Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 332

September 21, 2016

On beauty

Once upon a time there was a prince, who wanted to know about all the beautiful things. But he was not a prince, and, in the end, learned nothing about anything.

Once upon a time there was a prince, who wanted to know about all the beautiful things. But he was not a prince, and, in the end, learned nothing about anything.

Published on September 21, 2016 05:31

September 20, 2016

12 or 20 (small press) questions with D.S. Stymeist on Textualis Press

Textualis Press

, established in September 2014, publishes limited-edition, hand-bound poetry books on high-quality paper.

Textualis Press

, established in September 2014, publishes limited-edition, hand-bound poetry books on high-quality paper. D.S. Stymeist’s poems have appeared in numerous magazines, including The Antigonish Review, Prairie Fire, The Dalhousie Review, Steel Chisel, Ottawater, and The Fiddlehead. His work was featured as the Parliamentary Poet Laureate’s Poem of the Month (February 2015) and was short-listed for Vallum’s 2015 poetry prize. He teaches poetics, Renaissance drama, and aboriginal literature at Carleton University. He grew up as a resident of O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation, is the editor and founder of the micro-press, Textualis, and is the current vice-president of VERSe Ottawa. His collection, The Bone Weir, is forthcoming with Frontenac House.

[Textualis Press will be participating in the fall 2016 edition of the ottawa small press book fair on November 26]

1 – When did Textualis Press first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?Textualis Press started in late 2014, and its goals haven’t changed much. Give it time. On a practical level, I’ve learnt how to solicit, edit, manufacture, and distribute small books. I’ve certainly learnt that a hell of a lot of labour goes into making small books. While perhaps not strictly educational, I’ve also met and gotten to know many local writers, artists, and readers through this process; running a small press has certainly helped me become a fuller member of the Ottawa arts scene.

2 – What first brought you to publishing?I saw that a number of other small book publishers in my adopted community of Ottawa (above/ground, Apt. 9) were producing chapbooks featuring the work of local writers and deriving a lot of pleasure in the process. I wanted to escape the stultifying atmosphere of academia, serve my local community, bring new work to readers, and learn the craft of making small books. Setting up a small press seemed like the best way to accomplish all of this.

The craft aspect of small book publishing especially appealed to me. As a critic and writer, I spend far too much time in my own head, which at times can be a very inhospitable place. Book manufacture requires a special kind of manual labour, it requires focus, precision of physical movement. Through the repetitive gestures involved in the scoring of cover stock, the folding of paper, and the stitching together of chapbooks with awl, needle, and waxed cord, one enters a more meditative state. The conscious mind stops “thinking” as it becomes too involved with coordinating movement. In a way, the small book maker becomes a small machine—this is a peculiarly comforting thing to me. (I was born in Detroit, the birthplace of assembly line manufacture, so perhaps mindless industry is in my blood.)

I also became acutely aware that there were many fine poets in Ottawa who had very little publishing exposure at the small press level. I felt that if I could help to publicize and share their work, I should. Beyond providing immediate local exposure, these kind of small press books can be valuable stepping stones to larger projects and potentially enable access to trade presses and wider readership. In other words, they can help empower emerging artists.

That being said, the mandate of Textualis is not solely to foreground the work of emerging artists, but also to provide a venue for more established artists to participate in publishing in a craft form, or to publish at a local level in order to further their ties to the community.

3 – What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing? Small publishing has some natural advantages in comparison to “big” publishing. For one thing, I can use expensive paper materials and labour-intensive techniques that no commercial press could justify in the production of a commercial product. I’m not profit driven, so I don’t have to worry too much about readership and market forces—I can simply publish writing that I enjoy, that I find value in. I can only hope that others will enjoy it too.

My responsibilities as a publisher, and I think this is true for trade publishing as well as small publishing, are to provide an accurate, well-designed, attractive material vehicle for the poet’s verse.

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is?I’m not sure that any press can offer unique content or form, but I think that the experimental and avant-garde poetry communities in Ottawa are already fairly well-served. My press titles offer striking subject material thoughtfully wedded to form. The poems should be readable, apprehendable, emotive, stylistically adept, and arresting. Perhaps the press attempts to operate as a rear-guard to the avant-garde.

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new chapbooks out into the world?Readings, press fairs, social media, word of mouth, and recruiting poets who can champion their work.

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new chapbooks out into the world?Readings, press fairs, social media, word of mouth, and recruiting poets who can champion their work.6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?As an academic who has marked thousands of undergraduate essays, I’ve had to learn to step back from an overly directive approach and become more of a mid-wife, assisting the writer where there might be need. Editing, I think, at its best is a dialogic process, where there is give and take on both sides.

7 – What are your usual print runs?A typical print run is 60-80 copies. Depends on how long my particular stock of specialty paper holds out.

8 – How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?I’ve never imagined that Textualis would be a vehicle for my own writing. I don’t trust myself with my own work—I need the restraining, correcting, second-sight influence that a publishing house with professional editors provides. However, self-publishing can allow emerging and/or radical authors to have something to distribute to potential readers; this can be invaluable, for if you wait for trade presses to recognize the brilliance of your manuscript in their slush piles, you could wait a very long time indeed.

