Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 344

May 24, 2016

Sarah Burgoyne, Saint Twin

(A PRECARIOUS LIFE) ON THE SEA

the ocean you grew up watching has decided, finally, to take you in. “where else was i going to go?” you ask, setting off. it spews squid and minnows into your little boat for you to eat if you are hungry. you throw them back because you know the ocean is hungrier. at night, the moon casts a sidelong glance into your boat. you are less round. the ocean is delighted with your company. it carries you from place to place, each day a little easier, imagining your bright bones, sideways moons, it’ll use them as walking sticks.

The author of chapbooks through Proper Tales Press, Baseline Press and above/ground press, Montreal writer and editor Sarah Burgoyne’s first trade collection is Saint Twin (Toronto ON: Mansfield Press, 2016), a collection of, as the back cover informs, “story poems, short lyrics, long walks, tiny chapters, and fake psalms.” A hefty poetry collection at nearly one hundred and seventy pages, Saint Twin is a curious mix of straighter lyric, prose poem and short fiction, blended together to create something far more capable than the simple sum of its parts. Part of the unexpected quality of Burgoyne’s surreal lyrics comes from the structures of her pieces, slipping prose beside more traditional line breaks beside dialogue/script. Whereas most poetry collections hold together through their structural connections (some of which are the result of editors and/or copy-editors), Saint Twin remains deliberately scattered, almost collaged, maintaining a strength far more evocative than whether the collection of poems maintain consistent capitalizations or punctuations, all of which speak to Burgoyne’s incredible capacity for putting a book together. Furthermore, while the book might be structured into eight sections, one has to seek out the connections through other means; poems from the second section, “Psalms,” for example, according to the contents page, exist on pages “10, 13, 18, 23, 27, 30, 36, 42, 48, 51, 57, 61, 63, 67, 72, 81, 99, 113, 116, 119, 124, 132, 137, 139, 142, 144, 147, 152 [.]”

NOT AS ASCENSION.

Torn up in the surgery of night. The buttering under of it. Seven halos away from becoming a sprig of something anointed. Never too few in the brooding door frames; the spoken-to lighting the walls. The corner-drawing minds buttoning silver horns of ancient wisdom. A voice: Dance with me, future loser, I love you. Hide under the table, I will call down the Lord without sulphur. To cast alms over our future mistakes.

I’ve been long intrigued at the options on how to construct a poetry manuscript out of scattered parts, aware that some who compose in chapbook-length units have set the units side-by-side for the sake of the book-length manuscript: Toronto writer Kevin Connolly’s first collection,

Asphalt Cigar

, is a good example of this, as are Kansas poet Megan Kaminski’s two collections,

Desiring Map

[see my review of such here] and

Deep City

[see my review of such here] (I’m less aware, with Kaminski, the chicken-or-egg of “which came first,” admittedly). Another poet, such as Ottawa poet Stephen Brockwell, might have composed the individual pieces of his 2007 poetry collection

The Real Made Up

[which I discussed here] into section-groupings, but resorted the manuscript into a single, book-length unit, allowing the final selection to blend together as a more cohesive single unit. What makes Burgoyne’s collection so unique is in how she somehow manages both sides of the structural divide, as one infers that the section were composed as single-units (at least two of her section titles correspond with chapbook titles), whether as short lyrics or prose poems, but were re-sorted for the sake of the full manuscript: the uniqueness lies in her adherence to that earlier, compositional structure, while allowing the book to live (or die) on its own single-unit coherence.

I’ve been long intrigued at the options on how to construct a poetry manuscript out of scattered parts, aware that some who compose in chapbook-length units have set the units side-by-side for the sake of the book-length manuscript: Toronto writer Kevin Connolly’s first collection,

Asphalt Cigar

, is a good example of this, as are Kansas poet Megan Kaminski’s two collections,

Desiring Map

[see my review of such here] and

Deep City

[see my review of such here] (I’m less aware, with Kaminski, the chicken-or-egg of “which came first,” admittedly). Another poet, such as Ottawa poet Stephen Brockwell, might have composed the individual pieces of his 2007 poetry collection

The Real Made Up

[which I discussed here] into section-groupings, but resorted the manuscript into a single, book-length unit, allowing the final selection to blend together as a more cohesive single unit. What makes Burgoyne’s collection so unique is in how she somehow manages both sides of the structural divide, as one infers that the section were composed as single-units (at least two of her section titles correspond with chapbook titles), whether as short lyrics or prose poems, but were re-sorted for the sake of the full manuscript: the uniqueness lies in her adherence to that earlier, compositional structure, while allowing the book to live (or die) on its own single-unit coherence.The poems in Saint Twin contain multitudes, from surreal wisdoms, biting self-awareness and hard-won observations to a wry humour, dark prophicies and proclimations, and an incredible optimism, such as in the poems “MY NEIGHBOUR’S MISFORTUNE PIERCES ME / AND I BEGIN TO COMPREHEND,” “IT WAS NOT IN PARKS THAT I LEARNED HUMLITITY” and “HAPPY BIRTHDAY, IN A NICE WAY.” As she write to open the poem “TO THE MASTERS OF OUR YOUTH, GREETINGS”: “the last days of a person’s life are the same / as the first [.]”

PERHAPS THE MUSEUM NEVER EXISTED

Maybe everything is good, after all.

The act of reading and the act of understanding

made it. The point is, relates to reality.

No wonder.

And what of this?

Precise laws. Behavior of individuals.

Unintentional walk. Map of maps.

Wheels on the table legs. The main activity

continuous drifting, these visions.

Dear professional juxtaposer,

maintain a division.

Cyberspace, I walked across it.

I’m a little disappointed.

Where the body is, at the corner.

Published on May 24, 2016 05:31

May 23, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Scherezade Siobhan

Scherezade Siobhan is a Jungian scarab moonlighting as a clinical psychologist. Her writing has been published worldwide, has been nominated for Pushchart Prize as well as Best of the Net anthology and translated into multiple languages. She has been featured in various digital and physical spaces and her work can be found in literary magazines, anthologies, international galleries, rehab centers and in the bios of okcupid users. Her digital collection of poems

Bone Tongue

was published by Thought Catalog Books in 2015 and her full length poetry book

Father, Husband

was recently released by Salopress UK. She can be found squeeing about militant bunnies and clinical psychology at www.viperslang.tumblr.com or @zaharaesque on twitter.

Scherezade Siobhan is a Jungian scarab moonlighting as a clinical psychologist. Her writing has been published worldwide, has been nominated for Pushchart Prize as well as Best of the Net anthology and translated into multiple languages. She has been featured in various digital and physical spaces and her work can be found in literary magazines, anthologies, international galleries, rehab centers and in the bios of okcupid users. Her digital collection of poems

Bone Tongue

was published by Thought Catalog Books in 2015 and her full length poetry book

Father, Husband

was recently released by Salopress UK. She can be found squeeing about militant bunnies and clinical psychology at www.viperslang.tumblr.com or @zaharaesque on twitter.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

In a way it feels more like my life changed first and the book was an outcome of that flux; something that a river deposits on its banks after a heavy monsoon. I wrote Bone Tongue for therapy with self through an intense and often debilitating period of MDD. In that sense, any writing I attempt is merely an extension of my compulsive diarying. My second book Father, Husband was actually a longer and more complex narrative because I was addressing multiple difficult subjects in it which I have usually chosen to be incredibly private about for most of my life. These books were like dizygotic twins - they shared a certain similarity of appearance without being the same, a common pool of genetic content but eventually each grew into its own individual behaviours, responses, narratives and personas.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

