Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 329

October 21, 2016

Kaia Sand, A Tale of Magicians who Puffed Up Money that Lost its Puff

the president probably talks to someone every daysometimes his lips are moving, but our volume’s too lowsometimes his voice is a tenth the volume of minesometimes his voice trembles inside my ten voicessometimes his ten words devalue the currencysometimes we promisesometimes someone looks into someone’s eyes for truthsometimes we think we see itin someone’s ten coughs, tuberculosis is passed from cot to cotsometimes ten walls separate me from two people making one decision (“The President Probably Talks”)

Portland, Oregon poet and activist Kaia Sand’s latest is

A Tale of Magicians who Puffed Up Money that Lost its Puff

(Kāne’ohe HI: Tinfish Press, 2016), a collection constructed as a kind of collage of formal considerations, from sequences built out of incredibly dense stand-alone lines, protest songs and more expansive theatrical scrips to shorter, more traditional lyrics, all of which work to explore a variety of political and social concerns, from oil spills, the lottery, American politics, the mortgage crisis and the abuses of the big banks, to poverty, nuclear stockpiling and looming environmental disasters. Sand’s poems document as much as they resist, working to reinforce the strength of the community against systematic abuses far too often built into the structures of those systems created to protect. “Where is anonymity within a public document—,” she writes, in the second poem of her “Air the Fire A Triptych.” In the third and final poem, she writes: “In the bright threat of attention / the surefire glare of recognition / you became a public person / mindful of those who live / downriver and downwind / from the malice of power [.]” The politics of her writing is clearly overt, sharing a social and political element of what the poem can accomplish alongside an increasing list of poets up and down the Pacific, from Stephen Collis, Christine Leclerc and Cecily Nicholson to Juliana Spahr and David Lau, among so many others. At the end of the collection, she includes extensive notes, her “Notes on the Lives of Some Poems Thus Far,” offering that “A poem might be read as though it has a ‘long biography,’ accruing meaning through shifting contexts, Peter Middletonsuggests in his book

Distant Reading

; I have taken this notion to heart as a writer with an interest in recasting poems. The following notes attend to the publication histories of the poems as well as performance, material, and social histories. In some cases, I include brief political contexts, with the hope that some poems might carry contexts forward, like burrs caught in fur. I document various iterations of these poems on my website: kaiasand.net”

Portland, Oregon poet and activist Kaia Sand’s latest is

A Tale of Magicians who Puffed Up Money that Lost its Puff

(Kāne’ohe HI: Tinfish Press, 2016), a collection constructed as a kind of collage of formal considerations, from sequences built out of incredibly dense stand-alone lines, protest songs and more expansive theatrical scrips to shorter, more traditional lyrics, all of which work to explore a variety of political and social concerns, from oil spills, the lottery, American politics, the mortgage crisis and the abuses of the big banks, to poverty, nuclear stockpiling and looming environmental disasters. Sand’s poems document as much as they resist, working to reinforce the strength of the community against systematic abuses far too often built into the structures of those systems created to protect. “Where is anonymity within a public document—,” she writes, in the second poem of her “Air the Fire A Triptych.” In the third and final poem, she writes: “In the bright threat of attention / the surefire glare of recognition / you became a public person / mindful of those who live / downriver and downwind / from the malice of power [.]” The politics of her writing is clearly overt, sharing a social and political element of what the poem can accomplish alongside an increasing list of poets up and down the Pacific, from Stephen Collis, Christine Leclerc and Cecily Nicholson to Juliana Spahr and David Lau, among so many others. At the end of the collection, she includes extensive notes, her “Notes on the Lives of Some Poems Thus Far,” offering that “A poem might be read as though it has a ‘long biography,’ accruing meaning through shifting contexts, Peter Middletonsuggests in his book

Distant Reading

; I have taken this notion to heart as a writer with an interest in recasting poems. The following notes attend to the publication histories of the poems as well as performance, material, and social histories. In some cases, I include brief political contexts, with the hope that some poems might carry contexts forward, like burrs caught in fur. I document various iterations of these poems on my website: kaiasand.net”“Beware the fury of the financier,” she writes, to open the final poem in the collection, “Beware the Fury,” “rote fury, puffy money, bankers who bank / on diverted attention. Divested / power.” In the five-poem “Deep Water Horizon Ledger,” for example, she writes of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on increasingly blackened pages, opening with the poem “At Least Five Gallons Per Second” to “At Least Twenty Gallons Per Second,” etcetera, writing that “In the time it takes me to say this, at least 160 gallons of oil will have gushed out / of the Deepwater Horizon site. / And now 200 / And now 240 / And now 280 / And now 320 gallons of oil [.]” Her notes explain further, writing that “During the months of May & June 2010, I performed this poem on a walk I led in North Portland as well as at a poetry reading in Director Park in downtown Portland, and it was published on PoMotion Poetry and Poets for Living Water. The poem served as breaking news, my up-to-the-minute (more or less) accounting of the oil spill. Pocket Notes (Fall 2012) published the notes I jotted toward the poem’s postscript.” What makes her collection so engaging is the way she plays with form even through such serious subject matter, and how she documents while also managing to uphold the immediacy, even urgency, of a series of events that have not simply unfolded, but continue to unfold. Hers is a series of documents on the constantly-changing world as it currently stands, right there on the precipice.

Magician taps wand against mortgage.

and who knew who owned what anymore.

And really, who knows who owns what anymore, now that the banks are trying to grab back those millions of houses. The banks have to grab them whole, not doors to some houses and shutters to others, but since that’s how they owned them, or sold them through those collatorized debt obligations, it’s all rather confusing. And now the paperwork is fluttering, fortune cookie flimsy, and some banks hired some people to sign names rapid-fire to papers foreclosing on the houses, without reading all the words and the phrases, and it’s all rather dodgy and shoddy and shammy.

Really, stay tuned to that story, which is still being written,

Published on October 21, 2016 05:31

October 20, 2016

12 or 20 (small press) questions with Peter Vanderberg on Ghostbird Press

Peter Vanderberg is the founding editor of Ghostbird Press. He served in the US Navy from 1999 – 2003 and received a MFA from CUNY Queens College. His work has appeared in several journals including

Mud Season Review

, CURA and LUMINA, and his chapbook

Crossing Pleasant Lake

has recently been published by Red Bird Press. He teaches at St. John’s Preparatory School and Hofstra University.