9 – What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What is your biggest frustration?I’m very proud, amazed really, with each of the little books I’ve put together. My biggest frustration is that I often have to import paper from the States, as the range of quality papers available in Canada is severely limited. Another huge frustration is finding machines that will run the cover stocks that I use without spitting them out, shredding them, our chewing them up in some inaccessible part of the printer. Oh yeah, and the price of ink cartridges—a corporate scam if I ever saw one.

10 – Who were your early publishing models when starting out?I like the whole punk DIY ethic. One of the first times I really encountered it was in San Francisco in the 80’s, where Aaron Cometbus was selling a series of little zines of his memoirs about his travels, living on the streets, and the whole bay area punk scene. The guy was a fabulous writer, and he was writing about stuff no mainstream press would touch at the time. He didn’t have access to commercial publishing, so he did it himself.

10 – Who were your early publishing models when starting out?I like the whole punk DIY ethic. One of the first times I really encountered it was in San Francisco in the 80’s, where Aaron Cometbus was selling a series of little zines of his memoirs about his travels, living on the streets, and the whole bay area punk scene. The guy was a fabulous writer, and he was writing about stuff no mainstream press would touch at the time. He didn’t have access to commercial publishing, so he did it himself. The other end of the spectrum, I do a fair bit of critical work on crime pamphlets published in Renaissance England. Predating the periodical press, these little books reported on the spectacular crimes of their day and often featured lurid woodcuts to accompany the reportage. Designed to be cheap, easily digestible, and somewhat tawdry, they were nonetheless real works of craft and artistry. The kinds of paper I use and the stitching that I do with my own press is not so far off from that which publishers from the very earliest days of print would use.

11 – How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals? At some point in the future, I will develop an online presence for the press. Have to find the time. [ed. note: he finally found the time]

12 – Do you take submissions? If so, what aren’t you looking for?At the moment, I’m not taking unsolicited submissions. The books take a considerable time to produce, and with the responsibilities of taking care of my daughter, teaching, and organizing VerseFest, I find that I can only realistically produce 2-3 titles in a calendar year.

13 – Tell me about three of your most recent titles, and why they’re special.Vivian Vavassis’ chapbook, XII does a superb job in forging coherences between short lyrical poems to construct a compelling narrative of desire, loss, and the human need to recognize and be recognized by another. She effectively weaves motifs, like the honeycomb, through an elliptical series of poems—departing from an image only to have it reappear in an altered guise.

Vivian’s imagery is particularly fresh and evocative, “Loving you, I became a long-limbed trapeze artist.”

There is much in Sneha Madhavan-Reese’s Variations in Gravity that captivates: the precision of her intellect, the range of her subject material, the care with which she uses language, but perhaps above all else, her compassion, something we’d all like to see more of in the world. I have a particular fondness for the variety of her object-poems; in “Dinoflagellates,” she describes these minute beings, on which so much life depends, with linguistic flair:

Whirling whips, these single-cell drifters flail their flagella and spin in the tide.

I’ve been a long-time admirer of Stephen Brockwell’s playful and politically pungent verse, and I think that “Where Did You See It Last” contains some of his best work. In “Marathon Water Station, 24 Mile Waypoint,” his alexandrines take longer and longer to say as the people in the race get slower and slower—this is simply a tour-de-force performance by a poet at the height of their powers. The articulation of his observations can simply knock a reader off their perch: “Old scotch strider, knobbed knees buckle under his kilt…”

12 or 20 (small press) questions;

Published on September 20, 2016 05:31

September 19, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Edward Carson

Edward Carson

, writer and photographer, is twice winner of the E.J. Pratt Medal in Poetry and author most recently of

Birds Flock Fish School

, Taking Shape and

Knots

. He lives in Toronto.

Edward Carson

, writer and photographer, is twice winner of the E.J. Pratt Medal in Poetry and author most recently of

Birds Flock Fish School

, Taking Shape and

Knots

. He lives in Toronto.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

All poetry is about persuasion.

With the experience of each new poem, we demonstrate, convince and cause both ourselves and our readers to think about, understand or believe in something. In this sense, every word in a poem changes us in small, random accumulations. A poem's insights and effects are cumulative, cyclical and emergent in nature, part of its collective interplay with words as well as its unraveling toward realizing its reason for being.

In book form, those same poems appear in interconnected series or sections where the intent and experience of the collection result in something more than the sum of its individual, poetic parts. The book expands exponentially beyond the persuasive experience of the one to the larger compelling structures of the many.

Scenes, my first book of poetry, was an unintended consequence of the fact that larger sections of it had already twice won the E. J. Pratt Medal in Poetry while I was at the University of Toronto. Nevertheless, it contained the early seeds of a continuum of thought around art and memory, the rhetoric of reason and belief, and meditations on love, intimacy and desire – themes revisited in varying forms in my subsequent books, Taking Shape, Birds Flock Fish School, and, more recently, KNOTS.

