Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 338

July 23, 2016

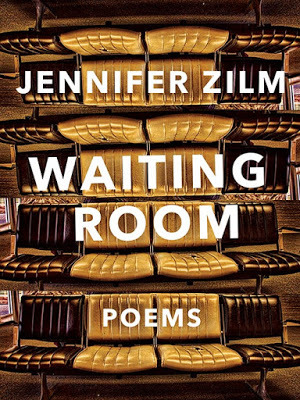

Jennifer Zilm, Waiting Room

My review of Jennifer Zilm's Waiting Room (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2016) is now online at The Small Press Book Review.

My review of Jennifer Zilm's Waiting Room (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2016) is now online at The Small Press Book Review.

Published on July 23, 2016 05:31

July 22, 2016

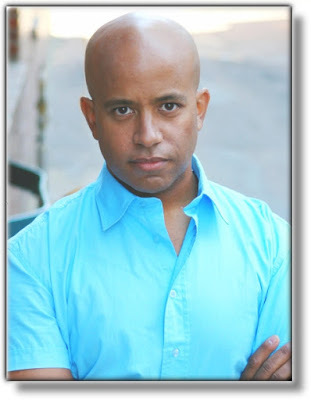

U of Alberta writers-in-residence interviews: Minister Faust (2014-15)

For the sake of the fortieth anniversary of the writer-in-residence program (the longest lasting of its kind in Canada) at the University of Alberta, I have taken it upon myself to interview as many former University of Alberta writers-in-residence as possible [see the ongoing list of writers here]. See the link to the entire series of interviews (updating weekly) here.

Minister Faust is a novelist, print/radio/television journalist, blogger, sketch comedy writer, video game writer, playwright, and poet. He also taught high school and junior high English literature and composition for a decade.

Minister Faust is a novelist, print/radio/television journalist, blogger, sketch comedy writer, video game writer, playwright, and poet. He also taught high school and junior high English literature and composition for a decade.He was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 2014-15 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you’d already produced fiction, plays, stage writing and sketch comedy, as well as video games. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: I was comfortable with my writing and I appreciated the opportunity to teach people, which I had done for ten years.

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Were you working on anything specific while there, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: I had the chance to plan and research several projects, and spent a great deal of time working with local writers on meeting their goals, as well as promoting local artists through the Authorpaloozas and launching MF GALAXY to talk with writers about the business and craft of writing.

Q: Were there any encounters that stood out?

Everyone stood out. One person I’d like to mention Tweeted that he was grateful for all the help I’d given him on his story, which had gotten published. My advice was, “Don’t change a word.”

Q: Was this your first residency?

A: Yes.

Q: The bulk of writers-in-residence at the University of Alberta have been writers from outside the province. As an Edmonton-based writer, how did it feel to be acknowledged locally through the position?

A: I strongly appreciated the opportunity to work with local writers to help them build their skills and their reach, and to publicize the outstanding literary community we have here.

Published on July 22, 2016 05:31

July 21, 2016

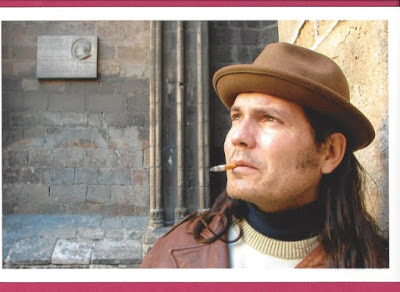

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Randy Lundy

Randy Lundy

is a member of the Barren Lands (Cree) First Nation, Brochet, MB. Born Thompson, in northern Manitoba, he has lived most of his life in Saskatchewan. He grew up near Hudson Bay, SK, just a stone’s throw from the confluence of the Fir, Etamomi, and Red Deer Rivers.

Randy Lundy

is a member of the Barren Lands (Cree) First Nation, Brochet, MB. Born Thompson, in northern Manitoba, he has lived most of his life in Saskatchewan. He grew up near Hudson Bay, SK, just a stone’s throw from the confluence of the Fir, Etamomi, and Red Deer Rivers.He completed a B.A. (Hons.) and an M.A. in English at the University of Saskatchewan, where he studied religion, philosophy, and Indigenous literatures, completing a thesis on the plays of Tomson Highway.

He has published two books of poetry, Under the Night Sun and Gift of the Hawk. 2016 will see the publication of a third books of poems, Blackbird Song.

His poetry has been widely anthologised, including in the seminal texts Native Poetry in Canada: A Contemporary Anthology and An Anthology of Canadian Native Literature in English . His poetry has appeared in anthologies in the United States, New Zealand, and Australia.

He has also published scholarly articles on writing and on the work of Tomson Highway and Daniel David Moses.

Randy writes short stories and is currently working on a manuscript, Certainties, for publication.

Randy teaches Indigenous literatures and creative writingin the English Department at Campion College, University of Regina.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?Well, my first book, Under the Night Sun, probably only inflated my ego. But it did offer me the opportunity to teach creative writing, which has been a great blessing to me. Some amazing students who have taught me more than I ever knew about writing. It's something I have been doing now since 2000. You know, when the book came out, I thought the writing was amazing. Now (and that was in 1999), I look back at it and see that there are only a couple of decent poems. I am glad for those decent poems, but I guess I have just matured a bit. I hope.

I did some bad things in Saskatoon when I was going to university, just silly young man things, and I fell in and out of love and all that stuff is in that book.

Under the Night Sun and Gift of the Hawk are composed of lyric poems. I know that's unfashionable these days, but it's what I can do. Blackbird Song will be more of the same. My first teachers were the critters both in and around where I grew up. Those and the trees and stones and rivers etc. After those teachers, it was Archibald Lampman's nature sonnets and then later Patrick Lane, Atwood, Cohen, and the whole crew.

In the midst of editing the first book, Patrick suggested I was a bit of a romantic, and of course he was right. Still am, always will be.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?Good question. Well, I understand how the long sentences one can construct in prose might be seen to represent a river or a ridge, I used to sit on the rocks in the middle of the Red Deer river and listen to the water running. To me, it sounded full of syllables, but short, tumbling. The bird calls were not prose but poems.

I guess I am still trying to imitate that as best I can.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?Writing is not a project me. It’s just how I live. So I don’t ever stop writing, in my head that is. Getting it down on paper is always hard, and then comes the endless process of revision. That’s tough business. Luckily for me, if not for the reader, generally the first drafts are fairly close to the final version.

But that’s an oversimplification. First drafts are carried inside my bones before they ever become first drafts. Everything else gets thrown away.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?Poems always begin with an image that I have to find the idea to express. Or it’s the idea I have to find an image to express. The two are constantly united, melded.