My grandfather had an envious library and I remember reading Eliot - “Do I dare disturb the universe?” I may not his writing as much today but at that point, it was such a critical shift in my ability to perceive my own reality as a young, introverted child on the threshold of complex psychological anomalies. I was stunned by the idea that you could indeed eat a peach AND disturb a universe in the same line. My grandfather also had a comprehensive collection of Tagore, Ghalib & Urdu poetry which he interpreted for us. Their melodic softness was a sharp contrast to my immediate world which was riddled with violence of childhood abuse. Through my grandparents I discovered Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Mahmoud Darwish, Shair Ludhianvi, Arun Kolatkar. It felt like those traveling carnivals that have a tent full of weird mirrors where every mirror showed you something new about yourself that was previously unexplored. Poetry, as opposed to fiction, told me that I could dream as wildly and as softly as I wanted to. Fiction expressed things. Poetry altered them.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I have never fully kept tabs on time mostly because I am always trying to steal snippets from frantic hours stuffed between traffic jams and client sessions. These tight, sardine can spaces are those in which I fit my writing. I think Ruth Stone had mentioned something about a poem coming to her with its tail first and then her chasing it there on. I sometimes experience the same thing. I distill from experience, cull from imagination. Lot of list making precedes my writing. In that sense I keep repeating to myself and my world - I am a diarist, first and always. Sometimes first drafts languish for months because I can't bear to look at them, let alone rework or edit. Note-taking is an occupational hazard since I am a clinical psychologist and it does percolate my overall cognition. On some days, the more agitated my mind is, the more intensely I enter the poem (sounds lacanian!). It is an act of chasing lightning. It is also the act of growing roses. A certain inevitable patience manifests itself and continues to straighten my spine on days I feel inexplicably weak.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Most poems begin as lists on google keep. This is another of my grandfather's legacy. He was an amateur entomologist and as a little girl I was fascinated by this ability to record the beauty of minutiae. I have notebooks filled with what I can lingual sigils. Verbs, adjectives, nouns snuggle with each other to define my day to day existence so I can return to the good parts on bad days. I don't write full sentences to begin with and this is simply coz when I started working on my own depression, I realised that as a habitual completionist the act of documenting my depression helped me but I often neglected it on account of not being able to write complete statements when I was clinically depressed. Twitter arrived in my field of vision exactly at this point and the staccato and minimalism of that medium was useful in setting up routines for me. This is something I personally find very satisfying because my depressive states are so compounded and extensive, I often feel I can't see beyond them or that there are no breaks in between. Writing helps me create silos out of this seemingly pervasive darkness - shines some light, cracks open some windows. Keeping this in mind, no I don't intentionally set out to write a book per se. It is usually an editor or a publisher who realises this while reading my body of work and makes me aware of it.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I did a lot of locally organized spoken word performances when I was a teenager. I was terribly shy as a child and being on a stage really helped me get more comfortable with my own voice. I have read at a variety of local and global venues and each experience is highly individualistic. As a student of psychology, I like observing how a poem is intercepted by a group of people, how it either challenges or acquiesces to their assumptions about poetry. As a community fest, a group of expat students from Russia came and held my hand after I read a poem called “Suvival Kit” which details my struggle with suicide attempts. They were 19-23 and each had the same thing to say – Thank you. I chronicle my own battles with mental health quite frequently in my poems and when I read it for other people, catharsis becomes a community. I come from Indian and Roma lineage and most of our ancestral storytelling happened in the tradition of oral poetry so I very strongly believe in the restorative powers of performance poetry.

Whether it arranges itself as a seance or an exorcism.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Initially I wanted to abstain from recondite proselytizing in poetry. It struck me as jejune and narcissistic. I love what Sina Queyras once wrote – “I don’t want a theory; I want the poem inside me. I want the poem to unfurl like a thousand monks chanting inside me. I want the poem to skewer me, to catapult me into the clouds.” In a way, as you get older you strive for a balance that may not entirely be achievable but nevertheless helps you ache and aim for something more infinite expanding within you. I do realise now that much of my love/hate relationship with psychoanalysis does inch its way into my own writing. I can't abstain from academia because I am constantly engaging with it. Even my occasional disdain for it has to be delved into. I am writing as a woman of colour and I am writing about agencies of psychological and material exiles. In the world I inhabit, a woman may achieve significant physical freedom but there remain vast bastions of her mind that are colonized by way of media, morality, body politics and a horde of other constructs. I recently started writing about PTSD and childhood abuse where a lot of my what I was processing was happening in the company of books and texts by Bessel van der Kolk, Peter Levine & Judith Lewis Herman as much as it was happening with my internalizing the work of Dawn Lundy Martin and Anna Kamienska. I can continue to answer this forever but in summary, poetry is the theory of everything. A poet is the serf of time - Canetti, I think.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

In the cultures I emerged from, a writer is always perceived to have the opposite of a dissociative personality wherein instead of one self fracturing into many, many independent selves combine into one while retaining their respective autonomy. In that sense we were raised with the idea of writing as an act of revolution - whether personal or universal was a think for the afterward. In most cases, a really good writer might bring about both. As half Roma Spanish, I look at the significance of Lorca or Generación del 98 or as half Indian, the significance of Ishmat & Manto in countering gender and sexual morality in pre/post-independence India even at the risk of imprisonment, those are foundational aspect so my self-building. In India Dalit poets eschewed conventional, “highbrow” languages to form their own slang and circle of acceptance. There is a singular measure for how well a democracy is functioning: How frequently is it willing to discuss & listen to the voices its bureaucratic & policing machinery are not entirely comfortable with. Whose voices are these? Where are they coming from? Us, of course! From DADA to Oulipo to alt lit, everything is an act of reaching out, turning things upside down, small or big subversions. A lot of times I hear criticism about how my generation often writes bland, flat-line poems about cats and I urge those people to inspect deeply as to what the conditions surrounding this generation are. When you are thrown into global wars you resent and oppose but have no say in stopping, when you are buried in debt, have to lead lives of hyperactivity you can neither avoid nor fully digest then maybe writing about a cat is the most amazing act of revolt, of flipping the bird at the collective poobahs of literary canons and saying - I am reclaiming my ordinary. I am not breaking at the jaws of your expectations.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

In my experience, it has been quite non-intrusive and dependable at the same time. I don't know if this will continue as I collaborate with newer and bigger publishing spaces but I do hope it stays the same!

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

My mother after reading something I wrote at 18 - It is good but why don't you let Borges be Borges and you try to write like yourself? It will take a lot of time to figure out who “yourself” is but try it anyway. I would love to see that.

(She is a Skinnerian behaviourist. That should explain a lot.)

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

A typical day begins with patients (clients)! (I record things into my phone through the day, I scribble notes next to clinical profiles. I tweet a lot of things circling my head through the day.)

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I am good at compartmentalizing things. This is not always a healthy habit but can be honed to help you organize how you write. When anything gets stalled (and you know this fairly well just in terms of how much time it has taken me to complete this interview!), I usually go 180 degrees from its origin. I will travel or watch movies or cook waiting for the proverbial tail of the lightning to swish my nose again!

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Roses, darjeeling tea & shami kebabs.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music, extensively. My day job involves listening to people but outside of it, I am always found with a pair of headphones enthroned on my nest of hair. Cooking or culinary arts is a new found area of interest which feeds (ugh, pun!) the writing a lot these days. Martial arts, astronomy, steganography, cartomancy, calligraphy - there is a whole group of activities that involve me and keep me nourished.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

So many! I write poems because Mina Loy once wrote poems. She is the first word in my vocabulary. Her work along with that of Djuna Barnes' stretched the boundaries of my imagination and I am thankful for that.