The pleasure of writing the poems and building up the books of Scenes and KNOTS was the same. The difference is one of finding new pathways to those ends.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Poetry in Canada was going through a renaissance during the 1960s. It was the transition point between two very distinct generations of writers, driven in part by the appearance of a wide range of interesting new writers, government funding, the flowering of McClelland & Stewart, and the appearance of a range of new, smaller Canadian publishing houses. Poetry simply spoke clearest to what was going on in my mind, so the writing was initially sparked by that rich, exploratory environment, and emerged gradually while at university in the 70s.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Between the publication of Scenes and my second book, Taking Shape, there was a gap when I experienced a writer's block of over thirty years. I made good use of that time, serving as president of several book publishing companies, including Penguin Canada, Pearson Technology Group Canada, Distican (Simon and Schuster), HarperCollinsCanada, and, while Vice President of publishing, founded the successful indigenous publishing list of Random House of Canada. Thirty years on, the writing of Taking Shape began with my decision to leave publishing. Go figure. I'm still writing.

Since that thirty-year gap, writing has been a daily activity, which means I don't rely only on an inconsistent muse to inspire . . . Writing is a discipline, and I work at it (which is more pleasing than it sounds). Infrequently, some poems spill out complete in an hour, while most can take shape over days or weeks of editing and re-writing. I always have a few different poems on the go at the same time, some of which survive the edits/additions to completion while pieces of abandoned poems are pulled apart and find a home in different poems.

Most people think poets have it easy over fiction writers because of length. Not so. The average poem can go through multiple re-writes and edits. Fifteen, twenty, thirty versions is not out of the question. With an average 70-80 poems per book, I'd say we easily produce in the rage of 500 to 600 pages of work that is ultimately boiled down to 100 pages or less.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem usually begins the same way . . . typically with an opening two-line stanza involving a key image, metaphor or simple observation. From there the poem gradually emerges, building/editing stanza on stanza until completed. This approach was true for the last three books, though for KNOTS I then expanded or condensed the word/line spacing as well as the organizing principles of that original two-line stanza structure.

Each poem can stand alone, but in my mind it also is part of a larger frame of reference, either as a poem sequence, part of a book section, or the book as a whole. For me, that larger frame of reference is grounded primarily in two counter-balancing principles of structure and organization that simultaneously support and oppose each other as well as provide a potent mix of stability and change: (1) Ciceronian rhetoric, specifically its more formal organizational structure of five component parts critical in the art of persuasion, and (2) the self-organizing and adaptive learning processes in language as best understood through the science of emergence.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy public readings, mainly because they are the closest to unfiltered feedback from the intended audience.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

A poem can be thought of as a snare for thinking. Offering neither clear answers nor resolutions, its puzzle/riddle-like quality has the form or force of a question where the answer is contained within the question. It doesn’t provide directions, but rather presents predicaments the reader alone must encounter and interpret. What a poem does is find itself from the inside out; its centres of thought draw together its periphery, giving birth to the force of reciprocal influences. The complex of words and syntax of a poem rearranges fixed ways of understanding what is happening by actively undermining and then re-building relationship and presence, time and perspective. You can’t understand just one thing for long; your mind must wander endlessly in search of a way out.

The experience and interpretation of a poem is not entirely cumulative, but cyclical, and, to a certain degree, repetitive and recursive; it is repeatedly interrupted and rearranged by new, iconoclasticdiction and syntax. A poem acts as a kind of social substitute; it is a mediated world in which our thinking, comprehension and emotional attachments are remade, re-formed, and integrated into a new perception of our world and our place in it. In uncovering thoughtful meaning in the obvious, a poem needs clear communication and persuasion as well as distortion and deception; it is also seductive in that it reaches out to those things we fear and crave the most: loneliness and intimacy. In the end, a poem is never present in itself, but always at large in the mind of the reader.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

The role is simply to write. Any attempt to assume a role beyond writing will poison the well.

Culture will take and absorb what it wants/needs from you, without particular regard to what you think that should be.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

The best editors are the ones whose work is essential to a better reading experience while being invisible in the writing itself.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

It's a waste of emotions to answer critics; better to stay in print long after they are dead – Nassim Nicholas Taleb

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to visual art)? What do you see as the appeal?

More often than not, moving between my art and poetry is a question of relief. Each time I switch it's like a vacation from which I return refreshed and ready to begin again. I find the integration of the written word and visual image as co-dependent and deeply related. Like physics or good conversation, that which is most pleasing, intelligent and entertaining in a poem or work of art often depends as much on what is missing as what is actually there. The ambiguity of empty space – on the page or canvas – defines what must occupy that space, while the silences embracing our words or the absences in the visual art create questions and teach us the luxury and balance of knowing little while assuming much more.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

A couple of hours every day, whether I want to or not. It can be spread in smaller time slots, though rarely in the morning. I'm one of those blessed/cursed people who need only a few hours of sleep, so usually late at night when the house is quiet.

Because I tend to work on two or three poems at once, I'm always beginning my routine in the middle of something not yet finished. New beginnings almost always appear while writing/editing for one of the other poems already in progress.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Other than that 30-year writer's block mentioned in Question #3, I'm now rarely stalled . . . because I work at it, even when nothing seems to work, and, as mentioned in the last question, I'm always working on several poems at once.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

"Gapbody Raincheck", which has been discontinued by Gap and has remained unavailable for years. I keep hidden away what must be the last bottle of it anywhere . . . brought out only for select jazz concerts or family celebrations. As I write this, a social media movement is beginning to take shape to petition the president of Gap to re-introduce this scent to a public much in need of its effects.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

All of those mentioned in the question.

