound-fragments and poem-shapes, re-telling a series of seemingly-random stories in the voices (pauses, repetitions, warts and all) that once told her. There are moments I think the poems in this collection might serve as a series of monologues, for the sake of a staged performance of the entire text.

the missionairies kept pointing out that if we weren’t therethings would be peaceful and lovelyit was our faultand Roy was terribly upset

they were going to the Shanghai American Schoolbut his father said Now if you like you can take two friendsdown aboard ship I’ll be home for the weekend You can godown and stay in my cabin You can have movies and be aboardship

to Roy age twelve a weekend on the ship was just heavenlyhe asked two friends first one and the other to his horrorcarried on as if he’d asked them to visit hell (“But we were not any more popular than nothing”)

Published on July 12, 2016 05:31

July 11, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Christine Kanownik

Christine Kanownik

is the author of

KING OF PAIN

(Monk Books 2016). Her poetry can be found at FENCE, Poetry Crush, Jubilat, among others. Her chapbook We Are Now Beginning to Act Wildly was published in 2012 by Diez Press.

Christine Kanownik

is the author of

KING OF PAIN

(Monk Books 2016). Her poetry can be found at FENCE, Poetry Crush, Jubilat, among others. Her chapbook We Are Now Beginning to Act Wildly was published in 2012 by Diez Press.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I suppose the biggest thing that has changed is that my book is done. I can’t fiddle with it anymore. It was important for me to have that kind of end to it or else I think I would be writing those poems forever. I had long described my writing process as Penelope destroying her weaving, waiting for Odysseus to come home. So this formal finality is very helpful for me.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

We were required to take a poetry class in undergrad and my professor was the excellent poet Kristy Odelius. I most certainly would never have thought to be a poet if it weren’t for her. I was writing a novel at the time.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I used to be more particular but I feel like I’ve really fallen into a sawed-off shotgun style approach to my writing. There is a more laborious arranging process, but actual composition is more akin to the Romantic notion of poetry through inspiration. Though it sounds pretty corny to say so.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Oh I can’t even imagine writing a book from the beginning. That seems insane. You start with a big heap of poems idea and then you end up cutting and shuffling and writing more. Someone should figure out how to print a time lapse manuscript.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

My initial thought was that I dislike going to reading but I love reading, but that probably isn’t anything anyone wants to hear. Readings can be so wonderful. Like I just hear Karen Weiser and Stacy Szymaszek read at KGB here in Mnhattan. That was an exceptional reading and the two were very well-matched. And then last night my roommate Amy Lawless had a book launch/conversation with the co-author Chris Cheney at a gallery in the middle of nowhere Brooklyn. The energies were completely different. But both nights reminded me how great the poetry community can be.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My poetry is concerned with what I’m concerned with. A recent tone of my poems is that of outrage and anger. I am angry at the casual racism and sexism and phobia I see every day and then in the poetry world. It’s a place that you would hope for better. But it, like everything, is a victim to the hand of patriarchy. Fuck your theories, people are dying.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Ah yes. The Role of the Poet. I feel like that is for each poet to decide. I like writing. I like being happy. Writing makes me happy, well, and also quite miserable. I’m not going to aribit anything.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It was great. I love putting my work in other people’s hands. It’s a truly beautiful form of collaboration. I’m not precious about my work for the most part so when someone says to cut a whole poem or stanza, it feels great. Like throwing stuff away when spring cleaning or chopping all your hair off. Both are things I love. I love throwing things away, even things I’ve horded for years.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

There are a bunch of Kathrine Hepburn quotes in the Kathrine Hepburn garden that is right by my work. She seemed like she was imminently quotable. I like to think of her these days, wearing a fashionable pants suit after a quick game of baseball. As long as I keep imaginary Kitty happy, I know I’ll be happy.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’m usually getting up late to go to work. I’m trying. One of my goals is to try and become a morning person. So far I’ve managed to mostly get to work only thirty minutes late, rather than 45. Writing in the morning just sounds so dreamy. But I can (and do) write anywhere. I write on the train a lot. I get a lot of stimulus listening to people and then I’ll get angry at something and write a poem. I wrote while watching Ally McBeal the other day. But writing out the window with a cup of coffee and like there’s a newspaper on the table and a dog there. It sounds great.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

There we go. Inspiration does sound cheesy. My tricks are just writing down the first thing that comes to my mind. Oh, or I’ll read someone else’s poems. A book of poems that I like very much will take me a long time to read because I will write so much while reading. That happened most notably to me while reading Women in Public by Elaine Khan. I feel like I could dedicate a whole chapbook to her.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