Currently, Dawn Lundy Martin's poems are incredibly potent and necessary for me. It's marvelous combination of defiance and empathy is nearly prophetic. I am thankful for every woman of colour who writes and occupies that space without apologizing for it or herself. Bhanu Kapil is another writer whose existence has changed the course of how I think about identity, language and the bridge between identity and language. Jennifer Moxley is my spiritmother even if she doesn't know it! Will Alexander’s collections comforted me into believing that you didn’t need to simplify your language in order to pander to a common greed for porridge poetry. Cathy Park Hong, Sandra Cisneros, Naomi Shihab Nye, Suheir Hammad, Helen Oyeyemi, Safia Elhillo, Kaveh Akbar, Kazim Ali, W.S. Di Piero, Aimé Césaire, Mike Young and my partner Greg Bem.

Historically, Alejandra Pizarnik, Paul Celan, Rene Char & Anna Kamienska were some of the writers who made it ok for me to write beyond categorization or expectations because they chose to be non-linear and made meandering acceptable as well as introspective.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Skydiving!

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I already do it – Shrinkology. I always wanted to study the human mind & now I do!

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It was the other way around; everything else I did always led me to writing.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

A manual for cleaning women (Lucia Berlin)

Nahid (Iran)

19 - What are you currently working on?

A red velvet cheesecake.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on May 23, 2016 05:31

May 22, 2016

Profile on Monty Reid, with a few questions, at Open Book: Ontario,

My profile of Ottawa poet Monty Reid, anticipating his

Meditatio Placentae

(Brick Books, 2016) [launching this week in Ottawa via The TREE Reading Series], is now online at Open Book: Ontario.

My profile of Ottawa poet Monty Reid, anticipating his

Meditatio Placentae

(Brick Books, 2016) [launching this week in Ottawa via The TREE Reading Series], is now online at Open Book: Ontario.

Published on May 22, 2016 05:31

May 21, 2016

Helen Hajnoczky, Magyarázni

Nem

No, Hungarian is not a gendered language,but no, you do not want to play Joseph in thegoddamned Christmas play again this year!

No, you’re not jealous that no on asks her whichbathroom key she wants, even thoughyou’ve been asked this while wearing a skirt.

No, no long hair, no stockings,no heels, no tailored shirts. No way to indicatethem, no not them, not her, not him, just them.

No, she always gets to play Mary, and no,you do not want to play a goddamnedshepherd either!

Just no.

In an interview posted over at Touch the Donkey [a further interview with her on the same project lives here], Calgary poet (recently returned to the city after an extended period schooling in Montreal) Helen Hajnoczky discusses her second trade poetry collection, Magyarázni (Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2016):

Q: I’m curious about the Magyarázni poems: you speak of a difficulty in part, that came from writing out your relationship with your cultural background and community. What prompted you to begin this project, and what were your models, if any? I think of Andrew Suknaski writing out his Ukrainian and Russian backgrounds, for example, of even Erín Moure exploring the language and culture of the Galicians. And might Bloom and Martyr have progresses so quickly, perhaps, due to it being a kind of palate cleanser?

A: Magyaraznigerminated for a long time. There’s a wood chest in my parent’s house that my dad carved, and the tulips in his design are what inspired my project originally, particularly the visual poetry in the book. I started doodling tulips in the margins of my school notes with letters at their centre, with the accents used as stamen, long before I had really been introduced to visual poetry. The moment that sparked the project, though, was one night when my dad and I were up late chatting about when he, his sisters, and his mother left Hungary after the ’56 revolution and I thought “I should really write this down.” So, I went and typed up everything he’d said and made a little chapbook of it for him. I wanted to do something more on the topic though, and was fortunate to get a grant for the visual and written poetry book and to travel around Western Canada interviewing people who’d come during or after ’56, or whose family had done so. Originally I’d thought of including the interviews and poems in one book, but the interviews are numerous, long, and detailed and really deserved to be their own thing (which I’m still slowly working on). Though I didn’t use anything from the interviews in this book the people who so generously told me their stories definitely influenced me and the writing of Magyarázni.

For more poetic influences though, Oana Avasilichioaei’s book Abandon, and the way she deals with cultural identity and nostalgia had a huge influence on me. The way Fred Wah’s writes about cultural identity, how that’s tied up with family, and the way he sets all this against the backdrop of the prairie all strongly informed the way I approached writing this book too—there’s a lot of Calgary in Magyarázni. Additionally, in 2007 Erín Moure and Oana Avasilichioaei spoke at the UofC for Translating Translating Montréal, and I have this fuzzy memory of them discussing translating words based on a feeling of the word or based on a word in a third language that the word in the source text reminds you of (I can’t remember precisely what they said and I don’t want to misquote them or misrepresent their ideas, but I believe the discussion was something along these lines), and this idea was key in the writing of Magyarázni. For example, the poem “Belváros”—the word translates into English as “inner city” (so, downtown), but I always hear it as ‘beautiful city,’ because in French ‘belle’ means beautiful. I went to a French immersion elementary school and I started hearing the word that way as a little kid, and I still hear it that way, not as inner city but as beautiful city. Because the project struggles to answer the question of how much one person’s experience of a language or culture can be representative of a community as a whole, I thought it was important to include these little hyper-personal feelings about words in the manuscript.

The author of numerous chapbooks, Hajnoczky’s first trade collection appeared as

Poets and Killers: A Life in Advertising

(Montreal QC: Snare/Invisible, 2010) and a portion of her manuscript “Bloom and Martyr” was selected for the 2015 John Lent Poetry-Prose Award, to be published as a chapbook by Kalamalka Press “in spring 2016.”

The author of numerous chapbooks, Hajnoczky’s first trade collection appeared as

Poets and Killers: A Life in Advertising

(Montreal QC: Snare/Invisible, 2010) and a portion of her manuscript “Bloom and Martyr” was selected for the 2015 John Lent Poetry-Prose Award, to be published as a chapbook by Kalamalka Press “in spring 2016.” As the press release for Magyarázniinforms: “The word ‘magyarázni’ (pronounced MAUDE-yar-az-knee) means ‘to explain’ in Hungarian, but translates literally as ‘make it Hungarian.’ This faux-Hungarian language primer, written in direct address, invites readers to experience what it’s like to be ‘made Hungarian’ by growing up with a parent who immigrated to North America as a refugee.” Bookended by the poems “Pronounciation Guide” and the prose poem “Learning Activities,” Magyarázni is composed as a stunning, lush and lively abecedarian, and each poem appears with a corresponding visual poem in resounding red and black. There is an element of “coming-of-age” to this collection, as the author/narrator works to reconcile the past with the present (and future), from a childhood built by Hungarian language and culture (from her parents’ own stories to her own engagements with cultural heritage), and how such foundations now require translation and explanation, even as she attempts to reclaim those same histories. Magyarázni writes her childhood home, her parent’s homeland and her time spent in Montreal (as in the poem “Zibbad,” as she writes: “You’ve been here longer now / than you were ever there and then some.”), writing embroidery, linen, memory and grief.

Cukorka

Your reflection splintered in foilthese solemn treats

this bitter historysugary sweet

unhooked from the tree you melt

a plastic angel dipped in flames, blurred and bubbling

you unwrapthe old world you chew and smile

you don’t swallowuntil they look away.

The poems are composed as someone caught between two poles, still navigating the blend of culture and cadence of language, family and belonging. The extended paragraph-poem “Learning Activities,” a poem that closes the collection, ends with: “Please note that W is not a true Hungarian letter. Please note that Xis not a true Hungarian letter. Please note that Y is not a true Hungarian letter. Cut the sickle and hammer out of a communist-era Hungarian flag. Tell me, do you miss speaking Hungarian? That is, do you miss your father?”