Other writers' poetry nudges me more than it inspires, though Wallace Stevens always explains everything.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I love books that break new ground or completely challenge how we think . . . Like Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, or Moby Dick. Of course, anything by Shakespeare or Dickens.

What I really enjoy is "big idea" nonfiction by the likes of Marshall McLuhan, Susan Sontag, Henry Petroski, Roger Martin, Clay Shirky, Nate Silver, Don Tapscott, Steven Johnson, James Surowiecki, Sherry Turkle, Nicholas Carr, Richard Thaler, John Brockman, Daniel Kahneman, Christopher Hitchens, Malcolm Gladwell, Neil Postman, James Gleick, Barry Schwartz, and Carl Honore.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Travel in space . . . See the earth from the moon. Weightlessness.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A brain surgeon.

During the early 1960s there was a program called, if memory serves, "Medic 61". It was ground-breaking at the time because it showed actual operations, including cutting, blood, clamping, etc. The very first show was a brain operation where they drilled (using what looked like a carpenter's u-shaped wood hand drill) into he skull, and then inserted electrified rods into key areas of the brain to eliminate or reduce the shaking of Parkinson's disease. Magic.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

The pleasure of it, of wrestling a poem to the ground until it speaks to what it was always intended to say. Most days, the surprising outcome of that effort comes close to pure satisfaction.

The Way a Poem Knows

Something about the way a poem knows,

something that keeps us reaching into it

from a place of dreaming not unlike this.

The poem calls and sets a path in the dark

and lights fields of our belief. The poem sees

the truth in the telling is not revealed in what

it doesn’t know, but in finding itself

released like a stream from its knowing.

Something about the way a poem finds

its place in our minds, something that finds

the truth of what is meant to be but harder

still to say. Something about a poem that asks

and answers, setting loose the slow riddle

of its voice, something it freely confesses

to knowing, like the clear thread of this portrait

about to discover the way a poem finds its end.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Last great poetry book was Kay Ryan's The Best of It. Last great nonfiction was Kahneman's Thinking, Fast and Slow.

As the idea of "movie" becomes more a part of the next golden age of TV/online streaming, effectively changing the medium, I have to say there can't be just one . . . True Detective, The Knick, Borgen, Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones.

20 - What are you currently working on?

Next book of poems, titled Push & Pull . . . Next art show . . .

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 19, 2016 05:31

September 18, 2016

Profile on Show and Tell Poetry Series, with a few questions

My short profile on Justin Million and Elisha May Rubacha's Show and Tell Poetry Series (Peterborough ON) [thanks to Jenn Huzera for the photo) and small press

bird, buried press

, along with a few questions,

is now on-line at Open Book: Ontario.

My short profile on Justin Million and Elisha May Rubacha's Show and Tell Poetry Series (Peterborough ON) [thanks to Jenn Huzera for the photo) and small press

bird, buried press

, along with a few questions,

is now on-line at Open Book: Ontario.

Published on September 18, 2016 05:31

September 17, 2016

Anne Guthrie, The Good Dark

*

breaking what it needs,digestion, the nourishment process

could be a good model

so on doors I pluck for sound, and outof varying instruments

blender, mouth of bronze idol on mantle, mouthcolor, interpret: vandalize:

In the “Foreword” to Tucson, Arizona poet Anne Guthrie’s new poetry title,

The Good Dark

(North Adams MA: Tupelo Press, 2015), poet and critic Dan Beachy-Quick writes that the book “[…] offers itself as a curious testament to the labyrinthine complexity of human relation to the world and those others that fill it. For in the poems there are powers, there are forces, there are laws, but none of them exert an authority that removes the poet from her need to write so as to listen: ‘sometimes it admits you its existence.’ That existence is manifold. There is nature, and there is God, and there is the gossip between them that the human ear eavesdrops upon; there is also the human, relations of body to body, and convolutions of heart to mind and mind to heart that understand love’s reciprocity is a confounded, confounding form.” A bit further, his introduction ends:

In the “Foreword” to Tucson, Arizona poet Anne Guthrie’s new poetry title,

The Good Dark

(North Adams MA: Tupelo Press, 2015), poet and critic Dan Beachy-Quick writes that the book “[…] offers itself as a curious testament to the labyrinthine complexity of human relation to the world and those others that fill it. For in the poems there are powers, there are forces, there are laws, but none of them exert an authority that removes the poet from her need to write so as to listen: ‘sometimes it admits you its existence.’ That existence is manifold. There is nature, and there is God, and there is the gossip between them that the human ear eavesdrops upon; there is also the human, relations of body to body, and convolutions of heart to mind and mind to heart that understand love’s reciprocity is a confounded, confounding form.” A bit further, his introduction ends:Guthrie writes a last line that doesn’t illuminate all those that came before. Better, it holds within the various darknesses in which this book does its utmost work. “It was this kind of human,” she says; and reader, I hear it thus: kind as type, and kind as adjective. This kind of human, this poet kind, gives us this kind book in which the difficulty we fear to admit that we are our own living example of will be tender to us even as we tend toward it, word by word, line by line, poem by poem, letting our vision adjust to the good dark.

