Stuart Harrison's Blog, page 3

November 28, 2013

The Pursuit of Happiness (Part Eleven of how I realised my dream of becoming a novelist)

When I was young, our family lived in a haunted house. At the time I wasn’t aware of  this, but years later I heard the stories and I’d always wanted to go back there and look at the place to see if I could sense anything of the weirdness that went on there. I mentioned this to Dale during one of our regular discussions during which she would ask how my new novel was progressing. By that she meant was it likely to be published soon and save us from hurtling over the financial cliff that was fast approaching. I told her it was going well, by which I meant that I had absolutely no idea what I was doing.

this, but years later I heard the stories and I’d always wanted to go back there and look at the place to see if I could sense anything of the weirdness that went on there. I mentioned this to Dale during one of our regular discussions during which she would ask how my new novel was progressing. By that she meant was it likely to be published soon and save us from hurtling over the financial cliff that was fast approaching. I told her it was going well, by which I meant that I had absolutely no idea what I was doing.

The novel was turning into another supernatural story, which was never really the kind of thing I’d planned to write. The setting was a rural village somewhere, much like the village I’d imagined we would live in when we came to England, which proved to be impossible to find. It occurred to me that the image I was chasing was of the place where I spent the first ten years of my life so I suggested that we go there. There was a specific logic behind the idea because I thought it might help with the novel. Maybe there were things buried in my memories that I was trying to get out without being aware of it. I’d read somewhere that first novels often have some kind of autobiographical element. Dale was curious just to see where I’d spent the early part of my childhood because I’d never really talked about it, so we decided to take a trip there and call it research. She probably suspected the novel was foundering and thought anything that would get me focused was a good idea.

The village was in Northamptonshire and was called Scaldwell. The way I remembered it there was a green right in the middle where there was an old water pump and three big oak trees, one of which was hollow. One side of the green was dominated by a farmhouse where a boy called Michael Allcock lived, though he was known mostly as all-cock-and-no-balls by the other village kids, because that’s the way kids are. Directly opposite was a large white house where we lived, called Hillside House, because it was built on a slope at the top of a hill. It had once been a bakery and the ovens were still there, though they’d been bricked up. Forming the boundary below the green was a six-foot high stone wall, behind which was the manor house and next to it was a post office and sweet shop. I remembered the big jars of coloured sherbet which we used to buy in paper cones for threepence, and gobstoppers that were a penny each, barley sugars and fruit gumdrops which you bought by the ounce. I didn’t expect any of it to look the way I remembered and during the drive from Dorset I talked it down. There were bound to be housing estates there now, the sweet shop would be long gone and the haunted house was almost certainly not haunted after all.

The route we took to get there took us through the town of Kettering which happens to be the closest town to the base where the US 8th Air Force was based during WW2. The first bombing raid flown from there was led by the major who later piloted the Enola Gay which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. There was a bypass so we didn’t have to go through the town, but I wanted to because Kettering was where my dad’s parents had lived. My dad moved to a house just outside the town after he and my mum divorced when I was ten, which was when we left Scaldwell. By the time Dale and I drove through Kettering with Mac in the back in a booster seat, I hadn’t seen my dad for something like twenty years. I remember as we hit the outskirts of the town I was thinking about that, and looking for anything I might remember. The funny thing was I hadn’t told Dale any of this. It struck me that I hadn’t even thought about it before we left Dorset, but I knew that couldn’t be true. When I was looking at the road-map I must have known what I was doing, but if I had I hadn’t acknowledged it to myself. It felt strange to be there again. I thought it would be weird if I saw my dad on the street. Maybe I would hang out the window and say something. Like, hey, guess what? It’s me. And I’ve got my son in the back of this car. Of course I might have to add that he was really small, so you can’t actually see him, but trust me, he’s there. I could stop and show him. But why would I want to do that, I wondered?

As we drove along a main road, following the signs toward the town centre, we passed an iron railing fence. Well, it was metal anyway. I have no idea if it was made of iron actually. Do they make iron fences? The thing is it was painted green and there were small spikes on the top of every upright that looked almost ornamental, though if you were to try to climb the fence and you slipped it might be nasty. On the other side of the fence was what looked like a park with lots of grass and a lake and even a narrow gauge railway. I suddenly knew what it was.

“That’s Wicksteed Park,” I told Dale, and she looked at me in surprise. “We used to go there when we were kids – my brother and sister and me. Dad used to take us every second Saturday after he picked us up. He had a sort of bronze coloured Cortina.”

She gaped at me, probably a bit bemused. “Your dad brought you here? After he picked you up from where?” She looked at the park as we passed the main entrance, which had big gates and ticket booths and was more impressive than I remembered.

There was a fairly big area devoted to swings and roundabouts, like an oversized version of the kind of kids playground you could find in practically any park in the country, but there was also a roller coaster, albeit a small and quite pathetic one. It looked like the sort of thing somebody might have once built, and having finished it, stood back and with a horrible sinking feeling realised they should have made it bigger. Even when I was twelve I’d ridden this thing feeling faintly embarrassed. After the slow climb to the top of the hill during which a tremendous sense of nervous anticipation had built, the plunge began and I opened my mouth to scream – and then it was suddenly over and I thought, Oh, was that it?

There was a fairly big area devoted to swings and roundabouts, like an oversized version of the kind of kids playground you could find in practically any park in the country, but there was also a roller coaster, albeit a small and quite pathetic one. It looked like the sort of thing somebody might have once built, and having finished it, stood back and with a horrible sinking feeling realised they should have made it bigger. Even when I was twelve I’d ridden this thing feeling faintly embarrassed. After the slow climb to the top of the hill during which a tremendous sense of nervous anticipation had built, the plunge began and I opened my mouth to scream – and then it was suddenly over and I thought, Oh, was that it?

There were other rides though, like the water chute where a sort of boat thing was hauled up a track and then released into a pool of dirty lake-water, which soaked everyone and elicited screams of delight. And the paddle boats of course, which you hired for half an hour and which looked like great fun but actually weren’t, and after five minutes we used to take ours back which always made the man who looked after them smirk in what I thought was a knowing way. We still hired them again next time though. Or at least dad did. He paid for everything. Best of all though was the train with its open-topped carriages that trundled around the lake, which for some reason I could never work out was exciting, even though it wasn’t. I think all trains are like that though. There was one bit where the track crossed a wooden bridge over a narrow part of the lake. You could look down as the wheels made a deep, slightly thrilling rumbling noise and imagine being chased by Indians or something. There were no aliens then, only Indians. And quite what the connection between being chased by Indians and a wooden bridge over a lake was, I have no clue.

I remember this though. We loved Wicksteed Park. It was England’s version of Disneyland and so in typically English fashion it was crap, but I had never been to Disneyland so I didn’t know just how crap it was. We had ice cream and candy-floss and dad used to follow us around watching us and probably wishing he was playing golf. Or maybe he didn’t.

“Tell me about your dad,” Dale said. It was a gentle, curious prompt.

When we reached the middle of town we passed a pub that was once a coaching inn. “He used to take us there. We’d sit in the car and he’d bring us coke and packets of crisps while he went inside for a drink. I suppose it was quid pro quo for putting up with Wicksteed Park.”

I was starting to realise why we were going to Scaldwell, and perhaps why I’d always wanted to write. To be continued.

If you’re enjoying reading this series, please share it with others who might be interested. Thanks.

November 21, 2013

The Pursuit of Happiness (Part Ten of how I realised my dream of becoming a novelist)

In May of 1997 I had my thirty-ninth birthday. It gave me cold sweats to think that next year I would be forty. We were living in a rented house in Dorset where I was working on my second novel, the first one having being rejected by every literary agent in the world, and to be honest I didn’t have much confidence that this one would fare any better. Part of the problem was I had no idea what to write about, which was a bit ironic given that I’d dreamed of doing this for as long as I could remember.