That’s a funny question. I moved around a bit and all my family has moved out of any place that I had ever lived in. I’m not very close to my biological family at all. I’ve lived in many different parts of America through many formative periods of my life, so I have lots of answers to the question “where are you from?” Probably my apartment now is the closest thing to having a home as I can imagine. And my apartment now smells like nag champa, Brussel sprouts, baked almonds, lavender, and pot.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Movies have historically been important for my creative process. But a lot of what I’m writing now is in relation to paintings. Oh, and still movies. I wrote several poems recently while and after watching the Danish movie Haxan. I also get obsessed with really bad music. Right now I cannot stop listening to Meat Loaf. Jesus, that’s embarrassing. I plan on writing a lot about Meat Loaf.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Colette, Duras, Elliot, Woolf, Stein, Baldwin, hooks, Lorde are all on my fantasy league. Living writers are equally if not more important. Ali Power, Amy Lawless, Lauren Hunter, Paul Legault, John Beer, Bianca Stone, Ana Božičević, Jennifer Nelson, etc.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I want to make a movie. I’m working on a script now. I love movies, as I mentioned earlier, but I partially want to direct a movie because there are like 10 females directors in movie history. I also want to be an airplane pilot for the same reason.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

That would be pretty cool if poet was my occupation. I work in publishing. And since we are probably are at the tail end of the history of print publishing, I spend a lot of time thinking about new career paths. I want to be a screenwriter, magic store owner, or go to the 1930s and join a Vaudeville troupe.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It’s such a good excuse for both completely hiding away from people for days but always having a party you can go to when you get tired of your own thoughts.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’m reading Silas Marner right now. I love George Eliot and would recommend Middlemarch to any thoughtful human. Her emotional intelligence is really so outstanding. Silas Marner isn’t as good as Middlemarch, but it’s still great. I wrote a horror novel after reading Middlemarch. It has so many characters.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a book of poetry about decapitation and post-mortem brain removal. A lot of people had their brains or heads removed after their death. Both Joseph Haydn and Oliver Cromwell. It seems shocking now, but the more Wikipedia pages I read, the more it seems to have been a pretty common occurrence. Even Shakespeare. So really light, fun stuff!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 11, 2016 05:31

July 10, 2016

Nelson Ball, Chewing Water

On A Hilltop, Near Drumbo

Twocows

in the sky

exceptwhere hooves and heads

touchearth

Paris, Ontario poet and bookseller Nelson Ball’s latest poetry collection is

Chewing Water

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2016), adding to the growing collection of books he’s produced over the two decades-plus since ending his extended silence (prior to that, he’d a flurry of 1960s and 70s publications), including With Issa: Poems 1964-1971(ECW Press, 1991), Bird Tracks on Hard Snow (ECW Press, 1994), The Concrete Air (The Mercury Press, 1996), Almost Spring (The Mercury Press, 1999), At The Edge Of The Frog Pond (The Mercury Press, 2004) and

In This Thin Rain

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2012) [see my review of such here], as well as numerous smaller publications through Apt. 9 Press, BookThug, Curvd H&z, MindWare, fingerprinting inkoperated, Letters, Rubblestone Press, above/ground press, Laurel Reed Books and others [and: Nelson Ball fans take note: while posting this review I discovered that a Nelson Ball selected poems is due to appear next spring]. Ottawa poet, publisher and critic Cameron Anstee has referred to Ball as “Canada’s greatest practicing minimalist poet,” and Chewing Water continues Ball’s incredibly-packed poems on nature, close friends, reading and other intimate spaces, including his ongoing conversations with his late wife, the artist Barbara Caruso (1937-2009). Ball produces incredibly dense poems that one must briefly inhabit, requiring a close attention for even the smallest movements. Poems such as “The Dead” and “Ducks” showcase a minimalism that moves so easily, quickly and slow that it becomes difficult to breathe, lest the poem simply float apart. In his notes that end the collection, Ball adds: “My writing helps me cope with my loss. I still consult Barbara, aloud and frequently. She tells me to do things I know I should do but have been avoiding. She remains a vivid and wonderful presence inside my head, an addition to the legacy of her artworks and writings.”

Paris, Ontario poet and bookseller Nelson Ball’s latest poetry collection is

Chewing Water

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2016), adding to the growing collection of books he’s produced over the two decades-plus since ending his extended silence (prior to that, he’d a flurry of 1960s and 70s publications), including With Issa: Poems 1964-1971(ECW Press, 1991), Bird Tracks on Hard Snow (ECW Press, 1994), The Concrete Air (The Mercury Press, 1996), Almost Spring (The Mercury Press, 1999), At The Edge Of The Frog Pond (The Mercury Press, 2004) and

In This Thin Rain

(Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2012) [see my review of such here], as well as numerous smaller publications through Apt. 9 Press, BookThug, Curvd H&z, MindWare, fingerprinting inkoperated, Letters, Rubblestone Press, above/ground press, Laurel Reed Books and others [and: Nelson Ball fans take note: while posting this review I discovered that a Nelson Ball selected poems is due to appear next spring]. Ottawa poet, publisher and critic Cameron Anstee has referred to Ball as “Canada’s greatest practicing minimalist poet,” and Chewing Water continues Ball’s incredibly-packed poems on nature, close friends, reading and other intimate spaces, including his ongoing conversations with his late wife, the artist Barbara Caruso (1937-2009). Ball produces incredibly dense poems that one must briefly inhabit, requiring a close attention for even the smallest movements. Poems such as “The Dead” and “Ducks” showcase a minimalism that moves so easily, quickly and slow that it becomes difficult to breathe, lest the poem simply float apart. In his notes that end the collection, Ball adds: “My writing helps me cope with my loss. I still consult Barbara, aloud and frequently. She tells me to do things I know I should do but have been avoiding. She remains a vivid and wonderful presence inside my head, an addition to the legacy of her artworks and writings.”Canada For Ted Rushton