Composed in four lyric sections – “unwitting,” “chorus,” “body” and “epilogue” – Guthrie’s The Good Dark is constructed out of a sequence of short, stand-alone fragments, similar in tone with a content shifting around the lyric “I” and a conversation around the divine, from the natural to the deeply personal; of “dusk, grasses wind the hymn” and “like a river stepped in by mistake” to “sometimes shadows become articulate[.]” Her poems move from the clipped fragment to the stanza, writing out an intimate space of self, the body, memory and the spirit, yet there are places where I wish her lines were just a bit tighter than they are. Otherwise, the flow here is lovely, even if her lyric is occasionally unclear.

* the gossip

When she was a girl she was an inventor.Lies would fly out of her mouth, bright world, bright wings.At first the children would flock to her like a colorful mother.But then the room took on the other hue,and feeling the feel of too-heavy wings, the too-heavy birdfluttered and tottered and fell.

Published on September 17, 2016 05:31

September 16, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Dean Steadman

Dean Steadman’s

work has been published in Canadian journals and e-zines, as well as in the anthology

Pith & Wry: Canadian Poetry

, edited by Susan McMaster (Scrivener Press, 2010). He is the author of two chapbooks: Portrait w/tulips(Leaf Editions, 2013), and Worm's Saving Day (AngelHousePress, 2015). He was a finalist in the 2011 Ottawa Book Awards for his poetry collection,

their blue drowning

(Frog Hollow Press, 2010). His second poetry collection,

Après Satie – For Two and Four Hands

, was published by Brick Books in the spring of 2016.

Dean Steadman’s

work has been published in Canadian journals and e-zines, as well as in the anthology

Pith & Wry: Canadian Poetry

, edited by Susan McMaster (Scrivener Press, 2010). He is the author of two chapbooks: Portrait w/tulips(Leaf Editions, 2013), and Worm's Saving Day (AngelHousePress, 2015). He was a finalist in the 2011 Ottawa Book Awards for his poetry collection,

their blue drowning

(Frog Hollow Press, 2010). His second poetry collection,

Après Satie – For Two and Four Hands

, was published by Brick Books in the spring of 2016.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?The publication of my first book, their blue drowning, gave me confidence in my talents as a poet. Up to that point, I had had some small success in getting individual poems published in magazines and journals, but the rejection letters far exceeded the letters of acceptance. A bit demoralizing. However, the publication of their blue drowning changed that for me and gave me reason to continue to develop the voice that was beginning to emerge in my poetry. The book received very little critical attention, although I am proud to say that it was nominated for the 2011 Ottawa Book Award for English fiction. That was as good as a win for me and, with that encouragement, I went on to write two chapbooks and the collection, Après Satie – For Two and Four Hands. I’ve been told by fellow writers that Après Satie marks a new stage in my development as a poet. I see it as a departure from the big-picture, mythological worldview of their blue drowning. It’s much more surreal in tone and heavily flavoured with a Dada sensibility that tends to give the collection a feeling of the absurd.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?I’m an avid reader of novels and short-stories. I probably read more prose fiction than I do poetry and almost everything I write has a narrative flow to it. But it’s the concentration and precision of poetry as a literary form that attracts and challenges me as a writer. Poetry allows me to explore the same themes that I would as a novelist or short-story writer but, as an art form, it imposes constraints in terms of time and space. These constraints push me beyond the linear continuity of most prose fiction into a creative discipline where the devices and techniques at my disposal work to impede normal perceptions and disrupt habitual ways of thinking and seeing. The Russian formalist Viktor Shklovskywrote: “[A]rt exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. The technique of art is to make objects “unfamiliar,” to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.” I think that this is particularly true of poetry, or, at least, the kind of poetry that interests me. Certainly, prose fiction can achieve these same results, as novelists such as Elizabeth Smart and Michael Ondaatje have skillfully demonstrated. But even then we tend to think of such works as “poetic prose” which for me is recognition of poetry’s inherent ability to make “strange and wonderful,” to use Aristotle’s description of poetic language.

3 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?I’ve been interested for some time now in studying the characteristics that distinguish poetry from prose fiction, and to some extent this has spilled over into my poetry. I think such an investigation is essential to formulating a personal poetics. The collection, their blue drowning, was in some ways an exercise in exploring this topic. There I used a prose “chapeau” with each poem to make the storyline more accessible to the reader, often pushing the prose as close to poetry as possible and, likewise, letting the poetry drift away from metaphor into something closer to the denotative language common to much prose fiction. Après Satie is also concerned with poetic language and with what distinguishes it from denotative language. A few years back I started delving into the different schools of literary theory and my studies have provided me with a wealth of insight into the functions and functioning of language. Some of the poems in Après Satie give poetic expression to the linguistic theories I’ve come across, particularly those advanced by the literary formalists and the structuralists of the last century.