I am definitely a writer of shorter pieces (at least for now) that combine into something I could not anticipate. I know the use of the term ‘organic’ is way to overused, but the work does figure itself out. Then you just have to look and listen.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I love reading to people. And I love being read to. Reminds me of childhood. And I guess like many I like being the center of attention and having eyes on me.

Then again, that’s not what it’s about. To refer to Patrick Lane again: “It’s the poem that matters.” So if readings keep me from writing or make me forget why I am doing it, then that’s a problem.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?Theoretical concerns. Well, I have a problem with post-structuralist / post-modern theories that would have it that language is about language and never reaches the world. I think it’s malarkey. The same world, the same earth, that gave birth to us gave birth to our various languages. Language is a marriage between human consciousness and the world.

Of course, I am Cree (not to the exclusion of my paternal ancestors) and I am interested in the earth and all of its various creatures because they are truly our kin.

So for me, I am interested in how we are formed by the world. We’re just a part of it, looking from inside it. If that doesn’t point us toward current questions, then we are in deep trouble, as we seem to be.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?Well, we are certainly not “the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” as Shelley put it in his defense of poetry. I think our roles as writers should be to engage people in dialogue.

I do not really feel qualified to answer the question, but I am certain that writers have a role. Maybe many would disagree.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?Working with an editor is definitely difficult and essential. For my first two books I was lucky to work with Patrick Lane and Daniel David Moses, and I learned much from each of them. Different things, but I learned much. Important to get out of our own heads, I suppose.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?This is turning into a Pat Lane tribute, but the poem is what matters so just get your own ass out of the way. Look and listen. Another of my favourite poets, Jane Hirshfield, has a chapter in her book Nine Gates titled “The World Is Large and Full of Noises,” so just shut up dummy and listen.

And I guess I have to credit the Buddha for letting me know to just be where you are.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I don’t really have a writing routine, except I walk and look and listen and see what is offered to me. A typical day begins with a cigarette, coffee, getting the dogs fed and watered, and then rushing off to teach. The dogs are good people. They have taught me much about what it means to be human.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?Inspiration. Well, of course, one of the meanings is to breathe in, rather than expire. So I turn to the birds—the merlins and doves and hawks. Also, I turn to writers I respect: Louise Gluck, Joanna Klink from UMontana, and especially Charles Wright. I cannot even get through a single Charles Wright poem without having to sit down and write. Mostly I just steal from him.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?Hmm, well, the smell of freshly baked bread in my Irish grandmother’s kitchen. My Irish kohkum, Reta, always was and is my home. And the smell of garbage in the burning barrel at my aunt and uncle’s farm north of Hudson Bay. Old Spice aftershave on my father.

And the “fragrance” of the bush in the spring.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Nature I’ve said enough about. I’m starting to sound like a pagan. Guess I must be one.

Music? Don’t get me started. I like hand drum music, Delta blues, outlaw country, to name a few favourites. Science and visual art I understand are indispensable, but I don’t really understand those disciplines. The kinds of music I enjoy celebrate the rhythms of the natural world and humans and human bodies as part of that.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?I’ve already been name dropping here, so I’ll try to keep this brief and mention a few folks I haven’t already. There are a great many damned fine Indigenous writers I would be remiss not to name: Maria Campbell, Louise Halfe, Gregory Scofield, Armand Ruffo, Linda Hogan (whose book The Book of Medicines should be required reading for poets), Sherwin Bitsui.

Also, I have to name Gary Snyder, Tim Lilburn, Don McKay, Jan Zwicky, Sheri Benning. Also Don Domanski is fantastic.

Recently bumped into a small book by Elena Johnson, Field Notes for the Alpine Tundra, which is a really special book.

Probably I should stop there before I get carried away.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Climb Macchu Picchu, visit the Deer Park where Buddha had his enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree, have dinner with Pablo Neruda and Jean-Paul Sartre—none of which are likely to happen.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?Any other occupation? Stand-up comedian, graffiti artist, whitikow, or Professional Trickster.

If I had not ended up being a writer, I would have ended up working in the bush or at a mill in Hudson Bay. The economy wouldn’t have kept me gainfully employed, so then I would have ended up drinking too much and smoking too much weed.

Maybe this sounds silly, bit I feel like writing and teaching are vocations for me. Just what I should be doing.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?Oh heck, I think I just answered that. Nothing else I wanted to do.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?The last great book I read was David Hinton’s Hunger Mountain: A Field Guide to Mind and Landscape. Last great film I watched was something on Netflix: Jumbo Wild , about the competing interests of development and natural / spiritual integrity.

19 - What are you currently working on?Well, new manuscript of poetry trying to explore the connections between Indigenous sensibilities, Buddhism, and the nature of memory.

That and some short stories, which I am just fooling around with because for me it’s a new genre and I don’t feel like I should know what I am doing in the same way I put myself under pressure when trying to write a poem.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 21, 2016 05:31

July 20, 2016

Ongoing notes: the ottawa small press book fair (part two,

Did you see my prior series of notes here? Or, really, my notes from the fair prior to that? I have so many notes on so many things. Should I even possibly start thinking about the dates for the fall fair? So much to do, so much to do.

[Kyp Harness, listening intently to Claire Farley at the Canthius table] Ottawa/Toronto ON: The second issue (spring/summer 2016) of Canthius, a journal of “feminism & literary arts” [see my recent interview with co-editor Claire Farley at Queen Mob’s Teahouse], includes, at the offset, a short note from the editors:

[Kyp Harness, listening intently to Claire Farley at the Canthius table] Ottawa/Toronto ON: The second issue (spring/summer 2016) of Canthius, a journal of “feminism & literary arts” [see my recent interview with co-editor Claire Farley at Queen Mob’s Teahouse], includes, at the offset, a short note from the editors: As editors of a new literary journal, we are still negotiating how best to promote gender equity. While our association with feminism could obligate us to publish works with overtly feminist themes, we’ve opted instead to offer a diversity of women and genderqueer writers space to share experiences and perspectives, no matter what those may be.

Now that they’ve two issues of their semi-annual journal under their belt (and seeking work for a third), one can’t help but be impressed by the clarity of vision editors Cira Nickel and Claire Farley have for Canthius , a journal of poetry, fiction and visual art. This new new issue includes new writing by an impressive list of writers both new and emerging, including Catriona Wright, Jacqueline Valencia, Sandra Ridley, Chuqiao Yang, Frances Boyle and Mary Ma, as well as artwork by Mary Grisey. In a certain sense, it’s far too easy to produce a first issue: the hard part is in producing a second, and a third; this becomes even more difficult without having a clear sense of what you wish to accomplish before you even begin, and their mandate is focused, open and incredibly straightforward, even as they, as they say, still work to negotiate the ways in which they can assist in promoting writing, thinking and conversation. As they infer in their introduction, if one wishes for a proper conversation of any sort, one requires the input of more than a select few.