William Hawkinsremains in Ottawa, that cold city

where he writes poems about Tallahassee.I remain in southwestern Ontario, where

occasionally it’s as cold as Ottawa,and where I puzzle about Arizona,

in its great distancefrom our cold and snow.

It’s irrational that we stay put.My friend Catherine gives a reason:

our wild animals in this cool climatedon’t want to eat us, except bears

who mostly hide from us in the forest.In South Carolina, alligators

roam the streets and lawnsand one has to be nice to them.

Published on July 10, 2016 05:31

July 9, 2016

Drunken Boat blog "spotlight" series #3: Kaie Kellough

The third in my monthly "spotlight" series over at the Drunken Boat blog, featuring a new poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online:

Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough

. The first two in the series feature

Canadian poet Amanda Earl

, and

American poet Elizabeth Robinson

. A new post is scheduled for the first Monday of every month.

The third in my monthly "spotlight" series over at the Drunken Boat blog, featuring a new poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online:

Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough

. The first two in the series feature

Canadian poet Amanda Earl

, and

American poet Elizabeth Robinson

. A new post is scheduled for the first Monday of every month.

Published on July 09, 2016 05:31

July 8, 2016

Touch the Donkey supplement: new interviews with Cook, Turcot, Betts, Schmaltz, Zits, Sims and Collis

Anticipating the release next week of the tenth issue of Touch the Donkey (a small poetry journal), why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the ninth issue: Sarah Cook, François Turcot, Gregory Betts, Eric Schmaltz, Paul Zits, Laura Sims and Stephen Collis.

Anticipating the release next week of the tenth issue of Touch the Donkey (a small poetry journal), why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the ninth issue: Sarah Cook, François Turcot, Gregory Betts, Eric Schmaltz, Paul Zits, Laura Sims and Stephen Collis.Interviews with contributors to the first eight issues, as well, remain online, including: Mary Kasimor, Billy Mavreas, damian lopes, Pete Smith, Sonnet L’Abbé, Katie L. Price, a rawlings, Suzanne Zelazo, Helen Hajnoczky, Kathryn MacLeod, Shannon Maguire, Sarah Mangold, Amish Trivedi, Lola Lemire Tostevin, Aaron Tucker, Kayla Czaga, Jason Christie, Jennifer Kronovet, Jordan Abel, Deborah Poe, Edward Smallfield, ryan fitzpatrick, Elizabeth Robinson, nathan dueck, Paige Taggart, Christine McNair, Stan Rogal, Jessica Smith, Nikki Sheppy, Kirsten Kaschock, Lise Downe, Lisa Jarnot, Chris Turnbull, Gary Barwin, Susan Briante, derek beaulieu, Megan Kaminski, Roland Prevost, Emily Ursuliak, j/j hastain, Catherine Wagner, Susanne Dyckman, Susan Holbrook, Julie Carr, David Peter Clark, Pearl Pirie, Eric Baus, Pattie McCarthy, Camille Martin and Gil McElroy.

The forthcoming tenth issue features new writing by: Meredith Quartermain, Mathew Timmons, Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Luke Kennard, Shane Rhodes and Amanda Earl.

And of course, copies of the first nine issues are still very much available. Why not subscribe?

We even have our own Facebook group. It’s remarkably easy.

Published on July 08, 2016 05:31

July 7, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with William Mark Giles

William Mark Giles: I live on Turtle Island, on the traditional territory of the the Kainai, Piikani, and Siksika Nations of the Blackfoot Confederacy, and also the traditional territory of the Tsuu T’ina and Stoney Nakoda First Nations. It’s more convenient to say I live in the neighbourhood of Fairview, in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, North America — but people were here a long time before I showed up, and the land sustained and taught them. Treaty 7 was signed at Blackfoot Crossing in 1877 and now encompasses the traditional lands of these first nations. That’s where Calgary is now. My (his)story of colonial settlement cannot overwrite the(ir) story of continuous habitation. It is our story now. In The Making Treaty 7 project, the late Narcisse Blood and the late Michael Green shared the belief the “We are all treaty people.”