4 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?Working with talented editors has been my most positive learning experience as an emerging poet. I came to writing poetry in earnest in my late fifties after retiring from a lengthy career in areas of international trade policy with the federal government. I had a lot to learn quickly and benefited greatly from two sessions of the Banff Wired Writing Program where I had the very good fortune to work on early versions of their blue drowning, first with Don Domanski and then with Stan Dragland as my mentors. I learned more about poetry from those two than I could even begin to describe and the editorial advice they provided resulted in the manuscript being accepted for publication by Frog Hollow Press. At Frog Hollow, I worked with Shane Neilson to fine tune some of the poems in ways that never would have occurred to me without his assistance. Stan was also very instrumental in helping me to prepare Après Satie for submission to publishers and, when it was accepted by Brick Books, I worked with Sue Chenette, another very gifted editor, not to mention a wonderful poet in her own right. I owe all of these people a huge debt of thanks for making me look more talented than I am. And there are others who in workshops and writing circles have helped as well, including a young man you may know named rob mclennan.

5 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?During my first session of the Banff Wired Writing Program, I learned two important writing mantras: 1) Get out of the way; 2) Show up for work. Inspiration will provide a starting point but poems are written during the editorial process and, unless you’re extremely lucky, will require numerous sessions of writing and rewriting.

6 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?I’ve touched a bit on this already. For me, the role of the writer, particularly the poet, is to defamiliarize the familiar. I’m most satisfied with my work when it presents objects and experiences from an unusual perspective or in such unconventional and self-conscious language that the reader’s habitual, ordinary, rote perceptions of those things are disturbed. As linguists and psychoanalysts, such as Roman Jacobson and Jacques Lacan, conjectured during the last century, language makes us, or perhaps more accurately, language thinksus. Reality for humans is “textual,“ Jacques Derrida concluded. But when our use of language becomes stale and automated, life is reckoned as nothing. Poetry, however, works to create the vision that results from de-automatized perception so that, as quoted earlier, “we may recover the sensation of living.” Boris Eichenbaum, another of the Russian formalists, wrote in one of his early essays on poetic language: “Art is conceived as a way of breaking down automatism in perception and the aim of the image is held to be, not making a meaning more accessible for our comprehension, but bringing about a special perception of a thing, bringing about the “seeing” not just the “recognizing” of it.” I can’t say it better than that.

7 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?I’m very much an intuitive writer and my initial (Banff) approach to a new poem is to get out of the way and let the poem take its own course. That is to say, I don’t start out with any specific thematic content or set objective in mind and, as a result, the initial stages of writing a poem are for me as much a journey of exploration and discovery as the experience of the finished poem is for the reader or listener. I find the process of writing poetry to be something analogous to dream and the interpretation or analysis of dreams. The initial sitting involves an outpouring of the unconscious mind that provides me with material that I don’t fully understand but can shape with the devices of poetic language into something meaningful during the editorial process. It is at this stage that my conscious mind goes to work to detect what might be a plausible interpretation of the dream-like narrative with which I’ve been presented. Interestingly, the interplay between the unconscious and conscious minds continues throughout the editorial shaping of the poem with the result that the finished poem is without fail considerably different from the initial composition. It can be a slow process but it’s a process I find so fascinating that I’m convinced it’s one of the main reasons I continue to write poetry.

8 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?Reading is my main source of inspiration. “Poetry envy” can be a great motivator. Freud had it all wrong.

9 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I tend to write daily (an advantage of being retired) and, as part of my Banff work ethic, I’m typically at my desk by 8:00 am. The idea for a new poem or solutions to problem areas in whatever it is I’m working on at the time often come to me in the night during that semi-conscious state between waking and falling back to sleep. I usually manage to jot these down before they slip from my mind and then, if I can read my writing, use them to kick-start my morning routine. Continuity during the writing and editing stages of a poem is very important to me. There’s a critical mass that builds with each writing session and I find that disrupting this momentum for any length of time can set back the completion of a poem considerably. The length of my daily writing sessions fluctuates widely. The economic analyst in me is still at work and recognizes that there’s a law of diminishing returns to the creative process.

10 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?I might use an open-mic opportunity to test a new poem for its rhythm and flow and then follow-up by correcting anything that felt awkward. I read my poems aloud to myself during their composition but there is an altogether different dynamics to a public reading that can be very useful as an editing tool. The public readings I’ve done to launch or promote their blue drowning, Après Satie, and the two chapbooks have, of course, occurred after publication and have not fed into the creative process per se. But they have provided occasion for a more theatrical type of creativity and I’ve come to enjoy bringing my poems to life for an audience and presenting them in the manner I want them to be heard. On several occasions, I’ve had other poets join with me in a more orchestrated kind of reading of my work. It makes for an interesting effect and demonstrates, I think, poetry’s natural affiliation with music.

11 - What fragrance reminds you of home?Apple. Possibly a biblical (Genesis) thing. Definitely Lacanian.

12 - What are you currently working on?A Dell Inspiron 15R. Although I’m thinking of switching to Apple.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on September 16, 2016 05:31

September 15, 2016

new from Apostrophe Press: A perimeter, by rob mclennan

If anyone is interested, I have a couple of copies left of this limited-edition chapbook, an excerpt of my forthcoming poetry title with New Star (October).