I was still at school when I decided I’d become a novelist. Harold Robbins was big  in those days and my mum had a couple of his books. I read them and loved them, especially the sex scenes, which in the England of 1972 were pretty daring. This was when halfway through cross-country a small crowd of teenage boys gathered to stare in silence at a black and white photograph of a naked woman somebody had found, torn from a copy of Health and Education. It was full frontal and her pubic hair was visible. Nobody said a word. The picture raised puzzling questions about female anatomy. Or maybe that was just me.

in those days and my mum had a couple of his books. I read them and loved them, especially the sex scenes, which in the England of 1972 were pretty daring. This was when halfway through cross-country a small crowd of teenage boys gathered to stare in silence at a black and white photograph of a naked woman somebody had found, torn from a copy of Health and Education. It was full frontal and her pubic hair was visible. Nobody said a word. The picture raised puzzling questions about female anatomy. Or maybe that was just me.

I’d read somewhere that Harold Robbins, the world’s biggest selling novelist, had been seen driving an open-topped Mercedes in Cannes with a young and completely naked blonde woman seated next to him. The vision this conjured of what it meant to be a novelist completely sold me on the idea. I had always read a lot. I imagined all novelists were probably something like the heroes in their books. Wilbur Smith had the Courtneys (I think) who had fantastic adventures in South Africa, Harold Robbins wrote about the bigger-than-life characters who founded incredible business dynasties and made films in Hollywood, any one of whom could easily be imagined driving around the South of France with a beautiful, naked woman, and Arthur Hailey wrote about the people who ran hotels and airports and managed to make them glamorous and exciting. This was the life for me. Unfortunately rural Dorset was a long way from Hollywood or South Africa and the inspiration I’d come to England for had failed to materialise.

Funnily enough, it didn’t seem to matter all that much. The birthday did give me a few moments of panic about where this was going to end, but it was outweighed by how much I was enjoying myself. It wasn’t just me. Dale was happy too. She had the baby she had always wanted and she had faith that it would all turn out well in the end. Our days were built around routines, like most peoples’ are, and none of it was particularly exciting. We were always up early which was a habit we’d developed when we worked at jobs we didn’t really like in the city and to beat the morning rush-hour we would leave home before six to make the trip over the Auckland harbour bridge to a gym near to where we worked. Now we got up early because our six month old son was always awake at the crack of dawn. We’d all have breakfast together and then I’d watch the teletubbies with Mack. He was fascinated by this programme and I found it strangely compelling though I wouldn’t have admitted it to anyone at the time. After teletubbies it was time for me to go upstairs and work on my novel. I was writing thousands of words a day in the hope that from the vague strands of story and fragments of scenes and characters, something cohesive would emerge. So far it hadn’t, but I was still having a good time. I did sometimes wonder why. There were a number of reasons, but one of them, oddly, was because what I was doing was really bloody difficult. This did make sense when gave it some thought though.

I remembered an occasion a few years earlier when I was working as national sales manager for a company that made health care products which were sold mostly through supermarkets. My job involved managing a team of sales reps based in various locations all around the country. I had an expense account and got to travel whenever I felt like it, drove a company car, attended the occasional overseas conference, was well paid and I was still in my early thirties. In short, my future looked bright. One day I was with one of the reps in a supermarket where we were cramming the shelves with our products, which was all part of the rep’s job, so that then they could persuade the department buyer to order more. Filling shelves is an activity that takes very little concentration or talent, and it occurred to me that despite my fancy job title and everything that went with it I was actually spending a fair amount of my time engaged in this mindless and repetitive task. It didn’t seem right to me that I had become a manager presumably because I’d exhibited a certain level of drive and ability, and yet I spent a lot of my time doing things that were actually not very difficult at all.

I found this a bit depressing and out of interest I calculated how many of the precious hours of my life I had wasted in this way. The result horrified me, though I can’t remember exactly what it was. I know it was a lot though, and I had a kind of epiphany that plagued me for days and weeks afterwards. If this was a movie, the main character would slowly bend down and pick a package out of a carton, then place the package on the shelf. His expression would reflect a mix of horror and consternation. How the bloody hell did this happen? I remembered my dreams of becoming a writer. I used to get A’s in English. What had gone wrong that I ended up filling supermarket shelves, albeit with a company car and an expense account? (The answer actually, lay in my decision to leave school at sixteen to ‘experience the world’ rather than stay on and eventually go to university. But who knows how that would have turned out)

So there I was, a couple of years later, broke, married with a child, living back in England where I was trying and failing to become a novelist. I was happy though, because every day I sat down at my desk and tried to write. At some point in that process, an amazing thing happened. Some inner door of my consciousness opened and released a torrent of creative thought. Characters and scenes appeared in my mind and it felt as if there was a huge jostling crowd of them trying to squeeze through a narrow opening all at once and the result was that they all kind of tumbled out haphazardly. Nothing made much sense if I tried to put them all together, but I still felt something was happening. It was hard work. My fingers flew over the keyboard, my mind racing ahead, trying to work out how I could use this or that scene, where it could lead to and what happens next. By the end of the day I was exhausted. I felt drained, utterly spent, but I was stretching myself, trying to live up to whatever potential I had, and that was a good feeling.

Of course there were other reasons to explain my sense of happiness. At 3 o clock most days I stopped work and went for long bike rides along the bridle paths of Dorset with Dave, my friend from down the road who still hadn’t found a job. I loved the freedom of being able to do that. It was late spring by then, and after a few weeks following this routine I could just about keep up with Dave. We would ride twenty or sometimes thirty miles along hardly used tracks, following ridges above fields of ripening crops bounded by hedgerows. A patchwork of browns and golds and yellow rape, sometimes shot through with vivid red sparks of poppies. There were mounds that were part of landscape, but spoke of the time when England was inhabited by tribes who built these mounds as burial chambers. Sometimes we came across arrangements of standing stones to remind me that Stonehenge wasn’t far away. There was a sense of history stretching way back into ancient times.

Some of the tracks took us along the coast, following the line of sheer cliffs that plunged to the foam and rocks below. Other times we rode through forests where bluebells carpeted the woodland, a sea of blue of green that took my breath away. On narrow lanes between hedgerows I encountered the smell of rosehip and dandelion, ordinary things that brought back childhood memories of the Northamptonshire village where I spent the first ten years of my life. Sometimes we saw buzzards and once I glimpsed a sparrowhawk hunting along the edge of a copse and another time a flash of slate blue as a merlin chased a small bird. The mornings were so light that Dale and I sometimes took Mack in his three-wheeled cross-country pushchair, which I swear we had the first example of in England, and walked through the woods near the village. We heard the unnerving shriek of deer, which if you don’t know what it is sounds like a banshee, and we saw foxes pause in their hunt to watch us pass.

Some of the tracks took us along the coast, following the line of sheer cliffs that plunged to the foam and rocks below. Other times we rode through forests where bluebells carpeted the woodland, a sea of blue of green that took my breath away. On narrow lanes between hedgerows I encountered the smell of rosehip and dandelion, ordinary things that brought back childhood memories of the Northamptonshire village where I spent the first ten years of my life. Sometimes we saw buzzards and once I glimpsed a sparrowhawk hunting along the edge of a copse and another time a flash of slate blue as a merlin chased a small bird. The mornings were so light that Dale and I sometimes took Mack in his three-wheeled cross-country pushchair, which I swear we had the first example of in England, and walked through the woods near the village. We heard the unnerving shriek of deer, which if you don’t know what it is sounds like a banshee, and we saw foxes pause in their hunt to watch us pass.