William Mark Giles: I live on Turtle Island, on the traditional territory of the the Kainai, Piikani, and Siksika Nations of the Blackfoot Confederacy, and also the traditional territory of the Tsuu T’ina and Stoney Nakoda First Nations. It’s more convenient to say I live in the neighbourhood of Fairview, in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, North America — but people were here a long time before I showed up, and the land sustained and taught them. Treaty 7 was signed at Blackfoot Crossing in 1877 and now encompasses the traditional lands of these first nations. That’s where Calgary is now. My (his)story of colonial settlement cannot overwrite the(ir) story of continuous habitation. It is our story now. In The Making Treaty 7 project, the late Narcisse Blood and the late Michael Green shared the belief the “We are all treaty people.”I offer acknowledgement to the original dwellers, and my gratitude. I hope I can learn to learn from this land too.

I have written two books of fiction, Knucklehead and Seep , both published by the amazing Brian Kaufman and his gang at Anvil Press in Vancouver. Knucklehead won the W.O. Mitchell City of Calgary Book Award, and was nominated for the Howard O’Hagan Award. About Seep, E.H. of Kelowna, B.C., had this to say: “I read the scene with the dog on an airplane and got the stink eye from my seat partner.” I have published stories and poems, presented visual poetry, and performed theatre in venues in Canada and the U.S.A.

1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’m not sure my own first book changed my life much — it almost came as a relief, as a kind of material evidence that yes, I can do this thing called writing; and doing so I can engage in a conversation with the world. I had a long and slow approach — into middle age when the first book came out. In terms of recent work feeling different — I think I am more comfortable (confident?) with writing the long scene, letting story take its time.

The book that actually changed my life was Samuel R. Delany’ Dhalgren. I read pretty much nothing but science fiction as a teen and young man. I had finished high school, was three years into a working life at a blue collar job, in a ramshackle house with a bunch of guys. I was a pothead, and flirting with alcohol (we eventually ended up going steady for a while, alcohol and me). And I get Delany’s sf book in which a guy has sex with a woman who turns into a tree and then he goes into a blasted city and has sex with a man, all in the first 30 pages. Isaac Asimov this ain’t. Then the book spends the next 800 pages taking itself apart and putting itself together, only to lead me back its beginning. And really, that reading experience blew my mind. I discovered that there was a whole tradition of experimental novels and big thick narratives that wrestled with the intricacies of the human condition. And then I figured out out Delany was African American and gay and I had to rethink the whole book over again in terms of race and queerness, though I didn’t have the vocabulary to use words like that and to really wrap my head around it. So I went in search of that vocabulary. That’s the book that changed the trajectory I was on.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I come from a family of readers, and we read prose in our house. My mother could recite great gouts of Coleridge and Tennyson from memory, but I don’t recall a lot of books of poetry lying around. “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” as Joan Didion puts it — and narrative, for me at least, is a way of ordering that spectacle of human behaviour unfolding before my very eyes.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Yikes! What a question. I have some pieces of writing that fall like pennies from heaven. I am working on finishing a story right now that came to me more or less that way (at least the first half did). I also have a series of “micro-fictions” that develop more or less whole — though I’m not sure how to publish stories that are 35 or 120 or 215 words long. But other pieces can take years to find their form. I often struggle with openings — so I will have a lot of false starts as I search for that elusive “voice” — not my voice, but what I call the necessary voice (sometimes plural) that will establish the narrative positioning of the work. Not just p.o.v. or tense or retrospection, but a feel for how close and at what angle the telling of the story is in relation to the story being told. So yeah, sometimes that means reams of notes and false starts and abandoned bits. You can see the process at work in my novel Seep, which kinda has four openings in sequence as it establishes the multiple voices that create a meaning matrix for the book. It took a while to figure out those four angles.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I would say both. I have a sense that my micro-fiction practice will accumulate into something bigger. But I also have some other projects that seem book length. It’s interesting that in last year or so I’ve stumbled across a couple of Stephen King interviews. I’ve never been a gung-ho fanboy — the horror-gothic thing was never my genre of choice. But I’ve read a half dozen of his books and recognize his mastery of craft. To read his take on writing, or to listen to him talk about his creative practice, is fascinating. When he starts with an idea, he really doesn’t know if he’s going to write a short story or a door-stop. And he really rejects the idea of “plot” as a kind of prefab structure. I actually just re-read his On Writing today.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like reading in public — indeed I enjoy it. But I don’t crave the footlights.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

The theoretical concerns behind my writing tend to relate to narratology — how are stories shaped, produced, delivered, and received? What is the connection between narrative and memory, and writing and experience? Is language a material? In terms of current questions, one that I have been thinking about and reading about for the last couple of years has to do with irony and affect. I am interested in creative productions that resist the emotional manipulation inherent in many traditional representational or literary practices — that resistance is the irony part — but which nonetheless move people to feeling and empathy — that’s the affect part.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I am not sure I can make a pronouncement of the role of the writer. I know what I believe and incorporate as part of a personal manifesto for my own work: the curiosity-driven practice of making and exchanging sustains compassionate communities, moves people to feeling and empathy, and creates the future.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Hooray for editors! And if they seem to be difficult — well, either change their approach (hah!) or change the editor . . .