A perimeter

rob mclennan

$4

A

The property boundary is handmade (shared). Fluid,

and only fluid. Unless

you know precisely where. The skin

and space of white noise (hearth). One hundred foot of fence.

Language is impermanent. We retain nothing, have no

specific form. The latent grass, explode; infect

the yard and underneath the stone-work.

The neighbour’s garden, glistens. Scars. We translate always

from another.

B

Confirm

my personal association. The lawn requires trim,

and so it does.

A sanity short of despair. Lawn ornaments

are temporal. And yet: this sky of relative divergence

upon the written word, my daughter’s

childhood memories. What separates us

no more a thickness

than this house brick. At best, let’s say.

published in Ottawa by Apostrophe Press

September 2016

published in Ottawa for the author’s Patreon supporters, as well as for limited distribution as part of the above/ground press 23rd anniversary reading/launch/party at Black Squirrel Books, Ottawa, September 10, 2016, and PHILALALIA, the three-day small press/art fair, September 15-17, 2016 in Philadelphia PA. Thanks much to Kevin Varrone for his help and support.

The poem “A perimeter” is the title poem from a new poetry title to appear this fall from New Star Books, Vancouver.

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; outside Canada, add $2) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9 or paypal at www.robmclennan.blogspot.com

Published on September 15, 2016 05:31

September 14, 2016

new from above/ground press: Pirie, Bök, Flowers, Collis, Yalen + Beaulieu,

sex in sevens

sex in sevensPearl Pirie

$5

See link here for more information

10 Poems

Christian Bök

$4

See link here for more information

TAXICAB VOICE

Neil Flowers

$5

See link here for more information

NEW LIFE

Stephen Collis

$4

See link here for more information

Partial List of Things I'm Responsible For

Lesley Yalen

$4

See link here for more information

ERASURE: A Short Story

Braydon Beaulieu

$4

See link here for more information

keep an eye on the above/ground press blog for author interviews, new writing, reviews, upcoming readings and tons of other material;

published in Ottawa by above/ground press

June-September 2016

a/g subscribers receive a complimentary copy of each

and watch for the 2016 above/ground press subscriptions, available soon! and did you see the recent reports on the 23rd anniversary events held in Toronto and Ottawa ? Twenty-three damned years! God sakes. And less than twenty titles away from an accumulated EIGHT HUNDRED TITLES. Oh, and one more day to go in the Touch the Donkey [a small poetry journal] back issue sale!

To order, send cheques (add $1 for postage; outside Canada, add $2) to: rob mclennan, 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9 or paypal (above). Scroll down here to see various backlist titles (many, many things are still in print) . and, in case you missed it, here is a list of the spring 2016 titles as well.

Review copies of any title (while supplies last) also available, upon request.

forthcoming chapbooks by George Bowering, Geoffrey Young, John Barton and Carrie Hunter, as well as issue #11 of Touch the Donkey, and watch for a new “poem” broadsheet on the blog soon by Nathan Dueck!

Published on September 14, 2016 05:31

September 13, 2016

Guthrie Clothing: The Poetry of Phil Hall, a Selected Collage, reviewed at The Bull Calf

Guthrie Clothing: The Poetry of Phil Hall, a Selected Collage

, with an introduction by rob mclennan (WLU, 2015) [see my Jacket2 piece on working the project, here], is reviewed over at The Bull Calf by Luke Stark. Thanks much! And, by the by, you should totally order a copy.

Guthrie Clothing: The Poetry of Phil Hall, a Selected Collage

, with an introduction by rob mclennan (WLU, 2015) [see my Jacket2 piece on working the project, here], is reviewed over at The Bull Calf by Luke Stark. Thanks much! And, by the by, you should totally order a copy.

Published on September 13, 2016 05:31

September 12, 2016

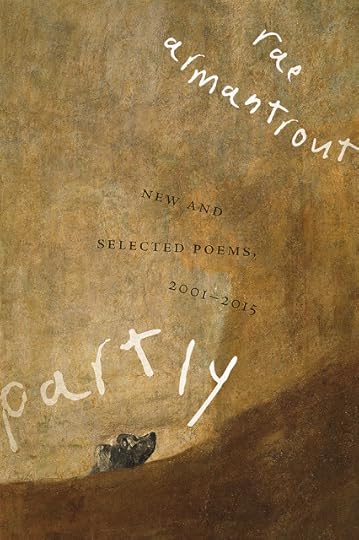

Rae Armantrout, Partly: New and Selected Poems, 2001 – 2015

Partly

In this adfor Newfoundland,an old womansteps onto the porchof the lone houseon a remote coveand shakes a white sheetat a partly cloudy sky

as if

~

Matched burgundy berrieson adjacent stems,

perfect ear bobs,

with no onewearing them

San Diego poet Rae Armantrout’s latest collection,

Partly: New and Selected Poems, 2001 – 2015

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2016), provides a portrait of the award-winning poet’s past decade and a half, following on the heels of her first selected poems,