Published on May 21, 2016 05:31

May 20, 2016

U of Alberta writers-in-residence interviews: Shani Mootoo (2001-2)

For the sake of the fortieth anniversary of the writer-in-residence program (the longest lasting of its kind in Canada) at the University of Alberta, I have taken it upon myself to interview as many former University of Alberta writers-in-residence as possible [see the ongoing list of writers here]. See the link to the entire series of interviews (updating weekly) here.

Shani Mootoo

was born in Ireland, and grew up in Trinidad. She is a visual artist, video maker and fiction writer. Her paintings have been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions internationally, most notably at the Vancouver Art Gallery, The Queens Museum, NYC, and at the Venice Biennale. Her videos include English Lesson, Wild Woman in The Woods and Her Sweetness Lingers and have been screened internationally, including at the Museum of Modern Art, NYC.

Shani Mootoo

was born in Ireland, and grew up in Trinidad. She is a visual artist, video maker and fiction writer. Her paintings have been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions internationally, most notably at the Vancouver Art Gallery, The Queens Museum, NYC, and at the Venice Biennale. Her videos include English Lesson, Wild Woman in The Woods and Her Sweetness Lingers and have been screened internationally, including at the Museum of Modern Art, NYC. Mootoo’s novels include Moving Forward Sideways Like a Crab , longlisted for the Scotia Bank Giller Prize, shortlisted for the Lambda Award; Valmiki’s Daughter , longlisted for the Scotia Bank Giller Prize; He Drown She in the Sea , longlisted for the Dublin IMPAC Award, and Cereus Blooms at Night , shortlisted for the Giller Prize, The Chapters First Novel Award, The Ethel Wilson Book Prize, and longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. She is also the author of Out on Main Street , a collection of short stories, and a collection of poetry titled The Predicament of Or .

Mootoo divides her time between Grenada and Canada.

She was writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta during the 2001-2 academic year.

Q: When you began your residency, you’d published a couple of books over the previous decade, and been involved in a wide variety of art exhibitions and short films. Where did you feel you were in your writing? What did the opportunity mean to you?

A: When I began the residency, I had three books, Out on Main Street which is a small collection of short stories, a novel Cereus Blooms at Night, and The Predicament of Or, which is a book of poetry. So each one was in a different form of writing, but not a conscious effort to try out the different forms. At the time, writing in general was just another creative ‘outlet’, and supplemented the visual art and video-making I was doing. Writing allowed me another form of expression for the same kinds of issues I was taking on in the visual and video arts. The residency was a great opportunity- space, time and an honorarium- to see what would I might with the writing, again. What I worked on became He Drown She in the Sea, a novel. It really did something for me, as by the end of it I had two novels under my belt, so to speak. It gave me the sense that I was not simply dabbling in yet another art form, and I learned unequivocally that writing was going to be an important medium for me, quite different from the visual art and the video, very specific and necessary for my creative voice.

Q: What do you feel your time as writer-in-residence at University of Alberta allowed you to explore in your work? Were you working on anything specific while there, or was it more of an opportunity to expand your repertoire?

A: My first novel, Cereus, was a kind of experiment- based on practices I engaged in, in art making. It was fairly organic. I didn’t know the story when I began it, nor the characters, nor the beginning or the end. I began that book with a tiny picture in my mind, of an old woman, and wanted to try and figure out, through the writing, who she was. So, in some ways, my process was more of an art-making process. I wanted to use the opportunity of the residency to try and write in a more organized manner, with more of a plan, a more solid idea at the beginning. In other words I wanted to try and work like a writer, not like an experimental painter or video-maker.

It wasn’t entirely possible in the end, as I so very much enjoy discovery in creative processes. I found out many related things during that term- that I really do love writing as a discrete form, that having a plan at the top of the work makes life much easier (a novel is long and can get unwieldy fast), and that once I had a plan of sorts it made veering this way or that way much easier, much more enjoyable. There was a map with main roads, yet room for leaving the road for a little adventure, and then coming back. I found out that I really love the long form, the time it takes, the time one can go away far into one’s mind, one’s imagination, and think and analyze and flesh out. It’s not too strong to say that it was through that residency that I saw that I could indeed be a writer one day.

Q: How did you engage with students and the community during your residency? Were there any encounters that stood out?

A: There were readings at the University at which I met students, readings in the Edmonton area where I met residents, and talks in classes where I really got to engage with students. In the office, I saw a few very interesting writing projects from students at the University, from faculty members who were trying their hand at creative writing, and from residents of the area who had manuscripts they wanted a comment on. In general the community was incredibly generous and hospitable, inviting me here and there, but I came in time to understand that this is just the way Edmontonians are. I really enjoyed it.

Q: What do you see as your biggest accomplishment while there? What had you been hoping to achieve?

A: I wanted to see if I could do it again. If I could write again. Another novel. Anything. Something. I began and worked well into He Drown She and it was finished about two years later. The start of a book, a novel, was an achievement, then, but more than that, I think it was finding out that writing was not just another opportunity to express myself in another medium, but that it was a discrete form that I was not going to let drop.

And the book was longlisted for an IMPAC award, a not too small thing.

Q: Given the fact that you aren’t an Alberta writer, were you influenced at all by the landscape, or the writing or writers you interacted with while in Edmonton? What was your sense of the literary community?

A: Landscape is landscape. The first landscape I ever knew was the Trinidad landscape. Then it was Vancouver and B.C. I wrote my first three books in B.C. The short stories and novel were very much centered in Vancouver, but the landscape of the poetry was B.C. Trinidad, Australia, Belgium, Nepal. Whenever I wrote in B.C. or in Alberta, an important part of writing was bicycling. Not commuting, but riding in nature. That was when I did my best ‘writing’ – on the bicycle. I would go into the River Valley, or to Jasper or Banff, just to walk or ride, or breathe, and return with the so much inspiration- not to write or paint that landscape, because of the mental clarity was I able to find there, to tackle issues in my novel that were about, say, love, race, immigration, sexuality, friendship.

I met many people who were writing, but it wasn’t their actual writing that influenced me. We didn’t share our writing. But we shared something as valuable- the drive, the passion, ideas, food- the sense of being a band of a certain type of person, and I found validation- and I hope I gave that to others. There’s one person I did share with, actually, and that was Ted Bishop, a Professor of English there – he gave so much of himself – his friendship, his work, he took mine, there was food and coffee with him, and he, I would say, was one of those people who made me feel like I was a writer. I made some very good writing friends, inside and outside of the University. It was a really terrific opportunity. Very-very grateful for it.

Published on May 20, 2016 05:31

May 19, 2016

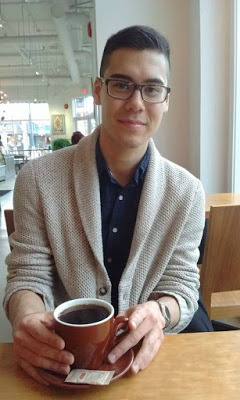

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Michael Prior

Michael Prior’s

poems have appeared in numerous journals across North America and the UK. A past winner of The Walrus’s Poetry Prize (2014), Grain’s Short Grain Contest (2014), and Matrix’s Lit Pop Award (2015), Michael’s first book of poems,

Model Disciple

, appeared from Véhicule Press in spring 2016. He is currently an MFA candidate in poetry at Cornell University. [note: this interview was conducted in March; Model Disciple is now very much available]

Michael Prior’s

poems have appeared in numerous journals across North America and the UK. A past winner of The Walrus’s Poetry Prize (2014), Grain’s Short Grain Contest (2014), and Matrix’s Lit Pop Award (2015), Michael’s first book of poems,