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

This is hard — but the best writing advice for me came from Edna Alford. I had stopped writing for a number of years, then began again in a desultory fashion. And she looked at my assemblage of stories and near-stories and told me to “imagine your book.” Not just a hazy abstract concept, but actually imagine the book object. Draw a picture of it, complete with a cover design. Give it a title. Imagine the flap copy. Make a table of contents. It was only when I did that — and really, it took a couple of hours doodling — that I realized I could have a book — and gave me a clue of the stories which I had yet to write. This eventually led to my first book Knucklehead.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

Hmmmm. I see it all as writing — engaging in those pieces of language, and in the process of making. I sometimes become aware of the limitations I may have in terms of sheer exposure to these other genres, and to the conventions around their production. I read poetry — but not like many of my poet colleagues: they _read_ poetry by the bushel. And in terms of nonfiction — I actually do read bushels of nonfiction; but there seems to be a nonfiction production cycle related to market access, pitching, and deliverables that I haven’t fully grokked (if you’ll excuse a legacy of my sf reading days).

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’d call myself a binge writer. When possessed of the exigent moment, I crank it out. I remember hearing Richard Ford answer a question kinda like this is a interview once. And if I recall it correctly, he basically said when he is in a project, he writes all the time; but in between he’ll go months without writing a word. This allowed me to validate my own propensity to “block.” I can get distracted very easily by other things — job, reading, travel, wikipedia. I joke that when I’m cooking a lot and filling the freezer it’s a sign that I’m avoiding other things.

I try to follow — though I fall in and out of the pattern — a kind of 4-stage routine: 1) Do something for well-being; 2) Do basic life maintenance; 3) Knock something off the to-do list; 4) Do creative practice. Repeat. I sometimes shuffle things around, especially 3 and 4. I sometimes use a timer so I don’t get stuck, or abandon work. I sometimes let myself watch netflix after number 4 before I start number 1 again.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

There is no such thing as inspiration. There is curiosity, and attention, and practice. When I get stalled, I actually have a few straightforward writing exercises that I follow. Some are prompt-based: “Write a sentence with a wall.” Some are process based: noun lists. I sometimes develop “word hoards” around a project — words, fragments, sentences; if I’m stuck: insert word hoard excerpt here and make it work.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Where is home? My home today: coffee. The home where I grew up: madeleines — no, no — maybe a combination of nicotine and beef broth — the odors of my mother’s kitchen.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I am a sponge for cultural productions. Yes, books. Films. I am an autodidact when it comes to art and art history — I love visiting museums and galleries and installations. There have been times in my life when I’ve seen a lot of theatre — theatre has such a presence and a relationship with structure. I’m very keen on the built environment — architecture, urban planning, communication networks.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

This is a really hard thing to answer, as these things change. I finally got around to reading George Eliot’s Middlemarch a couple of years ago. Wow. Over the last three or four years I’ve read a lot of Margaret Atwood. I had thought I was indifferent to her — it seemed to have a certain cachet to be a bit dismissive of Atwood. But as I read deeply into her work, especially her narratives, but also a lot of her poetry, I developed a kind of awe for the deftness of her prose. What I said earlier about narrative positioning? I marvel at Atwood’s control of that — how subtly she shifts it with diction, the pronoun, sentence length. Others: Kroetsch, McCarthy, Proust. And Ta-Nehisi Coates is the most compelling rhetorician of race and culture right now — I try to read everything he writes.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Surf. I know, how first-world of me.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think I should have been a librarian. They are some of my favourite people.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Yearning.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Oooh! I get to repeat my love of George Eliot’s Middlemarch. It has such keen and unsentimental insight. And terrific sentences. This little passage is just one of many I copied into my Notes app on my phone:

“She opened her curtains, and looked out towards the bit of road that lay in view, with fields beyond outside the entrance-gates. On the road there was a man with a bundle on his back and a woman carrying her baby; in the field she could see figures moving--perhaps the shepherd with his dog. Far off in the bending sky was the pearly light; and she felt the largeness of the world and the manifold wakings of men to labor and endurance. She was a part of that involuntary, palpitating life, and could neither look out on it from her luxurious shelter as a mere spectator, nor hide her eyes in selfish complaining.”Film: Bela Tarr’s Satantango. I’m not even sure I liked it. It floored me with its audaciousness in length, in imagery, in enigma.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I have a historical novel thing-y that I haven’t really found my way into yet — it’s a project I have copious notes for, have done research in the field and in archives across Canada, and have sections written that may never be used. I also have this wacky little short narrative film I’m trying to figure out a way to produce — I call it a ficto-memoir, featuring a character who is not-I gets to surf.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 07, 2016 05:31

July 6, 2016

William Hawkins (May 20, 1940 - July 4, 2016)

As I announced a few days ago on the Chaudiere Books blog, legendary and much beloved Ottawa poet and musician

William Alfred Hawkins

died at the Queensway-Carleton hospital on Monday afternoon. As Joanne Wiffen wrote in an email: “Bill passed away peacefully this afternoon. He was not in pain.” [See the CBC article here, with an earlier CBC audio interview with him here; the Ottawa Citizen article here]