I didn’t know it then, not consciously anyway, but what was happening was the very thing I’d come to England to experience (apart from simply running away from the mess I’d made of everything). I was reconnecting with the countryside I knew when I was young, with familiar sounds, sights and smells. From all of that the germ of a story was beginning to form.

By the way, if you’re reading this series and you like it, please spread the word and share with your friends. Thanks.

November 14, 2013

The Pursuit of Happiness (Part Nine of how I realised my dream of becoming a novelist)

The house across the road from our new home was owned by a couple of about our age, who it turned out had not long returned from living in South Africa. I suppose because we’d recently arrived from New Zealand we had that fellow-world-traveller thing in common, which is a sort of smugness really. Jeremy and Janice threw a party for all the neighbours along the street to give us an opportunity to meet everyone. Not many people turned up actually, which was nothing to do with Janice and Jeremy, but rather that the neighbours turned out to be a funny lot as we eventually came to discover.

Among those we did meet were Dave and Jane who lived at the other end of the street. Jane was a schoolteacher and Dave had just been made redundant from his job. We got chatting and he told me he did a bit of bike riding. I’d just spent half an hour going on about how different the Kiwi lifestyle is compared to England. In New Zealand it’s all mountains and forests, and rivers and beaches and there are a lot less people. The weather is better too. I probably over-egged the pudding a bit. The way I portrayed it, everyone fishes, runs, kayaks, bikes, walks, climbs mountains, surfs and has outdoor barbecues all the time, even in the middle of winter. I actually didn’t do any of those things, but I might have given Dave a different impression. I mentioned that I did quite a bit of biking myself, and I’d even brought my trusty bike all the way to England with me. Dave thought that was brilliant, and since he had a bit of time on his hands he suggested that maybe we could go for a ride, though he said I’d have to go easy on him.

Among those we did meet were Dave and Jane who lived at the other end of the street. Jane was a schoolteacher and Dave had just been made redundant from his job. We got chatting and he told me he did a bit of bike riding. I’d just spent half an hour going on about how different the Kiwi lifestyle is compared to England. In New Zealand it’s all mountains and forests, and rivers and beaches and there are a lot less people. The weather is better too. I probably over-egged the pudding a bit. The way I portrayed it, everyone fishes, runs, kayaks, bikes, walks, climbs mountains, surfs and has outdoor barbecues all the time, even in the middle of winter. I actually didn’t do any of those things, but I might have given Dave a different impression. I mentioned that I did quite a bit of biking myself, and I’d even brought my trusty bike all the way to England with me. Dave thought that was brilliant, and since he had a bit of time on his hands he suggested that maybe we could go for a ride, though he said I’d have to go easy on him.

“No need to worry about that,” I said hastily. “I haven’t had a chance to ride since we left and that was months ago so I’m probably a bit out of condition now.”

The truth was that I’d hardly done any biking at all, but it was too late to back out. A couple of days later Dave turned up at our door at three o clock in the afternoon, which apparently I’d told him was when I usually finished work for the day. He was all ready for our first ride, kitted out in lycra and a high-tech helmet, brandishing a map that he’d been studying all day, trying to work out a route we could take on the local bridle-paths.

“I know you’re probably used to really wild stuff in New Zealand, but I haven’t done this for a while so I worked out something that won’t be too hard. It’s probably about twenty miles,” he said, half enthusiastically, half apologetically.

“Twenty miles?” I echoed, feeling ill.

“Sorry, yeah. That’s a bit short isn’t it?” He examined the map again and found a way we could add another five-mile loop onto it. I looked where he was pointing, trying to remember what all the squiggly lines meant and hoping they weren’t hills, though I was fairly sure they were.

The last time I had ridden twenty miles across country tracks was never. When Dale and I met, she had been into mountain biking, being a real kiwi from a country area, and since I was eager to impress her I’d bought a bike too. Hers was quite flash, a lightweight alloy model with about a hundred and twenty-eight gears and shock absorbers. Mine came from a discount store, was made from solid steel that weighed a ton and had a wheel at each end, but otherwise didn’t really resemble a proper mountain bike at all. It hadn’t worried me when I got it, mainly because I didn’t think it through properly, and besides, Dale was a girl so I didn’t think it made much difference how crap my bike was. I should have known better based on our first sporting experience together.

We hadn’t actually reached the stage of going out when I arranged to meet her and some of her friends one day when they were planning to do some jet-skiing. We were still in the get-to-know-each-other stage, during which I tried to impress her in various ways. It was a bit of a challenge because she’d told me once that she was attracted to tall, dark men who were built like rugby players, whereas I was short and fair and though rugby was played at the school I went to, I usually skived off round the back off the bike sheds for a fag during pe. However, I’m getting off track, so back to the jet-skiing. How hard could that be, I wondered? From what I’d seen you just sit down and ride it like a motorbike. The trouble is the jet-ski turned out to be the kind you stand up on, which it also turned out is much, much more difficult to master as I discovered. It wasn’t my skill on the bike that undid me though, so much as the fact that when I was offered a wet-suit to borrow when it came to my turn, I put the thing on inside out and back to front, which takes a bit of doing, actually. It took three of them to get me out of it and in again with the suit the right way round. Apparently Dale and her friends had a laugh among themselves while I was foundering about hopelessly in the water and repeatedly face-planting off the jet-ski.

“He’s not for you,” one of her friends wisely counselled her. (She was wrong)

Anyway, back to the biking. I shouldn’t have been surprised when I saw Dave’s slick machine. It made even Dale’s look like rubbish and mine look pathetic. I think when Dave saw it he began to appreciate that I might not be quite the expert that I’d sort of hinted at. He was very good though. When we got back about three hours later he didn’t say a word that could have been considered as even slightly smug. I had never felt so tired. No, tired is the wrong word. I was absolutely knackered. I could hardly stand up, but I couldn’t sit down either because my arse was so sore from sitting on that bloody saddle. The only good part was that it was over. At least I’d had a go. I actually felt a bit proud. Bruised, filthy and half-dead, but a bit proud. Dave looked as if he could do it again, which he probably could have. AS he rode off with a cheery wave he called out to me.

“See you tomorrow then.”

“Right,” I said. “Great.” I prayed it would rain and we wouldn’t be able to go. I mean hard out, pouring rain. Serious rain. When I looked up, there wasn’t a cloud in the sky though. Bloody typical.

November 5, 2013

The Pursuit of Happiness (Part 8) How I realised the dream of writing a novel

It was very exciting the day the movers arrived. It sounds like the beginning of a picture book for five year olds. They came in a big red lorry. It was true though. We were ridiculously excited.

We had just moved to the village of Broadmayne, a few miles from Dorchester.  It wasn’t a very big village, straddling either side of one the roads leading from Dorchester to the coast. There were thatched cottages that had been built hundreds of years ago, and a few that had been built last week to capitalise on the English enthusiasm for houses that have small windows and burn down easily. At least they were sympathetic to the environment though. Up the hill were streets with names like Cuckoo Close, or Badgers Walk, where the largely identical semis and detached brick and tile cookie-cutter homes looked exactly the same as those you might find in any town or city across the country. It was a shame really. The street names were the only nod from the company that built them to the fact that they actually were in the country. On the positive side they had central heating, the housing market was in free-fall to the point that people were posting their keys to the banks that held their mortgages, and rents were so cheap even we could afford them.