Model Disciple

, appeared from Véhicule Press in spring 2016. He is currently an MFA candidate in poetry at Cornell University. [note: this interview was conducted in March; Model Disciple is now very much available]1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I’m not sure. I keep writing and reading. Model Disciple is a month away from becoming something tangible in the sense that I could slip it onto a shelf or hurl it at the squirrels who argue outside my window at three in the morning. I’m at work on the next thing, and the next thing is always the next poem.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I had always liked poetry, but I managed to avoid reading it seriously, deeply, until the last couple years of my undergrad—however, when I did, certain poems and poets made sense (or poignant nonsense) in a visceral, intuitive way. I remember reading Dickinson’s “Adventure most unto itself” and then feeling as if the experience had taken the top of my head off.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It takes a while: Nowadays, I write much more slowly than I used to. Sometimes it’s a gradual accumulation of notes, or sometimes a poem just speaks, and if I listen closely enough, I can catch it, almost whole. Regardless of how the first draft comes into being, I spend a substantial amount of time editing. I’ve (thankfully) learned to be more patient with the process over the last couple years.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I like compelling, focused book-length projects, but I’ve always found my attention drawn more toward individual poems, rather than a book’s conceptual frameworks—though, I’ll admit it’s specious to pretend such distinctions always hold. Model Disciple arose around a set of inheritances (familial, cultural, and literary), but it was never meant to be a “project” per se, merely a collection of what my editor and I thought were my best poems—poems which, when placed into conversation, cohere into something larger.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don’t think readings play much of a role in my creative process, and I can’t say I like hearing my own voice (my voice, as I hear it in my head, is much better and sexier than my actual speaking voice—it sounds a little like George Takei), but I do appreciate the community-building and sense of inclusivity that can occur at a thoughtfully curated reading series.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

In this particular book, I try to be attentive to my Japanese Canadian-ness, my half-ness, and what I feel are my various literary affinities, and cultural identities—inextricably personal and public at once. In my mind, right now, the most constant question is how does a poet write a moving, memorable poem, and then do it again and again differently, spectacularly, quietly, beautifully, painfully, funnily? There are so many writers whose work I deeply admire and love asking this in insightful ways.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I believe I have an obligation to be as truthful as I can about aspects of my own experience, but at the same time, I often feel like the only debt a writer owes any larger culture is merely that they continue to work, and, as James Merrill once said, continue to seek “English in its billiard-table sense—words that have been set spinning against their own gravity.”

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential: I recently finished Joan Didion’s After Henry, a collection of essays dedicated to her long-time editor, Henry Robbins, who passed away before its publication. In the introduction, Didion writes, that a good editor’s role is vast and varied but that its greatest importance might have something to do with “maintain[ing] a faith the writer shares only in intermittent flashes.” In my experience, this rings true. I feel very fortunate to have learned so much from several great editors, and Carmine Starnino, who edited this book, has taught me a lot about what it means to see a project through with generosity and humour.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Eduardo C. Corral (Eduardo, I’m sorry if I misremember this): “Read widely of your contemporaries, but attend most closely to the dead.”

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I wish I had a routine!

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

At this moment: Roger Reeves’ “In the Lone Horse and Plum, Wu-Tang;” Mary Ruefle’s “Short Lecture on The Nature of Things;” Eszter Balint’s “Airless Midnight;” Hopkins’s “Spring and Fall;” Laura Clarke’s “Urkingdom;” Haruki Murakami’s “Super Frog Saves Tokyo;” Ben Ladouceur’s “Armadillo;” “Ian Duhig’s “Clare’s Jig;” Sheryda Warrener’s “Long Distance;” everything Alabama Shakes; and This music video from Flight Facilities.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I grew up near Vancouver. So, the smell of the Pacific.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Some of my best memories from my childhood involve watching TV with my dad, who would patiently answer my incessant questions. So, I would have to say films and TV probably inform my writing in unintended ways. I remember a lot of Westerns from Sergio Leone to John Ford, and then, later, episodes of Star Trek: Next Generation and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Imagine trying to explain the ethical mandate of the United Federation of Planets to a five year old (I love you, Dad).

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

A dozen off the top of my head: Thom Gunn, James Merrill, Eduardo. C. Corral, Alice Fulton, Ishion Hutchinson, Hannah Sanghee Park, Jim Johnstone, Michael Donaghy, Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, Thomas Hardy, Emily Dickinson.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Go to Scotland! There are, in my opinion, so many fantastic poets working there right now.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I doubt I have the skillset for much else, but I would have loved to have been a cinematographer. Or how about a professional dog walker? It’s always seemed to me like a pretty great gig: my friend, the poet Richard Kemick (owner of Maisy the Wonder Dog), worked as a dog walker for one summer and really enjoyed it.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

There were detours into photography and music, but I think, as is often the case, a series of great teachers and professors nudged me towards writing.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Too many books! Too many films! I think my responses to questions eleven and fourteen might contain an answer.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’m still recovering from Model Disciple, but there are poems.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on May 19, 2016 05:31

May 18, 2016

the ottawa small press fair, spring 2016 edition: June 18

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:the ottawa small press book fair

spring 2016 edition will be held on Saturday, June 18, 2016 in room 203 of the Jack Purcell Community Centre (on Elgin, at 320 Jack Purcell Lane).

“once upon a time, way way back in October 1994, rob mclennan and James Spyker invented a two-day event called the ottawa small press book fair, and held the first one at the National Archives of Canada...” Spyker moved to Toronto soon after our original event, but the fair continues, thanks in part to the help of generous volunteers, various writers and publishers, and the public for coming out to participate with alla their love and their dollars.

General info:the ottawa small press book fairnoon to 5pm (opens at 11:00 for exhibitors)

admission free to the public.

$20 for exhibitors, full tables$10 for half-tables(payable to rob mclennan, c/o 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9; paypal options also available

Note: for the sake of increased demand, we are now offering half tables.To be included in the exhibitor catalog: please include name of press, address, email, web address, contact person, type of publications, list of publications (with price), if submissions are being considered and any other pertinent info, including upcoming ottawa-area events (if any). Be sure to send by June 10th if you would like to appear in the exhibitor catalogue.

And don’t forget the pre-fair reading usually held the night before, at The Carleton Tavern! (readers tba)

BE AWARE: given that the spring 2013 was the first to reach capacity (forcing me to say no to at least half a dozen exhibitors), the fair can’t (unfortunately) fit everyone who wishes to participate. The fair is roughly first-come, first-served, altough preference will be given to small publishers over self-published authors (being a “small press fair,” after all).

The fair usually contains exhibitors with poetry books, novels, cookbooks, posters, t-shirts, graphic novels, comic books, magazines, scraps of paper, gum-ball machines with poems, 2x4s with text, etc, including regular appearances by publishers including above/ground press, AngelHousePress, Bywords.ca, Chaudiere Books, Room 302 Books, Arc Poetry Magazine, The Ottawa Arts Review, Buschek Books, The Grunge Papers, Apt. 9, In/Words magazine & press, Ottawa Press Gang, 40-Watt Spotlight, Puddles of Sky Press, room 302 books, Touch the Donkey, Phafours Press and others.

The ottawa small press fair is held twice a year, and was founded in 1994 by rob mclennan and James Spyker. Organized/hosted since by rob mclennan thru span-o.

Come on by and see some of the best of the small press from Ottawa and beyond!

Free things can be mailed for fair distribution to the same address. We are unable to sell things for publishers who aren’t able to make the event.

Also: please let me know if you are able/willing to poster, move tables or distribute fliers for the event. The more people we all tell, the better the fair!

