Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 330

October 11, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Carolyn Ann Hembree

Carolyn Hembree

was born in Bristol, Tennessee. Her debut poetry collection,

Skinny

, came out from Kore Press in 2012. In 2016, Trio House Books published her second collection,

Rigging a Chevy into a Time Machine and Other Ways to Escape a Plague

, selected by Neil Shepard for the 2015 Trio Award and by Stephanie Strickland for the 2015 Rochelle Ratner Memorial Award. Her work has appeared in Colorado Review, Gulf Coast, The Journal, Poetry Daily, and other publications. She has received grants and fellowships from PEN, the Louisiana Division of the Arts, and the Southern Arts Federation. An assistant professor at the University of New Orleans, Carolyn teaches writing and serves as poetry editor of

Bayou Magazine

.

Carolyn Hembree

was born in Bristol, Tennessee. Her debut poetry collection,

Skinny

, came out from Kore Press in 2012. In 2016, Trio House Books published her second collection,

Rigging a Chevy into a Time Machine and Other Ways to Escape a Plague

, selected by Neil Shepard for the 2015 Trio Award and by Stephanie Strickland for the 2015 Rochelle Ratner Memorial Award. Her work has appeared in Colorado Review, Gulf Coast, The Journal, Poetry Daily, and other publications. She has received grants and fellowships from PEN, the Louisiana Division of the Arts, and the Southern Arts Federation. An assistant professor at the University of New Orleans, Carolyn teaches writing and serves as poetry editor of

Bayou Magazine

.1 - How did your first book change your life?

I sent my first poetry manuscript, Skinny, to contests and open reading periods for ten years before Kore Press made it a book in 2012. Cracks of lightning, too, lit that decade-long night of rejection; journals and anthologies printed the poems individually, and the manuscript was a bridesmaid in several contests. (Those modest gowns cost money though.) In sum, I felt gratitude for the book’s acceptance. Practically speaking, the book’s publication weighed in my University’s decision to promote me to a tenure-track position; the course release and raise have made life easier.

How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Both books evoke the South and a kind of isolation. The first book exists inside of a dream, not to be helped. No single voice is entirely drawn: all share a telephone party line, snatches of this and that mesh to form a psychology. The second book, Rigging a Chevy into a Time Machine and Other Ways to Escape a Plague, winner of the 2015 Trio Award and the 2015 Rochelle Ratner Memorial Award, feels denser, I suppose. For one, the landscape becomes a character as much as any soul. Doctrine I absorbed in the Presbyterian Church my family attended shows in a fatalism, an inevitability, a finish of the second book. To my mind, the first remains more in the air.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

In an effort to check my juvenile delinquency, my parents sent me to an evangelical school for the ninth grade. Naturally, my nefarious activities increased in the authoritarian atmosphere, where I quickly found coconspirators with whom to share earbuds during morning prayer (Mötley Crüe’s “Shout at the Devil” our go-to, obviously), to drink vodka during PE, to disrupt assemblies—whether by inciting a chant to call out the tuba player who masturbated under his band jacket during pep rallies or making infant cries during cautionary abortion films. Needless to say, I only attended the school one year. Aside from the fun, this Advanced English teacher, Mrs. Bolla, had us write poems. Mrs. Bolla, who only allowed herself a reading list befitting a conservative Christian woman, pulled my despairing rhymes from the bunch and showed them to her friend, a bona fide poet who sent a gentle and encouraging letter my way. That was all I needed.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It takes years with stops and starts for research, drafts, rewrites, and final edits across the manuscript to unify motifs and excise overused language. All in all, the second book, a modest 72 pages, took thirteen years, thereabouts.

For any given poem, I start with 100 pages of words: research notes, model syntax, observations, snatches of overheard conversation, images, and so on; this mother document, as it shrinks and expands, serves me for the whole book. I reduce the words the way I imagine a sculptor reduces a block of stone. By the time one emerges, the poem usually knows its shape.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

With a few exceptions, I work on books even if the “project” later becomes a single poem.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

My acting training informs my natural yet dramatic presentation of the poems. Because I want listeners to have a different experience than they would reading my work, I try to create various narrative, lyric, and rhetorical trajectories through my selection and arrangement of pieces; this preparation requires creative thinking. Yes, the readings serve as part of my creative process, and they run counter to my process. Readings allow me to meet my real audience, which colors the intended audience (the dead, a former self, other poets mainly the dead for me) when I return to the page. So, meeting people who read my work enriches my understanding of audience, a good thing. When I was younger, I could get paralyzed for days after a reading if, say, an older gentleman felt called upon to tell me how valueless he found my work. Now, I’ve learned to better avoid such interactions.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’m always asking what’s my stake in a thing. A narcissistic creature, I know to be savage with myself, my perceptions, my values. As default practice now, I write the opposite of all direct statements. When I studied under Jane Miller at the University of Arizona, she emphasized the paradox inherent in much poetry, an idea central to my poetics. Yes, I occasionally try to answer questions with the work; Chevy closes with a series of poems titled with questions Stephen Hawking has posed about the nature of time. These questions prompted me to explore Appalachian folklore that addresses the progress of existence, as well as collective and personal memory.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Do our roles now differ from back when? Artists are the true historians. Stevens’ “The Idea of Order at Key West” comes to mind: “And when she sang, the sea, / Whatever self it had, became the self / That was her song, for she was the maker.” I believe in the longevity of our art, in the contribution of folks of all stripes, public poets and private ones. I give thanks for this golden age. Yet I can only dictate my role, and “my business is Circumference,” as Dickinson wrote.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. By the time an editor lays hands on my work, I have so excoriated it that I welcome outside input. I also have incisive readers who work me over before an editor enters the picture.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Well, I’m not going to offer one “best” (Circumference, you know):

“Stay upset.” –Brenda Hillman

"Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better."—Samuel Beckett

“You are a poet all of the time.” –Jane Miller

“... nothing could be ruined in one stroke.” –Elizabeth Alexander

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I do not move between genres, not to say that I will not.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I get my kid ready in the morning, alternate transporting her to school/camp with my spouse, practice yoga, meditate, then read and write for two hours. Usually, I have to get on with teaching or lesson preparation at that point. However, during the summer months, I’ll take a walking break after two hours then write for another one or two. As I have zero impulse control, I keep all distractions at bay during my writing time by blocking the Internet and silencing my phone.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Since my process accommodates alternating periods of research and periods of writing, I tend not to get too stalled. When I was younger, blocks occurred more, but now I better understand, for good and ill, how my imagination works, that my mind has to wander, to meander, to steep.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Blue Grass dusting powder, Halls cough drops, Granny’s beef stew, damp books, honeysuckle, elms. There was an apple tree, so a cooking-apple tree in bloom. I’ve had many homes though. New Orleans now. And what does New Orleans not smell like?

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

To return to Jane’s advice on being a poet “all the time,” I try to stay alert to everything: when visiting a museum, walking my neighborhood, eavesdropping in the grocery line, listening to traffic, watching trash television, reading an anthropology article. ... Aside from reading, I get a tremendous lot from interviews of survivors of violent crimes. What interests me – how we attempt to verbalize the unutterable: idioms get mixed, banal phrases repeated, and dialogue recalled precisely.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Dickinson, Donne, KJV Bible, early anonymous ballads, Shakespeare, Etheridge Knight, John Berryman, C.D. Wright, Harryette Mullen, Claudia Rankine, Beckett, Kafka, Faulkner, Chekhov. I don’t have a reading life outside of my work.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Quit.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’ll go with the latter question: prosecuting attorney, missionary, literary agent, improvisational actor, or circus contortionist.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It stuck around.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: The Descent of Alette . Movie: The Act of Killing .

20 - What are you currently working on?

Two books of poetry: one a book-length project, one in loose pages. As my middle-aged great-grandmother –women from my line, we’re small-framed with prodigious stomachs – when asked by a neighbor if she was pregnant (she was not) responded, “Only time will tell, only time will tell.”

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 11, 2016 05:31

October 10, 2016

On beauty

She knew the only way to prioritize was to record everything. She had to make a list. She wrote everything down, constantly adding and shifting items. Put up the fence. Get the roof fixed. Take the car in for maintenance. Snow tires. Paint the walls of the nursery. All before the baby arrived. As the list progressed, it became less a sequence of tasks than a wish-list. Catch up on reading. Meet up with friends. Sort out the garage. By the time she’d entered her third trimester, the list had become a bit anxious, given how few entries had been completed, and crossed-off. Sign up for swim lessons. Talk to her father. Travel. As she approached labour, the list had taken on an abstract quality. Breathe more. Walk along the canal. Notice the moon. As our first-born began to crown, she happened to glance up through the hospital window and there was the moon, full and round and constant.

She knew the only way to prioritize was to record everything. She had to make a list. She wrote everything down, constantly adding and shifting items. Put up the fence. Get the roof fixed. Take the car in for maintenance. Snow tires. Paint the walls of the nursery. All before the baby arrived. As the list progressed, it became less a sequence of tasks than a wish-list. Catch up on reading. Meet up with friends. Sort out the garage. By the time she’d entered her third trimester, the list had become a bit anxious, given how few entries had been completed, and crossed-off. Sign up for swim lessons. Talk to her father. Travel. As she approached labour, the list had taken on an abstract quality. Breathe more. Walk along the canal. Notice the moon. As our first-born began to crown, she happened to glance up through the hospital window and there was the moon, full and round and constant.

Published on October 10, 2016 05:31

October 9, 2016

Drunken Boat blog "spotlight" series #6: Renée Sarojini Saklikar

The sixth in my monthly "spotlight" series over at the Drunken Boat blog, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online: Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar. The first five in the series feature

Ottawa poet Jason Christie

,

Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough

,

Ottawa poet Amanda Earl

,

American poet Elizabeth Robinson

and

American poet Jennifer Kronovet

. A new post is scheduled for the first Monday of every month.

The sixth in my monthly "spotlight" series over at the Drunken Boat blog, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online: Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar. The first five in the series feature

Ottawa poet Jason Christie

,

Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough

,

Ottawa poet Amanda Earl

,

American poet Elizabeth Robinson

and

American poet Jennifer Kronovet

. A new post is scheduled for the first Monday of every month.

Published on October 09, 2016 05:31

October 8, 2016

Ali Power, A Poem for Record Keepers

(33)

You want a location.

But you really mean a telescope.

I hand you the champagne from no occasion.

Should I keep going?

In certain rooms we can only look ahead.

Looking ahead is fun.

When you’re delusional.

New York poet and editor Ali Power’s first full-length poetry collection is

A Poem for Record Keepers

(Argos Books, 2016), a sequence of forty-nine numbered poems cut into seven sections. Composed of seemingly disconnected lines and phrases, the poems begin to accumulate after a while, and form a series of shapes, especially through the way sections appear to have been grouped, citing connections in tone, subject or phrasing. As Stacy Szymaszek writes on the back cover, this collection emerges from a “[…] poet who maintains a history of one’s activities.” There’s a fine tradition in such a consideration, from the “I did this, I did that” poems of New York School poet Frank O’Hara, the conversational observations of Toronto’s David W. McFadden, or even the life-long expansive journal-poems of the late Vancouver poet Gerry Gilbert (as well as Szymaszek herself, of course). What intrigues about A Poem for Record Keepers is in the short-form note-taking form that the poems appear to be composed in, allowing the connections between activities and poems to occur almost naturally, providing a more subtle series of threads throughout to hold the poems together as a single unit of composition. What appears somewhat scattered and random over the first few poems begins to cohere and shape in quite lovely ways. Her notes move from history to personal observation to completely mundane observations of daily activity and pop culture, and cohere into a portrait of the narrator in all her contradictory and complex ways.

New York poet and editor Ali Power’s first full-length poetry collection is

A Poem for Record Keepers

(Argos Books, 2016), a sequence of forty-nine numbered poems cut into seven sections. Composed of seemingly disconnected lines and phrases, the poems begin to accumulate after a while, and form a series of shapes, especially through the way sections appear to have been grouped, citing connections in tone, subject or phrasing. As Stacy Szymaszek writes on the back cover, this collection emerges from a “[…] poet who maintains a history of one’s activities.” There’s a fine tradition in such a consideration, from the “I did this, I did that” poems of New York School poet Frank O’Hara, the conversational observations of Toronto’s David W. McFadden, or even the life-long expansive journal-poems of the late Vancouver poet Gerry Gilbert (as well as Szymaszek herself, of course). What intrigues about A Poem for Record Keepers is in the short-form note-taking form that the poems appear to be composed in, allowing the connections between activities and poems to occur almost naturally, providing a more subtle series of threads throughout to hold the poems together as a single unit of composition. What appears somewhat scattered and random over the first few poems begins to cohere and shape in quite lovely ways. Her notes move from history to personal observation to completely mundane observations of daily activity and pop culture, and cohere into a portrait of the narrator in all her contradictory and complex ways.(8)

There is GPS.

There is Florida

There is pinecone.

There is trampoline.

There is olive oil.

There is getting to know you.

There is never getting to know all about you.

Published on October 08, 2016 05:31

October 7, 2016

Touch the Donkey supplement: new interviews with Quartermain, Earl, Kennard, Rhodes and Saklikar

Anticipating the release next week of the eleventh issue of Touch the Donkey (a small poetry journal), why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the tenth issue: Meredith Quartermain, Amanda Earl, Luke Kennard, Shane Rhodes and Renée Sarojini Saklikar.

Anticipating the release next week of the eleventh issue of Touch the Donkey (a small poetry journal), why not check out the interviews that have appeared over the past few weeks with contributors to the tenth issue: Meredith Quartermain, Amanda Earl, Luke Kennard, Shane Rhodes and Renée Sarojini Saklikar.Interviews with contributors to the first nine issues, as well, remain online, including: Sarah Cook, François Turcot, Gregory Betts, Eric Schmaltz, Paul Zits, Laura Sims, Stephen Collis, Mary Kasimor, Billy Mavreas, damian lopes, Pete Smith, Sonnet L’Abbé, Katie L. Price, a rawlings, Suzanne Zelazo, Helen Hajnoczky, Kathryn MacLeod, Shannon Maguire, Sarah Mangold, Amish Trivedi, Lola Lemire Tostevin, Aaron Tucker, Kayla Czaga, Jason Christie, Jennifer Kronovet, Jordan Abel, Deborah Poe, Edward Smallfield, ryan fitzpatrick, Elizabeth Robinson, nathan dueck, Paige Taggart, Christine McNair, Stan Rogal, Jessica Smith, Nikki Sheppy, Kirsten Kaschock, Lise Downe, Lisa Jarnot, Chris Turnbull, Gary Barwin, Susan Briante, derek beaulieu, Megan Kaminski, Roland Prevost, Emily Ursuliak, j/j hastain, Catherine Wagner, Susanne Dyckman, Susan Holbrook, Julie Carr, David Peter Clark, Pearl Pirie, Eric Baus, Pattie McCarthy, Camille Martin and Gil McElroy.

The forthcoming eleventh issue features new writing by: Buck Downs, lary timewell, Ryan Murphy, Kemeny Babineau, Oana Avasilichioaei, Norma Cole, Sandra Ridley, Lea Graham and kevin mcpherson eckhoff.

And of course, copies of the first ten issues are still very much available. Why not subscribe?

We even have our own Facebook group. It’s remarkably easy.

Published on October 07, 2016 05:31

October 6, 2016

On beauty

I was sleeping. I was asleep. In a dream at the edge of consciousness, I was time-travelling with my wife, attempting to show her what I was like when I younger. I wished to inform my younger self: it will get better. Is that all I wanted? It will get better. It did. The tricky part of our travel was in attempting to speak solo to my younger self, without attracting the attention of parents, classmates or teachers. From a distance, I attempted to catch the eye of my pre-teen self on the public school playground, from the edges of brush. Did I find myself? What did I say? I woke before the narrative completed. I have not thought of that playground for a very long time. The method in which we travelled was never revealed. I would like to know how the story ended.

I was sleeping. I was asleep. In a dream at the edge of consciousness, I was time-travelling with my wife, attempting to show her what I was like when I younger. I wished to inform my younger self: it will get better. Is that all I wanted? It will get better. It did. The tricky part of our travel was in attempting to speak solo to my younger self, without attracting the attention of parents, classmates or teachers. From a distance, I attempted to catch the eye of my pre-teen self on the public school playground, from the edges of brush. Did I find myself? What did I say? I woke before the narrative completed. I have not thought of that playground for a very long time. The method in which we travelled was never revealed. I would like to know how the story ended.

Published on October 06, 2016 05:31

October 5, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Angela Hume

Angela Hume lives in Oakland. She is the author of the poetry chapbooks

Melos

(Projective Industries, 2015),

The Middle

(Omnidawn, 2013) and

Second Story of Your Body

(Portable Press at Yo-Yo Labs, 2011). Her first full-length book of poetry is

Middle Time

(Omnidawn, 2016). You can learn more about Angela at http://angelamhume.tumblr.com/.

Angela Hume lives in Oakland. She is the author of the poetry chapbooks

Melos

(Projective Industries, 2015),

The Middle

(Omnidawn, 2013) and

Second Story of Your Body

(Portable Press at Yo-Yo Labs, 2011). Her first full-length book of poetry is

Middle Time

(Omnidawn, 2016). You can learn more about Angela at http://angelamhume.tumblr.com/.1 - How did your first chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?Brenda Iijima’s Portable Press @ Yo-Yo Labs published my first chapbook, Second Story of Your Body (2011). I wrote to Brenda out of the blue because I knew she had published Evelyn Reilly, whose work I loved. At the time I didn’t know Brenda at all. It was quite bold of me. I remember the night the chapbooks arrived in the mail. Brenda creates original artwork for her covers and surprises her authors with them. Seeing the physical books for the first time was magical. I opened the box to find gorgeous, mysterious book objects that were mine and not mine at once. It was one of the best gifts I’d ever received.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?I actually came to fiction first. Before I could write, I would dictate stories to my mother and then illustrate the pages of my “books.” Lines of verse didn’t come until puberty, when the world stopped making narrative sense to me. I didn’t understand my feelings and desires—my depressive episodes, my feeling of being absolutely alone, my painful attachments to women. I needed a form much more tormented. It was then that I started writing verse.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?My process is a slow one. I write in fragments. I assemble them into series. I revise unrelentingly, for as long as possible, even after work has been published. I live alongside my poems.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?For me poetry often begins with an image and a feeling, often in the natural world. I’m a hopeless Romantic. Poetry also often begins with a constellation of concepts and/or questions, usually informed by both my reading and current life experience. Recently my relationship with someone I loved very much fell apart. So lately I’ve been writing through feelings of loss, confusion, and grief. I’ve been thinking a lot about happiness, i.e., having what you desire, and disappointment, i.e., frustration or non-fulfillment of desire. Sarah Ahmed’s book The Promise of Happiness, which confronts heterocentric ideologies of “happiness,” is giving me a lot to think and write about.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?Readings can feel like acts of self-flagellation—standing up in front of a crowd, looking around and noticing who did or didn’t show up, forcing feeling to confess itself to itself as performance. Readings can leave me with feelings of self-doubt, unlikability, and overexposure. For people with social anxiety, they’re like diving into an ice-cold lake on an already unseasonably cool day. They hurt. They wake you up. They make you feel alive in the only body you have.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?I’ve been doing a lot of work at the intersection of queer theory and environmental philosophy and activism. I talk about it in this interview at Weird Sister and in this one at The Conversant. I’ve also been reading up on intersectionality theory, which comes out of 1980s black feminism and has been important to some of the poets whom I admire most. Intersectionality looks at how ideas about and politics of race, gender, sexuality, and class interact with each other and, consequently, privilege some people while multiply burdening others. It articulates how interactions between these ideas and politics create structural inequalities. So for example, if you are a queer woman of color, you may experience homophobia, sexism, and racism. But what often goes unacknowledged is how homophobia, sexism, and racism together produce an experience of oppression that is much more complicated than just the sum of the three. This is what Kimberlé Crenshaw first named the intersectional experience. (See her article “Demarginalizing the Intersection.”)

Intersectionality continues to be developed as an approach, and has a lot to offer radical political theories being developed by feminists, queer and critical race theorists, and environmental justice advocates. The insights of intersectionality are helping me think in my critical writing about the problem of the unequal distribution of environmental risk among women, LGBTQ people, and people of color.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?Writers can play any role they like. Writers are just people who do things in the world, and one of those things happens to be writing. I think that writers should aspire to be the things that I think all people should strive to be: passionate friends, lovers, activists, feminists, students, teachers, environmental stewards.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?Working with my editor at Omnidawn Publishing, Gillian Hamel, is a dream. She’s an extremely perceptive, sensitive reader.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?You can’t make someone want you, let alone love you.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?I write both poetry and literary criticism. The reading and writing I do around both are often in direct conversation. I don’t think it’s always true that being a critic and a theorist makes you a better poet. In fact it’s often not the case. But for me, developing as a reader of poetry and theory has been really important to my growth as a poet.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I get up, make coffee, eat cereal, and do a little writing—notes, journaling, e-mails, sometimes literary criticism, sometimes poetry. I do my best work in the late morning and early afternoon.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?Rivers, forests, oceans.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Summer air through the metal mesh of a screen in Middle America.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?All of the above! I love music by girls and queers with guitars, old art, and up-to-the-minute science news. Other “forms” that influence my work: sex, civil disobedience, interspecies encounters, cooking/eating, travel.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Here’s my chance to give shout-outs to some of my brilliant friends! I’ve been co-editing a cluster of articles on the topic of “queering ecopoetics” with the poet-scholar Samia Rahimtoola, who is very smart and savvy about environmental politics. Three wonderful writers, Laura Woltag, Jasmine Kitses, and Lily Brown, inspire me with their creative work and also have rescued me with their insight and intelligence, especially of late. As I’ve said elsewhere, Brenda Hillman is my sister-mother-mentor; the poet’s wisdom she offers me helps me achieve a greater sense of myself as both a poet and a human.

Writings perpetually important to both work and life? Some are Antigone and Electra by Sophocles. The poems of Emily Dickinson. The essays of Audre Lorde.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?So many things! Fortunately, I’m young, so I have time. I’d like to live in the country. Farm. Live in Barcelona, Berlin, New York City, and/or Oaxaca. Travel through Africa and Asia. Run a marathon in 3:40. Do a triathlon. Adopt a pup. Start painting again. Write a novel. Start a school, or a small press, or an EJ nonprofit. Maybe raise a kid. Teleport. Time travel. Grow very old and wise. Die and be reincarnated as a blue whale.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?I haven’t ruled out going back to school to study environmental science or policy and planning.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?I’ve simply been doing it for as long as I can remember, with absolute abandon.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?I’ve been reading a handful of good books recently: Annie Proulx’s Barkskins, Summer Brennan’s The Oyster War, Ruth Ozeki’s My Year of Meats, Hölderlin’s Hyperion. I’ve also been reading Angela Willey’s critical work on “biopossibility” and what she calls “queer feminist materialist science studies.” I thought the film The Lobster was great.

20 - What are you currently working on?Recently in Point Reyes, I participated in a residency as an NEA fellow through the Mesa Refuge and the Point Reyes National Seashore Association (PRNSA) themed “Climate Change at the Western Edge.” It was transformative. I stayed and worked next to the Giacomini Wetland Restoration Project, an area on the south side of Tomales Bay that was diked in the 1940s to create pastureland. In 2007 PRNSA and the National Park Service removed the levees in order to allow tides and fresh water to flow naturally and turn the area back into a tidal marsh. This is an important restoration project for number of reasons. One is that wetlands serve as a natural buffer against flooding. So wetland restoration is one way we can help build resiliency into our coastlines as we look ahead to climate-related sea level rises.

Most of the monitoring reports on Giacomini Wetlands say habitats and species are evolving toward conditions in natural tidal marshes. That said, researchers warn that we can’t necessarily expect a linear model of change. Instead, restoration may follow a nonlinear trajectory with interruptions and “thresholds” along the way. So I started reading about what restoration ecologists call “threshold dynamics,” in which restoration is understood to be a highly contingent, nonlinear process, as opposed to a continuous, progressive one.

Thinking about ecology restoration in this way means adjusting the structure of our expectation and being open to factors that we cannot control. I find myself asking: what kind of environmental ethos, or environmental love, even, does this new way of thinking entail? A less comfortable and comforting love for sure—a less ends-oriented one. And so the poem I’ve been working on is a little bit about the particular case of the Giacomini Wetlands and restoration science, but also our current situation under the conditions of global climate change and all of the complex human emotions that we experience as a result—feelings of anticipation that our hopes will be satisfied, disappointment when we don’t get what we want, and grief about the loss of oikos, the Greek word from which “ecology” comes, meaning family and household.

In particular, I’ve been trying to write about what queer experiences of oikos—what for queers are often frustrated or thwarted experiences of family and home—can teach us about how to better recognize and love what we might think of as our increasingly non-normative natures and ecologies.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 05, 2016 05:31

October 4, 2016

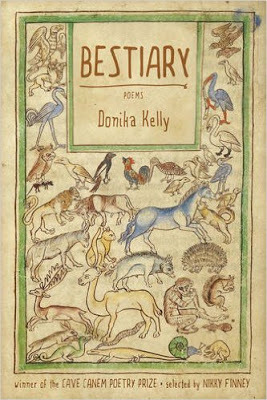

Donika Kelly, Bestiary

Bestiary is a first book of poems by an all Black girl who teaches us nothing is all black, or all female, or all male, or all belonging to humans, or all tidy. Bestiaries come out of an old tradition, but the beasts that push us to write our modern migration stories are found everywhere we dare deeply look. A hybrid of longing and lust is chronicled and mapped out here. What has been made contains a compass of new measuring. An inch is now a foot swinging at the father’s head.

[…]

The official public record tells us there are hundreds of years of unreliable others imagining and appropriating the desires of Black girls, eschewing their hopes and dreams as poets and people, their birth-marked stories, their personal migrations. For the other record, let me say, those reports have never had anything to do with Black girls and whales, Black girls and riots, Black girls and minotaurs, centaurs, satyrs, mermaids, werewolves, or Black girls “being a thing that breaks before it bends.” Black girls have always and often been the whispered-about and the strangely labeled. Not enough Black girls, whose own personal stories could turn you to stone with just a whisper, their up-the-side-of-the-mountain migrations rarely published or allowed to be told. But here is one that I have pulled from the great pile into the light so we might add it to the small truth pile of others. In Bestiary, no bending will be allowed. Rotate. (Nikky Finney, “Introduction”)

Northern California poet and scholar Donika Kelly’s first trade poetry collection is Bestiary (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2016), winner of the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, as selected by Nikky Finney. The poems in Kelly’s Bestiary are incredibly precise, tight without feeling constrained, with a looseness that almost defies such a density and precision. As she writes in the opening of “Love Poem: Pegasus”: “Foaled, fully grown, from my mothers’ neck / her severed head, the silenced snakes. Call this // freedom.” A quick Google search provides that a “bestiary” is, precisely, “a descriptive or anecdotal treatise on various real or mythical kinds of animals, especially a medieval work with a moralizing tone.” Kelly’s Bestiary, on the other hand, uses her list of beasts (including a number of mythical creatures) to explore more human subjects, from the intimacy of the narrator to the larger scope of humanity, carving out short essay-poems on singing, love, grief, solitude, loneliness and travel. At times, it feels as though she utilizes the camouflage of the animal to discuss deeply human concerns, while other poems might provide the animalistic as distraction, counterpoint, or comparison. As she writes to open the poem “Love Poem: Chimera”: “I thought myself lion and serpent. Thought / myself body enough for two, for we. / Found comfort in never being lonely.” These are poems about being, living and witnessing the world from a human place so deeply felt, and deeply familiar, as she writes to close the poem “Arkansas Love Song”: “This is not about my mother. / Another failure. / It is about nothing else.”

Northern California poet and scholar Donika Kelly’s first trade poetry collection is Bestiary (Minneapolis MN: Graywolf Press, 2016), winner of the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, as selected by Nikky Finney. The poems in Kelly’s Bestiary are incredibly precise, tight without feeling constrained, with a looseness that almost defies such a density and precision. As she writes in the opening of “Love Poem: Pegasus”: “Foaled, fully grown, from my mothers’ neck / her severed head, the silenced snakes. Call this // freedom.” A quick Google search provides that a “bestiary” is, precisely, “a descriptive or anecdotal treatise on various real or mythical kinds of animals, especially a medieval work with a moralizing tone.” Kelly’s Bestiary, on the other hand, uses her list of beasts (including a number of mythical creatures) to explore more human subjects, from the intimacy of the narrator to the larger scope of humanity, carving out short essay-poems on singing, love, grief, solitude, loneliness and travel. At times, it feels as though she utilizes the camouflage of the animal to discuss deeply human concerns, while other poems might provide the animalistic as distraction, counterpoint, or comparison. As she writes to open the poem “Love Poem: Chimera”: “I thought myself lion and serpent. Thought / myself body enough for two, for we. / Found comfort in never being lonely.” These are poems about being, living and witnessing the world from a human place so deeply felt, and deeply familiar, as she writes to close the poem “Arkansas Love Song”: “This is not about my mother. / Another failure. / It is about nothing else.”Whale

Know, first, that she does not remainbehind the baleen forever.

Know, too, that the whale is unawareof the woman drowning on its tongue.

And knowing this, recall the keening,the slow build of sound in the body;

that we were afraid and pressed our fearlow in our breast, held it alongside our breath;

that the tenor of our grief matched,so nearly, the tenor of our hysteria;

how finally there was no whaleor breath or sound or woman;

how, finally, there was only the body,rising through the water toward the sun.

Published on October 04, 2016 05:31

October 3, 2016

the ottawa small press fair, autumn 2016 edition: November 26

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:the ottawa

small press

book fair

autumn 2016 / 22nd anniversary edition

will be held on Saturday, November 26, 2016 in room 203 of the Jack Purcell Community Centre (on Elgin, at 320 Jack Purcell Lane).

“once upon a time, way way back in October 1994, rob mclennan and James Spyker invented a two-day event called the ottawa small press book fair, and held the first one at the National Archives of Canada...” Spyker moved to Toronto soon after our original event, but the fair continues, thanks in part to the help of generous volunteers, various writers and publishers, and the public for coming out to participate with alla their love and their dollars.

General info:

the ottawa small press book fair

noon to 5pm (opens at 11:00 for exhibitors)

admission free to the public.

$20 for exhibitors, full tables

$10 for half-tables

(payable to rob mclennan, c/o 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9; paypal options also available

Note: for the sake of increased demand, we are now offering half tables.

To be included in the exhibitor catalog: please include name of press, address, email, web address, contact person, type of publications, list of publications (with price), if submissions are being considered and any other pertinent info, including upcoming ottawa-area events (if any). Be sure to send by November 15th if you would like to appear in the exhibitor catalogue.

And don’t forget the pre-fair reading usually held the night before, at The Carleton Tavern! (readers tba)

BE AWARE: given that the spring 2013 was the first to reach capacity (forcing me to say no to at least half a dozen exhibitors), the fair can’t (unfortunately) fit everyone who wishes to participate. The fair is roughly first-come, first-served, although preference will be given to small publishers over self-published authors (being a “small press fair,” after all).

The fair usually contains exhibitors with poetry books, novels, cookbooks, posters, t-shirts, graphic novels, comic books, magazines, scraps of paper, gum-ball machines with poems, 2x4s with text, etc, including regular appearances by publishers including above/ground press, AngelHousePress, Bywords.ca , Chaudiere Books, Room 302 Books, Textualis Press, Thee Hellbox Press, Arc Poetry Magazine , Canthius , The Ottawa Arts Review , BuschekBooks, The Grunge Papers, Apt. 9, Desert Pets Press, In/Words magazine & press, Ottawa Press Gang, 40-Watt Spotlight, Puddles of Sky Press, Invisible Publishing, shreeking violet press, Touch the Donkey , Phafours Press, etc etc etc.

The ottawa small press fair is held twice a year, and was founded in 1994 by rob mclennan and James Spyker. Organized/hosted since by rob mclennan thru span-o.

Come on by and see some of the best of the small press from Ottawa and beyond!

Free things can be mailed for fair distribution to the same address. Unfortunately, we are unable to sell things for publishers who aren’t able to make the event.

Also: please let me know if you are able/willing to poster, move tables or distribute fliers for the event. The more people we all tell, the better the fair!

Contact: rob mclennan at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com for questions, or to sign up for a table

Published on October 03, 2016 05:31

October 2, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Ben Ladouceur

Ben Ladouceur

is a writer living in Ottawa. His first collection of poems, Otter (Coach House Books), was selected as a best book of 2015 by the National Post, nominated for a 2016 Lambda Literary Award, and awarded the 2016 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for best debut poetry collection in Canada. Ben is also the prose editor for

Arc Poetry Magazine

.

Ben Ladouceur

is a writer living in Ottawa. His first collection of poems, Otter (Coach House Books), was selected as a best book of 2015 by the National Post, nominated for a 2016 Lambda Literary Award, and awarded the 2016 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for best debut poetry collection in Canada. Ben is also the prose editor for

Arc Poetry Magazine

.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook, Three Knit Hats, which I wrote when I was 18, was such a lovely little totem of my extremely important passion. I gave copies to EVERYONE. My roommate's stepmom took twenty copies and gave them to her grade-eight students. A musician found a copy in a student lounge and turned a few of the poems into songs. Little cool things like that happened. It made me a very happy and proud and unembarrassed poet. I still think it's a pretty good collection, better than a lot of the chapbooks I wrote after it. (http://www3.carleton.ca/inwords/threeknithats.html)

Three Knit Hats is all jovial and emotive and overshare-y. Then I wrote more chapbooks, all trying new things -- going darker, or more descriptive, or more research-based, or more ecopoetic, or higher-concept. But it's funny to compare my most recent work to that first chapbook, because I really seem to have come full-circle. The most vulnerable, emotionally-specific poems I've published are probably (a) the first poems I wrote for TKH and (b) the last poems I wrote for my book Otter.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I've always written all three, just poetry the most.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

They come from copious notes, though less and less copious since I'm getting better at spotting false starts. Some come quick, some get revisited and refined for years.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

The unit of composition is about the size of a chapbook for me. I've written about ten chapbooks and I sort of think of Otter as a three big fat chapbooks that go well together and intermingle a little.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love doing readings. It's a big part of the writing process. It's how I learn that the poem I thought was solemn is actually funny, the clever one is boring, the erotic one is terrifying.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I try to tell the truth. By this, I mean that I try to relate the truth to people. But in equal measure, I also mean that I try to tell the truth apart from the things that aren't the truth. Probably all of my really good poems from the past few years come out of that effort.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I do think that poetry has the ability to instigate change in the world in a small way. Most poems don't but some do. Poetry is not a good way to transmit facts to people, for instance, but it is better-suited than most other media to transmit empathy. I really do think this. Really good poetry has helped me understand the lives and situations of other people -- refugees, old ladies, WWI soldiers, Mesopotamians -- in some sub-logical way I'd be hard-pressed to explain outside of the medium. Because they were never explained to me, these sensitivities, these things! They were sent in poems.

I don't think that it's always the intention of the poet to help people understand something. The poet just writes with whatever intention -- working out emotions, having fun with words, being heard, being found impressive. But if the poem is really good, there is a chance that it will change, if not the minds of its readers, then I don't know, their neural connections, their inner djinns, their bodily humors. There is a change, and it is for the better. Again, the poem has to be good.

So, I'm being reductive here, but: by reading poems by people who aren't a lot like me, I develop empathy and perspective. Conversely, by reading poems by people who are a lot like me, I come to feel less alone. Those are both big deals. Anyone arguing that poetry is entirely useless is reading the wrong poems, or can't read poetry for shit.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

An editor is important, but so is a trusted friend or writer's circle member. I suppose these people are editors too.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Do not get hooked on anger. Let shit go.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to film/web scripts)? What do you see as the appeal?

Not very easy, the movement between. Poetry is always what feels most natural, I always come back to it. With the film project Other Men , I felt like a poet who happened to have written a film script.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My routine, or even the degree to which I have a routine, is always changing. Right now I use the Notes app on my phone a lot, I like it because it just looks like I'm texting. I also use Voice Memos, or I email myself. Then after a while I sit down and look through my phone and notebook and inbox and see what's good, and what's going on.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I spend time with animals. I watch dumb TV. I throw my brain away. It's like a street cat, it comes back.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Dogs.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Yep yep yep. There is an artist I admire a lot. Last year I dreamt I bought her biography, so then I went and bought it, and I also got a book of her work. And for a good six-or-eight-month period, I'd look through the art book, and push my brain through the sieve of this artist's body of work, and then write poems, or edit poems, or try to. And I found that I was operating in a new way, with new criteria in mind. It made me feel better at describing the world.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Often, the important writers are the nearby ones, the ones I am able not only to read, but also talk to. If you're only reading big names, and that's the only scale of achievement you're exposing yourself to, you can get paralyzed. Reading local is a good way to hear stories you wouldn't otherwise here, and to study works of literature the mechanics of which you can get your head around.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Iceland, Cuba, a boat across the sea.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

In elementary school I was a huge class clown, and I was like, I will be a comedian. But then in high school I got gloomy and "a big laugh" stopped being my endgame in conversations and creative works. I put whatever wit I had to new use, writing poems and stories that were sometimes trying to be funny, but sometimes trying to be serious, angry, important, absurd, sexy, depressing, or some such combo. I do secretly think that, if my genes were all different and I wasn't gay and I never had to come out, I might have pursued comedy instead of poetry, might never have had that formative fuck-the-world phase during which I adamantly rejected my status as class clown. I'm really intrigued that there are quite a few household-name lesbian comics but no immensely popular gay male comics. My working thesis is that a lot of the gay class clowns perhaps did what I did upon puberty, grew to mind the laughs, went dark, went a new way.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It felt best.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Born With Teeth by Kate Mulgrew.

Film: Les Innocentes .

20 - What are you currently working on?

Sonnets and stories.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 02, 2016 05:31