As I announced a few days ago on the Chaudiere Books blog, legendary and much beloved Ottawa poet and musician

William Alfred Hawkins

died at the Queensway-Carleton hospital on Monday afternoon. As Joanne Wiffen wrote in an email: “Bill passed away peacefully this afternoon. He was not in pain.” [See the CBC article here, with an earlier CBC audio interview with him here; the Ottawa Citizen article here]I’m still in shock. More than a few of us are. [Cameron Anstee posted this thoughtful recollection yesterday]

His health (but never his spirit) had been failing in recent years, including the introduction of oxygen tanks to assist with respiratory issues. He’s said for years that he needed new lungs. But with two different ambulance visits to the hospital over the past couple of weeks, what had been theorized as pneumonia ended up being an aggressive stage four colon cancer.

From 1964 to the early 1970s, William Hawkins was a considerable presence in Ottawa, from publishing poetry, composing songs for the band The Children (which included a young Bruce Cockburn) [and only released their first album a couple of years back], and organizing events at the infamous coffeehouse, Le Hibou, hosting poets, musicians and writers alike, including Leonard Cohen, Gordon Lightfoot, John Robert Columbo and Michael Ondaatje. He won an award from the Mayor, and pissed off as many people as he encouraged and influenced. As he explained in a 2008 interview: “I just dropped out sometime in 1971, when I woke up in the Donwood Clinic, a rehab centre in Toronto, with no idea how I got there, weighing 128 lbs and looking like a ghost in my six-foot frame.” His last book for quite some time, The Madman’s War, appeared in 1974, but for the most part, he quietly retreated from public life to drive a cab for Blue Line, where stories of seeing Bill became as rich and plentiful as tales of the Loch Ness Monster [Read an interview from around that time with Hawkins, here].

Hawkins’ exploits are as legendary as they are apocryphal, including tales of facilitating Jimi Hendrix’ recording of a Joni Mitchell performance at Le Hibou on his reel-to-reel (later recording Hawkins performing a new song on guitar at the after-party), a run-in with Mexican police at the Mexican-American border involving a pick-up truck of weed (and Trudeau’s subsequent interventions on their behalf), and a day-long reading at the site of a former hotel in Ottawa’s Lowertown [See my recent interview with Neil Flowers on the Northern Comfort anthology, an edited transcript of that reading, here]. Another story has Hawkins sitting on stage reading quietly to himself in a rocking chair during a performance of The Children at Maple Leaf Gardens, as they opened for The Lovin’ Spoonful. He hinted at a hardscrabble upbringing, including a stretch in a jouveile detention centre, for which he earned a small tattoo on his hand.

Hawkins’ exploits are as legendary as they are apocryphal, including tales of facilitating Jimi Hendrix’ recording of a Joni Mitchell performance at Le Hibou on his reel-to-reel (later recording Hawkins performing a new song on guitar at the after-party), a run-in with Mexican police at the Mexican-American border involving a pick-up truck of weed (and Trudeau’s subsequent interventions on their behalf), and a day-long reading at the site of a former hotel in Ottawa’s Lowertown [See my recent interview with Neil Flowers on the Northern Comfort anthology, an edited transcript of that reading, here]. Another story has Hawkins sitting on stage reading quietly to himself in a rocking chair during a performance of The Children at Maple Leaf Gardens, as they opened for The Lovin’ Spoonful. He hinted at a hardscrabble upbringing, including a stretch in a jouveile detention centre, for which he earned a small tattoo on his hand.Barely into their twenties, Hawkins and Roy MacSkimming raised funds to get themselves out to Vancouver for the sake of the infamous Vancouver Poetry Conference of 1963, asking friends and enemies alike for money to help him leave town. Once there, he was able to study with and engage with Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Charles Olson and Robert Duncan, returning home with an Olson edge and incredible energy, producing, reading and publishing, it seemed, non-stop for more than a decade. During that period, his poetry appeared on a series of poetry posters around town, in Raymond Souster’s seminal anthology New Wave Canada: The New Explosion in Canadian Poetry (Toronto ON: Contact Press, 1966) and A.J. M. Smith’s Modern Canadian Verse (Toronto ON: Oxford, 1967). His books include Shoot Low Sheriff, They’re Riding Shetland Ponies! (with Roy MacSkimming; 1964) [a book famously mentioned by Frank Zappa in an interview with Rolling Stone; Joni Mitchell had picked up a copy while in Ottawa, and she was apparently living with Steven Stills at Zappa's compound], Two Longer Poems (with Harry Howith; Toronto ON: Patrician Press, 1965), Hawkins: Poems 1963-1965 (Ottawa ON: Nil Press, 1966), Ottawa Poems(Kitchener ON: Weed/Flower Press, 1966), The Gift of Space: Selected Poems 1960-1970 (Toronto ON: The New Press, 1971) and The Madman’s War (Ottawa ON: S.A.W. Publications, 1974). His poems in New Wave Canada sat alongside the work of Daphne Buckle (later Marlatt), Robert Hogg, bpNichol and Michael Ondaatje, who later included his own “King Kong meets Wallace Stevens” poem in Rat Jelly (1973), influenced, perhaps, by Hawkins’ “King Kong Goes to Rotterdam.” [Seeother tribute poems, including one by Nelson Ball here, and one by myself; another tribute poem for William Hawkins, by Neil Flowers, recently appeared through above/ground press]