Contact: rob mclennan at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com for questions, or to sign up for a table

Published on May 18, 2016 05:31

May 17, 2016

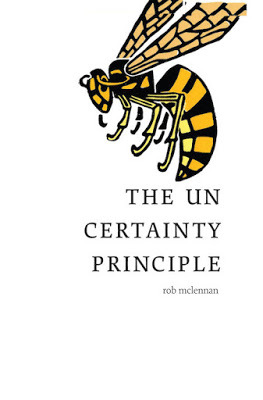

Author questions for rob mclennan : Vanessa Cimon-Lambert

On March 8, 2016, I answered some interview questions posed to me by one of Natalee Caple’s students over there at Brock University. This is actually the second interview posed by one of her students [see the link to the previous interview here; see the link to an ongoing list of all my interviews online here], with both interviews centred around my collection of short stories,

The Uncertainty Principle

(Chaudiere Books, 2014), as part of an ongoing series of interviews focusing on short fiction. I was extremely impressed with the questions posed by this student, far sharper than questions sent by those who supposedly consider themselves critics and/or interviewers, so I’m eager to see where she might end up...

On March 8, 2016, I answered some interview questions posed to me by one of Natalee Caple’s students over there at Brock University. This is actually the second interview posed by one of her students [see the link to the previous interview here; see the link to an ongoing list of all my interviews online here], with both interviews centred around my collection of short stories,

The Uncertainty Principle

(Chaudiere Books, 2014), as part of an ongoing series of interviews focusing on short fiction. I was extremely impressed with the questions posed by this student, far sharper than questions sent by those who supposedly consider themselves critics and/or interviewers, so I’m eager to see where she might end up...Vanessa Cimon-LambertProfessor Natalee Caple – ENCW 3P06

An Interview with rob mclennan on The Uncertainty Principle rob mclennan is a prolific writer of prose, poetry, and non-fiction as well as critical works including interviews, reviews, and essays. Living in the vibrant city of Ottawa, he is the author of over thirty trade books and is the editor and founder of the above/ground press, Chaudiere Books, and the poetry journal Touch the Donkey (mclennan’s blog). He won the John Newlove Poetry award in 2010, the Council for the Arts in Ottawa Mid-Career Award in 2014, and was longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize in 2012 (Canadian Literature 1). Recently, in 2014, rob mclennan had his collection of short, short stories The Uncertainty Principle published by Chaudiere Books. He lives in Ottawa and continues to promote the craft of writing and publishing.

Q&A :Q: The cover art is intriguing, mostly I think because of the whiteness and space on the cover allows the image of the wasp to appear more striking. Did you take part in the cover art design and what are your thoughts on the connection between the image and the content within the book?A: I’ve known Ottawa artist Danny Hussey for nearly twenty years, and have long admired the dense minimalism of his work, which I think fits completely with the pieces in the collection. He loaned me a small mound of prints in the late 1990s for the sake of a collaboration that never really saw fruition. Our move in September, 2013 provided the opportunity to dig out the pieces, and even remind myself that they were still sitting somewhere in my vast array of papers. The image comes from that small mound of prints.Given my wife and co-publisher Christine McNair designed the book, I’d say I had a good amount of input into the design of the cover. It was she who initially suggested the size and the use of white space on the cover, which is absolutely superb, and fits entirely, I’d think, with the book as a whole.

Q: The Small Press Book Review gave this collection its first review and that review examines the connection between the title of your work, The Uncertainty Principle, and the quantum mechanics concept of that principle. The review suggests that your “tiny prose” is comparable to the position of a particle, wherein both cannot be precisely determined. Can you elaborate on this connection and perhaps tell me what your own understanding and purpose was with this title, and how it has altered since its publication and reviews? What was your process in coming up with a title for this collection of short stories?A: Part of the challenge of these pieces was in their density, and their precision. There isn’t a wasted word, and yet, not everything is explained. I like leaving a certain amount of space for the reader to take the story slightly beyond the borders of what I have decided to include (and, thusly, not include). If I give everything away, there remains little or nothing for an attentive reader to do.

Q: Did these short shorts from The Uncertainty Principle, which are all individual accounts that seem to intertwine, come from other unfinished works or did some of these stories begin and remain short and self-contained. Moreover, what was the process you went through to compile these stories in this particular order?A: All but one of these pieces were composed entirely for this collection. Really, the first piece was the one referencing The Lost Boys (1987). I liked the piece very much for the fact that it was an odd blend of fiction and short essay. The piece confused me at first, as I asked myself “what the hell do I do with this?” given the fact that it certainly didn’t fit with anything I’d done before. It took a bit of time to consider that perhaps I needed to compose a mound of such odd, short, untitled pieces for the sake of something book-length. It was quite a challenge, and the process of beginning to end took roughly five years.The singular story that fell into the collection from a further work-in-progress was the story referencing cities requiring a memory (“Every city is constructed out of a series of markers,”): I often work on multiple projects simultaneously, and this fragment was originally composed for my as-yet-unfinished novel, “Don Quixote.” I liked the self-contained aspect of the short paragraph, and decided that it could be included in both manuscripts. Given that it lives in a different context, depending upon which book you might encounter it in, I like the way it shifts a bit. It might be the same paragraph with the same words in the same order, but, living in two entirely different projects, it can’t remain the same at all.The collage-accumulation of the collection required a very precise and particular order. For about four years, I simply wrote and wrote and wrote without any sense of order at all, attempting to simply compose short pieces that worked both as self-contained units and pieces that connected through the accumulated whole. I carved, carved, carved and carved. At one point, I’d one hundred and forty pieces, boiling down to about seventy or so. Through her own edits, Christine helped me salvage three or four of the pieces just before the book went to press.The final six months of putting the manuscript together was when I started thinking seriously about the order. Up to that point, I was focusing on the stories individual, deliberately without any thought to order, attempting to carve lines so tight one could bounce a quarter off any of them (so to speak). I wanted the various threads through the collection to intertwine the length and breadth of the collection, without putting stories that sounded too similar in tone or subject side-by-side. Part of that process also included seeing the work as a whole unit, which also allowed for the realization of whatever gaps there might have been, and attempting to fill them.

Q: I enjoyed The Uncertainty Principle because the writing style engaged with humour and relatable momentary experiences, where writing is able to dust off trite instances and make them new again. What kind of questions did you ask yourself while writing some of the more poignant passages, for example when the father and the daughter look at shooting stars (32), and the passage on childhood and the mother (40)?A: I don’t think the questions I asked myself were entirely overt. I wrote. Part of the appeal of composition included the realization that I could include wee stories around odd jokes or strange thoughts I’d had over the years, little fragments of thinking that had never really entered my writing before. I had that initial consideration about The Lost Boys that I’d been told hadn’t come up before even by vampire literature scholars, so I wondered, how do I get to keep this? How can I use this? And of course, one thought leads directly and immediately to another, such as my thoughts upon SpongeBob SquarePants, or seeing a plush rocket with an animal inside, meant somehow for newborns. Sometimes it was as simple as a stray line or a thought I caught from another source that I wanted to explore, or play with. I like discovering those ideas or thoughts that might entirely change the way we think about something that otherwise might seem entirely familiar, and thus, render it entirely new and unknown. I am attempting to question, I suppose.I wanted to take a series of very small moments and simply hold on to them, over the space of a couple of sentences. A few years ago, I discovered that Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk’s writing studio, for the longest time, sat on a street that translated into English as “Sesame Street.” I mean, how could one not want to use that? I’ve been three years carving and carving a story barely four lines long that I haven’t quite managed to get exactly right. At least, not yet.