It wasn’t a very big village, straddling either side of one the roads leading from Dorchester to the coast. There were thatched cottages that had been built hundreds of years ago, and a few that had been built last week to capitalise on the English enthusiasm for houses that have small windows and burn down easily. At least they were sympathetic to the environment though. Up the hill were streets with names like Cuckoo Close, or Badgers Walk, where the largely identical semis and detached brick and tile cookie-cutter homes looked exactly the same as those you might find in any town or city across the country. It was a shame really. The street names were the only nod from the company that built them to the fact that they actually were in the country. On the positive side they had central heating, the housing market was in free-fall to the point that people were posting their keys to the banks that held their mortgages, and rents were so cheap even we could afford them.

We were grateful for the central heating on the day we moved in because we had no furniture. Not even a bed. Mac was only a baby so it didn’t matter much to him, but Dale and I slept on the bedroom floor, lying on assorted clothes and covered in coats to keep warm. It wasn’t that bad, but I did wake up early. From the window I watched as the sky lightened and the other houses in the street woke up. Curtains were drawn and lights went on and then one by one people started emerging from their front doors to get into their cars and head off to work and school. There were a few families with children of various ages, including a couple directly opposite who had two young girls. The man I took to be the father and husband wore a suit and drove a Mercedes. Next door was a couple in their forties or so, with no obvious sign of children. Later we’d discover he was a chemist in a nearby town. Further down the street there was a policeman whose wife was also in the police, a couple who owned a successful business, a helicopter pilot, a teacher and her husband who had teenagers, and a few retired couples. It all seemed fairly normal.

We were kept busy for the next few days. We’d contacted the removal company responsible for shipping all our worldly goods around the world in a container and arranged to have it all delivered to our new address. At the New Zealand end a friendly crew had arrived to pack everything for us, which was a more expensive way of doing things, but was recommended for international moves. Part of the deal was that at the UK end our goods would be unpacked for us too. The two surly blokes with London accents who arrived in the truck apparently hadn’t been apprised of the arrangement though, and once they’d dumped the last box in a garage you could no longer move in they asked for a signature to confirm that everything had been delivered in a fit state. I pointed out to them that I wasn’t sure how we could be certain that was actually the case, since they hadn’t unpacked anything yet, to which I was flatly told that unpacking wasn’t part of the job and the clipboard was thrust at me again. The tone was distinctly unfriendly, which was funny, because when I’d been helping them unload they had been almost jovial. Well, they grunted a bit anyway. It had been a long time since I’d lived in England and I’d forgotten the way things worked there. In New Zealand, helping the removal crew lug stuff on and off the truck would be perfectly normal. It’s a fairly egalitarian society, where everybody mixes fairly comfortable. It’s not unusual to have friends over for a barbecue, some of whom may be lawyers or doctors, while others build fences or whatever for a living. It isn’t like that in England, which I was quickly discovering is still as class riven as ever, resentment and condescension running freely in opposite directions up and down the social scale. These two blokes probably thought I was a twat for helping them. I was chatting away, talking about where Dale and I came from and what it was like on the other side of the world, in the mistaken belief that either of them gave a toss. As soon as they could they were prepared to abandon us with the job half done, no doubt to nip off to the nearest pub and have a laugh about it all. I knew what Dale and I had paid for though and their attitude annoyed me, so I went inside to phone their head-office. As I spoke to an extremely uninterested person on the other end of the line I looked out of the window to see Bill-and-Fred-grumpy-bastards driving off in their lorry. Neither of them gave me a second look. Still the last laugh was on them, because I’d been planning on giving them a twenty quid tip, which they definitely wouldn’t be getting now.

So, after about three days of solid unpacking and lugging stuff around, we had something resembling a home again. There were our familiar couches and our bookcase complete with my favourite books, the dining room table, the stereo and speakers and our CD collection, our own bed and linen and towels and kitchen paraphernalia. It was a bit like Christmas as a kid, opening all those boxes to find things we’d forgotten about, but which reminded us of who we were and the lives we’d left behind. Others were a bit mystifying. We found a half burned candle, an empty baked bean can, some newspapers that had been left out to be thrown away. We’ve been through this exercise a few times now and it’s always like this. When you pay for a pack and ship service, they pack everything. I mean literally. I realised eventually that it makes sense. Better to take no chances and pack it all, no matter what, than risk an irate owner ranting that his mint 1914 copy of the Times with the headline announcing war in Europe has gone missing, or they’d neglected to pack the candle that had special priceless sentimental value because it was the one that was burning the night the baby was born or some such thing. All of which I bet would really happen. So, best solution, ask no questions and pack it all. Which is what they did. The empty baked bean can was still a bit hard to fathom though. Like I said, unpacking those boxes was a bit like Christmas. Every one held some surprise or other. It made us feel a bit homesick, but it was too late for that so we looked at it the other way, which was that we’d brought a bit of home with us. I was even a bit sorry when we came to the last box.

We celebrated by spending the twenty quid I’d earmarked for the movers and bought a bottle of red wine and a couple of steaks. On the way to bed I paused by the room that I’d set up as my office. My computer was waiting there for me on the desk, and I pictured myself sitting there each day crafting the novel that I was going to write. The one that would make this all worthwhile. At least I tried to picture it.

As I closed the door I heard a faint ghostly mocking, like the laughter of two blokes driving up the A4 back to London.

October 24, 2013

The pursuit of happiness (Part Seven of how I realised my dream of becoming a novelist)

What is happiness? I used to ask myself that question, to which most people could provide an answer of sorts. Obviously happiness is a state of mind so many people focus on what might help them achieve that state. Is it money? Love? Friends? Family? The place where you live? The list could be as endless as it is individual. What makes one person happy, another may be indifferent to. The car enthusiast who has always wanted to own a Ferrari is unlikely to be thrilled by a generic family saloon, just as an art lover probably won’t be impressed with a paint-by-numbers canvas from a sweat shop in Asia. In any case, even a fleeting examination of the question reveals that possessions of any sort do not contribute to a general feeling of happiness, though it’s possible they might give rise to brief episodes of pleasure, which is not the same thing.

What is happiness? I used to ask myself that question, to which most people could provide an answer of sorts. Obviously happiness is a state of mind so many people focus on what might help them achieve that state. Is it money? Love? Friends? Family? The place where you live? The list could be as endless as it is individual. What makes one person happy, another may be indifferent to. The car enthusiast who has always wanted to own a Ferrari is unlikely to be thrilled by a generic family saloon, just as an art lover probably won’t be impressed with a paint-by-numbers canvas from a sweat shop in Asia. In any case, even a fleeting examination of the question reveals that possessions of any sort do not contribute to a general feeling of happiness, though it’s possible they might give rise to brief episodes of pleasure, which is not the same thing.

There is a report that is produced every year by some agency or other with nothing better to do, and based on a number of factors and various interpretative models a determination is arrived at as to which nation has the happiest population overall. I’ve no idea how the conclusions are arrived at, but I suppose it must depend on the answers to questions that attempt to winkle out how satisfied people are with their lot. Invariably the most satisfied are those from relatively poor countries, though not ones where the inhabitants are starving or lacking the other basic necessities of life, such as shelter, security, clean water and a reasonable standard of health care. Even with those caveats, the report always concludes that in relative terms and excluding the extremes, the poorest people are also the happiest.

In my own experience I think there’s something in this, but it’s not quite the way it seems. It might be more accurate to say that given the basic necessities are taken care of, then personal wealth has little to do with happiness. Therefore it must lie elsewhere. Of course many of the things I mentioned, particularly personal relationships of all kinds, must figure strongly in the equation, but I’ve come to the conclusion that there is one other very important factor. To be generally happy, I think people need to feel that they are doing something worthwhile with their lives, that they are fulfilled in some way, that they have a purpose, or however else you want to term it. That in itself can mean almost anything and vary from person to person. Whatever the thing is could also change over time, perhaps many times. It might relate to whatever an individual does that occupies most of their waking hours, be it raising a family or working at some sort of job, though the reality for many is that this is probably not the case. A big chunk of people’s happiness is eroded because they are compelled by economic and other circumstances to work at jobs they either dislike or at best are ambivalent about. No matter how fulfilling other areas of their lives are, this bit will always drag them down.