King Kong Goes to Rotterdam

Why now King Kong meMe silent seeker of the Rotterdam of pussycatsMe troubled watcher of St. Orlovsky’s bearI’m in the ice-bags of tomorrow’s girlMy endless aspirations of Holland won’t save meI’ve seen the blond girls of Rotterdam copulatingOblivious of world sorrowBut ecstatic for corduroy trousers

I wear corduroy trousersYet I am a billion miles from pigtails

Hawkins didn’t publish another book for thirty-one years, before I saw the publication of his second selected poems through my Cauldron Books series, Dancing Alone: Selected Poems (Fredericton NB: Broken Jaw Press, 2005) [See Roy MacSkimming’s introduction to the collection here]. A double album of the same name appeared a year later, including nearly two dozen covers of Hawkins’ songs by various friends and admirers, including Lynn Miles, Murray McLaughlin, Sandy Crawley, Ian Tamblyn, Suzie Vinnick, Neville Wells, Sneezy Waters, Bruce Cockburn and others, as well as a new song performed by Hawkins himself. Without Hawkins, Bruce Cockburn said, I never would have started writing songs.

Since then, there’d been a small resurgence of interest in Hawkins’ work, with the publication of a chapbook of recent poems, the black prince of bank street (above/ground press, 2007), as well as the release of Wm Hawkins: A Descriptive Bibliography (Ottawa ON: Apt. 9 Press, 2010) by Cameron Anstee, who also produced the chapbook Sweet & Sour Nothings (Apt. 9 Press, 2010), a “lost” poem from the 1970s, reissued for the sake of Hawkins’ appearance at Ottawa’s VERSeFest. Held together as a folio, Wm Hawkins: A Descriptive Bibliography lists Hawkins’ work over the years in trade, chapbook and broadside form, as well as a list of anthology publications. The small folio also included reissues of the infamous poetry posters of the 1960s. As Anstee wrote in the introduction:

The writing, of course, stands up today. His poetic accomplishments were consolidated in the 2005 selected poems, Dancing Alone. However, the details of his publishing intersect with a broad cross section of people and events that made invaluable contributions to the development of Canadian Literature. Shoot Low Sheriff was published in the wake of the famous 1963 UBC conference where Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Charles Olson and others influenced the next generation of Canadian poets. Ottawa Poems was published by Nelson Ball’s now legendary Weed/Flower press. Hawkins’ inclusion in the Raymond Souster edited New Wave Canada not only saw him published by Contact Press, but also published alongside early work by Michael Ondaatje, bpNichol, Victor Coleman and Daphne Marlatt (then Daphne Buckle) among a long list of others. See Roy MacSkimming’s excellent introduction to Dancing Alone for further description, but these details of Hawkins’ publishing life are important. They place him in significant currents and developments in Canadian poetry. Yet, the specific details of this publishing activity have remained scattered.

In 2015, editor Anstee saw the release of the thoroughly-researched The Collected Poems of William Hawkins (Chaudiere Books, 2015), a book that even included poems Bill had long forgotten. [You can read Anstee’s introduction in issue #11 of seventeen seconds, here; an interview with Anstee on the project here; see a video of Hawkins reading from the collection at the launch here; and copies of the book are available here]

William Hawkins was not only from Ottawa, but remained in Ottawa, influencing and celebrating the City of Ottawa during a period that had very few poets known outside of the city’s borders, and remarkably few avenues for publication. Two months away from his seventy-third birthday, William Hawkins became one of the first two inductees to the VERSe Ottawa Hall of Honour [Read a brief profile/interview I did with Hawkins around that time here]. The plaque we presented to to him included lines from the fourth poem of Ottawa Poems, that read:

What had she, Queen Victoria, in mind naming this place, Ottawa, capital?

Ah coolness, he said, who dug coolness.

This crazy river-abounding town where people are quietly following some hesitant form of evolution arranged on television from Toronto.

where girls are all possible fucks in the long dull summernights

& Mounties more image than reality.

After Noel Evans put together the rough manuscript of Dancing Alone, it was I who pushed to get it into print. For years, he would show up at my doorstep (Rochester Street, Somerset Street and McLeod Streets) and call from his cellphone, requesting I come out to his car for a visit. “Hey, my boy!” was his usual greeting. I could tell immediately that the publication of The Collected Poems of William Hawkins was exciting to him because, for the first time, he actually came into the house, oxygen tank and all. Part of what he liked about the book (despite considering the whole project suspect) was that he was finally able to dedicate a book to his mother.