We fail to name this right / without the wordsFor lapsing / lilies / wilted / in the beginningWind caught nothing / but your leaf unfurledTo fall. (“Dirge,” Sandra Ridley)

Given the limitations of a semi-annual journal, they’ve also been opening up their blog for further materials, including notifications, interviews, poems and non-fiction. So far, they’ve held launches for each issue in both Ottawa and Toronto (where each of the co-editors live). It will be interesting to see just how this journal continues to grow over the next couple of years.

[Meagan Black, sitting the Arc Poetry Magazine table]

[Meagan Black, sitting the Arc Poetry Magazine table] Toronto ON: From Jim Johnstone’s Anstruther Press comes Toronto poet Jessica Popeski’s Oratorio (second edition, thirty copies; just how small might the original run have been, I wonder?), the first of two chapbooks the press produced by her in 2015 (the other, which I have not seen, being The Wrong Place ). According to her online bio, Popeski is a Classical Voice and Creative Writing graduate from Brandon University, and her dense and dexterous lyrics are heavy with not only a musical tone, but musical language (and even the occasional musical score). Just listen to the opening of the poem “Home Visit,” that reads: “The cat curls a lick-wet paw behind an ear, makes a straw- / skinny mew for milk. String-darned socks smoke like kippers / on the radiator, space heaters strategically sprinkled.” While certainly not pretending to be a language poet gymnast, Popeski isn’t writing a complete straight line, either, allowing her phrases and sentences the occasional pop and sing, allowing each line a bounce in its step.

Mother-in-Law’s Tongueon the counter, reeking

Lysol. Middling greenrug moss between toes.

Wall, cerulean sky.Cosmos contained in a

computer screen square.Blue-headed vireos

belong in books, andruby-crowned kinglets,

white-breasted nuthatches.Aurora Borealis clotting

over prairie suburb sprawlwill be watched on television. (“Last Child in the Woods”)

With Oratorio edited by Dionne Brand, I’m curious to know if Popeski’s second chapbook was as well; and if a debut full-length collection (whether by McClelland and Stewart, where Brand edits, or anywhere else) might be far behind.

Published on July 20, 2016 05:31

July 19, 2016

Lucy Ives, The Hermit

To experiment with every kind of prose imaginable, e.g., the proses of America. I ask, What is the purpose of clarity, beyond description? Clarity, but to what end? The exquisite prose of Melville, of—what is totally different and yet feels related—Rousseau. (“33.”)

I’m happily startled (but not entirely surprised) by just how delightfully compelling and complex New York City writer Lucy Ives’ most recent title is, a small book titled The Hermit (The Song Cave, 2016). Composed in tight prose and full sentences that collage together into a larger coherence, The Hermit exists in an intriguing space that is part-poem, part-essay and part-novel, all blended together into an exploration of self, narrator and character, elements of dreams, lists and journal-entries, logic and the form of the novel (and prose-works generally) and even a thread that floats through one of the characters from A Nightmare on Elm Street. As she writes in the “Notes” at the back of the collection:

The title of the book bears some explanation. Of course, in entry 51, a hermit appears. But this is only a hermit in a work of art. I’m not sure, at any rate, what a hermit is today. Strangely, the hermit I have in mind is most closely or accurately figured by the character Nancy Thompson, as portrayed by actor I won’t spoil what occurs in “entry 78” (an entry that feels visibly distinct from the rest of the book), but the final line in the book, from “80.” reads: “I do not know for how long any of the characters in this book can persist as characters.” I think I very much like the idea that Ives is uncertain of the lives of the characters she has included here (I hesitate to automatically refer to them as “her” characters), and just how long they might survive, potentially, beyond the bounds of the completed book. She suggestion is that she suspects they should or otherwise would, but isn’t sure. I wonder, does she include the narrator as one of her characters, also? Do they include, for example, her references to, readings of and/or quotes by Kathy Acker, Charles Olson, George Oppen and Houellebecq?

I want to write an essay about the novel as a site of novelty, where the preposition “Anything can happen” is somehow tested. (“15.”)

The Hermit follows her books Orange Roses (Ahsahta, 2013) [see my review of such here], The Worldkillers (Ann Arbor MI: SplitLevel Texts, 2014) [see my review of such here], and the novel nineties (Little A, 2015). Her full-length novel, Impossible Views of the World, is due next spring with Penguin.

I discover that writing, as a profession, is about putting oneself into a constrained position, from which there are limited means of escape. The undertaking is not about the words themselves or even some technical skill distinct from survival. One must possess only the ability to tolerate a given position long enough to make it intelligible to others. (“52.”)

The Hermit is set in eighty short, numbered prose-sections, and I’m fascinated by how Ives writes a book that, in part, tells us how to read it, as her forty-third entry, in full, reads: “One must work, perhaps for some time, to see scenes.” The Hermitreads as an essay/novel-through-accumulation, allowing the short semi-standalone scenes to collect and reshape via the reader, much in the same way, perhaps, as Sarah Manguso’s Hard to Admit and Harder to Escape (McSweeney’s, 2007), a book that heavily influenced my own The Uncertainty Principle: stories,(Chaudiere Books, 2014). In the entry immediately prior to the forty-third, she also offers: “An essay occurs in time like dog years, where it isn’t a task of reasoning so much as something that befalls one. I perhaps don’t read or write enough and yet always feel like I am reading, like I am writing.” Or just a bit earlier, as she writes as part of “67.”:

The Hermit is set in eighty short, numbered prose-sections, and I’m fascinated by how Ives writes a book that, in part, tells us how to read it, as her forty-third entry, in full, reads: “One must work, perhaps for some time, to see scenes.” The Hermitreads as an essay/novel-through-accumulation, allowing the short semi-standalone scenes to collect and reshape via the reader, much in the same way, perhaps, as Sarah Manguso’s Hard to Admit and Harder to Escape (McSweeney’s, 2007), a book that heavily influenced my own The Uncertainty Principle: stories,(Chaudiere Books, 2014). In the entry immediately prior to the forty-third, she also offers: “An essay occurs in time like dog years, where it isn’t a task of reasoning so much as something that befalls one. I perhaps don’t read or write enough and yet always feel like I am reading, like I am writing.” Or just a bit earlier, as she writes as part of “67.”:Make an illogical jump—dissociation—but, then, imperceptibly—so, quickly—return to render it logical before anyone has seen. In this way, you may seem to improve upon reason.

Published on July 19, 2016 05:31

July 18, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Claudia Casper

Claudia Casper

is the author of three novels:

The Reconstruction

,

The Continuation of Love By Other Means

, shortlisted for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, and

The Mercy Journals

. She is writing a screenplay adaptation of The Reconstruction for a 3D feature film co-production. She has taught writing at Kwantlen Polytechnic University and been a long-time mentor for Vancouver Manuscript Intensive. Claudia lives in Vancouver, BC.