There is a point to all of this in terms of the ongoing story of how I ended up sitting here writing this on a Friday afternoon instead of doing the things I liked a lot less in the years before I decided to try to become a novelist. I did eventually realise my dream, of course, but it didn’t happen overnight. Following our exit from the first village where we lived for a short while, we headed up the coast into Dorset, a county I’d never visited before. When we arrived in Dorchester we visited estate agents looking for somewhere to rent. It seemed like a pleasant town, and the association with Thomas Hardy seemed like an omen. He was a famous English novelist after all. I should know, I’d been forced to read one of his novels at school, though to tell the truth I don’t recall liking it much and I haven’t read one since.

Anyway, we were told about a house in a nearby village and I was still keen on living in a village despite the previous experience, so we drove out to have a look. I’ll come to the specifics in future posts, but what followed was perhaps the happiest period of my life so far. For the next almost eighteen months there was no money coming into our household and every day the financial precipice seemed a little bit closer. Actually it was a bit closer. There were to be more rejections from agents, plenty in fact, as reward for my hard work. There was self-doubt, worry about the future, and uncertainties of all kinds… I could go on, and I will as I said, but I had Dale and we had Mac and a roof over our heads, food on the table, and every day I sat down and tried to write a novel, something I’d wanted to do since I was at school twenty odd years earlier. For the first time in my life I felt I was doing what I really wanted to do with my life. I had a purpose. Despite the financial stuff, I was as happy as I’ve ever been.

I just felt like waxing philosophical today.

October 17, 2013

The Sound of Doors Slamming (Part Six of How I Became a Novelist)

Nobody enjoys rejection. One of my early teenage memories is of approaching a girl I liked at a disco to ask her to dance. The excruciating walk across the expanse of the community hall between records, through the spectrum of coloured lights cast on the dusty floorboards which foiled my attempts at invisibility. All the girls on one side noticing my approach, whispering to e ach other, waiting to see who I had in my sights. Conscious of the boys behind me, grinning and nudging one another, eager to witness somebody’s humiliation so long as it wasn’t their own. Finally I was there, irreversibly committed. I attempted a confident smile which somehow became a terrified grimace. Her eyes, which I saw up-close were an even more startling shade of blue than I had realised, widened, conveying a silent plea which I understood was meant to spare me, but it was too late. The words I had imagined speaking with casual ease fell from my mouth like bricks.

ach other, waiting to see who I had in my sights. Conscious of the boys behind me, grinning and nudging one another, eager to witness somebody’s humiliation so long as it wasn’t their own. Finally I was there, irreversibly committed. I attempted a confident smile which somehow became a terrified grimace. Her eyes, which I saw up-close were an even more startling shade of blue than I had realised, widened, conveying a silent plea which I understood was meant to spare me, but it was too late. The words I had imagined speaking with casual ease fell from my mouth like bricks.

“Do you want to dance?”

Following this, several seconds of silence as I unconsciously held my breath, as did the rest of the room, or so I imagined. Time slowed to a crawl. My heart thudded.

“Sorry, me and my friend are going outside,” she said with vague pity.

Of course they were. Only then did I realise that the agony of the walk there was nothing compared to the return, weighed down by the humiliating burden of rejection, the silence like an unbearable shriek, every step taken with limbs that behaved as if they belonged to somebody else. I prayed for the DJ to play a record and was sure I caught him watching my walk of shame with a glint of malicious amusement. He waited until I reached the company of my friends where I could look forward to being mercilessly mocked, before he put a record on the turntable. It was Jimmy Cliff singing I Can See Clearly Now, which seemed like an ironic choice to me.

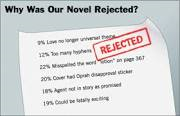

The first novel I ever submitted to literary agents reminded me of that occasion at the disco. I can vividly recall watching through the window when the postman arrived each morning. As he delved into his bag my heart would race and my breath catch in my throat. I prayed for an ordinary, everyday business-sized envelope containing a letter from somebody eager to represent me. What I dreaded was something much larger and fatter, something big enough, in fact, to contain the first three sample chapters of my novel which I had submitted to fifteen agents carefully chosen from the Writers and Artists Yearbook for 1997. I was pretty confident that at least one of them would love what I’d written. Fifteen times I was proved wrong. Fifteen times I heard the thud of my manuscript being returned as it hit the floor in the hall. On some days I suffered the double or even triple humiliation of hearing not one, but a series of thuds. Inside there was always a form rejection letter. Regrettably my novel wasn’t considered appropriate for this agency blah blah. The echo of that girl from more than twenty years earlier rang in my ears.

agents carefully chosen from the Writers and Artists Yearbook for 1997. I was pretty confident that at least one of them would love what I’d written. Fifteen times I was proved wrong. Fifteen times I heard the thud of my manuscript being returned as it hit the floor in the hall. On some days I suffered the double or even triple humiliation of hearing not one, but a series of thuds. Inside there was always a form rejection letter. Regrettably my novel wasn’t considered appropriate for this agency blah blah. The echo of that girl from more than twenty years earlier rang in my ears.

“Sorry, me and my friend are going outside – and the book you’re going to write one day won’t be any good either.”

They say that rejection is something an author has to come to terms with, to accept as an inevitable part of the journey to becoming published and I have found that no truer words have been spoken. I’m in a new phase of my writing career now and I’m experiencing the blunt force of rejection again, but I’m older and wiser and probably a bit battle hardened, so it doesn’t hurt so much these days. Seventeen years ago, however, it felt a bit like the sky was falling.

By the time the rejections began coming in, it was early spring. Dale and I sat down over dinner and a glass or ten of wine to take stock. The plan appeared to be unravelling a bit. Our money was dwindling at a constant rate, Mac was already six months old, and it didn’t look as if a publishing contract would materialise anytime soon. I needed to have another go, I told Dale. I’d recovered from the initial kicking to my ego and after a sober analysis of my novel I concluded that there were issues. What it came down to was that the manuscript I’d sent out wasn’t really part of a finished novel. I had written what amounted to a corrected first draft. It had taken me about three and half months, and I thought if I spent the same amount of time again on rewrites, I might have something worthwhile at the end if it all. There was a problem, however, inasmuch as I was no longer at all sure that I wanted to write horror novels. I’d never really chosen horror as a genre anyway, it just sort of turned out that way as I unconsciously expressed how I felt about the village we had ended up in. Nothing had worked out the way I’d imagined it would, and my unconscious mind had worked all my tangled fears and disappointments out through a story about a young couple who found themselves pitted against a range of malevolent forces. I’ve since learned that writing is often unintentionally cathartic.

I decided that rather than rework my novel, I would attempt something completely different, and this time I’d take more time to ensure I got it right before I sent it out. Having made that decision, I thought it would be a good idea to make a fresh start in other regards too. I didn’t really like the cottage we were living in, or the village, or the postman, or the pub along the road with its regular trio of unfriendly patrons. When I suggested to Dale that we should move, she agreed, and we began looking straight away. It soon became clear that there was nowhere nearby where we wanted to live, so decided to just pack up and look further afield, which is how we found ourselves leaving the village a week later with the car loaded with all out possessions, Mac strapped into his seat in the back, and no clear idea of where we were heading. It was a repeat of what had brought us to England, and to Devon four or five months earlier. We were running away from another failure, chasing that elusive rainbow, or at least I was, though I was oblivious to this at the time.