Peter Vanderberg is the founding editor of Ghostbird Press. He served in the US Navy from 1999 – 2003 and received a MFA from CUNY Queens College. His work has appeared in several journals including

Mud Season Review

, CURA and LUMINA, and his chapbook

Crossing Pleasant Lake

has recently been published by Red Bird Press. He teaches at St. John’s Preparatory School and Hofstra University.Ghostbird Press is a small chapbook press that publishes poetry, fiction, non-fiction, translation and cross-genre works, actively seeking new and underrepresented voices. Our books are each a collaboration of both writing and visual art. The words aren't illustrated, the images aren't explained. Word and image coexist to increase your chances of epiphany.

Please check out our books at www.ghostbirdpress.org . If you are a writer yourself, send us your work. With any luck, one day we will meet at a reading or launch party or backyard BBQ.

1 – When did Ghostbird Press first start? How have your original goals as a publisher shifted since you started, if at all? And what have you learned through the process?

Ghostbird Press began in 2011 after my grandfather's passing. Starting a small press was something I had thought of since attending the CUNY Chapbook Festival in 2006 while at CUNY Queens College for my MFA. I was so inspired by all the small publishers there, making things, often with their own hands, that would bring writing to life in the real, physical world. I loved writing, but I also loved the idea of making things, of doing the work of publishing. My grandfather had started his own business after World War II and his work ethic has always been a guide for me. After he died it just seemed like the time to get going with my own small venture.

The goals for the press haven't changed much. I have reigned in my expectations a bit as I continue to balance Family - Writing - Teaching - Publishing. But I still read submissions and work with authors that I love and publish 3 - 4 chapbooks a year. One change: we just put out our first comic book, so now that's happening.

2 – What first brought you to publishing?

Again, it was really the CUNY Chapbook Fest that made it seem possible for me to try publishing. The small press editors and publishers there exuded an energy and optimism that was infectious. I fell in love with the idea of engaging with literature on that very real and personal level, while also building the community that grows from a small press through events and of course books.

3 – What do you consider the role and responsibilities, if any, of small publishing?

I believe small presses are in a unique position to try new things regardless of market / industry norms. Of course we should be aware of the industry and its workings, but I love that I can sign an author that is totally unknown, who is writing very different, risky stuff, and I don't really worry about the profit margin. The questions is simply: do I believe in this work? I also think small presses, maybe all presses, have a responsibility to seek underrepresented voices and stories. For example, I'm actively seeking an American Indian writer. I want to read those poems, stories, perspectives. I don't see enough of that.

4 – What do you see your press doing that no one else is?

Ghostbird Press is committed to the visual arts as well as the literary. Each book we publish has an original cover and several internal images that are made by a single artist. My main artists are my two brothers James and Paul, I have a certain commitment to them, but I am open to others and we did produce a book by a writer whose wife did the cover and internal art (eco-logic of the word lamb, Roger Sedarat).

5 – What do you see as the most effective way to get new chapbooks out into the world?

To be honest I'm still trying to figure that out. I use social media, but I'm not really into Facebook. I do love twitter for some reason. My favorite way is through events. Each year we host a launch party for several authors. I love how that builds the community because folks come out for one author, but they meet the others as well. Going to readings and book fairs is great too, because again, you actually shake hands with people, hand them a book, converse about art and writing. There's nothing better for me.

6 – How involved an editor are you? Do you dig deep into line edits, or do you prefer more of a light touch?

I prefer not to touch the writer's work. At most, if I think something is amiss, I'll just ask why a certain decision was made and as long as there is intent there, I go with it. Working the internal art into the manuscript is a more involved process because I want the writer to be happy with their book so we discuss image choice and placement more in depth. I'm a writer as well as a publisher and every word and punctuation mark of my own work has a reason behind it. I'd hate to have my work accepted on condition so I don't do that to my authors either.

7 – How do your books and broadsides get distributed? What are your usual print runs?

We distribute through our website sales and some local book stores. Of course readings and events as well. We use print on demand services so I'll usually print out 50 initial copies for the author's copies and our own events, but the books do not go out of print.

8 – How many other people are involved with editing or production? Do you work with other editors, and if so, how effective do you find it? What are the benefits, drawbacks?

Nope. I'm the guy. Just me. Again, I work with the artist and author, but final decisions are made by me. I'm a despot.

9– How has being an editor/publisher changed the way you think about your own writing?

I can't say as it has changed my writing in any real way, but it has helped me to be more confident in submitting to journals and small presses. I have an inside perspective into how the publishing world works, so I feel less intimidated by other small presses. I' also less depressed by rejections - I don't take them personally anymore. It still disappoints me to be turned away by a press I admire and want to work with, but I know they are receiving many many submissions and that mine just isn't right at that moment. I hope those writers that I don't accept know that. I'm also less begrudging of submission fees. They are so essential to keeping a small press alive. I think of fees as my donation to a worthy cause.

10– How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?

10– How do you approach the idea of publishing your own writing? Some, such as Gary Geddes when he still ran Cormorant, refused such, yet various Coach House Press’ editors had titles during their tenures as editors for the press, including Victor Coleman and bpNichol. What do you think of the arguments for or against, or do you see the whole question as irrelevant?I have mixed feelings. The first book I put out was a collaboration between myself and my brother James and I treated it as a kind of experiment to see if I really wanted to try publishing. I loved making that book and am very proud of it, but I'm not sure I would put out my own work through Ghostbird again anytime soon. I very well might do so in the future though. I guess my feeling is that it's fine as long as it isn't the prime focus of the press.

11– How do you see Ghostbird Press evolving?

I have a dream of taking on a partner, but I have zero budget for that right now. I'd like to partner with another institution, maybe a museum or university. And some day I'd like to develop a reading series for our authors beyond the launch party.

12– What, as a publisher, are you most proud of accomplishing? What do you think people have overlooked about your publications? What is your biggest frustration?

I'm very proud of the writers we have published - their work is all brilliant. I love how the visual art converses with the written word. My biggest frustration right now is that I'm having a tough time getting our books reviewed. I'd like to see what they think.

13– Who were your early publishing models when starting out?

One of the first chapbook presses that I admired was Flying Guillotine Press. Their books are hand made genius. I've always admired H-NGM-N press. I think Nate Pritts is doing great work over there. And I love all the strange little publications that Greying Ghost puts out. I'm certainly in awe of larger literary presses: BOA editions, Alice James, Tupelo, Copper Canyon, but I love the little guys too, the ones that are making books solely for the love.