Q: It seems a lot of the projects you’ve initiated such as literary journals and press revolve around the city of Ottawa. How has living in Ottawa shaped your writing, as well as your dedication to the craft? And what are ways you represent this identity in your work as a writer, reviewer and editor? A: A good question. By the mid-1990s, I’d been here for a bit more than half a decade, and had been active for nearly that long as a writer, editor and organizer. Given my ex-partner and I shared a preschooler, I was very aware that none of us, by choice, were going anywhere, so I deliberately worked to make the city liveable for myself as a working writer. Around the same period, I was seeing a number of poets leave town – Rob Manery, Louis Cabri, Warren Dean Fulton, Tamara Fairchild – something that occurred again by the end of the 1990s, as Stephanie Bolster left town for Montreal. It was extremely difficult to be a working writer in Ottawa, given our repeated lacks: proper arts funding (the worst per capita arts funding in Canada), media, publishing and employment (we haven’t any creative writing program at either university, for example, which often helps writers remain employed). It meant that writers were either swallowed up by government work, or left town for new opportunities. It really meant that, by the mid-1990s, despite already having founded above/ground press, The Factory Reading Series (at that point, as-yet-unnamed) and the semi-annual ottawa small press book fair (all of which I still run), I was becoming very aware of the lack of infrastructure required to support and encourage a larger literary culture. Predominantly, Ottawa books weren’t being discussed in the media in favour of works by out-of-towners, as though somehow remaining in the city meant we could only be “farm-team” for larger centres such as Montreal, Toronto or Vancouver. To remain here meant that your work became suspect, which was absolutely ridiculous. It helped enormously when Sean and Neil Wilson founded the Ottawa International Writers Festival in 1997, showcasing local writers on the same footing as nationally or internationally-renowned writers. Somehow, we needed to remind ourselves that we were capable of supporting and producing writers such as John Newlove, Elizabeth Hay, John Metcalf, Diana Brebner, Mark Frutkin, William Hawkins and dozens upon dozens of others. All that being said: I live here. Where else am I to revolve and involve my projects? It is my job – as editor, reviewer, publisher, reading series curator, etcetera – to be attentive to the writing and writers in my immediate geographies.I think the initial lack, in many ways, forced me very early to seek out what else existed beyond my immediate community, which, in the long term, has given me quite a broad knowledge of writing, writers and publishing far beyond the City of Ottawa. All of this, obviously, has fed into my editing, publishing and writing. I don’t feel limited in any way by where I am.But not all of my projects are Ottawa-based. I curate the weekly “Tuesday poem” over at the Dusie blog, a press and site originally based out of Switzerland. With more than one hundred and fifty poems posted so far, I curate via a number of threads, including submissions from Canadian poets, international poets and poets in the loosely-affiliated “dusie kollecktiv.” Projects such as above/ground press or seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics or Touch the Donkey or my “12 or 20 questions” series have neverbeen Ottawa-focused, although numerous Ottawa writers have been represented throughout. Chaudiere Books might be Ottawa-focused, but has never wished to be Ottawa-exclusive; my goals have been wanting to connect Ottawa writers and writing to the larger, broader world; we are no island, after all.

Q: Your engagement in a variety of writing platforms perhaps allows you to avoid “writer’s block” but are there other sources of inspiration you turn to in order to progress in a moment of creative writing? For example do you use music, memories, visiting a museum, or certain writing techniques to produce work? A: All of the above. Also, really well-written film or television has often sparked my fiction. I remember being sparked by the movie Smoke (1995), as well as certain episodes of Mad Men. I have also been mighty impressed by Brian Michael Bendis’ run on The Avengers; I loved the way he wrote a lengthy, ongoing story, often writing up to a particular action or dénouement, and instead taking the story entirely sideways before presenting the reader with that expected next step: providing further background or sideways action that expanded the breadth of what he’d accomplished so far. Amazing.And of course, Neil Gaiman, specifically via The Sandman, is easily the best storyteller I’ve read so far.I’d think that if there is a story or poem or whatnot one is attempting to complete (we create our own problems we then have to troubleshoot, don’t we?), the problem is most likely working in the background of our thoughts at any given time (as we head to the grocery store or shower or whatever). Solutions can arise just about anywhere; the trick is in knowing how to listen to what we are attempting to tell ourselves.And: my steady stream of reviewing can often trigger new writing. I’ve been an active reviewer for more than two decades, which means I receive new books and chapbooks in the mail every single day.

Q: I read in a few articles that you now have children and so do you notice changes in your source of inspiration when writing?A: Well, I now have smaller children: my daughter Kate was born in January 1991, and Rose was born in November 2013. My third (and Christine’s second) is due the third week of April 2016 (we have a shortlist of names, but we’re keeping names and gender a secret for now). I might be home full-time with Rose now, since Christine returned to work after her year-long maternity leave, but I actually ran a home-daycare until Kate was about four years old. Fatherhood and childcare, for me, at least, isn’t new; renewed, I suppose.With the emergence of our Rose, my writing has become far more focused: I now get two mornings a week when she’s at ‘school,’ and an hour or two in the afternoons when she naps. My projects are far fewer than they might have once been.I would think my ‘inspirations’ are much the same as they ever were: the world, as I encounter it (and/or it me), from reading to living to anything else. Kate has fallen into my writing multiple times over the years, and I spent three years on the first draft of a creative non-fiction manuscript after the death of my mother. When Christine and I began, she entered the writing; when we began to cohabitate, I wrote around that. So of course, her pregnancy and the then-newborn entered into the writing as well.

Q: Your blog is updated daily and you work on multiple projects at once but do you also work on different creative projects at a time? Or do you tend to focus on a particular work that is in progress?A: I’m able to work on multiple projects simultaneously, certainly. Since I’ve been full-time with toddler, my attention for writing has been shorter, so I’ve been deliberately working to keep to a shorter list of creative projects (everything takes so damned long).I’ve been attempting to complete a manuscript of short stories, for example, “this year” now for at least three years. I really want to get back into a novel I’d set aside a few years ago, for the sake of my post-mother creative non-fiction project.I can only work on one or two large prose projects at any given time, so really require to complete the stories before I can put any kind of attention into the novel, otherwise I’ve simply not got the attention span required for either (which was equally the case well before Rose was invented).I’m also about seventy pages into a poetry manuscript that began on March 1, 2015. I poke at the poems occasionally, but am deliberately not in any hurry to complete such (it would just mean I’d start something else). Every time I’ve attempted to work solely on a single thing, I’ve ended up starting a new project instead.

Q: On your blog you express your decision to remain solely a writer (and critic) rather than becoming a teacher as well. You were a writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta from 2007-2008, would you suggest an academic background for aspiring writers these days, or a creative writing degree?A: I would recommend whatever works for the individual. I’ve never felt the need to do anything but write, so never saw the point in a degree or two that would be leading me toward teaching. I wanted to write, so I wrote. For some, degrees and teaching is the best way; for others, the best way might be a writing degree. Some prefer the non-teaching/literary employment. I, myself, never saw the point in giving my best energy to something I cared about secondary to my writing. Somewhere in my mid-20s I saw a quote by Margaret Atwood: If you want full-time out of it, you have to put full-time into it.I would recommend anyone be honest and realistic about what it is they think they want to accomplish. Not everyone even wants to write full-time (and the financial compensations for such can be hardscrabble and, often, demoralizing).There’s a story about Willie Nelson, two years into a degree to be a lawyer as his “back-up plan,” before realizing it had quickly become his primary plan; he immediately dropped out to focus on his music.And: given I haven’t any post-secondary experience at all (which means I really haven’t any direct knowledge or experience with any kind of degree, whether literary or otherwise), I found the University of Alberta job very exciting, and even a bit confusing. The experience was glorious in part for the fact that I wasn’t required in any way to engage with the academic setting, i.e. some of the horror stories I’ve heard about office politics or the drudgery of marking. I could simply hang about and collect all of the benefits of academic life without any of the trappings.I also loved having an office, which I used as my work-space. I sat seven days a week in there, furiously working, from 9:30am to 6pm. My office door was never closed.