As we passed the pub for the last time, the landlord happened to come outside. He saw the laden car and me behind the wheel and he must have guessed we were leaving and to my surprise he raised his hand to wave. As I automatically returned the gesture, it struck me that he had never meant to be unfriendly, rather it was simply that people who live in places like that, who have probably spent most of their lives there, are by nature very reserved. They had never mocked me as I’d imagined. If anything they were bemused by my presence. I spoke with a funny accent (having picked up a New Zealand twang during my years living there) and (as the postman would have told everyone) I was trying to be a writer. I know now that people regard novelists as oddities. They spend all day making up stories in their heads, which doesn’t seem like a real job. Somebody once asked what kind of books I write and when I talked about the genres I have dabbled in he looked puzzled.

“You mean they’re all lies then?” he wondered, grasping that I was talking about fiction.

It turned out he’d never read a novel in his life. I imagine that the landlord of the pub and his friends hadn’t either. In retrospect I think they found me perplexing. A man should drive a tractor or build a barn or even run a pub, occupations that were of some practical use. What was the point of writing books? And as I looked in the rear-view mirror and saw him go inside again I also heard him add to that; Especially ones that, according to the postman, nobody wanted to read.

October 10, 2013

It’s the journey, not the destination – the highs and lows of realising my dream of writing a novel (part five)

There was a lot to be excited about that first Christmas we spent in England. Christmas in New Zealand means beaches and sunshine, the beginning of summer with long, warm evenings and barbeques with friends. It had taken me a long time to get used to all that, being the opposite of everything I had experienced growing up in Warwickshire, and I had never quite gotten over the feeling that it was all wrong. I wanted snow and a fireplace, a tree with lights and tinsel and chocolate money for Mac (our baby boy) which I would eat as he was too  young. I also wanted turkey with all the trimmings, which admittedly we had in New Zealand too, but it’s not the same when the temperature is in the mid-twenties and the gravy smells a bit like sun-lotion. I couldn’t wait. Christmas carol singers at the front door, Christmas specials on the telly. It used to be Morcambe and Wise and Bruce Forsythe when I was growing up, but Eastenders would do. Actually we had started watching Eastenders when we arrived and had become huge fans. Best of all though, we had friends arriving. A couple we knew from Auckland phoned and asked if we wanted visitors. They were working in a pub in London and I think they wanted to see familiar faces as much as we did.

young. I also wanted turkey with all the trimmings, which admittedly we had in New Zealand too, but it’s not the same when the temperature is in the mid-twenties and the gravy smells a bit like sun-lotion. I couldn’t wait. Christmas carol singers at the front door, Christmas specials on the telly. It used to be Morcambe and Wise and Bruce Forsythe when I was growing up, but Eastenders would do. Actually we had started watching Eastenders when we arrived and had become huge fans. Best of all though, we had friends arriving. A couple we knew from Auckland phoned and asked if we wanted visitors. They were working in a pub in London and I think they wanted to see familiar faces as much as we did.

It all went quite well. It even snowed a bit. Jenny and Mike arrived driving a Volkswagen van. They had been traveling in Europe, as Kiwis and Australians do, although I was a bit baffled that our friends had chosen to make their trip in the winter. Perhaps they forgot about the opposite seasons in the northern hemisphere. They complained that it had been cold on the beaches in Greece, so they’d cut their trip short and returned to London. Anyway, it was good to see them. We took them to the local pub and with the four of us and the baby too, we outnumbered the locals. The locals were used to seeing me there, sitting quietly with my pint most evenings. Of course they didn’t know I was secretly observing them and that they had all become characters in my horror novel. I hadn’t planned on writing horror, because I didn’t really have a plan at all, but I was enjoying myself. It was about a young couple who move in to an isolated village and find themselves trapped in a nightmare. In reality the village wasn’t like that. I was just expressing the sense Dale and I had of being a long way from everything we knew, and the looming terror that lurked in the pages of my book was our own very uncertain future which was an ever-present shadow we tried hard to ignore. What if this didn’t work out? What if my novel wasn’t published? A lot of what-ifs.

Jenny and Mike stayed for two days. We drank and ate and opened small presents that we had bought for each other and put under the tree, which was a real one that smelt of pine instead of plastic. For Dale and I, this was a special year. Of course there was the disastrous business collapse that resulted in the loss of almost everything we had and precipitated our mo ve to England, but that’s not what I mean. Dale had given birth to our first child and we had gotten married, unfortunately (in the eyes of Dale’s parents) in that order. The marriage ceremony took place at the registry office a few weeks before we left Auckland, and was followed by a glass of champagne on the beach with our friends. No special dress for Dale, no bridesmaids or reception attended by friends and family, just us and then home to carry on packing.

ve to England, but that’s not what I mean. Dale had given birth to our first child and we had gotten married, unfortunately (in the eyes of Dale’s parents) in that order. The marriage ceremony took place at the registry office a few weeks before we left Auckland, and was followed by a glass of champagne on the beach with our friends. No special dress for Dale, no bridesmaids or reception attended by friends and family, just us and then home to carry on packing.

So this was the very first Christmas we were spending as a family, a real one complete with small child. We bought him a present even though he was oblivious to the occasion. It was one of those things you put babies in that allows them to be upright without falling over, in this case a sort of bouncy seat set in the middle of a circular contraption on wheels made of plastic. There were various activities arranged on a circular shelf around him. Mainly things he could hit that made a noise, which delighted him. While we sat around the fire, drinks in hand, lights on the tree and snow falling outside the cottage, Mac bounced up and down like a maniac, the happiest child in the world, occasionally regurgitating bits of mashed food and drool. Our baby. My son. I was thirty-seven years old, my career a tangled wreckage behind me, the future ever-so-slightly scary if I thought about it, which I resolutely didn’t. Gone was the company car, the expense account, the monthly salary, the quaint villa we’ d bought near the beach. We were happy though. In fact I had never been so happy, which made me think about what was truly important in life. I don’t know what conclusion I came to though. Full of cheap wine and Dale’s home-made, only slightly burnt mince pies, I fell asleep half-through the Eastenders Christmas special and dreamed of my novel stacked high in shop windows by that time next year .

d bought near the beach. We were happy though. In fact I had never been so happy, which made me think about what was truly important in life. I don’t know what conclusion I came to though. Full of cheap wine and Dale’s home-made, only slightly burnt mince pies, I fell asleep half-through the Eastenders Christmas special and dreamed of my novel stacked high in shop windows by that time next year .

October 3, 2013

This is how I realised the dream of becoming a novelist (part four)

The thing about quaint, centuries old cottages in England, is that in the winter they are bloody freezing. The one we rented was, anyway. There was no central heating, something we should probably have realised before we signed the rental agreement, but I had lived too long in New Zealand where nobody has central heating. It didn’t even occur to me to check. It does get cold in New Zealand in winter, especially in the south island, but we were from Auckland where the climate is sub-tropical. Winter is more wet than cold. A decent fire in one room will generally warm the whole house, and I had spotted the fireplace in our cottage. I imagined sitting there in the evenings in front of the hearth, fire blazing, a solid day’s writing under my belt, maybe after a quick drink at the pub conveniently located fifty yards down the road.

does get cold in New Zealand in winter, especially in the south island, but we were from Auckland where the climate is sub-tropical. Winter is more wet than cold. A decent fire in one room will generally warm the whole house, and I had spotted the fireplace in our cottage. I imagined sitting there in the evenings in front of the hearth, fire blazing, a solid day’s writing under my belt, maybe after a quick drink at the pub conveniently located fifty yards down the road.