Claudia Casper

is the author of three novels:

The Reconstruction

,

The Continuation of Love By Other Means

, shortlisted for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, and

The Mercy Journals

. She is writing a screenplay adaptation of The Reconstruction for a 3D feature film co-production. She has taught writing at Kwantlen Polytechnic University and been a long-time mentor for Vancouver Manuscript Intensive. Claudia lives in Vancouver, BC. 1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

a) My first book, The Reconstruction, after its first rejection, was the cause of a bidding war. It was like being queen for a day. When the novel came out I was seven and a half months pregnant, and so all the attention it received (television and radio interviews, starred reviews in Publisher’s Weekly and Kirkus, reviews in the NYT, the Independent, etc.) came at me through a kind of bovine haze. I don’t think I understood quite what it meant. I was overwhelmed. I have a Goldilocks and the Three Bears observation about life when you’re a human – everything is either too much or not enough. The times when we get just the right amount of anything, stimulation, satiety, demand or love, are very rare. The introvert side of me was relieved to go back to the quiet pleasure/torment of writing the next novel.

b) My first novel was about evolution, the second reproduction and gender conflict and this new one, The Mercy Journals, is about war and our future as a species, so they are thematically linked in a biological progression – past, present and future. With The Continuation of Love by Other Means, I moved into a swifter moving, linear narrative with sparer prose, and in The Mercy Journals I worked even more assiduously to cut anything that wasn’t absolutely necessary to the story. The first person narrator was new for me, as was the epistolary form (the story is written as two journals) and the constricting rigors of the form were both thrilling and brain-breaking. My hope is that readers experience this novel as though Allen Quincy, the main character, were whispering his story directly in their ears.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I started writing short stories, but the ideas I wanted to explore quickly became novel-length. You can do anything in the wide, open spaces of a novel, as long as it isn’t boring and the work achieves that slightly miraculous wholeness when the elements start pinging and reverberating against each other, creating a kind of chain reaction that heats up emotions and intensifies meaning.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

My process is inefficiently organic. The main idea underlying a novel shows up first, then characters and scenes I know will have to be in. I start taking notes on cue cards, pads of paper, cellphone, desktop, occasionally writing scene fragments, and when I have enough I put them in a folder. This goes on for a year or several, usually when I am finishing my previous novel. I start researching and reading on the subject. When the previous work is finished, I reread all my notes, pack them into my head, and begin a first draft. That takes about a year, and that first draft shows me what the shape of the novel will be, and probably about half of it stays. Then the years of rewriting and further research begin.

4 - Where does a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The Reconstruction started with a desire to know who Lucy (the nickname given to the 3 million-year-old fossil of a human ancestor found in Ethiopia) was and what it meant to a woman today that she was descended from her. My second novel started with a desire to understand the gender conflict through the biological lens of reproduction and the emotional lens of the all-consuming love a parent feels for their children. My third novel, The Mercy Journals, arose from a desire to deconstruct the self-righteous rhetoric nations wrap themselves in during violent conflict and a sense that unless we accept that murderous, genocidal behaviour is a part of who we are as a species, we can never really hope to control it. I wanted to understand PTSD as a fundamentally human reaction to horror and I wanted to understand the implications of climate change for our culture. My thinking about who we are as a species and where we might be headed evolves with each new book.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. They’re when you get to actively experience how readers are receiving your work, how the words make the leap across the void to other minds. They’re not particularly part of my creative process, except perhaps during the final edit when I anticipate reading aloud. Until then my tuning fork is up for the internal rhythm of reading, more than the rhythm of speaking aloud.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

One question foremost in my mind is what is the role of the novel in the age of the internet and the moving visual image. When we are all deluged with content, what can the novel offer us, uniquely, to lay claim not just to our time, but an even more scarce resource, our attention? I wondered whether the novel’s relevance to society was waning and posed myself the question, what does the novel do better than any other medium? Two things came to mind immediately. A novel takes us into the interior world of a character with an intimacy no other medium even comes close to achieving, and lets us share the experience of the meaning of that life. Also, novels weave in threads from myths, fairy tales and other literary works, both bringing them forward in time in a way that deepens our present existence, and reconnecting us backwards with a direct link to the roots of our culture. The Mercy Journals weaves threads from Cain and Abel, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Cinderella and Hamlet.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

That is to be determined by the larger culture. The writer does not have any control over what happens with a book other than writing it.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Generally, I have found working with editors to be exciting and joyous – they are close companions after years of solitude, working to make your book the best it can be. Working with Brian Lam at Arsenal Pulp on this novel was a pleasure – he had a clarity, assurance and attentiveness that calmed any uncertainties I had. Susan Safyan, who worked more closely on the text, was also a delight – she caught inconsistencies and gaps of logic that had eluded me. I felt lucky. However, I have also had unhelpful experiences – where I lost a year trying to adapt a manuscript to an editor’s notes when ultimately we were not working toward the same book. I then had to spend months sorting through the changes I thought added to the book, cutting the rest. The process did not hurt the final manuscript because I had a clear idea of what I wanted the book to be, but it probably wasted precious time from my creative output. My instinct, though, is to always listen to an editor and see if there’s a way to move forward with their comments in a way that will improve the book. There’s no point in having your ‘perfect’ manuscript in a drawer, unseen by anybody but a few friends and relations.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Recently, I have come to realize how much I hate advice. As someone who has given profligate amounts of unasked for advice in my lifetime, I am trying to mend my ways (but it’s hard, almost as hard, though not quite, as giving up complaining, which I have no intention of doing). Advice, subversively, seeks to place the giver above the receiver. That being said, I do like something Jean Cocteau said, and I paraphrase – what people criticize you most for in your art, that is your talent, do it even more.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (fiction to non-fiction)? What do you see as the appeal?

I feel unleashed in different ways in fiction and non-fiction. I love the freedom and the wild, open spaces of fiction, where I can build something completely new and unique as long as it’s compelling. Then I love being able to express ideas explicitly in non-fiction, to articulate thinking that drives the fiction. Writing book reviews is a way to give back to the professional community and to further articulate my thoughts on what makes fiction truly sing. Reviewing non-fiction books on anthropology, feminism, war, allow me to tangle with points of view on subjects I am impassioned by.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My writing routine has changed over time. Right now, I get up at 7:30, I have coffee, I dick around on the internet for an hour or so, then I write, refuelling with coffee until I get hungry, usually around 1. I eat something with the idea of keeping it light enough that the blood doesn’t completely leave my brain and write for an hour or two more. After that, my mind is spent for the day, refilling during sleep. I adore the feeling of having uninterrupted writing time.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

My writing never gets stalled, which is a surprising admission given how long it takes me to finish a book. When I sense resistance in the text, I get a separate pad of paper and write out questions to myself. I figure out what avoidance is stumping me. A lot of fiction writing comes down to the asking and answering of questions.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Coffee.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

One of the flash cards I had pinned to my bulletin board above my desk as I wrote The Mercy Journals was, embarrassingly, “write like a Billy Idol base line.” Science and nature influence all my work.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Important for my work over time are the writers (among others): Kurt Vonnegut, Marilynne Robinson, J.M. Coetzee, Anita Brookner, E. Annie Proulx, Carlos Fuentes, David Mitchell, Dennis Lehane.

Anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy’s work has been important in all three novels. Her research and writing has informed and stretched my thinking about evolution, reproduction, violent conflict, and altruism.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write three more books. Boost my inadequate French to true fluency. Keep chickens, maybe a pygmy goat.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I like the life I’m living, but if I got an extra life, I’d choose to be an Italian opera singer.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I think everyone starts off writing – poems, diary entries, school assignments. I just didn’t stop.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Voices from Chernobyl by Svetlana Alexievich. Fascinating non-fiction narrative form using only the voices of people she interviewed, but organized in a way that builds meaning – she reveals the soul of the post-Soviet citizen. Interestingly, as a writer who only uses real people’s voices, she just won the Nobel Prize for literature. The last great film I saw, well there are two. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night , by director Ana Lily Amirpour. This is a very cool cult film, an Iranian vampire spaghetti western, by a hot new talent. Her next film is a post-apocalyptic cannibal love story set in a Texas wasteland, starring Jason Momoa, Jim Carry and Keanu Reeves. This week I rewatched Wild Tales, by Argentinian filmmaker, Damian Szifron. Very dark humour, lots of energy, just as good the second time.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I can’t talk about the next novel yet, though I have a sense of the form, naturally I have the theme, I have some scenes, and some of the characters.

I am co-authoring a screenplay of my first novel, The Reconstruction, for a France/Canada 3D feature film. I just came back from an intense three weeks of writing with the producer/director and director/cinematographer in what was a three-way mind meld in French and English. There were times I felt like a stunned cow just standing, staring at a wall, the level of concentration was so demanding. But that’s the beauty of collaboration – you bull through (to use another bovine trope) – and are lifted by the other minds. None of us seemed to hit the wall at the same time. I am fascinated by the differences in the way a story is told in film as opposed to a novel. You cannot use a letter, for example, that one of the characters has written – that’s ‘telephoning’ it in. Very bad.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 18, 2016 05:31

July 17, 2016

my father, at seventy-five (a report,

My father turned seventy-five years old on June 26 [left: Uncle Don, Kris Jensen, Aunt Pam + Dad], and my sister and I organized and hosted a surprise birthday party for him on the homestead. Originally, our plan included us descending upon the farmhouse on the morning of his birthday, once he was off to his usual Sunday morning church service. It was a good plan; it was a solid plan, but one thrown off slightly by the fact that his birthday coincided with the once-a-year multi-church service held not only an hour earlier at another location, but a service with a parking lot too far from the building, causing my father to decide to stay home, instead. Hmmmmmm.

My father turned seventy-five years old on June 26 [left: Uncle Don, Kris Jensen, Aunt Pam + Dad], and my sister and I organized and hosted a surprise birthday party for him on the homestead. Originally, our plan included us descending upon the farmhouse on the morning of his birthday, once he was off to his usual Sunday morning church service. It was a good plan; it was a solid plan, but one thrown off slightly by the fact that his birthday coincided with the once-a-year multi-church service held not only an hour earlier at another location, but a service with a parking lot too far from the building, causing my father to decide to stay home, instead. Hmmmmmm. [Jule, with Aoife] Still, the day went along marvellously. We’d managed to secure an invitation to his best friend and former neighbour (when they were boys) Kris Jensen, who flew in from Vancouver Island and was already at the house having a visit when Christine and I arrived with the girls around 10:30am. Over the next hour or so, another thirty people arrived, from neighbours and other local friends to family from Ottawa, Arnprior and beyond, including two of his older cousins, Jule and Audrey (daughters of my great aunt Jessie), and my Aunt Pam and Uncle Don, in from Woodstock. Once we passed noon, a few others even arrived from the church service, such as the Rev. Jim Ferrier (whom we quite like).

[Jule, with Aoife] Still, the day went along marvellously. We’d managed to secure an invitation to his best friend and former neighbour (when they were boys) Kris Jensen, who flew in from Vancouver Island and was already at the house having a visit when Christine and I arrived with the girls around 10:30am. Over the next hour or so, another thirty people arrived, from neighbours and other local friends to family from Ottawa, Arnprior and beyond, including two of his older cousins, Jule and Audrey (daughters of my great aunt Jessie), and my Aunt Pam and Uncle Don, in from Woodstock. Once we passed noon, a few others even arrived from the church service, such as the Rev. Jim Ferrier (whom we quite like). [Don and Dad] At 4:10am, on Sunday, June 26, 1941, our father was born in the log house across the road from the homestead, escorted by Doctor B.B. MacEwan and Nurse Edma MacEwan. There is a story I’ve been told about my grandfather, a day after my father was born, bellowing into the telephone at his sister-in-law, Harriet Campbell: “When are you coming over to see my son?”

[Don and Dad] At 4:10am, on Sunday, June 26, 1941, our father was born in the log house across the road from the homestead, escorted by Doctor B.B. MacEwan and Nurse Edma MacEwan. There is a story I’ve been told about my grandfather, a day after my father was born, bellowing into the telephone at his sister-in-law, Harriet Campbell: “When are you coming over to see my son?” My father was actually the second of my grandparents’ children, as Johnny and Ellen gave birth to a daughter some eighteen months earlier, who died less than a day later due to complications (something Audrey reminded me of, on the day, in case I didn’t know; a story she’d heard from her mother, saying “The only time she’d seen Johnny cry.”). It was my grandmother who initially informed me about her; by the time I’d any follow-up questions, she’d been gone for years.

[above: Kris, speeching; left: my cousin Kim with Aoife] At seventy-five, he’s outlived a number of his father’s generation. His uncle Roddie died at sixty-six, Donald at fifty-seven and Johnny himself at sixty-two, either taken through cancer or the heart, both of which my father has survived. His mother might have lived to seventy-nine, his Uncle Scott to eighty-one and Aunt Belle to eighty-three, but Donald’s widow, Jesse, still holds the record, managing a matter of weeks away from one hundred and six.