Veil: New and Selected Poems

(Wesleyan University Press, 2001). I’ve complained enough over the years about editions of selected and/or collected poems that lack introductions, so I’ll skip over that for now. Given that this is her second selected poems, one that deliberately begins after the previous one ends (I suspect, in part, because that other title is, one can happily inform, still in print), one of the curiosities of this new title is in how it allows readers of her work, both new and old, to be more aware of some of the shifts in her poetry over the years, and even between the two books themselves (oh, had only someone covered such in an introduction!). There is certainly a finer precision and density to her poems in the years since Veilappeared, one that has deepened with each new collection. Her poems revel in the indirect line presented in the most direct way possible, writing to the heart of a particular matter that might not have been immediately revealed, or even clear. Her poems meander in such a straightforward way that they become remarkably easy to misread, and yet, the simplicity is but one of precision, not ease; of an ellipsis that might lead to clarity, but not through the straight or obvious path. Her poems lead us to such places we don’t realize until we’re already there. In his “Foreword,” to Veil: New and Selected Poems, “‘Aloha, Fruity Pebbles’: The Poems of Rae Armantrout,” Ron Silliman provides a worthy overview of Armantrout’s work up to that point, writing:

San Diego poet Rae Armantrout’s latest collection,

Partly: New and Selected Poems, 2001 – 2015

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2016), provides a portrait of the award-winning poet’s past decade and a half, following on the heels of her first selected poems,

Veil: New and Selected Poems

(Wesleyan University Press, 2001). I’ve complained enough over the years about editions of selected and/or collected poems that lack introductions, so I’ll skip over that for now. Given that this is her second selected poems, one that deliberately begins after the previous one ends (I suspect, in part, because that other title is, one can happily inform, still in print), one of the curiosities of this new title is in how it allows readers of her work, both new and old, to be more aware of some of the shifts in her poetry over the years, and even between the two books themselves (oh, had only someone covered such in an introduction!). There is certainly a finer precision and density to her poems in the years since Veilappeared, one that has deepened with each new collection. Her poems revel in the indirect line presented in the most direct way possible, writing to the heart of a particular matter that might not have been immediately revealed, or even clear. Her poems meander in such a straightforward way that they become remarkably easy to misread, and yet, the simplicity is but one of precision, not ease; of an ellipsis that might lead to clarity, but not through the straight or obvious path. Her poems lead us to such places we don’t realize until we’re already there. In his “Foreword,” to Veil: New and Selected Poems, “‘Aloha, Fruity Pebbles’: The Poems of Rae Armantrout,” Ron Silliman provides a worthy overview of Armantrout’s work up to that point, writing:In this sense, Armantrout belongs to what might be characterized as the literature of the vertical anti-lyric, those poems that at first glance appear contained and perhaps even simple, but which upon the slightest examination rapidly provoke a sort of vertigo effect as element after element begins to spin wildly toward more radical (and, often enough, more sinister) possibilities. Armantrout’s ancestors in this are not so much Lorine Niedecker, with whom she has been compared more than once, nor her teachers such as Denise Levertov, but rather Jack Spicer, Emily Dickinson, and Arthur Rimbaud. It is pointless to characterize Armantrout’s writing as surreal as it is to identify it as an instance of language writing. Nowhere else in either tendency is there anything quite like these works. If they are often disturbing in their subtextual resonances, these poems are also remarkably cheerful and good-natured, written with an ear for (and eye to) American popular culture that is the most acute in contemporary poetry. Imagine David Lynch as rewritten by Frank O’Hara and you’ll be somewhere in the ballpark, except that Armantrout’s work lacks the claustrophobic mannerism of the former and the casualness (feigned or otherwise) of the latter.

Partly: New and Selected Poems, 2001 – 2015 spans the distance of her six trade collections produced since Veil: New and Selected Poems—all of which appeared with Wesleyan University Press— Up to Speed (2004), Next Life (2007), Versed (2009), Money Shot (2011), Just Saying (2013) and Itself (2015), as well as an opening section of some fifty pages of new material (including the title poem). Whereas considerations of culture, history and the larger world have long been part of her ouvre, her work since Veil has become more focused, tighter: more precise. As the collection Money Shot, for example, referenced the American financial crises, Just Saying explored the complex nature of the American economy. Part of the joy and play of Armantrout’s work, something referenced obliquely through this new book’s title, is in how she seems to revel in the fragment, whether the line or the stanza, employing thoughts that aren’t necessarily incomplete, but certainly thoughts that aren’t articulated out loud in their entirety, allowing or even forcing the reader to pay a far deeper attention. She writes in fragments, and yet, everything manages to interconnect, as she writes in the title poem from Up to Speed: “The Sphinx / wants me to guess. // Does a road / run its whole length / at once?” Armantrout writes so precisely and articulately about what might not be possible to precisely articulate. What does that even mean? Do you know what it is she stopped just short of telling us?

Approximate

Wait, I haven’t foundthe right word yet.

Poem meanshomeostasis.

“Is as”

As is

Film is enoughlike death.

In a bright lightat the far end,attractive strangers gesture.

They are searchingthe systemfor systematic threats.

I was goingto pay attention.

Attention passesthrough a long cord

into the pastprogressive

Published on September 12, 2016 05:31