The first snow of the year arrived practically the day we moved in. We didn’t know it then, but that winter of 1996/97 was going to be one of the coldest in recent times. I lit the fire the first night we were there and filled the cottage with thick, choking smoke. Dale had to sit with the baby in the car while I opened all the windows and doors to clear the smoke. I was afraid I’d set the chimney on fire and wondered if we would get our deposit back if I managed to burn the place to the ground. As it turned out there wasn’t a fire, but the chimney was blocked. We went to bed early that night because it was the only place we could keep warm. The bedroom was like an icebox. Our breath appeared in clouds and the windows iced up. The rosy tint on my glasses was fading fast. This was the idyllic country sojourn I had described in such optimistic detail to Dale when I persuaded her we should move to England? A nagging worry began to take root in my mind. What if the other, slightly more crucial part of my dream was similarly flawed – the bit about becoming a published novelist?

Still, there was always the pub. Unfortunately, being very new at the parenting thing, I hadn’t considered where the baby fitted into the cosy vision I had of Dale and I sitting in front of the blazing fire (blazing fires become a bit of an obsession that winter) in the bar. I suppose I thought we’d take the baby with us and he would sleep and gurgle and do whatever babies do, while we chatted over drinks and got to know the locals, who would undoubtedly be friendly. I  imagined they would ooh and ah and we’d proudly look on, because nobody else in the world had ever given birth, had they? Actually, though, babies aren’t very welcome in pubs because they tend to cry a lot and nature has designed that sound to achieve maximum attention. It’s something like having a screwdriver driven through your ear. After one disastrous attempt, Dale decided that I would have to have my evening drink at the pub alone. She did try feeding the little sod to quieten him down, but apparently a young, attractive mother whipping out her breast for even that very natural function, was not the norm in England. At least not that part of England. There were only a couple of oldish men in there at the time. They leered in the unsettling manner of a pair of escapees from a Stephen King novel.

imagined they would ooh and ah and we’d proudly look on, because nobody else in the world had ever given birth, had they? Actually, though, babies aren’t very welcome in pubs because they tend to cry a lot and nature has designed that sound to achieve maximum attention. It’s something like having a screwdriver driven through your ear. After one disastrous attempt, Dale decided that I would have to have my evening drink at the pub alone. She did try feeding the little sod to quieten him down, but apparently a young, attractive mother whipping out her breast for even that very natural function, was not the norm in England. At least not that part of England. There were only a couple of oldish men in there at the time. They leered in the unsettling manner of a pair of escapees from a Stephen King novel.

I forget the name of that pub, but it did become my habit to nip in for a quick pint after dinner. There were never more than two or three people there, including the landlord. I never did get to know any of them though. It was like one of those films (or novels – Stephen King again) where the newcomer to the creepy village tries valiantly to fit in with locals only to discover that they seem to regard his efforts with vaguely unpleasant amusement. I would open the door and step over the threshold, the wind howling in my wake, shaking the snow off my coat and flapping my arms for warmth as if I’d trudged miles across the moors instead of fifty metres along the road. Glad for the cheery glow of the fire (there was a fire, so that was something) I’d nod in the general direction of the bar and remark on the weather. One of the patrons would mumble an incomprehensible response in a thick west-country accent and nudge his companion in the ribs, producing snickers of amusement which I tried not to interpret as being at my expense, though it clearly was. I’d buy my pint and stand at the bar awkwardly for a bit, before moving to a table closer to the fire, imagining a dark secret lurking at the heart of the community, of which I would only become aware when it was too late.

Perhaps all of this explains why the novel I found myself writing was a horror story, set in a creepy village in the south-west of England. I spent my days in a small, freezing cold room upstairs in the cottage, practically sitting on top of a two-bar electric heater, my fingers flying across the keyboard of my brand-new computer, the first I had ever owned. Actually my fingers didn’t exactly fly. I was a two-fingered typist and I was new at this, so they sort of hovered a lot and occasionally stabbed when I found the letter I was looking for. Progress was slow at first. It was frustrating because the story and characters, all of which I was making up as I went along, were racing far ahead of my ability to record them. Over the ensuing weeks, though, I became more proficient and the word-count began to grow at a satisfying rate. I gave my fellow regulars at the pub, starring roles in the story as silent revenge. I depicted them savagely as dolts and ignorant yokels, and one in particular who I was certain often made snide comments about me to his idiot friends, I had engage in unnatural practices with farm animals.

While I was busily living this strange double life of reality and fiction, the boundaries between which were becoming increasingly blurred, I was completely unaware that the movie it brought to mind now was the one where the writer slowly goes a little bit mad. Now it was The Shining (Stephen King again!). Actually it wasn’t quite that bad, but I was learning that being a novelist means that you spend a lot of time in your own head. Not always a good thing.

As for Dale, she was happy looking after the baby and making expeditions to the nearest town where there was a Tescos. She began watching cooking programmes on TV and experimented with recipes. Every night we sat down to some feast she had prepared, along with a bottle of wine, though maybe she still wasn’t drinking then because she was breast-feeding. We had decided that we wouldn’t be mean with our money when it came to the necessities. I was thrilled. I had married a woman whose idea of dinner prior to this was to heat a bottle of supermarket spaghetti sauce in the microwave before pouring it over badly cooked pasta. To my surprise, and I think Dale’s too, she found that she enjoyed cooking and was actually quite good at it. Life began to settle into a routine. Christmas was approaching and we heard from friends from New Zealand who had been travelling in Europe, who promised to come and visit us. I couldn’t wait to take them to the pub. For once I wouldn’t be outnumbered there.

September 26, 2013

How I realised the dream of writing a novel (and made a million along the way) Part three

I’ve already explained the reasoning behind the decision to move from New Zealand to England so that I could write a novel. It was mostly about escaping from a disastrous business venture, but there was another, valid reason. When I arrived back in the UK with my wife Dale and our three-week old baby, it had been fifteen years since I’d called England home. I had emigrated to New Zealand at the age of twenty-two to join some of my family who’d been living there for almost a decade. During those fifteen years I had embraced the kiwi lifestyle and climate. It was and is a great place to live (I’m back there now). When I thought about writing a novel though, the setting I always imagined was England. It was where I’d grown up, the place I knew best and they do say write about what you know.

been living there for almost a decade. During those fifteen years I had embraced the kiwi lifestyle and climate. It was and is a great place to live (I’m back there now). When I thought about writing a novel though, the setting I always imagined was England. It was where I’d grown up, the place I knew best and they do say write about what you know.

I didn’t actually know what I was going to write about yet. For the moment though, there were more urgent concerns, like where we were going to live. We went to stay with an uncle and aunt who lived in a sleepy market town in Northamptonshire called Oundle, where there is a hotel that was once a coaching inn, parts of which date from the year 686 AD. The oak staircase was brought from nearby Fotheringhay castle, where Mary Queen of Scots was executed in 1587. Her ghost supposedly haunts the staircase, and one of the bedrooms is also meant to be haunted (though not by the dead queen). I worked at the Talbot Hotel once as a waiter. I was sixteen and it was my first job after I left school. I was fired after a few months because I phoned in sick for the morning shift and then made a miraculous recovery and took my girlfriend there for dinner the same evening. Probably not a clever move. The point about Oundle and the Talbot, though, was my memories of these places. This was the England where I grew up (not literally - I actually grew up in a town called Leamington Spa in Warwickshire). I felt I had to reconnect with my personal history that was rooted in places like these, and only then could I write a novel. Whatever it would turn out to be about.