14– How does Ghostbird Press work to engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large? What journals or presses do you see Ghostbird Press in dialogue with? How important do you see those dialogues, those conversations?

We are still a young press, but I see us in dialogue with the local NYC chapbook scene. Specifically, there is a growing and vibrant literary movement in Queens which I'd love to be more engaged with. Queens keeps it real in so many ways and I see that in the writers groups and publications that come out of Queens. I'm a Queens College MFA alum too, so I'm always looking for ways to be a part of that amazing community.

On the other hand I do feel like there are presses and journals beyond NYC that I feel a kindred spirit with - Mud Season Review in Burlington VT is so cool, and H-NGM-N is, I believe, physically located in upstate NY. I admire many small presses but I'm not sure I would assume to be in conversation with them. Wouldn't they need to talk back for a conversation to unfold?

15– Do you hold regular or occasional readings or launches? How important do you see public readings and other events?

As mentioned, we host an annual book launch and that is my favorite way to engage with the public. I think public events are the best way for people to get to know us and to create real relationships with venues, writers and readers. I love the internets as much as the next guy, but I prefer to shake hands with people.

16– How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals?

16– How do you utilize the internet, if at all, to further your goals? Our website is our prime means of outreach - it's our storefront, though I'd love to have an actual storefront someday...add that to the dreams list above. The internet is really essential to all aspects of the press from receiving and replying to submissions, to editorial work, to the proof process and publishing...sales...outreach...it's all on the web. If they turn off that internet switch, I guess I'll put up a table and sign on my front lawn on nice days. That could actually be fun.

17– Do you take submissions? If so, what aren’t you looking for?

We are always open for submissions. We are not looking for bad poetry.

18– Tell me about three of your most recent titles, and why they’re special.

Resplendent Slug by Kimiko Hahn, is a collection of poems inspired by natural biology, particularly animals that glow. But Kimiko Hahn has such a talent for weaving the strange and very real world of science with the stranger and arguably more real worlds of being a woman, a mother and a lover. her work is full of loss and passion and the striking beauty that only she can communicate. The drawings that accompany these poems blur the lines between the real and the abstract and in so doing, illuminate the text.

Eco-Logic of the word lamb by Roger Sedarat is a translation / imitation of Virgil's Eclogues. Roger Sedarat does not attempt another verse translation here, rather, he offers his Eco-Logic: born of the Eclogues, but every bit as grounded in contemporary experience / culture as Virgil's text was over 2,000 years ago. Janette Afsharian's images are powerful and symbolic as tarot cards and their interplay with the text deepens the reader's experience.

For My Son, A Kind Of Prayer by Richard Jeffrey Newman takes for its inspiration the totality of fatherhood. All of the anguish, fear, strength, passion and vulnerability of being a husband and father are expressed here in such honest and beautiful ways. I gave this book to my own father for Father's Day last year, so it has my endorsement as publisher, father and son.

They are all so special I can't even count the ways - please get a copy for yourself and see what's so great about them!

12 or 20 (small press) questions;

Published on October 20, 2016 05:31

October 19, 2016

Melissa Dickey, Dragons

the toddler chews a pacifier as a jokehides his face as a joke

he does not yet reador understand the sadness of others

when you saw your old friend and she spoke so thicklyyou thought maybe her teeth were falling out

as her mother’s hadbut she was just hiding her braces

I’ve stopped smiling, she saidthe toys play samples

of Beethoven as if thathelps but he doesn’t care

he’ll dance to anythingfor now (“Notational Domestic”)

Western Massachusetts poet and trained birth doula Melissa Dickey’s second poetry title, after The Lily Will (Rescue Press, 2011), is Dragons (Rescue Press, 2016), a book focused on her immediate domestic, including the birth of her child and those first few weeks that turn into months that turn into years. Perhaps it is my own shift over the past few years, but I’m heartened to see that writing on the ‘domestic’ is being taken more seriously these days, by writers and readers both. Dickey’s poems exist in a long line of incredibly powerful work by poets (who are also mothers) composing on the miraculous, mundane and dark elements of household and children, such as Rachel Zucker (another poet also trained as a doula), Alice Notley, Hoa Nguyen, Bernadette Mayer, Pattie McCarthy and Julie Carr (there are also plenty of male poets writing similar works), as Dickey writes to open the first section, “Daybook”:

For the first two years I didn’t tell her that I loved her. As if saying made it a thing to be questioned, evaluated—to say nothing was better. (The day she was born, they put the needle in her spine.)

Or, further on, the entirety of the short poem “The Day,” that reads:

A mother, again.Newborn sleepy scent,jello limbs. Bloodin the trash Ihide. Strange interiormuscles mark me.

Wonderfully small and charming, Dickey’s poems articulate moments over longer, extended narratives, from the short lyric poem to the lyric fragment accumulating into sequences, and her sequences move delicately from moment to moment, point to point. Given her short, staccato lines, her use of the poetic “Daybook” (the title of one of her poem/sections) as well as attentiveness to the domestic, her work is reminiscent of the late American poet Robert Creeley, a poet who deeply articulated the small moments of the immediate over his entire career.. There is such a physicality to her poems; an immediacy and an intimacy and a precision that requires slowness, even a deep attention. Hers is an attentiveness to moments so often passed over, unspoken or otherwise unexplored, for what can’t help but be, at first, an incredibly powerful and foreign space:

Wonderfully small and charming, Dickey’s poems articulate moments over longer, extended narratives, from the short lyric poem to the lyric fragment accumulating into sequences, and her sequences move delicately from moment to moment, point to point. Given her short, staccato lines, her use of the poetic “Daybook” (the title of one of her poem/sections) as well as attentiveness to the domestic, her work is reminiscent of the late American poet Robert Creeley, a poet who deeply articulated the small moments of the immediate over his entire career.. There is such a physicality to her poems; an immediacy and an intimacy and a precision that requires slowness, even a deep attention. Hers is an attentiveness to moments so often passed over, unspoken or otherwise unexplored, for what can’t help but be, at first, an incredibly powerful and foreign space: Closed my skirt with a butterfly pin, hung shoes on the clothesline. Lemon tree. Mortar, brick. In the photo, a goat’s teats dangle, bell collar around the neck. Why does pregnancy look so pathetic. And this man, a tree the way he stands. Basil grown from dusty ground. The wall that seems to ripple, bulge. How much am I censored, how much predetermined. What kind of what is hanging, how. (“Daybook”)

Published on October 19, 2016 05:31

October 18, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jennifer Zilm

Jennifer Zilm

is the author of

Waiting Room

(BookThug, 2016) which was shortlisted for the Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry. She also wrote the chapbooks

October Notebook

(dancing girl press, 2015) and

The whole and broken yellows

(Frog Hollow Press, 2013). A second collection is forthcoming in 2018 from Guernica Editions. She lives in Vancouver where she works in libraries and social housing.

Jennifer Zilm

is the author of

Waiting Room

(BookThug, 2016) which was shortlisted for the Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry. She also wrote the chapbooks

October Notebook

(dancing girl press, 2015) and

The whole and broken yellows

(Frog Hollow Press, 2013). A second collection is forthcoming in 2018 from Guernica Editions. She lives in Vancouver where she works in libraries and social housing. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook was called The Whole and Broken Yellows and came out with Frog Hollow Press in late 2013. After it came out I did a flurry of readings; this felt like exposure therapy that really helped me with performance anxiety. So that really changed me. Waiting Room contains some of the same poems as that chapbook but the poems in common are arranged in such a way that I hope they can be understood in a different context. Knowing the book was going to come out, I didn't read any of the poems in the book from summer 2014 to the book's release this spring. I was afraid I would burn out on the poems. What has happened as I've begun to read them again is I have begun to see the different ways the book can be presented and accessed, this has allowed me to understand the poetry better. The book itself also had a strange ripple through my personal life.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?I started writing poetry when I was, yes it's true, a teenage girl. Right around the same time I started to play truth or dare. Lately, I have been thinking that these two things are related though I'm not sure exactly how other than that the truth is the dare and poetry to me seems the best means of expressing that.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?All of the above. I sometimes think poems come fully made but then I will look back at old notebooks and think "have I actually been writing this poem for years?" I had an experience where I wrote a sestina at the beginning of 2014 and it felt as though it was just channeled and I felt like a mystic poet. But then I went back and realized I'd actually been writing towards the poem for a really long time.

In terms of note taking, I have a couple of notebooks on the go at a time. I have one that is a general notebook and which is a "commonplace"-- quotes from books etc.

I wrote Waiting Room very quickly. The core of the book was written between January-June 2013, the longer erasure that is in the second section was written in the Fall of that year. I kept saying that the entire book was written in 2013, but I went back to my notebooks recently and realized that one of the poems was written in the Winter of 2014. So it’s interesting to watch the narratives one creates about how a book or a piece was written.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?I usually work on two projects. Waiting Room was definitely a project, and a book from the very beginning but it began with one poem (Spiritual Media) and then all of the project started to unfurl from that point and I began to sort of see how each poem I was writing would relate to the manuscript. However, at the same time I was working on other poems that seemed more "stand alone" and which I then sort of wove into a more disparate collection that I worked on over the summer of 2013 and then into 2014. That collection—which is tentatively called Ephemera and which is coming out with Guernica Editions in 2018—has poems written both before and after Waiting Room and organizing it was far more challenging. A lot more poems were cut and I changed the ordering a great deal. Eventually I made a map where I tried to see the direction the poems were making. I paid attention to nouns and keywords so I could articulate what the manuscript was "about". Then I had a very intuitive friend read over it and she sort of redrew the map for me.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?They have become a part. Much of Waiting Room was written at the time when I began to do public readings. It made me pay closer attention to sonics and to line breaks. In my first public reading I remember having this moment where I felt "oh this is another way of getting to know this poem". The idea that I would be reading a poem in front of people seems so terrifying that the only way I can really do it is by pretending that the world is ending. So since I've started doing it I feel as though I am living in a state of realized eschatology. Which is fun.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?I want to say something grandiose like "how should a person be?" but I can't think of anything or how can words take down late capitalism, but I can’t think of anything.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

It's good to have people who think about words a lot.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?I find it very helpful. Even the idea of having a reader in my head as I write helps me.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

My mentor Jen Currin, when I was beginning to write Waiting Room, told me I needed to "get messy."

I heard the poet Lissa Wolsak speak on a panel once and she said "I honor the process, even if it seems daft." That is a mantra.

Some other gems that have resonated: "It's not a good idea to apologize for things you're not really sorry for" (this is in Waiting Room). "Think of each line as a poem in itself."

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical/academic prose)? What do you see as the appeal?I worked for a long time on a dissertation about gender, angels and prayer in Second Temple Judaism. I found that the psychic space required for that type of work left little room for poetry. Often I found it hard to give the elevator speech about "what are your research interests" (asked by senior academics) or "what is your thesis about" (asked by people outside the discipline). I found that after I had decided not to finish the dissertation, I actually had about 100 pages of material I could work with. Two erasures in Waiting Room ("Dead Sea Scrolls" "Post-doctoral, fellowship: the Wedding Ceremony") were actually built from the dissertation and seem as though they are the answers to those two questions. So, I like to believe I am writing poetry even when I am not actually writing it, but anytime I am writing anything down.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I try to read/write first thing in the morning. If I have time at home, I will do it there. If not I will do it in transit. I am a great fan of writing in contained, trapped spaces. So the bus is really one of my favourite places to write.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?See above! I tend to get on a bus with a book and a notebook and some music.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Burning leaves.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?All of them. There are ekphrastic poems in my book about visual art and the cut and paste collage (art therapy style) really helps me with my writing process. And of course, probably would never have wanted to write poetry if I hadn’t heard Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Volume 2 when I was five years old being driven from Greater Vancouver to Northern B.C. and heard Dylan says “10,000 miles in mouth of graveyard.” So music is important. I am also inspired by documentaries (especially ones that have a collage like atmosphere) and the news. I watched the CNN Series “Crimes of the Century” and I felt like it was speaking to me.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?Where to begin? Much that has been written or translated by Anne Carson: Nox (which I used a lot in my chapbook October Notebook) and the Euripides translations Grief Lessons ; My Life by Lyn Hejinian; the original V.C. Andrews titles (Flowers in the Attic etc.) but only the editions which have the peep hole covers; bpNichol's Selected Organs; Maggie Nelson's Bluets; Proust’s In Search of Lost Time; parts of the Gospels (the healing of the blind man in Mark and John is referred to several times in Waiting Room; the Dead Sea Scrolls Thanksgiving Hymns; the Book of Genesis; Northrop Frye's The Bible and Literature; Jack Gilbert; Irving Layton (I read him when I was 14 and his syntax still stays with me); Jen Currin.16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?Learn Arabic.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?In my next life I'd like to be a gospel singer or an outlaw country singer/song writer.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?I'm uncertain. I suspect you hear things when you're very young and just fasten on to them. Someone said "Jennifer is very verbal" when I was a baby and it probably just stuck. Reading is one of the first skills one learns so if you’re good at it maybe it’s good to stick with it. 19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I read Maggie Nelson's Bluets at the exact moment when I needed to read it. The last great film was Adam Curtis’ Century of the Self.

20 - What are you currently working on?A manuscript that is sort of In Search of Lost Time but set in the housing projects of Surrey, B.C. (mixed poetry/prose), a book of poems called Charismatic Megafauna, Research Questions and Crimes of the Century. I’m also thinking about a project that is going to be poems based on the spoken introduction to various classic country songs on my iPod. I'm calling it Country and the first section will just be Johnny Cash's various intros to I Still Miss Someone.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 18, 2016 05:31

October 17, 2016

Queen Mob's Teahouse : David Buuck interviews John Chávez

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the fifteenth interview is now online: Against Normalization / Contra la Normalización: David Buuck interviews John Chávez [pictured] about Angels of the Americlypse: An Anthology of New Latin@ Writing. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Ann Tweedy conducted by Mary Kasimor, an interview with Katherine Osborne, conducted by Niina Pollari, an interview with Catch Business, conducted by Jon-Michael Frank, a conversation between Vanesa Pacheco and T.A. Noonan, "On Translation and Erasure," existing as an extension of Jessica Smith's The Women in Visual Poetry: The Bechdel Test, produced via Essay Press, Five questions for Sara Uribe and John Pluecker about Antígona González by David Buuck (translated by John Pluecker),"overflow: poetry, performance, technology, ancestry": kaie kellough in correspondence with Eric Schmaltz, and Mary Kasimor's interview with George Farrah, and Brad Casey interviewed byEmilie Lafleur.

As my tenure as interviews editor at Queen Mob's Teahouse continues, the fifteenth interview is now online: Against Normalization / Contra la Normalización: David Buuck interviews John Chávez [pictured] about Angels of the Americlypse: An Anthology of New Latin@ Writing. Other interviews from my tenure include: an interview with poet, curator and art critic Gil McElroy, conducted by Ottawa poet Roland Prevost, an interview with Toronto poet Jacqueline Valencia, conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Drew Shannon and Nathan Page, also conducted by Lyndsay Kirkham, an interview with Ann Tweedy conducted by Mary Kasimor, an interview with Katherine Osborne, conducted by Niina Pollari, an interview with Catch Business, conducted by Jon-Michael Frank, a conversation between Vanesa Pacheco and T.A. Noonan, "On Translation and Erasure," existing as an extension of Jessica Smith's The Women in Visual Poetry: The Bechdel Test, produced via Essay Press, Five questions for Sara Uribe and John Pluecker about Antígona González by David Buuck (translated by John Pluecker),"overflow: poetry, performance, technology, ancestry": kaie kellough in correspondence with Eric Schmaltz, and Mary Kasimor's interview with George Farrah, and Brad Casey interviewed byEmilie Lafleur.Further interviews I've conducted myself over at Queen Mob's Teahouse include: Stephanie Bolster on Three Bloody Words, Claire Farley on Canthius, Dale Smith on Slow Poetry in America, Allison Green, Meredith Quartermain, Andy Weaver, N.W Lea and Rachel Loden.

If you are interested in sending a pitch for an interview my way, check out my "about submissions" write-up at Queen Mob's; you can contact me via rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com

Published on October 17, 2016 05:31

October 16, 2016

Pearl Pirie on rob mclennan (twice!) : Brick Books' Celebration of Canadian Poets + mentorship via The League of Canadian Poets,

Kind thanks to Pearl Pirie, who did two deeply kind and generous write-ups about me recently. She did one on my work as part of the Brick Books Celebration of Canadian Poetry, and another on myself and mentorship (and her experiences through my poetry workshops) via The League of Canadian Poets blog. Holy thanks! Wow,

Kind thanks to Pearl Pirie, who did two deeply kind and generous write-ups about me recently. She did one on my work as part of the Brick Books Celebration of Canadian Poetry, and another on myself and mentorship (and her experiences through my poetry workshops) via The League of Canadian Poets blog. Holy thanks! Wow,

Published on October 16, 2016 05:31

October 15, 2016

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sanita Fejzic

Sanita Fejzic is an Ottawa-based writer whose novella,

Psychomachia

, appeared in September 2016 with Quattro Books. She is currently working on her first play, The Blissful State of Surrender.

Sanita Fejzic is an Ottawa-based writer whose novella,

Psychomachia

, appeared in September 2016 with Quattro Books. She is currently working on her first play, The Blissful State of Surrender. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different? My first chapbook, City in the Clouds, was published by In/Words Magazine & Press in August 2015, just before I came on as co-editor. It's too early to tell how it changed my life. I don't believe important moments can be understood as life-changing until we look at them in retrospect. We make narratives about our lives when we look back on important events, but when they happen in the moment or when they are about to happen, as for example, the upcoming launch of Psychomachia, we are faced with pure possibility. I have no doubt the launch of my first book will change everything, but in what way and how remains to be seen. The first chapbook, for example, opened the door for an opportunity to edit with In/Words. That opened countless other doors to connect with the literary community in Ottawa and make friends, to co-edit the themed issue of Refug(e)e with Lise Rochefort. It will be launched at the Ottawa International Writer's Festival in October, yet another opportunity that may change everything.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction? Poetry always precedes prose. I am of the opinion that good prose reads like prose poetry. All great writing, including drama and non-fiction, is sensitive to poetry. What do I mean by poetry? The love of words; the intense care that goes into every sentence; being sensitive to and seduced by poetic devices such as imagery, metaphor, assonance, alliteration, rhyme and repetition and so on. So to answer your question, it's not that I came to poetry first, but rather, I think poetry naturally comes before prose, or at least that's how it is for me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes? Writing is rewriting and I have never had a first draft that didn't require extensive editing. At first, that used to discourage me. Now, it's just part of the process and I accept it. Someday I hope to enjoy it. Psychomachia, for example, was written in a week. It was like being in a trance, I was processed by the story and the characters. I didn't sleep well for a few days after I had written it. Almost as if I was going through withdrawal from the high of writing with so much intensity and concentration. But that's not how I normally write; it's an exception to the rule. Usually, I write and write and write and then let it sit. I go back to it and realize that, as Anne Lamott says, it was a shitty first draft and then the real work begins. I have received funding from the OAC to finish a novel set in the Siege of Sarajevo which I have been working on for the last two years. It's nowhere close to being done. What I've come to understand about my process is that while I write quickly, I edit slowly.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning? I know from the beginning, generally, if I'm writing a piece of short fiction or a larger work, such as a novella or a novel. The forms don't behave in the same ways, so it's impossible for me to let a short story leak into a novella or a novella into a novel. A short story is usually leading to a single, decisive moment, with the focus on one character or perhaps a handful of characters that move around a single thread toward this moment. A novel is much more complex. There are many characters with sub-plots and the story has many threads. The novel allows for dead-ends, contours and detours as it leads the reader toward some resolution, be it climactic or not. A novella stands in between these two zones. Of course, I'm grossly oversimplifying, but generally speaking, I know what form I'm dealing with from the start because I know what the story demands.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings? For me, and as I will argue in my Master's thesis next year, writing is a technology for the care of the self (or, as the Greek called it, "epimeleia heautou"). Through writing, I am able to transform the relationship between my self with the self, as well as the self's relationship with others. The others, in the context of writing, are readers. This can be done in two ways, one of them is private, and the other is public, through readings. Not only do public readings create a space for the relationship between the self and others to take place, I believe readings are essential because they are the only spaces where this relationship is ephemeral and dynamic. It is never the same twice. There is an aura around them that cannot be replicated and that, to me, is valuable. It is magic.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are? I think writing, in the modern and post-modern contexts anyway, is concerned with the role of the writer (consider "Death of the Author" by Barthes) and the effects of language (semiotics). Writing is also concerned with power and knowledge, and for this reason, it is political. There are many Canadian writers, some of them local, such as Pearl Pirie, some not, such as Daphne Marlatt, who deconstruct language in critical, intelligent and sometimes humorous ways. I think poetry and experimental writing is well-suited to do that: to question and challenge the medium--words and language--itself. Though I am fascinated by this, my own writing is more interested in the role of the writer. I argue that writers are truth-tellers (specifically, writers must fulfill the criteria of "parrhesiastes," in the ancient Greek sense) and that writing, as an activity, is a technology for the "care of the self" as defined in an earlier question. I will express all of these ideas with more clarity in my Master's thesis, as well define a will of poetry, all in an effort to articulate the role of the writer in our ultra-modern context.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be? My Master's thesis, under the supervision of professor and philosopher Stuart Murray, is titled, "The Role of the Writer in the Ultra-Modern Context." I have, as Nabokov would say, "strong opinions" about the writer's role and the role of writing independent of the author. To have an opportunity to work with Stuart Murray, I have pushed back my work on theorizing Canadian novellas to later on, at the PhD level. I want to argue that writers are truth-tellers and that the process of writing is a technology for the care of the self. That writing, be it fiction or otherwise, such as works of philosophy, are a way for the self to transform its relationship with the self and with others.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)? It is absolutely essential. As a writer, I know I have blind spots. I know there are moments when I am on autopilot and the story is losing some of its momentum but I cannot see it without someone else pointing it out to me. As an editor, I can see how a few essential changes strengthen a piece and bring it to life and I know, from experience, that when you enter the process of editing with the focus on the story (not the writer or the editor), this collaboration always results in better quality, vivacity and flow for the text. For this reason, I would never self-publish. "Writing is a collaborative act," to quote Nadia Bozak, who was once my fiction teacher and is currently the Creative Writing Director at Carleton's English Department. I can't say it any better.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)? "Believe in yourself; I believe in you." My lovely partner, whose wisdom and love moves me to write and brings endless beauty and love into my life.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction to plays to journalism)? What do you see as the appeal? Poetry to fiction is easy; journalism is hard. Poetry and fiction are lovers. They are truth-tellers and speak from the heart, mind and gut. Everything is aligned and in harmony. Journalism, which is supposed to be the ultimate truth-telling, does not seem to understand, or refuses to admit, that the observer always changes the observed and vice-versa. It takes (f)acts and delivers them through the mind, impartially, seemingly objectively, and cuts itself off from the heart and the gut so that in the end it hypnotizes itself into a discourse that is sometimes insensitive and cold in its delivery. It is not for me, though I have done it and may even do it again.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin? This summer has been a complete write-off. I am desperately trying to establish a routine, some kind of discipline that does not depend on inspiration but it isn't working for me. A typical day, if we are talking of the last few months, looks like the myth of writer's block is dangerously close to reality.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration? That is the question. The problem is, even when I am inspired, and a breath of fresh air has pumped my lungs, it does not seem to affect my pen.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home? My partner's hair. The zest of fresh bed sheets. The olfactory sense is not one that reminds me of home as our home is fragrance-free and what we eat is always changing. It feels like home wherever my partner and my son are.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art? Life influences language, which creates narratives about our experiences and by extension, the books we write. Intertextuality is inevitable because we read and are moved by certain works but that has its limits. All that is required to write books, I think, is to be alive to our experiences, both internal and external. The more I think of it, the more I realize that writing a book is a journey inward, into our selves, rather than an external process. Nature, music, science, visual art, travel, gastronomy, relationships: they are all expressions, mirrors, of our selves. They cannot help but inform us and by consequence, the books we write.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work? Woolf, Nabovok, Kundera, Wilde, Tolstoy, Camus, Joyce, Neruda, Stevens: these are the ones I read over and over again. There are many others. Lately, I've been reading a lot of non-fiction. Right now, I'm reading Earthing: The most Important Health Discovery Ever? by Ober, Sinatra and Zucker, The Backpacker's Field Manual by Rick Curtis and The Presence Process by Michael Brown. The most essential experiences that inform my writing are the relationships I have had or currently cultivate with other human beings and, more and more so, with Mother Earth. These connections touch and move me and have the power to change who I am.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done? Experience a continuous state of present moment awareness. It would be nice, for example, if it's not too much to ask of the universe, to have a year where my mind is not concerned with the past or the future.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer? Either I would have been a chef with my own restaurant or I would have been an artist, preferably a sculptor. I have a deep need to express myself creatively, can you tell?

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else? I began to write when I was six years old and cannot recall why. I remember in Croatia, Geneva and Ottawa, teachers telling me, in Serbo-Croatian, French and then English, that my stories were well beyond my years and that I should be a writer. I didn't take them seriously and got a Commerce degree to impress my parents instead. Ironically, I ended up in communications, writing and editing full time until it became evident that I had to express myself artistically. I suppose those teachers saw something in me that I couldn't about myself at the time.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film? War and Peace by Tolstoy. It's great because, finally, there you have a text as long and as intense as the Bible, but a little bit more to my taste. Not that I've read the Bible back to back, but it sure felt like it in some points, after the second and third week of flipping through the world's thinnest pages and not being able to stop, so spellbound was I by Tolstoy's book. Plus: it is a miracle that I finished it, considering the many other obligations that I have and the investment in time the book requires. Last great film: Nymphomaniac by Lars von Trier. Lars von Trier disturbs me and, at the same time, captivates me. He makes me feel uncomfortable and sometimes outrages me (as in Antichrist) but I know, without a second of doubt, that what I am watching is brilliant. This is not just a movie, this is a work of provocation, of art, of extraordinary beauty even amid the violence and horror.

20 - What are you currently working on? I am collaborating with two Toronto-based theater directors and an editor on my first play, The Blissful State of Surrender. I am on my third rewrite, waiting for further edits. I'm also editing the prose component for the Refug(e)e themed issue of In/Words in collaboration with Lise Rochefort, who is editing the poetry. I am also translating from French to English a chapbook of poetry by award-winning Quebec poet, writer and translator Sylvie Nicolas.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

Published on October 15, 2016 05:31

October 14, 2016

Denise Newman, Future People

The Translator

Mistaking a coiled ropefor a snakelike mixing upanxious and eager,“I’m anxious to meet you,”revealing a hidden dreadclimbing the stairsto the esteemedpoet’s apartment. “It was all aboutgentleness” or “It was a matterof kindness”—?Face to face:snake, then rope,then ropeand its agent. “It was a questionof gentleness.”

Following her collections

Human Forest

(Apogee Press, 2000),

Wild Goods

(Apogee Press, 2008) and

The New Make Believe

(Sausalito CA: The Post-Apollo Press, 2010), California translator and poet Denise Newman’sfourth poetry title,

Future People

(Berkeley CA: Apogee Press, 2016), is a curious collection of lyrics exploring connections and disconnects, rewriting a logic out of fragments, distractions, digressions and deliberately shattered lyrics. “If I shut the door this fly hasn’t a chance” she writes, in the poem “The Father”: “and I can’t bear that.” Future People is constructed in five sections: three sections of short lyrics, and the second and fourth sections as extended lyric suites. Hers is a descriptive mode that works to unsettle, and then pushes to explore that confusion in detail, something she has in common with the work of Gigi Janchang, as Newman writes in her “Notes” at the end of the collection, the title section, the second, “is a collaboration with the artist Gigi Janchang, and is based on her series

Portraits 2084

. She created new faces by combining facial elements from people she photographed of different ages, genders, and nationalities. Each feature is from a different person.” As the corresponding poem writes:

Following her collections

Human Forest

(Apogee Press, 2000),

Wild Goods

(Apogee Press, 2008) and

The New Make Believe

(Sausalito CA: The Post-Apollo Press, 2010), California translator and poet Denise Newman’sfourth poetry title,

Future People

(Berkeley CA: Apogee Press, 2016), is a curious collection of lyrics exploring connections and disconnects, rewriting a logic out of fragments, distractions, digressions and deliberately shattered lyrics. “If I shut the door this fly hasn’t a chance” she writes, in the poem “The Father”: “and I can’t bear that.” Future People is constructed in five sections: three sections of short lyrics, and the second and fourth sections as extended lyric suites. Hers is a descriptive mode that works to unsettle, and then pushes to explore that confusion in detail, something she has in common with the work of Gigi Janchang, as Newman writes in her “Notes” at the end of the collection, the title section, the second, “is a collaboration with the artist Gigi Janchang, and is based on her series

Portraits 2084

. She created new faces by combining facial elements from people she photographed of different ages, genders, and nationalities. Each feature is from a different person.” As the corresponding poem writes:There are always plentywatching to serve as witness—“What what?”—trouble hearing through glasstrouble with senses-only reality—“Where’s-your-lab-work?”Let Lazarus explain. “You need to go to _______ for a blood test.”

“But all the blood is on the outside structure.”He hands him his record. “It’s empty.”

“In reality is your body—the folder—” L. says, “notthe scribbles therein-out.”“Out!” said the guard, and laughed so that he felloff his glass.

Published on October 14, 2016 05:31

October 13, 2016

above/ground press: 2017 subscriptions now available!

Twenty-three years! As we edge even closer to twenty-five (as well as above/ground press' 800th publication, due any day now!). Can you believe it? There's been a ton of activity over the past year around

above/ground press

, from the continuation of

Chaudiere Books

(the trade extension, one might say, of above/ground) to

The Factory Reading Series

and the poetry journal

Touch the Donkey

(included as part of the above/ground press subscription!). Just what else might happen? Current and forthcoming items include works by Pearl Pirie, nathan dueck, philip miletic, Sandra Moussempès (trans. Eléna Rivera), Carrie Hunter, George Bowering, Carrie Olivia Adams, Geoffrey Young, Dana Claxton, Julia Polyck-O'Neill, Sarah Swan, Andrew McEwan, Michael Turner, Buck Downs, John Barton and derek beaulieu (2016), as well as a whole slew of publications that haven't even been decided on yet.

Twenty-three years! As we edge even closer to twenty-five (as well as above/ground press' 800th publication, due any day now!). Can you believe it? There's been a ton of activity over the past year around

above/ground press

, from the continuation of

Chaudiere Books

(the trade extension, one might say, of above/ground) to

The Factory Reading Series

and the poetry journal

Touch the Donkey

(included as part of the above/ground press subscription!). Just what else might happen? Current and forthcoming items include works by Pearl Pirie, nathan dueck, philip miletic, Sandra Moussempès (trans. Eléna Rivera), Carrie Hunter, George Bowering, Carrie Olivia Adams, Geoffrey Young, Dana Claxton, Julia Polyck-O'Neill, Sarah Swan, Andrew McEwan, Michael Turner, Buck Downs, John Barton and derek beaulieu (2016), as well as a whole slew of publications that haven't even been decided on yet. 2017 annual subscriptions (and resubscriptions) are now available: $65 (CAN/US; $90 international) for everything above/ground press makes from when you subscribe through to the end of 2017, including chapbooks , broadsheets , The Peter F. Yacht Club and Touch the Donkey (have you been keeping track of the dozens of interviews posted to the Touch the Donkey site?).

Anyone who subscribes on or by November 1st will also receive the last above/ground press package (or two) of 2016, including many of those exciting new titles listed above (plus whatever else the press happens to produce before the turn of the new year), as well as Touch the Donkey #11 (scheduled to release on October 15)!

Why wait? You can either send a cheque (payable to rob mclennan) to 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1H 7M9, or send money via the paypal/donate button (above).

Published on October 13, 2016 05:31

October 12, 2016

Laura Broadbent, In on the Great Joke

You disappeared into obscurity for a long while, and your heroines often experienced exile as well. Is this the natural movement following an inner death, which is the first death?

Now I no longer wish to be loved, beautiful, happy or successful.I want one thing and one thing only – to be alone.Can I help it if my heart beats, if my hands go cold?And then the days did come when I was alone. Quite alone.No voice, no touch, no hand. How long must I lie here? Forever?No, only for a couple hundred years.Oh, no place is a place to be sober in. (“A POSTHUMOUS INTERVIEW WITH JEAN RHYS”)

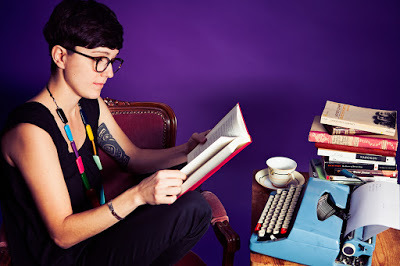

Montreal poet Laura Broadbent’s second trade poetry collection,

In on the Great Joke

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2016), is an exploration of film structure and voice, theory and narrative. There is something reminiscent in In on the Great Joke of the work of Anne Carson, as Broadbent utilizes the frame of poetry to write her way around and through theory, prose-blocks and conceptual bursts, as well as through offering introductions to both sections – “Wei Wu Wei / Do Not Do / Tao Not Tao,” a series of poems that include responding to short films, and “Interviews,” a series of poems around voice – as well as a final prose-piece to close the collection, “*Postscriptum: A Note on the Short Films Compromising Positions Featured Throughout this Text.” And yet, the explanation is an element of the text, articulating layers of framing throughout, which themselves lead to a series of further openings. In the introduction to the second section, “Interviews,” “What a Relief not to Meet you in Person: an Homage to the Alchemy of Reading,” she writes that “The following interviews are an homage to the alchemy of reading.” She continues:

Montreal poet Laura Broadbent’s second trade poetry collection,

In on the Great Joke

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2016), is an exploration of film structure and voice, theory and narrative. There is something reminiscent in In on the Great Joke of the work of Anne Carson, as Broadbent utilizes the frame of poetry to write her way around and through theory, prose-blocks and conceptual bursts, as well as through offering introductions to both sections – “Wei Wu Wei / Do Not Do / Tao Not Tao,” a series of poems that include responding to short films, and “Interviews,” a series of poems around voice – as well as a final prose-piece to close the collection, “*Postscriptum: A Note on the Short Films Compromising Positions Featured Throughout this Text.” And yet, the explanation is an element of the text, articulating layers of framing throughout, which themselves lead to a series of further openings. In the introduction to the second section, “Interviews,” “What a Relief not to Meet you in Person: an Homage to the Alchemy of Reading,” she writes that “The following interviews are an homage to the alchemy of reading.” She continues:From the outside, reading can seem isolated, antisocial, indulgent, boring or nerdy because the subtle magic is not immediately observable. When you are witnessing someone reading, if they are indeed a skilled listener and not a passive escapist (no judgement toward the joy of the latter), what you are actually witnessing is a transformation which is also known a magic. Magic can, at its most basic, mean a change that is wonderful and exciting. Objectively, texts are blocks of words in a certain order. One hundred copies can be made of the same book with the same words in the same order, and we can say, ‘These books are the same.’ But when the book is enmeshed with a human reader’s subjectivity, the words are transformed based on the particular configuration of the receiver’s conscious and unconscious structures. Subjectively, a text has many meanings indeed – one book can be one thousand different books if one thousand people read it. Furthermore, let it be said that when a person picks up a book they are choosing to listen as an activity, a powerful decision often overlooked. I see this choice as a very beautiful and elegant thing a human can do, completely devoid of class or any other divisive hierarchy. Seeing people read has never ceased to calm me, because they are choosing to listen, which is a gentle and intelligent and elegant and stylish choice. I am speaking of a certain kind of reading, and if you are reading this you know what kind of reading I mean, I mean reading as contact between souls.

Broadbent’s In on the Great Joke is very much an exploration of meaning, translation and boundaries, and how stories, including histories, are told, blurring perceptions, and the complexity of tales that might easily contradict. How are stories told and re-told? How do the stories alter through each subsequent telling? As she writes to introduce the first section, referencing the book’s title: “There are more than 170 English translations of the Tao Te Ching, each of which differently translates the first line about it not being translatable. Lao Tzu’s begrudging attitude is immediately made clear: the first line is about how futile this naming business is, since the Way cannot be named, and if it icould be named it would not be the Way, but if it must be named, it is named Unnameable. Most translations of the Tao Te Ching are accompanied by commentary, and these commentaries take great pains to talk about how the Way cannot be talked about. Just as I am talking about it now. This is part of the Great Joke.”

Your sense of history is remarkably melancholic – does joy fit into this long account of calamities?

There are only two seasons: the white winter and the green winter. Scenes of destruction, mutilation, desecration, starvation, conflagration and freezing cold. However, I have always kept ducks – and the colour of their plumage, in particular the dark green and snow white, seemed to me the only possible answer to the questions that are on my mind. (“A POSTHUMOUS INTERVIEW WITH W.B.SEBALD”)

Published on October 12, 2016 05:31