[above: Kris, speeching; left: my cousin Kim with Aoife] At seventy-five, he’s outlived a number of his father’s generation. His uncle Roddie died at sixty-six, Donald at fifty-seven and Johnny himself at sixty-two, either taken through cancer or the heart, both of which my father has survived. His mother might have lived to seventy-nine, his Uncle Scott to eighty-one and Aunt Belle to eighty-three, but Donald’s widow, Jesse, still holds the record, managing a matter of weeks away from one hundred and six.My father has quietly lived here since he was roughly a year old, as he and my grandparents moved from where my sister now lives to the farm, a stretch of land originally granted to us back in 1845.

The day was grand. I couldn’t get any photos of Rose, given she spent the entire day running (with a myriad of cousins), and about a third of the people there took turns holding the baby. My eldest niece, Emma, unfortunately, was home sick, and couldn’t participate; neither could my eldest daughter, Kate, caught up at work (inventory was non-optional, she was told).

The day was grand. I couldn’t get any photos of Rose, given she spent the entire day running (with a myriad of cousins), and about a third of the people there took turns holding the baby. My eldest niece, Emma, unfortunately, was home sick, and couldn’t participate; neither could my eldest daughter, Kate, caught up at work (inventory was non-optional, she was told).There were even speeches. More than a couple of folk spoke, including Kris and Aunt Pam, and I inarticulately fumbled my way through something-or-other (bah). My sister, at least, managed a good little speech about how dad is apparently awesome (I had no idea!). What was interesting in some of the short speeches was in the number of friends and neighbours (including Kris, as well as some more recent neighbours) who spoke to my father’s generosity: how he was always the first to help when you needed, sometimes even before you knew you needed help. Kris spoke of how good Dad was to his own parents, after he’d moved off the farm next door. He was the first to welcome another couple, who’d only moved in a few years back, also. It is always good to see someone appreciated for so many years of humble kindness, generosity and simple, essential work. The best neighbour anyone could have, someone said.

And of course, he got up and said a few words as well; a bit awkward, and rather shell-shocked, I think, from the entire day.

All in all, a good day. We should do such again for 76.

Published on July 17, 2016 05:31

July 16, 2016

Ongoing notes: the ottawa small press book fair (part one,

[Stephen Brockwell, right, speaking to a seated Jim Johnstone] Okay: given our wee girls, it has taken more than a couple of weeks to start getting into the small mound of publications I ended up with, after our most recent small press fair in mid-June.

[Stephen Brockwell, right, speaking to a seated Jim Johnstone] Okay: given our wee girls, it has taken more than a couple of weeks to start getting into the small mound of publications I ended up with, after our most recent small press fair in mid-June. Ottawa ON: Only a few blocks away from where we live in Ottawa’s Alta Vista neighbourhood, poet and critic D.S. Stymeist (who has a first poetry collection forthcoming, by the by) runs Textualis Press, a small chapbook press only a couple of titles in. His newest title is by Ottawa poet Stephen Brockwell, the chapbook Where Did You See It Last? (June, 2016), a lovely title “Printed on Classic Laid (Avon Brilliant White),” with cover stock “Glama Natural (Pearl) and Royal Sundance Fiber (Ice Blue).” Even if you don’t know much about paper, you might just get a slight sense of how damned classy this small item looks. I’ve always been fascinated by the way, through some half-a-dozen trade poetry collections going back to the late 1980s, that Brockwell has composed poems as small ‘moments,’ composing small capsules utilizing voice and/or character studies. The poem “Biography of the Letterpress Father,” while I know I can’t automatically read as biographical, becomes curious knowing that his own father was actually the printer of Brockwell’s debut, The Wire in Fences (Toronto ON: Balmuir Press, 1988), a poetry collection that included a number of short, lyric ‘studies’ surrounding his mother’s home territory of Glengarry County, Ontario.

Biography of the Letterpress Father

The day after my father died, I swepta thousand pounds of scrap—plates, rods, wires,gears—with an industrial broom three feet wide.I hurled reams of 90lb cover stock, rolls

of blank newsprint, corrugated cardboard,pallets of die-cut printed boxboard packedbut never delivered to a customer who never paid.I dumped his confession from drawers of lead type

on the concrete floor of the loading dockand shoveled it into the bin below.I poured endless canisters of wasted ink,

blending indigo, emerald, pink, gold and blackinto this grey biography of his adulterous heart.

There is something about the production of this small item that really clicks with the meditative weight of Brockwell’s pieces in this short collection, eight poems moving through a variety of “biographies,” from “Biography of the Discovered Owl” to “Biography of the Barbed Wire Scar” and “Biography of the Praying Mantis,” as well as the enticingly-titled “Bacon Production on an Industrial Scale.” And for those who don’t already know, Brockwell also has a new poetry title out this fall—All of Us Reticent, Here, Together—with Mansfield Press.

There is something about the production of this small item that really clicks with the meditative weight of Brockwell’s pieces in this short collection, eight poems moving through a variety of “biographies,” from “Biography of the Discovered Owl” to “Biography of the Barbed Wire Scar” and “Biography of the Praying Mantis,” as well as the enticingly-titled “Bacon Production on an Industrial Scale.” And for those who don’t already know, Brockwell also has a new poetry title out this fall—All of Us Reticent, Here, Together—with Mansfield Press. [Mark Laliberte of Carousel beside Catriona Wright of Desert Pets Press]

[Mark Laliberte of Carousel beside Catriona Wright of Desert Pets Press] Toronto ON: From Toronto’s Desert Pets Press comes FOREIGN EXPERTS BUILDING (2016) by Michelle Brown, a poet who is, incidentally, also the author of a forthcoming debut poetry collection: in 2018, with Palimpsest Press. There are some intriguing moments in Brown’s short lyrics, such as the cadence of the poems “SUN RISES IN A CHINESE HOSPITAL” and “LEDGE.” There are moments in some of these pieces that require a bit more tightening, and other moments that do feel a bit too ‘clever’ for their own good, such as the opening to the poem “APARTMENT,” that reads: “The couple next door had a baby, and each night / we woke to his baby ennui.” As a whole unit, this small chapbook might not be perfect, but there is enough positive and intriguing in this debut that Michelle Brown now has my attention.

SOMETHING FUNNY

Here’s something funny. A clamshell that you couldn’topen. In a market, and it was definitely funny.The others thought so. They were all wiping their Eyes with dirty napkins as they watched you dig your nails in.In the market, as the night was closing up. The people were laughingand you were angry because you wanted it so bad, wanted it all, the hearts and brain of it all together, and I was laughingbecause it was funny, so funny, and that’s what humour is,it’s funny because you’re afraid it’s true, and here I was laughingat your stubby fingers, laughing at the woman scrubbing the shellsin a bucket of seawater, laughing at the sea, that impossibility,and knew that nothing would ever be funny againas we stood up from the table and returned to the rain,all of us laughing at you and the timing that deathseems to have, lapping at everything.

Published on July 16, 2016 05:31

July 15, 2016

U of Alberta writers-in-residence interviews: Karen Solie (2004-5)

For the sake of the fortieth anniversary of the writer-in-residence program (the longest lasting of its kind in Canada) at the University of Alberta, I have taken it upon myself to interview as many former University of Alberta writers-in-residence as possible [see the ongoing list of writers here]. See the link to the entire series of interviews (updating weekly) here.

Karen Solie’s most recent collection of poems,

The Road In Is Not the Same Road Out

, was published last year by House of Anansi in Canada, and in the U.S. by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. A volume of selected and new poems,

The Living Option

, was published in the U.K. in 2013.

Karen Solie’s most recent collection of poems,

The Road In Is Not the Same Road Out

, was published last year by House of Anansi in Canada, and in the U.S. by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. A volume of selected and new poems,

The Living Option

, was published in the U.K. in 2013. She was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 2004-5 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you were about to publish your second poetry collection. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: Because the publication of my first book came as a surprise, the experience of the second was different. I imagine it is for most writers. Modern and Normal was written with an element of nervousness – hope/doubt/curiosity/determination/fear – over whether I could write not just something else, but something better. Though I’m working on my 5th manuscript now, and the experience is the same. In terms of how it feels, where I am in my writing now is more or less where I was then. In some ways I’m more sure of myself; in others, less.

U of A gave me my first writer-in-residence job, in fact my first job as a writer, and I was in equal parts grateful, exhilarated, and intimidated. I learned a great deal about mentoring at a very important time to learn it, and a number of fascinating people came through my office. I know I learned more from the job, from the writers I worked with, than they did from me. It was a weird time, too. I lived in an apartment hotel on the edge of downtown that was its own strange planet. Modern and Normalwas edited there, and I also drafted work that ended up in Pigeon .

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Were you working on anything specific while there, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: I haven’t until my current manuscript-in-progress embarked on the writing of a book or series of poems guided by a particular theme or subject. The handful of found poems in Modern and Normal came about not from a desire to write a series of found poems, but from a realization at some point that I’d accumulated a fair number of them. The task then was to reduce that number by half – two-thirds, probably – which was part of the editing I undertook in Edmonton. I was interested while working on that book to think through scenarios, references, details not as derived from personal anecdote. To supplement my store of figurative language, but also to refine, complicate, and vary how metaphor might operate. This risk in these statements is always that people will read the work with them in mind and think, “hmm, really”? Anyway, I read more and researched more. Tonal and rhetorical registers became a concern – their use and overuse. But all this developed pretty naturally. None of it was outlined as a plan to pursue.

The U of A position was a new experience, and as such made its way into what I was writing the way any new experience does. But it also afforded reading time, note-taking and thinking time, which is invaluable in its generally rarity. As mentioned, I did some new writing toward Pigeon while in Edmonton. The long(ish) prose piece “Archive” was drafted there, for one, inspired by my terror at walking across the High Level Bridge. I drafted many other poems that went nowhere, too. Got a few of those out of the way, which is part of it.

Q: Given the fact that you aren’t an Alberta writer, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while in Edmonton? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: Though not from Alberta, I am from southwest Saskatchewan, so know the prairies. I very much liked that I could drive home to the farm every other week or so throughout my tenure. It’s a six-hour drive, depending on weather, so in Canadian terms not bad. I appreciated being in the north-central part of the province for its differences in climate, wildlife, landscape, and for the proximity to the North Saskatchewan River. I love rivers, their disparate characters, and spent a lot of time in the river valley. I also visited Elk Island Park and was intimidated by some bison. The High Level Bridge ended up influencing me a great deal, if being influenced can mean being terrified by. I lived on the downtown side of the river and walked the bridge a few times a week to get to the university, sometimes in pretty bad weather. My parents’ ‘92 Crown Victoria would be frozen solid in my apartment building’s parking lot, and by the time I’d stepped out onto the trestle I’d gone too far to hike back downtown to the subway. It would have seemed – not like defeat, I’m okay with defeat – kind of crazy. The bridge became a sort of icon for me during my time there.

I met wonderful writers, participated in and attended some great events, but don’t think I can really characterize the literary community then. Eight months isn’t enough time to get a good handle on anything. And it was 12 years ago. One thing I remember very clearly is reading C.D. Wright for the first time in Audrey’s Books on Jasper Avenue. You never know when or where you’ll encounter the work that will change you.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? Were there any encounters that stood out?

A: I remember I was chuffed to have an office with my name on the door, where people could come to see me. I probably met with more writers from the larger community than I did with students. A guy called from jail to talk about his poetry. And there was an older fellow, around 80, who wanted to write stories about his life to give to his children and grandchildren. Okay, I thought. But then his stories were fantastic, a blend of fact and fiction. He wrote about owning a racehorse, about learning to hunt. They were vivid and funny and frank, literary in the best way. I encouraged him to try publishing them, but I don’t think he was really interested in that. He was fun to talk to, too. It was a great lesson toward going into relationships with writers and their work with an open mind, and to respect what they want from the encounter. Which in no way means just patting them on the back. It was -- and still is; the lesson is ongoing -- about seeing beyond my own inclinations.

Q: Looking back on the experience now, how do you think it impacted upon your work?

A: My work, as I think of it, is teaching, mentoring, and editing as well as writing, and I learned a great deal about all of it during my tenure. I made mistakes in my interactions with writers then, and regret that they had to suffer my inexperience. Not that I don’t make mistakes still, I do all the time. But my first writer-in-residence position afforded me a practical knowledge of ways I needed to, and need to, improve. The job came at a crucial time financially, put the money panic on the back burner so I could attend to the writing panic of finishing edits on the second book, and it also afforded the luxury to start on the third. In that luxury, I felt a little more free to experiment, to take time to read. The curiosities I developed then persist to this day.

Published on July 15, 2016 05:31

July 14, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ingrid Ruthig

Ingrid Ruthig

[photo credit: Iwona Dufaj] earned a Bachelor of Architecture at the University of Toronto in the 1980s and practised the profession for more than a decade. Her work as a writer, editor, and artist has appeared widely, with poems published in The Best Canadian Poetry in English 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different? A first book offers a sense of legitimacy, marks you as a paid-up member of the tribe. Even though I’ve been part of the lit community for a long while – remember how we chewed the fat at Toronto’s Small Press Fair way back when? – I skirted around my ‘first’ book by producing so many others: 17 issues of the literary journal I co-edited & co-published from 2000–2007; anthologies; a chapbook; a poem-sequence-artist’s-book; a volume of critical essays I edited about another poet’s work; and a volume of poems I introduced and selected from the work of yet another poet. So, in a way, my first book doesn’t quite feel like a first. While I’m glad now that it didn’t leave home sooner, the pressure to get it out there has finally eased.