With this mind-set we left my uncle and aunt’s house (which is eighteenth century and everything an English house should be) and set off in search of somewhere to live. We had bought a second-hand car, or more likely tenth-hand, at auction, loaded our worldly possessions in the boot, except the baby who was in the back seat, and bought a road map. I considered heading towards Leamington Spa, but instead decided to go south-west towards Somerset, Devon and Cornwall. As a child I had spent family holidays there. I had fond memories of picturesque villages and winding lanes, cliffs with views of the sea. You could smell the salt and the sand before you actually saw the coast, I remembered. There would be small windblown sand-drifts in the lanes, and then we knew we were close. The excitement I experienced as a child seems odd to me now. Is that because in New Zealand almost everyone lives near a beach, and they’re much better than the ones in England anyway? Or is it that children in those days were easily pleased? Simpler times and all that. I can picture my own children rolling their eyes. They don’t even like the beach or the sea. Especially the sea. It may have something to do with the fact that I almost drowned us all after I learnt to sail and insisted we spend holidays on a yacht I bought. I actually wasn’t very good at sailing.

What I was looking for then, as we drove across England with a an alternately sleeping and wailing child in the back, was the England I remembered. The one that didn’t actually exist anymore and probably hadn’t for a long time, including when I grew up there. I wanted to rent a chocolate-box cottage in a chocolate-box village where there was a sweet shop (like the one in the village where I spent the first few years of my life) and a pub and everyone smiled and said hello to each other and drove tractors and Landrovers. The old-fashioned sort with a canvas back, not the flash new ones. I had forgotten, or possibly hadn’t noticed, that all those quaint villages are actually surrounded by modern housing estates that possess all the charm of the dog-shit that fouls the pavements throughout the UK to a mind-boggling degree. That was something else I hadn’t noticed growing up there. Just as people who live there don’t seem to notice it now. If I mention it to an English person they always look a bit baffled, but honestly, it was one of the first things that made an impression on me during that time of searching. It wasn’t just me either. Dale couldn’t believe how carefully you had to tread. The stuff was everywhere. Dale grew up on a farm and she was certain there was more shit between WH Smiths and Boots on the high street of your average English town, than in the slurry pond on the farm. A slurry pond is where they put all the cow shit, by the way. I should also mention, though I’m aware I’m drifting off topic here, that dogs are carnivores and cows only eat grass. If I had to choose which pile of crap I’d rather stand in, I know which it would be.

So we drove into town after town, and village after village all chosen using the road map for their off-the-beaten-track locations that promised the best chance of not having being surrounded by hundreds of more or less identical semi-detached Barrett Homes. The trouble is, nowhere in England is really off-the-beaten-track anymore. It is a very small country with a great many people living there. Geographically it’s the same size as New Zealand, though one has sixty-five million inhabitants and the other less than five. When we drove to Devon when I was a child, it was an adventure. There was a motorway for part of the journey, but it ended quite soon and then we were driving along unfamiliar roads, through towns and villages and stunning countryside. Now there are motorways everywhere. It’s like driving on a concrete conveyor belt. Of course I avoided them, choosing less busy routes. But there are no less busy routes. The volume of traffic was a real surprise. As was the sheer number of villages we encountered. We would leave one, drive for thirty-seven seconds, turn a corner and be in another. It hadn’t seemed like that when I was young, but I suppose that was because I was riding my ten-speed bike with ape-hangers, which is slower than driving a Volvo. Though only just. Actually I like Volvos’. We bought another one years later, and it was almost new!

I think it was Dale who determined that our search had to stop. Or at least my search. She persuaded me, gently, that the mythical cottage in the mythical village of my distorted memory didn’t exist. We would have to settle for something not quite so mythical. The baby had had enough too. babies don’t like living for days on end in the back of a car any more than breast-feeding mothers do, I have discovered. By then we had gone further south-west than I intended. We had arrived at a town called Street on the south Devon coast. It was quite a nice sea-side town actually, devoid of housing estates, or at least obvious ones. In an estate agent’s window we saw a pink, thatched cottage for rent for an amount within out budget so we went and had a look.

It was, as I said, a cottage, with a thatched roof, fifty yards from a pub, in a village near a cliff above a deserted stretch of windswept beach. It did feel a bit chilly, and the village was actually only a collection of a dozen or so cottages a few miles from Street, and slightly depressingly lifeless. Also there was something a bit creepy about the place, and also about the big, gothic mansion on the hill where a very old woman lived all alone. Actually I made that last bit up about the mansion. We took the cottage, paid our money and half an hour later we had moved in.

Perfect. Well, not quite…

September 19, 2013

How I made a million from my first novel – part two

It was November when my wife and I, along with our first child, arrived in England on a one-way flight from New Zealand. It’s a long flight with a new-born baby, trust me. We had left home in the spring, exchanging the approach of an Antipodean summer for that of a northern hemisphere winter. Instead of barbecues and weekends at the beach we were prepared for snow and cosy fires as the nights drew in. It was raining the day we arrived. or maybe it wasn’t, I can’t remember to tell the truth. The year was 1996. It doesn’t seem that long ago, but it was a different world then. Most people had never heard of the internet or email. I hadn’t been back to England for about ten years and I was looking forward to the time we  would spend there. Dale and I had never travelled together before, other than to Fiji for a holiday. We had both seen the world when we were younger, before we met, so we were excited about doing this together. We were starting a new chapter in our lives. A new baby, no income, a new country and nowhere to live. None of that mattered though. I was going to reconnect with the country where I had grown up, and I was going to write a novel. I wasn’t quite sure what it would be about, but I was sure something would occur to me.

would spend there. Dale and I had never travelled together before, other than to Fiji for a holiday. We had both seen the world when we were younger, before we met, so we were excited about doing this together. We were starting a new chapter in our lives. A new baby, no income, a new country and nowhere to live. None of that mattered though. I was going to reconnect with the country where I had grown up, and I was going to write a novel. I wasn’t quite sure what it would be about, but I was sure something would occur to me.

There was a slight hitch at immigration. I had a UK passport, as did our baby, but Dale was traveling on her NZ passport. We’d contacted the British embassy before we left and they told us that Dale would need a visa, which was going to cost quite a bit of money. Since money was a commodity in short supply, I persuaded Dale that she wouldn’t really need the visa. After all, we were married and I was British, so how could there be a problem? Dale was dubious but I was insistent.

As it happened, I was wrong, which Dale often tells me is not uncommon. We were held up for about three hours while unsympathetic immigration people listened stony-faced as I explained that we were married, enunciating slowly so they would understand. I dislike officialdom. Actually what I dislike is inflexible people who apply the rules with an iron hand because they like making other people’s lives difficult.

The immigration people insisted that without a visa, Dale could not enter the country, though they agreed that she did meet the criteria to obtain a visa. Fine, I said. Give her one now then. No, they said. She would have to apply in New Zealand before she left. I pointed out that she had in fact already left, and therefore it would be difficult to comply, a response that was met with more and even stonier silence. Eventually a senior officer was summoned, who asked why we hadn’t enquired about the regulations prior to leaving. I sensed that it might not go in our favour if I admitted that we had, but that I objected to paying the exorbitant fees the embassy had demanded and decided to wing it instead. So, sensibly, I lied and claimed that I simply hadn’t thought it would be necessary given the fact that Dale and I were married and had a baby and I was English and… I was probably going to add some final reasoning, laden with sarcasm, but Dale, who is very good with people, quickly intervened. She said nice things and pleaded, looking completely knackered as she tried to soothe the fractious infant in her arms. Her approach worked and in the end, they let us in.

On the way to the car-rental place I couldn’t resist claiming victory, though Dale didn’t exactly see it that way. Try arguing with immigration officials for three hours with a three-week old baby in your arms just after you’ve stepped off a twenty-six hour flight in economy and you’ll probably see her point. Dale still reminds me of this episode to this day. She can bear a grudge. Perhaps the worst part of this story is that about three years later I did the same thing again, sort of, and that time we did get kicked out. So I suppose I can see her point too.