Q: In The Uncertainty Principle you write: “You might have no choice but to be new, again” (36). Individuals are constantly striving to constitute themselves as subjects in the world, and so what are your thoughts on the cultural and ethical purpose of the craft of writing for the self and for society at large?A: I’ve noticed that the bulk of my fiction focuses on individuals struggling to navigate themselves through the world, as I attempt to articulate the ways in which they might move from point A to point B. The craft of writing allows one to spotlight, to open up attention into the minutiae of being and interacting.Writing can be utilized as a critical/thinking, and even meditative form, one that can help illustrate, illuminate and even educate. If one is attempting to listen and be properly aware, it can be used in multiple ways, for multiple purposes. I’ve been very interested how poets such as Fred Wah, Christine Leclerc, Marie AnnHarte Baker and Stephen Collis, for example, use literary forms for social engagement. I’ve entertained such, but haven’t yet figured out the proper form(s) in which to engage; so far, my fiction (at least) explores a far more subtle engagement with being and living.

Q: When do you know a creative work of yours is finished and ready for publication (or even to be read by someone else)?A: Experience.

Q: You reference pop culture (tweets and famous musicians), politics (Harper and Reagan), and literature (James Joyce) in your stories. Do you find yourself feeling any tension between external influences on your work and your own intentions and, if so, how is it that you navigate this?A: I don’t feel any tension. I live in the world, therefore I attempt to engage with that same world, which includes art galleries, twitter, history, television, politics, pop culture, facebook, late night talk shows and comic books as well as a broad range of literary touchstones. I’ve long envied Milan Kundera’s ability to engage with the personal and the political equally throughout his fiction, and would love to be able to accomplish the same.I would suspect that all influences on a writer’s work would be external, even if writing about the self (without distance, there can be no clarity). It is important not to live (or write) in a bubble.

Works cited“rob mclennan” Canadian Literature: A Quarterly of Criticism and Review.https://canlit.ca/canlit_authors/rob-mclennan-2/. Accessed Feb. 16 2016. Web.LaRue, C.A. “Review of rob mclennan’s THE UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE: STORIES” TheSmall Press Book Review. March 2014.http://thesmallpressbookreview.blogspot.ca/2014/03/review-of-rob-mclennans-uncertainty.html. Accessed Feb. 16th 2016. Web.mclennan, rob. rob mclennan’s blog. https://www.patreon.com/robmclennan?ty=hhttps://canlit.ca/canlit_authors/rob-mclennan-2/. Accessed Feb. 13 2016. Web.

Published on May 17, 2016 05:31

May 16, 2016

Dennis Cooley, departures

because it does not hum where it turnsbecause it does not ring like glassbecause it does not sound in diapasonbecause it does not want to let things straybecause it tries to bind all thingsbecause it wants to gather them to musicbecause it blinds all creatures into believingthey might for a wisp of light slow the protein

it is not love but proportionholds them togetherkeeps them from flying apart keeps them from having to leave

yet of attraction what are we to speakif it were not for repulsionwe would pass through empty spacepass right through one anotherit is only repulsion lets us near

With his latest collection of poetry,

departures

(Winnipeg MN: Turnstone Press, 2016), Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Dennis Cooley [see my 2015 piece on him in Jacket2 here] explores “his own mortality” following a health crisis. As the online catalogue copy for the book reads: “Recovering in hospital after a burst appendix, plagued by hallucinations and poisonous mistrust, Dennis Cooley retreats to memories of ancestors and of his rural Saskatchewan roots, in departures, his 20th book of poetry.” As the collection opens: “then, Winnipeg, hospital, / the Victoria, jumbled, / didn’t know / where or when [.]”

With his latest collection of poetry,

departures

(Winnipeg MN: Turnstone Press, 2016), Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Dennis Cooley [see my 2015 piece on him in Jacket2 here] explores “his own mortality” following a health crisis. As the online catalogue copy for the book reads: “Recovering in hospital after a burst appendix, plagued by hallucinations and poisonous mistrust, Dennis Cooley retreats to memories of ancestors and of his rural Saskatchewan roots, in departures, his 20th book of poetry.” As the collection opens: “then, Winnipeg, hospital, / the Victoria, jumbled, / didn’t know / where or when [.]”Regular readers of Cooley’s work have long been aware of his expansive book-length projects, each constructed around a set of specific ideas, themes or subjects, composed as collaged-manuscripts that stitch and weave their punning and playful ways, whether writing on the foundations of civilization against his prairie in the stones (Turnstone Press, 2013) [see my review of such here], his late mother in Irene (Turnstone Press, 2000), vampire lore, literature and legend in Seeing Red (Turnstone Press, 2003), the alphabet-play of abecedarium (University of Alberta Press, 2014) [see my review of such here] or the histories and legends of Manitoba outlaw John Krafchenko in Bloody Jack (Turnstone Press, 1984; Edmonton AB: University of Alberta Press, 2002). What becomes curious, the further Cooley releases poetry collections, is the subtle evolution of his book constructions, as each collection of poems is held together through structure, theme and ideas, some of which are quite clear, and others, far more subtle. While earlier collections might have functioned more as collaged or quilted sequences, departuresmanages to exist as, deliberately, a more fragmented (and even, seemingly random) suite of predominantly-untitled poems, sketches and reports, as well as being held very close together through his ongoing meditations and inquiries, medical reports and retellings, and tweaks and quirks of language only Cooley could construct. He writes: “They enact procedures. Reduce bandages, extract tubes. Ease / the hooks, unflesh lures and barbs. Cut off the brightness, / little by little lift him off. un-net him onto water. Leave the / knife by his side.” Further, playing off the abbreviation “DNA” against “Canada,” writing a lovely, only-Cooley riff that even references, ever slightly and slyly, the work of another:

and Meganand Dianeand Danaso also an an a nada undercan ada amongthe canaanitesknown also as phoenicianswho found themselves lostat sea at a loss for words

In an interview with Jonathan Ball (dated 2003; posted 2010), Cooley talks of some of the construction of his poetry collections:

Most, if not all, of your collections are organized around a theme, concept, or semi-narrative, though you delight in diverting yourself from this loose “topic.” What is it that you find attractive about these conceptual threads, and why do you indulge yourself in digressing to such a great degree in the published work?

For me, it’s a way of generating texts. It gives me a site to research, to see what the possibilities are; there’s a kind of focus in thinking about a terrain, saying, “what can be done in this area.” I find it really generative, and because it works so well for me I always recommend it to others. Find a site, and then play off it to see what the possibilities of it might be. If you write a balloon poem, well, maybe you’re interested in doing a series, and maybe this extends into a notion of flying things, or rubber things, or symbols of innocence, or whatever—you often find all sorts of things by accident.

I got into the Dracula poems because I was writing a series of fairy tale poems, some of which became Goldfinger, and as I was reading and working there I thought, okay, well, what else might I write? and I thought of Dracula and how he was sort of a fantasy figure, and I wrote a Dracula poem, which I don’t think is in the collection now because I willfully pulled it, because there’s just so much stuff to draw from. So I wrote that and I found myself writing a bunch of Dracula pieces, they just went on and on and on, I started about 1989 I think.

departures is a collection of, as the copy says, “hallucinations and poisonous mistrust,” but also a meditative exploration of big ideas attached to a health crisis, setting his thematic boundaries and then routinely crossing them, writing his health and his history, and multiple points both aside and between. “It is not fibrous,” he writes, “there are no veins or threads. It is smooth but it is not shiny or slick. It glows it seems with its own light, light green to yellow, shape of a rootless molar. A gumdrop.” He continues: