Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 328

October 31, 2016

my Patreon patron-only blog : Alberta, and The Litter I See Project

Since building myself a

Patreon author page

, I've also been posting to a password-protected patron-only blog. I thought it might be worth reprinting the occasional post here, for the sake of general interest. Perhaps it might be worth tossing a ducat or two towards?

Here's a post from May 25, 2016, on the composition of a short story since posted here :

Here's a post from May 25, 2016, on the composition of a short story since posted here :

I recently composed a short story for the sake of a website I recently discovered, The Litter I See Project. I was curious at the idea of a project that invited short prose (or poetry, I have discovered) responding to a photograph of litter; it reminded me of an anthology I picked up a couple of moths ago, Significant Objects: 100 Extraordinary Stories About Ordinary Things (Fantagraphic Books, 2012). Instead of writing from litter, the anthology composed pieces from found and/or thrift store items.

I spent the entirety of my writing day this past Monday carving and crafting a very short story that accidentally sets in the space somewhere between my novel missing persons (The Mercury Press, 2009) and the short story, “Interruptions,” from my current manuscript-in-progress, “On Beauty.” I’d originally composed “Interruptions” at the prompting of Amanda Earl, who had wondered what might have become of the main character of my novel, so I wrote the teenaged “Alberta” some fifteen (or more) years later in short fiction. Now the manuscript has three stories that include and surround her (and another, in-progress, that attempts to further the story of her mother) at different points in her life, years beyond the events of my second novella.

I’m very pleased with this piece; it feels, in a certain way, like a “pivot point” for Alberta. Where the things that exist before this brief scene are not the things that exist beyond it. Sometimes the most significant changes are incremental, mundane and incredibly small.

I wasn’t, also, planning on making Alberta a smoker at any point, but that’s where the photograph took me. The only way it made sense.

ArchaeologyCut to her Saturday afternoon sequence of duMaurier extra lights amid the half-capacity shopping mall parking lot. As usual, Alberta arrives half an hour early, aware that her pre-teen will be fifteen minutes tardy, reveling in her new wealth of shopping detritus and gossip. Until her daughter appears, this is the single stretch of time that Alberta allows herself to breathe; the only moment she isn’t mid-task, or rushing between points or appointments. The only time, too, she allows herself to stoop to such youthful folly: a pack of cigarettes secreted beneath the driver’s seat, set alongside an increasing guilt. Weekly, for nearly an hour, she sits silent on the hood of their Ford Taurus and waits. She inhales. She follows the lacunae of parking lot seagulls, each one paintbrush smooth, floating across blue summer backdrop. On this particular afternoon she ponders rock climbing, hospital waiting rooms and swimming pools. She ponders her lost prairie, and the anonymity of suburban parking lots. She thinks back to the summer she watched a neighbour succumb to throat cancer, and now, as her husband emerges from chemotherapy, stoic and withered and weather-worn. She exhales, attempting to expel all of her fears and concerns along with the four thousand chemicals that make up cigarette smoke: nicotine, tar and carbon monoxide. In the soft August heat, Alberta treats asphalt as midden, newly littered with spent filters. Material remains. If everything were to end now, she wonders, if she were to disappear, might they ever find me. The small assemblage of abandoned butts the only evidence she’d been there at all.

Published on October 31, 2016 05:31

October 30, 2016

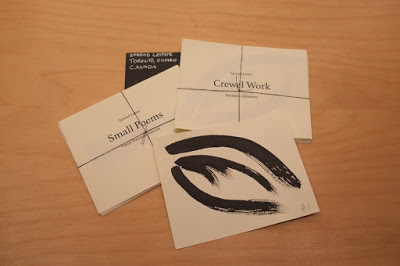

Joel W. Vaughan reviews my Four Stories (Apostrophe Press, 2016) in Broken Pencil

Joel W. Vaughan was good enough to review my Four Stories (Apostrophe Press, 2016) in

Broken Pencil

.

You can see the review here

. I have only a couple copies left, so if anyone is interested, shoot me an email at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com (although I've been thinking about reprinting/reissuing it). As he writes:

Joel W. Vaughan was good enough to review my Four Stories (Apostrophe Press, 2016) in

Broken Pencil

.

You can see the review here

. I have only a couple copies left, so if anyone is interested, shoot me an email at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com (although I've been thinking about reprinting/reissuing it). As he writes:Printed specifically for the University of Alberta’s Writer-in- Residence 40th Anniversary celebration, mclennan’s humble chapbook is as characteristically poignant as it is short-lived. This is no disparagement: right down to its bright yellow fly-leaves and lone, centered saddle- stitch staple, Four Stories is nifty—well worth its asking price.

Mclennan here, presents four previously published pieces, each four to five pages in length. His narrative voice rings familiar through all four, whether told autobiographically or in the third person, allowing his punchy visualizations to take the forefront both in personal observation (viz. “Reading my late afternoon newspapers at the pub, I see the sweetest looking young woman in a floral print dress stroll past bay window. She is summertime, blissful. In her left hand, fresh broccoli.” or an omniscient digression (viz. “She has been wanting to replenish their supply of preserves. Applied correctly, wax seals freshness in. / Cellar shelves by the cistern. Fresh cobwebs and field mice.” Mclennan’s loose piling of prose into stanzas suspends expectations, here, and makes a contemporary narrator feel natural throughout the timeless setting he sets out to build, word by word.

None of these four stories can be connected by time-line or geography, though thematically they express a preoccupation with Time, Absence, and Change: grand notions for the likes of a 19- page chapbook, but Mclennan does not disappoint. “Four Stories” is understated in its construction, and demands multiple read-throughs.

Published on October 30, 2016 05:31

October 29, 2016

Elisa Gabbert, L’Heure Bleue or The Judy Poems

When we argue about war,

I say I’m a pacifistand he looks for a loophole.

He brings up Hitler, genocide—these noble causes.

The problem I haveis distinguishing between atrocities:the genocide on one hand

and on the otheratomic bombs (their eyeballs melted),torture, women and children

raped and murderedfor the greater good.It’s like the difference between

a billion and a trillion—I believe they are differentbut can’t conceive of it.

The moral imperativejustifies the amoral,the technically lesser atrocity.

I think citizens don’t have to thinklike countries.

Denver, Colorado poet Elisa Gabbert’s third poetry collection, after The French Exit (Birds, LLC, 2010) and The Soft Unstable (Black Ocean, 2013), is L’Heure Bleue or The Judy Poems (Black Ocean, 2016), a collection, as the back cover informs, that “goes inside the mind of Judy, one of three characters in Wallace Shawn’s The Designated Mourner, a play about the dissolution of a marriage in the midst of political revolution.” In the introduction to the collection, poet, musician and multimedia artist Aaron Angello explains the process of how a conversation he had with Gabbert and her partner, the novelist John Cotter, turned into the a series of informal performances, and therefore, an ongoing study, of Shawn’s play, which then prompted Gabbert to explore the play further through poetry:

Throughout our rehearsal process, Elisa (who played her part brilliantly, in spite of the fact that she constantly reminded us she was “not an actor”) often voiced a frustration with the way her character, Judy, was written. The character, she felt, lacked a depth that the male characters had. Within the text of the play, Judy seemed relatively underdeveloped, shallow. I think, like any good actor, Elisa began exploring the mind and history of the character in a much more nuanced way. She had been living with Judy for a year and had been imagining her unwritten life; she had been imagining Judy’s feelings toward her father and toward her husband with a level of complexity that the play does not. It made her performance as sophisticated as any I’ve seen by a “professional” actor.

However, Elisa is a poet. It stands to reason, then, that she would begin thinking through Judy in the form of poetry. A short time after we stopped performing The Designated Mourner, Elisa started to write what would become L’Heure Bleue, or The Judy Poems. This is how it happened, in her words:

All I know is that once I was sitting in the audience at a poetry reading, which is one of the places that I often get ideas for poems… and I suddenly had the first couple of lines from the book come to me. They’re still the first lines of the book. And I wrote them down, and I was like, Oh—I should write in Judy’s voice.

Composed with an opening poem, “I’m not in love with Jack.,” before shifting into two numbered sections of short lyrics, the poems of Gabbert’s L’Heure Bleue or The Judy Poems explore the details of “Judy’s” character, backstory and situation, from pieces such as “Some days I can’t escape the feeling,” “When we argue about war,” “Nostalgia is the only cure” and “I’m happiest when I live simply,.” The most striking of these poems explore the moments between the moments, revealing much while saying little, such as the poem “At the poetry reading.,” as “Judy” catches a stranger’s eye, writing: “There are times when desire seems / to transfer. He communicates desire; / I am infected by desire. /// It’s the worst kind of desire— / too thin a film / between desire and reality.”

Composed with an opening poem, “I’m not in love with Jack.,” before shifting into two numbered sections of short lyrics, the poems of Gabbert’s L’Heure Bleue or The Judy Poems explore the details of “Judy’s” character, backstory and situation, from pieces such as “Some days I can’t escape the feeling,” “When we argue about war,” “Nostalgia is the only cure” and “I’m happiest when I live simply,.” The most striking of these poems explore the moments between the moments, revealing much while saying little, such as the poem “At the poetry reading.,” as “Judy” catches a stranger’s eye, writing: “There are times when desire seems / to transfer. He communicates desire; / I am infected by desire. /// It’s the worst kind of desire— / too thin a film / between desire and reality.”The idea of composing a collection of poems around a fictional character, with the purpose of expanding upon that character, is an intriguing one, reminiscent of Canadian poets Dennis Cooley and Lorna Crozier who both, separately, worked to flesh out the story of Sinclair Ross’ “Mrs. Bentley” (she was never given a first name) from his classic novel As For Me and My House (1941); Cooley, through his poetry collection the bentleys (Edmonton AB: University of Alberta Press, 2006), and Crozier, through A Saving Grace: The Collected Poems of Mrs. Bentley (Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 1996). So often, it seems, these reclamation projects emerge from classic texts that underwrite female characters, and have the potential to reveal intriguing elements of their source materials in new ways, that straight literary criticism couldn’t do nearly as well. Without knowing the source text that Gabbert works from, the full effect of what she adds and reveals might not be known, but not necessarily essential; enough to know that she was composed in two dimensions, and Gabbert has allowed her, finally, character, heart and flesh.

Jack is jealous

Of our scientist friend.He comes over for dinner

And eats a bowl of cereal.Cereal is a local maximum,He says, trying to impress me.

Jack can see it’s working.He says the scientist is my type:Tall and an asshole.

He’s right, I say, You’re right,But the scientist is sweetBeneath his ego.

He doesn’t care about looksSo I can be alluringWithout embarrassment.

The scientist: There are now more deathsFrom suicide than car accidents.You can’t harvest those bodies for organs.

Jack says, Ah! Progress!,lights a cigarette.

Published on October 29, 2016 05:31

October 28, 2016

Ploughshares : an interview with Stuart Ross

I'm a monthly blogger over at the Ploughshares blog! And my fourth post is now up: an interview with Cobourg, Ontario poet, editor, fiction writer and small press publisher Stuart Ross, author of the new poetry collection

A Sparrow Came Down Resplendent

(Hamilton ON: Wolsak and Wynn, 2016).

You can read my interview with Stuart Ross here

. My interview with

Toronto novelist Ken Sparling

, author of the new novel

This poem is a house

(Coach House Books, 2016),

is still online here

. My second post, an interview with award-winning

Kingston writer Diane Schoemperlen

, author of the new memoir

This Is Not My Life: A Memoir of Love, Prison, and Other Complications

(HarperCollins, 2016),

is still online here

; and my first post, an interview with award-winning Toronto poet Soraya Peerbaye, author of

Tell: poems for a girlhood

(Pedlar Press, 2015),

is still online here

.

I'm a monthly blogger over at the Ploughshares blog! And my fourth post is now up: an interview with Cobourg, Ontario poet, editor, fiction writer and small press publisher Stuart Ross, author of the new poetry collection

A Sparrow Came Down Resplendent

(Hamilton ON: Wolsak and Wynn, 2016).

You can read my interview with Stuart Ross here

. My interview with

Toronto novelist Ken Sparling

, author of the new novel

This poem is a house

(Coach House Books, 2016),

is still online here

. My second post, an interview with award-winning

Kingston writer Diane Schoemperlen

, author of the new memoir

This Is Not My Life: A Memoir of Love, Prison, and Other Complications

(HarperCollins, 2016),

is still online here

; and my first post, an interview with award-winning Toronto poet Soraya Peerbaye, author of

Tell: poems for a girlhood

(Pedlar Press, 2015),

is still online here

.

Published on October 28, 2016 05:31

October 27, 2016

Profile for Open Book: How to keep a small chapbook press alive for twenty-three years (a primer,

My short piece, "How to keep a small chapbook press alive for twenty-three years (a primer,"

is now online at Open Book

.

And, have you thought of subscribing?

My short piece, "How to keep a small chapbook press alive for twenty-three years (a primer,"

is now online at Open Book

.

And, have you thought of subscribing?

Published on October 27, 2016 05:31

October 26, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Elisa Gabbert

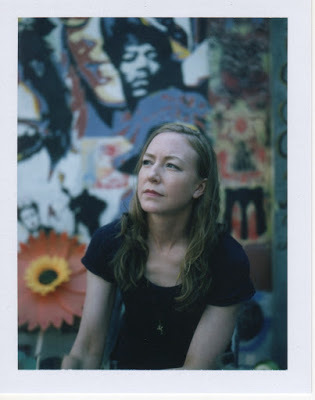

Elisa Gabbert [photo credit: Adalena Kavanagh] is the author of

L'Heure Bleue, or the Judy Poems

, The Self Unstable and The French Exit. Her poems and essays have appeared recently in Catapult, Diagram, Guernica, Harvard Review, Jubilat, Real Life, Threepenny Review, and The Smart Set. Her advice column for writers, “The Blunt Instrument,” appears on Electric Literature. Follow her on Twitter at @egabbert.

Elisa Gabbert [photo credit: Adalena Kavanagh] is the author of

L'Heure Bleue, or the Judy Poems

, The Self Unstable and The French Exit. Her poems and essays have appeared recently in Catapult, Diagram, Guernica, Harvard Review, Jubilat, Real Life, Threepenny Review, and The Smart Set. Her advice column for writers, “The Blunt Instrument,” appears on Electric Literature. Follow her on Twitter at @egabbert. 6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?I like poetry that feels close to philosophy, in that it uses language primarily to construct and engage with ideas and the act of thinking as opposed to, say, images or narrative. But I don’t think I’m trying to answer questions. The thinking is an end in itself.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?It depends on what kind of writer you are. The role of the critic is to demonstrate good thinking. But the poet? I don’t know that the poet has any particular role in culture. I think art exists to create meaning, but it could be any kind of meaning. It doesn’t have to be “relevant,” or even lasting.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?I find prose much easier to write than poetry. It feels almost self-generating. It’s expansive, digressive, whereas poetry requires distillation. I can only write poetry in a certain mood, a certain mindset. Sometimes I go years without writing it.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?I have no real writing routine. I write when I can and when I want to, which is not every day. Usually late afternoon, when I’m done with my day job, or on weekends.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?I don’t have a problem with gaps in my writing. Not writing is part of writing. If you’re writing all the time, how do you have anything to write about? In fact, knowing that I’m eventually going to write about something, thinking about it and taking notes, but delaying the actual writing, is a great pleasure for me and seems to make the writing better.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?The smell of rain in the desert. I grew up in El Paso and was so sad when I found that rain doesn’t smell that good anywhere else. It’s not just basic petrichor – I think it comes from the creosote.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?Definitely science, because it’s so idea-dense. Going to museums, too, but it’s almost more the act of museuming than the art per se. Also parks, concerts, bars, trains … anywhere you see lots of strangers. And I like specialized vocabulary, any subculture that has its own lexicon. Chess terms, sailing terms. I like to write down names of paintings.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Rather than name specific writers I’ll just say novels. I don’t write fiction but novels are my favorite thing to read. I’ve read hundreds of times more novels than books of poetry. I wrote a little about why I love them so much here.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Go to Greece. And Egypt. Also, space! I would love to go to space. I can do without skydiving though.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?I already do have another occupation, but if I wasn’t doing that either, I’d like to be a casting director.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film? A Heart So White by Javier Marías and Badlands .

20 - What are you currently working on?I’m writing lots of essays and trying to figure out how to make them into a book.

12or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 26, 2016 05:31

October 25, 2016

Stacy Szymaszek, Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals

you ateall thecuredmeat

__

Rachel’s catlicks myknuckles

never a parodyof care i.e.

when thereis groundeverywhere

sleeps inown beds (“austerity measures”)

New York poet Stacy Szymaszek’s fourth full-length poetry title is Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals (Albany NY: Fence Books, 2016), a collection built from five extended poem sequences of short lyrics composed as sketched out notes and fragments: “austerity measures,” “late spring journal [2012],” “summer journal [2012],” “5 days 4 nights” and “journal of ugly sites.” Her journal/ notebook poems favour quick thoughts, overheard conversation, observations, description and complaints, and the occasional list, all set up as an accumulation of collage-pieces reminiscent of the work of the late Vancouver poet Gerry Gilbert, as well as various “day book” works produced by Robert Creeley, Gil McElroy and others. There is such an incredible immediacy to the quick notes in this collection, one that manages an intimacy while, as she says in her 2013 “12 or 20 questions” interview, dispenses with persona:

My recent work has dispensed with persona. The longer I live in NYC, the more autobiographical it gets. One idea I have about this is that I had always wanted to live here but I was convinced that I didn’t have what it took, so in my mind this was a city of especially savvy people, a city of heroes—so being here I’ve become heroic, or the persona is now the hero named Stacy. The book I just completed is called Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals and takes up the idea of poetic journalism in different forms. The centerpiece is “Journal of Ugly Sites” which is a year-long journal I kept which documents, among other things, the life, illness and death of a Beagle that my partner and I rescued.

One could say that Szymaszek’s Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals exists as an exploration of the private and the public selves, writing on and around daily elements of internal and external being, from the meditative and the sublime to stretches of grieving and frustration to the mundane, routine and even magical, as she writes as part of “austerity measures”: “cut self / slack day // org. better / be sea- / worthy // five years / before / the mast [.]” Through such quick notes seemingly, and deceptively, jotted down into these accumulated narratives, they begin to provide intriguing portraits of this semi-fictional “Stacy,” in these, as she calls them, forms of “poetic journalism.” How different is this, one might wonder, to the “I did this, I did that” poetry of New York School poet Frank O’Hara? Both poets moving their art through their days in similar ways (his first drafts were also written relatively quickly during lunch breaks), although Szymaszek’s poems read more natural, somehow, which could easily be as simple as the difference between her journal-poems and his poems composed more traditionally as “poems.”

One could say that Szymaszek’s Journal of Ugly Sites & Other Journals exists as an exploration of the private and the public selves, writing on and around daily elements of internal and external being, from the meditative and the sublime to stretches of grieving and frustration to the mundane, routine and even magical, as she writes as part of “austerity measures”: “cut self / slack day // org. better / be sea- / worthy // five years / before / the mast [.]” Through such quick notes seemingly, and deceptively, jotted down into these accumulated narratives, they begin to provide intriguing portraits of this semi-fictional “Stacy,” in these, as she calls them, forms of “poetic journalism.” How different is this, one might wonder, to the “I did this, I did that” poetry of New York School poet Frank O’Hara? Both poets moving their art through their days in similar ways (his first drafts were also written relatively quickly during lunch breaks), although Szymaszek’s poems read more natural, somehow, which could easily be as simple as the difference between her journal-poems and his poems composed more traditionally as “poems.”What is interesting, also, is in how Szymaszek shifts the format slightly between each section, as the first section is dateless, but with the note that it was composed “during the months that followed the death of my dog Isabel on July 8, 2011,” the second and third sections include a scattering of dates within, and the final section is composed more as a straightforward (in comparison) poetic journal, with dates opening each section. As the “3.30.13 – 4.19.13” section of “journal of ugly sites” ends:

East Village: breathing into a paper bag before checking email any phone ringing increasing heart rate // photograph revealing how tired I am appearing on all the hot poetry sites with Warhol’s “Gold Marilyn Monroe” sure rub my ugliness in my face // publishing my shit list as a list poem? “Better to keep two chronicles?” (Harry Mathews) // when the poet said thank you for inviting me most people knew he hadn’t been invited so much as he wore me down // “do you make a livable wage? // Arlo as bearer of bad news today announcing “a bomb just went off”

if burnout is disavowed grief will I come back to life if I publicly admit how bereft I am?

An extension of this project (and its structures) has already been seen in her short chapbook JOURNAL STARTED IN AUGUST (Projective Industries, 2015), making me curious to see just how far she might further her exploration into the poetic journal. Might there be further volumes?

therapist lets me takenotes in session nowthat she understandsit’s not distancing

jot down“stoic”

*

in 6 days I will be a 43 yr. oldlacking emotional outlets

a protégé

the wasp incidentglory of sufferingburden of an EpiPenin your purse

get a holster (“summer journal [2012]”)

Published on October 25, 2016 05:31

October 24, 2016

Queen Mob's Teahouse : my interview with Claire Freeman-Fawcett on Spread Letter

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the sixteenth interview is now online:

Epistolary device: my interview with Claire Freeman-Fawcett on Spread Letter

. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Ann Tweedy conducted by Mary Kasimor, an interview with Katherine Osborne, conducted by Niina Pollari, an interview with Catch Business, conducted by Jon-Michael Frank, a conversation between Vanesa Pacheco and T.A. Noonan, "On Translation and Erasure," existing as an extension of Jessica Smith's The Women in Visual Poetry: The Bechdel Test, produced via Essay Press, Five questions for Sara Uribe and John Pluecker about Antígona González by David Buuck (translated by John Pluecker),"overflow: poetry, performance, technology, ancestry": kaie kellough in correspondence with Eric Schmaltz, and Mary Kasimor's interview with George Farrah, Brad Casey interviewed byEmilie Lafleur, and David Buuck interviews John Chávez about Angels of the Americlypse: An Anthology of New Latin@ Writing.

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the sixteenth interview is now online:

Epistolary device: my interview with Claire Freeman-Fawcett on Spread Letter

. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Ann Tweedy conducted by Mary Kasimor, an interview with Katherine Osborne, conducted by Niina Pollari, an interview with Catch Business, conducted by Jon-Michael Frank, a conversation between Vanesa Pacheco and T.A. Noonan, "On Translation and Erasure," existing as an extension of Jessica Smith's The Women in Visual Poetry: The Bechdel Test, produced via Essay Press, Five questions for Sara Uribe and John Pluecker about Antígona González by David Buuck (translated by John Pluecker),"overflow: poetry, performance, technology, ancestry": kaie kellough in correspondence with Eric Schmaltz, and Mary Kasimor's interview with George Farrah, Brad Casey interviewed byEmilie Lafleur, and David Buuck interviews John Chávez about Angels of the Americlypse: An Anthology of New Latin@ Writing.Further interviews I've conducted myself over at Queen Mob's Teahouse include: Stephanie Bolster on Three Bloody Words, Claire Farley on Canthius, Dale Smith on Slow Poetry in America, Allison Green, Meredith Quartermain, Andy Weaver, N.W Lea and Rachel Loden.

If you are interested in sending a pitch for an interview my way, check out my "about submissions" write-up at Queen Mob's; you can contact me via rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com

Published on October 24, 2016 05:31

October 23, 2016

On beauty

Before he was born, we took classes. Multiple classes. We watched videos, practiced breathing and back-massage, spoke of bathtubs and yoga balls, folded diapers in groups and practiced CPR on baby dolls. Some things can never be truly understood until you experience them. In the end, her labour thirty-seven hours from beginning to end. Thirty-seven hours. The midwife compared it to running five marathons. She was exhausted. I was exhausted. Stunned as our newborn pulled himself to the breast. Baby skin to skin as I quietly wept, and our new trio drifted from anxiety to relief.

Before he was born, we took classes. Multiple classes. We watched videos, practiced breathing and back-massage, spoke of bathtubs and yoga balls, folded diapers in groups and practiced CPR on baby dolls. Some things can never be truly understood until you experience them. In the end, her labour thirty-seven hours from beginning to end. Thirty-seven hours. The midwife compared it to running five marathons. She was exhausted. I was exhausted. Stunned as our newborn pulled himself to the breast. Baby skin to skin as I quietly wept, and our new trio drifted from anxiety to relief.

Published on October 23, 2016 05:31

October 22, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Zach Savich

Zach Savich

[photo credit: Lisa Wells] was born in Michigan in 1982 and grew up in Olympia, Washington. He received degrees from the Universities of Washington, Iowa, and Massachusetts. His work has received the Iowa Poetry Prize, the Colorado Prize for Poetry, the Cleveland State University Poetry Center's Open Award, and other honors. His fifth collection of poetry,

The Orchard Green and Every Color

, was published by Omnidawn in 2016. He is also the author of

Diving Makes the Water Deep

, a memoir about cancer, teaching, and poetic friendship. He teaches in the BFA Program for Creative Writing at the University of the Arts, in Philadelphia, and co-edits Rescue Press's Open Prose Series.

Zach Savich

[photo credit: Lisa Wells] was born in Michigan in 1982 and grew up in Olympia, Washington. He received degrees from the Universities of Washington, Iowa, and Massachusetts. His work has received the Iowa Poetry Prize, the Colorado Prize for Poetry, the Cleveland State University Poetry Center's Open Award, and other honors. His fifth collection of poetry,

The Orchard Green and Every Color

, was published by Omnidawn in 2016. He is also the author of

Diving Makes the Water Deep

, a memoir about cancer, teaching, and poetic friendship. He teaches in the BFA Program for Creative Writing at the University of the Arts, in Philadelphia, and co-edits Rescue Press's Open Prose Series.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?My first book was published in 2009 by the University of Iowa Press. I’d been writing poetry seriously since 2001, submitting manuscripts since 2006. I got the call and was in a daze for a week. I remember driving fifteen hours to a job, totally blissed. Understand I was a person who had made a lot of decisions, some of which I wouldn’t advise, in order to try to write poems; I was probably too fixated on publishing a book as a kind of proof, a justification that the relationships I’d failed at, the leases I’d broken, the jobs I’d quit—all that led somewhere. Where did it lead? I met many people I’m glad to call friends. I got to leave those poems behind and write new ones.

The main difference now: it was useful for me to believe (and I probably still do) that a first book should show one’s learning, many types of poem tried. For over a decade, I tried to read and write as variously as I could. That was also a way of covering my ass, and matched ideas that were current at the time about hybridity, experiment. Now I don’t want more ideas about poetry, more fluency, more formal ability, more proof of accomplishment, but more time.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?I first wrote prose: heavy praise to small town public libraries and their fiction shelves. But my interests were poetic; the best story I ever wrote started, “For a dime, a yard sale book.” I walked around for weeks repeating that sentence, for the rhythm, its shuffle and stomp.

Then a teacher read some Hopkins and I stared at his mouth like it was the source, like how could we stomach language that was less. Then I realized that poetry might be an interest that let me stay interested in many things, and (in contrast with philosophy, which I thought I was interested in), allow types of unknowing, emotional and astonished reasoning, away from insufficiently conventional phrases and ideas, a way for language to find itself or us.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?Yes, it starts with making notes, as one does when reading—to be marginalia to many things. At some point the notes start to stick together, and at some point some of them stick together less than others, and I begin to revise: from collage to compost. The poems in my latest book, The Orchard Green and Every Color, are often composed of distinct statements with a semi-proverbial tinge. I think that style can slacken unproductively if it starts to seem merely notational, so I try to revise to convey/enhance a notational sense, of momentary perception, while also cutting a lot. Leading to kind of hyper-realism, but with a hush? The writings of George Oppen and Lisa Robertson helped me think about this.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?Yes, as mentioned above, it comes from notes. You walk and remark on things to a friend, or to a phrase. For books, I tend to have a title first, one that serves as a kind of tuning fork, and then I fit or adapt or construct material to preserve the tone and meaning that seem hovering in the phrase. I do think of many things in terms of books—friends are familiar with my advice to extend an essay, to try to make something into a book. That unit’s meaning means more than its status as literary artifact, clearly. Maybe I’m a person who loves reading books but “works” to write poems that let me look up from them, or feel like I have. That way of staring while turning a phrase around.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?Health has prevented me from giving or attending many readings in recent years. This has made me more aware of all the readings I attended or gave that could have been different—when I would have rather talked to a friend who was in the crowd, and didn’t get to, or when we all mostly wanted to have a party, or to say hello and then get back to a babysitter, or when I was too self-conscious about the reputation of the university I happened to be reading at or who was there or wishing I had already written the next poems that I was sure would be better. Or was blown away by the first poem and should have gone for a walk to think about it. I suppose I’ve always liked most reading aloud with friends—others’ work, more than my own—in kitchens and campgrounds, when it also feels fine to put down the poems at any time. I like hearing my students read. I like when a reading becomes—officially or not—more of a discussion. I remember where we went after the readings, more than anything I said. This one time at Al’s in Seattle, or on that roof in Lincoln, swearing I had once been a roofer.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?Can I say my theoretical concerns are life and death? I hesitate to say that I’ve been, say, “dancing around an overtly terminal state,” because I’d rather be wrong, and aren’t we all dying, and Keats alive is better than Shelley’s “Adonais,” all the sentiment of the imminently (eminently? immanently?) mortal scribbler. And I’m lucky, in a way, to be able to think about this state, with healthcare and friends and a supportive job and a house I like, with relative ability, relative time. But it drives my questions, which I suppose are more acute versions of ones that anyone has: how to be past certain things but not beyond Things; how to “appreciate moments” while not romanticizing diminished capacity, the frayed receptors that still slightly light from time to time, which once interwove, beamed, met others; the limits of language/ability/will/resolve; how little “understanding” or “wisdom” changes things; courage, folly, empathy; how to at once give in and insist. To be astonished each day (no choice but to be), by what can be lost or found again or lost again and how much.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?I think there’s value in the continual insistence on what literature is especially good at exploring, and which many aspects of culture tell us we should ignore: mixed emotions, experiences with multiple or unclear “meanings,” intuitions that don’t fit conventional narratives or phrases, absurdity, desire, transport, candor.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?I love it. And I find the dedication/friendship/intelligence of my editors to be one of the most heartening parts of my life—I don’t mean their commitment to my work, except as it’s part of a larger commitment. Rusty Morrison at Omnidawn spoke with me for hours about an early version of The Orchard Green and Every Color, helping me not just revise the manuscript (into something very different than she initially accepted) but understand where to go next with my writing. Carrie Olivia Adams and Janaka Stucky at Black Oceanhave at once supported the wildness of some poetry I felt unsure about and made it more precise; when I was in one period of bad health, Janaka offered to drive several hours and edit with me in person, an especially beautiful generosity that I think is indicative of the spirit of the press and of so many poets. The editors I mentioned are all poets whom I admire; it’s a gift, to have their eyes on time on my work, when I also hope they have time for their own.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?“This way is north, unless this is.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?I sometimes write reviews. I favor a critical style that is more journalistic than academic. I’m disappointed when I read critical prose, especially about poetry, that focuses on books I’ve read and discusses critics I’m familiar with in a style that conveys mostly (I can grumpily feel) the sociology of the academy, of types of discourse that gain authority by all they leave out or argue away—I’m eager to say that I feel equally grumpy about anti-academic postures. For a long time I felt like it was a responsibility to try to review new books of poetry—especially poetry that some people wish to consider “difficult” because it doesn’t tell a little story of little feelings in little words—in a clear style, with reference (maybe too much) to poets some readers might be familiar with. More recently I’ve felt that responsibility in other ways: I wrote a review of Keith Waldrop’s Selected Poems, for example, because I’ve loved his work for years, but I felt aware that the book wouldn’t get too many reviews, and maybe I could write one as someone who has read a bit both in the experimental lineages his work is often associated with and in some poetry from the mid-century that might at first glance seem separate from his. The appeal, I guess, is in how critical prose can make an appeal: to affirm that what we do in poetry matters, and can be discussed in terms that are comprehensible to interested readers who haven’t already signed on to the scene or downloaded this season’s favored jargon, while also advancing those thoughts through the types of flight and recklessness and intuition that poetry loves.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?Illness is redundant, a sorry excuse for an excuse, but it’s true: in recent years I organize my days and energy around small tasks. I cook elaborate things that take a long time. I respond to work emails and read student poems and papers. I hold and stare at stones and shells and bits of wood. I read newspapers and listen to news programs on the radio. I sometimes find some notes I have taken and sometimes get excited about what they start to suggest. I try to stay calm. I say this wishing I had more time to think or read or think or read better about this state, but it’s a part of it, that you can’t.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?I listen. I cook elaborate things that take a long time, I read newspapers, etc…

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?Tidal muck.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?I’m lucky to teach in an art school, where my colleagues and students work in many media, and my courses include ones on collaborative practice, so I’m frequently finding sustenance in other arts and in the conversations artists in other fields have about questions like these. In recent years I’ve been especially glad to work with composer Jacob Cooper on several projects; his work, which is wonderfully atmospheric and playful and surprising and precise, has helped me think about how contemporary poetry can offer comparable experiences. His recent album, Silver Threads , features collaborations with poets including me and Tarfia Faizullah and Dora Malech and others. It’s out from Nonesuch Records.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?I want to mention some books by friends whose work has run through mine, and my mind, for years, excellent books, the pleasure of feeling floored with respect for people you’ve known through many situations, a syllabus and seminar to be near: Andy Stallings ( To the Heart of the World ), Melissa Dickey ( Dragons ), David Bartone ( Practice on Mountains ), Hilary Plum ( Watchfires ). The poets I never tire of, who I can read when I’m sick of reading and poetry (that is: when I need poetry the most), include Oppen, Hopkins, Niedecker, Schuyler, Rosmarie Waldrop. I’ve spent a fair amount of time with Cervantes and Dante, think about them daily. I’ve come to love the late books of James Tate in recent months, think he really perfected some things in his last years.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Write one more book.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?This is what I’ve wanted.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?I grew up in a house with books, in a place that was removed from some things and had a lot of some other things, with parents who were very creative and would have liked to do more with the arts, and I always took language very seriously, as though it were real.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?Ivan Vladislavic’s Double Negative (novel; fans of Sebald will love it) and Portrait with Keys (nonfiction, of Johannesburg). Just read them. I haven’t felt like such a fan in a while.

20 - What are you currently working on?Brining a thing I mean to sear.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 22, 2016 05:31