After Noel Evans put together the rough manuscript of Dancing Alone, it was I who pushed to get it into print. For years, he would show up at my doorstep (Rochester Street, Somerset Street and McLeod Streets) and call from his cellphone, requesting I come out to his car for a visit. “Hey, my boy!” was his usual greeting. I could tell immediately that the publication of The Collected Poems of William Hawkins was exciting to him because, for the first time, he actually came into the house, oxygen tank and all. Part of what he liked about the book (despite considering the whole project suspect) was that he was finally able to dedicate a book to his mother.He once told me that our apartment building on McLeod Street housed a brothel in the 1970s. He knew the building from driving cabs, and driving the girls over. He had the wistful chuckle of someone who’d once been quite the troublemaker, enjoying the stories he knew were long behind him.

We last spoke about two weeks ago, when Bill called to purchase more copies of the selected poems, and to complain about his latest hospital stay, which included having to get new blood.

Ah, hell. Bill was a friend of mine. His energy was always positive and infectious, even if he hadn’t much. His performances were incredible, but, at least in his later years, took enough out of him that he required days to recover. When he read as part of his Hall of Honour ceremony, he held a room like I’ve rarely seen, before or since.

I’m really going to miss him.

[See also: CBC Radio's All in a Day yesterday featured Sneezy Waters and Bruce Cockburn talking about William Hawkins; CBC News talking to Sneezy Waters yesterday; and an obituary in the Ottawa Sun; and did you know CBC did a profile on Bill in 2008?]

Published on July 06, 2016 05:31

July 5, 2016

Laura Walker, story

if the story like a river. loose and fretful, twine. if a story with debris and froth, pulling from the banks as it comes, never the same river twice, step in and be renewed. if glass-bottomed boats and red-dotted fishes. if another line just under the surface, if you can’t see without drowning, if sometimes in storm, sometimes becalmed. if each person carries her own boat, dam, leaf. cutting its own way through or swept along and over the cliff, story as waterfall and prismed light, story as gravity.

Berkeley, California poet Laura Walker’s [see her "12 or 20 questions" interview here] fifth poetry collection, following

swarm lure

(Battery Press, 2004),

rimertown/ an atlas

(University of California Press, 2008), bird book (Shearsman Books, 2011) and

Follow-Haswed

(Apogee Press, 2012) [see my review of such here] is story (Berkeley CA: Apogee Press, 2016). Composed as a sequence of stand-alone prose fragments, story provides an enormous amount of narrative detail, accumulating story upon story, thickening the length and breadth of it, but the thread of her story still manages to remain elusive. As she writes: “a story as skin. boundary, temperature, delineation. what she was told and what she was making fuzzy scratches in the dark.” Each of her prose poems encapsulate a sequence of small moments, extending the collection via accumulation, but one that refuses to remain static, or straightforward. “[T]o make a story move someone has to give,” she writes, as Walker engages with the mutability and contradictions inherent in storytelling. Just what kind of story is she attempting to tell?

Berkeley, California poet Laura Walker’s [see her "12 or 20 questions" interview here] fifth poetry collection, following

swarm lure

(Battery Press, 2004),

rimertown/ an atlas

(University of California Press, 2008), bird book (Shearsman Books, 2011) and

Follow-Haswed

(Apogee Press, 2012) [see my review of such here] is story (Berkeley CA: Apogee Press, 2016). Composed as a sequence of stand-alone prose fragments, story provides an enormous amount of narrative detail, accumulating story upon story, thickening the length and breadth of it, but the thread of her story still manages to remain elusive. As she writes: “a story as skin. boundary, temperature, delineation. what she was told and what she was making fuzzy scratches in the dark.” Each of her prose poems encapsulate a sequence of small moments, extending the collection via accumulation, but one that refuses to remain static, or straightforward. “[T]o make a story move someone has to give,” she writes, as Walker engages with the mutability and contradictions inherent in storytelling. Just what kind of story is she attempting to tell? she was seven. she was never seven. she stood on a small hill and looked behind her; she became her own character; she viewed the world through glass. the touch of sheets against her legs fades like vowels in ink, throb of a piano through a wall. a mattress as it sputters toward flame; desperate dogs down each man’s throat, eyes as big as branches. her eyes were glass where they could not see.

In an interview posted at Thermos on January 1, 2015, she discusses the project, still (then) very much a work-in-progress:

I’m in the last stages (I think) of a manuscript I’ve been working on for about a year. It’s a series of prose blocks circling around ideas of story and its manifestations, weaving characters, fairy tales, family stories, and memories, both “real” and created. Sometimes I say it’s as close to writing a novel as I’ll ever get, which is not very close. But there was something that felt “novelistic” for me as I wrote it, for example the ways in which I needed to erect a structure and simultaneously keep it aloft while turning my attention elsewhere—like putting up a circus tent and drawing something obscure and difficult on the floor at the same time. Destined for failure but exhilarating too.