Ingrid Ruthig

[photo credit: Iwona Dufaj] earned a Bachelor of Architecture at the University of Toronto in the 1980s and practised the profession for more than a decade. Her work as a writer, editor, and artist has appeared widely, with poems published in The Best Canadian Poetry in English 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different? A first book offers a sense of legitimacy, marks you as a paid-up member of the tribe. Even though I’ve been part of the lit community for a long while – remember how we chewed the fat at Toronto’s Small Press Fair way back when? – I skirted around my ‘first’ book by producing so many others: 17 issues of the literary journal I co-edited & co-published from 2000–2007; anthologies; a chapbook; a poem-sequence-artist’s-book; a volume of critical essays I edited about another poet’s work; and a volume of poems I introduced and selected from the work of yet another poet. So, in a way, my first book doesn’t quite feel like a first. While I’m glad now that it didn’t leave home sooner, the pressure to get it out there has finally eased. Built on all that’s come before, my recent work has settled into its own skin, I think. No more toe-in-the-shallows, all fuck-this-I’m-swimming-for-open-ocean, I’m focused on my own direction, not someone else’s.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? Poetry clobbered me and dragged me off to its lair. Even if childhood exposure to hymns, psalms, choral music, and Shakespeare signal formative poetical beginnings, I was into fiction first. However, one career, two children, a few published short stories, one drawered ms, and one burned (yup, I set fire to it, partly so I could say I did) novel later, I’d realized I couldn’t commit to the marriage demanded by fiction. BUT I found I could dip in and out of poems with short, intense bursts of energy and, as I read more and more, gaining my poetic education, I understood how well it suits me, how much I like what it can do.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes? It varies. Sometimes I can’t write fast enough – those rare moments when a ‘gift poem’ seems to materialize fully formed out of thin air. Other days it’s worse than pulling teeth – like you’re yanking on the spleen too and getting nowhere. The stubborn poems piss me off, yet I’m oddly suspicious of the obliging ones. I’m far more trusting of the process of steady application and as many drafts as it bloody well takes.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning? It often begins with an observation, idea, line, or image that hooks into me, aggravates till I get it out and find temporary relief. I prefer not to write with a ‘book’ in mind – I figure the threads of my preoccupations will weave themselves together eventually, to produce something far more interesting than what I could’ve mapped out ahead of time. In other words, I’d rather make discoveries along the way, than work to a plan. All the same, I’m a big-picture person by nature and by training, so some days book ideas fall all over themselves.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings? In theory, much like the whole tree-falls-in-the-forest thing, you can write a solid poem, never read it aloud to anyone but yourself (which you must do when you’re working on it), and it would still be a solid poem. However, readings are a testing ground – a way for the poet to offer and for the listener to experience a poem differently. I enjoy them – it’s a buzz to be able to voice the words as you intended them to be heard, then listen for how the audience engages. It’s not exactly part of the creative process, but you do find out pretty quick whether or not the poem has done its job.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are? Poetry offers a chance for connection, so it should capture more than the obvious. I’m fine with someone writing the ‘duck-on-a-pond’ type of poem, but it seems like a missed opportunity to reach deeper. Beyond that personal objective, and trying to acknowledge our linguistic and literary inheritance, I leave off theory. I want to spend my time paying attention, absorbing and reacting, documenting the what, while accepting that the why will always exist and answers will always be elusive.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be? Is being a writer a uniform you don, OR, is it a way of being you’ve had no say in? If you write, you observe, question, connect dots, mark incongruities and synchronicities, then offer up the results – because you can’t do otherwise; it’s how you take in the world. Still, that’s only one part of the equation. Readers come to the work on their own terms, and if they’re willing to engage, maybe something more happens – a change of viewpoint, an understanding, a vested interest that nudges out discord. Yeah, sounds grandiose. Bottom line: the written work is the offer of a meeting place.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? No matter how capable an editor you might be with someone else’s work, you can’t always be that for yourself. Another set of eyes on the work is crucial, because when you’ve crept too close to the trees to see the forest, a respectful editor pulls you away from the bark and swings the axe first. In that, I’ve been very lucky – working with Evan Jones has been exhilarating. Hard work, mind. But exhilarating nonetheless.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)? Hmm, I can’t think of any. Guess it sucked, whatever it was. Or it’s gone because I don’t take kindly to unsolicited advice. Ha.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to visual art)? What do you see as the appeal? It feels natural, doesn’t even register as a ‘move’ or shift – it’s the way I think. As an architect, you explore and communicate through both language and image, so I’m also used to the process. Taking text into the visual, for example, offers a different experience of the words, a different perspective. Moving between mediums provides another way to play out an idea and find something new, and sometimes it’s simply the only way I can get to where I want to go.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin? I try to maintain a routine – news and administrative stuff in the morning, then creative work in the afternoon. That said, I go when the going’s good, which often includes evenings, nights, weekends. The muse doesn’t read the clock and vacation isn’t in my dictionary.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration? Books. Visual art. Music. Poetry that reboots the brain. Conversation with creative friends. A change of scenery. The lake on a foul-weather day. A challenge. A deadline. Silence.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home? Lilac, in glorious, heady May-June bloom. And not quite so delightful, though just as potent: fresh-spread manure that damned-near singes the hair inside your nose.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art? Living informs the work: travel, visual art, history, people-watching, the land (it’s ingrained – my great-great-greats settled in SW Ontario in the early 1800s), and the Great Lakes themselves (same reason).

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work? There are several, though the details fluctuate, depending on the day or year. The work of contemporary Irish and Scottish poets sits well with me right now – maybe it’s the inherent musicality, the manifest reverence for language and cultural inheritance.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done? Indulge my Scottish genes and return to the Highlands. And bide a wee. In a castle.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer? I’ve worn several hats. As a kid, the first thing I ever wanted to be was an archaeologist. My parents thought a pianist or artist. I worked in construction, retail, and banking. I became an architect and practised for over a decade. I think I’ll stick with the hats I’m wearing now – the work is much like archaeology, as it happens.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else? The other things I’ve done. And all the things I’ve no desire to do.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film? Tough questions. I’ve really been digging Scottish poet Kathleen Jamie’s collection Waterlight. Film? Jane Campion’s Bright Star – don’t know if it was ‘great’, but I liked it.

20 - What are you currently working on? More poems. Always the poems. Essays – one is for another volume I’m editing for Guernica’s Essential Writers series, this one about the work of David Helwig. And I’m building a body of visual works for a solo show that will go up in fall 2017.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on July 14, 2016 05:31